Abstract

Antigen-presenting cell (APC) plasticity is critical for controlling inflammation in metabolic diseases and infections. The roles that pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) play in regulating APC phenotypes are just now being defined. We evaluated the expression of PRRs on APCs in mice infected with the helminth parasite Schistosoma mansoni and observed an upregulation of CD14 expression on macrophages. Schistosome-infected Cd14−/− mice showed significantly increased alternative activation of (M2) macrophages in the livers compared to infected wild-type (wt) mice. In addition, splenocytes from infected Cd14−/− mice exhibited increased production of CD4+-specific interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-13 and CD4+Foxp3+IL-10+ regulatory T cells compared to cells from infected wt mice. S. mansoni-infected Cd14−/− mice also presented with smaller liver egg granulomas associated with increased collagen deposition compared to granulomas in infected wt mice. The highest expression of CD14 was found on liver macrophages in infected mice. To determine if the Cd14−/− phenotype was in part due to increased M2 macrophages, we adoptively transferred wt macrophages into Cd14−/− mice and normalized the M2 and CD4+ Th cell balance close to that observed in infected wt mice. Finally, we demonstrated that CD14 regulates STAT6 activation, as Cd14−/− mice had increased STAT6 activation in vivo, suggesting that lack of CD14 impacts the IL-4Rα-STAT6 pathway, altering macrophage polarization during parasite infection. Collectively, these data identify a previously unrecognized role for CD14 in regulating macrophage plasticity and CD4+ T cell biasing during helminth infection.

INTRODUCTION

Schistosoma mansoni is a helminth parasite of humans that biases the host immune system to CD4+ Th2-type responses and polarizes macrophages to an M2 phenotype. During the acute stage (5 to 7 weeks) of infection, immune responses are largely of the CD4+ Th1 type, associated with increased numbers of classically activated macrophages producing interleukin-12 (IL-12), IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and nitric oxide (NO) (1). The early Th1 phase is followed by a short period of mixed Th1 and Th2 responses, which shifts to a dominant Th2 response by 9 to 12 weeks postinfection coincident with a shift in macrophage phenotype to M2. M2 macrophages play a direct and critical role in fibrosis, maintenance of granulomas, tissue repair, and host survival (2, 3).

Phenotypic plasticity plays a large role in how macrophages regulate immune responses during infection. M1 (classical) macrophage polarization is driven by pathogen molecule ligation of pattern recognition receptors, and/or by gamma interferon (IFN-γ), inflammasomes, or danger signals (4, 5). M2 or alternative activation is driven by macrophage ligation of IL-4, IL-13, or parasite products, resulting in cells that mediate anti-inflammatory responses (6). Expression levels of RELMα, Ym1, and Arg1 measure alternative activation, while NO, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 are classical activation markers (6).

In schistosome infection, early proinflammatory responses may be due to adult worm and/or egg antigens ligating Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) on macrophages (7–9). Among TLRs, TLR4 is unique, as it can generate both TIR domain-containing adapter-inducing IFN-β (TRIF)- and MyD88-dependent signaling cascades. TLR4 requires its coreceptor CD14 in initiating TRIF-dependent, but not MyD88-dependent, signaling (10). In this regard, CD14 facilitates endocytosis of TLR4 via a Syk-PLCγ2-Ca(2+) pathway enhancing intracellular TRIF-dependent signaling (11). CD14 uses the same Syk/PLCγ2/Ca(2+)/calcineurin) pathway to trigger TLR-independent signaling (12). CD14 interactions are not limited to TLR4. Recent studies show that CD14 directly interacts with TLR3 agonists (double-stranded RNA [dsRNA]) to drive proinflammatory responses in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (13, 14). Further, CD14 was shown to play a crucial role in nucleic acid-mediated TLR7 and -9 activation during viral infection (13, 14). Taken together, CD14 performs multiple functions in recognizing a wide range of pathogen products as well as initiation of TLR-dependent and -independent signaling, suggesting that CD14 may function to regulate macrophage M1/M2 plasticity and/or the Th1-Th2 balance.

Here we examined the role of CD14 in regulation of host immune responses and liver granuloma pathology during S. mansoni infection of mice. We observed that S. mansoni-infected Cd14−/− mice had dramatically enhanced alternative activation of macrophages in hepatic granulomas compared to wild-type (wt) mice and that hepatic egg granulomas were smaller, with greater collagen deposition, than those seen in wt mice. In addition to macrophages, Cd14−/− liver granuloma eosinophils were more alternatively activated than in wt mice. CD4+ Th2 recall responses of splenocytes from schistosome-infected Cd14−/− mice were also elevated compared to those of cells from infected wt mice. To test the role of CD14 on macrophages in regulating alternative activation and CD4+ Th2-type responses, we performed adoptive transfer studies and observed that transfer of wild-type macrophages into egg-sensitized and challenged Cd14−/− mice was sufficient to normalize alternative activation and CD4+ Th responses. These findings define a role of CD14 in the regulation of macrophage polarization as well as adaptive immune induction and inflammation during schistosome infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

The guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals was in accordance with the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AALAC) as well as the Animal Welfare Act (AWA) and other applicable federal and state guidelines. All animal work presented here was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Georgia (AUP no. A2009-04-086).

Mice, parasites, and infection.

C57BL/6 and Cd14−/− mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Mice were housed at the Coverdell Rodent Vivarium facility (University of Georgia) under specific-pathogen-free conditions following institutional guidelines. Mice were infected with S. mansoni by subcutaneous injection of 50 to 60 cercariae. Mice were euthanized at 7 and 12 weeks postinfection, and livers were removed and used for RNA isolation and immunohistochemistry. For the adoptive transfer experiment, using the S. mansoni egg sensitization/challenge model, approximately 5,000 S. mansoni eggs were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) simultaneously with 1 × 106 adherent peritoneal macrophages (APMs) into wt and Cd14−/− mice. Two weeks later, mice were intravenously (i.v.) challenged with S. mansoni eggs coadministered with 1 × 106 APMs from naive wt or Cd14−/− mice, followed by an additional i.v. injection of 1 × 106 adherent peritoneal macrophages 3 days prior to the end of the experiment. Adherent peritoneal macrophages were obtained from the peritoneal cavities of naive wt and Cd14−/− mice by saline lavage, followed by plastic adherence of peritoneal exudate cells for 2 to 4 h at 37°C. Then, the supernatants were discarded, and the APMs were collected, washed 3 times with warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), counted, and used for adoptive transfer experiments. Groups were as follows: group I, wt mice receiving wt APMs; group II, Cd14−/− mice receiving wt APMs; and group III, Cd14−/− mice receiving Cd14−/− APMs. Single-cell suspensions from mediastinal lymph nodes of mice were assayed for CD4+ intracellular Th2 cytokines by flow cytometry.

Worm and egg burden in S. mansoni-infected mice.

Livers from infected wt and Cd14−/− mice were harvested, weighed, and then incubated with 4% KOH overnight at 37°C. The eggs obtained after KOH digestion were counted using a light microscope, and the egg burdens were calculated as the number of eggs per gram of liver tissue. For worm burdens, mice were anesthetized by injecting 2% tribromoethanol (TBE) and then perfused by inserting a 20-gauge needle into the left ventricle and pumping saline containing heparin (15). Worms were collected from the hepatic portal vein, washed, and placed in a petri dish, and males and females were counted.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Liver and lung tissues were homogenized using Tissue Lyzer (Qiagen), and total RNA was purified using an RNeasy spin column (Qiagen). One microgram of RNA was used to perform reverse transcription (RT)-PCR followed by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) using primers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) against specific genes, the Universal PCR master mix, and the ABI Prism 7900 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Expression was normalized to GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) endogenous control, and fold expression was measured by comparison to the expression of the uninfected controls.

ELISA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to measure the production of cytokines in cell culture supernatants as well as antibodies in the sera of mice. For IL-4, IL-13, and IFN-γ, a sandwich ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). Antigen-specific IgG1 was measured by using 10 μg/ml of schistosome soluble egg antigen (SEA) to coat 96-well plates overnight and then washing and blocking the plates with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Serum was added to the plates after the washing and blocking, and the plates were incubated for 2 h at room temperature, washed with PBS-Tween, and then probed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-IgG1 antibody (BD Biosciences, USA). After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, plates were washed and developed using TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) substrate (Ebiosciences, USA). Total IgE in the serum of each mouse was measured by performing a sandwich ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA).

Tissue and single-cell suspension preparation, IHC, and staining.

Livers were isolated from uninfected and infected mice. The identical liver lobe was removed from each mouse and fixed in 4% formalin overnight. Tissue samples were prepared for sectioning by the Department of Pathology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia. Slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Masson's trichrome or processed for immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining. Briefly, for IHC, we stained liver sections with the following antibodies: anti-Ym1 (Stem Cell Technology) and anti-RELMα (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), followed by incubation with biotin-conjugated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Sections were subsequently incubated with streptavidin-HRP (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Single-cell suspensions were prepared from livers and lungs from naive, egg-injected, or S. mansoni-infected mice. Lungs and livers were digested with collagenase (1 mg/ml) for 30 min to 1 h at 37°C. Digestion was stopped using 2 mM EDTA, and cells were passed through a 100-μm strainer, washed, and used for flow cytometer staining.

Flow cytometry.

For cytokine analysis, splenocytes from each mouse were processed and incubated with 50 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 500 ng/ml ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and monensin (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were then surface stained with fluorescein-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody (Ebiosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), fixed, permeabilized, and then stained intracellularly with antibodies against IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-10, IFN-γ, and IL-17 (Ebiosciences, San Diego, CA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Additional aliquots of cells were stained with anti-CD4 surface antibody and intracellular anti-Foxp3 antibody (Ebiosciences, San Diego, CA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. For RELMα expression, PMs were surface stained with antibody against F480 (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC), siglecF (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), Gr1 (BD Biosciences), or CD11b (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) followed by intracellular staining with antibodies against RELMα (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab, West Grove, PA). Cells were acquired and analyzed on a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Data obtained were analyzed using Flowjo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism (GraphPad Software), and P values were obtained by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) Tukey's test for multiple-group comparisons and two-tailed Student's t test for two-group comparisons.

RESULTS

Schistosome infection and schistosome eggs upregulate expression of CD14.

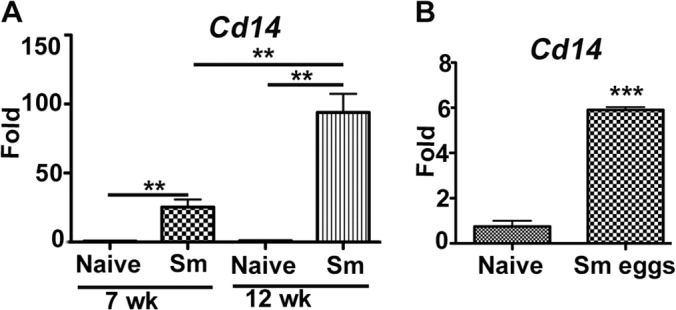

Immune responses in schistosome-infected mice switch from an initial inflammatory Th1 type to subsequent anti-inflammatory and Th2 type, evident by an increase in alternatively activated macrophages. CD14 is a coreceptor for TLR-initiated proinflammatory responses on innate immune cells, particularly macrophages. Therefore, we asked if CD14 expression changes on cells and tissues as a result of schistosome infection. Using quantitative RT-PCR, we compared the expression levels of CD14 in liver tissue from naive and schistosome-infected mice at 7 and 12 weeks postinfection. This analysis revealed striking, approximately 30- and 100-fold increases in liver expression of the Cd14 gene at 7 and 12 weeks postinfection, respectively, compared to naive liver tissue (Fig. 1A). We next asked if injection of schistosome eggs would be sufficient to upregulate CD14. Seven days following intraperitoneal injection of eggs, adherent peritoneal macrophages showed an approximate 6-fold increase in expression of the Cd14 gene in comparison to APMs harvested from naive mice (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

CD14 is upregulated in response to Schistosoma mansoni (Sm) infection or schistosome egg antigens. (A) Total RNA was extracted from livers of naive mice or mice infected with S. mansoni for 7 and 12 weeks (n = 5/cohort). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using primers specific to gene Cd14. (B) Approximately 5,000 S. mansoni eggs were injected intraperitoneally into C57BL/6 mice (n = 5). On day 7 postinjection, peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) were collected and incubated in plastic tissue culture plates for 2 h at 37°C, and then adherent cells were harvested and processed for total RNA isolation. Expression of Cd14 was assessed using qRT-PCR in naive and egg-injected groups. Gene expression was analyzed in fold changes expressed over naive controls after normalization with GAPDH. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA Tukey's multiple-comparison test (A) or Graphpad Quick Cals Student's t test (B). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Results (means ± standard errors of the means [SEM]) represent at least 3 independent experiments.

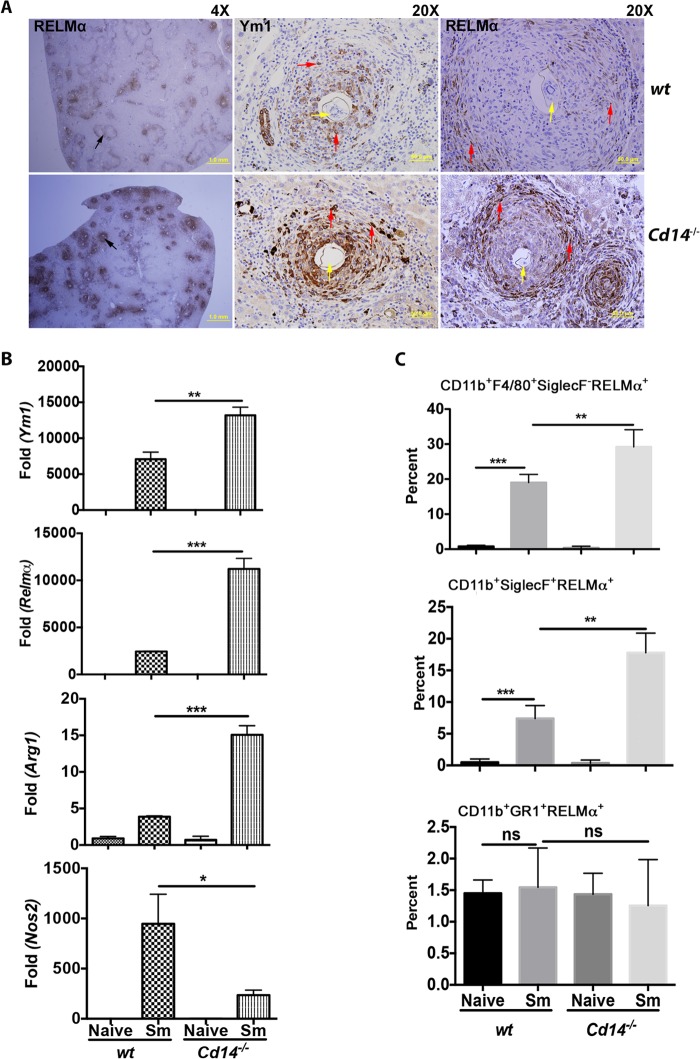

Increased recruitment of alternatively activated cells in livers of CD14-deficient mice.

The observation that CD14 expression was increased in livers of schistosome-infected mice suggested that CD14 might have regulatory roles during infection. To investigate this, we compared immune responses and measured egg granuloma-mediated pathology at 12 weeks postinfection of cells and tissues from S. mansoni-infected wt and Cd14−/− mice. We measured the alternative activation (AA) of cells by staining for Ym1 and RELMα on liver sections. We found that staining for these AA markers in hepatic granulomas of infected Cd14−/− mice was so pronounced that differences in RELMα expression in wt and Cd14−/− mice could be seen at low magnification (Fig. 2A). Higher magnification of sections showed significantly greater expression of both Ym1 and RELMα in granulomas of infected Cd14−/− mice (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

Enhanced alternative activation in liver egg granulomas in Cd14−/− mice. C57BL/6 (n = 5) and Cd14−/− mice (n = 5) were infected with S. mansoni. Twelve weeks postinfection, mice were sacrificed and identical liver lobes were isolated from each mouse and processed for immunohistochemistry using anti-Ym1 and anti-RELMα antibodies. (A) Liver section at magnification of ×4 or ×20 (as indicated) showing granulomas (black arrows) stained for alternative activation markers RELMα and Ym1 (red arrows) expressed by granulocytes (macrophages) in egg granulomas (yellow arrows). (B) qRT-PCR performed with total RNA extracted from liver tissue of naive or S. mansoni-infected (Sm) mice using primers specific to genes Arg1, Ym1, Relmα, or Nos2. Gene expression was analyzed in fold changes expressed over naive controls after normalization with GAPDH. (C) Single-cell suspensions were prepared to measure RELMα expression from granulocytes of infected livers by flow cytometry. Livers (naive and S. mansoni infected) were digested with collagenase (1 mg/ml) to obtain single-cell suspensions and stained for surface (CD11b, F4/80, Siglec F, and Gr1) and intracellular (RELMα) markers. Expression of RELMα was measured in cells gated as eosinophils (CD11b+SiglecF+), macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+SiglecF−), and neutrophils (CD11b+Gr1+) (as shown in Fig. 6; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA Tukey's multiple-comparison test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Results represent at least 2 or 3 independent experiments.

Using quantitative RT-PCR, we detected 2- to 3-fold increases in the expression of AA markers Ym1, Relmα, and Arg1 in the livers of infected Cd14−/− mice compared to wt controls (Fig. 2B). Conversely, the expression of Nos2 (mRNA), a molecule associated with classical activation of macrophages, was decreased in livers of infected Cd14−/− mice compared to wt controls (Fig. 2B). Together, these observations show that CD14 regulates the expression of AA markers at both the protein and mRNA levels in S. mansoni-infected mice.

We next tested for differences in alternative activation of cell populations in granulomas of infected wt and Cd14−/− mice. Single-cell suspension from the livers of infected wt and Cd14−/− mice were stained with surface markers for macrophages, eosinophils, and neutrophils, as shown in Fig. S2A and B in the supplemental material. Both eosinophils and macrophages express CD11b and F4/80 markers (see Fig. 6; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). However, marker siglecF can be used to differentiate eosinophils from the macrophage population (see Fig. 6; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Thus, eosinophils can be identified as CD11b+F4/80+SiglecF+ or CD11b+SiglecF+, F4/80 being unessential to determine eosinophil population in livers, similar to what was reported by by Goh et al. (16) (see Fig. S2B and D in the supplemental material). As shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material, eosinophil and macrophage populations could also be differentiated by their distinct profiles, with eosinophils (CD11b+F4/80+SiglecF+) showing high side scatter (SSC) compared to macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+SiglecF−/low) on forward side scatter (FSC)/SSC plots (see Fig. S2C in the supplemental material), similar to the observation made by Voehringer et al. (17). We compared the alternative activation of macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+SiglecFlow) and eosinophils (CD11b+F4/80+SiglecF+) in the livers of infected Cd14−/− and wt mice (see Fig. S2A and B in the supplemental material). Both macrophage and eosinophil populations were more polarized to alternative activation in liver granulomas from infected Cd14−/− mice than in granulomas in the infected wt controls (Fig. 2C), as determined by RELMα expression. We found that infection of mice with S. mansoni had no effect on the alternative activation of neutrophils (CD11b+F4/80−Ly6G/C+). These results show that lack of CD14 expression is associated with increased alternative activation of macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+SiglecF−) and eosinophils (CD11b+F4/80+SiglecF+) in liver granulomas of infected Cd14−/− mice.

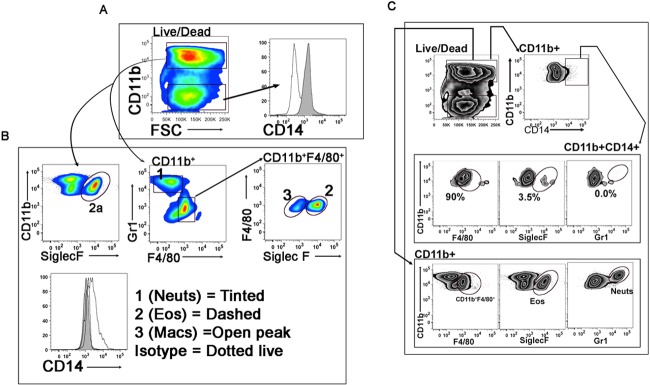

FIG 6.

CD14 expression is largely restricted to macrophages. Expression of CD14 on liver granulocytes analyzed by flow cytometry. Single-cell suspensions from livers were prepared as described in Materials and Methods from C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) infected with S. mansoni for 12 weeks and surface stained for CD11b, F4/80, SiglecF, Gr1, and CD14 by a flow cytometer. (A) Live cells were gated for CD11b+ and CD11b− populations. Expression of CD14 was first determined in CD11b+ (tinted peak) and CD11b− (open peak) liver cells. (B) CD11b+ cells were further gated for Gr1 and F4/80 expression to separate out neutrophil (CD11b+Gr1+) and CD11b+F4/80+ populations. The CD11b+F4/80+ population was further gated for SiglecF expression with SiglecF+ cells as eosinophils and SiglecF-low or -negative (SiglecF−) cells as macrophages. Expression of CD14 was determined in neutrophil (1), eosinophil (2), and macrophage (3) populations. (C) To determine the percentages of CD14+ macrophages, eosinophils, or neutrophils, CD11b+ cells were gated for CD14 expression. CD11b+CD14+ cells were further gated for F4/80, SiglecF, and Gr1 expression (upper panel). The positive gate (control) for each population was determined by gating CD11b+ cells with their respective markers (Gr1, F4/80, or SiglecF) (lower panel). The same gates were then applied to the CD11b+CD14+ populations to determine the percentage of CD14-positive macrophage (CD14+F4/80+SiglecF−), eosinophil (CD14+SiglecF+), or neutrophil (CD14+Gr1+) populations (upper panel). Results represent at least 3 independent experiments.

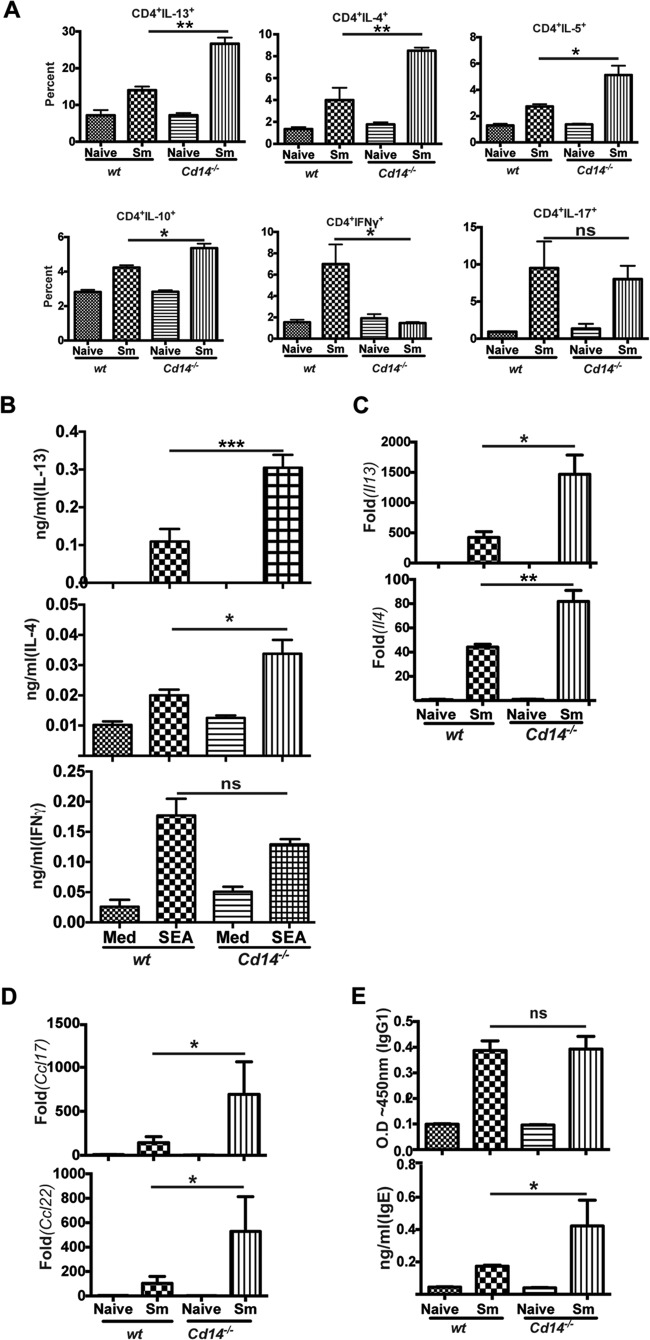

CD14 deficiency enhances Th2 responses in schistosome-infected mice.

We next evaluated the influence of CD14 on induction of Th1 and Th2 responses in schistosome-infected wt and Cd14−/− mice. Flow cytometric analysis revealed significant increases in IL-13-, IL-4-, IL-5-, and IL-10-producing splenic CD4+ T cells from Cd14−/− mice compared to wt controls (Fig. 3A). Splenocytes from schistosome-infected Cd14−/− mice had increased numbers of CD4+IL-4+ or CD4+IL-13+ cells compared to splenocytes from infected wt mice (see Fig. S4A and B in the supplemental material). Similarly, we found significantly greater amounts of IL-13 and IL-4 from schistosome egg antigen (SEA)-stimulated splenocytes from S. mansoni-infected Cd14−/− mice compared to splenocytes from infected wt mice (Fig. 3B). Coincident with the increased production of Th2 cytokines, there were fewer IFN-γ-producing splenic CD4+ T cells in Cd14−/− mice than in wt mice (Fig. 3A). However, the levels of IFN-γ production from SEA-stimulated splenocytes were similar for S. mansoni-infected Cd14−/− mice and wt mice (Fig. 3B). Further, the percentages of IL-17-producing splenic CD4+ T cells were not significantly altered between S. mansoni-infected Cd14−/− and wt mice (Fig. 3A). CD14 deficiency also influenced the ability to drive Th2-type responses in vitro. Using a DC-CD4+ T-cell coculture, we found that SEA-stimulated Cd14−/− bone marrow dendritic cells (BMDCs) were able to drive greater CD4+ T cell production of IL-4 than wt BMDCs (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Further, quantitative RT-PCR of whole liver tissue showed ∼2- and 3-fold increases in expression of genes il4 and il13, respectively, in Cd14−/− mice compared to wt counterparts (Fig. 3C). In addition to Th2-type cytokines, liver tissues from Cd14−/− mice showed increased expression of the Th2-promoting chemokines Ccl17 and Ccl22 compared to infected wt mice (Fig. 3D). As a correlate to the observed increases in Th2 responses, infected Cd14−/− mice had elevated levels of serum IgE compared to wt mice, though antigen-specific IgG1 levels were comparable (Fig. 3E). These observations agree with earlier clinical and experimental studies demonstrating an inverse correlation of CD14 expression with Th2-associated IgE (18, 19).

FIG 3.

S. mansoni-infected Cd14−/− mice have enhanced Th2 responses. (A) Splenocytes were prepared from naive and S. mansoni-infected (12 weeks) (Sm) wild-type C57BL/6 (n = 5) and Cd14−/− mice (n = 5). Cells were then surface stained with antibodies to CD4 and intracellular cytokines IL-4, IL-13, IL-5, IL-10, IL-17, and IFN-γ and analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentages of CD4+ T-cell-specific cytokines (among total CD4+ T cells) are shown. (B) Splenocytes were stimulated with SEA (25 μg/ml) at 37°C for 72 h, and then supernatants were collected. Cytokine production was assayed by ELISA. Med, medium. (C, D) qRT-PCR was performed specific to cytokines (genes Il-4 and Il-13) and chemokines (genes Ccl17 and Ccl22), as indicated, using total RNA extracted from livers of naive or schistosome-infected mice. Gene expression was analyzed as fold changes over naive controls after normalization with GAPDH. (E) Production of SEA-specific IgG1 and total IgE in the sera of naive or infected mice determined by ELISA. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA Tukey's multiple-comparison test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significant. Results (means ± SEM) represent 3 or more independent experiments.

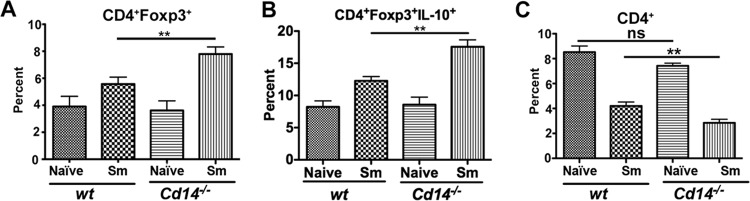

CD14 deficiency during schistosome infection leads to loss of CD4 + T cells, coincident with increases in regulatory T cells.

Schistosome infection increases the overall frequency of regulatory T cells (20). Therefore, we evaluated the influence of CD14 expression on regulatory T cells in S. mansoni-infected mice. We observed a modest increase (>2%) in the frequency of CD4+Foxp3+ T cells (Fig. 4A) as well as IL-10-producing CD4+Foxp3+ T cells among total CD4+Foxp3+ T cells in Cd14−/− splenocytes compared to wt controls at 12 weeks postinfection (Fig. 4B). We also observed increased numbers of total CD4+Foxp3+ T cells in the spleens of Cd14−/− mice compared to infected wt mice (see Fig. S4C in the supplemental material). Flow cytometric analysis of splenocytes revealed that 12-week-infected Cd14−/− mice had a significant reduction in percentage of total CD4+ T cells compared to wt mice (Fig. 4C). Loss of CD4+ T cells as a consequence of helminth infection has previously been reported (21, 22). These observations suggest that the enhanced Th2-type responses in CD14-deficient mice may contribute to the lower frequency of total CD4+ T cells in the spleens.

FIG 4.

Cd14−/− mice have an increased frequency of CD4+Foxp3+ T cells coincident with a decrease in the total CD4+ T-cell population. Splenocytes from naive (n = 5) or S. mansoni-infected (Sm) mice (12 weeks postinfection) (C57BL/6 and Cd14−/−; n = 5) were surface stained using fluorescence-conjugated antibodies against CD4 followed by intracellular staining for Foxp3 or IL-10 protein, acquired by flow cytometry using a BD LSR II instrument, and analyzed using FlowJo (Treestar Inc., OR, USA). Frequencies of CD4+Foxp3+ of total CD4+ T cells (A), CD4+Foxp3+IL-10+ of total CD4+Foxp3+ T cells (B), and total CD4+ T-cell populations (C). Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA Tukey's multiple-comparison test. **, P < 0.01; ns, not significant. Results (means ± SEM) are representative of 3 or more independent experiments.

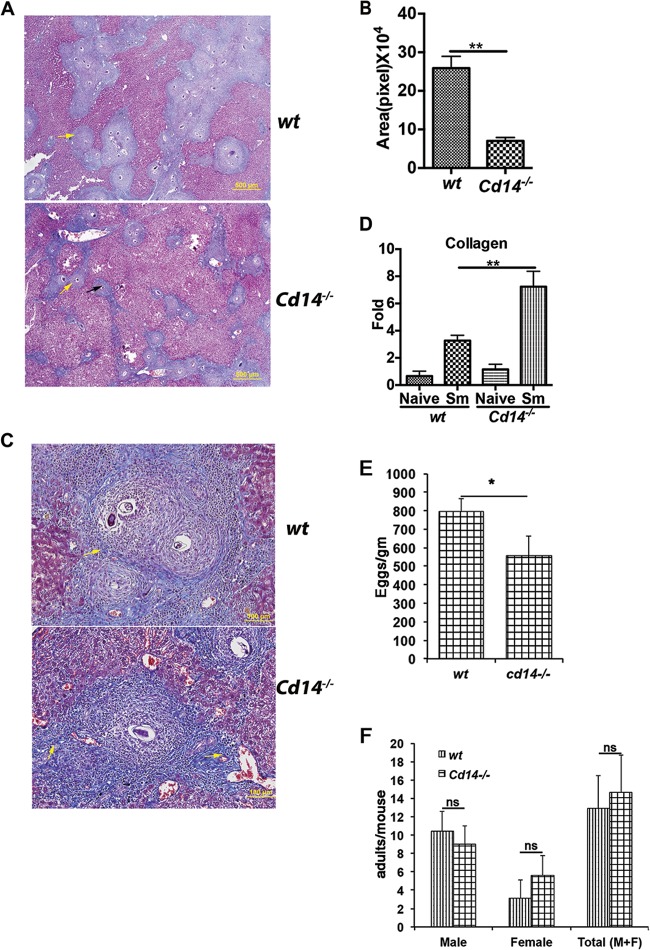

Cd14−/− mice have smaller and more fibrotic granulomas than wt mice.

Innate immune receptors on antigen-presenting cells influence the initiation and development of CD4+ T cell responses and subsequent egg granuloma-induced liver pathology during S. mansoni infection (23). To determine if the aforementioned alterations in cytokine, chemokine, and CD4+ T-cell responses in Cd14−/− mice altered liver pathology during S. mansoni infection, we performed histopathologic analysis of hepatic granulomas. Stained liver sections showed considerably smaller hepatic egg granulomas in Cd14−/− mice than in wt mice (Fig. 5A and B). Masson's trichrome staining revealed an intense staining of collagen in liver granulomas of Cd14−/− mice compared to wt controls, suggesting that granulomas in Cd14−/− mice are more fibrotic than granulomas of wt mice (Fig. 5A and C). The elevated expression of collagen seen in liver sections of infected Cd14−/− mice was confirmed by qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 5D). Thus, CD14 plays a regulatory role during schistosome egg antigen and immune cell interactions that influences the function and organization of immune cells in egg granulomas.

FIG 5.

Liver granulomas in Cd14−/− mice are smaller and more fibrotic than in wt mice, with altered cellularity. (A) Livers from S. mansoni-infected (Sm) mice (C57BL/6, n = 5, and Cd14−/−, n = 5) were fixed and then sectioned and stained with Masson's trichrome. At low magnification, intense blue staining of collagen (yellow arrow) represents the size of granulomas in liver sections. (B) Collagen fibers, indicated by blue staining, surrounding each granuloma were used to determine the sizes of granulomas using DP2-BSW software (Olympus, USA). (C) Liver sections at high magnification (×20, optical zoom) show a single granuloma intensely stained (yellow arrows) with Masson's trichrome blue dye. (D) qRT-PCR was performed using primers specific to collagen with total RNA extracted from a specific liver lobe of each mouse. (E) Reduced egg burden in the livers of S. mansoni-infected (Sm) Cd14−/− mice. To evaluate egg deposition in the livers of infected wt and Cd14−/− mice, 12 weeks postinfection, livers of wt (n = 10) and Cd14−/− (n = 10) mice were harvested, weighed, and processed for KOH digestion, as described in Materials and Methods. Eggs obtained from KOH digestion were counted under a light microscope, and the number of eggs/g of liver tissue was determined. (F) Twelve-week postinfection, wt and Cd14−/−-infected mice (n = 10) were anesthetized and then perfused by pumping heparinized saline via the left ventricle of the heart. Adult worms were collected from the cut, hepatic portal vein and then counted, as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers of males, females, or total (M+F) worms per mouse were determined. Statistical significance was calculated using Graphpad Quick Cals Student's t test (B and E) and one-way ANOVA Tukey's multiple-comparison test (D and F). Results (means ± SEM) represent at least 2 or 3 independent experiments. ns, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Results (means ± SEM) represent 3 or more independent experiments.

In addition to measuring differences in immune responses and liver granulomas as a function of CD14, we also compared egg and worm burdens in S. mansoni-infected wt and Cd14−/− mice. As shown in Fig. 5E and F, we saw a reduced number of eggs in the livers of Cd14−/− mice but no differences in the number of adult worms compared to those in infected wt mice.

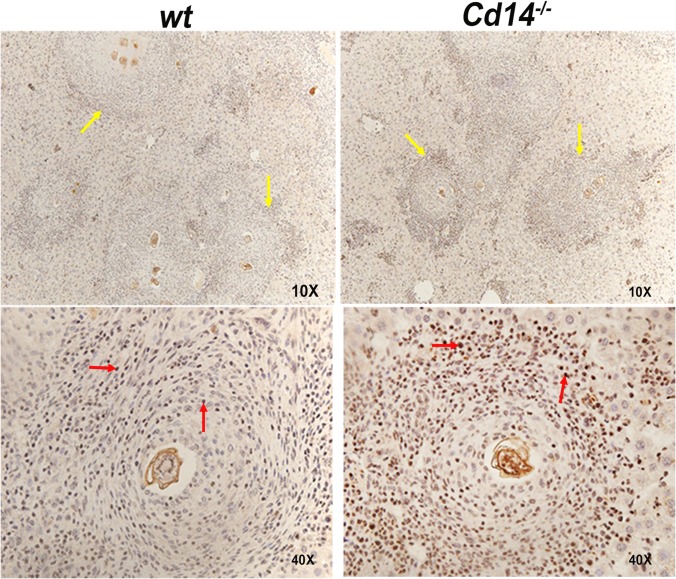

Macrophages are the major source of CD14 in liver granulomas of S. mansoni-infected mice.

Next, we sought to define which cells in schistosome egg granulomas express CD14. Granulocytes (CD11b+) are recruited to egg granulomas in livers of infected mice, in contrast to what is seen in the livers of uninfected mice (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Macrophages, eosinophils, neutrophils, and some lymphocytes are present in liver egg granulomas of S. mansoni-infected mice (24). Therefore, to analyze the expression of CD14 on granulocytes in liver egg granulomas, we prepared single-cell suspensions of liver granulomas and then stained them with surface markers against macrophages, eosinophils, and neutrophils as well as CD14 (Fig. 6). We found that only CD11b+ granulocytes had high levels of CD14 expression, compared to granulocytes with low expression of CD11b (CD11b−) (Fig. 6A). When the CD11b+ population was gated for macrophage, eosinophil, and neutrophil populations (following the gating strategy shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), we found that the majority of macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+SiglecFlow) expressed CD14, compared to a lack, or minimal expression, of CD14 on CD11b+F4/80+SiglecF+ eosinophils and CD11b+F4/80−Ly6G/C+ neutrophils (Fig. 6B). To determine the percentages of the various populations (macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils, or others) among the total CD14+ cells in the livers of wt infected mice, as shown in Fig. 6C, the CD11b+ population (since no CD14 expression was observed on CD11b− liver cells [Fig. 6A]) was gated for CD14 expression. The CD11b+CD14+ cells were further gated for expression of proteins F4/80 (macrophages), SiglecF (eosinophils), and Gr1 (neutrophils) (Fig. 6C, upper panel). The percentages of CD14+F4/80+, CD14+SiglecF+, and CD14+Gr1+ cells were determined by placing similar gates obtained from macrophage (CD11b+F4/80+), eosinophil (CD11b+SiglecF+), and neutrophil (CD11b+Gr1+) populations gated from the CD11b+ population (Fig. 6C, lower panel). This approach showed that approximately 90% of CD11b+CD14+ cells were F480+ compared to ∼3.5% that were SiglecF+ and 0% Gr1+. Taken together, cytometry results suggest that the majority of CD14+ cells in the livers of infected mice were macrophages. We validated this finding by overlaying macrophage, eosinophil, or neutrophil (F4/80+, siglecF+, and Gr1+) populations with CD11b+CD14+ cells (overlay histogram) to compare the expression levels of F4/80, siglecF, and Gr1 (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Consistent with the findings in Fig. 6C, we found that the CD11b+CD14+ cells were F4/80 positive, similar to the macrophage population (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material), with minimal or no expression of siglecF or Gr1 markers compared to respective populations, further emphasizing that macrophages are the major source of CD14 in the livers of infected mice (Fig. S5).

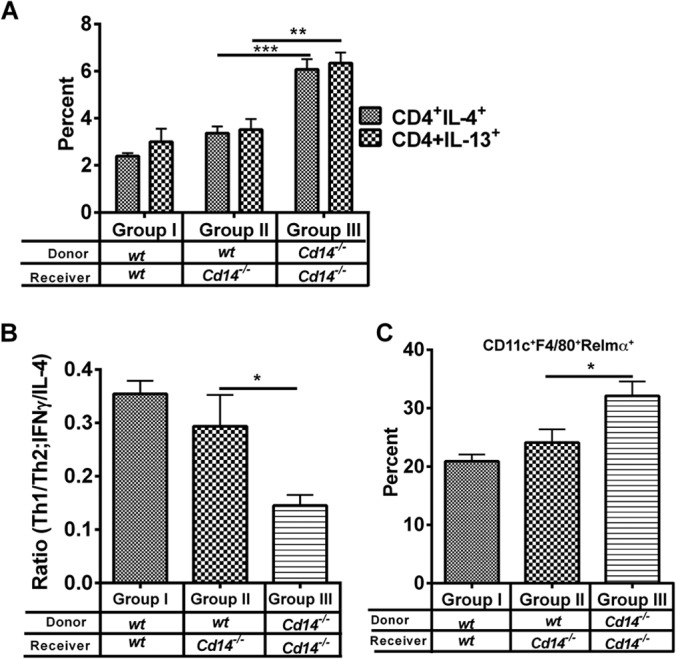

Adoptive transfer of wt macrophages normalizes alternative activation and Th2 immune responses in schistosome egg-sensitized and -challenged Cd14−/− mice.

To determine if macrophages are one of the cells responsible for CD14-mediated regulation of alternative activation and CD4+ Th responses, we performed adoptive transfer studies. We used the schistosome egg lung granuloma model, whereby naive wt or Cd14−/− mice were sensitized by intraperitoneal injection of S. mansoni eggs simultaneously with wt or Cd14−/− adherent purified peritoneal macrophages (APMs) followed by intravenous egg challenge for 1 week (25). The intravenous egg challenge included transfer of 1 × 106 wt or Cd14−/− APMs. Wild-type or Cd14−/− APMs were administered a third time (1 × 106) by intravenous injection on day 4 postchallenge. Similar to our findings with schistosome infection, transfer of Cd14−/− cells into Cd14−/− mice resulted in increased frequencies of CD4+ T cells producing IL-4 or IL-13 compared to wt mice given wt cells. As hypothesized, adoptive transfer of wt APMs into Cd14−/− mice reduced the frequencies of CD4+IL-13+ and CD4+IL-4+ T cells to levels similar to those of wt controls (Fig. 7A). Likewise, recall responses from SEA-stimulated lymph node cells from Cd14−/− and wt mice adoptively transferred with wt APMs produced comparable ratios of Th1/Th2 (IFN-γ/IL-4) cytokines, whereas Cd14−/− mice administered Cd14−/− APMs showed increased production of IL-4 and a decreased ratio of IFN-γ/IL-4 (Fig. 7B). We also examined alternative activation of lung macrophages in these mice. Unlike what occurred in livers, macrophage populations in the lungs could be clearly differentiated by the high expression of the CD11c marker (Fig. 7; see Fig. S2A and B in the supplemental material). We found that lung macrophages from Cd14−/− mice that received Cd14−/− APMs were more polarized toward alternative activation than lung macrophages from wt mice (Fig. 7C), and further, adoptive transfer of wt APMs to Cd14−/− mice reduced alternative activation of macrophages to a level similar to that seen in wt mice. Overall, these results show that transfer of wt APMs to Cd14−/− mice is by itself sufficient to overcome global CD14 deficiency and allows for constraint of CD4+ Th2 immune responses and alternative activation in response to schistosome antigens in vivo.

FIG 7.

Adoptive transfer of wild-type macrophages normalizes the Cd14−/− phenotype. The schistosome egg lung challenge model was used to determine if wt macrophages could normalize changes in alternative activation and immune responses in response to helminth antigens in Cd14−/− mice. C57BL/6 (group I) and Cd14−/− mice (groups II and III) were primed with S. mansoni eggs followed by adoptive transfer of 1 × 106 wt naive APMs to wt (group I) and Cd14−/− (group II) mice and 1 × 106 Cd14−/− APMs in Cd14−/− mice (group III) (i.p.), as indicated, on day 0. On day 14, mice were challenged with ∼5,000 S. mansoni eggs injected i.v. On days 14 and 17, mice were given 1 × 106 naive adherent peritoneal macrophages. Mice were sacrificed on day 21, and lungs and lymph nodes were isolated and single cell suspensions prepared. (A) CD4+ T cells in the mediastinal lymph nodes were assayed for cytokine (IL-4) production by flow cytometry. (B) For recall response, lymph node cells were incubated with soluble egg antigen (SEA) (25 μg/ml) for 72 h at 37°C. Cell supernatants were harvested, and production levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ were measured by ELISA. Shifts in Th1 and Th2 responses were determined by calculating the ratio of IFN-γ to IL-4 (IFN-γ/IL-4 in ng/ml) produced by splenocytes of each mouse in the group in response to SEA. (C) Lung tissues were digested in medium containing 1 mg/ml collagenase. Single-cell suspensions were surface stained using fluorescein-conjugated antibodies against macrophage markers CD11c, F4/80, and SiglecF followed by intracellular staining for M2 marker RELMα (primary antibody) and fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody. The percentages of RELMα-expressing cells among total macrophages (CD11c+F4/80+) were determined. Recipient mice and donor macrophages are as indicated for panel A. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA Tukey's multiple-comparison test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Results represent at least two independent experiments.

CD14 deficiency enhances activation of STAT6 in liver granulomas.

We observed that CD14 deficiency was associated with increased expression of the IL-4-dependent M2 markers Ym1 and RELMα. Therefore, we examined activation of STAT6 in the livers of S. mansoni-infected Cd14−/− and wt mice. Performing immunohistochemistry using an anti-(phospho)STAT6 antibody, we found that granuloma cells in the livers of infected Cd14−/− mice displayed increased STAT6 activation compared to wt controls (Fig. 8).

FIG 8.

Granulomas of infected Cd14−/− mice show increased STAT6 activation. Liver sections from S. mansoni-infected C57BL/6 (n = 5) and Cd14−/− (n = 5) mice were analyzed for activated STAT6 by immunohistochemistry using anti-pSTAT6 antibody. Liver sections were examined at magnifications of ×10 and ×40, showing granulomas (yellow arrows) stained for activated STAT6 protein in macrophages and granulocytes (red arrows) surrounding S. mansoni eggs. Results represent at least two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Alternatively activated macrophages (M2) are associated with repair of tissues and wound healing and are essential for host survival when infected with helminth parasites. During helminth infection, the degree of immune-mediated pathology and tissue destruction is largely modulated by CD4+ T cells and alternatively activated macrophages (23, 26). To date, the roles that innate immune receptors play in regulating these two populations of cells have not been studied in detail. To identify potential regulators of Th2-type responses and alternative activation, we measured the expression of innate response molecules on macrophages during schistosome infection or following injection with schistosome eggs. These experiments demonstrated that CD14 expression was highly upregulated in schistosome-infected, Th2-biased mice. Therefore, we asked if CD14 might play a role in regulating CD4+ Th2-type responses and/or alternative activation and coincident pathogenesis during helminth infection. To test this, we examined macrophage maturation and CD4+ T cell responses in schistosome-infected or egg-injected Cd14−/− mice. In both infected and egg-injected Cd14−/− mice, we observed a marked upregulation in the expression of alternative activation markers as well as upregulated Th2-type responses, including IgE production, compared to the expression in wt mice. In addition, we observed a modest increase in the numbers of regulatory T cells, reduced granuloma size associated with increased collagen deposition, and changes in cellular infiltration in Cd14−/− mice compared to wt controls. Interestingly, increased M2 activation and Th2 responses in CD14-deficient mice were associated with reduced egg burdens in the livers of infected mice compared to wt controls, suggesting that immune effector cells and/or mediators regulated via CD14 may play roles in parasite fecundity.

Besides regulation of TLR4, CD14 appears to control the functions of multiple TLRs (TLR2, -3, -7, and -9) (13, 14, 27, 28). Both MyD88 and TRIF signaling pathways are downstream of TLRs and CD14. During S. mansoni infection of TLR2- or TLR3-deficient mice, no difference in pathology or infection was observed compared to wt mice, although both TLRs were required to activate DCs with helminth antigens in vitro (29). In this regard, Layland et al. demonstrated that TLR2 inhibited Th1 responses and promoted regulatory T cells in murine S. mansoni infection (30) and additionally demonstrated that schistosome-infected Myd88−/− mice had smaller and more-fibrotic granulomas than infected wt mice, along with enhanced expression of schistosome egg-specific IL-13, coincident with reduced IFN-γ production (31). Our results with schistosome-infected Cd14−/− mice are similar to those reported by Layland et al., other than they did not evaluate the roles of TLR2 or MyD88 in driving alternative activation of macrophages (30, 31).

The impact of CD14 on IgE was an important question to investigate, as elevated levels of IgE are a hallmark of helminth infection and allergic diseases. We found that schistosome-infected Cd14−/− mice having elevated levels of IgE is similar to the levels of soluble CD14 (sCD14) in the sera of individuals carrying polymorphisms in the Cd14 gene being inversely correlated with IgE levels, as reported previously (19, 32–34). It is worthwhile to note that Cd14 is located in the same cluster on chromosome location 5q31 as the Th2 cytokine IL-4, IL-13, IL-5, and IL-9 genes, suggesting that polymorphisms in the Cd14 gene may be involved in regulation of Th2-type responses (35–39). Further, polymorphisms in the Cd14 gene may be involved in the regulation of host egg granuloma pathogenesis in humans, as polymorphisms in the 5q31 to -33 region have been shown to be related to the susceptibility of humans to schistosomiasis (40). In terms of pathogenesis in a population, polymorphisms in CD14 may be one host genetic factor determining the levels of pathogenesis in schistosomiasis. Clearly, additional studies examining the role of CD14 in the regulation of immune responses need to be performed before such a hypothesis can be confirmed.

Why negatively regulate Th2 responses and alternative activation? We hypothesize that one potential role of CD14-mediated negative regulation is to limit Th2-type responses and the coincident recruitment/expansion of AA macrophages resulting in reduced fibrosis. Our results are consistent with this hypothesis. In vitro studies show that antigens derived from egg and adult stages of S. mansoni can stimulate APCs to drive proinflammatory as well as anti-inflammatory responses via TLRs and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) (9). Glycolipids from schistosomes can also activate dendritic cells via TLR4 and DC-SIGN to produce proinflammatory cytokines (8). This suggests that TLRs may be involved in recognition of helminth antigens to modulate macrophage activation in vivo. Not only glycolipids but also live S. mansoni eggs or dsRNA isolated from these eggs can induce proinflammatory responses via TLR3 in APCs similar to that of poly(I·C). Lee et al. and others have shown that CD14 recognizes nucleic acids to regulate TLR3 (dsRNA) as well as TLR7 and -9 functions (13, 14), suggesting that CD14 may help in recognition of glycolipids as well as dsRNAs in controlling macrophage M1 activation and immune responses during schistosome infection. This may be true, as we observed significant decreases in the expression of M1 marker Nos2 in the livers of Cd14−/− mice compared to wt controls (Fig. 2). The decreased M1 activation was associated with increased M2 (Ym1 and Relmα) markers (Fig. 2), indicating that CD14 may regulate M1 and M2 phenotypes in livers of S. mansoni-infected mice. Alternatively activated (M2) macrophages are critical regulators of immune responses during schistosome infection, with tissue-trapped eggs becoming surrounded by macrophages, eosinophils, and neutrophils to form granulomas (26). H&E staining along with antibodies against Ym1 or RELMα showed that these alternative activation markers were highly upregulated in granulomas of Cd14−/− mice compared to wt controls. Our observation that among hepatic egg granulocytes macrophages are the major source of CD14 expression and our finding that adoptive transfer of wt macrophages into Cd14−/− mice was sufficient to normalize alternative activation and CD4+ Th2 responses (Fig. 7) suggest that CD14 expression by macrophage is a key regulator of macrophage M1/M2 plasticity. This is supported by earlier observations that alternatively activated macrophages regulate helminth-induced Th2 immune responses in vivo (41, 42). Eosinophil populations in the livers of infected Cd14−/− mice also showed enhanced alternative activation yet did not show expression of CD14 (Fig. 6), suggesting that increased Th2 responses (IL-4/IL-13) and/or alternatively activated macrophages in the livers of infected Cd14−/− mice account for the increased alternative activation of eosinophils. Similarly, Voehringer et al. demonstrated that alternatively activated macrophages are directly responsible for the recruitment of eosinophils during helminth infection in mice (17). Additional studies need to be performed to examine how eosinophil recruitment/activation is influenced by macrophage phenotype and host immune responses during helminth infection.

Our finding that adoptive transfer of wt macrophages into Cd14−/− egg-sensitized and -challenged mice was sufficient to normalize macrophage and CD4+ Th phenotypes provided the rationale for examining regulatory signaling pathways in macrophages where CD14 may be regulatory. Our in vivo observation that STAT6 activation in the livers of infected Cd14−/− mice was increased suggests that CD14 regulates IL-4Rα-STAT6-dependent alternative activation of macrophages (Fig. 8). This is supported by our observation that Cd14−/− APMs or bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), when stimulated with equal concentrations of M2 polarizing agent IL-4 with or without TLR2, -3, or -4 ligand in vitro, displayed significantly increased M2 polarization compared to wt macrophages (S. Tundup, L. Srivastava, and D. Harn, unpublished data), suggesting that there exists a regulatory network between CD14- and IL-4Rα-mediated pathways. Overall, these studies suggest that CD14 influences the Th1-Th2 balance, possibly by regulating macrophage M1/M2 phenotype during schistosome infection.

In summary, the data presented in this paper identify a unique regulatory role of CD14 in macrophage activation, pathology, and immune responses in vivo during helminth infection. Given that activation and recruitment of macrophages are dominant features of many inflammatory diseases, such as cancer and autoimmune, cardiovascular, metabolic, and allergic diseases, CD14 may serve as a potential, broadly immunotherapeutic target for numerous proinflammatory diseases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Cac Than Bui and Farah Samli for their technical assistance. We are also grateful to Wendy Watford for help in proofreading the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant 5R01AI056484 to D.H.), University of Georgia Research Funds, and the Georgia Research Alliance.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 May 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.01780-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pearce EJ, MK C, Sun J, JT J, McKee AS, Cervi L. 2004. Th2 response polarization during infection with the helminth parasite Schistosoma mansoni. Immunol. Rev. 201:117–126. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hesse M, Cheever AW, Jankovic D, Wynn TA. 2000. NOS-2 mediates the protective anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects of the Th1-inducing adjuvant, IL-12, in a Th2 model of granulomatous disease. Am. J. Pathol. 157:945–955. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64607-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu T, Dhanasekaran SM, Jin H, Hu B, Tomlins SA, Chinnaiyan AM, Phan SH. 2004. FIZZ1 stimulation of myofibroblast differentiation. Am. J. Pathol. 164:1315–1326. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63218-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz Y, Svistelnik AV. 2012. Functional phenotypes of macrophages and the M1–M2 polarization concept. Part I. Proinflammatory phenotype. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 77:246–260. 10.1134/S0006297912030030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. 2009. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27:451–483. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon S. 2003. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:23–35. 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aksoy E, Zouain CS, Vanhoutte F, Fontaine J, Pavelka N, Thieblemont N, Willems F, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Goldman M, Capron M, Ryffel B, Trottein F. 2005. Double-stranded RNAs from the helminth parasite Schistosoma activate TLR3 in dendritic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280:277–283. 10.1074/jbc.M411223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Stijn CM, Meyer S, van den Broek M, Bruijns SC, van Kooyk Y, Geyer R, van Die I. 2010. Schistosoma mansoni worm glycolipids induce an inflammatory phenotype in human dendritic cells by cooperation of TLR4 and DC-SIGN. Mol. Immunol. 47:1544–1552. 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tundup S, Srivastava L, Harn DA., Jr 2012. Polarization of host immune responses by helminth-expressed glycans. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1253:E1–E13. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang Z, Georgel P, Du X, Shamel L, Sovath S, Mudd S, Huber M, Kalis C, Keck S, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Beutler B. 2005. CD14 is required for MyD88-independent LPS signaling. Nat. Immunol. 6:565–570. 10.1038/ni1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zanoni I, Ostuni R, Marek LR, Barresi S, Barbalat R, Barton GM, Granucci F, Kagan JC. 2011. CD14 controls the LPS-induced endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4. Cell 147:868–880. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zanoni I, Ostuni R, Capuano G, Collini M, Caccia M, Ronchi AE, Rocchetti M, Mingozzi F, Foti M, Chirico G, Costa B, Zaza A, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Granucci F. 2009. CD14 regulates the dendritic cell life cycle after LPS exposure through NFAT activation. Nature 460:264–268. 10.1038/nature08118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumann CL, Aspalter IM, Sharif O, Pichlmair A, Bluml S, Grebien F, Bruckner M, Pasierbek P, Aumayr K, Planyavsky M, Bennett KL, Colinge J, Knapp S, Superti-Furga G. 2010. CD14 is a coreceptor of Toll-like receptors 7 and 9. J. Exp. Med. 207:2689–2701. 10.1084/jem.20101111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HK, Dunzendorfer S, Soldau K, Tobias PS. 2006. Double-stranded RNA-mediated TLR3 activation is enhanced by CD14. Immunity 24:153–163. 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucker MS, Karunaratne LB, Lewis FA, Freitas TC, Liang YS. 2013. Schistosomiasis. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 103:Unit 19.1. 10.1002/0471142735.im1901s103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goh YP, Henderson NC, Heredia JE, Red Eagle A, Odegaard JI, Lehwald N, Nguyen KD, Sheppard D, Mukundan L, Locksley RM, Chawla A. 2013. Eosinophils secrete IL-4 to facilitate liver regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:9914–9919. 10.1073/pnas.1304046110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voehringer D, van Rooijen N, Locksley RM. 2007. Eosinophils develop in distinct stages and are recruited to peripheral sites by alternatively activated macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 81:1434–1444. 10.1189/jlb.1106686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vercelli D, Baldini M, Martinez F. 2001. The monocyte/IgE connection: may polymorphisms in the CD14 gene teach us about IgE regulation? Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 124:20–24. 10.1159/000053658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vercelli D, Baldini M, Stern D, Lohman IC, Halonen M, Martinez F. 2001. CD14: a bridge between innate immunity and adaptive IgE responses. J. Endotoxin Res. 7:45–48. 10.1179/096805101101532521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramalingam TR, Reiman RM, Wynn TA. 2005. Exploiting worm and allergy models to understand Th2 cytokine biology. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 5:392–398. 10.1097/01.all.0000182542.30100.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mentink-Kane MM, Cheever AW, Thompson RW, Hari DM, Kabatereine NB, Vennervald BJ, Ouma JH, Mwatha JK, Jones FM, Donaldson DD, Grusby MJ, Dunne DW, Wynn TA. 2004. IL-13 receptor alpha 2 down-modulates granulomatous inflammation and prolongs host survival in schistosomiasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:586–590. 10.1073/pnas.0305064101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Estaquier J, Marguerite M, Sahuc F, Bessis N, Auriault C, Ameisen JC. 1997. Interleukin-10-mediated T cell apoptosis during the T helper type 2 cytokine response in murine Schistosoma mansoni parasite infection. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 8:153–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson MS, Mentink-Kane MM, Pesce JT, Ramalingam TR, Thompson R, Wynn TA. 2007. Immunopathology of schistosomiasis. Immunol. Cell Biol. 85:148–154. 10.1038/sj.icb.7100014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearce EJ, MacDonald AS. 2002. The immunobiology of schistosomiasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:499–511. 10.1038/nri843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joyce KL, Morgan W, Greenberg R, Nair MG. 2012. Using eggs from Schistosoma mansoni as an in vivo model of helminth-induced lung inflammation. J. Vis. Exp. 2012(69):e3905. 10.3791/3905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herbert DR, Holscher C, Mohrs M, Arendse B, Schwegmann A, Radwanska M, Leeto M, Kirsch R, Hall P, Mossmann H, Claussen B, Forster I, Brombacher F. 2004. Alternative macrophage activation is essential for survival during schistosomiasis and downmodulates T helper 1 responses and immunopathology. Immunity 20:623–635. 10.1016/S1074-7613(04)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowdish DM, Sakamoto K, Kim MJ, Kroos M, Mukhopadhyay S, Leifer CA, Tryggvason K, Gordon S, Russell DG. 2009. MARCO, TLR2, and CD14 are required for macrophage cytokine responses to mycobacterial trehalose dimycolate and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000474. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manukyan M, Triantafilou K, Triantafilou M, Mackie A, Nilsen N, Espevik T, Wiesmuller KH, Ulmer AJ, Heine H. 2005. Binding of lipopeptide to CD14 induces physical proximity of CD14, TLR2 and TLR1. Eur. J. Immunol. 35:911–921. 10.1002/eji.200425336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanhoutte F, Breuilh L, Fontaine J, Zouain CS, Mallevaey T, Vasseur V, Capron M, Goriely S, Faveeuw C, Ryffel B, Trottein F. 2007. Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR3 sensing is required for dendritic cell activation, but dispensable to control Schistosoma mansoni infection and pathology. Microbes Infect. 9:1606–1613. 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Layland LE, Rad R, Wagner H, da Costa CU. 2007. Immunopathology in schistosomiasis is controlled by antigen-specific regulatory T cells primed in the presence of TLR2. Eur. J. Immunol. 37:2174–2184. 10.1002/eji.200737063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Layland LE, Wagner H, da Costa CU. 2005. Lack of antigen-specific Th1 response alters granuloma formation and composition in Schistosoma mansoni-infected MyD88-/- mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 35:3248–3257. 10.1002/eji.200526273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sackesen C, Birben E, Soyer OU, Sahiner UM, Yavuz TS, Civelek E, Karabulut E, Akdis M, Akdis CA, Kalayci O. 2011. The effect of CD14 C159T polymorphism on in vitro IgE synthesis and cytokine production by PBMC from children with asthma. Allergy 66:48–57. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dreskin SC, Ayars A, Jin Y, Atkins D, Leo HL, Song B. 2011. Association of genetic variants of CD14 with peanut allergy and elevated IgE levels in peanut allergic individuals. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 106:170–172. 10.1016/j.anai.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han D, She W, Zhang L. 2010. Association of the CD14 gene polymorphism C-159T with allergic rhinitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 24(1):e1–3. 10.2500/ajra.2010.24.3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ober C, Moffatt MF. 2000. Contributing factors to the pathobiology. The genetics of asthma. Clin. Chest Med. 21:245–261. 10.1016/S0272-5231(05)70264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koppelman GH, Reijmerink NE, Colin Stine O, Howard TD, Whittaker PA, Meyers DA, Postma DS, Bleecker ER. 2001. Association of a promoter polymorphism of the CD14 gene and atopy. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 163:965–969. 10.1164/ajrccm.163.4.2004164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baldini M, Lohman IC, Halonen M, Erickson RP, Holt PG, Martinez FD. 1999. A Polymorphism* in the 5′ flanking region of the CD14 gene is associated with circulating soluble CD14 levels and with total serum immunoglobulin E. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 20:976–983. 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.5.3494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wills-Karp M, Ewart SL. 2004. Time to draw breath: asthma-susceptibility genes are identified. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5:376–387. 10.1038/nrg1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marsh DG, Neely JD, Breazeale DR, Ghosh B, Freidhoff LR, Ehrlich-Kautzky E, Schou C, Krishnaswamy G, Beaty TH. 1994. Linkage analysis of IL4 and other chromosome 5q31.1 markers and total serum immunoglobulin E concentrations. Science 264:1152–1156. 10.1126/science.8178175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quinnell RJ. 2003. Genetics of susceptibility to human helminth infection. Int. J. Parasitol. 33:1219–1231. 10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pesce JT, Ramalingam TR, Wilson MS, Mentink-Kane MM, Thompson RW, Cheever AW, Urban JF, Jr, Wynn TA. 2009. Retnla (relmalpha/fizz1) suppresses helminth-induced Th2-type immunity. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000393. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nair MG, Du Y, Perrigoue JG, Zaph C, Taylor JJ, Goldschmidt M, Swain GP, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy A, Karow M, Stevens S, Pearce EJ, Artis D. 2009. Alternatively activated macrophage-derived RELM-{alpha} is a negative regulator of type 2 inflammation in the lung. J. Exp. Med. 206:937–952. 10.1084/jem.20082048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.