Abstract

Despite the widely recognized benefits of daily play, recreation, sports, and physical education on the physical and psychosocial well-being of children and adolescents, many contemporary children and adolescents worldwide do not meet the recommendations for daily physical activity. The decline in physical activity seems to start early in life which leads to conditions characterized by reduced levels of physical activity in the pediatric population that are inconsistent with current public health recommendations. Unlike many other diseases and disorders in pediatrics, physical inactivity in youth is unique in that it currently lacks a clinical gold standard for diagnosis. This makes the diagnosis and treatment medically challenging, though no less important, as the resultant ramifications of a missed diagnosis are of significant detriment. Exercise deficient children need to be identified early in life and treated with developmentally appropriate exercise programs designed to target movement deficiencies and physical weaknesses in a supportive environment. Without such interventions early in life, children are more likely to become resistant to our interventions later in life and consequently suffer from adverse health consequences. Integrative approaches that link health care professionals, pediatric exercise specialists, school administrators, community leaders, and policy makers, may provide the best opportunity to promote daily physical activity, reinforce desirable behaviors, and educate parents about the exercise-health link. If health care providers miss the window of opportunity to identify exercise deficit disorder in youth and promote healthy lifestyle choices, the eventual decline and disinterest in physical activity will begin to take shape and new health care concerns will continue to emerge.

INTRODUCTION

The health of a population may be assessed via psychological, social and physical measures including mental health, tobacco use, nutritional status and physical activity habits.73 Despite noteworthy advancements in both medicine and technology, most health measures of the United States population are getting worse, as obesity and weight-related co-morbidities continue to increase.22, 49 Obesity, despite being the most preventable cause of mortality in the United States and worldwide, continues to increase at an alarming rate among children and adults. Currently, ~365,000 deaths are attributed to poor diet and physical inactivity in the United States per annum.38 Since the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in the 1960’s, the prevalence of overweight and obese children aged 6–11 years has increased 3-fold (4.2% in the early 1960’s to 15.8% in 2002).22 Alarmingly, more recent forecasts indicate that by the year 2030, 42 % of the American population will be obese, with severe obesity prevalence increasing 130% over these next two decades.21 While the etiology for the observed decline in child and adult health is likely multifactorial, a reduction in physical activity may well be an underlying mechanism. Particularly troubling are recent epidemiological reports indicating that contemporary youth are not as active as children should be or used to be,5, 47, 69 and the decline and disinterest in physical activity progresses steadily after age six.25, 32, 69

Obesity, despite being the most preventable cause of mortality worldwide, continues to increase at an alarming rate among children and adults. Without a change in management strategies these trends are unlikely to change. In addition, healthcare efforts targeting overweight or obese youth will continue to encourage disease-oriented treatment strategies which are likely to be ineffective long term.51, 64 The increased prevalence of physical inactivity in school-age children may be exacerbated by recent school budget constraints, lack of qualified physical education professionals, and the widespread implementation of standardized academic testing programs.60 Collectively, these factors contribute to a negative impact on the time and resources available for health and physical education programs designed to provide students with the knowledge, skills, and confidence they need to regularly engage in a variety of physical activities.

Today, children are provided nearly continuous opportunity for screen time (TV, Video games, computers and cell phones) at the cost of opportunities for physical activity (Figure 1). As no child is immune from our contemporary lifestyle, a team approach that links physicians, physical educators, pediatric exercise specialists, and public health officials may be needed to identify youth at risk and to promote healthy lifestyle choices for all youth, regardless of body size or physical ability. Recent findings indicate that motor coordination is a predictor of physical activity in childhood.24, 26, 34 This emphasizes the importance of early recognition of motor skill deficiency in children and necessity of systematic instruction and skilled training to improve childhood motor proficiency during formative and developmental periods of life.

Figure 1.

Factors such as high sugar drinks (cola), candy, junk foods (chips) and excessive screen time (cell phone, television and gaming) can exacerbate negative health trajectories in children with poor motor skills and Exercise Deficit Disorder.

The need to identify and target deficiencies in muscle strength and motor skill ability early in childhood is critically important, as physical activity behaviors and lifestyle habits established during childhood tend to track into adulthood.65 Exercise deficit disorder (EDD) is a term recently introduced to the medical literature to describe a state of low physical activity which is inconsistent with current public health recommendations.16 It is unlike many other diseases and disorders; EDD is unique in that it does not have established clinical markers or laboratory tests to make the definitive diagnosis. Moreover, there are no medications to treat deficiencies in movement skill or physical activity. 12, 14, 15 As we have learned from casual smoking, the adverse health consequences arise from an initial lifestyle choice. Today smoking addiction is aggressively identified and treated due to the known benefits of timely intervention. Similarly sedentary lifestyles in youth may arise from environments that are not enriched with developmentally-appropriate physical activity outlets. Recent trends indicate that physical activity has become a leading risk factor for morbidity and mortality. Associated physical inactivity related outcomes are potentially magnified and lifestyle habits more resistant to change if they emerge during youth and adolescence. Consequently, sedentary youth need to be identified early in life and referred to pediatric exercise specialists who are specially equipped to intervene with developmentally-appropriate and enjoyable exercises that are designed to target movement deficiencies and physical weaknesses. Given the lack of effective medical treatment for physical inactivity, a preventive strategy consisting of the integration of physical fitness and enhancement of a child’s motor skill confidence and competence is needed to prevent the eventual decline and disinterest in this desired behavior. 39, 42, 44

Prior reports raise two fundamental questions: First, are contemporary youth prepared to participate daily in 60 minutes or more of moderate to vigorous physical activity in order to meet public health recommendations? Second, within our current health care system, who is qualified and willing to identify and treat children with EDD? The purpose of this review is to present an integrative model that links health care providers with pediatric exercise specialists. This model supports a synergistic approach to the identification of inactive children, and the development of a treatment plan, which enhances the health- and skill-related fitness of children and adolescents with different needs, goals, and abilities.

INTEGRATIVE HEALTH CARE

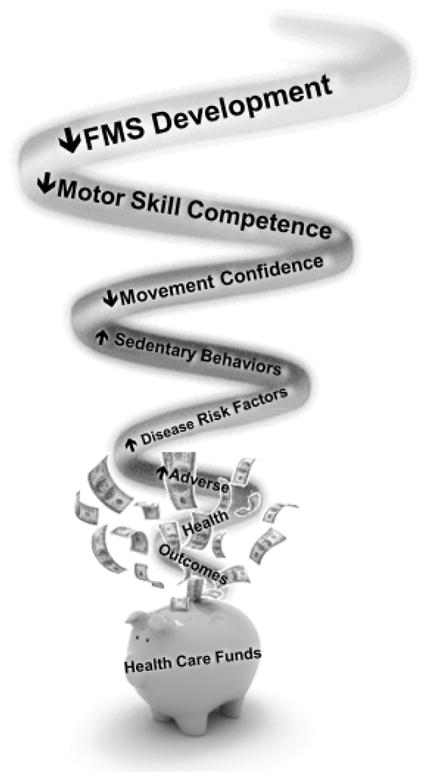

The potential impact of physical inactivity and obesity on health service utilization and costs during childhood has created a need for immediate action to manage and prevent high risk behaviors during this critical period of life.14, 19, 67 There is increasing evidence that sedentary behavior during childhood, may result in a vortex of physical inactivity culminating in negative health outcomes that will ultimately stress the health care system later in life (Figure 2).14, 19, 37, 59 This downward spiral, beginning with childhood inactivity and ending in poor health, emphasizes the crucial need for early identification and treatment of the physically inactive child, before he/she becomes resistant to our interventions.

Figure 2.

The cascade of adverse events that may result from a lack of fundamental movement skill (FMS) development during childhood. Interventions targeted to youth at risk for Exercise Deficit Disorder can be achieved with relatively inexpensive strategies and will likely demonstrate the great effectiveness. As children digress into the inactivity vortex, the related health care costs to treat deficits will show incremental increases and will likely be in most part ineffective which will further stress the health care system. Figure adapted from “Faigenbaum, A. D. and G. D. Myer (2012). “Exercise deficit disorder in youth: play now or pay later.” Curr Sports Med Rep 11(4): 196–200.” with permission from the editor.

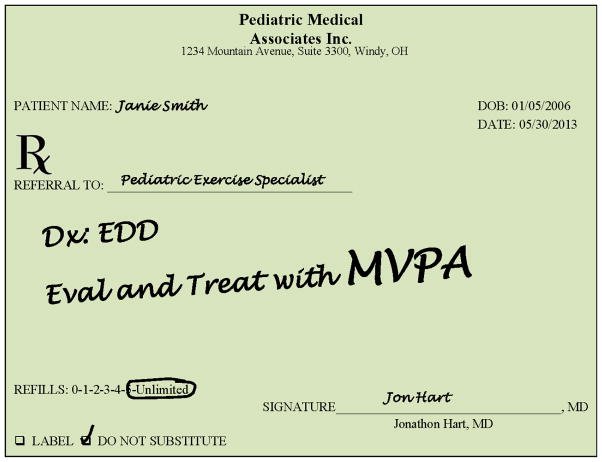

Primary care physicians, school nurses, and certified athletic trainers are well-positioned to promote injury-prevention strategies that enhance the health and well-being of children and adolescents.11, 15, 16, 61 While many health care providers perform routine screening surrounding vision, hearing, and body mass index (BMI), most interactions are essentially void of any meaningful assessment of physical activity.20 Providing clinicians with a method of identifying early and effectively the physically inactive child, enables timely intervention and treatment. 12 Once identified, the child with EDD can be referred to a pediatric exercise specialist who has the requisite pedagogical and physiological content knowledge to design, implement, and progress developmentally appropriate activity programs (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Example of prescription that supports physician referral to pediatric exercise specialist.

If exercise is medicine and a prescription of ‘exercise as medicine’ is expected, then why is medical education limited with instruction in exercise science? A recently published survey of sports and exercise medicine practitioners indicated that there was no substantive teaching of sports and exercise medicine in the core medical curricula in Australia, Canada, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, South Africa, or the USA.28 Physician training from medical school through specialty training may be limited in exercise science education as it applies to chronic illness, injury and obesity treatment and prevention despite a notable increase in interest from medical students.28 Currently, dollars are diminishing in support of physical activity (PA) for children, physical education is viewed as expendable in some communities, and there are no plausible means for reimbursement of physical activity interventions by trained healthcare and fitness professionals.

At this time, the health care balance scale is tipped significantly towards medical treatments and many physicians are looked upon as the source to implement preventative strategies. Unfortunately, physicians may be void of a referral base when faced with a physically inactive child diagnosed with EDD in need of care by a pediatric exercise specialist. Less than 2% of the over 300 United States colleges and universities offer a course in pediatric exercise within their curricula. In addition, less than 50% of physical therapy education programs in the United States require exercise science prerequisites.23 Moreover, only 7% of professional pediatric physical therapy education programs require a pediatric clinical education placement, therefore many practicing physical therapists have limited pediatric experience to develop health and wellness exercise programming for children.56 Thus, while we encourage physician referral to a pediatric exercise specialist, current educational curricula may limit the development of professionals trained with background to provide potential outlets for physician’s to target these referrals.

Confounding the potential for early identification and treatment of risk factors in youth with EDD, the current symptom-reactive health care system is not focused on prevention, but rather the treatment of the disease. This approach has been largely unsuccessful in the promotion of physical activity and the management of obesity and related disorders. This view is supported by the troubling increase in the prevalence of pre diabetes/diabetes from 9% to 23% in US adolescents aged 12 to 19 years.36 If exercise is medicine, then physicians and pediatric exercise specialists should be reimbursed for the evaluation and treatment of children with EDD with the goal of decreasing the likelihood of adverse health consequences later in life while reducing the future economic burden of lifestyle-related illnesses. Future prospective investigations are warranted to evaluate these contentions.

INTEGRATIVE EDUCATION

Physically active children and adolescents, as compared to their inactive counterparts, demonstrate increased levels of musculoskeletal strength, enhanced cardiorespiratory function and improved metabolic health.30, 62, 70 In 4th and 5th grade children, the addition of an after school soccer program effectively decreased BMI z-scores at three and six months and influenced increases in total daily, moderate and vigorous physical activity at three months.71 Furthermore, regular participation in well-designed sport programs is associated with increased energy expenditure and aerobic fitness levels compared with non-sports participants. Therefore, sports participation may be a potentially effective strategy to improve physical activity and health measures in children and adolescents who are prepared for the demands of sports practice and competition.50, 74 In young girls, sports team participation was associated with increased physical activity and reduced television viewing and BMI in a dose-response fashion.57 In this same pattern, fifth grade children who participated in recreational sport programs throughout the year (fall, winter, and spring) demonstrated a greater level of increased fitness performance than their peers who did not participate in any sport or who only participated in one sport.27

Continuing on, in a 10-year longitudinal study of 630 adolescents, the participants first became involved in organized youth sports clubs between the ages 6–10 years.29 Interestingly, those who reported becoming members of a sports team at an earlier age were more physically active as adults than adolescents who initiated sports involvement at older ages.29 It is possible that the improved motor competence and muscle strength developed with structured physical activity and play throughout the growing years facilitates the establishment of desired behaviors and habits that may carry over into adulthood.35 Regular participation in sports, play, recreation and planned exercise designed to improve physical fitness during childhood and adolescence may provide an optimal mechanism for promoting physical activity as an ongoing lifestyle choice.52, 53, 68, 73

If children grow up in an environment that is deficient in opportunities to regularly participate in a variety of health-enhancing and skill-building activities, they may be less likely to engage in more challenging activities later in life and more likely to suffer from the adverse consequences of a sedentary lifestyle. This view is supported by the work of Lopes et al. (2010) who reported that 6-year-old children with low and average levels of motor coordination had lower levels of physical activity 5 years later compared with children with high motor coordination.33 Others noted that low levels of physical activity significantly increased the risk of injury in children during physical education, recreation, and sports.6 Of interest, in the aforementioned report the researchers found that the steepest increase in injury risk was for the quartile with the lowest habitual physical activity, and the cut-off for this level was 5 hours of physical activity per week.6

In the United States, school-based sports teams and community-based recreation programs are the most viable means for children and adolescents to participate in structured physical activity. These programs are often coached by well-meaning adults who may not have the requisite content knowledge or understanding of the physical and psychosocial uniqueness of school age youth. While sports and recreation programs provide a mechanism to increase MVPA and enhance motor skill development, recent reports indicate that regular participation in organized youth sports does not ensure adequate exposure to regular physical activity.31, 55 In addition, sports and recreational activities without preparatory neuromuscular conditioning may increase risk of injury in these young children and adolescents.63.6 While regular sports participation during childhood and adolescence is positively associated with improvements in cardiovascular, musculoskeletal and metabolic health, recent findings indicate that a sports related knee injury during the growing years can initiate unfavorable changes (increased BMI-Z score and body fat percentage) in body composition. 40 Thus, children identified with EDD may not be (mentally or physically) prepared to initiate sporting activities. Referral to a pediatric exercise scientist can help in the programming of physical activity that can support the development of motor skills and muscular strength that are needed for game play and sport participation.

Youth who are not adequately prepared for the demands of sports training and competition may be at increased risk for injury, reduced physical activity and consequent unhealthy weight gain.40 In addition, the drastic and sudden reduction in physical activity from either chronic pain or acute injury may initiate a “negative spiral of disengagement” whereby reduced physical activity leads to diminished cardiorespiratory fitness, increased adiposity and poor health outcomes.59 Ultimately, injury during childhood sports and recreation, may initiate a cascade of adverse health effects which may manifest as sedentary lifestyle habits during adulthood.1, 2, 42, 44, 58 For example, young girls who reported new knee injuries demonstrated significantly greater increase in BMI z-score and body fat percentage relative to their uninjured peers within one year of the reported injury.46 A qualified pediatric exercise specialist who possesses a specialized body of knowledge and skills is needed to develop, implement and progress age-related exercise interventions that allow children to meet the desired objectives while learning about the benefits of an active lifestyle. There are strong inverse relationships between parental and child perceptions of injury risk and physical activity. As fear related concerns centered around injury and reduction in physical activity are greatest in children who are 9–11 years of age, implementing injury prevention programs as well as educating parents about safe sporting and physical activity opportunities is likely optimal and important for children 7–8 years of age.66

The reduction of physical education, team sports and organized recreation programs in some communities has negatively impacted the resources available to expose youth to a variety of positive experiences that can promote and encourage participation in physical activity as an on ongoing lifestyle choice.7, 48, 54 Many school districts have reduced time for health and physical education resulting in less athletic students and fewer opportunities for them to expand their physical, social and problem-solving skills in the context of games, play and structured fitness activities. Presently, at the elementary school level only three states in the country require the nationally recommended 150+ minutes per week/30 minutes per day of physical education and 59% of states allow required physical education credits to be earned through online courses.48 Of note, the median physical education budget for schools in the United States is only $764 per school year.48 Furthermore, funding for afterschool programs and athletics may be limited due to district attempts to preserve staffing, transportation and academic programming.

Since physical inactivity is now recognized as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality,73 long-term initiatives that aim to maintain participation in physical activity throughout one’s lifespan while reducing the risk of obesity and related disorders in children are warranted.60 Budgetary constraints and insular views that influence funding for and attitudes towards physical education, team sports and after school recreation programs, limit the potential for all youth to meet current recommendations for physical activity in a positive learning atmosphere.7 Without qualified professionals who are trained to work with inactive youth and help them develop the competence and confidence to be physically active early in life, it is unlikely that current trends in physical inactivity and childhood obesity will regress.

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT FOR EXERCISE DEFICIT DISORDER

A child’s level of physical activity is influenced by extrinsic factors (e.g., environment, family, peers, socioeconomic status, culture and self-efficacy) that may affect their desire and ability to be physically active. Recent public health recommendations now promote aerobic training and muscle strengthening exercise activities that focus on the development of cardiorespiratory and musculoskeletal health and fitness.70, 73 However, general physical activity recommendations for school-age children (i.e. at least 60 minutes/day of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) 70, 72 may be suboptimal for children and adolescents who need to develop fundamental motor skills (e.g., jumping, throwing and balancing) that will support participation in a variety of physical activities that are part of a healthy lifestyle. 3, 4, 26, 42 Youth with reduced motor skill competence and low levels of perceived confidence in their physical abilities may be less willing and able to participate in competitive sports. Moreover, inactive youth often find prolonged periods of aerobic exercise to be boring or discomforting.42 The questions then remain as to what are the ideal programs required to adequately prepare children for safe participation in sport and recreation programs, and who is qualified to design and implement physical developmental programs for children?

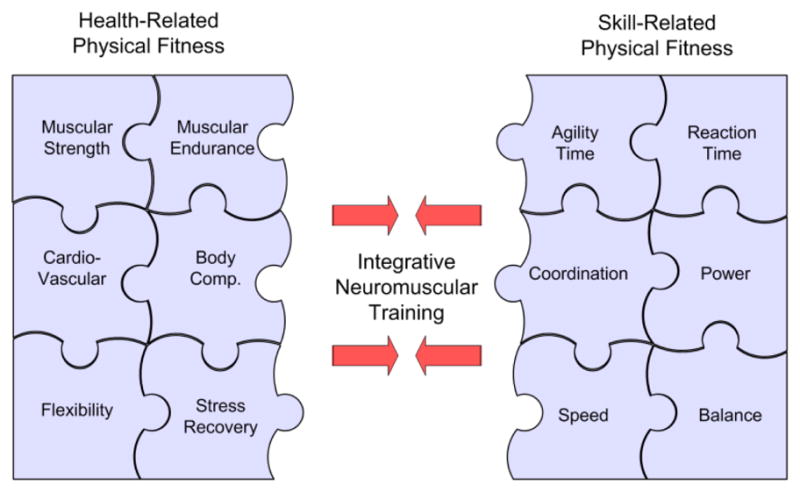

Integrative neuromuscular training is a conceptual training model that is operationally defined as a supplemental training program that incorporates general (e.g., fundamental movements) and specific (e.g., exercises targeted to motor control deficits) strength and conditioning activities, such as resistance, dynamic stability, core focused strength, plyometric and agility prescribed to enhance health and skill-related components of physical fitness (Figure 4). Integrative neuromuscular training is designed to help children master fundamental skills, improve movement mechanics, and gain confidence in their physical abilities, while participating in a program that includes variety, progression and proper recovery intervals.13, 42, 44 Integrative neuromuscular training programs utilize a variety of fundamental movements designed to enhance both health and skill-related fitness as well as to safely prepare children to be more physically active (Figure 5).10, 18, 41, 44, 45 It is likely that health benefits of exercise are evident even if improvements in body composition are not immediately evident in more athletic children.8

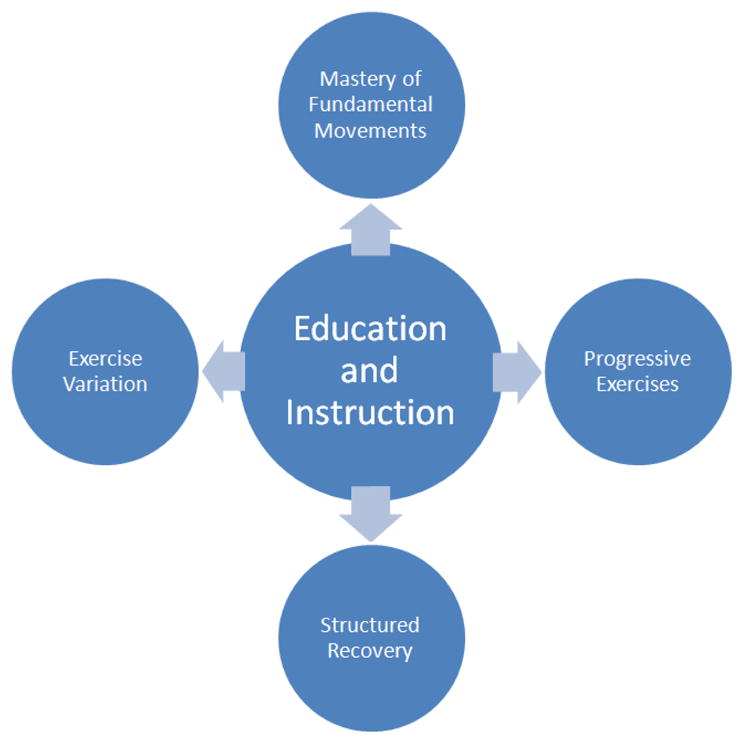

Figure 4.

Education and Instruction by pediatric exercise specialists are the key components to effective programming of integrative neuromuscular training in youth. Figure reproduced from “Myer, G. D., A. D. Faigenbaum, et al. (2011). “Integrative training for children and adolescents: techniques and practices for reducing sports-related injuries and enhancing athletic performance.” Phys Sportsmed 39(1): 74–84.” with permission from the editor.

Figure 5.

Integrative training model which indicates a focus on the development of fundamental motor skills through activities which consolidate skill and health related fitness may maximize efficacy of neuromuscular conditioning during pre-adolescence. Figure reproduced from “Myer, G. D., A. D. Faigenbaum, et al. (2011). “When to initiate integrative neuromuscular training to reduce sports-related injuries and enhance health in youth?” Current Sports Medicine Reports 10(3): 157–166.” with permission from the editor.

The cornerstone of integrative neuromuscular training is age-appropriate education and instruction by qualified pediatric exercise specialists (Figure 6). This type of training is designed to help children master fundamental skills, improve movement mechanics, and gain confidence in their physical abilities while participating in a program that includes variety, progression and proper recovery intervals.13, 43 Integrative neuromuscular training is vital for children whose cognitive and motor capabilities are highly “plastic” and amenable to age-appropriate interventions.

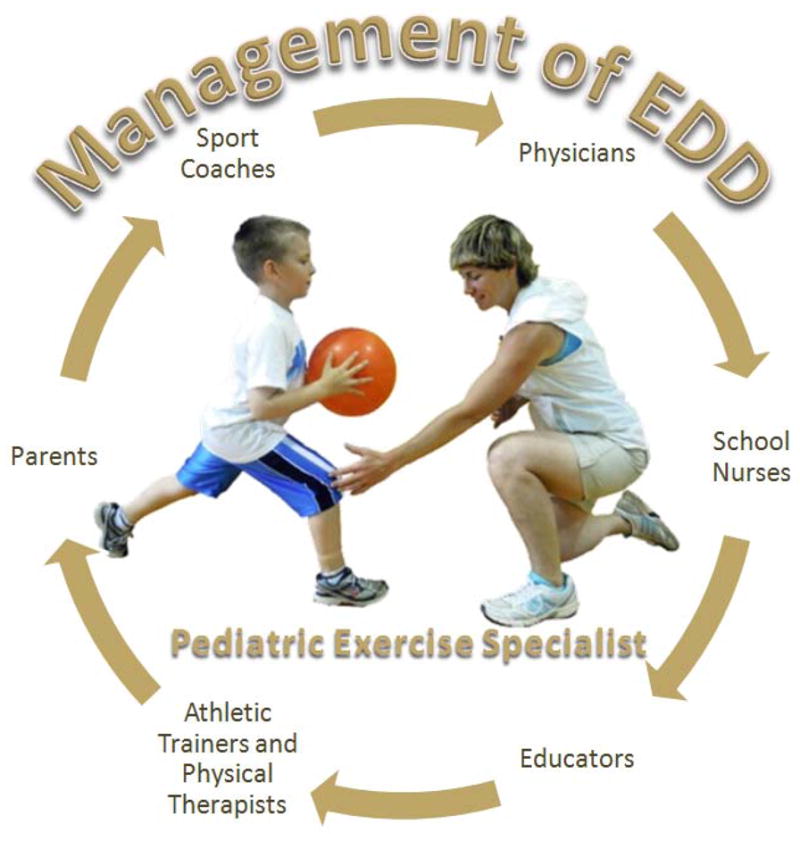

Figure 6.

Pediatric exercise specialists who are both trained and aware of the unique physical and psychosocial needs of children and who can work effectively with all other health care influences are critical to address complex demands associated with effective management of children with Exercise Deficit Disorder.

Recently, researchers evaluated an integrative neuromuscular training program that was performed 2x/week during the first 15 minutes of a 2nd grade physical education class.10 This program consisted of body weight exercises that focused on the enhancement of muscular strength, muscular power and fundamental movement skills and was found to be an effective and time-efficient addition to physical education as evidenced by improvements in health- and skill-related fitness measures in these children. High compliance and self-reported positive attitudes toward integrative neuromuscular training provided evidence of the feasibility and value of incorporation of integrative neuromuscular training into pediatric fitness programs.9 It appears therefore that the incorporation of integrative neuromuscular training programs is a cost-effective and time efficient method for enhancement of motor skills and promotion of physical activity in school-age children. Interestingly, the seven-year-old females who underwent integrative neuromuscular training in addition to their standard physical education appeared to be particularly sensitive to the positive effects of this training regimen, which may be indicative of a potential sex-specific window for optimal implementation of the proposed interventional strategies.17

SUMMARY

A management team that includes professionals who understand the fundamental principles of pediatric exercise science and appreciate the physical and psychosocial uniqueness of children and adolescents may help to identify barriers to physical activity and provide access to activity-friendly environments. However, in current child management models, physicians and pediatric exercise specialists have limited opportunity to work together in order to treat children with EDD (Figure 6). The current health care system is designed to treat disease, and does not provide opportunities for pediatric exercise specialists to collaborate with health care providers in order to enhance motor skills and promote physical activity as an ongoing lifestyle choice. Without a change in our current health care system, contemporary youth will likely remain on the current trajectory towards overweight, obesity and associated health consequences.

Management approaches that link the resources of health care professionals and qualified pediatric exercise specialists may position us to effectively circumvent the “negative spiral of inactivity”. School-age children who participate in age-related physical activity programs designed and implemented by pediatric exercise specialists may help prevent the accumulation of cardiovascular risk factors and pathological processes later in life.12, 14, 15 While limited from long term outcome studies, current evidence supports the critical importance of primary prevention as part of a comprehensive approach to treating physical inactivity in children and promoting long term health.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge funding support from National Institutes of Health/NIAMS Grants R01-AR049735, R01-AR05563 and R01-AR056259.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Barnett L, Van Beurden E, Morgan P, Brooks L, Beard J. Does childhood motor skill proficiency predict adolescent fitness? Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2008;40(12):2137–2144. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818160d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett L, Van Beurden E, Morgan P, Brooks L, Beard J. Childhood motor skill proficiency as a predictor of adolescent physical activity. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett LM, Van Beurden E, Morgan PJ, Brooks LO, Beard JR. Does childhood motor skill proficiency predict adolescent fitness? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(12):2137–2144. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818160d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnett LM, van Beurden E, Morgan PJ, Brooks LO, Beard JR. Childhood motor skill proficiency as a predictor of adolescent physical activity. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44(3):252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belcher B, Berrigan D, Dodd K, Emken A, Chou C, Spruijt-Metz D. Physical activity in US youth: Effect of race/ethnicity, age, gender, and weight status. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2010;42(12):2211–2221. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e1fba9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloemers F, Collard D, Paw MC, Van Mechelen W, Twisk J, Verhagen E. Physical inactivity is a risk factor for physical activity-related injuries in children. Br J Sports Med. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox L, Berends V, Sallis JF, et al. Engaging school governance leaders to influence physical activity policies. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8 (Suppl 1):S40–48. doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.s1.s40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etchison WC, Bloodgood EA, Minton CP, et al. Body mass index and percentage of body fat as indicators for obesity in an adolescent athletic population. Sports Health. 2011;3(3):249–252. doi: 10.1177/1941738111404655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faigenbaum AD, Farrel A, Fabiano M, et al. Effects of Integrative Neuromuscular Training on Fitness Performance in Children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2011 doi: 10.1123/pes.23.4.573. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faigenbaum AD, Farrell A, Fabiano M, et al. Effects of integrative neuromuscular training on fitness performance in children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2011;23(4):573–584. doi: 10.1123/pes.23.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faigenbaum AD, Gipson-Jones TL, Myer GD. Exercise deficit disorder in youth: an emergent health concern for school nurses. J Sch Nurs. 2012;28(4):252–255. doi: 10.1177/1059840512438227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faigenbaum AD, Gipson-Jones TL, Myer GD. Exercise Deficit Disorder in Youth: An Emergent Health Concern for School Nurses. J Sch Nurs. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1059840512438227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD. Pediatric resistance training: benefits, concerns, and program design considerations. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2010;9(3):161–168. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181de1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD. Exercise Deficit Disorder (EDD) in Youth: Play Now or Pay Later. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(4) doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31825da961. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD. Exercise Deficit Disorder in Youth: Implications for Fitness Professionals. ACSM’s Certified News. 2012 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD. Exercise deficit disorder in youth: play now or pay later. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(4):196–200. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31825da961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD, Farrel A, Radler T, Hewett TE. Sex specific Effects of Integrative Neuromuscular Training on Fitness performance in Children During Physical Education. J Athl Train. Under Review. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD, Farrell A, et al. Sex Specific Effects of integrative neuromuscular training on fitness performance in 7 year old children: An exploratory investigation. J Athl Train. 2012 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faigenbaum AD, Stracciolini A, Myer GD. Exercise Deficit Disorder in Youth: A Hidden Truth. Acta Pediatrica. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02461.x. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faigenbaum AD, Stracciolini A, Myer GD. Exercise deficit disorder in youth: a hidden truth. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(11):1423–1425. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02461.x. discussion 1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finkelstein EA, Khavjou OA, Thompson H, et al. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(6):563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2005;293(15):1861–1867. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganley K, Paterno M, Miles C, et al. Health-related fitness in children and adolescents. Pediatric Physical Therapy. 2011;23:208–220. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0b013e318227b3fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haga M. Physical fitness in children with high motor competence is different from that in children with low motor competence. Phys Ther. 2009;89(10):1089–1097. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hands B. Changes in motor skill and fitness measures among children with high an low motor competence: A five year longitudinal study. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2008;2008:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hands B, Larkin D, Parker H, Straker L, Perry M. The relationship among physical activity, motor competence and health-related fitness in 14-year-old adolescents. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19(5):655–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffman JR, Kang J, Faigenbaum AD, Ratamess NA. Recreational sports participation is associated with enhanced physical fitness in children. Res Sports Med. 2005;13(2):149–161. doi: 10.1080/15438620590956179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaques R, Loosemore M. Sports and exercise medicine in undergraduate training. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):4–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60992-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kjonniksen L, Anderssen N, Wold B. Organized youth sport as a predictor of physical activity in adulthood. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19(5):646–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambourne K, Donnelly JE. The role of physical activity in pediatric obesity. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(6):1481–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leek D, Carlson JA, Cain KL, et al. Physical Activity During Youth Sports Practices. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010 doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopes V, Rodrigues L, Maia J, Malina R. Motor coordination as predictor of physical activity in childhood. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2011;21:663–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopes VP, Rodrigues LP, Maia JA, Malina RM. Motor coordination as predictor of physical activity in childhood. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopes VP, Rodrigues LP, Maia JA, Malina RM. Motor coordination as predictor of physical activity in childhood. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(5):663–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malina RM, Bouchard C. Growth, maturation, and physical activity. Champaign, Il: Human Kinetics; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 36.May AL, Kuklina EV, Yoon PW. Prevalence of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors Among US Adolescents, 1999–2008. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):1035–1041. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merrick J, Morad M, Halperin I, Kandel I. Physical fitness and adolescence. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2005;17(1):89–91. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2005.17.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Correction: actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2005;293(3):293–294. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD. Exercise Is Sports Medicine In youth: Integrative Neuromuscular Training to Optimize Motor Development and Reduce Risk of Sports related Injury. Kronos. 2011;10(N 18):31–48. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Barber Foss KD, et al. Is a sports related injury a contemporary risk factor for reduced physical activity and onset of obesity markers in young girls? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. Under Review. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Barber Foss KD, et al. Is a sports related injury a contemporary risk factor for reduced physical activity and onset of obesity markers in young girls? J Pediatr. 2012 Under Review. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Chu DA, et al. Integrative training for children and adolescents: techniques and practices for reducing sports-related injuries and enhancing athletic performance. Phys Sportsmed. 2011;39(1):74–84. doi: 10.3810/psm.2011.02.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Chu DA, et al. Integrative Training for Children and Adolescents: Techniques and Practices for Reducing Sports-related Injuries and Enhancing Athletic Performance. Physician and Sports Medicine. 2011;39(1) doi: 10.3810/psm.2011.02.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Ford KR, Best TM, Bergeron MF, Hewett TE. When to initiate integrative neuromuscular training to reduce sports-related injuries and enhance health in youth? Curr Sports Med Rep. 2011;10(3):157–166. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31821b1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Myer GD, Sugimoto D, Thomas S, Hewett TE. The Influence of Age on the Effectiveness of Neuromuscular Training to Reduce Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury in Female Athletes: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2012 doi: 10.1177/0363546512460637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myer GD, Xu Y, Khoury J, Hewett TE. Effects of Knee Injury on Body Composition Change During Maturation in Athletic Females. Presented at the Ohio State Research Day; 2011; Columbus, Ohio. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nader P, Bradley R, Houts R, McRitchie S, O’Brien M. Moderate to vigorous physical activity from ages 9 to 15 years. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300:295–305. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Association for SportsPhysical Education & American Heart Association. 2012 Shape of the Nation Report: Status of Physical Education in the USA. American Alliance for Health, Physical Education Recreation and Dance. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogden CL, Carroll ME, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;(82):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Phillips JA, Young DR. Past-year sports participation, current physical activity, and fitness in urban adolescent girls. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(1):105–111. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reinehr T. Effectiveness of lifestyle intervention in overweight children. Proc Nutr Soc. 2011;70(4):494–505. doi: 10.1017/S0029665111000577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rowland T. Promoting physical activity for children’s health. Sports Med. 2007;37:929–936. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737110-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruiz J, Castro-Pinero J, Artero E, et al. Predictive validity of health related fitness in youth: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:909–923. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.056499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rye JA, O’Hara Tompkins N, Eck R, Neal WA. Promoting youth physical activity and healthy weight through schools. W V Med J. 2008;104(2):12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sacheck JM, Nelson T, Ficker L, Kafka T, Kuder J, Economos CD. Physical activity during soccer and its contribution to physical activity recommendations in normal weight and overweight children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2011;23(2):281–292. doi: 10.1123/pes.23.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schreiber J, Goodgold S, Moerchen V, Remec N, Aaron C, Kreger A. A description of professional pediatric physical therapy education. Pediatric Physical Therapy. 2011;23(2):201–204. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0b013e318218f2fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sirard JR, Pfeiffer KA, Dowda M, Pate RR. Race differences in activity, fitness, and BMI in female eighth graders categorized by sports participation status. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2008;20(2):198–210. doi: 10.1123/pes.20.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stodden D, Langendorfer S, Roberton M. The association between motor skill competence and physical fitness in young adults. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2009;80(2):223–229. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2009.10599556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stodden DJ, Goodway S, Langendorfer S, Robertson M, Rudisill M, Garcia C. A developmental perspective on the role of motor skill competence in physical activity: An emergent relationship. Quest. 2008;60:290–306. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Story M, Kaphingst KM, French S. The role of schools in obesity prevention. Future Child. 2006;16(1):109–142. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stracciolini A, Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD. Exercise Deficit Disorder in Children: Are we ready to make the diagnosis? Phys Sportsmed. doi: 10.3810/psm.2013.02.2003. Under Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Strong WB, Malina RM, Blimkie CJ, et al. Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. J Pediatr. 2005;146(6):732–737. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sugimoto D, Myer GD, Bush HM, Klugman MF, Mckeon JM, Hewett TE. Effect of Compliance with Neuromuscular Training on ACL Injury Risk Reduction in Female Athletes: A Meta-Analysis. J Athl Train. 2012 doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.6.10. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Teixeira FV, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Maia AR. Beliefs and practices of healthcare providers regarding obesity: a systematic review. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2012;58(2):254–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Telama R. Tracking of physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a review. Obes Facts. 2009;2(3):187–195. doi: 10.1159/000222244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Telford A, Finch CF, Barnett L, Abbott G, Salmon J. Do parents’ and children’s concerns about sports safety and injury risk relate to how much physical activity children do? Br J Sports Med. 2012 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Trasande L, Liu Y, Fryer G, Weitzman M. Effects of childhood obesity on hospital care and costs, 1999–2005. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(4):w751–760. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tucker JM, Welk GJ, Beyler NK. Physical activity in U.S.: adults compliance with the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(4):454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tudor-Locke C, Johnson W, Katzmarzyk PT. Accelerometer-determined steps per day in US children and adolescents. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2010;42(12):2244–2250. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e32d7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2008 www.health.gov/paguidelines.

- 71.Weintraub DL, Tirumalai EC, Haydel KF, Fujimoto M, Fulton JE, Robinson TN. Team sports for overweight children: the Stanford Sports to Prevent Obesity Randomized Trial (SPORT) Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(3):232–237. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Geneva: WHO Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zahner L, Muehlbauer T, Schmid M, Meyer U, Puder JJ, Kriemler S. Association of sports club participation with fitness and fatness in children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(2):344–350. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318186d843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]