Abstract

Oral microbial communities are extremely complex biofilms with high numbers of bacterial species interacting with each other (and the host) to maintain homeostasis of the system. Disturbance in the oral microbiome homeostasis can lead to either caries or periodontitis, two of the most common human diseases. Periodontitis is a polymicrobial disease caused by the coordinated action of a complex microbial community, which results in inflammation of tissues that support the teeth. It is the most common cause of tooth loss among adults in the United States, and recent studies have suggested that it may increase the risk for systemic conditions such as cardiovascular diseases. In a recent series of papers, Hajishengallis and coworkers proposed the idea of the “keystone-pathogen” where low-abundance microbial pathogens (Porphyromonas gingivalis) can orchestrate inflammatory disease by turning a benign microbial community into a dysbiotic one. The exact mechanisms by which these pathogens reorganize the healthy oral microbiome are still unknown. In the present manuscript, we present results demonstrating that P. gingivalis induces S. mitis death and DNA fragmentation in an in vitro biofilm system. Moreover, we report here the induction of expression of multiple transposases in a Streptococcus mitis biofilm when the periodontopathogen P. gingivalis is present. Based on these results, we hypothesize that P. gingivalis induces S. mitis cell death by an unknown mechanism, shaping the oral microbiome to its advantage.

INTRODUCTION

The human oral microbiome consists of over 600 individual taxa (1, 2). Its complexity and the fact that a large fraction of species is noncultivable have hampered our knowledge of the molecular and metabolic interactions that occur between the species of the bacterial biofilm and between bacteria and host.

Periodontal disease is a polymicrobial inflammatory biofilm-mediated pathology that leads to a progressive loosening and eventual loss of teeth (3, 4), and it is responsible for half of all tooth loss in adults that occurs in moderate form in 39% of American adults and in severe form in 9% of adults. Polymicrobial diseases are increasingly being recognized as more frequent than previously thought (5). In these diseases there are complex interactions among the etiologic agents, which ultimately lead to disease. In the microbial etiology of periodontitis it is generally accepted that a consortium of bacteria, not a single microorganism, is involved in the disease. Nonetheless, it is well established that in destructive periodontitis, the “red complex” (Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia) are key players in the disease process (6).

A more holistic treatment of periodontitis or any other polymicrobial disease requires a better understanding of the ecology of the microbial community and the mechanisms that cause the shift from a mature stable biofilm to a dysbiotic community responsible for disease. Maintaining a healthy biofilm would be a less invasive strategy than removing an already established pathogenic biofilm.

S. mitis is one of the most abundant organisms in healthy oral microbiomes (7). Any decrease in its numbers would have an impact in the health status of the oral biofilm. In our recent work on a multispecies biofilm model, we observed that the presence of P. gingivalis upregulated the expression of a large number of putative transposases in two members of the healthy biofilm model, S. mitis and Lactobacillus casei (8).

The nature of the interactions between oral streptococci and the major periodontal pathogen P. gingivalis is complex, demonstrating both synergistic and antagonistic interactions. Pioneer studies on coaggregation provided a foundation of knowledge regarding bacterium-bacterium interactions within the oral biofilm. Oral bacteria showed specific coaggregation patterns due to the presence of certain receptors on their surface (9). P. gingivalis can coaggregate with a variety of oral bacteria, such as Fusobacterium nucleatum, Actinomyces viscosus, T. denticola, and species of Streptococcus, such as Streptococcus oralis and Streptococcus gordonii (9, 10). There are also negative interactions wherein streptococci inhibit P. gingivalis growth and protease activity (11, 12). In a clinical study, Wang et al. have shown that there is a negative correlation of distributions of Streptococcus cristatus and P. gingivalis in subgingival plaque (13). P. gingivalis and S. gordonii do not form a mature biofilm when growing independently on coverslips coated with saliva, demonstrating synergistic interactions. However, biofilm formation occurs when S. gordonii cells are first deposited on the salivary pellicle. S. gordonii may therefore provide an attachment substrate for colonization and biofilm accretion by the potential pathogen, P. gingivalis (14). Moreover, Periasamy and Kolenbrander showed that although P. gingivalis was incapable of forming a biofilm in the presence of S. oralis alone, the addition of S. gordonii was enough to allow the establishment of a mature biofilm by P. gingivalis and the two streptococci (15).

As mentioned above, in a previous metatranscriptomic analysis we observed a high upregulation of a large number of putative transposases in S. mitis expression profiles when P. gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans were added to an established healthy biofilm (8). Upregulation of putative transposases has been observed by Mitchell et al. in the periodontal pathogen T. denticola when growing as a biofilm but not in planktonic growth, concluding that there is a higher potential for genetic mobility in T. denticola biofilms (16). However, the high number of transposases upregulated simultaneously in our experiments is probably not a sign of DNA mobilization but rather of some other mechanism related to the ecology of the biofilm. Our hypothesis is that these proteins are involved in a controlled cell death process in S. mitis. In the present study, we address the following questions: Does the presence of P. gingivalis induce cell death of S. mitis in a two-species biofilm model? Does cell death of S. mitis present some of the features characteristic of controlled cell death in bacteria?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The species used in the present study were: S. mitis (NCTC 12261), P. gingivalis (ATCC 33277), P. gingivalis (W83), T. forsythia (ATCC 43037), and Escherichia coli (ATCC 47055). P. gingivalis strains were grown under anaerobic conditions at 37°C for 24 h in a COY anaerobic chamber on Trypticase soy agar (TSA) plates supplemented with 5% sheep blood (Northeastern Laboratory, Waterville, ME), 1 μg of hemin/ml, and 1 μg of vitamin K/ml. E. coli was grown aerobically on Trypticase soy yeast blood (TSYB) at 37°C for 24 h. T. forsythia was grown anaerobically on TSA medium containing 5 μg of hemin/ml, 0.001% N-acetylmuramic acid, 0.1% l-cysteine, and 5% sheep blood at 37°C for 5 days. S. mitis was grown on TSYB anaerobically for 24 h.

Biofilm growth.

Biofilms of S. mitis were grown on sterile hydroxyapatite discs of 7 mm x 1.8 mm (Clarkson, Inc., Chula Vista, CA) placed into each well of a 24-well cell culture plate (Nalgene Nunc International, Denmark). Wells were filled with 1 ml of the mucin growth medium (MGM) used by Kinniment et al. (17), which presents a high concentration of proteins, and supplemented with 4 ml of resazurin from a 25-mg/100 ml stock solution, 1 μg of hemin/ml, and 1 μg of vitamin K/ml. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 prior to autoclaving. In order to form the acquired pellicle, the discs were allowed to stay at least 48 h in contact with the medium under anaerobic conditions prior inoculation. This preincubation period allowed time to check for possible contamination. S. mitis was resuspended in MGM medium until it reached a turbidity of McFarland 3 (∼108 CFU/ml). Finally, 50 μl of bacterial culture was added to each hydroxyapatite disk-containing well. The plates were incubated under anaerobic conditions at 37°C. After 24 h, the old medium was replaced by new MGM, and P. gingivalis was added to the biofilm as described above, followed by incubation for another 6 h before sampling for analysis. As control strains, we used S. mitis, E. coli, and T. forsythia, which were inoculated into the biofilm and incubated as described above.

RNA extraction.

Biofilms grown on hydroxyapatite disks were immediately transferred to a screw-cap tube containing lysis buffer from a mirVana miRNA isolation kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and bead-beaten for 1 min at maximum speed. RNA was extracted with the mirVana miRNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Genomic DNA was removed using a Turbo DNA-free kit (Life Technologies).

DNA extraction.

Standards were generated from cultures of S. mitis and P. gingivalis, whose numbers of cells were known. DNA from the standards and biofilms were extracted using UltraClean microbial DNA isolation kit (MoBio, Carlsbad, CA).

qPCR and RT-qPCR.

Table 1 presents the primers used in these experiments. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed to quantify the relative number of P. gingivalis in S. mitis biofilms. Quantification was performed from three biological independent experiments and three technical replicates per experiment. Reverse transcription-qPCR (RT-qPCR) was performed to quantify levels of expression of the different genes assessed shown in Table 1. IQ SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. For RT-qPCR 100 ng of RNA was reverse transcribed with a SuperScript double-stranded cDNA synthesis kit (Life Technologies) according to the instructions provided. Real-time quantification of double-stranded DNA fragments was performed with an iCycler iQ thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). A melting-curve analysis followed the amplification. Statistical significance was tested by a Student t test for comparing means in R.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in the experimentsa

| Strain and locus | Functionb | Sequence (5′-3′) |

Fragment size (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward primer | Reverse primer | |||

| Streptococcus mitis | ||||

| SM12261_0395 | LrgB family protein | TTACCAAGATTACTACCAAG | AGCAGACTACCAAAGAGA | 138 |

| SM12261_0396 | LrgA family (CidA putative homolog) | ATTGTTTTGATTGTCTTTT | ATCTCCTTTCTCATAATCTC | 105 |

| SM12261_0967 | Two-component sensor kinase YesM, putative (LytS putative homolog) | TGTTCCATCATTACTTTTAC | AGTCCTCAGTTTTTACTTTT | 113 |

| SM12261_0914 | Membrane-bound protein LytR | AGTTTTAGGTGTGGGTGT | AATAACATTGGTTTCTTCC | 100 |

| SM12261_0124 | Transcriptional regulator, LytR family | AAAAATACCAGAAAACTCA | AACATAAAAATCATACCAAA | 127 |

| SM12261_0760 | Choline binding protein D | TGGGAGCCAGGAGATTGATA | TGCAGTAGACCAAGCAATGG | 199 |

| SM12261_0107 | Integrase core domain, putative (putative transposase) | GGCAATACCAACACGACTCTTA | GACTCCATCATACCGTTGTCTG | 103 |

| SM12261_0212 | Transposase | CTTGAGAGCGGAGAATGCCA | TACCAGTCCTTGAACAATTTCCGT | 99 |

| SM12261_0476 | Transposase | TTCTCGTCTGCCTGAGATTATG | CCCTCGAGAACAGTGATGATATT | 111 |

| SM12261_1313 | Transposase | TTGGGACGAGTATGCCTTTAC | ATAGCCTGTGTTCTGCCTTC | 102 |

| SM12261_1134 | Transposase | GGACGAGTATGCCTTCACTAAG | TCGGATGATAGTCTGGGTTCTA | 106 |

| SM12261_0522 | Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase D (LytC putative homolog) | GACTGAAGGTGGAGAAGGTATTG | CTACCGCTTAACTGTCCAGAAG | 90 |

| SM12261_1140 | Lysozyme (LytC putative homolog) | CTGACCGTGCTAAGAAGGTTAT | CGCACAATAACACCATCAACTC | 103 |

| SM12261_0045 | Hypothetical protein (CibA putative homolog) | TGATGAATGTGGATGGAGGAATTA | AGCTACACCTGCACTCAAAC | 92 |

| SM12261_0414 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (8) | CGTATCGGTCGTCTTGCT | GCATAACTGGATCTGTAAGGTC | 106 |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | Arg-gingipain gene (18) | CCTACGTGTACGGACAGAGCTATA | AGGATCGCTCAGCGTAGCATT | 71 |

The annotation of all proteins is based on the RefSeq database (NCBI).

In parentheses are the putative homologues based on the best blast hits of the NCBI nr-database.

Confocal scanning laser microscopy of live/dead cells in the biofilm.

A confocal scanning fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Germany) with lens (FV300; Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan) was used to observe the distribution of live and dead bacteria in the biofilms. The bacteria in the biofilm were observed using a Live/Dead BacLight bacterial viability kit (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The biofilms were stained in the dark at room temperature for 15 min. An argon laser (476 nm) was used as the excitation source for the reagents, and the fluorescence emitted was collected by two separate emission filters at 500 nm (SYTO 9) and 635 nm (propidium iodide [PI]), respectively. Twenty sections per biofilm were collected, and the biovolume of live/dead biofilms was obtained using ImageJ and COMSTAT (19). Each assay was performed at least three times for each condition, capturing 20 sections for analysis. Statistical significance was tested by using the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test in R.

DNA fragmentation assay by the TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling) method.

Cells from the biofilm were resuspended in 50% ethanol, fixed overnight at 4°C, and washed once in phosphate-buffered saline. Permeabilization was performed by treatment with lysozyme (Sigma; 140,000 U/ml in Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]–5 mM EDTA). Afterward, an Apo-Direct kit (BD Bioscience), which uses fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated dUTP for staining and PI as a counterstain, was used, according to the procedure described by Dwyer et al. (20). Finally, cells were spotted on poly-l-lysine-coated slides (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA) and visualized on a Zeiss Axiovert II epifluorescence microscope. We performed the experiment by triplicate, observing 20 fields in each case.

TOS assay.

Oxidants present in the sample oxidize the ferrous ion-s-dianisidine complex to ferric ion. The oxidation reaction is enhanced by glycerol molecules, which are abundantly present in the reaction medium. The ferric ion makes a colored complex with xylenol orange in acidic medium. The color intensity, which can be measured spectrophotometrically, is related to the total amount of oxidant molecules present in the sample. The total oxidant status (TOS) was measured on hydroxyapatite discs of S. mitis biofilms grown under the conditions described previously. TOS was determined using a method described by Erel (21) and is expressed as μmol of H2O2 equivalent/liter. The assay was calibrated with hydrogen peroxide by linear relation. Briefly, a hydroxyapatite disc was placed for 10 min in a well of 96-well plate containing 225 μl of reagent 1 (150 μM xylenol orange, 140 mM NaCl, and 1.35 M glycerol [pH 1.75]) at room temperature. After the disc was removed with a plastic pin, the absorbance at 560 nm was recorded in a spectrophotometer Synergy (Biotek, Winooski, VT). After 11 μl of reagent 2 (5 mM ferrous ammonium sulfate and 10 mM o-dianisidine dihydrochloride in 25 mM H2SO4) was added, the sample was incubated for 4 min at room temperature, followed by an endpoint absorbance reading at same wavelength. Concentrations were calculated as described by Erel (21). The TOS was determined on S. mitis biofilms alone (24 h) and on P. gingivalis biofilm alone (6 h) as negative controls. Each test was performed in triplicate in four independent experiments. Statistical significance was tested by a Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test in R.

RESULTS

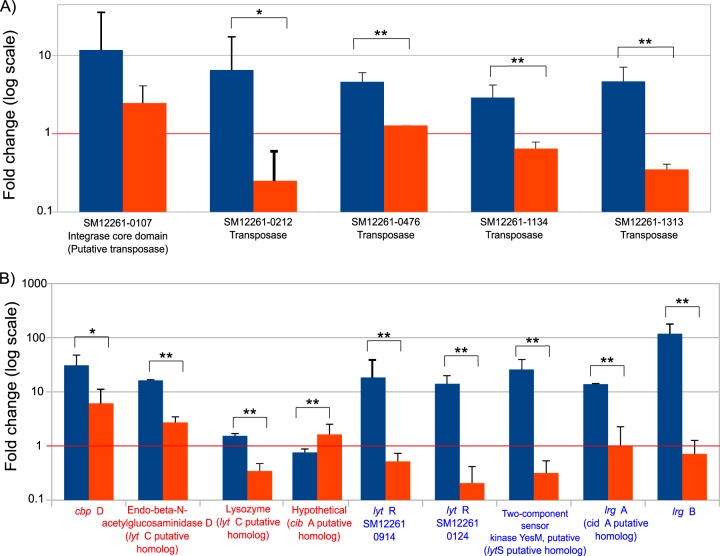

We had previously observed the upregulation of putative transposases in an S. mitis biofilm in a multispecies biofilm model where two periodontal pathogens (P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans) were added simultaneously (8). We first verified the upregulation of these putative transposases when only P. gingivalis was added. Interestingly, when we added the periodontopathogen T. forsythia, no effect was observed on the expression profiles of the transposases; only SM12261_0107 was not significantly more upregulated in the presence of P. gingivalis (Fig. 1A). We cannot discard the possibility that with longer periods of incubation T. forsythia would not induce expression of those genes, but under the conditions tested it did not have a notable effect. We also observed upregulation of genes involved in cell death in S. mitis in our previous work when P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans were added simultaneously (8). We selected a list of genes whose orthologues have been linked to fratricide and cell death in other organisms and performed an RT-qPCR on RNA extracted from a monospecies biofilm of S. mitis to which we added P. gingivalis. Figure 1B shows the results for these experiments and revealed upregulation of all of the genes except for lrgA (cidA), where no differences were observed.

FIG 1.

RT-qPCR expression results for putative transposases of S. mitis in the presence of different periodontal pathogens. (A) RT-qPCR expression results of putative transposases of S. mitis in the presence of P. gingivalis. To confirm the metatranscriptomic results showing an upregulation of putative transposases in S. mitis, we performed an RT-qPCR in another series of experiments where S. mitis grew as a monospecies biofilm and P. gingivalis (in blue) was added as described elsewhere (8). In addition, we present results for the induction of the transposases by a strain of T. forsythia (in orange). (B) RT-qPCR expression results of some of the genes potentially involved in S. mitis cell death. We selected a list of genes whose orthologues have been linked to fratricide and cell death in other organisms and performed an RT-qPCR on RNA extracted from a monospecies biofilm of S. mitis to which we added P. gingivalis and T. forsythia. Names in red are the genes involved in fratricide. In blue are the genes involved in PCD. In parentheses are the putative homologues based on the best blast hits of the NCBI nr-database. The red line represents no changes in expression. Columns in blue show results for the addition of P. gingivalis, and columns in red are for the addition of T. forsythia. The results are averages of three independent biological experiments (n = 3). Error bars show the standard deviations for biological replicate values. Significance was tested by a Student t test, with asterisks representing groups with significant differences at P < 0.1 (*) and P < 0.05 (**).

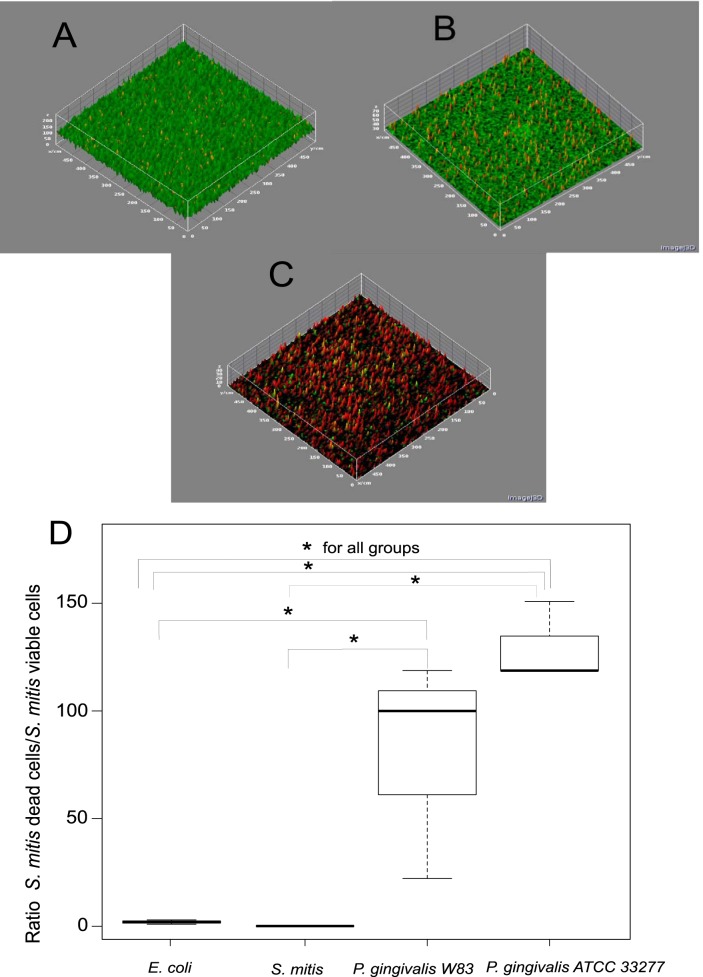

The next series of experiments were performed to demonstrate that the presence of P. gingivalis in the biofilm induced cell death of S. mitis. As previously described, P. gingivalis was added and incubated only for a period of 6 h. We did not use T. forsythia as a control because this organism has a doubling time of 24 h (22), and it would be extremely difficult to distinguish cell death due to the presence of T. forsythia from cell death due to the normal evolution of an old biofilm. We showed by qPCR that the number of S. mitis cells was several logarithms higher than the number of P. gingivalis at the end of the experiment. The total numbers of cells in the biofilm for S. mitis and P. gingivalis were 1.44 × 107 ± 1.1 × 107 and 2.2 × 104 ± 9.1 × 103, respectively. Afterward, we used a live/dead stain to quantify by confocal scanning microscopy the fraction of S. mitis dead cells in the presence or absence of P. gingivalis in the biofilm. The presence of P. gingivalis drastically increased the fraction of S. mitis dead cells (Fig. 2C and D). Moreover, the addition of either S. mitis or E. coli did not have any effect on the viability of the S. mitis biofilm; in fact, S. mitis continued growing after its own addition (Fig. 2A, B, and D). The two strains of P. gingivalis used in these experiments (ATCC 33277 and W83) showed similar effects with a 10-fold increase in the fraction of S. mitis dead cells (Fig. 2D).

FIG 2.

Live/dead bacterial viability assay by confocal microscopy. Stained in green are the viable cells, and stained in red are the dead cells. We used two control strains: E. coli and S. mitis. (A) Control S. mitis biofilm to which S. mitis cells were added. (B) Control S. mitis biofilm to which E. coli cells were added. (C) S. mitis biofilm to which P. gingivalis was added. (D) Box plot showing the results for biomass calculated using a COMSTAT v1.1 program (19). The y axis represents the ratio of dead to live cells after the addition of the different organisms indicated in the x axis. Significance was tested by a Kruskal-Willis rank sum test with an asterisk (*) representing groups with significant differences at P < 0.05. Analysis was performed for three independent biological experiments (n = 3) with a series of 20 sections. The dark line in the box represents the median. The two section in the box represent the upper and lower quartiles. Bars (whiskers) represent the maximum and minimum values in the data sets.

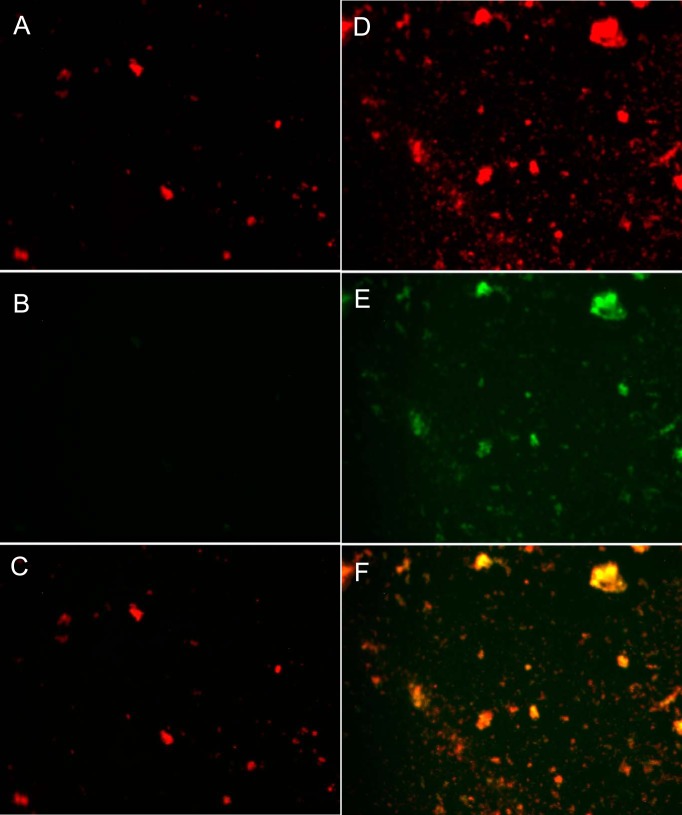

Finally, we wanted to assess whether the cell death process in S. mitis showed some of the hallmarks of a controlled cell death mechanism described in bacteria, such as fratricide (23, 24). One of the features of antibiotic-induced cell death is the fragmentation of DNA, similar to what occurs in eukaryotic apoptosis processes (20). We assessed the possibility of DNA fragmentation in S. mitis chromosome during cell death by using a TUNEL assay. Cells whose DNA have been fragmented are stained green, while cells whose DNA has not been degraded are stained red. Figure 3 shows the results for the TUNEL assay when P. gingivalis W83 was added to the S. mitis biofilm (Fig. 3D, E, and F) and when S. mitis was added as a control to the biofilm (Fig. 3A, B, and C). The addition of P. gingivalis induced the fragmentation of the chromosomal DNA in S. mitis biofilm. P. gingivalis incubated under the same conditions did not show DNA fragmentation by itself (data not shown), which confirms that the fragmentation observed in our experiments was the result of S. mitis DNA fragmentation. Moreover, in all of these experiments P. gingivalis represented a small fraction of the total cells in the communities since the incubation period of 6 h is not enough to yield a considerable amount of cells that would interfere with our observations.

FIG 3.

DNA fragmentation assay by the TUNEL method. Evidence of DNA fragmentation as measured by TUNEL was visualized via fluorescence microscopy. Cells with fragmented DNA show a green fluorescence due to the incorporation of dUTPs to the ends of the DNA fragments. We used propidium iodide (PI) as a counterstain, staining all nucleic acids in red. Original magnification, ×400. (A) S. mitis biofilm to which additional S. mitis was added stained with PI. (B) TUNEL assay on a S. mitis biofilm to which additional S. mitis was added. (C) Overlaid image of panels A and B, wherein cells positive for TUNEL are stained yellow-orange. (D) S. mitis biofilm to which P. gingivalis W83 was added, stained with PI. (E) TUNEL assay of an S. mitis biofilm to which P. gingivalis W83 was added. (F) Overlaid image of panels D and E panels, wherein cells positive for TUNEL are stained yellow-orange. We performed the experiment in triplicate (n = 3), observing 20 fields in each case.

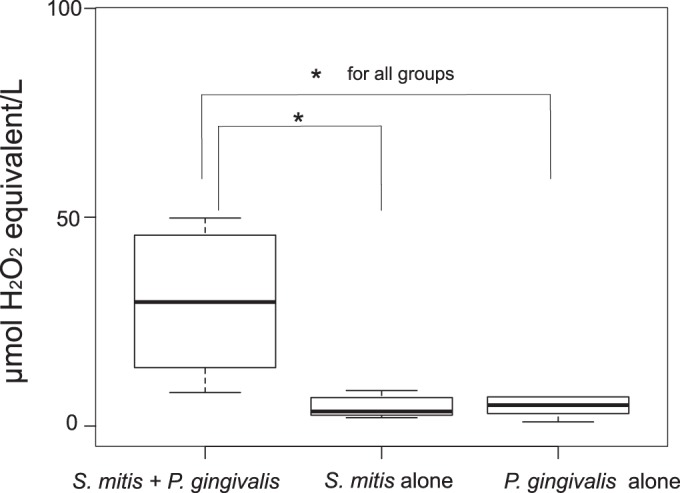

Another hallmark of programmed cell death (PCD) is the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). To test the production of these compounds, we measured the TOS of the biofilm in the presence or absence of P. gingivalis. S. mitis growing by itself under the same conditions produced low levels of ROS, while in the presence of P. gingivalis the production increase by up to 25-fold (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Effect of P. gingivalis on the total oxidant status (TOS) of the S. mitis biofilm. P. gingivalis induced the production of oxidant species in an S. mitis biofilm. The results show the average values of four independent biological experiments (n = 4), following the protocol described in Materials and Methods. The P. gingivalis biofilm was incubated for 6 h before measurement of the TOS. Three replicates were measured for each sample. Significance was tested by using the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test with an asterisk (*) representing groups with significant differences at P < 0.05. The dark line in the box represents the median. The two sections in the box represent the upper and lower quartiles. Bars (whiskers) represent the maximum and minimum values in the data sets.

DISCUSSION

In spite of our wealth of knowledge regarding the composition of the oral microbiome, we still do not completely understand the role of individual species in periodontal disease initiation and progression. Oral pathogens have been frequently identified in healthy oral samples, although in most cases at low levels (25). The fact that these pathogens are present even in healthy patients complicates the definition of what constitutes a healthy oral microbiome.

In a recent series of papers, Hajishengallis et al. and Darveau have proposed that P. gingivalis orchestrates the inflammatory response of the host by dysbiosis of the oral microbiome, changing the nature of the bacterium-bacterium and bacterium-host interactions (26–29). These researchers showed in an animal model that P. gingivalis, at low levels of colonization, was able to induce periodontitis accompanied by significant changes in the number and community organization of the oral commensal bacteria. These alterations occur soon after P. gingivalis colonization and precede to the onset of inflammatory bone loss, suggesting that dysbiosis is the cause of the disease. The obligatory participation of the commensal microbiota in disease pathogenesis was shown by the failure of P. gingivalis alone to cause periodontitis in germfree mice, despite its ability to colonize the host (27). In a previous work, we observed that the addition of the periodontal pathogens P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans to a healthy biofilm in a multispecies biofilm model caused a complete rearrangement of the expression profiles of the commensal microbiota (8).

One surprising observation of our previous study was that a large number of putative transposases were highly upregulated in L. casei and S. mitis when two periodontal pathogens were added to the biofilm. A high upregulation of transposases has been described in a previous report on the periodontal pathogen T. denticola. When this organism was growing as a biofilm, this upregulation was observed, but it did not happen during planktonic growth. Mitchell et al. concluded that there is a higher potential for genetic mobility in T. denticola biofilms than in suspension (16). In a very recent study, Kleiner et al. reported abundant transposase expression in bacterial symbionts of a gutless marine worm, and they concluded that their results reflect expression under natural environmental conditions (30). Furthermore, we observed that the effect was specific of the species added to the S. mitis biofilm. When T. forsythia was added to the biofilm, we did not observe any upregulation of the same transposases that were highly transcribed in the presence of two different strains of P. gingivalis. However, due to the slow growth of T. forsythia, we cannot discard the possibility that this organism would have an influence in S. mitis cell death when they are together for long periods of time.

Streptococci are considered the main group of early colonizers in the oral biofilm, making up over 80% of the initial plaque. Their early attachment determines the composition of late colonizers in the oral biofilm and impacts the health or disease status of the host (9, 41). Members of the S. mitis group (S. oralis, S. mitis, and S. sanguinis) are considered part of these early colonizers and have been frequently associated with oral health (7, 31). It is the uncontrolled growth of the Gram-negative component of dental plaque that leads to periodontitis. Therefore, during progression of periodontitis, there is a reduction in the fraction of streptococci present in the biofilm.

We found that the addition of at least two different strains of P. gingivalis to an S. mitis biofilm induced cell death by a still-uncharacteristic molecular mechanism. Two different mechanisms of controlled cell death have been described in bacteria: fratricide, a killing mechanism used by competent cells to acquire DNA from noncompetent sibling cells, and PCD as part of biofilm development in which a subfraction of the population commits altruistic “suicide” with the subsequent release of extracellular DNA that stabilizes the biofilm using a toxin-antitoxin system (40).

Fratricide has been extensively studied in Streptococcus pneumoniae (24), while cell death in biofilm maturation has been studied in several bacteria, including the oral pathogen Streptococcus mutans (32). Essential proteins involved in those mechanisms are CbpD, CibAB, LytA, and LytC in fratricide and CidABC, LytR, LrgAB, LytSR, and CidR in PCD (24, 33). We found that a large number of orthologues for these genes were upregulated in S. mitis biofilms when P. gingivalis was present.

In S. pneumoniae choline-binding murein hydrolases, CbpD, LytA, and LytC, constitute the lysis mechanism of fratricide. CbpD is the key component of that mechanism and also involved in competence, while LytA and LytC play auxiliary roles (24). Other proteins involved in this process are the lytic factors CibA and CibB (CibAB), which presumably constitute a two-peptide bacteriocin, and the immunity factor CibC (23). S. mitis NCTC 12261, the strain used in our experiments, contains an almost identical orthologue of CbpD in its genome, two orthologues of LytC and one orthologue of CibA, annotated as hypothetical protein in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database, but it does not have orthologues of LytA, CibB, and CibC proteins. Claverys et al. have identified a region that potentially could encode cib genes upstream of the comAB operon, but it has not been proven they do indeed encode those proteins (23). We observed a high upregulation after the addition of P. gingivalis in our metatranscriptome and RT-qPCR assay of the gene for the key protein in fratricide, cbpD. One orthologue of LytC (SM12261_0522) was also upregulated in both the metatranscriptome and the RT-qPCR results. However, the other orthologue of lytC (SM12261_1140) and cibA did not show an increase in expression after the addition of P. gingivalis. Interestingly, comGA, another gene associated with competence, was also highly upregulated in our metatranscriptomic analysis.

PCD in other organisms follows a different pathway (33–35, 42). The current accepted hypothesis is that when a biofilm matures, a subsection of the population activates a controlled process of cell death that releases nutrients and DNA which stabilizes the rest of the population in the biofilm by maintaining the biofilm structure (34, 40). The process follows a very tightly regulated pattern of expression. In Staphylococcus aureus, a well-studied Gram-positive model, cidA and lrgA genes encode orthologues hydrophobic proteins that are believed to function as a holin and antiholin, respectively. In S. mitis NCTC 12261 the gene lrgA is the homolog for cidA. The actual function of this open reading frame in S. mitis is still unknown, and in our experiments its expression was highly upregulated in the presence of P. gingivalis. In S. aureus cidB and lrgB genes also encode hydrophobic proteins whose functions are unknown (33). Interestingly, the putative homolog for lrgB in S. mitis was highly upregulated in the presence of P. gingivalis.

S. mitis does not have orthologues for all proteins linked to PCD. Bayles indicates that S. mitis has orthologues to CidAB but not to the rest of proteins involved in the PCD regulatory network (33). However, the RefSeq annotation from the NCBI of S. mitis NCTC 12261 shows that it indeed has orthologues to LytR and LrgB but does not have orthologues to CidB or LytS. However, we found that one protein, annotated LrgA, has high homology to CidA proteins and a two-component sensor kinase YesM has high homology to LytS proteins. The gene lrgB and homologs to cidA and lytS were highly upregulated in the presence of P. gingivalis both in our metatranscriptomic results (8) and by RT-qPCR analysis. The two homologs to lytR genes were not detected in the metatranscriptome results, but our RT-qPCR analysis showed the upregulation of those two genes. If lytR and lytS homologs are indeed orthologues of lytSR, they do not belong to the same operon, in contrast to what happens in S. pneumoniae.

Using two different techniques, we observed DNA fragmentation in S. mitis biofilms when P. gingivalis was added but not when S. mitis or E. coli were present in the biofilm. Chromosomal DNA fragmentation is a hallmark of cell death both in eukaryotes during apoptosis and in prokaryotes in the presence of antibiotics (20, 43). Another hallmark of PCD in bacteria is the production of ROS (20, 36). We observed that the presence of P. gingivalis in the biofilm led to the production of ROS by S. mitis, which supports the idea that P. gingivalis is directly involved in the induction of cell death in S. mitis biofilms.

It has been suggested that passive DNA fragmentation is likely to occur in microorganisms during PCD (37). However, other authors have proposed the role of specific nucleases as BapE in the process of DNA fragmentation during PCD (34). Transposases have the ability to cut DNA at specific sites, resulting in double-stranded fragments of the nucleic acid. We believe that the upregulated putative transposases may be involved in the process of DNA fragmentation during PCD in S. mitis. In E. coli the overexpression of Tn5 transposase results in filamentation and ultimately cell death (38). We would expect that a large number of simultaneously upregulated transposases would result in cell death in S. mitis as we observed. Whatever their role, these putative transposases seem to be important players in the process of S. mitis cell death. From these results, it seems as though S. mitis is using a mixed mechanism of cell death involving proteins associated with both fratricide and PCD. We do not know of any report showing DNA fragmentation as a part of the fratricide process, although it is a common feature of cell death phenotype in a variety of organisms. During fratricide DNA is released to the biofilm (23), but it is not known whether it is fragmented before releasing. Hakansson et al. showed that in an apoptosis-like death LytA plays a major role in autolysis of S. pneumoniae, and it is accompanied by DNA fragmentation; however, none of the other proteins described as important in the canonical fratricide process seemed to play a role (39).

In summary, we have shown that the addition of the periodontal pathogen P. gingivalis to an S. mitis biofilm model induced cell death of S. mitis, as well as the upregulation of a large number of transposases. The detailed mechanisms of cell death or competence-induced cell lysis of S. mitis and the environmental signals that trigger them are still unknown, but we have identified genes that could be involved in the process. More importantly, to our knowledge there are no reports showing that either PCD or fratricide is induced by the presence of another microorganism. These may be internal cellular processes caused by stresses not yet completely understood. Furthermore, we hypothesize that the upregulated proteins annotated as transposases are involved in cell death processes rather than in DNA mobilization. In support of this idea, we could not identify other proteins of transposon origin in the vicinity of the putative transposases in S. mitis, and no other nucleases were upregulated during cell death.

A genetic approach would give us direct evidence of the role of the different proteins in induced cell death of S. mitis. Nonetheless, the genetic manipulation of the S. mitis strain that we are using in our experiments has been challenging, and we are in the process of developing the molecular techniques needed to target these genes.

Unraveling the molecular mechanism by which P. gingivalis induces death on S. mitis will facilitate developing novel targeted approaches to prevention of oral diseases by maintaining a healthy biofilm. The potential impact extends beyond the study of the oral cavity because the same principles and methods potentially can be applied to other diseases where streptococci are key players that could be targeted by using the mechanisms that P. gingivalis used here to initiate cell death in an S. mitis biofilm. The impact will be significant in our understanding of the mechanisms by which P. gingivalis modifies the behavior of the oral biofilm and in designing new strategies to treat streptococcal infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01DE021553.

We are grateful to Susan Yost for reviewing the manuscript and useful comments and to Yusuke Matsuda for help on performing the TOS experiments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 May 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Paster BJ, Olsen I, Aas JA, Dewhirst FE. 2006. The breadth of bacterial diversity in the human periodontal pocket and other oral sites. Periodontol. 2000 42:80–87. 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dewhirst FE, Chen T, Izard J, Paster BJ, Tanner ACR, Yu W-H, Lakshmanan A, Wade WG. 2010. The human oral microbiome. J. Bacteriol. 192:5002–5017. 10.1128/JB.00542-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Genco RJ. 2012. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J. Dent. Res. 91:914–920. 10.1177/0022034512457373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albandar JM, Brunelle JA, Kingman A. 1999. Destructive periodontal disease in adults 30 years of age and older in the United States, 1988-1994. J. Periodontol. 70:13–29. 10.1902/jop.1999.70.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brogden KA, Guthmiller JM, Taylor CE. 2005. Human polymicrobial infections. Lancet 365:253–255. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17745-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RLJ. 1998. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 25:134–144. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.1998.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE. 2005. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5721–5732. 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frias-Lopez J, Duran-Pinedo A. 2012. Effect of periodontal pathogens on the metatranscriptome of a healthy multispecies biofilm model. J. Bacteriol. 194:2082–2095. 10.1128/JB.06328-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolenbrander PE. 2000. Oral microbial communities: biofilms, interactions, and genetic systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:413–437. 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolenbrander PE, Andersen RN, Blehert DS, Egland PG, Foster JS, Palmer RJJ. 2002. Communication among oral bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:486–505. 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.486-505.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christopher AB, Arndt A, Cugini C, Davey ME. 2010. A streptococcal effector protein that inhibits Porphyromonas gingivalis biofilm development. Microbiol. Read. Engl. 156:3469–3477. 10.1099/mic.0.042671-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tenorio EL, Klein BA, Cheung WS, Hu LT. 2011. Identification of interspecies interactions affecting Porphyromonas gingivalis virulence phenotypes. J. Oral Microbiol. 2011:3. 10.3402/jom.v3i0.8396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang B, Wu J, Lamont RJ, Lin X, Xie H. 2009. Negative correlation of distributions of Streptococcus cristatus and Porphyromonas gingivalis in subgingival plaque. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3902–3906. 10.1128/JCM.00072-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook GS, Costerton JW, Lamont RJ. 1998. Biofilm formation by Porphyromonas gingivalis and Streptococcus gordonii. J. Periodontal Res. 33:323–327. 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1998.tb02206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Periasamy S, Kolenbrander PE. 2009. Mutualistic biofilm communities develop with Porphyromonas gingivalis and initial, early, and late colonizers of enamel. J. Bacteriol. 191:6804–6811. 10.1128/JB.01006-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell HL, Dashper SG, Catmull DV, Paolini RA, Cleal SM, Slakeski N, Tan KH, Reynolds EC. 2010. Treponema denticola biofilm-induced expression of a bacteriophage, toxin-antitoxin systems and transposases. Microbiology 156:774–788. 10.1099/mic.0.033654-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinniment SL, Wimpenny JW, Adams D, Marsh PD. 1996. Development of a steady-state oral microbial biofilm community using the constant-depth film fermenter. Microbiology 142(Pt 3):631–638. 10.1099/13500872-142-3-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morillo JM, Lau L, Sanz M, Herrera D, Martín C, Silva A. 2004. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction based on single copy gene sequence for detection of periodontal pathogens. J. Clin. Periodontol. 31:1054–1060. 10.1111/j.1600-051x.2004.00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heydorn A, Nielsen AT, Hentzer M, Sternberg C, Givskov M, Ersbøll BK, Molin S. 2000. Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiol. Read. Engl. 146(Pt 10):2395–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dwyer DJ, Camacho DM, Kohanski MA, Callura JM, Collins JJ. 2012. Antibiotic-induced bacterial cell death exhibits physiological and biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis. Mol. Cell 46:561–572. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erel O. 2005. A new automated colorimetric method for measuring total oxidant status. Clin. Biochem. 38:1103–1111. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honma K, Mishima E, Sharma A. 2011. Role of Tannerella forsythia NanH sialidase in epithelial cell attachment. Infect. Immun. 79:393–401. 10.1128/IAI.00629-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Claverys J-P, Martin B, Håvarstein LS. 2007. Competence-induced fratricide in streptococci. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1423–1433. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eldholm V, Johnsborg O, Haugen K, Ohnstad HS, Håvarstein LS. 2009. Fratricide in Streptococcus pneumoniae: contributions and role of the cell wall hydrolases CbpD, LytA, and LytC. Microbiology 155:2223–2234. 10.1099/mic.0.026328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Segata N, Haake SK, Mannon P, Lemon KP, Waldron L, Gevers D, Huttenhower C, Izard J. 2012. Composition of the adult digestive tract bacterial microbiome based on seven mouth surfaces, tonsils, throat and stool samples. Genome Biol. 13:R42. 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. 2012. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 27:409–419. 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hajishengallis G, Liang S, Payne MA, Hashim A, Jotwani R, Eskan MA, McIntosh ML, Alsam A, Kirkwood KL, Lambris JD, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. 2011. Low-abundance biofilm species orchestrates inflammatory periodontal disease through the commensal microbiota and complement. Cell Host Microbe 10:497–506. 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. 2012. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:717–725. 10.1038/nrmicro2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darveau RP. 2010. Periodontitis: a polymicrobial disruption of host homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:481–490. 10.1038/nrmicro2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleiner M, Young JC, Shah M, VerBerkmoes NC, Dubilier N. 2013. Metaproteomics reveals abundant transposase expression in mutualistic endosymbionts. mBio 4:e00223-13. 10.1128/mBio.00223-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucas VS, Beighton D, Roberts GJ. 2000. Composition of the oral streptococcal flora in healthy children. J. Dent. 28:45–50. 10.1016/S0300-5712(99)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dufour D, Lévesque CM. 2013. Cell death of Streptococcus mutans induced by a quorum-sensing peptide occurs via a conserved streptococcal autolysin. J. Bacteriol. 195:105–114. 10.1128/JB.00926-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayles KW. 2007. The biological role of death and lysis in biofilm development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:721–726. 10.1038/nrmicro1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rice KC, Bayles KW. 2008. Molecular control of bacterial death and lysis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72:85–109. 10.1128/MMBR.00030-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bayles KW. 2014. Bacterial programmed cell death: making sense of a paradox. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12:63–69. 10.1038/nrmicro3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. 2007. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell 130:797–810. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dominiak DM, Nielsen JL, Nielsen PH. 2011. Extracellular DNA is abundant and important for microcolony strength in mixed microbial biofilms. Environ. Microbiol. 13:710–721. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinreich MD, Yigit H, Reznikoff WS. 1994. Overexpression of the Tn5 transposase in Escherichia coli results in filamentation, aberrant nucleoid segregation, and cell death: analysis of E. coli and transposase suppressor mutations. J. Bacteriol. 176:5494–5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hakansson AP, Roche-Hakansson H, Mossberg A-K, Svanborg C. 2011. Apoptosis-like death in bacteria induced by HAMLET, a human milk lipid-protein complex. PLoS One 6:e17717. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webb JS, Thompson LS, James S, Charlton T, Tolker-Nielsen T, Koch B, Givskov M, Kjelleberg S. 2003. Cell death in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 185:4585–4592. 10.1128/JB.185.15.4585-4592.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kreth J, Merritt J, Qi F. 2009. Bacterial and host interactions of oral streptococci. DNA Cell Biol. 28:397–403. 10.1089/dna.2009.0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rice KC, Bayles KW. 2003. Death's toolbox: examining the molecular components of bacterial programmed cell death. Mol. Microbiol. 50:729–738. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.t01-1-03720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernández JL, Cartelle M, Muriel L, Santiso R, Tamayo M, Goyanes V, Gosálvez J, Bou G. 2008. DNA fragmentation in microorganisms assessed in situ. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:5925–5933. 10.1128/AEM.00318-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]