Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease associated with the development of dementia. It has been established that the pathological hallmarks of neurofibrillary tau protein tangles and senile β-amyloid protein plaques lead to degeneration of neurons via inflammatory pathways. The progressive death of neurons, primarily cholinergic, results in a gradual and fatal decline of cognitive abilities and memory. By targeting these pathological hallmarks and their associated pathways, AD drug therapy can potentially attenuate the disease state. In this review article, we focus on newly proposed and experimental AD drug treatment. We discuss three characteristic areas of AD treatment: prevention of neurotoxic β-amyloid protein plaque formation, stability of neuronal tau proteins, and increase in neuronal growth and function. The primary drug therapy methods and patents discussed include the use of neurotrophic factors and targeting of the amyloid precursor protein cleavage pathway as prevention of β-amyloid formation and tau aggregation.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, β-amyloid, neurotrophic factors, colivelin

1. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease associated with progressive development of dementia. Although the mechanism of AD development is not well understood, age is the primary risk factor [1]. About 95% of cases are considered simply sporadic, while the remaining 5% are attributed to inherited familial genetic mutations [2]. The familial genetic mutations linked to AD involve the cleavage of a protein known as amyloid precursor protein (APP) [3]. AD is associated with two major pathological hallmarks, neurofibrillary tau protein tangles and a product of APP cleavage known as senile plaques, both of which lead to the degeneration of neurons via an inflammatory pathway. The aggregation of these protein plaques in the brain signals an immune response involving nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species, prostaglandins, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [4, 5]. Whether the inflammation is the root of the disease or a secondary result is unknown [2]. This inflammation leads to the death of neurons, primarily cholinergic, and results in a gradual and debilitating loss of cognitive function and memory [6]. Current clinical drug treatments for AD, including acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, antioxidants, and glutamate antagonists, increase neuronal activity but fail to address the pathological hallmarks that appear to provoke the neurological damage [7-9].

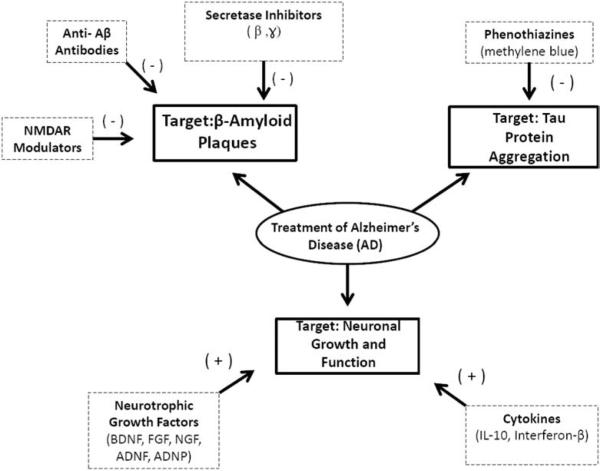

We focused this review on therapeutic drugs that target the pathological hallmarks of AD directly, in an attempt to not only slow the progression of AD but also to potentially reverse neurodegeneration. Newly proposed and experimental AD treatment drugs focus primarily on three characteristic areas of AD development: prevention of neurotoxic β -amyloid protein plaque formation, stability of neuronal tau proteins, and increase in neuronal growth and function. We summarize the potential drugs targeting β -amyloid protein plaque formation, tau protein aggregation, and loss of neuronal growth and function for the treatment of AD (Fig. 1). These drug targets are aimed to slow or attenuate the progression of AD. The purpose of this review article is to explore potential drug therapy targets in inflammatory AD pathways; and to discuss recent therapeutic compounds and neurotrophic factors targeting these pathways for the treatment of AD.

Fig. (1).

Diagram shows three primary drug targets in AD pharmacotherapy, β-amyloid protein plaques, neuronal tau protein aggregates, and loss of neuronal growth and function. The β-amyloid protein plaques are targeted specifically by β-, and -secretases, which lead to prevent the improper cleavage of APP and the subsequent formation of plaques. The β-amyloid protein plaques are also directly targeted by anti-β-amyloid antibodies, which bind to preexisting β-amyloid fragments and prevent their neurotoxic aggregation. NMDAR modulators prevent the activation of β -secretases, thus preventing formation of amyloid aggregates. The second AD drug target is neuronal tau aggregation, which is corrected through the use of phenothiazine drugs, primarily methylene blue. Furthermore, phenothiazines block tau proteins at their high affinity binding sites, which prevents their aggregation. The third direct AD drug target is the loss of neuronal growth and function. Several neurotrophic growth factors, including BDNF, FGF, NGF, ADNF peptide, and ADNP peptide have been shown to both reverse preexisting neurodegeneration and stimulate new neuronal growth. Cytokines have also been shown to reduce neurodegeneration via anti-inflammatory pathways and neuroprotective abilities.

2. PROTEOLYTIC PROCESSING OF β-AMYLOID PEPTIDES IN AD

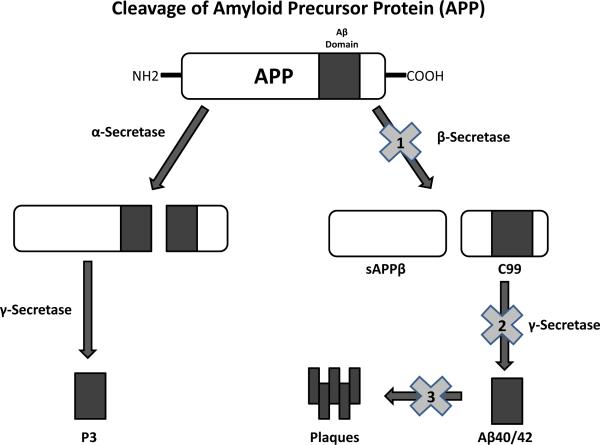

The primary hallmark of AD, and thus a major focus of drug design, is the neuronal amyloid protein aggregation known as the β -amyloid (Aβ). To fully understand current AD anti-amyloid drug designs, it is important to understand the process of Aβ formation (Fig. 2). The two most prevalent β-amyloid peptides found aggregated in the brains of AD patients are Aβ40 and Aβ42 [10]. Both are variants of the Aβ4 polypeptide and contain 40 and 42 amino acids, respectively. Aβ4 (both 40 and 42) is derived from the proteolysis of amyloid peptide β -amyloid protein plaque (βAPP), a large type-I membrane protein that has a relatively unknown function [11] (Fig. 2). Cleavage is achieved first via one of two primary enzymes, α-secretase or β-secretase, followed by a secondary cleavage by an enzyme known as -secretase [12] (Fig. 2). Processing via the enzyme known as α-secretase cleaves the APP within a central region known as γ -secretase, known as p3 [11]. However, processing of APP by an enzyme known as β-secretase, which cleaves outside the designated aβ domain, leads to the formation of the aforementioned amyloid-prone Aβ40 and Aβ42 [12]. APP is first cleaved by β -secretase at the amino terminus into two parts, sAPPβ and C99, and then the c99 half is cleaved by -secretase into one of several amyloid-prone Aβ4 forms [12]. Genetic mutations in the regions that encode for formation γ and cleavage of these peptides are highly associated with the early development of AD and therefore are regarded as a critical step in the pathogenesis of AD [11]. It is on chromosome 21 specifically that βAPP processing sites are encoded. Interestingly, Down's syndrome (DS) patients, who have an extra chromosome 21, express early onset AD symptoms [13]. The extra chromosome 21 means an extra copy of the APP gene, and therefore marked increases in Aβ42 [13]. Mutations of the -secretase complex have also been associated with the development of early onset Specifically, mutations in the γ AD. presenilin 1 and presenilin 2 components of this complex are suggested to be a major cause of early onset AD. Furthermore, presenilin 1 and 2 are catalytic aspartyl protease subunits within the -secretase and their mutation results in progression of the AD amyloid pathway via increased Aβ40/42 production from γ APP cleavage [14].

Fig. (2).

Diagram shows the enzymatic pathway of amyloid precursor protein (APP) cleavage. Cleavage of APP is achieved first via one of two primary enzymes, α-secretase or β-secretase. Cleavage by α-secretase within the Aβ domain initiates the non-amyloid forming pathway. The product of the α -secretase reaction undergoes secondary cleavage via the enzyme γ-secretase, resulting in the water soluble, non amyloid forming product known as p3. If the primary cleavage of APP is performed by β-secretase, however, the amyloid forming pathway is initiated. The β-secretase cleavage site is outside the Aβ domain and results in the formation of two protein products, secreted amyloid precursor protein (sAPPβ) and c99. The protein product c99 undergoes secondary cleavage via -secretase and produces one of several amyloid-prone Aβ4 protein forms, most commonly 42 to 44 residues long. These Aβ4 forms subsequently cross-link, creating the characteristic neurotoxic Aβ plaques. The β-amyloid end product can be prevented at three potential sites. The first is by inhibition of β-secretase enzyme (“1”) by drugs such as the terminated LY2811376. The second is inhibition of the enzyme -secretase (“2”) by drugs such as the terminated Semagacestat and Tarenfurbil. The third is prevention of β-amyloid fragment aggregation by Aβ-antibodies (“3”) such as Bapineuzumab and Solanezumab.

Ischemic episodes may also increase Aβ formation [15]. A recent study verified the association between brain ischemia and β- and -secretase upregulation [15]. Ischemic oxidative stress γ- was indicated to increase β- and γ-secretase regulation, thereby directly increasing β-amyloid levels. The study also indicates that increased γ-secretase activity enhances β-secretase upregulation and function. This process is mediated by the increased presence of β -amyloid and therefore can be considered a positive feedback loop [15].

These βAPP processing sites are often the consequences of genetic mutations, which result in improper cleavage [16]. If the genetic mutations are located next to the Aβ cleavage domain, those are known as β -secretase mutations [16]. Mutations occurring within the actual Aβ cleavage domain are known as α -secretase mutations [16]. Both α and β mutations appear to enhance the pathogenesis of AD [11]. Mutations that enhance β -secretase directly enhance the amyloid-forming pathway, as β secretase products are cleaved by γ-secretase, an imprecise enzyme that may result in the aggregate-prone Aβ40 and Aβ42 [17]. Mutations of the α-secretase increase the levels of available APP substrate accessible to the amyloid forming β-secretase, thereby indirectly increasing amyloid production [11]. Examples include a mutation at amino acids 670/671 of APP, known as “the Swedish” mutation, which exhibits an increased rate of β-secretase cleavage as well as a mutation known as the “arctic mutation” , further discussed here [18].

3. NEUROTROPHIC FACTORS IN AD

Prevention of cell death has been the main focus for the treatment of AD in animal models as well as in humans. Most efforts are focused in the use of neurotrophic factors to protect cholinergic neurons and, in turn, maintain their normal function. A previous study has shown that a deficit of exogenous supply of trophic factors may be linked to neurodegeneration of cholinergic neurons [19]. We discuss here several types of neurotrophic factors that might be candidates for AD therapy.

3.1. Nerve Growth Factor in AD

Neurotrophic factors in AD are tested to ameliorate cholinergic functions [20]. Among these neurotrophic factors, nerve growth factor (NGF) was found to have positive restorative effects in AD. Studies conducted in aged rats demonstrated that NGF reversed age-associated declines in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons and supported recovery from deficiencies in spatial memory [21]. The ability of NGF to prevent degeneration of cholinergic neurons is also demonstrated in primates [19, 22, 23]. NGF is considered to be effective for the survival of cholinergic neurons that are affected in AD (Reviewed by [24]).

Although the mechanism through which NGF acts is unknown, studies have shown that NGF stimulates protein kinase c-coupled M1/M3 muscarinic receptors. This can lead to an increase of the non-amyloidogenic secretory pathway of amyloid precursor protein (APP) signaling [reviewed by [25]]. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective actions might be induced by the cleavage of the APP by the α-secretase within the β-amyloid sequence, which generates non-amyloidogenic C-terminal APP fragments and soluble APPs alpha, a concept that is explored in greater detail within following sections. Therapeutic actions may be focused on stimulation of cholinergic function with increases in non-amyloidogenic APP without elevating the expression of APP.

3.2. Fibroblast Growth Factor in AD

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) is involved in neuroprotection of selective neuronal populations against neurotoxic effects leading to AD [26, 27]. FGF possesses wide mitogenic and cell survival activities and is involved in diverse biological effects [reviewed by [28]]. An in vitro study has shown that FGF protected cultured hippocampal neurons against β-amyloid peptide toxicity [29]. It is noteworthy that FGF interacts with β -amyloid peptide and induces neuroprotection in the AD model [30, 31]. The neuroprotective mechanism of FGF may occur at the level of synapses; the loss of synapses is one of the characteristics of AD, which is promoted by β -amyloid peptide [32]. Furthermore, it is postulated that polymorphism in the FGF gene increases the risk of AD in patients suffering from this disease [33]. Since most of these studies have investigated the protective effects of FGF in the in vitro AD model, it is possibly warranted to explore these effects in vivo in the AD model with the use of efficient methods of delivery.

3.3. Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor in AD

Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is considered as another potential neurotrophic factor for treatment of AD. BDNF is mediates synaptic plasticity and cognitive function [34]. Anatomically, a loss of synaptic contacts leads to the neuropathology of the disease, including deficits in cognition in AD [34]. In humans suffering from AD, BDNF mRNA and protein were found decreased in cholinergic neurons of the cortex and hippocampus [35]. Basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in AD patients show a reduced supply of target-derived BDNF [9]. A deficit in pro-BDNF protein also was found in the parietal cortex in AD [9]. It is clear that the reduction of BDNF levels in AD models, particularly in cholinergic neurons, indicates that this neurotrophic factor is a key factor in AD [35]. While other neurotrophic factors stimulate neuronal growth and protection, BDNF primarily enhances the cholinergic functions of neurons [35]. Considering the current prevalence and success of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors as AD drug therapy, BDNF therapy is certainly promising.

Although the mechanism of actions of BDNF is not clear, it might be mediated through the stimulation of postsynaptic TrkB receptors, which lead to depolarization via activation of the sodium ion conductance [36]. Through the depolarization, BDNF may be involved in long-term potentiation and cognition, which is characteristic of AD [37]. The molecular mechanism involved in the downregulation of BDNF in AD is unknown. Moreover, in regards to the BDNF gene, evidence has suggested that polymorphism of the BDNF gene is associated with late-onset AD [38]. Thus, BDNF polymorphism could be a predisposing factor for AD [38]. This suggests that BDNF gene variants are considered as risk factors for AD [39, 40].

The activation of TrkB by BDNF initiates a downstream signal that is crucial for plasticity and memory development [41-44]. It has been demonstrated that activation of TrkB increased synapse density and therefore is associated with improved cognition that is independent of the amyloid or tau pathways [45, 46]. The TrkB pathway is particularly relevant to AD because many AD patients have significant damage and loss of neurons by the time symptomology appears. Activation of TrkB specifically promoted the restoration of synaptic contacts, thereby improving cognitive function in later stage in AD patients [47]. One particular TrkB agonist, 7,8-dihydroxyflavone, has demonstrated neuroregenerative effects in AD. When 7,8-dihydroxyflavone is administered to lesioned mice, it increased the density of dendritic spines and reaffirmed the possibility of cognitive improvement in even severely damaged neuronal networks [47].

Interestingly, studies have identified that BDNF may be signaled through serotonin (5-HT) (reviewed by [48]). Evidence suggests that BDNF and 5-HT signaling play an important role in the pathogenesis in AD. The co-regulation between BDNF and 5-HT is characterized by activation of 5-HT receptors coupled to cAMP production and cAMP response-element binding protein activation, which induces BDNF gene transcription (reviewed by [49]). In turn, BDNF may stimulate the growth and sprouting of 5-HT neurons and possibly other types of neurons [50]. 5-HT and BDNF activate several genes that are a part of neural plasticity and survival, which might be a key factor in neurodegenerative diseases, including AD [49]. The interactions between BDNF and 5-HT play a role in neurogenesis, particularly with neuronal stem cells located in the hippocampus (reviewed by [48]). Together, these suggest that BDNF is a key factor in maintaining cell division, cell survival and cell function to lead to neuroprotection.

While the role of BDNF in neuroprotection is well established, it has been suggested and debated that BDNF polymorphisms and mutations may be directly mechanistically related to AD development, potentially as promoters of tau and amyloid aggregation [33, 51-53]. A recent study on BDNF knockout mice, however, indicates the possibility that reduced BDNF is simply a consequence of the AD pathology and does not play a significant individual role in AD prevention [54]. The study reaffirmed the therapeutic value of BDNF as beneficial to synaptic and cognitive function in AD patients but was unable to determine any potential for BDNF to act directly as an agent in AD pathology [55].

3.4. ADNF and ADNP Derived Peptides and Colivelin in AD

The use of derived peptides from activity-dependent neurotrophic factor (ADNF) and activity-dependent neuroprotective protein (ADNP) has proven successful in the attenuation of neurodegeneration in AD. Both ADNF and ADNP are synthesized and released from astroglia [56, 57]. The release of these trophic factors is regulated by vasoactive intestinal peptide [58]. The protective effects of ADNF and ADNP are based on nine amino acids (SALLRSIPA) and eight amino acids (NAPVSIPQ), respectively [Reviewed by [59]]. Thus, the derived peptides from ADNF and ADNP, termed ADNF-9 and NAP, respectively, have been shown to protect neuronal degeneration against the insults of oxidative stress and other related neurodegenerative models in vitro and in vivo [Reviewed by [59, 60]]. NAP exhibits the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and selectively interact with the tubulin and microtubule assembly, thus promoting neuronal outgrowth [61]. The neuroprotective effect of ADNF-9 and/or NAP was shown against neurotoxin β -amyloid peptide [56, 62, 63]. In addition, NAP was found to inhibit β-amyloid aggregation by binding to its 25-35 fragment at high affinity, consequently preventing its toxic effect [61].

Moreover, the neuronal calcium regulation involving NAP may contribute to neuronal survival. NAP colocalizes with microtubules, thereby regulating the mobilization of neuronal calcium [64, 65]. Another potential beneficial action of NAP has been suggested to involve the MAPK/ERK and PI3/Akt pathways [66]. It has been determined that stimulation of these two pathways leads to neuronal growth via the phosphorylation of cAMP response-element binding protein [66].

Furthermore, ADNP knockdown mice treated specifically with NAP demonstrated enhanced cognitive abilities [67]. It is important to note that NAP is currently under investigation in phase II clinical trial studies involving AD-related cognitive losses [68]. The most pharmaceutically relevant portion of ADNF is its active fragment, ADNF-9. ADNF-9 has been tested in a model of apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-deficient mouse; ApoE deficiency is considered as one of the risk factors of AD [56]. This study showed that daily injections of ADNF-9 to newborn ApoE-deficient mice improved the acquisition of developmental reflexes and prevented short-term memory deficits [56]. ADNF-9 has been observed to decrease Aβ peptide amyloids, reduce ApoE deficiencies, and prevent oxidative insults [69]. It has also been observed to increase synapse formation, promote axonal elongation via cAMP-dependent mechanisms, and increase chaperonin expression of heat shock protein 60 [56, 70, 71]. The increased expression of heat shock protein 60 is especially significant because it leads to additional protection against Aβ insult [70-72]. The use of therapeutic ADNF-9 was shown to have an effect on both memory and learning in conjunction with polyADP ribosylation catalyzed by poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1 [73]. Although several other ADNF-derived peptides have been tested, ADNF-9 has proven to be the most effective overall at preventing cell death [73].

New directions have been taken to synthesize the hybrid peptide, colivelin, composed of ADNF-9 and AGA-(C8R)HNG17 (PAGASRLLLTGEIDLP), a potent Humanin derivative [74]. Humanin is a bioactive peptide that prevents cell death by various familial AD-causative genes and β -amyloid peptide [74]. Although the exact mechanism of action is unclear, it is believed that Humanin inhibits the cytosolic Bcl-2 family of proapoptotic proteins [75-77]. Colivelin completely suppressed neuronal cell death against β -amyloid peptide in vitro [65]. In contrast to ADNF-9 alone, Colivelin has the characteristic of displaying its complete neuroprotective effect at variant concentrations [65]. In vivo experiments demonstrated that in the model of mice treated intracerebroventricullary with β -amyloid, Colivelin has a potent neuroprotective effect on β -amyloid-induced memory dysfunction as compared to animals treated with ADNF-9 alone [74]. Two pro-survival signals have been theorized to be possible mechanisms of Colivelin's action, the first being a Humanin-mediated STAT3 pathway, which has been shown to be especially relevant to protection against memory loss related to AD [65]. The second possible pro-survival signal is that of an ADNF-9 mediated Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV pathway [76]. This compound is considered a candidate for the treatment of AD, considering its great ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and prevent neurodegeneration.

4. CYTOKINE FUNCTION IN AD

4.1. Neuroprotective Abilities of Interleukin-10 in AD

The cytokine known as Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a potential candidate for AD treatment primarily due to its anti-inflammatory properties as well as its neuroprotective abilities. IL-10 displays a broad range of potential actions on neurogenesis [78]. IL-10 produces several anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1 receptor antagonists (IL-1ra), which deactivate inflammatory macrophages [79]. IL-10 has also been found to suppress inflammatory molecules TNF-α and IL-1β, which are induced by AD's trademark Aβ plaques [80]. The induction of IL-1ra production is especially relevant to AD treatment because it is believed that IL-1 is a key factor in both Aβ plaque deposition and increased APP formation [81]. Antagonizing the effects of IL-1, IL-1ra might help reduce the severity and density of Aβ plaque formation and aggregation.

Furthermore, IL-10 has displayed not only anti-inflammatory effects but also neuroprotective properties, including potential nerve repairing abilities mediated through NGF [82]. It is also suggested that IL-10 has the ability to block pro-apoptotic proteins, similar to the neuroprotective action of NAP [83]. A patent indicates the use of UV-B light radiation to increase levels of IL-10 [84]. The patent details a process that involves introducing UV-B light radiation directly to inflamed target areas in the brains of AD patients. The UVB radiation triggers a cytokine cascade, which eventually produces IL-10. The UV-B radiation ultimately deactivates inflammatory cells (Th1) and activates anti-inflammatory cells (Th2), which emit IL-10 [84]. These effects may lead to immunosuppression; therefore, it is necessary to focus the UV-B radiation directly on the inflamed areas of the brain. It is suggested that systemic exposure would result in full body immunosuppression, as evidenced in animal trials [85].

4.2. Neuronal Growth and Interferon-β

The cytokine known as interferon-β (IFN-β) stimulates astrocytes to release NGF, ultimately promoting neuronal growth [86]. This property of IFN-β has already been exploited in the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) [87]. Recombinant human IFN-β, known under the trade name “Rebif”, has been shown to directly reduce the progression of MS as evidenced by MRI readings [88]. One patent indicates that a modified version of this compound may be used to treat AD in a similar manner [86]. The patent describes a multimeric fusion protein that consists of both IFN-β and a traditional cholinesterase inhibitor fused to an immunoglobulin. The synergistic action of the drug would potentially both increase neuron growth and stimulate neuronal function.

5. METHODS FOR TARGETING Β-AMYLOID PEPTIDE

5.1. β-Secretase and -Secretase Inhibitors

The signature neuronal γ β -amyloid peptides and its associated pathway are major focuses of AD drug design. The important target to prevent amyloid formation is a β -secretase inhibitor. However, production of a safe and successful β -secretase inhibitor is a long and difficult process. β-secretase inhibitor drugs in trial are often quickly metabolized or displaced by transport systems, primarily pglycoprotein [89]. Phase I clinical trials studying a β -secretase inhibitor known as LY2811376 were terminated due to the side effect of the drug in inducing retinal damage in rat models [89]. -secretase inhibitors, which theoretically prevent the cleavage of c99 into amyloid-prone aβ4 segments, have been developed. Recent clinical trials of the drug Semagacestat, a γ-secretase inhibitor, were terminated during phase III clinical trials due to declining cognitive abilities and an increased risk of skin cancer [90]. Additionally, a clinical trial on the drug Tarenflurbil, a γ-secretase modulator, was also terminated during phase III because of poor results [90]. It is believed that interfering with secretase activity may indirectly affect unrelated pathways, such as NOTCH, which may lead to such unforeseen reactions [90].

5.2. β-Amyloid Antibodies

How can we avoid interfering with metabolic pathways but still target amyloid aggregation? A frequently proposed method of directly inhibiting growth of β-amyloid peptide is through the use of antibodies. By targeting specific Aβ4 β-amyloid peptides with antibodies, the goal is to inhibit the aggregation of the neurotoxic amyloid plaques in the brains of AD patients. Aβ40 and Aβ42 are both endogenous compounds, and therefore problems arise with the use of non-selective Aβ40 and Aβ42 antibodies [91]. These proteins have yet unknown functions in the human body, thus causing unforeseen adverse reactions, which may be because the immune system fails to recognize endogenous proteins as antigens or because it produces an inflammatory response to them [92]. A phase III clinical trial of an Aβ42 antibody known as AN-1792 demonstrated the dangers of such complications, as encephalitis was reported in 6% of the test subjects [91]. The phase III clinical trial for this drug was terminated due to these side effects.

Another Aβ-antibody drug for which clinical trials were recently terminated is Bapineuzumab [93]. Bapineuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody designed to specifically target an epitope consisting of amino acids 1-10 of Aβ42 [93]. Bapineuzumab phase III clinical trials, conducted in 2012, were deemed a failure due to a lack of evident efficacy when compared to a placebo [91]. However, the monoclonal antibody drug, Solanezumab, concluded phase II clinical trial testing in 2012 [94]. Solanezumab is a humanized antibody that is designed to specifically target an epitope between amino acids 13 and 28 of the Aβ peptide [95]. By targeting this specific sequence, the drug aims to sequester Aβ strands, thus preventing aggregation [95]. The results of the trial proved that Solanezumab was well tolerated when given in weekly doses and had few side effects [94]. Although the trial results were not nearly as prolific as hoped, a direct correlation between increased unbound Aβ levels and increased drug dose was demonstrated, indicating the potential anti-Aβ aggregation properties of the drug [94]. A phase III trial has been ordered to further investigate the drug's anti-Aβ efficacy [94].

5.3. Targeting the Aβ-Arc Peptide

Rather than targeting all wild-type Aβ4 peptides, one patented method indicates targeting a specific mutation that has been observed to consistently result in progressive dementia [96]. The patent indicates that protofibrils, not mature Aβ fibrils, are the root of neurotoxicity in AD. After nucleation, the Aβ precursor protofibrils have the predisposition to both elongate and laterally associate to form mature fibrils [97]. Thus, mutations during nucleation may result in abnormal aggregation [97]. The patent proposes that antibodies would be synthesized to specifically target the epitope created by the replacement of a glutamic acid with a glycine at codon 693 of APP. This single substitution of glycine with glutamic acid at position 22 in the Aβ arc was found to dramatically increase protofibril growth rate and capacity. The target would selectively be Aβ fibrils, as the Aβ peptide is in the protofibril conformation when used as an immunogen. Such target selectivity and specificity would greatly reduce the possibility of unforeseen adverse reactions, such as the encephalitis seen in the nonselective Aβ42 vaccine [91].

The basis of another patent is the observed effects of an APP mutation in the Aβ sequence at codon 693 (E693G) on a family from Northern Sweden, known as the “Arctic mutation” (Aβ-Arc) [98]. The carriers of the Arctic mutation display progressive neurodegeneration and dementia. Interestingly, carriers also exhibit decreased Aβ plasma levels, which seem to contradict previous assumptions that Aβ plaque levels have a direct correlation to progressive dementia [99]. This observation was also supported in vivo, as cells transfected with the APP E693G displayed very low concentration levels of Aβ42 [96]. Fibrillization studies have concluded that the Aβ-arc mutation produces longer and less curved Aβ peptides, prone to twisting, that also form at both an accelerated rate and quantity when compared to wild-type Aβ [96].

5.4. Modulation of NMDAR in AD

Modulation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate-type glutamate receptor (NMDAR) has been shown to prevent amyloid-β production and its subsequent aggregation [100]. As previously mentioned, improper cleavage of APP by β -secretases can lead to the Aβ formation characteristic of AD. NMDAR-dependent signaling pathways, however, aid in the proper regulation of APP cleavage [101]. NMDAR agonists stimulate a Ca2+ dependent PKC dependent pathway, leading to the activation of β-secretase [101]. Cleavage of APP by β-secretase leads to what is known as the amyloidogenic pathway, or the neurotoxic amyloid plaque forming pathway [11]. As a result, the increased Aβ levels can enhance the production of TNF-α and INF- which both reduce D-serine [102]. The inhibition of D-serine appears to be important in the production of neurotoxic Aβ. A patent indicates a synergistic NMDAR antagonist and co-agonist drug design to prevent this pathway's formation [103]. The co-administration of an NMDAR antagonist and co-agonist, the aforementioned D-serine, not only prevents the amyloidogenic pathway but also triggers the formation of the nontoxic soluble Alpha-APP fragments. Stimulation of NMDAR by D-serine increases intracellular Ca2+ and activates a Ca2+ dependent PKA and CaMKII-dependent pathway [101]. These pathways activate α -secretase, cleaving APP into a non-amyloid forming product. The patent indicates the balance between β -secretase (amyloid forming) and α -secretase (non-amyloid forming) as crucial for preventing and treating AD.

6. TARGETING TAU-TAU INTERACTIONS

The second major pathological hallmark of AD is neurofibrillary tangles consisting of tau proteins, a condition known as “tauopathy” [104]. Under normal physiological conditions, tau proteins are necessary to stabilize the microtubules (tubulin) in the brain that facilitate movement of synaptic elements. Normal tau proteins are also rich in hydrophilic amino acid residues and are thus water soluble [104]. In AD, however, these soluble tau proteins change into an insoluble polymerized cross-β-sheet form known as paired helical filaments (PHF) [105]. PHFs are insoluble due to a protease-resistant core fragment at amino acids 93-95 [106]. These PHF forms cannot sustain the neuronal microtubules, and they inhibit axonal transport of neurologically active substances, resulting in synaptic loss and cognitive impairment [107]. The PHF form most likely features a certain conformational change that induces cross-linking between other PHF tau proteins, creating the insoluble cluster [108]. One patent indicates the development of a compound that would block the active cross-linking site on PHF, thereby inhibiting its ability to cluster into a plaque [109].

The tau proteins tangled within neurofibrillary clusters also have the distinct trait of hyperphosphorylation. Phosphorylation of tau under normal conditions allows for the formation of paired helical filaments [110]. However, in AD, the two kinases cyclin dependent kinase and glycogen synthase kinase 3B are responsible for overactive hyperphosphorylation of tau, contributing to neurofibrillary aggregation [110].

There are several key patterns, which appear in tangle-prone Tau, that can be used to distinguish it from normal Tau, such that normally functioning Tau is not also targeted by the proposed pharmaceutical compounds [108]. The patent theorizes that a monoclonal antibody could be developed to target these distinguishing traits, such as the truncation at the Glu-391 C-terminus of PHF [108]. Regular tau proteins do not feature this Glu-391 truncation, and therefore regular tautubulin binding would not be effected [111].

6.1. Use of Phenothiazines in Tau-Tau Targeting

The patent describes the use of Phenothiazines, which function in a similar manner as an antibody to a hypersensitive tau protein. The most effective phenothiazines highlighted in a structure-activity relationship study were toluidine blue O, thionine, azure A, azure B, and 1,9-dimethyl-methylene Blue. Phenothiazines like thionine have the capability to block neurofibrillary aggregation at high affinity tau capture sites by either aiding in the neuronal filament differentiation or by directly blocking the formation of neurofibrillary tangles [109]. According to the patent, these compounds also lack the ability to disrupt normal physiological Tau-microtubules complexes. Under normal physiological conditions, the tandem repeat region of tau serves as the normal tubulin binding site [112]. This same region is responsible for the formation of PHFs because it contains the sequence responsible for high affinity tau aggregation. Once aggregated, PHFs are difficult to eliminate because they contain a protease-resistant core, therefore it is important to prevent aggregation altogether [112].

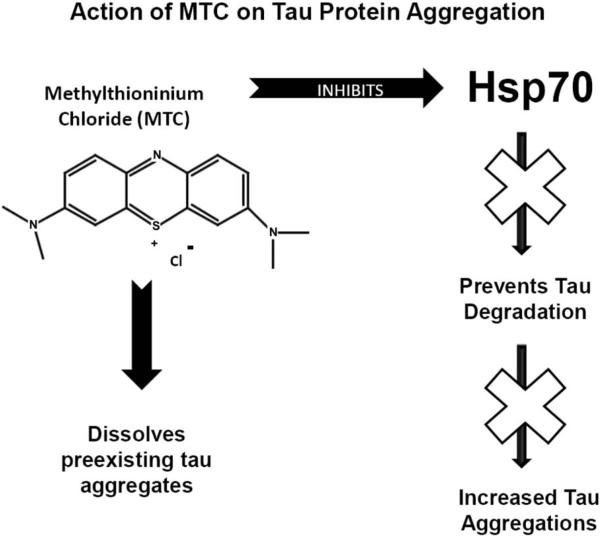

6.2. Use of Methylthioninium Chloride in Tau-Tau Targeting

A phenothiazine tau-tau inhibitor chemically known as methylthioninium chloride (MTC, methylene blue) completed phase II clinical trials and is starting phase III clinical trials [113]. Previous studies on mice have displayed MTC's ability to not only prevent PHF from aggregating but also dissolve existing tau aggregates [114] (Fig. 3). In rat stroke models, MTC was able to reverse neurotoxicity and reduce lesion size [115]. MTC displayed multiple mechanisms for reducing tautau interactions, including inhibition of heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) ATPase [116, 117]. Hsp70 appears to be a protective factor for tau that prevents degradation (Fig. 3). Inhibiting Hsp70 ATPase removes this protection, increasing the degradation of tau proteins and subsequently preventing aggregation [116, 117]. At low doses, MTC exhibits extraordinary antioxidant abilities, yet another unique neuroprotective feature [118-120]. This is due to MTC's capability to act as an electron cycler in the electron transport chain, which has been proven to both enhance memory and serve as a neuroprotective process [121, 122]. Data have provided evidence that in low doses, MTC also provides quick, short-term memory enhancement by oxidizing hemoglobin and thereby increasing the amount of oxygen transported to the brain [122]. MTC is extremely lipophilic and therefore capable of crossing biomembranes, including the blood-brain barrier, making it an excellent candidate as a neurologically active drug [123].

Fig. (3).

Diagram shows Methylthioninium chloride's (MTC) ability to inhibit tau protein aggregation. The action of MTC is two-fold, as the drug both prevents new tau aggregation via inhibition of heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and dissolves preexisting tau aggregates. Hsp70 appears to be a protective factor for tau that prevents degradation. Inhibiting Hsp70 removes this protection, increasing the degradation of tau and subsequently preventing aggregation.

7. INSULIN's POTENTIAL ROLE IN AD

Impairment of cerebral glucose utilization often precedes or enhances mental dysfunction; therefore compromised insulin signaling pathways may play a role in the development of cognitive diseases, including AD [124]. Improper regulation of both insulin and insulin growth factor-1 receptors has been indicated in AD patient brains [125]. Mice deficient in insulin receptor substrate-2 or the neuronal insulin receptor gene display reduced brain growth and increased tau phosphorylation, a direct link to cerebral AD conditions [126]. Much of the significant evidence reinforcing this theory comes from the study of mice treated with intracerebral doses of streptozotocin paired with oxidative stress [127]. Streptozotocin depletes insulin and insulin growth factor signaling cascades in the brains of mice, resulting in decreased brain size and activity, as well as phosphorylated tau proteins and amyloid clusters similar to AD conditions [124, 128]. Streptozotocin metabolites have an alkylating property that generates reactive oxygen species, resulting in DNA damage and a reduction of glucose metabolism in both the cortex and hippocampus [124, 129].

8. CONCLUSION AND CLOSING THOUGHTS

Although the mechanism of AD development is unknown, the pathological hallmarks are prevalent and predictable in patients. The current clinical drug treatments of AD simply slow the progression of the disease by providing neurological stimulation but do not target these characteristic developments. There is potential for the application of drugs that specifically target the neurodegenerative pathological hallmarks of β -amyloid protein plaques and tau protein aggregates. Furthermore, neurotrophic factors such as BDNF, FGF, NGF, ADNF, and ADNP in increasing neuronal growth could potentially reverse neurodegeneration. Targeting β -amyloid protein plaques, whether directly via antibodies or indirectly via secretase inhibitors, has proven to be difficult. Several β -amyloid antibody trials were terminated before completion due to poor results, and no efficacious secretase inhibitors have been developed. An upcoming phase III clinical trial of the tau-tau aggregation inhibitor MTC, however, is very promising due to its previous success in reversing neurodegeneration and preventing tau aggregation. The current generation of clinical and experimental drugs can shed the light on potential therapies to attenuate or slow the progression of AD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Award Number R01AA019458 (Y.S.) from the National Institutes on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Mrs. Charisse Montgomery for editing this manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- Aβ

Amyloid β

- Aβ-Arc

Arctic mutation

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ADNF

Activity-dependent neurotrophic factor

- ADNP

Activity-dependent neuroprotective protein

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- BDNF

Brain derived neurotrophic factor

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- IFN-β

Interferon-β

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1β

- IL-1ra

Interleukin-1 receptor agonist

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- MTC

Methylthioninium chloride

- NGF

Nerve growth factor

- NMDAR

N-methyl-D-aspartate-type glutamate receptor

- PHF

Paired helical filament

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harman D. Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis: role of aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1067:454–60. doi: 10.1196/annals.1354.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meraz-Rios MA, Toral-Rios D, Franco-Bocanegra D, Villeda-Hernandez J, Campos-Pena V. Inflammatory process in Alzheimer's Disease. Front Integr Neurosci. 2013;7:59. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chartier-Harlin MC, Crawford F, Hamandi K, et al. Screening for the beta-amyloid precursor protein mutation (APP717: Val----Ile) in extended pedigrees with early onset Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 1991;129(1):134–5. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90738-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(3):383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitazawa M, Yamasaki TR, LaFerla FM. Microglia as a potential bridge between the amyloid beta-peptide and tau. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1035:85–103. doi: 10.1196/annals.1332.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murer MG, Yan Q, Raisman-Vozari R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the control human brain, and in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63(1):71–124. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, et al. A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol, or both as treatment for Alzheimer's disease. The Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(17):1216–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704243361704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reisberg B, Doody R, Stoffler A, et al. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(14):1333–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane RM, Kivipelto M, Greig NH. Acetylcholinesterase and its inhibition in Alzheimer disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27(3):141–9. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200405000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheuner D, Eckman C, Jensen M, et al. Secreted amyloid beta-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer's disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 1996;2(8):864–70. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vassar R. BACE1: the beta-secretase enzyme in Alzheimer's disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;23(1-2):105–14. doi: 10.1385/JMN:23:1-2:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanzi RE, Bertram L. Twenty years of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid hypothesis: a genetic perspective. Cell. 2005;120(4):545–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy J. Amyloid double trouble. Nat Genet. 2006;38(1):11–2. doi: 10.1038/ng0106-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Strooper B, Annaert W. Novel research horizons for presenilins and gamma-secretases in cell biology and disease. Annu Rev Cell Develop Biol. 2010;26:235–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pluta R, Furmaga-Jablonska W, Maciejewski R, Ulamek-Koziol M, Jablonski M. Brain ischemia activates beta- and gamma-secretase cleavage of amyloid precursor protein: significance in sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;47(1):425–34. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8360-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullen RJ, Buck CR, Smith AM. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development. 1992;116(1):201–11. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sisodia SS, St George-Hyslop PH. gamma-Secretase, Notch, Abeta and Alzheimer's disease: where do the presenilins fit in? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(4):281–90. doi: 10.1038/nrn785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinha S, Lieberburg I. Cellular mechanisms of beta-amyloid production and secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(20):11049–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuszynski MH, U HS, Amaral DG, Gage FH. Nerve growth factor infusion in the primate brain reduces lesion-induced cholinergic neuronal degeneration. J Neurosci. 1990;10(11):3604–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03604.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winkler J, Thal LJ, Gage FH, Fisher LJ. Cholinergic strategies for Alzheimer's disease. J Mol Med. 1998;76(8):555–67. doi: 10.1007/s001090050250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer W, Wictorin K, Bjorklund A, et al. Amelioration of cholinergic neuron atrophy and spatial memory impairment in aged rats by nerve growth factor. Nature. 1987;329(6134):65–8. doi: 10.1038/329065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koliatsos VE, Nauta HJ, Clatterbuck RE, et al. Mouse nerve growth factor prevents degeneration of axotomized basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in the monkey. J Neurosci. 1990;10(12):3801–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-12-03801.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuszynski MH, Sang H, Yoshida K, Gage FH. Recombinant human nerve growth factor infusions prevent cholinergic neuronal degeneration in the adult primate brain. Ann Neurol. 1991;30(5):625–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connor B, Dragunow M. The role of neuronal growth factors in neurodegenerative disorders of the human brain. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;27(1):1–39. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossner S, Ueberham U, Schliebs R, Perez-Polo JR, Bigl V. The regulation of amyloid precursor protein metabolism by cholinergic mechanisms and neurotrophin receptor signaling. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;56(5):541–69. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorns V, Masliah E. Evidence for neuroprotective effects of acidic fibroblast growth factor in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58(3):296–306. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199903000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo ZH, Mattson MP. Neurotrophic factors protect cortical synaptic terminals against amyloid and oxidative stress-induced impairment of glucose transport, glutamate transport and mitochondrial function. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10(1):50–7. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckenstein FP. Fibroblast growth factors in the nervous system. J Neurobiol. 1994;25(11):1467–80. doi: 10.1002/neu.480251112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mattson MP, Tomaselli KJ, Rydel RE. Calcium-destabilizing and neurodegenerative effects of aggregated beta-amyloid peptide are attenuated by basic FGF. Brain Res. 1993;621(1):35–49. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindahl B, Westling C, Gimenez-Gallego G, Lindahl U, Salmivirta M. Common binding sites for beta-amyloid fibrils and fibroblast growth factor-2 in heparan sulfate from human cerebral cortex. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(43):30631–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santiard-Baron D, Gosset P, Nicole A, et al. Identification of beta-amyloid-responsive genes by RNA differential display: early induction of a DNA damage-inducible gene, gadd45. Exp Neurol. 1999;158(1):206–13. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeKosky ST, Scheff SW, Styren SD. Structural correlates of cognition in dementia: quantification and assessment of synapse change. Neurodegeneration. 1996;5(4):417–21. doi: 10.1006/neur.1996.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamagata H, Chen Y, Akatsu H, et al. Promoter polymorphism in fibroblast growth factor 1 gene increases risk of definite Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;321(2):320–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu B. BDNF and activity-dependent synaptic modulation. Learn Mem. 2003;10(2):86–98. doi: 10.1101/lm.54603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fahnestock M, Garzon D, Holsinger RM, Michalski B. Neurotrophic factors and Alzheimer's disease: are we focusing on the wrong molecule? J Neural Transm Suppl. 2002;(62):241–52. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6139-5_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kafitz KW, Rose CR, Thoenen H, Konnerth A. Neurotrophin-evoked rapid excitation through TrkB receptors. Nature. 1999;401(6756):918–21. doi: 10.1038/44847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Neurotrophins: roles in neuronal development and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:677–736. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egan MF, Kojima M, Callicott JH, et al. The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell. 2003;112(2):257–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kunugi H, Ueki A, Otsuka M, et al. A novel polymorphism of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene associated with late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2001;6(1):83–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olin D, MacMurray J, Comings DE. Risk of late-onset Alzheimer's disease associated with BDNF C270T polymorphism. Neurosci Lett. 2005;381(3):275–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bartoletti A, Cancedda L, Reid SW, et al. Heterozygous knock-out mice for brain-derived neurotrophic factor show a pathway-specific impairment of long-term potentiation but normal critical period for monocular deprivation. J Neurosci. 2002;22(23):10072–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10072.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorski JA, Zeiler SR, Tamowski S, Jones KR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for the maintenance of cortical dendrites. J Neurosci. 2003;23(17):6856–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06856.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heldt SA, Stanek L, Chhatwal JP, Ressler KJ. Hippocampus-specific deletion of BDNF in adult mice impairs spatial memory and extinction of aversive memories. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(7):656–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monteggia LM, Barrot M, Powell CM, et al. Essential role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in adult hippocampal function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(29):10827–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402141101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blurton-Jones M, Kitazawa M, Martinez-Coria H, et al. Neural stem cells improve cognition via BDNF in a transgenic model of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(32):13594–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901402106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagahara AH, Merrill DA, Coppola G, et al. Neuroprotective effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rodent and primate models of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 2009;15(3):331–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castello NA, Nguyen MH, Tran JD, et al. 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone, a Small Molecule TrkB Agonist, Improves Spatial Memory and Increases Thin Spine Density in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer Disease-Like Neuronal Loss. PloS One. 2014;9(3):e91453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Powrozek TA, Sari Y, Singh RP, Zhou FC. Neurotransmitters and substances of abuse: effects on adult neurogenesis. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2004;1(3):251–60. doi: 10.2174/1567202043362225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mattson MP, Maudsley S, Martin B. BDNF and 5-HT: a dynamic duo in age-related neuronal plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27(10):589–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mamounas LA, Blue ME, Siuciak JA, Altar CA. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes the survival and sprouting of serotonergic axons in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1995;15(12):7929–39. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-07929.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bodner SM, Berrettini W, van Deerlin V, et al. Genetic variation in the brain derived neurotrophic factor gene in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;134B(1):1–5. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akatsu H, Yamagata HD, Kawamata J, et al. Variations in the BDNF gene in autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies in Japan. Dementia Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(3):216–22. doi: 10.1159/000094933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang R, Huang J, Cathcart H, Smith S, Poduslo SE. Genetic variants in brain-derived neurotrophic factor associated with Alzheimer's disease. J Med Genet. 2007;44(2):e66. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.044883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Castello NA, Green KN, LaFerla FM. Genetic knockdown of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in 3xTg-AD mice does not alter Abeta or tau pathology. PloS One. 2012;7(8):e39566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brenneman DE, Castellon R, Spong CY, Hauser JM, Gozes I. Neurotrophic components of ADNF I complex. 2008 US7427590.

- 56.Bassan M, Zamostiano R, Davidson A, et al. Complete sequence of a novel protein containing a femtomolar-activity-dependent neuroprotective peptide. J Neurochem. 1999;72(3):1283–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0721283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zusev M, Gozes I. Differential regulation of activity-dependent neuroprotective protein in rat astrocytes by VIP and PACAP. Regul Pept. 2004;123(1-3):33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Furman S, Steingart RA, Mandel S, et al. Subcellular localization and secretion of activity-dependent neuroprotective protein in astrocytes. Neuron Glia Biol. 2004;1(3):193–9. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X05000013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sari Y, Gozes I. Brain deficits associated with fetal alcohol exposure may be protected, in part, by peptides derived from activity-dependent neurotrophic factor and activity-dependent neuroprotective protein. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2006;52(1):107–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gozes I. Activity-dependent neuroprotective protein: From gene to drug candidate. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;114(2):146–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ashur-Fabian O, Segal-Ruder Y, Skutelsky E, et al. The neuroprotective peptide NAP inhibits the aggregation of the beta-amyloid peptide. Peptides. 2003;24(9):1413–23. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gozes I, Bassan M, Zamostiano R, et al. A novel signaling molecule for neuropeptide action: activity-dependent neuroprotective protein. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;897:125–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zemlyak I, Furman S, Brenneman DE, Gozes I. A novel peptide prevents death in enriched neuronal cultures. Regul Pept. 2000;96(1-2):39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Divinski I, Mittelman L, Gozes I. A femtomolar acting octapeptide interacts with tubulin and protects astrocytes against zinc intoxication. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(2):28531–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamada M, Chiba T, Sasabe J, et al. Nasal Colivelin treatment ameliorates memory impairment related to Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(8):2020–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fernandez-Montesinos R, Torres M, Baglietto-Vargas D, et al. Activity-dependant neuroprotective protein (ADNP) expression in the amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 mouse model of Alzheimers disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2010;41(1):114–20. doi: 10.1007/s12031-009-9300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vulih-Shultzman I, Pinhasov A, Mandel S, et al. Activity-Dependent Neuroprotective Protein Snippet NAP Reduces Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Enhances Learning in a Novel Transgenic Mouse Model. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 2007;323:438–49. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.129551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gozes I. NAP (davunetide) provides functional and structural neuroprotection. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:1040–4. doi: 10.2174/138161211795589373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brenneman DE, Hauser J, Neale E, et al. Activity-dependent neurotrophic factor: Structure-activity relationships of femtomolar-acting peptides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285(2):619–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brenneman DE, Gozes I. A femtomolar-acting neuroprotective peptide. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2299–307. doi: 10.1172/JCI118672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Glazner GW, Gressens P, Lee SJ, et al. Activity-dependent neurotrophic factor: a potent regulator of embryonic growth and development. Anat Embryol. 1999;200(1):65–71. doi: 10.1007/s004290050260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blondel O, Collin C, McCarran WJ, et al. A glia-derived signal regulating neuronal differentiation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:8012–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08012.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Visochek L, Steingart RA, Vulih-Shultzman I, et al. PolyADP-ribosylation is involved in neurotrophic activity. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7420–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0333-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chiba T, Yamada M, Hashimoto Y, et al. Development of a femtomolar-acting humanin derivative named colivelin by attaching activity-dependent neurotrophic factor to its N terminus: characterization of colivelin-mediated neuroprotection against Alzheimer's disease-relevant insults in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci. 2005;25(44):10252–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3348-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guo B, Zhai D, Cabezas E, et al. Humanin peptide suppresses apoptosis by interfering with Bax activation. Nature. 2003;423:456–61. doi: 10.1038/nature01627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Luciano F, Zhai D, Zhu X, et al. Cytoprotective peptide humanin binds and inhibits proapoptotic Bcl- 2/Bax family protein BimEL. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:15825–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhai D, Luciano F, Zhu X, et al. Humanin binds and nullifies Bid activity by blocking its activation of Bax and Bak. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15815–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fuster-Matanzo A, Llorens-Martin M, Hernandez F, Avila J. Role of neuroinflammation in adult neurogenesis and Alzheimer disease: therapeutic approaches. Mediat Inflammation. 2013;2013:260925. doi: 10.1155/2013/260925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brennan FM. Interleukin 10 and arthritis. Theumatology. 1999;38:293–97. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hart P, Ahern MJ, Smith MD, Finlay-Jones JJ. Comparison of the suppressive effects of interleukin-10 and interleukin-4 on synovial fluid macrophages and blood monocytes from patients with inflammatory arthritis. Immunology. 1995;84:536–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sutton ET, Thomas T, Bryant MW, et al. Amyloid-beta peptide induced inflammatory reaction is mediated by the cytokines tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1999;31(3):313–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brodie C. Differential effects of Th1 and Th2 derived cytokines on NGF synthesis by mouse astrocytes. FEBS Lett. 1996;395:117–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Strle K, Zhou JH, Broussard SR, et al. IL-10 promotes survival of microglia without activating Akt. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;122(1-2):9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dimauro T, Attawia M, Lilienfeld S, et al. Light-Based Implants for treating Alzheimer's Disease. 2006 Patent US 20060100679 A1.

- 85.Kang K, Hammerberg C, Meunier L, Cooper KD. CD11b+ macrophages that infiltrate human epidermis after in vivo ultraviolet exposure potently produce IL-10 and represent the major secretory source of epidermal IL-10 protein. J Immunol. 1994;153(11):5256–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Grimaldi L. Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. 2007 Patent US 20070110715 A1.

- 87.Goodkin DE. Interferon beta therapy for multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1998;352(9139):1486–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kalincik T, Spelman T, Trojano M, et al. Persistence on therapy and propensity matched outcome comparison of two subcutaneous interferon Beta 1a dosages for multiple sclerosis. PloS One. 2013;8(5):e63480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.May PC, Dean RA, Lowe SL, et al. Robust central reduction of amyloid-beta in humans with an orally available, non-peptidic beta-secretase inhibitor. J Neurosci. 2011;31(46):16507–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3647-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gijsen HJ, Mercken M. gamma-Secretase Modulators: Can We Combine Potency with Safety? Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:295207. doi: 10.1155/2012/295207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lambracht-Washington D, Rosenberg RN. Active DNA Abeta42 vaccination as immunotherapy for Alzheimer disease. Transl Neurosci. 2012;3(4):307–13. doi: 10.2478/s13380-012-0037-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fox NC, Black RS, Gilman S, et al. Effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) on MRI measures of cerebral volume in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;64(9):1563–72. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159743.08996.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Basi G, Saldanha JW. Humanized antibodies that recognize beta amyloid peptide. 2007 Patent US 7189819 B2.

- 94.Farlow M, Arnold SE, van Dyck CH, et al. Safety and biomarker effects of solanezumab in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(4):261–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.09.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Holtzman DM, DeMattos R, Bales KR, et al. Humanized antibodies that sequester abeta peptide. 2007 US Patent US7195761 B2.

- 96.Lannfelt L, Nilsberth C, Westlind-Danielsson A, Naslund J. Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. 2007 Patent US 7179463 B2.

- 97.Ghosh P, Kumar A, Datta B, Rangachari V. Dynamics of protofibril elongation and association involved in Abeta42 peptide aggregation in Alzheimer's disease. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11(Suppl 6):S24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-S6-S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Norlin N, Hellberg M, Filippov A, et al. Aggregation and fibril morphology of the Arctic mutation of Alzheimer's Abeta peptide by CD, TEM, STEM and in situ AFM. J Struct Biol. 2012;180(1):174–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Suzuki N, Cheung TT, Cai XD, et al. An increased percentage of long amyloid beta protein secreted by familial amyloid beta protein precursor (beta APP717) mutants. Science. 1994;264(5163):1336–40. doi: 10.1126/science.8191290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chen HS, Lipton SA. Pharmacological implications of two distinct mechanisms of interaction of memantine with N-methyl-D-aspartate-gated channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314(3):961–71. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Parsons CG, Stoffler A, Danysz W. Memantine: a NMDA receptor antagonist that improves memory by restoration of homeostasis in the glutamatergic system--too little activation is bad, too much is even worse. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53(6):699–723. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wenk GL, Parsons CG, Danysz W. Potential role of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors as executors of neurodegeneration resulting from diverse insults: focus on memantine. Behav Pharmacol. 2006;17(5-6):411–24. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schneiter S. Novel Treatment for Alzheimer's Disease. 2009 Patent EP 2 111 858 A1.

- 104.Bulic B, Pickhardt M, Schmidt B, et al. Development of Tau Aggregation Inhibitors for Alzheimer's Disease. Angewandte Chem. 2009;48:1740–52. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mukaetova-Ladinska EBH,C, Roth M, Wischik C. Biochemical and anatomical redistribution of tau protein in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 1993;143(2):565–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wischik CM. Structural characterization of the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4884–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yoshiyama Y, Higuchi M, Zhang B, et al. Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron. 2007;53(3):337–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Novak M. Molecular Characterization of the Minimal Protease Resistant Tau Unit of the Alzheimer's Disease Paired Helical Filament. EMBO J. 1993;12(1):365–70. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wischik C, Edwards PC, Harrington CR, Roth M, Klug A. Inhibition of tau-tau-association. 2012 Patent US8278298 B2.

- 110.Jayapalan S, Natarajan J. The role of CDK5 and GSK3B kinases in hyperphosphorylation of microtubule associated protein tau (MAPT) in Alzheimer's disease. Bioinformation. 2013;9(20):1023–30. doi: 10.6026/97320630091023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mena R, Edwards PC, Harrington CR, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Wischik CM. Staging the pathological assembly of truncated tau protein into paired helical filaments in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;91(6):633–41. doi: 10.1007/s004010050477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jakes R, Novak M, Davison M, Wischik CM. Identification of 3- and 4-repeat tau isoforms within the PHF in Alzheimer's disease. EMBO J. 1991;10(10):2725–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07820.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wischik C, Staff R. Challenges in the conduct of disease-modifying trials in AD: practical experience from a phase 2 trial of Tau-aggregation inhibitor therapy. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13(4):367–9. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Harrington C, Rickard JE, Horsley D, et al. Methylthionium chloride (MTC) acts as a Tau aggregation inhibitor (TAI) in a cellular model and reverses Tau pathology in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(4):120–1. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rojas JC, Simola N, Kermath BA, et al. Striatal neuroprotection with methylene blue. Neuroscience. 2009;163(3):877–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Jinwal UK, Miyata Y, Koren J, 3rd, et al. Chemical manipulation of hsp70 ATPase activity regulates tau stability. J Neurosci. 2009;29(39):12079–88. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3345-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Medina DX, Caccamo A, Oddo S. Methylene blue reduces abeta levels and rescues early cognitive deficit by increasing proteasome activity. Brain Pathol. 2011;21(2):140–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Atamna H, Nguyen A, Schultz C, et al. Methylene blue delays cellular senescence and enhances key mitochondrial biochemical pathways. FASEB J. 2008;22(3):703–12. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9610com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rojas JC, John JM, Lee J, Gonzalez-Lima F. Methylene blue provides behavioral and metabolic neuroprotection against optic neuropathy. Neurotox Res. 2009;15(3):260–73. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9027-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wen Y, Li W, Poteet EC, et al. Alternative mitochondrial electron transfer as a novel strategy for neuroprotection. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(18):16504–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.208447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Callaway NL, Riha PD, Bruchey AK, Munshi Z, Gonzalez-Lima F. Methylene blue improves brain oxidative metabolism and memory retention in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;77(1):175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Congdon EE, Wu JW, Myeku N, et al. Methylthioninium chloride (methylene blue) induces autophagy and attenuates tauopathy in vitro and in vivo. Autophagy. 2012;8(4):609–22. doi: 10.4161/auto.19048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.May JM, Qu ZC, Whitesell RR. Generation of oxidant stress in cultured endothelial cells by methylene blue: protective effects of glucose and ascorbic acid. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66(5):777–84. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00408-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.de la Monte SM, Wands JR. Treatment Of Alzheimer's Disease. 2010 Patent US7833513 B2.

- 125.Moloney AM, Griffin RJ, Timmons S, et al. D0efects in IGF-1 receptor, insulin receptor and IRS-1/2 in Alzheimer's disease indicate possible resistance to IGF-1 and insulin signalling. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31(2):224–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Schubert M, Brazil DP, Burks DJ, et al. Insulin receptor substrate-2 deficiency impairs brain growth and promotes tau phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2003;23(18):7084–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-18-07084.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Duelli R, Schrock H, Kuschinsky W, Hoyer S. Intracerebroventricular injection of streptozotocin induces discrete local changes in cerebral glucose utilization in rats. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1994;12(8):737–43. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(94)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Plaschke K, Hoyer S. Action of the diabetogenic drug streptozotocin on glycolytic and glycogenolytic metabolism in adult rat brain cortex and hippocampus. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1993;11(4):477–83. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(93)90021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Perry G, Castellani RJ, Hirai K, Smith MA. Reactive Oxygen Species Mediate Cellular Damage in Alzheimer Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 1998;1(1):45–55. doi: 10.3233/jad-1998-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]