Abstract

An 8-month-old cat was presented with bilateral hydronephrosis. Bilateral ureteral obstructions were identified by diagnostic imaging and confirmed by necropsy. Histopathologic findings revealed polypoid transitional epithelial hyperplasia with chronic lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. This report documents congenital ureteral strictures as a cause of ureteral obstruction in a young cat.

Résumé

Constriction urétérale bilatérale congénitale chez un jeune chat. Un chat âgé de 8 mois a été présenté avec une hydrophénose bilatérale. Des obstructions urétérales bilatérales ont été identifiées par imagerie diagnostique et confirmée par nécropsie. Les résultats histopathologiques ont révélé une hyperplasie épithéliale polypoïde transitionnelle avec une inflammation lymphoplasmacytique chronique. Ce rapport documente les constrictions urétérales congénitales comme cause de l’obstruction urétérale chez un jeune chat.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Ureteral obstruction results most commonly from ureteral calculi; however, iatrogenic ligation, blood clots, tumor, stricture, and solidified blood stones have been reported as a cause in cats (1–5). Ureteral stricture is defined as a circumscribed narrowing of the ureteral lumen (5). Feline ureteral strictures have rarely been reported and the majority are secondary to passage of stones and ureteral surgery. Minor predisposing conditions for secondary stricture are intrinsic or extrinsic neoplasia, retroperitoneal fibrosis, and circumcaval ureter (5).

Congenital ureteral stricture is rarely reported in cats. Unilateral proximal and mid-ureteral stricture was reported in an 8-month-old cat and the authors suspected a congenital cause (6). A retrospective report detailed 2 cats which were suspected of congenital unilateral stricture, because no underlying cause was identified (5). However, histopathological examination was not performed to determine if the cats had stricture. Bilateral ureteropelvic junction stenosis was reported in a cat in which histopathologic examination revealed a congenital malformation with a patent ureteral lumen (7). This report describes bilateral ureteral strictures as a cause of ureteral obstruction in a young cat.

Case description

An 8-month-old, 3.5-kg, castrated male Abyssinian cat was referred to Haemaru Referral Animal Hospital with a 1-week history of vomiting and depression. A biochemistry panel, complete blood (cell) count (CBC), and urine analysis were performed. The results indicated severe azotemia with a blood urine nitrogen (BUN) of over 46 mmol/L [reference range (RR): 6.4 to 11.8 mmol/L], and creatinine of 1184 μmol/L (RR: 97 to 194 μmol/L). The CBC was within the normal range. Urine specific gravity (1.011) was suggestive of mild impairment in urine concentration (RR: > 1.015). Urine culture was not performed.

Bilateral renomegaly was noted on the abdominal radiograph. There was no radiopaque urolith. Abdominal ultrasonography performed with a 7.5 MHz linear array and 5.0 MHz convex transducer showed bilateral hydronephrosis and hydroureter. The pelvis of the left kidney was 2.2 cm in length. The proximal left ureter was tortuous with mild dilation (3 mm diameter) and the mid-ureter was narrowed (2.4 mm) with a markedly thickened wall. The distal ureter was not remarkable. The left hydronephrosis was postulated to be caused by a thickened mid-ureteral wall. The pelvis of the right kidney was 2.5 cm in length. The right ureter was dilated (3 mm) from its proximal to its distal extremities; the wall of the ureter was not remarkable (Figure 1). No obstructive material was identified in the ureter. Antegrade pyelography was performed for exact localization of the ureteral obstruction. Iodine contrast medium equal to one-half the volume of urine removed by nephropyelocentensis was injected into the renal pelvis under ultrasound guidance (8). Dilation of the left proximal to mid-ureter and of the right proximal to distal ureter was immediately detected after injection of contrast media; contrast media did not extend to either of the distal ureters or the urinary bladder. A radiograph taken at 30 min after injection showed a filling defect in the right distal ureter and a tortuous course of the right distal ureter to the urinary bladder. A filling defect at the left mid-ureter and a normal left distal ureter were shown at 60 min after injection. Antegrade pyelography confirmed partial obstructions in the left mid ureter and the right distal ureter (Figure 2). Bilateral ureterovesicular junctions could not be evaluated because of insufficient contrast media extension to the urinary bladder. Hence retrograde double contrast cystography was performed for evaluation of the ureterovesicular junction and ectopic ureter was excluded.

Figure 1.

Ultrasonographic image of kidneys and ureters. Bilateral hydronephrosis (A, D) and hydroureters (B, E, F) are present. The left mid-ureteral wall is focally thick (B, white arrow) and the distal ureter is normal (C). The lesion of the right ureteral wall is not identified (E, F).

Figure 2.

Antegrade pyelography of kidneys. Dilation and tortuous course of the ureters (left: thin white arrow, right: thin black arrow) are detected immediately after injection of contrast medium (A). A filling defect in the right distal ureter (thick black arrow) at 30 min (B) and a filling defect in the left mid-ureter (thick white arrow) at 60 min are shown (C). These findings confirmed partial obstruction in both ureters.

The azotemia worsened with BUN of 87.5 mmol/L and creatinine of 1397 μmol/L despite hospitalization. The cat’s condition was aggravated by a blood pressure of 60 to 70 mmHg, and euthanasia was requested by the owner. On necropsy, bilateral hydronephrosis was identified with no obstructive material. The left mid-ureteral lumen was narrowed with a firm and thickened wall, the right distal ureter had similar luminal narrowing. These findings confirmed bilateral ureteral strictures (Figure 3). Histopathological findings revealed the presence of an irregular region of papillary hyperplasia of the luminal transitional epithelium with luminal projections of stromal tissue and hyperplastic epithelium. The epithelial components were well-differentiated. There was mild lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (Figure 4). Immunohistochemical tests excluded feline infectious peritonitis virus in the ureteral lesion.

Figure 3.

The left mid-ureter. The lesion in the ureteral wall (white and black arrows) is shown as firm and thick (A, B). The lumen is narrowed (C, thick black arrow).

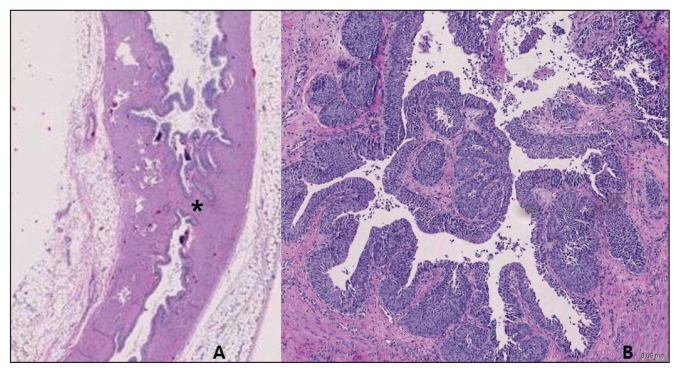

Figure 4.

Histopathology revealed an irregular region of papillary hyperplasia of the luminal transitional epithelium with luminal projections of stromal tissue and hyperplastic epithelium (A, asterisk). The epithelial components are well-differentiated (B).

Discussion

Ureteral strictures are typically due to ischemia, resulting in fibrosis (9). Histopathological findings of feline ureteral stricture include mural granulation tissue with epithelial cell disruption, ureteritis with fibrosis and inflammation or muscle hypertrophy (5). Congenital ureteral stricture has been well-described in humans (10–14). Histopathological findings are increased, decreased, or disorganized arrangements of the ureteral musculature, with or without fibrosis, accompanied by normal urothelium (10). Similar findings have been reported for one dog (15), but another dog was reported to have transitional cell hyperplasia in bilateral ureteral stricture, instead of abnormal muscularis (16). No disorganization of muscularis was observed in the present case. Instead, there was polypoid/papillary transitional epithelial hyperplasia with chronic lymphoplasmacytic inflammation in the ureteral lesion. A diagnosis of bilateral congenital ureteral strictures was made in this case, because no underlying cause was identified. Although it is unclear whether these findings are typical for congenital feline ureteral stricture, the pathophysiology of congenital ureteral stricture in small animals, particularly in cats, is suspected to be different from that of humans and further research into these differences is required.

The diagnosis of ureteral stricture is ideally made with histopathological findings associated with narrowing of the ureteral lumen (5). However, biopsy is not typically performed on ureteral lesions unless ureteronephrectomy or partial ureterectomy is performed; therefore, diagnostic imaging can be useful. Abdominal radiography can identify renomegaly and is useful for the identification of radiopaque urinary calculi, which may be the underlying cause of the ureteral stricture. Abdominal ultrasound shows hydronephrosis and hydroureter with excellent resolution, and is useful for the identification of both radiopaque and non-radiopaque (blood clot, mucus plug, dried solidified blood stones) materials in ureters, documenting whether there is any intraluminal cause. However, it may be of limited value in determining the location of distal ureteral obstruction. In this case, right distal ureteral stricture was not identified by ultrasound examination. Ultrasound did show focal thickening of the left mid-ureteral wall, leading to suspicion of ureteral stricture. Percutaneous antegrade pyelography has been used in diagnosis and localization in dogs and cats (17). In this case, percutaneous antegrade pyelography was also useful in the localization of strictures.

In conclusion, ureteral strictures should be considered as a cause of ureteral obstruction in cats when obstruction without an intraluminal cause is documented by diagnostic imaging. Furthermore, in young cats, congenital ureteral strictures should also be considered as a cause of ureteral obstruction. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Hardie EM, Kyles AE. Management of ureteral obstruction. Vet Clin Small Anim. 2004;34:989–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyles AE, Hardie EM, Wooden BG, et al. Clinical, clinicopathologic radiographic, and ultrasonographic abnormalities in cats with ureteral calculi: 163 cases (1984–2002) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;226:932–936. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.226.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyles AE, Hardie EM, Wooden BG, et al. Management and outcome of cats with ureteral calculi: 153 cases (1984–2002) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;226:937–944. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.226.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westropp JL, Ruby AL, Bailiff NL, et al. Dried solidified blood calculi in the urinary tract of cats. J Vet Intern Med. 20:828–834. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2006)20[828:dsbcit]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaid MS, Berent AC, Weisse C, Caceres A. Feline ureteral strictures: 10 cases (2007–2009) J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:222–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.0679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zotti A, Poser H, Chiavegato D. Asymptomatic double ureteral stricture in an 8-month-old Maine Coon cat: An imaging-based case report. J Feline Med Surg. 2004;6:371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster JD, Pinkerton ME. Bilateral ureteropelvic junction stenosis causing hydronephrosis and renal failure in an adult cat. J Feline Med Surg. 2012;12:938–941. doi: 10.1177/1098612X12458102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivers BJ, Walter PA, Polzin DJ. Ultrasonographic-guided, percutaneous antegrade pyelography: Technique and clinical application in the dog and cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1997;33:61–68. doi: 10.5326/15473317-33-1-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldfischer E, Gerber G. Endoscopic management of ureteral strictures. J Urol. 1997;157:770–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosto B. Congenital mid-ureteral stricture in a solitary kidney. J Urol. 1971;106:529–531. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)61333-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayyat FM, Adams G. Congenital midureteral strictures. Urology. 1985;26:170–172. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(85)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gitlin J, Kaefer M. Congenital mid ureteral stricture presenting as prenatal hydronephrosis. J Urol. 2002;168:1154–1155. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64615-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang AH, McAleer IM, Shapiro E, Miller OF, Krous HF, Kaplan GW. Congenital mid ureteral strictures. J Urol. 2005;174:1999–2002. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000176462.56473.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domenichelli V, Biagi LD, Italiano F, Carfagnini F, Lavacchini A, Federici A. Congenital bilateral mid-ureteral stricture: A unique case. J Pediatr Urol. 2008;4:401–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2008.01.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pullium JK, Dillehay DL, Webb S, Pinter MJ. Congenital bilateral ureteral stenosis and hydronephrosis in a neonatal puppy. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2000;39:34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Şahal M, Haziroglu R, Özkanlary Y, Beyaz L. Bilateral hydronephrosis and hydroureter in a German shepherd dog. Ankara Üniv Vet Fak Derg. 2005;52:193–196. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adin CA, Herrgesell EJ, Nyland TG, et al. Antegrade pyelography for suspected ureteral obstruction in cats: 11 cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;222:1576–1581. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.222.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]