Abstract

Yersinia pestis is a tier 1 agent due to its contagious pneumopathogenicity, extremely rapid progression, and high mortality rate. As the disease is usually fatal without appropriate therapy, rapid detection from clinical matrices is critical to patient outcomes. We previously engineered the diagnostic phage ΦA1122 with luxAB to create a “light-tagged” reporter phage. ΦA1122::luxAB rapidly detects Y. pestis in pure culture and human serum by transducing a bioluminescent signal response. In this report, we assessed the analytical specificity of the reporter phage and investigated diagnostic utility (detection and antibiotic susceptibility analysis) directly from spiked whole blood. The bioreporter displayed 100% (n = 59) inclusivity for Y. pestis and consistent intraspecific signal transduction levels. False positives were not obtained from species typically associated with bacteremia or those relevant to plague diagnosis. However, some non-pestis Yersinia strains and Enterobacteriaceae did elicit signals, albeit at highly attenuated transduction levels. Diagnostic performance was assayed in simple broth-enriched blood samples and standard aerobic culture bottles. In blood, <102 CFU/ml was detected within 5 h. In addition, Y. pestis was identified directly from positive blood cultures within 20 to 45 min without further processing. Importantly, coincubation of blood samples with antibiotics facilitated simultaneous antimicrobial susceptibility profiling. Consequently, the reporter phage demonstrated rapid detection and antibiotic susceptibility profiling directly from clinical samples, features that may improve patient prognosis during plague outbreaks.

INTRODUCTION

Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of the plague, is a tier 1 agent carrying great risk for deliberate misuse and a significant socioeconomic, public health threat. Plague has the ability to spread person to person and is typically fatal in the absence of expedient antibiotic therapy. Over the last 20 years, there has been a global rise in plague incidence and strains have been isolated from patients with bubonic plague that are streptomycin and multidrug resistant (MDR) (1–3). However, Y. pestis is typically not drug resistant, and recent data indicate that pneumonic plague may not be as transmissible as previously believed (4). A zoonotic pathogen, Y. pestis circulates among rodents and lagomorph populations, with endemic foci found in Asia, Africa, the Americas, and the former Soviet Union. Most commonly spread to humans by fleas, plague typically begins by bacterial multiplication at the site of dermal inoculation, followed by spread to the draining lymph node via lymphatic vessels and the formation of characteristic buboes. Bubonic plague can rapidly progress to secondary septicemia, and in some cases, the bacteria can spread systemically and infiltrate alveoli, resulting in the highly lethal pneumonic form. Because of the potential for pneumonia ensuing from bubonic or septicemic plague, the CDC recommends quarantine of all plague patients (5). Of greatest concern in bioterrorism is primary pneumonic plague contracted via inhalation of aerosolized bacilli, which frequently leads to septicemia. Pneumonic plague can be spread person to person and, like septicemic plague, is nearly always fatal without appropriate antibiotic therapy and aggressive supportive care within 18 to 24 h of symptom onset (6).

Plague is definitively diagnosed by the isolation and identification of the organism from clinical specimens or by demonstrating a 4-fold or greater change in antibody titer against the F1 antigen in paired serum specimens. Because Y. pestis grows slowly (doubling time of 1.25 h at 28°C), culturing from clinical specimens can involve incubation for 24 to 72 h. Antibiotic susceptibility analysis from colony isolates requires an additional 24 to 48 h (7, 8) and thus can extend the total diagnostic timeline to between 2 and 5 days. However, because of the fulminant nature of plague infection, rapid appropriate antibiotic therapy is paramount to patient prognosis. Therefore, faster methods of detection and antimicrobial susceptibility profiling of Y. pestis directly from clinical matrices may be valuable.

Classical phage lysis assays using the plague diagnostic phage ΦA1122 are utilized by the WHO, CDC, and public health laboratories for Y. pestis identification. Thought to target receptors likely essential for growth and virulence (9–11), ΦA1122 infects and lyses all but two out of thousands of Y. pestis strains (12). In order to increase the time to detection and bypass the necessity for pure cultures, ΦA1122 was previously genetically engineered with the genes encoding bacterial luciferase (luxA and luxB) to create a reporter phage capable of transducing bioluminescence to infected cells (13). The reporter phage ΦA1122::luxAB was able to rapidly transduce a bioluminescent phenotype (≤20 min) and sensitively detect Y. pestis in pure culture and in spiked human serum, thereby displaying promise as a diagnostic tool. In addition, as phage infection and gene expression are proportional to cell fitness, the reporter phage can rapidly generate antimicrobial susceptibility data from pure cultures, which correlate closely to results obtained using standard methods (14). In this report, we examine the diagnostic performance of the Y. pestis reporter phage directly from blood and from commercial blood culture bottles and evaluate critical diagnostic parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Bacillus anthracis (attenuated strain) was kindly provided by the CDC, Atlanta, GA (Eilke Saile). Escherichia coli (5 various O-antigenic and uropathogenic strains), Enterococcus faecalis (5 strains), Enterococcus faecium (2 strains), Klebsiella pneumoniae (2 strains), Francisella tularensis (2 attenuated strains), Klebsiella oxytoca (1 strain), Klebsiella spp. (2 strains not identified to species level), Listeria monocytogenes (5 strains), Salmonella enterica (10 strains), Shigella flexneri (3 strains), Shigella boydii (1 strain), Shigella sonnei (3 strains), Staphylococcus aureus (3 strains), Staphylococcus epidermidis (2 strains), Streptococcus pneumoniae (3 strains), Yersinia enterocolitica (10 strains), Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (10 strains), and the attenuated Y. pestis strain A1122 were obtained from the Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository (BEI Resources) or the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Experiments involving virulent Y. pestis strains were performed at the University of Florida under biosafety level 3 (BSL3) conditions. A collection of 58 strains, including the classical strains KIM and CO92 as well as strains isolated from diverse sources (human, rodents, and fleas) and different geographical locations (e.g., United States, former Soviet Union, Brazil, Zimbabwe, India, and Nepal), were analyzed. A list of strains is provided in Tables S1 to S4 in the supplemental material.

Phage.

The Y. pestis diagnostic phage ΦA1122::luxAB was described previously (14). Reporter phage stocks were prepared from Y. pestis A1122 using agar overlays. Phage were eluted from the top agar in SM buffer, clarified by centrifugation (4,000 × g for 10 min), and vacuum-filter sterilized (0.22 μM) twice before treatment with 1 M NaCl and precipitation with 8% polyethylene glycol (BioUltra 8000; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The phage precipitate was resuspended in ∼1/10 original volume of SM buffer and adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 1010 to 1 × 1011 PFU/ml. Filter sterilization was repeated for concentrated preparations and confirmed by negative culture on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar. Preparations were stored at 4°C.

Bacterial growth and manipulation.

Frozen stocks (in 25% glycerol at −70°C) of Y. pestis A1122 and the 58 virulent strains were individually streaked onto brain heart infusion (BHI) agar with 6% sheep blood agar (SBA) and LB agar, respectively, and incubated for 48 h at 28°C. Isolates were subcultured in LB broth at 28°C with shaking (250 rpm). Assays were performed using early-exponential-phase cells (A600 of ∼0.2). B. anthracis, E. coli, L. monocytogenes, Y. enterocolitica, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Enterococcus and Staphylococcus spp. were cultured using BHI medium at 37°C. Klebsiella, Salmonella, and Shigella spp. were cultured in tryptic soy media, and F. tularensis strains were cultured on BHI or cystine heart agar (CHA) supplemented with 2% hemoglobin. Cultures at an A600 of 0.2 ± 0.03 were used for experiments. All manipulations were performed within a class II biosafety cabinet.

Bioluminescence assays directly from blood and blood culture bottles.

Fresh (≤1-week-old) whole human blood collected with sodium citrate (Research Blood Components, LLC, Boston, MA) was spiked with Y. pestis A1122 at the indicated concentrations (see Fig. 2 legend). Spiked blood was diluted 1:20 with LB (50 μl into 950 μl) in 14-ml culture tubes and incubated at 28°C with shaking (250 rpm). After 4 h of incubation, blood cells were collected by centrifugation (250 × g for 1 to 2 min), and the resulting supernatants were extracted and recentrifuged at 10,000 × g for 4 min. Bacterial cell pellets were resuspended in 225 μl of remaining supernatant and mixed with the ΦA1122::luxAB reporter phage (1.1 × 109 PFU/assay).

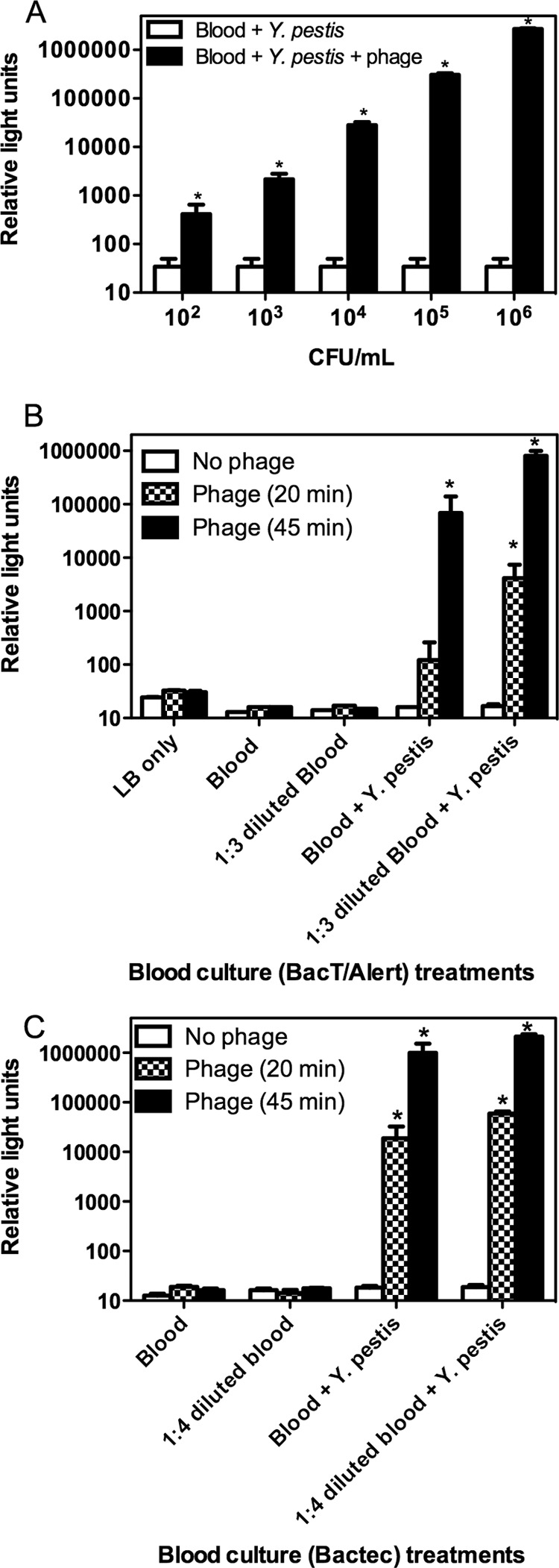

FIG 2.

Bioluminescent detection of Y. pestis from whole human blood. (A) One-milliliter blood aliquots harboring Y. pestis A1122 (5.5 × 106 to 5.5 × 102 CFU/ml) were diluted 1:20 in LB, enriched for 4 h, and analyzed 45 min after phage infection for a bioluminescent signal response. (B) Blood (5 ml) was spiked with 12 CFU/ml Y. pestis A1122 and transferred to standard aerobic BacT/Alert culture bottles. Seeded bottles were machine (BacT/Alert 3D 60) incubated until a colorimetric positive reading was obtained (24 to 27 h). Neat or diluted aliquots were analyzed 20 and 45 min after phage infection for a bioluminescent signal response. (C) Blood (5 ml) was spiked with 4.1 CFU/ml Y. pestis A1122 and transferred to Plus Aerobic/F Bactec culture bottles. Bottles were machine incubated until a colorimetric positive reading was obtained (24 to 30 h). Neat or diluted aliquots were analyzed 20 and 45 min after phage infection for a bioluminescent signal response. Values are means ± SD from 3 independent spiked blood samples. Graphs presented are representative of 2 independent experiments. Asterisks denote a significant increase (P < 0.05) compared to phage-negative controls (cells alone in blood).

Spiked blood samples were also syringe transferred (5 ml) into blood culture bottles (BacT/Alert Standard Aerobic [bioMérieux, Inc., Durham, NC] or Bactec Plus Aerobic/F culture vials [BD and Co., Sparks, MD]) (final blood dilution factor, 1:9 in BacT/Alert and 1:7 in Bactec bottles). Spiked samples were incubated at 35 to 37°C within BacT/Alert and Bactec blood culture systems. Aliquots from seeded (∼101-CFU/ml) culture system-positive Bactec bottles were also assayed without the need for the aforementioned processing and concentration steps. Phage-infected samples were incubated with shaking (250 rpm) for 20 to 45 min. Aliquots (195 μl) were added to 96-well microtiter plates and measured for bioluminescence (Glomax 96 Microplate Luminometer 9101-001; Promega Corp., Madison, WI) for 10 s following injection of 2% n-decanal.

Antibiotic resistance/susceptibility profiling from blood.

To assess the ability of the reporter phage to detect and simultaneously determine antibiotic susceptibility of Y. pestis in blood, spiked blood samples were mixed with LB containing chloramphenicol, streptomycin, or tetracycline at increasing concentrations throughout known activity ranges and MICs. Samples were treated as described above for bioluminescence assays directly from blood. Antibiotic efficacy was confirmed against the quality control S. aureus strain ATCC 29213 according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) broth microdilution methods (7, 8).

Specificity and selectivity assays.

Selectivity of the recombinant ΦA1122::luxAB reporter was assayed for bioluminescence against 59 strains of Y. pestis. Recombinant phage specificity was also determined against 47 strains of closely related genera (i.e., Enterobacteriaceae) and 26 strains of nonrelated but clinically relevant bacterial pathogens through bioluminescence assays. Briefly, log-phase cultures (1 ml) were placed into 14-ml snap-cap tubes (n = 3), infected with ΦA1122::luxAB, and assayed for bioluminescence over time. Relative bioluminescence (RB) was calculated by dividing the average relative light units (RLU) of Y. pestis A1122 by the average RLU of the test strain. Efficiency of plating (EOP), as defined by the phage titer on a test strain/species compared to the maximum titer, was also analyzed where appropriate using Y. pestis A1122 as the standard (12). Specific strain data for EOP and relative bioluminescence are provided in Tables S2 and S3 in the supplemental material.

Statistics.

Reported as CFU/ml or PFU/ml, all bacterial cell or phage titer concentrations were quantified as the averages of duplicate colony or plaque plate counts, respectively. Bioluminescence values, presented as relative light units (RLU), are the averages of three infections (n = 3) ± standard deviations (SD). All experiments were performed in duplicate. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired Student's t tests. Tukey's adjusted analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed for comparisons between multiple data sets, and Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) was used to evaluate dependencies between data sets. Significance was assigned at P ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2010 and GraphPad Prism 5.0 on Windows 7.

RESULTS

Selectivity and specificity.

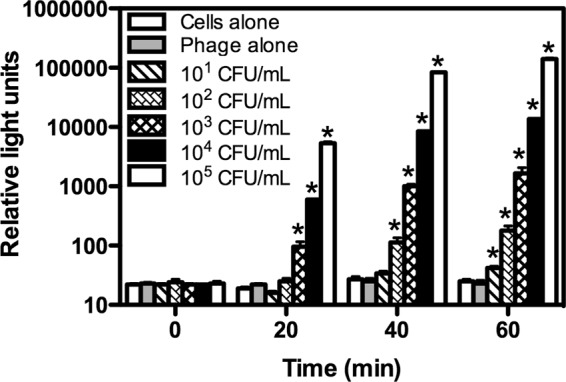

We previously analyzed the ability of ΦA1122::luxAB to detect Y. pestis A1122, an attenuated exempt select agent strain. However, the functionality of the reporter phage against a range of virulent strains had not been assessed. Therefore, performance was tested against a diverse library of Y. pestis strains (n = 59). In addition, non-Y. pestis Yersinia spp., other Enterobacteriaceae, and distantly related but clinically relevant bacterial pathogens were also analyzed. Of the 59 Y. pestis strains, all (100%) elicited rapid bioluminescence of similar signal intensities and kinetics (Fig. 1 and data not shown). For example, after 20 min of ΦA1122::luxAB infection, Y. pestis CO92 elicited a 100-fold increase in signal compared to controls, with peak light signal manifesting at 40 to 60 min postinfection (Fig. 1). Dose-response analysis of 10-fold serially diluted cells indicated that a bioluminescent signal (RLU) was detectable from 2,400, 240, and 24 CFU/ml after 20, 40, and 60 min of infection, respectively (Fig. 1; P < 0.05). Similar data were obtained with 4 other Y. pestis strains (A1122, 2095G, NR-20, and NR-641). The data also indicate that (i) ΦA1122::luxAB exhibits the same broad intraspecies specificity as does its parent ΦA1122 and (ii) results obtained using the attenuated Y. pestis A1122 strain are translatable to virulent strains.

FIG 1.

Bioluminescent response kinetics for the detection of Y. pestis CO92. Actively growing (A600 of ∼0.2) cells were serially diluted, infected with 1.4 × 108 PFU/ml ΦA1122::luxAB, and assayed for bioluminescence (RLU) following the addition of n-decanal substrate. An asterisk denotes a significant increase (P < 0.05) compared to phage-negative (cells only) controls at the designated times. Values are means (n = 3) ± SD. Similar results were obtained with 58 other Y. pestis strains.

The reporter phage was used to challenge 70 non-Y. pestis strains for phage-mediated bioluminescence and, in some cases, for phage amplification (EOP assays). These included closely related yersiniae, members of the Enterobacteriaceae, enterococci and staphylococci, and B. anthracis and F. tularensis. Three of 10 Y. enterocolitica strains and 7 of 10 Y. pseudotuberculosis strains elicited phage-mediated bioluminescence (Table 1). Of these, only one Y. pseudotuberculosis strain expressed a signal as high as 1 log below that of Y. pestis, while the remainder were generally 104- to 105-fold lower. In general, there was a correlation between phage-mediated bioluminescence and EOP; strains that elicited low bioluminescence yielded low EOPs.

TABLE 1.

Specificity of ΦA1122::luxAB among non-pestis Yersinia species, closely related species, and nonrelated but clinically relevant bacterial pathogens

| Bacterial species | No. of positive strains/total no. tested | Relative bioluminescence (range)a | Efficiency of platingb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yersiniae | |||

| Y. enterocolitica | 3/10 | 10−6–10−4 | ≤3.6 × 10−6 |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis | 7/10 | 10−6–10−1 | <1 × 10−6 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | |||

| E. colic | 0/5 | Background | ND |

| Klebsiella spp.d | 0/5 | Background | ND |

| S. entericae | 4/10 | 10−6–10−3 | <1 × 10−6 |

| S. boydii | 0/1 | Background | ND |

| S. flexneri | 0/3 | Background | ND |

| S. sonnei | 2/3 | 10−6–10−5 | ≤1.2 × 10−5 |

| Non-Enterobacteriaceae | |||

| B. anthracis | 0/1 | Background | ND |

| E. faecalis | 0/5 | Background | ND |

| E. faecium | 0/2 | Background | ND |

| F. tularensis | 0/2 | Background | ND |

| L. monocytogenes | 0/5 | Background | ND |

| Staphylococcus spp.f | 0/5 | Background | ND |

| S. pneumoniae | 0/3 | Background | ND |

Relative to Y. pestis A1122; relative bioluminescence = RLU of non-Y. pestis strain/RLU of Y. pestis A1122 at 28°C.

Efficiency of plating relative to Y. pestis A1122 at 28°C. ND, not determined.

Includes O91:H21, O157:H7, O145:nm, and a uropathogenic strain (serotype unknown).

Includes K. oxytoca and K. pneumoniae.

Includes both Typhi and non-Typhi Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica strains.

Includes S. aureus and S. epidermidis.

Due to temperature-dependent differences in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure, ΦA1122 does not form plaques on Y. pseudotuberculosis below 28°C (9, 12). As expected, phage-mediated bioluminescence assays at 20°C revealed an attenuated (102- to 104-fold lower) signal in 5 Y. pseudotuberculosis strains compared to assays performed at 37°C. Unexpectedly, one strain elicited a 103-fold increase at the reduced temperature (data not shown).

Among other species, none of the E. coli, Klebsiella, S. boydii, or S. flexneri strains elicited phage-mediated bioluminescence (Table 1). However, bioluminescence was detected from four S. enterica and two S. sonnei strains, although the signal response was extremely low. As may be expected, none of the phylogenetically distant but clinically relevant strains elicited reporter phage-mediated bioluminescence.

Rapid detection of Y. pestis from blood and blood culture bottles.

Because bacteremia is common in bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic plague, blood is an important matrix for laboratory diagnosis. Blood culture systems can be used to screen for bacteremia. Therefore, the efficacy of reporter phage-mediated detection of Y. pestis A1122 was assessed directly from blood and blood culture bottles. Y. pestis was detected in diluted blood within 5 h, without the need for culture isolation (Fig. 2A, P < 0.05). The signal response exhibited dose-dependent characteristics with a sensitivity limit of detection (LoD) in the 102-CFU/ml range, peaking 45 min after phage infection. Similar results were obtained from BacT/Alert and Bactec culture bottles, indicating a functional compatibility of this detection platform with established clinical procedures for processing blood samples. Although “light” signal measurements were somewhat attenuated in blood, signal production was extremely rapid. Seeded Bactec bottles (n = 6) registered positive for bacterial growth after 24 to 30 h (blood-alone controls did not register positive as expected), and aliquots from these bottles were diagnosed by the reporter phage 20 to 45 min after infection without sample processing or concentration (Fig. 2B and C, P < 0.05).

Rapid antibiotic susceptibility profiling from blood.

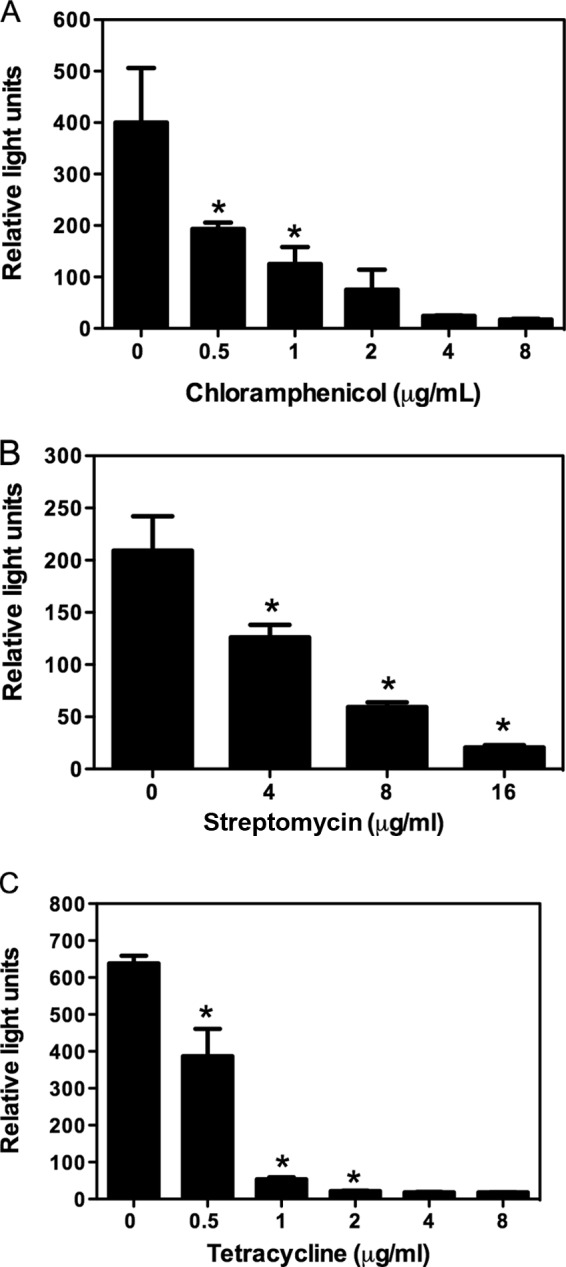

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiling using the reporter phage has been previously demonstrated using pure cultures (14). To assess the ability of ΦA1122::luxAB to profile antibiotic susceptibility of Y. pestis without the need for culture isolation, blood samples were spiked with ca. 102 CFU/ml Y. pestis and diluted in LB medium containing increasing concentrations of chloramphenicol, streptomycin, or tetracycline along the known MIC ranges (Fig. 3A to C). These antibiotics were selected because they are the standard therapeutics and prophylactics recommended for plague in humans (6). Samples were incubated for 4 h, infected with ΦA1122::luxAB, and then assayed for bioluminescence after 45 min. For each antibiotic, bioluminescence was inversely proportional to antibiotic concentration. High antibiotic concentrations completely nullified signal production, whereas low antibiotic concentrations resulted in strong signals. Thus, rapid detection and simultaneous antibiotic susceptibility profiling of low levels of Y. pestis are achieved through use of the reporter phage detection platform.

FIG 3.

Phage-mediated antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Y. pestis A1122 directly from blood incubated in the presence of chloramphenicol (A), streptomycin (B), or tetracycline (C). Antibiotics were prepared using the CLSI microdilution method. Whole blood was spiked with 75, 44, and 105 CFU/ml for panels A, B, and C, respectively; diluted 1:20; and incubated at 35°C for 4 h before being infected with the reporter phage. Values are means ± SD from 3 independent infections of spiked blood. Graphs presented are representative of 2 independent experiments. Asterisks denote a significant difference increase (P < 0.05) between the assigned value and the next highest antibiotic concentration.

DISCUSSION

Plague is definitively diagnosed by the isolation and identification of the organism from clinical specimens or by demonstrating a 4-fold or greater change in antibody titer against the F1 antigen in paired serum specimens. As phage A1122 can be used to identify Y. pestis using classical lysis assays, ΦA1122::luxAB has the potential to expedite this process. Data obtained using strain A1122 indicated that detection was achieved with blood spiked with 100 CFU/ml within 5 h, with similar results from blood culture. Of note, samples from culture-positive blood bottles were “diagnosed” by the reporter with no preparation, processing, or concentration steps, within 20 to 45 min. Because massive plague bacteremia generally foreshadows a fatal prognosis, and bacteremic concentrations of ≥100 CFU/ml are significantly correlated with mortality, detection of plague bacilli below this level is crucial for a clinically actionable plague diagnostic (6, 15, 16).

ΦA1122::luxAB efficiently detected all Y. pestis strains tested and likely possesses the same specificity as its parent phage, which infects all but two of thousands of isolates. However, the broad intraspecific host range is counterbalanced by suboptimal cross-reactivity, as the reporter transduced bioluminescence to 16 of 47 strains of phylogenetically related species (i.e., Enterobacteriaceae). In cross-reactive strains, amplitude of transduced light was 101- to 106-fold lower (overall median RB = 1.13 × 10−5 RLU/assay) and time to peak signal was generally longer than those for Y. pestis. In receptive Y. pseudotuberculosis strains, assays at subdiagnostic temperature (20°C) revealed signal attenuation by up to 104-fold in most, but not all, strains evaluated. Therefore, the reporter phage may require complementary diagnostic testing to reduce the likelihood of false positives, and particularly to discriminate between Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis. Importantly, none of the assayed pathogens integral in the differential diagnosis for plague (i.e., B. anthracis, F. tularensis, and Klebsiella pneumoniae) or those most frequently associated with bacteremia (i.e., Enterococcus spp., E. coli, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp., and Streptococcus spp.) (17–19) were positive for bioluminescence. However, as the reporter phage diagnostic requires laboratory equipment and up to 5 h to elicit a response from clinical specimens, it is not usable in its current form as a point-of-care test. In contrast, the plague dipstick tests which target the F1 antigen are specific (no other yersiniae are detected) and sensitive and are particularly useful for field applications as they are rapid (less than 15 min) and do not require equipment (20, 21). Therefore, dipstick tests have many advantages over the reporter phage technology. However, as F1-negative isolates can occur, albeit rarely (22), the reporter phage may be a useful alternative to tests that rely on the F1 antigen.

Appropriate antibiotic therapy within 18 to 24 h of symptom onset is essential for a positive prognosis in plague patients (23, 24). Chloramphenicol, streptomycin, and tetracycline are the recommended primary-level treatments (1, 6). In addition to the potential for engineered resistance in bioweapons, naturally occurring antibiotic-resistant strains of Y. pestis, although extremely rare, have been isolated (2, 3, 25). Thus, the ability to rapidly generate an antibiotic susceptibility profile is of value. Immunoassays and most PCR-based methods are unable to distinguish viable from dead cells and are therefore of limited use in determining antibiotic susceptibility. A method employing flow cytometry to determine antibiotic susceptibility following the separation of plague bacilli from spiked blood cultures has been described, although the need for preenrichment extends the assay time to ca. 39 h. The reporter phage diagnostic described here has the ability to detect Y. pestis and to simultaneously determine its susceptibility to antibiotics directly from blood within 5 h. This diagnostic therefore has the potential to provide critical information, timely enough to augment treatment and improve patient outcomes in both bioterrorism and naturally acquired cases of plague.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by award numbers R43AI082698, R44AI082698, and R01AI111535 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (awarded to D.A.S. of Guild BioSciences).

We thank A. Sulakvelidze (University of Florida) and C. Westwater (Medical University of South Carolina) for their advice and support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 June 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00316-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Galimand M, Carniel E, Courvalin P. 2006. Resistance of Yersinia pestis to antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3233–3236. 10.1128/AAC.00306-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galimand M, Guiyoule A, Gerbaud G, Rasoamanana B, Chanteau S, Carniel E, Courvalin P. 1997. Multidrug resistance in Yersinia pestis mediated by a transferable plasmid. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:677–680. 10.1056/NEJM199709043371004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guiyoule A, Gerbaud G, Buchrieser C, Galimand M, Rahalison L, Chanteau S, Courvalin P, Carniel E. 2001. Transferable plasmid-mediated resistance to streptomycin in a clinical isolate of Yersinia pestis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:43–48. 10.3201/eid0701.010106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinckley AF, Biggerstaff BJ, Griffith KS, Mead PS. 2012. Transmission dynamics of primary pneumonic plague in the USA. Epidemiol. Infect. 140:554–560. 10.1017/S0950268811001245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fritz CL, Dennis DT, Tipple MA, Campbell GL, McCance CR, Gubler DJ. 1996. Surveillance for pneumonic plague in the United States during an international emergency: a model for control of imported emerging diseases. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2:30–36. 10.3201/eid0201.960103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler T. 2009. Plague into the 21st century Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:736–742. 10.1086/604718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2010. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 20th informational supplement. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2009. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard—8th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiljunen S, Datta N, Dentovskaya SV, Anisimov AP, Knirel YA, Bengoechea JA, Holst O, Skurnik M. 2011. Identification of the lipopolysaccharide core of Yersinia pestis and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis as the receptor for bacteriophage phiA1122. J. Bacteriol. 193:4963–4972. 10.1128/JB.00339-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knirel YA, Anisimov AP. 2012. Lipopolysaccharide of Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague: structure, genetics, biological properties. Acta Naturae 4:46–58 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filippov AA, Sergueev KV, He Y, Huang XZ, Gnade BT, Mueller AJ, Fernandez-Prada CM, Nikolich MP. 2011. Bacteriophage-resistant mutants in Yersinia pestis: identification of phage receptors and attenuation for mice. PLoS One 6:e25486. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia E, Elliott JM, Ramanculov E, Chain PS, Chu MC, Molineux IJ. 2003. The genome sequence of Yersinia pestis bacteriophage phiA1122 reveals an intimate history with the coliphage T3 and T7 genomes. J. Bacteriol. 185:5248–5262. 10.1128/JB.185.17.5248-5262.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schofield DA, Molineux IJ, Westwater C. 2009. Diagnostic bioluminescent phage for detection of Yersinia pestis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3887–3894. 10.1128/JCM.01533-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schofield DA, Molineux IJ, Westwater C. 2012. Rapid identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing of Yersinia pestis using bioluminescent reporter phage. J. Microbiol. Methods 90:80–82. 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler T, Levin J, Linh NN, Chau DM, Adickman M, Arnold K. 1976. Yersinia pestis infection in Vietnam. II. Quantitative blood cultures and detection of endotoxin in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 133:493–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Putzker M, Sauer H, Sobe D. 2001. Plague and other human infections caused by Yersinia species. Clin. Lab. 47:453–466 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lark RL, Chenoweth C, Saint S, Zemencuk JK, Lipsky BA, Plorde JJ. 2000. Four year prospective evaluation of nosocomial bacteremia: epidemiology, microbiology, and patient outcome. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 38:131–140. 10.1016/S0732-8893(00)00192-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lark RL, Saint S, Chenoweth C, Zemencuk JK, Lipsky BA, Plorde JJ. 2001. Four-year prospective evaluation of community-acquired bacteremia: epidemiology, microbiology, and patient outcome. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 41:15–22. 10.1016/S0732-8893(01)00284-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bearman GM, Wenzel RP. 2005. Bacteremias: a leading cause of death. Arch. Med. Res. 36:646–659. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chanteau S, Rahalison L, Ralafiarisoa L, Foulon J, Ratsitorahina M, Ratsifasoamanana L, Carniel E, Nato F. 2003. Development and testing of a rapid diagnostic test for bubonic and pneumonic plague. Lancet 361:211–216. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12270-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chanteau S, Rahalison L, Ratsitorahina M, Mahafaly , Rasolomaharo M, Boisier P, O'Brien T, Aldrich J, Keleher A, Morgan C, Burans J. 2000. Early diagnosis of bubonic plague using F1 antigen capture ELISA assay and rapid immunogold dipstick. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290:279–283. 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80126-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anisimov AP, Lindler LE, Pier GB. 2004. Intraspecific diversity of Yersinia pestis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:434–464. 10.1128/CMR.17.2.434-464.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woods JB. 2005. USAMRIID's management of biological casualties handbook. USAMRIID, Frederick, MD [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. 2008. Interregional meeting on prevention and control of plague. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welch TJ, Fricke WF, McDermott PF, White DG, Rosso ML, Rasko DA, Mammel MK, Eppinger M, Rosovitz MJ, Wagner D, Rahalison L, Leclerc JE, Hinshaw JM, Lindler LE, Cebula TA, Carniel E, Ravel J. 2007. Multiple antimicrobial resistance in plague: an emerging public health risk. PLoS One 2:e309. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.