Abstract

Many viral structural proteins and their truncated domains share a common feature of homotypic interaction forming dimers, trimers, and/or oligomers with various valences. We reported previously a simple strategy for construction of linear and network polymers through the dimerization feature of viral proteins for vaccine development. In this study, technologies were developed to produce more sophisticated polyvalent complexes through both the dimerization and oligomerization natures of viral antigens. As proof of concept, branched-linear and agglomerate polymers were made via fusions of the dimeric glutathione-s-transferase (GST) with either a tetrameric hepatitis E virus (HEV) protruding protein or a 24-meric norovirus (NoV) protruding protein. Furthermore, a monomeric antigen, either the M2e epitope of influenza A virus or the VP8* antigen of rotavirus, was inserted and displayed by the polymer platform. All resulting polymers were easily produced in E. coli at high yields. Immunization of mice showed that the polymer vaccines induced significantly higher specific humoral and T cell responses than those induced by the dimeric antigens. Additional evidence in supporting use of polymer vaccines included the significantly higher neutralization activity and protective immunity of the polymer vaccines against the corresponding viruses than those of the dimer vaccines. Thus, our technology for production of polymers containing different viral antigens offers a strategy for vaccine development against infectious pathogens and their associated diseases.

Keywords: branched-linear complex, agglomerate complexes, immune response, vaccine development, vaccine platform, norovirus vaccine, hepatitis E virus vaccine, flu vaccine

1. Introduction

Biomaterials have emerged as a promising and important field that may have wide applications in healthcare of twenty-first century. One such application is development of recombinant antigen complexes as non-replicating subunit vaccines to control and prevent infectious diseases that lead to hundreds of thousand deaths worldwide each year. Through various technologies, small antigens or epitopes of infectious pathogens having low immunogenicity can assemble into large polyvalent complexes with high immunogenicity that can be further developed into effective vaccines. Production of these recombinant protein-based subunit vaccines does not contain an infectious agent and therefore, such non-replicating vaccines may be safer than those developed from a conventional vaccine strategy that relies on cultured viruses. Several subunit vaccines have been commercially available for human use [1], including the VLP vaccines against hepatitis B virus (HBV) [2, 3], human papilloma virus (HPV) [4–7], and hepatitis E virus (HEV) [8, 9]. Furthermore, two other subunit vaccines have been developed for use in domestic pigs against porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) infection and diseases [10, 11]. In addition, numerous reports in the literatures have indicated that many other subunit vaccines are under clinical and preclinical evaluations (reviewed in [1, 12]). Hence, recombinant protein-based subunit vaccines denote a strategy to combat infectious diseases.

Many neutralizing antigens and epitopes, usually identified on large surface proteins of some pathogens, have been defined as the result of extensive characterizations of these pathogens. These defined antigens and epitopes have generally low immunogenic capability due to their small sizes and low valence. Thus, improvement of their immunogenicity is the key to turn the antigens and epitopes into effective vaccines, which can be achieved by a conjugation of the antigens/epitopes to a large polyvalent platform, such as a virus-like particles (VLPs) (reviewed in [1, 12]). In our previous studies [13, 14], two types of polyvalent complexes, linear and network, were developed to turn the small dimeric viral antigens into large, polyvalent complexes with significantly improved immunogenicity. These polymers can also function as vaccine platforms for presentation of monomeric antigens [14]. Thus, the polyvalent complexes offer a strategy for subunit vaccine development.

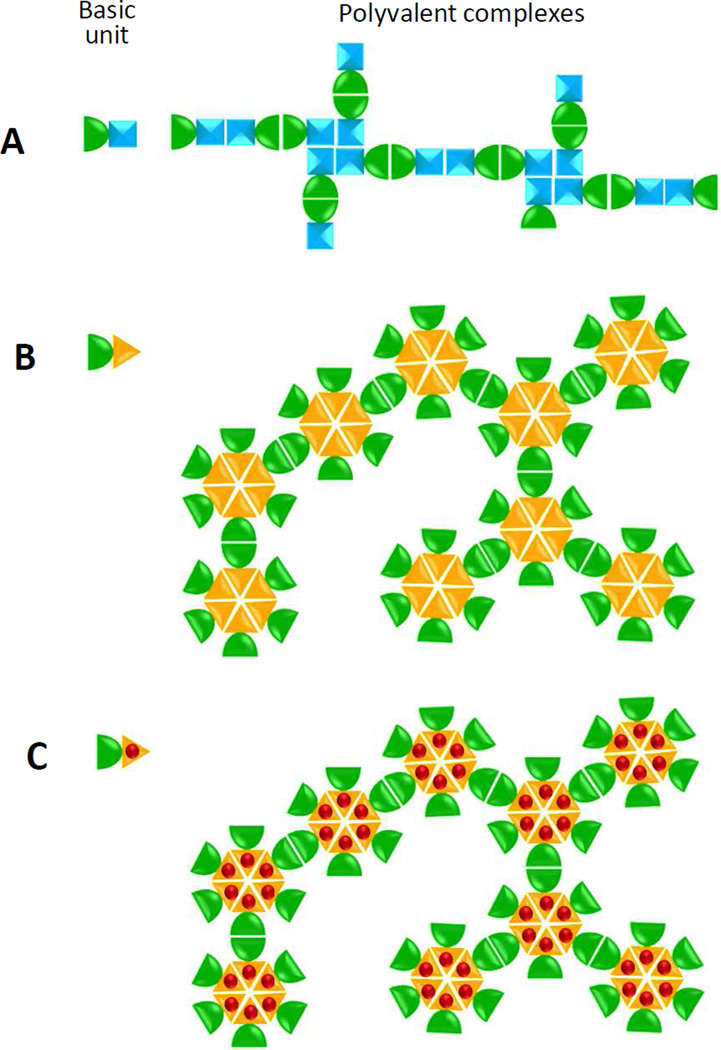

Based on the principle of the linear and network polymer formation [13, 14], two more sophisticated polymers were designed and constructed through introduction of oligomeric proteins into the basic fusion protein unit (Figure 1). Branched-linear polymers assemble when a dimeric protein is fused with a dimeric and tetrameric protein (Figure 1A), while agglomerate polymers form when a dimeric protein is fused with a multimeric protein (Figure 1B). The immunogenicity of the two polymers should be improved owing to their significantly increased valency and complexity compared with those of dimers or oligomers. In addition, a monomeric antigen can be inserted into the polymers through a surface loop of a polymer component (Figure 1C) for increased immunogenicity.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the principles of branched-linear and agglomerate polymer formations and the application of the agglomerate complex as a platform for antigen display. (A) Branched-linear polymer formation. Fusion of a dimeric protein (left, green half oval) with a dimeric/tetrameric protein (left, cyan square) forms in a branched-linear polymer (right). The linear portion of the polymer is formed by homotypic dimerizations of the two proteins, respectively, (ovals and double squares), while the branchings are formed by tetramerization of the tetrameric protein (tetra-squares). (B) Agglomerate polymer formation. Fusion of a dimeric protein (left, green half oval) with an oligomeric protein (left, yellow triangle) forms an agglomerate polymer (right) through intermolecular dimerization (green ovals) and oligomerization (yellow hexagon) of the two protein components. In both (A) and (B) only small portions of the large branched-linear (A) and agglomerate (B) polymers are shown for clarity, while the actual polymers are much more complex. The oligomers in (B) are shown in a cross-sectional view, while they may be spherical in the actual agglomerate polymers. (C) A monomeric antigen (red ball) can be inserted into the surface of a component of the fusion protein unit (left). Through formation of the agglomerate polymers, the inserted antigen becomes polyvalent in the polymer (right).

The feasibility of the proposed polymer formations will be examined using the dimeric glutathione S-transferase (GST) of Schistosoma japonicum [15], the modified protruding (P) domain of HEV (forming dimers and tetramers, [16] and this report), and the modified P domain of norovirus (NoV, forming 24mer) [17, 18] as models. Additionally, the monomeric M2e epitope of influenza A virus (IAV) [19] and the VP8* antigen of rotavirus (RV) [20] will be used to examine the capability of the polymers as vaccine platforms. Except for GST that is also a commonly used tag for protein purification; the other four are well-defined neutralizing antigens and epitopes of the corresponding viral pathogens that cause significant morbidity and mortality worldwide.

We hypothesize that fusion of the dimeric GST with the dimeric/tetrameric HEV P protein will lead to formation of branched-linear polymers, while fusion of GST with the multimeric NoV P protein will form agglomerate complexes. Monomeric M2e epitope or VP8* antigen will be displayed well by the agglomerate complexes. The polymers will assemble spontaneously when the fusion proteins are produced and purified from E. coli. Most importantly, we anticipate that the resulting polymers will induce strong humoral and cellular immune responses, neutralize virus replication in cell culture, and protect vaccinated animals against virus challenge and thus are promising vaccines against the four viruses. Data from this study will prove the concept of the branched-linear and agglomerate polymers as vaccines and vaccine platforms that may find broad applications in biomedicine.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Plasmid constructs

The plasmid constructs for expression of recombinant fusion proteins were created through the glutathione S-transferase (GST)-gene fusion system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) using the vector pGEX-4T-1. For expression of the fusion protein of GST with a modified P protein of HEV (GST-HEV P+), a plasmid was constructed by inserting the partial P1 and P2 domain-encoding sequences (residue 452 to 617, GenBank AC#: DQ079627) of a genotype 3 HEV [16, 21] into the pGEX-4T-1 plasmid between BamH I and Not I sites. A short peptide containing cysteines (CDCRGDCFC) was added to the C-terminus of the HEV P to stabilize the fusion protein and to increase the interaction between the HEV P+ proteins. The DNA sequences were synthesized chemically by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). For expression of the fusion protein of GST with a modified NoV P domain (GST-NoV P+), the P domain of a NoV (VA387,GII.4) with the same cysteine-containing peptide (CDCRGDCFC) at C-terminus was cloned into the pGEX-4T-1 vector, as described previously [18]. There is a thrombin recognition site between the GST and the HEV P+ or NoV P+ that allows a release of the HEV P+ or NoV P+ from GST. The expression constructs of GST-NoV P+-VP8* and GST-NoV P+-M2e, each having the VP8* antigen of RV or the M2e epitope of IAV at loop 2 of NoV P domain [20, 22], were made by cloning the PCR-amplified sequences of NoV P+s with M2e or VP8* at loop 2 from previously made constructs [19, 20] into the vector pGEX-4T-1. Finally, the NoV P− dimers were expressed through the previous made construct that contains NoV P domain with a deletion of the C-terminal arginine-cluster [23].

2.2 Production and purification of recombinant proteins

Recombinant fusion proteins were produced in a bacteria strain BL21 (DE3) as described previously [24–26]. The fusion proteins with GST were purified through the resin of Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow medium (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. GST was removed from the P proteins by thrombin (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) cleavage.

2.3 SDS-PAGE and protein quantitation

The quality of the purified recombinant proteins was examined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) through 10% separating gels. Proteins were quantitated by SDS-PAGE using serially diluted bovine serum albumin (BSA, Bio-Rad) as standards on the same gels [20].

2.4 Gel filtration chromatography

This was performed as described elsewhere [14, 24–26] using an Akta Fast Performance Liquid Chromatography (FPLC) system (model 920, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) via a size exclusion column (Superdex 200, 10/300 GL, GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The column was calibrated using Gel Filtration Calibration Kits (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and the purified NoV P particles (~830 kDa) [25], small P particles (~420 kDa) [27] and P dimers (~69 kDa) [24] as described previously [14]. The protein identities in the peaks of interest were further characterized by SDS-PAGE.

2.5 Electron microscopy (EM)

The morphology of the protein polymers was visualized by negative-stained EM as described previously [14]. Briefly, an EM grid (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Inc) was set on a small drop (7 µl) of protein solution for 10 min in a humidified chamber. After a wash with a drop of water for a few seconds, the grid was stained with the 1% ammonium molybdate solution for 30 seconds. The air-dried grid was examined by a Phillips CM10 electron microscope operating at 80 kV.

2.6 Size distributions of polymers

These were analyzed by light scattering through the high definition digital particle size analyzer (Saturn DigiSizer 5200, Micromeritics) with measurement ranges from 100 nm to 100 µm. 1× phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH7.4) were used to prewash the instrument. The P particles with known sizes were measured by ALV DSL Compact Goniometer System-3 (CGS-3) (ALV, Langen, Germany) as controls. These services were provided by the Advanced Materials Characterization Center (AMCC, http://www.chme.uc.edu/) at the University of Cincinnati.

2.7 Enzyme immunoassay (EIA)

This was used to determine immune reactivity and antibody IgG titers of mouse antisera after immunization with different antigens, as described elsewhere [20]. Various purified antigens were used for measurements of different antisera: 1) gel-filtration purified NoV P− proteins [14] were used to measure the NoV P domain specific IgGs; 2) gel-filtration purified RV VP8* was used to measure the VP8* specific IgGs [20]; and 3) synthesized M2e peptide was used to measure the M2e specific IgGs [19]. Diluted antigens at concentration of 1 µg/ml were coated on 96-well microtiter plates (Dynex Immulon) at 4°C overnight and incubated with serially diluted antisera. Bound IgGs were measured by corresponding secondary antibody-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugates. Antibody IgG titers were defined as the end-point dilutions with a cutoff signal intensity of 0.2. Preimmune mouse sera or sera after immunization with PBS were used as negative controls.

2.8 Histo-blood group antigen (HBGA) binding and blocking assays

The saliva-based binding assays that mimic NoV-HBGA attachment were performed as described elsewhere [28, 29]. Briefly, boiled saliva samples containing defined HBGAs were coated on 96-well microtiter plates (Dynex Immulon) and incubated with NoV P protein complexes at given concentrations. The bound NoV P proteins were measured by guinea pig anti-NoV VLP antiserum (1:3300), followed by an incubation of HRP-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG (ICN Pharmaceuticals). Due to the lack of a cell culture for human NoV, NoV-HBGA blocking assay by specific antisera serves as a surrogate neutralization assay of NoVs [30–32]. The blocking effects of the mouse antisera against the binding of NoV P particles to HBGAs were determined by a pre-incubation of the P particles with serially diluted sera for 1 hour before the P particles were incubated with the coated saliva. The blocking rates were defined as reduction rates by comparing the optical density (OD) with and without blocking by the sera. The blocking titer 50 (BT50) was defined as the dilution of the antisera that produced a 50% reduction on the binding of NoV P particle to HBGAs.

2.9 Mouse immunization

Female BALB/c mice (Harlan-Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) at ages of 3–4 weeks were immunized with different polymers, respectively: 1) branched-linear polymers (GST-HEV P+), 2) agglomerate polymers (GST-NoV P+), 3) agglomerate polymers with VP8* (GST-NoV P+-VP8*), and 4) agglomerate polymers with M2e (GST-NoV P+-M2e). 5 µg/mouse of these immunogens were immunized to mice (n = 6–8 mice/group) intranasally three times without an adjuvant in two-week intervals, as described previously [14, 20]. Equal molar amounts of 1) GST + HEV P+ (1:1), 2) NoV P−, 3) NoV P−-VP8*, and 4) NoV P−-M2e were used as controls, respectively. Blood samples were collected through retro-orbital capillary plexus puncture before each immunization and two weeks after the final immunization. Sera were prepared according to a standard protocol.

2.10 HEV neutralization assay

The neutralization titers of the mouse hyperimmune sera against HEV replication in cell culture were determined as previously described [13, 33, 34] using the Kernow P6 strain of HEV (genotype 3, kindly provided by Dr. S.U. Emerson, NIAID) and HepG2/C3A cells. Approximately 50,000 HepG2/C3A cells/well were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated for 120 min with the Kernow P6 viruses (100 FFU/well) that were pre-incubated with the serially diluted mouse sera for 2 h at 37 °C. The inocula were subsequently replaced with maintenance medium and the cells were incubated for 5 days. After fixation with 80% acetone, the infected cells were stained with rabbit anti-HEV ORF2 antibody, washed with PBST (1×PBS with 0.2% tween-20), and then detected by fluorescence labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody. The stained cells were counted with a fluorescence microscope. The neutralization titers of the mouse sera were defined as the highest serum dilution that can reduce at least 60% of infected cells compared with no serum controls.

2.11 Mouse challenge model of influenza A virus (IAV)

This was used to measure the protective efficacy of a M2e vaccine against IAV infection as described elsewhere [19]. BALB/c mice (n = 8 mice/group) at age of 6 to 8 weeks (Harlan-Sprague-Dawley) were immunized with 15 µg of GST-NoV P+-M2e intranasally without an adjuvant three times at 2-week intervals. Another group of mice were immunized by equal molar amount of NoV P−-M2e as controls. Bloods were collected before and 2 weeks after each immunization. Serum antibody titers specific to M2e peptide were measured by EIA. Two weeks after the third immunization, mice were challenged with mouse adapted IAV PR8 strain (H1N1) at approximately 4 × LD50, approximately equal to 2×106 fluorescent focus forming units, in 40 µl of PBS. The challenged mice were monitored daily for changes in body weight and mortality. A group of unvaccinated and unchallenged mice were used as growth controls.

2.12 CD4+ T cell response

The established method used in our previous study [14] was adapted here. Spleens were collected from immunized mice (n=3, see above) at four weeks after the third immunization for splenocyte preparation. The splenocytes were suspended in RPMI-1640 medium with 1:1000 Brefeldin A (eBioscience) and stimulated with VP8* CD4 T cell epitopes (SDFWTAVIAVEPHVN, synthesized by GenScript) at 5 µg/ml for 6 hours in a 96-well plate at 37°C. The CD4 T epitope of VP8* was predicted by Immune Epitope Database Analysis Resource (IEDB) (http://tools.immuneepitope.org/main/). The cell surface markers CD3 and CD4 (Biolegend) were stained for 15 minutes at 4°C and the cells were fixed at 4°C overnight. For cytokine staining, cell s were washed with 1× permeabilization buffer and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated cytokine antibodies (anti-mouse IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α, Biolegend) for 30 minutes at 4°C. After being was hed with 1× permeabilization buffer, then FACS buffer (1×PBS with 1% FBS and 0.01% NaN3), cells were resuspended in FACS buffer for acquisition. All samples were analyzed on a BD Accuri™ C6 flow cytometer and data was analyzed by Accuri™ C6 software.

2.13 Statistical analysis

Statistical differences were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Differences between two data groups were evaluated using an unpaired, non-parametric t test. Comparisons of two survival curves were analyzed by Log-rank (Mantel-cox) test (Chi square). P values were set at 0.05 (*, P < 0.05) for significant difference, 0.01 (**, P < 0.01) for highly significant difference, and 0.001 (***, P<0.001) for extremely significant difference.

2.14 Ethics statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (23a) of the National Institutes of Health. The protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation (Animal Welfare Assurance no. A3108-01).

3. Results

3.1 Production of branched-linear polymers

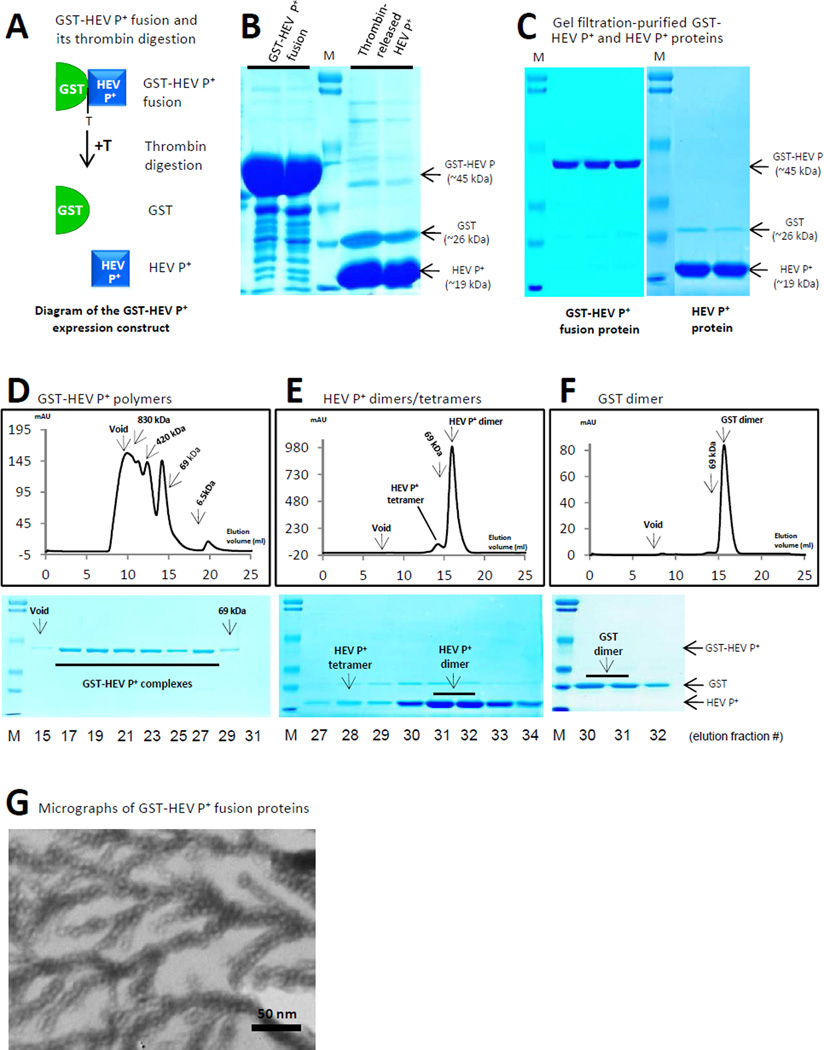

In a previous study we showed that linear complexes formed spontaneously through intermolecular dimerization when two dimeric proteins were fused together [14]. Based on this principle, we anticipated that branched-linear complexes would form when one of the two dimeric components form tetramers (Figure 1A). To test this hypothesis, dimeric GST [15] was fused with a modified HEV P protein [16]. We noted that, when a cysteine-containing peptide CDCRGDCFC was linked to the C-terminus of a truncated HEV P domain, the resulting protein, designated as HEV P+ (~19 kDa, Figure 2B and 2C), formed both dimers and tetramers as shown by the major and the minor peaks, respectively, in a gel filtration (Figure 2E). The GST-HEV P+ fusion protein (~45 kDa) can be purified at a high yield of ~25 mg/liter bacterial culture (Figure 2A to 2C). Gel filtration of GST-HEV P+ revealed large complexes ranging from ~150 kDa to void (>800 kDa) (Figure 2D). EM showed the GST-HEV P+ protein as branched-linear polymers (Figure 2G), in which the linear portions of the polymers may be formed by homotypic dimerization of GST and HEV P+ proteins, while the branchings, typically in four directions, may be formed by the tetramerization of the HEV P+ proteins (Figure 1A and 2G). As anticipated, thrombin cleavage of GST-HEV P+ protein into free GST and HEV P+ proteins completely destroyed the formation of the large polymers, resulting in GST dimers (Figure 2F, ~52 kDa) and HEV P+ dimers (~38 kDa) and tetramers (~76 kDa) (Figure 2E), respectively.

Figure 2.

Production and characterization of branched-linear polymers of GST-HEV P+. (A) Schematic illustration of GST-HEV P+ fusion and its thrombin digestion (+T) into free GST (green half oval) and HEV P+ (blue square) proteins. The thrombin digestion site (T) between the GST and the HEV P+ protein is indicated. (B) The affinity column-purified GST-HEV P+ fusion protein (left) and the thrombin released HEV P+ protein (right) were analyzed on a SDS PAGE gel. (C) The gel filtration-purified GST-HEV P+ (left) and HEV P+ (right) proteins are analyzed on SDS PAGE gels. Positions of the GST-HEV P+ fusion protein (~45 kDa), GST (~26 kDa), and HEV P+ (~19 kDa) proteins are indicated. M represents the pre-stained protein markers (Bio-Rad, low range), with bands from top to bottom representing 113, 92, 52, 34, 25, and 18 kDa, respectively. (D) to (F) Elution curves of gel filtration chromatography of the GST-HEV P+ (D), HEV P+ (E), and GST (F) proteins through the size-exclusion column (Superdex 200, 10/300 GL, GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The gel filtration column was calibrated by the Gel Filtration Calibration Kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and the purified recombinant P particles, small P particles, and P dimers of NoV (VA387). The elution positions of blue Dextran 2000 (~2000 kDa, void), P particles (~830 kDa), small P particles (420 kDa), P dimers (~69 kDa), and/or aprotinins (~6.5kDa) were indicated. The protein peaks were analyzed by SDS-PAGE shown below the corresponding elution curves of gel filtrations. Fraction #15 represents the beginning of the void volume (>800 kDa) (D), fractions #28 and #31/32 represent the peaks of the HEV P+ tetramers (~76 kDa) and dimers (~38 kDa) (E), respectively, while fractions #30/31, represent the peak of GST dimer (~56 kDa). (G) An electron micrograph of negatively stained GST-HEV P+ protein revealed branched-linear polymers.

3.2 Formation of agglomerate complexes

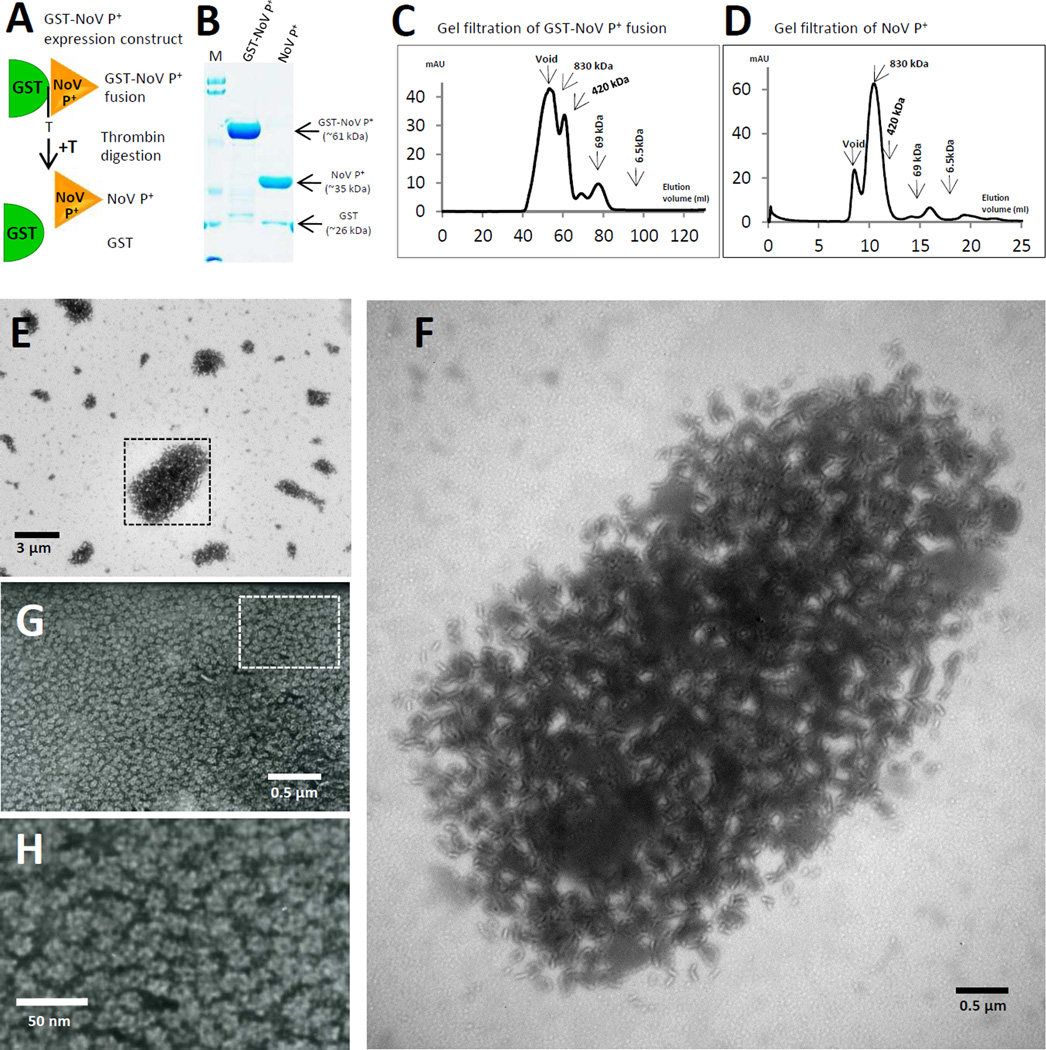

We further hypothesize that more sophisticated polymers would assemble when the HEV P+ component of the GST-HEV P+ is replaced by a multimeric protein (Figure 1B). Previous studies showed that modified NoV P domain with a C-terminal peptide CDCRGDCFC, designed as NoV P+, formed 24-meric P particles [17, 18] (Figure 3G and 3H). Fusion protein of GST with NoV P+, designated as GST-NoV P+ (Figure 3A), can be produced and purified at ~10 mg/liter bacterial culture (Figure 3B). The fusion protein formed large complexes ranging from ~500 kDa to >850 kDa (void volume) as shown by gel filtration chromatography (Figure 3C), while the thrombin-released NoV P+ formed an anticipated major peak at ~830 kDa (Figure 3D), corresponding to the 24-meric P particles [18]. EM revealed the GST-NoV P+ proteins as agglomerate polymers with variable sizes (Figure 3E), some of them measuring >10 micrometers, likely containing thousands of GST-NoV P+ units. Enlargement of a big agglomerate polymer (Figure 3F) revealed large collections of many bended lines going in all directions, which may be formed by NoV P+ oligomers (Figure 3G and H) linked by the GST dimers (Figure 1B) (see discussion).

Figure 3.

Production and Characterization of agglomerate polymers of GST-NoV P+. (A) Schematic illustration of the GST-NoV P+ fusion protein and its thrombin digestion (+T) into GST and NoV P+ protein. The thrombin digestion site (T) between the GST (green half oval) and the NoV P+ (yellow triangle) is indicated. (B) The affinity column-purified GST-NoV P+ and the thrombin released NoV P+ proteins were analyzed on a SDS PAGE. Positions of the GST-NoV P+ fusion (~61 kDa), NoV P+ (~35 kDa) and GST (~26kDa) proteins are indicated. M represents the pre-stained protein markers (Bio-Rad, low range), with bands from top to bottom representing 113, 92, 52, 34, 25, and 18 kDa, respectively. (C) and (D) The elution curves of gel filtration chromatography of the GST-NoV P+ (C) and NoV P+ (D) proteins through the size exclusion column (Superdex 200, 10/300 GL, GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The gel filtration columns were calibrated by the Gel Filtration Calibration Kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and the purified recombinant P particles, small P particles, and P dimers of NoV. The elution positions of blue Dextran 2000 (~2000 kDa, void), P particles (~830 kDa), small P particles (420 kDa), P dimers (~69 kDa), and aprotinin (~6.5kDa) were indicated. (E) to (H) Electron micrographs of negatively stained GST-NoV P+ (E and F) and NoV P+ (G and H) proteins. The GST-NoV P+ protein forms large agglomerate polymers with variable sizes (E), while the NoV P+ forms the 24-meric P particles measuring ~20 nm in diameter (G and H). A large agglomerate polymer in (E) is enlarged in (F). The rectangular labeled region in (G) is enlarged in (H) to show the morphologies of the 24mer P particles.

3.3 Size distributions of the polymers

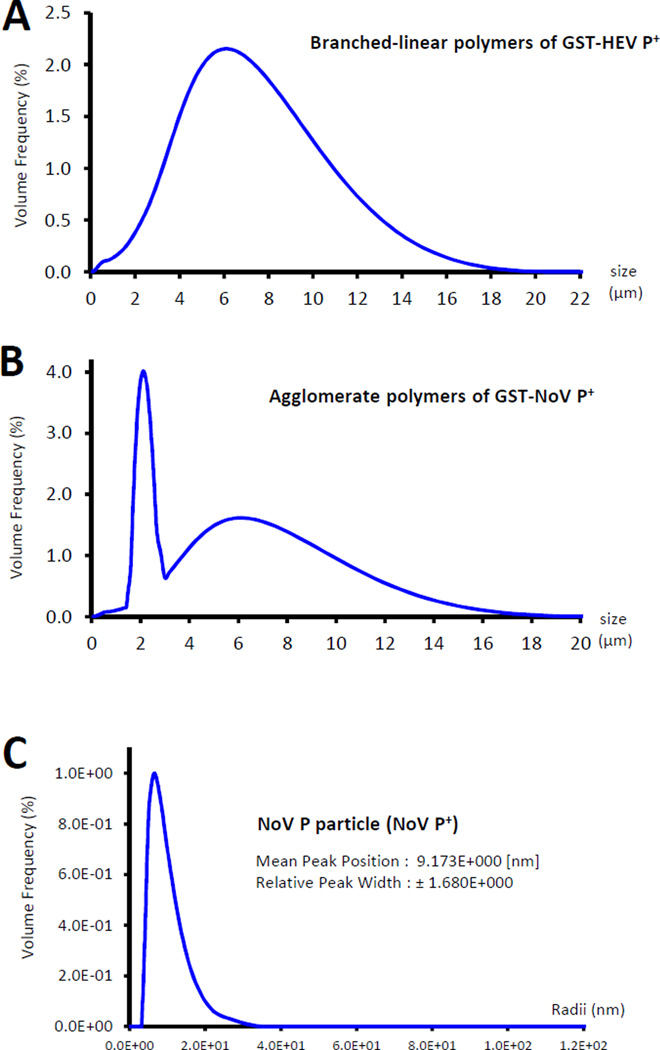

The size distributions of the two polymers were further analyzed by light scatting using a digital particle size analyzer (Saturn DigiSizer 5200, Micromeritics). Based on the volume frequency, both polymers showed wide ranges of size distributions from ~0.25 to ~17 or 19µm (Figure 4, A and B). The branched-linear polymers (GST-HEV P+) showed a median size of ~5.8 µm. The agglomerate complexes (GST-NoV P+) exhibited a major sharp peak at ~2.2 µm, while the remaining complexes exhibited a normal distribution curve with a peak at ~6.5 µm (Figure 4B). The previously characterized P particles (NoV P+, ~20 nm) [17, 18] exhibited a mean radius of ~9 nm as measured by the DSL Compact goniometer system (ALV, Langen, Germany) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Size distributions of the branched-linear and agglomerate polymers. (A and B) The size distributions of the two polymers were measured by light scatting using a high definition digital particle size analyzer (Saturn DigiSizer 5200, Micromeritics), in which the size distribution curves of the branched-linear (A) and agglomerate (B) polymers based on volume frequency are shown. The branched-linear polymers of GST-HEV P+ showed a mean size of ~5.8 µm. The agglomerate polymers of GST-NoV P+ exhibited a major sharp peak at ~2.2 µm, while the remaining complexes showed a normal distribution curve with a peak at ~6.5 µm. (C) The previously characterized P particles (NoV P+, ~20 nm) were measured by the DSL Compact goniometer system (ALV, Langen, Germany) as control.

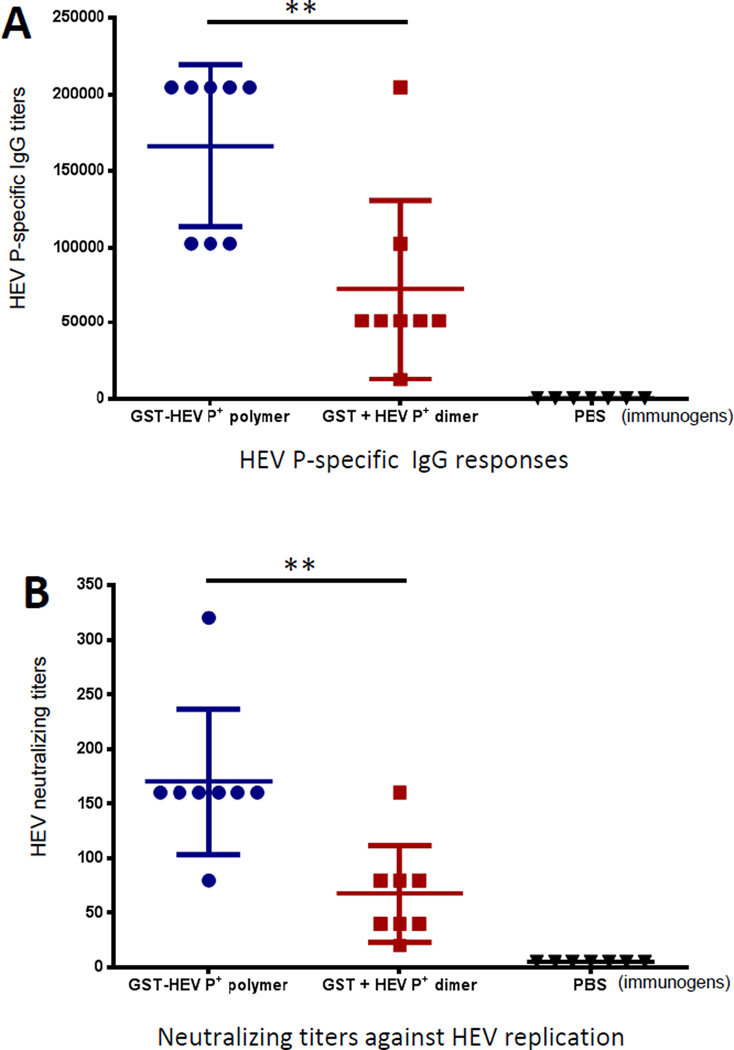

3.4 Immunogenicity of the HEV P antigen in the polymers

Mice were immunized three times with equal molar amount of GST-HEV P+ polymers and a mixture of free GST and HEV P+ proteins (1:1 in mole ratio) intranasally without an adjuvant using PBS-immunized mice as negative controls (see Materials and Methods). The resulting sera showed that the HEV P-specific antibody (IgG) titers after immunization with GST-HEV P+ polymers were significantly higher than those induced by the mixture of free GST and HEV P+ proteins (P < 0.01) (Figure 5A). The mouse antisera were further examined for their neutralization capabilities against HEV (Kernow P6 strain, genotype 3) infection in HepG2/C3A cells. The antisera after immunization with the GST-HEV P+ polymers exhibited significantly higher neutralizing antibody titers than those induced by the mixture of free GST and HEV P+ proteins (P < 0.01) (Figure 5B). These data indicated that the branched-linear polymers increased the immune responses of the HEV P antigen.

Figure 5.

The branched-linear polymers increased immunogenicity of HEV P antigen. (A) HEV P specific IgG responses after immunization. Mice were immunized with equal molar amount of GST-HEV P+ polymers and a mixture of free GST and HEV P+ proteins (GST + HEV P+, 1:1 in mole amount) intranasally three times without an adjuvant in two-week intervals (n = 8 mice/group). Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) was given as negative controls (n = 7 mice/group). (B) The resulting mouse antisera blocked HEV replication. The neutralizing titers of the resulting antisera against HEV (Kernow P6 strain, genotype 3) infection in HepG2/C3A cells were determined. ** (P < 0.01) indicates a statistically very significant difference.

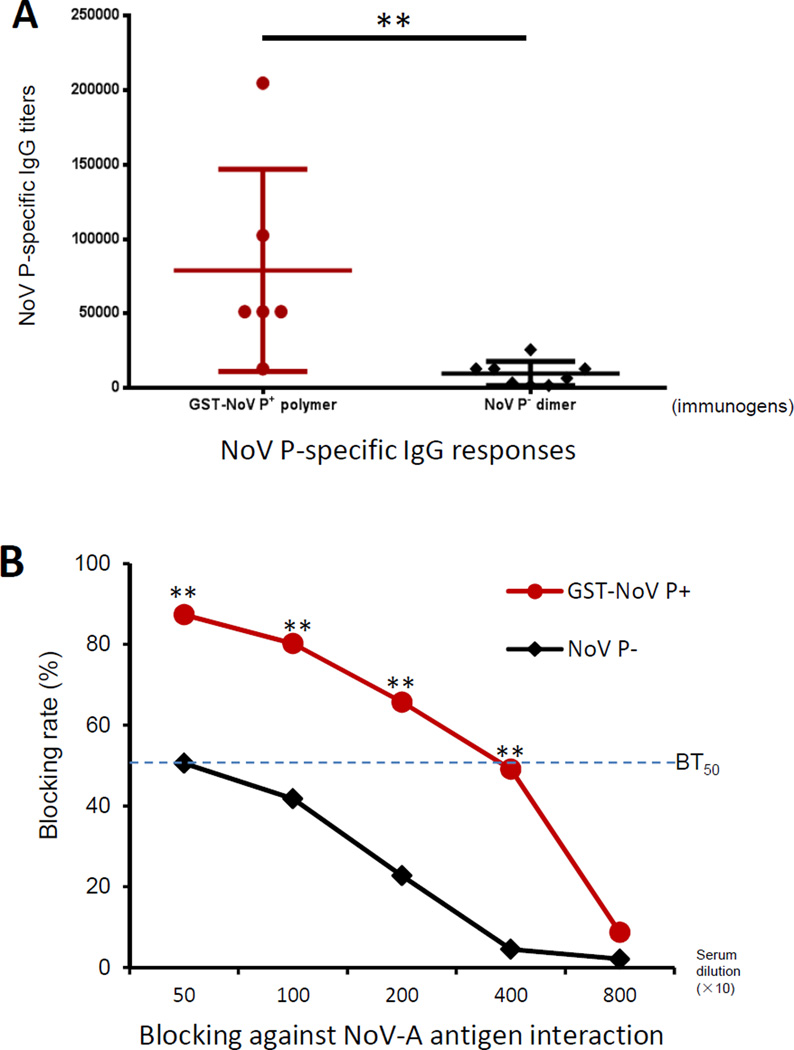

3.5 Immune response of the NoV P antigen in the complexes

Mice (n=6–8/group) were immunized with equal molar amounts of GST-NoV P+ polymers and free NoV P− dimers [23] (see Materials and Methods). NoV P-specific antibody (IgG) titers of the resulting sera were determined by EIA. Mice after immunization with the GST-NoV P+ polymers developed significantly higher IgG titers than those induced by the free dimeric NoV P− proteins (P < 0.01, Figure 6A). The mouse antisera were then evaluated for their neutralization activity through a blocking assay against attachment of NoVs to their HBGA receptors. The GST-NoV P+-induced antisera exhibited significantly higher blocking activity against the interaction of NoV particles (VA387, GII.4) with type A saliva than that of the free NoV P− dimer-induced antisera (P<0.01) (Figure 6B). The GST-NoV P+-induced antisera revealed a 50% blocking titer (BT50) of ~1:4000, eight folds higher than that of the free NoV P− dimer-induced antisera (~1:500, P<0.01). Thus, the agglomerate polymers significantly increased the immunogenicity of the NoV P antigen compared to its dimeric antigen.

Figure 6.

The agglomerate polymers increased immune responses of NoV P antigen. (A) NoV P specific IgG responses after immunization. Mice (n=6–8/group) were immunized with equal molar amounts of GST-NoV P+ polymers and NoV P− dimers intranasally three times without an adjuvant in two-week intervals. NoV P-specific antibody IgG titers of the resulting antisera were determined by EIAs. (B) The resulting mouse antisera blocked NoV-ligand interaction. The mouse antisera were examined for their blocking activity against interaction of NoV P particle with A antigen. The 50% blocking titers (BT50s) of both antisera are indicated by a flashed line. ** (P < 0.01) indicates statistically very significant differences between data pairs of sera at different given dilutions.

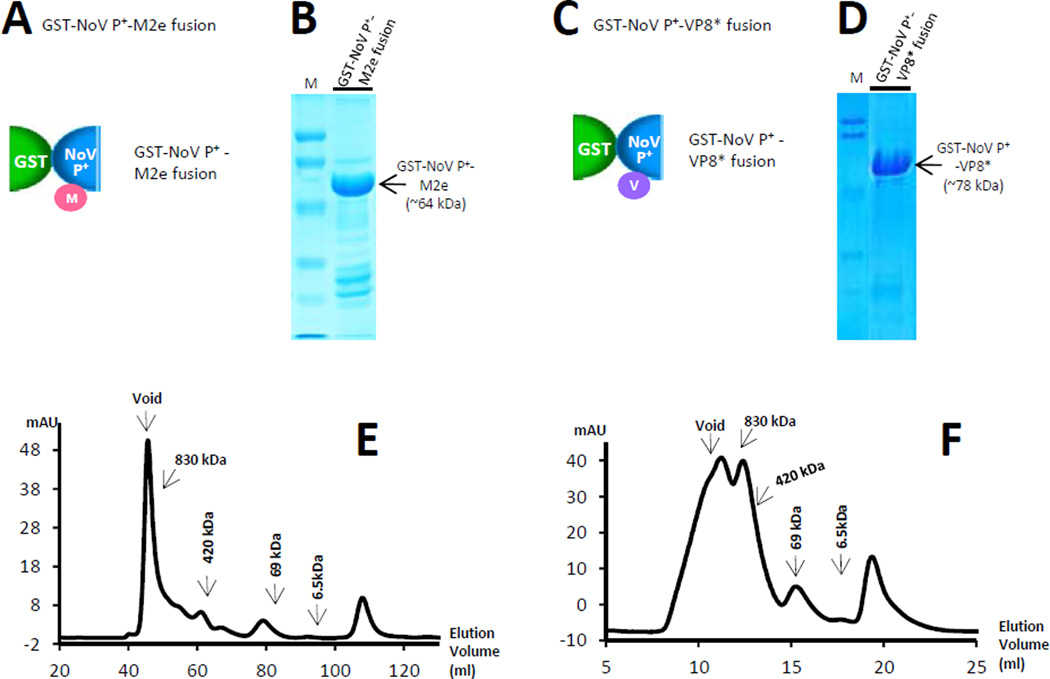

3.6 Display of a monomeric antigen by the polymers

Two monomeric antigens, the M2e epitope (23 residues) [19] of IAV and the VP8* antigen (159 residues) [20] of RV, were inserted into agglomerate polymers, respectively, through surface loop 2 of NoV P domain [20, 22], resulting in the GST-NoV P+-M2e and GST-NoV P+-VP8* polymers (Figure 7). The two proteins are stable and can be purified well at high yields of ~10 mg/liter bacterial culture (Figure 7B and 7D). Gel filtration chromatography confirmed that both fusion proteins formed expected polymers, respectively (Figure 7E and 7F).

Figure 7.

A monomeric antigen can be displayed by the agglomerate polymers. (A and C) schematic illustration of a monomeric antigen (red or purple circle) being attached to the surface of the NoV P+ component of the GST-NoV P+ fusion protein. M indicates the M2e epitope of influenza A virus (A), while V indicates the VP8* antigen of rotavirus (C). (B and D), affinity column-purified GST-NoV P+-M2e (B) and GST-NoV P+-VP8* (D) fusion proteins were analyzed on SDS PAGE gels. (E and F) Elusion curves of gel filtration chromatography of GST-NoV P+-M2e (E) and GST-NoV P+-VP8* (F) fusion proteins indicated the formation of large complexes. The gel filtration column was calibrated by the Gel Filtration Calibration Kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and the purified recombinant P particles, small P particles, and P dimers of NoV (VA387). The elution positions of blue Dextran 2000 (~2000 kDa, void), P particles (~830 kDa), small P particles (420 kDa), P dimers (~69 kDa), and aprotinin (~6.5kDa) were indicated.

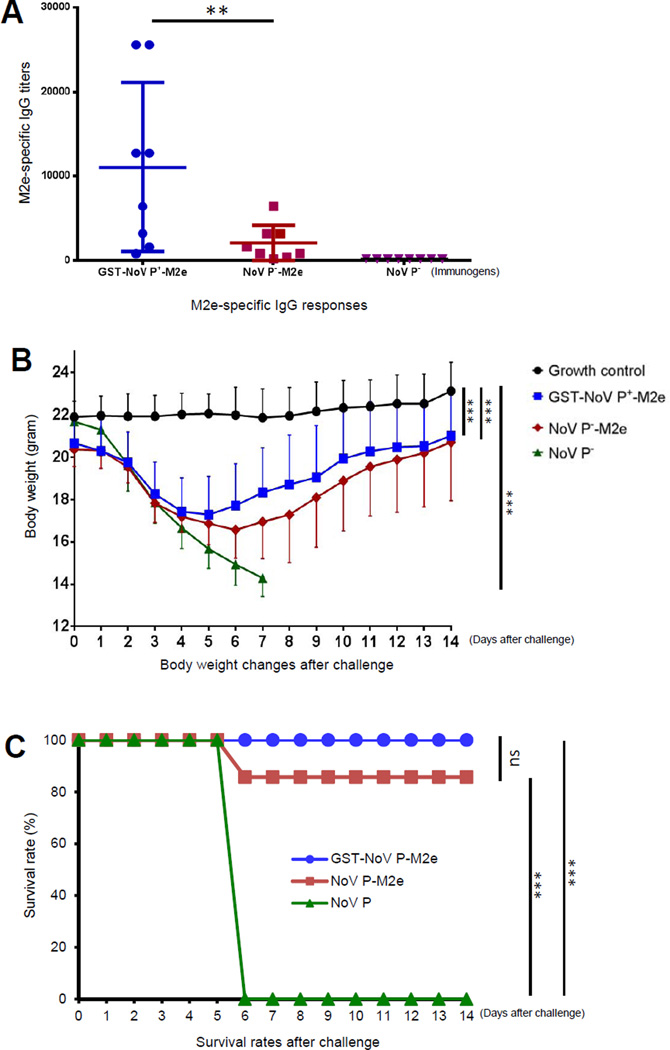

3.7 Immunogenicity and protection of the polymer-displayed M2e epitope

Mice (n=8/group) that were immunized with the agglomerate polymers containing the M2e epitope (GST-NoV P+-M2e) resulted in significantly higher titers of M2e-specific antibody IgGs than those induced by the NoV P−-M2e dimer (P < 0.01) (Figure 8A), while mice that were immunized with NoV P− dimer without M2e epitope did not show detectable M2e antibody (negative controls). These data indicated significantly improved immunogenicity of the polymer-displayed M2e epitope than that of the bivalent M2e.

Figure 8.

The agglomerate polymer-displayed M2e epitope exhibited improved immunogenicity (A) and protective immunity (B and C). (A) M2e-specific antibody (IgG) responses of polymer- and dimer-displayed M2e epitope. Mice (n=8 mice/group) were immunized with equal molar amounts of GST-NoV P+-M2e polymers, NoV P-M2e dimers and NoV P− dimers intranasally three times without an adjuvant in two-week intervals. The M2e-specific IgG titers of the resulting antisera were determined by EIAs. (B and C) Body weight changes (B) and survival rates (C) of vaccinated and various control mice after challenge with influenza A virus (IAV). The mice were challenged with lethal dose of mouse-adapted IAV (strain PR8, H1N1) and monitored for body weight changes (B) and survival rates (C) for 14 days. In (B) “Growth control” mice were not vaccinated and were not challenged. Each data point was a mean value of four to eight mice. The standard deviations are indicated in one direction for clarity of the figure. In (C) “GST-NoV P-M2e”, “NoV-P-M2e” and “NoV P” groups were vaccinated with GST-NoV P+-M2e, NoV-P-M2e and NoV P−, respectively, followed by a challenge with IAV. ** (P < 0.01) indicates a statistically very significant difference, while *** (P < 0.001) indicates a statistically extremely significant difference.

The vaccinated mice were then challenged with a lethal dose of mouse-adapted IAV (strain PR8, H1N1) and monitored for changes of both body weight and mortality for 14 days. While the growth of control mice without virus challenge gained weight steadily, the NoV P−-vaccinated mice lost weight dramatically until they died or were euthanized due to >25% body weight loss. The GST-NoV P+-M2e-vaccinated mice also lost weight temporarily but in less intensity compared with mice that were immunized with the NoV P−-M2e protein (Figure 8B). Most importantly, the GST-NoV P+-M2e polymer vaccine provided vaccinated mice 100% protection against lethal IAV challenge, which was higher than that (85.7%) provided by the NoV P−-M2e vaccine (P>0.05), while all NoV P− vaccinated mice died or were euthanized due to >25% body weight loss by day 6 (P<0.001 compared with GST-NoV P+-M2e, Figure 8C). These data support the notion that the agglomerate polymer improved protective immunity of the displayed M2e epitope.

3.8 Immune response of the polymer-presented VP8* antigen

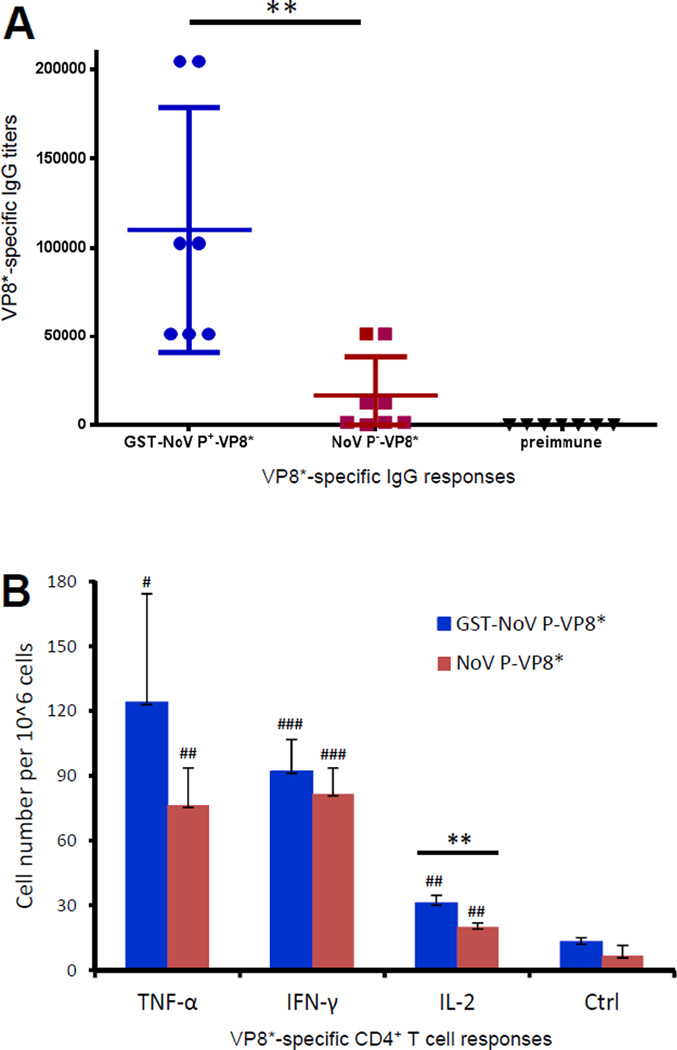

Immunization of mice with the polymer-presented VP8* (GST-NoV P+-VP8*) induced significantly higher VP8*-specific IgG titers than those induced by the dimer-presented VP8* (NoV P−-VP8*) (Figure 9A, P<0.01). In addition, mice (n=3/group) after immunization with the polymer GST-NoV P+-VP8* developed significant higher level of CD4+ T cell cytokine IL-2 specific to the VP8* antigen, compared with that induced by the corresponding free NoV P−-VP8* dimers (P < 0.01 for IL-2, Figure 9B). It was also noted that both polymeric GST-NoV P+-VP8* and dimeric NoV P−-VP8* were able to induce strong VP8* specific CD4+ T cell responses as shown by significantly increased CD4+ T cell cytokines (IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, Figure 9B). These data supported the notion that the polymer-presented VP8* antigen showed improved immune responses.

Figure 9.

The polymer-presented VP8* antigen showed improved humoral (A) and T cell cytokine (B) responses. (A) Antibody (IgG) responses of polymer- and dimer-displayed VP8* antigen. Mice (n=7/group) were immunized with equal molar amounts of GST-NoV P+-VP8* polymers or NoV P-VP8* dimers intranasally three times without an adjuvant in two-week intervals. The VP8*-specific IgG titers were determined by EIAs. (B) CD4+ T cell cytokine responses of polymer- and dimer-displayed VP8* antigen. Mice (n=3/group) were immunized as in (A). After stimulation of the splenocytes with a VP8*-specific CD4+ T cell epitope, the resulting CD4+ T cell cytokines IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α were measured by intracellular cytokine staining. Cytokine-producing T cells from the polymer- (GST-NoV P-VP8*) and dimer- (NoV P-VP8*) immunized mice were shown in blue and red, respectively. Those from unimmunized mice were negative controls (Ctrl). Data were presented as cytokine-producing T cell numbers per 106 cells. The statistical significances between the immunized groups and unimmunized controls (Ctrl) are shown by # symbols (# P<0.05, ## P<0.01, ### P<0.001), while those between the polymer- and dimer-immunized groups (blue and red) are shown by ** (P<0.01).

3.9 Binding function of the NoV P domain in polymers

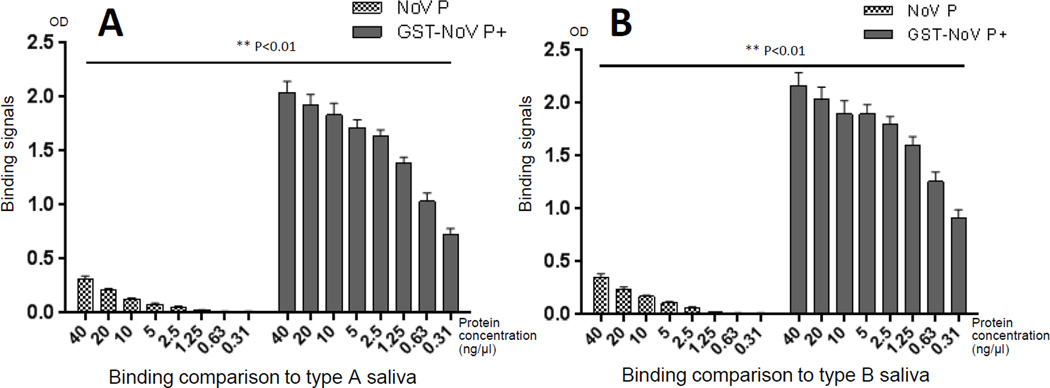

The P domain is the HBGA (histo-blood group antigen) ligand binding domain of NoVs and weak interactions of NoV P dimers with HBGAs in human saliva can be measured by ELISA-based binding assays [23, 24] (Figure 10). It was noted that the agglomerate polymers of GST-NoV P+ had significantly higher binding activities to type A and B saliva samples than those of the NoV P dimers (Figure 10) (P<0.01). Thus, polymer formation is an efficient method to increase the ligand binding function of NoV P proteins.

Figure 10.

The agglomerate polymers increased binding activities of NoV P domain to HBGA ligands. The free NoV P− dimers bound weakly, while the agglomerate polymers of GST-NoV P+ bound strongly to type A (A) and B (B) saliva samples that were defined as type A and B nonsecretor. Y-axes indicate the binding signal intensities in optical density (OD), while X-axes indicate protein concentrations that were used for the binding assays.

4. Discussion

In a previous study we proposed and verified a simple strategy to turn small dimeric proteins into linear or network polymers for improved immunogenicity [14]. The polymers assembled through intermolecular dimerization of two to three dimeric proteins that were fused together by recombinant DNA technique. In this study, we further developed a technology to produce more sophisticated polymers by introducing an oligomeric protein into the basic units of fusion proteins (Figure 1). As a proof of concept, we designed and successfully constructed the branched-linear polymers by fusion of a dimeric protein (GST) with the HEV P+ protein that forms dimers and tetramers (Figure 2), as well as the agglomerate polymers by replacing the HEV P+ component with the 24-meric NoV P+ protein (Figure 3). Based on the proposed principle (Figure 1) and the two successful examples, it appears logical to extrapolate that new polymers can be produced by introducing other oligomeric proteins forming oligomers with various valences to replace one or both components of the fusion protein units. In fact, the two components of the fusion protein can be in any combinations of dimeric/oligomeric proteins, which would further complicate the polymer outcomes in terms of shapes, structures, morphologies and complexities. Thus, the technology developed in this study will extensively broaden the application potentials of our protein polymer system.

The branched-linear and the agglomerate polymers represent a simple and an extremely sophisticated polyvalent complex that can be made through this technology. The simple linear polymers is formed through fusion of two dimeric proteins together [14]. In this study we demonstrated the branching formation in the linear polymers by introducing the dimeric/tetrameric HEV P+ proteins. Because only a small portion (<10%) of the HEV P+ protein formed tetramers (Figure 2E), the branched-linear polymers are basically the linear polymers with a low frequency of branchings that were likely formed by the tetrameric interaction of the HEV P+ proteins. However, we noted that the actually branching frequency, based on the counts of protein components, appeared higher than 10% (Figure 2G). This discrepancy suggests that the HEV P+ protein may behave differently as a part of a fusion protein compared with its free forms.

On the other hand, the agglomerate polymers (Figure 3) appear extremely complex. Since all GSTs tend to form dimers, while all NoV P+ proteins tend to form 24-meric complexes [17, 18] in the polymers, these complicated interactions end up with the formation of the observed agglomerate polymers. However, certain structural or spatial constraints may occur within the agglomerate polymers to prevent a perfect NoV P+ 24-mer complex formation. Thus, while the formation of agglomerate polymers by the GST-NoV P+ is anticipated, its accurate formation principle remains elusive. In addition, it seems conceivable to speculate that the complexities of most other polymers that can be constructed through this technology in the future will be something between the branched-linear and the agglomerate polymers.

The detail timing when the polymers initially assembled during the expression and purification procedures remains to be defined. The fusion proteins were clearly expressed originally as monomers in E. coli. They then assembled spontaneously into polymers through intermolecular dimerization and oligomerization as soon as they were freely available. This may happen initially in the bacteria, but may also first occur in solution after the fusion proteins were extracted from E. coli during the procedure of protein purification. By the time when the purified fusion proteins were analyzed by gel-filtration chromatography, polymers definitely formed as shown by their large molecule sizes that were measured by the elusion curves of gel-filtration analyses.

While different polymers may find various applications in biomedicine, which warrants future studies, this study focused on their potentials as vaccines. The polyvalent nature of these antigen complexes allows excellent presentations of the repetitive antigenic determinants, including both B cell and T cell epitopes, to the host immune system for stimulation of humoral and cellular immune responses to a great magnitude. Indeed, all four examined polymers in this study induced significantly higher virus specific antibody titers and/or CD4+ T cell responses compared with those induced by the dimeric antigens. Further evidence in supporting the applications of polymers as vaccines included the higher neutralization activity and protective immunity of the polymers against virus infection and replication than those of the dimer vaccines. Therefore, while the underlying mechanisms of the observed immunogenicity improvement remain to be defined, the readily available polymers comprising antigens or epitopes of the four viral pathogens (see below) and most likely those containing antigens of other pathogens that will be made by our technology in the future are promising vaccine candidates that warrant further evaluation.

Viral capsid proteins share a common feature of homotypic interaction that is a major force of capsid formation. Additionally, many truncated viral structural proteins, including the viral surface protruding domains, are known to form homodimers, and/or oligomers with various valences [16, 18, 24, 27, 35, 36]. For example, NoV protruding (P) domain forms dimers [37–40], 12-mer [27], and 24-mer particles [17, 18] with defined structures, while 18-mer and 32-mer complexes of NoV P domain have also been observed [41]. This offers a wide range of viral antigens as components for construction of different polymers for vaccine development. In addition, a monomeric peptide epitope or a protein antigen can be inserted into the polymers for increased immunogenicity (see below), which further extends the application range of the polymers for vaccine development. In this and previous studies, we have examined several polymer vaccines comprising neutralizing antigens of NoV, HEV, RV, and IAV ([13, 14] and this report). All the immunization outcomes of these vaccine candidates clearly supported the conclusion that the antigens and epitopes in the polymer induced high immune responses, neutralization and protective immunity.

Another major feature of the polyvalent complex system is its capability to be a platform for display of various epitopes and antigens for increased immunogenicity for purpose of vaccine development. Many known crystal structures of viral capsids and/or truncated structural proteins provide solid bases for selection of insertion sites for foreign epitopes/antigens, in which a surface exposed loop and the ends are usually good choices. As examples of the feasibility, a small peptide epitope, the 23-residue M2e epitope of IAV, and a large protein antigen, the 159-residue VP8* antigen of RV, were successfully inserted to surface loop 2 [20] of NoV P domain without disruption of the polymer formation (Figure 7). Both of the resulting chimeric polymers were demonstrated as promising vaccines against the IAV (Figure 8) and RV (Figure 9), respectively. These data support the notion that our polymer system is an excellent platform that can be applied for many other antigens with a need for enhanced immunogenicity.

The fact that the basic fusion protein units of the polymers are composed of two to three antigen components offers a great opportunity for design and construction of di- and/or trivalent vaccines. Particularly, the capability of a polymer to display an extra antigen makes such application flexible. The antigen components may be from two to three different pathogens and thus the resulting polymers can function as multivalent vaccines against up to three pathogens and their associated illnesses. The feasibility of such polymer-based dual vaccines has been shown in two previous [13, 14] and this study, while the trivalent vaccines are under preclinical evaluation currently in our lab (unpublished data).

The polyvalent feature also enables the polymers as a platform to increase the functionality of a functional component. As an example, the HBGA binding function of the NoV P domain was examined (Figure 10). As expected, the agglomerate polymers of GST-NoV P+ drastically increased the HBGA binding activity to all type A, B and O (data not shown) saliva samples in an ELISA-based binding assay than those of NoV P dimers. Similar increased effects were also observed in the linear and network polymers previously [13, 14], most likely through the avidity effects of multiple interactions of the NoV P domain to HBGAs. Thus, formation of polyvalent complexes may be an effective approach to enhance the functionality of a functional protein.

As demonstrated in the current study, various fusion proteins can be easily produced and purified through the E. coli expression system with high efficiencies of polymer formation. All analysis approaches through light scattering, EM and gel filtration chromatography showed the formation and heterogeneous sizes of the polymers with median sizes of 6–7 micrometers, suggesting that most polymer contains thousands of copies of each component based on the known dimensions of GST [15], HEV P [16] and NoV P [38]. It was noted that there is a large subpopulation of agglomerate polymer with sizes at about 2.2 micrometers (Figure 4B). Although the mechanism for the presence of this subpopulation remains unknown, EM images did show large proportions of agglomerate polymers with sizes around 2.2 micrometers (Fig 3E). Future analysis using other approaches, such as analytical ultracentrifugation, will be performed for better understanding the formation of these polymers. The heterologous sizes of the polymers may be a challenge for producing homogenous polymers for better applications. However, we noted the size distribution patterns of the polymers were highly reproducible among different productions of the same fusion proteins. This means that each production of the polymers result in similar products with the same or very similar size distribution pattern. In other words, the polymers are, in fact, produced in a controlled fashion.

5. Conclusion

We have proposed an innovative technology and proven its feasibility to turn small, low immunogenic antigens into large polymers with significantly enhanced immunogenicity and functionality. Two polymers, the branched-linear and agglomerate, representing a simple and a very complex polymer, have been made as proofs of the feasibility of our technology. The polymers were easily constructed in the bacterial system and were able to induce significantly higher humoral and cellular immune responses than those induced by the monomeric or dimeric antigens. The higher neutralization and protective immunity of the polymer vaccines than those of the monomeric/dimeric vaccines further strengthen the conclusion. The established models and procedures in this study will serve as guidelines for future design, construction, manipulation, and applications of the polymers that may find applications in many fields in biomedicine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research described in this article was supported by the National Institute of Health, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R21 AI092434 to M.T. and R01AI089634 and P01 HD13021 to X.J.) and by an Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award (NIH/NCRR 8UL1TR000077-04) to M.T. Support was also from the Innovation Fund of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center to M.T.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tan M, Jiang X. Subviral particle as vaccine and vaccine platform. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;6C:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAleer WJ, Buynak EB, Maigetter RZ, Wampler DE, Miller WJ, Hilleman MR. Human hepatitis B vaccine from recombinant yeast. Nature. 1984;307:178–180. doi: 10.1038/307178a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andre FE, Safary A. Summary of clinical findings on Engerix-B, a genetically engineered yeast derived hepatitis B vaccine. Postgrad Med J. 1987;63(Suppl 2):169–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirnbauer R, Booy F, Cheng N, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Papillomavirus L1 major capsid protein self-assembles into virus-like particles that are highly immunogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:12180–12184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagu S, Kwak K, Garcea RL, Roden RB. Vaccination with multimeric L2 fusion protein and L1 VLP or capsomeres to broaden protection against HPV infection. Vaccine. 2010;28:4478–4486. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C, Ferris DG, Jenkins D, Schuind A, et al. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1757–1765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, Andrade RP, Ault KA, Giuliano AR, et al. Prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in young women: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre phase II efficacy trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:271–278. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Proffitt A. First HEV vaccine approved. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:300. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu FC, Zhang J, Zhang XF, Zhou C, Wang ZZ, Huang SJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of a recombinant hepatitis E vaccine in healthy adults: a large-scale, randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:895–902. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu PC, Lin WL, Wu CM, Chi JN, Chien MS, Huang C. Characterization of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) capsid particle assembly and its application to virus-like particle vaccine development. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;95:1501–1507. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kekarainen T, Montoya M, Dominguez J, Mateu E, Segales J. Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) viral components immunomodulate recall antigen responses. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2008;124:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plummer EM, Manchester M. Viral nanoparticles and virus-like particles: platforms for contemporary vaccine design. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2011;3:174–196. doi: 10.1002/wnan.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Cao D, Wei C, Meng XJ, Jiang X, Tan M. A dual vaccine candidate against norovirus and hepatitis E virus. Vaccine. 2014;32:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Huang P, Fang H, Xia M, Zhong W, McNeal MM, et al. Polyvalent complexes for vaccine development. Biomaterials. 2013;34:4480–4492. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fritz-Wolf K, Becker A, Rahlfs S, Harwaldt P, Schirmer RH, Kabsch W, et al. X-ray structure of glutathione S-transferase from the malarial parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13821–13826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2333763100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li S, Tang X, Seetharaman J, Yang C, Gu Y, Zhang J, et al. Dimerization of hepatitis E virus capsid protein E2s domain is essential for virus-host interaction. PLoS pathog. 2009;5:e1000537. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan M, Fang P, Chachiyo T, Xia M, Huang P, Fang Z, et al. Noroviral P particle: Structure, function and applications in virus-host interaction. Virology. 2008;382:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan M, Jiang X. The p domain of norovirus capsid protein forms a subviral particle that binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J Virol. 2005;79:14017–14030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14017-14030.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia M, Tan M, Wei C, Zhong W, Wang L, McNeal M, et al. A candidate dual vaccine against influenza and noroviruses. Vaccine. 2011;29:7670–7677. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan M, Huang P, Xia M, Fang PA, Zhong W, McNeal M, et al. Norovirus P particle, a novel platform for vaccine development and antibody production. J Virol. 2011;85:753–764. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01835-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmad I, Holla RP, Jameel S. Molecular virology of hepatitis E virus. Virus Res. 2011;161:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan M, Xia M, Huang P, Wang L, Zhong W, McNeal M, et al. Norovirus P Particle as a Platform for Antigen Presentation. Procedia Vaccinol. 2011;4:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan M, Meller J, Jiang X. C-terminal arginine cluster is essential for receptor binding of norovirus capsid protein. J Virol. 2006;80:7322–7331. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00233-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan M, Hegde RS, Jiang X. The P domain of norovirus capsid protein forms dimer and binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J Virol. 2004;78:6233–6242. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6233-6242.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan M, Jiang X. The p domain of norovirus capsid protein forms a subviral particle that binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J Virol. 2005;79:14017–14030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14017-14030.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan M, Zhong W, Song D, Thornton S, Jiang XE. coli-expressed recombinant norovirus capsid proteins maintain authentic antigenicity and receptor binding capability. J med Virol. 2004;74:641–649. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan M, Fang PA, Xia M, Chachiyo T, Jiang W, Jiang X. Terminal modifications of norovirus P domain resulted in a new type of subviral particles, the small P particles. Virology. 2011;410:345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang P, Farkas T, Marionneau S, Zhong W, Ruvoen-Clouet N, Morrow AL, et al. Noroviruses Bind to Human ABO, Lewis, and Secretor Histo-Blood Group Antigens: Identification of 4 Distinct Strain-Specific Patterns. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:19–31. doi: 10.1086/375742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang P, Farkas T, Zhong W, Tan M, Thornton S, Morrow AL, et al. Norovirus and histo-blood group antigens: demonstration of a wide spectrum of strain specificities and classification of two major binding groups among multiple binding patterns. J Virol. 2005;79:6714–6722. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6714-6722.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atmar RL, Bernstein DI, Harro CD, Al-Ibrahim MS, Chen WH, Ferreira J, et al. Norovirus vaccine against experimental human Norwalk Virus illness. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2178–2187. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frenck R, Bernstein DI, Xia M, Huang P, Zhong W, Parker S, et al. Predicting Susceptibility to Norovirus GII.4 by Use of a Challenge Model Involving Humans. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1386–1393. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reeck A, Kavanagh O, Estes MK, Opekun AR, Gilger MA, Graham DY, et al. Serological correlate of protection against norovirus-induced gastroenteritis. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1212–1218. doi: 10.1086/656364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emerson SU, Clemente-Casares P, Moiduddin N, Arankalle VA, Torian U, Purcell RH. Putative neutralization epitopes and broad cross-genotype neutralization of Hepatitis E virus confirmed by a quantitative cell-culture assay. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:697–704. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanford BJ, Emerson SU, Purcell RH, Engle RE, Dryman BA, Cecere TE, et al. Serological Evidence for a Hepatitis E Virus-Related Agent in Goats in the United States. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2013;60:538–545. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen XS, Casini G, Harrison SC, Garcea RL. Papillomavirus capsid protein expression in Escherichia coli: purification and assembly of HPV11 and HPV16 L1. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:173–182. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong J, Dong L, Mendez E, Tao Y. Crystal structure of the human astrovirus capsid spike. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12681–12686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104834108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bu W, Mamedova A, Tan M, Xia M, Jiang X, Hegde RS. Structural basis for the receptor binding specificity of Norwalk virus. J Virol. 2008;82:5340–5347. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00135-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao S, Lou Z, Tan M, Chen Y, Liu Y, Zhang Z, et al. Structural basis for the recognition of blood group trisaccharides by norovirus. J Virol. 2007;81:5949–5957. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00219-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Y, Tan M, Xia M, Hao N, Zhang XC, Huang P, et al. Crystallography of a lewis-binding norovirus, elucidation of strain-specificity to the polymorphic human histo-blood group antigens. PLoS pathog. 2011;7:e1002152. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi JM, Hutson AM, Estes MK, Prasad BV. Atomic resolution structural characterization of recognition of histo-blood group antigens by Norwalk virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9175–9180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803275105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bereszczak JZ, Barbu IM, Tan M, Xia M, Jiang X, van Duijn E, et al. Structure, stability and dynamics of norovirus P domain derived protein complexes studied by native mass spectrometry. J Struct Biol. 2012;177:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]