Abstract

Permanent makeup is a cosmetic tattoo that is used to enhance one’s appearance, and which has become more popular among middle-aged and elderly women. A couple of benefits seem to be associated with permanent tattoos in the elderly: saving time (wake up with makeup); poor eyesight (difficult to apply makeup); and saving money. On the other hand, cosmetic tattoos bear the same risks as other tattoo procedures. We report on fading and unintended hyperpigmentation after tattooing on eyebrows and eyelids, and discuss the scientific and anatomical background behind the possible cause. Dermatochalasis may be a possible risk factor for excessive unwanted discolorations. Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser is an appropriate and safe therapeutic tool that can manage such adverse effects. Consumer protection warrants better information and education of the risks of cosmetic tattoos – in particular, for elderly women.

Keywords: permanent makeup, cosmetic tattoos, adverse effects, dermatochalasis, Q-switched Nd:YAG laser

Introduction

Women can successfully employ cosmetic products to manipulate their appearance. It was found that, in contrast to bare skin, Caucasian women who wore makeup were perceived as healthier and more confident, and they were regarded as having greater earning potential and holding more prestigious jobs.1

A desire for attractiveness is not a matter of age. The positive effect on self-perception by facial makeup has also been validated in elderly women aged 60–96 years.2

Permanent makeup by micropigmentation has become a part of fashion, promising certain benefits, particularly for elderly women.2 Parlors offer this technique for the eyebrows, eyelids, and lips, which are the most common facial applications.2

As with other types of tattoos, a variety of adverse effects have been observed with permanent makeup, such as fanning, fading, and scarring;3 granulomatous inflammatory reactions;4 allergic contact dermatitis;5 phototoxicity;6 hypomelanosis;7 and infections.8,9

We describe two patients with unintended pigmentation of the surrounding skin as an extreme and early variant of fanning, and discuss some possible risk factors related to facial aging.

Case reports

Patient 1

An 84-year-old woman received permanent eyebrow makeup in a parlor some time ago. The second time, she asked for eyelid contouring. A few days after a single tattooing session of her lower eyelids, she observed unwanted pigmentation on the left side of her face.

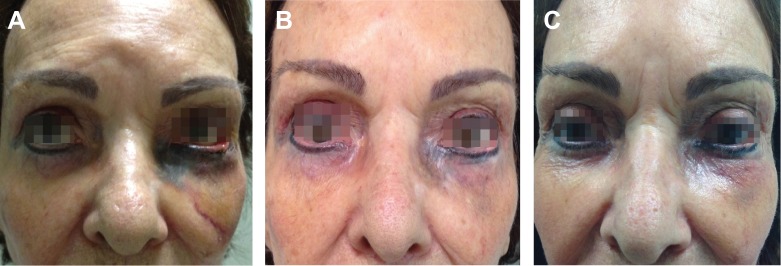

Upon examination, we found that the woman presented with dermatochalasis and malar mounds. The left lower eyelid and the lateral nose presented with dark hyperpigmentation. Streak-like hyperpigmentation was seen on her cheek along the lower border of the prezygomatic space (Figure 1A). On the glabella, a swollen lymph node was noted.

Figure 1.

Patient 1.

Notes: (A) Aspect before laser treatment. (B) Result after the second session. (C) Final result after three sessions.

We diagnosed a massive displacement of micropigments following eyelid tattooing and discussed possible treatment options with the patient.

She was treated with three consecutive sessions of a Q-switched 1,064 nm neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser (Photosilk Plus; DEKA, Calenzano, Italy). The interval between the sessions was 4–5 weeks.

For Q-switched Nd:YAG laser, a pulse width of 2 ms was chosen; the pulse repetition rate ranged from 0.5–3 Hz, and fluence ranged from 4–16 J/cm2. The spot size diameter was 4 mm. Post-treatment topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream was used for 3 days. The patient was instructed to avoid direct sun exposure.

The therapeutic outcome is shown in Figures 1B and C. The glabellar lymph node swelling completely disappeared. The patient was very satisfied with these results.

Patient 2

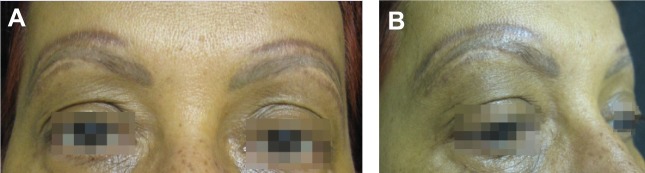

A 56-year-old woman received a cosmetic tattoo of the eyebrows by micropigmentation. One month later, the same tattooing professional tried to correct some residual irregularities on both eyebrows using dark pigments. As a consequence, the eyebrow contour remained irregular with some fanning. One month later, the professional attempted to correct this by tattooing with white pigments. This was followed by an inflammatory response, and the patient was treated with topical clobetasol. One month later, the same nonmedical professional tried to correct the unfavorable result using another tattoo for the entire region. As a consequence, the visual aspect worsened (Figures 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Patient 2.

Notes: Aspect before treatment. (A) Frontal view, (B) lateral view.

Approximately 6 months after the initial procedure, the patient became depressed and reclusive. She was referred to our clinic for consultation.

Upon examination, she presented with an unnatural look of multicolored eyebrows. At that time, no inflammatory reaction was noted. Since the pigment remained in the skin, the previously described inflammation could have been a foreign body reaction. However, no biopsy for clarification was wanted.

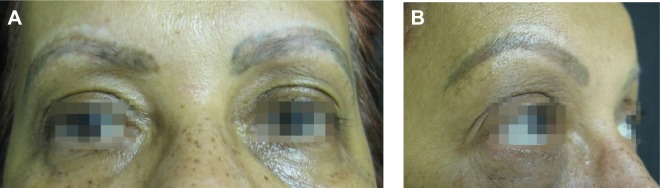

We suggested a series of laser treatments to reduce color mismatch and pigmentations. She was treated with seven consecutive monthly sessions of Q-switched 1,064 nm Nd:YAG laser (Photosilk Plus). The laser parameters were the same as for patient 1. A temporary local swelling was observed following the first three sessions – probably a consequence of pigment fragmentation by laser action. She was treated successfully with clobetasol 0.05% ointment. There were no other side effects. The final outcome was very satisfying for the patient (Figures 3A and B).

Figure 3.

Patient 2.

Notes: Final result after seven laser sessions. (A) Frontal view, (B) lateral view.

Discussion

In middle-aged and elderly women, body image remains important for self-esteem. Permanent makeup procedures by micropigmentation are popular among them.2 Procurement cues for permanent makeup include self-improvement and friend’s appearance. The arguments in favor of permanent makeup are: saving time (wake up with makeup); it is waterproof; no application, so easier with handicaps such as poor eyesight or arthritic hands; and it saves money.10

Permanent makeup is a type of tattooing that uses micropigmentation. In our patients, black ink was used (in patient 2, white pigment was also used). Black inks contain carbon nanoparticles, additives, and water. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons have also been identified.11 Nanoparticles are capable of inducing reactive oxygen species, mainly of the peroxyl radical type, when aggregating in water. Due to this, unspecific inflammatory reactions may occur.12

Although adverse effects following cosmetic tattoos are not age-specific, facial aging may bear an additional risk factor for extensive fanning. Micropigments of the brow and lid region may spread within the lymphatic vessels to the midface and/or forehead. The frontal collecting lymph vessels have first lymph nodes in the deep aspect of the subcutaneous tissue. Lymph vessels arising on the lateral nasal wall travel obliquely down and lateral. They can merge with a lymph-collecting vessel at the inner canthus.13

Eyelid lymphatics become dilated in dermatochalasis and malar mounds, both signs of facial aging. Dermatochalasis is a combination of epidermal thinning and a loss of elastin fibers leading to laxity of the skin. Malar mounds develop due to weakening of orbicularis retaining filaments.14,15 Both are factors that might have contributed to the massive discoloration in patient 1. Streak-like hyperpigmentation over her left cheek followed the lower border of the prezygomatic space, which is anatomically characterized by zygomaticocutaneous ligaments.16

Spreading of ink may rapidly follow permanent eyelash makeup due to lymphatic distribution.17,18 Pigmentation of limbus and cornea have also been observed.19

Tattooing is known for its possible severe adverse effects including inflammatory reactions (as possibly occurred in patient 2), Koebnerization of existing dermatoses, transmission of infectious diseases, and the development of cancer.20–22 Cosmetic micropigmentation is not an exception to the rule, as we have demonstrated (Table 1).

Table 1.

Adverse effects of cosmetic blepharopigmentation (permanent makeup)

| Authors | Patient(s) | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|

| Bee et al25 | 68-year-old woman | Granulomatous pseudotumor, loss of lashes, and margin irregularities 7 years after permanent makeup |

| Seol et al26 | 31-year-old woman | 2 hours after blepharopigmentation, epithelial defects and dry eye syndrome for 12 months |

| Liao et al7 | 67-year-old woman | Hypopigmentation 8 years after eyeliner tattoo |

| Rudkin27 | One case; no further data | Corneal pigmentation, corneal defect, and conjunctivitis |

| Moshirfar et al19 | 54-year-old woman | Conjunctival and corneal hyperpigmentation |

| De et al28 | 46-year-old woman | Penetration of the eyelid by the tattoo needle with conjunctival pigmentation and conjunctivitis |

| Calzado et al29 | 58-year-old woman | Granulomatous inflammatory reaction |

| Vagefi et al5 | Four women | Granulomatous inflammatory reaction |

| Nunes et al30 | 81-year-old, 63-year-old, and 30-year-old women | Trichiasis after 6–12 months of blepharopigmentation |

| Lee et al31 | 31-year-old and 50-year-old women | Extensive fanning after 8 months and 3 years |

| Peters et al17 | 81-year-old woman | Immediate extensive hyperpigmentation of the nasojugal fold and lower eyelid |

| Goldberg and Shorr32 | Three women | Eyelid necrosis 2 months after the procedure (one patient), extensive fanning (two patients) |

Lasers are effective for tattoo removal based on the principle of selective photothermolysis and, in the case of a Q-switched laser, by an additional photoacoustic effect. Choosing the right laser for the right tattoo color is of crucial importance. Treatments that occur too frequently increase the risk of scarring and ink retention.23

The Q-switched Nd:YAG laser at 1,064 nm is a very effective tool for removing black and white inks. The endpoint of laser treatment is defined by whitening of the skin with mild pinpoint bleeding.23 In the case of permanent makeup, a paradoxical darkening may occasionally be observed, which is due to a reduction of ferric oxide to ferrous oxide. Transient hyperpigmentation is not uncommon using Q-switched techniques.23 Sun protection is important in these cases to prevent long-lasting or permanent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The Nd:YAG laser penetrates deeply and carries the least risk of hypopigmentation.23 For other colors, other laser types can be employed such as ruby, alexandrite, or 532 nm, 585 nm, or 650 nm Nd:YAG.23,24

Conclusion

Permanent makeup by micropigmentation has become more popular among elderly women. In eyelash and eyebrow tattooing of elderly women, dermatochalasis seems to be a possible risk factor for extensive fanning. Other possible adverse effects are similar to those of decorative tattooing. Consumer protection demands for better education and information regarding the possible risks of such procedures. Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment is a useful tool to manage unwanted side effects like fanning.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Liu C, Keeling D, Hogg M. The unspoken truth: a phenomenological study of changes in women’s sense of self and the intimate relationship with cosmetics consumption. In: Belk RW, Askegaard S, Scott L, editors. Research in Consumer Behavior, Volume 14. London, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2012. pp. 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kligman AM, Graham JA. The psychology of appearance in the elderly. Dermatol Clin. 1986;4(3):501–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Cuyper C. Permanent makeup: indications and complications. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26(1):30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Straetemans M, Katz LM, Belson M. Adverse reactions after permanent-makeup procedures. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(26):2753. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc063122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vagefi MR, Dragan L, Hughes SM, Klippenstein KA, Seiff SR, Woog JJ. Adverse reactions to permanent eyeliner tattoo. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22(1):48–51. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000196713.94608.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wamer WG, Yin JJ. Photocytotoxicity in human dermal fibroblasts elicited by permanent makeup inks containing titanium dioxide. J Cosmet Sci. 2011;62(6):535–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao JC, Proia AD, Ely PH, Woodward JA. Late-onset melanophenic hypomelanosis as a complication of cosmetic eyeliner tattoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(3):e144–e146. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wollina U. Nodular skin reactions in eyebrow permanent makeup: two case reports and an infection by Mycobacterium haemophilum. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10(3):235–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giulieri S, Morisod B, Edney T, et al. Outbreak of Mycobacterium haemophilum infections after permanent makeup of the eyebrows. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(4):488–491. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong ML, Saunders JC, Roberts AE. Older women and cosmetic tattooing experiences. J Women Aging. 2009;21(3):186–197. doi: 10.1080/08952840903054807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehner K, Santarelli F, Vasold R, König B, Landthaler M, Bäumler W. Black tattoo inks are a source of problematic substances such as dibutyl phthalate. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;65(4):231–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Høgsberg T, Jacobsen NR, Clausen PA, Serup J. Black tattoo inks induce reactive oxygen species production correlating with aggregation of pigment nanoparticles and product brand but not with the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon content. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22(7):464–469. doi: 10.1111/exd.12178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan WR, Le Roux CM, Briggs CA. Variations in the lymphatic drainage pattern of the head and neck: further anatomic studies and clinical implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(2):611–620. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181fed511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aglianó M, Lorenzoni P, Volpi N, et al. Lymphatic vessels in human eyelids: an immunohistological study in dermatochalasis and chalazion. Lymphology. 2008;41(1):29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagi KS, Carlson JA, Wladis EJ. Histologic assessment of dermatochalasis: elastolysis and lymphostasis are fundamental and interrelated findings. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(6):1205–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendelson BC, Muzaffar AR, Adams WP., Jr Surgical anatomy of the midcheek and malar mounds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(3):885–896. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200209010-00026. discussion 897–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters NT, Conn H, Côté MA. Extensive lower eyelid pigment spread after blepharopigmentation. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;15(6):445–447. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199911000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tse DT, Folberg R, Moore K. Clinicopathologic correlate of a fresh eyelid pigment implantation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103(10):1515–1517. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050100091026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moshirfar M, Espandar L, Kurz C, Mamalis N. Inadvertent pigmentation of the limbus during cosmetic blepharopigmentation. Cornea. 2009;28(6):712–713. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318190737b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacob CI. Tattoo-associated dermatoses: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(10):962–965. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wollina U. Severe adverse events related to tattooing: a retrospective analysis of 11 years. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57(6):439–443. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.103062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kluger N, Koljonen V. Tattoos, inks, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(4):e161–e168. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wollina U, De Cuyper C. Tattoo Removal. In: Maibach HI, Gorouhi F, editors. Evidence Based Dermatology. 2nd ed. Shelton, CT: People’s Medical Publishing House – USA; 2011. pp. 557–571. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mao JC, DeJoseph LM. Latest innovations for tattoo and permanent makeup removal. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2012;20(2):125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2012.02.009. v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bee CR, Steele EA, White KP, Wilson DJ. Tattoo granuloma of the eyelid mimicking carcinoma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30(1):e15–e17. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31828ad7b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seol BR, Kwon JW, Ryang W. A case of meibomian gland dysfunction after cosmetic eyelid tattooing procedure. Journal of the Korean Ophthalmological Society. 2013;54(8):1309–1313. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudkin AK. Wake up with make-up: complication of cosmetic lid tattoo. Med J Aust. 2011;194(12):654. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De M, Marshak H, Uzcategui N, Chang E. Full-thickness eyelid penetration during cosmetic blepharopigmentation causing eye injury. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;7(1):35–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2008.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calzado L, Gamo R, Pinedo F, et al. Granulomatous dermatitis due to blepharopigmentation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(2):235–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nunes TP, Fernandes JBVD, Matayoshi S, da Mota Moura E. Trichiasis after blepharopigmentation – case report. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2004;67(1):165–167. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee IW, Ahn SK, Choi EH, Whang KK, Lee SH. Complications of eyelash and eyebrow tattooing: reports of 2 cases of pigment fanning. Cutis. 2001;68(1):53–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldberg RA, Shorr N. Complications of blepharopigmentation. Ophthalmic Surg. 1989;20(6):420–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]