Abstract

Adaptor proteins mediate signal transduction from cell surface receptors to downstream signaling pathways. The Grb7 protein family of adaptor proteins is constituted by Grb7, Grb10, and Grb14. This protein family has been shown to be overexpressed in certain cancers and cancer cell lines. Grb7-mediated cell migration has been shown to proceed through a focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/Grb7 pathway, although the specific participants downstream of Grb7 in cell migration signaling have not been fully determined. In this study, we report that Grb7 interacts with Hax-1, a cytoskeletal-associated protein found overexpressed in metastatic tumors and cancer cell lines. Additionally, in yeast 2-hybrid assays, we show that the interaction is specific to the Grb7-RA and -PH domains. We have also demonstrated that full-length Grb7 and Hax-1 interact in mammalian cells and that Grb7 is tyrosine phosphorylated. Isothermal titration calorimetry measurements demonstrate the Grb7-RA-PH domains bind to the Grb7-SH2 domain with micromolar affinity, suggesting full-length Grb7 can exist in a head-to-tail conformational state that could serve a self-regulatory function.

Keywords: adaptor proteins, Grb7, tyrosine kinase, erbB2, HER2, neu, cell migration, Hax-1, calorimetry

Introduction

The cell migration protein Grb7 is composed of an N-terminal Pro-rich region, an RA-like (Ras Associating) domain (Wojcik et al., 1999), a PH (Pleckstrin Homology) domain, a BPS (Between Pleckstrin and Src) domain, and a C-terminal SH2 domain (Figure 1). The RA, PH, and BPS domains are also known as the GM (Grbs and Mig) domain, due to shared homology with the C. elegans protein Mig-10 (Manser et al., 1997). The Grb7 protein is known to homo-dimerize through an interaction mediated primarily through its SH2 domain (Ivancic et al., 2005; Porter et al., 2005; Porter et al., 2007), although recently it has been suggested the Grb7-RA-PH domains may undergo a homo-dimerization reaction to some extent as well (Depetris et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Domain topology of the Grb7 protein. The approximate locations of the Grb7 tyrosine to phenylalanine mutation sites as described in the text are identified by arrows in the primary amino acid sequence.

For many proteins the activity of one domain can affect the availability or activity of other domains. Research from our laboratory (Ivancic et al., 2005; Siamakpour-Reihani et al., 2009) and others (Han and Guan, 1999; Han et al., 2000; Tsai et al., 2007) suggests that two such domains of the Grb7 protein (the Grb7-RA and -PH domains) may work together or be controlled together to confer functionality. Han and Guan (1999) and Han et al. (2000) showed that some portion of the Grb7 central region (containing the RA and PH domains) controls Grb7-mediated migration of cancer cells. Studies focused on the functional role of the RA and PH domains in this protein are an important step in under-standing the mechanisms that drive cancer progression, with the desired goal of exploiting vulnerabilities for cancer therapies.

It has been shown that Grb7-mediated cell migration takes place through an interaction with focal adhesion kinase (FAK) via the Grb7-SH2 domain (Han and Guan, 1999; Han et al., 2000; Chu et al., 2009). Furthermore, FAK phosphorylates Grb7 at tyrosine residues after initial Grb7 binding (Han and Guan, 1999; Chu et al., 2009). Grb7 is also phosphorylated on serine and threonine residues; however, growth factor stimulation does not result in differential Ser/Thr phosphorylation patterns (Stein et al., 1994; Fiddes et al., 1998). Overexpression of Grb7 can lead to increased cell migration and development of metastases, as seen in the overexpression of Grb7 in lymph node metastases (Tanaka et al., 1998). Little is known regarding the specific participants downstream of the Grb7 protein resulting in migration signaling.

In a prior study, we demonstrated that the Grb7 protein binds to FHL2, another signaling protein associated with transcription regulation and cytoskeletal rearrangement (Siamakpour-Reihani et al., 2009). We also proposed an autoinhibited conformational form of Grb7 based upon a binding interaction between the Grb7-RA-PH domains and the Grb7 C-terminus containing the SH2 domain, supported by observed nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift perturbations. Herein, we describe a Grb7 protein interaction with Hax-1 (Hs-1 Associated protein X-1) and provide quantitative binding affinity data for an intramolecular interaction between the Grb7-RA-PH domains and the Grb7-SH2 domain.

Hax-1 is a multi-functional protein serving roles in cell migration signaling, apoptosis, and possibly mRNA regulation or stability (for a recent review see Fadeel and Grzybowska, 2009). In cell migration signaling, Hax-1 has been observed in complex with other cytoskeletal-associated proteins: cortactin, Gα13, and Rac (Gallagher et al., 2000; Radhika et al., 2004). Hax-1 has also been shown to bind to the β6 subunit of the integrin αvβ6 (Ramsay et al., 2007). Reduction of endogenous Hax-1 through small interfering RNA has suppressed both Gα13 and αvβ6 mediated cell migration (Radhika et al., 2004; Ramsay et al., 2007).

The goal of the current study was to identify interaction partners of Grb7 potentially involved in FAK/Grb7-mediated cell migration, while clarifying the role of the Grb7-RA and -PH domains in this protein. The phosphorylation state of Grb7 necessary for (or during) binding interactions was explored, and finally, a Grb7 autoinhibitory mechanism based upon these results is proposed.

Materials and Methods

Yeast two-hybrid screening and interaction assays

A Yeast two-hybrid assay (Y2H) was performed using CLONTECH's Matchmaker GAL4 Two Hybrid System 3 according to the manufacturer's instruction (Clontech) to screen for proteins involved in Grb7 signaling. The Grb7-RA-PH, Grb7-RA, or Grb7-PH domains were amplified from a pCMV-Grb7 full-length template by PCR. The “bait” Grb7-RA-PH, Grb7-RA, or Grb7-PH was directionally subcloned into the pGBKT7 vector (DNA-BD/Bait). Initially, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain AH109 was transformed with a pGBKT7 vector carrying the Grb7-RA-PH domain according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech). The Clontech pretransformed Human HeLa Matchmaker cDNA Library in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain Y187 containing the pGADT7-Rec vector (DNA-AD/Prey) was used for the screen (Clontech). The results of the mating of Y187/pGADT7-Rec with the AH109/pGBKT7-Grb7-RA-PH were subjected to additional selection screening using appropriate media (medium stringency quadruple dropout media Synthetic Minimal Medium (SD)/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp, and high stringency SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp/X-α-Gal media) to verify the interaction between the BD and AD. The MEL1 gene encodes the secreted enzyme α-galactosidase that hydrolyzes colorless X-α-Gal into a blue end product; thus, positive two-hybrid interaction colonies are blue. Plasmids from positive clones were extracted using Zymoprep™ II spin columns (Zymo Research Corporation). The plasmids were transformed into E. coli Top 10 cells (Invitrogen), and grown on LB/ampicillin plates. Colonies were selected for plasmid extraction, followed by sequencing. The sequencing results were used for homology searching using BlastX (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/). Protein candidates with links to cell migration and proliferation, and/or proteins that have been linked to cancer development and progression were given highest priority for analysis. To determine which Grb7-RA-PH domain(s) were necessary for the protein–protein binding in the Y2H assay, the isolated pGADT7-Rec plasmids carrying high-priority sequences were co-transformed with pGBKT7-Grb7-RA or pGBKT7-Grb7-PH into AH109 competent cells using the Lithium acetate method according to the manufacturer's instruction (Clontech). The cells were initially plated on double dropout media SD/-Leu/-Trp. AH109 cells growing on SD/-Leu/-Trp confirmed the presence of both pGBKT7 and pGADT7-Rec plasmids. Colonies grown on the SD/-Leu/-Trp were subcloned using quadruple dropout media (SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp/X-a-Gal). Examples of the yeast 2-hybrid interaction between the Grb7-RA-PH construct and Hax-1 are available in the Supplementary Data section (Figures 1-A, 1-B).

Mammalian expression vector constructs for Grb7 and Hax-1

The pCMV-HA and pCMV-cMyc mammalian expression vectors were used to subclone the DNA sequences of the full-length Grb7 and Hax-1 proteins obtained through the initial Y2H assay. These expression vectors express a fusion of proteins of interest with either the cMyc, or hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag (Clontech). The amplified full-length Grb7 gene was directionally subcloned into pCMV-cMyc using the SfiI and SalI restriction sites (Siamakpour-Reihani et al., 2009). The full-length human Hax-1 (variant 1) gene was subcloned into the pCMV-HA vector using the SalI and NotI restriction sites from a pDNR-LIB-HAX1 template obtained from Open Biosystems (forward primer: 5′ -AAATCTTGTCGACCCGTCTGCGAATGGACCAC-3′; reverse primer: 5′-AAATCTT GCGGCCGCTTAGCATAAATAAAGGTTTTATTGGTC-3′). Positive control vectors were also constructed by subcloning the P53 insert in the pCMV-cMyc and the Large T antigen sequence in the pCMV-HA vector (data not shown).

Construction of Grb7-RA-PH domain protein expression vector for calorimetry analysis

The ligation-independent cloning method (Aslanidis and de Jong, 1990), using the pET46 EK/LIC vector according to the manufacturer's protocol (Novagen), was used to subclone the Grb7-RA-PH domains (residues 103-341 of the hGrb7 protein), as described in Siamakpour-Reihani et al. (2009). The Grb7-SH2 domain expression vector has been described previously (Brescia et al., 2002).

Antibody immobilization

The Grb7 (N20) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was immobilized using the ProFound™ Co-Immunoprecipitation method according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce Biotechnology). Samples of the immobilized Ab-bead slurry were boiled at 95°C for 5 min and separated via SDS-PAGE with Coomassie or silver staining to confirm the presence of the immobilized antibody.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis of selected Tyr residues was performed by polymerase chain reaction according to the manufacturer's guidelines, using the GeneTailor Site-Directed Mutagenesis System (Invitrogen). Primer sequences are reported in the supplemental data section of Siamakpour-Reihani et al. (2009). Mutations were verified by DNA sequencing. All Grb7 mutants were expressed as full-length (FL)-Grb7 proteins: FL–Grb7(Y262F), FL–Grb7(Y263F), FL–Grb7(Y262F/Y263F), FL–Grb7(Y287F), FL–Grb7(Y483F), FL–Grb7(Y495F), and FL–Grb7(Y483F/Y495F). Tyrosine residues were selected for mutation based upon their prediction as possible phosphorylation sites using the software NetPhos 2.0 (www.cbs.dtu.dk/zservices/NetPhos/).

Cell culture and transfections

HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated constructs using the transfection reagent Lipofectamine™ LTX (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained in Eagle's minimum essential medium (EMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% l-glutamine, 1% sodium bicarbonate, 0.5% sodium Pyruvate, and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic. Cells were co-transfected with pCMV-HA-HAX-1 and pCMV-cMyc-Grb7 vectors (wild type or mutants as described previously), and were processed for pull-down assays or staining 48 h post-transfection.

Co-immunoprecipitation and western blotting

After incubation, transfected HeLa cells were trypsinized and washed with PBS. Cells were lysed using the mammalian protein extraction reagent (M-PER) according to the manufacturer's recommendation (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.), and cellular debris removed by centrifugation at 15 000 × g. Lysates were incubated with immobilized Grb7 antibody beads (4°C) overnight, washed, eluted, and loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane, and western blotting was carried out using anti-HAX-1 (mouse anti-HAX-1) or anti-Grb7 (H70) as the primary antibody, with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG as the secondary antibody. The SuperSignal West Femto substrate was used for visualization (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.) for FHL2 and Grb7 primary antibody blots. The signal for the PY20 (phosphotyrosine) primary antibody blots was so intense a more insensitive (Amersham ECL–Enhanced ChemiLuminescence, GE Biosciences) visualization reagent was used to decrease the signal to levels that avoided overly-intense (i.e., white) bands (for an example of the pY signal using the Femto substrate see the Supplementary Data section, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Co-immunoprecipitation results for co-transfected HeLa cells with the vectors full-length Hax-1/HA-pCMV and full-length Grb7/cMyc-pCMV. The same membrane is stripped and probed with antibodies a total of three times (A–C). Lane 1: co-transfected HeLa cell lysate. Lane 2: 40 μl native HeLa cell lysate, pull down with beads, no Ab. Lane 3: 40 μl native HeLa cell lysate, pull down with Grb7-Ab-immobilized beads (N-20). Lane 4: Pull down of co-transfected HeLa cell lysate with Grb7-Ab-immobilized beads, 10 μl. Lane 5: Pull down of co-transfected HeLa cell lysate with Grb7-Ab-immobilized beads, 40 μl. Panel A: all lanes probed with Hax-1-Ab. Panel B: all lanes probed with Grb7-Ab (H-70). Panel C: all lanes probed with phospho-Tyr-Ab (PY20).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology: GRB7 (H-70): rabbit polyclonal, GRB7 (N-20): rabbit polyclonal, p-Tyr (PY20) mouse monoclonal, p-Tyr (PY350) rabbit polyclonal. The HA-Tag rabbit-Polyclonal and the cMyc mouse monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Clontech. The HAX-1 mouse monoclonal antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences. The Alexa Fluor® 488 goat anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor® 546 goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen. The ImmunoPure® Peroxidase Conjugated Goat anti-rabbit, and ImmunoPure® Peroxidase Conjugated Goat anti-mouse antibodies were obtained from Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.

Grb7 protein domain(s): sample preparation and isothermal titration calorimetry

Sample preparation

Expression and purification of the human Grb7-SH2 domain has been described in detail previously (Brescia et al., 2002). A pET expression plasmid containing the hGrb7-RA-PH gene insert was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(Rosetta) cells and expressed at 37°C. The RA-PH domains, consisting of residues 103-341 of the hGrb7 protein, were expressed as a hexa-histadine fusion protein and purified by affinity chromatography utilizing NiNTA resin (Invitrogen). Typical yields of pure hGrb7-RA-PH domain were 2–4 mg per liter of culture, and for pure hGrb7-SH2 domain 4–6 mg per liter of culture. Sample conditions for the calorimetry studies were typically: 0.130 mM Grb7-SH2 domain (reported as a dimer concentration), 0.013 mM Grb7-RA-PH domain, 20 mM K2PO4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM TCEP, and pH 7.4.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Titrations were performed using a VP-ITC ultra sensitive isothermal titration calorimeter (Microcal Corp. Northampton, MA) (Wiseman et al., 1989). The Grb7-RA-PH domain was dialyzed with three exchanges of buffer (1/1000 v/v). To reduce errors arising from heats of dilution due to buffer differences between samples in the syringe and the reaction vessel, the Grb7-SH2 domain “ligand”was dialyzed concurrently with the Grb7-RA-PH sample. Both peptide and protein concentrations were determined using measured A280 values prior to loading into the syringe and reaction vessel. For each titration, 10 μl of the Grb7-SH2 domain (130 μM) was delivered into the Grb7-RA-PH protein sample (13 μM, 1.5 ml chamber) over a 20 s duration with an adequate interval (250 s) allowing complete equilibration. Binding curves involved the addition of 60 injections that enabled approximately 50% saturation to occur by the thirtieth injection. The heats of dilution, obtained by titrating the identical Grb7-SH2 domain solution into the reaction cell containing only the sample buffer, were subtracted prior to analysis. Data were recorded at a baseline of 20 μcal/s and at a high gain mode thus providing the fastest re-equilibration between injections. The syringe mixing speed was 300 rpm in order to ensure sufficient mixing while keeping baseline noise at a minimum. The data was collected automatically, and analyzed with a one-site model via the Origin software provided from Microcal (ITC Origin, V7.0, Microcal, Northampton, MA). Origin utilizes a nonlinear least-squares algorithm (minimization of χ2), the concentration of the titrant and sample, and an equilibrium equation to provide best fit values of the binding curve thus providing stiochiometry (n), change in enthalpy (ΔH), and binding constant K (Zhang et al., 2000).

Results

Grb7 interacts with Hax-1 via its RA and PH domains

A yeast 2-hybrid assay (described in Materials and Methods) was performed using a Grb7-RA-PH two-domain bait construct screened against a HeLa cell cDNA library, resulting in a protein potentially involved in Grb7-mediated cellular signaling: Hax-1. Specifically, seven essentially full-length Hax-1 (human variant 1) clones were identified as binding positively to the Grb7-RA-PH region (out of thirty-five positive clones, the remaining positive clones will be reported elsewhere). Yeast 2-hybrid assays performed using only the Grb7-RA domain or the Grb7-PH domain as bait indicated Grb7-RA or Grb7-PH domains alone are not sufficient for binding to Hax-1 (data not shown).

HAX-1 interacts with full-length Grb7 in mammalian cells

HeLa cells were co-transfected with vectors expressing Hax-1 and full-length Grb7 (FL-Grb7), and tested for interaction between the two proteins by co-immunoprecipitation assay as described in the Materials and Methods. Co-transfected HeLa cell lysates were exposed to immobilized Grb7 antibody, washed, eluted, and separated via SDS-PAGE. Figure 2 presents the immunoprecipitation results for HeLa cells co-transfected with the Hax-1 and Grb7 expression vectors. In Figure 2, lane 1 shows co-transfected HeLa cell lysate; lane 2 is 40 μl native HeLa cell lysate, pull down with beads, no Ab; lane 3 is 40 μl native HeLa cell lysate, pull down with Grb7-Ab-immobilized beads; lane 4 is pull down of 10 μl co-transfected HeLa cell lysate with Grb7-Ab-immobilized beads; and lane 5 is pull down of 40 μl co-transfected HeLa cell lysate with Grb7-Ab-immobilized beads. All lanes were sequentially probed with Hax-1 antibody, Grb7 antibody, and phosphotyrosine antibody (Figure 2, Panels A–C). The full-length Grb7 protein migrates at an apparent molecular weight of approximately 70–72 kD in HeLa cells, as previously shown (Siamakpour-Reihani et al., 2009). The apparent molecular weight of Hax-1 is approximately 50–52 kD, and is likely post-translationally modified, as noted for Hax-1 expressed in HeLa cells (Al-Maghrebi et al., 2002). These results verify that FL-Grb7 protein co-immunoprecipitates with Hax-1 protein in a mammalian cell environment (Figure 2, lanes 4 and 5). A faint band observed at the same position as Hax-1 in Panel A, lane 3, could represent pull-down of endogenously expressed Hax-1. However, a corresponding signal is not observed for Grb7, possibly reflecting differing sensitivities between the protein-specific primary antibodies. In Figure 2 the large difference in intensities in the Grb7 signal for the 10 μl versus 40 μl pull-down is not directly obvious, due to the overly intense Grb7 signal (white). In the Supplementary Data section (Figure 3), an example of the large intensity difference between the 10ml versus 40 μl samples is presented.

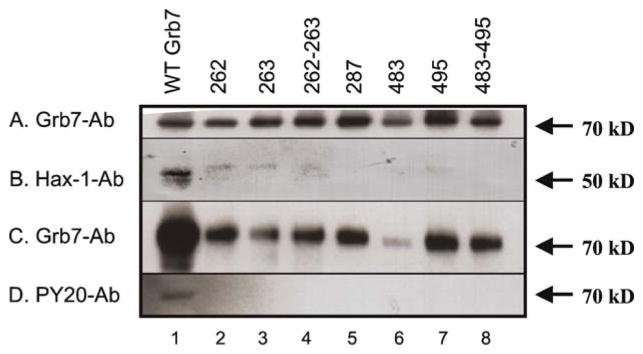

Figure 3.

The effect of the loss of possible tyrosine phosphorylation sites in Grb7 was measured in terms of the ability of FL-Grb7 to interact with Hax-1. Lanes 1–8 demonstrate the ability of FL-Grb7 and FL-Grb7 mutants to interact with Hax-1 by immunoprecipitation assay as described in the materials and methods section. Panel A: transfected cell lysate loading control, probed with Grb7 Ab (H-70). Panel B: all lanes probed with Hax-1 Ab. Panel C: all lanes probed with Grb7 Ab (H-70). Panel D: all lanes probed with phospho-Tyr Ab (PY20). Lane 1: wild type FL-Grb7, Lane 2: FL-Grb7(Y262F), Lane 3: FL-Grb7(Y263F), Lane 4: FL-Grb7(Y262F/Y263F), Lane 5: FL-Grb7(Y287F), Lane 6: FL-Grb7(Y483F), Lane 7: FL-Grb7(Y495F), Lane 8: FL-Grb7(Y483F/Y495F).

Full-length Grb7 is phosphorylated on Tyrosine residues

As described above, the FL-Grb7/Hax-1 co-immunoprecipitation assay results were also probed with a phosphotyrosine antibody (Figure 2, Panel C). The bands verified as Grb7 in lanes 4 and 5 in Panel B (molecular weight 70–72 kD) react positively with the phosphotyrosine antibody (lanes 4 and 5, Panel C), while there is no phosphotyrosine antibody signal observed at the molecular weight corresponding to Hax-1 (approximately 50–52 kD, as determined by reaction with Hax-1 antibody). This result demonstrates that the FL-Grb7 protein is phosphorylated on one or more tyrosine residues, and that Hax-1 is not tyrosine phosphorylated. The possibility that some molecule with the same molecular weight as Grb7 may be co-precipitating with Grb7, and is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues, is not completely ruled out.

The phosphorylation state of the Grb7 PH and SH2 domains may affect Grb7 function

Five predicted (NetPhos 2.0) Grb7 tyrosine residue phosphorylation sites were mutated to phenylalanine residues. Three of the phosphorylation sites are located in the PH domain, while the remaining two are located in the SH2 domain (see Figure 1). The resulting single and double Tyr Phe mutants were named according to the location of the mutations: FL-Grb7(Y262F), FL-Grb7(Y263F), FL-Grb7(Y262F/Y263F), FL-Grb7(Y287F), FL-Grb7(Y483F), FL-Grb7(Y495F), and FL-Grb7(Y483F/495F). Numbering of the Grb7 protein residues is in accordance with Tsai et al. (2007).

All of the Grb7 tyrosine mutations resulted in either complete negation, or a large decrease, in Hax-1 binding to Grb7, as can be seen in lanes 2–8 of Figure 3. In lane 1 of Figure 3, wild-type FL-Grb7 co-immunoprecipitates with Hax-1 readily (Panel B). However, co-immunoprecipitation results for the Grb7 Tyr→Phe mutants show a greatly diminished Hax-1 signal in comparison. Panel A provides transfected cell lysate loading controls for wild-type FL-Grb7, and each of the studied mutants, based upon the intensity of the Grb7 Ab signal. The loading controls show that approximately the same amount of Grb7 protein is contained in each cell lysate prior to exposure to Grb7-antibody immobilized beads. Panel C demonstrates, by probing with Grb7 Ab after co-immunoprecipitation, that all the Grb7 protein mutants are binding to the Grb7-antibody immobilized beads (it is noted that the FL-Grb7(Y483F) mutant signal is reduced compared to others). The Grb7 antibody (H70, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) is produced in a mammalian cell environment, and presumably was raised against Grb7 antigen that is likely phosphorylated on tyrosine residues. Therefore, the somewhat lower Grb7-Ab signal observed for all the mutants could reflect decreased binding affinity for the changed Grb7 antigen (i.e., not the same phosphorylation state). Based upon the intensity of the Hax-1 Ab signal in lanes 2–8 of Panel B, the ability of the Grb7 mutants to immunoprecipitate Hax-1 decreases in the order: Grb7(Y262F), Grb7(Y263F), Grb7(Y262F/263F), Grb7(Y495F), and Grb7(Y287F): Grb7(Y483F):Grb7(Y483F/495F). The Grb7(Y287F), Grb7(Y483F), and Grb7(Y483F/495F) mutants immunoprecipitate no detectable Hax-1 protein. The small amount of Hax-1 protein that does apparently co-immunoprecipitate with a few of the Grb7 mutants, is of a slightly larger apparent molecular weight than the main overexpressed Hax-1 band. An example of the several forms of Hax-1 protein present in HeLa cells is shown in the supplemental data section, where it can be seen the slight Hax-1 band in lanes 2–4 and 7, in Figure 3, is also present in HeLa cell lysates (Supplemental data, Figure 4), when the signal is allowed to develop for longer time periods.

Figure 4.

(Top) Exothermic heats of reaction (μcal/s) measured for 60 injections of the Grb7-SH2 domain into a Grb7-RA-PH domain sample. (Bottom) The solid line is the best fit to the data for a single binding site model using a nonlinear least squares fit to solve for n (number of binding sites), Kb (equilibrium binding constant), and ΔH (change in enthalpy of reaction), and reported in Table 1. Note the fit to the experimental data assumes an effective concentration of the Grb7-SH2 domain as a dimer, i.e., n is 1:1, where 1 binding site (for the RA-PH) exists on a dimer of SH2 domains. Under the experimental conditions described, essentially 100% of the Grb7-SH2 domain exists in a dimerized form (Porter et al., 2007).

The same co-immunoprecipitation results in Figure 3 were probed with phosphotyrosine antibody, as in Figure 2, to discover the tyrosine phosphorylation state of wild-type FL-Grb7 and the Grb7(Tyr→Phe) mutants. As can be seen in Panel D, only the wild-type FL-Grb7 reacts with the phosphotyrosine Ab, signifying all of the Grb7(Tyr→Phe) mutants lack phosphorylation on tyrosine residues. This result implies Grb7 must be phosphorylated on tyrosines to bind with Hax-1, but does not rule out the possibility that the mutation itself, i.e., Tyr Phe, prevents Grb7 interaction with Hax-1.

The Grb7-SH2 domain binds with micromolar affinity to the Grb7-RA-PH domains

The binding of the Grb7-SH2 domain to the Grb7-RA-PH domains was studied by isothermal titration calorimetry. Figure 4 (top) shows the heat of reaction for 30 titrations of Grb7-SH2 domain into a solution of the Grb7-RA-PH domain. The binding reaction is exothermic, and the integrated heats of reaction for the data in Figure 4 (top) are shown as a binding curve in Figure 4 (bottom). A nonlinear least squares fit of the binding curve provides values for the stoichiometry of binding (n, ligand:protein), equilibrium binding constant (Kb), and change in enthalpy (ΔH). A thermodynamic description of binding is obtained from these parameters including the free energy of binding, ΔG, and change in entropy of reaction, ΔS.

where R is the gas constant and T is the temperature in Kelvin. The solid line shown in Figure 4 (bottom) is the best fit for the reaction performed at 25°C, and a summary of the binding parameters is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Thermodynamic parametersa for the binding of the Grb7-SH2 domain to the Grb7-RA-PH domains at 25°C.

| Kd (μM) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | −TΔS (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.80 ± 0.76 | −8.02 ± 0.16 | −18.0 ± 0.6 | +10.0 ± 0.8 |

The stoichiometry, n, was also fit and varied from a value of 0.2–1.9 (specifically n = 0.2; 0.7; 1.9, and assuming the effective SH2 domain concentration as a dimer). The potential reason for this variation is discussed in the text. The statistics quoted are the average and standard deviations for three different experiments.

The Grb7-SH2 domain binds to the Grb7-RA-PH domain (Kd = 2.80 ± 0.76 μM) with approximately the same order of binding affinity as peptides representative of the Grb7-SH2 domain binding to receptor tyrosine kinases such as erbB2 (Kd = 2.28 μM, Ivancic et al., 2005). Binding between the Grb7-SH2 domain and the Grb7-RA-PH domain is enthalpically favored (ΔH = −18.0 ± 0.57 kcal/mol) and entropically disfavored (−TΔS = +10.0 ± 0.73 kcal/mol). The Grb7-SH2 domain is essentially dimerized at the concentrations utilized in this study. n, the stoichiometry of binding, varied from 0.15 to 1.9 between the three isotherms. This is likely due to inaccuracy in the actual Grb7-RA-PH domain concentration. The Grb7-RA-PH domain solutions undergo slow precipitation over time.

Discussion

This study has shown that the cell migration proteins Grb7 and Hax-1 interact in a mammalian cell environment, and that full-length Grb7 is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues when this interaction occurs (to any appreciable extent). Further, through yeast 2-hybrid analysis, we have shown the interaction with Hax-1 requires both the RA and PH domains of Grb7. We have also shown the Grb7 protein is capable of an intramolecular association that could act as a form of self-regulation, thus controlling availability for binding with signaling partners such as Hax-1.

Hax-1 (Hs-1 Associated protein X-1) is a 35 kD intracellular protein expressed ubiquitously throughout tissue types. It was initially described as localized to mitochondrial membranes, the endoplasmic reticulum, and the nuclear envelope; but since has also been observed in the cytoplasm (Suzuki et al., 1997; Kawaguchi et al., 2000). Empirically, Hax-1 has ties to both cancer and cell migration signaling. It is overexpressed in metastatic tumors and tumor cell lines (Velculescu et al., 1995; Jiang et al., 2003; Mirmohammadsadegh et al., 2003). Hax-1 expression increases in a hypoxic tumor environment suggesting it may contribute to the cell-matrix contact changes associated with tumor progression (Jiang et al., 2003). The presence of a quaternary complex consisting of Ga13, Hax-1, Rac, and cortactin indicates a potential role for Hax-1 in linking Gα13 to the cytoskeletal components involved in cell movement (Radhika et al., 2004). Hax-1 has been shown to bind to an integrin subtype involved in endocytosis (Ramsay et al., 2007).

Hax-1 also protects cells from apoptosis (Kawaguchi et al., 2000; Akira and Hemmi, 2003; Lysa et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009; Vafiadaki et al., 2009) and is a member of the Bcl-2 protein family. Hax-1 is a substrate of caspase-3, and inhibits the apoptotic process by inhibiting caspase-3 activity (Lee et al., 2008).

We recently presented a model in which dimerized Grb7 is autoinhibited through an interaction between the N-terminal domains of the protein and the C-terminal SH2 domain region, based upon evidence from prior yeast 2-hybrid studies (Leavey et al., 1998), and our own results (Siamakpour-Reihani et al., 2009). In this model, we postulated phosphorylation on tyrosine residues could potentially relieve a Grb7 autoinhibited conformation. Recently Chu et al. (2009) showed that three of the residues mutated in this study, Y262, Y263, and Y495 (Y259, Y260, and Y492, Chu et al. (2009) numbering), when mutated to phenylalanines and overexpressed (along with FAK) in CHO cells, appreciably decreases cell motility.

In our prior study, Siamakpour-Reihani et al. (2009), we showed that the Grb7-RA-PH domains and the Grb7-SH2 domain may be involved in an intramolecular association, based upon observed nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift perturbations. We have now provided quantitative binding affinity measurements for the Grb7-SH2 and Grb7-RA-PH domains interaction, thus supporting the hypothesis that the Grb7 molecule can indeed interact in a head-to-tail fashion. The binding affinity of the interaction is on the same order as binding of the SH2 domain to peptides representative of phosphorylated RTK targets (Ivancic et al., 2005), and suggests a regulation mechanism involving interplay between potential Grb7 binding partners. This tableau accurately describes the role of scaffolding, or adaptor, proteins in intracellular signaling.

The binding between the Grb7 SH2 and RA-PH domains is enthalpically favored while being entropically disfavored. This disfavored entropy may be a function of the artificial nature of our system. In the calorimetry measurements, the SH2 and RA-PH domains are physically detached from each other. In the intact Grb7 protein they would, of course, be part of the same molecule. Therefore, the entropic contribution to the binding affinity between the SH2 and RA-PH domains in the full-length Grb7 protein could be quite different than the results presented here.

Previous yeast 2-hybrid screens employing full-length Grb7 yielded no identifiable binding partners (Leavey et al., 1998). Therefore our yeast 2-hybrid studies used the Grb7-RA-PH domains alone as bait, with the thought that the full-length Grb7 molecule prevents access to these domains in the non-mammalian environment. Isolating the Hax-1 protein as a Grb7 interacting partner lends support to this hypothesis. The Grb7/Hax-1 interaction was verified using FL-Grb7 in a mammalian cell environment, suggesting some post-translational modification needed for Grb7 activation was not present in the yeast environment.

One would expect mutation of potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites in Grb7 could affect Grb7's ability to bind Hax-1, if phosphorylation is a prerequisite for Grb7-RA-PH domain signaling through proteins such as Hax-1. Indeed, we have shown this to be the case. However, the differential effect of mutating various tyrosine residues to phenylalanine is not highly pronounced. All of the mutations result in obviously decreased ability of Grb7 to bind Hax-1, based upon comparison of the co-immunoprecipitation signal for the Grb7 mutants versus the wild-type Grb7 (Panel B, Figure 3). Based upon the strength of the Hax-1 antibody signals in Figure 3, one could make the argument that mutation of residues Y287, Y483, and Y483/Y495 is particularly detrimental. Mutagenesis raises the possibility that the protein produced could be miss-folded or denatured. For the Y483F and 495F mutations, at least, we can demonstrate the Grb7-SH2 domain is likely natively folded, by circular dichroism measurements (Supplemental Data section, Figure 5).

As we have shown, all of the mutated PH- and SH2-domain tyrosines are important for Grb7 phosphorylation (in HeLa cells), and they may be required in entirety for proper recognition of Grb7 as a tyrosine kinase substrate. A Grb7 head-to-tail association could bring all of the target tyrosines into close proximity, and may constitute a kinase substrate recognition site. Essentially an identical result was observed for the same Y → F Grb7 mutants binding to FHL2 in HeLa cells (Siamakpour-Reihani et al., 2009). Though circumstantial, these dual results with different Grb7 binding partners suggests that Grb7 tyrosine phosphorylation occurs prior to binding to either FHL2 or Hax-1, and again points to tyrosine phosphorylated Grb7 as the “active”signaling form.

Conclusions

The adaptor protein Grb7 interacts with Hax-1 in a mammalian cell environment, and Grb7 is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues in cell lysate pull-downs of Hax-1. The presence of the RA and PH domains of Grb7 alone is sufficient for binding between Hax-1 and Grb7. Mutation of any of the five predicted tyrosine phosphorylation sites of Grb7 results in loss of binding to Hax-1 and an apparent global loss of tyrosine phosphorylation on Grb7. This loss of tyrosine phosphorylation on Grb7 could perhaps be explained by a Grb7(Y → F) mutant substrate deficiency for tyrosine kinases. Isothermal titration calorimetry measurements demonstrate the Grb7-RA-PH and Grb7-SH2 domains bind with micromolar affinity, thus supporting a model for Grb7 regulation (in this case inactivation) via an intramolecular Grb7 domain association.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The full-length Grb7 cDNA was a gift from Prof. Roger Daly, Garven Institute, Sydney, AU. We thank Jeongwon Jun for DNA sequencing support, Hyun-Jung Kim and Lori Jo Wilmeth for tissue culture support, and Olivia George for cell microscopy. We acknowledge the INBRE-supported Cell and Organismal Core Facility. The following sources of financial support are gratefully acknowledged: National Institutes of Health Grant Numbers: 2 S06 GM008136, 5U56 CA096286, and RR 016480.

Abbreviations

- erbB2

Erythroblastic leukemia viral (v-erb-b) oncogene homo-log 2

- a.k.a

HER2

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- Grb7,10,14

Growth factor receptor bound 7, 10 and 14 protein respectively

- Hax-1

Human HS-1 Associated protein-1

- ITC

Isothermal titration calorimetry

- PH

Pleckstrin homology

- pY

phosphorylated tyrosine

- RA

Ras associating

- SH2

Src homology 2

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- Y2H

Yeast 2-hybrid

Footnotes

Supporting information may be found in the online version of this paper.

References

- Akira S, Hemmi H. Recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by TLR family. Immunol Lett. 2003;85:85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Maghrebi M, Brule H, Padkina M, Allen C, Holmes WM, Zehner ZE. The 3′ untranslated region of human vimentin mRNA interacts with protein complexes containing eEF-1gamma and HAX-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:5017–5028. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslanidis C, de Jong PJ. Ligation-independent cloning of PCR products (LIC-PCR) Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6069–6074. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brescia PJ, Ivancic M, Lyons BA. Assignment of backbone 1H, 13C, and 15N resonances of human Grb7-SH2 domain in complex with a phosphorylated peptide ligand. J Biomol NMR. 2002;23:77–78. doi: 10.1023/a:1015345302576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu PY, Huang LY, Hsu CH, Liang CC, Guan JL, Hung TH, Shen TL. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Grb7 by FAK in the regulation of cell migration, proliferation, and tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(30):20215–20226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depetris RS, Wu J, Hubbard SR. Structural and functional studies of the Ras-associating and pleckstrin-homology domains of Grb10 and Grb14. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:833–839. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadeel B, Grzybowska E. HAX-1: a multi-functional protein with emerging roles in human disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1139–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiddes RJ, Campbell DH, Janes PW, Sivertsen SP, Sasaki H, Wallasch C, Daly RJ. Analysis of Grb7 recruitment by heregulin-activated erbB receptors reveals a novel target selectivity for erbB3. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7717–7724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher AR, Cedzich A, Gretz N, Somlo S, Witzgall R. The polycystic kidney disease protein PKD2 interacts with Hax-1, a protein associated with the actin cytoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4017–4022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han DC, Guan JL. Association of focal adhesion kinase with Grb7 and its role in cell migration. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24425–24430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han DC, Shen TL, Guan JL. Role of Grb7 targeting to focal contacts and its phosphorylation by focal adhesion kinase in regulation of cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28911–28917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivancic M, Spuches AM, Guth EC, Daugherty MA, Wilcox DE, Lyons BA. Backbone nuclear relaxation characteristics and calorimetric investigation of the human Grb7-SH2/erbB2 peptide complex. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1556–1569. doi: 10.1110/ps.041102305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Zhang W, Kondo K, Klco JM, St Martin TB, Dufault MR, Madden SL, Kaelin WG, Jr, Nacht M. Gene expression profiling in a renal cell carcinoma cell line: dissecting VHL and hypoxia-dependent pathways. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:453–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Nakajima K, Igarashi M, Morita T, Tanaka M, Suzuki M, Yokoyama A, Matsuda G, Kato K, Kanamori M, Hirai K. Interaction of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen leader protein (EBNA-LP) with HS1-associated protein X-1: implication of cytoplasmic function of EBNA-LP. J Virol. 2000;74:10104–10111. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.21.10104-10111.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavey SF, Arend LJ, Dare H, Dressler GR, Briggs JP, Margolis BL. Expression of Grb7 growth factor receptor signaling protein in kidney development and in adult kidney. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:F770–F776. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.5.F770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AY, Lee Y, Park YK, Bae KH, Cho S, Lee do H, Park BC, Kang S, Park SG. HS 1-associated protein X-1 is cleaved by caspase-3 during apoptosis. Mol Cells. 2008;25:86–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WB, Feng J, Geng SM, Zhang PY, Yan XN, Hu G, Zhang CQ, Shi BJ. Induction of apoptosis by Hax-1 siRNA in melanoma cells. Cell Biol Int. 2009;33:548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysa B, Tartler U, Wolf R, Arenberger P, Benninghoff B, Ruzicka T, Hengge UR, Walz M. Gene expression in actinic keratoses: pharmacological modulation by imiquimod. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1150–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manser J, Roonprapunt C, Margolis B. C. elegans cell migration gene mig-10 shares similarities with a family of SH2 domain proteins and acts cell non-autonomously in excretory canal development. Dev Biol. 1997;184:150–164. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirmohammadsadegh A, Tartler U, Michel G, Baer A, Walz M, Wolf R, Ruzicka T, Hengge UR. HAX-1, identified by differential display reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, is overexpressed in lesional psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:1045–1051. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter CJ, Matthews JM, Mackay JP, Pursglove SE, Schmidberger JW, Leedman PJ, Pero SC, Krag DN, Wilce MC, Wilce JA. Grb7 SH2 domain structure and interactions with a cyclic peptide inhibitor of cancer cell migration and proliferation. BMC Struct Biol. 2007;7:58. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-7-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter CJ, Wilce MC, Mackay JP, Leedman P, Wilce JA. Grb7-SH2 domain dimerisation is affected by a single point mutation. Eur Biophys J. 2005;34:454–460. doi: 10.1007/s00249-005-0480-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhika V, Onesime D, Ha JH, Dhanasekaran N. Galpha13 stimulates cell migration through cortactin-interacting protein Hax-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49406–49413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408836200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay AG, Keppler MD, Jazayeri M, Thomas GJ, Parsons M, Violette S, Weinreb P, Hart IR, Marshall JF. HS1-associated protein X-1 regulates carcinoma cell migration and invasion via clathrin-mediated endocytosis of integrin alphavbeta6. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5275–5284. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siamakpour-Reihani S, Argiros HJ, Wilmeth LJ, Haas LL, Peterson TA, Johnson DL, Shuster CB, Lyons BA. The cell migration protein Grb7 associates with transcriptional regulator FHL2 in a Grb7 phosphorylation-dependent manner. J Mol Recognit. 2009;22:9–17. doi: 10.1002/jmr.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein D, Wu J, Fuqua SA, Roonprapunt C, Yajnik V, D'Eustachio P, Moskow JJ, Buchberg AM, Osborne CK, Margolis B. The SH2 domain protein GRB-7 is co-amplified, overexpressed and in a tight complex with HER2 in breast cancer. EMBO J. 1994;13:1331–1340. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Demoliere C, Kitamura D, Takeshita H, Deuschle U, Watanabe T. HAX-1, a novel intracellular protein, localized on mitochondria, directly associates with HS1, a substrate of Src family tyrosine kinases. J Immunol. 1997;158:2736–2744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Mori M, Akiyoshi T, Tanaka Y, Mafune K, Wands JR, Sugimachi K. A novel variant of human Grb7 is associated with invasive esophageal carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:821–827. doi: 10.1172/JCI2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai NP, Bi J, Wei LN. The adaptor Grb7 links netrin-1 signaling to regulation of mRNA translation. EMBO J. 2007;26:1522–1531. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vafiadaki E, Arvanitis DA, Pagakis SN, Papalouka V, Sanoudou D, Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A, Kranias EG. The anti-apoptotic protein HAX-1 interacts with SERCA2 and regulates its protein levels to promote cell survival. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:306–318. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velculescu VE, Zhang L, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Serial analysis of gene expression. Science. 1995;270:484–487. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman T, Williston S, Brandts JF, Lin LN. Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal Biochem. 1989;179:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik J, Girault JA, Labesse G, Chomilier J, Mornon JP, Callebaut I. Sequence analysis identifies a ras-associating (RA)-like domain in the N-termini of band 4.1/JEF domains and in the Grb7/10/14 adapter family. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;259:113–120. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Akilesh S, Wilcox DE. Isothermal titration calorimetry measurements of Ni(II) and Cu(II) binding to His, GlyGlyHis, HisGlyHis, and bovine serum albumin: a critical evaluation. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:3057–3064. doi: 10.1021/ic000036s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.