Summary

Kin recognition can enhance inclusive fitness via nepotism and optimal outbreeding. Mechanisms allowing recognition of patrilineal relatives are of particular interest in species in which females mate promiscuously, leading to paternity uncertainty. Humans are known to detect facial similarities between kin in the faces of third parties [1–4], and there is some evidence for continuity of this ability in non-human primates [5–7]. However no study has yet shown that this propensity translates into an ability to detect one's own relatives, one of the key prerequisites for gaining fitness benefits. Here we report a field experiment demonstrating that free-ranging rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) spontaneously discriminate between facial images of their paternal half-siblings and unrelated individuals, when both animals are unfamiliar to the tested individual. Specifically, subjects systematically biased their inspection time towards non-kin when the animals pictured were of their own sex (potential threats), relative to when they were of the opposite sex (potential mates). Our results provide strong evidence for visual phenotype matching, and the first demonstration in any primate that individuals can spontaneously detect their own paternal relatives on the basis of facial cues under natural conditions.

Results and Discussion

Whether and how paternal kin can be identified is of particular interest in those mammalian species in which females typically mate with multiple males during their likely conception period, leading to paternity uncertainty. While in primates evidence for behavioral discrimination of paternal kin is accumulating (e.g. [8–13], but see [14–16] for discussion of early negative results), the underlying mechanism(s) and cues used in this process remain largely untested. Identification of relatives may result from familiarity during early development (e.g. spatial associations mediated by a common parent or site) and/or phenotype matching (in which a target phenotype is compared with a template derived from either oneself or a known relative, [17]). Phenotype matching is expected to play a particularly important role in recognition of paternal relatives, which are less likely to be familiar with one another than are maternal relatives [15]. However, evidence for phenotype matching in primates remains limited [18, 19], particularly under natural conditions (although see [14] for an exception). In humans, the strongest evidence comes from the visual modality [1–4], which has generated interest in whether other primates share our ability to identify familial resemblances using facial cues.

In an intriguing study, Parr and colleagues [19] demonstrated that captive chimpanzees and rhesus macaques succeed in discriminating mother- and father-offspring dyads of both sexes from unrelated individuals, in an onscreen task using faces of adult conspecifics. Although promising, the results were obtained from a small sample of captive individuals and achieved after extensive training (a necessary precursor in ‘match-to-sample’ tasks), thus providing limited information concerning the saliency of these cues under natural conditions. Moreover, for facial cues to function in kin recognition under natural conditions, familial resemblances need to be detectable even against the background levels of relatedness typical of demes in the wild, a condition not necessarily met in existing captive studies [7].

Here, we test whether free-ranging adult rhesus macaques spontaneously discriminate patrilineal kinship in the faces of unfamiliar conspecifics, using a 'differential looking time' paradigm. The logic behind differential looking time experiments is that animals look for longer at the one of two stimuli that they find more salient, interesting, or surprising in some way. If they systematically attend more towards one type of stimulus than another, they must be capable of discriminating between the two along the dimension(s) in which the types differ, here relatedness. This technique is widely used for non-verbal cognitive tasks in both human infants [20] and other primates [21], including macaques [22, 23] – in which the method has demonstrated an ability to distinguish between the faces of familiar vs. unfamiliar conspecifics [23]. In this study, the term ‘kin discrimination’ refers to an ability to identify or distinguish kin vs. non-kin [24]; our methodological approach does not test for subsequent preferential treatment of kin vs. non-kin.

Making use of the social organization of rhesus macaques, we aim to approach the underlying mechanism of paternal kin discrimination. Rhesus macaques reside in multi-male, multi-female groups, with males changing groups several times in their reproductive career [25], creating a situation in which paternal kin can grow up in different groups and are hence largely unfamiliar with one another. Given this situation we were able to control for the possible confounding effect of differential social familiarity with relatives and other individuals (see also [14] for discussion). This aspect is crucial for isolating the potential role of phenotype matching, but has not yet been achieved in any primate study testing the ability to visually identify one's own kin. We chose to investigate discrimination of paternal half-siblings, a kin class which is particularly common in many species of primates as male reproduction is often highly skewed towards a few sires [26, 27]. Recognition of one's half-siblings potentially allows both sexes to avoid mating with kin, even when unfamiliar, and to associate with relatives in prosocial contexts. Unlike previous studies, our design examines the key issue of whether individuals can recognize their own relatives' faces, rather than resemblances between third parties. Both males and females served as subjects, presented with same- or opposite-sex stimuli, in order to contrast patterns of response toward stimuli portraying possible rivals versus mates. The study was conducted using multiple social groups of a large free-ranging population, in which genetic relationships were determined from an extensive pedigree constructed using molecular markers (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures 2).

Overall, we found that the proportion of time that a subject looked towards the kin vs. the non-kin image was influenced in a consistent manner by the subject's sex, its age and the sex of the images presented (comparison of full vs. null model, Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT): χ2=17.204, df =7, p=0.016, see also Table 1 and Supplemental Experimental Procedures 4). As the only consistent difference between the faces in each of our image pairs was their level of genetic relatedness to the subject, the biases in response demonstrate that rhesus can discriminate unfamiliar paternal half-siblings from unfamiliar unrelated conspecifics in their local population. This is in line with previous research indicating that information about paternal kinship is encoded in the faces of rhesus macaques [7, 28] and can be perceived by conspecifics [19]. Our study however provides the first experimental evidence for spontaneous visual discrimination of paternal relatives under natural conditions and without any training in the task in any non-human primate. Moreover it demonstrates that the perceptual saliency of the facial cues to conspecifics is not limited to information about father-offspring relationships (coefficient of relatedness r=0.5, [19]), but extends to more distant patrilineal kin (half-siblings, r=0.25). Importantly, these more distant familial resemblances were detectable even against an expected degree of background relatedness in the population, which potentially increases the baseline levels of facial similarity present among ‘non-kin’ (cf. [7]). Our design enabled us to rule out differential familiarity as the underlying mechanism, thus providing strong evidence for visual phenotype matching in kin recognition.

Table 1.

Results of the linear mixed model examining the probability that a subject looks towards the kin image of a pair (final model).

| Predictor variable | Estimate | SE | χ 2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.446 | 0.037 | |||

| Subject sex (female = 0, male = 1) | 0.074 | 0.045 | |||

| Image sex (female = 0, male = 1) | 0.079 | 0.051 | |||

| Subject age | 0.035 | 0.018 | 3.220 | 1 | 0.073 |

| Side kin presented(1) | −0.035 | 0.032 | 1.106 | 1 | 0.293 |

| Subject sex (male) : Image sex (male) | −0.200 | 0.063 | 9.256 | 1 | 0.002 |

Side presented was dummy coded and centered, with side on which the non-kin image was presented being the reference category.

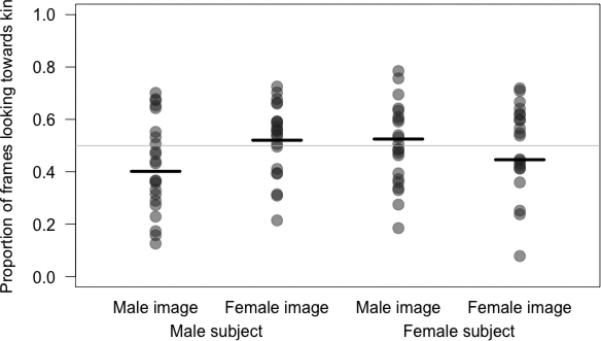

Our results further revealed a sex-specific pattern: the direction of visual bias showed an interaction between the sex of the test subject and of the images viewed (LRT: χ2=9.256, df=1, p=0.002, Table 1). Subjects presented with same-sex images looked longer toward the non-kin image of a pair than did those tested with opposite-sex images (Figure 1). Although it is difficult to establish unequivocally the underlying biological significance of specific response biases using the preferential looking time paradigm, it is likely that the observed bias toward non-kin faces when viewing individuals of one's own sex is due to the greater threat such individuals pose. Presenting the face of an unfamiliar conspecific simulates the presence of a rival group or immigrant individual, and generally creates a situation of increased vigilance (cf. [23]). This should be particularly true for residents of the same sex, for whom such an intruder represent greater potential competition for access to limited resources. In situations of threat, both humans and rhesus monkeys have been shown to bias their attention toward the more threatening of two faces [29, 30], a bias postulated to provide fitness benefits in terms of faster detection of threat and therefore improved ability to defend against or escape danger (cf. [29]). As relatives are less likely to be the targets of aggression (once their greater time in shared proximity is taken into account) and are more likely to receive agonistic support (reviewed in [31]), an image depicting an unfamiliar non-kin individual of the same sex should receive more prolonged attention.

Figure 1.

Proportion of frames in which the subject looked toward the kin image in a pair (out of the combined time spent looking at both images), according to sex of the subject (male, female) and the images (same- vs. opposite-sex to subject). Horizontal black bars indicate the predicted values for looking preference from the model, while circles depict the response value for each subject. The horizontal grey line illustrates chance behavior (0.5); higher values indicate preferential looking toward the kin image and lower values preferential looking toward the non-kin image. To aid interpretation of model estimates, age (in days, log-transformed) was z-transformed, and side on which the kin image was presented was dummy-coded and centered, before inclusion in the model. N = 88 individuals.

In contrast, this bias was reversed to almost absent when individuals viewed images of the opposite sex (Figure 1), a scenario simulating the presence of a novel potential mate. Evaluating degree of kinship to prospective mates is useful in enabling optimal outbreeding (see [32] for a recent review). One possibility is that facial cues of relatedness are relatively unimportant when assessing mates, perhaps because natal dispersal by males at puberty, together with post-copulatory and/or post-conception mechanisms (e.g., sperm competition and cryptic female choice, respectively, [33]), are sufficient in this species as mechanisms for controlling inbreeding. Thus kin images might receive no more scrutiny than non-kin ones in opposite-sex trials. However, given that facial cues are available, one might expect them to be used to supplement mate selection decisions prior to investing in mating – particularly by females, the sex predicted to suffer more from any costs of inbreeding [34]. Facial resemblance between relatives is somewhat stochastic; which of a parent's alleles is transmitted to individual offspring is (largely) random in autosomal genes, while dominance, epistatic interactions and a variety of epigenetic processes also combine to affect the phenotypic expression of those alleles. Thus the parental line, and combination of specific features, via which two relatives resemble one another necessarily varies - even within a given level of kinship. Determining degree of kinship may therefore be a relatively complex task [35], taking more time than does exclusion of a non-relative from the class of possible kin, as (most) unrelated individuals will not exhibit the trait characteristics triggering a given individual's kin recognition template. This predicts a bias in looking time toward kin individuals. However, given that females are usually outranked by adult males in this species, presentation of a male face simultaneously mimics an encounter with a higher-ranking individual, such that female subjects potentially find themselves in a conflict between responding towards danger and mate choice – which would result in the balancing of their looking preferences between the two male stimuli.

Age also influenced subjects' looking behavior. Younger adults inspected the image pairs for longer than did older animals (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures 4), a result consistent with previous studies showing that younger animals attend for longer in looking time tasks [29] and are often more interested in novel objects than older ones are (e.g., [36–38]). There was also a nonsignificant trend for an age-related change in visual orienting decisions, with younger animals exhibiting a bias toward non-kin pictures whilst older ones attended more to kin images (LRT: χ2=3.220, df=1, p=0.073, Table 1). It is possible that this change reflects a shift in kin-detection abilities due to neural maturation and/or experience. For example, human children can detect kinship between third parties by the age of five, but this ability continues to improve up to puberty [39]. However we expect such an effect to be relatively less pronounced in our data, given that all subjects in the study were at least 3.6 years old, an age when both sexes in rhesus are sexually mature [40].

In summary, our study provides the first evidence that phenotype matching via visual cues is used in detecting one's own paternal kin under natural conditions, in any primate. This does not rule out familiarity as a mechanism to establish a kin template, as phenotype matching may be supplemented by information obtained via other routes, for example by comparing the face of an unknown individual with that of one already identified as a relative via postnatal association or self-resemblance in odor. The challenge for the future is to adopt a multimodal approach, merging our knowledge on the use of visual, acoustic and olfactory cues. The priority will be to determine in which contexts non-human primates may use these cues, and whether they derive fitness benefits from doing so.

Experimental Procedures

Study Site and Subjects

We conducted the study on Cayo Santiago, a 15.2 ha island (18°9' N, 65°44' W) [41] home to approximately 1000 rhesus macaques that, at the time of study (Sept.–Dec. 2011), comprised 6 naturally formed social groups. Information on date of birth, natal group and duration of group membership of all animals are available from the demographic dataset of the Caribbean Primate Research Center (CPRC). All individuals are well-habituated to the presence of humans, and are individually identifiable via tattoos and ear notches. All the individuals tested or serving as facial stimuli were sexually mature, ranging between 3.6 to 13.8 years in age (mean±SD: 6.7±2.3). We tested 45 males and 43 females, drawn from all social groups. Of these, 47 were also photographed and used in trials of other subjects, while a further 42 animals served solely as stimuli.

Image Collection and Preparation

We collected frontal, color digital facial images of rhesus macaques in the study population (for details see Supplemental Experimental Procedures 1).

Determination of Kinship

Pedigrees up to the grandparental generation were used to generate triads consisting of a test subject, a paternal half-sibling (referred to as the 'kin' condition) and an unrelated individual ('non-kin' condition). Paternal siblings were defined as dyads that shared a father, but had different mothers and maternal grandparents (r =0.25), while non-kin were defined as individuals that shared no ancestors in common, up to and including the grandparental generation (r ≤0.063). For specifics on parentage assignments see Supplemental Experimental Procedures 2.

Experimental Protocol

We presented the stimuli on a black foam-board (152×32 cm; LxH) with a removable green screen (39.5×21.5 cm) fixed at each end, occluding two DIN A4-size facial photographs (Figure 2). The experiment involved a 2×2 between-subjects design, in which male and female subjects were each presented with a single pair of stimuli, of either the same- or the opposite-sex as themselves. In each case, one image was a paternal half-sibling of the test animal whilst the other was of an unrelated individual of the same sex and age (mean age disparity=0.85 years). The test subject was unfamiliar with both individuals used as stimuli in its trial, defined as the subject never having co-resided in the same social group as these individuals (based on CPRC lifetime census data). Each subject was tested in only one of the two experimental conditions (same sex vs. different sex) and viewed a unique pair of kin and non-kin photographs, the location of which (L-R) was counterbalanced across subjects. A total of 88 trials were completed (N=male-male: 23, male-female: 22, female-female: 21, female-male: 22). More details on the experimental procedure and analysis can be found in Supplemental Experimental Procedures 3.

Figure 2.

The experimental apparatus in the field. The presenter simultaneously lifted the two occluders, revealing images of an unfamiliar paternal half-sibling of the subject and an unfamiliar non-relative. The camera-person is positioned behind the presenter, video-recording the behavior of the subject (not pictured).

Statistical Analyses

To analyze whether the proportion of frames in which subjects looked towards the kin vs. non-kin image depended upon subject sex, sex of the images, subject age (in days), or the interaction of these three predictors, we ran a linear mixed model with Gaussian error structure and identity link-function. In addition, the side (L-R) on which the kin picture was presented was included as a fixed effects, and the identity of the individuals shown on the specific images incorporated as a random effects. The model was weighted for each individual's total time spent looking towards the image pair and fitted in R v.2.14.1 [42] using the function ‘lmer’ provided by the library 'lme4' [43]. More details on the statistical procedures applied are given in Supplemental Experimental Procedures 4.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

- Macaques spontaneously detect their unfamiliar paternal relatives using facial cues

- Visual phenotype matching is supported as a mechanism underlying kin recognition

- Looking time towards kin is influenced by sex of both the subject and images viewed

Acknowledgements

We thank the CPRC, especially the census takers E. Davila, J. Resto, G. Caraballo-Cruz and N. Rivera-Barreto for their support and collection of demographic data and DNA samples, as well as E. Maldonado for database management. We are grateful to F. Bercovitch, M. Kessler, J. Berard, M. Krawczak, P. Nürnberg and J. Schmidtke for initiating the genetic database, and M. Krawczak and O. Junge for access to the genetic data management program FINDSIRE. L. Vigilant kindly provided laboratory access, and L. Muniz and S. Bley greatly improved the genetic database. Special credit goes to S. Winters and I. Bürgener for conducting field trials, and A. Eckhardt for scoring videos. We thank R. Mundry, N.J. Dingemanse and L. Kulik for discussion and statistical advice, R. Mundry for comments on the manuscript, J. Pfefferle for providing photographic equipment, and L. Santos for sharing expertise in conducting cognitive field experiments. We thank the Max-Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology for logistic support, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the manuscript. This project was funded by the German Science Foundation (DFG; grants PF 659/3-1 and WI 1808/5-1 to DP and AW, respectively) and conducted within the Emmy-Noether Group of 'Primate Kin Selection' (WI 1808/3-1 to AW). Research procedures were approved by the CPRC and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol no. 4060105). The rhesus population is currently supported by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR; grant 8P40OD012217) and the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (ORIP) of the National Institute of Health. The content of the publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or ORIP.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental Information

Supplemental Information can be found with this article online and includes a data file containing necessary information to run the linear mixed model and Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

References

- 1.Maloney LT, Dal Martello MF. Kin recognition and the perceived facial similarity of children. J. Vis. 2006;6:1047–1056. doi: 10.1167/6.10.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeBruine LM, Smith FG, Jones BC, Craig Roberts S, Petrie M, Spector TD. Kin recognition signals in adult faces. Vision Res. 2009;49:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bressan P, Dal Martello MF. Talis pater, talis filius: perceived resemblance and the belief in genetic relatedness. Psychol. Sci. 2002;13:213–218. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaminski G, Dridi S, Graff C, Gentaz E. Human ability to detect kinship in strangers’ faces: effects of the degree of relatedness. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2009;276:3193–3200. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vokey JR, Rendall D, Tangen JM, Parr LA, de Waal FBM. Visual kin recognition and family resemblance in chimpanzees. J. Comp. Psychol. 2004;118:194–199. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.118.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvergne A, Huchard E, Caillaud D, Charpentier MJE, Setchell JM, Ruppli C, Fejan D, Martinez L, Cowlishaw G, Raymond M. Human ability to recognize kin visually within primates. Int. J. Primatol. 2009;30:199–210. doi: 10.1007/s10764-009-9339-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kazem AJN, Widdig A. Visual phenotype matching: cues to paternity are present in rhesus macaque faces. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Widdig A, Nürnberg P, Krawczak M, Streich WJ, Bercovitch FB. Paternal relatedness and age proximity regulate social relationships among adult female rhesus macaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:13769–13773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241210198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith KL, Alberts SC, Altmann J. Wild female baboons bias their social behaviour towards paternal half-sisters. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2003;270:503–510. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silk JB, Altmann J, Alberts SC. Social relationships among female baboons (Papio cynocephalus) I. Variation in the strength of social bonds. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2006;61:183–195. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charpentier MJE, Peignot P, Hossaert-Mckey M, Wickings EJ. Kin discrimination in juvenile mandrills, Mandrillus sphinx. Anim. Behav. 2007;73:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchan JC, Alberts SC, Silk JB, Altmann J. True paternal care in a multi-male primate society. Nature. 2003;425:179–181. doi: 10.1038/nature01866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langos D, Kulik L, Mundry R, Widdig A. The impact of paternity on male–infant association in a primate with low paternity certainty. Mol. Ecol. 2013;22:3638–3651. doi: 10.1111/mec.12328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfefferle D, Ruiz-Lambides AV, Widdig A. Female rhesus macaques discriminate unfamiliar paternal sisters in playback experiments - support for acoustic phenotype matching. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2014;281:20131628. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widdig A. Paternal kin discrimination: the evidence and likely mechanisms. Biol. Rev. 2007;82:319–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walters JR. Kin recognition in non-human primates. In: Fletcher DJC, Michener CD, editors. Kin recognition in animals. John Wiley and Sons; Chichester: 1987. pp. 359–393. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang-Martinez Z. The mechanisms of kin discrimination and the evolution of kin recognition in vertebrates: A critical re-evaluation. Behav. Processes. 2001;53:21–40. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(00)00148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charpentier MJE, Crawford JC, Boulet M, Drea CM. Message “scent”: lemurs detect the genetic relatedness and quality of conspecifics via olfactory cues. Anim. Behav. 2010;80:101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parr LA, Heintz M, Lonsdorf E, Wroblewski E. Visual kin recognition in nonhuman primates: (Pan troglodytes and Macaca mulatta): inbreeding avoidance or male distinctiveness? J. Comp. Psychol. 2010;124:343–350. doi: 10.1037/a0020545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langlois JH, Roggman LA, Casey RJ, Ritter JM, Rieser-Danner LA, Jenkins VY. Infant preferences for attractive faces: rudiments of a stereotype? Dev. Psychol. 1987;23:363–369. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fantz RL. A method for studying early visual development. Percept. Mot. Skills. 1956;6:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waitt C, Little AC, Wolfensohn S, Honess P, Brown AP, Buchanan-Smith HM, Perrett DI. Evidence from rhesus macaques suggests that male coloration plays a role in female primate mate choice. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2003;270:144–146. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schell A, Rieck K, Schell K, Hammerschmidt K, Fischer J. Adult but not juvenile Barbary macaques spontaneously recognize group members from pictures. Anim. Cogn. 2011;14:503–509. doi: 10.1007/s10071-011-0383-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Penn DJ, Frommen JG. Kin recognition: an overview of conceptual issues, mechanisms and evolutionary theory. In: Kappeler P, editor. Animal Behaviour: Evolution and Mechanisms. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2010. pp. 55–85. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thierry B, Singh M, Kaumanns W, editors. A model for the study of social organization. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2004. Macaque societies. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Widdig A. The Impact of male reproductive skew on kin structure and sociality in multi-male groups. Evol. Anthropol. 2013;22:239–250. doi: 10.1002/evan.21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostner J, Nunn CL, Schülke O. Female reproductive synchrony predicts skewed paternity across primates. Behav Ecol. 2008;19:1150–1158. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arn093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bower S, Suomi SJ, Paukner A. Evidence for kinship information contained in the rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) face. J. Comp. Psychol. 2012;126:319–323. doi: 10.1037/a0025081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bethell EJ, Holmes A, MacLarnon A, Semple S. Evidence that emotion mediates social attention in rhesus macaques. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychol. Bull. 2007;133:1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silk JB. Kin selection in primate groups. Int. J. Primatol. 2002;23:849–875. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szulkin M, Stopher KV, Pemberton JM, Reid JM. Inbreeding avoidance, tolerance, or preference in animals? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013;28:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thornhill R. Cryptic female choice and its implications in the scorpionfly Harpobittacus nigriceps. Am. Nat. 1983;122:765–788. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehmann L, Perrin N. Inbreeding avoidance through kin recognition: choosy females boost male dispersal. Am. Nat. 2003;162:638–652. doi: 10.1086/378823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorusso L, Brelstaff G, Brodo L, Lagorio A, Grosso E. Visual judgments of kinship: an alternative perspective. Percept. Lond. 2011;40:1282. doi: 10.1068/p6916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bergman TJ, Kitchen DM. Comparing responses to novel objects in wild baboons (Papio ursinus) and geladas (Theropithecus gelada). Anim. Cogn. 2009;12:63–73. doi: 10.1007/s10071-008-0171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joubert A, Vauclair J. Reaction to novel objects in a troop of Guinea baboons: Approach and manipulation. Behaviour. 1986;96:92–104. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menzel EW., Jr Responsiveness to objects in free-ranging Japanese monkeys. Behaviour. 1966:130–150. doi: 10.1163/156853966x00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaminski G, Gentaz E, Mazens K. Development of children's ability to detect kinship through facial resemblance. Anim. Cogn. 2012;15:421–427. doi: 10.1007/s10071-011-0461-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bercovitch FB, Widdig A, Trefilov A, Kessler MJ, Berard JD, Schmidtke J, Nurnberg P, Krawczak M. A longitudinal study of age-specific reproductive output and body condition among male rhesus macaques, Macaca mulatta. Naturwissenschaften. 2003;90:309–312. doi: 10.1007/s00114-003-0436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rawlins RG, Kessler MJ, editors. History, behavior and biology Illustrated edition. State University of New York Press; Albany: 1986. The Cayo Santiago macaques. [Google Scholar]

- 42.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. Available at: http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. 2011 Available at: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.