Abstract

PPE68 (Rv3873), a major antignic protein encoded by Mycobacteriun tuberculosis-specific genomic region of difference (RD)1, is a strong stimulator of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained from tuberculosis patients and Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG)-vaccianted healthy subjects in T helper (Th)1 cell assays, i.e. antigen-induced proliferation and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) secretion. To confirm the antigen-specific recognition of PPE68 by T cells in IFN-γ assays, antigen-induced human T-cell lines were established from PBMCs of M. Bovis BCG-vaccinated and HLA-heterogeneous healthy subjects and tested with peptide pools of RD1 proteins. The results showed that PPE68 was recognized by antigen-specific T-cell lines from HLA-heteregeneous subjects. To further identify the immunodominant and HLA-promiscuous Th1-1 cell epitopes present in PPE68, 24 synthetic peptides covering the sequence of PPE68 were indivdually analyzed for HLA-DR binding prediction analysis and tested with PBMCs from M. bovis BCG-vaccinated and HLA-heterogeuous healthy subjects in IFN-γ assays. The results identified the peptide P9, i.e. aa 121-VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145, as an immunodominant and HLA-DR promiscuous peptide of PPE68. Furthermore, by using deletion peptides, the immunodominant and HLA-DR promiscuous core sequence was mapped to aa 127-FFGINTIPIA-136. Interestingly, the core sequence is present in several PPE proteins of M. tuberculosis, and conserved in all sequenced strains/species of M. tuberculosis and M. tuberculosis complex, and several other pathogenic mycobacterial species, including M. leprae and M. avium-intracellulalae complex. These results suggest that the peptide aa 121–145 may be exploited as a peptide-based vaccine candidate against tuberculosis and other mycobacterial diseases.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a major infectious diseases problem of world-wide distribution and ranks among the top 10 causes of global mortality. In spite of international efforts to control TB, the most recent estimates available for global epidemiology from the World Health Organization suggest that there were 9.4 million incidence cases and 14 million prevalence cases of active disease and 1.7 million people died of TB in 2009 [1]. The impact of current efforts to reduce the global burden of TB, by means of improved diagnosis and chemotherapy, is less than expected [2]. Therefore, additional preventive efforts, which include the development of new protective vaccines against TB, are essential [2].

Previous studies have shown that interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), a cytokine secreted by T helper (Th)1 cells in large quantities, is a major player in protection against TB [3]–[6]. In addition, mycobacterial antigens/peptides are presented to Th1 cells mostly in association with highly polymorphic human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules, in particular HLA-DR [6]–[8]. Thus, to be effective in human populations, which are highly HLA-DR heterogeneous, the antigens/peptides selected as anti-TB vaccine candidates should be recognized by Th1 cells in HLA-DR-non-restricted (promiscuous) manner [9].

The comparative analyses of M. tuberculosis genome has shown the presence of several regions of difference (RD) between M. tuberculosis and other mycobacteria, particularly when compared with the vaccine strains of M. bovis BCG [10]. Among these regions, RD1 appears to be the most important region for Th1-cell stimulation because it contains genes that encode two major antigenic proteins of M. tuberculosis (ESAT-6 and CFP10), which were recognized by TB patients and latently infected individuals in IFN-γ assays [11]–[13]. However, the RD1 region has been predicted to contain genes that encode 14 M. tuberculosis-specific proteins [14]. By using pools of chemically synthesized peptides corresponding to each RD1 protein, it has been shown that all of these proteins were recognized by Th 1 cells from TB patients, and three of them (ESAT-6, CFP10 and PPE68) were identified as the major antigens [15]. However, PPE68, was recognized equally well by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained from TB patients and M. bovis BCG vaccinated healthy subjects, and its presentation to Th1 cells was HLA-promiscuous [15]. The aim of this study was to confirm the recognition of PPE68 by Th1 cells using antigen-induced T-cell lines from M. bovis BCG-vaccinated and HLA-heterogeneous healthy subjects. In addition, the HLA-promiscuous regions of PPE68 were identified by HLA-binding prediction analysis in silico, and the experimental verification was performed using overlapping synthetic peptides of PPE68 and PBMCs from M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects in IFN-γ assays. Furthermore, the core sequence of the immunodominant peptide was identified by using deletion peptides in IFN-γ assays, and its cross-reactive nature was confirmed by demonstrating the presence in other mycobacterial species by sequence homology search.

Materials and Methods

Mycobacterial antigens and peptides

The mycobacterial antigen used in this study was irradiated whole-cell M. tuberculosis H37Ra [16]. A total of 220 peptides (25-mers, overlapping by 10 residues) corresponding to 12 proteins of RD1 (Rv3871, PE35, ORF4, PPE68, CFP10, ESAT-6, ORF8, Rv3876, Rv3877, Rv3878, ORF14 and OR15) were designed based on the amino acid sequence deduced from the nucleotide sequence of the predicted genes [17]–[19]. All of the peptides were synthesized by Thermo Hybaid GmBH (Ulm, Germany) using fluonerylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry, and used as described previously [20]. In brief, the stock concentrations (5 mg/ml) of the peptides were prepared in normal saline (0.9%) by vigorous pipetting and frozen at −70°C until used. The working concentrations of each peptide were prepared by further dilution in the tissue culture medium RPM1640. A pool of all 220 peptides (RD1pool), and pools of peptides of individual proteins were used in cell cultures to represent RD1 and single proteins, respectively.

Study subjects

The study subjects were M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy adults randomly selected from the group of blood donors at the Central Blood Bank, Kuwait. All of the donors were immunized with BCG vaccine following routine immunization protocol applied in Kuwait, i.e. The first immunization was given at 4 ½ years of age, followed by M. tuberculosis purified protein derivative (PPD)-skin test at 13 years of age, and a booster immunization with BCG in PPD-skin test negative subjects. At the time of inclusion in the study, all the donors were PPD-skin test positive (>10 mm, as determined with tuberculin PPD RT 23 from the Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark). Written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects to participate in the study, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University, Kuwait.

Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects and in vitro culture for IFN-γ secretion

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from the buffy coats of each donor by density centrifugation according to standard procedures [20]. In brief, each buffy coat was diluted with warm tissue culture medium (RPMI 1640) at a ratio of 1∶2 and gently mixed. Two volumes of the diluted buffy coat was loaded on top of 1 volume of a Lymphoprep gradient (Pharmacia Biotech., Uppsala, Sweden). After centrifugation, the white ring of PBMCs between the plasma and the Lymphoprep was removed and washed three times with RPMI 1640. The cells were finally suspended in 1 ml complete tissue culture medium [RPMI-1640+10% human AB serum+penicillin (100 U/ml)+streptomycin (100 µg/ml+gentamycin (40 µg/ml)], tested for viability (>98% viable by trypan blue exclusion assay) and counted in a Coulter Counter (Coulter Electronics Ltd., Luton, Bedfordshire, England), as described previously [21].

The antigen-induced secretion of IFN-γ by PBMCs was performed using standard procedures, as described previously [21]–[23]. In brief, PBMCs (2×105 cells/well) suspended in 50 µl complete tissue culture medium were seeded into 96-well tissue culture plates (Nunc Roskilde, Denmark). Antigen/peptide in 50 µl of complete medium was added to the wells in triplicate to a final concentration of 5 µg/ml. The final volume of the culture in the wells was adjusted to 200 µl. The plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. On day 6, supernatants (100 µl) were collected from antigen-stimulated cultures of PBMCs and were kept frozen at −70°C until assayed for IFN-γ activity. The amount of IFN-γ in the supernatants was quantitated by using Immunotech immunoassay kits (Immunotech SAS, Marseille, France) as specified by the manufacturer. The detection limit of the IFN-γ assay kit was 0.4 IU/ml. Secretion of IFN-γ in response to a given antigen or peptide was considered positive when delta IFN-γ (the IFN-γ concentration in cultures stimulated with antigen/peptide minus the IFN-γ concentration in cultures without antigen/peptide) was ≥3 U/ml [17]. The IFN-γ responses were considered strong with median IFN-γ≥5 U/ml and %positives ≥70%, moderate with median IFN-γ >3 to <5 U/ml and %positives ≥50%, to <70%, and weak with median IFN-γ ≤3 U/ml and %positives <50% [17]. The statistical analysis was performed using Z test to identify significant differences (P<0.05) with respect to % positives in response to peptide pool of PPE68 and the individual peptides.

HLA typing of PBMCs

Genomic HLA-DR and DQ typing of PBMCs were performed by using sequence specific primers (SSP) in polymerase chain reaction (PCR), as described previously [23]–[25]. HLA-DR “low resolution” kits containing the primers to type for DRB1, DRB3, DRB4 and DRB5 alleles were purchased form Dynal AS (Oslo, Norway) and used according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, high molecular weight genomic DNA from PBMCs were isolated by treatment of the cells with proteinase-K and salting out in mini scale. For DR “low resolution” PCR-SSP typing, 21 separate PCR reactions were performed per sample; 17 for assigning DR1 to DRw18 alleles of DRB1 and three for identifying the HLA-DR51, -DR52 and -DR53 super-specificities encoded by DRB3, DRB4 and DRB5, respectively. The genotypes were identified from the size of the amplified products and serologically defined HLA-DR (DR1 to DR18) specificities were determined from the genotypes by following the guidelines provided by Dynal AS.

Establishing antigen-reactive T-cell lines

Antigen-specific T-cell lines were established from PBMCs by stimulation with the peptide pools of RD1 and PPE68 according to standard procedures [23]–[25]. In brief, 2×105 cells/well were stimulated with 5 µg/ml of peptides in 96 well plates and incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air for 6 days. Starting from day 6, IL-2 (100 U/well) (Amersham Life Sciences, Amersham, U.K.) was added twice a week until the cell number was sufficient to be transferred to 24 well tissue culture plates (Nunc Roskilde, Denmark). The T-cell lines were maintained in 24 well plates with twice a week addition of IL-2 and tested for antigen reactivity 3–4 days after the last addition of IL-2. The T-cell lines were phenotyped for the expression of CD4 and CD8 molecules using standard procedures [26].

IFN-γ secretion by T-cell lines

The T-cell lines were tested for antigen-induced IFN-γ secretion in the wells of 96-well tissue culture plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) in the presence of autologous and allogeneic HLA-typed antigen presenting cells (APCs), as described previously [23], [25]. In brief, adherent cells obtained from irradiated (24 Grays) PBMCs (seeded into the wells of 96-well plates at 1×105 cells/well) were used as APCs. The T-cell lines were added to the wells at a concentration of 5×104 cells/well. Peptides were added in triplicate at a final concentration of 5 µg/ml, and the control wells lacked the peptides. The plates were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. After 3 days of incubation, the culture supernatants were collected and assayed for IFN-γ concentrations using immunoassay kits (Coulter/Immunotech, S.A., Marseille, France), as described above for PBMCs. The secretion of IFN-γ in response to a given antigen was considered positive with IFN-γ concentration ≥5 IU/ml [25].

HLA-DR binding prediction analysis of PPE68 and its peptides

HLA-DR binding prediction analysis of PPE68 and the sequence of each peptide was first performed using the ProPred server (http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/propred/) at threshold value of 3, as described previously [27]. This server is a useful tool in locating the promiscuous binding regions that can bind to a total of 51 alleles belonging to nine serologically defined HLA-DR molecules [27]–[29]. These HLA-DR molecules are encoded by DRB1 and DRB5 genes including HLA-DR1 (2 alleles), DR3 (7 alleles), DR4 (9 alleles), DR7 (2 alleles), DR8 (6 alleles), DR11 (9 alleles), DR13 (11 alleles), DR15 (3 alleles) and DR51 (2 alleles). The peptides of PPE68 predicted to bind >50% HLA-DR alleles included in the ProPred were considered promiscuous for binding [30].

In addition, ProPred-predicted four HLA-promiscuous and four HLA-non-binder peptides were further analyzed for HLA-DR binding predictions using two other computational prediction methods, i.e. NetMHCIIpan-2.0 [31], and Immuno Epitope Data Base (IEDB) Consensus [32], for binding to 14 alleles, including HLA DRB1*0101, DRB1*0301, DRB1*0401, DRB1*0701, DRB1*1101 and DRB1*1501 supertype alleles that are expected to cover approximately >95% of any given human population [33]. The sequences/peptides predicted to bind >50% alleles of HLA-DR molecules analyzed were considered promiscuous for binding [30].

Search for sequence identity

The complete PPE68 sequence and the immunodominant and HLA-promiscuous peptide sequence (121-VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145) were searched for identical sequences in various strains of M. tuberculosis and mycobacterial species using Protein Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST), National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, using the world wide web (WWW) server.

Results

Antigen-specific IFN-γ secretion by human T-cell lines

T-cell lines were established from HLA-heterogeneous donors by stimulating PBMCs with the RD1pool (n = 4 donors, Table 1) and PPE68 (n = 3 donors, Table 2), as the primary antigens in vitro. Phenotypic analysis showed that all of these T-cell lines belonged to the CD4+, CD8− subset of T cells. Subsequent testing for antigen-induced IFN-γ secretion demonstrated that all of the four RD1-induced T-cell lines responded to whole-cell M. tuberculosis and three of them responded to RD1pool (Table 1). When tested with the peptide pools of individual proteins of RD1, only PPE68 induced positive responses in all of the three T-cell lines responding to RD1pool (Table 1), whereas, only one T-cell line responded to 10 of the 12 ORFs of RD1 (Table 1). The IFN-γ responses of three T-cell lines established against PPE68 were also tested with whole-cell M. tuberculosis, PPE68 and peptide pools of some other RD1 proteins, and the results showed that all of these T-cell lines responded to whole-cell M. tuberculosis and PPE68, but not to other RD1 proteins (Table 2).

Table 1. IFN-γ secretion by RD1-induced T-cell lines from HLA-heterogeneous subjects in response to whole cell M. tuberculosis, RD1pool and various ORFs of RD1.

| Antigen/Peptides | Concentrations of IFN-γ (IU/ml) in culture supernatants of T-celllines with HLA-type | |||

| DR7,10,53 | DR7,13,52,53 | DR11,13,52 | DR3,11,52 | |

| M. tuberculosis | 54 | 57 | 44 | 15 |

| RD1pool | 63 | 37 | 26 | 0.7 |

| Rv3871 | <0.4 | <0.4 | 1.1 | <0.4 |

| PE35 | 22 | 1.0 | 1.4 | <0.4 |

| ORF4 | 1.0 | <0.4 | 0.5 | <0.4 |

| PPE68 | 57 | 44 | 38 | <0.4 |

| CFP10 | 40 | 0.7 | 3.0 | <0.4 |

| ESAT-6 | 71 | 2.7 | 3.0 | <0.4 |

| ORF8 | 54 | 1.0 | 2.3 | <0.4 |

| Rv3876 | 69 | 1.8 | 2.6 | <0.4 |

| Rv3877 | 67 | 0.4 | 1.1 | <0.4 |

| Rv3878 | 41 | <0.4 | 1.0 | <0.4 |

| ORF14 | 28 | <0.4 | 0.7 | <0.4 |

| ORF15 | 29 | <0.4 | 0.4 | <0.4 |

The T-cell lines were established after stimulation of PBMCS with RD1pool and tested for antigen reactivity in IFN-γ assays, as described in the materials and methods. The positive responses (IFN-γ concentration ≥5 U/ml) are given in bold face.

Table 2. IFN-γ secretion by PPE68-induced T-cell lines from HLA-heterogeneous subjects in response to whole cell M. tuberculosis and various ORFs of RD1.

| Antigen/Peptides | Concentrations of IFN-γ (IU/ml) in culture supernatants of T-celllines with HLA-type | ||

| DR1,11,52 | DR2,5,51,52 | DR4,7,53 | |

| M. tuberculosis | 26 | 26 | 30 |

| PPE68 | 27 | 26 | 12 |

| ORF4 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| CFP10 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 1.7 |

| ORF8 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.5 |

| Rv3877 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 0.9 |

The T-cell lines were established after stimulation of PBMCS with the peptide pool of PPE68 and tested for antigen reactivity in IFN-γ assays, as described in the materials and methods. The positive responses (IFN-γ ≥5 IU/ml) are given in bold face.

Identification of immunodominant and HLA-promiscuous peptide(s) of PPE68

To identify the peptides of PPE68 recognized by Th1-type cells, individual peptides of PPE68 were tested with PBMCs from 30 M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects in IFN-γ assays. The results showed that all of the peptides induced positive responses in a proportion of donors, which ranged from 30% to 70% (Table 3). However, the best responses were observed with peptide P9 (121- VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145), which induced positive responses in 21/30 (70%) subjects. In terms of % positives, the response induced by P9 (121–145) was comparable to the response induced by the full-length PPE68 protein (1–371) with 22/30 (73%) subjects showing positive response (Table 3). Except P9 (21–145), none of the other peptides of PPE68 qualified to be strong stimulator of Th1-type cells, because the IFN-γ responses to them were either moderate (P1, P2, P4, P8, P11, P12, P13, P14, P17, P18, P20, P21) or weak (P3, P5, P6, P7, P10, P15, P16, P19, P22, P23 and P24) (Table 3). These results suggest that, for Th1-type cell-reactivity, only P9 (121–145) was the immunodominant peptide of PPE68.

Table 3. Antigen-induced IFN-γ secretion by PBMCs from 30 M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects and ProPred predictions for PPE68 and its peptides (P1 to P24) to bind 51 HLA-DR alleles.

| Peptide | IFN-γ responsea | HLA-DR bindingb | |||

| Median IU/ml | P/T | % positive | P/T | % binding | |

| PPE68 (1–371) | 22 | 22/30 | 73% | 50/51 | 98 |

| P1 (1-VITMLWHAMPPELNTARLMAGAGPA-25) | 3.6 | 16/30 | 53% | 1/51 | 2 |

| P2 (16-ARLMAGAGPAPMLAAAAGWQTLSAA-40) | 4.3 | 16/30 | 53% | 6/51 | 12 |

| P3 (31-AAGWQTLSAALDAQAVELTARLNSL-55) | 1.2 | 10/30 | 33% | 22/51 | 43 |

| P4 (46-VELTARLNSLGEAWTGGGSDKALAA-70) | 3.5 | 16/30 | 53% | 0/51 | 0 |

| P5 (61-GGGSDKALAAATPMVVWLQTASTQA-85) | 2.3 | 12/30 | 40% | 35/51 | 69 |

| P6 (76-VWLQTASTQAKTRAMQATAQAAAYT-100) | 1.6 | 13/30 | 43% | 9/51 | 18 |

| P7 (91-QATAQAAAYTQAMATTPSLPEIAAN-115) | 2.6 | 14/30 | 47% | 0/51 | 0 |

| P8 (106-TPSLPEIAANHITQAVLTATNFFGI-130) | 3.2 | 16/30 | 53% | 3/51 | 6 |

| P9 (121-VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145) | 7.9 | 21/30 | 70% | 33/51 | 65 |

| P10 (136-ALTEMDYFIRMWNQAALAMEVYQAE-160) | 2.7 | 14/30 | 47% | 38/51 | 75 |

| P11 (151-ALAMEVYQAETAVNTLFEKLEPMAS-175) | 3.5 | 15/30 | 50% | 24/51 | 47 |

| P12 (166-LFEKLEPMASILDPGASQSTTNPIF-190) | 3.5 | 15/30 | 50% | 24/51 | 47 |

| P13 (181-ASQSTTNPIFGMPSPGSSTPVGQLP-205) | 4.6 | 17/30 | 57% | 23/51 | 45 |

| P14 (196-GSSTPVGQLPPAATQTLGQLGEMSG-220) | 4.6 | 17/30 | 57% | 2/51 | 4 |

| P15 (211-TLGQLGEMSGPMQQLTQPLQQVTSL-235) | 1.9 | 13/30 | 43% | 6/51 | 12 |

| P16 (226-TQPLQQVTSLFSQVGGTGGGNPADE-250) | 1.5 | 12/30 | 40% | 23/51 | 45 |

| P17 (241-GTGGGNPADEEAAQMGLLGTSPLSN-265) | 3.7 | 17/30 | 57% | 11/51 | 22 |

| P18 (256-GLLGTSPLSNHPLAGGSGPSAGAGL-280) | 3.5 | 15/30 | 50% | 0/51 | 0 |

| P19 (271-GSGPSAGAGLLRAESLPGAGGSLTR-295) | 1.8 | 14/30 | 47% | 16/51 | 31 |

| P20 (286-LPGAGGSLTRTPLMSQLIEKPVAPS-310) | 4.2 | 16/30 | 53% | 19/51 | 37 |

| P21 (301-QLIEKPVAPSVMPAAAAGSSATGGA-325) | 4.1 | 15/30 | 50% | 29/51 | 57 |

| P22 (316-AAGSSATGGAAPVGAGAMGQGAQSG-340) | 0.8 | 10/30 | 33% | 0/51 | 0 |

| P23 (331-GAMGQGAQSGGSTRPGLVAPAPLAQ-355) | 0.7 | 9/30 | 30% | 18/51 | 35 |

| P24 (346-GLVAPAPLAQEREEDDEDDWDEEDDW-371) | 1.4 | 11/30 | 37% | 0/51 | 0 |

IFN-γ responses were evaluated by stimulating PBMCs with the peptides of PPE68 according to procedures described in materials and methods. The strong responses (Median concentration >5 U/ml and %positive≥70%) are given in bold face.

HLA-DR binding predictions for complete PPE68 sequence and its individual peptides were analyzed using the ProPred server (http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/propred/). The % binding values suggesting promiscuous HLA-DR binding (binding to >50% HLA-DR alleles) are shown in bold face.

P/T = Number of subjects positive/Number of subjects tested.

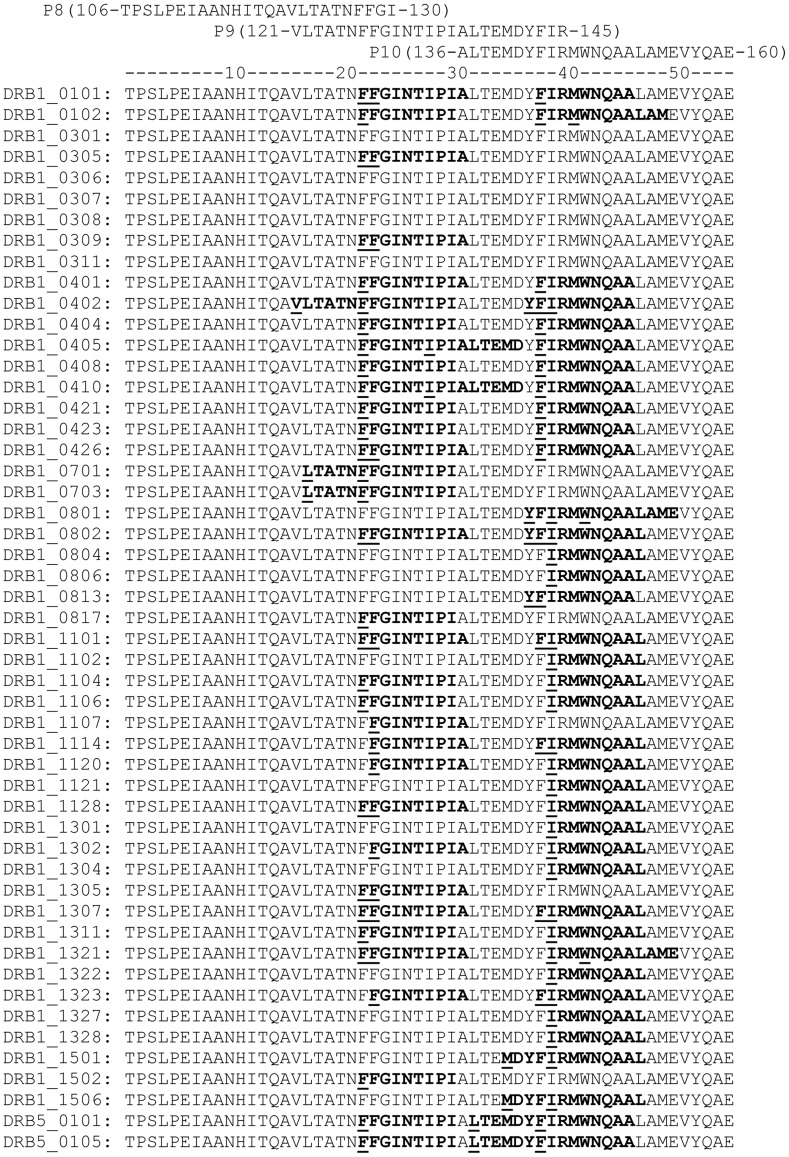

In addition to the functional assay for Th1-type cell reactivity, the sequences of PPE68 and its individual peptides were also analyzed for the presence of T-cell epitopes by predicting to bind HLA-DR molecules using the ProPred server. Because the complete PPE68 sequence (1–371) is too large, therefore, binding prediction for all of its peptides to 51 HLA-DR alleles included in ProPred, cannot be presented in a figure or a table. Instead, the summary of HLA-DR binding results are presented in table 3. However, to provide an idea of HLA-DR binding predictions, the prediction results for a small region (106 to 160 covering peptides P8, P9 and P10) to individual HLA-DR alleles, included in ProPred, are shown in fig. 1.

Figure 1. ProPred analysis of a part of PPE68 sequence (106–160) using the ProPred server (http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/propred/) covering three overlapping peptides (P8, P9 and P10) to 51 HLA-DR alleles.

The output of ProPred analysis of PPE68 sequence (aa 106–160) for binding to 51 HLA-DR alleles at the default setting (threshold value of 3) is shown in HTML II view. The sequences predicted to bind HLA-DR alleles are underlined. The obligatory anchor (starting) residues are marked in bold.

The overall results of ProPred analysis suggest that PPE68 was a promiscuous HLA-DR binder and T-cell epitopes were scattered throughout the sequence of PPE68 (Table 3). In total, 50/51 (98%) of HLA-DR specificities included in ProPred were predicted to bind PPE68 sequence and 19 of 24 peptides were predicted to be HLA-DR binders (Table 3). However, five peptides of PPE68, i.e. P4, P7, P18, P22 and P24 were not predicted to have T-cell epitopes using ProPred, but the results of IFN-γ assays showed that all of them had Th1 cell-stimulating epitopes and induced moderate (P4) to weak responses (P7, P18, P22, P24) (Table 3). Furthermore, the peptides P5, P9, P10 and P21 were found HLA-promiscuous (Table 3, Fig. 1: data shown for P9 and P10), but only P9 qualified as a strong stimulator, whereas others were weak stimulators of IFN-γ secretion (Table 3). All other peptides were predicted to be non-promiscuous HLA-DR binders, and none of them were strong stimulators of Th1 cells in IFN-γ assays (Table 3).

Identification of immunodominant and HLA-promiscuous epitope of peptide P9 (121–145)

The immunodominant peptide P9 (121-VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145) of PPE68 is a 25-mer and each amino acid of this sequence contributed in binding to HLA-DR molecules included in ProPred (Fig. 1). It has got six independent sequences (each a 9-mer), which were predicted to bind one (121-VLTATNFFG-129), two (122-LTATNFFGI-130, 135-IALTEMDYF-143 and 137-LTEMDYFIR-145), 16 (128-FGINTIPIA-136) and 28 (127-FFGINTIPI-135) alleles of HLA-DR molecules included in ProPred (Fig. 1). HLA- promiscuous binding of the peptide 121–145 was also suggested by using other prediction programs for binding to HLA-DR alleles, i.e. NetMHCII 2.2, and IEDB Consensus, which predicted to bind 11/14 (79%) and 10/14 (70%) alleles of HLA-DR, respectively. Testing a series of deletion peptides of 121–145 with PBMCs of eight HLA-heterogeneous healthy subjects responding to the full-length peptide showed that the IFN-γ responses (8/8 responders) and HLA-DR binding predictions (33/51, 65%) were fully conserved for the 10-mer sequence 127-FFGINTIPIA-136 (Table 4). However, any further deletion on either side of this core peptide decreased the frequency of positive response as well as the ability to predict binding to HLA-DR alleles by ProPred (Table 4). However, variations were observed in the minimum length of peptides inducing a positive response in various donors, and even 9, 8 and 7-mer peptides, which belonged to the HLA-DR binding region but were not predicted to bind HLA-DR alleles included in the ProPred due to short length (<10 aa), could induce positive responses in PBMCs of six, five and two donors, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4. Analysis of peptide 121–145 and its deletions for prediction to bind HLA-DR alleles and secretion of IFN-γ by PBMCs from HLA-DR heterogeneous healthy subjects.

| Peptide sequence | HLA-DR binding | Antigen-induced IFN-γ (IU/ml) secretion by PBMCs of donors | P/Ta | ||||||||

| P/T | % binding | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR | 33/51 | 65 | 43 | 5.0 | 28 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 16 | 26 | 9.0 | 8/8 |

| ATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR | 33/51 | 65 | 41 | 6.0 | 16 | 5.0 | 20 | 22 | 17 | 8.0 | 8/8 |

| ATNFFGINTIPIAL | 33/51 | 65 | 45 | 17 | 19 | 5.0 | 28 | 17 | 12 | 8.0 | 8/8 |

| ATNFFGINTIPI | 38/51 | 55 | 47 | 5.1 | 9.0 | 5.0 | 24 | 14 | 16 | 10 | 8/8 |

| FFGINTIPIAL | 33/51 | 65 | 51 | 5.0 | 19 | 19 | 26 | 16 | 10 | 6.0 | 8/8 |

| FFGINTIPIA | 33/51 | 65 | 50 | 5.0 | 13 | 5.0 | 8.7 | 16 | 15 | 7.0 | 8/8 |

| FGINTIPIAL | 16/51 | 31 | 25 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 5.0 | 7/8 |

| FGINTIPIA | NAb | NA | 21 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 5.5 | 26 | 17 | 9.0 | 5.0 | 6/8 |

| GINTIPIAL | NA | NA | 0.5 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 12 | 2.0 | 1/8 |

| INTIPIAL | NA | NA | 0.5 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 1/8 |

| FFGINTIPI | NA | NA | 57 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 15 | 5.0 | 5/8 |

| FFGINTIP | NA | NA | 28 | 4.0 | 18 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 12 | 17 | 5.0 | 5/8 |

| FGINTIPI | NA | NA | 28 | 2.0 | 15 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 8.0 | 16 | 4.0 | 4/8 |

| FFGINTI | NA | NA | 0.5 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 7.0 | 2/8 |

| FGINTIP | NA | NA | 1.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 4.0 | 0/8 |

HLA types of donors 1(DR7,17,52,53; DQ2,6), 3(DR11,13,52; DQ7), 4(DR17,52; DQ2) 5(DR1,18,52;DQ4,5), 6(DR14,15,51,52; DQ5,6), 7(DR4,16,51,53;DQ5,8), 8(DR4,17,52,53;DQ2,8).

The regions of peptide 121–145 and its deletions predicted to bind HLA-DR molecules are shown in bold and the anchor sequences are underlined.

P/T = Number of positive PBMCs donors/Number of donors tested.

NA = Not applicable. This is because these sequences are <10 aa in length, which is the minimum requirement for ProPred to predict binding of peptide sequences to HLA-DR alleles [27].

A BLAST search for sequence homology with the PPE68 sequence and peptide P9 (121-VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145) in the data base of NCBI showed that PPE68 was 100% conserved in all organisms of M. tuberculosis complex, except BCG, and had 75% and 67% identities with PPE proteins of M. kansasii and M. marinum, respectively, whereas the sequence identities were <40% with PPE proteins of other mycobacteria, including BCG (data not shown). However, the sequence covering the immunodominant and HLA-promiscuous region of peptide 121–145, i.e. 127-FFGINTIPIA-136, was completely identical between proteins encoded by genes of PPE-family proteins present in several mycobacterial strains and species including M. tuberculosis complex, i.e. M. tuberculosis (>35 strains, including laboratory and drug-susceptible as we all multi-drug resistant clinical isolates), M. africanum, M. bovis, M. bovis BCG and M. canettii and non-tuberculous mycobacteria, e.g. M. avium, M. marinum, M. ulcerans, M. kansasii and M. leprae etc. (Table 5).

Table 5. BLAST search data for sequence identity of PPE68 peptide (121–145) in M. tuberculosis complex and other pathogenic mycobacteria.

| Mycobacterial species | Amino acid sequence |

| M. tuberculosis complex: | |

| M. tuberculosis(>35 species) | VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR |

| M. bovis | VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR |

| M. bovisBCG | VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR |

| M. africanum | VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR |

| M. canettii | VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR |

| Non-tuberculous mycobacteria: | |

| M. kansasii | VLVATNFFGINTIPIALTEADY--- |

| M. marinum | VLVATNFFGINTIPIALTEADY--- |

| M. ulcerans | VLVATNFFGINTIPIALTEADY--- |

| M. paraschrofulaceum | VLVATNFFGINTIPIALTEADY--- |

| M. abscessus | VLLATNFFGINTIPIALNEADY-IR |

| Mycobacterial species JDM601 | VLVATNFFGINTIPIALTEADY--- |

| M. avium | VLVATNFFGINTIPIALTEADY--- |

| M. smegmatis | VLVATNFFGINTIPIALTEADY--- |

| M. leprae | FLIATNFFGINTIPIALNEADYVR- |

The 13 aa sequence of PPE68 (aa 124–136) common to all mycobacteria is given in italics and the sequence in each mycobacterial species predicted to bind HLA-DR alleles in this region is underlined. The obligatory anchor (starting) residues for HLA-DR binding are marked in bold.

Discussion

In this study, PPE68, a major antigenic protein of M. tuberculosis was tested for inducing IFN-γ secretion by antigen-induced T-cell lines and identification of immunodominant peptide(s) by testing PBMCs from HLA-heterogeneous M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy humans. It has previously been shown that, PPE68, although belongs to the group of proteins encoded by M. tuberculosis-specific RD1 genomic segment of DNA, was recognized in Th1-cell assays (antigen-induced proliferation and IFN-γ secretion) by PBMCs from M. tuberculosis-infected and non-infected M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects [15], [34]. However, PBMCs are a mixture of various cell types present in the peripheral blood, and therefore the use of PBMCs does not conclusively rule out the recognition of PPE68 by non-T cells or the non-specific mitogenic effect of the protein. Therefore, to confirm that PPE68 was recognized by antigen-specific T cells, antigen-induced T-cell lines from HLA-heterogeneous subjects were established in this study.

Among the antigens used to establish T-cell lines were RD1pool containing peptides of 12 ORFs of RD1, and a pool consisting of the peptides of PPE68 only. Phenotypically, all of the T-cell lines were CD4+, CD8−, confirming the previous observations using similar procedures to establish T-cell lines against other antigens of M. tuberculosis [23]–[25]. Furthermore, the T-cell lines from all donors responded to whole cell M. tuberculosis suggesting their previous exposure to antigens of M. tuberculosis either through infection with M. tuberculosis and/or vaccination with M. bovis BCG. However, one of the four RD1-induced T-cell line did not respond to RD1pool. This could have been due to the low frequency or absence of RD1-reactive T cells in this cell line. The establishment of a T-cell line from this donor could have been due to the antigen non-specific stimulation of M. tuberculosis-reactive T cells by IL-2, as has been shown previously with other antigens [35]. However, all three RD1pool-reactive T-cell lines also responded to PPE68, and only one T cell line responded to nine other RD1 antigens, including ESAT-6 and CFP10 (Table 1). All of the three T-cell lines established against PPE68 responded to this antigen only (Table 2), which suggests that the responses to PPE68 were antigen-specific and not due to the activation of non-specific T cells.

The positive responses of PBMCs from healthy subjects to ESAT-6/CFP10 have been considered as indication of prior infection of donors with M. tuberculosis [36]–[38]. Thus, the positive responses of T-cell lines to PPE68, but not to other RD1 antigens, suggest that these donors were not infected with M. tuberculosis, and therefore, the positive responses to PPE68 could have been due to vaccination with BCG and/or exposure to environmental mycobacteria, as suggested previously for other crossreactive antigens of M. tuberculosis, e.g. MPT63, MPB70 and MPT83 etc. [29], [39].

To identify immunodominant epitope(s) in PPE68, two approaches were used in this study. First PBMCs from HLA-heterogeneous subjects were tested with 24 overlapping peptides covering the sequence of PPE68. A similar approach has previously been used to identify the immunodominant epitopes of other major antigenic proteins of M. tuberculosis [40]–[42]. The results showed that all of the peptides of PPE68 induced positive responses in a proportion of donors, but, the best responses were observed with peptide P9 (121- VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145). Although, T-cell epitopes were present throughout the sequence of PPE68, the percent positive response induced by P9 (121–145) was comparable to the percent positive response induced by the peptide pool of full-length PPE68 protein (1–371) (P>0.05, by Z test). This feature seems to be unique to this peptide, because none of the single peptides of other mycobacterial proteins have shown similar positivity in human Th1-cell assays, as full-length proteins [29], [39]–[44].

In addition to Th1-cell reactivity, the sequences of PPE68 and its individual peptides were analyzed for the presence of T-cell epitopes using the ProPred server, which predicts binding to molecules encoded by 51 HLA-DR alleles [27]. The ProPred analysis has previously been shown to identify immunodominant antigens and peptides of several M. tuberculosis proteins [28]–[30], [39], [40]. The overall results of ProPred analysis suggest that PPE68 was a promiscuous HLA-DR binder (Table 3). The analysis of individual peptide sequences by ProPred suggested that 19 of 24 peptides were predicted to be HLA-DR binders (Table 3). However, five peptides of PPE68, i.e. P4, P7, P18, P22 and P24 were not predicted to have T-cell epitopes by ProPred analysis, but the results of IFN-γ assays showed that all of them had T-cell epitopes and induced moderate (P4 and P18) to weak responses (P7, P22, P24) (Table 3). The discrepancy between the HLA-DR binding and the functional assay could be due to the reason that ProPred, although includes the binding prediction for a large number of HLA-DR molecules, does not include all HLA-DR specificities [27]. Alternatively, ProPred is not 100% accurate to predict the binding [28]–[30], [39], [40]. Therefore, the five non-binding and four promiscuous peptides of PPE68 were further evaluated for binding predictions using two additional servers, i.e. NetMHCII 2.2 and IEDB Consensus, which are suggested to have similar overall performance as ProPred, but differ in their binding predictions to individual HLA-DR alleles [45], [46]. The results suggested that all of the five peptides suggested to be non-binders by ProPred were binders by NetMHCII 2.2 and three of them were also predicted to bind HLA-DR alleles by IEDB Consensus method (Table 6). Furthermore, among four peptides suggested to be promiscuous binders by ProPred, only three peptides (P5, P9 and P10) were promiscuous binders by other two methods. Importantly P9 and P10 were suggested to be promiscuous binders by all three methods but only P9 was immunodominant in IFN-γ assays (Table 6). This could be due to the reason that binding of peptides to HLA-DR molecules, although essential for recognition by Th1 cells, is not sufficient for Th1-cell recognition, because the later requires the existence of cells with epitope-specific T-cell receptors, which may be lacking in some individuals.

Table 6. Comparison of binding predictions of selected peptides of PPE68 to HLA-DR alleles using various computational methods and IFN-γ responses of PBMCs from 30 healthy subjects.

| Peptide | Binding to HLA-DR alleles predicted bya | Subjects responding in IFN-γ assaysb | ||

| ProPred | NetMHCII 2.0 | IEDB Consensus | ||

| P4 (46–70) | 0/51 (0%) | 4/14 (29%) | 1/14 (7%) | 16/30 (53%) |

| P7 (91–1155) | 0/51 (0%) | 6/14 (43%) | 3/14 (21%) | 14/30 (47%) |

| P18 (256–280) | 0/51 (0%) | 4/14 (29%) | 0/14 (0%) | 15/30 (50%) |

| P22 (316–340) | 0/51 (0%) | 1/14 (7%) | 0/14 (0%) | 10/30 (33%) |

| P24 (346–371) | 0/51 (0%) | 2/14 (14%) | 1/14 (7%) | 11/30 (37%) |

| P5 (61–85) | 35/51 (69%) | 11/14 (79%) | 7/14 (50%) | 12/30 (40%) |

| P9 (121–145) | 33/51 (65%) | 11/14 (79%) | 10/14 (71%) | 21/30 (70%) |

| P10 (136–160) | 38/51 (75%) | 12/14 (86%) | 11/14 (79%) | 14/30 (47%) |

| P21 (301–325) | 29/51 (57%) | 3/14 (21%) | 3/14 (21%) | 15/30(50%) |

The results are shown as number of HLA-DR molecules predicted to bind/number of HLA-DR molecules tested for binding to a given peptide and the percentages are given in brackets.

The results are given as the number of subjects positive/the number of subjects tested with each peptide and the percentages of positi9ve responders are given in brackets.

The %binding values suggesting promiscuous HLA-DR binding (binding to >50% HLA-DR alleles) and the strong responses (Median IFN-γ concentration >5 U/ml and %positive ≥70%) are given in bold face.

The immunodominant peptide P9 (121-VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145) of PPE68 is a 25-mer and each amino acid of this sequence contributes in binding to HLA-DR molecules included in ProPred (Fig. 1). However, a 10 aa sequence, i.e. 127-FFGINTIPIA-136 retained the full capacity to stimulate Th1 cells and to bind HLA-DR molecules by ProPred (Table 4). The same sequence also retained its promiscuous character for binding to HLA-DR alleles, when analyzed by NetMHCII 2.2 and IEDB Consensus methods (data not shown). Thus, both functional as well as methods for T-cell epitope prediction unanimously confirm immunodominant nature of the sequence 127-FFGINTIPIA-136 for recognition by CD4+ Th1 cells.

A search for sequence homology with the peptide P9 sequence (121-VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145) in the data base of National Centre for Biotechnology Information, USA, using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) for comparing protein sequences, showed that a 13 aa stretch, i.e. 124-ATNFFGINTIPIA-136), was completely identical between proteins encoded by genes of other PPE-family proteins present in various mycobacterial strains and species, e.g. M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. bovis BCG, M. avium, M. marinum, M. ulcerans and M. leprae etc. (Table 5). These results suggest that the core region of the immunodominant peptide of PPE68, i.e. 127-FFGINTIPIA-136, is present in several pathogenic mycobacteria. Furthermore, the full length peptide 121–145 as well as peptide 127–136 were also suggested to possess CD8+ cytotoxic T cell epitopes using nHLAPred/Compred [47] and ProPred-I [48] (Table 7). Since the involvement of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is suggested for optimal protection against mycobacterial disease [49], [50], the use of crossreactive peptide 121-VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145 of PPE68 may be useful as a peptide-based vaccine against TB and other mycobacterial diseases.

Table 7. Binding predictions forPPE68peptides 121–145, 124–137 and 127–136 to HLA-class I alleles using the prediction methods nHLAPred/Compred and ProPred-I.

| Peptide | Binding to HLA-class I alleles predicted bya | |

| nHLAPred/Compred | ProPred-I | |

| 121-VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145 | 25/67 (37%) | 41/47(87%) |

| 124-ATNFFGINTIPIAL-137 | 15/67(22%) | 26/47(55%) |

| 127-FFGINTIPIA-136 | 4/67(6%) | 15/47(32%) |

The results are shown as no. of HLA-class I molecules predicted to bind/number of HLA-class I molecules tested for binding to a given peptide and the binding percentages are given in brackets.

Acknowledgments

The buffy coats from healthy donors were obtained from the Central Blood Bank, Kuwait, and Fatema Shaban provided technical help.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Kuwait University Research Sector grants MI01/10 and SRUL02/13. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (2010) Global Tuberculosis Control. WHO Report 2010, WHO/HTM/TB/2010.7.

- 2. Lönnroth K, Raviglione M (2008) Global epidemiology of tuberculosis: prospects for control. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 29: 481–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Al-Attiyah R, Mustafa AS, Abal AT, Madi NM, Andersen P (2003) Restoration of mycobacterial antigen-induced proliferation and interferon-gamma responses in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of tuberculosis patients upon effective chemotherapy. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 38: 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Demissie A, Abebe M, Aseffa A, Rook G, Fletcher H, et al. (2004) Healthy individuals that control a latent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis express high levels of Th1 cytokines and the IL-4 antagonist IL-4delta2. J Immunol 172: 6938–6943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walzl G, Ronacher K, Hanekom W, Scriba TJ, Zumla A (2011) Immunological biomarkers of tuberculosis. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Caccamo N, Barera A, Di Sano C, Meraviglia S, Ivanyi J, et al. (2003) Cytokine profile, HLA restriction and TCR sequence analysis of human CD4+ T clones specific for an immunodominant epitope of Mycobacterium tuberculosis 16-kDa protein. Clin Exp Immunol 133: 260–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mustafa AS (2000) HLA-restricted immune response to mycobacterial antigens: relevance to vaccine design. Human Immunol 61: 166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mustafa AS (2009) HLA-promiscuous Th1-cell reactivity of MPT64 (Rv1980c), a major secreted antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, in healthy subjects. Med Princ Pract 18: 385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mustafa AS (2009) Vaccine potential of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific genomic regions: in vitro studies in humans. Expert Rev Vaccines 8: 1309–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gordon SV, Brosch R, Billault A, Garnier T, Eiglmeier K, et al. (1999) Identification of variable regions in the genomes of tubercle bacilli using bacterial artificial chromosome arrays. Mol Microbiol 32: 643–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mustafa AS (2001) Biotechnology in the development of new vaccines and diagnostic reagents against tuberculosis. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2: 157–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lalvani A, Nagvenkar P, Udwadia Z, Pathan A A, Wilkinson K A, et al. (2001) Enumeration of T cells specific for RD1-encoded antigens suggests a high prevalence of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in healthy urban Indians. J Infect Dis 183: 469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ravn P, Munk M E, Andersen A B, Lundgren B, Lundgren J D, et al. (2005) Prospective evaluation of a whole-blood test using Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10 for diagnosis of active tuberculosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 12: 491–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Amoudy HA, Al-Turab MB, Mustafa AS (2006) Identification of transcriptionally active open reading frames within the RD1 genomic segment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Med Princ Pract 15: 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mustafa AS, Al-Attiyah R, Hanif SNM, Shaban FA (2008) Efficient testing of pools of large numbers of peptides covering 12 open reading frames of M. tuberculosis RD1 and identification of major antigens and immunodominant peptides recognized by humanTh1 cells. Clin Vaccine Immunol 15: 916–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mustafa AS, El-Shamy AM, Madi NM, Amoudy HA, Al-Attiyah R (2008) Cell-mediated immune responses to complex and single mycobacterial antigens in tuberculosis patients with diabetes. Med Princ Pract 17: 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Al-Attiyah R, Mustafa AS (2008) Characterization of human cellular immune responses to novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens encoded by genomic regions absent in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun 76: 4190–4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Al-Khodari NY, Al-Attiyah R, Mustafa AS (2011) Identification, diagnostic potential, and natural expression of immunodominant seroreactive peptides encoded by five Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific genomic regions. Clin Vaccine Immunol 18: 477–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mustafa AS, Al-Saidi F, El-Shamy AS, Al-Attiyah R (2011) Cytokines in response to proteins predicted in genomic regions of difference of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Microbiol Immunol 55: 267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mustafa AS, Shaban FA (2006) Propred analysis and experimental evaluation of promiscuous Th1 cell epitopes of three major secreted antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Tuberculosis (Edinb) 86: 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Al-Attiyah R, Mustafa AS (2010) Characterization of human cellular immune responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins encoded by genes predicted in RD15 genomic region that is absent in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 59: 177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Al-Attiyah RJ, Mustafa AS (2009) Mycobacterial antigen-induced T helper type 1 (Th1) and Th2 reactivity of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from diabetic and non-diabetic tuberculosis patients and Mycobacterium bovis bacilli Calmette-Guérin (BCG)-vaccinated healthy subjects. Clin Exp Immunol 158: 64–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mustafa AS, Oftung F, Amoudy HA, Madi NM, Abal AT, et al. (2000) Multiple epitopes from the Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT-6 antigen are recognized by antigen-specific human T cell lines. Clin Infect Dis 30 Suppl 3: S201–S205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mustafa AS, Abal AT, Shaban F, El-Shamy AM, Amoudy HA (2005) HLA-DR binding prediction and experimental evaluation of mycolyltransferase (Ag85B), a major secreted antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Med Princ Pract 14: 140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mustafa AS, Shaban FA, Al-Attiyah R, Abal AT, El-Shamy AM, et al. (2003) Human Th1 cell lines recognize the Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT-6 antigen and its peptides in association with frequently expressed HLA class II molecules. Scand J Immunol 57: 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mustafa AS, Oftung F (1993) Long-lasting T-cell reactivity to Mycobacterium leprae antigens in human volunteers vaccinated with killed M. leprae . Vaccine 11: 1108–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Singh H, Raghava GPS (2001) ProPred: Prediction of HLA-DR binding sites. Bioinformatics 17: 1236–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Al-Attiyah R, Mustafa AS (2004) Computer-assisted prediction of HLA-DR binding and experimental analysis for human promiscuous Th1 cell peptides in a novel 24-kDa secreted lipoprotein (LppX) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Scand J Immunol 59: 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mustafa AS (2009) Th1-cell reactivity and HLA-DR binding prediction for promiscuous recognition of MPT63 (Rv1926c), a major secreted protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Scand J Immunol 69: 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mustafa AS (2010) In silico binding predictions for identification of HLA-DR-promiscuous regions and epitopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein MPT64 (Rv1980c), and their recognition by human Th1 cells. Med Princ Pract 19: 367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nielsen M, Lund O (2009) NN-align. An artificial neural network-based alignment algorithm for MHC class II peptide binding prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 10: 296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang P, Sidney J, Dow C, Mothé B, Sette A, et al. (2008) A systematic assessment of MHC class II peptide binding predictions and evaluation of a consensus approach. PLoS Comput Biol 4: e1000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gupta SK, Srivastava M, Akhoon BA, Smita S, Schmitz U, et al. (2011) Identification of immunogenic consensus T-cell epitopes in globally distributed influenza-A H1N1 neuraminidase. Infect Genet Evol 11: 308–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Okkels LM, Brock I, Follmann F, Aager EM, Arend SM, et al. (2003) PPE protein (Rv3873) from DNA segment RD1 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: strong recognition of both specific T-cell epitopes and epitopes conserved within the PPE family. Infect Immun 71: 6116–6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mustafa AS (1988) Identification of T-cell-activating recombinant antigens shared among three candidate antileprosy vaccines, killed M. leprae, M. bovis BCG, and mycobacterium w. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis 56: 265–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dheda K, van Zyl Smit R, Badri M, Pai M (2009) T-cell interferon-gamma release assays for the rapid immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis: clinical utility in high-burden vs. low-burden settings. Curr Opin Pulm Med 15: 188–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Storla DG, Kristiansen I, Oftung F, Korsvold GE, Gaupset M, et al. (2009) Use of interferon gamma-based assay to diagnose tuberculosis infection in health care workers after short term exposure. BMC Infect Dis 9: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mustafa AS (2010) Cell mediated immunity assays identify proteins of diagnostic and vaccine potential from genomic regions of difference of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Kuwait Med J 42: 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mustafa AS (2011) Comparative evaluation of MPT83 (Rv2873) for T helper-1 cell reactivity and identification of HLA-promiscuous peptides: studies in M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects. Clin Vaccine Immunol 18: 1752–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Al-Attiyah R, Shaban FA, Wiker HG, Oftung F, Mustafa AS (2003) Synthetic peptides identify promiscuous human Th1 cell epitopes of the secreted mycobacterial antigen MPB70. Infect Immun 71: 1953–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aoshi T, Nagata T, Suzuki M, Uchijima M, Hashimoto D, et al. (2008) Identification of an HLA-A*0201-restricted T-cell epitope on the MPT51 protein, a major secreted protein derived from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, by MPT51 overlapping peptide screening. Infect Immun 76: 1565–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Launois P, DeLeys R, Niang MN, Drowart A, Andrien M, et al. (1994) T-cell-epitope mapping of the major secreted mycobacterial antigen Ag85A in tuberculosis and leprosy. Infect Immun 62: 3679–3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oftung F, Mustafa AS, Shinnick TM, Houghten RA, Kvalheim G, et al. (1988) Epitopes of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 65-kilodalton protein antigen as recognized by human T cells. J Immunol 141: 2749–2754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Silver RF, Wallis RS, Ellner JJ (1995) Mapping of T cell epitopes of the 30-kDa alpha antigen of Mycobacterium bovis strain bacillus Calmette-Guérin in purified protein derivative (PPD)-positive individuals. J Immunol 154: 4665–4674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dimitrov I, Garnev P, Flower DR, Doytchinova I (2010) MHC Class II Binding Prediction-A Little Help from a Friend. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010: 705821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nielsen M, Justesen S, Lund O, Lundegaard C, Buus S (2010) NetMHCIIpan-2.0 - Improved pan-specific HLA-DR predictions using a novel concurrent alignment and weight optimization training procedure. Immunome Res 13;6: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bhasin M, Raghava GPS (2007) A hybrid approach for predicting promiscuous MHC class I restricted T cell epitopes. J Biosci 32: 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Singh H, Raghava GPS (2003) ProPred1: Prediction of promiscuous MHC class-I binding sites. Bioinformatics 19: 1009–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Du G, Chen CY, Shen Y, Qiu L, Huang D, et al. (2010) TCR repertoire, clonal dominance, and pulmonary trafficking of mycobacterium-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T effector cells in immunity against tuberculosis. J Immunol 185: 3940–3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bruns H, Meinken C, Schauenberg P, Härter G, Kern P, et al. (2009) Anti-TNF immunotherapy reduces CD8+ T cell-mediated antimicrobial activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in humans. J Clin Invest 119: 1167–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]