Abstract

Are personality traits mostly related to one another in hierarchical fashion, or as a simple list? Does extracting an additional personality factor in a factor analysis tend to subdivide an existing factor, or does it just add a new one? Goldberg’s “bass-ackwards” method was used to address this question, based on rotations of 1 to 12 factors. Two sets of data were employed: ratings by 320 undergraduates using 435 personality-descriptive adjectives, and 512 Oregon community members’ responses to 184 scales from 8 personality inventories. In both, the view was supported that personality trait structure tends not to be strongly hierarchical: allowing an additional dimension usually resulted in a new substantive dimension rather than in the splitting of an old one, and once traits emerged they tended to persist.

Keywords: personality factors, bass-ackwards method, personality scales, adjective self-ratings, trait hierarchies

1. Introduction

How many personality dimensions are there? If one takes all the terms that have been used in natural language to describe personality, the answer clearly is “many thousands.” Allport and Odbert (1936), in their list of 17,953 person-descriptive English words from Webster’s unabridged dictionary, could serve as a start, or their shorter list of 4504 personality-trait words more strictly defined. But the designers of personality inventories typically opt for assessing a good many fewer dimensions. Eysenck favored three (e.g., Eysenck & Eysenck, 1968), as did Tellegen (1985)—although slightly different; Cattell (1946) preferred sixteen; the Big Five (e.g., Digman, 1990; Goldberg, 1993) have wide current popularity; and there has been recent interest in the Big One (Musek, 2007) and the Big Six (Saucier, 2009).

It should be noted that asking “How many dimensions” presupposes that a dimensional approach to personality, as exemplified by factor analysis, is an appropriate one. It has certainly been a popular one, as evidenced by the theorists mentioned and many others, including such pioneers in the field as Guilford (1936) and Thurstone (1951). There are other legitimate ways of considering personality structure, ranging from hydraulic metaphors to brain systems, including such differing psychometric approaches as the radex (Maraun, 1997) and cluster analysis (Tryon, 1970). Our concern in the present paper, however, is with a dimensional approach.

Our general view is that a theorist or test designer can have as few or many dimensions of personality as he or she elects to measure. But how are choices of differing numbers of dimensions related? Most of the dimensional systems mentioned have been developed from the bottom up, starting with individual words, items, or item clusters. However, one can also take a “bass-ackwards” (Goldberg, 2006) or sequential factors approach to studying the relationships among different numbers of extracted factors. In examples, applications to personality began with a large number of adjectives (1710 in one case, 435 in another), from which 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc., factors were extracted and rotated orthogonally by varimax. The results were arranged pictorially as a series of rows of boxes, with arrows representing the correlations between the factor scores of factors at adjacent levels. An advantage of this approach is that it does not require deciding that some fixed number of dimensions describes personality, but, rather, permits comparison of the consequences of dealing with varying numbers. Moreover, the pattern of relationships between levels may help us evaluate different types of relationships among traits.

We may distinguish two extreme forms of trait organization. We will call them the hierarchy and the list. In general, in a hierarchical organization, traits at any given level in the trait hierarchy split into subtraits at the next level down, For example, in a hierarchical view of the Big Five (e.g., Musek, 2007), a general factor of personality at the top level is divided into alpha and beta factors at the next level, and these are in turn split, one into three and one into two factors, to yield the Big Five. These may then be further subdivided—e.g., for Costa and McCrea (1992), each into six facets.

If personality trait organization is strictly hierarchical, each row of a sequential-factors schema will have one trait from the preceding row split into two parts, not necessarily exactly equal, but both substantial, with the split occurring anywhere along the row. The larger part will retain its place, and the other move to the new slot in the row. And traits will only rarely persist more than a few levels downward in the structure without undergoing a split.

By contrast, in a purely list organization of traits, each step in the analysis adds to the list of traits, and major splits do not occur. A new trait emerges at each level, possibly—but not necessarily—with a few minor links to the preceding level, and the new trait as well as the traits from the preceding levels persist down through successive levels in the diagram.

These two do not exhaust the ways in which traits may be organized: for example, circumplexes (Wiggins, 1979) or other structures may occur. But a distinction between hierarchical and list-type organization for personality traits would seem worth exploring, and the sequential-factors schema represents one way of doing it.

The issue of whether personality traits do or do not form hierarchies has been controversial. The possibility of a hierarchical structure centered on the Big Five was mentioned earlier. But Revelle and Wilt (2013) have used typical levels of trait intercorrelation to compare a hierarchical structure of personality traits with that of cognitive traits, and concluded that the former has little psychometric credibility.

In the present paper, we use a sequential-factors approach to address this question, using two large data sets originally gathered for other purposes. One is the reponses of 320 college students to 435 common English adjectives describing personality traits. All of the participants rated the adjectives as describing themselves, and most of them also used them to describe a person they liked of their same age and sex (Goldberg, 1990). The other starting point is 184 scales from 8 standard personality inventories that were completed by some 500 members of the Eugene-Springfield (Oregon) community sample (Grucza & Goldberg, 2007). At issue: Will the results predominantly conform to a list or to a hierarchy scheme? Will they generalize across the two data sets?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The sample for the adjective ratings consisted of 320 undergraduates in a psychology class who rated themselves; 316 of them also rated someone of their same age and sex whom they liked (Goldberg, 1990). These 636 sets of ratings provide the first data set analysed.

The participants in the sample providing the second data set, the scale scores, were adult community residents of a wide age range who agreed to complete a number of personality questionnaires by mail over a several-year period for honoraria ranging from $10 to $25. Further details on their characteristics may be found in Grucza and Goldberg (2007). The number of participants for individual inventories ranged from 680 to 857; 514 individuals with relatively complete data over the period were used for the present analysis (details below).

2.2. Measures

For the student sample, 7-point rating scales were used. Four midscale response options were provided— average or neutral, it depends on the situation, don’t know and term unclear or ambiguous (Goldberg, 1990). Originally, 587 adjectives were rated; they were reduced to the present 435 by eliminating less familiar ones (Saucier & Goldberg, 1996).

For the community sample, the lowest-level scales available from each inventory were taken as the starting point—these were variously labeled in the different inventories as subscales, facets, clusters, basic scales, etc.; 184 such scales from 8 inventories were used. Respondents with more than 10% missing scores (which usually meant missing one or more inventories) were eliminated from the sample; the missing scale values from the remaining participants were replaced by mean values for the scale. A number of more sophisticated methods of imputing missing data exist, but when the amount of missing data is small (1.9% at this stage for these data) simpler methods tend to give very similar results (Parent, 2013).

2.3. Analyses

The factor analyses involved were carried out as principal component analyses rather than strict factor analyses, for the advantages of computational economy, avoidance of Heywood cases, and the ability to calculate factor scores directly rather than having to estimate them. With large initial matrices, such as the ones involved in this study, the two methods tend to give closely similar results. (Small matrices present an entirely different story—e.g., see Loehlin, 1990). Orthogonal (varimax) rotations were used for the same reasons of simplicity and robustness as the use of principal components. In comparisons (Goldberg, 1990) involving 5 factors and 75-variable adjective-based matrices, factor scores based on five different extraction methods, including principal components, were correlated on average from .950 to .996; and factor scores from oblique and orthogonal rotations were correlated on average from .991 to .995. For the sequential-factor analyses of the present study, inter-level correlations were calculated via factor scores, either directly or via the shortcut calculation described by Waller (2007).

For practical reasons of display, the analyses in this paper will be presented only as far as 12 factors. This, however, should be adequate. A preliminary analysis using the Cudeck-Browne criterion (Cudeck & Browne, 1983) suggested that cross-replicated stability existed for 8 factors for the 435 adjectives, and 11 for the 184 scales. The Cudeck-Browne criterion involves splitting the sample into halves A and B, extracting factors from subsample A, and comparing the correlation matrix implied by them to the correlation matrix calculated directly in subsample B. Such a criterion normally improves as more and more factors are extracted, and then deteriorates as factors start to reflect merely idiosyncratic features of sample A. This procedure can then be carried out in reverse, extracting factors in sample B and testing them against sample A correlations. There is some ambiguity as to whether the criterion should be calculated over the entire matrix, or over its off-diagonal elements only. We have followed the latter procedure, to avoid dominating the criterion by the error in the diagonal. In the present case, the criterion reached a minimum at 11 factors in each direction for the scales, and 8 in each direction for the adjectives.

3. Results and Discussion

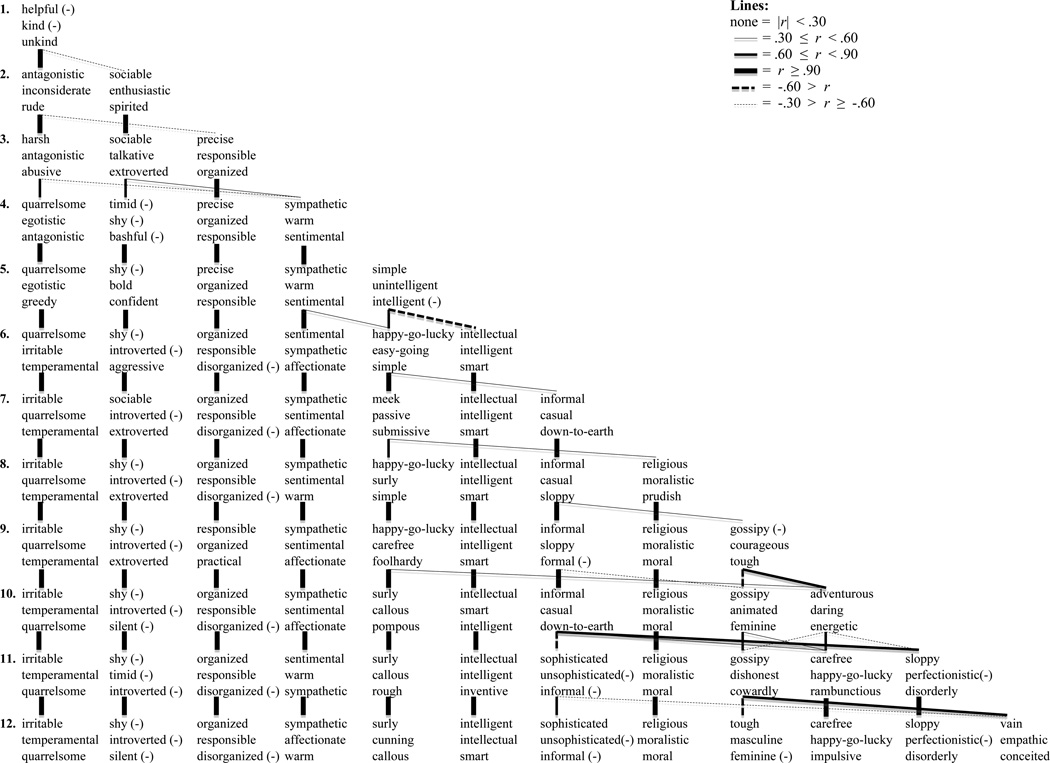

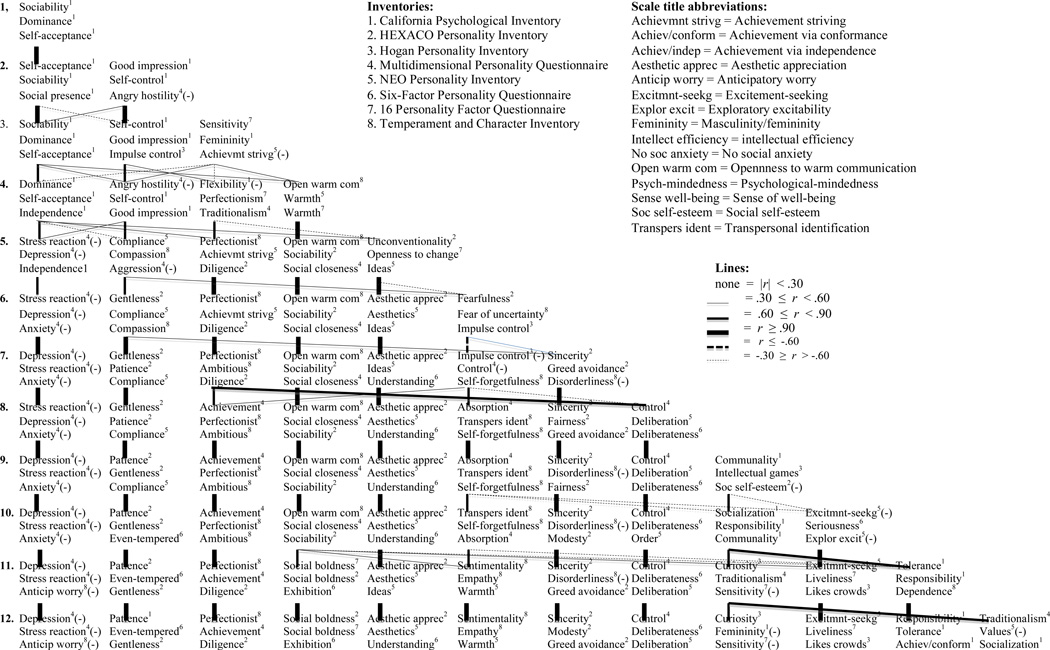

The basic results are presented in Figures 1 and 2, for adjectives and scales, respectively.

Figure 1.

One to twelve orthogonally rotated adjective-based factors. The three adjectives with highest absolute loadings are shown for each factor. Thickness of lines reflects magnitude of correlations between adjacent levels—dashed lines represent negative correlations.

Figure 2.

One to twelve orthogonally rotated scale-based factors. Titles of the three scales with highest absolute loadings are shown for each factor (abbreviated if necessary). Thickness of lines reflects magnitude of correlations between adjacent levels—dashed lines represent negative correlations.

3.1. Starting with adjectives

For the adjectives, each factor is represented in Figure 1 by the three adjectives that have the highest absolute loading on it (if that loading is negative, a minus sign is appended). Correlations of .30 or more between the factor scores of factors in adjacent levels of the diagrams are shown by lines of varying thickness, depending on the magnitude of the correlation. Negative correlations are indicated by dashed lines. The factors at each level are aligned below the factor in the level above with which they are most highly correlated, except in one instance involving a conflict, when the secondhighest was used. As is evident from the figures, in many cases factors retain their essential identity (i.e., via rs of .90 or greater) all the way down the diagram after their initial emergence. In Figure 1 this is true of the first four factors after Row 4. These factors can be recognized as variants of three of the Big Five. The first (quarrelsome, irritable, temperamental, etc.) represents the negative pole of Agreeableness. The second represents Introversion-Extraversion in its popular sense (socially bold vs. shy). The third is Conscientiousness (precise, organized, responsible), and the fourth represents positive Agreeableness (sympathetic, sentimental, warm). A fourth member of the Big Five, Intellect, emerges in Column 6 (intellectual, intelligent, smart). Interestingly, there is no clear example of the remaining member of the Big Five, Neuroticism, although aspects of it may perhaps be seen in the negative poles of the fifth and tenth factors (i.e., the opposite of happy-go-lucky and carefree).

The typical picture presented by Figure 1 is that at each level the factors of the preceding level persist, and a new one emerges—usually, but not always, with modest contributions from one or more of the existing factors. Occasionally, a hierarchical pattern occcurs: as between Levels 5 and 6, where the simple/unintelligent factor splits into an easy-going factor and (reversed) an intellectual one. A bit of complex reshuffling occurs between Rows 10 and 11 at the far right of the diagram, and once or twice factors change direction—for example, from the informal to the formal pole of the informal/casual factor between the latter rows. But for the most part a relatively simple persistence of existing factors and addition of a new one marks each step. Thus the stucture mostly conforms to a list rather than a hierarchical pattern.

3.2. Starting with scales

What happens if we start with inventory scales rather than single adjectives (Figure 2)? In this figure, each factor is represented by the titles of the three scales loading most highly on it (abbreviated if necessary; again with minus signs for negative loadings). On the whole, we again see a list-type pattern: most factors persisting downward in the diagram at high levels of inter-row correlation, with the new factor at each level usually, but not always, drawing modestly from the factors of the row preceding. The first few rows show a fair amount of of merging and splitting, but after that there is not much of this, except for the hierarchical division of Conscientiousness at Row 7 into achievement and control factors, and some splitting-up of the social closeness factor after Row 10. As for the Big Five, Neuroticism is prominent as the first factor. Agreeableness is represented by the gentleness/patience/compliance factor. Conscientiousness subdivides into two factors, achievement and control, as noted. The fourth factor, Extraversion, features its sociability rather than its dominance aspects. The intellect factor emphasizes aesthetics and ideas rather than giftedness per se. A sixth factor, emerging at Row 7 and featuring sincerity, modesty, and greed avoidance, looks a good deal like the added honesty-humility dimension of the HEXACO (Ashton & Lee, 2007).

In short, beginning with adjectives or scales led to generally similar structures, with similar although not identical factors related predominantly as lists rather than as hierarchies.

3.3. Using oblique rotation

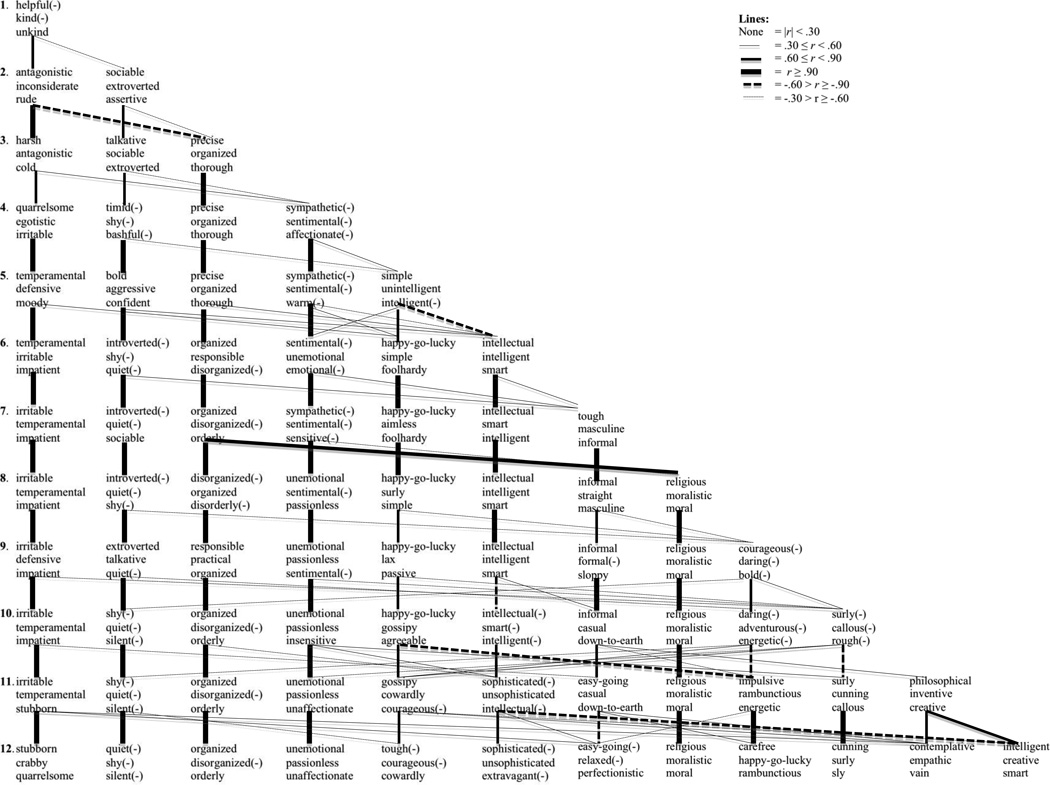

A reviewer of an earlier version of this paper wondered if the structure of these diagrams depended on the fact that the rotations were orthogonal rather than oblique. Although earlier experience (e.g., Goldberg, 1990) suggested that with large initial correlation matrices the two methods of rotation tend to yield similar results, as a check we used both methods for one of the analyses. Figure 3 represents the analysis of Figure 1 carried out using oblique rotations (via oblimin) rather than othogonal ones.

Figure 3.

The analysis of Figure 1 carried out using oblique rather than orthogonal rotation

For the most part, the oblique rotations yield a structure that resembles that of the orthogonal rotations: a persistence of factors once obtained, represented by correlations of .90 or more between adjacent levels; a new factor emerging at each level, usually, although not always, with minor contributions from one or more factors at the preceding level; occasionally a reversal of direction of a factor moving down a column. In fact, for the first 8 columns of Figures 1 and 3 the factors are essentially the same. Occasionally one of the highest-loading adjectives is different, or the order of the loadings is different, but clearly the oblique rotations of Figure 3 have led to the same general result as the orthogonal rotations of Figure 1, at least until we reach the last few factors, whose stability is doubtful in any case, according to the Cudeck-Browne criterion. These results do not, of course, imply that oblique versus othogonal rotation can never make a difference when matrices are large, but they support earlier research (Goldberg, 1990) in suggesting that the factors identified in studies of the present kind will tend to be quite similar by both methods. A notable difference between Figures 1 and 3 is the presence of many more cross-column correlations with the oblique than with the orthogonal rotations (only 4 cross-correlations of ± .30 or more in Figure 1, aside from those involved in establishing new factors, as against 24 in Figure 3). Allowing factors to be somewhat correlated has made it easier for a factor to correlate with factors in the next row other than its direct descendant.

3.4. Two indices of simplicity

Table 1 provides a summary of two indices of a diagram’s simplicity—first, a large number of correlations between adjacent levels that exceed ±.90, represented in the figures by thick vertical lines, and second, a small number of appreciable across-column correlations, represented by slanted lines. Thus, on the whole, list structures will tend to rank as simpler than hierarchical ones. The two criteria of simplicity are, of course, not independent, in the sense that if a factor at one level correlates above .90 with one at the next level, it cannot well have very large correlations with factors orthogonal to that one.

Table 1.

Two indices of diagram simplicity

| Figure and basis |

Rotation | Vertical rs > ± .90 |

Off-column rs > ± .30 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. adjectives | orthogonal | 56 | 19 |

| 2. scales | orthogonal | 49 | 29 |

| 3. adjectives | oblique | 49 | 55 |

First, it is evident that all the diagrams may be considered simple by these standards. There are 66 vertical lines in each figure; a large majority of these in all cases exceed ±.90 (the range is 74% to 85%). There are 425 potential off-line correlations, of which only a few are beyond ±.30 (5% to 13%).

Second, no very sharp divisions are evident in Table 1 between the diagrams based on adjectives and the one based on scales. In both cases, factors once emerging tend to persist, and many of them are present in all three diagrams. Major splits do sometimes occur, but are relatively infrequent. The most notable substantive difference between the scale- and adjective-based diagrams is the failure of the Neuroticism factor to emerge as such in the latter.

4. General discussion

What do Figures 1, 2 and 3 share, and what differentiates them? First, do the figures tell us that n personality factors are the best? No. They provide some information about what the factors might look like if one extracts varying numbers of them. A possibly comforting message is that after the first few, extracting an additional factor tends to leave the identity of the existing ones pretty much the same, and just adds a new one. There are exceptions, where two aspects of an existing factor split off as separate factors. An example would be the splitting apart of control and achievement aspects of the perfectionist factor at row 8 in Figure 2. But in general it appears that the arrangement of personality dimensions conforms more to a list than to a hiearchical structure. Comparisons of a general factor of personality to a hierarchically conceived cognitive g may thus require some caution. As previously noted, Revelle and Wilt (2013), using a method that assumes a hierarchical organization below a general factor, conclude that the cognitive domain is much more satisfactorily described in this manner than the personality domain.

Is the list produced by a sequential-factors analysis an unordered one? No. In general, one would expect larger factors that account for more covariance to emerge first, and narrower factors later. Thus there would be a tendency for a broad-to-narrow ordering of the factors from left to right in the diagram. However, because each layer introduces some new information, and rotation can redistribute the covariation in somewhat different ways, the order in which factors emerge initially can change from layer to layer.

How do the adjective- and scale-based diagrams compare? As we have seen, the structures are generally similar, and the factors obtained show resemblances but are not identical—most notably in the case of the Neuroticism factor. Why the differences? One reason, perhaps, is that structures based on adjectives are more directly influenced by the semantic structure of language than are those based on scales. In the one case, the score is derived from the rater’s response to a particular word; in the other, to his or her response to several sentences having a common focus—the items of the scale. An adjective can shift considerably in its connotative meaning from individual to individual (Loehlin, 1961); the meanings of the scale items should be less fluid. Thus each of the 184 scales should provide a more stable measurement, and one less influenced by verbal associations, than each of the 435 adjectives. However, whether the adjectives or the scales taken jointly provide a better assessment of personality traits remains a legitimate subject for debate.

What of prediction? Since each level incorporates all the information from the preceding levels and adds some, the prediction of external criteria should improve as one moves down the diagram adding factors, at least until one starts extracting largely idiosyncratic variance (i.e., 11 factors or so for the scales, 8 or so for the adjectives, according to the Cudeck-Browne criterion). That does not mean that more factors will always be better in practical assessment, where trade-offs become important (e.g., spending a certain amount of available testing time in measuring a few dimensions well or more numerous dimensions less precisely, or producing simpler but more easily comprehended reports as compared to more detailed but harder-to-grasp ones).

Finally, we believe that an approach like this one would be interesting to apply on a developmental or cross-cultural basis (cf. Osgood, May, & Miron, 1975). Would an analysis of data from young children amount to just going down a few levels in a diagram more or less like these, or would the organization be quite different? What would happen in an East Asian or African culture? If there were major developmental or cultural differences (or if there were not) this would surely affect the ways in which we elect to describe and comprehend personality, or assess it in different populations.

-

➢

Do personality traits mostly conform to lists or hierarchies?

-

➢

Data: adjective ratings and scores on basic personality inventory scales.

-

➢

Goldberg’s “bass-ackwards” method applied for series of 1 to 12 factors.

-

➢

List- rather than hierarchy-type structure predominantly observed.

Acknowlegement

Funds to support the second author were provided by Grant AG020048 from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allport GW, Odbert HS. Trait names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychological Monographs. 1936;47:1–171. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton MC, Lee K. Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2007;11:150–166. doi: 10.1177/1088868306294907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattell RB. Description and measurement of personality. New York: World; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrea RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PIR) Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cudeck R, Browne MW. Cross-validation of covariance structures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1983;18:147–167. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr1802_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM. Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology. 1990;41:417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. A factorial study of Psychoticism as a dimension of personality. In: Cattell RB, editor. Multivariate Behavioral Research. Special Issue. Progress in clinical psychology through multivariate designs; 1968. pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. An alternative “Description of personality”: The Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:1216–1229. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.6.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist. 1993;48:26–34. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. Doing it all bass-ackwards: The development of hierarchical factor structures from the top down. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Grucza RA, Goldberg LR. The comparative validity of 11 modern personality inventories: Predictions of behavioral acts, informant reports, and clinical indicators. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;89:167–186. doi: 10.1080/00223890701468568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilford JP. Unitary traits of personality and factor theory. American Journal of Psychology. 1936;48:673–680. [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC. Word meanings and self-descriptions. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1961;62:28–34. doi: 10.1037/h0044547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC. Component analysis versus common factor analysis: A case of disputed authorship. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:29–31. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2501_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maraun MD. Appearance and reality: Is the Big Five the structure of trait descriptors? Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;22:629–647. [Google Scholar]

- Musek J. A general factor of personality: Evidence for the Big One in the fivefactor model. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41:1213–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood CE, May WH, Miron MS. Cross-cultural universals of affective meaning. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Parent MC. Handling item-level missing data: Simpler is just as good. The Counseling Psychologist. 2013;41:568–600. [Google Scholar]

- Revelle W, Wilt J. The general factor of personality: A general critique. Journal of Research in Personality. 2013;47:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saucier G. Recurrent personality dimensions in inclusive lexical studies: Indications for a Big Six structure. Journal of Personality. 2009;77:1577–1614. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saucier G, Goldberg L. Evidence for the Big Five in analyses of familiar English personality adjectives. European Journal of Personality. 1996;10:61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A. Structure of mood and personality and their relevance to assessing anxiety, with emphasis on self-report. In: Tuma A, Maser JD, editors. Anxiety and the Anxiety Disorders. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1985. pp. 681–706. [Google Scholar]

- Thurstone LL. The dimensions of temperament. Psychometrika. 1951;16:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tryon RC. Cluster analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Waller N. A general method for computing hierarchical component structures by Goldberg’s Bass-Ackwards method. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41:745–752. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS. A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The intepersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:395–412. [Google Scholar]