Abstract

Asthma is a chronic lung disease that affects people of all ages and is characterized by high morbidity. The mechanisms of asthma pathogenesis are unclear, and there is a need for development of diagnostic biomarkers and greater understanding of regulation of inflammatory responses in the lung. Post-transcriptional regulation of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors by the action of microRNAs and RNA-binding proteins on stability or translation of mature transcripts is emerging as a central means of regulating the inflammatory response. In this study, we demonstrate that miR-570-3p expression is increased with TNFα stimuli in normal human bronchial epithelial cells (2.6 ± 0.6, p = 0.01) and the human airway epithelial cell line A549 (4.6 ± 1.4, p = 0.0068), and evaluate the functional effects of its overexpression on predicted mRNA target genes in transfected A549 cells. MiR-570-3p upregulated numerous cytokines and chemokines (CCL4, CCL5, TNFα, and IL-6) and also enhanced their induction by TNFα. For other cytokines (CCL2 and IL-8), the microRNA exhibited an inhibitory effect to repress their upregulation by TNFα. These effects were mediated by a complex pattern of both direct and indirect regulation of downstream targets by miR-570-3p. We also show that the RNA-binding protein HuR is a direct target of miR-570-3p, which has implications for expression of numerous other inflammatory mediators that HuR is known regulate post-transcriptionally. Finally, expression of endogenous miR-570-3p was examined in both serum and exhaled breath condensate (EBC) from asthmatic and healthy patients, and was found to be significantly lower in EBC of asthmatics and inversely correlated to their lung function. These studies implicate miR-570-3p as a potential regulator of asthmatic inflammation with potential as both a diagnostic and therapeutic target in asthma.

Keywords: MicroRNA, asthma, inflammation, airway, biomarker, cytokines, post-transcriptional regulation

Introduction

Asthma is a highly prevalent disease that affects close to 10% of the U.S. population [1]. It is characterized by chronic inflammation of the airways, bronchial hyper-responsiveness, and reversible airflow obstruction triggered by exposure to various environmental stimuli [2]. Asthma pathogenesis arises from a complex interaction between genetic and environmental factors, in which the interplay between the respiratory epithelium and the innate and adaptive immunity has a central role [3]. The molecular pathogenesis of asthma is complex, and regulatory mechanisms that govern the inflammatory processes are still poorly understood.

Acting as the first interface between the host and the environment, the airway epithelium participates in activation of innate immunity and production of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators in response to microbes, allergens, pollutants, and other stimuli [4]. In conditions predisposing to the development of allergic and inflammatory responses, epithelial cell-derived inflammatory mediators attract leukocytes and instruct adaptive immunity, thus promoting and sustaining the chronic inflammatory changes seen in asthma [5]. As such, the airway epithelium is a prime target for anti-inflammatory agents and as a source of biomarkers to characterize and diagnose asthma.

Post-transcriptional regulation of inflammatory genes by the integrated action of microRNAs (miRNAs) and RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) is emerging as a central means of regulating the immune response [6,7]. MiRNA and RBP associations are dynamically regulated according to cellular responses through several signaling pathways, and as a result, allow for rapid adjustment in the timing and amplitude of gene expression according to changing environmentalcues [8-11]. Together the factors can have either competitive or cooperative roles when forming ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes with their targets [12-15]. In particular, miRNAs are short, single-stranded, non-coding RNA molecules that associate with members of the Argonaute family of proteins (such as Ago2) and form the central component of RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) [16]. Binding of RISC to mRNA transcripts, usually in the 3’ untranslated region (3’ UTR), typically leads to decreased mRNA stability or translational repression [16]. Association of RBPs like HuR/ELAVL1 with transcripts also occurs through regulatory regions present in the 3’ UTR [17]. HuR binds to numerous proinflammatory transcripts and promotes overexpression of cytokines and chemokines by mRNA stabilization or by translational control, and genome-wide analysis of HuR-associated transcripts in airway epithelial cells indicates chemokines are preferential targets [18].

Increasing evidence indicates that miRNAs are differentially expressed in asthmatics compared to non-asthmatics, and that these are capable of regulating allergic mediators [19-24]. In this study, we follow-up on the observation of increased miR-570-3p expression in a miRNA profiling screen of TNFα-treated airway epithelial cells [25] to explore potential targets of miR-570-3p. To date, little has been published regarding miR-570-3p, but it has been implicated in gastric malignancies and lung disease [26-29]. We show that the miRNA alters expression of multiple cytokines and chemokines, and the expression of HuR. In support of the clinical relevance of our results, we found that levels of miR-570-3p were differentially expressed in exhaled breath condensate (EBC) of asthmatics as compared to healthy subjects.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

The study was approved by the Penn State College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent. Patients were classified as asthmatic based on history and lung function, including forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) reversible by > 12% and > 200 ml post-bronchodilator, or airway hyper-responsiveness by methacholine (provocating concentration producing a 20% fall in FEV1 of less than 8 mg/ml). Patients were considered allergic if they had a history of aeroallergen sensitivity and at least one positive skin test to a standard panel of 40 relevant aeroallergens, and non-allergic if the skin test panel was negative. Exhaled breath condensates were collected using an ECoScreen condenser (Jaeger, Wurzburg, Germany) over a collection time of 20 minutes. Blood was collected by venipuncture at the same time. Total RNA was isolated from each biofluid, processed, and analyzed for qPCR analysis as described previously [20,21]. Briefly, RNA was isolated by TRIzol isolation (Life Technologies) and reverse transcribed to cDNA using the miScript Reverse Transcription Kit (QIAGEN) to add a universal adapter to the 3’ end of miRNAs. Samples were analyzed by qPCR as previously described and data were normalized to snoRD44 as an internal standard [20,21].

Tissue culture and cell treatments

All cells were maintained in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. A549 human lung carcinoma cells (ATCC) were cultured in Eagle’s F12K media (ATCC) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), and HEK293T human embryonic kidney cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM (Cellgro) using the same supplements. NuLi-1 normal human bronchial epithelial cells (ATCC) were grown in serum-free BEGM (Lonza) without gentamycin-amphotericin B and supplemented with 50 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen). Where indicated, cells were treated with 50 ng/ml TNFα (BD Biosciences) or 5 μg/ml Actinomycin D (Sigma) for the times given.

Cloning of luciferase reporter plasmids

To generate the HuR 3’ UTR reporter constructs, template cDNA was first prepared from untreated A549 cells using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase and oligo (dT)12-18 primer (both from Invitrogen), followed by RNase H treatment (Invitrogen) to remove RNA:DNA hybrids. The target regions were then amplified using Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs) in sequential rounds of PCR to increase product and add restriction endonuclease sites for subsequent cloning via XbaI and FseI into the pSGG-CCL2-3UTR firefly reporter vector (SwitchGear Genomics #S203192). The following primers were purchased from IDT DNA: round 1 full-length 3’ UTR, 5’-GTCCCACAAATAActcgctca-3’ and 5’-ttcgcaatgatcccacttca-3’; round 2 full-length 3’ UTR (bases changed/added in lowercase, recognition sites underlined), 5’-aaatctagaGTCCCACAAATAACTC-3’ and 5’-aaaggccggccCGCAATGATCCCACT-3’; round 1 proximal 3’ UTR, 5’-cgcccgcatccagatttt-3’ and 5’-acccaaaatgtcaaggcagt-3’; round 2 proximal 3’ UTR (bases changed/added in lowercase, recognition sites underlined), 5’-aaatctagaGTCCCACAAATAACTC-3’ and 5’-aaaggccggccACCCAAAATGTCAAG-3’. Plasmid DNA was isolated from multiple colonies using the Zyppy Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research) for screening via restriction analysis, and all positive clones were confirmed by sequencing at the Penn State University Nucleic Acid Facility. The final full-length 3’ UTR construct, pSGG-HuR-FL3UTR, includes the full-length HuR 3’ UTR (nt 1136 - 6057 of GenBank Accession # NM_ 001419.2) with three minor sequence variants noted: NCBI dbSNP IDs rs4804056, rs12983784, and rs5826992. The final proximal 3’ UTR construct, pSGG-HuR-prox3UTR, includes the first 1113 nt of the HuR 3’ UTR (nt 1136 - 2261 of GenBank Accession # NM_ 001419.2), and includes NCBI dbSNP ID rs4804056 as above.

Transient transfections and luciferase reporter assays

For miRNA overexpression experiments, A549 cells were grown to 50-60% confluence in 6-well plates and transfected with 10 nM AllStars Negative Control siRNA or miR-570-3p mimic (both from QIAGEN) using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer. Media was collected and replaced with fresh medium containing 0 or 50 ng/ml TNFα 24 h post-transfection, and after 4 h treatment cells and media were harvested for isolation of both RNA and protein. For luciferase reporter assays, HEK293T cells were grown to 70-80% confluence in 6-well plates and co-transfected with 50 ng of pRL-TK vector (Promega #E2241) and 500 ng of either pSGG-empty-3UTR (SwitchGear Genomics #S-290005), pSGG-HuR-FL3UTR, or pSGG-HuR-prox3UTR and 10 nM of AllStars Negative Control siRNA or miR-570-3p mimic (both from QIAGEN) using 600 ng total DNA and 4.5 μl Attractene Transfection Reagent (QIAGEN) per well. Cells were harvested by trypsinization 24 h post-transfection and lysed in 150 μl 1x PLB prior to storage at -70°C. Frozen samples were thawed for 3 min. in a room temperature water bath, centrifuged for 1 min. at max speed (4°C), and supernatants kept on ice for activity assays using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Promega) with normalization to Renilla luciferase activity.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and the Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research) as described by the manufacturers and quantified by UV absorbance at 260 nm. cDNA synthesis for mRNA was done using 2 μg RNA and the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and for miRNA using 1 μg RNA and the qScript microRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Quanta Biosciences). Quantitative Real-Time PCR was performed using template cDNA, 2x iTaq Universal SYBR Green SuperMix (BioRad), and the gene-specific primers in Table 1. All reactions were run in 96-well plates on the MyiQ2 Two Color Real-Time Detection System (Bio-Rad) using the following program: 2 min hot start at 95°C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 30 or 60 s at 60°C (for miRNA and mRNA, respectively), and 2 min at 10°C. Data were analyzed by the ΔΔCt method with normalization to the endogenous control GAPDH (mRNA) or snoRD44 (miRNA).

Table 1.

List of primers used for qPCR

| Target | Primer Sequence(s) (5’- > 3’) |

|---|---|

| miR-570-3p | CGAAAACAGCAATTACCTTTGC |

| GAPDH | GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT, TTGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCG |

| ELAVL1 (HuR) | GGCTGGTGCATTTTCATCTAC, CCATCGCGGCTTCTTCATAG |

| CCL2 | GCTCAGCCAGATGCAATCA, AGATCTCCTTGGCCACAATG |

| CCL4 | TGCTGCTTTTCTTACACTGCG, CTCATGGAGAAGCATCCGGG |

| CCL5 | TCCCCATATTCCTCGGACAC, TGTACTCCCGAACCCATTTC |

| CCL8 | GGGACTTGCTCAGCCAGATT, CATCTCTCCTTGGGGTCAGC |

| IL6 | AGGAGACTTGCCTGGTGAAA, CAGGGGTGGTTATTGCATCT |

| IL6R | CGTGCCAGTATTCCCAGGAG, GCTGCAAGATTCCACAACCC |

| IL8 | TAGCAAAATTGAGGCCAAGG, AAACCAAGGCACAGTGGAAC |

| IL13RA1 | AACTTCCCGTGTGAAACCTG, ACCAGGGACCATGAAACAAG |

| IL26 | TGGGGTGAAGGGAAATGCTG, AGAGAGCGTCAACAGCTTGG |

| STAT1α | AGACTTCAGACCACAGACAACC, TTCATGCTCTATACTGTGTTCATC |

| STAT3 | AGTGAAAGCAGCAAAGAAGGAG, CCTTGGGAATGTCAGGATAGAG |

| TNF | CATGTTGTAGCAAACCCTCAAG, GATGGCAGAGAGGAGGTTGA |

| VDR | CAGGATTCAGAGACCTCACCTC, CTCCTCCTCATGCAAGTTCAG1113 |

ELISA, Luminex assays, and immunoblotting

Secreted CCL2 protein was quantified from A549 cell culture media using the Quantikine ELISA Human CCL2/MCP-1 Immunoassay (R&D Systems) as described by the manufacturer. Samples were diluted 1:10 in the appropriate Calibrator Diluent, absorbances measured on a GENios plate reader (Tecan), and 4-PL standard curves generated using Assay Blaster! Data Analysis Software (Enzo Life Sciences). Secreted CCL4/MIP-1β, CCL5/RANTES, IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα proteins were also quantified from A549 culture media using a custom Luminex Performance Assay (R&D Systems) as described by the manufacturer. Samples were run both undiluted and using 1:10 and 1:20 dilutions in the appropriate Calibrator Diluent, assays were run on a BioPlex 200 instrument (Bio-Rad), and 5-PL standard curves were generated using the included software. Samples that were out of range for detection at the low limit were considered for statistical purposes to have the minimum detectable dose (MDD) as defined by the manufacturer for each individual protein.

Cell pellets for immunoblotting were lysed in 1x PLB (100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 0.5% NP-40) for 10 min on ice in the presence of EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), then centrifuged for 5 min at maximum speed (4°C) to clear cellular debris. Samples were prepared for western blotting by boiling for 5 min in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and subjected to denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 10% SDS-PAGE gels. The following antibodies were used: HuR, 1/1000 of Santa Cruz #sc-5261; beta-actin, 1/5000 of Sigma #A5441; donkey anti-mouse IgG, 1/5000 of Santa Cruz #sc-2314.

Statistical analysis

Differences in miRNA expression between asthmatic and non-asthmatic subjects was determined by Wilcoxin signed-rank test, with a significance set at p < 0.05. Association between FEV1 and miRNA expression was determined by Pearson correlation testing, with a significance set at p < 0.05. Hypothesis testing was performed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni-Holm post-hoc tests using Prism (GraphPad Software, Version 4.0).

Results

miR-570-3p expression in airway cell lines and identification of predicted targets

We sought to identify miRNAs that are involved in regulation of inflammatory responses in airway epithelial cells, and initially identified miR-570-3p as a candidate based on a high-throughput qPCR screen of BEAS-2B airway cells [25]. We confirmed increased miR-570-3p expression in normal human bronchial epithelial cells NuLi-1 (2.6 ± 0.6 fold over control) as well as in the A549 airway epithelial cell line (4.6 ± 1.6 fold over control) following 18 h stimulation with 50 ng/ml TNFα (data not shown). As the response to TNFα treatment was slightly more robust with A549 cells, these were utilized for further experiments.

We next investigated mRNA targets related to the inflammatory process with putative miR-570-3p binding sites. The CoMeTa procedure [30] was used to generate a list of predicted targets (http://cometa.tigem.it/view_mirna.php?mirna=hsa-miR-570&r_mask=yes), from which transcripts of interest that were ranked highly and/or those within relevant networks via COOL analysis [30] were selected for further investigation (Table 2). These targets included cytokines and chemokines important to inflammatory responses, transcription factors in cytokine signaling pathways, the vitamin D receptor (VDR), and the RNA-binding protein HuR.

Table 2.

COOL analysis of predicted miR-570-3p targets

| Target (s) | KEGG pathway or GOTERM |

|---|---|

| CCL2, STAT1, STAT3 | hsa04062: Chemokine signaling pathway |

| CCL4, CCL8, IL26, TNF | hsa04060: Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction |

| ELAVL1 (HuR) | GO: 0010608~post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression |

| IL6R | GO: 0034097~response to cytokine stimulus |

| VDR | GO: 0051253~negative regulation of RNA metabolic process |

| IL13RA1 | n/a |

Effect of miR-570-3p on inflammatory mediators with and without TNFα stimulation

To determine the effect of miR-570-3p on expression of putative targets, A549 cells were transiently transfected with either negative control siRNA or miR-570-3p mimic for 24 h and then treated with either 0 or 50 ng/ml TNFα for 4 h. Total RNA was isolated for qPCR expression analysis of the mRNA targets listed in Table 2. Expression of IL6, IL8, and CCL5 was also evaluated as positive control, as these transcripts are known to increase with TNFα treatment. In addition, successful transfection of the mimic was confirmed in each experiment by qPCR for miR-570-3p (data not shown).

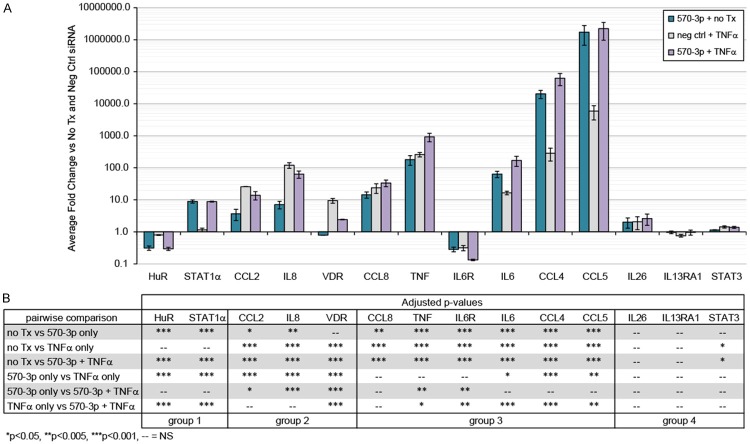

The results from qPCR expression analysis are shown as fold induction over the unstimulated, negative control-transfected cells (Figure 1A), and four patterns of mRNA regulation emerged (pairwise statistical comparisons between treatment conditions shown in Figure 1B). In the 1st group, we identified targets (HuR and STAT1α) that changed exclusively after miR-570-3p transfection, with no effects of TNFα alone or when the miRNA and TNFα were combined. The 2nd group was comprised of targets whose expression was induced by TNFα but attenuated by TNFα with miR-570-3p overexpression (CCL2, IL8, and VDR). Group 3 consisted of targets that were strongly influenced by either miR-570-3p and TNFα, with the combined treatment having a synergistic effect (CCL8, TNF, IL6R, IL6, CCL4, and CCL5). This group includes two targets not predicted to be regulated by this miRNA (IL6 and CCL5), suggesting that miR-570-3p may have indirect effects on the TNFα signaling pathway in addition to direct effects on specific transcripts. The expression of targets in Group 4 (IL26, IL13RA1, and STAT3) was unchanged with miR-570-3p, TNFα or the combined treatment.

Figure 1.

miR-570-3p alters mRNA expression of multiple targets, both alone and in combination with TNFα treatment. (A) A549 cells were transiently transfected for 24 h with negative control siRNA or miR-570-3p mimic, followed by 4 h treatment with 0 or 50 ng/ml TNFα and isolation of total RNA for qRT-PCR analysis. Data were normalized to GAPDH, and expression was calculated as fold change relative to negative control siRNA transfection without TNFα. Results are shown as mean ± SEM, n = 3. (B) One-way ANOVA with pairwise comparisons for the qPCR data shown in (A), with significant p-values indicated as: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

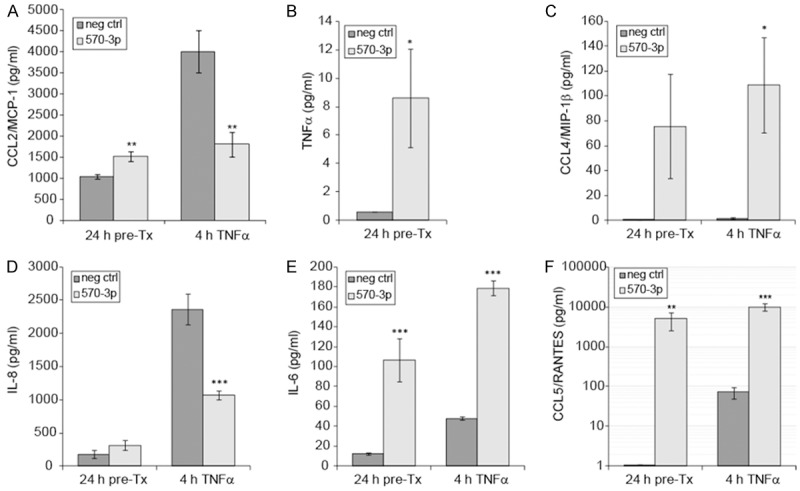

We next sought to confirm that the effects of miR-570-3p and/or TNFα on mRNA expression also resulted in changes in protein expression. Levels of CCL2/MCP-1 were evaluated by ELISA in A549 cell culture media samples collected 24 h post-transfection with negative control siRNA or miR-570-3p mimic and again after 4 h treatment with 50 ng/ml TNFα (Figure 2A). The latter samples reflect only protein secreted during the 4 h post-treatment rather than a cumulative 28 h sample, as culture medium was replaced prior to the addition of TNFα. As such, statistical comparisons were made only for the effect of miR-570-3p vs negative control siRNA within the same time point. Production of CCL2/MCP-1 protein followed the same pattern of mRNA expression seen by qPCR, with a slight increase over basal levels induced by miR-570-3p overexpression (1528 ± 110.2 vs 1048 ± 45.3 pg/ml, p = 0.0159), a strong increase induced with TNFα treatment (4011 ± 496 pg/ml), and attenuation of the TNFα response by miR-570-3p (1813 ± 290 pg/ml, p = 0.0131).

Figure 2.

Protein expression of selected cytokines and chemokines. (A) Secreted CCL2 protein was measured by ELISA following 24 h transfection of A549 cells ± miR-570-3p mimic and after 4 h treatment with 0 or 50 ng/ml TNFα (n = 4, **p < 0.02). (B-F) Luminex assays were performed to detect secreted TNFα (B), CCL4/MIP-1β (C), IL-8 (D), IL-6 (E), and CCL5/RANTES (F) in A549 cell culture medium as with ELISA. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 4), and asterisks indicate a significant difference between miR-570-3p and negative control transfection within the same timepoint (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.02, ***p < 0.01).

A custom Luminex assay was then used to evaluate the levels of TNFα, CCL4/MIP-1β, IL-8, IL-6, and CCL5/RANTES from the same media samples described above (Figure 2B-F). As the assay does not distinguish recombinant TNFα protein from endogenous, changes in TNFα protein could not be reliably measured from TNFα treated cells. However, transfection of miR-570-3p alone caused a small, yet significant increase in TNFα protein (Figure 2B, 8.60 ± 3.49 vs 0.60 pg/ml, p = 0.0470). CCL4/MIP-1β levels followed the same pattern seen by qPCR, with increases following miR-570-3p overexpression (Figure 2C, 75.6 ± 42.0 vs 0.44 pg/ml, p = 0.0617) but only significantly when combined with TNFα treatment (108.8 ± 38.4 vs 1.87 ± 0.51 pg/ml, p = 0.0320).

For proteins that were not predicted targets of miR-570-3p (IL-8, IL-6, and CCL5/RANTES), protein expression was found to be highly similar to their corresponding mRNA levels. As with CCL2/MCP-1, secretion of IL-8 protein was more strongly influenced by TNFα treatment (2364 ± 233 pg/ml) than the mimic (315.8 ± 74.8 pg/ml), and the combined treatment suggests that the presence of miR-570-3p interferes with induction by TNFα (1070 ± 63 pg/ml, Figure 2D, p = 0.0017). Production of IL-6 was enhanced by miR-570-3p (106.8 ± 21.5 vs 12.5 ± 1.40 pg/ml, p = 0.0047) and synergistically increased when combined with TNFα treatment (Figure 2E, 178.5 ± 7.39 vs 48.0 ± 1.84 pg/ml, p = 0.0001). CCL5/RANTES expression was strongly increased by miR-570-3p (4957 ± 2349 vs 1.08 pg/ml, p = 0.0143), well beyond the levels seen with TNFα treatment alone (72.8 ± 22.6 pg/ml), and again was synergistically increased with combined treatment (10.021 ± 2271 pg/ml, p = 0.0047). Taken together, these data suggest that overexpression of miR-570-3p has both direct and indirect effects on many gene products related to the inflammatory response.

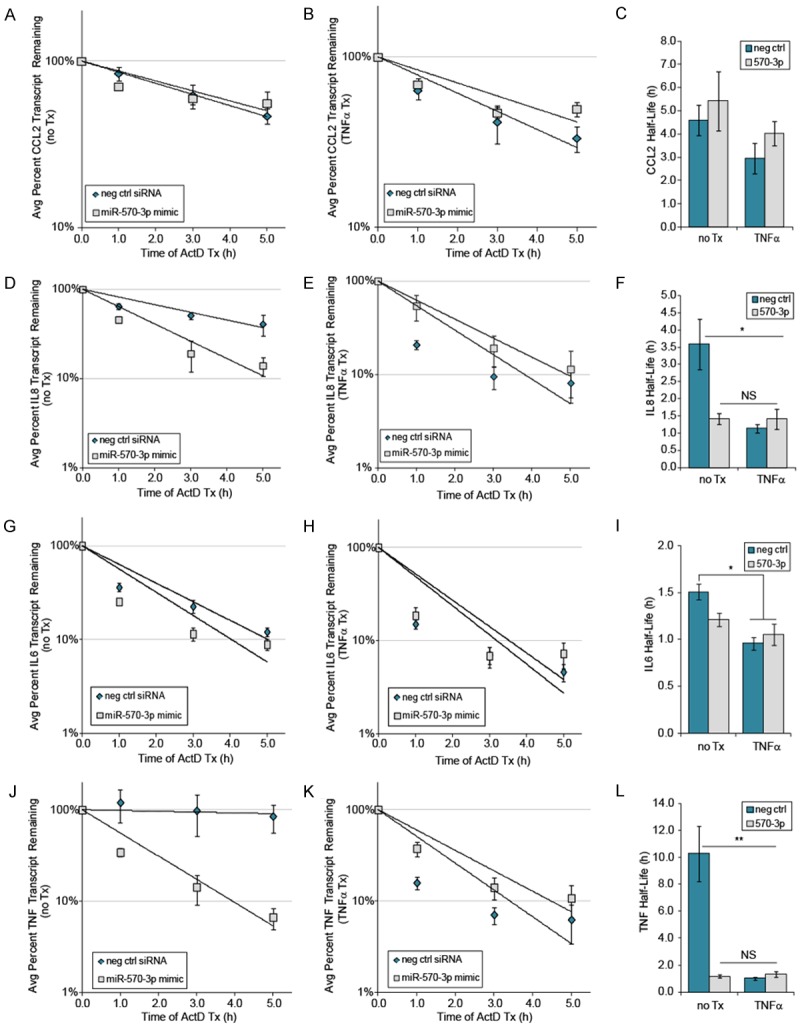

Functional analysis of mRNA stability with miR-570-3p and TNFα

Binding of miRNA to a target mRNA can result in either mRNA degradation or translational inhibition [16]. To determine the effects of miR-570-3p overexpression and/or TNFα treatment on mRNA stability, A549 cells were transfected with or without the miR-570-3p mimic for 24 h and treated for 4 h ± 50 ng/ml TNFα, followed by the addition of Actinomycin D. RNA was isolated at the time of Actinomycin D addition (0 h) and at varying timepoints afterwards (1, 3, and 5 h). Based on the protein expression data, CCL2, IL8, IL6, and TNF were selected for mRNA stability analysis to represent two targets each from expression groups 2 and 3 (Figure 1), as well as two each of predicted and non-predicted miR-570-3p targets (Table 2).

Decay curves for each transcript were calculated both in the absence (Figure 3A, 3D, 3G, 3J, left panels) and presence (Figure 3B, 3E, 3H, 3K, center panels) of TNFα, and half-lives were derived from the independent decay curves of each experiment (Figure 3C, 3F, 3I, 3L, right panels). For CCL2 (Figure 3A-C), mRNA stability was not strongly affected by either the miRNA mimic or TNFα treatment (p = ns for each comparison). In contrast, both the miR-570-3p mimic and TNFα treatment significantly decreased the stability of the IL8 transcript relative to the no treatment control (3.59 ± 0.74 h vs 1.42 ± 0.15 and 1.14 ± 0.13, p<0.03), although the differences among treatment groups was not significant and the combined treatment had no additional effect (Figure 3D-F, 1.41 ± 0.29 h). While the miR-570-3p mimic alone did not significantly decrease the IL6 transcript stability (p = ns), TNFα treatment did both alone and in combination with miR-570-3p, although the changes in half-life were small (1.50 ± 0.08 h vs 0.96 ± 0.07 and 1.05 + 0.11 h, respectively, Figure 3G-I). Strikingly, the presence of either the mimic alone or TNFα treatment was sufficient to strongly destabilize the TNF transcript (p < 0.02, 10.28 ± 2.07 h vs 1.17 ± 0.13 and 1.01 + 0.13 h, respectively), while the combined treatment had no additional effect (Figure 3J-L). This was consistent with the observation of minimal TNFα protein production with miR-570-3p (Figure 2B).

Figure 3.

Differential effect of miR-570-3p on mRNA stability of selected transcripts. A549 cells were transfected and treated as described previously, followed by addition of Actinomycin D and isolation of RNA at the indicated time points for qPCR analysis of transcript levels in the absence (A, D, G and J) and presence (B, E, H and K) of TNFα (n = 3). (C, F, I and L) Half-lives for each of the transcripts were calculated from 3 independent experiments. Error bars represent the SEM (n=3), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.02 compared to control treatment.

HuR is a direct target of miR-570-3p

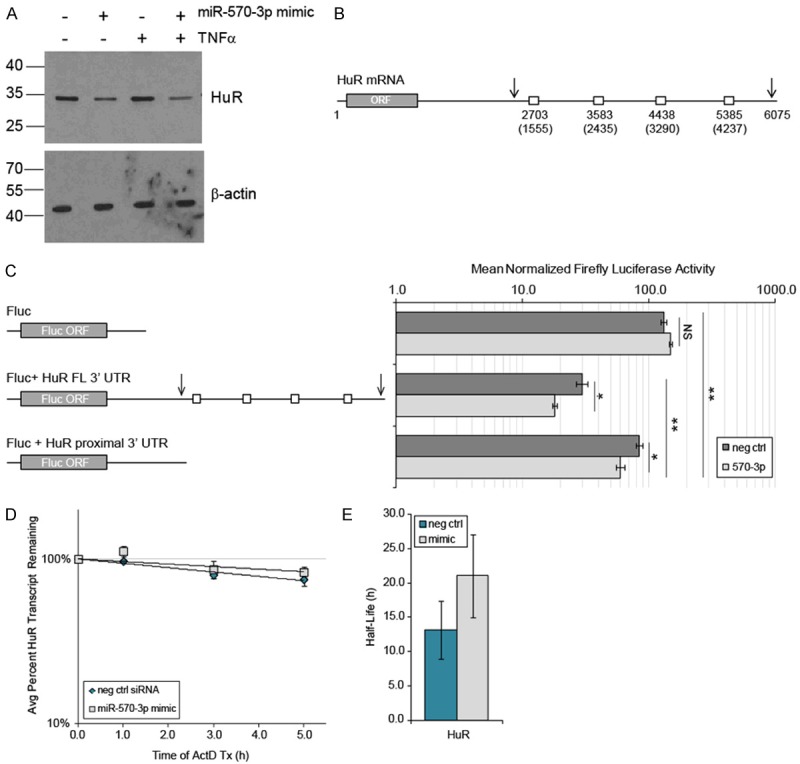

Another predicted target of miR-570-3p that is of particular interest is HuR, which had 2-3-fold lower mRNA levels with the mimic (Figure 1A). HuR is known to bind a number of the other predicted miR-570-3p targets (CCL2, CCL8, IL6, IL8, and TNFα) in response to inflammatory stimuli [18], and thus downregulation of its expression may potentially influence many of these proinflammatory targets. To determine the effect of miR-570-3p overexpression on HuR protein levels, A549 cells were transfected as described and cell lysates collected for western immunoblotting. Consistent with our qPCR data, HuR protein was decreased by the miR-570-3p mimic in the presence and absence of TNFα, while TNFα alone had no apparent effect (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

HuR is a target of miR-570-3p. (A) Western immunoblotting of HuR and loading control β-actin from protein extracts of A549 cells transfected for 24 h with control siRNA or miR-570-3p mimic, followed by 4 h treatment with 0 or 50 ng/ml TNFα. Image is representative of n = 3. (B) Schematic of miR-570-3p binding sites in the HuR 3’ UTR predicted by 2 or more search algorithms. Numbers in parenthesis indicate the nucleotide position within the 3’ UTR, and numbering above indicates positions within the full-length HuR transcript. Arrows represent the location of polyadenylation sites. (C) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with luciferase reporter constructs containing either empty control, HuR full-length (FL) 3’ UTR, or HuR proximal 3’ UTR sequence and either negative control siRNA or miR-570-3p mimic for 24 h, followed by luciferase activity assays. Mean ± SEM, n = 3, *p < 0.03, **p < 0.01. (D) HuR mRNA decay and (E) half-life of the endogenous HuR transcript in A549 cells transfected and treated as in (A), followed by addition of Actinomycin D and isolation of RNA for qPCR analysis at the indicated time points (n = 3). Mean ± SEM, n = 3, p = NS.

As microRNA most commonly exert their effects via the 3’ UTR of transcripts, we sought to locate specific miR-570-3p binding sites within the HuR 3’ UTR. To do this, we interrogated the mature hsa-miR-570-3p sequence (miRBase [31] accession # MIMAT0003235) and the full-length HuR 3’ UTR sequence (GenBank Accession # NM_ 001419.2) using the following programs/algorithms: PITA [32], miRanda [33,34], starBase v1.0 [35], RNAup [36], and RNAhybrid [37]. Four miR-570-3p binding sites were predicted by two or more algorithms, shown schematically in Figure 4B. Also indicated as arrows are the positions of two alternative polyadenylation sites within the 3’ UTR, as both the full-length 6 kb transcript and a shorter, 2.4 - 2.7 kb transcript with differential stability have been identified [38,39].

To test whether the HuR 3’ UTR is regulated by miR-570-3p, luciferase reporter constructs were generated containing both the full-length and the shorter, proximal 3’ UTR sequences. Transient transfections were then performedin HEK293T cells using the HuR 3’ UTR reporters or an empty 3’ UTR construct in the presence or absence of the miR-570-3p mimic. As shown in Figure 4C, both the proximal and full-length HuR 3’ UTR reporters had significantly lower luciferase activity compared to the empty vector, and the full-length construct also had significantly less activity than the proximal 3’ UTR construct. Additionally, co-transfection of miR-570-3p significantly decreased the activity of both the full-length (29.6 ± 3.1 vs 17.9 ± 0.8, p < 0.020) and proximal 3’ UTR reporters (84.4 ± 5.3 vs 59.3 ± 4.7, p = 0.024). Given that the consensus predicted miR-570-3p binding sites were all located within the full-length sequence, this suggests that there are additional sites within the proximal 3’ UTR that are targeted by this miRNA.

Having established that miR-570-3p can target elements found within both the shorter and full-length HuR 3’ UTR, we next conducted mRNA stability assays of endogenous HuR using primers that would amplify both forms of the transcript. A549 cells were transfected with or without the miR-570-3p mimic and treated with Actinomycin D in order to calculate mRNA decay curves (Figure 4D) and the approximate half-life of the transcript (Figure 4E). The results indicate little to no difference in HuR mRNA stability with the mimic compared to negative control, and taken together with our other data, suggest that binding of miR-570-3p causes translational inhibition rather than destabilization of the HuR transcript.

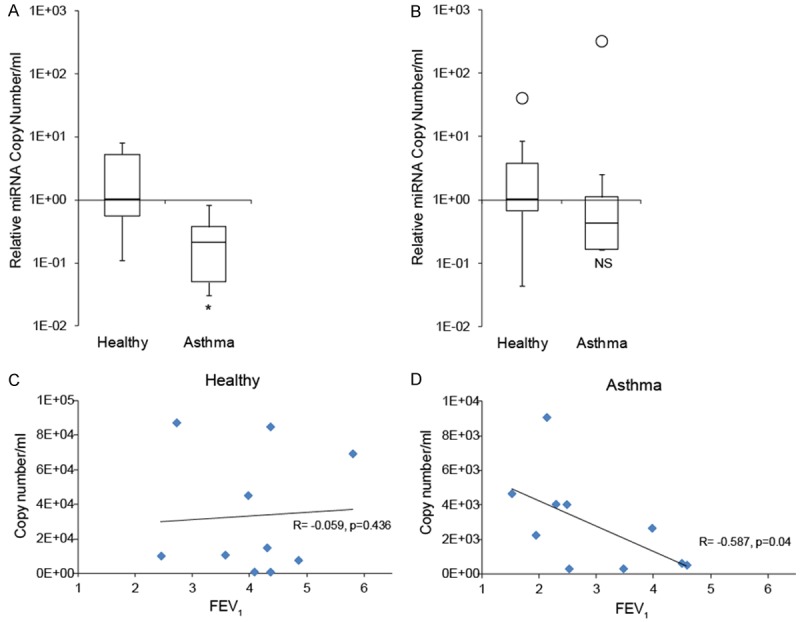

miR-570-3p expression in human subjects

The induction of miR-570-3p by inflammatory stimuli in airway cells in vitro led us to investigate whether this miRNA could be a factor in human airway disease. As both exhaled breath condensate (EBC) and serum have been shownto be a source of biomarkers in patients with asthma [20,21], we examined expression of miR-570-3p in each biofluid from healthy subjects and mild to moderate persistent asthmatics (n = 10 each, Table 3). Surprisingly, expression of miR-570-3p was significantly lower in EBC from asthmatic patients compared to control subjects (p = 0.026, Figure 5A). In contrast, expression was found to be similar in serum (Figure 5B), suggesting that the differential expression of this miRNA in asthma originates in the lung. When EBC levels of miR-570-3p from individual patients were plotted against their lung function (FEV1%), no correlation was present in healthy subjects (Figure 5C, p = 0.436). However, we found a significant inverse correlation in asthmatic patients (p = 0.04, Figure 5D), with the highest miR-570-3p levels present in subjects with the lowest FEV1.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study population

| Normal N = 10 | Asthma N = 10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Male/female | 6/4 | 4/6 |

| Age (y), mean (range) | 38.4 (23-65) | 49.2 (22-64) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 3/10 | 8/10 |

| FEV1 % predicted, mean (SD) | 91.3 (15.7) | 80.5 (24.1) |

| FEV1 (L), mean (SD) | 3.41 (1.16) | 2.56 (1.10) |

| FEV1 % Reversal, mean (SD) | ND | 15.8 (11.7) |

| Smoker (current, ex) | 3,1 | 4,1 |

| ICS1 | 0 | 0 |

| ICS/LABA2 | 0 | 5 |

| Anti-leukotriene | 0 | 3 |

| Anti-cholinergic | 0 | 2 |

| Serum RNA concentration (μg/ml), mean (SD) | 122.9 (43.3) | 96.5 (35.9) |

| EBC volume, mean (SD) | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.1) |

| EBC RNA concentration (μg/ml), mean (SD) | 125.0 (101.7) | 136.2 (161.6) |

ICS, inhaled corticosteroids;

LABA, long acting beta agonist.

Figure 5.

Expression of miR-570-3p in clinical samples from asthmatic patients. (A) miR-570-3p is differentially expressed in EBC of asthmatics vs. control subjects, but not in serum samples (B), *p < 0.05. (C) There was no association between miR-570-3p expression and FEV1% in healthy subjects (p = 0.436), but an inverse correlation (p = 0.04) in asthmatics (D).

Discussion

In this study, we studied the role of miR-570-3p in human airway epithelial cells and expression of selected mRNA targets, identified by computational analysis and selected for their relevance in the mechanisms of allergic inflammation. In exploring the functions of this miRNA, we demonstrate for the first time that the RNA binding protein HuR is a direct target of miR-570-3p. We also establish that this molecule affects the expression of multiple cytokines and chemokines, likely through complex mechanisms involving both direct and indirect effects. Finally, we provide evidence that asthmatic patients have significantly lower levels of miR-570-3p in EBC compared to healthy controls.

Gene targets of miR-570-3p and mechanisms of regulation

We determined that numerous cytokines and chemokines are differentially regulated by miR-570-3p, as transfection of miR-570-3p had significant but diverse effects on their expression. For some cytokines (IL-6, CCL4, CCL5), we observed increases in both mRNA and protein expression in excess of those induced by TNFα, a strong inflammatory stimulus. At the same time, miR-570-3p seems to inhibit TNFα-induced expression of CCL2 and IL-8. As miRNAs are primarily characterized as post-transcriptional repressors of gene expression, the increased expression of cytokines and chemokines driven by miR-570-3p indicates a complex system of direct and indirect regulation. The finding that miR-570-3p regulates targets which it is not predicted to bind (IL6, IL8, and CCL5) further supports the hypothesis that at least part of the observed effects are mediated by indirect mechanisms.

HuR is a well-established central player in post-transcriptional regulation of epithelial-derived chemokines, cytokines, and other inflammatory mediators [40-42], and other studies have shown that several miRNAs (miR-519, miR-125a, miR-16, miR-34a, miR-9, and miR-146) can regulate HuR levels [13,39]. Decreased endogenous HuR protein and HuR 3’ UTR reporter luciferase activity with overexpression of miR-570-3p strongly suggests that HuR is a direct target of this miRNA. The ability of miR-570-3p to suppress HuR raises the possibility that some changes observed in expression could be due to a loss of HuR regulation. It is possible that the inhibitory effect of miR-570-3p on CCL2 and IL-8 with TNFα treatment could be due to downregulation of HuR, while the rise in other HuR targets (such as IL6) could be due to loss of other indirect targets with regulatory functions. Future experiments will be needed to explore this question in greater detail.

In the case of TNFα, overexpression of miR-570-3p by itself was found to increase TNF mRNA expression while simultaneously increasing the rate of RNA decay, resulting in limited protein production. The same may also be true for CCL4 (although RNA decay was not evaluated), as strong increases in mRNA expression resulted in only minor levels of secreted protein, especially when compared to CCL5. Thus, it seems plausible that both TNFα and CCL4 are post-transcriptionally regulated by miR-570-3p and indirectly influenced at the level of gene transcription. However, additional evidence will be required to determine whether these are truly direct targets of this miRNA.

As mentioned above, the changes observed for non-predicted miR-570-3p targets indicate this miRNA may also be working through indirect means. In particular, the expression of IL-6 and CCL5 was strongly increased at both the mRNA and protein level, which is suggestive of a transcriptional effect. It is highly possible that miR-570-3p could exert its influence by regulating expression of genes involved in signaling and transcription. Among targets functionally upstream of cytokine expression, our computational analysis identified the transcription factors STAT1α and STAT3, both of which play important roles in cytokine signaling in the Jak-STAT pathway [43]. STAT1α is known to be a positive regulator of IL6 expression [44] and is involved in upregulation of cytokine and chemokine expression in the airways [45], and here we have shown that overexpression of miR-570-3p increases its mRNA levels. In addition, STAT3 is a positive regulator of CCL2 transcription [46], and although STAT3 mRNA levels did not change with miR-570-3p, the possibility remains that there are changes in protein expression. The vitamin D receptor (VDR) is another transcription factor we identified as a predicted target of miR-570-3p, and its ligand (1,25(OH)2D) has known immunomodulatory properties [47]. Vitamin D deficiency has also been associated with asthma and asthma severity [48,49].

An expanded search of predicted miR-570-3p targets reveals an interesting possibility in SIRT1. SIRT1 has been implicated in inflammation, and its inhibition is thought to be proinflammatory due to de-repression of NF-κB [50]. SIRT1 is also known to be positively regulated by HuR [51,52], and thus combined targeting of SIRT1 by miR-570-3p and a loss of HuR regulation could conceivably explain increased transcription of a number of NF-κB-responsive genes observed in our studies, including CCL2, CCL4, CCL5, IL6, IL8, and TNF [53,54]. Future work will be needed to explore this potential regulatory model and the mechanisms involved.

These seemingly competing influences of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation may reflect a timing mechanism, whereby transcription of proinflammatory cytokines is enhanced, but the factors necessary for stoppingthe response are also put in place for rapid gene downregulation once the transcriptional stimulus has been removed. Similar effects have been observed for miR-146a, which is induced by inflammatory stimuli early in the inflammatory response and later acts to inhibit inflammatory pathways [55,56]. In this manner, miR-570-3p may serve to enhance an immune response initially by promoting expression of cytokines, but also play a role in stoppingthe response by promoting degradation of mRNA later in the time course.

miR-570-3p as a candidate miRNA in asthma diagnosis

MicroRNAs detected in EBCs may have diagnostic potential in asthma, as studies have recently identified several miRNAs in this fluid to be differentially expressed between asthmatic and healthy subjects [21,57]. Previous results from our group showed lower levels of several miRNAs expected to influence the Th2 response (Let-7a, miR-155, miR-1248, and miR-1291) in asthmatics compared to non-asthmatics [21]. Consistent with these results, we found in this study that miR-570-3p is also downregulated in EBC from asthmatic patients. As miR-570-3p also appears to regulate expression of numerous inflammatory mediators, the question arises as to whether these miRNAs play a role in asthma pathogenesis and regulation of chronic inflammation, and/or whether they can be used as non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers. We observed an inverse relationship between expression of miR-570-3p and lung function (FEV1%) in asthmatics, but not healthy controls. These findings mirrored our previous finding of a negative correlation between miR-1248 expression and FEV1% in asthmatics, but not in controls [21]. The mechanisticsignificance of these findings is still unclear. As expression of these miRNAs is lower in asthma, it was surprising that their levels increased as lung function decreased. We expected that asthmatics with normal or near-normal lung function would be more similar to the healthy population, while those with poor lung function would have the lowest expression. However, similar paradoxical observations have been found for other inflammatory mediatorsin EBC. Kazani et al. found that lipoxin A expression was lower in healthy subjects compared to asthmatics, but that expression decreased in more severe asthmatics with lower lung function [58]. The reasons for these observations may be multifactorial, and may relate to mechanisms of mediator release into EBC, structural changes that occur in the airway, or changes related to chronic inflammation which can affect EBC composition. In addition, it is possible that there are feedback mechanisms which can alter miRNA expression depending on severity or chronicity of inflammation. Regardless of the mechanism, these miRNA expression differences could serve as a means of assessing asthma severity and possibly asthma control.

MicroRNAs are becoming recognized as important regulators of airway inflammation. This study identified miR-570-3p as a candidate marker in asthma and as a potential pro-inflammatory miRNA. It also demonstrated that miRNA can be positive regulators of gene expression, and are capable of exerting profound effects on inflammatory mediators. The mechanisms underlying these effects are complex and involve interplay of direct and indirect effects on multiple regulatory elements. A better understanding of these mechanisms may reveal novel therapeutic targets in asthma.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinician Scientist Development Award (FTI) and institutional funds from the Penn State College of Medicine. We thank Cathy Mende and Crystal Rhoads for their assistance in the collection and processing of samples.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None to declare.

Abbreviations

- 3’UTR

3’ untranslated region

- Ct

cycle threshold

- EBC

exhaled breath condensate

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in one second

- FEV1%

percent predicted FEV1

- ICS

inhaled corticosteroids

- LABA

long acting beta agonist

- miRNA

microRNA

- qPCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- RBPs

RNA-binding proteins

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

References

- 1.Moorman JE, Akinbami LJ, Bailey CM, Zahran HS, King ME, Johnson CA, Liu X. National surveillance of asthma: United States, 2001-2010. Vital Health Stat 3. 2012:1–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PJ. Immunology of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:183–192. doi: 10.1038/nri2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishmael FT. The inflammatory response in the pathogenesis of asthma. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2011;111:S11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stellato C. Glucocorticoid actions on airway epithelial responses in immunity: functional outcomes and molecular targets. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1247–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.041. quiz 1264-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holgate ST. The sentinel role of the airway epithelium in asthma pathogenesis. Immunol Rev. 2011;242:205–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palanisamy V, Jakymiw A, Van Tubergen EA, D’Silva NJ, Kirkwood KL. Control of cytokine mRNA expression by RNA-binding proteins and microRNAs. J Dent Res. 2012;91:651–658. doi: 10.1177/0022034512437372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pauley KM, Chan EK. MicroRNAs and their emerging roles in immunology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1143:226–239. doi: 10.1196/annals.1443.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erson AE, Petty EM. MicroRNAs in development and disease. Clin Genet. 2008;74:296–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breving K, Esquela-Kerscher A. The complexities of microRNA regulation: mirandering around the rules. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1316–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thapar R, Denmon AP. Signaling pathways that control mRNA turnover. Cell Signal. 2013;25:1699–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jing Q, Huang S, Guth S, Zarubin T, Motoyama A, Chen J, Di Padova F, Lin SC, Gram H, Han J. Involvement of microRNA in AU-rich element-mediated mRNA instability. Cell. 2005;120:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srikantan S, Tominaga K, Gorospe M. Functional interplay between RNA-binding protein HuR and microRNAs. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2012;13:372–379. doi: 10.2174/138920312801619394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castilla-Llorente V, Nicastro G, Ramos A. Terminal loop-mediated regulation of miRNA biogenesis: selectivity and mechanisms. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:861–865. doi: 10.1042/BST20130058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meisner NC, Filipowicz W. Properties of the regulatory RNA-binding protein HuR and its role in controlling miRNA repression. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;700:106–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jinek M, Doudna JA. A three-dimensional view of the molecular machinery of RNA interference. Nature. 2009;457:405–412. doi: 10.1038/nature07755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espel E. The role of the AU-rich elements of mRNAs in controlling translation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan J, Ishmael FT, Fang X, Myers A, Cheadle C, Huang SK, Atasoy U, Gorospe M, Stellato C. Chemokine transcripts as targets of the RNA-binding protein HuR in human airway epithelium. J Immunol. 2011;186:2482–2494. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plank M, Maltby S, Mattes J, Foster PS. Targeting translational control as a novel way to treat inflammatory disease: the emerging role of microRNAs. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43:981–999. doi: 10.1111/cea.12170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panganiban RP, Pinkerton MH, Maru SY, Jefferson SJ, Roff AN, Ishmael FT. Differential microRNA epression in asthma and the role of miR-1248 in regulation of IL-5. Am J Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;1:154–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinkerton M, Chinchilli V, Banta E, Craig T, August A, Bascom R, Cantorna M, Harvill E, Ishmael FT. Differential expression of microRNAs in exhaled breath condensates of patients with asthma, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and healthy adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:217–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solberg OD, Ostrin EJ, Love MI, Peng JC, Bhakta NR, Hou L, Nguyen C, Solon M, Barczak AJ, Zlock LT, Blagev DP, Finkbeiner WE, Ansel KM, Arron JR, Erle DJ, Woodruff PG. Airway epithelial miRNA expression is altered in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:965–974. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0027OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rebane A, Akdis CA. MicroRNAs in Allergy and Asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14:424. doi: 10.1007/s11882-014-0424-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woodruff PG. Subtypes of asthma defined by epithelial cell expression of messenger RNA and microRNA. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(Suppl):S186–189. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201303-070AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stellato C, Fang X, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M, Ishmael FT. Glucocorticoid (GC) Modulation of Global miRNA Profile in Human Airway Epithelial Cells. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;127:AB64. [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Angelo D, Palmieri D, Mussnich P, Roche M, Wierinckx A, Raverot G, Fedele M, Croce CtM, Trouillas J, Fusco A. Altered microRNA expression profile in human pituitary GH adenomas: down-regulation of miRNA targeting HMGA1, HMGA2, and E2F1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1128–1138. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang W, Sun J, Li F, Li R, Gu Y, Liu C, Yang P, Zhu M, Chen L, Tian W, Zhou H, Mao Y, Zhang L, Jiang J, Wu C, Hua D, Chen W, Lu B, Ju J, Zhang X. A frequent somatic mutation in CD274 3’-UTR leads to protein over-expression in gastric cancer by disrupting miR-570 binding. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:480–484. doi: 10.1002/humu.22014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, Li F, Mao Y, Zhou H, Sun J, Li R, Liu C, Chen W, Hua D, Zhang X. A miR-570 binding site polymorphism in the B7-H1 gene is associated with the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma. Hum Genet. 2013;132:641–648. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li K, Li Z, Zhao N, Xu Y, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Shang D, Qiu F, Zhang R, Chang Z. Functional analysis of microRNA and transcription factor synergistic regulatory network based on identifying regulatory motifs in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Syst Biol. 2013;7:122. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-7-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gennarino VA, D’Angelo G, Dharmalingam G, Fernandez S, Russolillo G, Sanges R, Mutarelli M, Belcastro V, Ballabio A, Verde P, Sardiello M, Banfi S. Identification of microRNA-regulated gene networks by expression analysis of target genes. Genome Res. 2012;22:1163–1172. doi: 10.1101/gr.130435.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D154–158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kertesz M, Iovino N, Unnerstall U, Gaul U, Segal E. The role of site accessibility in microRNA target recognition. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1278–1284. doi: 10.1038/ng2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. Human MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS, Sander C. The microRNA. org resource: targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D149–153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang JH, Li JH, Shao P, Zhou H, Chen YQ, Qu LH. starBase: a database for exploring microRNA-mRNA interaction maps from Argonaute CLIP-Seq and Degradome-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D202–209. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gruber AR, Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Neubock R, Hofacker IL. The Vienna RNA websuite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W70–74. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kruger J, Rehmsmeier M. RNAhybrid: microRNA target prediction easy, fast and flexible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W451–454. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Ahmadi W, Al-Ghamdi M, Al-Haj L, Al-Saif M, Khabar KS. Alternative polyadenylation variants of the RNA binding protein, HuR: abundance, role of AU-rich elements and auto-Regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3612–3624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Govindaraju S, Lee BS. Adaptive and maladaptive expression of the mRNA regulatory protein HuR. World J Biol Chem. 2013;4:111–118. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v4.i4.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brennan CM, Steitz JA. HuR and mRNA stability. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:266–277. doi: 10.1007/PL00000854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peng SS, Chen CY, Xu N, Shyu AB. RNA stabilization by the AU-rich element binding protein, HuR, an ELAV protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:3461–3470. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srikantan S, Gorospe M. HuR function in disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:189–205. doi: 10.2741/3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Imada K, Leonard WJ. The Jak-STAT pathway. Mol Immunol. 2000;37:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(00)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carroll CJ, Sayan BS, Bailey SG, McCormick J, Stephanou A, Latchman DS, Townsend PA. Regulation of myocardial interleukin-6 expression by p53 and STAT1. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2013;33:542–548. doi: 10.1089/jir.2012.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fulkerson PC, Zimmermann N, Hassman LM, Finkelman FD, Rothenberg ME. Pulmonary chemokine expression is coordinately regulated by STAT1, STAT6, and IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 2004;173:7565–7574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang C, Li Y, Wu Y, Wang L, Wang X, Du J. Interleukin-6/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway is essential for macrophage infiltration and myoblast proliferation during muscle regeneration. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:1489–1499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.419788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szekely JI, Pataki A. Effects of vitamin D on immune disorders with special regard to asthma, COPD and autoimmune diseases: a short review. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2012;6:683–704. doi: 10.1586/ers.12.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foong RE, Zosky GR. Vitamin D deficiency and the lung: disease initiator or disease modifier? Nutrients. 2013;5:2880–2900. doi: 10.3390/nu5082880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herr C, Greulich T, Koczulla RA, Meyer S, Zakharkina T, Branscheidt M, Eschmann R, Bals R. The role of vitamin D in pulmonary disease: COPD, asthma, infection, and cancer. Respir Res. 2011;12:31. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strum JC, Johnson JH, Ward J, Xie H, Feild J, Hester A, Alford A, Waters KM. MicroRNA 132 regulates nutritional stress-induced chemokine production through repression of SirT1. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:1876–1884. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abdelmohsen K, Pullmann R Jr, Lal A, Kim HH, Galban S, Yang X, Blethrow JD, Walker M, Shubert J, Gillespie DA, Furneaux H, Gorospe M. Phosphorylation of HuR by Chk2 regulates SIRT1 expression. Mol Cell. 2007;25:543–557. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamakuchi M. MicroRNA Regulation of SIRT1. Front Physiol. 2012;3:68. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoesel B, Schmid JA. The complexity of NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:86. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barrios CS, Castillo L, Zhi H, Giam CZ, Beilke MA. Human T cell leukaemia virus type 2 tax protein mediates CC-chemokine expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells via the nuclear factor kappa B canonical pathway. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:92–103. doi: 10.1111/cei.12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nahid MA, Pauley KM, Satoh M, Chan EK. miR-146a is critical for endotoxin-induced tolerance: Implication in innate immunity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34590–34599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nahid MA, Satoh M, Chan EK. MicroRNA in TLR signaling and endotoxin tolerance. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8:388–403. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sinha A, Yadav AK, Chakraborty S, Kabra SK, Lodha R, Kumar M, Kulshreshtha A, Sethi T, Pandey R, Malik G, Laddha S, Mukhopadhyay A, Dash D, Ghosh B, Agrawal A. Exosome-enclosed microRNAs in exhaled breath hold potential for biomarker discovery in patients with pulmonary diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:219–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kazani S, Planaguma A, Ono E, Bonini M, Zahid M, Marigowda G, Wechsler ME, Levy BD, Israel E. Exhaled breath condensate eicosanoid levels associate with asthma and its severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]