Abstract

The landscape of union formation has been shifting; Americans are now marrying at the highest ages on record and the majority of young adults have cohabited. Yet little attention has been paid to the timing of cohabitation relative to marriage. Using the National Survey of Families and Households and 4 cycles of the National Survey of Family Growth, the authors examined the timing of marriage, cohabitation, and unions over 20 years. As the median age at first marriage has climbed, the age at cohabitation has remained stable for men and women. The changes in the timing of union formation have been similar according to race/ethnicity. The marked delay in marriage among women and men with low educational attainment has resulted in a near-convergence in the age at first marriage according to education. The authors conclude that the rise in cohabitation has offset changes in the levels and timing of marriage.

Keywords: cohabitation, demography, education, ethnicity, marriage, social trends

The landscape of union formation in the United States has been transforming as Americans wait longer to get married, and the median age at first marriage in the United States is at a historic high point (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Over the past two decades, the median age at first marriage has increased by at least 2 years, from 24.1 for women and 26.3 for men in 1991 to 26.5 for women and 28.7 for men in 2011 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Even though young women and men are waiting longer to tie the knot, this does not mean they are waiting until their late 20s to form coresidential relationships. Today, the majority (66%) of young adults have spent some time in a cohabiting union (Manning, 2013). About two-fifths (41%) of women who first married in the early 1980s cohabited prior to entering marriage versus the two thirds (66%) of first marriages today that are preceded by cohabitation (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2011; Manning, 2013). Although much is known about the prevalence of cohabitation, relatively little attention has been paid to the median age at first cohabitation and changing trends over time.

Drawing on the 1987–1988 National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH; http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/nsfh/) and four cycles of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg.htm), we assessed change in the proportion forming unions and median age at union formation with specific attention to the median age at first cohabitation. The fundamental question we addressed was this: As the median age at first marriage has increased, how have the median ages at first cohabitation and first union formation changed? On the basis of arguments that family change is not uniform for all Americans, reflecting a growing social divide in family life (Cherlin, 2013; McLanahan, 2004), we expected greater shifts in the timing of marriage than cohabitation among the most disadvantaged respondents.

BACKGROUND

The rise in the median age at first marriage is well documented, but little is known about whether there has been an accompanying change in the median ages at first cohabitation and first union formation. Are Americans waiting longer to form any union, or are they just waiting longer to form marital unions?

One reason the median ages at cohabitation or union formation have received little attention is that there are few data sources available to document these shifts. The median age at first marriage is often calculated using indirect methods as specified by Shryock, Siegel, and Larmon (1973). These methods require knowledge about the proportion of the population that has been married at specific age ranges. This information has been available for some time from U.S. census data as well as Current Population Survey (CPS) data. These indirect methods cannot be used to assess median age at cohabitation because the Census and CPS do not include indicators of the proportion of the population that has cohabited at specific age groups. Starting in 2000, the Census included “unmarried partner” as a household membership category but did not obtain a critical piece of information: the proportion of the population that has ever cohabited. Furthermore, directly assessing changes in the median age at first cohabitation requires survey data that directly ascertain the age at first cohabitation.

In response to the growth in cohabitation, starting in the late 1980s a few nationally representative surveys, such as the NSFH and NSFG, expanded the roster of household relationships to include cohabitation. These and now many additional surveys have included direct questions about the start and end dates of cohabitation, akin to measures of marriage. Thus, using nationally representative survey data, we were able to assess changes in direct reports of ages at marriage as well as cohabitation.

On the basis of data collected 25 years ago in the 1987–1988 NSFH, the median age at first cohabitation was 21 for women (Child Trends, 2006), but little is known about the median age at first cohabitation today. We expect there may have been some changes in the median age at first cohabitation in part because over a 23-year period there has been an 82% increase in the proportion of women who ever cohabited (Manning, 2013). In 1987, one third of women ages 19–44 ever cohabited (Bumpass & Sweet, 1989) and, recently, over half (60%) of 19- to 44-year-old women had spent some time in a cohabiting union (Manning, 2013). The median age at first cohabitation may not be increasing as rapidly as the median age at first marriage because the barriers to cohabitation are not as high as those to marriage. Motivations to cohabit have tended to be based on relational prospects and have not carried the same prerequisites, such as stable economic prospects, as marriage (Huang, Smock, Bergstrom-Lynch, & Manning, 2011; Sassler, 2004). To date, researchers have not investigated whether there has been an increase in the median age at first cohabitation or first union formation even though the proportion of women who have ever cohabited has increased dramatically.

Evidence supporting the theme of diverging destinies, defined as growing racial/ethnic and social class differentials in family behavior, often has focused on the disproportionate rise in nonmarital fertility among the most disadvantaged individuals versus the quite stable, low levels of unwed childbearing among college graduates (e.g., Cherlin, 2009; Ellwood & Jencks, 2004; McLanahan, 2004; Mincieli, Manlove, McGarrett, Moore, & Ryan, 2007; South, 1999). Similarly, there appears to be a divergence in marriage trends as growth in nonmarriage has been greatest among the most disadvantaged (Ellwood & Jencks, 2004; Furstenberg, 2009; Schoen, Landale, Daniels, & Cheng, 2009). We investigated whether the delay in marriage entry characterizing advantaged groups extends to cohabitation formation as well; that is, has the rising age at marriage coincided with a shift in the timing of first cohabitation, or has the median age at first cohabitation remained stable? Bumpass, Sweet, and Cherlin (1991) suggested that the delay in marriage entry evident in the 1970s and 1980s was offset by corresponding increases in cohabitation formation, meaning that first union formation was relatively unchanged over time. Instead, the type of first union formed had shifted from marriage to cohabitation.

Racial and ethnic differentials in the median age at first marriage are well known. Some of the differentials are due to lower levels of ever marrying among certain subgroups of the population. The proportion of married individuals in the population has declined faster among Black women than White women (Ellwood & Jencks, 2004). For example, Black women have first-marriage rates that are about half the levels experienced by White or Hispanic women. In 2010, the first-marriage rates per 1,000 never-married women were 22.1 among Black women, 52.4 among White women, and 42.6 among native-born Hispanic women (Payne & Gibbs, 2011). Indeed, the racial and ethnic gap in the age at first marriage persists and actually has widened (Child Trends, 2006; Fitch & Ruggles, 2000; Payne, 2012; Simmons & Dye, 2004). Starting in 1980, the racial gap in age at first marriage reached 2 years. In 2010, Black women had a median age at first marriage that was about 4 years greater (30.3) than the age at first marriage experienced by White and Hispanic women (26.4 and 25.9, respectively; Payne, 2012). For these reasons, we anticipated that the median age at first marriage is highest among Blacks and that the rise has been steepest for Blacks compared to Whites and Hispanics.

The timing of marriage follows an education gradient. In 2010, the first-marriage rate was notably highest among college-educated women (73.7 per 1,000 unmarried women) and ranged between 30.4 and 39.4 among women with less than high school and only some college education (Payne & Gibbs, 2011). The financial resources provided by men have weakened, and women have been increasingly valued for their economic prospects (Lichter & Qian, 2004; Raley & Bratter, 2004). In 2010, the median age at first marriage was 24 among women with less than a high school degree and 28 among college-educated women (Payne, 2012). Furthermore, half of women without a high school degree were married by age 25, in contrast to only 37% of women with a college degree, but by age 35 the pattern reversed such that 72% of women without a high school degree had married and 84% with a college degree had married (Copen, Daniels, Vespa, & Mosher, 2012). Although more educated women tend to marry at later ages compared with less educated women, more educated women are ultimately the most likely to ever marry. This education gap in age at first marriage has persisted over time (Child Trends, 2006; Ellwood & Jencks, 2004; Simmons & Dye, 2004), but it could be narrowing as more disadvantaged Americans delay marrying to meet the economic prerequisites for marriage (Gibson-Davis, 2007; Smock, Manning, & Porter, 2005).

Over the past 20 years, the proportions of individuals who have ever cohabited rose somewhat more quickly among Whites and Hispanics (94% and 97% increases over time, respectively) than among Blacks (67% increase over time; Bumpass & Sweet, 1989; Manning, 2013). In 1987, the average age at first cohabitation was 21 for Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics (Child Trends, 2006). The current differential in the proportion of women who have ever cohabited according to race and ethnicity continues to be relatively small, ranging from 59% among Hispanics to 62% among Whites. We did not expect a diverging-destinies perspective to be operating as strongly for cohabitation as marriage because, unlike marriage, there are few economic barriers to cohabitation. Thus, we expected a continuation of little variation in the median age at first cohabitation according to race and ethnicity.

In contrast, the education divide in cohabitation experience has been increasing. In 2009–2010, nearly three quarters of women without a high school degree had ever cohabited, versus half of women with a college degree (Manning, 2013). The education group that saw the greatest increase in cohabitation was women with a high school degree, who experienced over a 100% increase in cohabitation experience over the past 23 years (Bumpass & Sweet, 1989; Manning, 2013). Two decades ago, the average age of first cohabitation among college graduates was 24 versus 19 for persons with less than a high school degree (Child Trends, 2006). Because the economic barriers to marriage are greater than those for cohabitation, we expected a less steep education gradient for cohabitation than marriage.

Given the changes in marriage and cohabitation, we thought it was important to assess union formation and not specifically just cohabitation or marriage. Few studies have jointly considered variation in the timing of marriage and cohabitation. Raley (1996) reported that the race gap in the timing of union formation was about half the difference in the timing of first marriage. Thus, there are racial differences in first union formation, but they are considerably smaller than racial differences in the timing of marriage. We examined trends in the levels and timing of union formation, paying attention to variation by race and ethnicity and education. Moreover, we were able to examine these patterns separately for women and men. All data for women came from the NSFG, whereas for men we combined data from the first wave of the NSFH with data from the NSFG (because men were not interviewed in the NSFG prior to 2002). There has been a consistent gender gap in median age at first marriage of roughly 2 years (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011), but whether the median ages at first cohabitation or first union formation differ by gender are unknown.

In this study, we asked a fundamental question: During a period when the median age at first marriage has increased and the prevalence of cohabitation has grown, has the median age at first cohabitation increased? Americans may be delaying all union formations, or they may simply be delaying marriage. We showcase change over time in whether the first coresidential union was cohabitation or marriage and the proportion of each age group who were married, cohabiting, or in a union at each interview. We also investigated whether these changes are consistent with the diverging-destinies perspective; we anticipated a stronger divide in marriage than cohabitation. Given that the economic bar to marriage has been rising, we expected to observe widening racial and education gaps in the proportions of married individuals and an increasing median age at first marriage for members of racial/ethnic minority groups and individuals with less education. The economic prerequisites for cohabitation are lower than those for marriage, and thus cohabitation trends should be less differentiated by race/ethnicity and education. In fact, there is evidence of consistency in the levels of cohabitation across racial and ethnic subgroups and we expected similar ages at first cohabitation among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. We expected that the established education gradient in levels and age at entry into cohabitation will continue as more highly educated men and women will continue to adhere to more traditional family behavior and wait until their education is complete prior to forming a union.

METHOD

For our analysis of women’s age at first union formation we used data from Cycles 4 through 6 and the 2006–2010 continuous data set of the NSFG, a national representative cross-sectional survey. Parallel analyses of men’s age at first union formation relied on the 1987–1988 NSFH along with Cycle 6 (2002) and the 2006–2010 NSFG data. The NSFH and NSFG are considered key sources of data on fertility and family in the United States. The goal of the NSFH was to provide a broad range of information on the American family. Central to the NSFG’s mission is the production of reliable national statistics and comparable trend data on factors related to pregnancy and birth rates—and in more recent cycles—marriage, divorce, and cohabitation.

The 1987–1988 NSFH data were drawn from a household based survey of 5,226 men that included oversamples of members of racial/ethnic minority groups, one-parent families, families with stepchildren, cohabiting families, and recently married persons, with a response rate of 74.3%. Cycle 4 of the NSFG, conducted in 1988, included interviews with 8,450 civilian noninstitutionalized women age 15–44 with oversamples of Black women and a response rate of 79%. Cycle 5 of the NSFG, conducted in 1995, included interviews with 10,847 civilian noninstitutionalized women age 15–44 with oversamples of Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black women and a response rate of 79%. Cycle 6 of the NSFG, conducted from March 2002 through February 2003, included interviews with a total of 12,571 civilian noninstitutionalized men (n = 4,928) and women (n = 7,643) age 15–44 with oversamples of Blacks, Hispanics, and teenagers (age 15–24) of all races and a combined response rate of 79%. The most recent cycle, 2006–2010 NSFG, was conducted July 1, 2006, through June 2010. It included interviews with a total of 22,682 civilian noninstitutionalized men (n = 10,403) and women (n = 12,279) age 15–44 with oversamples of Blacks, Hispanics, teenagers (age 15–24), and female respondents and had a combined response rate of 77%.

Measures

Proportion of respondents married, cohabiting, or in a union

To provide illustrations of the proportion respondents who had ever married, cohabited, or lived in a union, we computed estimates according to 5-year age intervals across interview dates. These findings present birth cohort shifts over time in union formation patterns. We also calculated the proportion of women age 35–44 who had ever married, cohabited or lived in a union according to race/ethnicity and education level. These estimates focused on women who are past the typical first union formation age. For the sake of parsimony we limit the figures we present to women.

We computed median ages at first marriage, first cohabitation, and first union for women and men by race/ethnicity and educational attainment, where applicable. Questions specific to cohabitation were explicitly collected starting with Cycle 4 (1988). Because the NSFH and NSFG obtained the exact age at first union formation and the exact date at which a first cohabitation or marriage was experienced (in continuous month format), we were able to estimate a direct measure of the median age at first cohabitation, marriage, and union formation by enumerating unions that occurred in a specified range of years for each time point (1983–1988 (men)/1984–1988 (women), 1991–1995 (women only), 1998–2002 (men and women), and 2006–2010 (men and women) by age at union as outlined in Shryock, Siegel, and Larmon (1975), using the following formula:

where L = lower limit of median class, n1 = number of frequencies to be covered in median class to reach middle item, n2 = number of frequencies in median class, and i = width of median class.

The term median class refers to the age in whole years by which half the sample has married. For example, 3,764,946 women in the NSFG 2006–2010 wave first married between the years 2006 and 2010. The age at which half of these women (n = 1,882,472.8) first married was 25 years (the lower limit of the median class). To determine the number of frequencies to be covered in the median class to reach the middle item (median age), we subtracted the cumulative number of first marriages at age 24 (1,551,052.9) from half the cumulative number of all first marriages (1,882,472.8 − 1,551,052.9 = 331,419.9). We then divided the result (331,419.9) by the number of first marriages to women age 25 = 387,071.5 (the number of marriages in the median class) and added the result to the lower limit of the median class (25) for a resulting median age at first marriage of 25.9 years.

The annual estimates of the median age at first marriage provided by the U.S. Census Bureau (utilizing CPS and American Community Survey data) used an indirect method that was based on the proportion of people who had ever married for 5-year age groups ranging from 15 to 54 and allowed for the estimation in data sets that did not provide age at a specific event (Shryock et al., 1973). As discussed above, this method cannot be used to study cohabitation because of data limitations. The direct method is more dependent on the age composition of the population than the indirect method. Furthermore, the direct method does not account for the proportion of women marrying by a given age. To mitigate this issue, we present the proportions marrying and cohabiting by age group.

To maximize sample sizes, we chose to compute the median ages at first cohabitation, marriage, and union formation for 5-year intervals as opposed to single-year intervals (e.g., age at all first unions occurring from 1984 to 1988). Analyses produced a range of cell sizes for women (from n = 67 to 1,276), all adequate for producing reliable estimates. Cycle 4 of the NSFG did not oversample Hispanic women, and thus the cell sizes to produce the median ages of these women was slightly smaller than those of Blacks and Whites in Cycle 4, as well as estimates in subsequent cycles. Among men, the sample sizes ranged from 60 to 678. We do not provide time trends for Hispanic men because of small sample sizes in the NSFH among men who formed a union between 1983 and 1988. The small Hispanic sample sizes also inhibited the disaggregation of foreign-born and native-born respondents.

Our results were direct indicators of median ages of first marriage, cohabitation, and union formation derived from the ages of all first unions that occurred in years 1984–1988 for women derived from Cycle 4 (1988) and 1983–1988 for men derived from NSFH, 1991–1995 for women derived from Cycle 5 (1995), 1998–2002 for women and men derived from Cycle 6 (2002), and 2006–2010 for women and men derived from the 2006–2010 continuous NSFG. Each respondent’s century-month age at first marriage, cohabitation, and union were converted to age in years. Typically, the age at first cohabitation was less than the age at first marriage because most first cohabitations occurred prior to first marriage, but some first cohabiting unions occurred after a first marriage ended, and for this reason some of the estimates of median age at first union are actually lower than either the median ages at first marriage or cohabitation.

Estimates were computed separately by race and ethnicity and educational attainment. We categorized race/ethnicity into three groups: (a) Hispanic, (b) non-Hispanic White, and (c) non-Hispanic Black. The ethnicity of respondents was ascertained differently across cycles of the NSFG and NSFH. In NSFG Cycle 4, all respondents were asked to identify their race and then asked to specify their national origin. Respondents who self-identified their national origin as Puerto Rican, Cuban, Mexican American, Central or South American, or Spanish were coded as Hispanic. In the NSFH, respondents were asked to select the group that best described them: Black White—not of Hispanic origin; Mexican American, Chicano, Mexicano; Puerto Rican; Cuban; other Hispanic; American Indian; Asian; or “other.” Those who described themselves as Mexican American, Chicano, Mexicano, Puerto Rican, Cuban, or other Hispanic were coded as Hispanic. In NSFG Cycles 5 and 6, as well as the NSFG 2006–2010 cycle, respondents were asked to identify their race. In NSFG Cycle 5, respondents were directly asked if they were of Hispanic or Spanish origin. Cycle 6 and questions for 2006–2010 asked respondents directly if they were Hispanic, Latina, or of Spanish origin. If a respondent reported being of Hispanic descent (or any of its survey round derivations) they were coded as 1, Hispanic. Of the remaining respondents, those who self-identified their race as White or Black were coded as such, meaning those coded as White were non-Hispanic White and those coded as Black were non-Hispanic Black. Unfortunately, we were not able to account for nativity status across the cycles of the NSFG. Respondents who identified their race as “other” were excluded from the analyses because of small sample sizes.

Education was coded into four categories: (a) no high school diploma or GED, (b) high school diploma or GED, (c) some college with no degree or associate’s degree, and (d) bachelor’s degree or higher. This categorization allowed sufficient detail and was available across the cycles of the NSFG as well as the NSFH. Cycle 4 had two questions specific to respondents’ completed level of education: (a) “What is the highest grade or year of regular school or college you have ever attended?” and (b) “Did you complete that grade or year?” Beginning with Cycle 5 (1995), more detailed information on the timing of respondents’ educational experiences was gathered. In the NSFH, completed education is a constructed variable that provides a summary of the respondents’ educational experience, integrating information on both highest grade completed and degrees earned.

Analytic Sample

The analytic sample was limited to women and men age 15 through 44. Among women, the trend covers a 20-year span, 1984–1988 to 2006–2010, with four data points. The time trend for men covers a 21-year span with three data points: (a) 1983–1988, (b) 1998–2002, and (c) 2006–2010. Women and men who experienced a first marriage, cohabitation, or union prior to age 15 were excluded to provide results that are more comparable to other national estimates of the median age at first marriage generated from the Decennial Census, CPS, and American Community Survey data. The upper age limit of 44 was an artifact of the NSFG’s sampling frame of women and men age 15–44. Given that most women and men who marry or cohabit have first formed their union prior to age 44, this age limit should have had a very minimal or no impact on our estimates of median age at first union formation.

RESULTS

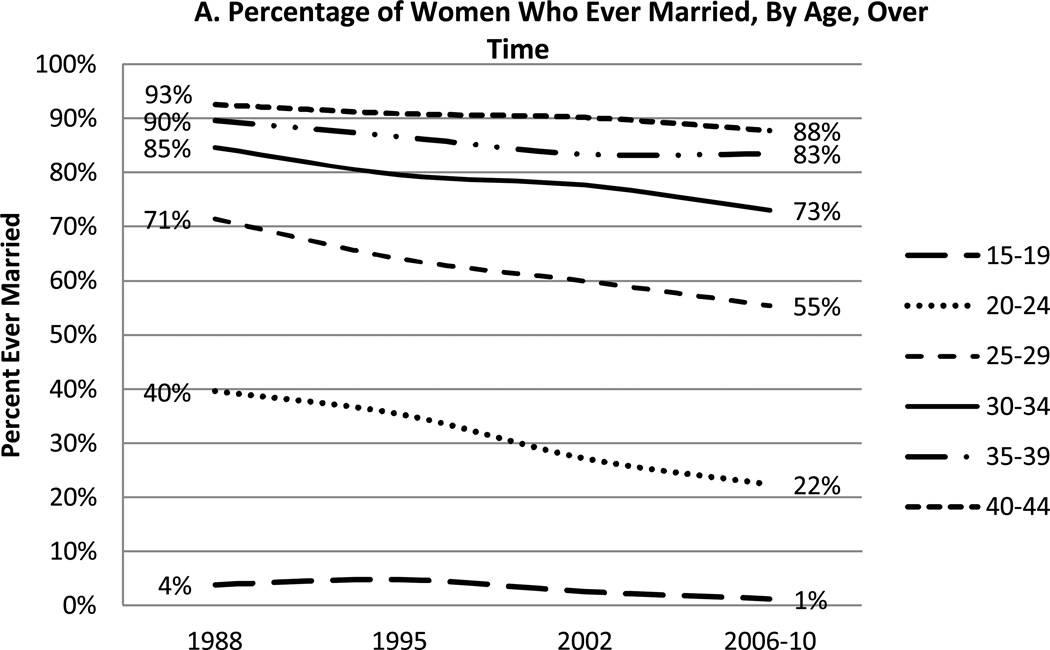

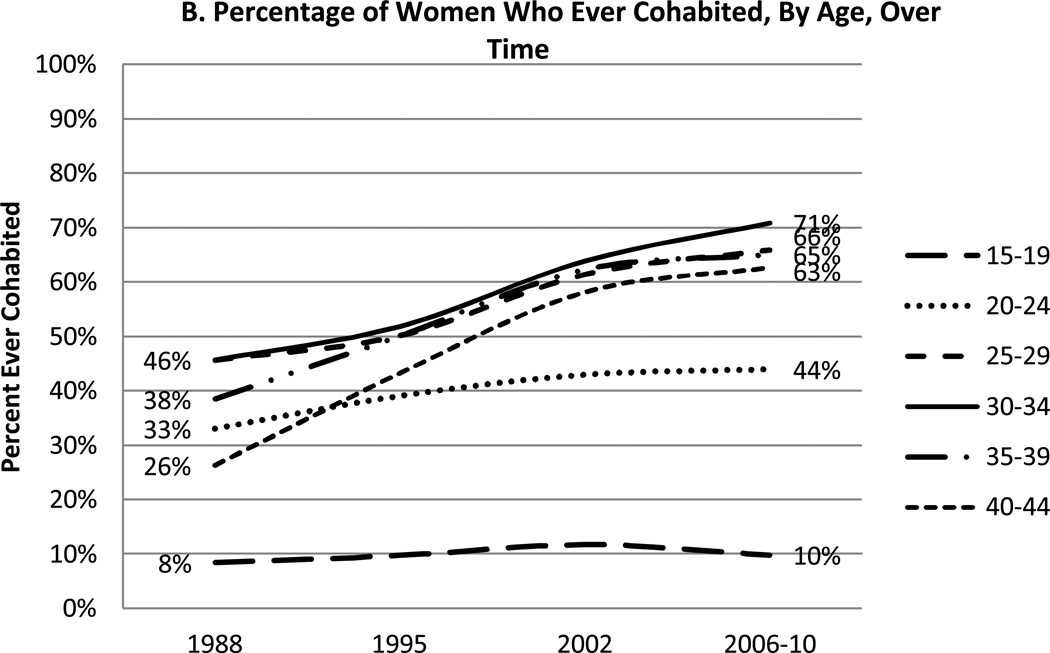

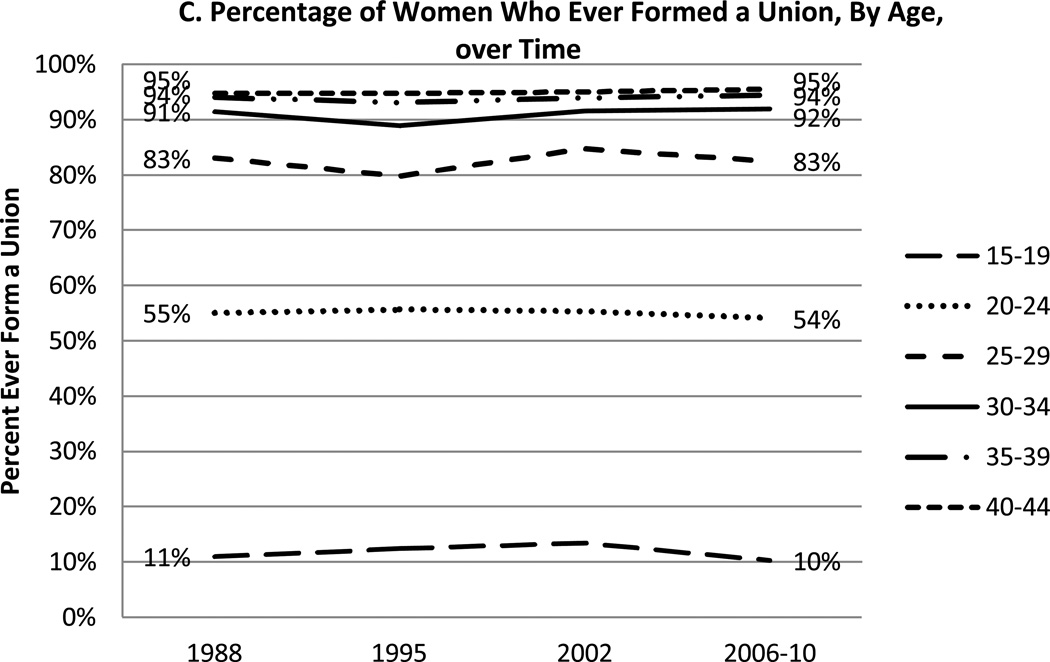

The median ages at first marriage, cohabitation, and union, and the percentages of first unions that started as cohabitations for each time period for women and men are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. Consistent with prior research, the median age at first marriage increased over time for women, from age 22.9 in the late 1980s to 25.9 in the late 2000s, and for men, from 24.7 in the late 1980s to 27.6 in the late 2000s. These changes are also reflected in online Figure A on the Journal of Marriage and Family website (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1741-3737), which depicts declines in the percentage of women ever married at 5-year age intervals. By ages 40–44, the percentage of women who have ever married declined slightly, from 93% in the late 1980s to 88% in the late 2000s.

Table 1.

Women’s Median Age (in Years) at First Marriage, Cohabitation, and Union Over Time

| Variable | 1984–1988 | 1991–1995 | 1998–2002 | 2006–2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first marriage | 22.9 | 23.6 | 24.9 | 25.9 |

| Age at first cohabitation | 22.8 | 21.9 | 22.2 | 21.8 |

| Age at first union | 21.9 | 21.6 | 22.0 | 22.2 |

| First union cohabitation (%) | 58.8 | 64.9 | 70.8 | 73.7 |

Note: Columns reference the period in which unions were formed.

Table 2.

Men’s Median Age at First Marriage, Cohabitation, and Union Over Time

| Variable | 1983–1988 | 1991–1995 | 1998–2002 | 2006–2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first marriage | 24.7 | 26.5 | 27.6 | |

| Age at first cohabitation | 23.9 | 23.5 | 23.5 | |

| Age at first union | 23.4 | 23.6 | 23.7 | |

| First union cohabitation (%) | 60.3 | 70.8 | 82.2 |

Note: Columns reference the period in which unions were formed.

In contrast, the median age at first cohabitation did not shift much over the past 30 years. Women’s median age at first cohabitation in the late 1980s was 22.8, and in the late 2000s it was just 1 year younger, at 21.8. We observed a similar trend among men, whose median age at first cohabitation was 23.9 in the late 1980s and 23.5 in the late 2000s. Online Figure B shows growth in the proportion of each age group who had ever experienced cohabitation, with the greatest increases in the proportion of women who had ever cohabited among women age 25 and older.

It appears the delay in marriage formation was offset by younger entry into cohabitation because the rise in the median age at marriage was nearly 3 years versus no change or a decline for median age at cohabitation. Taken together, the age at union formation remained stable and paralleled the trend in the median age at first cohabitation. Online Figure C shows the proportion of women who had ever formed a union has not shifted over time, providing further evidence that cohabitation has offset the decline in marriage. The median ages at union formation in the late 1980s were 21.9 for women and 23.4 for men and, in the late 2000s, 22.2 for women and 23.7 for men. Thus, the gender gap in age at first marriage and cohabitation persisted. Women and men increasingly favored cohabitation as their first coresidential union type, rising from 59% of women in the mid-1980s to nearly three-fourths (74%) in the late 2000s. Similarly, the share of men whose first union was cohabitation rose from 60.3% in the 1980s to 82.2% in the late 2000s. It is notable that a small share of first cohabitations occurred after a marriage ended.

The race and ethnic divergence in marriage is illustrated in Figure 1. The proportion of 35- to 44-year-old women who had ever married, according to race and ethnicity, declined most sharply for Black women. In the late 1980s, 73% of Black women age 35–44 had ever married, but by the later 2000s only 66% had ever married. Patterns of union formation for Hispanic, White, and Black women and men are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Median age at first marriage increased for each race and ethnic group in a similar manner, with about a 3-year increase for each group. During the late 2000s, the median ages at first marriage were 25.6 for Hispanic women, 25.7 for White women, and 27.0 for Black women. Among men, the corresponding figures were 29.9 for Hispanics, 27.1 for Whites, and 28.4 for Blacks. The retreat from marriage was most evident among Blacks, with high ages at first marriage among those who married and nearly one third not marrying.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Women (Ages 35–44) Who Ever Married, By Race/Ethnicity, Over Time.

Table 3.

Women’s Median Age at First Marriage, Cohabitation, and Union by Race and Ethnicity

| Variable | 1984–1988 | 1991–1995 | 1998–2002 | 2006–2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age first marriage | ||||

| Hispanic | 23.1 | 22.5 | 23.9 | 25.7 |

| White | 22.8 | 23.6 | 24.8 | 25.6 |

| Black | 24.0 | 25.3 | 26.9 | 27.0 |

| Age first cohabitation | ||||

| Hispanic | 22.3 | 20.8 | 21.0 | 20.9 |

| White | 22.9 | 21.9 | 22.3 | 21.8 |

| Black | 22.9 | 23.4 | 23.1 | 22.6 |

| Age first union | ||||

| Hispanic | 21.3 | 20.6 | 21.2 | 21.2 |

| White | 21.9 | 21.6 | 21.9 | 22.3 |

| Black | 22.0 | 21.1 | 23.3 | 22.6 |

| First union cohabitation (%) | ||||

| Hispanic | 56.5 | 54.7 | 70.1 | 78.9 |

| White | 58.0 | 65.5 | 68.0 | 71.0 |

| Black | 65.5 | 71.5 | 83.0 | 81.6 |

Note: Columns reference the period in which unions were formed.

Table 4.

Men’s Median Age at First Marriage, Cohabitation, and Union by Race and Ethnicity

| Variable | 1983–1988 | 1991–1995 | 1998–2002 | 2006–2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first marriage | ||||

| Hispanic | 25.7 | 29.9 | ||

| White | 24.7 | 26.5 | 27.1 | |

| Black | 25.3 | 29.7 | 28.4 | |

| Age at first cohabitation | ||||

| Hispanic | 23.8 | 23.1 | ||

| White | 23.4 | 23.6 | 23.6 | |

| Black | 24.8 | 22.5 | 23.7 | |

| Age at first union | ||||

| Hispanic | 23.7 | 23.6 | ||

| White | 23.2 | 23.7 | 23.7 | |

| Black | 24.5 | 22.5 | 23.8 | |

| First union cohabitation (%) | ||||

| Hispanic | 68.4 | 80.1 | ||

| White | 60.6 | 70.1 | 82.4 | |

| Black | 66.3 | 79.6 | 86.7 |

Note: Columns reference the period in which unions were formed.

The proportion of 35- to 44-year-old women who had ever cohabited similarly increased for all race and ethnic groups, as shown in Figure 2. In the late 2000s, the percentage of 35- to 44-year-old women who had ever cohabited ranged from 58% of Hispanic women to 67% of Black women. The median age at first cohabitation was stable and strikingly similar for each race and ethnic group among both women and men. Among Hispanic women, median age at first cohabitation ranged from 22.3 in the mid-1980s to 20.9 in the late 2000s. The ranges for White and Black women were 22.9 to 21.8 and 22.9 to 22.6, respectively. Men in each race and ethnic group had a slightly higher age at first cohabitation than women. In the late 2000s, men in all three race and ethnic groups experienced a median age at first cohabitation of roughly 23 years. For men and women alike, the gap between Blacks versus Hispanics and Whites was also smaller for median age at first cohabitation than marriage. The median age at first union formation remained about the same over the last 20 years. There was little variation according to race and ethnicity in the timing of first union formation, which ranged among women from 21.3 for Hispanics to 22.0 for Blacks in the 1980s to 21.2 for Hispanics and 22.6 for Blacks in the late 2000s. The age range was also quite narrow among men, hovering around 23 years for age at first union formation over the past 20 years, regardless of race and ethnicity.

Figure 2.

Percentage of Women (Ages 35–44) Who Ever Cohabited, By Race/Ethnicity, Over Time.

Similar proportions of respondents had ever formed a union, and there was almost no change in the proportion of women age 35 and older who had ever formed a union, regardless of race and ethnicity, as depicted in Figure 3. As shown in the bottom row of Tables 3 and 4 the proportion of first unions that were cohabitations rose among all three racial and ethnic groups, with the greatest increases among Hispanic women, White men, and Black men. For Hispanic women, the proportion climbed from 56.5% to 78.9%. The pattern for White women was similar, with the proportion rising from 58.0% to 71.0%. Among Black women, the proportion increased from 65.5% to 81.6%. Among men, the proportions of first unions that were cohabitations rose from 68.4% to 80.1% among Hispanics over the past decade or so. Since the mid-1980s, the proportions grew from 60.6% to 82.4% among Whites and 66.3% to 86.7% among Blacks. Overall, the racial and ethnic variation was more modest than we had anticipated. Patterns of change in the timing of cohabitation and union formation, as well as the trend in the proportion of first unions that were cohabitations, were largely comparable across racial and ethnic groups.

Figure 3.

Percentage of Women (Ages 35–44) Who Ever Formed A Union, By Race/Ethnicity, Over Time.

Figures 4 and 5 show the proportions of women by age group who ever married or cohabited, and Tables 5 and 6 presents the median ages at first marriage, cohabitation, and union for the four education groups (less than high school, high school, some college, and college graduate). Data in Figure 4 indicated that college-educated respondents experienced almost no change in the proportion who ever married, whereas declines occurred for every other education group. Findings for women are presented in the Table 5, and Table 6 contains findings for men. The median age at first marriage increased for all education groups, but the greatest change occurred among the least educated respondents, which was consistent with our expectations. In the 1980s, there was nearly a 6-year age gap in the median age at first marriage for the most and least educated women, and this gap narrowed to about a 1-year difference in the late 2000s. The median age at first marriage was 25.7 for women with less than a high school degree versus 26.7 for women with a college degree in the late 2000s. A similar pattern was observed among men, with a narrowing of the education gap in the median age at first marriage from about 5 to roughly 2 years. In the late 2000s, the median age at first marriage for men was 25.9 for those with less than a high school degree and 28.4 for those with a college degree.

Figure 4.

Percentage of Women (Ages 35–44) Who Ever Married, By Educational Attainment, Over Time.

Note: H.S. = high school; S. = some.

Figure 5.

Percentage of Women (Ages 35–44) Who Ever Cohabited, By Educational Attainment, Over Time.

Note: H.S. = high school; S. = some.

Table 5.

Women’s Median Age at First Marriage, Cohabitation, and Union by Educational Attainment

| Variable | 1984 –1988 | 1991–1995 | 1998–2002 | 2006–2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age first marriage | ||||

| <High school | 19.9 | 21.1 | 22.7 | 25.7 |

| High school/GED | 22.0 | 22.4 | 23.8 | 25.2 |

| Some college | 22.8 | 23.3 | 24.4 | 24.6 |

| Bachelor’s degree+ | 25.8 | 26.2 | 26.8 | 26.7 |

| Age at first cohabitation | ||||

| < High school | 19.1 | 18.6 | 18.9 | 18.8 |

| High school/GED | 22.2 | 21.0 | 21.7 | 19.9 |

| Some college | 22.5 | 22.3 | 21.2 | 21.7 |

| Bachelor’s degree+ | 26.4 | 24.9 | 25.0 | 24.7 |

| Age at first union | ||||

| < High school | 18.4 | 18.3 | 18.9 | 18.7 |

| High school/GED | 20.6 | 20.4 | 20.4 | 19.8 |

| Some college | 21.8 | 21.6 | 21.1 | 21.6 |

| Bachelor’s degree+ | 24.9 | 25.0 | 24.8 | 24.9 |

| First union cohabitation (%) | ||||

| < High school | 82.3 | 73.0 | 85.9 | 89.5 |

| High school/GED | 56.3 | 70.5 | 77.7 | 88.8 |

| Some college | 54.2 | 62.3 | 71.6 | 68.0 |

| Bachelor’s degree+ | 55.1 | 55.1 | 53.3 | 56.2 |

Note: Columns reference the period in which unions were formed.

Table 6.

Men’s Median Age at First Marriage, Cohabitation, and Union by Educational Attainment

| Variable | 1983–1988 | 1991–1995 | 1998–2002 | 2006–2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first marriage | ||||

| < High school | 22.2 | 24.5 | 25.9 | |

| High school/GED | 23.4 | 26.5 | 27.4 | |

| Some college | 24.5 | 25.7 | 27.0 | |

| Bachelor’s degree+ | 27.1 | 28.7 | 28.4 | |

| Age at first cohabitation | ||||

| < High school | 22.4 | 21.2 | 20.8 | |

| High school/GED | 23.1 | 21.9 | 23.1 | |

| Some college | 23.6 | 23.4 | 23.7 | |

| Bachelor’s degree+ | 27.5 | 26.0 | 25.7 | |

| Age first union | ||||

| < High school | 20.6 | 21.3 | 21.2 | |

| High school/GED | 22.6 | 22.8 | 22.9 | |

| Some college | 22.8 | 23.2 | 23.5 | |

| Bachelor’s degree+ | 25.7 | 25.8 | 25.9 | |

| First union cohabitation (%) | ||||

| < High school | 69.5 | 73.1 | 88.8 | |

| High school/GED | 63.1 | 74.0 | 89.0 | |

| Some college | 65.5 | 63.3 | 79.9 | |

| Bachelor’s degree+ | 44.2 | 74.1 | 70.3 |

Note: Columns reference the period in which unions formed.

In terms of cohabitation, Figure 5 shows the greatest increase among women with the lowest education levels and the most modest rise among college graduates, resulting in a widening of the gap in cohabitation experience. The median age at first cohabitation differed according to educational attainment, with the most educated respondents experiencing the latest median ages at first cohabitation, as shown in Tables 5 and 6. The age gap between the most and the least educated individuals remained stable. For example, among women in the mid-1980s the difference between the college educated and those who dropped out of high school was 7 years, and by the late 2000s a 6-year gap existed (see Table 5). Among men, a 5-year age gap according to education persisted over the 20-year time span (see Table 6). The group that changed the most in terms of median age at first cohabitation was women who were high school graduates. Women who earned a high school degree experienced a decline in their age at cohabitation and appeared more like women who had not completed high school during the most recent time period compared with 20 years ago.

Turning to union formation, there was almost no change in the proportion of each education group ever forming of union (see Figure 6). Table 5 shows that in the late 2000s the least educated women were marrying in their mid-20s but started their first coresidential union in their late teens. Twenty years ago, half had married by age 20 and cohabited by age 19. The gap between the age at cohabitation and marriage increased greatly for the least educated respondents, shifting from 1 year to 7 years among women and from less than a year to 5 years among men. The most educated did not change much in the median age at first cohabitation or median age at first marriage, and thus the median age at first union formation was steady, at 24.9, for women with a college degree. In the recent period, among college-educated women the difference between the age at marriage and cohabitation was 2 years (it was less than 1 year in the 1980s). Similarly, Table 6 shows that the median age at first union formation was quite stable among men, fluctuating by less than 1 year regardless of education level.

Figure 6.

Percentage of Women (Ages 35–44) Who Ever Formed A Union, By Educational Attainment, Over Time.

Note: H.S. = high school; S. = some.

A key factor driving the changing patterns of cohabitation and marriage formation by education was the increase in cohabitation as a first union among individuals with modest levels of education. The least educated women shifted from a rate of 82% experiencing cohabitation as their first union in the mid-1980s to nearly 90% in the late 2000s. There was no change among women with a college degree; 55% in the mid-1980s, and 56% in the late 2000s, experienced cohabitation as their first coresidential union. In contrast, among college-educated men there was a sharp increase in the percentage whose first union was cohabitation, from 44% in the mid-1980s to 70% in the late 2000s. Thus, there has been a persistent education gap in regard to people first entering cohabitation rather than marriage. The growth in cohabitation experience was most evident among women with a high school degree, who shifted from about half (56%) cohabiting as their first coresidential union in the mid-1980s to the vast majority, 89%, in the late 2000s. The increase in unions initiated by cohabitation rather than marriage also occurred among working-class men (i.e., with a high school degree).

DISCUSSION

The decline of marriage and rise of cohabitation are two of the most dramatic family changes in the past two decades. With the growing emphasis on the necessity of secure financial prospects for marriage during an era of economic volubility, it is not surprising that the age at marriage continues its steady ascent. Our analyses detailed well-known shifts in the median age at first marriage and documented that delays in marriage entry have occurred for all racial and ethnic as well as education groups. The especially pronounced delay in marriage among American women and men with low educational attainment resulted in a near-convergence in the age at first marriage according to education. College graduates in the early 1980s waited until their mid-20s to marry and continue to do so today. The question remains whether these delays in marriage may eventually lead to foregone marriages among younger cohorts, and we expect this may be a possibility among those who are the most disadvantaged economically.

The trends toward delayed marriage entry do not extend to cohabitation. We found no parallel changes in the median ages at first cohabitation or first union formation. Instead, over a 20-year span women and men were still forming first unions at roughly the same ages. There were few differences in age at cohabitation according to race/ethnicity, but there was large variation by education, with a gap of roughly 6 years between the least and most educated persisting over the past two decades. Men and women with the highest educations were waiting to cohabit and marry, whereas those with the lowest education levels were waiting to marry but not cohabit.

Considerable change in the type of first union occurred, shifting from marriage to cohabitation. Among women, about three quarters (74%) of first unions formed in the late 2000s were cohabiting, in contrast to just over half (58%) 20 years earlier. The greatest increases in cohabitation as a first union appeared among working-class women and men (high school graduates). Among women in the mid-1980s, 56% of first unions were cohabiting unions versus in the late 2000s, when 89% were cohabiting unions. Similarly, age at first union was stable within racial/ethnic group and by education level, and there was a clear education gradient, with age at first union more than 4 years younger for the least educated than the most educated respondents. Thus, it appears that although the education gap in median age at first marriage closed, the education gap in the median age at first union did not. Overall, cohabitation offset changes in the proportion ever marrying and the median age at first marriage.

A key advantage of our study was its attention to the union-formation patterns of women and men. The gender gap in the age at first marriage has persisted, remaining at a 2-year differential. Although we had fewer data points for men than women, the findings appeared consistent and tended to hold within racial and ethnic and education groups. In terms of age at first cohabitation, the gender gap was narrower, about 1 year, than the gender gap in age at first marriage. For the most part, the trends among women according to race/ethnicity and education were mirrored among men, although the rise in the proportion of first unions that were cohabitations was negligible for college-educated women but was large for men regardless of education level.

This study contains a few limitations. First, because of small sample sizes these analyses were restricted to just three racial and ethnic categories. Among men in the earliest time period the sample was too small to include Hispanic men. Also, the sample sizes were not sufficiently large to distinguish nativity status of respondents. Second, the analyses did not account for shifts in the composition of the population in terms of education and race/ethnicity. Also, very young people (e.g., under age 25) in the sample may not have completed their education yet. Third, we focused solely on the median ages at first marriage and cohabitation. The full range of the distribution (e.g., quartiles) of age at union formation may be important to consider in assessing changes in the patterns of union formation over time. We did not statistically test for differences among subgroups of men and women. Another shortcoming is that our indicators of median ages at marriage and cohabitation did not account for the proportions of respondents who married or cohabited by a given age. We provided estimates of the proportions who married and cohabited by age to illustrate changes in the proportions of subgroups experiencing cohabitation and marriage. Our focus was on period change in union formation, but additional work that examines timing of union formation across birth cohorts is warranted. Finally, the NSFG has an upper age limit of 44, so we may have missed a few first marriages and cohabitations among older women and men, but considering the analyses focused on first unions this should not be a serious shortcoming.

This study moves beyond prior work by providing trend data on the median age at first cohabitation. Most prior work has focused on change in marriage in the United States, invoking the shift in the median age at marriage without attention to how cohabitation fits into broader change in union formation. Our findings demonstrate that patterns of cohabitation entry are distinct from those of marriage. Although Americans increasingly delay first-marriage entry, the median age at which they form a first cohabiting union has changed little over the past two decades. The education gradient was striking in that the highly educated respondents, on average, delayed both cohabitation and marriage and the more modestly educated delayed marriage but not cohabitation. The delays in marriage have provided more opportunities for cohabitation in young adulthood, especially among Americans with only modest educational attainment. Given the greater instability of cohabiting unions and the fact that fewer cohabiting unions eventuate in marriage (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2011), we believe these patterns suggest greater opportunities for serial cohabitation (Cohen & Manning, 2010; Lichter, Turner, & Sassler, 2010). As a consequence, young adults today will have more complex relationship biographies that may have implications for their own well-being as well as that of their offspring.

Acknowledgments

The research for this article was supported by the National Center for Family and Marriage Research (5 U01 AE000001-05), which was funded by a cooperative agreement between the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation/U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Bowling Green State University, and the Center for Family and Demographic Research (R24HD050959-09), which is funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this article was presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, New Orleans, LA, 2013.

REFERENCES

- Bumpass LL, Sweet JA. National estimates of cohabitation. Demography. 1989;26:615–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL, Sweet JA, Cherlin AJ. The role of cohabitation in declining rates of marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1991;53:913–927. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. The origins of the ambivalent acceptance of divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:226–229. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. In the season of marriage, a question: Why bother? [Op-Ed] New York Times. 2013 Apr 27; Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/28/opinion/sunday/why-do-people-still-bother-to-marry.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

- Child Trends. Charting parenthood: A statistical portrait of fathers and mothers in America. 2006 Retrieved from http://fatherhood.hhs.gov/charting02/index.htm.

- Cohen J, Manning WD. The relationship context of premarital serial cohabitation. Social Science Research. 2010;39:766–776. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copen CE, Daniels K, Vespa J, Mosher WD. First marriages in the United States: Data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports. 2012;49:1–21. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr049.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood DT, Jencks C. The spread of single-parent families in the United States since 1960. In: Moynihan DP, Smeeding T, Rainwater L, editors. The future of the family. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. pp. 25–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fitch CA, Ruggles S. Historical trends in marriage formation, United States 1850–1990. In: Waite L, Bachrach C, Hindin M, Thomson E, Thornton A, editors. Ties that bind: Perspectives on marriage and cohabitation. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 2000. pp. 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF. If Moynihan had only known: Race, class, and family change in the late 20th century. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2009;621:94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis CM. Expectations and the economic bar to marriage among low income couples. In: Edin K, England P, editors. Unmarried couples with children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2007. pp. 84–103. [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Smock PJ, Bergstrom-Lynch C, Manning WD. He says, she says: Gender and cohabitation. Journal of Family Issues. 2011;32:876–905. doi: 10.1177/0192513X10397601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Bumpass L. Cohabitation and trends in the structure and stability of children’s family lives. Washington, DC: Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America; 2011. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Qian Z. Marriage and family in a multiracial society. In: Farley R, Haaga J, editors. The American people: Census 2000 series. New York: Russell Sage Foundation and Population Reference Bureau; 2004. pp. 169–200. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter D, Turner R, Sassler R. National estimates of the rise in serial cohabitation. Social Science Research. 2010;39:754–765. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD. Trends in cohabitation: Over twenty years of change, 1987–2010. Bowling Green, OH: Family Profile-13-12, National Center for Family & Marriage Research; 2013. Retrieved from http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file130944.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S. Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the Second Demographic Transition. Demography. 2004;41:607–627. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mincieli L, Manlove J, McGarrett M, Moore K, Ryan S. The relationship context of births outside of marriage: The rise of cohabitation. Child Trends Research Brief; 2007. Retrieved from http://www.childtrends.org/files/Child_Trends-2007_05_14_RB_OutsideBirths.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Payne KK. Median age at first marriage, 2010. Bowling Green, OH: Family Profile-10-06, National Center for Family & Marriage Research; 2012. Retrieved from http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file109824.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Payne KK, Gibbs L. First marriage rate in the U.S., 2010. Bowling Green, OH: Family Profile-11-12, National Center for Family & Marriage Research; 2011. Retrieved from http://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file104173.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK. A shortage of marriageable men? A note on the role of cohabitation in Black–White differences in marriage rates. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:973–983. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, Bratter J. Not even if you were the last person on earth! How marital search constraints affect the likelihood of marriage. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25:167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S. The process of entering into cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:491–505. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen R, Landale NS, Daniels K, Cheng Y. Social background differences in early family behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:384–395. [Google Scholar]

- Shryock HS, Siegel JS, Larmon EA. The methods and materials of demography. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Shryock HS, Siegel JS, Larmon EA. The methods and materials of demography. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons T, Dye JL. What has happened to median age at first marriage data? San Francisco: Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association; 2004. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ, Manning WD, Porter M. Everything’s there except the money: How economic factors shape the decision to marry among cohabiting couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:680–696. [Google Scholar]

- South SJ. Historical changes and life course variation in the determinants of premarital childbearing. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:752–763. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Estimated median age at first marriage, by sex: 1890 to the present. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/families/data/marital.html.