Abstract

Calculated globulin (total protein – albumin) is usually tested as part of a liver function test profile in both primary and secondary care and determines the serum globulin concentration, of which immunoglobulins are a major component. The main use hitherto of calculated globulin is to detect paraproteins when the level is high. This study investigated the potential to use low levels of calculated globulin to detect antibody deficiency. Serum samples with calculated globulin cut-off < 18 g/l based on results of a pilot study were collected from nine hospitals in Wales over a 12-month period. Anonymized request information was obtained and the samples tested for immunoglobulin levels, serum electrophoresis and, if appropriate, immunofixation. A method comparison for albumin measurement using bromocresol green and bromocresol purple was undertaken. Eighty-nine per cent (737 of 826) samples had an immunoglobulin (Ig)G level of < 6 g/l using the bromocresol green methodology with a cut-off of < 18 g/l, and 56% (459) had an IgG of < 4 g/l. Patients with both secondary and primary antibody deficiency were discovered and serum electrophoresis and immunofixation showed that 1·2% (10) had previously undetected small paraproteins associated with immune-paresis. Using bromocresol purple, 74% of samples had an IgG of < 6 g/l using a cut-off of < 23 g/l. Screening using calculated globulin with defined cut-off values detects both primary and secondary antibody deficiency and new paraproteins associated with immune-paresis. It is cheap, widely available and under-utilized. Antibody-deficient patients have been discovered using information from calculated globulin values, shortening diagnostic delay and time to treatment with immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Keywords: common variable immunodeficiency, immunoglobulin, myeloma, primary antibody deficiency, screening, secondary antibody deficiency

Introduction

Antibody deficiency may be either primary or secondary, and the most common severe primary antibody deficiency (PAD) is common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), which accounts for the majority (57%) of all symptomatic primary immunodeficiency (PID) cases on the European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) registry (http://www.esid.org). Secondary antibody deficiency occurs even more frequently than PAD.

CVID is an important diagnosis not only because of its prevalence (one in 25 000–50 000) [1], but also because of the frequent requirement for medical attention and intervention. The morbidity and need for health resources is exacerbated by a diagnostic delay of, on average, between 6 and 7 years before appropriate treatment is started [2]. In contrast to many other PID diseases, patients with CVID may be diagnosed at almost any age [2], which has implications for screening approaches.

The misconception that PID always presents in infancy in combination with the protean manifestations of CVID, the number of specialities to which patients may present and the wide range of non-infectious complications all contribute to the delay in recognition of the underlying diagnosis. This may result in recurrent infections leading to irreversible end organ damage, such as bronchiectasis.

Clinical strategies to reduce diagnostic delay include improved education and awareness of antibody deficiency in both primary and secondary care, patient-centred screening [3], the use of the ‘10 warning signs’ of PID (http://www.info4pi.org) and using computer sorting of diagnostic codes [4]. A study into the clinical features which identify children with immunodeficiency found that of the 10 warning signs the strongest predictors were family history, intravenous antibiotics for sepsis (neutrophil defects) and failure to thrive (T cell defects), while for B cell defects the only predictor was family history of immune deficiency [5].

Laboratory approaches have involved opportunistic detection cases of antibody deficiency by cascade testing for immunoglobulins when there is a very low background in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) used for coeliac disease testing, such as the immunoglobulin (Ig)A anti-tissue transglutaminase (TTG) assay [6], and also when there is a very low IgE < 2 IU/ml [7]. These opportunistic methods lack specificity and depend upon the clinical details on the request form, which are often incomplete or lacking. Furthermore, the very successful newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) looking for T cell receptor excision circles (TRECs) in DNA extracted from Guthrie spots [8], when extended to B cell kappa-deleting recombination excision circles (KRECs) [9], will not detect CVID due to the adult onset and presence of B cells in the majority of patients. Guthrie spots are also unsuitable for the detection of IgA deficiency in neonates, as the IgA at that age is of both fetal and maternal origin [10]. There still remains a major challenge in the early detection of B cell immunodeficiency and thus antibody deficiency.

Calculated globulin (CG) is derived from the difference between total protein and albumin results, and forms part of the liver function test (LFT) profile. CG is used widely in primary and secondary care to detect high levels that may indicate haematological malignancy, such as multiple myeloma. The globulin fraction consists of alpha 1, alpha 2, beta 1, beta 2 and gamma globulin fractions, and as proteins within the alpha and beta fractions can act as acute-phase proteins; high levels of these could potentially mask a low gamma globulin (antibody) level. CG levels have been shown to be low in patients with antibody deficiency [11], and as they reflect antibody levels there is an opportunity to aid clinicians in the diagnosis of a range of conditions with both high and low levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

Causes of a high or low calculated globulin

| High calculated globulin levels | Low calculated globulin levels |

|---|---|

| Plasma cell dyscrasias and lymphoproliferative disease, e.g. myeloma, Waldenstrom's macroglobulinaemia | Primary antibody deficiency, e.g. CVID |

| Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) | Small paraproteins with immune-paresis |

| Viral infections, e.g. HIV, EBV, HBV | Secondary antibody deficiency, e.g. lymphoma, chemotherapy, rituximab, protein losing enteropathy, plasma exchange, renal losses (e.g. nephrotic syndrome) and immunosuppressive drugs |

| Sarcoidosis | Fluid therapy/shifts, e.g. peri-operatively or in acutely unwell patients such as ITU or medical therapy involving fluid resuscitation |

| Connective tissue disease, e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögrens syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis | |

| Autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary sclerosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis | |

| Chronic infection, e.g. TB, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, hepatitis |

EBV = Epstein–Barr virus; HBC = hepatitis B core antigen; CVID = common variable immunodeficiency; TB = tuberculosis; ITU = intensive care unit.

In preparation for this study, a survey of practice in biochemistry laboratories across Wales and a pilot study into the interpretation of calculated globulin were undertaken. LFTs are performed in very high numbers (1·9 million/year for a population of 3·06 million in Wales) with total protein already included. Even if not tested as standard within the LFT profile the inclusion of total protein is inexpensive, costing £0·07, US$0·11 or €0·08 per test.

CG also fulfils the accepted criteria for a screening test based on those developed originally by the World Health Organization (WHO), which encompass the condition, the test and the treatment [12]. These state that the condition should be an important health problem, the natural history should be understood and there should be a detectable risk factor, disease marker, recognizable latent or early symptomatic stage. The test should be simple, safe, precise and validated with a defined cut-off level. The test should be acceptable to the population and there should be an agreed policy on the further investigation of individuals with a positive result. There should be an effective treatment or intervention for patients identified through early detection, with evidence of early, rather than late, treatment leading to better outcomes.

In the setting of PID, such as CVID, immunoglobulin replacement remains the mainstay of treatment, reduces infection frequency and severity and increases life expectancy. Higher doses of immunoglobulin are associated with reduced infection frequency [13,14]. Late diagnosis and delayed institution of immunoglobulin replacement therapy results in increased morbidity and mortality [15,16]. There is now a large range of immunoglobulin treatment options for patients comprising intravenous (IVIg), subcutaneous (SCIg) weekly or biweekly, facilitated subcutaneous (fSCIg) and rapid push [13,17–19] made possible by improvements in immunoglobulin manufacturing, resulting in more concentrated products, faster infusion rates using IVIg and for fSCIg the development of recombinant human hyaluronidase (rhuPH20) [19,20].

Methods

A survey was carried out via the Wales Biochemistry audit group using a questionnaire to determine current practice with respect to the use of calculated globulin (CG) across the 13 biochemistry laboratories in Wales. All questionnaires were returned and the data analysed using Microsoft Excel.

An analysis of anonymized adult (> 16 years) samples with a range of CG levels from 15 to 22 g/l was undertaken for 50 samples at each level of CG (Abbott Diagnostics, Maidenhead, UK) using the colorimetric bromocresol green (BCG) method for albumin and the Architect Biuret method (16200 Abbott Analyzer; Abbott Diagnostics) for total protein (TP). Immunoglobulin levels were then measured by nephelometry (Siemens BN2 Nephelometer; Siemens, Camberley, UK) to confirm the relationship between CG and IgG and to identify an appropriate cut-off value for subsequent study. Testing was carried out in clinical pathology-accreditated (CPA) laboratories.

Based on the results of the pilot study, ethical and research and development committee approval was obtained for a more detailed study of samples having CG levels of < 18 g/l from nine participating hospitals in Wales [University Hospital of Wales (UHW), University Hospital Llandough, Velindre Hospital, Royal Gwent Hospital, Neville Hall Hospital, Caerphilly Miners Hospital, Bronglais Hospital, West Wales General Hospital and Prince Charles Hospital]. Samples collected from adults (age > 16 years) during a period of 1 year were anonymized and sent to UHW for assay of immunoglobulin levels (IgG, IgA and IgM) (Siemens BN2 Nephelometer; Siemens), serum electrophoresis (Sebia Capillarys 2; Sebia, Norcross, GA, USA) and, where appropriate, serum immunofixation (Sebia Hydrasys; Sebia). The laboratory and clinical data were analysed using Microsoft Excel and Graphpad Prism version 6. Duplicate samples were identified through the patient initials, sex, age, source or location of request and clinical details, and removed from further analysis. The initial presence of duplicate samples, however, resulted in improved capture of clinical details. The results were presented to the biochemistry department at UHW and reporting practice audited 1 year later.

Following a subsequent change in the measurement method of albumin from BCG (Abbott Architect) to bromocresol purple (BCP) (Abbott Architect) in our centre, a further study was performed to identify the method-specific CG cut-off using 25 anonymized samples for each CG level from 19 g/l to 26 g/l, as there was predicted to be a change in the albumin value between the methods. Results were analysed using the ‘Analyse it Method Validation’ edition in Microsoft Excel and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves used to identify the most appropriate cut-off for the BCP method.

Results

The survey of practice with respect to use and interpretation of CG results was performed with responses from all 13 biochemistry laboratories in Wales (population 3·06 million), and the findings showed that approximately 1·9 million LFTs were performed across Wales, with 0·82 million of these in primary care. Although analytical platforms were different between the laboratories, all were using the BCG method for measuring serum albumin and the Biuret method for total protein measurement. Conversely, there was no consistent reference range for CG, varying at the upper end of the range from 35 to 45 g/l and at the lower end from ‘no lower limit’ to 20–28 g/l. At the lower end of the range, seven of the 10 laboratories reporting CG either took no action or did not report low levels of CG, while two flagged low results and one reviewed results if < 25 g/l (three laboratories did not report CG).

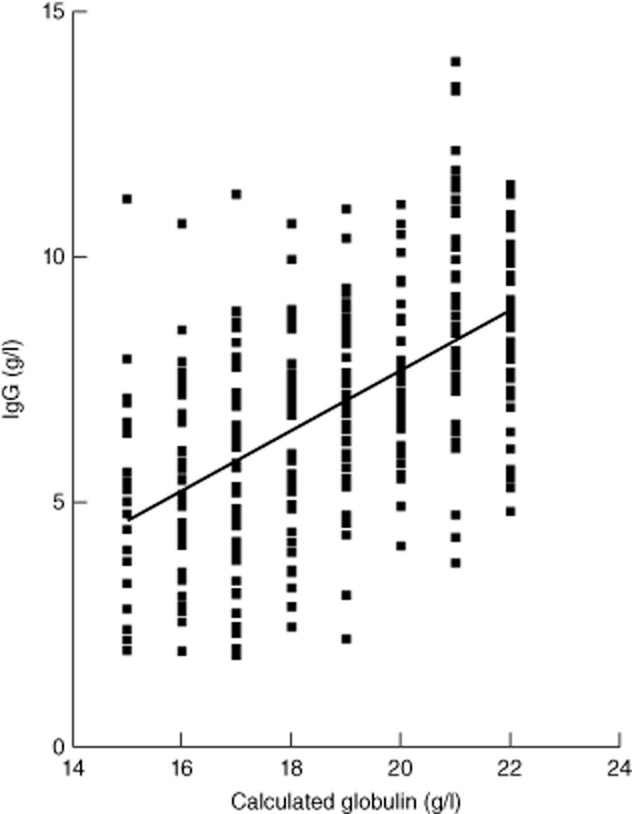

The pilot study showed a linear relationship between values of IgG and CG with a wide range of IgG levels for each level of CG (Fig. 1), with a CG of 18 g/l corresponding with an IgG of 6 g/l, the lower limit of the normal range (6–16 g/l). The cut-off value of CG < 18 g/l was chosen which corresponded to a sensitivity of 0·82 and a specificity of 0·71 for an IgG < 3 g/l (Table 2). Following the presentation of these data to the biochemistry department a number of samples with low CG were referred to immunology for immunoglobulin levels, and at least one patient was diagnosed with PID and commenced on replacement immunoglobulin therapy. However, audit 1 year later of 100 random samples with a CG of <18 g/l showed no action/comments on any sample from biochemistry.

Figure 1.

Correlation of calculated globulin levels with immunoglobulin (Ig)G. Fifty samples obtained anonymously for each level of calculated globulin (CG) at 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 and 22 g/l were tested for immunoglobulin levels and the correlation with IgG is shown. An IgG of 6 g/l corresponded to a CG level of 18 g/l and this was selected as the cut-off value for the bromocresol green (BCG) method.

Table 2.

Comparison of sensitivity and specificity using BCG and BCP methods

| IgG < 3 g/l | IgG < 4 g/l | IgG < 5 g/l | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| Calculated globulin cut-off for BCG (g/l) | ||||||

| < 16 | 0·24 | 0·95 | 0·15 | 0·95 | 0·11 | 0·96 |

| < 17 | 0·53 | 0·83 | 0·45 | 0·84 | 0·39 | 0·87 |

| < 18 | 0·82 | 0·71 | 0·78 | 0·74 | 0·66 | 0·78 |

| < 19 | 0·94 | 0·58 | 0·90 | 0·61 | 0·81 | 0·65 |

| < 20 | 1·00 | 0·41 | 0·98 | 0·44 | 0·92 | 0·48 |

| < 21 | 1·00 | 0·28 | 0·98 | 0·29 | 0·95 | 0·32 |

| < 22 | 1·00 | 0·14 | 1·00 | 0·14 | 0·99 | 0·16 |

| Calculated globulin cut-off for BCP (g/l) | ||||||

| < 20 | 0·24 | 0·89 | 0·26 | 0·92 | 0·21 | 0·92 |

| < 21 | 0·48 | 0·78 | 0·51 | 0·83 | 0·45 | 0·87 |

| < 22 | 0·64 | 0·66 | 0·66 | 0·71 | 0·63 | 0·77 |

| < 23 | 0·76 | 0·54 | 0·79 | 0·59 | 0·77 | 0·65 |

| < 24 | 0·84 | 0·41 | 0·87 | 0·45 | 0·85 | 0·50 |

| < 25 | 0·96 | 0·28 | 0·94 | 0·31 | 0·92 | 0·35 |

| < 26 | 1·00 | 0·14 | 1·00 | 0·16 | 1·00 | 0·20 |

Sensitivity and specificity of variable cut-off for immunoglobulin (Ig) G below set value when using bromocresol green (BCG) and bromocresol purple (BCP) methods for albumin and Biuret method for total protein.

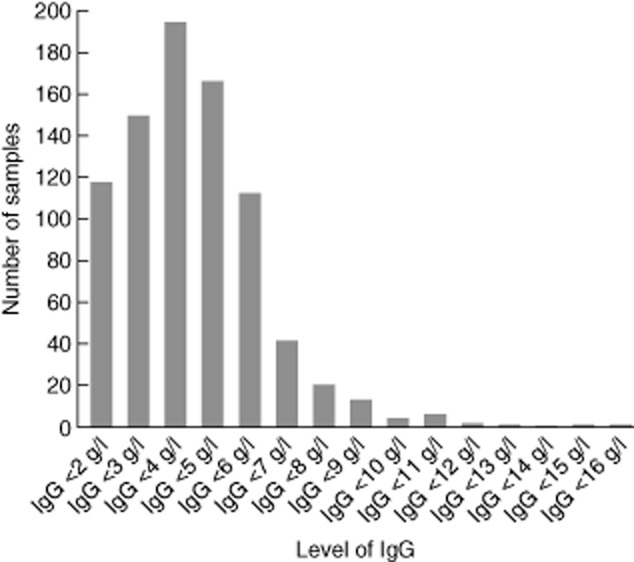

In the study of serum samples with CG < 18 g/l from nine hospitals in Wales, after exclusion of duplicates (on the same patient), 826 samples were tested for immunoglobulin levels and serum electrophoresis with the addition of immunofixation to confirm and type any paraproteins. The results demonstrated that 89% of samples had an IgG of < 6 g/l (adult normal range 6–16 g/l) and 56% had an IgG < 4 g/l with the distribution shown in Fig. 2, supporting the chosen cut-off value of < 18 g/l using the BCG method. The BCP method, using a cut-off of < 23 g/l for CG, had a sensitivity of 0·76 and specificity of 0·54 at an IgG level of < 3 g/l (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Numbers of samples at each level of immunoglobulin (Ig)G. The numbers of samples at each level of IgG are shown for samples with a calculated globulin (CG) of < 18 g/l with only 11% of samples recorded with an IgG level in the normal range (6–16 g/l); 56% of samples had an IgG of < 4 g/l, which is 4 standard deviations below the mean for adults [bromocresol green (BCG) method].

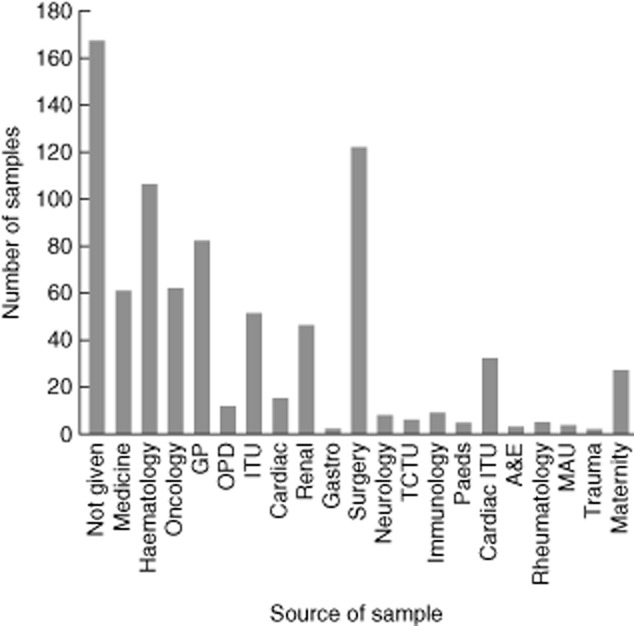

The sources of samples with an IgG < 6 g/l are shown in Fig. 3, with a wide range of clinical specialities and primary care represented. It is noteworthy that when the stringency in terms of significant antibody deficiency is increased by using an IgG level of < 4 g/l there is a major fall in samples from surgery of 122 to 20, perhaps suggesting that some of the changes associated with intravenous replacement of fluid or blood result in more limited reductions in antibody levels.

Figure 3.

Source of samples with an immunoglobulin (Ig)G < 6 g/l. A wide range of specialities is represented with a high number from surgery due probably to the use of intravenous fluids and blood products which may temporarily alter a calculated globulin (CG) [intensive care unit (ITU), general practice (GP), outpatients department (OPD), Teenage Cancer Trust unit (TCTU), accident and emergency (A&E), medical assessment unit (MAU].

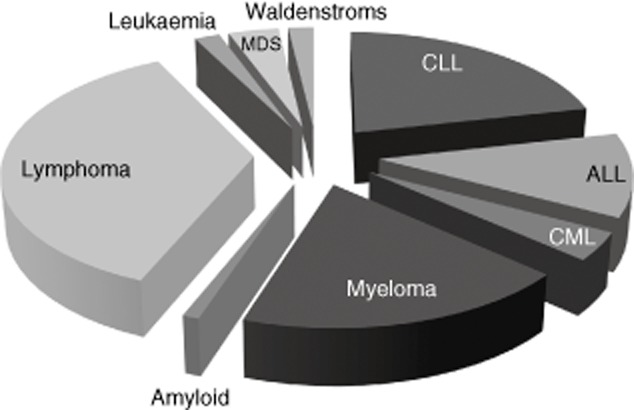

The speciality with the highest number of samples with low IgG apart from surgery was haematology, and the associated disorders with an IgG < 4 g/l are shown in Fig. 4. Unexpectedly, the largest diagnostic group was lymphoma, at 34%, rather than CLL at 20%; however, it is possible that some of the CLL patients may already be receiving immunoglobulin, which may lower the numbers of CLL patients with antibody deficiency detected by CG. The results identify substantial numbers of undiagnosed secondary antibody-deficient patients, including some with neutropenic sepsis or pneumonia stated in the clinical information on the request form. A similar pattern is seen with unrecognized antibody deficiency in samples from oncology.

Figure 4.

Haematology diagnoses with IgG < 4 g/l. The largest category of antibody-deficient patients from haematology is from requests labelled lymphoma [lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, renal lymphoma, Mantle cell lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), Burkitt's lymphoma and central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma] and a range of other haematological diagnoses reflecting either secondary antibody deficiency due to the disorder or subsequent to its treatment.

In addition to the antibody deficiency, in 1·2% of samples (10 of 826) a new, previously undetected small paraprotein with immune-paresis was identified, with IgG levels ranging from 1·93–4·8 g/l. The associated immune-paresis suggests that these patients may no longer fall into the category of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and would merit referral to haematology for further assessment and potential intervention.

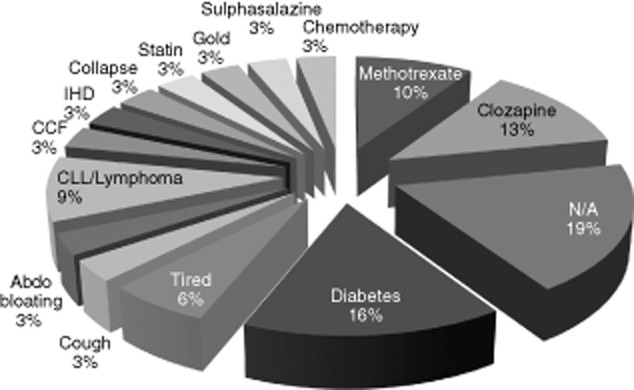

Clinical details on samples originating from primary care with IgG levels < 4 g/l are shown in Fig. 5. These highlight antibody deficiency in patients being monitored for immunosuppressive therapy and with a known diagnosis of CLL, but also in patients with diabetes, which is more difficult to explain, and with a range of non-specific symptoms such as tiredness and bloating.

Figure 5.

Diagnoses with immunoglobulin (Ig)G < 4 g/l from primary care. Diagnoses from 32 request forms from patients in general practice with IgG levels less than 4 g/l are shown. There are a significant number where drug monitoring is taking place and a number with a range of more non-specific symptoms. Congestive cardiac failure (CCF), ischaemic heart disease (IHD), chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and information not available (NA).

The impact of reduction in diagnostic delay on wellbeing, schooling, end-organ damage and the use of resources is demonstrated by the patient histories of three cases identified initially by low CG levels who were seen following the study.

Case 1

A 19-year-old male was referred to immunology on the basis of low CG. His mother recalled him constantly dribbling in infancy and she was told ‘his tongue was too big for his mouth’. He had tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy aged 4 years and three insertions of grommets and a hearing aid. He had a chronic cough from the age of 4 years and subsequently sinusitis and post-nasal drip. He suffered from 12–15 infections annually and lost 50–60 days of school per year. He was sent home from school as his coughing was disrupting the class, and recalled falling asleep in a geography examination as he had been coughing all night. When asked when he last felt well he said ‘never’, and rated his wellbeing as 3 out of 10. In the past year he had six courses of antibiotics, two admissions with pneumonia and had investigations for HIV and cystic fibrosis. During the previous 15 years it was estimated he would have visited his general practitioner (GP) on 180 occasions, and in 2012 he was found to have pan-hypogammaglobulinaemia with absent vaccine responses and was diagnosed as having CVID. Since commencing replacement immunoglobulin 18 months ago he has required no further admissions to hospital.

Case 2

A 23-year-old mechanic was referred to gastroenterology with blood in his stools aged 21 years and was investigated with endoscopies and diagnosed as having a distal colitis of indeterminate type. At this time his CG was 14, and treatment for colitis was commenced (Asacol) with little benefit. He was investigated for coeliac disease when a duodenal biopsy showed normal villous architecture with a lack of plasma cells, his CG was 15 and results showed IgA deficiency. In 2011, on the basis of the low CG, immunoglobulin levels were tested (IgG < 1·34 g/l, IgA < 0·06 g/l, IgM < 0·17 g/l) and he was referred to immunology. At this time he had had watery or semi-formed motions eight times per day for 3–4 years, suffered from joint pains, was coughing an eggcup of light green sputum per day for the past year, with sinusitis and a post-nasal drip, and had lost, on average, 40 days of work per year. He was found to have low numbers of class-switched memory B cells, did not respond to test vaccination with pneumovax II and so was diagnosed with CVID.

Immunoglobulin replacement therapy with Privigen 50 g intravenously every 3 weeks was commenced, and at his most recent follow-up his colitis had resolved with two formed motions per day and his previous colitis medication was discontinued. He no longer had a cough and his sinusitis, post-nasal drip and joint pains had settled. Prior to replacement immunoglobulin he rated his wellbeing as three out of 10 on a visual analogue scale, and in the year following commencement of immunoglobulin this improved to eight out of 10, and he missed no days from work.

Case 3

A 26-year-old female working for the university had a 9-year history of recurrent infections, including pneumonias requiring chest X-rays, intravenous antibiotics and admissions to hospital on three occasions. She felt she ‘has a constant chest infection for 6 months of the year’ and had been diagnosed as having irritable bowel syndrome. In the previous year she had lost 21 days from work, needed six courses of antibiotics and rated her wellbeing as 6 out of 10 on a visual analogue scale. In the previous 9 years she had had 72 visits to her GP and had been told she needed to explore psychological causes for her symptoms. Her CG was 18 g/l, with pan-hypogammaglobulinaemia (IgG < 1·34 g/l, IgA < 0·24 g/l, IgM < 0·17 g/l) and a poor response to vaccination. She was diagnosed with CVID and commenced on Subgam 6·75 g per week subcutaneously, and had a single visit to the GP in the year following the start of treatment, had no infections, required no antibiotics and felt the treatment had had a ‘brilliant effect on her quality of life’.

Discussion

There are no published studies of the utility of CG to screen for antibody deficiency, and the principal findings of the current study are that using appropriately established method-dependent CG cut-off values it is possible to detect primary and secondary antibody deficiencies, as well as small new paraproteins associated with immune-paresis. This approach fulfils the criteria of a screening test [12], and as a proof-of-principle, patients detected with low CG have been diagnosed with CVID and commenced on immunoglobulin replacement. Using the BCG methodology for albumin measurement and the Biuret method for total protein [21], a cut-off value of < 18 g/l for calculated globulin defines a population in which 89% have an IgG level of < 6 g/l.

A limitation of this study is that it did not evaluate the utility of CG in children, as the normal ranges for immunoglobulins vary with age; however, levels approximating the adult ranges are achieved by the age of 9–10 years [22] and potentially further studies could address whether screening using CG could be used from 10 years of age. Clinically, children below this age have a higher frequency of infection which declines with age.

There are several approaches to the introduction of electronic comments to aid clinicians. The most straightforward would be on samples from primary care, as the use of intravenous fluids (which may temporarily perturb CG levels) in this setting would be unlikely, and the patients in the case histories all reported frequent contact with their GP. Several comments were developed for a low CG in primary care and the GP laboratory management committee liaison group selected the following comment on the basis that it interprets the underlying abnormality and suggests action which may be considered in the appropriate clinical setting: ‘Low calculated globulin may represent antibody deficiency. Consider immunoglobulin measurement if there is a history of infections’.

In secondary care a similar comment could be used, with an added caveat that intravenous fluid administration in surgical, medical or intensive care may cause a temporarily low CG.

Some laboratories could also choose to cascade directly on discovery of a low CG, adding immunoglobulins and SEP as deemed appropriate; however, this may be hampered by the frequent lack of clinical data on the request form and the requesting clinician may be in the best position to make the most informed decision, potentially also limiting costs.

With increasing pressure on health resources, the removal of total protein has been advocated on cost grounds. As part of the process of test profile harmonization and demand management [23] it has been suggested that ‘its inclusion is more as an opportunistic screening test for monoclonal gammopathy, but no specific intervention exists other than watchful waiting’ [24].

Data from the current study, however, argue that the range of disorders for which additional information is gained is wider than monoclonal gammopathy (Table 1); in particular, when defined cut-offs are in place, there are clear treatment advances for multiple myeloma, clinically important monoclonal bands are detected with a low CG and screening criteria are fulfilled for both primary and secondary antibody deficiency. In addition, testing costs must be evaluated in the context of the complete patient pathway, the utility losses associated with delay in the diagnosis of patients, the benefits associated with accurate immunological testing and the potentially increased use of health resources if the test is not performed. Where the test is already being performed it would seem reasonable to obtain best value for money by education regarding its use at both ends of the reference range.

There may be circumstances when an antibody deficiency does not require immunoglobulin replacement, but further investigation, monitoring and treatment may still be altered in the light of the result and the clinician and patient are able to proceed in a more informed manner.

The increasing use of B cell ablation therapy across a range of specialities (in particular haematology) and the growth of maintenance therapy with rituximab, alongside the development of a range of agents targeting B cells for malignant, autoimmune and inflammatory indications, is likely to result in an increase in secondary antibody deficiency in a subset of these patients, further increasing the potential utility of CG. In chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL), 30–50% of deaths are due to infection caused by secondary antibody deficiency, T cell defects and the effects of therapy [25].

Variations in detection rate may be expected, as the populations being tested will be different for different laboratories and health settings. The presence of a large haematology department and oncology centre will have influenced the results in terms of secondary antibody deficiency in this study. The ability of CG to be used as a screening test should be widely applicable, regardless of the presence of major hospitals or specialist services. Given the low costs of testing, use of CG may also be relevant in resource-poor settings.

The information presented by this study could be used to inform health policy regarding the most appropriate test profiles to use. There is the potential to reduce diagnostic delay, optimize the use of health resources and reduce the burden of disease not only for patients with antibody deficiency but also a much wider range of conditions. CG is an underutilized test which is cheap (£0·07, US$0·11 or €0·08), widely available and fulfils the need for a screening approach for antibody deficiency.

Acknowledgments

S. J. and A. H. are supported by NISCHR Fellowships. Support for consumables was provided in a grant from CSL Behring. The support of the Wales Biochemistry Audit group is acknowledged in gathering information about current practice for CG in Wales.

Disclosures

T. E. has received payment from Biotest and CSL Behring for attendance at advisory board meetings. S. J. has received support from CSL Behring, Baxter, Biotest, BPL and Octapharma for projects, advisory boards, meetings and clinical trials.

References

- 1.Jolles S. The variable in common variable immunodeficiency: a disease of complex phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:545–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham-Rundles C. How I treat common variable immune deficiency. Blood. 2010;116:7–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-254417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Vries E. Patient-centred screening for primary immunodeficiency, a multi-stage diagnostic protocol designed for non-immunologists: 2011 update. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167:108–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham-Rundles C, Sidi P, Estrella L, Doucette J. Identifying undiagnosed primary immunodeficiency diseases in minority subjects by using computer sorting of diagnosis codes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:747–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subbarayan A, Colarusso G, Hughes SM, et al. Clinical features that identify children with primary immunodeficiency diseases. Pediatrics. 2011;127:810–816. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bright P, Lock RJ, Unsworth DJ. Immunoglobulin A deficiency on serological coeliac screening: an opportunity for early diagnosis of hypogammaglobulinaemia. Ann Clin Biochem. 2012;49(Pt 5):503–504. doi: 10.1258/acb.2012.012011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unsworth DJ, Virgo PF, Lock RJ. Immunoglobulin E deficiency: a forgotten clue pointing to possible immunodeficiency? Ann Clin Biochem. 2011;48(Pt 5):459–461. doi: 10.1258/acb.2011.011052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verbsky JW, Baker MW, Grossman WJ, et al. Newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency; the Wisconsin experience (2008–2011) J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:82–88. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9609-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borte S, von Dobeln U, Fasth A, et al. Neonatal screening for severe primary immunodeficiency diseases using high-throughput triplex real-time PCR. Blood. 2012;119:2552–2555. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-371021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borte S, Janzi M, Pan-Hammarstrom Q, et al. Placental transfer of maternally-derived IgA precludes the use of guthrie card eluates as a screening tool for primary immunodeficiency diseases. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e43419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnold DF, Wiggins J, Cunningham-Rundles C, Misbah SA, Chapel HM. Granulomatous disease: distinguishing primary antibody disease from sarcoidosis. Clin Immunol. 2008;128:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.03.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson JMG, Jungner G. 1968. Principles and practice of screening for disease. Public Health Papers 34: 1–163. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO)

- 13.Orange JS, Belohradsky BH, Berger M, et al. Evaluation of correlation between dose and clinical outcomes in subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;169:172–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orange JS, Grossman WJ, Navickis RJ, Wilkes MM. Impact of trough IgG on pneumonia incidence in primary immunodeficiency: a meta-analysis of clinical studies. Clin Immunol. 2010;137:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood P, Stanworth S, Burton J, et al. Recognition, clinical diagnosis and management of patients with primary antibody deficiencies: a systematic review. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;149:410–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aghamohammadi A, Moin M, Farhoudi A, et al. Efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin on the prevention of pneumonia in patients with agammaglobulinemia. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;40:113–118. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00304-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger M, Murphy E, Riley P, Bergman GE. Improved quality of life, immunoglobulin G levels, and infection rates in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases during self-treatment with subcutaneous immunoglobulin G. South Med J. 2010;103:856–863. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181eba6ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shapiro RS. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin: rapid push vs. infusion pump in pediatrics. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24:49–53. doi: 10.1111/pai.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wasserman RL, Melamed I, Stein MR, et al. Recombinant human hyaluronidase-facilitated subcutaneous infusion of human immunoglobulins for primary immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:951–7 e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jolles S. Hyaluronidase facilitated subcutaneous immunoglobulin in primary immunodeficiency. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2013;2:125–133. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S31136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corcoran RM, Durnan SM. Albumin determination by a modified bromocresol green method. Clin Chem. 1977;23:765–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milford Ward A, Sheldon J, Rowbottom A, Wild GD, editors. Handbook of clinical immunochemistry. 9th edn. Sheffield: PRU Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fryer AA, Smellie WS. Managing demand for laboratory tests: a laboratory toolkit. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66:62–72. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smellie WS. Time to harmonise common laboratory test profiles. BMJ. 2012;344:e1169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francis S, Karanth M, Pratt G, et al. The effect of immunoglobulin VH gene mutation status and other prognostic factors on the incidence of major infections in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2006;107:1023–1033. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]