Abstract

This paper describes the process of developing a parallel intervention for HIV-positive mothers and their young children (6-10 years) with a view to strengthening the relationship between them. Strong mother-child relationships can contribute to enhanced psychological resilience in children. The intervention was developed through action research, involving a situation analysis based on focus group discussions; intervention planning, piloting the intervention and a formative evaluation of the intervention. Participants supplied feedback regarding the value of the intervention in mother-child relationships. The findings obtained from the formative evaluation were used to refine the intervention. Two parallel programmes for mothers and children (15 sessions each) were followed by 10 joint sessions. The intervention for mothers focused on maternal mental health and the strengthening of their capacity to protect and care for their young children. The intervention for children addressed the development of their self-esteem, interpersonal relationships and survival skills. The formative evaluation provided evidence of good participation, support and group cohesion. Qualitative feedback indicated that the activities stimulated mother-child interaction. A similar intervention can easily be applied elsewhere using the detailed manual. The insights gained and lessons learnt related to mother and child interaction within an HIV-context that emerged from this research, can be valuable in other settings, both in Sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere.

Keywords: HIV-affected children, resilience, maternal mental health, parenting skills, formative evaluation

The AIDS pandemic in Sub-Saharan Africa has dire consequences for both the present and the next generations. Caring for HIV-positive parents and/or losing a parent to HIV/AIDS have long-lasting social and psychological effects on young children (Richter, Manegold & Pather, 2004). Like children who have experienced war, children living in a household affected by AIDS may continue to have psychological difficulties in adulthood and experience deficits in their own parenting of the next generation. HIV/AIDS displays characteristics that make it unique in its potential effects on children. Both parents may be infected, facing illness and death. HIV-prevalence in populations that are already plagued by multiple adversities such as poverty is devastating to children. The stigma associated with AIDS often isolates affected families and prevents them from accessing formal and informal support (Campbell, Foulis, Maimane & Sibiya, 2005; Ogden & Nyblade, 2005; Parker & Aggleton, 2003).

Various studies have provided evidence that (particularly maternal) HIV in the family compromises the healthy development of children (Forehand et al., 1998; Hough et al., 2003; Reyland, McMahon, Higgins-Delessandro & Luther, 2002; Richter, 2004; UNICEF, 2008). The negative impact on children'ss health can be due to increased poverty (Evans, 2005; Nattrass, 2005; Steinberg et al., 2001); lower levels of school attendance while taking on family responsibilities (Bennell, 2003; Evans, 2005; Nelson Mandela Foundation, 2005; Steinberg et al., 2001; UNICEF, 2000); family isolation due to stigma (Campbell et al., 2005; Ogden & Nyblade, 2005; Strode & Barrett-Grant, 2001) and shortfalls in parental care (Dutra et al., 2000; Hough et al., 2003; Kelly et al., 2002; Reyland et al., 2002; Richter, 2004; Rosa & Lehnert, 2003). There is strong evidence that the quality of parenting mediates child development outcomes among HIV-affected children (Bauman et al., 2006; Brandt, 2005; Nöstlinger et al., 2006; UNICEF, 2008). Based on a review of the literature, Brandt (2005) concluded that children of HIV-infected mothers tend to receive lower levels of protective support than children of non-infected mothers. Chandon and Richter (2009) argue that compromised parenting, mediated by poor maternal mental health, may have the most prominent negative effect on childrens's development. Brandt (2005) confirmed this by reporting that parental support is experienced as more protective than extra-familial support. Supporting the HIV-infected mother to be a good parent can therefore benefit the children. These findings show that interventions to mitigate the impact of the epidemic on children and build their resilience should be multi-faceted. Among various possible community and economic interventions, what seems essential is attention to maternal mental health and capacity to protect and care for HIV-affected children, in addition to a focus on childrens's coping behaviour (Hosegood, 2009; Richter et al., 2009; UNAIDS/UNICEF, 2004).

The need for interventions to assist both children affected by HIV/AIDS and their families is recognised widely. Despite this, UNICEF (2008, p. 69) concluded after an extensive literature search that “evidence about interventions to address the psychosocial challenges for children affected by HIV/AIDS is severely lacking, especially in low and middle income countries”. King et al. (2009) also conducted a literature review of 1038 citations referring to various kinds of interventions aiming at improving the psychosocial well-being of HIV-affected children, but found that only 11 of these studies described an intervention actually administered to children. None of these interventions were rigorously evaluated to enable conclusions about their effectiveness. The 11 identified interventions seemed to target the well-being and development of the child in isolation, ignoring the well-being of the mother as primary caregiver and the interaction between mother and child. Existing child-centred interventions (e.g. Mallmann, 2003) were not regarded as appropriate for young African children (aged 6 to 10 years) whose mothers have not disclosed their HIV status to their children.

In this paper we describe the development, piloting and formative evaluation of a mother and child intervention. Although the purpose of our involvement was to improve not only the well-being of mother and child but also the interaction between them, our ultimate aim was to promote the resilience of young children affected by HIV. Resilience refers to a dynamic process of positive adaptation despite adversity (Luthar, Cicchetti & Becker, 2000) and involves personal characteristics such as optimism, active problem solving, internal locus of control, higher sense of self-esteem, and realistic expectations of the self and the personal environment (Cowen, Wyman, Work & Parker, 1990; Rutter, 1990). It encompasses social resilience (Evans, 2005) through contextual variables such as security in family relationships, social connectedness through social networks and a supportive community climate (Dutra et al., 2000; Eloff et al., 2007; Vinson, 2000; Wright & Lopez, 2005). The goal of our intervention was to strengthen existing character traits of the children and to enhance positive mother-child interaction that could prepare children to deal with the challenges related to HIV in their family context.

Research Process

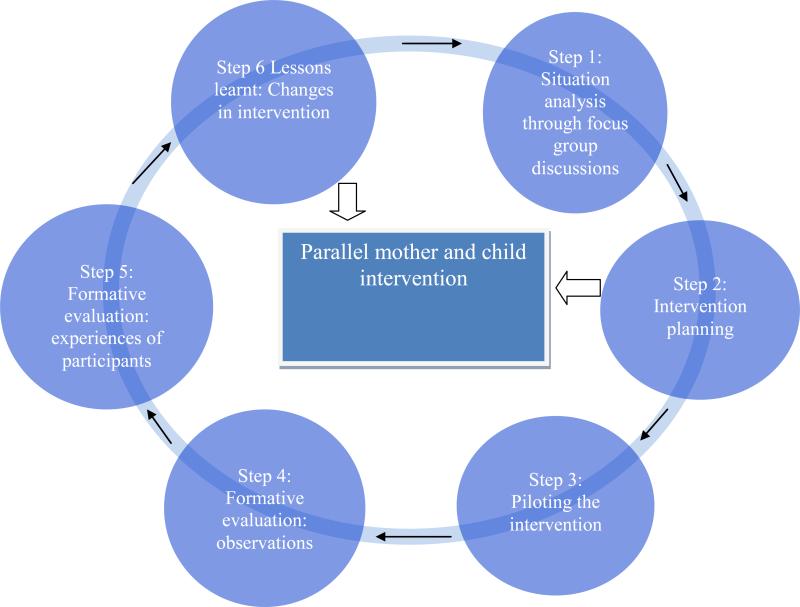

An action research approach was used to develop an intervention that would most likely be effective in meeting the needs of children of HIV-infected mothers. Action research involves bringing about change through a repeated cycle of planning, action, observation and reflection based on the participation of the target group (McNiff, 2010). The development of the intervention requires the following steps: 1) conducting a situation analysis through focus group discussions to understand the parenting context in this community and assess the needs of HIV-affected children; 2) planning the intervention; 3) piloting the implementation of the intervention; 4) conducting a formative evaluation using observations; 5) conducting a follow-up focus group discussion with participants to determine the value of the intervention, and 6) using findings of the formative evaluation to improve the intervention for further implementation and outcome evaluation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Action research process

Seeing that each step of the research process is built on the findings of the previous step, the different steps will be described in chronological order, including methods used and findings for each step. The development of the intervention formed part of a larger study for which review board approval had been obtained from the University of Pretoria's Faculty of Education and the Human Investigation Committee of Yale University's School of Medicine, USA.

The research process started with a situation analysis and needs assessment which provided an understanding of the context within which the intervention had to be developed.

Step 1: Situation analysis through focus group discussions

To explore child-raising practices and the needs of HIV-positive mothers and their children, we facilitated three focus group discussions involving 45 HIV-positive mothers, 15 in each group. A purposively selected sample of women was recruited from a regional public hospital that provides antiretroviral treatment (ART). The hospital provides services to a large, mainly black, very low to middle socio-economic class urban population. We requested HIV-counsellors working at the hospital to identify women who had known their HIV status for more than a year, were on ART and had children between the ages of six and ten years old. The counsellors informed the women of the research and invited them to participate in the focus group discussions. Those who agreed to participate voluntarily signed consent forms before the focus groups started.

The purpose of the focus group discussions was to identify specific needs experienced by HIV-positive mothers and their children and to explore child-raising practices in the cultural context. Guiding questions focused on 1) the challenges experienced by parents of young children; 2) the challenges generally experienced by children in growing up and the strategies they employ in coping with these challenges; 3) the challenges facing HIV-positive mothers in raising children, and 4) the way in which children were coping with their parents' HIV status or ill health.

A nurse who was part of the research team conducted the focus group discussions in IsiPedi, the language spoken most often in the area. The discussions (lasting between one and two hours) were tape recorded, transcribed and translated into English and integrated with the notes of research assistants who had been present during the discussions. An interpretive thematic analysis (Lyons & Coyle, 2007) was done by two researchers who identified recurring themes and needs that could be addressed in the intervention.

Themes that emerged from the focus group discussions

The themes identified from the focus group discussions were classified into four main areas: the needs experienced by the mother; concerns about disclosing her HIV status to her children; childrens's reaction to the health status of their mother; and needs of the children.

Needs experienced by the mother

Lack of financial resources

Most of the mothers were not working and indicated that they were financially dependent on partners, family members or disability and child-related grants. They had difficulty keeping children in school, paying school fees and buying school uniforms. The lack of financial resources contributed to a sense of helplessness in some of the women.

Concerns about their children's future

: The mothers indicated that their biggest concern was their childrens's future. Most of the women stayed with their children with members of the extended family, while about a quarter of the women had long-term sexual partners. They were scared that their children would be a burden to family members, would not be treated well, or might also become infected with HIV. One mother said: “I am scared no one will take care of my children and they will land up in the street.” They wanted to prepare their children for life while they still could, for example: “I want to plan for them, guide them to make proper choices so that they can stand on their own two feet.”

Need for assistance with parenting

: Many of the mothers experienced their children as disobedient and did not know how to deal with negative behaviour such as rebelliousness and aggression. Most of them disciplined their children by shouting at them or restricting them. They indicated that they needed help in disciplining their children. They also wanted to foster kind and open relationships with their offspring and hence needed guidance in developing appropriate communication styles.

A wish to live positively

When asked about the negative effects of HIV on themselves and their family life, the women indicated that they feared being rejected by family members, but that they wanted to cope better with HIV and learn to live positively for their childrens's sake. One woman said: “People must stop talking of death. If you focus on death you won't achieve a lot of things. HIV does not kill, just take care of yourself and face life.”

Concerns of the mother about disclosing her HIV status to her children

Disclosure of their HIV status was difficult for all the women. Although most of them had disclosed their status to at least one other person, only a few (about 20%) had disclosed it to their children. These women decided to disclose their status because they wanted to raise their (predominantly older) childrens's awareness of HIV or to explain to them why they were ill and were using medication. One mother said: “We should tell them before we get very ill. You should talk about it constantly and they will see that you are living a positive life. It should click in their minds even if they hear things in the streets.” Some of the mothers observed that their disclosure caused a burden to their children, as the children reacted with shock and sadness, and even their schoolwork suffered. These children were afraid that their mothers were dying. The mothers reported that despite the initial shock, disclosure almost invariably resulted in a closer relationship with their children. The latter became more supportive and took better care of parents when they were not well.

The majority of women in this study (about 80%) indicated that they had decided not to disclose their HIV status to their children. They felt their children were too young and did not understand what HIV was, or they wished to protect the children from the emotional consequences of being stigmatised. A mother explained: “At an early age it confuses the children. They will think that you are going to die.” Other reasons for not disclosing their status included that some mothers were scared that the children would tell others, or that the children would reject them and not provide support or feel sorry for them. Even when they had not disclosed their status to their children, mothers knew that their children were aware of their illness.

Childrens's reaction to the health status of their mother

Despite the fact that only a few mothers had disclosed their HIV status to their children, the mothers reported that their children were directly affected by their illness. Children often reminded their mothers to take their medication. When mothers became ill, children would often take care of them and assume household duties such as doing the laundry, preparing food or looking after the younger children, even if they had to stay out of school. One mother said: “My child stays out of school to take care of me. She cooks and cleans. Although she is back in school now, she is still behind.” The mothers observed that their children were worried about them and were saddened when they were ill; they did not want to play and stayed close to their mothers. One mother said: “He always wants to be around me to make sure that I am okay.” Older children often take on more responsibility, like insisting on taking the mother to the doctor or giving them medication. The childrens's emotional response to their mothers' illnesses and possible death is exemplified in the following quote: “My daughter said that she will sit by my grave so that she can be near me.”

Childrens's needs

Mothers identified the childrens's needs according to their levels of development. Smaller children reportedly needed to develop survival skills such as making sandwiches, washing their socks and polishing their shoes. They also needed to be able to do their homework when an adult was not available to help. Mothers were concerned about older childrens's negative emotions such as aggression, their social interaction with peers and the need for self-discipline to make the right choices. Many of the mothers indicated that their children do not talk about their problems. They wanted their children to be informed about HIV and ways of protecting themselves from the virus.

Step 2: Intervention planning

The research team structured the intervention by using relevant literature on resilience theory (Cowen et al., 1990; Rutter, 1990; Werner & Smith, 1992). They considered developmental tasks for children aged 6 to 10 years (Santrock, 2008), as well as needs identified during the focus group discussions. The intervention was educational and presented in groups in a semi-structured workshop format to encourage group participation and experiential learning through games, roleplays, exercises, storytelling, case studies and the sharing of experiences, feelings and ideas. Existing work on resilience in children affected by HIV/AIDS (Mallmann, 2003) was used as a resource for some of the activities for children. Material developed during a previous intervention in the same area and by the same research team (Visser et al., 2005) was used to design the intervention aimed at the mothers.

Two programmes were developed, one for mothers (15 sessions) and one for children (15 sessions). The programmes were implemented separately but in parallel. This was followed by 10 joint sessions to facilitate mother-child interaction. The rationale for developing a lengthy programme of 25 sessions was to assist the mother in coming to terms with her diagnosis and strengthen her parenting skills, while assisting the children to develop life skills. This was followed by the integration of these skills into a coherent skills set by facilitating mother-child interaction (see Table 1 for programme outline).

| MOTHER'S SESSIONS | CHILDREN'S SESSIONS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction, group norms, building relationships of trust | 1 | Let's get to know one another (Group rules, building trust) |

| 2 | How to look after myself: Living positively with HIV (Basic HIV/AIDS information, treatment options) | 2 | Developing relationships in the group (Develop trust , group cohesion, sharing happy feelings) |

| 3 | How do I feel: Emotional experience of HIV (Draw life maps and share personal stories of HIV) | 3 | Who am I? (Knowing yourself as part of family and community; body mapping; family drawing; family values; asset mapping) |

| 4 | 4 | ||

| 5 | How do I cope: Coping, problem solving and stress management (identify problem-focused and emotion-focused coping, relaxation) | 5 | I have, I am, I can (Identifying personal strengths; understanding family interaction ) |

| 6 | How do I disclose my status? (Share experiences of disclosure, advantages, obstacles, role play, how to deal with stigma) | 6 | What can I do? / What am I good at? (create strengths map; learn to cope with specific stressors through puppet play) |

| 7 | HIV in intimate relationships (negotiating condom use, gender roles, power relationships, women's position in society). | 7 | How can I do it? (Problem solving skills, solve problems through story telling) |

| 8 | HIV in the household (how to protect family members, communication, human rights, understanding and dealing with stigma.) | 8 | Protecting myself (Develop sense of safety, personal boundaries, children's rights, saying no when unsafe, safety board game). |

| 9 | Knowing myself as a parent (Parenting styles, how to take good care of child, listening). | 9 | Socializing with peers (Learn social skills - respect, acceptance, friendship- through story telling) |

| 10 | Knowing myself as a parent (Disciplining skills, role play difficult scenarios, how to help child to deal with problems) | 10 | How do I feel? (Identify, understanding and expressing own emotions, play board game) |

| 11 | Knowing myself as a parent (Nurturing parent, understanding children's feelings, enhance child's independence and self-esteem) | 11 | How do others feel? (Identify emotions of other people, how to respond, express scenarios through puppet play) |

| 12 | Knowing my child (Developmental tasks of children 0-18 years, what children need to be resilient, external and internal assets, how to deal with difficult scenarios) | 12 | Survival skills (Learn to help with household tasks, show how to make tea, wash dishes, wash socks, sweep floor..) |

| 13 | 13 | Let's practice survival skills (Make soup/fruit salad, grow seedlings, wash dishes) | |

| 14 | Children and HIV (effect of parent's HIV on children, age appropriate disclosure to children, understanding children's grief, role play disclosure to children | 14 | Let's live life (Identifying meaning, purpose and future orientation; play imagening game) |

| 15 | Life planning and goal setting (short and long term goals: socio-economic survival, plans for children, health care, draw future maps, focus on empowerment and hope) | 15 | |

| 16 | Knowing me, knowing you (mothers and children getting to know each other, working together to enhance bonding, preparing for picnic, playing games; second session: structured activities that enhance interaction, communication and trust) | ||

| 17 | |||

| 18 | Let's make a family memory (Creating a legacy by developing a memory box as a means of expression and interaction; take photographs, make family tree; tell family stories, preparation for loss) | ||

| 19 | |||

| 20 | |||

| 21 | Let's have fun together (Interaction between mother and child to enhance communication, working together, understanding each other; activities such as body mapping, making clay, sculpting, bead work, making masks) | ||

| 22 | |||

| 23 | |||

| 24 | Let's dream together (Planning for the future, helping each other to make wishes come true) | ||

| 25 | Let's celebrate life: family celebration (Future planning, communication, closure) | ||

After an introductory session with the mothers (aimed at building a relationship of trust), the next seven sessions for mothers focused on dealing with their personal experiences of HIV, disclosure, stigma and relationships so as to enhance their ability to cope with HIV. Six of the sessions dealt with parenting skills – three sessions focused on disciplining and caring for children and three others on understanding childrens's behaviour and needs in an HIV context. This was done to assist mothers to create an enabling environment for their children. The last session in the mothers' intervention dealt with life planning and goal setting. Sessions were scheduled for one and a half hours each and included experiential learning activities such as group discussions, sharing of experiences, behavioural modelling, games and exercises to enhance participation in the groups. The sessions of mothers and children were linked by informing the mothers of their children's activities and by prescribing assignments that they had to do together at home.

In addition to building self-esteem, certain skills were strengthened during the childrens's sessions. These included coping skills, interpersonal skills, self-protection and practical survival skills (such as performing household tasks), as well as skills to deal with challenges. The goal was to enhance optimism, emotional intelligence and an appreciation of meaning in life. Age-appropriate activities such as performing group rituals, playing games and board games, making drawings, singing songs, doing clay sculpting, participating in puppet play, storytelling and traditional cultural games were used to engage children in playful learning. Each session of one and a half hours comprised two or three major tasks split into a variety of discrete activities to keep the attention of smaller children. Because many parents had not yet disclosed their HIV status to their children, the intervention for children focused on generic skills and not specifically on HIV-related themes. Mothers were encouraged to disclose their HIV status to their children personally when they felt they were ready to do so.

For the joint sessions, we facilitated mother-child interaction through fun activities and making a family memory box to enhance bonding and to prepare children for potential loss and grief. Mothers and children did practical tasks, which provided children with the opportunity to assist their mothers with basic household tasks, such as making sandwiches. The intervention concluded with a session focusing on hope, setting future goals and doing future planning for the children.

Step 3: Piloting the intervention

The intervention was pilot tested in two groups of HIV-positive mothers and their children between the ages of six and ten years old. Thirty women who participated in the focus group discussions volunteered to participate in the intervention as well. They were between 25 and 42 years old and most of them did not have full-time employment. After consenting to participate, an initial 15 mothers and their children attended a weekly two-hour session for a period of 25 weeks. After the first two months, another 15 women and their children started the second group. The sessions were conducted in two large rooms at the hospital where the women received ART and where they had been recruited from. The venues used for the intervention were not associated with the ART programme. Participants' transport costs were reimbursed and they were provided with a meal before the group sessions started. Master's level Psychology students led the groups. Trained HIV-positive mothers from the same community as the participants acted as co-facilitators and encouraged women to express themselves in their own vernacular. Students and co-facilitators were trained to present the programme and to facilitate group discussions. Both students and cofacilitators attended weekly supervision sessions. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study.

Step 4: Formative evaluation

A continuous evaluation process was conducted as formative evaluation to assess the value of the content of the intervention and to identify aspects that could be improved. Each session was observed and rated by an external observer (Master's level students specialising in psychological research) who developed the rating scales used in the observations. The facilitators also completed process notes after every session to record participant reactions and any noteworthy occurrences. The formative evaluation was done to assess whether the activities included in the intervention contributed to group participation and learning, and to identify components that required further tailoring.

Rating scales

External observers and facilitators rated the following aspects of group participation in the mothers' and childrens's group sessions using Likert-type rating scales. These scales were developed specifically for this research and used specific behavioural indicators to describe each response category:

Attendance simply refers to the number of participants attending each session

Level of participation is the degree to which participants took part in the activities

Response categories ranged from 1 (facilitator-centred with little contribution from participants) to 4 (all participants contributed to activities).

Level of support among participants

Support was defined as listening to one another, showing interest and understanding, encouraging others or giving advice (Newcomb, 1990). The level of support was rated on a scale ranging from 1 (no support, no encouragement) to 3 (active encouragement, providing information, advice and understanding).

Group climate

The group climate was assessed using 14 of the 22 items from the Intervention Group Environment Scale (Wilson et al., 2008). The scale assesses group cohesiveness; implementation and preparedness of facilitators; and counterproductive activities. Wilson et al. (2008) reported internal consistency estimates of 0,92 for the scale as a whole. The observers and facilitators completed the scale after each session using a 4-point rating scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. The observers and facilitators were trained to use the group climate rating scale.

Qualitative feedback

Open-ended questions were asked after each session to obtain the observers' and facilitators' impressions of programme activities that encouraged participation or contributed to personal growth, as well as of activities that did not work well. Additionally they were asked to note changes they observed in the participants' behaviour and emotional expression.

Findings of evaluation of activities and observed changes

Because similar patterns were observed in the evaluation of the two groups of mothers and the two groups of children, the ratings for the groups of mothers and groups of children were analysed together. Following is a description of the processes that occurred in both the groups for mothers and children as observed by external observers and the facilitators.

Mothers' groups

Attendance

Attendance at the sessions was rather consistent throughout the 25 weeks of the intervention, varying from 8 to 11 (out of 15) participants per session, with an average of 9,25 (62%). The majority of the mothers attended between 15 and 20 sessions. No specific attendance pattern was observed. The reasons mothers gave for not attending included that they were feeling ill or were working, the weather was too cold or they needed to attend to family matters.

Level of participation

The mothers showed high levels of participation in group activities throughout the intervention (average rating of 3,28; range 1-4). Participation was lower during the AIDS information session (session 2) and during the session on emotional experiences (session 3) where women were initially hesitant to share their intimate experiences. As the sessions progressed, participants became more comfortable in sharing their experiences.

Level of support

The mean level of support in the group was 2,53 (range 1-3), indicating that mothers actively offered advice, information and understanding towards one another. Support was highest during the sessions focusing on the emotional experiences related to HIV (session 3), disclosure (session 6) and intimate relationships (session 7). An external observer wrote the following about session 3: “Deep emotions were shared, very personal stories and how they are coping. Some are not coping and others share their stories and inspire them.” After the session on disclosure the observer wrote: “The group provided a lot of support for one another, as they could relate to each others' situations.”

The lowest level of support was reported for session 14, when disclosure to children was discussed. Three mothers shared their experiences of having disclosed to their children, while the others voiced concerns about whether they should disclose or not.

Group climate

: The observers and facilitators rated the group climate as consistently positive. Cohesiveness was rated high (average 3,6; range 1-4), since most participants contributed to the group and supported one another. Implementation and preparedness of facilitators were rated high, meaning that the groups were well-organised (average 3,9; range 1-4).There were low levels of counterproductive behaviour such as disagreements, non-participation and lack of control in groups (average 1,3;range 1-4). Session 3 where mothers told their life stories especially contributed to group cohesion, as reflected in the following report: “Mothers opened up, expressed their concerns and fears. The group becomes more sensitive, responding to each other instead of only to the facilitator. This involved more active listening from everyone, whereas earlier everyone was slightly detached.”

Evaluation of activities

Activities that facilitated participation were group discussions, sharing of experiences, relaxation exercises, ice-breakers, music, sharing of childhood memories, sharing of happy moments and laughter. The activities that were observed to have contributed most to women's personal growth included sharing of their personal experiences and receiving support and advice (sessions 3-7). The observer commented: “Sharing of experiences made women realise they are not isolated. They have the support and advice from one another.”

Only a few activities were identified as not working well. These were mostly due to interpretation problems or unclear instructions because of the language gap between the group and the facilitator. The latter was better understood when the co-facilitator re-phrased or translated instructions.

In some sessions the emotional intensity of women's disclosures made it difficult for the facilitators to allow enough time for comforting women and still completing the proposed content for the session. For some women it was the first time to share the emotional pain relating to past sexual abuse or having been HIV infected. For example, when women were asked to share positive memories of their own childhood, they often spoke about experiences of being rejected or abused as these memories were most prominent in their lives. Intense emotional sharing contributed to the cohesion in the group, but created problems of staying within the time limits. Facilitators also experienced difficulty when the co-facilitators were unable to translate the intense emotions expressed by the women in an effective way, and in these instances the facilitator needed to rely on the group members to provide support. Where necessary, the facilitators referred the women to a counsellor who was part of the research team for further support.

Sessions on parenting skills helped the mothers to explore their parenting styles and the problems they experienced with their children. The majority did not want their children to have the same experiences that they had as children and wanted to create opportunities for their childrens's development. Many women were still unsure whether they should disclose their status to their children and were deeply struck by the session that dealt with the effect that HIV had on children.

Observed changes

Facilitators and observers noted that participants initially appeared to be rather depressed and reserved. From the third session onwards, gradual changes took place as participants became more supportive and more light-hearted. During the course of the sessions, a few women reported that they had disclosed their status to their partners and family members and that the news had been well accepted. At the end of the sessions there were only two women who still did not want to disclose to their partners - because they were financially dependent on them and feared rejection. Women appeared to have a better understanding of their childrens's behaviour, listened to their children more and were more involved in problem solving with their children.

Childrens's groups

Attendance

Attendance varied between four and 11 children per session, with an average of nine per session. Most children also attended 15 to 20 sessions. They did not always accompany their mothers and in a few instances the children attended sessions on their own when their mothers were sick, showing that they wanted to attend.

Level of participation

Participation was generally high for all the sessions (average 3, range 1-4), though in some sessions there were one or two children who were either too passive or too active or misbehaving, and who needed encouragement to participate in the activities. The facilitators observed that some children had difficulty drawing or cutting out pictures (sessions 4 and 5) – skills that they were expected to have developed at this age. Differences in levels of cognitive development among participants therefore needed to be considered in structuring activities. At the start of each session, participation was usually high, but it decreased as the session progressed. Sessions were consequently revised, allowing for more brief breaks and more variation in activities. Participation of the children depended to a large extent on the skills and preparedness of the facilitator in encouraging them, as is illustrated by the observer's comment: “The facilitator is part of the group; she manages the group activities and pays attention to those who do not want to cooperate.” childrens's participation, sharing and enjoyment appeared to increase as time progressed.

Level of support

Childrens's levels of support for each other was moderate (mean: 2,32; range 1-3) across sessions, meaning that some children helped and encouraged others, but this was not consistent. High levels of support were reported for sessions 6 to 13 (coping and survival skills), and lower levels of support for sessions 4 and 5 (which involved individual activities such as drawing). The observer noted: “Children did all their activities together and they were able to help each other. The facilitator succeeded in creating relationships of trust between the children and herself.”

Group climate

Cohesiveness was rated as generally high (3,5; range 1-4) while there was a low level of counterproductive behaviour (1,5; range 1-4). Observers lauded the level of organisation and control by facilitators (3,8; range 1-4), In some sessions, facilitators had difficulty getting the children to cooperate, and one observer noted: “The children did not want to participate. They were misbehaving. It is as if there are individuals in the group, they do not interact or bond with each other.”

Evaluation of activities

A group ritual that was performed at the beginning of every session created a specific atmosphere of caring and inclusion in the group, as the observer commented: “It helped to make everyone feel part of the group right from the start.” Children benefited from activities that encouraged team work and expressive activities such as body mapping, storytelling, engaging with puppets, using clay and singing. The inclusion of culturally accepted games helped children express their emotions about family interaction and problems experienced at home. The practice of survival skills, such as cooking soup and preparing sandwiches, was a huge success because children worked together, learnt new behaviours and surprised their mothers by serving lunch, which made them feel very proud.

A few activities were identified as not effective. Drawing as a means of expression was replaced with clay sculpting, painting and puppet play. An effort was made to include culturally appropriate games or familiar animal stories.

The fact that some children were aware of their mothers' HIV status and others not, caused a dilemma for the facilitators. They were unable to speak about HIV in the sessions or address the effects of HIV in a household, because they were afraid that they might indirectly disclose the mothers' status or stimulate questions about HIV. For that reason, no direct references to HIV were made in childrens's groups.

Observed changes

The childrens's groups revealed some difficulties associated with working with children living in severe poverty. Some of the children had delayed cognitive skills, came to the session dirty, were often ill, had significant behavioural problems and revealed stress in their family relationships. One of the most important observations was that the children –even those who had been reserved and uncooperative in the beginning –became more cooperative as the programme progressed. They became more willing to share their feelings and their play shifted from playing individually to playing with others. The facilitators and observers regularly commented on the joy, positive participation, happiness and excitement of the children during the sessions.

Joint sessions

During the first joint session, only a few mothers interacted with their children. Some of the mothers did the activities, but did not give attention to bonding with their children as partners in the games. This resulted, for instance, in mothers and children hurting one another in the „one-legged-race' in their effort to win. Mothers spoke about the fact that, in their culture, mothers do not play with children and that this required a new interactional style for them. After this had been discussed, the next session changed into a “very active, lively, engaging activity once the children and mothers got together.” The mothers experienced playing and singing with their children as rewarding and as a relief from their own stress and worries. The children had fun playing with their mothers. The joint body mapping, rope skipping and making figures from clay were highlights for the mothers in which they were able to share emotions and stories with their children. In contrast, the children were cautious in expressing their feelings freely in the presence of their mothers.

Making memory boxes was introduced as making a family legacy of tangible memories such as songs, letters and photographs. The children experienced the making of the memory box as enjoyable and the mothers used it as an opportunity to create memories together.

Step 5: Formative evaluation: experiences of participants

Three months after completion of the intervention, all participants were invited to a focus group discussion to revisit the value that the intervention had in the lives of mothers and children. Unfortunately, only ten mothers and their children (33%) participated in this discussion. As it transpired, many mothers had taken up employment in the interim and could therefore not attend the group discussion. This was heartening, but skewed the discussion as it meant that people who benefited more from the intervention were less likely to participate in feedback. The discussion with mothers, facilitated by one of the co-facilitators in the vernacular of the participants, focused on what the participants had learnt from the intervention, as well as on changes in their own behaviour, in the relationship with their children and in their childrens's behaviour. The focus group discussion was tape recorded, transcribed and translated into English. A thematic analysis was done to identify themes from the discussion.

Findings: The value of the intervention

Mothers attached the following value to the intervention after three months

Increased optimism and empowerment

Mothers changed their perception of HIV and had a more optimistic view of life. They reportedly felt empowered to talk about HIV and to deal with stigma.

Increased disclosure

All the mothers who had participated in the focus group disclosed their HIV status to their families after attending the sessions. They said that they did not allow HIV to control their lives any more and that they had more meaning in their lives. One mother said: “Before I joined the group there was a hostility situation at home, it was a big problem talking about the HIV or listening to a programme on TV about HIV. Now that I have disclosed, we can discuss it as a family, they even remind me when it is time to take my medicine.” Another mother said: “I was shy and not feeling free to talk about HIV, but after I joined the group I was empowered, I managed to disclose my status to my parents.” Their feeling of empowerment seemingly enabled them to assist others in their community to accept their status and to live healthy lives. Increased support from others: Group participation had helped the mothers to build new relationships that helped them to accept their status. One mother remarked: “Before I joined the group I was a shy person and felt lonely most of the time. Now there is happiness in my house.” Another mother acknowledged: “I learned to love and to be with people. I got a new friend; we visit each other to check on each other.”

Increased parenting skills and communication

Mothers indicated that they implemented in their homes what they had learnt about parenting skills. They perceived themselves to be more supportive, accepting and listening to their children and they experienced a closer relationship with their children: “We understand each other better now. I give myself time to sit with him to do the homework together”. Mothers implemented new ways of disciplining children by listening to children and engaging in problem-solving rather than to use physical punishment. One mother said: “Everything has changed. We learned to know each other. I don't shout anymore and I have time for my child when he asks me something. We can talk about it.”

Positive changes in their children’s behaviour

Mothers found their children to be less aggressive and avoidant, more confident, obedient and disciplined, and more understanding of others. Children were more actively involved in the household, which created a cooperative atmosphere in the house.

Women expressed the need for the support group to continue. They wished it to include a skills-building programme that would enable them to earn an income and improve the quality of their lives.

Step 6: Lessons learnt and changes made in interventions for future implementation

Findings that emerged from the formative evaluation were used to modify the intervention for use in a large-scale randomised control trial that included summative evaluation. Overall, the intervention was shortened by three sessions. Further shortening can be considered to avoid high levels of non attendance.

Changes to the mothers’ intervention

The sessions on disclosure and intimate relationships were moved to an earlier slot in the programme because these were found to be important issues women had to deal with.

Family planning was added to the session on intimate relationships, as this aspect was regarded as important to negotiate with sexual partners. Handouts were developed with notes on problem-solving and ways of coping with stress as well as human rights issues, because women required more detailed and concrete information on these topics. Parenting skills sessions were shortened to deal with parenting styles, discipline and problem-solving as well as understanding and nurturing a child. Modelling of skills and concrete scenarios were added in the parenting sessions.

More time for reflection on the previous sessions was included to allow for the integration of knowledge.

Changes to the children's intervention

Sessions were shortened where possible; activities were varied and the sequence of some activities was changed to retain the childrens's attention.

Activities were made more concrete and interactive. For example, puppets rather than drawings and role play were used to encourage emotional expression without direct exposure.

More indigenous stories or stories involving animals, that were familiar to the children, were added.

All mention of HIV was removed because it could result in discussions that might indirectly disclose the status of the mothers and would interfere with confidentiality of information about the mothers.

Changes to the joint sessions

More attention was given to strengthening the mother-child relationship. It was explained that the goal of activities was not winning or getting it right, but bonding, learning how to play and talk with one another and having fun together. Mothers were encouraged to strengthen bonds with their children by discussing what they had learned about interaction.

The memory box exercise was shortened to two sessions. Emphasis was placed on the fact that it is beneficial for every parent (irrespective of HIV status) to construct family memories with their children.

Discussion

Prior to the intervention described in this paper, there had been as far as we are aware, no interventions in Africa that provided a joint opportunity for mothers and children to deal with issues related to HIV. The intervention described here provided such an opportunity for a group of mothers and their young children (aged 6 to 10 years). The study confirmed the value of the intervention in strengthening mother and child relationships while coping with illness so as to eventually build psychological resilience in youngsters. The current intervention strategy was based on a literature review, needs identified through focus groups discussions and eventually the observation of participants' reaction during piloting of the intervention.

The focus group discussions prior to the intervention provided important information about the mothers' own desires to live more positively, their recognition that their childrens's behaviour was affected by their (the mothers') HIV status and their desire for assistance with parenting and communicating with their children. At that stage mothers had ambivalent feelings regarding disclosing their HIV status to their children and only a few mothers reported to have disclosed. This information was used in the development of a 25-week structured group intervention for mothers and children using both parallel and joint sessions.

The piloting and formative evaluation of the group intervention demonstrated that there was a good degree of participation and positive group climate in both mothers' and childrens's groups. Mothers shared their emotional experiences and supported one another. Most topics and activities presented were well received. Activities that were not beneficial were removed or changed in the final intervention. It was challenging to involve young children from a disadvantaged community in capacity-building activities, as their general level of cognitive and emotional development was below par. Facilitators for the childrens's groups therefore require specific training.

The fact that some mothers had not yet disclosed their HIV status to their children presented a barrier in implementing the intervention for children. Early on in the intervention researchers encouraged the mothers to disclose, but for ethical reasonswithheld themselves from disclosing mothers' status to their children, even indirectly or by default. For this reason, all HIV-related content was removed from the childrens's intervention. Instead, the programme was directed at developing the childrens's capacity to deal with general life issues. Initially, this strategy presented risks of cementing a pattern of secrecy in families and missing opportunities to assist the children in dealing with the consequences of HIV in their lives. As it transpired, however, the coping skills that mothers developed through the intervention vindicated the strategy, as many mothers accepted the opportunity to disclose their status to their families(although not necessarily to very young children). The strategy of focusing on general development was therefore retained in further phases of the intervention, despite some researchers pointing out the benefits for children to know their mothers' HIV status (Palin et al., 2009; Rosenheim & Reicher, 1985).

Follow-up interviews indicated that a focus on the personal well-being and parenting style of mothers had positive implications for their relationships with their children. A different behaviour pattern formed between mothers and children that could strengthen both aspects of family relationships and the psychosocial functioning of the child. It should be noted that a large number of mothers (67%) did not attend the focus group follow-up session three months after the completion of the intervention. Ironically, indications were that this was due to positive changes in their lifestyles (accepting full-time employment), either as a result of or coincidental to the intervention. Feedback from these participants, whether immediately after completion or through individual approaches later on, may have strengthened claims to success of the intervention. As it stands, such claims rest heavily upon the evaluation of the remaining mothers and that of observers and facilitators.

To strengthen resilience in children is a multifaceted process. This intervention is based on evidence that the quality of parenting mediates development outcomes among HIV-affected children (Brandt, 2005; UNICEF, 2008). It is acknowledged that there are many more ways to promote the resilience of children. This intervention starts at the core of family interaction to promote psychosocial well-being and psychological resilience. Should this intervention be found to effectively contribute to strengthening mother-child interaction (in an outcome evaluation), it may be implemented alongside community interventions that focus on social connectedness of mothers through social networks and economic empowerment. The impact of these interventions on resilience of HIV-affected children will only be observed over many years from now.

The results of a large-scale randomised control trial that uses the refined interventions with mothers and children are due shortly. The mentioned trial attended to the sustainability of the intervention by training community workers to implement the intervention in the vernacular of the participants. The intervention developed in this study can easily be applied elsewhere using the detailed manual, though specialised training may be necessary.

The pilot implementation and formative evaluation of the intervention reported on in this study provided insights into the psychosocial needs of children affected by HIV and taught lessons related to mother and child interaction and experiences in the HIV context that can be valuable in other settings, both in Sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere.

Highlights.

The pilot implementation and formative evaluation of the intervention to promote resilience in children affected with HIV provides insight into the psychosocial needs of these children and mother and child interaction as well as experiences in the HIV context as well as the intervention developed for a disadvantaged African community.

Acknowledgement

The project was done as a collaborative effort between researchers from the University of Pretoria and Yale University. It was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant R01 MH076442-01.

Biography

Maretha Visser PhD is a counselling psychologist and professor in the Department of Psychology, University of Pretoria. She has an interest in implementing large-scale interventions in community settings with the aim of developing supportive infrastructure in disadvantaged communities. She has a longstanding interest in the prevention of HIV in community settings and developing strategies to assist people living with HIV/AIDS to deal with the psychological implications.

Michelle Finestone is the Project Coordinator of the Faculty of Education at the University of Pretoria, South Africa. Michelle was also the Project Coordinator for the NIH funded Kgolo Mmogo Resilience project that was a joint research project between the University of Pretoria and Yale University in Atteridgeville, South Africa. She holds an MSc in Medical Applied Psychology and a Masters degree in Educational Psychology from the University of Pretoria. She is currently working on her doctoral degree. The working title of the related study is Evaluating a group based resilience intervention for children of HIV positive mothers.

Kathleen Sikkema, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, and Global Health at Duke University, is a clinical psychologist with emphases in health and community psychology, and the Director of the Social and Behavioral Science Core in Duke's Center for AIDS Research (CFAR). Her expertise is in the conduct of randomized, controlled HIV prevention and mental health intervention trials. Dr. Sikkema's research is focused on the development and evaluation of HIV risk behavior change interventions, with expertise in community-level interventions and she also conducts research on the development of HIV-related coping and secondary prevention interventions.

Alexandra Boeving is an assistant professor in the Department of Pediatrics at Wake Forest University, School of Medicine. She is a clinical child psychologist with expertise in child adaptation to pediatric and maternal chronic illness. She completed a post doctoral fellowship at Yale University school of Medicine's Center for Interdisciplinary research on AIDS (2005 to 2007) while working on this project.

Ronél Ferreira is head of the Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Pretoria. Her teaching and learning activities focus on emotional and behavioural challenges experienced by children. She is involved in various research projects, some of which involve international affiliations. Her research focus areas are psychosocial support within the context of vulnerability, HIV&AIDS, asset-based psychosocial coping, and the use of action research in combination with intervention-based studies that could improve community-based coping. Her research accomplishments are signified, amongst others, by being a NRF-rated researcher and the recipient of the Samuel Henry Prince Dissertation Award of the International Sociological Association.

Irma Eloff is the dean of the Faculty of Education at the University of Pretoria. Irma is an NRF-rated researcher and a registered psychologist. She has received several awards for her research in Education and Educational Psychology. She has obtained tertiary qualifications at the Universities of Pretoria, Stellenbosch and Northwest. She has also been a visiting professor at Yale University during 2001-2002 and she has lectured across the globe on themes of positive psychology, early intervention, inclusive education and HIV & AIDS.

Brian Forsyth is Professor of Pediatrics and Yale Child Study Center at Yale University School of Medicine and Deputy Director for International Research for the Yale Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (CIRA). As a paediatrician, Dr Forsyth's research is primarily focused on the effects of HIV disease on children, both those who are HIV-infected and those who are affected by HIV disease within their families.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bauman LJ, Foster G, Silver EJ, Gamble I, Muchaneta L. Children caring for their ill parents with HIV/AIDS. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2006;1(1):56–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bennell P. The impact of the AIDS epidemic on schooling in Sub-Saharan Africa. Paper for the Biennial Meeting of the Association for the Development of Education in Africa. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R. Maternal well-being and childcare and adjustment in the context of AIDS: What does the psychological literature say? Centre for Social Sciences Research; University of Cape Town; 2005. Working Paper 135. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Foulis C, Maimane S, Sibiya Z. ‘I have an evil child at my house’: stigma and HIV/AIDS management in a South African community. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(5):808–815. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandon U, Richter L. Strengthening families through early intervention in high HIV prevalence countries. AIDS Care. 2009;21(S1):76–82. doi: 10.1080/09540120902923097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen E, Wyman P, Work W, Parker G. The Rochester child resilience project: Overview and summary of first-year findings. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Dutra R, Forehand R, Armistead L, Brody G, Morse E, Morse-Simon P, Clarke L. Child resiliency in inner-city families affected by HIV: the role of family variables. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:471–486. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eloff I, Boeving A, Briggs-Gowan M, De Villiers A, Ebersohn L, Ferreira R, Finestone M, Neufeld S, Sikkema K, Visser M, Forsyth B. Children affected by HIV & AIDS: Contemplations beyond individual resilience.. Paper presented at the Conference of the Psychological Society of South Africa; Johannesburg. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Evans RMC. Social networks, migration and care in Tanzania:caregivers’ and children's resilience to cope with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Children and Poverty. 2005;11(2):111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Steele R, Armistead L, Morse E, Simon P, Clarke E. The family health project: Psychosocial adjustment of children whose mothers are HIV-infected. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosegood V. The demographic impact of HIV and AIDS across the family and household life-cycle: implications for efforts to strengthen families in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Care. 2009;21(S1):13–21. doi: 10.1080/09540120902923063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough ES, Brumitt G, Templine T, Saltz E, Mood D. A model of mother-child coping and adjustment to HIV. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56(3):643–655. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly K, Ntlabati P, Oyosi S, van der Riet M, Parker W. Making HV&AIDS our problem. Young people and the development challenge in South Africa. Arcadia (South Africa): Save the children South Africa Programme. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- King E, De Silva M, Stein A, Patel V. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009. 2. Wiley & Sons; 2009. Interventions for improving the psychosocial well-being of children affected by HIV and AIDS. Art No. CD006733. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006733.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71(3):543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons A, Coyle A, editors. Analysing qualitative data in psychology. Sage; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mallmann S. Program of the Catholic AIDS Action. Maskew Miller Longman; Namibia.Cape Town: 2003. Building resilience in children affected by HIV/AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- McNiff J. Action research for professional development: Concise advice for new (and experienced) action researchers. September Books; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nattrass N. AIDS unemployment and disability in South Africa: the case for welfare reform. The Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine. 2005;30(20):30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson Mandela Foundation . Researched for the Nelson Mandela Foundation by the HSRC and EPC. HSRC Press; Cape Town: 2005. Emerging voices. A report on education in South African rural communities. [Google Scholar]

- Nöstlinger C, Bartoli G, Gordillo V, Roberfroid D, Colebunders R. Children and adolescents living with HIV positive parents: Emotional and behavioural problems. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2006;1(1):29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden J, Nyblade L. Common at its core: HIV-related stigma across contexts. International Centre for Research on Women (ICRW); Washington (DC): 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Palin F, Armistead L, Clayton A, Ketchen B, Lindner G, Kokot-Louw P, Pauw A. Disclosure of maternal HIV-infection in South Africa: Description and relationship to child functioning. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;3(6):1241–52. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9447-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyland SM, McMahon T, Higgins-Delessandro A, Luther S. Inner-city children living with an HIV-seropositive mother: Parent-child relationships, perception of social support and psychological disturbance. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2002;11:313. [Google Scholar]

- Richter L. The impact of HIV/AIDS on the development of children. In: Pharoah R, editor. A generation at risk? HIV/AIDS, vulnerable children and security in southern Africa. Institute for Security Studies; Pretoria: 2004. pp. 9–31. (Institute for Security Studies, Monograph No.109) [Google Scholar]

- Richter L, Manegold J, Pather R. Family and community interventions for children affected by AIDS. Human Sciences Research Council; Cape Town: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Richter LM, Sherr L, Adato M, Belsey M, Chandan U, Desmond C, Drimie S, Haour-Knipe M, Hosegood V, Kimou J, Madhavan S, Mathambo V, Wakhweya A. Strengthening families to support children affected by HIV and AIDS. AIDS Care. 2009;21(S1):3–12. doi: 10.1080/09540120902923121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa S, Lehnert W. Children without adult caregivers and access to social assistance. Children's Institute, University of Cape Town and the Alliance for Children's Entitlement to Social Security; Rondebosch, South Africa: 2003. Workshop Report.Hosted by the Children's Institute, University of Cape Town and the Alliance for Children's Entitlement to Social Security. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheim E, Reicher R. Informing children about a parent's terminal illness. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1985;26:995–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1985.tb00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. In: Rolf J, Masten AS, Chicchetti D, Nuechterlein KH, Weintraub S, editors. Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology: Vol. III: Social competence in children. University Press in New England; Hanover, NH: 1990. pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Santrock JW. Child development. 12thed. McGraw Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg M, Johnson S, Schierhout G, Ndegwa G, Hall K, Russell B, et al. A survey of households affected by HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Systems Trust; Washington DC: 2001. Hitting home: How households cope with the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. [Google Scholar]

- Strode A, Barrett-Grant K. The role of stigma and discrimination in increasing the vulnerability of children and youth infected with and affected by HV&AIDS. Save the Children South Africa Programme; Arcadia, South Africa: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS, UNICEF, USAID Children on the Brink 2004: A joint report of new orphan estimates and a framework for action. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . Childworkers in the shadow of AIDS: Listening to the children. UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office; Nairobi: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . The evidence base for programming for children affected by HIV/AIDS in low prevalence and concentrated epidemic countries. The Quality Assurance Project, USAID Health Care Improvement Project; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vinson JA. Children with asthma: initial development of the child resilience model. Pediatric Nursing. 2002;28:149–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser M, Mundell JP, De Villiers A, Sikkema K, Jeffery B. The development of structured support groups for HIV+ women in South Africa. SAHARA: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance. 2005;2(2):333–343. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2005.9724858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner FE, Smith RS. Overcoming the odds: High risk children from birth to adulthood. Cornell University; Ithaca (NY): 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PA, Hansen NB, Tarakeshwar N, Neufeld S, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Scale development of a measure to assess community-based and clinical intervention group environments. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36(3):1–18. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright BA, Lopez SJ. Widening the diagnostic focus. A case for including human strengths and environmental resources. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford University Press; Buenos Aires: 2005. pp. 26–44. [Google Scholar]