Abstract

We developed a dispersal method for multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) that allows quantitative assessment of dispersion on pro-fibrogenic responses in tissue culture cells as well as in mouse lung. Here we demonstrate that the dispersal of as-prepared (AP), purified (PD), and carboxylated (COOH) MWCNTs by bovine serum albumin (BSA) and dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) influences TGF-β1, PDGF-AA and IL-1β production in vitro and in vivo. These biomarkers were chosen based on their synergy in promoting fibrogenesis and cellular communication in the epithelial-mesenchymal cell trophic unit in the lung. The effect of dispersal was most noticeable in AP- and PD-MWCNTs, which are more hydrophobic and unstable in aqueous buffers than hydrophilic COOH-MWCNTs. Well-dispersed AP- and PD-MWCNTs were readily taken up by BEAS-2B, THP-1 cells and alveolar macrophages (AM), and induced more prominent TGF-β1 and IL-1β production in vitro as well as TGF-β1, IL-1β and PDGF-AA production in vivo than non-dispersed tubes. Moreover, there was good agreement between the pro-fibrogenic responses in vitro and in vivo as well as the ability of dispersed tubes to generate granulomatous inflammation and fibrosis in airways. Tube dispersal also elicited more robust IL-1β production in THP-1 cells. While COOH-MWCNTs were poorly taken up in BEAS-2B and induced little TGF-β1 production, they were bio-processed by AM and induced less prominent collagen deposition at sites of non-granulomatous inflammation in the alveolar region. Taken together, these results indicate that the dispersal state of MWCNTs affects pro-fibrogenic cellular responses that correlate with the extent of pulmonary fibrosis and are of potential use to predict pulmonary toxicity.

Keywords: multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT), dispersion, TGF-β1, PDGF-AA, IL-1β collagen, lung fibrosis

The novel properties of carbon nanotubes (CNTs), including their high mechanical strength, enhanced electrical conductivity and excellent physicochemical stability have led to widespread use in electronics, energy storage, sensors, composite materials and biomedical applications.1–5 In spite of these enviable characteristics, CNTs also exhibit properties that could render them hazardous under biological conditions.3, 6–10 This includes the ability of multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) to act as bio-indestructible fibers in the lung, with the potential to induce pulmonary injury.6–18 While currently there are no studies showing adverse health effects in workers or consumers, a high level of concern has been raised by animal studies showing that MWCNTs exhibit an equal or greater potential for pulmonary toxicity than crystalline silica and asbestos. For instance, CNTs have been shown to generate early onset and persistent pulmonary fibrosis in short-term and subchronic studies in rodents.17–20 Moreover, MWCNTs have been observed to migrate from pulmonary alveoli to the pleura where it is theoretically possible that they could induce the development of mesothelioma.14, 16, 20

In addition to their slow rate of clearance from the lung and biopersistance, MWCNTs exhibit a number of properties that could contribute to their ability to induce pulmonary fibrosis.7, 8, 21, 22 These include the high aspect ratio of the tubes and their relatively high degree of hydrophobicity in the raw state, leading to the formation of tube stacks that are retained as fiber-like substances in pulmonary airways, alveoli, the interstitium and pleura.7, 8, 21, 22 From a disease promoting perspective, longer and more rigid tubes are more prone to generating frustrated phagocytosis in macrophages, where the failure to wrap the tubes in phagosomes leads to the release of reactive oxygen species and hydrolytic enzymes that may induce chronic granulomatous inflammation.8, 14, 23–27 In addition, activation of the NALP 3 inflammasome and IL-1β production could contribute to the inflammatory response to high aspect ratio materials.28– 30 The extent and localization of inflammation in the lung is dependent on the state of tube dispersal as well as their agglomeration, as illustrated by the finding that better dispersed SWCNTs readily gain access to the alveoli and interstitial space where they generate peri-alveolar fibrosis, while more agglomerated tubes generate granulomatous inflammation and fibrosis in larger airways.17, 18, 22, 31 Additional CNT characteristics that could contribute to adverse biological outcomes include the tubes’ purification stage, content of residual metal catalysts and surface functionalization (e.g., carboxylation).

Fibrotic reactions in the airways or the lung interstitium constitute a common pathologic outcome following exposure to toxic substances such as inhaled particles, fibers and metals.18, 22, 32–34 There is cumulative understanding of the importance of cooperation among epithelial cells, macrophages and fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis.32–34 Epithelial injury can lead to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which represents a graded cellular transformation process in which the epithelial cells acquire reversible mesenchymal features that could culminate in their differentiation to myofibroblasts or fibroblasts.32, 34 The release of chemokines by injured epithelial cells attracts macrophages contributing to EMT through the production of IL-1β, TGF-β1 and proteases.32 The evolving myofibroblasts and fibroblasts migrate into the space surrounding small airways and alveoli where they deposit extracellular matrix and collagen in amounts proportional to the injurious stimulus as well as the rate and extent at which the mesenchymal elements undergo growth arrest and apoptosis.32 The production of a family of platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs) by mesenchymal cells and macrophages plays an important role, since these pro-survival factors contribute to the replicative and migratory mesenchymal phenotype at an early stage of fibrosis.32–34 TGF-β1 is another important growth factor that contributes to collagen synthesis as well as establishing a matrix synthesis phenotype for the mesenchymal cellular elements.32–34

We have recently developed a quantitative dispersal technique that allows more directed property-activity analysis of the biological effects of MWCNTs.35 This included the demonstration that well-dispersed MWCNTs are more robust at inducing TGF-β1 production in epithelial cells as well as sustaining fibroblast proliferation in tissue culture experiments.35 These findings prompted us to consider whether the state of MWCNT dispersal exerts similar pro-fibrogenic effects in the murine lung. In this communication, we demonstrate significant differences between dispersed and non-dispersed, as-prepared and purified MWCNTs in providing a stimulus for TGF-β1 production in a bronchial epithelial cell line (BEAS-2B) as well as TGF-β1 and PDGF-AA production in lungs of mice receiving MWCNTs via oropharyngeal aspiration. Not only did the state of dispersal determine cellular bioavailability and uptake but also controlled the induction of pulmonary fibrosis in a dose-dependent manner. Better dispersed tubes also induced higher IL-1β production in a human myeloid cell line (THP-1). In contrast, carboxyl-functionalized MWCNTs, although well-dispersed, induced little or no pro-fibrogenic effects in epithelial cells and limited fibrosis in the murine lung. Taken together, these results indicate that the state of dispersal of MWCNTs plays an important role in pulmonary fibrosis by triggering cellular responses originating from the epithelial-mesenchymal trophic cell unit, a modular unit that can be used to explore and predict the fibrogenic effects of this class of nanomaterial in vivo.

RESULTS

MWCNT characterization

Cheap Tubes, Inc., supplied the raw or “as-prepared” (AP) MWCNTs, served as the precursor for preparing purified (PD) and carboxylated (COOH) derivatives as described in our previously study.35 AP-MWCNTs contained ~5.25 wt % metal impurities from catalysts, which included Ni (4.49 wt %) and Fe (0.76 wt %). These metal catalysts are used during MWCNT synthesis. PD-MWCNTs were obtained after purification, which was achieved using dilute acids, chelating agents and mild conditions that would not produce oxidized or damaged tubes as confirmed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. After purification, the metal impurities from the tubes decreased from 5.25 wt % to 1.88 wt %. Further acid treatment of the PD-MWCNTs introduced carboxyl groups on 5.27 % of the carbon backbone (on a per weight basis), which was identified by FTIR. Metal content was not detectable and sulfate was 0.18 wt%. The basic physicochemical characteristics of this library of MWCNTs are shown in Table 1 as well as Fig. S1A and Fig. S1B in Supporting Information. Additional details of the MWCNT characteristics appear in a previous publication.35

Table 1.

Physicochemical Characterization of the MWCNTs

| MWCNTs | Average length | Average diameter | Zeta potential | Residuals impurity | Ni | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP-MWCNT | 10~30 μm | 20~30 nm | −25.7mV | 5.25 % | 4.49% | 0.76 % |

| PD-MWCNT | 10~30 μm | 20~30 nm | −28.1mV | 1.88 % | 1.80 % | 0.08 % |

| COOH-MWCNT | 10~30 μm | 20~30 nm | −48.5mV | 0.18 % | nd | nd |

The average length and diameter of the tubes were measured and analyzed using a TEM microscopy (JEOL 100 CX transmission electron microscope). The zeta potential was measured using a ZetaSizer Nano-ZS (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire WR, UK). The elemental compositions of the MWCNTs were determined by Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS, Oxford Instrument, Oxfordshire, UK). The experiment details are described in the Materials and Methods. AP: as prepared; PD: purified; nd: non-detected.

MWCNT dispersal determines bioavailability and induction of TGF-β1 production in BEAS-2B cells

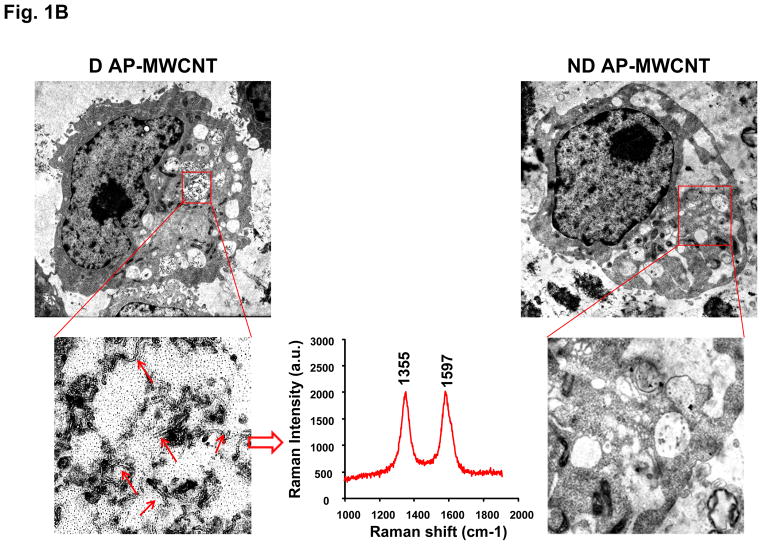

AP-, PD-, and COOH-MWCNTs were stably suspended in BEGM containing bovine serum albumin (BSA) and dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) as described in our previously study.35 Fig. S1C demonstrates that these dispersants act synergistically to provide good suspension stability, as determined by expressing the absorbance of the tubes remaining in suspension as a % of initial tube absorbance (t = 0) over a 20 hr observation period. For biological comparison, we also prepared a set of non-dispersed tubes in dispersant-free BEGM. Both the dispersed (D) and non-dispersed (ND) tubes were added to BEAS-2B cultures at 10–100 μg/mL and cultured for 24 hr, following which the culture supernatants were collected to measure TGF-β1 production. Compared to non-dispersed AP- and PD-MWCNTs, dispersed tubes induced significantly higher TGF-β1 production, particularly in cultures exposed to AP tubes (Fig. 1A). In contrast, COOH-MWCNTs were poor inducers of TGF-β1 production and did not show major differences between dispersed and non-dispersed tubes (Fig. 1A). In order to relate these differences to cellular bio-uptake, we used transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to look for intracellular tubes. Well-dispersed AP- and PD-MWCNTs could be observed in membrane-lined cellular vesicles (Fig. 1B and Fig. 2A) where the presence of the tubes were authenticated by characteristic MWCNT peaks at 1355 and 1597 nm, using a Confocal Raman microscope (Fig. 1B and Fig. S2A). In contrast, there was little cellular uptake of non-dispersed tubes. It was also difficult to visualize uptake of COOH-MWCNTs in either their dispersed or non-dispersed state in BEAS-2B cells (Fig. S2B). Lower magnification optical microscope images, coupled with confocal Raman analysis, help to further confirm differential bioavailability (Fig. 1C). Thus, while well-dispersed AP- and PD-MWCNTs were taken up abundantly, it was difficult to observe a Raman signature for COOH-MWCNTs in BEAS-2B cells (Fig. 1C). Together with the data on TGF-β1 production, these results indicate a good correlation between cellular bioavailability and triggering of the pro-fibrogenic response by dispersed vs non-dispersed tubes.

Figure 1. Comparison of the biological effects and uptake of dispersed (D) and non-dispersed (ND) MWCNTs in BEAS-2B cells.

(A) Cells were treated for 24 hr with the indicated concentrations of the AP, PD and COOH-MWCNTs, which were prepared in the presence or absence of BSA (0.6 mg/mL) plus DPPC (0.01 mg/mL) as dispesants. The supernatants were collected to measure the TGF-β1 levels by ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. No significant TGF-β1 production was seen with ND tubes, except at the highest COOH-MWCNT concentration. * denotes a p-value < 0.05, comparing control to CNT-exposed cells; # defines a p-value < 0.05, comparing D to ND tubes. (B) Representative TEM images to show the subcellular uptake of D vs ND tubes in cells treated with 50 μg/mL AP-MWCNTs for 24 hr. The red arrows point to tubes localized in membrane-lined vesicles. The MWCNT identity was confirmed by the Raman spectroscopy data obtained in a Renishaw inVia Raman microscope system. MWCNTs exhibit characteristic peaks at 1355 nm and 1597 nm as shown in the middle panel. Identical results were obtained for PD-MWCNTs (Fig. S2A). The right side panel shows that ND tubes are not taken up by the cells. (C) Confocal Raman analysis of BEAS-2B cells viewed under a light optic microscope to show quantitative differences in the uptake of well-dispersed AP, PD, and COOH-MWCNTs in BEGM over 24 hr. Raman microscopy was performed at different cellular planes (top, middle and bottom) to compare the signal intensities when the beam is focused above at or below the cellular localization level of the tubes.

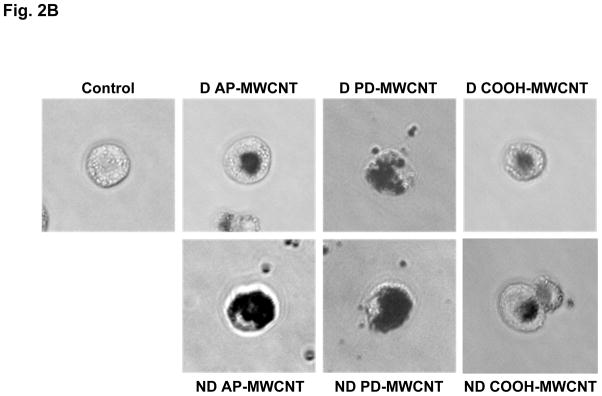

Figure 2. Comparison of the biological effects and uptake of dispersed (D) and non-dispersed (ND) MWCNTs in THP-1 cells.

(A) Cells were treated for 24 hr with the indicated concentrations of the different MWCNTs in their D and ND states as described above. The supernatants were collected to measure the IL-1β production by ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. The * and # symbols denote statistical significance at p < 0.05 as described in Fig. 1. (B) Representative light optical images looking at cellular uptake of dispersed and non-dispersed AP, PD and COOH-MWCNTs. THP-1 cells were treated with D and ND tubes for 24 hr and then observed by a phase contrast microscopy (Carl Zeiss, Inc. Peabody, MA, USA).

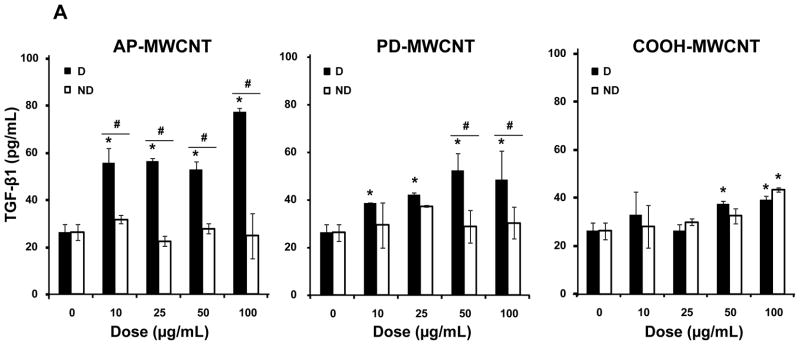

MWCNT dispersal affects IL-1β production in THP-1 cells

THP-1 is a human monomyelocytic leukemia cell line that, in response to PMA treatment, differentiates into a myeloid phenotype with phagocytic properties and the ability to initiate IL-1β production in response to long aspect ratio nanomaterials and asbestos fibers.28 We used THP-1 because this cell line has been utilized as a cellular model for studying inflammasome activation in response to hazardous environmental stimuli.28 Following exposure to similar doses of dispersed and non-dispersed tubes as in Fig. 1, THP-1 cells demonstrated a statistically significant augmentation of IL-1β production, with AP- and purified tubes showing more robust responses than COOH-MWCNTs (Fig. 2A). In contrast to epithelial cells, all tubes, irrespective of their state of dispersal, were taken up in THP-1 cells, albeit to a lesser degree in the case of COOH-MWCNTs (Fig. 2B).

Dose-dependent increase in TGF-β1 and PDGF-AA production in the lung in parallel with increased fibrosis in response to dispersed AP-MWCNTs

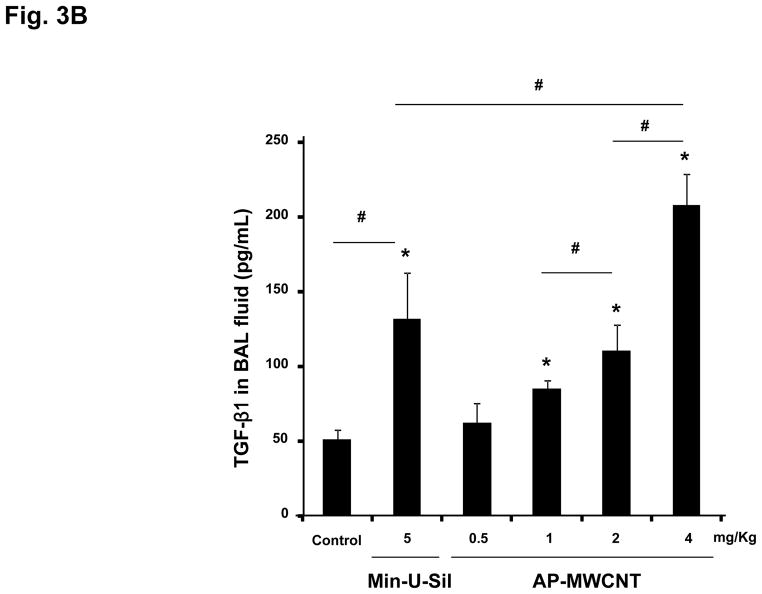

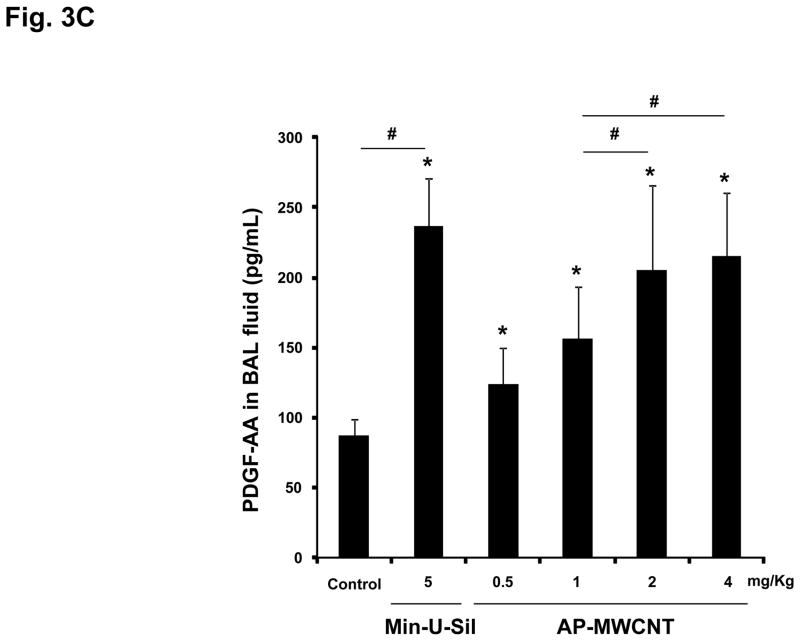

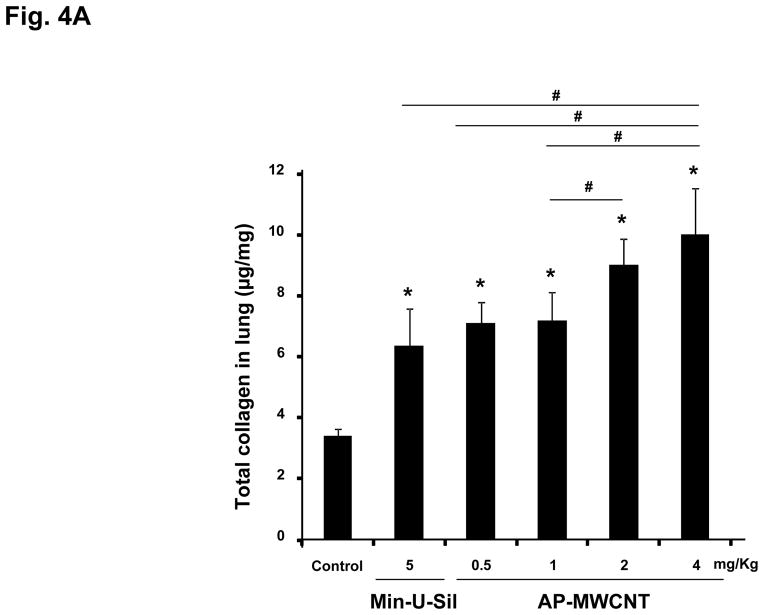

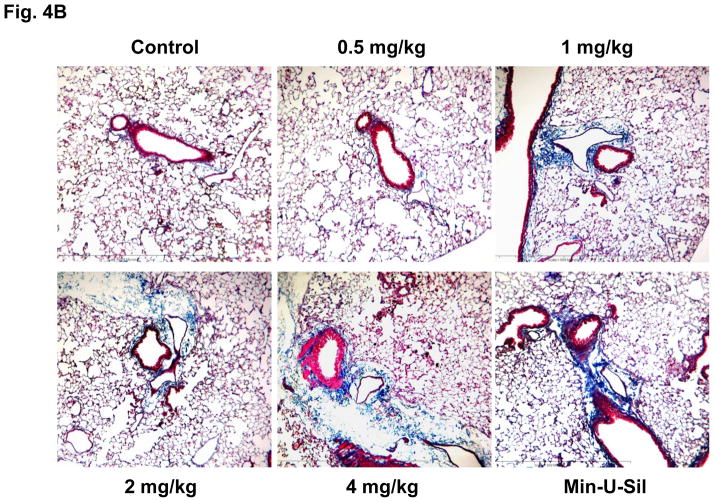

The assessment of pulmonary fibrosis is a valid platform for comparing pro-fibrotic effects at the cellular level with similar outcomes in the lung.18, 22, 26 First, we asked whether there is any correlation between the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid levels of the cytokines and growth factors discussed above and the extent of pulmonary fibrosis. We began with a dose-response study that included the use of dispersed AP-MWCNTs to determine an effective dose for performing the experiments. CB57BL/6 mice received a one-time oropharyngeal aspiration of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 mg/Kg AP-MWCNTs prepared by the addition of dispersants to PBS. The synergistic effect of BSA and DPPC in PBS was demonstrated by assessing the suspension stability index as described above for tissue culture experiments (Fig. 3A). Oropharyngeal aspiration of Min-U-Sil was used as positive control. Examination of the BAL fluid showed a dose-dependent increase in TGF-β1 (Fig. 3B) and PDGF-AA (Fig. 3C) production in response to well-dispersed MWCNT aspiration at 21 days post-exposure. These pro-fibrogenic biomarkers were accompanied by a dose-dependent increase in the collagen content in the lung, as determined by the Sircol collagen assay (Fig. 4A). Moreover, we visualized the sites of collagen deposition by Masson’s Trichrome staining, which demonstrated a dose-dependent increase of collagen content around small airways (Fig. 4B). Min-U-Sil also induced TGF-β1 and PDGF-AA production as well as a significant increase in collagen deposition (Figs. 3 and 4, Table 2). IL-1β production in the lung in response to SWCNTs is an early event (e.g. one day) and returns to normal by day 21.18, 32 IL-1β plays a role in the initiation of PDGF-AA production by epithelial cells as well as TGF-β1 production by macrophages at a later stage (days to weeks). Those growth factors act in synergy to induce fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition in lung.18, 32 Therefore we also measured IL-1β activity and found that although the MWCNTs did not result in increased IL-1β levels at 21 days in the BAL fluid compared to the control, we did observe increased in IL-1β levels at 24 hr in an independent experiment in which mice received 2 mg/Kg dispersed AP-MWNCTs (Fig. S3). This is consistent with previous findings.18 Min-U-Sil aspiration did result in increased IL-1β production at 21 days (not shown). While Min-U-Sil and MWCNTs induced a small but significant increase in macrophage counts in the BAL fluid, it was interesting to see that at the highest dose, MWCNTs were associated with small but significant increases in lymphocyte, neutrophil and eosinophil counts (Fig. S4). The latter finding is interesting from the perspective that the pro-fibrogenic myofibroblast phenotype is occasionally associated with a Th2 lymphocyte phenotype. In this regard, it has been demonstrated that IL-1β production promotes eosinophil recruitment to the lung and can augment PDGF-AA and TGF-β1 production in the context of the epithelial-mesenchymal trophic unit.32, 33 In summary, well-dispersed AP-MWCNTs induced a dose-dependent increase in profibrogenic growth factors in parallel with increased pulmonary collagen deposition. Based on this observation, we selected an oropharyngeal dose of 2 mg/Kg to perform a comparative analysis of the effects of the three tube types in their dispersed and non-dispersed states to see if there is any correlation of the in vivo to the in vitro pro-fibrogenic events.

Figure 3. Dose-dependent pulmonary affects of well-dispersed AP-MWCNTs in mice.

(A) Assessment of the suspension stability index of the different tube types after their addition at a concentration of 50 μg/mL in PBS, followed by sonication in the absence or presence of 0.6 mg/mL BSA, 0.01 mg/mL DPPC, or a combination of both. The stability index was determined by comparing the initial MWCNT absorbance at t = 0 to the absorbance at 1, 2, 3, and 20 hr. The absorbance measurements were carried out at a λ=550 nm in a SpectroMax M5e (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA) as described in Materials and Methods. (B and C) Anesthetized C57BL/6 mice were exposed one time to well-dispersed AP-MWCNTs at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 mg/kg by oropharyngeal aspiration. There were 6 animals per group. Animals were euthanized after 21 days and BAL fluid collected to determine TGF-β1 (B) and PDGF-AA levels (C). Six mice treated with Min-U-Sil at 5 mg/kg by oropharyngeal exposure served as positive control. TGF-β1 levels were determined by an Emax ImmunoAssay System (Promega, Madison, WI) while PDGF-AA levels were assessed by the Quantikine ELISA kit from R&D Company (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as described in Materials and Methods. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a plate reader (SpectroMax M5e, Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). The experiment was reproduced a second time. * p < 0.05 compared to control, # p < 0.05 for pair-wise comparisons as shown.

Figure 4. Dose-dependent increase in lung fibrosis, using the organs collected in Fig. 3.

(A) Total lung collagen content from the same animals as in Fig. 3, using a Sircol Collagen Assay. The experiment was reproduced a second time. * p < 0.05 compared with control, # p < 0.05 compared among different doses of well-dispersed AP-MWCNTs and Min-U-Sil (positive control). (B) Trichrome staining depicting collagen deposition in the lungs of representative animals treated with dispersed AP-MWCNTs. Lungs were embedded, sectioned and stained by the Masson’s Trichrome stain. The red color represents staining of muscle tissue while collagen is stained blue. Lungs from Min-U-Sil exposed animals served as positive control.

Table 2.

Morphometric measures of airway fibrosis in mice exposed to MWCNTs

| Treatment | Airway Intersect Score | Area/Perimeter Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 6.14 + 1.57 | 3.44 + 0.59 |

| Min-U-Sil | 20.25 + 1.70* | 11.61 + 1.93* |

| AP-MWCNT | D = 16.50 + 2.12*,# | D = 12.72 + 1.91*,# |

| ND = 13.00 + 1.86* | ND = 9.69 + 1.47* | |

| PD-MWCNT | D = 14.00 + 1.82* | D = 9.87 + 0.76* |

| ND = 13.67 + 3.44* | ND = 8.79 + 2.21* | |

| COOH-MWCNT | D = 9.75 + 2.06* | D = 7.23 + 2.19* |

| ND = 11.25 + 0.96* | ND = 7.31 + 2.47* |

Airway morphometry was performed using two independent methods: airway intersect scores and area/perimeter ratio. The experiment details are described in the Materials and Methods. AP: as prepared; PD: purified.

Significant difference compared to Control.

Significant difference between dispersed (D) and non-dispersed (ND).

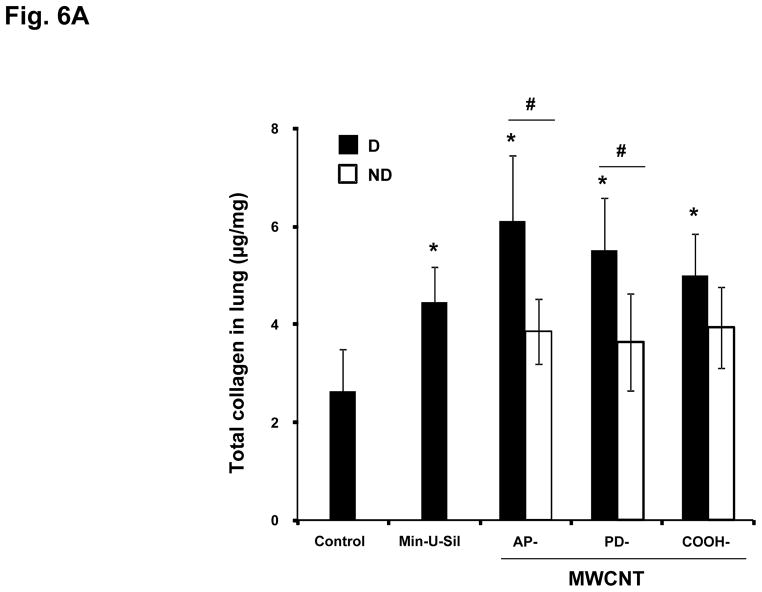

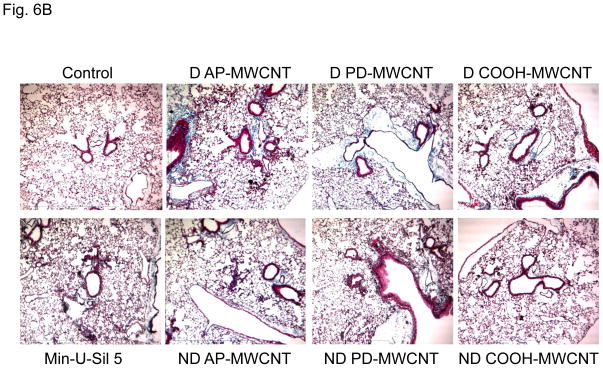

Well-dispersed MWCNTs elicit stronger pro-fibrogenic and collagen deposition effects than non-dispersed tubes

C57BL/6 mice received a one-time oropharyngeal aspiration of 2 mg/kg AP, PD and COOH-MWCNTs prepared in PBS with and without the use of dispersants. The animals were sacrificed on day 21, and TGF-β1 and PDGF-AA levels were measured in the BAL fluid as described above. While the well-dispersed tubes induced significantly higher levels of TGF-β1 and PDGF-AA than the non-dispersed, there were no significant differences between the tube types except that COOH-MWCNTs yielded non-significant lower values (Figs. 5A and 5B). When compared to the quantification of the collagen content in the lung, there was an identical trend in the data spread compared to the growth factor levels, with dispersed tubes resulting in more fibrosis (Fig. 6A). While, again, there was less increase in collagen content in response to COOH-MWCNTs, this was not statistically significant (Fig. 6A). However, in Trichrome-stained lung sections it was visually clear that dispersed AP- and PD-MWCNTs induced more prominent peribronchiolar and interstitial collagen deposition than COOH-MWCNTs (Fig. 6B). The observed increased in Trichrome-positive collagen staining around small airways was also quantified using two independent methods that assess airway collagen thickness.36, 37 Both methods showed a significant increase in airway fibrosis caused by MWCNT exposure and confirmed that dispersed AP-MWCNT caused significantly more airway collagen deposition compared to non-dispersed tubes (Table 2). Although there are no significant differences between dispersed and non-dispersed PD- and COOH-MWCNTs using morphometry analysis, this technique does not take into account the interstitial collagen deposition that is more extensive in the alveolar area for COOH-MWCNTs. In fact, high-resolution hematoxylin and eosin stained images from the same lung sections demonstrated that while dispersed APMWNCTs are more frequently localized in areas of granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 7), COOH-MWCNTs are predominantly localized in granuloma-free sites in the alveoli, with the majority of tubes engulfed by macrophages (Fig. 7). Confocal Raman microscopy showed characteristic MWCNT peaks, thus confirming the presence of tubes in these lung areas (see the spectrum A in the Raman insets in Fig. 7). PD-MWCNTs also localized at predominant sites of granulomatous inflammation (Fig. S5). High magnification Trichrome-stained lung images confirmed that collagen deposition for AP- and PD-MWCNTs took place in the setting of granulomatous inflammation, while COOH-MWCNTs stimulate collagen production mostly in the alveolar region (Fig. S6). Although not taken up by BEAS-2B cells (Fig. S2B), COOH-MWCNTs are engulfed up by alveolar macrophages and appear to be quite capable of promoting less but detectable amounts of collagen deposition in this locality. The engulfment of all MWCNT types by pulmonary macrophages was further confirmed by the examination of the BAL fluid (Fig. S7). Min-U Sil induced peptide growth factor production and collagen deposition in accordance with its known pro-fibrogenic effects (Figs. 5 and 6).

Figure 5. Comparison of the fibrotic effect of AP-, PD- and COOH-MWCNTs in their dispersed (D) as compared to their non-dispersed (ND) states.

This experiment was performed identical to the experiment in Fig. 3, using 6 mice in each group. Oropharyngeal aspiration of a dose of 2 mg/kg AP, PD and COOH-MWCNTs was performed using dispersed (BSA and DPPC) and non-dispersed (ND) tube preparations. 21 days after the one-time exposure, the animals were euthanized and BAL fluid collected to determine TGF-β1 levels (A) and PDGF-AA activity (B). The experiment was repeated once, * p < 0.05 compared to control, # p < 0.05 when comparing D to ND tubes. Mice treated with Min-U-Sil at 5 mg/kg by oropharyngeal exposure served as positive control.

Figure 6. Differential collagen deposition in the lungs of mice for the same experiment shown in Fig. 5.

(A) Total collagen content of the lung tissue was determined using the Sircol Soluble Collagen Assay kit (Biocolor Ltd., Carrickfergus, UK) as described in the Materials and Methods. * p < 0.05 compared with control, # p < 0.05 when comparing D to ND tubes. (B) Masson’s Trichrome staining to assess the tissue distribution of collagen in the lungs as described in Fig. 4. These lung images obtained at 100 × magnification are representative of the animals in each group. More prominent collagen deposition is seen in animals exposed to D vs ND tubes.

Figure 7. Confocal Raman analysis of the dispersed MWCNTs in the lung.

The lung sections were obtained from the same experiment as in Fig. 5 and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Lower (100 ×) and higher (400 ×) magnifications are shown of representative regions in the lungs of AP and COOH-MWCNT exposed animals. PD-MWCNTs had similar effects than AP-MWCNTs. The same lung sections were analyzed in a Renishaw inVia Raman microscope system. Two representative spots in each high magnification image were chosen for Raman scanning, namely a spot in an area of granulomatous inflammation for AP-MWCNTs and an alveolar impact site for COOH-MWCNTs. Arrow A is a representative cell not engulfing the MWCNTs, while arrow B denotes a representative cell that loaded with MWCNT. The right panel shows the corresponding Raman spectra identifying the specific peaks at 1355 nm and 1597 nm.

In an independent study undertaken in the laboratory of JB, the investigators performed a comparative analysis of the effects of dispersed AP, PD and COOH-MWNCNTs at days 1 and 21 on biomarker generation in relation to pulmonary fibrosis. This study was performed with oropharyngeal aspiration of 2 mg/Kg of tubes as described above and the results are depicted in the supplementary data section (Figs. S3, S8A and S8B). In brief, all tube types induced an increase in the BAL fluid levels of IL-1β on day 1 but not on day 21 (Fig. S3). Conversely, all tubes induced a significant increase of TGF-β1 levels on day 21 but not on day 1 (Fig. S8A), while for PDGF-AA the results were mixed with AP-MWCNTs inducing an increase on both days while PD-MWCNTs only induced a response at day 21 and COOH-MWCNTs no significant effect at either time point (Fig. S8B).

Taken together, the above data confirm the excellent correlation between the dispersal status of MWCNTs and their relationship to biochemical markers of fibrogenesis in the BAL fluid and collagen deposition in the lung. Moreover, the differences in IL-1β and peptide growth factor production of at different time periods are in accordance with the dynamic evolution of the cellular crosstalk events among the different cell types participating in the epithelial-mesenchymal cell trophic unit.

DISCUSSION

In this study we demonstrate that the state of dispersal of a small library of MWCNTs from the same precursor induced prominent pro-fibrogenic effects that reflect the cooperation of epithelial and mesenchymal cell elements in the generation of pulmonary fibrosis. The detectable biomarkers, including TGF-β1, PDGF-AA and IL-1β, act synergistically in the evolutionary period during which epithelial-myofibroblast transition contributes to collagen deposition in the lung. The effects of tube dispersal were most noticeable for as-prepared (AP) and purified (PD) MWCNTs, which are more hydrophobic and less stable in biological fluids than more hydrophilic COOH-MWCNTs. While carboxyl-functionalized tubes were poorly taken up in BEAS-2B cells and induced little or no TGF-β1 production in vitro, they were taken up by lung macrophages and could induce IL-1β and TGF-β1 production in vivo along with a discernible increase in collagen deposition around the alveoli. Instead, well-dispersed AP and PD-MWCNTs were taken up by BEAS-2B cells, THP-1 cells and alveolar macrophages and induced prominent TGF-β1 and PDGF-AA production in the lung in parallel with prominent granulomatous inflammation and fibrosis around small airways. Non-dispersed versions of the same materials induced significantly less TGF-β1 and PDGF-AA production in vivo along with reduced pulmonary fibrosis; this was in agreement with reduced IL-1β and TGF-β1 production in vitro. Taken together, these results indicate that the state of MWCNT dispersal influences pro-fibrogenic epithelial and macrophages responses that correlate with the extent and localization of pulmonary fibrosis. These findings are of considerable importance in developing a model that relates the biophysical-chemical properties of CNTs at the in vitro nano/bio interface to in vivo biological outcomes. This could lead to a facilitated method for the assessment of CNT safety.

While the state of dispersal of SWCNTs has been shown to impact the extent and localization of pulmonary fibrosis,18, 22, 31 this is the first demonstration that MWCNT dispersal determines the extent to which they initiate fibrogenic effects in epithelial cells and macrophages and where these cellular effects are directly predictive of the extent of pulmonary fibrosis in intact animals. This progress was made possible by the development of a quantitative dispersal technique that uses BSA and DPPC to obtain stable MWCNT suspensions to probe biological events at the nano/bio interface.31, 35, 38 In a previous study we have shown that the dispersal state of MWCNTs exerts prominent effects on fibroblast proliferation, and hypothesized that similar biological effects could help to explain disease pathogenesis in the intact lung.35 While the idea of an improved dispersal state allowing tube access to more distal lung regions is relatively straightforward, it is less clear how the state of dispersal affects bioavailability and triggering of injurious biological effects that result in disease outcome. In the latter instance, the scientific explanation is less obvious as illustrated by the response differences and variation in tube bio-processing by epithelial cells and macrophages. While it is possible with high resolution techniques such as electron microscopy to show the presence of occasional MWCNTs embedded in the membrane of bronchial or alveolar epithelial cells in vivo,26 we could not directly demonstrate in our histochemistry and Raman studies that there is a prominent epithelial uptake in the intact lung. We did observe clear differences, however, between the ability of dispersed and non-dispersed tubes to induce TGF-β1 production in BEAS-2B cells as well as in the experiments looking at IL-1β production in THP-1 cells (Figs. 1A and 2A). The same was true when doing a related comparison of the effects of dispersed vs non-dispersed tubes on growth production in the lung (Fig. 5). Thus, while tube dispersal affects cellular uptake, the precise explanation for the triggering of pro-fibrogenic responses remains obscure. One possibility is that coating of the tube surfaces with BSA and DPPC establishes surface ligands that promote cellular contact and/or uptake.11 It is interesting that SWCNT dispersal by Pluronic F108 leads to good tube dispersal and widespread dissemination throughout the lung.39 However, under these experimental conditions the well-dispersed tubes can be cleared from the lung without fibrosis, while non-dispersed tubes are retained and induce granulomatous inflammation.39 It is possible, therefore, that coating of CNTs by the block copolymer introduces steric hindrance that interferes in cellular uptake, compared to coating with BSA and DPPC that promotes cellular bio-processing and uptake.39 However, these results do not fully explain why carboxylation of the MWCNT surface leads to less cellular and pulmonary effects when coated with BSA and DPPC. While it is known that the aspect ratio, length and rigidity of MWCNTs play a role in frustrated phagocytosis and the generation of chronic granulomatous inflammation,8, 23, 40, 41 we did not observe the classical features of frustrated phagocytosis in our study. Instead, we observed that IL-1β production in THP-1 cells is affected by the state of tube dispersal. Since it is known that the release of this cytokine from myeloid cells and macrophages is dependent on the cleavage of pre-IL-1β by the NALP 3 inflammasome,28 it is possible that MWCNT dispersal may affect the assembly of inflammasome components through an pathway that includes phagosome or lysosome injury. This aspect is currently under investigation but will require expansion of the CNT properties in our library, including the addition of different tube lengths to perform more detailed property-activity analysis. Being able to pinpoint the exact mechanism of CNT injury in relation to specific tube properties is of key importance for the development of CNT-based therapeutics and imaging agents.

This communication is of considerable importance to the development of in vitro assessment tools for hazard assessment and planning of the in vivo toxicological testing of CNTs. Several toxicology studies in rodents have been carried out by using intratracheal instillation, oropharyngeal aspiration, or inhalation of SWCNTs and MWCNTs.6, 15, 17, 18, 21, 22 Collectively, these studies have shown a consistent toxicological outcome in terms of pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis, irrespective of the exposure route. The same studies have also demonstrated that some CNT formulations induce more rapid pulmonary fibrosis or at a lower mass burden than either ultrafine carbon black or quartz.6, 16, 18 Thus, it is important to develop toxicological assays that can differentiate between the variety of CNT formulations being employed in electronics, solar cells, super capacitors, reinforced plastics, composite materials, aircraft components, biosensors, and pharmaceutical/biomedical devices. As these products make their way to the marketplace, it is important to have test strategies for in vitro and in vivo hazard assessment. Since the cost of animal studies is high and raises ethical barriers, alternative test strategies are an important consideration. The use of a set of biochemical markers that closely reflect the synergy between macrophages and cellular elements in the epithelial-mesenchymal trophic unit could constitute a screening platform for the rapid and high content data generation that facilitates a predictive toxicological approach.42 Predictive screening platforms could facilitate decision-making about CNT pulmonary hazard and could evolve, over time, into an independent test platform depending on the stringency of the safety analysis that is accepted by the regulatory community.42–44 Another advantage of a predictive toxicological platform is the potential to develop high throughput screening approaches that can assist in the establishment of quantitative structure-activity relationships and the safe design of CNTs for biomedical use. In this regard, we have already demonstrated that high throughput screening is useful for the assessment of metal and metal oxide nanoparticle toxicity, including the development of safer ZnO nanoparticles.42, 44 Thus, our future efforts will concentrate on developing a high throughput system that utilizes cellular elements in the epithelial-mesenchymal trophic unit to develop a multiparametric assay to look at synergistic cytokine/growth factor responses. We will compare the use of such an assay to similar biomarkers in BAL fluid and the assessment of pulmonary fibrosis to develop a robust, predictive assessment tool. However, until such testing is available, all possible steps should be taken to minimize CNT exposures in workers.

In order to evaluate the relevance of the in vivo findings in mice to human MWCNT exposures, it is interesting to perform an extrapolation of the doses used in mice to possible occupational exposures in human. The MWCNTs doses of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 mg/kg used in our experiment equals 12.5, 25, 50 and 100 μg per mouse as addressed in the Methods section. Han et al. reported peak MWCNT-containing airborne dust levels being as high as 400 μg/m3 in a MWCNT production laboratory.44 Based on this finding, Porter et al. calculated that a worker exposed to MWCNT for 8 hr/day over a month at 400 μg/m3 would carry a lung burden equivalent to a mouse receiving 10 μg MWCNT by aspiration.20 Therefore, in a worse case scenario, lung burdens of 12.5–100 μg per mouse lung (alveolar surface area, 0.05 m2 per animal) is equal to a human lung (102 m2 alveolar surface area) burden that can be acquired following 1.25 to 10 months of exposure.45 Assuming a 10 fold lower exposure level (40 μg/m3), mouse lung burdens will be equivalent to 1–10 years of exposure in human in a contaminated work place. Thus, these estimates suggest that the MWCNT doses tested in mice in this study approaches realistic occupational exposures in humans.

The dose-response relationships leading to the generation of pulmonary fibrosis in rodents has served as the scientific basis for the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) draft recommending an exposure limit (REL) of 7 μg/m3 in CNT exposure environments.47 This draft’s recommended exposure limit was developed based on available acute and subchronic animal exposure studies linking early stage fibrosis and inflammatory responses in the lung to CNT dose. Benchmark dose (BMD) estimates were calculated by using species differences in alveolar lung surface area, which has been estimated to be 0.05 and 102 m2 in the mouse and human lung, respectively.46 Therefore, exposure to 50 μg CNTs would normalize to a surface area dose of 0.1 μg/cm2 in the murine lung; this is equivalent to a human lung burden of 102 mg. The REL of 7 μg/m3 was calculated based on the expected retained alveolar dose in workers being exposed 8 hr per day, 40-hr per week, 50 weeks per year and over a 45 year working lifetime. Please notice that although the draft REL is set at the lowest airborne CNT concentration that can be accurately measured by NIOSH methodology, an excess risk of adverse lung effects is still possible below this level and efforts should be made to reduce airborne concentrations of CNTs as low as possible.

Extrapolation of in vitro to in vivo dosimetry remains a daunting challenge in ENM toxicology, but can be initially approached by normalizing the MWCNT surface area dose in the tissue culture dish to the normalized surface area dose in the rodent airways. Assuming that the entire MWCNT dose of 10–100 μg/ml in the tissue culture dish is bio-available, this translates to an in vitro surface area dose of 3.1–31.2 μg/cm2. If we assume that the same exposure dose is evenly deposited in the lung, this would constitute an alveolar surface area exposure of 0.025–0.2 μg/cm2, providing a departure point for reconciling in vitro and in vivo dose calculations. To allow such comparisons, this will require the calculation of bio-available cellular and tissue dose, necessitating some type of tube labeling to perform those estimates. Moreover, we have to consider that the in vitro exposure takes place over a 24 hr time period compared to in vivo exposure being performed over 21 days. Thus, we also need to assess the fraction of tubes that are retained in the lung vs those that are cleared. Finally, it is appropriate to consider whether a mass-based dosimetry system is appropriate or should be supplemented by dosimetry calculation that takes into consideration the toxicological mechanism by developing quantitative property-activity relationships.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Carbon nanotubes and chemicals

A powdered MWCNT stock was purchased from Cheap Tubes Inc. (Brattleboro, VT, USA). The starting raw material is also being referred to as as-prepared (AP) MWCNTs. Bronchial epithelial growth medium (BEGM) was obtained from Lonza (Mapleton, IL, USA), which is supplemented with a number of growth factors, including bovine pituitary extract (BPE), insulin, hydrocortisone, hEGF, epinephrine, triiodothyronine, transferrin, gentamicin/amphotericin-B and retinoic acid. Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium 1640 (RPMI 1640) was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Low-endotoxin bovine serum albumin (BSA) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were from Gemini Bio-Products (West Sacramento, CA, USA). Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Min-U-Sil was obtained from U.S. Silica (Frederick, MD, USA). All MWCNT stock solutions were prepared using pure deionized water (DI H2O) with resistivity >18 Ω-cm.

Physicochemical characterization of MWCNTs

The purification and functionalization of the MWCNTs were accomplished as previously described.35, 48–50 A number of techniques were used to characterize MWCNTs, including Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS, Oxford Instrument, Oxfordshire, UK) to identify the elemental composition of the tubes. Zeta-potential measurements of the tube suspensions were performed using a ZetaSizer Nano-ZS Instrument (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire WR, UK). The average length and diameter of the tubes were measured under a TEM microscopy (JEOL 100 CX transmission electron microscope).

Preparation of MWCNT suspensions in media

AP, PD and COOH-MWCNTs were provided as dry powders. The samples were weighed in the fume hood on an analytical balance and suspended in distilled, deionized H2O at a concentration of 5 mg/mL in 4 mL glass vials. These suspensions were sonicated for 15 min in a water sonicator bath (Branson, Danbury, CT, USA, Model 2510, 100 W output power; 42 kHz frequency) and used as the stock solution for further dispersion in cell culture media or PBS. A sonicator bath rather than a sonication probe was used to deliver a cavitation force suitable for de-agglomeration but not too high to disrupt protein attachment or induce tube damage.9, 51, 52 An appropriate amount of each stock solution was added to the desired final concentration in cell culture media or PBS. BSA and DPPC were added to the culture media or PBS at 0.6 mg/mL and 0.01 mg/mL, respectively, before the addition of the MWCNTs. The diluted tube suspensions were vortexed for 15 s (fixed-speed vortex, 02-215-360, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), sonicated for 15 min, and then vortexed for another 15 s to obtain well-dispersed tube suspensions at the desired final concentrations. The non-dispersed tubes were similarly processed in the absence of dispersants.

Cellular culture and co-incubation with MWCNTs

BEAS-2B and THP-1 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). BEAS-2B cells were cultured in BEGM at 5 % CO2 and 37 °C. Before MWCNT exposure, aliquots of 1×104 cells were cultured in 0.2 mL BEGM in 96-well plates (Costar, Corning, NY) at 37 °C overnight. All the MWCNT solutions were freshly prepared at final concentrations of 10, 25, 50 and 100 μg/mL in BEGM. While non-dispersed MWCNTs were sonicated in BEGM devoid of dispersants, well-dispersed MWCNTs were prepared by sonication in BEGM containing 0.6 mg/ mL BSA plus 0.01 mg/mL DPPC before addition to the tissue culture plates. THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum. Before MWCNT exposure, THP-1 cells were pretreated with 1 μg/mL phorbol 12-myristate acetate (PMA) for 18 hr and primed with 10 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to initiate transcription of the IL-1β precursor. Aliquots of 1.5×104 primed cells were seeded in 0.2 mL complete medium in 96-well plates (Costar, Corning, NY, USA). For preparing the tube suspension, MWCNTs were added to complete RPMI 1640 at final concentrations of 10, 25, 50 and 100 μg/mL. The suspensions were treated with dispersants and sonicated in the absence of dispersants as described above. Following exposure to the tubes for 24 hr at 37 °C, the supernatants were collected and used to measure TGF-β1 and IL-1β production..

Cellular transmission electron microscopy

BEAS-2B cells were exposed to 50 μg/mL well-dispersed or poorly dispersed MWCNTs suspended in BEGM for 24 hr. Harvested cells were fixed with 2 % glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and washed.53 After post-fixation in 1 % OsO4 in PBS for 1 hr, the cells were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, treated with propylene oxide, and embedded in Epon. Approximately 50–70 nm thick sections were cut on a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E ultramicrotome and picked up on Formvar-coated copper grids. The sections were stained with uranyl acetate and Reynolds lead citrate and examined on a JEOL 100 CX transmission electron microscope at 80 kV in the UCLA BRI Electron Microscopy Core.

Mouse exposure and assessment of exposure outcomes in mice

Eight-week-old male C57Bl/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Hollister, CA). All animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions that have been set up according to UCLA guidelines for care and treatment of laboratory animals as well as the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in Research (DHEW78-23). These conditions are approved by the Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee at UCLA and include standard operating procedures for animal housing (filter-topped cages; room temperature at 23 ± 2 °C; 60% relative humidity; 12 h light, 12 h dark cycle) and hygiene status (autoclaved food and acidified water). Animal exposures to well-dispersed or non-dispersed tubes were carried out by an oropharyngeal aspiration method as described at NIOSH.17 Briefly, the animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg)/xylazine (10 mg/kg) in a total volume of 100 μL. With the anesthetized animals held in a vertical position, a 50 μl PBS suspension containing 12.5–100 μg AP-MWCNTs was instilled at the back of the tongue to allow pulmonary aspiration. In a further experiment all tube types, either in their dispersed or non-dispersed states, were oropharyngeally administrated as a single bolus dose of 50 μg. Each experiment included control animals receiving the same volume of PBS with BSA (0.6 mg/mL) and DPPC (0.01 mg/mL). The positive control group in each experiment received 5 mg/kg crystalline silica in the form of quartz particles (Min-U-Sil). The mice were sacrificed 21 days later and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and lung tissue collected as previously described.54 The BALF was used for performance of total and differential cell counts and to measure TGF-β1 and PDGF-AA levels. Lung tissue was stained with hematoxylin/eosin or with Masson’s Trichrome stain. Lung tissues were homogenenized with a Tissuemiser homogenizer (Fisher Scientific) for the assessment of total collagen production (Sircol Collagen Assay, UK).16, 39

Sircol assay for total collagen production

The right cranial lobe of each lung was suspended in PBS at around 50 mg tissue per ml and homogenized for 60 seconds with a tissue homogenizer (Fisher Scientific). Triton X-100 was added to 1 % and the samples incubated for 18 hr at room temperature. Acetic acid was added to each sample to a final concentration of 0.5 M and incubated at room temperature for 90 minutes. Cellular debris was pelleted by centrifugation and the supernatant analyzed for total protein, using a BCA Assay kit (Pierce/ThermoFisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The Sircol Soluble Collagen Assay kit (Biocolor Ltd., Carrickfergus, UK) was used to extract collagen from duplicate samples using 200 μl of supernatant and 800 μl Sircol Dye Reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Similar prepared collagen standards (10–50 μg) were run in parallel. Collagen pellets were washed twice with denatured alcohol and dried before suspension in alkali reagent. Absorbance at 540 nm was read on a plate reader (SpectroMax M5e, Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Data were expressed as μg of soluble collagen per mg of total protein.

Airway Morphometry

Quantification of the thickness of collagen surrounding airways was performed according to a previously published airway intersect method.26, 36 Briefly, photomicrographs of Trichrome-stained sections of lung tissue containing circular to oval-shaped small or medium-sized airways were captured using a 10 × objective on an Olympus BX41 microscope (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA) and digitized. The thickness of the collagen layer surrounding the airways was measured using the ruler tool in Adobe photoshop CS3 extended program (Adobe Systems, InC., San Jose, CA) at eight equidistant points and averaged. To validate the airway intersect measurements, a second independent method similar to a previously published method was used to measure the airway collagen area corrected for length of basement membrane (i.e., area/perimeter ratio).37 Briefly, the lasso tool in Adobe photoshop was used to surround the Trichrome-positive collagen around an airway (outer area), then a second area measurement was made by surrounding the basement membrane of the same airway (inner area). Also, the length of the airway circumference (i.e., perimeter) was also derived from this measurement. The difference between outer and inner area was defined as the ‘area’ and divided by the ‘perimeter’ to derive area/perimeter measurements. Both methods were performed in a blinded manner, where the treatment group was unknown to the observer scoring the sections. Five airways per animal were analyzed in a random, blinded manner, and the data were expressed as the mean 6 SEM of five animals per treatment group per time point.

ELISA for TGF-β1 and PDGF-AA quantification

The TGF-β1 concentration in the BEAS-2B culture medium and the BALF was determined through the Emax ® ImmunoAssay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. A 96-well plate was coated with monoclonal anti-TGF-β1 and the captured growth factor detected by polyclonal anti-TGF-β1 conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a plate reader (SpectroMax M5e, Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). PDGF-AA activity in the BALF was assessed by the Quantikine ELISA kit from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The supplied standard growth factor dilution series or 50 μL of BALF were pipetted into the anti-PDGF-AA pre-coated wells for antigen capture. After removal of the unbound growth factor by washing, an enzyme-linked anti-PDGF-AA monoclonal was added. Following washing to remove unbound secondary antibody, a substrate solution was added at 1:250 dilution for 30 minutes for color development. After termination of the color development, colometric intensity was measured at 450 nm in a plate reader (SpectroMax M5e, Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The IL-1β activity in the THP-1 culture supernatant and the BALF was determined by an OptEIA™ (BD Biosciences, CA) ELISA kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, a 96-well plate was coated with monoclonal anti-IL-1β and the immobilized growth factor detected by polyclonal anti-IL-1β conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a plate reader (SpectroMax M5e, Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). TGF-β1, PDGF-AA and IL-1β concentrations were expressed as pg/mL.

Confocal Raman microscopy in cells and lung sections

Raman analysis was performed using backscattering geometry in a confocal configuration at room temperature in a Renishaw inVia Raman microscope system equipped with a 514.5 nm Ar laser. Laser power and beam size were approximately 2.5 mW and 1 μm, respectively, while the integration time was adjusted to 15 s. For cell sample preparation, BEAS-2B cells were cultured on sterile glass cover slips over night and then exposed to well-dispersed AP, PD, and COOH-MWCNTs in BEGM (containing BSA and DPPC) for 24 hr. Cells were washed three times in PBS and fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min. The cells were scanned under the Raman microscope following three further washes in PBS. For lung tissue scanning, the lungs were fixed in paraffin, sectioned and mounted onto glass slides without staining. The slides were de-waxed, hydrated, and then scanned under the Confocal Raman microscope.

Statistical Analysis

Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for each parameter. Results were expressed as mean ± SD of multiple determinations. Comparisons of each group were evaluated by two-side Student’s t-test. A statistically significant difference was assumed to exist when p was < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the US Public Health Service Grants (RC2 ES018766, RO1 ES016746, and U19 ES019528). Infrastructure support was also provided by National Science Foundation and the Environmental Protection Agency under Cooperative Agreement Number, EF 0830117. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the Environmental Protection Agency. This work has not been subjected to an EPA peer and policy review. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Baughman RH, Zakhidov AA, de Heer WA. Carbon Nanotubes - the Route Toward Applications. Science. 2002;297:787–792. doi: 10.1126/science.1060928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iijima S. Helical Microtubules of Graphitic Carbon. Nature. 1991;354:56–58. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nel A, Xia T, Madler L, Li N. Toxic Potential of Materials at the Nanolevel. Science. 2006;311:622–627. doi: 10.1126/science.1114397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kostarelos K, Bianco A, Prato M. Promises, Facts and Challenges for Carbon Nanotubes in Imaging and Therapeutics. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:627–633. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin Y, Taylor S, Li HP, Fernando KAS, Qu LW, Wang W, Gu LR, Zhou B, Sun YP. Advances Toward Bioapplications of Carbon Nanotubes. J Mater Chem. 2004;14:527–541. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam CW, James JT, McCluskey R, Hunter RL. Pulmonary Toxicity of Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Mice 7 and 90 Days After Intratracheal Instillation. Toxicol Sci. 2004;77:126–134. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JH, Lee SB, Bae GN, Jeon KS, Yoon JU, Ji JH, Sung JH, Lee BG, Lee JH, Yang JS, et al. Exposure Assessment of Carbon Nanotube Manufacturing Workplaces. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:369–381. doi: 10.3109/08958370903367359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller J, Huaux F, Fonseca A, Nagy JB, Moreau N, Delos M, Raymundo-Pinero E, Beguin F, Kirsch-Volders M, Fenoglio I, et al. Structural Defects Play a Major Role in The Acute Lung Toxicity of Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes: Toxicological Aspects. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:1698–1705. doi: 10.1021/tx800101p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberdorster G, Maynard A, Donaldson K, Castranova V, Fitzpatrick J, Ausman K, Carter J, Karn B, Kreyling W, Lai DN, Warheit D, Yang H, et al. Principles for Characterizing The Potential Human Health Effects From Exposure to Nanomaterials: Elements of A Screening Strategy. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2005;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warheit DB, Laurence BR, Reed KL, Roach DH, Reynolds GAM, Webb TR. Comparative Pulmonary Toxicity Assessment of Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Rats. Toxicol Sci. 2004;77:117–125. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao N, Zhang Q, Mu Q, Bai Y, Li L, Zhou H, Butch ER, Powell TB, Snyder SE, Jiang G, et al. Steering Carbon Nanotubes to Scavenger Receptor Recognition by Nanotube Surface Chemistry Modification Partially Alleviates NFkappaB Activation and Reduces Its Immunotoxicity. ACS Nano. 2011;5:4581–4591. doi: 10.1021/nn200283g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, Tabakman S, Welsher K, Dai HJ. Carbon Nanotubes in Biology and Medicine: In vitro and in vivo Detection, Imaging and Drug Delivery. Nano Res. 2009;2:85–120. doi: 10.1007/s12274-009-9009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maynard AD, Baron PA, Foley M, Shvedova AA, Kisin ER, Castranova V. Exposure to carbon nanotube material: Aerosol Release During the Handling of Unrefined Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Material. J Toxicol Environ Health-Part A. 2004;67:87–107. doi: 10.1080/15287390490253688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mercer RR, Hubbs AF, Scabilloni JF, Wang LY, Battelli LA, Schwegler-Berry D, Castranova V, Porter DW. Distribution and Persistence of Pleural Penetrations by Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7 doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller J, Huaux F, Moreau N, Misson P, Heilier JF, Delos M, Arras M, Fonseca A, Nagy JB, Lison D. Respiratory Toxicity of Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;207:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryman-Rasmussen JP, Cesta MF, Brody AR, Shipley-Phillips JK, Everitt JI, Tewksbury EW, Moss OR, Wong BA, Dodd DE, Andersen ME, et al. Inhaled Carbon Nanotubes Reach the Subpleural Tissue in Mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:747–751. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shvedova AA, Kisin E, Murray AR, Johnson VJ, Gorelik O, Arepalli S, Hubbs AF, Mercer RR, Keohavong P, Sussman N, et al. Inhalation vs. Aspiration of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in C57BL/6 Mice: Inflammation, Fibrosis, Oxidative Stress, and Mutagenesis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L552–L565. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90287.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shvedova AA, Kisin ER, Mercer R, Murray AR, Johnson VJ, Potapovich AI, Tyurina YY, Gorelik O, Arepalli S, Schwegler-Berry D, et al. Unusual Inflammatory and Fibrogenic Pulmonary Responses To Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes In Mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L698–L708. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00084.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pauluhn J. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (Baytubes (R)): Approach for Derivation of Occupational Exposure Limit. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2010;57:78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porter DW, Hubbs AF, Mercer RR, Wu NQ, Wolfarth MG, Sriram K, Leonard S, Battelli L, Schwegler-Berry D, Friend S, et al. Mouse Pulmonary Dose- and Time Course-Responses Induced by Exposure to Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Toxicology. 2010;269:136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng X, Jia G, Wang H, Sun H, Wang X, Yang S, Wang T, Liu Y. Translocation and Fate of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes In Vivo. Carbon. 2007;45:1419–1424. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercer RR, Scabilloni J, Wang L, Kisin E, Murray AR, Schwegler-Berry D, Shvedova AA, Castranova V. Alteration of Deposition Pattern and Pulmonary Response as A Result of Improved Dispersion of Aspirated Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in A Mouse Model. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L87–L97. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00186.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia G, Wang HF, Yan L, Wang X, Pei RJ, Yan T, Zhao YL, Guo XB. Cytotoxicity of Carbon Nanomaterials: Single-Wall Nanotube, Multi-Wall Nanotube, and Fullerene. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:1378–1383. doi: 10.1021/es048729l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nel AE, Madler L, Velegol D, Xia T, Hoek EMV, Somasundaran P, Klaessig F, Castranova V, Thompson M. Understanding Biophysicochemical Interactions at the Nano-Bio Interface. Nat Mater. 2009;8:543–557. doi: 10.1038/nmat2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poland CA, Duffin R, Kinloch I, Maynard A, Wallace WAH, Seaton A, Stone V, Brown S, MacNee W, Donaldson K. Carbon Nanotubes Introduced into the Abdominal Cavity of Mice Show Asbestos-Like Pathogenicity in a Pilot Study. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:423–428. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryman-Rasmussen JP, Tewksbury EW, Moss OR, Cesta MF, Wong BA, Bonner JC. Inhaled Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Potentiate Airway Fibrosis in Murine Allergic Asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:349–358. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0276OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donaldson K, Murphy FA, Duffin R, Poland CA. Asbestos, Carbon Nanotubes and the Pleural Mesothelium: A Review of The Hypothesis Regarding the Role of Long Fibre Retention In The Parietal Pleura, Inflammation and Mesothelioma. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7 doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tschopp J, Dostert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT. Innate Immune Activation through Nalp3 Inflammasome Sensing of Asbestos and Silica. Science. 2008;320:674–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1156995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tschopp J, Schroder K. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation: the Convergence of Multiple Signalling Pathways on ROS Production? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:210–215. doi: 10.1038/nri2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tschopp J, Schroder K, Zhou RB. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: A Sensor for Metabolic Danger? Science. 2010;327:296–300. doi: 10.1126/science.1184003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang LY, Castranova V, Mishra A, Chen B, Mercer RR, Schwegler-Berry D, Rojanasakul Y. Dispersion of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes by a Natural Lung Surfactant For Pulmonary in vitro and in vivo Toxicity Studies. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7 doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonner JC. Mesenchymal Cell Survival in Airway and Interstitial Pulmonary Fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2010;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonner JC. Regulation of PDGF and Its Receptors in Fibrotic Diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:255–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chapman HA. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Interactions in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;73:413–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Xia T, Ntim SA, Ji ZX, George S, Meng H, Zhang HY, Castranova V, Mitra S, Nel AE. Quantitative Techniques for Assessing and Controlling the Dispersion and Biological Effects of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes in Mammalian Tissue Culture Cells. Acs Nano. 2010;4:7241–7252. doi: 10.1021/nn102112b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Card JW, Voltz JW, Carey MA, Bradbury JA, Degraff LM, Lih FB, Bonner JC, Morgan DL, Flake GP, Zeldin DC. Cyclooxygenase-2 Deficiency Exacerbates Bleomycin-Induced Lung Dysfunction But Not Fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:300–308. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0057OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brass DM, Savov JD, Gavett SH, Haykal-Coates N, Schwartz DA. Subchronic Endotoxin Inhalation Causes Persistent Airway Disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L755–L761. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00001.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L, Mercer RR, Rojanasakul Y, Qiu A, Lu Y, Scabilloni JF, Wu N, Castranova V. Direct Fibrogenic Effects of Dispersed Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on Human Lung Fibroblasts. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2010;73:410–422. doi: 10.1080/15287390903486550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mutlu GM, Budinger GRS, Green AA, Urich D, Soberanes S, Chiarella SE, Alheid GF, McCrimmon DR, Szleifer I, Hersam MC. Biocompatible Nanoscale Dispersion of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Minimizes in vivo Pulmonary Toxicity. Nano Lett. 2010;10:1664–1670. doi: 10.1021/nl9042483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X, Jia G, Wang H, Nie H, Yan L, Deng XY, Wang S. Diameter Effects on Cytotoxicity of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2009;9:3025–3033. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2009.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, Zang JJ, Wang H, Nie H, Wang TC, Deng XY, Gu YQ, Liu ZH, Jia G. Pulmonary Toxicity in Mice Exposed to Low and Medium Doses of Water-Soluble Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2010;10:8516–8526. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2010.2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia T, Zhao Y, Sager T, George S, Pokhrel S, Li N, Schoenfeld D, Meng H, Lin SJ, Wang X, et al. Decreased Dissolution of ZnO by Iron Doping Yields Nanoparticles with Reduced Toxicity in the Rodent Lung and Zebrafish Embryos. Acs Nano. 2011;5:1223–1235. doi: 10.1021/nn1028482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meng H, Xia T, George S, Nel AE. A Predictive Toxicological Paradigm for the Safety Assessment of Nanomaterials. Acs Nano. 2009;3:1620–1627. doi: 10.1021/nn9005973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.George S, Pokhrel S, Xia T, Gilbert B, Ji ZX, Schowalter M, Rosenauer A, Damoiseaux R, Bradley KA, Madler L, et al. Use of a Rapid Cytotoxicity Screening Approach To Engineer a Safer Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle through Iron Doping. Acs Nano. 2010;4:15–29. doi: 10.1021/nn901503q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han JH, Lee EJ, Lee JH, So KP, Lee YH, Bae GN, Lee SB, Ji JH, Cho MH, Yu IJ. Monitoring Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube Exposure in Carbon Nanotube Research Facility. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20:741–749. doi: 10.1080/08958370801942238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stone KC, Mercer RR, Gehr P, Stockstill B, Crapo JD. Allometric Relationships of Cell Numbers and Size in the Mammalian Lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;6:235–243. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.NIOSH Current Intelligence Bulletin. Occupational Exposure to Carbon Nanotubes. 2011 www.cdc.gov/niosh/docket/review/docket161A/

- 48.Wang Y, Iqbal Z, Mitra S. Rapid, Low Temperature Microwave Synthesis of Novel Carbon Nano Tube-Silicon Carbide Composite. Carbon. 2006;44:2804–2808. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang YB, Iqbal Z, Mitra S. Microwave-induced Rapid Chemical Functionalization of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon. 2005;43:1015–1020. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang YB, Iqbal Z, Mitra S. Rapidly Functionalized, Water-Dispersed Carbon Nanotubes at High Concentration. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:95–99. doi: 10.1021/ja053003q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deguchi S, Yamazaki T, Mukai S, Usami R, Horikoshi K. Stabilization of C-60 Nanoparticles by Protein Adsorption and Its Implications For Toxicity Studies. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:854–858. doi: 10.1021/tx6003198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thess A, Lee R, Nikolaev P, Dai HJ, Petit P, Robert J, Xu CH, Lee YH, Kim SG, Rinzler AG, et al. Crystalline Ropes of Metallic Carbon Nanotubes. Science. 1996;273:483–487. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xia T, Kovochich M, Liong M, Zink JI, Nel AE. Cationic Polystyrene Nanosphere Toxicity Depends on Cell-Specific Endocytic and Mitochondrial Injury Pathways. Acs Nano. 2008;2:85–96. doi: 10.1021/nn700256c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li N, Wang MY, Bramble LA, Schmitz DA, Schauer JJ, Sioutas C, Harkema JR, Nel AE. The Adjuvant Effect of Ambient Particulate Matter Is Closely Reflected by the Particulate Oxidant Potential. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:1116–1123. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.