Summary

Despite the recent development of effective therapeutic agents against multiple myeloma (MM), new therapeutic approaches, including immunotherapies, remain to be developed. Here we identified novel human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-A*0201 (HLAA2)-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes from a B cell specific molecule HLA-DOβ (DOB) as a potential target for MM. By DNA microarray analysis, the HLADOB expression in MM cells was significantly higher than that in normal plasma cells. Twenty-five peptides were predicted to bind to HLA-A2 from the amino acid sequence of HLA-DOB. When screened for the immunogenicity in HLA-A2-transgenic mice immunized with HLA-DOB cDNA, 4 peptides were substantially immunogenic. By mass spectrometry analysis of peptides eluted from HLA-A2-immunoprecipitates of MM cell lines, only two epitopes, HLA-DOB232-240 (FLLGLIFLL) and HLA-DOB185-193 (VMLEMTPEL), were confirmed for their physical presence on cell surface. When healthy donor blood was repeatedly stimulated in vitro with these two peptides and assessed by antigen-specific γ-interferon secretion, HLA-DOB232-240 was more immunogenic than HLA-DOB185-193. Additionally, the HLA-DOB232-240-specific CTLs, but not the HLA-DOB185-193-specific CTLs, displayed an major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted reactivity against MM cell lines expressing both HLA-A2 and HLA-DOB. Taken together, based on the physical presence on tumour cell surface and high immunogenicity, HLA-DOB232-240 might be useful for developing a novel immunotherapy against MM.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, HLA-DOβ, cytotoxic T lymphocyte, T cell epitope, DNA microarray

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) remains difficult to cure with currently available treatment options (Kumar 2010, Laubach, et al 2011, Palumbo, et al 2011). Therefore, new treatment strategies aiming at prolonging survival and improving quality of life remain to be developed. Immunotherapy might be a promising intervention to maintain a long-lasting control of minimal residual disease or to even eradicate disseminated malignant cells (Prabhala and Munshi 2007, Pratt, et al 2007). Currently, many immunotherapeutic approaches in development for MM employ whole tumour cell lysates or tumour-specific idiotypic proteins to generate patient-specific vaccines (Curti, et al 2007, Rosenblatt, et al 2011, Röllig, et al 2011, Yi, et al 2010, Zahradova, et al 2012). However, these approaches are very labour-intensive and expensive, making their general applicability difficult. Therefore, off-the-shelf immunotherapies, such as peptide-based vaccines, remain to be developed for treating patients more efficiently. Indeed, peptide-based vaccines would offer several advantages over individualized vaccines due to higher safety and lower cost, as well as easier immune monitoring to clarify the levels of specific immune responses sufficient to eradicate malignant cells in patients (Purcell, et al 2007).

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes for targeting MM cells have been identified from a variety of tumour antigens, such as MUC1, CYP1B1, PRAME, WT1, Sp17, HM1.24, XBP1, SOX2, CD138, and CS-1 (Bae, et al 2012, Bae, et al 2011, Brossart, et al 2001, Chiriva-Internati, et al 2002, Jalili, et al 2005, Kessler, et al 2001, Lotz, et al 2005, Maecker, et al 2005, Oka, et al 2008, Spisek, et al 2007). However, most of these epitopes have been identified from peptide candidates that were predicted to bind human leucocyte antigen (HLA) molecules, solely by their immunogenicity using in vitro cultured T cells. Therefore, it is questionable whether they are naturally processed and presented by malignant cells, even though they are immunogenic in vitro (Kessler and Melief 2007, Singh-Jasuja, et al 2004). Here we identified novel HLAA*0201 (HLA-A2)-restricted CTL epitopes, which were naturally processed and presented by MM cells, from a B cell-specific molecule HLA-DOβ (DOB) (Denzin, et al 2005, Naruse, et al 2002). In particular, given its strong immunogenicity for human T cells, one of the identified CTL epitopes, HLA-DOB232-240, could provide a promising immunotherapeutic approach for targeting MM.

Methods

Peptides and cell lines

HLA-DOB-derived peptides and a control peptide, modified Mart126-35 epitope (M26, ELAGIGILTV), were provided by Proimmune (Oxford, UK) or Mimotope (Melbourne, Australia) at purities of higher than 90%. An erythroleukaemia cell line K562, a TAP-deficient cell line T2, and MM cell lines, U266, IM-9, MC/CAR, and RPMI8226, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA), and OPM2 was kindly provided by Dr. Leif Bergsagel (Mayo Clinic, Tucson, AZ, USA). K562 cells stably transfected with HLA-A2 (K562-A2) was established as a target for immune assays (Anderson, et al 2011). Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 iu/ml penicillin (Mediatech, Herndon, VA). Expression of HLA-DOB and HLA-A2 in MM cell lines were examined by flow cytometry (FC500; Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL) with the CXP software (Beckman-Coulter) after staining with anti-HLA-DOB (B01P mouse polyclonal; Abnova, Taiwan) and anti-HLA-A2 (BB7.2 mouse monoclonal; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) antibodies (Abs), respectively.

DNA microarray analysis

The DNA microarray data (GeneChip® Human Exon 1.0 ST Array; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) of CD138+ myeloma cells from 170 newly diagnosed MM patients and plasma cells (PCs) from 6 normal donors were quality controlled and normalized with the aroma.affymetrix package. The gene expression level was estimated with a probe level model (PLM) (unpublished observations). The raw data for expression profiling and the CEL files can be found at the website Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE39754. The statistical significance of differences among the groups was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Prediction of HLA-A2-binding peptides derived from HLA-DOB

Based on our previous comprehensive analysis of prediction accuracy of various servers (Lin, et al 2008), three servers, IEDB ANN (http://tools.immuneepitope.org/analyze/html/mhc_binding.html), NetMHC ANN (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetMHC), and MHC-I Multiple Matrix (http://atom.research.microsoft.com/hlabinding/hlabinding.aspx), were employed to predict 9-mer HLA-A2 binding peptides, and two servers, IEDB ARB (http://tools.immuneepitope.org/analyze/html/mhc_binding.html) and MHC-I Multiple Matrix, were used to predict 10-mer HLA-A2 binding peptides.

HLA class I stabilization assay

The actual binding of predicted peptides to HLA-A2 molecules was evaluated by T2 cell surface HLA class I stabilization assay. Briefly, T2 cells were cultured for 18 h at 37°C in serum-free IMDM medium (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) in the presence of peptides (40 μg/ml). At 0, 3, 6 and 24 h after washing, the cells were stained with anti-HLA-A2 Ab (BB7.2), followed by analysis with flow cytometry. The binding capability of each peptide to HLA-A2 molecules was evaluated by the increase in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the HLA-A2 expression, as follows: MFI increase = (MFI with a given peptide – MFI without a peptide)/(MFI without a peptide). The modified Mart126-35 epitope (M26) was used as a positive control. Assays were performed in triplicate, and mean values were used for calculation.

Generation of antigen-specific T cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from HLA-A2+ healthy donors were obtained with written informed consent under the Institutional Review Board approval at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. PBMCs were purified using Ficoll-Paque density centrifugation (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), and HLA-A2 expression was confirmed by flow cytometry with anti-HLA-A2 Ab (BB7.2). Mature dendritic cells (DCs) were used to stimulate autologous CD8+ T cells, which were purified with anti-CD8 bead (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Mature DCs were generated from monocytes isolated from PBMCs, as previously described (Anderson, et al 2011). CD8+ T cells (2 x 106 cells/well in a 24-well plate) were first primed with autologous mature DCs pulsed with peptides (10 μg/ml) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% human AB serum (Cellgro, Herndon, VA), 2 mM glutamine (Cellgro), 10 mM HEPES (Cellgro), and 15 μg/ml gentamycin (Invitrogen) in the presence of 10 ng/ml of interleukin (IL)7 (Endogen Inc., Woburn, MA) on day 0 and 20 iu/ml of IL2 (Chiron Corp., Emeryville, CA) on days 1 and 4. Re-stimulation of T cells was performed with autologous mature DCs pulsed with the same peptides (2 μg/ml) every week. Antigen-specific T cells were enriched by sorting with PE-conjugated peptide/HLA-A2 tetramer (NIH Tetramer Facility; Emory University, Atlanta, GA) in combination with anti-PE Micro-Beads (Miltenyi Biotec), and then cloned by limiting dilution using irradiated feeder cells (allogeneic PBMCs and Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines) in the presence of 1% phytohaemagglutinin (Invitrogen) and 100 iu/ml IL2 (Chiron Corp). Antigen-specificity of the T cell clones was determined by γ-interferon (IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay and/or peptide/HLA-A2 tetramer staining.

Immune assays

To examine the cytotoxicity of T cells, europium release assay was performed, as previously described (Anderson, et al 2011). Specific europium release was measured by a multiplate reader (Victor3 multilabel counter model 1420; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). For blocking the HLA class I molecules, anti-HLA class I Ab (clone W6/32) or isotype control IgG2a Ab (10 μg/ml; both from eBioscience, San Diego, CA) were used. All experiments were performed in triplicate and mean values were used for calculation.

For IFN-γ ELISPOT assay with human T cells, the indicated numbers of T cells were cultured for 24 h at 37°C with the T2, K562-A2, or MM cells (5 × 104 cells/well) loaded without or with control or specific peptides (5 μ/ml) in 96-well ELISPOT plate (MultiScreen HTS; Millipore, Bedford, MA) coated with anti-human IFN-γ Ab (MABTECH, Cincinnati, OH). After washing, the spots were developed with biotinconjugated anti-human IFN-γ Ab (MABTECH), streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (MABTECH), and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate/nitro-blue tetrazolium (BCIP/NBT) substrate (Promega, Madison, WI), and then counted by ELISPOT reader (CTL Technologies, Cleveland, OH).

Results

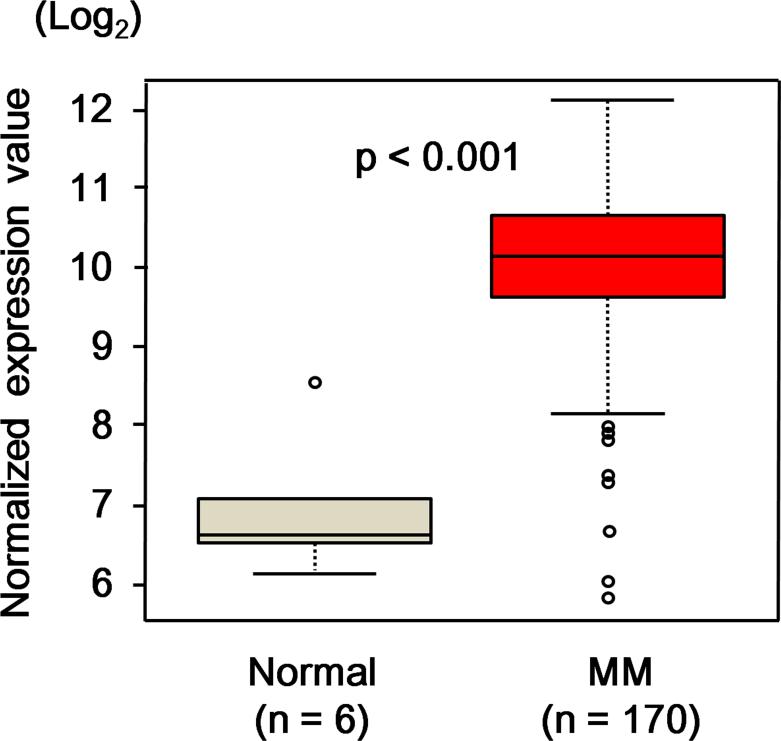

Identification of a potential target molecule for MM by DNA microarray analysis

In order to identify genes that were over-expressed in MM cells as potential targets for immunotherapy, we first identified 53 genes, whose expressions in CD138+ MM cells were more than 20 times higher than those in bone marrow PCs from normal donors by DNA microarray analysis in a smaller dataset (data not shown). Among them, HLA-DOB, which has been reported to be selectively expressed in B-lineage cells (Denzin, et al 2005, Naruse, et al 2002), was selected for further study to identify novel antigenic CTL epitopes. We further examined RNA expression levels in CD138+ cells from MM patients (n = 170) and bone marrow PCs from normal donors (n = 6) by the DNA microarray analysis, and observed that HLA-DOB levels were more than 2 standard deviations above the mean for normal bone marrow PCs in 155 of 170 MM samples (Fig 1). From the entire amino acid sequence of HLA-DOB, 25 peptides (9-mer or 10-mer) were predicted to bind to HLA-A2 with higher probability by the prediction servers (Table I).

Fig 1. HLA-DOB expression in MM cells.

Expression levels of HLA-DOB RNA were examined in CD138+ myeloma cells from newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) patients (n = 170) and bone marrow plasma cells from normal donors (n = 6) by DNA microarray analysis. The expression levels of HLA-DOB RNA were compared between MM patients and normal donors. The statistical significance of differences between the groups was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Table I.

List of the HLA-DOB-derived peptides.

| Peptide number | Position | Number of amino acids | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 232-240 | 9 | FLLGLIFLL |

| 2 | 56-64 | 9 | FIFNLEEYV |

| 3 | 185-193 | 9 | VMLEMTPEL |

| 4 | 52-60 | 9 | FVVRFIFNL |

| 5 | 233-241 | 9 | LLGLIFLLV |

| 6 | 228-236 | 9 | GIAAFLLGL |

| 7 | 235-243 | 9 | GLIFLLVGI |

| 8 | 11-19 | 9 | ALLVNLTRL |

| 9 | 71-79 | 9 | GMFVALTKL |

| 10 | 158-166 | 9 | FLNGQEERA |

| 11 | 199-207 | 9 | CLVDHSSLL |

| 12 | 232-241 | 10 | FLLGLIFLLV |

| 13 | 224-233 | 10 | KMLSGIAAFL |

| 14 | 184-193 | 10 | VVMLEMTPEL |

| 15 | 136-145 | 10 | HQHNLLHCSV |

| 16 | 220-229 | 10 | YSWRKMLSGI |

| 17 | 230-239 | 10 | AAFLLGLIFL |

| 18 | 175-184 | 10 | RNGDWTFQTV |

| 19 | 245-254 | 10 | IQLRAQKGYV |

| 20 | 203-212 | 10 | HSSLLSPVSV |

| 21 | 5-14 | 10 | WVPWVVALLV |

| 22 | 192-201 | 10 | ELGHVYTCLV |

| 23 | 92-101 | 10 | DLLERSRQAV |

| 24 | 228-237 | 10 | GIAAFLLGLI |

| 25 | 126-135 | 10 | TVYPERTPLL |

Screening of HLA-DOB-derived peptides for the immunogenicity in HLA-A2-transgenic AAD mice

We examined the immunogenicity of each of the HLA-DOB-derived peptides by using HLA-A2-transgenic mice, AAD. The peptide epitopes presented and recognized by mouse T cells in the context of the HLA-A2/H2-Dd class I molecules in these mice have been reported to be almost the same as those in HLA-A2+ humans (Mullins, et al 2001, Newberg, et al 1996, Peng, et al 2006). To identify immunogenic epitopes, AAD mice were immunized three times with a plasmid containing HLA-DOB cDNA for inducing antigen-specific immune responses. Two weeks after the last immunization, splenocytes were analysed ex vivo for IFN-γ production in response to each of the predicted peptides. As shown in Fig S1, DNA immunization successfully induced T cells specific to 4 of the 25 peptides; HLA-DOB232-240 (FLLGLIFLL), HLA-DOB185-193 (VMLEMTPEL), HLADOB224-233 (KMLSGIAAFL), and HLA-DOB184-193 (VVMLEMTPEL). As we used the DNA vaccination method for immunization, the identified peptides were most likely naturally processed and presented in complex with the HLA-A2/H2-Dd class I molecules in vivo in the AAD mice.

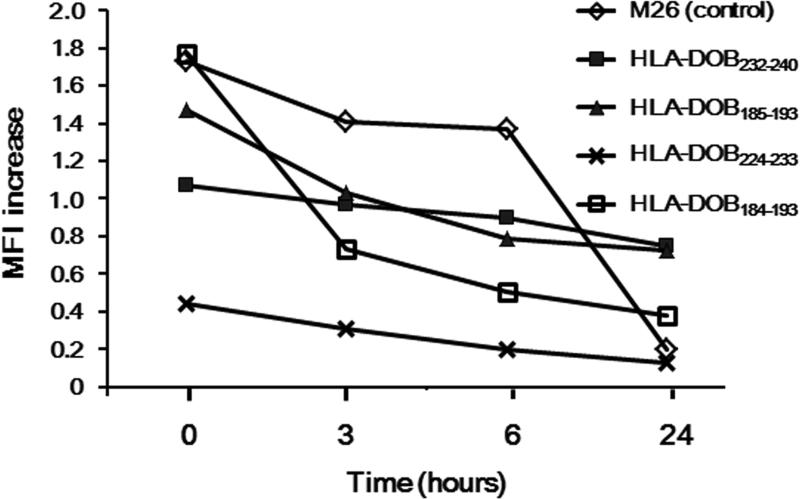

The binding of the identified peptides to the HLA-A2 molecule was further confirmed by the cell surface HLA class I stabilization assay with the HLA-A2-positive TAP-deficient lymphoma cell line T2. As illustrated in Fig 2, all of the 4 identified peptides showed substantial binding to the HLA-A2 molecule. The binding capability of HLA-DOB232-240, HLA-DOB185-193, and HLA-DOB184-193 to HLA-A2 was stronger than that of HLA-DOB224-233.

Fig 2. HLA-A2 binding capability of HLA-DOB-derived peptides.

Binding of the peptides, HLA-DOB232-240, HLA-DOB185-193, HLA-DOB224-233, and HLA DOB184-193, to the HLA-A2 molecule was confirmed by the cell surface HLA class-I stabilization assay. T2 cells were cultured for 18 h at 37°C in the presence of peptides (40 μg/ml). At 0, 3, 6 and 24 h after washing, the cells were stained with anti-HLA-A2 Ab (BB7.2), followed by analysis with flow cytometry. The binding capability of each peptide to HLA-A2 molecule was calculated by the increase in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of HLA-A2 expression: MFI increase = (MFI with a given peptide – MFI without a peptide)/(MFI without a peptide). The modified Mart126-35 epitope (M26) was used as a positive control. A representative experiment of three separate experiments is shown.

Physical identification of HLA-DOB232-240 and HLA-DOB185-193 on the cell surface of MM cell lines by mass-spectrometry (MS)

We next examined whether the peptides identified by the in vivo immunogenicity in the AAD mouse system were actually expressed in complex with the HLA-A2 molecules on cell surface of MM cells. Three MM cell lines, U266, IM-9, and MC/CAR, which were positive for both HLA-DOB and HLA-A2 (data not shown), were employed. HLA-A2-binding peptides were acid-released from the HLA-A2/peptide complexes, which were affinity-purified from these MM cell lines using the anti-HLA-A2 Ab BB7.2, and then analysed by nanospray ionization and MS3 ion fragmentation (Reinhold, et al 2010, Riemer, et al 2010). HLA-DOB185-193 could be easily identified by this analysis in the peptides recovered from all of these 3 cell lines. In addition, HLA-DOB232-240 was detected in IM-9 and MC/CAR cells, but not in U266 cells. Representative data of IM-9 cells are given in Fig S2 with detection evident by the high peak at the “0” offset on the X-axis. In contrast, the physical existence of other two peptides, HLA-DOB224-233 and HLA-DOB184-193, on MM cell surface was not confirmed by the nanospray ionization and MS3 ion fragmentation (data not shown).

Immunogenicity of HLA-DOB232-240 and HLA-DOB+185-193 in CD8 T cells from human peripheral blood

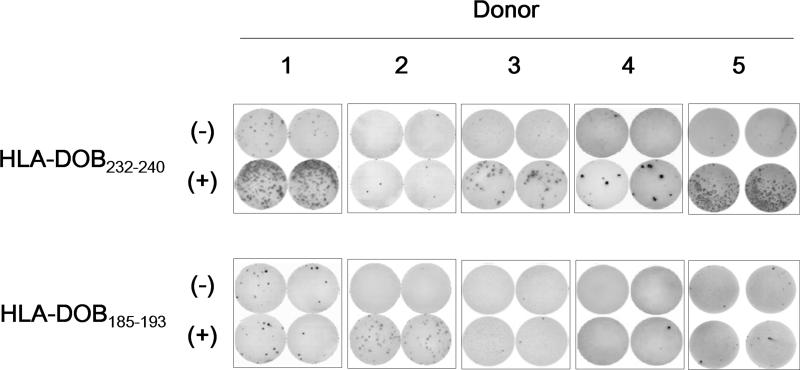

To determine the immunogenicity of the HLA-DOB232-240 and HLA-DOB185-193 peptides in humans, CD8+ T cells from 5 different HLA-A2+ healthy donors were repeatedly stimulated with autologous mature DCs pulsed with the synthetic peptides. After 4 rounds of in vitro stimulation, CD8+ T cell lines secreting IFN-γ in response to HLA-DOB232-240 or HLA-DOB185-193 could be established in 4 of 5 or 1 of 5 donors, respectively (Fig 3). This result suggested that HLA-DOB232-240 was more immunogenic than HLA-DOB185-193 in human CD8+ T cells.

Fig 3. Immunogenicity of HLA-DOB232-240 and HLA-DOB185-193 in CD8+ T cells from peripheral blood.

Immunogenicity of the HLA-DOB232-240 and HLA-DOB185-193 peptides was examined with peripheral blood from 5 different HLA-A2+ healthy donors. CD8+ T cells were first primed with autologous mature dendritic cells pulsed with synthetic peptides (10 μg/ml). After three more rounds of in vitro stimulation with the same peptides (2 μg/ml), T cells (5 × 103 cells/well) were examined for reactivity against T2 cells (5 × 104 cells/well) pulsed with 5 μg/ml of control M26 peptide (-) or specific peptide (+) by γ-interferon enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay. The cells were cultured in duplicate.

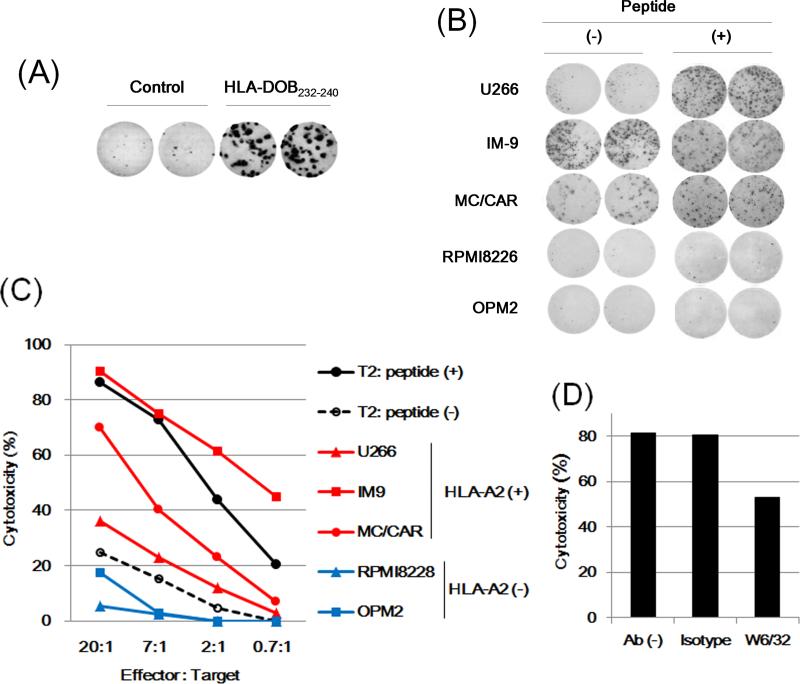

We further characterized these T cells specific to the HLA-DOB-derived peptides. We first established a T cell clone, 232-27, from a CTL line specific to HLA-DOB232-240 by limiting-dilution method. The clone 232-27 showed IFN-γ secretion in response to the HLA-DOB232-240 peptide in an antigen-specific manner (Fig 4A). Its clonality (> 95%) was also verified by the HLA-A2/HLA-DOB232-240 tetramer staining determined by flow cytometry (data not shown). The reactivity of the clone 232-27 was assessed against HLA-DOB+/HLA-A2+ MM cell lines, U266, IM-9, and MC/CAR, as well as HLADOB+/HLA-A2- lines, RPMI8226 and OPM2, as negative controls. As shown in Fig 4B, the clone 232-27 showed an apparent IFN-γ production in response to IM-9 and MC/CAR cells. This clone also produced less, but a still substantial amount of IFN-γ in response to U266, whereas it showed no response against HLA-DOB+/HLA-A2- MM cell lines. Of note, U266 cells pulsed with the synthetic HLA-DOB232-240 peptide clearly enhanced IFN-γ secretion from the clone 232-27, suggesting that the cell surface expression of HLA-A2/HLA-DOB232-240 in U266 cells may not be high enough to fully stimulate cytokine production from this T cell clone. Consistent with this finding, the cytotoxicity assay showed that cytotoxic activity of the clone 232-27 against IM-9 and MC/CAR cells were substantially higher than that against U266 cells (Fig 4C). The cytotoxicity was significantly inhibited by incubation with anti-HLA-class I Ab (clone W6/32), but not by an isotype control Ab, confirming that this response was major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-restricted (Fig 4D).

Fig 4. Functional characterization of an HLA-DOB232-240-specific T cell clone.

(A) An HLA-DOB232-240-specific T cell clone 232-27 (2 × 102 cells/well) was stimulated with T2 cells (5 × 104 cells/well) pre-treated for 2 h with the control (M26) or specific (HLA-DOB232-240) peptide (5 μg/ml), and γ-interferon (IFN-γ secretion was examined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay in duplicate. (B) The T cell clone 232-27 (1 × 103 cells/well) was stimulated with the HLA-DOB+/HLA-A2+ MM cell lines, U266, IM-9 and MC/CAR, or the HLA-DOB+/HLA-A2- lines, RPMI8226 and OPM2, (1 × 104 cells/well) pretreated for 2 h with or without the specific peptide (HLA-DOB232-240, 5 μg/ml). IFN-γ secretion was examined by ELISPOT assay in duplicate. (C) The clone 232-27 was examined for cytotoxicity against target cells (5 × 103 cells/well), including T2 cells pretreated for 2 h with 5 μg/ml of the control M26 peptide (-) or specific peptide (+), U266, IM-9, MC/CAR, RPMI8226 or OPM2, at the indicated effector/target ratios. The specific lysis was calculated as follows: specific lysis (%) = [(test release– spontaneous release) / (maximal release - spontaneous release)] × 100. (D) The cytotoxicity against IM-9 cells was examined in the presence or absence of anti-HLA class I (clone W6/32) or isotype control IgG2a Ab (10 μg/ml). A representative experiment of three separate experiments is shown.

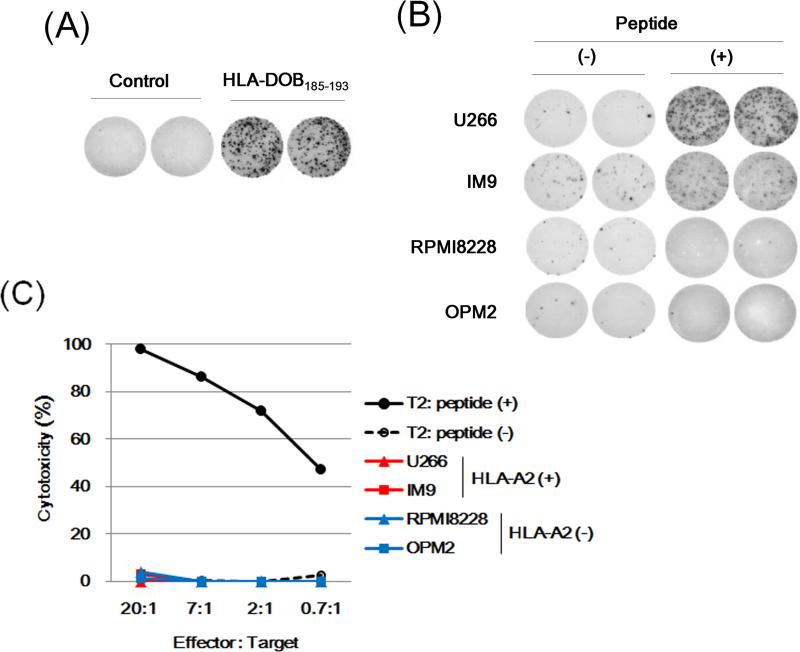

We also established antigen-specific T cell clones from an HLA-DOB185-193- specific CTL line by the limiting dilution method. As shown in Fig 5A, T cell clone 185-275 showed IFN-γ secretion in response to the synthetic HLA-DOB185-193 peptide. However, this clone showed a marginal reactivity against IM-9 cells, but almost no responses against U266 or HLA-DOB+/HLA-A2- lines, as determined by IFN-γ ELISPOT (Fig 5B). In addition, it showed no cytotoxicity against HLA-DOB+/HLA-A2+ MM cell lines, IM-9 or U266 (Fig 5C), although the cell surface display of HLA-DOB185-193 peptide on these MM cells was confirmed by MS analysis (Fig S2). Given that the clone 185-275 revealed a clear reactivity against IM-9 and U266 cells after treatment with the synthetic HLA-DOB185-193 peptide (Fig 5B), the avidity of T cell receptor (TCR) of this clone might be too low to respond to the copy number of naturally processed peptides arrayed on these MM cell lines, therefore requiring exogenous peptide addition. Although we established 5 other different HLA-DOB185-193-specific T cell clones, they showed similar results (data not shown).

Fig 5. Functional characterization of an HLA-DOB185-193-specific T cell clone.

(A) An HLA-DOB185-193-specific T cell clone 185-275 (1 × 103 cells/well) was stimulated with K562/HLA-A2 cells (5 × 104 cells/well) pretreated for 2 h with the control (M26) or specific (HLA-DOB185-193) peptide (5 μg/ml), and γ-interferon (IFN-γ secretion was examined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay in duplicate. (B) The T cell clone 185-275 (1 × 103 cells/well) was stimulated with U266, IM-9, RPMI8226 or OPM2 (1 × 104 cells/well), pretreated for 2 h with or without the specific peptide (HLA-DOB185-193, 5 μg/ml). IFN-γ secretion was examined by ELISPOT assay in duplicate. (C) The clone 185-275 was examined for cytotoxicity against target cells (5 × 103 cells/well), including T2 cells pretreated for 2 h with 5 μg/ml of the control M26 peptide (-) or specific peptide (+), U266, IM-9, RPMI8226 or OPM2, at the indicated effector/target ratios. The specific lysis was calculated. A representative experiment of three separate experiments is shown.

Discussion

Despite the development of novel therapeutic agents against MM, this disease is still difficult to cure with currently available treatment options (Kumar 2010, Laubach, et al 2011, Palumbo, et al 2011). In the current study, we identified two HLA-A2-restricted CTL epitopes, HLA-DOB232-240 and HLA-DOB185-193, which were naturally processed and presented on MM cell surface. In particular, the HLA-DOB232-240 epitope was highly immunogenic in human CD8+ T cells, suggesting that this epitope might be useful for immunotherapies against MM patients.

Based on gene expression analysis by the DNA microarray, we identified 53 potential MM-associated molecules, which showed >20-fold expression in MM cells compared to bone marrow PCs from normal donors. Among these proteins over-expressed in MM cells, HLA-DOB, a MHC class II-related molecule, was selected for further analysis to identify antigenic CTL epitopes, because this molecule was reported to be exclusively expressed in B-lineage cells and a subset of thymic medullary epithelium (Denzin, et al 2005). In addition, the HLA-DOB gene has a limited number of allelic variants in contrast to other MHC class II-related molecules (Naruse, et al 2002). Furthermore, HLA-DO, which is composed of HLA-DOαand HLA-DOB, has been shown to impair MHC class II presentation through inhibition of HLA-DM in B cells (Denzin, et al 2005). Thus, even if HLA-DOB expression is down-regulated by the immune escape mechanism after targeting this molecule, the skewed balance between intracellular HLA-DM and HLA-DO expression would ultimately induce up-regulation of MHC class II-restricted presentation of tumour antigens, which might lead to an enhanced anti-tumour immunity (Chamuleau, et al 2006). In view of these properties of HLA-DOB, we considered that this molecule might be a good target for immunotherapy against MM. Of note, other B cell-specific molecules, such as CD19 and CD20, have also been reported to be appropriate targets for treating B cell malignancies (Maloney, et al 1997, Porter, et al 2011).

The identification method of appropriate CTL epitopes for cancer immunotherapy remains controversial (Kessler and Melief 2007, Singh-Jasuja, et al 2004). Currently, many CTL epitopes have been identified from HLA-binding peptide candidates solely by examining indirect immunological surrogates (killing, proliferation, cytokine production, etc.) in vitro with cultured T cells. However, it is questionable whether the CTL epitopes identified by this approach are actually ‘real’ antigens that are naturally processed and presented on tumour cell surface, even though they are immunogenic in vitro (Kessler and Melief 2007, Singh-Jasuja, et al 2004). Therefore, although a large number of tumour antigens and epitopes have been already described (Bae, et al 2011, Brossart, et al 2001, Chiriva-Internati, et al 2002, Jalili, et al 2005, Kessler, et al 2001, Lotz, et al 2005, Maecker, et al 2005, Oka, et al 2008, Spisek, et al 2007), it may be possible that many of them cannot direct the host immune system toward malignant cells because they are not present on the tumour cell surface. Hence, in the current study, we employed more reliable approaches to identify ‘real’ antigenic epitopes from HLA-DOB. The HLA-A2 transgenic AAD mice that were vaccinated in vivo with HLA-DOB DNA showed substantial immune responses to 4 of the 25 predicted HLA-A2-binding epitopes, suggesting that these epitopes may be naturally processed and presented in vivo in AAD mice. In addition, two of them were physically detected on the cell surface by MS analysis of peptide pools extracted from the HLA-A2/peptide complexes on MM cells. The reason why the remaining two epitopes that were identified in AAD mice were not verified by the MS analysis might be due to a difference of the machinery in processing and/or presentation of endogenous proteins between mice and humans, as previously reported (Street, et al 2002). Alternatively, in principle, it might be explained by insufficient sensitivity of detection using the MS method that we employed. The latter appears less likely given the documented detection threshold demonstrated by other peptides assessed with this Poisson detection approach (Reinhold, et al 2010, Riemer, et al 2010).

In order to induce effective anti-tumour immune responses, tumour antigens should be sufficiently immunogenic to stimulate antigen-specific T-cells well. When CD8+ T cells from healthy HLA-A2+ donors were stimulated with the antigen peptide-pulsed autologous DCs, T cell lines specific to the HLA-DOB232-240 epitope were easily generated in 4 of 5 donors. In addition, the HLA-DOB232-240-specific T cell lines/clones demonstrated antigen-specific reactivity against HLA-A2+, but not HLA-A2-, MM cell lines. Notably, the reactivity of the HLA-DOB232-240-specific T cell clones against IM-9 and MC/CAR cells were substantially higher than that against U266 cells, although U266 cells pulsed with the synthetic HLA-DOB232-240 peptide showed clearly enhanced reactivity. This result was consistent with the finding that HLA-DOB232-240 was detected only in IM-9 and MC/CAR cells, but not in U266 cells. These results suggest that the cell surface expression of HLA-A2/HLA-DOB232-240 in U266 cells may not be high enough to fully stimulate antigen-specific T cell clone. Since the expression levels of HLA-DOB protein determined by flow cytometric analysis were similar among the HLA-A2+ MM cell lines, IM-9, MC/CAR, and U266 (data not shown), the difference in cell surface expression of HLA-A2/HLA-DOB232-240 may be explained by the different efficiency of peptide processing of HLA-DOB232-240 among these MM cell lines tested. To further confirm the suitability of this epitope as a therapeutic target, its expression on MM cells derived from patients remains to be examined.

In contrast, the HLA-DOB185-193 epitope seemed to be less immunogenic, as HLA-DOB185-193-specific T cells could be generated in only one of 5 different normal donors after repeated stimulation with the antigen peptide-pulsed autologous DCs. In addition, the established HLA-DOB185-193-specific T cell line/clones did not show apparent cytotoxic reactivity against the tumour cell lines examined, possibly due to low avidity of their TCR. Although not shown, we tried several other methods for stimulating CD8+ T cells by using different types of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as CD40L-activated autologous B cells and K562-based artificial APCs (Anderson, et al 2011, Schultze, et al 1997). Notably, these other APC systems also successfully generated T cells specific to HLA-DOB232-2403, but not to HLA-DOB185-193. Although not proved, the lower immunogenicity of the HLA-DOB185-193 epitope might be explained by deletion of high-avidity T cells due to central and/or peripheral tolerance.

In conclusion, we identified two novel HLA-A2-restricted, HLA-DOB-derived epitopes, HLA-DOB232-240 and HLA-DOB185-193, which were naturally processed and presented on MM cells. In particular, HLA-DOB232-240 could be promising as an antigenic epitope to target MM cells due to its stronger immunogenicity. Future studies will be required to investigate the clinical utility of the identified epitopes by using blood samples from MM patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Drs. Pedro A. Reche, Honghuang Lin. Mei Su, and Derin B Keskin (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) and Dr Herve Avet-Loiseau (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Nantes, France) for their technical help and helpful discussion. This study was supported by the DFCI Cancer Vaccine Center funding and a grant from the International Myeloma Foundation Japan (Aki Horinouchi Research Grant).

Footnotes

Author contributions

Y.J.K. and T.S. designed and performed research, analysed data, and wrote the paper; W.Z., W.S., B.R., J.C., V.B., and S.M. designed and performed research and analysed data; T.Y., A.M., and C.L. analysed data; K.C.A., N.M. and E.L.R designed the research, and critically evaluated and edited the paper.

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests.

References

- Anderson KS, Zeng W, Sasada T, Choi J, Riemer AB, Su M, Drakoulakos D, Kang YJ, Brusic V, Wu C, Reinherz EL. Impaired tumor antigen processing by immunoproteasome-expressing CD40-activated B cells and dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:857–867. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-0995-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae J, Tai YT, Anderson KC, Munshi NC. Novel epitope evoking CD138 antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes targeting multiple myeloma and other plasma cell disorders. Br J Haematol. 2011;155:349–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08850.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae J, Song W, Smith R, Daley J, Tai YT, Anderson KC, Munshi NC. A novel immunogenic CS1-specific peptide inducing antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes targeting multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2012;157:687–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brossart P, Schneider A, Dill P, Schammann T, Grünebach F, Wirths S, Kanz L, Bühring HJ, Brugger W. The epithelial tumor antigen MUC1 is expressed in hematological malignancies and is recognized by MUC1-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6846–6850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamuleau ME, Ossenkoppele GJ, van de Loosdrecht AA. MHC class II molecules in tumour immunology: prognostic marker and target for immune modulation. Immunobiology. 2006;211:619–625. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiriva-Internati M, Wang Z, Salati E, Bumm K, Barlogie B, Lim SH. Sperm protein 17 (Sp17) is a suitable target for immunotherapy of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2002;100:961–965. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curti A, Tosi P, Comoli P, Terragna C, Ferri E, Cellini C, Massaia M, D'Addio A, Giudice V, Di Bello C, Cavo M, Conte R, Gugliotta G, Baccarani M, Lemoli RM. Phase I/II clinical trial of sequential subcutaneous and intravenous delivery of dendritic cell vaccination for refractory multiple myeloma using patient-specific tumour idiotype protein or idiotype (VDJ)-derived class I-restricted peptides. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:415–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin LK, Fallas JL, Prendes M, Yi W. Right place, right time, right peptide: DO keeps DM focused. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:279–292. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalili A, Ozaki S, Hara T, Shibata H, Hashimoto T, Abe M, Nishioka Y, Matsumoto T. Induction of HM1.24 peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by using peripheral-blood stem-cell harvests in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2005;106:3538–3545. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler JH, Melief CJ. Identification of T-cell epitopes for cancer immunotherapy. Leukemia. 2007;21:1859–1874. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler JH, Beekman NJ, Bres-Vloemans SA, Verdijk P, van Veelen PA, Kloosterman-Joosten AM, Vissers DC, ten Bosch GJ, Kester MG, Sijts A, Wouter Drijfhout J, Ossendorp F, Offringa R, Melief CJ. Efficient identification of novel HLA-A(*)0201-presented cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes in the widely expressed tumor antigen PRAME by proteasome-mediated digestion analysis. J Exp Med. 2001;193:73–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. Multiple myeloma - current issues and controversies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(Suppl 2):S3–11. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(10)70006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laubach J, Richardson P, Anderson K. Multiple myeloma. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:249–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-070209-175325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HH, Ray S, Tongchusak S, Reinherz EL, Brusic V. Evaluation of MHC class I peptide binding prediction servers: applications for vaccine research. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz C, Mutallib SA, Oehlrich N, Liewer U, Ferreira EA, Moos M, Hundemer M, Schneider S, Strand S, Huber C, Goldschmidt H, Theobald M. Targeting positive regulatory domain I-binding factor 1 and X box-binding protein 1 transcription factors by multiple myeloma-reactive CTL. J Immunol. 2005;175:1301–1309. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maecker B, von Bergwelt-Baildon MS, Anderson KS, Vonderheide RH, Anderson KC, Nadler LM, Schultze JL. Rare naturally occurring immune responses to three epitopes from the widely expressed tumour antigens hTERT and CYP1B1 in multiple myeloma patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;141:558–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney DG, Grillo-López AJ, White CA, Bodkin D, Schilder RJ, Neidhart JA, Janakiraman N, Foon KA, Liles TM, Dallaire BK, Wey K, Royston I, Davis T, Levy R. IDEC-C2B8 (Rituximab) anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in patients with relapsed low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood. 1997;90:2188–2195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins DW, Bullock TN, Colella TA, Robila VV, Engelhard VH. Immune responses to the HLA-A*0201-restricted epitopes of tyrosinase and glycoprotein 100 enable control of melanoma outgrowth in HLA-A*0201-transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:4853–4860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naruse TK, Kawata H, Inoko H, Isshiki G, Yamano K, Hino M, Tatsumi N. The HLA-DOB gene displays limited polymorphism with only one amino acid substitution. Tissue Antigens. 2002;59:512–519. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.590608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newberg MH, Smith DH, Haertel SB, Vining DR, Lacy E, Engelhard VH. Importance of MHC class 1 alpha2 and alpha3 domains in the recognition of self and non-self MHC molecules. J Immunol. 1996;156:2473–2480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Oji Y, Kawase I, Sugiyama H. WT1 peptide vaccine for the treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo A, Attal M, Roussel M. Shifts in the therapeutic paradigm for patients newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma: maintenance therapy and overall survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1253–1263. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S, Trimble C, He L, Tsai YC, Lin CT, Boyd DA, Pardoll D, Hung CF, Wu TC. Characterization of HLA-A2-restricted HPV-16 E7-specific CD8(+) T-cell immune responses induced by DNA vaccines in HLA-A2 transgenic mice. Gene Ther. 2006;13:67–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter DL, Levine BL, Kalos M, Bagg A, June CH. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhala RH, Munshi NC. Immune therapies. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2007;21:1217–1230. x–xi. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt G, Goodyear O, Moss P. Immunodeficiency and immunotherapy in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:563–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell AW, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J. More than one reason to rethink the use of peptides in vaccine design. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:404–414. doi: 10.1038/nrd2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold B, Keskin DB, Reinherz EL. Molecular Detection of Targeted Major Histocompatibility Complex I-Bound Peptides Using a Probabilistic Measure and Nanospray MS(3) on a Hybrid Quadrupole-Linear Ion Trap. Anal Chem. 2010;82:9090–9099. doi: 10.1021/ac102387t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemer AB, Keskin DB, Zhang G, Handley M, Anderson KS, Brusic V, Reinhold B, Reinherz EL. A conserved E7-derived cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope expressed on human papillomavirus 16-transformed HLAA2+ epithelial cancers. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:29608–29622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.126722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt J, Vasir B, Uhl L, Blotta S, Macnamara C, Somaiya P, Wu Z, Joyce R, Levine JD, Dombagoda D, Yuan YE, Francoeur K, Fitzgerald D, Richardson P, Weller E, Anderson K, Kufe D, Munshi N, Avigan D. Vaccination with dendritic cell/tumor fusion cells results in cellular and humoral antitumor immune responses in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2011;117:393–402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röllig C, Schmidt C, Bornhäuser M, Ehninger G, Schmitz M, Auffermann-Gretzinger S. Induction of cellular immune responses in patients with stage-I multiple myeloma after vaccination with autologous idiotype-pulsed dendritic cells. J Immunother. 2011;34:100–106. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181facf48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultze JL, Michalak S, Seamon MJ, Dranoff G, Jung K, Daley J, Delgado JC, Gribben JG, Nadler LM. CD40-activated human B cells: an alternative source of highly efficient antigen presenting cells to generate autologous antigen-specific T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2757–2765. doi: 10.1172/JCI119822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Jasuja H, Emmerich NP, Rammensee HG. The Tübingen approach: identification, selection, and validation of tumor-associated HLA peptides for cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:187–195. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0480-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spisek R, Kukreja A, Chen LC, Matthews P, Mazumder A, Vesole D, Jagannath S, Zebroski HA, Simpson AJ, Ritter G, Durie B, Crowley J, Shaughnessy JD, Scanlan MJ, Gure AO, Barlogie B, Dhodapkar MV. Frequent and specific immunity to the embryonal stem cell-associated antigen SOX2 in patients with monoclonal gammopathy. J Exp Med. 2007;204:831–840. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street MD, Doan T, Herd KA, Tindle RW. Limitations of HLA-transgenic mice in presentation of HLA-restricted cytotoxic T-cell epitopes from endogenously processed human papillomavirus type 16 E7 protein. Immunology. 2002;106:526–536. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Q, Szmania S, Freeman J, Qian J, Rosen NA, Viswamitra S, Cottler-Fox M, Barlogie B, Tricot G, van Rhee F. Optimizing dendritic cell-based immunotherapy in multiple myeloma: intranodal injections of idiotype-pulsed CD40 ligand-matured vaccines led to induction of type-1 and cytotoxic T-cell immune responses in patients. Br J Haematol. 2010;150:554–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08286.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahradova L, Mollova K, Ocadlikova D, Kovarova L, Adam Z, Krejci M, Pour L, Krivanova A, Sandecka V, Hajek R. Efficacy and safety of Id-protein-loaded dendritic cell vaccine in patients with multiple myeloma--phase II study results. Neoplasma. 2012;59:440–449. doi: 10.4149/neo_2012_057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.