Abstract

Francisella tularensis induces the synthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) by infected macrophages to alter host immune responses, thus providing a survival advantage to the bacterium. We previously demonstrated that PGE2 synthesis by F. tularensis-infected macrophages requires cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 (mPGES1). During inducible PGE2 synthesis, cPLA2 hydrolyzes arachidonic acid (AA) from cellular phospholipids to be converted to PGE2. However, in F. tularensis-infected macrophages we observed a temporal disconnect between Ser505-cPLA2 phosphorylation (a marker of activation) and PGE2 synthesis. These results suggested to us that cPLA2 is not responsible for the liberation of AA to be converted into PGE2 by F. tularensis-infected macrophages. Utilizing small-molecule inhibitors, we demonstrated that phospholipase D and diacylglycerol lipase were required for providing AA for PGE2 biosynthesis. cPLA2, on the other hand, was required for macrophage cytokine responses to F. tularensis. We also demonstrated for the first time that lipin-1 and PAP2a contribute to macrophage inflammation in response to F. tularensis. Our results identify both an alternative pathway for inducible PGE2 synthesis and a role for lipid-modifying enzymes in the regulation of macrophage inflammatory function.

INTRODUCTION

Francisella tularensis is a Gram-negative facultative intracellular bacterium and the causative agent of tularemia, a disease capable of causing a high level of mortality in humans. The most severe form of the disease is pneumonic tularemia. Inhalation of as few as 10 organisms can cause disease which has a >30% case fatality rate if untreated (1, 2). The low infectious dose and high morbidity and mortality of F. tularensis infections led to the weaponization of the organism (3, 4). There is no FDA-approved vaccine available to prevent tularemia. Thus, the CDC has classified F. tularensis as a category A select agent.

F. tularensis invasion and growth within macrophages are critical for disease manifestation (5). The ability of this bacterium to alter host immune responses is also important to bacterial survival in the host and disease pathogenesis. The significance of altering host immune responses is highlighted by the observation that F. tularensis strains with mutations in clpB grow within host macrophages in vitro but fail to alter host immune responses in vivo and are easily eradicated by the host (6). Numerous F. tularensis-mediated immune evasion mechanisms have been identified (reviewed in reference 7). One important mechanism of Francisella (Francisella novicida, F. tularensis live vaccine strain [LVS], and F. tularensis Schu S4) immune evasion that we have identified is the ability of F. tularensis to induce the biosynthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) by infected macrophages (8, 9). The immunological function of PGE2 is context dependent and can exhibit pro- or anti-inflammatory properties. However, during infectious disease, the activity of PGE2 is mostly anti-inflammatory, whereby it suppresses the production of inflammatory cytokines (10, 11). In vitro, F. tularensis induction of PGE2 synthesis by infected macrophages inhibits T cell proliferation and Th1 phenotypic development, reducing the T cells' ability to produce proinflammatory cytokines such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (12). IFN-γ synthesis by T cells is critical for clearance of F. tularensis from the host (13, 14). PGE2 also reduces macrophage surface expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II by ubiquitination-mediated degradation (15). Increased levels of PGE2 are detected in the lungs of mice with respiratory tularemia (8). The inhibition of PG synthesis during respiratory tularemia results in a decreased bacterial burden and an increased number of Francisella specific IFN-γ+ T cells (12). Thus, the ability of F. tularensis to induce activation of the PG synthetic pathway modulates host immune responses and provides a survival advantage for the bacteria.

PGE2 is a lipid signaling molecule derived from arachidonic acid (AA). AA is a short-lived metabolite in host cells as it is immediately converted into a bioactive eicosanoid or reincorporated into phospholipids. Activation of the canonical inducible PGE2 synthetic pathway by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or zymosan typically requires the liberation of AA by group IVA phospholipase A2 (cPLA2α) (16). This liberated AA is oxidized by cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) to form PGH2 (17). PGH2 is isomerized to PGE2 by microsomal prostaglandin E synthase (mPGES1). We previously demonstrated that F. tularensis-induced PGE2 synthesis by macrophages requires cPLA2, COX-2, and mPGES1 (8, 18), yet we observed a temporal disconnect between cPLA2 activation and the time at which increases in COX-2 protein and PGE2 synthesis are observed. AA release and utilization by COX-2 are highly coupled events, and this apparent disconnect between cPLA2 activation and the increase in COX-2 protein led us to hypothesize that an alternative pathway utilizing other phospholipases was required for supplying AA to the inducible PGE2 biosynthetic pathway in F. tularensis-infected macrophages.

The canonical PGE2 biosynthetic pathway involves cPLA2 liberation of AA directly from phospholipid membranes. However, AA can be obtained via alternative lipid metabolism pathways using diacylglycerol (DAG). Phospholipase D (PLD) and phosphatidate phosphohydrolase (PAP) or phospholipase C (PLC) can liberate DAG from host phospholipid membranes. DAG can then be converted to AA by the diacylglycerol (DAGL) and monoacylglycerol (MAGL) lipases (19) (Fig. 1). In neuronal cells, upon receptor stimulation, either PLC or PLD can help supply AA-containing lipids to the PG synthetic pathway (20). The studies presented in this work demonstrate that PLD and DAGL likely supply AA that is converted into PGE2 in Francisella tularensis LVS-infected macrophages and that cPLA2 contributes to the macrophage inflammatory response. Finally, we identify a role for the PAPs lipin-1 and PAP2a in regulating the inducible PGE2 biosynthetic pathway in F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages. This work identifies a novel alternative pathway for the liberation of AA during pathogen-induced PGE2 biosynthesis by macrophages and shows that cPLA2 and PAPs contribute to macrophage inflammatory responses to F. tularensis.

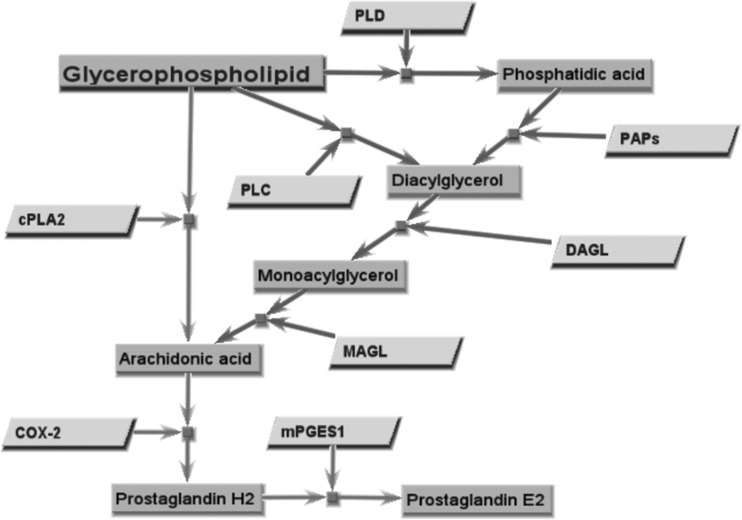

FIG 1.

Glycerophospholipid metabolism and prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis. In the canonical PGE2 biosynthetic pathway (light gray arrows), arachidonic acid is liberated directly from phospholipid membranes by cytosolic phospholipase A2. Arachidonic acid can also be obtained via alternate lipid metabolism pathways (dark gray arrows) involving diacylglycerol. Lipid intermediates (dark gray rectangles) and the enzymes (light gray parallelograms) that catalyze each reaction are shown. Enzymes: cPLA2, cytosolic phospholipase A2; PLC, phospholipase C; PLD, phospholipase D; PAPs, phosphatidate phosphohydrolases; DAGL, diacylglycerol lipase; MAGL, monoacylglycerol lipase; COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2; mPGES1, microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inhibitors.

The inhibitors used in these studies were pyrrophenone (for cPLA2), CAY10590 (for sPLA2), Edelfosine (for phosphatidylinositol [PI]-PLC), JZL184 (for MAGL), and indomethacin (for COX-2) (all purchased from Cayman Chemical); propranolol (for PAP), RHC80267 (for DAGL), MJ33 (for iPLA2), U73122 (for PLC), and cytochalasin D (CD) (for actin polymerization) (all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich); VU0155056 (for PLD1/2) (purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.); and D609 (for phosphatidylcholine [PC]-PLC) (purchased from Tocris Bioscience). The vehicle for all inhibitors is dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) with the exceptions of propranolol (H2O, pH 3), and D609 (H2O).

Cell lines.

The murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 (ATCC TIB-71) was cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2, in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlas), 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (HyClone), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (ATCC), and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Fisher Scientific). RAW 264.7 cells were placed in supplemented antibiotic-free DMEM 24 hours prior to inoculation.

The murine fibroblast cell line L929 (ATCC CCL-1) was grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol and used to generate L-cell conditioned medium. Briefly, 2.5 × 105 cells were added to a T150 tissue culture flask with 75 ml medium. The flask was incubated for ∼10 to 12 days at 37°C. Medium was collected, cleared of cell debris by centrifugation, filtered, and stored at −80°C until use.

Bacteria.

The Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain (LVS) (29684; American Type Culture Collection) was used in these studies. Bacteria were grown on chocolate agar at 37°C. Bacteria from lawn growth were isolated with a cotton swab and diluted into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a concentration of 5 × 109 CFU per ml. Bacteria were then diluted into PBS and used for inoculation of macrophages.

For experiments that tested the effect of inhibitors on bacterial growth in broth, F. tularensis LVS from chocolate agar was inoculated into brain heart infusion (BHI)-LB agar supplemented with IsoVitaleX and grown overnight at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. One hundred sixty microliters of broth and 40 μl of overnight LVS culture were added to each well. Wells were then left untreated or treated with vehicle or inhibitor. The absorbance of each well was measured at 600 nm every 5 min over the course of 12 h at 37°C with 120 s of plate shaking before each measurement.

Mice.

Six-week-old, female C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All animals used in this study were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions in the AALAC Louisiana State University Health Science Center (LSUHSC) animal medicine facilities. All work was approved by the LSUHSC Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC).

BMDM generation.

Murine, bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were generated by flushing the bone marrow from the femurs of female 6- to 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice and incubating these cells for 7 days in complete DMEM with L929 fibroblast conditioned medium at 37°C and 5% CO2. Twenty-four hours prior to inoculation, plates containing BMDMs were switched to antibiotic-free RMPI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. On the day of inoculation, medium was removed and cells were washed twice with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; HyClone) to remove nonadherent cells. Cells were removed from the plate by incubation with 10 mM EDTA, pH 7.6, in PBS (8).

Infection of cells and treatment with inhibitors.

RAW 264.7 cells or BMDMs were plated in a 96-well plate at a concentration of 1.5 × 105/well and allowed to adhere for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were inoculated at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 200:1. Two hours postinoculation, extracellular bacteria were removed and killed by the addition of fresh medium containing 50 μM gentamicin for 1 h. Cells were then washed twice with fresh medium, and fresh, antibiotic-free complete medium was added. Plates were then incubated at 37°C for a further 20 h. Cells were pretreated 1 h prior to infection with inhibitor or vehicle (DMSO or H2O) where indicated. Inhibitors were readded after each wash. Supernatants were collected 24 h postinfection and exposed to UV radiation for 10 min to inactivate any viable bacteria.

Enzyme immunoassay.

PGE2 was measured using a commercially available PGE2 immunoassay kit (Assay Designs) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cytokine concentrations were determined using a Milliplex cytokine panel (Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Arachidonic acid release assay.

The arachidonic acid release assay was performed as published with modification (21, 22). Briefly, 5.0 × 105 RAW 264.7 cells or BMDMs were plated into a 24-well plate and incubated for 20 h in antibiotic-free, complete DMEM containing 1% FBS and 0.25 μCi/ml tritiated arachidonic acid ([3H]AA; Perkin-Elmer). Cells were then washed twice with serum-free, antibiotic-free complete RPMI 1640 containing 0.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Fisher Scientific). Five hundred microliters of antibiotic-free complete RPMI 1640 was added for the assay. Macrophages were pretreated with inhibitors for 1 h prior to inoculation with F. tularensis LVS or stimulation with LPS. Macrophages were then mock treated or inoculated with F. tularensis LVS. Two hours following treatment, culture medium was replaced with complete RPMI 1640 containing 50 μg/ml gentamicin. Supernatants and cell lysates were collected at indicated time points postinoculation, and AA release was detected by liquid scintillation (ScintiVerse BD cocktail; Fisher Scientific) and expressed as a ratio of radioactivity (counts per minute) in supernatant versus total radioactivity present in well (cell lysates plus supernatant).

Intracellular growth assay.

RAW 264.7 cells or BMDMs were plated and inoculated as described above. Macrophages were gently lysed in 100 μl of 0.05% SDS in PBS for 5 min to release intracellular bacteria. Bacteria were enumerated by 10-fold serial dilutions in PBS and plating onto chocolate agar plates. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 to 3 days until single colonies appeared.

Immunoblot analysis.

BMDMs or RAW 264.7 cells were lysed in NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen). Protein concentration was determined by RC/DC protein assay (Bio-Rad). Equivalent amounts of protein (20 to 40 μg total protein) between samples were loaded onto a 4 to 12% polyacrylamide NuPAGE Novex gel. MOPS (50 mM 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid, 50 mM Tris base, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.7) or MES [50 mM 2-(4-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid, 50 mM Tris base, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.3] running buffer was used to run the gel (Invitrogen). Proteins were separated at 200 V for 45 min in MES buffer or 55 min in MOPS buffer. Semidry transfer was performed on the gel for 45 min at 20 V onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (Immobilon-FL) membrane (EMD Millipore). The membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with Li-Cor blocking buffer (Li-Cor Biosciences). Primary antibodies were diluted in 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) and incubated with the blots overnight at 4°C with rocking. Secondary antibodies were diluted in 5% milk in TBST plus 0.01% SDS. The membranes were washed three times, 15 min each, with TBST while rocking after incubation with each antibody. The blot images were acquired with an Odyssey Western blot imaging system according to the manufacturer's instructions. The fluorescent secondary antibody for the Odyssey imaging system is light sensitive; therefore, all manipulations with this antibody were protected from light. Densitometry was performed using Li-Cor Odyssey analysis software (Odyssey). Bands of interest were normalized to β-actin for statistical analysis. Antibodies were as follows: COX-2 and mPGES1 (both were purchased from Cayman Chemical); cPLA2, Ser505 p-cPLA2, DAGL, and PLD (purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology); lipin-1 and PAP2a (purchased from Novus Biologicals); β-actin (purchased from Sigma); and IRDye 680LT donkey (polyclonal) anti-rabbit IgG secondary and blocking buffer (purchased from Li-Cor Biosciences). All antibodies were diluted 1:500 with the exception of β-actin and IRDye secondary antibody (1:20,000).

shRNA knockdown.

Lentiviral short hairpin RNA (shRNA) delivery particles (Sigma-Aldrich) for ppap2a and lpin1 were used to generate stable knockdown in the RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line. RAW 264.7 cells were grown to ∼30% confluence, and 5 × 104 cells were plated in a 6-well plate. Protamine sulfate (8 μg/ml) was added to increase virus binding. Ten microliters of virus was added to each well, and plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Medium was then switched to fresh DMEM and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Cells were placed under selection for 48 h by adding 5 μg/ml puromycin. Fresh selection medium was applied every 24 h until all cells in the virus control well had died. Cells were transferred to T25 flasks under selection.

Cell death.

Macrophage cell death was determined by flow cytometry using the LIVE/DEAD Fixable Yellow dead cell stain kit (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) of each group were compared.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

RNA was extracted with RNA Stat60 reagent (Tel-Test). RNA extract was treated with 1 U/μl RQ1 DNase (Promega), followed by cDNA synthesis using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit. cDNA was amplified by PCR with primers specific to each gene. Primer sequences were obtained from the Harvard Primer Bank (Lpin1 and Hprt) or designed with the NCBI primer design tool (Ppap2a). Primer sequences were as follows: murine Lpin1, 5′-CATGCTTCGGAAAGTCCTTCA-3′ and 5′-GGTTATTCTTTGGCGTCAACCT-3′; murine Ppap2a, 5′-TCAAGGCATACCCCCTTCCA-3′ and 5′-CACTCGAGAAAGGCCCACAT-3′; murine Hprt, 5′-GCTGACCTGCTGGATTACATTAA-3′ and 5′-TGATCATTACAGTAGCTCTTCAGTCTGA-3′.

Statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism 5.0 was used for analysis. Statistical significance was determined using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Dunnett posttest, P ≤ 0.05. Bar graphs display means of pooled experiments ± standard errors of the means (SEMs). All experiments were performed a minimum of three times, and the data presented are pooled from all experiments.

RESULTS

Francisella tularensis LVS induces dephosphorylation of cPLA2.

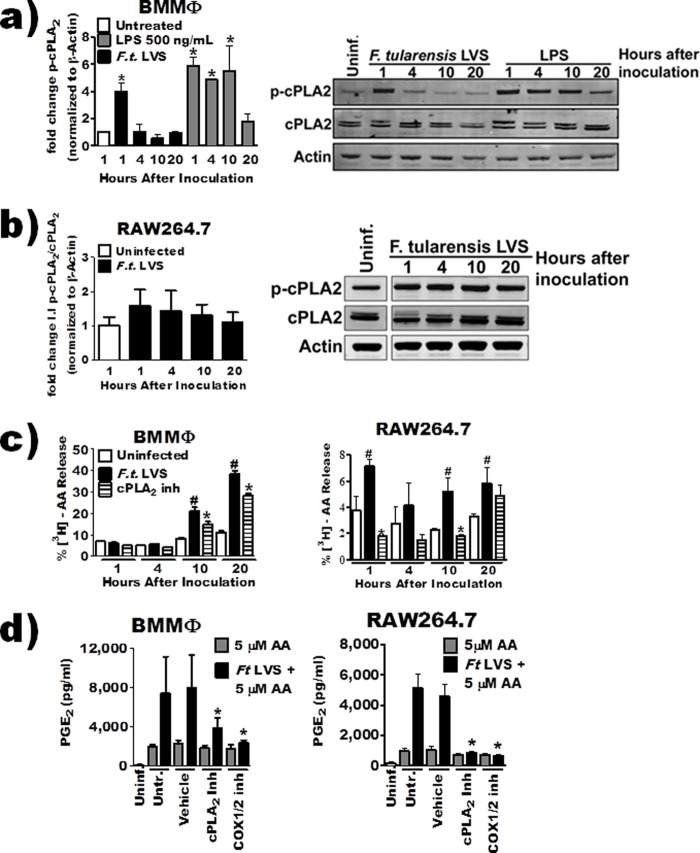

We previously demonstrated that Ser505 cPLA2 phosphorylation peaks and returns to baseline (2 hours after inoculation) before either an increase in COX-2 protein (∼4 h after inoculation) or detectable biosynthesis of PGE2 (∼10 to 12 h after inoculation) in F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages (18). Since cPLA2 phosphorylation was not measured more than 2 h after inoculation in our previous study, the possibility for a biphasic pattern of cPLA2 phosphorylation that corresponds with PGE2 biosynthesis still remains. Therefore, cPLA2 phosphorylation in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) was quantified 1, 4, 10, and 20 h after inoculation. In agreement with our previous report, cPLA2 phosphorylation peaked 1 h after inoculation with F. tularensis LVS. Furthermore, no increase in phosphorylation was detected later than 2 h after inoculation (Fig. 2a). LPS stimulation (100 ng/ml), in contrast, resulted in prolonged elevation of cPLA2 phosphorylation, up to 10 h posttreatment (Fig. 2a). Similar results were observed in the F. tularensis LVS-infected RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line (Fig. 2b).

FIG 2.

cPLA2-derived AA does not contribute to PGE2 biosynthesis. (a and b) BMDMs (a) or RAW 264.7 cells (b) were inoculated with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1 or treated with LPS (10 ng/ml). Whole-cell extracts were collected at 1, 4, 10, and 20 hours posttreatment, and total cPLA2 or Ser505-cPLA2 (p-cPLA2) was quantified by Western blotting. A representative blot is shown along with band quantification of 3 to 4 independent experiments. Integrated intensity (I.I.), i.e., band intensity, was measured for quantification. (c) BMDMs or RAW 264.7 macrophages labeled with [3H]arachidonic acid were pretreated with 5 μM pyrrophenone for 1 hour and then inoculated with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1. Radioactivity in the supernatant and cell fraction was measured at 1, 4, 10, and 20 hours posttreatment by liquid scintillation and expressed as percent release (n = 3). #, significant increase from untreated group; *, significant reduction from F. tularensis LVS-infected group (P ≤ 0.05). (d) BMDMs or RAW 264.7 macrophages were pretreated with inhibitors and then inoculated with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1. Three hours after inoculation, 5 μM arachidonic acid was added to the culture medium. PGE2 in the supernatant was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay 24 hours after inoculation (n = 4). The asterisk indicates a statistical difference versus the untreated uninfected (a) or F. tularensis LVS-plus-AA (d) group (P ≤ 0.05). For clarity, the data from some experiments were presented in multiple figures. However, these experiments were run simultaneously and as such utilize the same controls (uninfected, infected, and COX-2 inhibitor treated). This includes panels c and d and Fig. 5a and b. Graphs are means of pooled experiments ± SEMs.

It is possible for cPLA2 to be active independently of Ser505 phosphorylation and liberate AA from the phospholipid membrane (23). To determine if cPLA2 was still liberating AA that could be converted into PGE2 by F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages, we decided to monitor liberation of AA using a standard arachidonic acid release assay. In this assay, macrophages are incubated with radiolabeled arachidonic acid that becomes incorporated into host lipid membranes. After stimulation, radioactivity is measured in supernatants as a marker for AA liberation. Since AA is a precursor to numerous lipid metabolites, any signal detected in the supernatant is a collective sum of all AA-containing lipids that are released from the host cells. We incubated BMDMs with radiolabeled AA for 16 h prior to inoculation. To examine the contribution of cPLA2 enzymatic activity to F. tularensis LVS-induced AA release, we treated macrophages with a 5 μM concentration of the highly selective cPLA2 inhibitor pyrrophenone 1 h prior to inoculation. There was a significant release of AA by infected macrophages at 10 and 20 h after inoculation that was dependent upon cPLA2 activity (Fig. 2c). However, the inhibition of AA release by cPLA2 observed at these time points was only partial, suggesting that other enzymes may be contributing to AA-containing lipids secreted by F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages. The results obtained with the RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line differed in that in addition to the later release of AA (10 and 20 h after inoculations), we also observed a significant increase in AA release at 1 h after inoculation (Fig. 2c). This difference between BMDMs and RAW 264.7 macrophages could be a result of higher baseline levels of p-cPLA2 in RAW 264.7 cells (Fig. 2b). Taken together, these data suggest to us that production of AA-derived lipid metabolites is partially dependent upon cPLA2 activity. To more precisely address the contribution of cPLA2-dependent liberation of AA that is used specifically for PGE2 biosynthesis, we decided to use an “AA-addback” approach. We hypothesized that the addition of AA to culture supernatants following cPLA2 inhibition would restore PGE2 biosynthesis by F. tularensis-infected macrophages. BMDMs or RAW 264.7 macrophages were pretreated with inhibitors and then inoculated with F. tularensis LVS. Three hours after inoculation, 5 μM AA was added to the culture medium of macrophages. The anti-PGE2 antibody used in the PGE2 ELISA can cross-react with AA (0.1% as reported by Enzo product literature). Thus, to ensure that we were not just detecting AA in our AA-addback groups, we included an indomethacin-treated control. Indomethacin inhibits COX-1/2, blocking PGE2 production. Exogenous AA restored LPS-induced PGE2 synthesis when cPLA2 was inhibited (data not shown) but was unable to restore PGE2 biosynthesis when cPLA2 or COX-1/2 was inhibited (Fig. 2d). Though these results do not definitively suggest that cPLA2 does not supply AA to be converted into PGE2, they do support our view that at the very least enzymes in addition to cPLA2 are likely required for providing AA that is converted into PGE2 in F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages.

Multiple lipases are required for PGE2 biosynthesis in response to F. tularensis LVS.

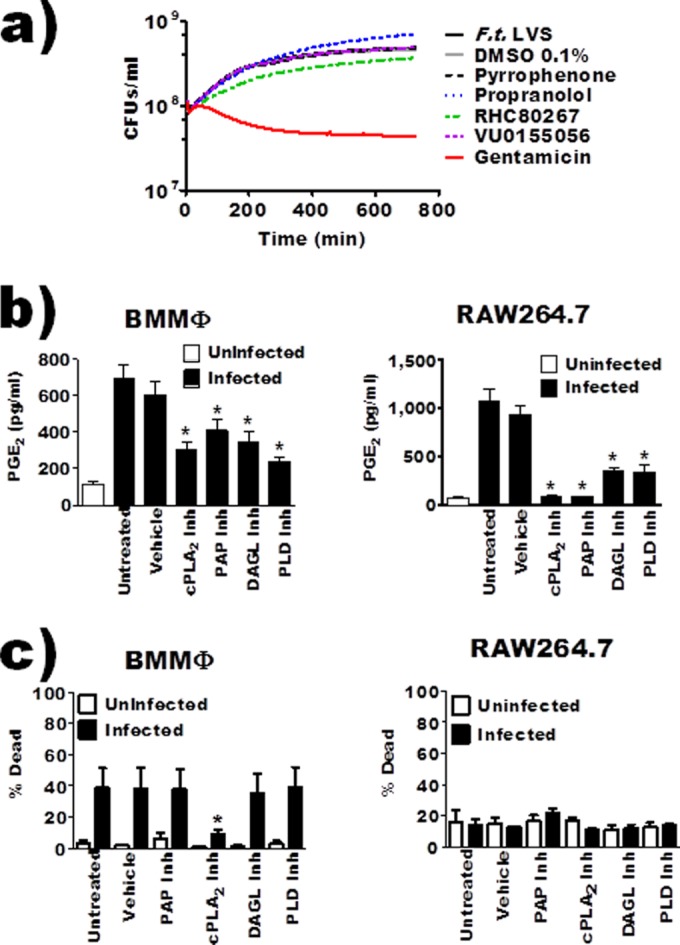

To determine if other lipid-modifying enzymes could be contributing to F. tularensis-induced PGE2 biosynthesis, we utilized a variety of small-molecule inhibitors to specifically inhibit the activities of the enzymes listed in Table 1. We have previously observed that some small-molecule inhibitors designed to inhibit eukaryotic enzymes can interfere with growth of F. tularensis LVS in broth. To determine if the inhibitors used in this study affected bacterial viability, we performed a 12-hour broth growth assay in the presence of selected inhibitors. We quantified bacterial growth as a function of broth turbidity by monitoring absorbance at 600 nm (Fig. 3a). The calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (bromoenol lactone) and phospholipase C (D609) inhibitors inhibited bacterial growth in broth and were eliminated from the study. To determine if the listed enzymes were involved in F. tularensis LVS-induced PGE2 biosynthesis, we treated BMDMs or RAW 264.7 macrophages 1 h prior to inoculation. Twenty-four hours after inoculation, the concentration of PGE2 in supernatants was determined. This preliminary screen identified the requirement of PLD, DAGL, and PAP activity for F. tularensis LVS-induced PGE2 synthesis by infected macrophages (data not shown). After the initial screen, we identified inhibitor concentrations for the PLD1/2 inhibitor VU0155056 (10 μM) and the DAGLα/β inhibitor RHC80267 (25 μM) that retained specificity for the intended target (no reported off-target effects) and significantly reduced PGE2 biosynthesis by infected macrophages (21, 24, 25). There are no specific inhibitors for the different phosphatidic acid phosphatase (PAP) enzymes found in macrophages; as such, we used the pan-PAP inhibitor propranolol (22, 26). Due to the nonspecific nature of propranolol, we used shRNA to confirm the results obtained with this inhibitor. The PAP shRNA results are presented below. The inhibition of cPLA2, PAP, DAGL, or PLD activity 1 h prior to inoculation of BMDMs or RAW 264.7 macrophages with F. tularensis LVS resulted in significantly less detectable PGE2 in the supernatants (Fig. 3b). Vehicle alone did not induce the synthesis of PGE2 from macrophages (data not shown). To ensure that decreased PGE2 synthesis was not due to increased macrophage cell death induced by the inhibitor, we determined the percentage of dead cells when inhibitors were added to uninfected or infected cells. Inhibitor treatment alone did not induce cell death of either BMDMs or RAW 264.7 macrophages (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, infection of inhibitor-treated BMDMs or RAW 264.7 macrophages did not result in increased cell death compared to untreated, infected macrophages. Thus, it seems unlikely that the changes in PGE2 biosynthesis observed with inhibitor-treated macrophages were due to inhibitor-induced cell death of macrophages. In fact, propranolol treatment resulted in decreased BMDM cell death compared to untreated infected BMDMs and decreased PGE2 synthesis. Finally, we do not see increased cell death in infected or infected and treated macrophages until 12 h after inoculation, which is after we begin to see the increase in COX-2 and PGE2 levels (data not shown). These data suggest that the enzymes PAP, DAGL, and PLD contribute to PGE2 biosynthesis by F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages.

TABLE 1.

Inhibitors used in this studya

| Inhibitor | Target | Concn (μM) | LVS growthb |

|---|---|---|---|

| MJ33 | iPLA2 | 10 | ↔ |

| Pyrrophenone | cPLA2 | 5 | ↔ |

| CAY10590 | sPLA2 | 20 | ↔ |

| D609 | PC-PLC | 30 | ↓ |

| Edelfosine | PI-PLC | 30 | ↔ |

| Propranolol | PAP | 100 | ↑ |

| RHC80267 | DAGL | 25 | ↔ |

| JZL184 | MAGL | 0.3 | ↔ |

| VU0155056 | PLD1/2 | 10 | ↔ |

| Bromoenol lactone | iPLA2 | 1 | ↓ |

| U73122 | PLC | 5 | ↔ |

The inhibitors used in the study are listed with their target, concentration, and effect on F. tularensis LVS growth in broth. Inhibitors that decreased LVS growth in broth were removed from the study.

Symbols: ↔, no change in bacterial growth; ↓, decreased bacterial growth; ↑, increased bacterial growth.

FIG 3.

Inhibition of macrophage cPLA2 (pyrrophenone), PAP (propranolol), DAGL (RHC80267), or PLD (VU0155056) reduced F. tularensis-induced prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis by infected macrophages. (a) F. tularensis LVS was inoculated in broth medium and left untreated or incubated with inhibitors/vehicle and allowed to grow over 12 hours. Bacterial growth was measured as a function of absorbance at 600 nm. Curves represent average growth from 3 independent experiments. (b) BMDMs or RAW 264.7 macrophages were pretreated with inhibitors and then inoculated with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1; PGE2 in the supernatant was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay 24 hours after inoculation. Data represent means ± SEMs. n = 9 (BMDMs); n = 17 (RAW cells). (c) LIVE/DEAD Fixable Yellow stain analysis was performed to verify that inhibitors were not causing cell death or increased cell death during F. tularensis infection. BMDMs or RAW 264.7 macrophages were incubated with vehicle or inhibitor for 20 hours at 37°C (n = 6). Asterisks denote a statistical difference compared to the untreated infected group (P ≤ 0.05). Graphs are means of pooled experiments ± SEMs.

Phospholipase activity is not required for bacterial entry.

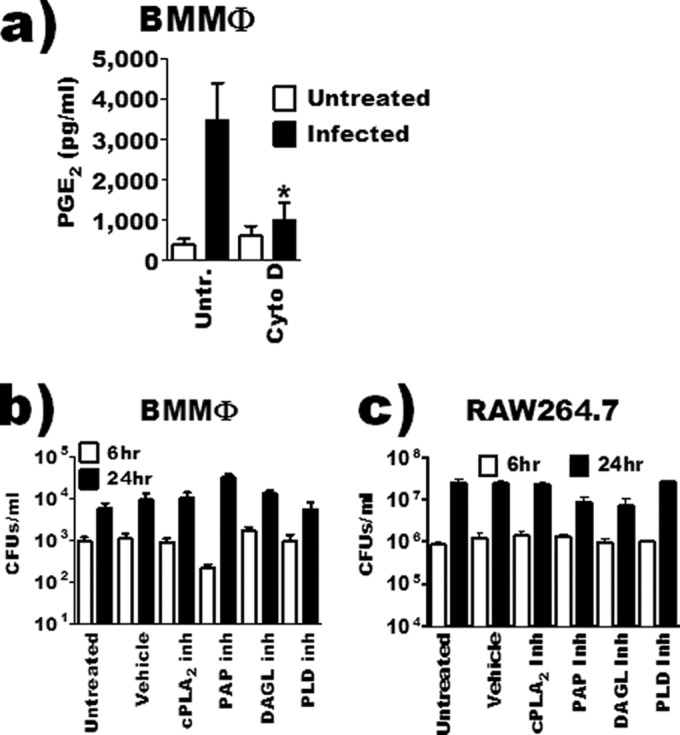

Phospholipases can be involved in membrane rearrangement and phagocytosis (27, 28). Thus, the reduction in detectable PGE2 by inhibitor-treated infected macrophages could be due to inhibition of bacterial uptake. We first wanted to determine if bacterial uptake was required for F. tularensis LVS-induced PGE2 synthesis. The actin polymerization inhibitor cytochalasin D (CD) has been extensively used to examine F. tularensis LVS-macrophage interactions as it inhibits F. tularensis LVS uptake into macrophages (29). Thus, to determine if macrophage uptake of F. tularensis is required for the induction of PGE2 biosynthesis, we treated BMDMs with CD (10 μM) 1 h prior to inoculation. This concentration of CD did not affect macrophage cell death (data not shown). Inhibition of actin rearrangement blocked F. tularensis-induced PGE2 biosynthesis by infected macrophages (Fig. 4a). Actin rearrangement is not required for normal inducible PGE2 biosynthesis as LPS-induced PGE2 biosynthesis is unaffected by CD treatment (30). These data suggest that macrophage uptake of F. tularensis LVS is required for induction of PGE2 biosynthesis. Although growth within the macrophage is not required for the induction of PGE2 biosynthesis (9), it is a key component of F. tularensis pathogenesis. Therefore, we wanted to determine the effects of phospholipase inhibition on F. tularensis uptake and intramacrophage growth. To determine if cPLA2, PLD, DAGL, or PAP activity was required for BMDM or RAW 264.7 uptake of F. tularensis LVS or intramacrophage growth, macrophages were treated with inhibitors 1 h prior to inoculation. Cells were lysed 6 h (to determine uptake) or 24 h (to determine intramacrophage growth) after inoculation, and a CFU assay was performed. The inhibition of cPLA2, PAP, DAGL, or PLD activity did not affect either bacterial entry or intramacrophage growth (Fig. 4b and c). These results suggest that F. tularensis entry into host macrophages is required for the induction of PGE2 biosynthesis and that the activities of cPLA2, PAP, DAGL, or PLD are dispensable for both bacterial uptake and intramacrophage growth.

FIG 4.

Inhibition of bacterial uptake blocks PGE2 biosynthesis by inoculated macrophages. (a) BMDMs were pretreated with 10 μM cytochalasin D (Cyto D) and then inoculated with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1, and PGE2 in the supernatant was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay 24 hours after inoculation (n = 3). (b and c) BMDMs (b) or RAW 264.7 macrophages (c) pretreated with inhibitors or vehicle and then inoculated with F. tularensis at an MOI of 200:1. At 6 and 24 hours after inoculation, macrophages were lysed and intramacrophage bacteria were quantified (n = 3). The asterisk denotes a statistical difference compared to the untreated F. tularensis-infected group (P ≤ 0.05). Graphs are means of pooled experiments ± SEMs.

Exogenous arachidonic acid restores PGE2 biosynthesis.

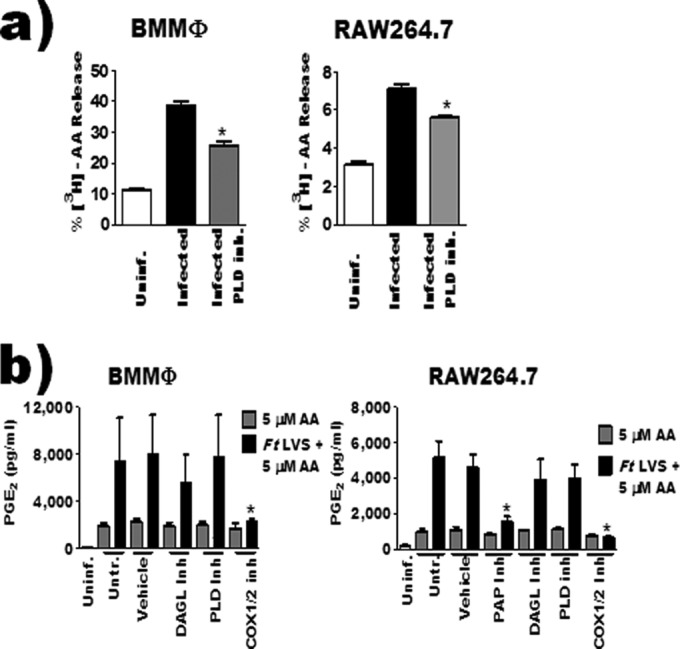

PLD binds phospholipid membranes to release phosphatidic acid. Thus, to determine if PLD was playing a role in the liberation of AA that could potentially contribute to PGE2 biosynthesis, BMDMs were inoculated with F. tularensis LVS in the presence or absence of the PLD inhibitor. Twenty hours after inoculation, radioactivity in the supernatant and cell fraction was measured. We chose 20 h after inoculation as this time corresponds with PGE2 synthesis in F. tularensis-infected macrophages. Inhibition of PLD results in reduced AA release compared to untreated infected macrophages (Fig. 5a). These data suggest that PLD is contributing to the pool of AA-derived lipids that are secreted by macrophages following F. tularensis LVS infection.

FIG 5.

Phospholipase D and diacylglycerol lipase contribute arachidonic acid for PGE2 biosynthesis. (a) RAW 264.7 macrophages labeled with [3H]arachidonic acid were treated with 10 μM VU0155056 1 hour prior to inoculation with F. tularensis LVS. Twenty hours after inoculation, radioactivity in the supernatant and cell fraction was measured by liquid scintillation and expressed as percent release (n = 3). (b) BMDMs or RAW 264.7 macrophages were pretreated with inhibitors and then inoculated with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1. Three hours after inoculation, 5 μM arachidonic acid was added to culture medium. PGE2 in the supernatant was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay 24 hours after inoculation (n = 4). Asterisks denote a statistical difference compared to the LVS-infected group (a) or the corresponding AA-treated group (b) (P ≤ 0.05). For clarity, the data from some experiments were presented in multiple figures. However, these experiments were run simultaneously and as such utilize the same controls (uninfected, infected, and COX-2 inhibitor treated). This includes Fig. 2c and d and panels a and b of this figure. Graphs are means of pooled experiments ± SEMs.

The precursor lipids that PAPs and DAGL modify can be dissociated from host membranes (Fig. 1). The fact that these lipids can be soluble makes it impractical to use the standard AA release assay to determine if these enzymes are contributing lipid precursors that are converted into PGE2 by F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages. Therefore, we again used the AA-addback assay to address the contribution of these enzymes to the generation of AA that was used for PGE2 biosynthesis by F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages. The observed decrease in F. tularensis LVS-induced BMDM cell death when pretreated with propranolol (Fig. 3c) would make interpretation of data from this experiment difficult. Thus, we decided to use propranolol treatment only with RAW 264.7 macrophages, as there was no difference in cell death between untreated and treated infected macrophages. We observed that the addition of AA to medium restored PGE2 biosynthesis in DAGL- or PLD-inhibited RAW 264.7 cells and BMDMs when infected with F. tularensis. AA was unable to restore PGE2 when cPLA2 (Fig. 2d) or PAP activity had been inhibited in infected RAW 264.7 macrophages (Fig. 5b). These data suggest that DAGL and PLD are likely providing AA that is being converted into PGE2 in F. tularensis-infected macrophages while cPLA2 and PAP are either regulating the PGE2 biosynthetic pathway independently of, or in addition to, liberation of AA. To ensure that inhibition of cPLA2 or PAP was not limiting AA uptake and incorporation into the macrophage, we pretreated RAW 264.7 macrophages with cPLA2 or PAP inhibitors for 1 h prior to overnight incubation with [3H]AA. Inhibiting cPLA2 or PAP did not affect uptake of [3H]AA (data not shown). Taken together, these data support our AA release results and suggest that macrophage PLD and DAGL activity, not cPLA2, contributes AA that is converted into PGE2 during F. tularensis infection of macrophages.

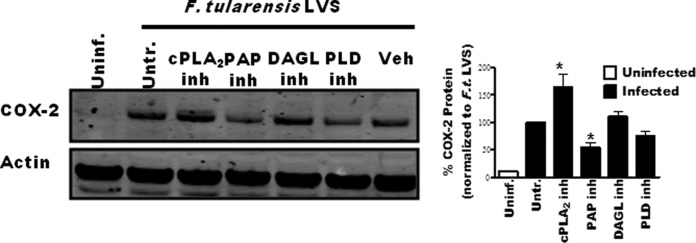

PAP inhibition decreases macrophage COX-2 protein levels during infection.

The regulation of COX-2 activity is at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional level with increases or decreases in cellular COX-2 protein levels correlating with overall cellular COX-2 activity (31, 32). Treatments that alter COX-2 protein levels are likely doing so by altering signal transduction events that regulate either the expression of ptgs2 (COX-2) or degradation of the transcript/protein. Inhibiting PAPs reduces LPS-induced increases in COX-2 protein as well as PGE2 synthesis by macrophages through a reduction in cellular levels of DAG, a critical secondary messenger (33). Thus, we hypothesized that inhibiting PAP activity would reduce F. tularensis-induced increases in COX-2 protein levels. We also wanted to determine if cPLA2, PLD, or DAGL activity influenced COX-2 protein levels in F. tularensis-infected macrophages. To determine this, we pretreated RAW 264.7 macrophages with inhibitors followed by inoculation with F. tularensis LVS. We then assessed COX-2 protein levels in total cell extracts 20 h after inoculation by Western blot analysis. The RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cell line was used in these experiments because the level of COX-2 protein in BMDMs is too low to be detected by Western blotting. We demonstrated that inhibiting macrophage PAP activity led to decreased COX-2 protein levels while inhibition of cPLA2 activity led to increased COX-2 (Fig. 6). Because COX-2 controls the rate-limiting step in the biosynthesis of PGE2, a 50% reduction in COX-2 protein levels will impact the amount of PGE2 that can be synthesized by a cell. However, the reduction in COX-2 protein is unlikely to be sufficient to result in complete loss of PGE2 synthesis observed in propranolol-treated F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages. Moreover, the observation that the inhibition of PAPs or cPLA2 results in altered COX-2 protein suggests that these enzymes may be involved in signaling pathways that contribute to macrophage function during F. tularensis infection.

FIG 6.

Inhibition of cPLA2 or PAP alters F. tularensis-induced COX-2 protein levels during infection. RAW 264.7 macrophages were pretreated with inhibitors and then inoculated with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1. Whole-cell extracts were collected 20 hours after inoculation, and COX-2 protein was quantified by Western blotting. A representative blot is shown with band intensity quantification of 6 independent experiments graphically represented. An asterisk denotes a statistical difference compared to the untreated infected group (P ≤ 0.05). Graphs are means of pooled experiments ± SEMs.

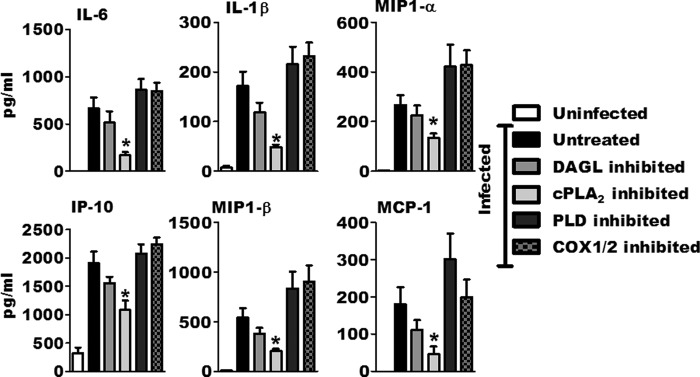

cPLA2 activity contributes to macrophage cytokine/chemokine production in response to F. tularensis LVS.

The observation that cPLA2 inhibition altered COX-2 protein levels in F. tularensis-infected macrophages suggested to us that cPLA2 could be contributing to other aspects of macrophage function in addition to PGE2 synthesis. To investigate this possibility, we decided to examine the contribution of phospholipase activity to macrophage cytokine/chemokine production in response to F. tularensis LVS. We performed a cytokine bead array to measure the concentration of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors secreted by infected macrophages when the activities of cPLA2, PLD, or DAGL were inhibited. As a control for prostaglandin-dependent changes in F. tularensis-induced cytokine production, we inhibited COX-1/2 activity as well. BMDMs were left untreated or pretreated with inhibitors for 1 h prior to mock inoculation or inoculation with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1. Twenty hours after inoculation, supernatants were analyzed for cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors. As has been previously reported (34), F. tularensis LVS infections of BMDMs resulted in increased granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), interleukin-1α (IL-1α), IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, IP-10, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MIP-2, and RANTES (data not shown). The inhibition of cPLA2 activity significantly reduced the concentrations of the cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β and the chemokines IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β (Fig. 7). The inhibition of DAGL, PLD, or COX-1/2 did not significantly alter macrophage cytokine/chemokine secretion. We also analyzed cytokine/chemokine secretion from infected propranolol-treated BMDMs. Supernatants from these cells had elevated concentrations of numerous cytokines and chemokines. However, as demonstrated above, the treatment of infected macrophages with propranolol increases cell survival, making it likely that the observed increase in cytokine secretion was due to a greater number of live macrophages (data not shown). These data suggest that cPLA2 activity contributes to macrophage function independently of PGE2 synthesis, though the mechanism by which cPLA2 affects macrophage function during F. tularensis LVS infection is still under investigation.

FIG 7.

Inhibition of cPLA2 alters macrophage cytokine and chemokine response to F. tularensis LVS. BMDMs were pretreated with inhibitors and then mock infected or inoculated with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1. Cytokine, chemokine, and growth factor concentrations in the supernatant were measured 24 hours after inoculation using a cytokine bead array (n = 3). An asterisk denotes a statistical difference compared to untreated, infected macrophages (P ≤ 0.05). Graphs are means of pooled experiments ± SEMs.

Lipin-1 and PAP2a are required for increases in COX-2 protein and PGE2 biosynthesis.

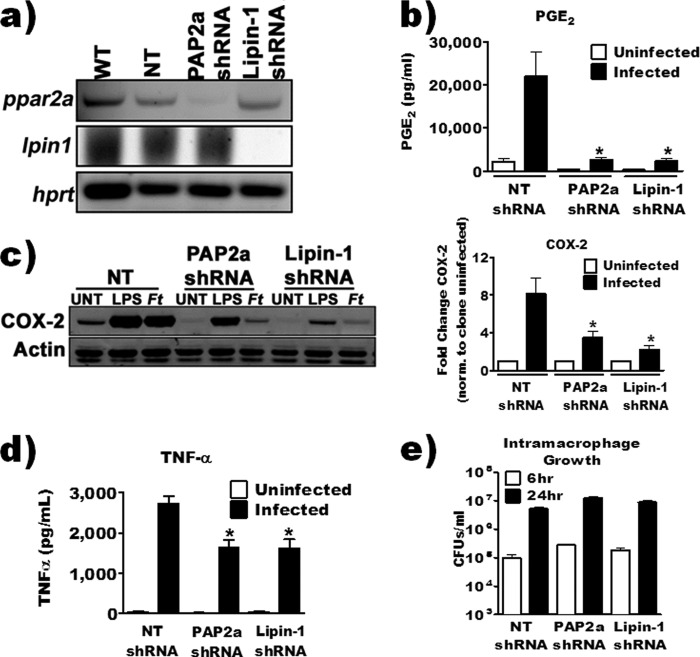

There are two distinct classes of PAP enzymes that possess phosphatidate phosphohydrolase activity. PAP1 enzymes are magnesium-dependent phosphohydrolases, while PAP2 enzymes are magnesium independent (35). Due to the nonspecific nature of propranolol (it inhibits both type 1 and type 2 PAPs [22]) and its targeting of β-adrenergic receptors (36), we decided to use shRNA to confirm the contribution of PAP enzymes to F. tularensis LVS-induced PGE2 synthesis. The best-characterized PAP enzymes are lipin-1 and PAP2a (LPP1). PAP2a is a 31-kDa, transmembrane, broad-specificity phosphohydrolase involved in lipid signaling (37). Lipin-1 is a 97-kDa protein involved in de novo lipid synthesis, lipid signaling, and adipocyte development and has a more specific substrate preference for phosphatidic acid (PA) than does PAP2a (38). Using shRNA, we generated RAW 264.7 macrophage cell lines that were depleted of lipin-1 or PAP2a. We had difficulty quantifying PAP2a or lipin-1 protein levels in whole-cell extracts by Western blotting due to poor antibody specificity. Therefore, we, like others (39, 40), used mRNA transcript levels of lipin-1 and PAP2a to confirm knockdown of intended targets (Fig. 8a).

FIG 8.

shRNA knockdown of macrophage PAP2a or lipin-1 reduced PGE2 biosynthesis and COX-2 by F. tularensis-infected macrophages. (a) Steady-state mRNA was collected from wild-type (WT) RAW 264.7, knockdown, or nontarget shRNA cell lines, and knockdown was confirmed by RT-PCR. (b) RAW 264.7 knockdown or nontarget cell lines were inoculated with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1. PGE2 in the supernatant was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay 24 hours after inoculation (n = 3). (c) Knockdown or nontarget cell lines were inoculated with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1. Whole-cell lysates were collected 20 hours after inoculation, and COX-2 protein was quantified by Western blotting. Data are expressed as a fold change in COX-2 band intensity compared to its respective uninfected control (n = 4). (d) RAW 264.7 knockdown or nontarget cell lines were inoculated with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1. TNF-α in the supernatant was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay at 24 hours postinoculation (n = 3). (e) Knockdown or nontarget cell lines were inoculated with F. tularensis LVS at an MOI of 200:1. At 6 and 24 hours postinoculation, macrophages were lysed and intramacrophage bacteria were quantified (n = 3). An asterisk denotes a statistical difference compared to the nontarget (NT) shRNA-infected group (P ≤ 0.05). Graphs are means of pooled experiments ± SEMs.

Lipin-1- and PAP2a-depleted cell lines were used to investigate the contribution of these enzymes to F. tularensis LVS-induced COX-2 protein levels and PGE2 synthesis. We infected the RAW 264.7 shRNA knockdown cells with F. tularensis at an MOI of 200:1 and then quantified PGE2 in supernatants and COX-2 protein levels 20 h after inoculation. Depletion of either lipin-1 or PAP2a resulted in a significant decrease in both COX-2 protein and detectable PGE2 compared to control RAW 264.7 macrophages (nontarget shRNA) (Fig. 8b and c). These data confirm results that we obtained with propranolol and suggest that both lipin-1 and PAP2a enzymes contribute to F. tularensis-induced PGE2 biosynthesis by infected macrophages. We decided to also examine the contribution of lipin-1 and PAP2a to the macrophage inflammatory response toward F. tularensis LVS by quantifying tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) concentration in supernatants from infected macrophages. The loss of lipin-1 or PAP2a resulted in decreased TNF-α secretion (Fig. 8d). The loss of PGE2, COX-2, and TNF-α is unlikely to be due to either an alteration of bacterial uptake by macrophages or a lack of intramacrophage growth as there was no difference between control macrophages and depleted macrophages in these aspects (Fig. 8e). These results suggest that PAP2a and lipin-1 contribute to signal transduction events that regulate aspects of macrophage function during F. tularensis LVS infection. We are currently investigating the molecular contribution of these enzymes to macrophage function during infection.

DISCUSSION

As seen with other intracellular bacterial pathogens, Francisella tularensis infection of macrophages leads to increased biosynthesis of PGE2 by these host cells, and the synthesis of prostanoids is beneficial to the bacterium and detrimental to the host (12, 41–43). We also established that the activities of the major enzymes in the inducible PG biosynthetic pathway (cPLA2, COX-2, and mPGES1) are indispensable for F. tularensis LVS-induced PGE2 biosynthesis (8, 18). However, there is a temporal disconnect between the activation of cPLA2 (via phosphorylation) and COX-2 protein increases during F. tularensis LVS infection. This suggested to us that other enzymes besides cPLA2 might also contribute to the liberation of AA that is converted into PGE2 by F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages. In this study, we demonstrate that the phospholipase PLD and the lipase DAGL likely supply AA to be converted into PGE2 by F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages. Furthermore, we provide evidence that cPLA2 and the PAPs lipin-1 and PAP2a regulate macrophage-mediated inflammation during F. tularensis LVS infection. F. tularensis LVS AcpA has been reported to have phospholipase C activity (44). However, we have already demonstrated that this enzyme is not required for Francisella-induced PGE2 synthesis (9), and from the fact that none of the inhibitors used in this work inhibited either broth growth or intramacrophage growth, it seems unlikely that the results observed are due to inhibition of bacterial phospholipase activity. As such, this study provides evidence that modulation of macrophage lipid metabolism by F. tularensis LVS contributes not only to eicosanoid production but also to macrophage-mediated inflammation.

cPLA2 is considered the primary enzyme responsible for the liberation of arachidonic acid that contributes to eicosanoid production during inflammation; this includes the production of prostaglandins (45). We have previously demonstrated the requirement of cPLA2 for F. tularensis LVS-induced PGE2 synthesis; however, the observed temporal disconnect between cPLA2 activation and detectable PGE2 synthesis suggested that cPLA2 was not supplying AA that was being converted into PGE2 in these infected macrophages (18). Our results demonstrating that cPLA2 inhibition only partially blocks late AA release or that the addition of exogenous AA does not restore PGE2 biosynthesis by cPLA2-inhibited infected macrophages would support this model. There is evidence that arachidonate distribution within macrophages can influence the generation of eicosanoids, including PGE2 (46). During the Lands cycle, arachidonate is liberated by cPLA2 and reincorporated into phospholipids by coenzyme A (CoA)-dependent acyltransferases (47, 48). However, the addition of exogenous AA should overcome even this step and restore PGE2 biosynthesis, and this was not observed in cPLA2-inhibited macrophages. Further studies examining the cellular localization of cPLA2 during F. tularensis infection are required to better understand the spatial-temporal regulation of this enzyme and its contribution to F. tularensis-induced PGE2 biosynthesis. While exogenous AA did not restore PGE2 biosynthesis in F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages when cPLA2 activity was inhibited, it did restore PGE2 biosynthesis when the activity of PLD or DAGL was inhibited. These results point to an alternative pathway of AA liberation involving PLD and DAGL in F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages. Alternative enzymatic pathways that liberate AA for conversion into prostanoids have been noted in neurons (20) but, as far as we know, not in macrophages. The immediate lipid product generated by PLD or DAGL activity is not AA. However, 2-acylglycerol can be generated from the PLD-generated metabolite PA by the sequential activities of PAP and DAGL. 2-Arachidonoyl glycerol can also serve as a substrate for COX-2 (49) and be converted into PGE2-glycerol (PGE2-G). Therefore, it is possible that some of the PGE2 that we detect from F. tularensis-infected macrophages may actually be PGE2-G derived from 2-arachidonoyl glycerol. PGE2-G may have an enhanced anti-inflammatory capacity compared to that of PGE2, as it better inhibits LPS-induced NF-κB activity, and this may suggest why the induction of the inducible PGE2 synthesis pathway in macrophages by F. tularensis LVS so effectively inhibits T cell responses (50). Detailed mass spectrometric analysis of the lipid species present within macrophages during F. tularensis infection will be required to determine if PGE2-G is indeed present. Regardless, our data suggest that cPLA2 is likely not providing precursor metabolites to be converted into PGE2 in F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages, while PLD and DAGL activities are.

Although our data suggest that cPLA2 is likely not contributing AA to be converted into PGE2 in F. tularensis LVS-infected macrophages, they do demonstrate that F. tularensis LVS induction of cPLA2 activity contributes to the inflammatory state of these infected macrophages. The inhibition of cPLA2 reduces F. tularensis LVS-induced cytokine responses while enhancing F. tularensis LVS-induced COX-2 protein levels. Interestingly, these responses are not recapitulated by inhibition of COX-1/2 activity, suggesting that these effects are mediated by eicosanoids not of the prostaglandin family. cPLA2-derived AA can contribute to the production of leukotrienes, which have immunomodulatory activity in macrophages (51, 52). If cPLA2 does contribute to macrophage proinflammatory responses, then the dephosphorylation of cPLA2 that we observed would likely abrogate these proinflammatory responses. At some time later, the activation of an alternative pathway for liberation of AA, specifically PLD and DAGL, would allow for the production of anti-inflammatory prostaglandins without the requirement for cPLA2 activity. This modulation of cPLA2, PLD, and DAGL activity by F. tularensis LVS could result in the inhibition of detrimental proinflammatory eicosanoids while still allowing for the production of anti-inflammatory eicosanoids in vivo, thus providing a survival advantage. The inhibition of cPLA2, PLD, and DAGL does not affect F. tularensis LVS intramacrophage growth, suggesting that the responses mediated by these enzymes are more important for altering the in vivo milieu to create a favorable environment for bacterial survival. Future experiments will be required to better dissect how different eicosanoids influence F. tularensis LVS infections in vivo and the possible roles for cPLA2, PLD, and DAGL in those responses. Regardless, our data suggest that alteration of cPLA2, PLD, and DAGL activity contributes to F. tularensis LVS alteration of macrophage function.

The PAP inhibitor utilized in many studies (33) indiscriminately inhibits the activity of all identified PAPs (22). Thus, we decided to determine which PAPs were involved in F. tularensis-induced PGE2 synthesis. Using shRNA to knock down two prominent PAP enzymes, PAP2a and lipin-1, we show that both of these PAPs regulate COX-2 protein levels and PGE2 biosynthesis in response to F. tularensis. Lipin-1 can function as a transcriptional coactivator of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha/gamma (PPARα/γ) as well as NFAT (53, 54) in addition to its PAP activity. Through its nuclear localization and transcriptional coactivation, lipin-1 has also been shown to be essential for adipocyte development, with mutations in the lipin-1 gene producing lipodystrophy and fatty liver disease (55). Given that members of the PPAR family of transcriptional coactivators have been linked to macrophage polarization, we are interested in determining if lipin-1 transcriptional coactivation activity is contributing to the macrophage phenotypes seen in our study. Lipin-1 has also been demonstrated to play a role in the generation of lipid droplets (LDs) within human macrophages, where knockdown of lipin-1 reduced the size and number of LDs (56). The PAP activity of lipin-1 produces DAG, which can be used to generate triacylglycerols, which are central components of LD structure. However, DAG is a potent inducer of proinflammatory signaling in macrophages (57). Lipin-1 has been suggested to induce COX-2 protein levels via DAG formation; however, these studies used nonspecific inhibitors (33). Our results using lipin-1-depleted macrophages confirm the requirement of lipin-1 for increases in COX-2 protein levels. Future work will determine which activities, either cotransactivator or enzymatic, of lipin-1 contribute to F. tularensis-induced macrophage activation.

PAP2s are membrane-bound, lipid phosphohydrolases that have ectoactivity, i.e., their catalytic active site is present on the outside of cells. PAP2 ectoactivity regulates cell signaling by modifying the concentrations of lipid phosphatases versus their dephosphorylated products; this includes the conversion of sphingosine-1 phosphate (S1P) to sphingosine and of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) to monoacylglycerols. We demonstrate here that PAP2a contributes to F. tularensis-induced macrophage activation. Specifically, the loss of PAP2a reduces F. tularensis-induced COX-2, PGE2, and TNF-α levels. The loss of PAP2a should increase the extracellular concentration of S1P and LPA. S1P and LPA are potent signaling lipids that can alter macrophage function (58). However, there is not a consensus on whether these lipid mediators have inflammatory or anti-inflammatory control over macrophage responses. S1P enhances macrophage Fcε receptor expression, phagocytosis, and LPS-induced cytokine responses (59–61). LPA stimulation results in calcium mobilization in human monocytes and inhibition of TNF-α production in LPS-treated mice (62, 63). In contrast, S1P can induce an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype, while S1P receptor 3 is required for recruitment of anti-inflammatory monocytes to atherosclerotic plaques (64, 65). The contrasting results suggest that the effects of S1P and LPA are context dependent. How PAP2a contributes to S1P and LPA function on macrophages is entirely unknown, though our data suggest that this enzyme does contribute to macrophage function. We are currently investigating levels of LPA and S1P in F. tularensis-infected macrophages and whether these levels are altered in our PAP2a-depleted macrophages. More work is clearly required to begin to decipher the complex relationship between lipid mediators, the enzymes that regulate their concentrations, and the effect that they have on immunologic responses both during normal function and during infections such as tularemia.

We believe that our results suggest an alternative pathway for supplying AA into the PGE2 biosynthetic pathway during F. tularensis infection of macrophages. We demonstrate that liberation of AA to be converted into PGE2 in F. tularensis-infected macrophages is likely not due to cPLA2 activity but occurs via PLD and DAGL activity. cPLA2 can also contribute to the generation of proinflammatory eicosanoids in addition to anti-inflammatory eicosanoids and may be contributing to the generation of proinflammatory cytokine responses during F. tularensis LVS macrophage infection. In addition, our data also identified the unexpected contribution of PAP2a and lipin-1 to F. tularensis-mediated macrophage activation. Thus, by targeting host lipid signaling pathways, F. tularensis is able to mute proinflammatory responses while maintaining anti-inflammatory eicosanoid production to promote its own survival. Future work will define the molecular mechanisms by which cPLA2 and the PAPs lipin-1 and PAP2a regulate macrophage function. Understanding the contribution of lipid metabolic pathways toward inflammatory responses could potentially aid in the development of immunomodulatory therapies to treat F. tularensis infections and/or enhance vaccine development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David McGee, Robert Chervenak, and Kenneth Peterson for helpful conversations and critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the NIH/NIAID grant K22AI83373-2 and a Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport grant-in-aid.

Author contributions were as follows: A.R.N. and M.D.W. designed experiments; A.R.N., J.D.B., and A.M.B. performed experiments; A.R.N. and M.D.W. analyzed data and wrote the paper.

There is no conflicting financial interest among the authors.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 May 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Dienst FT., Jr 1963. Tularemia: a perusal of three hundred thirty-nine cases. J. La. State Med. Soc. 115:114–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saslaw S, Eigelsbach HT, Prior JA, Wilson HE, Carhart S. 1961. Tularemia vaccine study. II. Respiratory challenge. Arch. Intern. Med. 107:702–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennis DT, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Fine AD, Friedlander AM, Hauer J, Layton M, Lillibridge SR, McDade JE, Osterholm MT, O'Toole T, Parker G, Perl TM, Russell PK, Tonat K. 2001. Tularemia as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA 285:2763–2773. 10.1001/jama.285.21.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher-Smith M, Kim J, Al-Bawardy R, Josko D. 2004. Francisella tularensis: possible agent in bioterrorism. Clin. Lab. Sci. 17:35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron GS, Nano FE. 1998. MglA and MglB are required for the intramacrophage growth of Francisella novicida. Mol. Microbiol. 29:247–259. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrigan LM, Tuladhar S, Brunton JC, Woolard MD, Chen CJ, Saini D, Frothingham R, Sempowski GD, Kawula TH, Frelinger JA. 2013. Infection with Francisella tularensis LVS clpB leads to an altered yet protective immune response. Infect. Immun. 81:2028–2042. 10.1128/IAI.00207-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones CL, Napier BA, Sampson TR, Llewellyn AC, Schroeder MR, Weiss DS. 2012. Subversion of host recognition and defense systems by Francisella spp. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 76:383–404. 10.1128/MMBR.05027-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woolard MD, Wilson JE, Hensley LL, Jania LA, Kawula TH, Drake JR, Frelinger JA. 2007. Francisella tularensis-infected macrophages release prostaglandin E2 that blocks T cell proliferation and promotes a Th2-like response. J. Immunol. 178:2065–2074. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woolard MD, Barrigan LM, Fuller JR, Buntzman AS, Bryan J, Manoil C, Kawula TH, Frelinger JA. 2013. Identification of Francisella novicida mutants that fail to induce prostaglandin E(2) synthesis by infected macrophages. Front. Microbiol. 4:16. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker C, Kristensen F, Bettens F, deWeck AL. 1983. Lymphokine regulation of activated (G1) lymphocytes. I. Prostaglandin E2-induced inhibition of interleukin 2 production. J. Immunol. 130:1770–1773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Penarrubia P, Bankhurst AD, Koster FT. 1989. Prostaglandins from human T suppressor/cytotoxic cells modulate natural killer antibacterial activity. J. Exp. Med. 170:601–606. 10.1084/jem.170.2.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woolard MD, Hensley LL, Kawula TH, Frelinger JA. 2008. Respiratory Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain infection induces Th17 cells and prostaglandin E2, which inhibits generation of gamma interferon-positive T cells. Infect. Immun. 76:2651–2659. 10.1128/IAI.01412-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elkins KL, Rhinehart-Jones TR, Culkin SJ, Yee D, Winegar RK. 1996. Minimal requirements for murine resistance to infection with Francisella tularensis LVS. Infect. Immun. 64:3288–3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortier AH, Polsinelli T, Green SJ, Nacy CA. 1992. Activation of macrophages for destruction of Francisella tularensis: identification of cytokines, effector cells, and effector molecules. Infect. Immun. 60:817–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson JE, Katkere B, Drake JR. 2009. Francisella tularensis induces ubiquitin-dependent major histocompatibility complex class II degradation in activated macrophages. Infect. Immun. 77:4953–4965. 10.1128/IAI.00844-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi HY, Shelhamer JH. 2005. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling regulates cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation and lipid generation in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 280:38969–38975. 10.1074/jbc.M509352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamberg M, Samuelsson B. 1973. Detection and isolation of an endoperoxide intermediate in prostaglandin biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 70:899–903. 10.1073/pnas.70.3.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brummett AM, Navratil AR, Bryan JD, Woolard MD. 16 December 2013. Janus kinase 3 activity is necessary for the phosphorylation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 and prostaglandin E2 synthesis by macrophages infected with Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. Infect. Immun. 10.1128/IAI.01461-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen AC, Gammon CM, Ousley AH, McCarthy KD, Morell P. 1992. Bradykinin stimulates arachidonic acid release through the sequential actions of an sn-1 diacylglycerol lipase and a monoacylglycerol lipase. J. Neurochem. 58:1130–1139. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morell P, Allen AC, Gammon CM, Lyons SA. 1991. Arachidonate release consequent to bradykinin-stimulated phospholipid metabolism in dorsal root ganglion cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 19:411–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bisogno T, Howell F, Williams G, Minassi A, Cascio MG, Ligresti A, Matias I, Schiano-Moriello A, Paul P, Williams EJ, Gangadharan U, Hobbs C, Di Marzo V, Doherty P. 2003. Cloning of the first sn1-DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J. Cell Biol. 163:463–468. 10.1083/jcb.200305129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kai M, Wada I, Imai S, Sakane F, Kanoh H. 1997. Cloning and characterization of two human isozymes of Mg2+-independent phosphatidic acid phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 272:24572–24578. 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hefner Y, Borsch-Haubold AG, Murakami M, Wilde JI, Pasquet S, Schieltz D, Ghomashchi F, Yates JR, III, Armstrong CG, Paterson A, Cohen P, Fukunaga R, Hunter T, Kudo I, Watson SP, Gelb MH. 2000. Serine 727 phosphorylation and activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 by MNK1-related protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 275:37542–37551. 10.1074/jbc.M003395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott SA, Selvy PE, Buck JR, Cho HP, Criswell TL, Thomas AL, Armstrong MD, Arteaga CL, Lindsley CW, Brown HA. 2009. Design of isoform-selective phospholipase D inhibitors that modulate cancer cell invasiveness. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5:108–117. 10.1038/nchembio.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stella N, Schweitzer P, Piomelli D. 1997. A second endogenous cannabinoid that modulates long-term potentiation. Nature 388:773–778. 10.1038/42015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pappu AS, Hauser G. 1983. Propranolol-induced inhibition of rat brain cytoplasmic phosphatidate phosphohydrolase. Neurochem. Res. 8:1565–1575. 10.1007/BF00964158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusner DJ, Hall CF, Schlesinger LS. 1996. Activation of phospholipase D is tightly coupled to the phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis or opsonized zymosan by human macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 184:585–595. 10.1084/jem.184.2.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ali WH, Chen Q, Delgiorno KE, Su W, Hall JC, Hongu T, Tian H, Kanaho Y, Di Paolo G, Crawford HC, Frohman MA. 2013. Deficiencies of the lipid-signaling enzymes phospholipase D1 and D2 alter cytoskeletal organization, macrophage phagocytosis, and cytokine-stimulated neutrophil recruitment. PLoS One 8:e55325. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai XH, Golovliov I, Sjostedt A. 2001. Francisella tularensis induces cytopathogenicity and apoptosis in murine macrophages via a mechanism that requires intracellular bacterial multiplication. Infect. Immun. 69:4691–4694. 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4691-4694.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shibata Y. 1995. Prostaglandin E2 release triggered by phagocytosis of latex particles. A distinct association with prostaglandin synthase isozymes in bone marrow macrophages. J. Immunol. 154:2878–2887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lasa M, Mahtani KR, Finch A, Brewer G, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. 2000. Regulation of cyclooxygenase 2 mRNA stability by the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 signaling cascade. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:4265–4274. 10.1128/MCB.20.12.4265-4274.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D'Acquisto F, Iuvone T, Rombola L, Sautebin L, Di Rosa M, Carnuccio R. 1997. Involvement of NF-kappaB in the regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 protein expression in LPS-stimulated J774 macrophages. FEBS Lett. 418:175–178. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01377-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grkovich A, Johnson CA, Buczynski MW, Dennis EA. 2006. Lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human U937 macrophages is phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase-1-dependent. J. Biol. Chem. 281:32978–32987. 10.1074/jbc.M605935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paranavitana C, Pittman P, Velauthapillai M, DaSilva L. 2008. Temporal cytokine profiling of Francisella tularensis-infected human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 41:192–199. 10.1111/2049-632X.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carman GM. 2006. Roles of phosphatidate phosphatase enzymes in lipid metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31:694–699. 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrett AM, Cullum VA. 1968. The biological properties of the optical isomers of propranolol and their effects on cardiac arrhythmias. Br. J. Pharmacol. 34:43–55. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1968.tb07949.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts R, Sciorra VA, Morris AJ. 1998. Human type 2 phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolases. Substrate specificity of the type 2a, 2b, and 2c enzymes and cell surface activity of the 2a isoform. J. Biol. Chem. 273:22059–22067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nanjundan M, Possmayer F. 2003. Pulmonary phosphatidic acid phosphatase and lipid phosphate phosphohydrolase. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 284:L1–L23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts RZ, Morris AJ. 2000. Role of phosphatidic acid phosphatase 2a in uptake of extracellular lipid phosphate mediators. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1487:33–49. 10.1016/S1388-1981(00)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valdearcos M, Esquinas E, Meana C, Pena L, Gil-de-Gomez L, Balsinde J, Balboa MA. 2012. Lipin-2 reduces proinflammatory signaling induced by saturated fatty acids in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 287:10894–10904. 10.1074/jbc.M112.342915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petit JC, Richard G, Burghoffer B, Daguet GL. 1985. Suppression of cellular immunity to Listeria monocytogenes by activated macrophages: mediation by prostaglandins. Infect. Immun. 49:383–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koster FT, Williams JC, Goodwin JS. 1985. Cellular immunity in Q fever: specific lymphocyte unresponsiveness in Q fever endocarditis. J. Infect. Dis. 152:1283–1289. 10.1093/infdis/152.6.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edwards CK, III, Hedegaard HB, Zlotnik A, Gangadharam PR, Johnston RB, Jr, Pabst MJ. 1986. Chronic infection due to Mycobacterium intracellulare in mice: association with macrophage release of prostaglandin E2 and reversal by injection of indomethacin, muramyl dipeptide, or interferon-gamma. J. Immunol. 136:1820–1827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Felts RL, Reilly TJ, Tanner JJ. 2006. Structure of Francisella tularensis AcpA: prototype of a unique superfamily of acid phosphatases and phospholipases C. J. Biol. Chem. 281:30289–30298. 10.1074/jbc.M606391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gijon MA, Spencer DM, Siddiqi AR, Bonventre JV, Leslie CC. 2000. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is required for macrophage arachidonic acid release by agonists that do and do not mobilize calcium. Novel role of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in cytosolic phospholipase A2 regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20146–20156. 10.1074/jbc.M908941199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Astudillo AM, Perez-Chacon G, Meana C, Balgoma D, Pol A, Del Pozo MA, Balboa MA, Balsinde J. 2011. Altered arachidonate distribution in macrophages from caveolin-1 null mice leading to reduced eicosanoid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 286:35299–35307. 10.1074/jbc.M111.277137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perez-Chacon G, Astudillo AM, Balgoma D, Balboa MA, Balsinde J. 2009. Control of free arachidonic acid levels by phospholipases A2 and lysophospholipid acyltransferases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791:1103–1113. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chilton FH, Fonteh AN, Surette ME, Triggiani M, Winkler JD. 1996. Control of arachidonate levels within inflammatory cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1299:1–15. 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kozak KR, Rowlinson SW, Marnett LJ. 2000. Oxygenation of the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonylglycerol, to glyceryl prostaglandins by cyclooxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 275:33744–33749. 10.1074/jbc.M007088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu SS, Bradshaw HB, Chen JS, Tan B, Walker JM. 2008. Prostaglandin E2 glycerol ester, an endogenous COX-2 metabolite of 2-arachidonoylglycerol, induces hyperalgesia and modulates NFkappaB activity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153:1538–1549. 10.1038/bjp.2008.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rola-Pleszczynski M, Gagnon L, Chavaillaz PA. 1988. Immune regulation by leukotriene B4. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 524:218–226. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb38545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rola-Pleszczynski M, Stankova J. 1992. Leukotriene B4 enhances interleukin-6 (IL-6) production and IL-6 messenger RNA accumulation in human monocytes in vitro: transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms. Blood 80:1004–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim HB, Kumar A, Wang L, Liu GH, Keller SR, Lawrence JC, Jr, Finck BN, Harris TE. 2010. Lipin 1 represses NFATc4 transcriptional activity in adipocytes to inhibit secretion of inflammatory factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30:3126–3139. 10.1128/MCB.01671-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Finck BN, Gropler MC, Chen Z, Leone TC, Croce MA, Harris TE, Lawrence JC, Jr, Kelly DP. 2006. Lipin 1 is an inducible amplifier of the hepatic PGC-1alpha/PPARalpha regulatory pathway. Cell Metab. 4:199–210. 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peterfy M, Phan J, Xu P, Reue K. 2001. Lipodystrophy in the fld mouse results from mutation of a new gene encoding a nuclear protein, lipin. Nat. Genet. 27:121–124. 10.1038/83685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valdearcos M, Esquinas E, Meana C, Gil-de-Gomez L, Guijas C, Balsinde J, Balboa MA. 2011. Subcellular localization and role of lipin-1 in human macrophages. J. Immunol. 186:6004–6013. 10.4049/jimmunol.1003279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sands WA, Clark JS, Liew FY. 1994. The role of a phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C in the production of diacylglycerol for nitric oxide synthesis in macrophages activated by IFN-gamma and LPS. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 199:461–466. 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pettus BJ, Bielawski J, Porcelli AM, Reames DL, Johnson KR, Morrow J, Chalfant CE, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. 2003. The sphingosine kinase 1/sphingosine-1-phosphate pathway mediates COX-2 induction and PGE2 production in response to TNF-alpha. FASEB J. 17:1411–1421. 10.1096/fj.02-1038com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McQuiston T, Luberto C, Del Poeta M. 2010. Role of host sphingosine kinase 1 in the lung response against Cryptococcosis. Infect. Immun. 78:2342–2352. 10.1128/IAI.01140-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duong CQ, Bared SM, Abu-Khader A, Buechler C, Schmitz A, Schmitz G. 2004. Expression of the lysophospholipid receptor family and investigation of lysophospholipid-mediated responses in human macrophages. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1682:112–119. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hammad SM, Crellin HG, Wu BX, Melton J, Anelli V, Obeid LM. 2008. Dual and distinct roles for sphingosine kinase 1 and sphingosine 1 phosphate in the response to inflammatory stimuli in RAW macrophages. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 85:107–114. 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fueller M, Wang DA, Tigyi G, Siess W. 2003. Activation of human monocytic cells by lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine-1-phosphate. Cell. Signal. 15:367–375. 10.1016/S0898-6568(02)00117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fan H, Zingarelli B, Harris V, Tempel GE, Halushka PV, Cook JA. 2008. Lysophosphatidic acid inhibits bacterial endotoxin-induced pro-inflammatory response: potential anti-inflammatory signaling pathways. Mol. Med. 14:422–428. 10.2119/2007-00106.Fan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Awojoodu AO, Ogle ME, Sefcik LS, Bowers DT, Martin K, Brayman KL, Lynch KR, Peirce-Cottler SM, Botchwey E. 2013. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 3 regulates recruitment of anti-inflammatory monocytes to microvessels during implant arteriogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:13785–13790. 10.1073/pnas.1221309110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hughes JE, Srinivasan S, Lynch KR, Proia RL, Ferdek P, Hedrick CC. 2008. Sphingosine-1-phosphate induces an antiinflammatory phenotype in macrophages. Circ. Res. 102:950–958. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.170779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]