Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Effective treatments for social anxiety disorder (SAD) exist, but additional treatment options are needed for non-responders as well as those who are either unable or unwilling to engage in traditional treatments. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) is one non-traditional treatment that has demonstrated efficacy in treating other mood and anxiety disorders, and preliminary data suggest its efficacy in SAD as well.

METHOD

Fifty-six adults (52% female; 41% Caucasian; Age (M ± SD): 32.8 ± 8.4) with SAD were randomized to MBSR or an active comparison condition, aerobic exercise (AE). At baseline and post-intervention, participants completed measures of clinical symptoms (Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, Social Interaction Anxiety Scale, Beck Depression Inventory-II, and Perceived Stress Scale) and subjective well-being (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Satisfaction with Life Scale, Self-Compassion Scale and UCLA-8 Loneliness Scale). At 3-months post intervention, a subset of these measures were re-administered. For clinical significance analyses, 48 healthy adults (52.1% female; 56.3% Caucasian; Age (M ± SD): 33.9 ± 9.8) were recruited. MBSR and AE participants were also compared to a separate untreated group of 29 adults (44.8% female; 48.3% Caucasian; Age (M ± SD): 32.3 ± 9.4) with generalized SAD who completed assessments over a comparable time period with no intervening treatment.

RESULTS

A 2 (Group) × 2 (Time) repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) on measures of clinical symptoms and well-being were conducted to examine pre to post and pre- to 3-month follow-up. MBSR and AE were both associated with reductions in social anxiety and depression and increases in subjective well-being, both immediately post intervention and at 3-months post intervention. When participants in the RCT were compared to the untreated SAD group, participants in both interventions exhibited improvements on measures of clinical symptoms and well-being.

CONCLUSION

Non-traditional interventions such as MBSR and AE merit further exploration as alternative or complementary treatments for SAD.

Keywords: MBSR, aerobic exercise, well-being, social anxiety, social phobia, SAD, treatment outcome

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is a highly prevalent (Kessler et al., 2005), chronic (Cairney et al., 2007), and undertreated (Wang et al., 2005) psychiatric condition. SAD is associated with self-criticism, low self-esteem (Cox, Fleet, & Stein, 2004), and an exaggerated focus on perceived deficient characteristics of the self (Goldin, Ramel, & Gross, 2009; Moscovitch, 2009). There are several empirically tested interventions for SAD, including pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). These interventions are associated with decreased social anxiety symptoms and improved quality of life and well-being (see review by Pontoski, Heimberg, Turk, & Coles, 2010). Unfortunately, there are many individuals with SAD who are unwilling to undertake these treatments or who fail to adequately respond to them. This has prompted a search for non-traditional interventions, including Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 1990).

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction

MBSR involves the cultivation of a non-judgmental, flexible, and present-moment attentional focus (Kabat-Zinn, 1990) through a variety of practices that are thought to reduce the habitual tendency to automatically engage in and react to evaluative mental states (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002). In community samples of adults, MBSR has resulted in improved psychological well-being and mental health in a number of controlled and uncontrolled trials (e.g., Birnie, Speca, & Carlson, 2010; Cordon, Brown, & Gibson, 2009). MBSR has been embraced as a popular integrative medicine intervention (Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, 2010).

Preliminary data suggest that mindfulness practice may be a useful alternative to the current psychological treatments for anxiety disorders (Miller, Fletcher, & Kabat-Zinn, 1995) for those who do not want to participate in traditional treatments or those who are treatment nonresponders. Meta-analyses have supported the notion that MBSR reduces symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression, and enhances well-being across clinical and non-clinical samples (e.g., Baer, 2003; Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004).

Although some studies have examined MBSR’s effects in mixed samples of patients with anxiety disorders (e.g., Vøllestad, Sivertsen, & Nielsen, 2011), few have targeted specific anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder: e.g., Craigie, Rees, & Marsh, 2008; S. Evans et al., 2008; Kabat-Zinn, Massion, Kristeller, & Peterson, 1992; Kim et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2007), and fewer still have focused on SAD specifically (e.g., Bögels, Sijbers, & Voncken, 2006; Goldin & Gross, 2010; Goldin et al., 2009; Kocovski, Fleming, & Rector, 2009; Koszycki, Benger, Shlik, & Bradwejn, 2007). Mindfulness-based treatments for SAD have been shown to improve mood, functionality, and quality of life (Kocovski et al., 2009), reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms (Goldin & Gross, 2010), and increase self-esteem (Goldin & Gross, 2010; Goldin et al., 2009). Although in adults with SAD, MBSR has been shown to effectively reduce some anxiety symptoms and increase well-being, MBSR did not achieve the rate of response on core symptoms of SAD when compared to group CBT (with 8/18 in CBT and 2/22 in MBSR achieving full remission rates) (Koszycki et al., 2007).

Aerobic Exercise

Physical exercise has been associated with a wide range of benefits, including improved physical health, mental health, and well-being (Penedo & Dahn, 2005). Psychologically, physical inactivity has been linked to increased symptoms of depression and anxiety (Ströhle, 2009) and decreased positive mood states (Penedo & Dahn, 2005). Several meta-analyses have observed a beneficial effect of exercise on anxiety (e.g., Petruzzello, Landers, Hatfield, Kubitz, & Salazar, 1991; Stich, 1998). Research has demonstrated that high-intensity aerobic exercise (AE) is associated with lowered anxiety sensitivity (Broman-Fulks, Berman, Rabian, & Webster, 2004) and state and trait anxiety (e.g., McEntee & Halgin, 1999). Studies have noted the positive effects of exercise on panic disorder (e.g., Broocks et al., 1998; Dratcu, 2001) and generalized anxiety disorder (e.g., McEntee & Halgin, 1999; Steptoe, Edwards, Moses, & Mathews, 1989).

Smits and colleagues’ (2008) study showed that even a 2-week exercise intervention, and a 2-week exercise plus cognitive restructuring intervention was able to lead to clinically significant changes in anxiety sensitivity when compared to a waitlist condition. Aerobic exercise has been gaining momentum as an alternative to traditional treatments for a variety of anxiety disorders (see reviews by Herring, O'Connor, & Dishman, 2010; Salmon, 2001), and AE has been studied in samples of mixed anxiety disorders (e.g., Merom et al., 2007), however, these findings are not clearly generalizable from one anxiety disorder to another (Ströhle, 2009). To date, there are no studies specifically examining the effects of aerobic exercise in SAD.

The Present Study

To address this gap in the literature, we conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of MBSR versus an active comparison condition, namely aerobic exercise (AE) in adults with SAD. Because AE has been shown to be beneficial across a range of symptoms and disorders and can include both individual and group components, therefore it seemed well-suited to be an active comparison condition that would allow us to match to non-specific factors of MBSR while having the absence of active ingredients in MBSR. We expected that both MBSR and AE would lead to clinical improvement, but that compared to AE, MBSR would result in greater reduction in clinical symptoms and greater enhancement of well-being at both immediately post intervention and at 3-months post intervention. To address the possibility of spontaneous improvement or regression to the mean, we compared the effects of the RCT (MBSR and AE) to a separate, untreated group of similar individuals with SAD who were assessed before and after a period of no treatment. We expected that, compared to this separate untreated SAD group, the RCT interventions would both result in greater reduction of clinical symptoms and enhancement of well-being.

Methods

RCT Participants

Participants in this randomized controlled trial (RCT) were adults who met DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for a principal diagnosis of generalized SAD. Diagnoses were made by clinical psychologists (PG & KW) who were trained (via training tapes and test cases) to administer the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Lifetime version (ADIS-IV-L; Di Nardo, Brown, & Barlow, 1994). The ADIS-IV-L is a structured interview designed to assess for current and past (lifetime) diagnoses of anxiety disorders and permits differential diagnosis among the anxiety disorders according to DSM-IV criteria. In addition to anxiety disorders, the ADIS-IV-L assesses current mood, somatoform, substance use disorders, medical and psychiatric treatment history, and includes screening questions for psychotic and conversion symptoms as well as familial psychiatric history. The ADIS-IV-L has demonstrated high reliability for a principal diagnosis of SAD (Brown, DiNardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001).

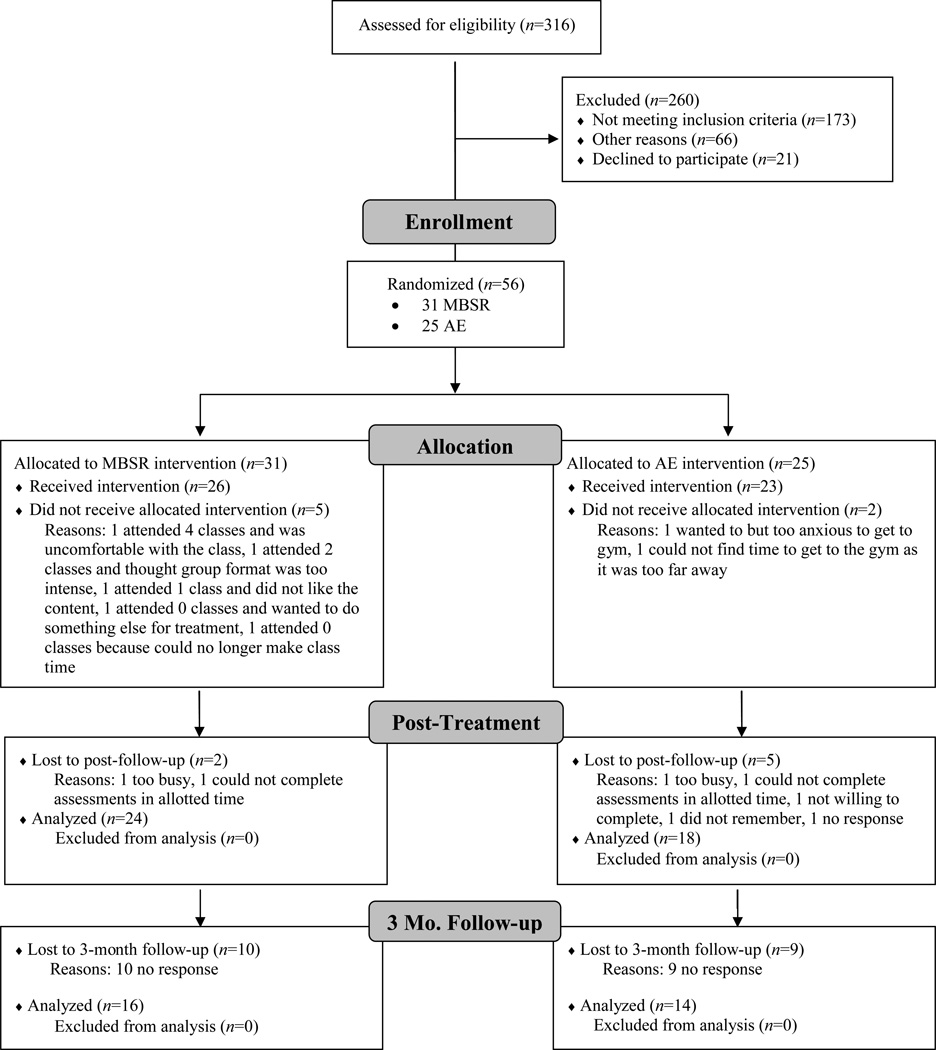

Seventy-seven potential participants met study inclusion criteria and were invited to participate. Twenty-one discontinued prior to randomization (16 failed to complete baseline assessments, two decided that SAD was not their primary problem, two were too depressed to participate, and one wanted psychotherapy). The remaining 56 participants were randomly assigned to either MBSR (n = 31) or AE (n = 25) (Figure 1). Groups did not differ in gender, age, ethnicity, education, current or past Axis-I comorbidity, past psychotherapy, or past pharmacotherapy (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram for Randomized Controlled Trial of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) versus Aerobic Exercise (AE)

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics for Individuals Randomized to Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) or Aerobic Exercise (AE) as Well as Untreated (UT) SAD Participants

| MBSR n = 31 |

AE n = 25 |

UT n = 29 |

F or χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females, n (%) | 19 (61.3%) | 10 (40%) | 13 (44.8%) | χ2=2.88 |

| Age (M years ± SD) | 32.87 ± 8.83 | 32.88 ± 7.97 | 32.34 ± 9.4 | F=0.04 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | χ2=0.43 | |||

| Caucasian | 13 (41.9%) | 10 (40%) | 14 (48.3%) | |

| Asian | 14 (45.2%) | 11 (44%) | 9 (31%) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (9.7%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (3.4%) | |

| Multiracial | 1 (3.2%) | 3 (12%) | 5 (17.2%) | |

| Education (M years ± SD) | 16.40 ± 2.00 | 16.84 ± 2.64 | 16.41 ± 1.76 | F=0.38 |

| Current Axis-I Comorbidity | χ2=4.88 | |||

| Generalized anxiety Disorder | 10 | 8 | 6 | |

| Major depressive disorder | 5 | 6 | 0 | |

| Dysthymia | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| Specific phobia | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Panic disorder | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Agoraphobia | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Past Axis-I Comorbidity | χ2=1.49 | |||

| Major depressive disorder | 9 | 2 | 5 | |

| Dysthymia | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Panic Disorder | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Substance Abuse | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Eating disorder | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Past psychotherapy | 15 | 9 | 11 | χ2=1.84 |

| Past pharmacotherapy | 7 | 5 | 12 | χ2=1.56 |

Nonrandomized Participants

Healthy Controls

To conduct clinical significance analyses (see below), normative data for all relevant measures were also obtained from a separate sample of 48 healthy controls (52.1% female; 56.3% Caucasian; Age (M ± SD): 33.9 ± 9.8) with no history of any psychiatric problems.

Untreated SAD Participants

A separate, untreated (UT) group of 29 adults who met DSM-IV criteria for a principal diagnosis of generalized SAD based on the ADIS-IV-L was included. This group was part of a separate randomized-controlled trial (Goldin et al., 2011). When compared with RCT participants, the untreated SAD group did not differ in gender, age, ethnicity, education, current or past Axis-I comorbidity, past psychotherapy or past pharmacotherapy (see Table 1). Potential participants were excluded for current pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy, history of medical disorders or head trauma, and current psychiatric disorders other than SAD, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia without a history of panic attacks, or specific phobia. The 29 individuals in this group were assessed at two time points (16 weeks apart) on the same measures as the RCT (MBSR and AE) groups.

Procedure

All participants were recruited through web-based community listings and referrals from mental health clinics and providers. Because this study was part of a larger neuroimaging study, participants were excluded for current pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy, history of medical disorders, or head trauma. Participants were also excluded for any current psychiatric disorders except principal diagnoses of SAD (operationalized as a score of ≥ 50 on the LSAS-SR, a score of 4 or more on the ADIS-IV-L Clinician’s Severity Rating for SAD, and ratings of 4 or higher for 5 or more specifically queried social/performance situations), generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, agoraphobia without a history of panic attacks, or specific phobia. Participants were excluded if they had previously completed an MBSR course, or if they had a regular meditation practice or exercise regime (regular was defined for our purposes as three or more times per week, for more than 2 months). An initial telephone screen and ADIS-IV-L were used to assess these inclusion criteria. Individuals with a principal diagnosis of generalized SAD were invited to participate in the study. Participants were randomized to 8 weeks of either MBSR or AE using the Efron biased coin randomization procedure. This method removes potential confounds related to unequal assignment at different time points over a multi-year study. All participants provided informed consent in accordance with Stanford University Human Subjects Committee rules.

For all MBSR and AE participants, weekly phone calls were made to monitor practice and address any obstacles to meditation practice or aerobic exercise. MBSR participants recorded weekly meditation practice (frequency and duration of formal and informal meditation practices), and AE participants recorded weekly exercise practice (frequency and duration of individual and group exercises). Participants completed measures of clinical symptoms and well-being (described below) pre- and post-interventions, and at 3-months post intervention, a subset of these measures were re-administered. Participants also completed the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Scale (KIMS; Baer, Smith, & Allen, 2004) pre- and post-intervention. The KIMS is a 39-item measure that examines four elements of mindfulness: observing, describing, acting with awareness, and accepting without judgment. The instrument has good internal consistency and validity (Baer, Smith, & Allen, 2004).

Interventions

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)

We administered the standard MBSR program (Kabat-Zinn, 1990) consisting of eight, weekly 2.5 hour group classes, a one-day meditation retreat, and daily home practice. Participants were trained in formal meditation practice (i.e., breath-focus, body scan, open monitoring), brief informal practice, and Hatha yoga. Forms to monitor daily meditation and yoga practice were collected each week. Participants attended MBSR courses offered by seven different teachers in eight healthcare settings throughout the San Francisco Bay Area who were unaware of participant’s clinical status. The MBSR instructors had 15.7 years (SD = 4.1 years, range = 10 - 20 years) of MBSR teaching experience.

Aerobic Exercise (AE)

We provided two-month gym memberships to participants randomized to AE. Participants were asked to select a public health club or gym that they would be willing to attend for the duration of the study. To match the individual and group components of MSBR, participants in the AE intervention were required to complete at least two individual aerobic exercise sessions (at moderate intensity) and one group aerobic exercise session (other than meditation or yoga) each week during the 8-week intervention. Intensity of exercise and heart rate were not monitored. Guidance using gym equipment was not directly provided (though available through health club/gym personnel).

Assessment Measures

The following measures of clinical and well-being symptoms were administered at preintervention, post-intervention, and at 3-months following the intervention, except where noted.

Measures of Clinical Symptoms

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale-Self-Report (Fresco et al., 2001)

The 24-item LSAS-SR, (which is highly correlated with the clinician-administered version (Baker, Heinrich, Kim, & Hoffman, 2002)) includes questions pertaining to social interaction and performance situations. The LSAS-SR have shown to have good convergent, discriminant validity, and reliability (Fresco et al., 2001). Internal consistency as measured by Cronbach’s alpha was good in all groups (MBSR = .90; AE = .90; HC = .92; UT = .89;).

Social Interaction Anxiety Scale Straightforward Scale (SIAS-S; Rodebaugh, Woods, & Heimberg, 2007)

The SIAS-S is a 17-item measure of social anxiety in a variety of social interaction situations including dyads and groups. The SIAS-S has demonstrated strong internal consistency and construct validity (Rodebaugh et al., 2007). Internal consistency was adequate in the current samples (MBSR = .81; AE = .88; HC = .90; UT = .83).

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996)

The BDI-II is 1 21-item assessment of depressive symptoms. The BDI-II has demonstrated high internal consistency in outpatient samples (Beck et al., 1996). Internal consistency was good in the current samples (MBSR = .94; AE = .91; HC = .84; UT = .94).

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983)

The PSS-4 is a 4-item brief version of the original PSS, the most widely used psychological instrument for measuring an individual’s perceptions of stress during the past month. In non-SAD clinical samples, the PSS has been shown to be internally consistent (Hewitt, Flett, & Mosher, 1992). In the present sample, internal consistency was good (MBSR = .88; AE = .78; HC = .64; UT = .81). This measure was not adminstered at the 3-month follow-up.

Measures of Well-being and Related Constructs

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965)

The RSES is a 10-item measure of self-esteem that includes five positive items and five negative items which are reversed scored. In general, the RSES has demonstrated good convergent validity and good test-retest reliability and in similar populations of adults with SAD, the RSES has demonstrated high internal consistency (Kuo, Goldin, Werner, Heimberg, & Gross, 2011). Internal consistency was adequate in the present samples (MBSR = .89; AE = .86; HC = .79; UT = .87).

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985)

The SWLS is a 5-item assessment of overall satisfaction with life as a whole, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction with life. Questions are global rather than specific in nature. The SWLS has exhibited high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity (Pavot & Diener, 2008). Internal consistency was adequate in the present samples (MBSR = .89; AE = .94; HC = .88; UT = .86).

Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff, 2003)

The SCS is a 26-item measure of self-compassion. The SCS has demonstrated strong convergent and discriminant validity, good test-retest reliability, and no correlation with social desirability (Neff, 2003; Neff, Rude, & Kirkpatrick, 2007). In a treatment seeking sample of adults with SAD, the SCS demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Werner et al., 2011). Internal consistency was good in current samples (MBSR = .88; AE = .87; HC = .93; UT = .90).

UCLA-8 Loneliness Scale (ULS-8; Hays & DiMatteo, 1987)

The ULS-8 is the short version of the ULS (Russell, 1996), the most widely used measure of loneliness or social isolation. In general, the ULS-8 has strong reliability and validity (Russell, 1996). For present purposes, the scores were reversed so that lower scores indicated greater social integration. Internal consistency was adequate in the samples (MBSR = .74; AE = .80; HC = .83; UT = .83). This measure was not adminstered at the 3-month follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Separate 2 (Group) × 2 (Time) repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) on measures of clinical symptoms and well-being were conducted based on (a) treatment completers and (b) the intent-to-treat (ITT) sample. For the ITT analysis, we used a standard conservative method in which the participant’s last observation was carried forward to account for missing data. Because the completer and ITT analyses yielded equivalent results, here we report only the completer analyses (results of the ITT analyses are available upon request).

We applied a modified Bonferroni correction to the measures in each domain to control for alpha inflation (Type I error). Significance was set at p < .05/4 = .0125. This correction is known to be conservative as it “over-corrects” the raw p values. Within-intervention effects were examined based on one-way repeated-measure ANOVAs. Partial eta-squared (ηp2) was calculated to assess effect sizes (ESs) for between-treatment comparisons of post-intervention outcomes. ESs were also calculated for each treatment condition to evaluate the magnitude of pre- to post-intervention change. Because there were no between-group differences at baseline on any measure (all ps > .15), no covariates were included in the analyses.

To assess the clinical significance of treatment-related changes, we used the methods described by Jacobson and colleagues (Jacobson, Roberts, Berns, & McGlinchey, 1999; 1991) to determine if treatment has moved a patient from the dysfunctional to functional range. Their method requires that two criteria be met. First, the Reliable Change Index (RCI) is used to determine whether the magnitude of change from baseline to post-treatment in each individual exceeds measurement error and therefore is a statistically reliable change. The formula for the RCI is: . For the reliability measure, we used the Cronbach’s alpha computed from data in our own healthy control (HC) sample, which is preferable to published coefficient alpha values. Second, the baseline to post-treatment change must shift the individual into the range of a well-functioning group. To determine a cut-off score for establishing clinically significant change, we used Jacobson et al.’s (1999) method C which determines whether an individual with SAD has moved to the healthy side of the halfway point between 2 SDs from the patient mean and 2 SDs from the healthy mean. Chi-squared analysis was conducted to determine whether the proportion of patients who had both statistically reliable change and clinically significant change differed following MBSR and AE. Meeting both criteria indicates that the patient had statistically reliable change and achieved normal functioning.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Five of 31 (16%) participants dropped from MSBR, and 2 of 25 (8%) participants dropped during AE, a nonsignificant difference, χ2 (1, N = 56) = 0.84, p = .36. Among treatment completers, 2 of 26 (7.7%) MBSR participants and 5 of 23 (21.7%) AE participants did not complete post-treatment assessments (Figure 1). The difference between groups in completion of post-treatment assessments was not significant (χ2 (1, N = 49) = 1.97, p = .16)). Among treatment completers, at 3-months post-intervention, 10 of 26 (38.5%) MBSR participants and 9 of 23 (39.1%) AE participants did not complete 3-month follow-up assessments. The difference between groups in completion of 3-month follow-up assessments was not significant (χ2 (1, N = 49) = .40, p = .53)). Between-group t-tests showed that the average amount of time committed to practice each week in the MBSR (M = 212, SD = 104 minutes) and AE (M = 196, SD = 86 minutes) groups did not differ (t(45) = 0.60, p > .55). Analyses of scores on the KIMS revealed no differences between MBSR and AE at baseline (t(53) = 0.09, p > .93). We also detected no group by time effect (F1,29 = 0.21, p > .65, ηp2 = .01): both interventions were associated with increased mindfulness (KIMSMBSR= F1,15 = 5.60, p > .03, ηp2 = .27 and KIMSAE = F1,12 = 5.13, p > .05, ηp2 = .34).

MBSR versus AE

Baseline to Post-Intervention

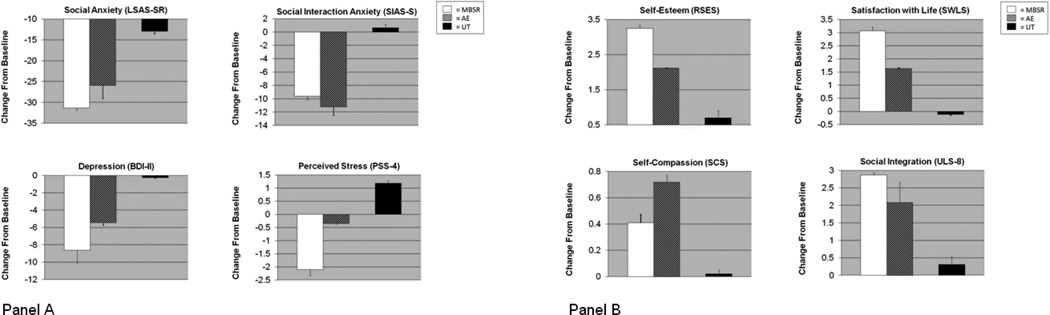

Separate 2 Group (MBSR, AE) × 2 Time (pre, post) repeated-measures ANOVAs resulted in no significant interactions of group by time for clinical (all ps > .16) or well-being (all ps > .33) measures. There were also no main effects of group for clinical (all ps > .11) or well-being (all ps > .28) measures. However, there were main effects of time indicating improvement on clinical measures of social anxiety symptom severity (LSAS-SR: F1,37 = 67.37, p < .001, ηp2 = .64; SIAS-S: F1,32 = 36.45, p < .001, ηp2 = .55), depression (BDI-II: F1,30 = 15.54, p < .001, ηp2 = .33), but not for perceived stress (PSS, p > .06). Main effects of time also were evident for well-being measures (RSES: F1,30 = 17.11, p < .001, ηp2 = .36; SWLS: F1,27 = 10.38, p < .01, ηp2 = .29; SCS: F1,20 = 16.56, p < .001, ηp2 = .44; ULS-8: F1,25 = 11.55, p < .01, ηp2 = .30) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Panel A. Changes from Pre- to Post-intervention on Measures of Clinical Symptoms; Panel B. Changes from Pre- to Post-intervention on Well-Being Measures

Note. MBSR = Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, AE = Aerobic exercise, UT = untreated SAD group, LSAS-SR = Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale Self-Report, SIAS-S = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale Straightforward, BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II, PSS-4 = Perceived Stress Scale 4-item, RSES = Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, SWLS = Satisfaction with Life Scale, SCS=Self-Compassion Scale, ULS-8 = UCLA Loneliness Scale inverse

Baseline to 3-Month Follow-up

Separate 2 Group (MBSR, AE) × 2 Time (pre, 3mo FU) repeated-measures ANOVAs resulted in no significant interactions of group by time for clinical (all ps > .17) or well-being (all ps > .17) measures. There were also no main effects of group for social anxiety clinical measures (all ps > .28) or well-being measures (all ps > .32). However, there was a main effect of group for depressive clinical symptoms (BDI-II: F1,25 = 7.50, p < .01, ηp2 = .23). Further, there were main effects of time indicating improvement on clinical measures of social anxiety symptom severity (LSAS-SR: F1,28 = 62.79, p < .001, ηp2 = .69; SIAS-S: F1,19 = 23.12, p < .001, ηp2 = .55), and depression (BDI-II: F1,25 = 16.63, p < .001, ηp2 = .40) (PSS was not assessed at the 3-month follow-up). Main effects of time also were evident for well-being measures (RSES: F1,22 = 9.06, p < .006, ηp2 = .28; SWLS: F1,17 = 23.52, p < .001, ηp2 = .57; SCS: F1,17 = 13.60, p < .002, ηp2 = .43; ULS was not assessed at the 3-month follow-up).

Clinical Significance

Clinical significance change RCI cut-off scores for clinical variables were derived as described above: LSAS-SR = 42.94, SIAS-S = 28.20, BDI-II = 4.47, and PSS-4 = 7.91. Based on these cut-offs, the percentage of participants meeting the threshold for clinical significance following MBSR and AE were: 22.5% vs. 29.5% for LSAS-SR, 25.2% vs. 23.6% for SIAS-S, 53.1% vs. 31.5% for BDI-II, and 36.4% vs. 21.3% for PSS-4. Chi-squared analyses determined that the between-groups difference in clinical significance was not statistically significant on any of the clinical measures (χ2: ps > .09). Cut-offs were also determined for well-being measures: RSES = 32.71, SWLS = 20.13, SCS = 2.9, ULS-8 = 18.54. The percentage of participants meeting the threshold for clinical significance following MBSR and AE was: 25% vs. 6.3% for RSES, 20.1% vs. 35.5% for SWLS, 35.5 % vs. 40.2 % for SCS, and 6.7% vs. 30.8% for ULS-8. Chi-squared analyses determined that the difference in clinical significance between the two groups was not statistically significant on any of the well-being measures (χ2: ps > .1).

RCT Groups Versus Untreated Comparison Group

Separate 2 (Group) × 2 (Time) repeated-measures ANOVAs were used to test whether compared to this separate untreated comparison group, MBSR and AE would result in significantly decreased clinical symptoms and increased well-being from pre- to post-intervention (Figure 2). When MBSR was compared to the untreated SAD comparison group, there were interactions of group by time on nearly all clinical measures, revealing decreased symptoms of social anxiety (LSAS-SR: t(44) = 4.52, p < .001, ηp2 = .20, SIAS-S: t(44) = 3.02, p < .005, ηp2 = .19) and perceived stress (PSS-4: t(27) = 2.92, p < .007, ηp2 = .23). After Bonferroni correction, change in depression was not significantly better for the MBSR group (p ≥ .03). Results indicated greater improvement on two of the well-being measures in the MBSR group: satisfaction with life (SWLS: t(28) = 2.72, p < .01, ηp2 = .20) and loneliness (ULS-8: t(30) = 2.25, p < .03, ηp2 = .14). After Bonferroni correction, differences in self-compassion and self-esteem were not significant (all ps ≥ .03). When AE was compared to the untreated SAD comparison group, group by time interactions indicated decreased clinical symptoms for social anxiety (SIAS-S: t(36) = 3.52, p < .001, ηp2 = .25) as well as improvement on self-compassion (SCS: t(28) = 4.19, and p < .001, ηp2 = .37). The remaining clinical (all ps > .07) and well-being measures (all ps > .17) were not significant.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the effects of a randomized controlled trial of MBSR versus AE on clinical symptoms and well-being in adults with generalized SAD. Both MBSR and AE resulted in reductions of clinical symptoms and enhanced well-being both immediately post intervention and at 3-month post intervention. There were no statistically significant differences between the two interventions.

Why Was AE as Effective as MBSR?

One possible explanation for the surprising efficacy of AE is that as it was implemented in our study, AE involved physical aerobic exercise and weekly attendance at the public gym with group classes. Aerobic exercise mimics many of the same bodily sensations elicited by anxiety reactions, such as increased heart rate, respiration, and perspiration (Broman-Fulks et al., 2004). It may be that AE led participants to evaluate their bodily responses differently (e.g., in a less threatening manner) than they had previously. In addition, repeated exposure to social stimuli at the gym may have resulted in habituation to social fear and changes in social cognitions (thus helping alleviate SAD symptoms). Many have argued that the efficacy of traditional treatments (such as CBT) can be attributed, at least in large part, to the exposure component (Rodebaugh, Holaway, & Heimberg, 2004). Further, others have alluded to exercise as a form of exposure in the context of other anxiety disorders (e.g., panic disorder; Marks, 1999). Additionally, the mere act of exercising (improving one’s physical health) may assist in decreasing negative judgments and enhancing one’s kindness towards oneself (self-compassion).

Comparing MBSR and AE to the Untreated SAD Group

When the RCT interventions (MBSR and AE) were compared to a separate, untreated, non-randomized, comparison SAD group, MBSR was more efficacious on clinical measures of social anxiety and stress, and on multiple well-being measures including satisfaction with life and social integration (depression and self-esteem were no longer significant after the Bonferroni correction). When AE was compared to the separate, untreated, non-randomized, comparison SAD group, AE was more efficacious on clinical measures of social anxiety and on the wellbeing measure of self-compassion. Since the MBSR, AE, and the untreated SAD group were not directly randomized as part of an RCT, strong inferences cannot be drawn; however, these results suggest that these interventions may be activating meaningful changes in clinical symptoms and well-being when compared to this untreated comparison SAD group.

Clinical Implications

Both MBSR and AE led to significant changes in clinical symptoms and well-being both immediately post intervention and at 3-month post intervention. Contrary to expectations, the magnitude of these effects was generally comparable for MBSR and AE. This research is important to continue exploring for several reasons. Individuals with SAD often underutilize mental health services (Magee, Eaton, Wittchen, McGonagle, & Kessler, 1996) and have a low-rate of help-seeking behavior (Stein & Kean, 2000), possibly due to the stigma associated with psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy interventions, the fear of negative evaluation, or the financial burden involved with treatment (Olfson et al., 2000). Further, compared to traditional treatments for SAD, for some, MBSR and AE be more accessible, less costly, and less associated with stigma (Otto et al., 2007). Additionally, MBSR and AE may be important adjunctive interventions rather than standalone interventions for individuals who do not fully respond to traditional treatments; this possibility should be further explored.

Recent reviews have suggested that exercise may be an effective adjunct to clinical interventions (Stathopoulou, Powers, Berry, Smits, & Otto, 2006) and treatment manuals utilizing exercise for mood and anxiety disorders have been created (e.g., Smits & Otto, 2009). Acute aerobic exercise has been associated with a reduction in state anxiety and an improvement in subjective well-being (Knapen et al., 2009). Previous studies have shown that different forms of physical exercise in combination with standard anxiety treatments (e.g., group CBT) help reduce anxiety, depression, and stress symptoms (Merom et al., 2008). Additional studies that directly compare CBT to MBSR (e.g., Koszycki et al., 2007) as well as studies that determine whether there is an additive effect of MBSR or AE when combined with CBT are warranted.

Approximately a quarter of our participants demonstrated clinically significant change on social anxiety symptoms immediately following the interventions. While promising, this suggests that about three-quarters of our participants did not achieve levels of social anxiety in the range of our non-anxious healthy controls. This is lower than what has been found in previous studies (ranges from 31-75%) of individuals with SAD (e.g., Borge et al., 2008; Heimberg et al., 1990). One possible explanation is that the healthy control group utilized in this study is more “normal” than typical normal control groups. This is likely due to the stringent screening procedures and strict exclusion criteria from the healthy control group for (current or past) diagnoses that would typically be present in a meaningful percentage of the “normal” population. Nevertheless, the fact that such a large percentage of participants with SAD continued to experience clinically significant social anxiety symptoms after the interventions indicates that refinement and exploration of these alternative interventions for individuals with SAD is needed before these can be recommended as standalone interventions.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study of MBSR was the first to use aerobic exercise as an active comparison intervention. One strength of this study was that separate from the direct RCT (MBSR and AE), it was possible to use an SAD untreated condition when examining the effects of these two interventions. In future studies, it will be important to directly randomize participants to a waitlist condition when examining these two interventions so that direct inferences can be made. Any apparent differences between groups may be due to the relative amount of group experience (i.e., time) entailed in each intervention. Having to face social fears related to being in a group setting and interacting with others in the MBSR intervention may have provided more opportunities to overcome social anxiety. Future research is needed to address whether these two interventions operate via different mechanisms as results may have important clinical implications.

Both interventions had acceptable dropout rates (AE = 8%, MBSR = 16%). The MBSR dropout rate is comparable to the 15.9% reported in Koszycki et al.’s (2007) study of SAD, and the AE dropout rate is comparable to the 11% reported in Martinsen et al.’s (1989) aerobic exercise study of adults with anxiety disorders. On average, participants in both groups completed 3.4 hours of weekly practice. The amount of time spent practicing in MBSR and AE suggests that the two programs were well tolerated by participants. Future research may benefit from gathering explicit participant evaluation of the intervention and instructor. Further, adherence of MBSR instructors and treatment integrity must be kept in order to ensure efficacy. In addition to total number of minutes of aerobic exercise per week, future studies should gather information on intensity and minutes per each exercise session. This information will allow for inferences regarding the effectiveness of aerobic exercise as an intervention. Such information could be useful to test potential predictor or moderators of intervention effects.

In the present study, MBSR and AE led to meaningful changes in SAD. To better understand the mechanisms of change, future research should explore the mediators and moderators of MBSR and AE. Understanding the mechanisms responsible for AE- and MBSR-related improvements will allow us to better understand why these unconventional interventions yield some unexpected clinically meaningful changes and help address treatment specificity. Future studies will benefit from including non-self report measures including experimental tasks, daily experience sampling, biomarkers, and longer-term assessment of training effects (beyond the 3-month period that was examined in this study).

This study required participants to voluntarily contact us to partake in the study (an exposure in itself), and all interventions were offered in outpatient settings. It is possible that participants in this study were less severe in their social anxiety symptoms and therefore may not be representative of more severe, treatment seeking or clinically referred populations. In future studies, it will be important to include a broader range of SAD symptom levels, as well as other psychiatric conditions so that results may be more generalizable.

Finally, this study examined two alternative interventions for adults with SAD. These interventions were well-accepted and produced modest clinically significant changes, however, not at the same level as has been found in previous studies with traditional treatments (e.g., Heimberg et al., 1990). While it is possible that individuals in MBSR and AE spontaneously remitted to the same degree, the chronicity of SAD and the indirect evidence provided by comparison to the untreated SAD group suggest that future research should continue to explore alternative interventions such as MBSR and AE for SAD. Future research may benefit from examining the potential enhancement of treatment outcome with a combination of MBSR and AE, or the addition of MBSR or AE to traditional for treatments for SAD. Although traditional treatments are the preferred choice due to the empirical support for their efficacy, clinicians and researchers should continue to explore alternative methods which may assist in facilitating help-seeking behavior and reduce barriers to treatment access for individuals suffering from SAD.

Table 2.

Clinical Symptoms and Well-Being for Patients in the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Aerobic Exercise (AE), Healthy Control (HC), and Untreated (UT) Groups

| Measure | Group | Pre Mean (SD) |

Post Mean (SD) |

3 Month FU Mean (SD) |

Pre vs. Post F, p, effect size |

Pre vs. 3 mo FU F, p, effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLINICAL SYMPTOMS | ||||||

|

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (Self-report) |

MBSR | 86.82 (20.91) | 55.50 (18.52) | 55.56 (16.76) | 64.32, .001, .75 | 31.71, .001, .68 |

| AE | 87.38 (16.06) | 61.41 (28.64) | 54.86 (25.09) | 16.43, .001, .51 | 30.77, .001, .70 | |

| UT | 78.37 (18.04) | 65.42 (21.37) | 12.02, .001, .33 | |||

| HC | 15.50 (11.30) | |||||

|

Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (Straightforward Items) |

MBSR | 43.50 (9.85) | 33.88 (7.66) | 29.91 (7.38) | 10.27, .006, .41 | 13.82, .004, .58 |

| AE | 45.81 (9.05) | 34.56 (14.10) | 27.80 (14.83) | 19.18, .002, .49 | 10.36, .01, .54 | |

| UT | 42.42 (10.19) | 43.04 (12.57) | .11, .75, .01 | |||

| HC | 13.40 (8.60) | |||||

| Beck Depression Inventory-II | MBSR | 13.94 (11.46) | 5.29 (5.30) | 4.73 (4.89) | 11.83, .003 .43 | 6.94, .02, .33 |

| AE | 16.40 (7.84) | 10.93 (8.88) | 9.17 (6.77) | 4.28, .058, .23 | 9.53, .01, .46 | |

| UT | 13.32 (10.25) | 13.05 (10.60) | .01, .92, .01 | |||

| HC | 1.60 (2.80) | |||||

| Perceived Stress Scale | MBSR | 10.00 (2.40) | 7.90 (1.66) | -- | 5.30, .047, .37 | -- |

| AE | 10.17 (3.01) | 9.83 (2.89) | -- | .17, .69, .02 | -- | |

| UT | 9.43 (2.93) | 10.62 (3.37) | 3.40, .08, .15 | |||

| HC | 6.50 (2.00) | |||||

| WELL-BEING | ||||||

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | MBSR | 24.56 (3.46) | 27.81 (3.82) | 27.85 (5.15) | 15.18, .001, .50 | 6.95, .02, .37 |

| AE | 23.69 (4.60) | 25.81 (4.59) | 27.17 (4.76) | 4.48, .05, .23 | 3.34, .01, .23 | |

| UT | 23.05 (5.52) | 23.75 (6.44) | .80, .38, .04 | |||

| HC | 35.20 (3.80) | |||||

| Satisfaction with Life Scale | MBSR | 14.00 (4.26) | 17.07 (4.78) | 17.27 (3.61) | 10.29, .007, .44 | 9.72, .01, .49 |

| AE | 14.00 (6.30) | 15.64 (6.32) | 16.11 (7.01) | 2.37, .15, .15 | 12.68, .007, .61 | |

| UT | 15.33 (6.18) | 15.22 (6.29) | .02, .89, .01 | |||

| HC | 21.80 (4.40) | |||||

| Self-Compassion Scale | MBSR | 2.27 (.63) | 2.68 (.45) | 2.89 (.63) | 1.70, .23, .20 | 4.37, .07, .38 |

| AE | 2.10 (.46) | 2.82 (.64) | 2.97 (.67) | 22.71, .001, .64 | 10.46, .008, .49 | |

| UT | 2.21 (.60) | 2.23 (.72) | .02, .89, .01 | |||

| HC | 3.60 (.60) | |||||

| UCLA Loneliness Scale | MBSR | 25.07 (2.79) | 22.20 (3.03) | -- | 9.60, .008, .41 | -- |

| AE | 24.85 (3.58) | 22.77 (5.63) | -- | 2.99, .11, .20 | -- | |

| UT | 23.68 (4.73) | 23.37 (5.69) | .21, .65, .01 | |||

| HC | 12.70 (3.70) | |||||

Note. SD = standard deviation, effect size = partial eta squared (ηp2).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Richard Heimberg for his helpful comments on this manuscript. This research was supported by NIMH Grant MH76074 and NCCAM Grant AT003644 awarded to James Gross.

Footnotes

Portions of this work were presented at the November 2010 meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, San Francisco, CA.

The authors of this manuscript do not have any direct or indirect conflicts of interest, financial or personal relationships or affiliations to disclose.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Allen KB. Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: The Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills. Assessment. 2004;11:191–206. doi: 10.1177/1073191104268029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SL, Heinrich N, Kim H-J, Hoffman SG. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale as a self-report instrument: A preliminary psychometric analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:1087–1098. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Birnie K, Speca M, Carlson L. Exploring self-compassion and empathy in the context of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) Stress and Health. 2010;26:359–371. [Google Scholar]

- Bögels SM, Sijbers GFVM, Voncken M. Mindfulness and task concentration training for social phobia: A pilot study. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;20:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Borge FM, Hoffart A, Sexton H, Clark DM, Markowitz JC, McManus F. Residential cognitive therapy versus residential interpersonal therapy for social phobia: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:991–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman-Fulks JJ, Berman ME, Rabian BA, Webster MJ. Effects of aerobic exercise on anxiety sensitivity. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:125–136. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broocks A, Bandelow B, Pekrun G, George A, Meyer T, Bartmann U, Rüther E. Comparison of aerobic exercise, clomipramine, and placebo in the treatment of panic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:603–609. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, DiNardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairney J, McCabe L, Veldhuizen S, Corna LM, Streiner D, Herrmann N. Epidemiology of social phobia in later life. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15:224–233. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000235702.77245.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measures of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordon SL, Brown KW, Gibson PR. The role of mindfulness-based stress reduction on perceived stress: Preliminary evidence for the moderating role of attachment style. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 2009;23:258–269. [Google Scholar]

- Cox BJ, Fleet C, Stein MB. Self-criticism and social phobia in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigie MA, Rees CS, Marsh A. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary evaluation. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;36:553–568. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime version (ADIS-IV-L) New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dratcu L. Physical exercise: An adjunctive treatment for panic disorder? European Psychiatry. 2001;16:372–374. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(01)00593-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Ferrando S, Findler M, Stowell C, Smart C, Haglin D. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:716–721. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Coles ME, Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hami S, Stein MB, Goetz D. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: A comparison of the psychometric properties of self-report and clinician-administered formats. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:1025–1035. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion. 2010;10:83–91. doi: 10.1037/a0018441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Ramel W, Gross JJ. Mindfulness meditation training and self-referential processing in social anxiety disorder: Behavioral and neural effects. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;23:242–257. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.23.3.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Werner K, Ziv M, Jazaieri H, Luce K, Hill K, Gross JJ. Cognitive Reappraisal Mediation of Individual Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0028555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;57:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, DiMatteo MR. A short-form measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1987;51:69–81. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Dodge CS, Hope DA, Kennedy CR, Zollo LJ, Becker RE. Cognitive behavioral group treatment for social phobia: Comparison with a credible placebo control. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990;14:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Herring MP, O'Connor PJ, Dishman RK. The effect of exercise training on anxiety symptoms among patients. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170:321–331. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Mosher SW. The Perceived Stress Scale: Factor structure and relation to depression symptoms in a psychiatric sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1992;14:247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:169–183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Roberts LJ, Berns SB, McGlinchey JB. Methods for defining and determining the clinical significance of treatment effects: Description, application, and alternative. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:300–307. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York: Delacorte; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J, Massion AO, Kristeller J, Peterson LG. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:936–943. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PD, Demler O, Olga JR, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YW, Lee SH, Choi TK, Suh SY, Kim B, Kim CM, Yook KH. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy as an adjuvant to pharmacotherapy in patients with panic disorder or generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:601–606. doi: 10.1002/da.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapen J, Sommerijns E, Vancampfort D, Sienaert P, Pieters G, Haake P, Peuskens J. State anxiety and subjective well-being responses to acute bouts of aerobic exercise in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009;43:756–759. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.052654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocovski NL, Fleming JE, Rector NA. Mindfulness and acceptance-based group therapy for social anxiety disorder: A pilot study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2009;16:276–289. [Google Scholar]

- Koszycki D, Benger M, Shlik J, Bradwejn J. Randomized trial of a meditation-based stress reduction program and cognitive behavior therapy in generalized social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2518–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JR, Goldin PR, Werner K, Heimberg RG, Gross JJ. Childhood trauma and current psychological functioning in adults with social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Ahn SC, Lee YJ, Choi TK, Yook KH, Suh SY. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress management program as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy in patients with anxiety disorder. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2007;62:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–173. doi: 10.1159/000414022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee WJ, Eaton WW, Wittchen HU, McGonagle KA, Kessler RC. Agoraphobia, simple phobia and social phobia in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:159–168. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830020077009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks I. Treatment of panic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1129–1130. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.7.1129a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen E, Hoffart A, Solberg Ø. Comparing aerobic with nonaerobic forms of exercise in the treatment of clinical depression: A randomized trial. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1989;30:324–331. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(89)90057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEntee DJ, Halgin RP. Cognitive group therapy and aerobic exercise in the treatment of anxiety. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 1999;13:39–58. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre LM, Martin ER, Simonsen KL, Kaplan NL. Circumventing multiple testing: A multilocus Monte Carlo approach to testing for association. Genetic Epidemiology. 2000;19:18–29. doi: 10.1002/1098-2272(200007)19:1<18::AID-GEPI2>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merom D, Phongsavan P, Wagner R, Chey T, Marnane C, Steel Z, Bauman A. Promoting walking as an adjunct intervention to group cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: A pilot group randomized trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;22:959–968. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Fletcher K, Kabat-Zinn J. Three-year follow-up and clinical implications of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention in the treatment of anxiety disorders. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1995;17:192–200. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(95)00025-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch DA. What is the core fear in social phobia? A new model to facilitate individualized case conceptualization and treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2009;16:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2003;2:223–250. [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Rude SS, Kirkpatrick K. An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41:908–916. [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Guardino M, Struening E, Schneier FR, Hellman F, Klein DF. Barriers to the treatment of social anxiety. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:521–527. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Church TS, Craft LL, Smits JAJ, Trivedi MH, Greer TL. Exercise for mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;9:287–294. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v09n0406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W, Diener E. The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2008;3:137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Penedo FJ, Dahn JR. Exercise and well-being: A review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2005;18:189–193. doi: 10.1097/00001504-200503000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruzzello SJ, Landers AC, Hatfield BD, Kubitz KA, Salazar W. A meta-analysis on the anxiety-reducing effect of acute and chronic exercise: Outcomes and mechanisms. Sports Medicine. 1991;11:143–182. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199111030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontoski K, Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Coles ME. Psychotherapy for social anxiety disorder. In: Stein D, Hollander E, Rothbaum B, editors. American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of anxiety disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 2010. pp. 501–521. [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Holaway RM, Heimberg RG. The treatment of social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:883–908. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Woods CM, Heimberg RG. The reverse of social anxiety is not always the opposite: The reverse scored items of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale do not belong. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:192–206. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. The UCLA Lonelieness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;66:20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: A unifying theory. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:33–61. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Smits JA, Berry AC, Rosenfield D, Powers MB, Behar E, Otto MW. Reducing anxiety sensitivity with exercise. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25:689–699. doi: 10.1002/da.20411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JAJ, Otto MW. Exercise for mood and anxiety disorders: Therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulou G, Powers MB, Berry AC, Smits JAJ, Otto MW. Exercise interventions for mental health: A quantitative and qualitative review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Kean YM. Disability and quality of life in social phobia: Epidemiologic findings. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1606–1613. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Edwards S, Moses J, Mathews A. The effects of exercise training on mood and perceived coping ability in anxious adults from the general population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1989;33:537–547. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(89)90061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stich FA. A meta-analysis of physical exercise as a treatment for symptoms of anxiety adults from the general population. Psychosomatic Research. 1998;33:537–547. [Google Scholar]

- Ströhle A. Physical activity, exercise, depression and anxiety disorders. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2009;116:777–784. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vøllestad J, Sivertsen B, Nielsen GH. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for patients with anxiety disorders: Evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;9:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelvemonth use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner K, Jazaieri H, Goldin PR, Ziv M, Heimberg RH, Gross JJ. Self-compassion and social anxiety disorder. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 2011 doi: 10.1080/10615806.2011.608842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]