Abstract

Perlecan/Hspg2 (Pln) is a large heparan sulfate proteoglycan abundant in the extracellular matrix of cartilage and the lacuno-canalicular space of adult bones. While Pln function during cartilage development is critical, evidenced by deficiency disorders including Schwartz-Jampel Syndrome and dyssegmental dysplasia Silverman-Handmaker type, little is known about its function in development of bone shape and quality. The purpose of this study was to understand the contribution of Pln to bone geometric and mechanical properties. We used hypomorph mutant mice that secrete negligible amount of Pln into skeletal tissues and analyzed their adult bone properties using micro-computed tomography and three-point-bending tests. Bone shortening and widening in Pln mutants was observed and could be attributed to loss of growth plate organization and accelerated osteogenesis that was reflected by elevated cortical thickness at older ages. This effect was more pronounced in Pln mutant females indicating a gender-specific effect of Pln deficiency on bone geometry. Additionally, mutant females, and to a lesser extent mutant males, increased their elastic modulus and bone mineral densities to counteract changes in bone shape, but at the expense of increased brittleness. In summary, Pln deficiency alters cartilage matrix patterning and, as we now show, coordinately influences bone formation and calcification.

Keywords: Perlecan, Heparan Sulfate, Proteoglycan, Bone Quality, Schwartz-Jampel Syndrome, dyssegmental dysplasia Silverman-Handmaker

Introduction

Perlecan/Hspg2 (Pln) is a large heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycan found in the territorial matrix of mammalian cartilage as well as in basement membranes [1, 2]. Pln disappears at the chondro-osseous junction during endochondral ossification, the process underlying long bone development whereby a cartilage anlagen is replaced by bone and marrow. Deficiency of Pln in developing null mouse embryos leads to severe heart, brain, and skeletal dysplasias that are responsible for death between embryonic stage E10.5 and birth [3, 4]. In humans, functional null mutations in the PLN gene result in lethal forms of neonatal short-limbed dwarfism known as dyssegmental dysplasia Silverman-Handmaker type (DDSH) syndrome (MIM# 224410) and characterized by severe cartilage matrix anomalies. In contrast, Schwartz-Jampel syndrome type 1 (SJS1; MIM# 255800) patients affected by hypomorphic mutations in the PLN gene, display a less severe short stature phenotype accompanied by chondrodysplasias, myotonic myopathy, and facial and ocular abnormalities. The difference of severity between SJS and DDSH appears to result from variations in residual Pln expression, as no secreted Pln was detected in fibroblasts of DDSH patients and immunostaining on SJS patient’s fibroblasts showed considerable reduction of Pln within the extracellular matrix but not functional null mutation of Pln [5, 6].

Although Pln is a multifunctional extracellular proteoglycan with scaffolding properties, its best characterized function is to modulate heparin binding growth factors (HBGFs) availability during bone development [7]. In this regard, Pln NH2-terminal domain carrying HS chains can be used to engineer biomaterials capable of releasing HBGFs, such as BMPs, in a controlled manner for joint tissue repair applications [1, 8, 9].

Bone is a supercomposite material that includes a cartilaginous part and an osseous part made of an organic phase and an inorganic phase and the relative amount and structure of these two phases determines its quality. Although toughness of bone is primarily derived from the mineral phase, interactions with the organic phase are essential for its unique elastic material properties [10]. During bone development, regulated production of extracellular matrix (ECM) components establishes normal bone mass and architecture [11]. Both ECM proteins and proteoglycans present in bone have been proposed to play regulatory roles in the process of mineralization and hydroxyapatite crystal growth [12-16]. Additionally, recent studies from our laboratories proposed that Pln and its associated HS chains present at high concentrations in differentiated cartilage aid in the prevention of tissue mineralization during chondrogenesis, help maintain the pericellular space of osteocytes, and regulate solute transport and mechanosensing in adult cortical bone [2, 17, 18].

In this study, we used a viable Pln hypomorph mutant mouse model that displays a phenotype consistent with SJS patients to investigate the functional role of Pln in the regulation of bone formation and mineralization in vivo [19]. We hypothesized that absence of Pln permits premature turnover of hypertrophic cartilage to osseous bone in the growth plate, which, in turn, results in short stature and increased skeletal fragility. This idea is consistent with the abrupt loss of Pln at the chondro-osseous junction seen during normal development, and tests further the hypothesis that Pln is required for normal bone patterning during development. To test this idea, we used osteoprogenitors from Pln-deficient developing embryos and compared their differentiation potential to control cells. Additionally, we examined the consequences of Pln deficiency on bone geometry and mechanical properties in adult mice.

Methods

Animals and Statistics

Bones were obtained from Hspg2C1532Yneo homozygous (Pln mutant), heterozygous or wild type (WT) mice of the C57BL6/J background [19]. WT and heterozygous mice did not exhibit a distinct phenotype. All results are expressed as mean ±SD. Statistical comparisons between genotypes were performed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test and p values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with IACUC approved protocols.

Immunohistochemistry

Data for multilabeling were acquired by confocal microcopy as described [20]. Newborn femoral growth plate cryosections were immunostained using rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against Pln/Hspg2 (1:200 dilution; LifeSpan Biosciences Inc.), the ER marker BiP (1:400 dilution; Abcam), type X collagen (1:200, dilution, Dr. W.A. Horton, Shriners Hospital, Portland, OR) or another major proteoglycan secreted by chondrocytes, aggrecan (1:100 dilution; Millipore) as described [21]. For von Kossa staining, PN1 tibiae sections were fixed in 95% ethanol for 15 minutes and incubated in 5% (w/v) silver nitrate solution under ultra-violet light for 30 min.

Differentiation Assay

Mouse embryonic cells were isolated from E14.5 embryos obtained from Pln mutant and WT matings as described [20]. For differentiation, 2.5×105 cells were plated onto gelatinized 6-well plates (35mm) in the presence or absence of 100ng/ml BMP-2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in medium composed of DMEM (Invitrogen), 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 2mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 10-4 M β mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 5mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid, and penicillin and streptomycin at 50μg/mL each. Medium was changed every other day and alkaline phosphatase staining was performed after nine days of culture according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). For mineralization assessment, von Kossa staining was performed on day 12 cultures as indicated above for tibiae sections. Experiments were performed using quadruplate samples and were repeated three times.

Ash Content

The proximal and distal regions from six month-old Pln mutant and WT femora were cut away using a diamond saw to remove the marrow in PBS, leaving only cortical bone. The dry mass of each femur was obtained after drying at 85°C for 18 hrs. Ash weight was determined after heating individual dry bones in a furnace at 600°C for 18hrs.

Micro-Computed (μCT) Tomography

Three and six-month-old femora of the same genotype and gender were scanned simultaneously at a resolution of 27μm for 7hrs using a preclinical μCT Scanner (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp.), and images were analyzed using the GE Microview software as described [11]. To obtain bending moment of inertia, the cross-section image at the middle plane of the ROI used for μCT was converted to a binary image, and the center of mass was identified to calculate the principal moments of inertia (IAP, IML) as described [11]. The cortical width was determined by measuring the distance between eight pairs of points that were spanning the periosteal and endosteal surfaces of the cortical bone at mid-shaft.

Biomechanical Testing

Tests were performed on six month-old femora using a mechanical MicroTester (Instron 5848). Each bone was tested in a three-point bending fixture with a support span of 4.5 mm. The actuator was advanced at 0.05mm/s, compressing the bone in the anterior-posterior (AP) direction until failure as described [11]. Stiffness (S), ultimate force, and post-yield displacement (PYD) were derived from load-displacement curves and bending rigidity (EI) was calculated using S and the simply-supported beam equation as described [22]. The principle moment of inertia relative to the medial-lateral axis, (IML), was used in the calculation of the Young’s modulus (E).

Results

Effects of Pln Hypomorphic Mutation on Osteogenesis

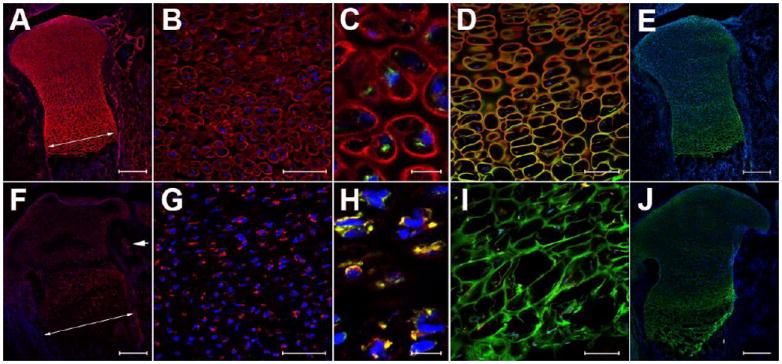

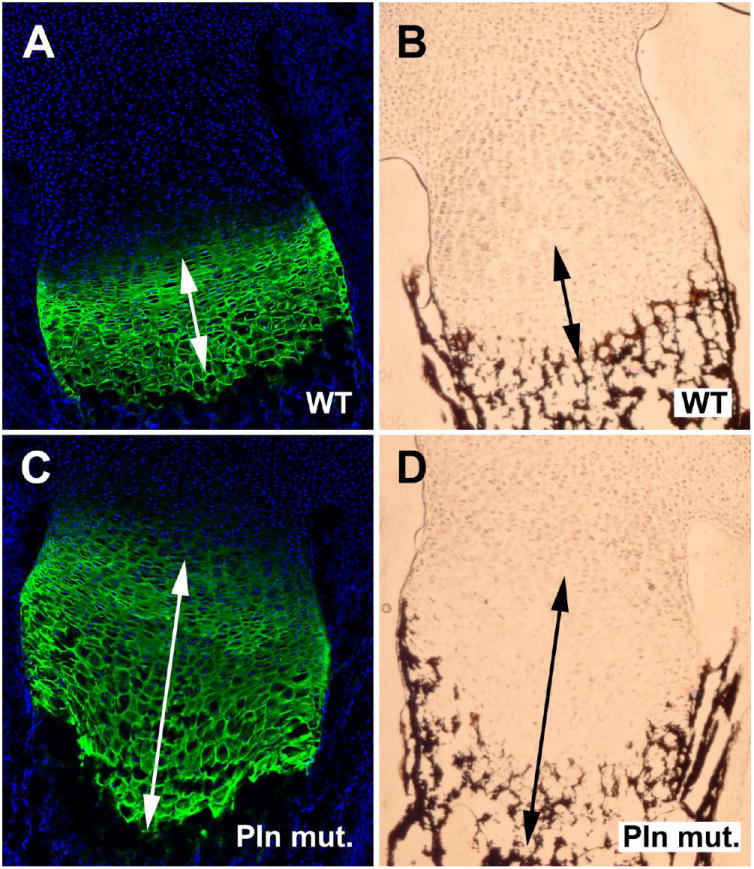

At birth, Pln mutant bones derived on the C57BL6/J background were increased in width compared with background-matched control littermates (Table 1 and compare arrows in Fig.1A&F). In addition, newborn growth plates showed a more diffuse and irregular organization of the hypertrophic zone in the Pln mutant compared to WT mice (Figs.1&2). Furthermore, the Pln mutant hypertrophic chondrocytes lack the packed and tight columnar organization of the territorial matrix seen in the hypertrophic zone of control bones (compare D and I in Fig.1). However, the most striking feature of the developing Pln mutant bones is the marked decrease of Pln-positive cartilage matrix compared to the control bones (Fig.1 compare A-C to F-H). Additionally, most of the Pln translated by the mutant chondrocytes was retained intracellularly rather than secreted pericellularly into the ECM (compare B and G in Fig.1). Pln intracellular retention in hypertrophic chondrocytes occurred in the endoplamic reticulum (ER) as demonstrated by its perinuclear co-localization with the ER chaperone, BiP (Fig.1H). Western blot analysis of protein lysates extracted from both WT and Pln mutant primary chondrocytes revealed that there is no significant change in BiP protein levels in Pln mutants versus controls (Fig.1S). The small accumulation of Pln in the ER of mutant chondrocytes did not influence secretion levels of aggrecan, another proteoglycan important in cartilage function (compare E to J in Fig.1). The absence of Pln in the extracellular matrix, however, altered overall matrix organization in the prehypertrophic and hypertrophic zones of mutant bones (compare D to I in Fig.1). Immunolocalization of type X collagen and von Kossa staining on adjacent sections of both Pln mutant and WT growth plates revealed the presence of an expanded hypertrophic zone (compare arrows in Fig.2A and C) which overlaps with mineral deposits (compare arrows in Fig.2B and D) in Pln mutants (Fig.2C-D). In contrast, WT growth plates displayed a clear demarcation at the chondro-osseous junction between the hypertrophic zone and the mineralization front (Fig.2A-B). Interestingly, analysis of postnatal growth plates revealed that the rate of proliferation in Pln mutant growth plates is decreased compared to wild type (Fig.2S). Together, these results indicate an overall decreased proliferation associated with increased terminal differentiation and calcification in mutant relative to wild type growth plates.

Table 1. Cross-sectional Cortical Properties at Femoral Mid-Shaft.

| Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| WT (n=6) | Perlecan mutants (n=6) %change vs. WT | WT (n=7) | Perlecan mutants (n=6) %change vs. WT | |

| Inner Perimeter (mm) | 4.18 (±0.13) | 4.26 (±0.23) +2.1% | 4.04 (±0.09) | 4.12 (±0.11) +2.1% |

| Outer Perimeter (mm) | 5.60 (±0.11) | 5.74 (±0.24) +2.7% | 5.25 (±0.11) | 5.63 (±0.15) +7.2% |

| Marrow Area (mm2) | 1.17 (±0.06) | 1.3 (±0.15) +10.9% | 1.18 (±0.04) | 1.22 (±0.05) +3.8% |

| Cortical Area (mm2) | 1.00 (±0.06) | 1.12 (±0.09) +12.1% | 0.87 (±0.07) | 1.12 (±0.04) +29.3% |

| Total Area (mm2) | 2.17 (±0.04) | 2.42 (±0.216) +11.5% | 2.04 (±0.08) | 2.34 (±0.06) +14.6% |

| BMD (mg/cc) | 990.8 (±28.5) | 1072.6 (±42.5) +8.3% | 984.0 (±51.6) | 1073.3 (±39.4) +9.1% |

| BMC (mg) | 0.019 (±0.002) | 0.024 (±0.002) +20.7% | 0.017 (±0.001) | 0.024 (±0.001) +40.2% |

| A/P diameter (mm) | 1.31 (±0.06) | 1.52 (±0.08) +16.2% | 1.39 (±0.05) | 1.54 (±0.07) +10.6% |

| M/L diameter (mm) | 2.10 (±0.09) | 2.02 (±0.06) -3.5% | 1.90 (±0.09) | 1.96 (±0.11) +3.6% |

| Cortical width (mm) | 0.22 (±0.02) | 0.23 (±0.01) +5.5% | 0.21 (±0.02) | 0.25 (±0.02) +19.5% |

| Ixx=IML (mm4) | 0.255 (±0.035) | 0.317 (±0.067) +24.5% | 0.235 ( ±0.053) | 0.344 (±0.063) +46.4% |

| Iyy=IAP (mm4) | 0.304 (±0.091) | 0.351 (±0.084) +15.6% | 0.211 (±0.051) | 0.291 (±0.047) +37.5% |

Bold % changes are significant, p<0.05. BMD, bone mineral density; BMC, bone mineral content; A/P, anterior-posterior; M/L, medio-lateral

Figure 1. Pln is not secreted in developing Pln mutant growth plates and co-localizes with the ER-resident protein BiP in a perinuclear intracellular compartment.

Pln (red) extracellular deposition is severely decreased in Pln mutant (F-J) versus WT (A-E). Pln signal (red) is retained intracellularly in the proliferating zone of Pln mutants (F-G) and co-localizes with BiP signal (yellow in H) whereas signals for these two proteins did not overlap in WT (Pln in red and BiP in green in C). Columnar arrangement of chondrocytes in WT prehypertrophic and hypertophic zones (D) is lost in Pln mutants (I) as indicated by the disorganized aggrecan staining of the cartilage matrix in Pln mutant growth plates (compare green in D and I). Despite changes in matrix organization the overall secretion of aggrecan remained undisturbed in mutant vs. WT growth plates (compare green in E and J). Arrow in A and F indicate an increase in the diameter of Pln mutant developing bones relative to WT. Arrowhead in F points to reduced deposition of Pln in the basement membrane of a blood vessel present in tissue surrounding developing bone. Magnification bars: 200 μm (A, E, F, J), 50 μm (B, G), 10 μm (C, H), and 100 μm (D, I). The images shown are representative of immunolabelings performed on growth plates of newborn mice (n=5 per genotype)

Figure 2. Pln mutant hypertrophic zone is disorganized and expanded.

Type X collagen (green) immunolabeled area overlaps with calcified deposits detected using the von Kossa method in mutant (C and D) but not in WT (A and B).

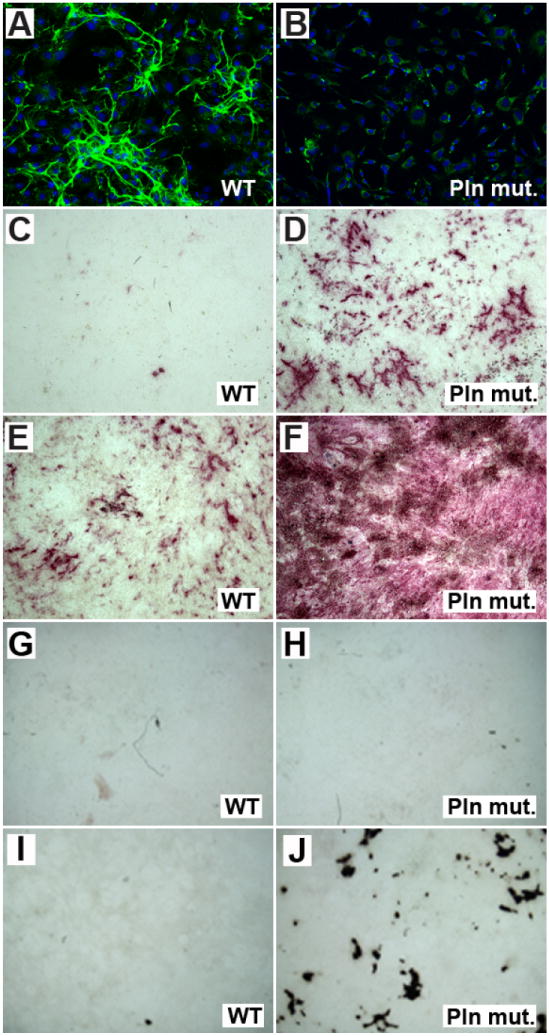

To further characterize the role played by secreted Pln during bone development, in vitro differentiation assays were conducted using primary cultures of mouse embryonic cells (Fig.3). WT cells secreted large levels of Pln extracellularly whereas Pln mutant cells only expressed small levels of Pln intracellularly (Fig.3, compare A to B). The lack of Pln secretion in Pln mutant progenitors dramatically enhanced their endogenous differentiation potential into differentiated osteoblasts when compared with control WT cells (Fig.3C-D). This observation shows for the first time that functional absence of Pln in the extracellular matrix of osteoblast progenitors is conducive to osteogenesis. This effect is even more pronounced when cells were cultured in the presence of the differentiation growth factor, BMP2 (Fig.3E-F). Moreover, terminal differentiation and mineral nodule deposition was observed in the presence of BMP2 in Pln mutant cultures but not in WT controls (Fig.3J), suggesting that the absence of Pln promotes BMP2 activity. Consistent with this data, comparison of the transcriptional profile of mouse embryonic cells revealed that markers of osteoblast differentiation such as alkaline phosphatase (Alpl), osteocalcin (Bglap1), and phosphate regulating endopeptidase homolog, X-linked (Phex), were significantly increased in BMP2-treated Pln mutant cultures relative to control cultures subjected to the same culture conditions (Fig.3S). Additionally, BMP-2 treated perlecan deficient cells secreted elevated levels of ostecalcin in the culture media compared to BMP2-treated wild type control cells (data not shown). Finally, no significant change in osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption potentials were found in Pln mutants relative to wild type controls when primary osteoclasts isolated from spleens were induced to differentiate and grown on bone slices in the presence of osteoclast differentiation media (data not shown).

Figure 3. In vitro secretion of Pln by cultured bone progenitors prevents spontaneous differentiation, and inhibits BMP2-induced differentiation into calcifying osteoblast-like cells.

Lack of extracellular expression of Pln in Pln mutants (green in B) is accompanied by increased in vitro differentiation of osteoprogenitors relative to WT (compare alkaline phosphatase activity in purple in D and C). This effect is enhanced in the presence of BMP2 (compare F to E) and in vitro mineralization can be clearly detected in Pln mutant cultures treated with BMP2 during 12 days of culture (J) whereas no mineral deposits are found in WT cultures subjected to the same culture conditions. Images representative of three biological replicates are shown.

Skeletal phenotype in Adult Pln-deficient Mice

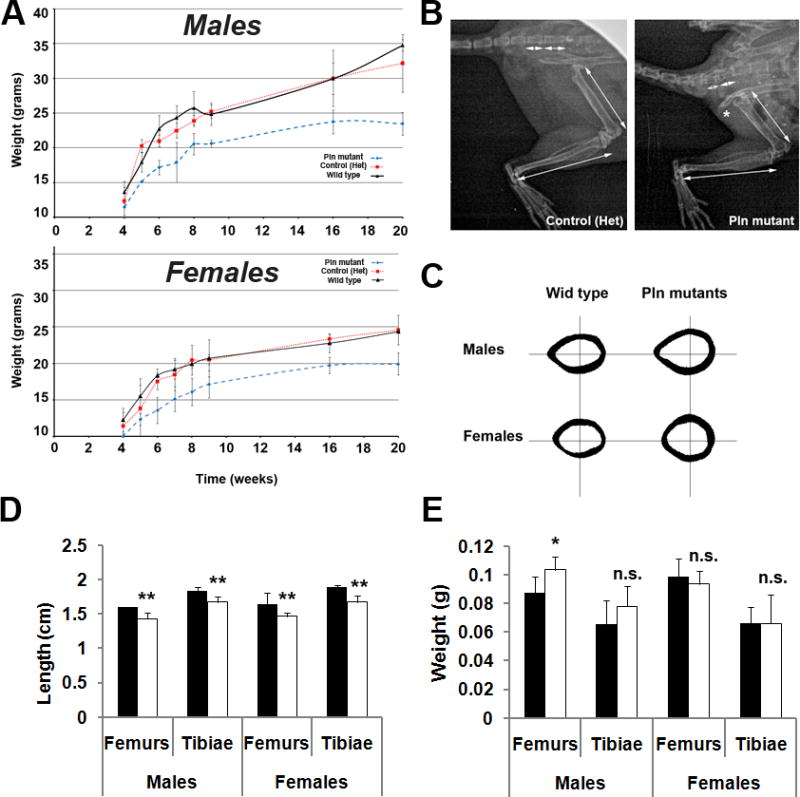

To compare the rates of growth of Pln mutant and control mice, the mouse weights were collected during post-weaning life (Fig.4A). The growth curves show that the average weight of Pln-deficient mutants diverge significantly from their wild-type and heterozygote siblings. This difference in body weight between controls and Pln mutant corresponded to an approximate 20% decrease in mutants vs. WT at 2.5 months (nine weeks) for both males (p<0.001) and females (p<0.05). Interestingly, this decrease became more pronounced and reached approximately 25% and 30% at 5-6 months (20-24 weeks) of age in males and females, respectively (p<0.001 in mutants vs. WT). Additionally, pronounced ischium/hip deformities and shortening/widening of long bones and vertebrae were apparent in Pln mutants relative to controls (Fig.4B). Interestingly, the significant decrease (-10% in mutant vs. WT, p<0.05) in the total length of Pln mutant tibiae and femora in both males and females was not accompanied by a corresponding decrease in the wet weight of mutant bones when compared with WT controls (Fig.4D&E). Analysis of mid-shaft cross-sections revealed a significant increase in bone cortical area in Pln mutants when compared to controls that was found to be more pronounced in female (+29%) vs. male (+12%) mutants (Table 1; Fig.4C). Accordingly, the outer perimeter and cortical width were also increased in Pln mutants when compared with control bones, with significant increases only in mutant females (Table 1, +7.2% and +19.5%, respectively). In contrast, the external antero-posterior (A/P) bone diameters were similarly increased in both males (+16%, p<0.05) and females (+11%, p<0.05). Nonetheless, the M/L and A/P moments of inertia (IML and IAP), which represent bending resistance, were significantly increased exclusively in females (IML, +46.4% and IAP, +37.5%) when compared to WT controls (Table 1; Fig.4C). Because Pln mutant bones demonstrated an increase in their ash mass/dry mass percentage (74.3%±1.6 SD, n=15) relative to WT bones (72.9%±2.7 SD; n=13) that nearly reached significance (p=0.105), the more sensitive micro-CT approach was employed to determine how Pln deficiency affects bone mineral composition. Indeed, increases in mineral density (BMD) and mineral content (BMC) in Pln mutants vs. controls were found for both females (+9.1% for BMD, 40.2% for BMC) and males (+8.3% for BMD, +20.7% for BMC) when a micro-CT analysis of cortical bone was used. Interestingly, BMD and BMC, usually lower in females relative to males in WT, were found to be identical in Pln mutant males when compared to Pln mutant females (Table 1). In contrast, no significant change in cortical bone mineral parameters was found in younger Pln mutant animals of both genders relative to gender-matched WT controls when compared at three months of age (data not shown).

Figure 4. Pln mutant display a short stature phenotype and mild skeletal deformities that are not associated with a decrease in skeletal bone mass.

Postnatal growth curves (A) of WT, heterozygous, and Pln mutant littermates (n≥5 for each genotype). Pln mutants display a considerable growth deficiency when compared with WT and heterozygous controls of the same gender. Representative x-ray image areas of skeletally mature (control) and age-matched mutant hindlimbs (B) showed diminished length of long bones and vertebrae in Pln mutants vs. controls (see arrows). * in B indicates deformity of the ischium in Pln mutants. Mid-diaphyseal cross-sections at mid-shaft showed an increase in the bone area of mutant animals compared to gender-matched controls that was more pronounced in females than in males (C). Bone measurements showed significant decrease in Pln mutant bone length relative to wild type in all long bones examined regardless of gender (D). In contrast, wet bone weight was only significantly increased in Pln mutant male femora compared to wild type male femora (E). ***, **, and * indicate significant differences (p<0.001, p<0.01, and p<0.05, respectively) in Pln mutant relative to controls.

Mechanical Testing of Pln-deficient bones

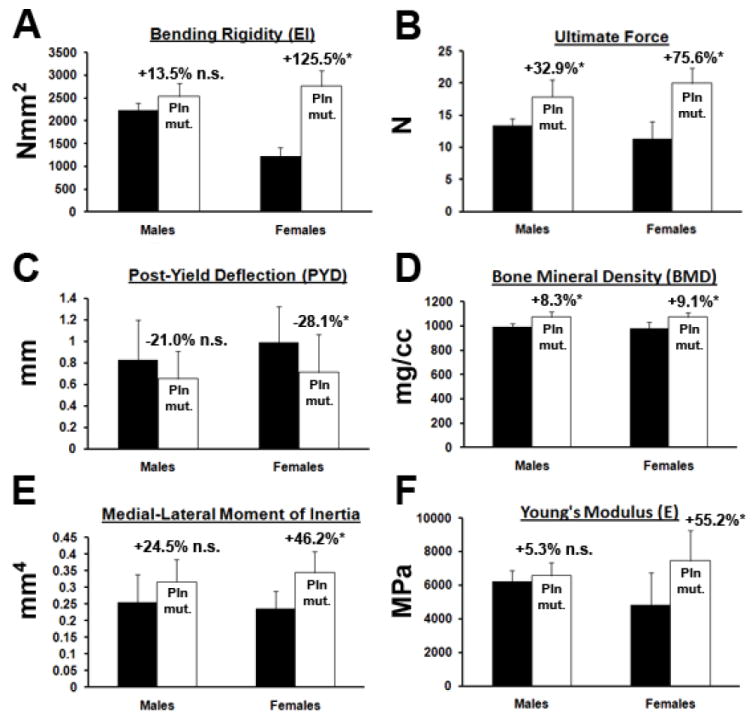

Whereas Pln-deficient femora bending rigidity was hardly increased in males, their strength was elevated by approximately 2-fold in females relative to age-matched controls (Fig.5A, +125%, p<0.05). As expected from changes in geometrical properties, both males and females mutant bones demonstrated a significant increase in ultimate force relative to controls (Fig.5B). Yet, elevated structural properties at mid-shaft allowed Pln mutant females to withstand higher forces than Pln mutant males vs. WT controls (+75.6% and +32.9%, respectively, p<0.05). These results are in agreement with the more pronounced structural changes seen in mutant female cortical bones when compared to mutant males. In addition, increased cortical BMD in Pln mutants resulted in higher energy to bend them to failure when compared to controls (Table 1, Fig.5D). Whereas, the post-yield deflection (PYD) was not significantly altered in males, female’s PYD was significant smaller (Fig.5C). Only females displayed a significantly higher elastic modulus (E) vs. controls (Fig.5F, +55.2%, p<0.05).

Figure 5. High bone mineral density in Pln mutant bones is associated with increased brittleness.

Bending rigidity (EI), ultimate force, and PYD of Pln mutant and WT femurs were obtained from three-point-bending deformation curves. BMD and medial-lateral moment of inertia (IML) were obtained from μCT scans. Young’s moduli (E) were calculated using EI and IML. Changes in bone material properties are more pronounced in Pln mutant females than in Pln mutant males when compared to gender-matched controls. *p<0.05, n≥6; n.s. non significant.

Discussion

Whereas functional null mutations of the Pln/Hspg2 gene were reported to develop severe chondrodysplasias, the phenotype of mice expressing reduced amounts of Pln resembles SJS patients and displays growth plate defects, short stature, distinct facial features and other progressive skeletal defects [3, 4, 19]. A consequence of Pln/Hspg2 gene mutation is the disorganization of the chondrocytic columnar arrangement and expansion of the hypertrophic zone in Pln mutants relative to controls. The lack of upregulation of BiP in mutant chondrocytes indicates that it is unlikely that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and the unfolded protein response (UPR) occur as a result of Pln retention in the ER of mutant chondrocytes. In addition, the residual amounts of Pln in the ER of mutant chondrocytes did not influence secretion levels of other proteoglycans important in cartilage function such as aggrecan. Thus, the observed disorganization of mutant growth plates is believed to be directly associated with the lack of Pln secretion in the cartilage matrix of mutant bones rather than an abnormal retention of Pln in the ER. This phenotype is fully consistent with previous observations and confirms that mice with hypomorphic mutations in the Pln/Hspg2 gene are viable and can be used as preclinical models to study Pln function during skeletogenesis and bone aging disease such as osteoporosis and osteoarthritis [19]. Because osteoprogenitors that do not secrete large amounts of Pln in the extracellular space were found to have an increased potential to differentiate, we suggest that the observed in vitro phenotype results from the unleashing of HBGFs that are normally sequestered by HS chains present in the extracellular matrix. Similarly, during endochondral ossification the altered organization of the chondrocyte territorial matrix observed in the absence of Pln may allow increased diffusion of HBGFs from the periosteal compartment, a signal that is eventually associated with enhanced bone formation and mineral apposition. This idea is consistent with the established function of HSPGs in the establishment of HBGF gradients as well as Pln preferential and elevated expression at interfaces where a barrier is required (i.e., basement membranes, chondro-osseous junction in the growth plate) [2, 17]. In other loss-of-function models of proteoglycan function, the absence of biglycan and decorin in developing bone prevented TGF-β from proper sequestration within the ECM and enhanced interaction with its signaling receptors [23]. Similarly, excess of unbound BMP2 in developing Pln mutant bone may overactivate signaling pathways in progenitors and enhance terminal differentiation and mineralization. Consistent with this idea, proteoglycans and HS can function as potent inhibitors of hydroxyapatite formation [24, 25]. Interestingly, reduced levels of Pln also were found to be associated with vascular calcification of smooth muscle cells in the aorta of an experimental rat model [26], suggesting that Pln interaction with factors that promote calcification can protect various tissue types from pathological mineralization. Furthermore, recent data consistent with this study showed that Pln deficiency is associated with a decrease in osteocytes’ pericellular space which suggested that Pln and its HS chains prevent tissue mineralization [17]. Additionally, Pln was found to interact directly with calcium phosphate mineral in bovine bone extracts [27]. Thus, we propose that the lack of Pln secretion in developing Pln hypomorph bones increases mineralization due to elevated availability of unbound HBGFs that, in turn, is associated with bone widening/shortening.

We demonstrated that adult Pln mutant mice exhibit dwarfism with severe spine deformity, facial flattening, deformation of the hip, and long bone widening and shortening with no concomitant bone weight decrease. A recent study from our group that used 3.5-month-old mice of the same model demonstrated that Pln mutant bones did not respond to the same extent as age-matched controls when subjected to tibial axial loading due to reduced mechanosensation by the compromised pericellular matrix of Pln mutant osteocytes [18]. These data as well as previous work from others provide strong genetic evidence that Pln is essential for normal skeletal patterning and also plays an important function in the maintenance of skeletal integrity and response to load during adulthood [3, 19, 28]. Additionally, even though only residual levels of Pln are secreted in developing bones, the presence of reduced amounts of Pln in basement membranes of Pln mutant tissues (heart, kidney and skeletal muscles) is sufficient to prevent perinatal lethality and to allow mutants to reach adulthood [19, 28]. These observations are consistent with the skeletal phenotype of SJS type 1 patients [5].

While both male and female bones were significantly shorter and displayed increased cross-sectional parameters relative to controls, the periosteal expansion was more severe in females relative to males. Although gender influenced the genotype effect on cortical bone parameters the mechanisms involved are currently unknown. Gender-specific effects are typically observed at skeletal maturity and male bones are known to have better adaptation capacities than female bones [29]. In the current study, increase in cortical bone mineral content was more pronounced in Pln mutant females than in Pln mutant males. A gender-specific bone phenotype was also found in mutant mice displaying a loss-of-function mutation in the biglycan (Bgn) gene encoding for a proteoglycan involved in the differentiation of osteoblast precursor cells [13]. In contrast to the Bgn gene, the Pln/Hspg2 gene does not lie on one of the two sexual chromosomes, and the cause of sexual dimorphism observed in this study will require further investigations.

As predicted from cross-sectional geometrical parameters, Pln mutant female bones failed under significantly higher loads, displayed significantly reduced PYD, and greater elastic modulus than Pln mutant male bones. This result is consistent with increased cortical BMD when compared to controls and indicates that Pln mutant female bones became more brittle. In contrast, Pln mutant male bones displayed compensable bending rigidity during elastic deformation and non-significant change in both PYD and E when compared to controls. Other studies with genetic models displaying a short stature phenotype due to growth plate anomalies also demonstrated that males were able to restore overall bone stiffness to control levels in the femur whereas females were not [11, 13]. Thus, in males elevated BMD is believed to compensate for decreased geometry while preserving cortical bone structural integrity.

Bone microarchitecture and composition are known to be co-regulated during bone formation in order to produce adequate mechanical properties that are well adapted for future load conditions [30, 31]. Thus, genetic perturbation altering Pln secretion in the cartilage matrix that serves as a template for bone formation leads to dwarfism and suboptimal bone quality in adults. Dysregulation of bone morphogens availability due to absence of Pln in the developing cartilage matrix may explain alteration in adult bone mechanical properties. Increase of material properties via mineralization to compensate for decreased geometric properties is not new and is observed in many other models often at the expense of bone quality [11, 13, 32]. Although stiffness in three-point-bending is closely correlated to mineralization, the control of collagen fiber orientation and cross-linking by non-collagenous proteins such as HSPGs can also contribute to overall changes in bone material properties. Additionally, HSPGs are believed to play a direct role in biomineralization as inhibitors and differential expression in females may result in regulation of mineral growth and crystallinity. Gender-specific variations in bone mineral properties have been reported in other genetically-altered mouse models such as estrogen-receptor β or androgen-receptor deficient mice, but these molecules are responsible for interactions with sex hormones so gender effects are expected [33, 34]. Recent work performed in skin tissues demonstrated that a severe reduction of Pln expression occurs specifically in aging women epidermis but not age-matched men [35]. Previous studies performed in mouse blastocysts showed that Pln expression increased with acquisition of attachment competence as a result of estrogen stimulation [36]. Such studies support the idea that gene expression of Pln may be regulated by estrogen and that gender-specific response in Pln mutant bones is somehow connected to sex hormone signaling, a possibility which will require further studies.

In conclusion, our results show that, severe reduction of Pln is primarily associated with increased osteogenesis and an enhanced bone mineralization phenotype. The decrease in adult Pln mutant bone quality indicates that Pln-deficient mice constitute a unique model for understanding the relationship between regulation of growth factor signaling by matrix components and risk for bone fracture.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the NIH through P20-RR016458 (to C.B.K.S. & M.C. F.C. & L.W) and ARRA supplement (to C.B.K.S.), and NIH R01 AR054385 (to L.W.). The C1532Yneo mutant mice were provided by Dr. K.D. Rodgers. We thank Dr. W.R. Thompson for fruitful comments on Pln function in bone matrix.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.French MM, Smith SE, Akanbi K, Sanford T, Hecht J, Farach-Carson MC, Carson DD. Expression of the heparan sulfate proteoglycan, perlecan, during mouse embryogenesis and perlecan chondrogenic activity in vitro. The Journal of cell biology. 1999;145:1103–1115. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown AJ, Alicknavitch M, D’Souza SS, Daikoku T, Kirn-Safran CB, Marchetti D, Carson DD, Farach-Carson MC. Heparanase expression and activity influences chondrogenic and osteogenic processes during endochondral bone formation. Bone. 2008;43:689–699. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arikawa-Hirasawa E, Watanabe H, Takami H, Hassell JR, Yamada Y. Perlecan is essential for cartilage and cephalic development. Nature genetics. 1999;23:354–358. doi: 10.1038/15537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costell M, Gustafsson E, Aszodi A, Morgelin M, Bloch W, Hunziker E, Addicks K, Timpl R, Fassler R. Perlecan maintains the integrity of cartilage and some basement membranes. The Journal of cell biology. 1999;147:1109–1122. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stum M, Davoine CS, Vicart S, Guillot-Noel L, Topaloglu H, Carod-Artal FJ, Kayserili H, Hentati F, Merlini L, Urtizberea JA, Hammouda el H, Quan PC, Fontaine B, Nicole S. Spectrum of HSPG2 (Perlecan) mutations in patients with Schwartz-Jampel syndrome. Human mutation. 2006;27:1082–1091. doi: 10.1002/humu.20388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arikawa-Hirasawa E, Wilcox WR, Le AH, Silverman N, Govindraj P, Hassell JR, Yamada Y. Dyssegmental dysplasia, Silverman-Handmaker type, is caused by functional null mutations of the perlecan gene. Nature genetics. 2001;27:431–434. doi: 10.1038/86941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farach-Carson MC, Carson DD. Perlecan--a multifunctional extracellular proteoglycan scaffold. Glycobiology. 2007;17:897–905. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang W, Gomes RR, Brown AJ, Burdett AR, Alicknavitch M, Farach-Carson MC, Carson DD. Chondrogenic differentiation on perlecan domain I, collagen II, and bone morphogenetic protein-2-based matrices. Tissue engineering. 2006;12:2009–2024. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jha AK, Yang W, Kirn-Safran CB, Farach-Carson MC, Jia X. Perlecan domain I-conjugated, hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel particles for enhanced chondrogenic differentiation via BMP-2 release. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6964–6975. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burstein AH, Zika JM, Heiple KG, Klein L. Contribution of collagen and mineral to the elastic-plastic properties of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:956–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oristian DS, Sloofman LG, Zhou X, Wang L, Farach-Carson MC, Kirn-Safran CB. Ribosomal protein L29/HIP deficiency delays osteogenesis and increases fragility of adult bone in mice. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:28–35. doi: 10.1002/jor.20706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ling Y, Rios HF, Myers ER, Lu Y, Feng JQ, Boskey AL. DMP1 depletion decreases bone mineralization in vivo: an FTIR imaging analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2169–2177. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace JM, Rajachar RM, Chen XD, Shi S, Allen MR, Bloomfield SA, Les CM, Robey PG, Young MF, Kohn DH. The mechanical phenotype of biglycan-deficient mice is bone- and gender-specific. Bone. 2006;39:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.12.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boskey AL, Spevak L, Paschalis E, Doty SB, McKee MD. Osteopontin deficiency increases mineral content and mineral crystallinity in mouse bone. Calcified tissue international. 2002;71:145–154. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-1121-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boskey AL, Spevak L, Doty SB, Rosenberg L. Effects of bone CS-proteoglycans, DS-decorin, and DS-biglycan on hydroxyapatite formation in a gelatin gel. Calcified tissue international. 1997;61:298–305. doi: 10.1007/s002239900339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller E, Delos D, Baldini T, Wright TM, Pleshko Camacho N. Abnormal mineral-matrix interactions are a significant contributor to fragility in oim/oim bone. Calcified tissue international. 2007;81:206–214. doi: 10.1007/s00223-007-9045-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson WR, Modla S, Grindel BJ, Czymmek KJ, Kirn-Safran CB, Wang L, Duncan RL, Farach-Carson MC. Perlecan/Hspg2 Deficiency Alters the Pericellular Space of the Lacuno-Canalicular System Surrounding Osteocytic Processes in Cortical Bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang B, Lai X, Price C, Thompson WR, Li W, Quabili TR, Tseng WJ, Liu XS, Zhang H, Pan J, Kirn-Safran CB, Farach-Carson MC, Wang L. Perlecan-containing pericellular matrix regulates solute transport and mechanosensing within the osteocyte lacunar-canalicular system. J Bone Miner Res. 2013 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodgers KD, Sasaki T, Aszodi A, Jacenko O. Reduced perlecan in mice results in chondrodysplasia resembling Schwartz-Jampel syndrome. Human molecular genetics. 2007;16:515–528. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirn-Safran CB, Oristian DS, Focht RJ, Parker SG, Vivian JL, Carson DD. Global growth deficiencies in mice lacking the ribosomal protein HIP/RPL29. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:447–460. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller SA, Brown AJ, Farach-Carson MC, Kirn-Safran CB. HIP/RPL29 down-regulation accompanies terminal chondrocyte differentiation. Differentiation; research in biological diversity. 2003;71:322–336. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2003.7106002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schriefer JL, Robling AG, Warden SJ, Fournier AJ, Mason JJ, Turner CH. A comparison of mechanical properties derived from multiple skeletal sites in mice. Journal of biomechanics. 2005;38:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bi Y, Stuelten CH, Kilts T, Wadhwa S, Iozzo RV, Robey PG, Chen XD, Young MF. Extracellular matrix proteoglycans control the fate of bone marrow stromal cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:30481–30489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen CC, Boskey AL. Mechanisms of proteoglycan inhibition of hydroxyapatite growth. Calcified tissue international. 1985;37:395–400. doi: 10.1007/BF02553709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rees SG, Shellis RP, Embery G. Inhibition of hydroxyapatite crystal growth by bone proteoglycans and proteoglycan components. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2002;292:727–733. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shibata M, Shigematsu T, Hatamura I, Saji F, Mune S, Kunimoto K, Hanba Y, Shiizaki K, Sakaguchi T, Negi S. Reduced expression of perlecan in the aorta of secondary hyperparathyroidism model rats with medial calcification. Renal failure. 2010;32:214–223. doi: 10.3109/08860220903367544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou HY. Proteomic analysis of hydroxyapatite interaction proteins in bone. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1116:323–326. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stum M, Girard E, Bangratz M, Bernard V, Herbin M, Vignaud A, Ferry A, Davoine CS, Echaniz-Laguna A, Rene F, Marcel C, Molgo J, Fontaine B, Krejci E, Nicole S. Evidence of a dosage effect and a physiological endplate acetylcholinesterase deficiency in the first mouse models mimicking Schwartz-Jampel syndrome neuromyotonia. Human molecular genetics. 2008;17:3166–3179. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallace JM, Rajachar RM, Allen MR, Bloomfield SA, Robey PG, Young MF, Kohn DH. Exercise-induced changes in the cortical bone of growing mice are bone- and gender-specific. Bone. 2007;40:1120–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price C, Herman BC, Lufkin T, Goldman HM, Jepsen KJ. Genetic variation in bone growth patterns defines adult mouse bone fragility. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1983–1991. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jepsen KJ, Pennington DE, Lee YL, Warman M, Nadeau J. Bone brittleness varies with genetic background in A/J and C57BL/6J inbred mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1854–1862. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.10.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maloul A, Rossmeier K, Mikic B, Pogue V, Battaglia T. Geometric and material contributions to whole bone structural behavior in GDF-7-deficient mice. Connective tissue research. 2006;47:157–162. doi: 10.1080/03008200600719142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiren KM, Zhang XW, Toombs AR, Kasparcova V, Gentile MA, Harada S, Jepsen KJ. Targeted overexpression of androgen receptor in osteoblasts: unexpected complex bone phenotype in growing animals. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3507–3522. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sims NA, Dupont S, Krust A, Clement-Lacroix P, Minet D, Resche-Rigon M, Gaillard-Kelly M, Baron R. Deletion of estrogen receptors reveals a regulatory role for estrogen receptors-beta in bone remodeling in females but not in males. Bone. 2002;30:18–25. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00643-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oh JH, Kim YK, Jung JY, Shin JE, Chung JH. Changes in glycosaminoglycans and related proteoglycans in intrinsically aged human skin in vivo. Experimental dermatology. 2011;20:454–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith SE, French MM, Julian J, Paria BC, Dey SK, Carson DD. Expression of heparan sulfate proteoglycan (perlecan) in the mouse blastocyst is regulated during normal and delayed implantation. Developmental biology. 1997;184:38–47. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.