Abstract

Objective

Amnionitis (inflammation of the amnion) is the final stage of extra-placental chorioamniotic inflammation. We propose that patients with “amnionitis”, rather than “chorionitis” have a more advanced form of intra-uterine inflammation/infection and, thus, would have a more intense fetal and intra-amniotic inflammatory response than those without “amnionitis”.

Study design

The relationship between the presence of amnionitis, and a fetal and an intra-amniotic inflammatory response was examined in 290 singleton preterm births (36 weeks) with histologic chorioamnionitis. The fetal inflammatory response was determined by plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations in umbilical cord and the presence of funisitis. The intra-amniotic inflammatory response was assessed by matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8) concentration and white blood cell (WBC) count in 156 amniotic fluid (AF) samples obtained within 5 days of birth. AF was cultured for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and genital mycoplasmas. The CRP concentration was measured with a highly sensitive immunoassay.

Results

(1) Amnionitis was present in 43.1% of cases with histologic chorioamnionitis. (2) Patients with amnionitis had a significantly higher rate of funisitis and positive AF culture and a higher median umbilical cord plasma CRP, AF MMP-8 level and AF WBC count than those without amnionitis (p < 0.001 for each). (3) Among cases with amnionitis, the presence or absence of funisitis was not associated with significant differences in the median cord plasma CRP, AF MMP-8 level and AF WBC count. (4) However, the presence of amnionitis in cases with funisitis was associated with a higher median umbilical cord plasma CRP, AF MMP-8 level and AF WBC count than the absence of amnionitis in those with funisitis (p < 0.05 for each). (5) Multiple logistic regression analysis demonstrated that amnionitis was a better independent predictor of proven or suspected early-onset neonatal sepsis (odds ratio 3.8, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1–13.2, p < 0.05) than funisitis (odds ratio 1.8, 95% CI 0.5–6.1, not significant) after correction for the contribution of other potential confounding variables.

Conclusion

The involvement of the amnion in the inflammatory process of the extraplacental membranes is associated with a more intense fetal and intra-amniotic inflammatory response than chorionitis alone. This observation has clinical implications because it allows staging of the severity of the inflammatory process and assessment of the likelihood of fetal involvement.

Introduction

Microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity is frequently present in patients with preterm labour or preterm premature rupture of membranes and is a risk factor for adverse maternal outcomes and neonatal infection-related morbidity [1–10]. Microorganisms ascending from the vagina can gain access to amniotic cavity through the chorioamniotic membranes, and eventually invade the human fetus and lead to fetal inflammatory response syndrome [6,11,12]. Funisitis, inflammation of the umbilical cord, is the histologic hallmark of the fetal inflammatory response syndrome [13,14], and has been associated with an increased risk of neonatal infection-related complications [13] and cerebral palsy [15].

Ascending intra-uterine infection has been described to have four stages, and fetal infection is temporally the most advanced phase in this process (histologic chorioamnionitis with funisitis) [6]. When infection is limited to the decidua or the amnio-chorial space (localized inflammation confined to chorion-decidua), the inflammatory process is detected within the membranes (histologic chorioamnionitis) and is of maternal origin [16]. The next stage is microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity through amnion (inflammation in amnion or chorionic plate without funisitis). The intra-amniotic inflammatory process appears to be of fetal rather than maternal origin because neutrophils in the amniotic cavity of mothers with clinical chorioamnionitis (carrying male fetuses) stain positive for the Y chromosome [17]. The final stage, in which there is fetal invasion by microorganisms, often elicits a fetal inflammatory response (histologic chorioamnionitis with funisitis). Funisitis (umbilical vasculitis) and chorionic vasculitis (inflammation of the branches of umbilical vessels) are fetal responses [18,19]. However, these lesions could also occur in response to a chemotactic stimuli present in the amniotic cavity, without fetal microbial invasion. This contrasts with inflammation of the decidua, chorion, and amnion of the extraplacental fetal membranes, which is a maternal host response [19].

A previous study reported that funisitis (infiltration of the umbilical vessels by fetal neutrophils) was the least sensitive indicator of a positive amniotic fluid (AF) culture, but had the highest positive predictive value for intra-amniotic infection because it occurs late in the course of ascending infection [20]. Indeed, the presence of funisitis was associated with a stronger intra-amniotic inflammatory response, as determined by the AF white blood cell count (WBC), than the absence of funisitis [21]. On the other hand, maternal neutrophils, found in fetal membranes, are seldom found in the AF [22]. Moreover, the migration of maternal neutrophils into the amnion, which is an avascular structure [23], from decidua has been known to be very difficult, because maternal neutrophils in decidua must transmigrate across an epithelial layer and the basement membrane of chorion and chorioamniotic interface [22]. Therefore, inflammation of the amnion, which lines the amniotic cavity, is likely the most advanced stage of the maternal inflammatory response. Amnionitis may reflect the presence of strong chemotactic stimuli, located in the AF rather than in the chorion/decidua.

Inflammation of the chorioamniotic membranes is generally referred to as chorioamnionitis, which implies the presence of inflammatory cells in the extraplacental membranes (chorion and amnion). However, in many instances, the inflammatory process is limited to the chorion and does not involve the amnion. Previous studies have not addressed the clinical significance of isolated chorionitis vs. chorioamnionitis. To address this question, we conducted a study designed to examine if the presence of amnionitis is associated with a more intense fetal or intra-amniotic inflammatory response than the absence of amnionitis.

Material and methods

Study population

The relationship between the presence of amnionitis, and a fetal and intraamniotic inflammatory response was examined in 290 consecutive singleton preterm births (36 weeks’ gestation) with histologic chorioamnionitis. The cohort consisted of patients who delivered at the Seoul National University Hospital between January 1993 and December 1999. In many cases included in this study, transabdominal amniocentesis was performed to evaluate either the microbiologic status of the amniotic cavity (140 cases) or the fetal lung maturity (16 cases). The relationship among the AF culture, AF MMP-8 concentration and AF WBC count, and histologic chorioamnionitis including amnionitis and funisitis was examined in 156 cases delivered within 5 days of amniocentesis. This criterion was used to preserve a meaningful temporal relationship between the results of AF studies and the histologic findings of placenta and umbilical cord obtained at birth. Amniocentesis was performed after written informed consent was obtained. The Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital approved the collection and use of these samples and information for research purposes. The Seoul National University has a Federal Wide Assurance with the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) of the Department of Health and Human Services of the United States. Many of patients in this study were included in our previous studies.

Amniotic fluid and umbilical cord blood

AF was cultured for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and genital mycoplasma (Ureaplasma urelyticum and Mycoplasma hominis) and analysed for WBC count, according to methods previously described [24,25]. The remaining fluid was centrifuged and stored in polypropylene tubes at −70°C. MMP-8 concentrations in stored AF were measured with a commercially available enzyme-linked immuno-sorbent assay (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Little Chalfont, Bucks, UK). The sensitivity of the test was <0.3 ng/ml. Both intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were <10%. Details about this assay and its performance have been previously described [21]. Intra-amniotic inflammation was defined as an elevated AF MMP-8 concentration (>23 ng/ml), as previously reported [26].

Umbilical cord blood was collected in ethylene-diaminetetraacetic acid-containing blood collection tubes by venipuncture of the umbilical vein at birth. Samples were then centrifuged and supernatants were stored in polypropylene tubes at −70 °C. C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations in umbilical cord plasma were measured with a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Immunodiagnostik AG, Bensheim, Germany). The sensitivity of the test was 0.02 ng/ml. Both intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were <10%.

Diagnosis of histologic chorioamnionitis, funisitis, and early-onset neonatal sepsis

Histologic chorioamnionitis was defined in the presence of acute inflammatory changes on examination of a membrane roll and chorionic plate of the placenta; amnionitis was diagnosed in the presence of at least 1 focus of >5 neutrophils in amnion; funisitis was diagnosed in the presence of neutrophil infiltration into the umbilical vessel walls or Wharton’s jelly with the use of criteria previously published [27]. Clinical chorioamnionitis was diagnosed according to the definitions previously described in detail [15]. Early-onset neonatal sepsis was diagnosed in the presence of a positive blood culture result within 72 h of delivery. Early-onset neonatal sepsis was suspected in the absence of a positive culture when two or more of the following criteria were present: (1) WBC count of <5000 cells/mm3; (2) polymorphonuclear leukocyte count of <1800 cells/mm3; and (3) I/T ratio (ratio of bands to total neutrophils) >0.2. These criteria have been previously used in the paediatric and obstetric literature [12].

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney U-test was used for comparison of continuous variables. Comparisons of proportions were performed with the Fisher’s exact test. Logistic regression analysis was used to explore the effect of gestational age at delivery, the cause of preterm delivery and parity (≥1) on pregnancy and neonatal outcome according to the presence or absence of amnionitis, and to examine the relationship between amnionitis and early-onset neonatal sepsis (proven or suspected), controlling for the effect of any other potential confounding variables. Statistical significance was defined as a p < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of study population

Table 1 demonstrates the clinical characteristics according to the presence or absence of amnionitis among the cases of preterm births (36 weeks’ gestation) with histologic chorioamnionitis. Patients with amnionitis had a lower median gestational age at amniocentesis, as well as a lower parity (>1), than did those without amnionitis.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population according to the presence or absence of amnionitis among the cases of preterm births (36 weeks’ gestation) with histologic chorioamnionitis.

| Absence of amnionitis | Presence of amnionitis | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 165 | n = 125 | ||

| 57% (165/290) | 43% (125/290) | ||

| Mean maternal age, years (mean ± SD) | 29.1 ± 4.3 | 30.0 ± 4.1 | NS |

| Median gestational age at amniocentesis, weeks (median and range)a (No.) | 32.7 (19.7–36.0) | 30.0 (16.9–35.1) | <0.001 |

| Male newborn | 57% | 50% | NS |

| Parity ≥1 | 58% | 40% | <0.005 |

| Causes of preterm delivery | |||

| Preterm labour | 38% | 34% | NS |

| Preterm premature rupture of membranes | 39% | 62% | <0.001 |

| Maternal fetal indication | 23% | 4% | <0.001 |

One hundred and fifty-six patients who underwent amniocentesis within 5 days of birth were included in this analysis to preserve a meaningful temporal relationship between the results of amniotic fluid studies and those of placental histologic examination and perinatal outcome.

NS, not significant.

Amnionitis and pregnancy and neonatal outcome

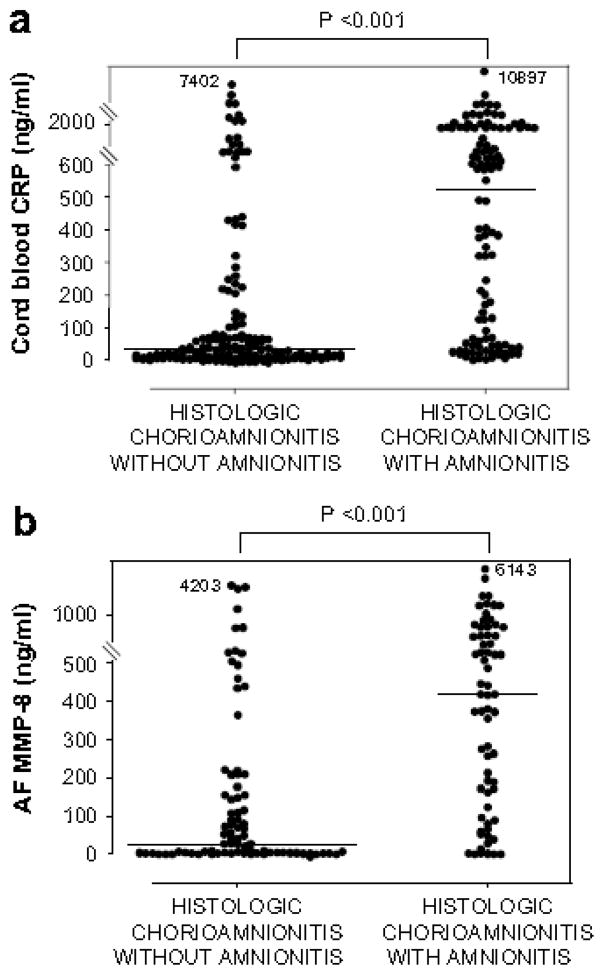

Table 2 describes the pregnancy and neonatal outcome of the study groups. Patients with amnionitis had a lower median gestational age at delivery and mean birth weight than those without amnionitis. Patients with amnionitis also had higher rates of clinical chorioamnionitis, funisitis, inflammation of the chorionic plate, grade 2 chorio-deciduitis, positive AF culture, intra-amniotic inflammation, and the frequency of umbilical cord plasma CRP concentration above 200 ng/ml than those without amnionitis (see Table 2). Regarding neonatal morbidity, the cases with amnionitis had a higher rate of proven or suspected early-onset neonatal sepsis. These differences in outcome remained significant after adjusting for gestational age at delivery, the cause of preterm delivery and parity (>1) by logistic regression analysis. The development of amnionitis in the cases of preterm births (36 weeks’ gestation) was strongly associated with a higher level of cord plasma CRP at birth, and higher AF WBC counts and AF MMP-8 concentrations in cases delivered within 5 days of amniocentesis (see Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Pregnancy and neonatal outcome of the study population according to the presence or absence of amnionitis among the cases of preterm births (36 weeks’ gestation) with histologic chorioamnionitis.

| Absence of amnionitis | Presence of amnionitis | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=165 | N=125 | Unadjusted | Adjustedc | |

| 57% (165/290) | 43% (125/290) | |||

| Median gestational age at delivery, weeks (median and range) | 33.4 (19.7–36.0) | 30.6 (17.4–35.7) | <0.001 | - |

| Mean birth weight, g (mean ± SD) | 1853 ± 667 | 1541 ± 636 | <0.001 | - |

| Clinical chorioamnionitis | 4% | 17% | <0.001 | <0.05 |

| Funisitis | 27% | 78% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Inflammation of chorionic plate | 11% | 55% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Chorio-deciduitis | 93% | 98% | <0.05 | NS |

| Chorio-deciduitis, grade 2 | 10% | 50% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Positive amniotic fluid culturea | 22% (18/82) | 44% (31/70) | <0.01 | <0.05 |

| Intra-amniotic inflammationb | 55% (45/82) | 90% (59/66) | <0.001 | <0.005 |

| Umbilical cord plasma CRP ≥200 ng/mle | 22% (33/151) | 64% (68/106) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Proven early-onset neonatal sepsisd | 2% (3/146) | 7% (8/109) | 0.059 | 0.062 |

| Proven or suspected early-onset neonatal sepsisd | 11% (16/146) | 33% (36/109) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

NS, not significant.

Of 156 cases who underwent amniocentesis within 5 days of birth, AF culture results were available in 152 cases.

Of 156 cases who underwent amniocentesis within 5 days of birth, 148 patients were included in this analysis, because the test of AF MMP-8 concentration was not performed in 8 cases due to the limited amount of the remaining fluid.

Adjusted for gestational age at delivery, the cause of preterm delivery and parity (≥1) (logistic regression analysis).

Thirty-five neonates were excluded from the analysis because they died shortly after delivery as a result of extreme prematurity (n = 25) or anomaly (n = 5) or were delivered at another institution (n = 5) and thus could not be evaluated with respect to the presence or absence of neonatal complications.

Of 290 cases which met the entry for this study, 257 patients had an umbilical cord plasma CRP concentration at birth; however, 33 patients did not have an umbilical cord CRP concentration at birth because of the limited amount of the remaining plasma.

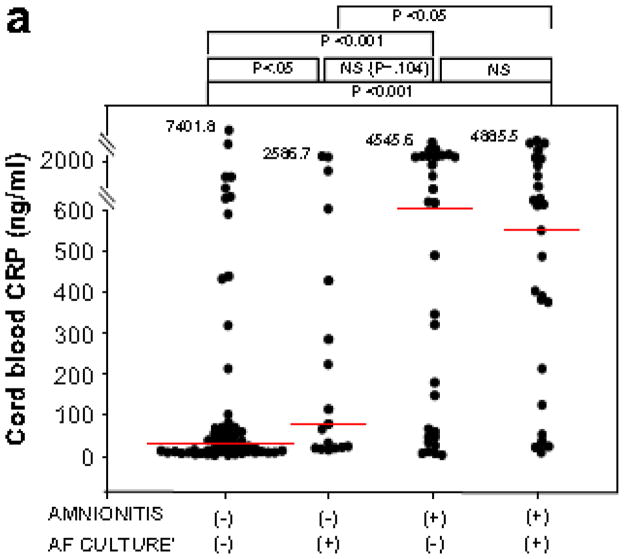

Figure 1.

CRP concentrations in umbilical cord plasma at birth (a), and AF MMP-8 concentrations (b) and AF WBC counts (c) according to the presence or absence of amnionitis.

Cord plasma CRP: amnionitis (−), median, 29.1 ng/ml (range, 1.9–7401.8 ng/ml) vs. amnionitis (+), median, 520.8 ng/ml (range, 2.2–10897.4 ng/ml) (p < 0.001); AF MMP-8: amnionitis (−), median, 29.2 ng/ml (range, 0.3–4202.7 ng/ml) vs. amnionitis (+), median, 416.2 ng/ml (range, 0.3–6142.6 ng/ml) (p < 0.001); AF WBC: amnionitis (−), median, 6 cells/mm3 (range, 0–4320 cells/mm3) vs. amnionitis (+), median, 884 cells/mm3 (range, 0–19764 cells/mm3) (p < 0.001).

CRP concentrations in umbilical cord plasma, AF MMP-8 concentrations and AF WBC counts according to the presence or absence of amnionitis and funisitis

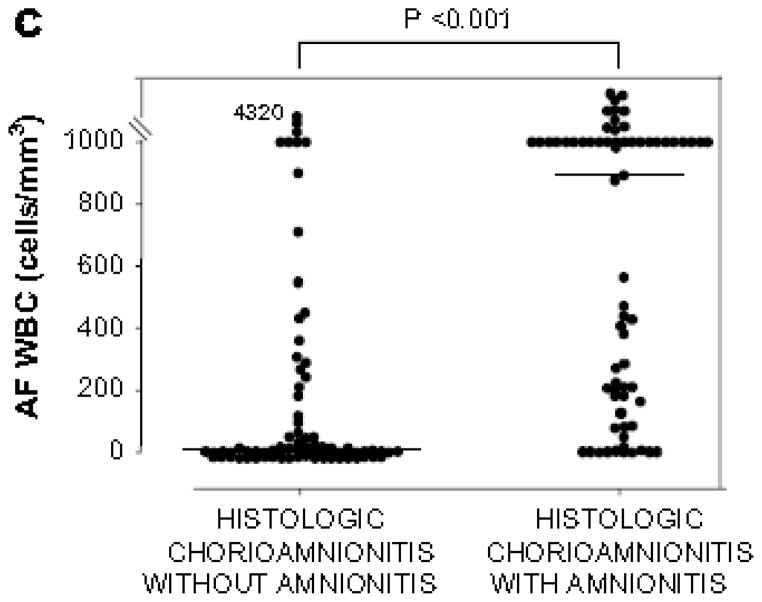

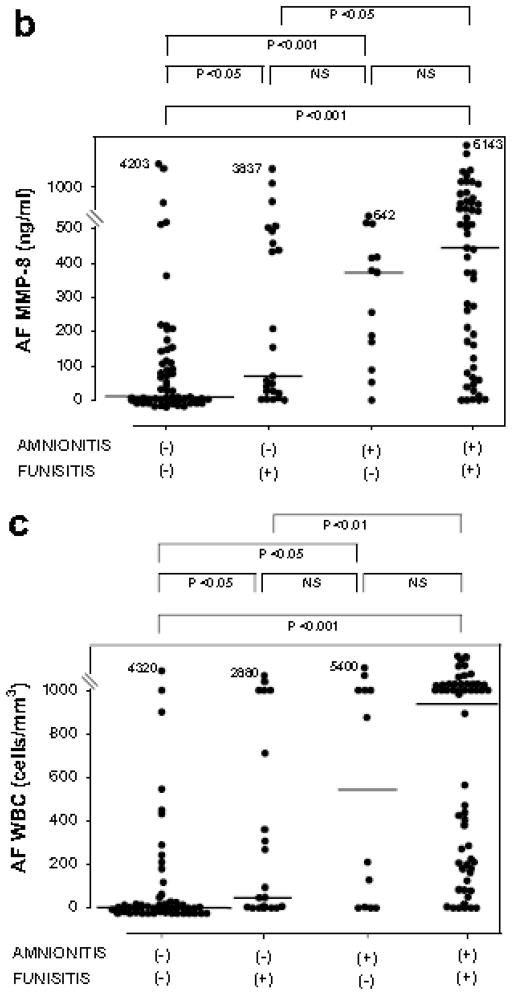

Fig. 2 shows CRP concentrations in umbilical cord plasma at birth, and AF MMP-8 concentrations and AF WBC counts according to the presence or absence of amnionitis and funisitis. Among cases with amnionitis, the presence or absence of funisitis was not associated with a significant difference in the median cord plasma CRP, AF MMP-8 concentrations and AF WBC counts (p > 0.1 for each). However, among cases with funisitis, the presence of amnionitis was associated with a significantly higher median cord plasma CRP, AF MMP-8 concentrations and AF WBC counts, compared to the absence of amnionitis (p < 0.05 for each).

Figure 2.

CRP concentrations in umbilical cord plasma at birth (a), and AF MMP-8 concentrations (b) and AF WBC counts (c) according to the involvement of the inflammation in amnion or umbilical cord.

Cord plasma CRP: amnionitis (−) & funisitis (−), median, 22.1 ng/ml (range, 1.9–7401.8 ng/ml) vs. amnionitis (−) & funisitis (+), median, 120.8 ng/ml (range, 4.9–5555.0 ng/ml) vs. amnionitis (+) & funisitis (−), median, 125.6 ng/ml (range, 3.0–5315.8 ng/ml) vs. amnionitis (+) & funisitis (−), median, 750.7 ng/ml (range, 2.2–10897.4 ng/ml); AF MMP-8: amnionitis (−) & funisitis (−), median, 8.7 ng/ml (range, 0.3–4202.7 ng/ml) vs. amnionitis (−) & funisitis (+), median, 69.6 ng/ml (range, 0.3–3836.8 ng/ml) vs. amnionitis (+) & funisitis (−), median, 373.1 ng/ml (range, 0.3–642.1 ng/ml) vs. amnionitis (+) & funisitis (+), median, 444.1 ng/ml (range, 0.3–6142.6 ng/ml); AF WBC: amnionitis (−) & funisitis (−), median, 3 cells/mm3 (range, 0–4320 cells/mm3) vs. amnionitis (−) & funisitis (−), median, 45 cells/mm3 (range, 0–2880 cells/mm3) vs. amnionitis (+) & funisitis (−), median, 543 cells/mm3 (range, 0–5400 cells/mm3) vs. amnionitis (+) & funisitis (+), median, 937 cells/mm3 (range, 0–19764 cells/mm3).

(Each p values is shown in graphs.)

CRP concentrations in umbilical cord plasma, AF MMP-8 concentrations and AF WBC counts according to the results of AF culture and the presence or absence of amnionitis

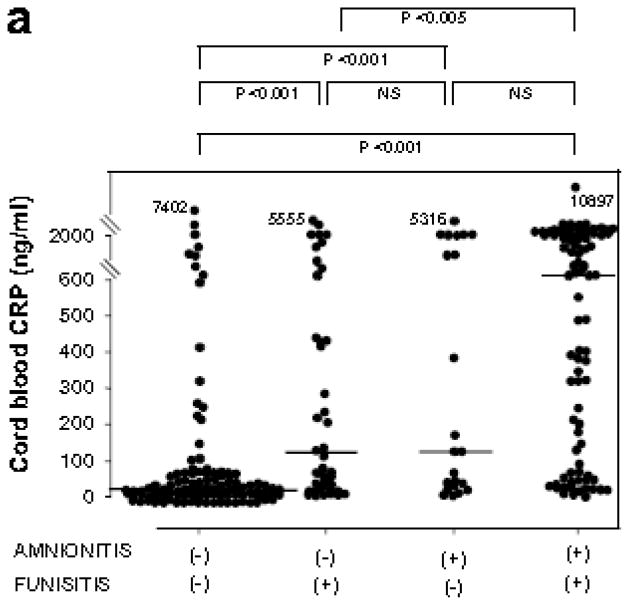

Fig. 3 shows CRP concentrations in umbilical cord plasma at birth, and AF MMP-8 concentrations and AF WBC counts according to the results of AF culture and the presence or absence of amnionitis.

Figure 3.

CRP concentrations in umbilical cord plasma at birth (a) AF MMP-8 concentrations (b) and AF WBC counts (c) according to the results of amniotic fluid culture and the presence or absence of amnionitis.

Patients with amnionitis had significantly higher median umbilical cord plasma CRP, AF MMP-8 concentrations and AF WBC counts than those without amnionitis among cases with a positive AF culture. Cord plasma CRP: median, 551.4 ng/ml (range, 9.5–4885.5 ng/ml) vs. median, 78.3 ng/ml (range, 16.3–2586.7 ng/ml); AF MMP-8: median, 594.0 ng/ml (range, 0.3–5019.5 ng/ml) vs. median, 26.0 ng/ml (range, 0.7–870.8 ng/ml); AF WBC: median, 981 cells/mm3 (range, 18–19764 cells/mm3) vs. median, 6 cells/mm3 (range, 0–1000 cells/mm3)) and also among cases with a negative AF culture (Cord plasma CRP: median, 639.8 ng/ml (range, 2.2–4545.6 ng/ml) vs. median, 27.9 ng/ml (range, 1.9–7401.8 ng/ml); AF MMP-8: 373.1 ng/ml (range, 0.5–6142.6 ng/ml) vs. median, 41.8 ng/ml (range, 0.3–4202.7 ng/ml); AF WBC: median, 876 cells/mm3 (range, 0–5800cells/mm3) vs. median, 5 cells/mm3 (range, 0–4320 cells/mm3).

(Each p values is shown in graphs.)

There were no significant differences in the median AF MMP-8 and AF WBC count between cases with a positive AF culture and those with a negative AF culture among cases without amnionitis and also among cases with amnionitis (p > 0.1 for each, Fig. 3b and c). However, patients with amnionitis had significantly higher median umbilical cord plasma CRP, AF MMP-8 concentrations and AF WBC counts than those without amnionitis among cases with a positive AF culture and also among cases with a negative AF culture (p < 0.05 for each, Fig. 3).

Relationship between clinical or laboratory parameters and early-onset neonatal sepsis

To determine the relative value of clinical and laboratory parameters in the prediction of proven or suspected early-onset neonatal sepsis, we conducted multiple logistic regression analysis with variables that could be considered as risk factors for early-onset neonatal sepsis and clinical parameters such as parity and preterm premature rupture of membranes that were significantly different according to the presence or absence of amnionitis. Of all these independent variables, amnionitis and fetal inflammatory response (defined as an elevated umbilical cord plasma CRP concentration at birth (>200 ng/ml)) retained statistical significance in the prediction of proven or suspected early-onset neonatal sepsis after other confounding variables were adjusted (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relationship of various independent variables with proven or suspected early-onset neonatal sepsis by overall logistic regression analysis

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amnionitis | 3.8 | 1.1–13.2 | <0.05 |

| Funisitis | 1.8 | 0.5–6.1 | NS |

| Preterm premature rupture of membranes before 30 weeks | 0.4 | 0.1–1.6 | NS |

| Preterm delivery before 32 weeks | 2.4 | 0.8–7.6 | NS |

| Intra-amniotic inflammation | 0.4 | 0.1–1.3 | NS |

| Positive amniotic fluid culture | 0.8 | 0.3–2.1 | NS |

| Umbilical cord plasma CRP ≥200 ng/ml | 4.0 | 1.4–11.7 | <0.01 |

| Parity ≥1 | 0.7 | 0.2–1.7 | NS |

NS, not significant, CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Principal findings of this study

(1) The involvement of the amnion in the inflammatory process, recognized as histological chorioamnionitis, is associated with a more intense fetal and intra-amniotic inflammatory response than inflammation limited to the chorion layer. (2) The presence of funisitis is associated with a more severe fetal and intra-amniotic inflammatory response than the absence of funisitis; however, this relationship disappears when the inflammatory process in the fetal membranes involves the amnion (amnionitis).

Amnionitis, an intra-amniotic/fetal inflammatory response, and early-onset neonatal sepsis

The involvement of the amnion (amnionitis) is the most advanced stage of the maternal inflammatory response in the extraplacental membranes. Therefore, one may expect that amnionitis is a better predictor of the presence and magnitude of the intra-amniotic and fetal inflammatory response than chorionitis. Our data supports that this is the case. Indeed, the development of amnionitis in the extraplacental membranes was related with a strong fetal and intra-amniotic inflammatory response, and a higher rate of proven or suspected early-onset neonatal sepsis (see Table 2 and Fig. 1). These results parallel the previous findings reported by Van Hoeven et al. [28] and Keenan et al. [29], that more advanced stages of inflammatory response are associated with increased severity of clinical injury including neonatal sepsis or perinatal death. Moreover, our data indicate that amnionitis is more valuable in the identification of a more intense fetal and intra-amniotic inflammatory response and is a better independent predictor of proven or suspected early-onset neonatal sepsis than funisitis in preterm gestations with histologic chorioamnionitis (see Fig. 2 and Table 3).

Why is the presence of amnionitis associated with a more severe intra-amniotic and fetal inflammatory response?

Possible explanations for our findings include: (1) Considering the anatomic location of amnion that lines the amniotic cavity, amnionitis may be a more direct pathologic parameter of intra-amniotic inflammation than an inflammatory change in any other anatomic section of placenta and umbilical cord. (2) An inflammatory change of the amnion may reflect that a strong chemotactic stimuli is present within the amniotic cavity in most cases. Indeed, although an intra-amniotic inflammation occurred in 55% of cases (45/82) with histologic chorioamnionitis but without amnionitis, 90% of cases (59/66) with the development of amnionitis had an intra-amniotic inflammation (Table 2). (3) It may be very difficult that an inflammatory change develops in the amnion, because neutrophils in adjacent anatomic sections such as outer maternal decidua must transmigrate and infiltrate on the amnion through the chorion and chorioamniotic interface. Therefore, the development of amnionitis in histologic chorioamnionitis may not occur until a most severe intra-amniotic and fetal inflammatory response has been established.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Major strengths of the study are: (1) its large cohort of consecutive women with singleton preterm births (36 weeks’ gestation) with histologic chorioamnionitis (n = 290); (2) it includes several markers of infection and inflammation, including AF culture, AF MMP-8 concentration, and AF WBC count, as well as umbilical cord plasma CRP concentration and therefore, this study examines the inflammatory response in the relevant compartments among study groups (Figs. 2 and 3); and (3) it explores the relationship between proven or suspected early-onset neonatal sepsis and the presence of amnionitis in preterm gestations with histologic chorioamnionitis after considering almost all potential risk factors (Table 3). One potential weakness of the study is that it does not identify the temporal relationship between the development of human amnionitis and microbial invasion of the chorioamniotic space. However, such a temporal relationship is difficult to determine in humans.

Clinical significance of this study

The presence of inflammation of the amnion (amnionitis) is associated with a more intense fetal and intra-amniotic inflammatory response than the lack of inflammatory cells in this layer (inflammation confined to the chorion). Indeed, amnionitis is a better independent predictor of proven or suspected early-onset neonatal sepsis (odds ratio 3.8, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1–13.2) than funisitis, considered as the final stage during ascending intra-uterine infection. Moreover amnionitis shows the similar predictive value of proven or suspected early-onset neonatal sepsis as compared with a fetal inflammatory response, defined as an elevated umbilical cord plasma CRP concentration at birth (>200 ng/ml) (odds ratio 4.0, 95% CI 1.4–11.7) (Table 3).

Unanswered questions and proposals for future research

The pathway of ascending intra-uterine infection has not been clearly clarified. One hypothesis is that microorganisms may ascend to broadly colonize the chorioamniotic membranes and decidua and, only at a later stage, gain access to the AF by way of amnion in the case of preterm labour with intact membranes. Alternatively, microorganisms from the vagina and the cervix may transverse the membranes adjacent to the cervix and colonize the AF without substantial involvement of the deciduas, chorioamniotic membranes, and amnion as this appears to be the case in preterm premature rupture of membranes or cervical insufficiency. It is important to determine the relationship among bacteria found in the choriamniotic membranes, intra-amniotic and/or fetal inflammatory response, and inflammation of different components of the placenta. This will improve the understanding of the pathway of infection as well as the nature of the inflammatory response in the maternal and fetal compartments of the placenta.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by General Research Grants (GRG), Korea Science and Engineering Foundation, Republic of Korea (R01-2006-000-10607-0) and, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS.

References

- 1.Bobitt JR, Hayslip CC, Damato JD. Amniotic fluid infection as determined by transabdominal amniocentesis in patients with intact membranes in premature labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;140:947–52. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hameed C, Tejani N, Verma UL, Archbald F. Silent chorioamnionitis as a cause of preterm labor refractory to tocolytic therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;149:726–30. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahbeh CJ, Hill GB, Eden RD, Gall SA. Intra-amniotic bacterial colonization in premature labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148:739–43. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90558-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gravett MG, Hummel D, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK. Preterm labor associated with subclinical amniotic fluid infection and with bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:229–37. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198602000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leigh J, Garite TJ. Amniocentesis and the management of premature labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:500–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero R, Mazor M. Infection and preterm labor. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1988;31:553–84. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skoll MA, Moretti ML, Sibai BM. The incidence of positive amniotic fluid cultures in patients preterm labor with intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:813–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoon BH, Chang JW, Romero R. Isolation of Ureaplasma urealyticum from the amniotic cavity and adverse outcome in preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:77–82. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romero R, Sirtori M, Oyarzun E, Avila C, Mazor M, Callahan R, et al. Infection and labor. V. Prevalence, microbiology, and clinical significance of intra-amniotic infection in women with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:817–24. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watts DH, Krohn MA, Hillier SL, Wener MH, Kiviat NB, Eschenbach DA. Characteristics of women in preterm labor associated with elevated C-reactive protein levels. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:509–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romero R, Gomez R, Ghezzi F, Yoon BH, Mazor M, Edwin SS, et al. A fetal systemic inflammatory response is followed by the spontaneous onset of preterm parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:186–93. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez R, Romero R, Ghezzi F, Yoon BH, Mazor M, Berry SM. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:194–202. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon BH, Romero R, Park JS, Kim M, Oh SY, Kim CJ, et al. The relationship among inflammatory lesions of the umbilical cord (funisitis), umbilical cord plasma interleukin 6 concentration, amniotic fluid infection, and neonatal sepsis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1124–9. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.109035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon BH, Romero R, Shim JY, Shim SS, Kim CJ, Jun JK. C-reactive protein in umbilical cord blood: a simple and widely available clinical method to assess the risk of amniotic fluid infection and funisitis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003;14:85–90. doi: 10.1080/jmf.14.2.85.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoon BH, Romero R, Park JS, Kim CJ, Kim SH, Choi JH, et al. Fetal exposure to an intra-amniotic inflammation and the development of cerebral palsy at the age of three years. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:675–81. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.104207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNamara MF, Wallis T, Qureshi F, Jacques SM, Gonik B. Determining the maternal and fetal cellular immunologic contributions in preterm deliveries with clinical or subclinical chorioamnionitis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1997;5:273–9. doi: 10.1155/S1064744997000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sampson JE, Theve RP, Blatman RN, Shipp TD, Bianchi DW, Ward BE, et al. Fetal igin of amniotic fluid polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)80015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guzick DS, Winn K. The association of chorioamnionitis with preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:11–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overbach AM, Daniel SJ, Cassady G. The value of umbilical cord histology in the management of potential perinatal infection. J Pediatr. 1970;76:22–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(70)80125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romero R, Salafia CM, Athanassiadis AP, Hanaoka S, Mazor M, Sepulveda W, et al. The relationship between acute inflammatory lesions of the preterm placenta and amniotic fluid microbiology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1382–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91609-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park JS, Romero R, Yoon BH, Moon JB, Oh SY, Han SY, et al. The relationship between amniotic fluid matrix metalloproteinase-8 and funisitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1156–61. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SD, Kim MR, Hwang PG, Shim SS, Yoon BH, Kim CJ. Chorionic plate vessels as an origin of amniotic fluid neutrophils. Pathol Int. 2004;54:516–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2004.01659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourne GL. The microscopic anatomy of the human amnion and chorion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1960;79:1070–3. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(60)90512-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoon BH, Yang SH, Jun JK, Park KH, Kim CJ, Romero R. Maternal blood C-reactive protein, white blood cell count, and temperature in preterm labor: a comparison with amniotic fluid white blood cell count. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:231–7. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon BH, Jun JK, Park KH, Syn HC, Gomez R, Romero R. Serum C-reactive protein, white blood cell count, and amniotic fluid white blood cell count in women with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:1034–40. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(96)00339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shim SS, Romero R, Hong JS, Park CW, Jun JK, Kim BI, et al. Clinical significance of intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon BH, Romero R, Kim CJ, Jun JK, Gomez R, Choi JH, et al. Amniotic fluid interleukin-6: a sensitive test for antenatal diagnosis of acute inflammatory lesions of preterm placenta and prediction of perinatal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:960–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Hoeven KH, Anyaegbunam A, Hochster H, Whitty JE, Distant J, Crawford C, et al. Clinical significance of increasing histologic severity of acute inflammation in the fetal membranes and umbilical cord. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med. 1996;16:731–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keenan WJ, Steichen JJ, Mahmood K, Altshuler G. Placental pathology compared with clinical outcome: a retrospective blind review. Am J Dis Child. 1977;131:1224–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1977.02120240042009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]