Abstract

Background:

Athletic trainers (ATs) play an important role in the evaluation, management, and referral of student-athletes after sport-related concussion. Understanding factors that influence ATs’ patient care decisions is important to ensure best practices are followed.

Purpose:

To identify ATs’ current concussion management practices and referral patterns for adolescent student-athletes after sport-related concussion as well as the factors associated with those practices.

Study Design:

Cross-sectional study.

Level of Evidence:

Level 3.

Methods:

A total of 851 participants from a convenience sample of 3286 ATs employed in the secondary school setting (25.9% response rate) completed the Athletic Trainers’ Beliefs, Attitudes, and Knowledge of Pediatric Athletes with Concussions (BAKPAC-AT) survey. The BAKPAC-AT consists of several questions to assess ATs’ concussion management, referral practices, and established relationships with other health care professionals.

Results:

The majority of ATs had a written concussion policy (82.4%, n = 701) and standing orders approved by their directing physician (67.3%, n = 573); 75.1% (n = 639) of ATs conduct baseline testing, with the majority using computerized neurocognitive tests (71.2%, n = 606). Follow-up concussion testing was employed by 81.8% (n = 696). Years of certification (P = 0.049) and type of secondary school (P = 0.033) predicted ATs’ use of baseline testing. Nearly half of the respondents (48.8%, n = 415) refer 100% of concussion cases to a physician. The most influential factors that lead to a referral were state law (40.3%, n = 343), personal preference (34.7%, n = 295), and school district policy (24.8%, n = 211).

Conclusion:

Of the ATs surveyed, most were engaged in baseline and follow-up testing, primarily with neurocognitive tests. Most ATs refer patients to physicians after concussion. While state regulation and personal preference were primary factors influencing referral decisions, it is unclear at what point of care the referral occurs.

Keywords: sport-related concussion, adolescent athletes, referral patterns, management practices

During the 2011 and 2012 academic years, roughly 7.6 million students participated in high school sports.1 There has been a steady increase in sport participation,4 which creates the potential for a similar increase in the rate of sports injuries. Although a variety of injuries can occur in different clinical settings, approximately 9% to 13% of injuries sustained in high school sports are sport-related concussions.6,14 Marar et al14 reported that for every 10,000 athlete-exposures, roughly 2.5 concussions occurred.

Current recommendations for concussion management suggest a multifaceted approach for evaluating the numerous domains of concussions that could be impaired.3,7,10,12,18 Current literature recommends concussion management practices should consist of (1) a preparticipation history and physical examination,7,18 (2) a baseline concussion assessment,7 (3) follow-up concussion assessment testing throughout the recovery process to monitor progression,7 and (4) a return-to-play clearance assessment.7,18

Recent literature suggests that both cognitive and physical rest are the cornerstones of concussion management.7,9,17,18 Cognitive rest involves avoiding activities that require attention and concentration,17,18,20,23 and may include avoiding computers, text messaging, video games, or reading.9,15,20 Physical rest includes avoiding any activity that may exacerbate concussion symptoms.9 After acute symptoms resolve, a graded return to activity should commence,7,17,18 allowing for a safe return to activity and ensuring symptoms do not reemerge once physical activity is introduced.18 Additionally, it is important that student-athletes do not return to sport participation the same day a suspected concussion is sustained. This is to prevent further damage that may lead to a more catastrophic event.7,18 Along with return-to-play progression, it is imperative for the student-athlete to follow a “return to learn” protocol, including accommodations in academics after a sport-related concussion.11

Having well-trained health care professionals involved in the management of concussions is essential. Particularly in the secondary school setting, the athletic trainer (AT) is typically the primary provider for student-athletes following sport-related concussions.19 Therefore, it is vital that ATs have the proper knowledge and understanding of concussion management and referral practices for successful care of their patients. Establishing a concussion management team and ensuring good communication and interaction between all school personnel can assist with the treatment process throughout the school day.

Current recommendations suggest a written policy as well as a multifaceted approach to assessment and management constitutes best practices.7,17,18 With limited studies on concussion management in the secondary school setting,13 it is still unclear how ATs employed in the secondary school setting are managing the care of student-athletes after a sport-related concussion. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to identify ATs’ current concussion management practices, including referral patterns, as well as the factors associated with these practices for adolescent student-athletes after sport-related concussion.

Methods

Instrumentation

Survey Development

The Beliefs, Attitudes, and Knowledge following Pediatric Athlete Concussions in the Secondary School–Athletic Trainer (BAKPAC-AT) survey16 was created via Qualtrics Survey Software (Qualtrics Lab, Inc), and consists of 3 sections (concussion management and care, concussion referral, and academic accommodations) (see Appendix 1, available at http://sph.sagepub.com/content/suppl). In addition to the 3 survey sections, which included a variety of structured questions (eg, binary, multiple choice, open-ended, Likert-type scale, and multistep answers), a brief demographic questionnaire regarding participants’ personal and professional information was also included. After survey development, a panel of 3 concussion experts assessed the survey for content validity and comprehensiveness. The final survey was deemed a valid and comprehensive instrument to assess ATs’ concussion management practices, concussion referral patterns, and their perceptions of academic accommodations as they relate to sport-related concussion in the secondary school setting.16 Because of the nature of the data collected for this study, a reliability analysis to determine internal consistency of the instrument was not warranted. However, a small representative sample (n = 18) completed the BAKPAC-AT for further content refinement and comprehensibility.

Procedures

The research team requested names and e-mail addresses of ATs employed in the secondary school setting from the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) via the Survey List Request Form. An e-mail, including the purpose of the investigation, the estimated time to complete the survey, a URL hyperlink to the survey Web page, and contact information of the primary researcher, was sent to potential participants requesting their participation in the study. Participants were asked to complete the survey during a 4-week period between September and October 2012. A reminder e-mail was sent once a week for the 3 weeks after the initial request.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics (version 21.0.0; IBM Corp). Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and frequencies, were reported. The independent variables included years of experience as a certified AT, years of experience at the secondary school setting, type of secondary school, inclusion of football at the secondary school, and secondary school student enrollment. The dependent variables were participants’ responses related to concussion management and referral survey questions. Separate forward stepwise binary logistic regression analyses (P < 0.05) were used to determine whether any personal (years certified, experience in secondary school setting) or school (enrollment, type, presence of football) demographics predicted the use of baseline or follow-up concussion assessment testing, ATs’ decisions to refer patients to physicians after sport-related concussion, and whether the AT clears athletes to return to play.

Results

Respondents

A total of 851 ATs, representing all 50 states and the District of Columbia, accessed the online survey, for a 25.9% response rate. Respondents consisted of 376 females and 308 males; 167 participants who accessed the survey instrument did not complete the demographic questionnaire (Table 1). Of the 851 ATs who accessed the survey, 51 individuals did not complete any questions, while 19 individuals were automatically excluded for not providing athletic training services in the secondary school setting during the time of the investigation. Therefore, 792 ATs employed in the secondary school setting completed at least one part of the instrument, and their responses were included for data analysis.

Table 1.

Participant and school demographics (n = 851)

| Secondary School Athletic Trainers |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 308 | 36.2 |

| Female | 376 | 44.2 |

| Years AT experience | ||

| 0-2 | 46 | 5.4 |

| 3-5 | 124 | 14.6 |

| 6-10 | 137 | 16.1 |

| 11-15 | 118 | 13.9 |

| 16-20 | 110 | 12.9 |

| 21+ | 149 | 17.5 |

| Years AT SS Experience | ||

| 0-2 | 75 | 8.8 |

| 3-5 | 140 | 16.5 |

| 6-10 | 146 | 17.2 |

| 11-15 | 132 | 15.5 |

| 16-20 | 88 | 10.3 |

| 21+ | 103 | 12.1 |

| Highest education level | ||

| Bachelor’s | 260 | 30.6 |

| Master’s | 417 | 49.0 |

| PhD, EdD | 5 | 0.6 |

| DPT | 2 | 0.2 |

| Type of school | ||

| Public school | 539 | 63.3 |

| Public charter | 2 | 0.2 |

| Private parochial | 63 | 7.4 |

| Private charter | 15 | 1.8 |

| Private other | 56 | 6.6 |

| Other | 9 | 1.1 |

| Enrollment (number of students) | ||

| <250 | 19 | 2.2 |

| 250-499 | 96 | 11.3 |

| 500-999 | 164 | 19.2 |

| 1000-1999 | 254 | 29.8 |

| 2000-2999 | 111 | 13.0 |

| 3000-3999 | 31 | 3.6 |

| 4000-4999 | 4 | 0.5 |

| >5000 | 5 | 0.6 |

| Football | ||

| Yes | 644 | 75.7 |

| No | 40 | 4.7 |

AT, athletic trainer; SS, secondary school.

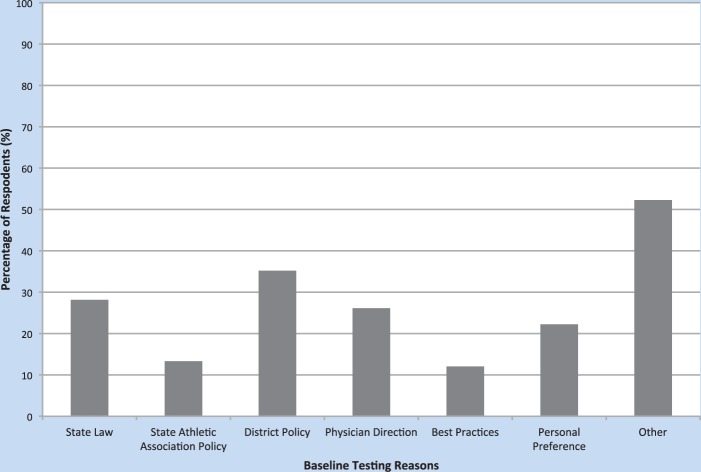

Baseline Concussion Testing

The majority of ATs indicated that they had a written concussion policy in place at their secondary school (82.4%, n = 701). In addition, 67.3% (n = 573) had standing orders about concussions approved by a directing physician. Baseline testing was used by 75.1% (n = 639) of ATs (Figure 1). The majority of ATs that conduct baseline concussion assessment testing used computer neurocognitive tests (71.2%, n = 606), with fewer using balance assessments (9.2%, n = 78) and symptom scales (11.4%, n = 97) as part of the baseline assessment battery. The primary factors preventing ATs from employing concussion baseline assessment testing were a lack of money (11.9%, n = 101) and time (10.6%, n = 90).

Figure 1.

Factors that lead athletic trainers to employ baseline concussion assessment testing.

Results from the regression analyses (see Appendix 2, available at http://sph.sagepub.com/content/suppl) revealed that years of certification (P = 0.026) and type of secondary school (P = 0.008) predicted the use of baseline testing, with ATs practicing 6 to 10 years (odds ratio [OR] = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.21-0.73; P = 0.003;) and 10 to 16 years (OR = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.22-0.82; P = 0.011) less likely to baseline test compared with those practicing less than 5 years, and private parochial (OR = 2.29, 95% CI = 1.0-5.24; P = 0.05) and private other (OR = 14.50, 95% CI = 1.98-106.21; P = 0.008) affiliation were more likely to test than public schools.

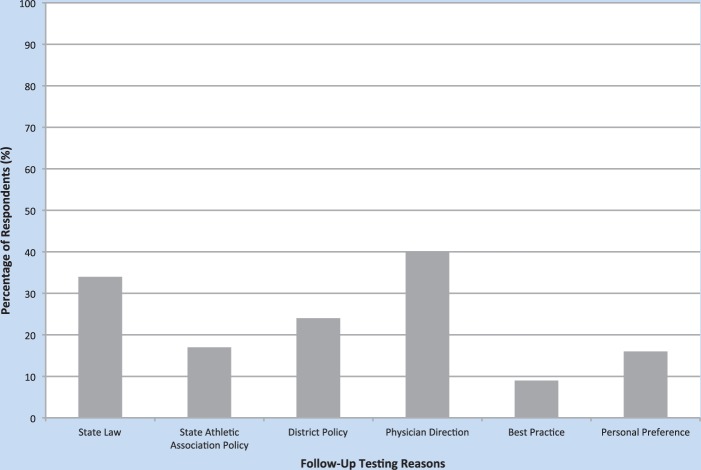

Follow-up Concussion Testing

More than 90% of respondents (n = 695) employed follow-up concussion assessments in their clinical practice (Figure 2). The majority of assessment tools utilized included computerized neurocognitive testing (68.5%, n = 583), balance testing (23.5%, n = 200), symptom scales (35.5%, n = 302), and sideline assessments, such as the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 2 (SCAT2) (40.5%, n = 345). Money (4.3%, n = 37), time (3.4%, n = 29), and limited resources (2.8%, n = 24) were the primary factors that prevented ATs from administering concussion assessment testing. There were no significant predictors of follow-up testing.

Figure 2.

Factors that lead athletic trainers to employ follow-up concussion assessment testing.

Return-to-Play Clearance

The majority (70.9%, n = 603) of ATs clear athletes after return-to-play protocols. However, the primary reasons preventing those ATs who do not clear athletes after a return-to-play protocol were state law restrictions (62%, n = 93), school district policy (23%, n = 32), and state athletic policy (18%, n = 27). Furthermore, 55.9% (n = 476) of respondents reported that state law, state regulations, or standing orders require them to refer to a physician for final clearance of a student-athlete who has sustained a concussion.

Collaborative Care and Referral

Roughly half (47.4%, n = 403) of ATs interact with a school nurse daily. Of those who interact with a school nurse, 37.1% (n = 316) collaborate with school nurses on concussion management. While 19.7% of ATs (n = 168) reported they share care of concussion management with school nurses, 12.5% of respondents (n = 106) indicated they serve as the sole health care provider for concussion management.

A majority of respondents (77.8%, n = 662) refer adolescent athletes to a physician after sport-related concussion. Nearly half of these respondents (48.8%, n = 415) indicated they refer 100% of annual concussion cases. The most frequently identified factors leading to a referral were state law (40.3%, n = 343), personal preference (34.7%, n = 295), and school district policy (24.8%, n = 211). ATs most commonly reported having an established relationship with sports medicine fellowship–trained physicians (80%, n = 596), neurologists (33%, n = 243), neuropsychologists (27%, n = 201), and physician assistants (27%, n = 197).

Seven percent of respondents (n = 52) did not have established relationships with other health care providers. Further analysis of this subgroup indicated that 31 respondents do not have standing orders and do not have established relationships. In addition, 21 respondents did have standing orders but do not have established relationships with other health care providers. Nineteen percent of respondents (n = 10) do not refer patients to a physician after sport-related concussion. Furthermore, 26.9% reported they do not have a directing physician for the secondary school at which they are employed. Personal and school demographics of this subgroup are referred from Williams et al.16

Discussion

The majority of ATs are practicing proper concussion management by utilizing objective tools during follow-up concussion assessment testing, which is similar to results found by Lynall et al.13

According to our survey data, the majority of ATs are discharging student-athletes following established return-to-play protocols. This means that the AT is making the final return-to-participation decision for the student-athlete. To discharge a student-athlete for return-to-sport participation (1) an AT must have direction from his or her directing physician, (2) the decision must be within the state’s scope of practice for athletic training, and (3) existing state concussion laws must permit it. Best practices suggest a student-athlete can be discharged for sport participation once they have followed a return-to-play progression and have been reevaluated by a health care professional.3,10

Collaborative Care and Referral

Health care providers are frequently asked to work together in interprofessional teams for better patient care. Interprofessional collaboration is especially important for concussions because of the multifaceted nature of concussion management.8,22 The AT should collaborate with and/or seek assistance from physicians with a sports medicine fellowship, neurologists, physician assistants, or other health care providers regarding concussion management.

At the high school level, about half of the ATs surveyed indicated they work with a school nurse on a daily basis, and the majority of those collaborate with the school nurse on concussion management. School nurses can play a vital role in the concussion management process, especially with regard to cognitive rest and return-to-learn strategies.5,21 School nurses can often serve as the liaison between school officials (eg, administrators, teachers) and the health care professionals managing concussion during the school day. They can also assist in monitoring the student-athlete throughout the school day and play a role in obtaining academic accommodations, if necessary.5

Currently, 7 states allow only a licensed physician (MD or DO) to clear the student-athlete for return to play.

More than one third of ATs indicated they never refer to physician assistants, who often serve as extenders of physicians and whose specialties have relevance to concussion management practices.

Seven percent of respondents did not have an established relationship with another provider. This suggests that those ATs are solely managing all aspects of care for their concussed student-athletes. While there may be reasons for this situation (specialty provider availability in rural areas), this situation is of concern because it suggests the AT is not meeting a basic requirement to provide athletic training services under the direction of a physician. Relatedly, 59.6% of respondents did not have physician-approved standing orders for their concussion management practices. Standing orders of this kind are a basic component of compliance with physician direction requirements for athletic training practice. A directing physician is not only important for the safety of the student-athletes but is also a requirement of nationally certified ATs2 and is a component of most state licensure laws.

Limitations and Future Research

This study is not without limitations. The respondents may not have indicated the usage of a symptom checklist as a separate response with regard to concussion assessment. However, the respondents may utilize ImPACT or other computerized neurocognitive systems as their neurocognitive testing, and a symptom checklist is included in those tools.

Conclusion

Athletic trainers must establish relationships with various health care professionals, and should increase the use of balance and symptom assessments as part of the concussion management plan. Clinicians may be missing important information to aid their clinical decisions. ATs must stay up-to-date with best-practice recommendations and recognize appropriate referral patterns to effectively provide care for student-athletes following sport-related concussions.

Footnotes

The following author declared potential conflicts of interest: Tamara C. Valovich McLeod, PhD, ATC, FNATA, is a paid consultant for Grand Junction Community Hospital.

References

- 1. Benson BW, Hamilton GM, Meeuwisse WH, McCrory P, Dvorak J. Is protective equipment useful in preventing concussion? A systematic review of the literature. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(suupl 1):i56-i67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Board of Certification for the Athletic Trainer. BOC Standard of Professional Practice. 2006. http://www.bocatc.org/images/stories/resources/boc_standards_of_professional_practice_1401bf.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2014

- 3. Broglio SP, Cantu R, Gioia GA, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: management of sport concussion. J Athl Train. 2014;49:245-265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For concussion prevention in youth. http://www.cdc.gov/concussion/sports/nfl_poster.html. Accessed April 12, 2012

- 5. Diaz AL, Wyckoff LJ. NASN position statement: concussions—the role of the school nurse. NASN Sch Nurse. 2013;28:110-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gessel L, Fields S, Collins C, Dick R, Comstock RC. Concussions among United States high school and collegiate athletes. J Athl Train. 2007;42:495-503 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;11:2250-2257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greiner AC, Knebel E. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guerriero R, Proctor M, Mannix R, Meehan WP, 3rd. Epidemiology, trends, assessment and management of sport-related concussion in United States high schools. Clin Opin Pediatr. 2012;24:696-700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guskiewicz KM, Register-Mihalik J, McCrory P, et al. Evidence-based approach to revising the SCAT2: introducing the SCAT3. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:289-293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Halstead ME, McAvoy K, Devore CD, et al. Returning to learning following a concussion. Pediatrics. 2013;132:948-957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harmon KG, Drezner JA, Gammons M, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:15-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lynall R, Laudner KG, Mihalik JP, Stanek JM. Concussion-assessment and -management techniques used by athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2013;48:844-850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marar M, McIlvain NM, Fields SK, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of concussions among United States high school athletes in 20 sports. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:747-755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Master CL, Gioia GA, Leddy JJ, Grady MF. Importance of ‘return-to-learn’ in pediatric and adolescent concussion. Pediatr Ann. 2012;41(9):1-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williams RM, Welch CE, Parsons JT, Valovich McLeod TC. Athletic trainers’ familiarity with and perceptions of academic accommodations following sport-related concussion. J Athl Train. 2014. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Johnston K, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 3rd International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2008. J Inj Funct Rehabil. 2009;1:406-420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. Br J Sport Med. 2013;47:250-258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meehan WP, 3rd, Taylor AM, Proctor M. The pediatric athlete: younger athletes with sport-related concussion. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30:133-144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moser RS, Schatz P. A case for mental and physical rest in youth sports concussion: it’s never too late. Front Neurol. 2012;3:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pennington N. Head injuries in children. J Sch Nurs. 2010;26:26-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pew Health Professional Commission. Critical challenges: revitalizing the health professions for the twenty-first century. http://futurehealth.ucsf.edu/Public/Publications-and-Resources/Content.aspx?topic=Critical_Challenges_Revitalizing_the_Health_Professions_for_the_Twenty_First_Century. Accessed July 8, 2014

- 23. Valovich McLeod T, Gioia G. Cognitive rest: the often neglected aspect of concussion management. Athl Ther Today. 2010;15(2):1-3 [Google Scholar]