Abstract

Multicomponent reaction (MCR) technology is now widely recognized for its impact on drug discovery projects and is strongly endorsed by industry as well as academia. However, still relatively few products based on MCRs are marketed or under development. This provides tremendous opportunities for organic chemists to shorten synthetic pathways thus reducing the cost-of-goods considerably. A recent example of the HCV drug Telaprevir is highlighted where introduction of two MCRs could lead to a shortening of the synthesis route by more than 50%.

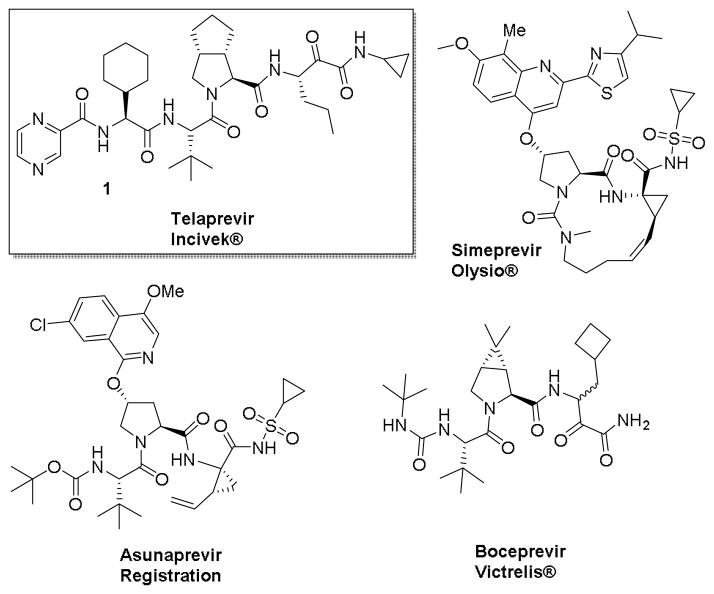

The ever growing structural complexity of modern drugs has led to an increase in the difficulty of synthetic efforts for their production. (Figure 1). This general trend can be rationalized as more complex proteins and enzymes are emerging as viable drug targets as well as an increasing need for higher selectivity and potency of compounds.

Figure 1.

Structural complexity of marketed or late-stage HCV NS3 inhibitors

The large scale GMP synthesis of complex drugs is almost automatically reflected in the considerably higher cost-of-goods. Sometimes, however, a cleverly designed synthetic pathway can lead to rapid, convergent, and cheaper syntheses of otherwise difficult and lengthy to access drug targets. An interesting recent case is the 2013 FDA approved hepatitis C NS3 protease inhibitor Telaprevir.

Hepatitis C is a viral infectious disease affecting more than 200 million people worldwide and is currently treated by a combination of PEGylated interferon and ribavirin. However, a significant number of patients do not respond to this therapy due to adverse effects or viral rebound due to resistant strains. The recent approval of two peptidic HCV NS3 protease inhibitors Telaprevir and Boceprevir shifted the HCV treatment paradigm and gives patients new and powerful treatment options. The reported technical synthesis of Telaprevir involves a lengthy, highly linear strategy relying on standard peptide chemistry and entails more than 20 linear steps.1 For example, the central bicyclic proline derivative is synthesized in racemic form via a nine-step sequence. The desired enantiomer is only obtained after chiral HPLC separation. Optimization of the synthesis of Telaprevir could significantly lower the production costs, thereby making this highly needed drug available to an increased proportion of the world population in the future.

Here we highlight the work of two independent groups towards significant improvements in the synthesis of the HCV drug Teleprivir 1. It has to be noted that both syntheses are currently being investigated for large scale preparation by a pharmaceutical company. Recently Orru and Euijter et al. from the VU University Amsterdam disclosed a highly efficient and stereoselective synthesis of Telaprevir (Incivek®) employing the combined use of biocatalysts and multicomponent reactions (MCRs). The synthesis comprises of only eleven steps in total compared to twenty-four in the originally reported procedure.2–4 The significance of the work is a reduction by more than half the steps while comprising a “greener” process which can be additionally translated into a considerably lower cost-of-goods.

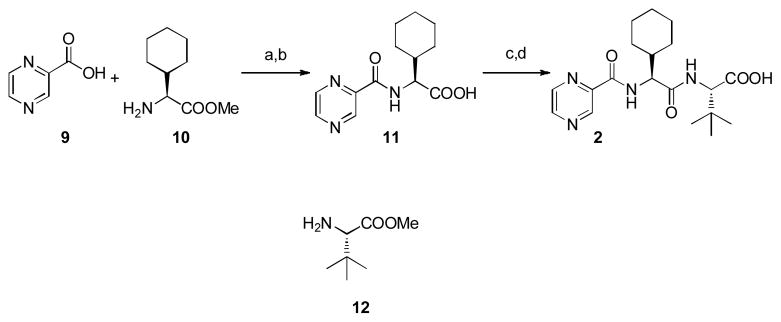

A retrosynthetic analysis of 1 involving two MCRs is presented in (Figure 2). The required starting materials for the key Ugi-type 3CR were the carboxylic acid 2, cyclic imine 3, and isocyanide 4. The acid 2 could be accessed by standard peptide chemistry, while chiral imine 3 was generated in situ from commercially available 5 by the enzyme MAO-N catalyzed oxidation. The isocyanide 4 was accessed via a Passerini three-component reaction (P-3CR) of compounds 6, 7, and acetic acid.

Figure 2.

MCR retrosynthetic analysis of Telaprevir (Incivek®)

Coupling of pyrazinecarboxylic acid 9 and L-cyclohexylglycine methyl ester 10 followed by saponification afforded 11 in excellent yield. Subsequent coupling with L-tert-leucine methyl ester 12 and saponification furnished the required optically pure acid 2. The Orru and Ruijter group was able to significantly increase both the atom and step economy and the overall yield (74% vs. 11% over four steps) of acid 2 compared to the already known synthesis1 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Synthesis of acid 2. Reagents and conditions: a) BOP, Et3N, DMF, 98% b) NaOH, THF/H2O/MeOH, 95% c) H-Tle-OMe 12, EDC, HOAt, DMF, 84% d) NaOH, THF/H2O/MeOH, 95% BOP = Benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy-tris-(dimethylamino)-phosphonium hexafluorophosphate, DMF = Dimethylformamide, EDC = 1-Ethyl-3-(3 dimethyl-aminopropyl)carbodiimide, HOAt = 1-Hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole.

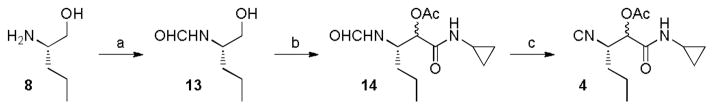

The construction of the isocyanide fragment 4 was done in three steps in which a Passerini 3-component reaction (P-3CR) played a key role. Commercial (S)-2-amino-1-pentanol 8 was transformed to formamide 13 by N-formylation. Following the work of Ngouansavanh and Zhu,5 the in situ oxidation of alcohol 13 and a P-3CR was performed in one-pot giving access to 14. Both the alcohol oxidation and the Passerini reaction were performed in CH2Cl2. Thus, one-pot Dess–Martin oxidation/Passerini reaction of 13 furnished 14 in 60% yield. Dehydration then afforded the required isocyanide 4 in very good yield (87%). Importantly no racemization of the C3 stereocenter in 4 was observed. The diastereomeric stereocenter of 4 in C4 will be removed at a later stage of the synthesis. The crucial building block 4 was thus accessible in only three steps from commercial available starting materials (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Synthesis of isocyanide 4. Reagents and conditions: a) EtOCHO, Δ, 99% b) DMP, cyclopropyl isocyanide, CH2Cl2, 60% c) triphosgene, NMM, CH2Cl2, −30°C, 87% DMP = Dess–Martin periodinane, NMM = N-Methylmorpholine.

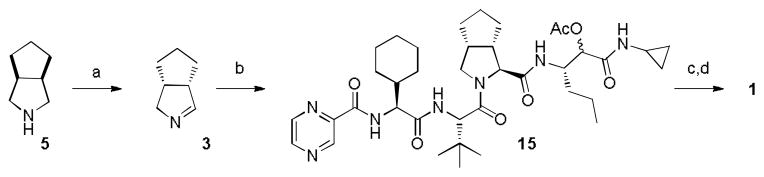

The last step towards the three-component Ugi-type coupling envisaged in the retrosynthesis is described below. The, commercial amine 5 was oxidized to imine 3 (94% ee) by MAO-N as previously described.6–8 Reacting cyclic Schiff base 3 with the acid 2 and the isocyanide 4 give the advanced intermediate 15. Finally, cleavage of the acetate followed by Dess–Martin oxidation gave Telaprevir 1 as a 83 : 13 : 4 mixture of diastereomers, with one minor diastereomer derived from the incomplete stereoinduction of the Ugi-type 3CR, and the other from the minor enantiomer of imine 3. Chromatography allowed straightforward separation of the diastereomers to afford pure Telaprevir 1 in 80% yield over the last two steps (Figure 5). The above synthesis comprises of only eleven steps in total (technical 24), with seven steps in the longest linear sequence and a yield of 45% starting from 10. In conclusion the MCR approach that the group of Orru and Ruijter propose gives access to Telaprevir 1 in higher yields and with higher efficiency than any previously disclosed process. Furthermore, the chiral information used for the preparation is derived from readily available and inexpensive building blocks, making the process a highly effective approach to such prolyl dipeptides.

Figure 5.

Synthesis of 1. Reagents and conditions: a) Monoamine oxidase (MAO-N), 100mM KPO4 buffer, pH = 8.0, 37 °C b) 2, 4, CH2Cl2, 76% c) K2CO3, MeOH; d) DMP, CH2Cl2, 80% over two steps DMP = Dess–Martin periodinane.

Recently Banfi et al. disclosed an alternative pathway to Telaprevir combining biocatalysis and MCRs.9–10 Their strategy involved the construction of the backbone of the C-terminus of the target compounds while subsequently forming the bicyclic pyrrolidine. Biocatalytic desymmetrization of meso diol 16 followed by a short sequence of standard transformations gives alcohol 17.11

Next in situ oxidation of 17 to the aldehyde is done in a Passerini–reaction to afford 18 as a mixture of diastereoisomers ratio of a/b= 2:1. After the azide reduction of 18a, an intramolecular O to N migration occurs to give the amidoalcohol 19. Cyclization via the mesylate 20 proceeded in excellent yields to give 21 (Figure 6). After deprotection and oxidation, aldehyde 22 is formed. A Passerini reaction takes place in the next step involving compound 22, cyclopropyl isocyanide 24, and acetic acid 25 producing compound 23, which after three steps is converted into Telaprevir. As an additional benefit of the synthesis the volatile cyclopropylisocyanide is not isolated but produced in situ from the formamide precursor. The second route by Banfi et al. although longer than the first one is highlighting alternative synthetic processes which might find use due to intellectual property management and/or better yields and stereoselectivities.

Figure 6.

Synthesis of 1 by Banfi et al. Reagents and conditions: a) (i) DMSO, oxalyl chloride in DCM (ii) (S)-2-isocyanopentyl benzoate, boric acid in CH3CN, 92% diastereoisomeric mixture a/b= 2:1 b) (i) PPh3/H2O (ii) NMM, L-Boc-t-Leucine, PyBoP, 78% c) methanesulfonyl chloride, Et3N in DCM d) (i) NaH, DMF, 78% e) 7, 24 and 22 in DCM, r.t. DMF = Dimethylformamide, NMM = N-methylmorpholine, PyBoP = benzotriazol-1-yl-oxytripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate.

The reduction of steps of the technical total synthesis of Telaprevir by more than ½ using two convergent MCRs in combination with biocatalysis is indeed an intriguing piece of applied chemistry. It should be noted that Telaprevir is an outstandingly complex example of process improvement by MCR, however an increasing number of drugs have been recently synthesized by this technology.12–17

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding is provided for AD by the National Institute of Health (1R21M087617-01), European Lead Factory (IMI under grant agreement n° 115489) and the Qatar National Research Foundation (NPRP6-065-3-012).

References

- 1.Yip Y, Victor F, Lamar J, Johnson R, Wang QM, Glass JI, Yumibe N, Wakulchik M, Munroe J, Chen SH. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:5007. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Znabet A, Polak MM, Janssen E, de Kanter FJ, Turner NJ, Orru RV, Ruijter E. Chem Commun. 2010;46:7918. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02823a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruijter E, Orru R, Znabet A, Polak M, Turner N. 2011/103932. VUA; WO. 2011

- 4.Ruijter E, Orru R, Znabet A, Polak M, Turner N. 2011/103933. VUA; WO. 2011

- 5.Ngouansavanh T, Zhu J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:3495. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Köhler V, Bailey KR, Znabet A, Raftery J, Helliwell M, Turner NJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:2182. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mijts B, et al. 2010/008828. Codexis, Inc; WO. 2010

- 8.Znabet A, et al. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:5289–5292. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banfi L, Basso A, Moni L, Riva R. Eur J Org Chem. 2014:2005–2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morana F, Basso A, Riva R, Rocca V, Banfi L. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:4563. doi: 10.1002/chem.201300023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riva R, et al. 2013/178682. Chemo Eberica, S.A; WO. 2013

- 12.Dömling A, Wang W, Wang K. Chem Rev. 2012;112:3083. doi: 10.1021/cr100233r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao HP, Dömling A. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:12296. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H, William S, Herdtweck E, Botros S, Dömling A. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2012;79:470. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2011.01288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borthwick AD, et al. J Med Chem. 2012;55:783. doi: 10.1021/jm201287w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clader JW, et al. J Med Chem. 1996;39:3684. doi: 10.1021/jm960405n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burnett DA, Caplen MA, Davis HR, Burrier RE, Clader JW. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1733. doi: 10.1021/jm00038a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.