Abstract

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for social anxiety disorder (SAD) may decrease social anxiety by training emotion regulation skills. This randomized controlled trial of CBT for SAD examined changes in weekly frequency and success of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, as well as weekly intensity of social anxiety among patients receiving 16 weekly sessions of individual CBT. We expected these variables to (1) differ from pre-to-post-CBT vs. Waitlist, (2) have differential trajectories during CBT, and (3) covary during CBT. We also expected that weekly changes in emotion regulation would predict (4) subsequent weekly changes in social anxiety, and (5) changes in social anxiety both during and post-CBT. Compared to Waitlist, CBT increased cognitive reappraisal frequency and success, decreased social anxiety, but had no impact on expressive suppression. During CBT, weekly cognitive reappraisal frequency and success increased, whereas weekly expressive suppression frequency and social anxiety decreased. Weekly decreases in social anxiety were associated with concurrent increases in reappraisal success and decreases in suppression frequency. Granger causality analysis showed that only reappraisal success increases predicted decreases in subsequent social anxiety during CBT. Reappraisal success increases pre-to-post-CBT predicted reductions in social anxiety symptom severity post-CBT. The trajectory of weekly changes in emotion regulation strategies may help clinicians understand whether CBT is effective and predict decreases in social anxiety.

Keywords: social anxiety, emotion regulation, reappraisal, suppression, CBT, trajectory of change

INTRODUCTION

Three decades ago, David Barlow and colleagues suggested several compelling reasons to measure change during therapy (Barlow, Hayes, & Nelson, 1984). One reason is that more refined assessment of change in a patient’s psychological functioning during treatment provides the opportunity to modify specific treatment components or to shift the type of treatment being offered. Another reason is that such a focus is needed to advance our understanding of how, why, and for whom these clinical interventions work. A third reason is that more refined measurements of change during therapy may lead to greater accountability in how clinicians deliver and assess treatments they provide and may empirically elucidate for patients, insurance companies, and governmental agencies the efficacy of psychotherapy.

Despite this urgent call for research on change processes during therapy, the empirical record of measuring change during therapy is still quite slim. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the best validated psychosocial interventions for psychological disorders (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006), especially mood and anxiety disorders (Hofmann & Smits, 2008). Although change in emotion regulation processes has been proposed as one key mechanism of action in CBT for mood and anxiety disorders (Hofmann, Sawyer, Fang, & Asnaani, 2012;, Campbell-Sills & Barlow, 2007), the session-to-session changes in emotion regulation and their relation to changes in clinical symptoms are still not well understood.

One psychological disorder in which emotion regulation processes have been examined is social anxiety disorder (SAD) (Goldin, Manber, Hakimi, Canli, & Gross, 2009; Goldin, Manber-Ball, Werner, Heimberg, & Gross, 2009; Werner, Goldin, Ball, Heimberg, & Gross, 2011). SAD is highly prevalent (12%; Kessler et al., 2005), usually begins early in life, well before the onset of other anxiety disorders, substance use, and major depression (Otto et al., 2001), and is associated with significant impairment in social, educational, and occupational functioning (Acarturk, Graaf, Straten, Have, & Cuijpers, 2008; Stein & Kean, 2000). SAD is characterized by excessive fear of humiliation and embarrassment in social evaluative situations (Stein & Stein, 2008), exaggerated emotional reactivity, and a maladaptive emotion-regulation profile characterized by relatively high levels of generally maladaptive forms of emotion regulation such as expressive suppression, and relatively low levels of generally adaptive forms of emotion regulation such as cognitive reappraisal (Goldin, Manber, et al., 2009; Goldin, Manber-Ball, et al., 2009). Thus, SAD can be viewed as involving problematic cognition-emotion interactions that persist unless treated (Bruce et al., 2005).

Both group (Heimberg & Becker, 2002) and individual (Clark et al., 2006; D.M. Clark et al., 2003; Goldin et al., 2012; Hope, Heimberg, Juster, & Turk, 2000; Ledley et al., 2009) formats of CBT have demonstrated efficacy as psychosocial interventions for SAD with similar levels of clinically significant change in social anxiety symptom severity (Goldin et al., 2012; Moscovitch et al., 2012). Because not all patients achieve clinically significant reduction of social anxiety symptoms, however, there is clearly a need to better understand what changes are occurring during CBT that relate to treatment outcome. Prior studies have shown changes in several cognitive processes during CBT for SAD, including changes in probability bias for negative social events (Smits, Rosenfield, McDonald, & Telch, 2006), estimated probability and estimated cost of negative social events, safety behaviors (Hoffart, Borge, Sexton, & Clark, 2009), anticipated aversive social outcomes (Hofmann, 2004), positive and negative self-views (Goldin et al., 2013), interpersonal core beliefs (Boden et al., 2012), and cognitive reappraisal self-efficacy (Goldin et al., 2012). What has not been reported to date, however, is how cognitive processes (specifically cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression) change weekly during treatment, and whether they predict weekly changes in social anxiety and CBT outcome. This is important given the proposed role of emotion regulation in the etiology, maintenance, and treatment of most forms of psychopathology (Campbell-Sills & Barlow, 2007; Hofmann et al., 2012).

To investigate this proposed mechanism of action underlying CBT for SAD, clinical treatment studies have begun to quantify changes in specific emotion regulation processes during treatment in patients with SAD. Using the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross & John, 2003), which measures the frequency of use of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, Moscovitch and colleagues (Moscovitch et al., 2012) found that (a) group CBT led to linear increases in the habitual use of cognitive reappraisal but no changes in the use of expressive suppression, and (b) pre-to-mid-CBT increases in use of cognitive reappraisal were correlated with pre-to-post-CBT decreases in social anxiety symptoms. Using a more recently developed variant of the ERQ designed to assess emotion regulation self-efficacy (Goldin, Manber-Ball, et al., 2009), Goldin and colleagues (Goldin et al., 2012) found that the impact of individual CBT for SAD on reduction of social anxiety symptom severity was mediated by increases in cognitive reappraisal self-efficacy. These two studies provide initial empirical support for the role of change in emotion regulation during CBT for SAD. However, notwithstanding the imperative to elucidate the mechanisms of treatments by measuring change during therapy (Barlow et al., 1984), no studies have measured weekly change trajectories in emotion regulation processes and social anxiety symptoms throughout CBT for SAD.

Our goal in the present study was to investigate changes in the frequency and success of use of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, as well as changes in social anxiety, during CBT for SAD. Hypothesis 1: From pre-to-post-treatment, we expected that, compared to a waitlist condition (WL), CBT for SAD would result in greater increases in the frequency and success of cognitive reappraisal, greater decreases in the frequency of expressive suppression, and greater decreases in social anxiety. Hypothesis 2: Across 16 sessions of CBT, we expected a linear trajectory of increases in the weekly frequency and success of cognitive reappraisal, decreases in the frequency of expressive suppression, and decreases in social anxiety. Hypothesis 3: During CBT, we expected that increases in cognitive reappraisal (both the frequency and success) would covary inversely with social anxiety. Hypothesis 4: Using Granger causality analysis, we expected that changes in weekly cognitive reappraisal would predict subsequent weekly social anxiety during CBT. Hypothesis 5: We expected that increases in both the frequency and success of cognitive reappraisal during CBT, as well as greater inverse covariation of social anxiety with both frequency and success in cognitive reappraisal would predict pre-to-post-CBT decreases in social anxiety.

METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

From 436 individuals assessed for eligibility, 110 were administered the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for the DSM-IV-Lifetime version (ADIS-IV-L; (Di Nardo, Brown, & Barlow, 1994) to determine whether they fulfilled DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for a principal diagnosis of generalized SAD (see CONSORT Figure in Goldin et al., 2012). With regard to exclusion criteria, because participants were part of a larger fMRI study, they had to pass an magnetic resonance safety screen, be right-handed as assessed by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971), and could not report current pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy, past CBT, or history of neurological or cardiovascular disorders that might impact cerebral blood flow or psychological functioning. Excluding 26 individuals who did not meet diagnostic criteria and 9 with incomplete baseline assessments, 75 patients were randomly assigned to either immediate CBT (n = 38) or a WL control group (n = 37) who were subsequently offered CBT after the waiting period. Dropout rates did not differ for CBT (n = 6; 16%) and WL (n = 5; 14%). In total, 57 patients completed CBT.

PROCEDURE

Participants had to pass a telephone screening before scheduling a face-to-face clinical interview based on the ADIS-IV-L. After all baseline assessments were completed, patients were randomly assigned to immediate CBT or WL as determined by Efron’s biased coin randomization procedure (Efron, 1971) which supports approximately equal sample sizes throughout the duration of a clinical trial. CBT was provided at no charge. Participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University.

WEEKLY MEASURES OF EMOTION REGULATION AND SOCIAL ANXIETY

To investigate weekly changes in emotion regulation and social anxiety during CBT, we obtained weekly repeated measurements of clinical symptoms and emotion regulation processes during treatment of SAD. We assessed weekly frequency and successful use of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression on a scale from 0% to 100% of the time during social situations encountered during the past week. As shown in the Appendix, we described cognitive reappraisal frequency as “How often did you try to change the way you were thinking about the situation you were in?” and reappraisal success as “When you tried to change the way you were thinking, how successful was this strategy at decreasing your anxiety?” Expressive suppression frequency was defined as “How often did you try to hide all visible signs of your anxiety?” and suppression success as “When you tried to hide your anxiety, how successful was this strategy at fooling others?” The assessment of weekly social anxiety consisted of ratings of social anxiety intensity, distress, and interference with functioning from 0 (not at all) to 100 (severe) during the last week. Patients completed this assessment along with additional items that will be reported elsewhere at baseline, weekly during CBT, monthly during WL, and immediately post-CBT/WL.

BASELINE AND POST-TREATMENT MEASURE OF SOCIAL ANXIETY

The baseline and post-treatment measure of social anxiety symptom severity is the 24-item Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale-Self-Report (LSAS-SR; Fresco et al., 2001; Liebowitz, 1987). It uses a 4-point Likert-type scale to obtain ratings of fear and of avoidance, with a range from 0 (none and never, respectively) to 3 (severe and usually, respectively) for 11 social interaction situations and 13 performance situations during the past week. Ratings are summed for a total LSAS-SR score (range = 0–144). The LSAS-SR has good reliability and construct validity (Rytwinski et al., 2009), and its internal consistency was excellent at baseline in this study (Cronbach’s alpha = .91).

INDIVIDUAL-COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL THERAPY FOR SAD

Managing Social Anxiety: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach is a manualized 16 sessions individual treatment protocol which includes a therapist guide (Hope, Heimberg, & Turk, 2006) and a client workbook (Hope et al., 2000). The early phase (sessions 1 to 6) of CBT covered psychoeducation about SAD, orientation to CBT, and cognitive restructuring training. The latter phase (sessions 7–16) of CBT included graduated exposure to feared social situations within session and as homework, examination and modification of core beliefs, and relapse prevention and termination. For this study, all four therapists achieved proficiency in implementing CBT prior to treating study participants, were trained by and had weekly group supervision with Dr. Heimberg, an expert in CBT for SAD and one of the principal developers of the CBT protocol, and met treatment adherence criteria over the course of the study (for details see Goldin et al., 2012).

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Approximately 20% (15/75) of patients had some weekly data that were missing at random due to incomplete responses (e.g., patient forgot to complete, was sick, on vacation, etc.). To examine whether missing data could be predicted, we conducted logistic regression analyses that showed that clinical (e.g., immediate or delayed CBT, CBT responder based on LSAS-SR, age at SAD symptom onset, duration of SAD) and demographic (e.g., gender, ethnicity, age) variables did not predict the likelihood of having a missing data pattern (0 = not missing, 1 = missing) at p < .05. Missing values were imputed using full-information maximum likelihood estimation procedures, which generate unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors using all available observations for data missing at random (Enders, 2001).

For Hypothesis 1, to determine whether CBT vs. WL differentially affected emotion regulation and social anxiety, we conducted an intent-to-treat analysis that used between-group t-tests on pre-to-post CBT/WL change scores. We report effect sizes as partial eta2 (ηp2) (Pierce, Block, & Aguinis, 2004). For the analysis of weekly changes and covariation of emotion regulation and social anxiety during CBT, we first determined empirically whether we could combine data from patients randomized to immediate CBT and those who completed CBT after WL. To do this, we implemented univariate multilevel models with treatment group as a predictor of the weekly trajectories (i.e., random slopes, γ) of emotion regulation and social anxiety. This analysis yielded no significant immediate CBT vs. CBT after WL group differences in the weekly slopes of reappraisal frequency (γ = .14, SE = .38, p > .05), reappraisal success (γ = −.82, SE = .44, p > .05), suppression frequency (γ = −.12, SE = .51, p > .05), suppression success (γ = −.76, SE = .45, p > .05) or social anxiety (γ = .39, SE = .34, p > .05). Thus, we combined data from both groups for analyses that examined the impact of CBT on weekly trajectories of emotion regulation and social anxiety. Increasing the sample size provided greater power to generate more reliable estimates of the trajectories during CBT.

For Hypothesis 2, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses in Mplus v.6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010) to test using well-known procedures and criteria (Brown, 2006; Meredith, 1993) whether the pattern of change from baseline to post-CBT was statistically equivalent (i.e., measurement invariance) for four emotion regulation variables and, separately, three social anxiety variables. We applied a series of models that ranged from unconstrained to more restricted, with each model imposing successive equality constraints on the corresponding factor loadings and intercepts. The resulting change in model fit was evaluated by comparing Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) indices (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002; Little, Preacher, Selig, & Card, 2007). Given the large number of measurement time points (18 time points: baseline, sessions 1–16, and immediately post-CBT), we selected 4 critical and equally spaced time points (baseline, week 5, week 11, and immediately post-CBT) to test invariance in the pattern of change over time.

For emotion regulation processes, the confirmatory factor analysis found non-equivalence in the temporal trajectories, indicating that we could not combine cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression frequency and success variables into a single construct (Supplemental Table 1). Thus, we examined the trajectories of the four emotion regulation variables separately. In contrast, the confirmatory factor analyses showed equivalent trajectories for social anxiety, meaning that the same constructs were being assessed by the three indicators of social anxiety across time (Supplemental Table 2). Thus, we computed the mean of the three social anxiety indicators as a composite variable for use in all subsequent analyses. To investigate the slope of the emotion regulation processes across CBT, we implemented a curve-estimation analysis to compare linear, quadratic and cubic slopes.

For Hypothesis 3, to examine the longitudinal relationships (i.e., covariation across time) between weekly emotion regulation and social anxiety, we implemented multivariate multilevel models. Multilevel modeling (MLM) is an extension of the general linear model and facilitates analysis of hierarchically structured data (e.g., weekly emotion regulation ratings nested within participant) by directly modeling the clustering as level-specific orthogonal components (e.g., between- and within-persons). This approach allows for lower-level parameters (e.g., intercept and slope coefficients) to vary across higher-level units (e.g., individuals), yields unbiased standard errors (avoiding Type I errors) and estimates of variance explained (R2), and allows for testing of complex hypotheses (see Hox (2002) and Snijders and Bosker (1999) for an in-depth review of the MLM framework and specification). Multivariate multilevel models can be used to examine relationships between patterns of change in two (or more) clustered variables (Goldstein, 1995; Hertzog & Nesselroade, 2003; MacCallum, Kim, Malarkey, & Kielcolt-Glasser, 1997; Willett & Sayer, 1994). Multivariate models can test multiple hypotheses simultaneously (e.g., examining treatment effects on two outcomes, reappraisal frequency and success) and estimate the correlation between growth trajectories (e.g., of emotion regulation and social anxiety) in a single model. This multivariate approach is more powerful (compared to univariate analyses), particularly when the two outcomes are correlated and have different patterns of missing data (see Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; Snijders & Bosker, 1999).

Four multivariate multilevel models were fit, with each modeling the covariation between the change in social anxiety with change in one of 4 emotion regulation outcomes: reappraisal frequency, reappraisal success, suppression frequency, and suppression success. Model specification was as follows for the within-persons and between-persons models:

Within-persons (Level 1):

The week of measurement was used to predict within-person variance in social anxiety and emotion regulation outcomes at week i for person j. β0j and β2j represent the conditional mean outcome score (social anxiety or emotion regulation outcomes), β1j and β3j represent the slope of the week predictor, and e1ij and e2ij represent the within-persons random error. In addition, an autoregressive covariance matrix was specified to account for serial dependency in repeated measures of trajectories; this approach ensures that each dependent variable represents a change in relation to previous scores.

Between-persons (Level 2):

where, intercepts and slopes were specified as random (i.e., varying across individuals; u0j, u1j, u2j, u3j) and hypothesized to be drawn from a multivariate normal distribution with a mean vector of zero, unknown variances (τ00, τ11, τ22, τ33) and covariances (social anxiety: τ10; emotion regulation: τ32; cross-domain: τ20, τ21, τ30, τ31). Our primary interest was in examining the cross-domain slope covariance (τ31) between the trajectories of emotion regulation and social anxiety throughout 16 sessions of CBT.

For Hypothesis 4, we implemented a Granger causality analysis to determine whether weekly ratings of emotion regulation at time t-1 predicted weekly ratings of social anxiety at time t during CBT. We also tested the inverse relationships (i.e., whether social anxiety at time t-1 predicted emotion regulation at time t) to determine specificity of prediction.

For Hypothesis 5, we used linear regression to determine whether (1) changes in emotion regulation during CBT or (2) covariation of weekly emotion regulation and social anxiety during CBT predicted post-CBT social anxiety.

RESULTS

PRELIMINARY ANALYSES

As reported previously (Goldin et al., 2013; Goldin et al., 2012), patients in the CBT and WL groups did not differ significantly in gender, age, education, ethnicity, income, marital status, current or past Axis I comorbidity, past non-CBT psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy, age at symptom onset, and years since symptom onset.

To investigate test-retest reliability of the weekly single-item measures of frequency and success of reappraisal and expressive suppression, we computed correlation coefficients between adjacent pairs of the 5 measurement time points for the Waitlist group (baseline, 1 month, 2 months, 3 months, post-Waitlist). The mean test-retest correlation coefficients across five time points for reappraisal frequency (.69, range = .49–.81) and success (.57, range = .46–.71), and expressive suppression frequency (.68, range = .47–.87) and success (.62) were adequate. The only non-significant test-retest correlation was for expressive suppression success from baseline to 1 month. Fourteen of 16 correlation coefficients were significant at p < .009 or better. These results suggest overall significant stability across the 5 measurement time points during WL for the 1-item measures of the four emotion regulation processes in an untreated group of patients with generalized SAD.

HYPOTHESIS 1: PRE-POST CBT CHANGE

To address Hypothesis 1, we conducted between-group t-tests on pre-to-post-CBT/WL change scores for emotion regulation and social anxiety. For emotion regulation, compared to WL, CBT resulted in greater increases in reappraisal frequency (ΔCBT, Mean ± SD: 22.3±31.0 vs. ΔWL: 4.7±27.2; t73 = 2.60, p = .011, ηp2 = .09) and reappraisal success (ΔCBT: 33.6±30.0 vs. ΔWL: 9.4±29.4; t73 = 3.52, p = .001, ηp2 = .15), but no group differences in suppression frequency (ΔCBT: −11.8±37.5 vs. ΔWL: −2.2±24.3; t73 = 1.30, p = .20, ηp2 = .02) or suppression success (ΔCBT: 0.8±27.9 vs. ΔWL: 5.8±28.5; t73 = 0.78, p = .44, ηp2 = .01). For social anxiety, compared to WL, CBT resulted in greater decreases (ΔCBT: −30.4±26.6 vs. ΔWL: −8.2±12.4; t73 = 4.64, p < .001, ηp2 = .23).

HYPOTHESIS 2: TRAJECTORIES OF CHANGE DURING CBT

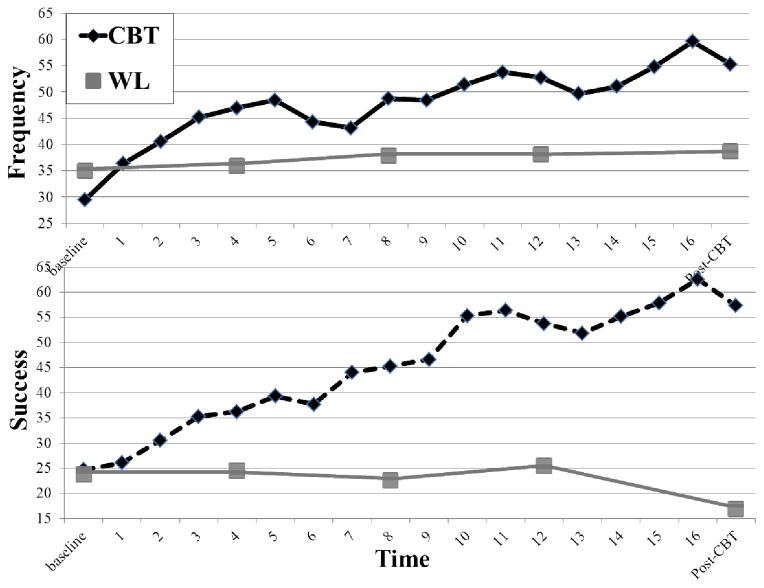

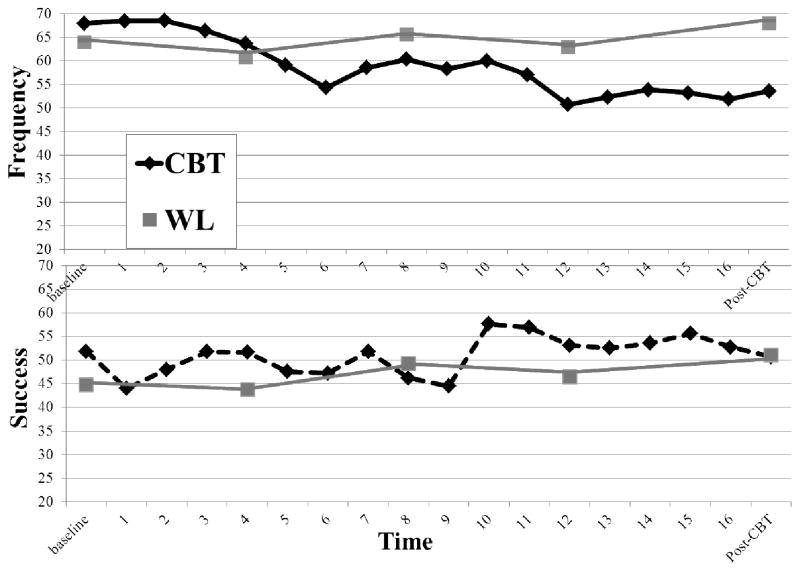

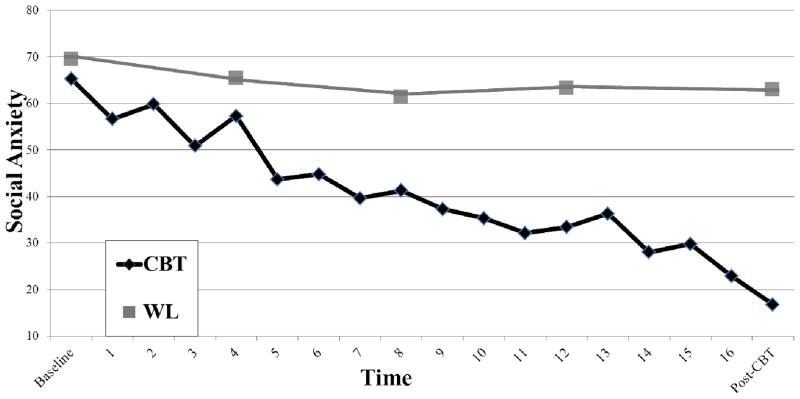

Multivariate multilevel models were used to address Hypothesis 2. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, there were increases during 16 sessions of CBT in reappraisal frequency (γ = 1.26, SE = .18, p < .01) and reappraisal success (γ = 1.94, SE = .21, p < .01), decreases in suppression frequency (γ = −1.17, SE = .24, p < .01), but no change in suppression success (γ = 0.31, SE = .21, p = .14). As shown in Figure 3, social anxiety decreased throughout CBT (γ= −1.64, SE = .16, p < .01). To characterize the slope that best fit each group mean emotion regulation time series, we conducted a follow-up curve estimation analysis using a Bonferroni corrected p-value of .01. This revealed that a cubic slope fit reappraisal frequency (R2 = .88, F(3,14) = 33.08, p < .001), a quadratic slope fit reappraisal success (R2 = .96, F(2,15) = 165.26, p < .001), a quadratic slope fit suppression frequency (R2 = .84, F(2,15) = 38.24, p < .001), and there was no fit for suppression success (all ps > .05).

Figure 1.

Trajectories of cognitive reappraisal frequency and success during cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and waiting list (WL) conditions

Figure 2.

Trajectories of expressive suppression frequency and success during cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and waiting list (WL) conditions

Figure 3.

Trajectories of social anxiety during cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and waiting list (WL) conditions

HYPOTHESIS 3: RESPONSE COVARIATION DURING CBT

To address Hypothesis 3, we used multivariate multilevel models to identify patterns of significant covariation in weekly emotion regulation and social anxiety across 16 sessions of CBT. Increases in reappraisal success were related to decreases in social anxiety (r = −.54, p < .05). Decreases in suppression frequency were also related to decreases in social anxiety (r = .52, p < .05). None of the other pairwise associations were significant (all ps > .05).

HYPOTHESIS 4: WEEKLY CHANGES IN EMOTION REGULATION TO PREDICT SUBSEQUENT SOCIAL ANXIETY

For Hypothesis 4, a Granger causality analysis indicated that weekly ratings of reappraisal success predicted subsequent weekly ratings of social anxiety (unstandardized beta = −1.02, SE = .36, standardized beta = −.98, t = 2.81, p = .01; F(1,15) = 8.44, p = .01, ΔR2 = .07). There was no evidence that social anxiety predicted subsequent reappraisal success (F(1,15) = 0.02, p > .05), reappraisal frequency predicted subsequent social anxiety (F(1,15) = 1.85, p > .05), social anxiety predicted subsequent reappraisal frequency (F(1,15) = 1.41, p > .05), or expressive suppression frequency or success predicted subsequent social anxiety (all Fs < 2.33, ps > .05). These results suggest a single specific unidirectional predictive relationship characterized by increases in weekly reappraisal success predicting subsequent decreases in weekly social anxiety across 16 weekly sessions of CBT for SAD.

HYPOTHESIS 5: PREDICTING CBT OUTCOMES

To address Hypothesis 5, we implemented a linear regression to predict post-CBT decreases in social anxiety symptom severity (LSAS-SR). After controlling for baseline LSAS-SR, only pre-to-post-CBT increases in reappraisal success, but not in reappraisal frequency (p > .08) or suppression frequency (p > .17), predicted post-CBT LSAS-SR (unique variance explained: ΔR2 = .10, standardized β = −.33, F1,51 = 6.3, p = .02). A follow-up analysis showed that LSAS-SR reduction post-CBT was associated with reappraisal success both during the early phase of CBT (psychoeducation and cognitive restructuring training during sessions 1 to 6; r(32) = .41, p = .02) and during the later phase of CBT (exposure + cognitive restructuring during sessions 7–16; r(32) = .58, p < .001).

We also investigated whether covariation of emotion regulation and social anxiety trajectories predicted improvement in LSAS-SR post-CBT. A linear regression showed that, after controlling for baseline social anxiety symptom severity, weekly social anxiety, and weekly reappraisal success, greater inverse covariation of reappraisal success and social anxiety trajectories during CBT significantly predicted reductions in LSAS-SR post-CBT (ΔR2 = .07, standardized β = .32, F(1,15) = 6.74, p = .012). All other covariation relationships were not predictive (all ps > .05).

DISCUSSION

Heeding the directive to measure change during treatment issued by (Barlow et al., 1984) three decades ago, the primary goal of this study was to investigate whether CBT induces changes in emotion regulation processes that have been proposed as factors that influence clinical symptoms in patients with SAD. CBT for SAD led to changes in weekly cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression that were related to reductions in weekly social anxiety, as well as cognitive reappraisal success that predicted reductions in social anxiety one week later during CBT, and predicted reductions in social anxiety symptom severity post-CBT.

WEEKLY CHANGES IN EMOTION REGULATION AND ANXIETY

With regard to pre-to-post CBT changes (Hypothesis 1), compared to WL, CBT yielded greater reappraisal frequency and reappraisal success, no changes in expressive suppression, and reductions in social anxiety. These results converge with prior studies that have reported pre-to-post-CBT increases in the use of cognitive reappraisal, no change in expressive suppression, and decreases in social anxiety symptoms (Moscovitch et al., 2012). This finding was extended and refined when we investigated the trajectories of emotion regulation and social anxiety across 16 weekly sessions of CBT using multilevel modeling of longitudinal data (Hypothesis 2). This analysis revealed that reappraisal frequency and reappraisal success increased, suppression frequency decreased, suppression success did not change, and social anxiety decreased during the course of treatment. The additional finding of decreases in suppression frequency during CBT is likely related to the enhanced statistical power and sensitivity provided by the multilevel modeling approach.

We expected linear weekly changes in emotion regulation during CBT. A curve estimation analysis, however, did not find that a linear slope was the optimal fit for any of the four emotion regulation processes. Instead, curve estimation indicated that a cubic slope fit reappraisal frequency, which appears to have three waves of increases, as shown in Figure 1, including one during the early phase of CBT (psychoeducation and cognitive restructuring training) and two during that later phase of CBT (exposure plus cognitive restructuring). A quadratic slope best fir reappraisal success which peaked during the end of the series of exposures during the later phase of CBT. In contrast, the quadratic slope that best fit suppression frequency, as shown in Figure 2, shows an temporary increase in suppression frequency during the first few exposure sessions (sessions 7 to 11), followed by a reduction in subsequent exposure sessions (12–16). No particular slope fit expressive suppression success. These patterns of change indicate differential rates of change in reappraisal and suppression processes during the different phases of CBT. Because this was a post hoc analysis, future research should further examine slope differences in emotion regulation process and investigate mechanisms that might account for these differences.

Cognitive-behavioral models suggest that CBT should increase the use of adaptive cognitive reappraisal and decrease the use maladaptive expressive suppression. Findings in our study support this notion. These changes should enhance the probability of having a successful experience when implementing reappraisal both within and between therapy sessions. However, it is important to note that greater frequency of utilizing a reappraisal strategy does not necessarily lead to greater success when implementing reappraisal. For patients, reappraisal success most likely depends on a combination of (a) the skill of the psychotherapist in carefully tailoring a progression of exposures which optimally supports learning and self-efficacy in each patient, and (b) the willingness and tenacity of the patient in implementing reappraisal of emotional reactions. Most likely because of the emphasis on emotion awareness, emotion expression and cognitive restructuring during CBT, expressive suppression (i.e., not showing and actively sharing one’s emotions with others) decreased in frequency during CBT. This pattern of changes supports models that suggest that CBT facilitates a shift to more adaptive emotion regulation, specifically, lesser reliance on expressive suppression and greater implementation of cognitive reappraisal as the predominant method for working with emotions.

To better understand the dynamic relationship between emotion regulation processes and social anxiety, we examined (a) covariation of emotion regulation and social anxiety measured weekly over the course of CBT (Hypothesis 3), as well as (b) whether weekly changes in emotion regulation predicted subsequent changes in weekly social anxiety using Granger causality analyses (Hypothesis 4). The covariation analyses showed that weekly increases in reappraisal success and decreases in expressive suppression frequency were both related to decreases in weekly social anxiety. Whereas increase in the use of reappraisal during treatment has been linked to improved treatment outcome (Moscovitch et al., 2012), our findings show, using a more refined temporal analysis, that increases in self-reported success when implementing reappraisal (and not reappraisal frequency) were related to reductions in social anxiety during CBT. This suggests that in the case of CBT for SAD, how effectively a patient believes she/he implements reappraisal may be more informative than the number of times a patient actually implements reappraisal when faced with an anxiety inducing social situation. However, in contrast, reduction in expressive suppression frequency, which may be characterized as a form of intentional avoidance of social interaction, but not suppression success, was related to reductions in social anxiety during CBT. These findings support models of SAD that suggest enhancing reappraisal and reducing avoidance/suppression are likely mechanisms of change in CBT for SAD.

The Granger causality analysis demonstrated that only weekly reappraisal success predicted subsequent weekly social anxiety during CBT. The inverse was not significant. This finding of unidirectional prediction provides further support that CBT may alter the client’s beliefs as well as actual success in implementing reappraisal to reduce anxiety during treatment. That reappraisal frequency and expressive suppression frequency and success were not predictive of subsequent changes in social anxiety provides specificity for the importance of reappraisal success. With regard to identifying whether changes during CBT are related to post-CBT clinical outcomes, our final analysis revealed that only (a) increases in reappraisal success during CBT, and (b) greater inverse covariation of reappraisal success and social anxiety during CBT predicted post-CBT social anxiety symptom severity reduction in the LSAS-SR (Hypothesis 5).

MECHANISMS OF ACTION IN CBT FOR SAD

Findings from this study highlight two distinct mechanisms by which CBT may ameliorate social anxiety. One involves an increase in reappraisal success. The second involves a decrease in expressive suppression frequency.

In this context, reappraisal is an approach-oriented behavior characterized by applying logic, thinking, reframing, language, perspective-taking, and meaning-making to modify the salience of an emotion-inducing cue. Reappraisal involves a sequence of cognitive processes: appraising a cue, assessing its general value and personal salience, generating possible alternative interpretations of the cue and context, selecting one, monitoring how effectively it modulates emotional reactivity, and then sustaining or terminating the implementation of that interpretation. Obviously, this is a highly complex and cognitively rich set of component processes that involves a high degree of coordination and skill. In contrast, expressive suppression is essentially a withdrawal or avoidance orientation that involves inhibitory control processes characterized by actively shutting off any verbal (e.g., spoken, written) and non-verbal (e.g., facial expression, body posture, hand gestures) forms of communicating with others. Patients with SAD live a life that consistently reinforces expressive suppression and precludes cognitive reappraisal. There are many reasons for this, including suppression being less effortful, more familiar, and requiring less skill than reappraisal, as well as SAD patients having a greater wish to hide visible physiological indicators of anxiety (e.g., blushing, trembling, sweating) which they interpret as signs of weakness and vulnerability. This pattern of maladaptive emotion regulation becomes an engrained habit and a mode of being that leads to withdrawal and self-protection in the midst of others, silence, fear, myriad forms of avoidance, and invisible suffering.

The prediction analyses provided more support for the importance of changes in cognitive reappraisal success during CBT. Increases in the trajectory of self-reported reappraisal success during CBT were related to decreases in two indicators of social anxiety: social anxiety measured weekly during CBT and severity of social anxiety symptoms measured immediately post-CBT. Of the emotion regulation processes measured in this study, only self-reported reappraisal success was a significant predictor of reduction of severity of social anxiety symptoms post-CBT. This finding highlights the importance of identifying the factors that contribute to perceived reappraisal success within therapy sessions, between sessions, and following treatment.

Whereas several studies have identified appraisal processes that predict outcome of CBT for SAD, including changes in negative evaluation of anticipated aversive social outcomes, social fear, self-focus, safety behaviors, and loss of control (Hoffart et al., 2009; Hofmann, 2004; Moscovitch, Hofmann, Suvak, & In-Albon, 2005; Vogele et al., 2010), the only study to examine cognitive reappraisal processes found that changes in cognitive reappraisal self-efficacy during CBT mediated treatment outcome (Goldin et al., 2012). Cognitive reappraisal self-efficacy is a global measure of a person’s belief in his or her ability to implement reappraisal when needed. In contrast, cognitive reappraisal success, as assessed in the current study, measures the patient’s self-perception of how effectively she implemented reappraisal of social anxiety in social situations during the preceding week. This is a much more specific measure than global reappraisal self-efficacy. Thus, there is mounting evidence that CBT impacts cognitive reappraisal processes that influence social anxiety both during and post-CBT. These findings provide further empirical evidence for theoretical models that identify changes in emotion regulation processes as key factors underlying the effectiveness of CBT for mood and anxiety disorders,(Campbell-Sills & Barlow, 2007).

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Given the findings from this study, weekly evaluation of self-reported cognitive reappraisal success could provide the clinician an empirical basis for determining whether or not the trajectory from baseline to each assessment point indicates that the clinical intervention is on target to produce reductions in social anxiety symptoms. If not, then the clinician may want to modify the intervention (a) to create the conditions for more occasions of successful reappraisal both within and outside of therapy sessions, and (b) enhance the patient’s awareness of when she has, in fact, successfully implemented reappraisal strategies. This may involve focusing on less intense and more manageable exposures that result in sufficient numbers of reappraisals that are deemed successful in reducing toxic emotional reactions to social cues. Furthermore, our findings suggest that perceived quality (i.e., successful implementation or effectiveness), not quantity (i.e., frequency) of reappraisal may be more important for improved clinical outcomes.

LIMITATIONS

The current study focused on weekly changes during individual CBT in emotion regulation and social anxiety in patients with generalized SAD. Because we report only self-reported weekly frequency and success of cognitive reappraisal and of expressive suppression, conclusions are limited to these specific emotion regulation processes, temporal resolution, and mode of measurement. We focused on whether changes in each emotion regulation process predicted changes in social anxiety. Future studies may benefit from investigating whether the ratio of reappraisal success to frequency predicts treatment outcome. If so, this might suggest that clinicians encourage patients to conduct as many reappraisals as possible to increase the probability of successful ones and thus reduce anxiety symptoms. Although we measured weekly success in implementing reappraisal and expressive suppression, we should note that the questions were not phrased in an identical manner, which may potentially contribute to the differential results for these two emotion regulation success assessments. To obtain a greater understanding of the impact of CBT, future studies could directly compare additional types of emotion regulation (e.g., situation selection, situation modification, attention deployment, acceptance) with greater temporal resolution (e.g., daily measurements).

Another important limitation on the inferences drawn from the current study relates to the use of one specific form of psychotherapy. Although individual and group formats of CBT for SAD appear to be equally effective in randomized controlled trials (Stangier, Heidenreich, Peitz, Lauterbach, & Clark, 2003), no studies have investigated the differential impact of these two forms of CBT for SAD on weekly changes in emotion regulation and social anxiety. Additionally, to understand the specificity of CBT effects on weekly changes in emotion regulation, it will be helpful to construct RCTs that directly compare weekly changes in different types of clinical interventions for SAD, including applied relaxation (Clark et al., 2006), internet-delivered CBT (Andersson, Carlbring, & Furmark, 2012; Titov, Andrews, Choi, Schwencke, & Mahoney, 2008), online virtual acceptance-based behavioral therapy (Yuen et al., 2013), interpersonal psychotherapy (Stangier, Schramm, Heidenreich, Berger, & Clark, 2011), psychodynamic short-term group treatment (Leichsenring et al., 2013), mindfulness-based interventions (Goldin & Gross, 2010; Jazaieri, Goldin, Werner, Ziv, & Gross, 2012; Piet, Hougaard, Hecksher, & Rosenberg, 2010).

The current study examined SAD because of its high prevalence and the large percentage of patients who go untreated (80%; Grant et al., 2005). Given that problems with emotion regulation are considered to be a transdiagnostic feature of most mood and anxiety disorders, future studies will benefit from inclusions of patients with other psychiatric disorders to determine if the changes observed in this study are specific to patients with SAD or are generalizable across multiple mood and anxiety disorders. It will also be important to investigate the temporal dynamics of trajectories in emotion regulation during transdiagnostic versus diagnosis-specific CBT for anxiety disorders (Norton & Barrera, 2012). Identifying specific profiles of emotion regulation problems and how they change during therapy in different types of patients may inform current or future treatment protocols and enhance the reduction of clinical symptoms. More broadly, to achieve the goals of clinical science, we will need to empirically determine for whom, when, why and how our clinical interventions work, and continually enhance the dissemination of our interventions to those in need.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an NIMH Grant R01 MH076074, awarded to James Gross, Ph.D. Richard Heimberg, Ph.D. is the author of the commercially available CBT protocol which was utilized in this study.

Appendix

DURING THE PAST WEEK….

How intense has your social anxiety been?

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 |

| Not at all | Slightly | Moderately | Very | Extremely | ||||||

How distressed have you been by your social anxiety?

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 |

| Not at all | Slightly | Moderately | Markedly | Severely | ||||||

How much has your social anxiety interfered with your life as a whole (e.g., affected your daily routine, job, social activities, family life)?

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 |

| No interference | Mild interference | Moderate interference | Severe interference | Very severe interference | ||||||

For the following items, please consider the social situations you encountered this past week. Please circle the percentage that indicates how often you used a particular strategy to reduce your anxiety. 0% indicates that you used a particular strategy 0% of the time you encountered social situations, and 100% indicates that you used a particular strategy 100% of the time you encountered social situations. Because people sometimes use more than one strategy at once, or use strategies not listed here, these ratings may add up to less or more than 100%.

How often did you try to change the way you were thinking about the situation you were in?

| 0% | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% | 100% |

When you tried to change the way you were thinking, how successful was this strategy at decreasing your anxiety?

| 0% | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% | 100% |

How often did you try to hide all visible signs of your anxiety?

| 0% | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% | 100% |

When you tried to hide your anxiety, how successful was this strategy at fooling others?

| 0% | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% | 100% |

Footnotes

Philippe Goldin, Ph.D., who is independent of any commercial funder, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00380731; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00380731?term=social+anxiety+cognitive+behavioral+therapy+Stanford&rank=1

None of the authors of this manuscript have any biomedical financial interests or other potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Acarturk C, Graaf R, Straten A, Have MT, Cuijpers P. Social phobia and number of social fears, and their association with comorbidity, health-related quality of life and help seeking. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2008;43(4):273–279. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0309-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Carlbring P, Furmark T. Therapist experience and knowledge acquisition in internet-delivered CBT for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow D, Hayes S, Nelson R. The scientist practitioner: Research and accountability in clinical and educational settings. New York: Pergamon Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, John OP, Goldin PR, Werner K, Heimberg RG, Gross JJ. The role of maladaptive beliefs in cognitive-behavioral therapy: Evidence from social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2012;50(5):287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce SE, Yonkers KA, Otto MW, Eisen JL, Weisberg RB, Pagano M, Keller MB. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on recovery and recurrence in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder: A 12-year prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1179–1187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Barlow DH. Incorporating emotion regulation into conceptualizations and treatments of anxiety and mood disorders. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 542–559. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9(2):233–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Ehlers A, Hackmann A, McManus F, Fennell M, Grey N, Wild J. Cognitive therapy versus exposure and applied relaxation in social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(3):568–578. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Ehlers A, McManus F, Hackmann A, Fennell M, Campbell H, Louis B. Cognitive therapy versus fluoxetine in generalized social phobia: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(6):1058–1067. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime version (ADIS-IV-L) New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Forcing a sequential experiment to be balanced. Biometrika. 1971;58(3):403–417. doi: 10.1093/biomet/58.3.403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychological Methods. 2001;6(3):352–370. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Coles ME, Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hami S, Stein MB, Goetz D. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: A comparison of the psychometric properties of self-report and clinician-administered formats. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31(6):1025–1035. doi: 10.1017/S0033291701004056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion. 2010;10:83–91. doi: 10.1037/a0018441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Jazaieri H, Ziv M, Kraemer H, Heimberg R, Gross JJ. Changes in positive self-views mediate the effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;1(3):301–310. doi: 10.1177/2167702613476867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Manber T, Hakimi S, Canli T, Gross JJ. Neural bases of social anxiety disorder: Emotional reactivity and cognitive regulation during social and physical threat. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):170–180. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Manber-Ball T, Werner K, Heimberg R, Gross JJ. Neural mechanisms of cognitive reappraisal of negative self-beliefs in social anxiety disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66(12):1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Ziv M, Jazaieri H, Werner K, Kraemer H, Heimberg RG, Gross JJ. Cognitive reappraisal self-efficacy mediates the effects of individual cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(6):1034–1040. doi: 10.1037/a0028555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Ziv M, Jazaieri H, Werner K, Kraemer H, Heimberg RG, Gross JJ. Cognitive Reappraisal Self-Efficacy Mediates the Effects of Individual Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012b;80(6):1034–1040. doi: 10.1037/a0028555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blanco C, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B. The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66(11):1351–1361. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Becker RE. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia: Basic mechanisms and clinical strategies. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffart A, Borge FM, Sexton H, Clark DM. Change processes in residential cognitive and interpersonal psychotherapy for social phobia: A process-outcome study. Behavior Therapy. 2009;40(1):10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG. Cognitive mediation of treatment change in social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:393–399. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Fang A, Asnaani A. Emotion dysregulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29(5):409–416. doi: 10.1002/da.21888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Smits JAJ. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):621–632. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Turk CL. Managing social anxiety: A cognitive-behavioral approach. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corp; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Turk CL. Therapist guide for managing social anxiety: A cognitive-behavioral therapy approach. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jazaieri H, Goldin PR, Werner K, Ziv M, Gross JJ. A Randomized Trial of MBSR Versus Aerobic Exercise for Social Anxiety Disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;68(7):715–731. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledley DR, Heimberg RG, Hope DA, Hayes SA, Zaider TI, Dyke MV, Fresco DM. Efficacy of a Manualized and Workbook-Driven Individual Treatment for Social Anxiety Disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2009;40(4):414. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichsenring F, Salzer S, Beutel ME, Herpertz S, Hiller W, Hoyer J, Leibing E. Psychodynamic therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy in social anxiety disorder: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170(7):759–767. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12081125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–173. doi: 10.1159/000414022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Preacher KJ, Selig JP, Card NA. New developments in latent variable panel analyses of longitudinal data. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31(4):357–365. doi: 10.1177/0165025407077757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W. Measurement invariance, factor analysis and factorial invariance. Psychometrika. 1993;58(4):525–543. doi: 10.1007/BF02294825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch DA, Gavric DL, Senn JM, Santesso DL, Miskovic V, Schmidt LA, Antony MM. Changes in judgment biases and use of emotion regulation strategies during cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder: Distinguishing treatment responders from nonresponders. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2012;36(4):261–271. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch DA, Hofmann SG, Suvak MK, In-Albon T. Mediation of changes in anxiety and depression during treatment of social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(5):945. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Barrera TL. Transdiagnostic versus diagnosis-specific CBT for anxiety disorders: A preliminary randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29(10):874–882. doi: 10.1002/da.21974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9(1):97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Pollack MH, Maki KM, Gould RA, Worthington JJ, 3rd, Smoller JW, Rosenbaum JF. Childhood history of anxiety disorders among adults with social phobia: Rates, correlates, and comparisons with patients with panic disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;14:209–213. doi: 10.1002/da.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce CA, Block RA, Aguinis H. Cautionary note on reporting eta-squared values from multifactor ANOVA designs. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2004;64(6):916–924. doi: 10.1177/0013164404264848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piet J, Hougaard E, Hecksher MS, Rosenberg NK. A randomized pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and group cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adults with social phobia. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2010;51(5):403–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytwinski NK, Fresco DM, Heimberg RG, Coles ME, Liebowitz MR, Cissell S, Hofmann SG. Screening for social anxiety disorder with the self-report version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:34–38. doi: 10.1002/da.20503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JAJ, Rosenfield D, McDonald R, Telch MJ. Cognitive mechanisms of social anxiety reduction: An examination of specificity and temporality. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(6):1203. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangier U, Heidenreich T, Peitz M, Lauterbach W, Clark DM. Cognitive therapy for social phobia: Individual versus group treatment. Behaviour Research And Therapy. 2003;41:991–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangier U, Schramm E, Heidenreich T, Berger M, Clark DM. Cognitive therapy vs interpersonal psychotherapy in social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):692–700. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.67. 68/7/692 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Kean YM. Disability and quality of life in social phobia: Epidemiologic findings. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1606–1613. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Stein DJ. Social anxiety disorder. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N, Andrews G, Choi I, Schwencke G, Mahoney A. Shyness 3: Randomized controlled trial of guided versus unguided Internet-based CBT for social phobia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;42(12):1030–1040. doi: 10.1080/00048670802512107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogele C, Ehlers A, Meyer AH, Frank M, Hahlweg K, Margraf J. Cognitive mediation of clinical improvement after intensive exposure therapy of agoraphobia and social phobia. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27(3):294–301. doi: 10.1002/da.20651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner KH, Goldin PR, Ball TM, Heimberg RG, Gross JJ. Assessing emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder: The emotion regulation interview. Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment. 2011;33(3):346–354. doi: 10.1007/s10862-011-9225-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF, Thompson JS. On Specifying the Null Model for Incremental Fit Indices in Structural Equation Modeling. Psychological Methods. 2003;8(1):16–37. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen EK, Herbert JD, Forman EM, Goetter EM, Comer R, Bradley JC. Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder Using Online Virtual Environments in Second Life. Behavior Therapy. 2013;44(1):51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.