Abstract

Genetic manipulations with mammalian cells often require introduction of two or more genes that have to be in trans-configuration. However, conventional gene delivery vectors have several limitations, including a limited cloning capacity and a risk of insertional mutagenesis. In this paper, we describe a novel gene expression system that consists of two differently marked HAC vectors containing unique gene loading sites. One HAC, 21HAC, is stably propagated during cell divisions, therefore, it is suitable for complementation of a gene deficiency. The other HAC, tet-O HAC, can be eliminated, providing a unique opportunity for transient gene expression, e.g. for cell reprogramming. Efficiency and accuracy of a novel bi-HAC vector system have been evaluated after loading of two different transgenes into these HACs. Based on analysis of transgenes expression and HACs stability in the proof of principle experiments, the combination of two HAC vectors may provide a powerful tool towards gene and cell therapy.

Keywords: human artificial chromosome vector, gene expression, gene and cell therapy

Introduction

Human artificial chromosome (HAC)-based vectors represent a novel technology for gene delivery and expression with a potential to overcome the problems caused by virus-based vectors.1-4 Among these problems are a limited cloning capacity of viral vectors, a lack of a copy number regulation and integration into the host genome potentially leading to insertional mutagenesis and transgene silencing due to a positional effect.5-9 In contrast, all HACs contain a functional centromere and, therefore, do not integrate into the host genome. HAC vectors have essentially unlimited cloning capacity10,11 and, therefore, are able to carry genomic fragments up to several Mb. Thus, HAC-based gene delivery vectors open a way for a stable long-term expression of entire genetic loci. HACs have been generated using either ‘top-down’ approach or ‘bottom-up’ approaches.1,2,12,16 The ‘bottom-up’ approach of HAC generation is based on de novo kinetochore formation in human fibrocarcoma HT1080 cells transfected by higher-order repeat alphoid DNA arrays cloned into a circular BAC vector.17-20 The ‘top-down’ approach involves a telomere-associated chromosome fragmentation in homologous recombination-proficient chicken DT40 cells. We previously constructed HAC vectors from the human chromosome 21 by a ‘top-down’ chromosome engineering approach and adopted them for stable gene delivery.4,21 Human chromosome 21-derived HACs (21HACs) exhibit main characteristics desired for an ideal gene delivery vector, including a defined physical structure, stable episomal maintenance, and the capacity to carry large genomic loci with their regulatory elements, thus allowing a physiological regulation of the introduced gene in a manner similar to that of the native gene expression.22 Also, we previously reported the construction of a new generation of HAC vectors with a conditional centromere (tet-O HAC) using a ‘bottom-up’ approach.23-25 This removable tet-O HAC contains a tetracycline operator sequence (tet-O) in its centromeric region so that centromere function can be turned on or off by expression of tet-O binding proteins such as tTA, rtTA and tTS. The tet-O HAC was also physically characterized and its utility for gene delivery and gene function analysis was demonstrated.24-26 Thus, while both constructed HAC vectors have common features, they differ from each other by the opportunity to regulate transgene expression. While 21HACs provide stable gene expression in vitro and in vivo, 4,27,28 that is essential for correction of a gene deficiency, the tet-O HAC is specifically useful when a transient gene expression is needed. Such regulated expression is important for gene function studies as well as for cell reprogramming.29 In this study, we established a bi-HAC vector system using the 21HAC and the tet-O HAC for gene delivery.

Results and discussion

Rationale for the bi-HAC vector system

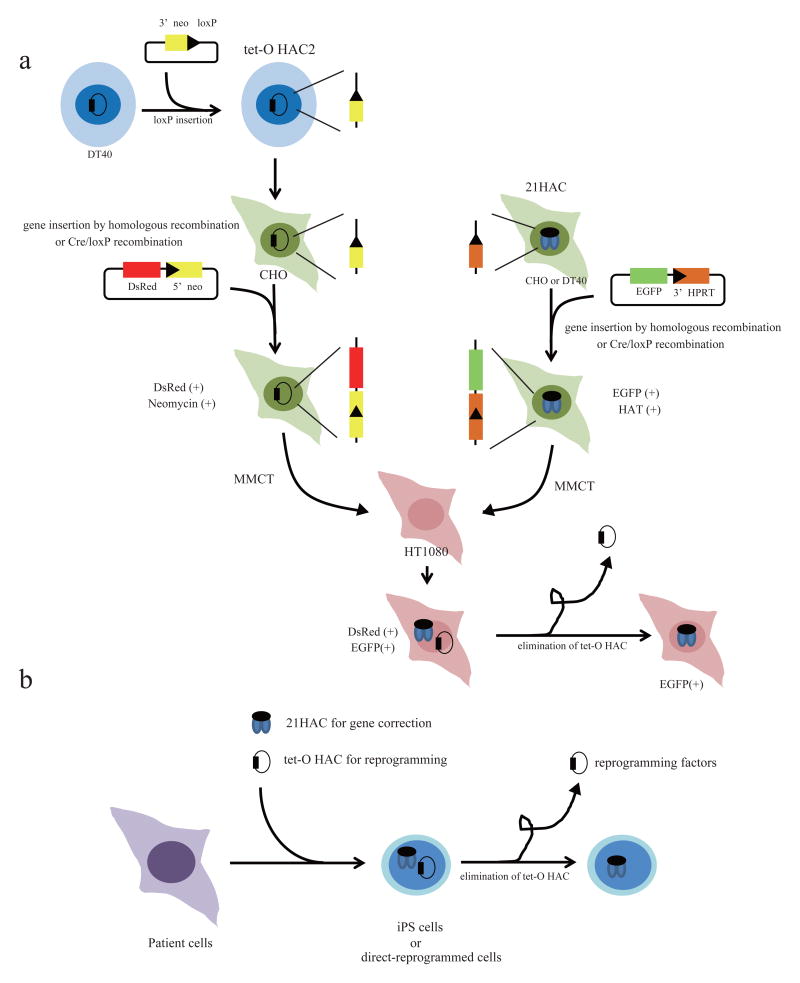

The overall strategy to establish a novel gene expression system using 21HAC and tet-O HAC vectors is shown in Figure 1. Transgenes of interest can be introduced into 21HAC and tet-O HAC vectors by Cre/loxP recombination in hamster CHO cells. Then both HACs are transferred from CHO cells into human cells via microcell-mediated chromosome transfer (MMCT).30,31 After stable transgenes expression from the HACs during several cell generations, expression of one of the transgene is selectively shutdown by elimination of a HAC carrying this transgene from the cells. Such bi-module gene expression system exploiting two types of HAC vectors can be applied to directly generate iPS cells with the following gene correction for regenerative medicine (Fig. 1b). For gene therapy, a gene of interest can be loaded into the 21HAC vector22,32,33 while Yamanaka 4 transcription factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc) cassette29 or direct-reprogramming factors34-36 can be loaded into the tet-O HAC vector that will be eliminated after cell reprogramming. Thus, such bi-HAC-based expression system could be a powerful tool for gene and cell therapy.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of a new gene expression system using 21HAC and tet-O HAC vectors.

(a) loxP cassette can be inserted to the HAC vector by homologous recombination in chicken DT40 cells. Genes of interest can be loaded into both 21HAC and tet-O HAC2 vector by Cre/loxP recombination in hamster CHO cells. 21HAC vector has a 5′ HPRT-loxP cassette and a tet-O HAC2 vector has a 3′neo-loxP cassette. After genes loading, both HAC vectors are transferred from hamster CHO cells to human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells via microcell-mediated chromosome transfer (MMCT). Two genes, DsRed and EGFP, are expressed in human cells. The tet-O HAC can be eliminated from the cells. (b) A rationale for generating iPS cells for gene correction using bi-HAC vectors system.

Construction of the tet-O HAC2 vector carrying a 3′neo-loxP cassette

In this study, as a proof of concept, we inserted the EGFP gene into the 21HAC1 vector and the DsRed gene into the tet-O HAC vector. Previously we reported loading of a transgene into the tet-O HAC carrying a 5′HPRT-loxP cassette by Cre/loxP recombination.24,25 Similarly, because the 21HAC2 has a 5′HPRT-loxP cassette, a transgene can be also loaded into this HAC by Cre/loxP recombination. These events are selected upon reconstitution of the functional HPRT gene using HAT media. Both HACs carry the Bsr gene as a selectable marker.

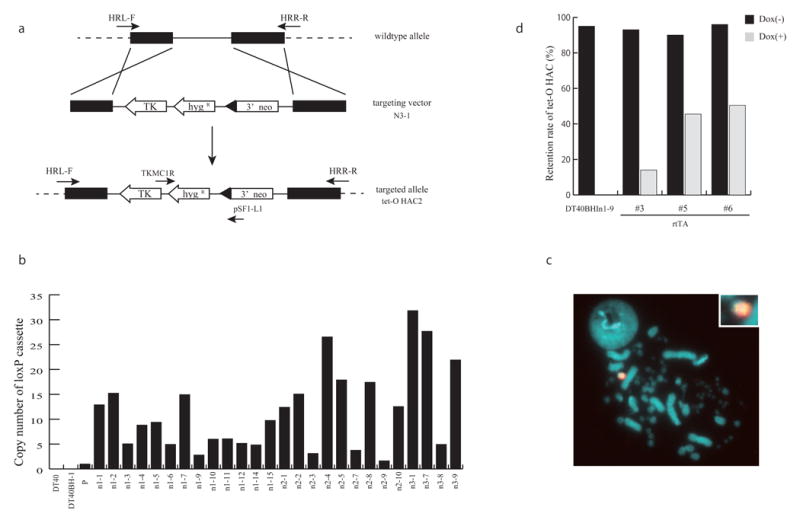

To distinguish these HACs, we constructed a derivative of the tet-O HAC vector which contains a 3′ Neo-loxP gene loading cassette. With this cassette gene loading events can be selected on reconstitution of the Neo gene. For this purpose, we built a new targeting vector, N3-1, a scheme of which is shown in Figure 2a. The 3′neo-loxP cassette containing the thymidine kinase (Tk) gene, hygromycin resistant (hyg) gene and the 3′ end of neomycin (neo) gene was introduced into the tet-O HAC by homologous recombination in chicken DT40 cells, producing tet-O HAC2. 42 hygromycin resistant clones were picked up. Three pairs of primers, HRL-F/pSF1-L1, TKMC1R/pSF1-L1 and TKMC1R/HRR-R, were used to confirm homologous recombination in the HAC. 26 out of 42 analyzed clones proved to be positive for homologous recombination events by PCR analysis (data not shown). The copy number of the 3′ neo-loxP cassette in transfectants was calculated by real-time PCR analysis (Fig. 2b). In these experiments, a BAC vector sequence in the tet-O HAC was used as an internal control. As previously was shown, the tet-O HAC contains approximately 30 copies of the BAC vector that has been used for assembly and propagation of the synthetic alphoid DNA array.23,26 One clone, DT40BHIn1-9 clone with a single copy of the loxP cassette was chosen for further experiments. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis proved that the loxP cassette was inserted into the tet-O HAC vector, producing tet-O HAC2 (Fig. 2c). To check whether the tet-O HAC2 can be removed from the cell by inactivation of its centromere, the DT40BHIn1-9 cells containing the tet-O HAC2 were transfected with the pTet-On advanced vector (TAKARA). The vector contains the reverse transcriptional transactivator (rtTA) and the Neo gene. After expression of rtTA that binds to tet-O sequences in the presence of doxycycline (dox) causing disruption of centrochromatin,23 the retention rate of the tet-O HAC2 was evaluated by FISH analysis. As seen from Figure 2d, seven days of culture after introduction of the rtTA gene containing vector resulted in a dramatic loss of the tet-O HAC2 when doxycycline was added into the medium. Thus, the tet-O HAC2 retains a conditional centromere after insertion of the 3′neo-loxP cassette.

Figure 2.

Construction of tet-O HAC2 vectors.

(a) Targeting of the N3-1vector containing the 3′neo-loxP cassette, the TK and hygro genes into the tet-O HAC. After homologous recombination in DT40 cells, the tet-O HAC2 was produced. A HRL-F/HRR-R set of primers confirms homologous recombination events. (b) Real-time PCR assay for estimation of the copy number of the loxP cassette in different clones. The DT40BHIn1-9 clone contains the tet-O HAC2 with one copy of the 3′neo-loxP cassette. (c) FISH analysis of DT40BHIn1-9 cells. FISH analysis was performed using a biotin-labelled probe (N3-1) for the loxP-containing cassette (green) and digoxigenin-labelled human Cot1 (red). (d) Elimination assay of the tet-O HAC2. The retention rate of the tet-O HAC2 was calculated 7 days after expression of the rtTA gene with or without doxycycline.

Loading of the DsRed transgene into the tet-O HAC2 in CHO cells

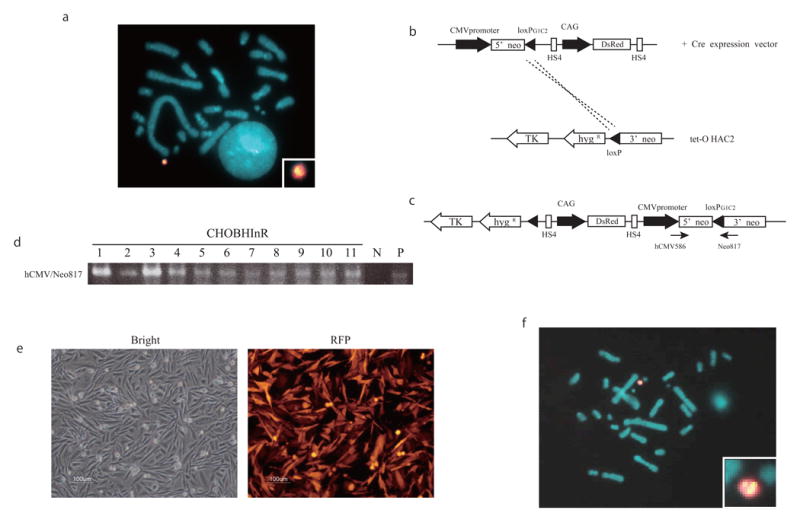

The tet-O HAC2 vector was then transferred from chicken DT40BHIn 1-9 cells to the hamster CHO cells. FISH analysis showed that the tet-O HAC2 was maintained in CHO cells without integration into the host genome (Fig. 3a). To perform site-specific gene targeting using Cre/loxP recombination, the DsRed gene construct and the Cre-recombinase expression vector were co-transfected into CHOBHIn 1-9-9 cells containing the tet-O HAC2 (Fig. 3b). After co-transfection, the transfectant cells were cultured under the G418 selection and eleven G418-resistant clones were picked up. The events of site-specific recombination for all these clones were confirmed by PCR using a set of diagnostic primers (hCMV586/Neo817) for the region flanking the loxP site (Fig. 3d). Also, FISH analysis showed that the DsRed transgene was loaded into the tet-O HAC2 vector (Fig. 3f). Moreover, in all analyzed CHO clones the DsRed gene was stably expressed at least for one month (data not shown). The representative bright-field and fluorescence images of the CHOBHInR-4 clone are shown in Figure 3e.

Figure 3.

Introduction of the DsRed gene into the tet-O HAC2 by Cre/loxP recombination in CHO cells. (a) FISH analysis of CHOBHI 1-9-9 cells which contain the tet-O HAC2. FISH was performed using a biotin-labeled probe for the loxP-containing cassette (green) and digoxigenin-labelled human Cot1 (red). (b) Introduction of the DsRed gene into the tet-O HAC2 vector by Cre/loxP recombination. The DsRed gene under control of the CAG promoter is flanked by chicken HS4 insulator sequences. (c) A map of the cassette in the tet-O-DsRed HAC2 vector after recombination events. (d) Genomic PCR analysis confirming a site-specific recombination. Primers hCMV586/Neo817 were used to detect Cre/loxP recombination. P: CHOBHInT-3 as positive control, N: CHOBHIn1-9-9 as negative control (e) Bright-field and fluorescence images of CHOBHInR cells containing the tet-O-DsRed HAC2 vector. (f) FISH analysis of the CHOBHInR cells. A biotin-labeled probe for the DsRed gene (green) and digoxigenin-labeled human COT1 (red) were used to detect the tet-O-DsRed-HAC2 vector.

Mitotic stability of 21HAC2 and tet-O HAC2 vectors propagated in the same human host cells

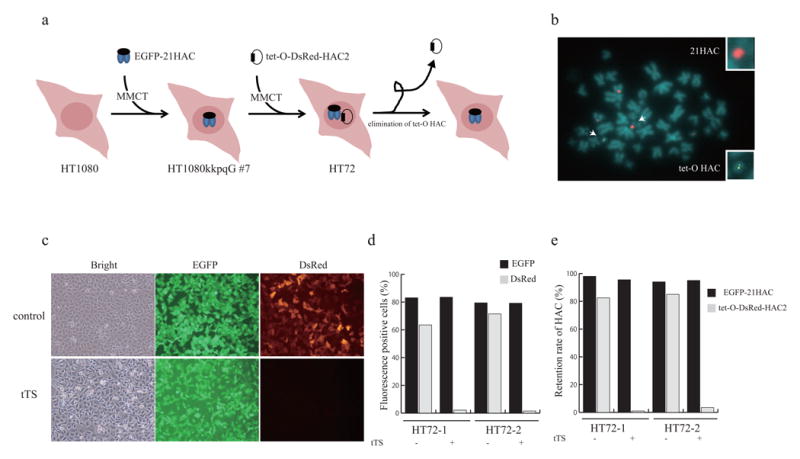

To investigate a behavior of two different HAC vectors propagated in the same cells, each HAC was transferred into human HT1080 cells (Fig. 4a). Previously, the 21HAC2 carrying the EGFP gene was transferred to HT1080 cells via MMCT resulting to the clone HT1080kkpqG-7.4 In this work, the tet-O HAC2 carrying the DsRed gene was transferred from the CHOBHInR-4 cells to HT1080kkpqG-7 via MMCT. Under a double selection on G418 and Blasticidin S, two clones, HT72-1 and HT72-2, were obtained. Although the transgene is likely to be silencing in the tet-O HAC2 compared to 21HAC, both EGFP and DsRed transgenes were stably expressed in longtime culture of HT72-1 and HT72-2 cells (data not shown). FISH analysis using two probes, a biotin-labeled probe for detecting the DsRed gene located on the tet-O HAC2 and a digoxigenin-labeled p11-4 probe for detecting the EGFP-21HAC showed that both HACs are maintained autonomously in host human cells (Fig. 4b). It is known that the tet-O HAC vector can be eliminated from cells by turning off its centromere. To confirm that this feature retained in human cells carrying two HACs, the tTS transgene was introduced into HT1080 cells using the Sendai virus. Note that Sendai virus-induced tTS expression was more efficient in elimination of the tet-O HAC than plasmid-induced expression in human cells (data not shown) that is likely due to the difference in levels of the tTS expression. As known, the fusion protein of tet-R and the Kruppel-associated box (KRAB)-AB silencing domain of the Kid-1 protein (tTS) binds to the tet-operator sequences in the tet-O HAC vector in the absence of doxycycline, resulting in inactivation of the HAC centromere followed by its loss from the cell.23,24 After tTS expression, the infected cells were cultured 7 days without doxycycline. Bright-field and fluorescence images showed that the DsRed gene expression disappeared drastically while EGFP expressed stably when the cells were grown without selection (Fig. 4c). To determine the percentage of fluorescence positive cells, FACS analysis was performed. As shown in Figure 4d, more than 90% of cells did not express the DsRed gene while they stably expressed the EGFP gene. To confirm that this is not due to gene silencing, the retention rate of the HACs was determined by FISH. FISH analysis showed that the 21HAC2 was retained in human cells stably while the tet-O HAC2 was lost with a high frequency (Fig. 4e). These results clearly indicate that disappearance of a red signal was caused by the tet-O HAC2 loss but not DsRed silencing.

Figure 4. Human HT1080 cells carrying the 21HAC2 and tet-O HAC2 vectors expressing the EGFP and DsRed genes.

(a) Scheme of transferring the EGFP-21HAC2 and tet-O-DsRed-HAC2 vectors and elimination of the tet-O-DsRed-HAC2 vector after expression of the tTS gene. (b) FISH analysis of the HT72 cells carrying EGFP-21HAC2 and tet-O-DsRed-HAC2 vectors. FISH analysis was performed using a biotin-labeled probe for the DsRed gene (green) and digoxigenin-labeled p11-4 (a hChr.21-derived α-satellite clone) (red). (c) Bright-field and fluorescence images of HT72 cells after elimination of the tet-O-DsRed-HAC2 vector. (d) FACS analysis was performed to detect the EGFP and DsRed genes expression 7 days after introduction of the tTS gene. (e) The retention rate of the EGFP-21HAC2 and tet-O-DsRed-HAC2 vectors was calculated by FISH analysis 7 days after introduction of the tTS gene. 200 interphase were counted for calculating the retention rate of HACs.

Together, these data show that the two types of HACs constructed by ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ approaches and marked by different selectable markers can be efficiently and accurately co-transferred into the same human cells via MMCT where both HACs are stably maintained. In new host cells one of the HACs, the tet-O HAC with a conditional centromere, can be selectively eliminated when further expression of a transgene inserted into this HAC is not required. For example, 21HAC with 4 reprogramming factors could produce iPS cells only following its spontaneous loss from the cells.37 Thus, our results demonstrate a proof of principle for a new bi-HAC based expression system for synthetic biology as well as cell reprogramming and correction of genetic disorders and genetic interaction.

Summary and conclusion

For gene and cell therapies, gene delivery vectors should have several defining characteristics, i.e. a long-term stable retention in target cells without chromosomal integration, an appropriate level of the therapeutic gene expression and no risk of cellular transformation or trigger of cancer. Although a number of advanced gene delivery virus-based vectors (such as retroviral, adenoviral and adeno-associated virus-based vectors) have been constructed, none of them match either all or some of these criteria. For the past decade, human artificial chromosome (HAC)-based vectors have been considered as an alternative technology for gene delivery and expression with a potential to overcome the problems caused by the use of viral-based vectors. Nevertheless until recently, HACs have not been recognized widely because of uncertainties of their structure and absence of a unique gene acceptor site. The situation has changed few years ago after engineering of two advanced HACs, 21HAC generated by truncation of human chromosome 21 and tet-O HAC generated from a synthetic alphoid DNA array containing tetracycline operator (tetO) sequences embedded into the alphoid DNA.23 21HAC was successfully used for complementation of gene deficiencies and creation of transgenic mice. A particularly impressive example is development of mice carrying a 21HAC expressing the entire 2.4 Mb human dystrophin (DYS) gene.22,33 One powerful advantage of the tet-O HAC is that its centromere can be inactivated by expression of tet-repressor (tetR) fusion proteins. Such inactivation results in HAC loss during subsequent cell divisions. This feature of the tet-O HAC provides a unique possibility to compare the phenotypes of the human cell with and without a functional copy of a transgene, i.e. the phenotypes arising from stable gene expression can be reversed when cells are “cured” of the HAC by inactivating its kinetochore in proliferating cell populations.24,25 This feature of the tet-O HAC may be also exploited for generation of pluripotent stem (iPS) cells and direct-reprogrammed cells when a transient expression is required. Although transfer rate of HAC vector is low, a new methods of MMCT which provide a highly transfer ratio have been reported.38

In this study, we investigated whether a bi-HAC based system can be applied for cell reprogramming and correction of gene deficiency. For the first time, our results demonstrated that two different HAC vectors are stably maintained in the same host cells and one of them, if necessary, can be selectively eliminated from cells by inactivation of its centromere. Based on different features of these HACs we propose that one of the HACs, 21HAC, which is stably maintained in human cells and in mice may be used for loading of a therapeutical gene while another HAC, tet-O HAC, which has a conditional centromere, is unique for transient expression of reprogramming factors. In addition, the bi-HAC system can be a powerful tool for studies on genetic interaction and synthetic biology.

Methods

Construction of targeting vectors

The targeting vector, N3-1, for introducing a 3′ neo-loxP/hyg/tk cassette was constructed as follows: the thymidine kinase gene was isolated by digestion with RsrII from the pKO selectTK V830 vector (Lexicon Genetics, Woodlands, TX) and inserted into the HindIII site of pKO Scrambler V901 backbone vector (Lexicon Genetics, Woodlands, TX) after blunting and dephosphorylation reactions (vector V901 TK). Two 2.0 kb and 3.1 kb fragments for homologous arms corresponding to the tet-O HAC were amplified by PCR using primers HR1-Fi/Ri 5′-AGAGTTAACGTTACCTTCCACGAGCAAAACACGTA-3′ and 5′-AGAGTTAACCTTGTAGGCCTTTATCCATGCTGGTT-3′, HR3S-F/R 5′-ATACCGCGGGTTCTGTGTTCATTAGGTTGTTCTGT-3′ and 5′-ATACCGCGGTGAAGCGTATATAGGACGAGTAACTG-3′, digested with either HpaI or SacII and were subsequently ligated into the equivalent sites of the vector V901 TK, respectively (vector 5-4). The PGK/hyg gene was isolated from the vector 5′HPRT-loxP-Hyg-TK with KpnI/ClaI digestion and blunt-ligated with the KpnI-digested vector 5-4 (vector N-3). A part of the neomycin resistant gene with the loxP site from the pSF1 vector (Gibco) was inserted into the XhoI/BamHI site of the N-3, producing the N3-1 vector.

Cell culture

DT40 cells containing the tet-O HAC were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium 1640 (RPMI-1640, GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biowest, Nuaille, France), 1% chicken serum (Invitrogen), 50 µM 2-melcaptometanol (SIGMA) and 15 µg/ml Blasticidin S hydrochloride (Funakoshi, Tokyo, Japan) at 40°C in 10% CO2. After introduction of the DsRed gene, CHO cells retaining the tet-O-DsRed-HAC were maintained in Ham's F-12 nutrient mixture (Invitrogen) plus 10% fetal bovine serum with 800 µg/ml G418 (Calbiochem). HT1080 cells containing the EGFP-21HAC were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM, SIGMA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biowest, Nuaille, France) and with 4 µg/ml Blasticidin S at 37°C in 5% CO2. After transfer of the tet-O-DsRed-HAC, HT1080 cells containing both HACs were cultured with 4 µg/ml Blasticidin S and 400 µg/ml G418.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

FISH analyses were performed using either fixed metaphase or interphase spreads of each cell hybrid using digoxigenin-labeled (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) human Cot-1 DNA (Invitrogen) and biotin-labeled plasmid DNA as previously described.23,24 Chromosomal DNA was counterstained with DAPI (Sigma, St Louis, MD, USA). To detect two types of HACs, a digoxigenin-labeled p11-4 (a hChr.21-derived α-satellite clone) probe which detects human chromosome 13 and 21 was used. The images were captured using the Argus system (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan) and NIS elements (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Microcell-mediated chromosome transfer (MMCT)

MMCT was performed as described previously.28 The tet-O HAC containing a 3′neo-loxP cassette was transferred from the DT40 cells to the CHO hprt-/- cells via MMCT. Microcells were collected by centrifugation of 1×109 DT40 cells attached on flasks (Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY) with poly-L-lysine (Sigma) and were fused with 1×106 CHO cells by 47% polyethylene glycol 1000 (WAKO, Osaka, Japan). After introduction of the DsRed gene, the tetO-DsRed-HAC2 was transferred from hamster CHO cells to human HT1080 cells using a MMCT procedure as previously described.4 The 21HAC carrying the EGFP gene (21HAC2) was transferred from CHO cells into HT1080 cells via MMCT.

Rea-ltime PCR analysis

Real-time PCR was performed to determine the copy number of loxP cassette in DT40 cells as described previously.23

FACS analysis

Mitotic stability of the HAC carrying the EGFP and DsRed gene was determined by FACS as described previously.24

Genomic PCR analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from cells using a genomic extraction kit (Gentra System, Minneapolis, MN). PCR analyses were carried out using standard techniques. The primer sets for the detection of the tet-O HAC2 were HRL-F/pSF1-L1 5′-CAGAGCCAGACAGGAAGGAATAATGTCAAG-3′ and 5′-TCGTCCTGCAGTTCATTCAG-3′. The primer pairs for the confirmation of the targeted loxP cassette region on the tet-O HAC were TKMC1R/pSF1-L1 5′-TGAAAACCACACTGCTCGAC-3′ and 5′-CAGAGCCAGACAGGAAGGAATAATGTCAAG-3′, TKMC1R/HRR-R 5′-TGAAAACCACACTGCTCGAC-3′ and 5′-GCATCTCAATTAGTCAGCAACCATAGTCCC-3′. The primer pairs for the detection of the neomycin resistant gene reconstruction were hCMV586/Neo817 5′-CGTAACAACTCCGCCCCATT-3′ and 5′-GCAGCCGATTGTCTGTTGTG-3′.

Elimination assay of the tet-O HAC

The tTS fusion protein was expressed in HT72 cells containing the 21HAC2 and the tet-O HAC2 using the Sendai-Virus vector. The Sendai Viral supernatant (MOI=20) was added to HT72 cells. The infected cells were cultured with or without 1 µg/ml of doxycycline (dox). After 7 days of culture, FACS and FISH analysis were performed to calculate the retention rate of the HAC vectors and expression of EGFP and DsRed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tetsuya Ohbayashi, Hiroyuki Kugoh, Masako Tada, Masaharu Hiratsuka and Satoshi Abe at Tottori University for valuable discussions. This study was supported in part by JST, CREST (MO) and the 21st Century Center of Excellence (COE) program from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MO), the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, USA (V.L.).

References

- 1.Kazuki Y, Oshimura M. Human artificial chromosomes for gene delivery and the development of animal models. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1591–1601. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kouprina N, Earnshaw WC, Masumoto H, Larionov V. A new generation of human artificial chromosomes for functional genomics and gene therapy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:1135–1148. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1113-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oshimura M, Kazuki Y, Iida Y, Uno N. New vectors for Gene Delivery: Human and mouse artificial chromosomes. eLS. 2013 doi: 10.1002/9780470015902.a0024474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazuki Y, Hoshiya H, Takiguchi M, Abe S, Iida Y, Osaki M, Katoh M, Hiratsuka M, Shirayoshi Y, Hiramatsu K, Ueno E, Kajitani N, Yoshino T, Kazuki K, Ishihara C, Takehara S, Tsuji S, Ejima F, Toyoda A, Sakaki Y, Larionov V, Kouprina N, Oshimura M. Refined human artificial chromosome vectors for gene therapy and animal transgenesis. Gene Ther. 2011;18:384–393. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Connor TP, Crystal RG. Genetic medicines: treatment strategies for hereditary disorders. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:261–276. doi: 10.1038/nrg1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giraldo P, Montoliu L. Size matters: use of YACs, BACs and PACs in transgenic animals. Transgenic Res. 2001;10:83–103. doi: 10.1023/a:1008918913249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, McCormack MP, Wulffraat N, Leboulch P, Lim A, Osborne CS, Pawliuk R, Morillon E, Sorensen R, Forster A, Fraser P, Cohen JI, de Saint Basile G, Alexander I, Wintergerst U, Frebourg T, Aurias A, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Romana S, Radford-Weiss I, Gross F, Valensi F, Delabesse E, Macintyre E, Sigaux F, Soulier J, Leiva LE, Wissler M, Prinz C, Rabbitts TH, Le Deist F, Fischer A, Cavazzana-Calvo M. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science 17. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pravtcheva DD, Wise TL. A postimplantation lethal mutation induced by transgene insertion on mouse chromosome 8. Genomics. 1995;30:529–544. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrick D, Fiering S, Martin D, Whitelaw E. Repeat-induced gene silencing in mammals. Nat Genet. 1998;18:56–59. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuroiwa Y, Tomizuka K, Shinohara T, Kazuki Y, Yoshida H, Ohguma A, Yamamoto T, Tanaka S, Oshimura M, Ishida I. Manipulation of human minichromosomes to carry greater than megabase-sized chromosome inserts. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:1086–1090. doi: 10.1038/80287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kazuki Y, Kobayashi K, Aueviriyavit S, Oshima T, Kuroiwa Y, Tsukazaki Y, Senda N, Kawakami H, Ohtsuki S, Abe S, Takiguchi M, Hoshiya H, Kajitani N, Takehara S, Kubo K, Terasaki T, Chiba K, Tomizuka K, Oshimura M. Trans-chromosomic mice containing a human CYP3A cluster for prediction of xenobiotic metabolism in humans. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:578–92. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basu J, Willard HF. Human artificial chromosomes: potential applications and clinical considerations. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:843–853. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farr CJ, Stevanovic M, Thomson EJ, Goodfellow PN, Cooke HJ. Telomere-associated chromosome fragmentation: applications in genome manipulation and analysis. Nat Genet. 1992;2:275–282. doi: 10.1038/ng1292-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heller R, Brown KE, Burgtorf C, Brown WR. Mini-chromosomes derived from the human Y chromosome by telomere directed chromosome breakage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7125–7130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrington JJ, Van Bokkelen G, Mays RW, Gustashaw K, Willard HF. Formation of de novo centromeres and construction of first-generation human artificial microchromosomes. Nat Genet. 1997;15:345–355. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandegar MA, Moralli D, Khoja S, Cowley S, Chan DY, Yusuf M, Mukherjee S, Blundell MP, Volpi EV, Thrasher AJ, James W, Monaco ZL. Functional human artificial chromosomes are generated and stably maintained in human embryonic stem cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2905–2913. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeno M, Grimes B, Okazaki T, Nakano M, Saitoh K, Hoshino H, McGill NI, Cooke H, Masumoto H. Construction of YAC-based mammalian artificial chromosomes. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:431–439. doi: 10.1038/nbt0598-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kereso J, Praznovszky T, Cserpan I, Fodor K, Katona R, Csonka E, Fatyol K, Hollo G, Szeles A, Ross AR, Sumner AT, Szalay AA, Hadlaczky G. De novo chromosome formations by large-scale amplification of the centromeric region of mouse chromosomes. Chromosome Res. 1996;4:226–239. doi: 10.1007/BF02254964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Telenius H, Szeles A, Kereso J, Csonka E, Praznovszky T, Imreh S, Maxwell A, Perez CF, Drayer JI, Hadlaczky G. Stability of a functional murine satellite DNA-based artificial chromosome across mammalian species. Chromosome Res. 1999;7:3–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1009215026001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki N, Nishii K, Okazaki T, Ikeno M. Human artificial chromosomes constructed using the bottom-up strategy are stably maintained in mitosis and efficiently transmissible to progeny mice. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26615–26623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katoh M, Ayabe F, Norikane S, Okada T, Masumoto H, Horike S, Shirayoshi Y, Oshimura M. Construction of a novel human artificial chromosome vector for gene delivery. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;20:280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoshiya H, Kazuki Y, Abe S, Takiguchi M, Kajitani N, Watanabe Y, Yoshino T, Shirayoshi Y, Higaki K, Messina G, Cossu G, Oshimura M. A highly stable and nonintegrated human artificial chromosome (HAC) containing the 2.4 Mb entire human dystrophin gene. Mol Ther. 2009;17:309–317. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakano M, Cardinale S, Noskov VN, Gassmann R, Vagnarelli P, Kandels-Lewis S, Larionov V, Earnshaw WC, Masumoto H. Inactivation of a human kinetochore by specific targeting of chromatin modifiers. Dev Cell. 2008;14:507–522. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iida Y, Kim JH, Kazuki Y, Hoshiya H, Takiguchi M, Hayashi M, Erliandri I, Lee HS, Samoshkin A, Masumoto H, Earnshaw WC, Kouprina N, Larionov V, Oshimura M. Human artificial chromosome with a conditional centromere for gene delivery and gene expression. DNA Res. 2010;17:293–301. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JH, Kononenko A, Erliandri I, Kim TA, Nakano M, Iida Y, Barrett JC, Oshimura M, Masumoto H, Earnshaw WC, Larionov V, Kouprina N. Human artificial chromosome (HAC) vector with a conditional centromere for correction of genetic deficiencies in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20048–20053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114483108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kouprina N, Samoshkin A, Erliandri I, Nakano M, Lee HS, Fu H, Iida Y, Aladjem M, Oshimura M, Masumoto H, Earnshaw WC, Larionov V. Organization of synthetic alphoid DNA array in human artificial chromosome (HAC) with a conditional centromere. ACS Synth Biol. 2012;1:590–601. doi: 10.1021/sb3000436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinohara T, Tomizuka K, Takehara S, Yamauchi K, Katoh M, Ohguma A, Ishida I, Oshimura M. Stability of transferred human chromosome fragments in cultured cells and in mice. Chromosome Res. 2000;8:713–725. doi: 10.1023/a:1026741321193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomizuka K, Yoshida H, Uejima H, Kugoh H, Sato K, Ohguma A, Hayasaka M, Hanaoka K, Oshimura M, Ishida I. Functional expression and germline transmission of a human chromosome fragment in chimaeric mice. Nat Genet. 1997;16:133–143. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fournier RE, Ruddle FH. Microcell-mediated transfer of murine chromosomes into mouse, Chinese hamster, and human somatic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:319–323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.1.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meaburn KJ, Parris CN, Bridger JM. The manipulation of chromosomes by mankind: the uses of microcellmediated chromosome transfer. Chromosoma. 2005;114:263–274. doi: 10.1007/s00412-005-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurosaki H, Hiratsuka M, Imaoka N, Iida Y, Uno N, Kazuki Y, Ishihara C, Yakura Y, Mimuro J, Sakata Y, Takeya H, Oshimura M. Integration-free and stable expression of FVIII using a human artificial chromosome. J Hum Genet. 2011;56:727–733. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kazuki Y, Hiratsuka M, Takiguchi M, Osaki M, Kajitani N, Hoshiya H, Hiramatsu K, Yoshino T, Kazuki K, Ishihara C, Takehara S, Higaki K, Nakagawa M, Takahashi K, Yamanaka S, Oshimura M. Complete genetic correction of ips cells from Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol Ther. 2010;18:386–393. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ieda M, Fu JD, Delgado-Olguin P, Vedantham V, Hayashi Y, Bruneau BG, Srivastava D. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell. 2010;142:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sekiya S, Suzuki A. Direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to hepatocyte-like cells by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:390–393. doi: 10.1038/nature10263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, Kokubu Y, Südhof TC, Wernig M. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature. 2010;463:1035–1041. doi: 10.1038/nature08797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hiratsuka M, Uno N, Ueda K, Kurosaki H, Imaoka N, Kazuki K, Ueno E, Akakura Y, Katoh M, Osaki M, Kazuki Y, Nakagawa M, Yamanaka S, Oshimura M. Integration-free iPS cells engineered using human artificial chromosome vectors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katoh M, Kazuki Y, Kazuki K, Kajitani N, Takiguchi M, Nakayama Y, Nakamura T, Oshimura M. Exploitation of the interaction of measles virus fusogenic envelope proteins with the surface receptor CD46 on human cells for microcell-mediated chromosome transfer. BMC Biotechnol. 2010;10:37. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-10-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]