Abstract

Objectives:

To describe the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of an outbreak of occupational silicosis and the associated working conditions.

Methods:

Cases were defined as men working in the stone cutting, shaping, and finishing industry in the province of Cádiz, diagnosed with silicosis between July 2009 and May 2012, and were identified and diagnosed by the department of pulmonology of the University Hospital of Puerto Real (Cádiz). A census of workplaces using quartz conglomerates was carried out to determine total numbers of potentially exposed workers. A patient telephone survey on occupational exposures and a review of medical records for all participants were conducted.

Results:

Silicosis was diagnosed in 46 men with a median age of 33 years and a median of 11 years working in the manufacturing of countertops. Of these cases, 91.3% were diagnosed with simple chronic silicosis, with an abnormal high-resolution computerized tomography (HRCT) scan. One patient died during the study period. Employer non-compliance in prevention and control measures was frequently reported, as were environmental and individual protection failures.

Conclusions:

The use of new construction materials such as quartz conglomerates has increased silicosis incidence due to intensive occupational exposures, in the context of high demand fuelled by the housing boom. This widespread exposure poses a risk if appropriate preventive measures are not undertaken.

Keywords: Silicosis, Quartz conglomerates, Respirable crystalline silica, Marble works, Occupational disease

Introduction

Silicosis is a pulmonary disease resulting from the inhalation and accumulation of inorganic silica dust in the lung.1,2 The risk of disease is related to lifetime cumulative exposure and to the amount of inhaled crystalline silica, which, in turn, depends on the concentration and the size of respirable particles (<5 μm), and on individual susceptibility.3,4 Prevention of this disease is based on respirable dust control, and no curative treatment currently exists.5 Chronic silicosis is the most common clinical presentation classically appearing in miners after exposure to low concentrations over a long period of time (>15–20 years).3 To establish the diagnosis, it is useful to match labour history of exposure to crystalline silica dust over time with compatible clinical, functional, and radiological signs.2

The most frequent crystalline forms of silica in workplaces are quartz, tridymite, and cristobalite.6 In recent years, clusters of cases have been reported in relation to new occupational exposures in several countries.7–9 Some of them are related to mechanization procedures (cutting, calibration, and polishing) used in the manufacturing and installation of kitchen countertops made of quartz conglomerates, materials with a high content of crystalline free silica (70–90%). These workers are exposed to high concentrations of silica, resulting in disease after relatively short latency periods.9

More than three million European workers were exposed to crystalline silica at the beginning of the 1990s.10 Despite the decline in silicosis incidence observed in developed countries in the following decades, mainly due to the improvement of prevention measures such as protective equipment,8 additional efforts to reduce dust exposure by strict compliance with existing regulatory standards are still considered necessary.11

In Spain, silicosis incidence appears to be increasing. Cases reported to the Spanish Institute of Silicosis decreased gradually from 2003 (375 cases) to 2007 (115 cases), but increased annually thereafter to 256 cases in 2011.12 Another official source, the Observatory of Occupational Diseases, reported an increase from 95 to 295 cases in the same period. Many cases may be reported to both institutes. The latter was established in 2007 as an exhaustive register of occupational disease cases, while the former, with several decades of history, specifically monitors silicosis on a volunteer-based reporting procedure.13 Although the Spanish Institute of Silicosis recognizes significant underreporting, a relevant qualitative change in the trend of associated occupational exposures was detected: in 2011, for the first time, the number of cases among coal mining workers was lower than the rest of professions, mainly ornamental stone workers.12 According to the Observatory, workers in the manufacturing industry accounted for 78% of cases.13

After the emergence in 2009 of several cases of silicosis related to the manufacture of kitchen countertops in southern Spain,14 an unexpectedly high number of cases was observed in the area. This article describes the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of ill workers, and the occupational conditions and preventive measures undertaken.

Methods

Identification of cases

In late 2009, three suspected cases of occupational silicosis detected at the University Hospital of Puerto Real (Cádiz) were reported to the Andalusian Epidemiological Surveillance System. All were marble workers working in the manufacture and home assembly of kitchen countertops, in companies based in the town of Chiclana de la Frontera (pop. 75.000). Owing to the unexpectedly high number of cases, an outbreak investigation was initiated. A case was defined as “man who has worked or works in the stone cutting, shaping and finishing industry (group 23.7 NACE Rev 2)15 in the province of Cádiz, diagnosed with silicosis by HRCT, between July 2009 and May 2012.”

As early cases were diagnosed at the hospital, newly affected workers sought transfers to the hospital pneumology unit instead of seeking attention elswehere. In addition, hospital epidemiologists performed active surveillance among symptomatic peers of sick workers who had been attended elsewhere until then. Finally, eight asymptomatic cases were diagnosed at the hospital after demanding medical check-ups on their own initiative.

Chest radiography failed to detect some initial cases with moderate silicosis that were diagnosed shortly afterwards by high-resolution computerized tomography (HRCT). Due to lack of expertise with ILO technique, as silicosis was a very uncommon disease so far in the region, HCRT was chosen as the gold standard test. Surgical lung biopsy obtained by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery was performed in the first four patients in order to rule out interstitial lung disease. As further cases arose with similar symptoms and occupational history, HRCT was considered sufficient to reach a definitive diagnosis.

Census

In order to approach a measurement of prevalence, a census was carried out of exposed workers in all ornamental stone industries located in the four municipalities where cases were detected. The number of workers employed and exposed was estimated in three different periods, which could show the trend and the maximum number of exposed workers. The years 2000, 2004, and 2008 were chosen.

Survey of cases

A survey was designed according to the Spanish Health Surveillance Protocol “Silicosis and other pneumoconiosis,”16 which contained the following variables: patient’s personal data, last company in which they worked, occupational history, medical examinations, availability and use of personal protective equipment, materials handled, machinery and tools employed, and environmental protection systems in the workplace. They were also asked whether they knew other workers who had the same symptoms or they suspected of being sick. This information was collected through telephone interviews with those affected.

Subsequently, the medical records of all patients were reviewed to collect the following data: personal history, previous respiratory diseases, respiratory symptoms, spirometry testing, and diagnosis.

Results are presented as percentages for categorical variables, and median and interquartile range for continuous variables.

Results

In less than 3 years (2009–2012), 47 quartz conglomerate workers were diagnosed with silicosis. A total of 46 were included in the present study, after excluding one for working outside the province. Median age at diagnosis was 33 years (interquartile range: 29–37 years) and 26% of the workers were under age 30 at diagnosis. Median length of employment was 11 (mean: 12.8) years (interquartile range: 9–17 years).

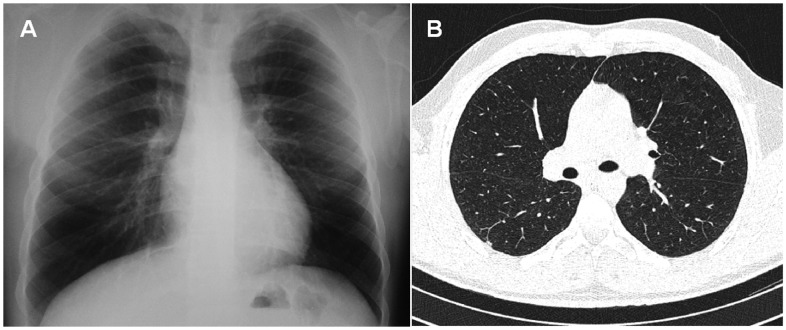

The chest radiograph revealed a bilateral diffuse micronodular pattern in 80.4% (37) of the cases, the remaining 19.6% being normal. All the cases included in the study were confirmed by HRCT. The diagnosis was simple chronic silicosis in 91.3% of cases and complicated chronic silicosis in the remaining 8.7%. Micronodules were present in most cases predominating in upper lung zones. Diffuse ground-glass pattern was visible in three workers (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Images belonging to a patient with simple silicosis showing: a normal chest radiograph (A) and widespread and small silicotic nodules in high-resolution CT scan 1 month later (B).

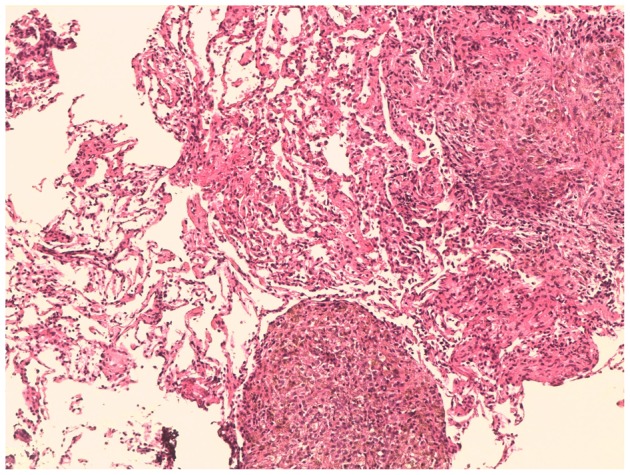

A lung biopsy — four initial surgical biopsies plus eight additional transbronchial biopsies — was performed in 12 cases (26.1%), and was confirmatory in eight of them. Main histopathological findings in parenchyma were inflammatory nodules with histiocytes and fibroblasts, located in alveolar septa and perivascular interstice, with limited collagenization, probably in relation to initial stages of the silicotic disease (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Histological section of lung parenchyma. Inflammatory nodules with lymphocytes and histiocytes, and perivascular fibrous thickening of alveolar septa.

Pulmonary function tests in simple silicosis cases (n = 42) revealed a very moderately restrictive pattern (FVC% = 85.4±12, FEV1% = 85.9±13, FEV1/FVC = 79.9±5), meanwhile, the four complicated silicosis cases showed a more restrictive spirometric profile (FVC% = 77.74±18, FEV1% = 74.5±14, FEV1/FVC = 76.6±9) and decreased carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO = 58.4±12).

Respiratory disease other than silicosis was not present in 67.4% of the cases studied. Among the 32.6% with a history of these diseases, allergic rhinitis was the most common diagnosis, in 15.2% (seven cases), followed by bronchial asthma (8.7%), and chronic bronchitis in 6.5% (three cases).

Regarding medical history, 82.6% (38) of sick workers practiced sports regularly before silicosis diagnosis, 39.1% had never smoked (18), 43.5% were ex-smokers (20, >6 months without smoking), and 17.4% were smokers at the time of the interview. Mild respiratory symptoms were present in 82.6% (38), but all reported feeling more tired than usual before diagnosis; the remaining eight cases (17.4%) were asymptomatic.

Census

The number of exposed workers was 82 in 2000, increasing to 192 in 2004 and to 224 in 2008, period with higher employment rate, declining thereafter with the onset of the economic crisis in Spain. Given the low turnover of employees, prevalence rates among exposed workers could be close to 20%, or even greater, as the occurrence of new cases is expected considering the latency period of the disease.

Survey

All cases had used agglomerated quartz in the manufacturing of countertops, mainly for kitchens, both in the workshop and during installation in households, and all of them were active employees at the time of diagnosis. Considering the last company in which the patients had worked or were working, there were a total of 12 small family industries where workers or owner were diagnosed. In some cases, there were several members of the same family diagnosed. All the businesses were located in the province of Cádiz. Nine of them were situated in Chiclana de la Frontera and accumulated 41 cases (one business with 16 cases, accounted for 34.8%), while the other three were located in Jerez de la Frontera, Medina-Sidonia, and Sanlúcar de Barrameda, accounting for the other five patients. The cases had worked in an average of two companies during their working lives.

Regarding protective measures applied in the workshop, respondents reported that water curtains, which prevent the generation of silica dust in the countertop cutting machinery, were present in only 32.6% of respondents’ workplace (15 cases). Only in 6.5% of workshops (three cases), machinery and tools were checked periodically, while 26.1% (12 cases) were revised eventually or in case of failure. Regarding ventilation, 10.9% (five cases) reported that the dust ventilation system worked properly, while 54.3% of the cases reported that it was ineffective, and the remaining 34.8% mentioned doors and windows, or working in an outdoor courtyard, as the only form of ventilation. Periodical measurements of dust levels were never performed in any workplace according to workers responses. All of the workers reported the absence of any ventilation systems when installing countertops in the households. Only 32.6% of the cases reported having used complete personal protective equipment consisting of a mask, goggles, helmet, gloves, special footwear and overalls; however, in most cases, this equipment was inadequate, since only three cases (6.5%) reported having constant access to FFP3 or P5 masks, while 50% (23 cases) of workers had access only part of the time. Most employees reported having worked more than 10 hours a day during many periods.

Our review of patients’ medical records showed some inadequacies in periodic preventive medical examinations: 32.6% (15 cases) never underwent a chest X-ray, 58.7% underwent one for the first time in 2009; in only 8.7% of cases, this procedure was performed at each periodic review.

Before the completion of this study, one affected 33-year-old worker had died due to silicosis during the process of lung transplantation, and another case experienced significant complications. The patient who died was diagnosed with complicated silicosis. He presented repeated pneumothorax and severe respiratory failure with no cardiac disorders. He underwent surgery 2 months after the transplant indication and died 24 hours after transplantation. The cause of death was graft dysfunction and multiple organ failure.

Discussion

A high incidence of silicosis was detected in a short period of time and primarily confined to a small geographical area, Chiclana de la Frontera, a town in the province of Cádiz, with cases occurring in young workers specialized in the manufacture and installation of kitchen countertops with quartz conglomerates, with a lack of protective measures and compulsory preventive actions evidenced.

This cluster of silicosis is associated with a relatively new material, quartz agglomerate, also known as engineered stone, characterized by its high content of free crystalline silica (70–90% depending on the color and type of finishing, compared with 30% in granite and 5% in marble).6 Quartz agglomerate has been used as an alternative to traditional natural stone (granite and marble) since the 1990s. Its wide variety of colors and surface finishes prompted its use in interior decoration (kitchen countertops, bathrooms, floors, and wall covering).16

A number of publications in recent years describe silicosis cases related to the same occupational exposure. Two of these studies present cases in Spain: three in Asturias9 and six in Vizcaya,17 in small companies engaged in the mechanization of agglomerates to manufacture quartz countertops in kitchens and bathrooms. The largest series to date corresponds to a recent study conducted in Israel18 that reported a cluster of 25 cases of silicosis in workers detected after admission into the National Lung Transplantation Program who used the Caesarstone brand agglomerate. This research limited its scope to cases included in the Program, all of them severe cases, not conducting any additional research among patients on the lung transplantation waiting list.

The number of cases in our study represents a significant cluster in a relatively short time span, less than 3 years. The Spanish National Institute of Silicosis only registered in its reports a number of cases related to ornamental stonework: 1 in 2009, 9 in 2010, and 14 cases in 2011, while acknowledging the underreporting of this disease and the burden of current and future cases in quartz conglomerates workers.12

Traditionally, chest radiography diagnosis according to the ILO classification is one of the first criteria for the diagnosis of silicosis-related lesions. However, its usefulness in clinical diagnosis is controversial in relation to two features: the high inter-rater variability and the underestimation of the presence of pulmonary disease.19 HRCT provides crucial visual information beyond chest radiography, mainly in the early stages of silicosis. In our initial series of cases, HRCT scans proved to be more sensitive than chest radiography in detecting lung parenchymal changes suggestive of pneumoconiosis such as nodular changes, and so it was used for the diagnosis of silicosis in this context.20

The length of employment of workers in our series was lower than the 18.5 years in Kramer et al.18 and the 17 years in Martinez et al.17 This shorter time may be related to a higher intensity of exposure. There is a well-known association between the nature and extent of the biological response to the intensity of exposure and there is evidence that newly fractured silica is more toxic than the “aged powder” containing silica.1 This was dramatically revealed in the silicosis epidemic in the Turkish textile industry, where very severe cases appeared after particularly intense and short exposures to recently fractured silica in young denim sandblasting workers subject to long working hours without adequate protective measures.7,21

One of the reasons for this time-space clustering of cases is the concentration in the town of Chiclana of small marble factories specialized in the production of kitchen countertops, coinciding with the housing boom experienced in the region and in most of the country from the late 1990s to the beginning of the economic crisis in 2008.22 In just a few years, Chiclana went from being an agricultural village to a small industrial hub, specialized, among other industries, in the elaboration of agglomerates for countertops.23 This high demand, sustained for some years, has likely led to intense exposure of workers, especially where employers disregarded regulations regarding both individual and environmental protection measures, as well as preventive and control activities.

Regarding environmental protection, basic requirements for the protection of workers in relation to cleanliness and hygiene were not met, with no water curtains or extractors working correctly to remove dust generated from the environment in a high percentage of factories. In addition, machinery and tools were not properly equipped, and did not undergo prescribed routine checks. Failure to comply with personal protective measures is very striking; the majority of workers reported not having full protective equipment, nor using them properly, without access to a FFP3 or P5 mask, mandatory for dry cutting quartz agglomerates. In relation to early detection,24 standard chest radiographies as required in annual health examinations16 were not performed.

After the emergence of the first cases, the Centre for Risk Prevention of the Regional Labour Authority and the Inspectorate of the Ministry of Labour in Cádiz conducted inspections and made determinations of exposure to silica dust in some companies, as this information was historically lacking in the companies’ prevention service activity reports. Results from only two of them were available for researchers. In one business, the level of free silica exceeded acceptable limits in three posts related to cutting and polishing material, while respirable dust levels were normal. In the second one, the level of respirable dust was elevated in one workplace.25,26 Similarly, a study carried out in the Basque Country on 14 companies in 2010,27 in the wake of the initial appearance of a cluster of cases of silicosis in artificial stone workers,17 detected high levels of exposure to free silica in 20% of workplaces evaluated, mainly in polishing tasks with quartz agglomerates, and acceptable levels of respirable dust. Despite the limited information on the concentration and nature of the dust in our setting, the high incidence of cases, together with the insufficient preventive measures and long working hours, make it plausible to assume that workers were exposed to dangerous amounts of respirable dust and free silica in the period of elevated industrial activity studied.

Kramer et al.18 described similar working conditions to those of workplaces in our study, with dry cutting of countertop materials, a lack of personal protective equipment, and an absence of the measurement of dust levels in the workplace. The two other Spanish studies did not find a lack of preventive measures in the workshops, but rather during assembling of the tops in the households.9,17 In a recent study in the USA on the use of dry-cut methods to manufacture granite countertops, though not agglomerates, 74% of companies used dry cutting at some stage of manufacture.28

According to Spanish law, any new device must be accompanied by a data sheet provided by the manufacturer, reporting potential health hazards and explaining recommended management, including preventive measures. For the main manufacturer of quartz agglomerate in our study, this information was generic in 2005 and more specific only since 2009,29 so the business owners could not incorporate appropriate preventive measures and processes specific to work with these products during the years before the publication of the updated data sheets.

The main limitation of the study is that information on exposure and prevention practices is based largely on the statements of the patients and employers; thus, recall bias of respondents cannot be ruled out completely, although inspections of the workplaces carried out by the Centre for Risk Prevention of the Regional Labour Authority and the Inspectorate of the Ministry of Labour in Cádiz corroborate the main results we obtained through interviews. The availability of exposure data was circumscribed to a couple of businesses, and the calculation of hours worked by those affected was not possible, due to lack of accurate registers. Assessing healthy workers’ exposures could have provided information to analyze the magnitude of the influence of some variables, but the study design did not allow it.

Although Spanish national law classifies silicosis as an occupational disease30 and all patients were correctly diagnosed, at the end of the study period, half of these cases had not been recognized as occupational diseases. These affected workers have not yet received benefits they are legally entitled which are being drawn out bureaucratically. Moreover, pensions after permanent partial disability is determined are low, but in most cases, workers will not look for another job to supplement their income as the health insurance companies would denounce them, jeopardizing their pensions. Low pensions also may discourage those still working in marble industry from being screened and diagnosed as having silicosis to avoid being forced to leave current occupations.

Current national legislation clearly states the need for correct handling of quartz conglomerates.24 The apparent failure of all stakeholders (manufacturers, occupational risk prevention services, benefit societies/mutual insurance companies for occupational accidents and diseases, and business owners), both in the implementation of protective measures in the workplace and in health surveillance, has led to a serious situation, whose full extent can not yet be accurately foreseen.

Conclusion

In the context of high demand fuelled by the housing boom, the use of quartz conglomerates, containing silica in high concentrations, has increased silicosis incidence in Cádiz. This occupational exposure poses a serious risk if appropriate preventive measures are not undertaken.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Antonio Escolar Pujolar (Delegación Provincial de Salud de Cádiz) and Gabriel Rodriguez (Hospital Puerta del Mar, Cádiz) for their critical revision of the text. Moreover, we thank Andy Lawson for English language corrections.

Disclosure: The authors declare no competing interests for publication. This research received no specific funding.

References

- 1.Leung CC, Yu IT, Chen W. Silicosis. Lancet. 2012;379:2008–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Instituto Nacional de Seguridad e Higiene en el Trabajo. Aglomerados de cuarzo: medidas preventivas en operaciones de mecanizado. Notas técnicas de prevención 890 [document on the Internet]. Madrid: INSHT; 2010 [cited 2012 Oct 11]. Available from: http://www.insht.es/InshtWeb/Contenidos/Documentacion/FichasTecnicas/NTP/Ficheros/821a921/890w.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Health effects of occupational exposure to respirable crystalline silica. Cincinnati, OH: Department of Health and Human Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedlund U, Jonsson H, Eriksson K, Järvholm B. Exposure–response of silicosis mortality in Swedish iron ore miners. Ann Occup Hyg. 2008;52:3–7. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/mem057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg MI, Waksman J, Curtis J. Silicosis: a review. Dis Mon. 2007;53:394–416. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mossman BT, Churo A. Mechanism in the pathogenesis of asbestosis and silicosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1666–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9707141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akgun M, Mirici A, Ucar EY, Kantarci M, Araz O, Gorguner M. Silicosis in Turkish denim sandblasters. Occup Med (Lond). 2006;56:554–8. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kql094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madl AK, Donovan EP, Gaffney SH, McKinley MA, Moody EC, Henshaw JL, et al. State-of-the-science review of the occupational health hazards of crystalline silica in abrasive blasting operations and related requirements for respiratory protection. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2008;1:548–608. doi: 10.1080/10937400801909135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pascual S, Urrutia I, Ballaz A, Arrizubieta I, Altube L, Salinas C. Prevalencia de silicosis en una marmolería tras la exposición a conglomerados de cuarzo. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:50–1. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kauppinen T, Toikkanen J, Pedersen D, Young R, Ahrens W, Boffetta P, et al. Occupational exposure to carcinogens in the European Union. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57:10–8. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrod AN, Evans PG, Davy CW. Risk management measures for chemicals: the “COSHH essentials” approach. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2007;17:S48. doi: 10.1038/sj.jes.7500585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Instituto Nacional de Silicosis. Nuevos casos de Silicosis registrados en el INS durante el año 2011 [document on the Internet]. Oviedo: INSS; 2012 [cited 2012 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.ins.es/documents/10307/10507/fichero12_1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Observatorio de enfermedades profesionales [document on the Internet] Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social [cited 2012 Nov 4]. Available from: http://www.seg-social.es/Internet_1/Estadistica/Est/Observatorio_de_las_Enfermedades_Profesionales/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 14.García Vadillo C, Gómez JS, Morillo JR. Silicosis in quartz conglomerate workers. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:53. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Regulation (ECc) No. 1893/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 establishing the statistical classification of economic activities NACE Revision 2 and amending Council Regulation (EEC) No 3037/90 as well as certain EC Regulations on specific statistical domains. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuervo VJ, Eguidazu JL, González A, Guzmán A, Hevia JR, Isidro I, et al. Silicosis y otras Neumoconiosis. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; 2001. Protocolos de Vigilancia Sanitaria Específica del Consejo Interterritorial del Sistema Nacional de Salud. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínez C, Prieto A, García L, Quero A, González S, Casan P. Silicosis: a disease with an active present. Arch Bronconeumol. 2010;46:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer MR, Blanc PD, Fireman E, Amital A, Guber A, Rhahman NA, et al. Artificial stone silicosis: disease resurgence among artificial stone workers. Chest. 2012;142:419–24. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopes AJ, Mogami R, Capone D, Tessarollo B, de Melo PL, Jansen JM. High-resolution computed tomography in silicosis: correlation with chest radiography and pulmonary function tests. J Bras Pneumol. 2008;34:264–72. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132008000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun J, Weng D, Jin C, Yan B, Xu G, Jin B, et al. The value of high resolution computed tomography in the diagnostics of small opacities and complications of silicosis in mine machinery manufacturing workers, compared to radiography. J Occup Health. 2008;50:400–5. doi: 10.1539/joh.l8015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akgun M, Araz O, Akkurt I, Eroglu A, Alper F, Saglam L, et al. An epidemic of silicosis among former denim sandblasters. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1295–303. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00093507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKee M, Karanikolos M, Belcher P, Stuckler D. Austerity: a failed experiment on the people of Europe. Clin Med. 2012;12:346–50. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-4-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Román A, Pérez M, Muñoz de Arenillas A. Chiclana de la Frontera (Cádiz), un modelo de urbanización-modernización en el que todo vale. In: Nicolás E, González C, editors. Ayeres en discusión: temas claves de historia contemporánea hoy. Proceedings of the IX Congreso de la Asociación de Historia Contemporánea; 2008 Sep 17–19; Murcia, España. Murcia: Universidad de Murcia; 2008. p. 347–69. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Orden ITC/2585/2007, de 30 de agosto, por la que se aprueba la Instrucción Técnica Complementaria 2.0.02 ‘Protección de los trabajadores contra el polvo, en relación con la silicosis, en las industrias extractivas’, del Reglamento General de Normas Básicas de Seguridad Minera. Boletín Oficial del Estado No. 215, de 7 de Septiembre de 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hinojo A. Evaluación higiénica de exposición a polvo ITC 2.0.02 de seguridad minera. Jerez de la Frontera (España): Sociedad de Prevención de ASEPEYO, S.L.U.; 2010. Report No.: 1151/KI02095048/EH. Contract No.: 1151-215357-10-001-238. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodríguez JS. Informe sobre exposición a contaminantes químicos. Cádiz (España): Sociedad de Prevención de Ibermutuamur, S.L.U.; 2009. Report No.: 001/058-0/10311. Contract No.: 62502/378324. [Google Scholar]

- 27.de las Peñas MN. Exposición a sílice en el trabajo con aglomerados de cuarzo en el País Vasco. ROC Máquina [document on the Internet]. 2012 [cited 2013 Jan 13];130:28–31. Available from: http://www.osalan.euskadi.net/contenidos/noticia/info2012_silicenieves/es_noticia/adjuntos/art_npena_silice_CAE_expo.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips ML, Johnson AC. Prevalence of dry methods in granite countertop fabrication in Oklahoma. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2012;9:437–42. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2012.684549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Orden de Servicio No. 48/0001990/10. Informe de Enfermedad Profesional. Ministerio de Trabajo e Inmigración. Inspección Provincial de la Tesorería y Seguridad Social de Vizcaya. 10 de Marzo de 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Real Decreto 1299/2006, de 10 de noviembre, por el que se aprueba el cuadro de enfermedades profesionales en el sistema de la Seguridad Social y se establecen criterios para su notificación y registro. Boletín Oficial del Estado No. 302, de 19 de Diciembre de 2006. [Google Scholar]