Abstract

FDG-PET/CT is rarely used for initial staging of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC). Surgical resection of primary tumor and isolated metastases may result in long-term survival or presumed cure, whereas disseminated disease contraindicates operation. We analyzed a retrospective material to elucidate the potential value of FDG-PET/CT for staging of CRC. Data were retrieved from 67 consecutive patients (24-84 years) with histopathologically proven CRC who had undergone FDG-PET/CT in addition to conventional imaging for initial staging. Treatment plans before and after FDG-PET/CT were compared and patients divided as follows: (A) Patients with a change in therapy following FDG-PET/CT and (B) Patients without a change following FDG-PET/CT. Sixty-two patients had colon and five had rectal cancer. Of these, 20 (30%; CI 20.2-41.7) belonged to group A, whereas 47 (70%; CI 58.3-79.8) fell in group B. In conclusion, FDG-PET/CT changed treatment plan in 30% of cases. In ⅓ of these there was either a change from intended curative to palliative therapy or vice versa, while in the remaining ⅔ the pattern was more mixed. Thus, even in a retrospective routine material there were substantial changes in management strategy following FDG-PET/CT for staging in CRC.

Keywords: FDG-PET/CT, colorectal cancer, clinical impact, treatment strategy

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in both men and woman in Scandinavia. The overall relative 5-year survival is about 50%-60% but is highly dependent on disease stage at the time of diagnosis ranging from approximately 80% to only 3% [1,2]. Curative treatment comprises resection of the primary tumour combined with adjuvant chemotherapy in selected patients. In recent years there has been an increasing role for curative intended surgical or ablative intervention in limited metastatic disease, i.e., solitary or few metastases to the liver and/or the lungs. Accurate preoperative staging is of paramount importance for directing the most appropriate therapeutic options, for indicating prognosis and outcome, and to avoid futile operations. However, no definite consensus on optimal imaging strategy for staging has been established [1]. More specific and sensitive methods are needed.

According to guidelines, a multimodality approach including CT, MRI (rectal cancer only), and ultrasonography including endoscopic ultrasonography should be employed in the diagnostic work up of colorectal cancer patients. In 2004, a cancer service guideline from the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence on ‘Improving outcomes in colorectal cancer’, positron emission tomography (PET) with 18-fluor-labeled fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) was suggested as “an emerging technology that may prove useful” [1]. Since then, standalone PET scanners has largely been replaced by scanners combining PET and computed tomography (PET/CT), and although there is an increasing amount of evidence of the incremental value of PET/CT in a multitude of solid tumours, no definitive work has emerged concerning colon cancer [2].

The literature on the clinical use of FDG-PET/CT in colorectal cancer staging is fairly limited, but recent works have demonstrated some promise for optimizing the accuracy of initial staging by clarifying equivocal findings on conventional imaging in preoperative staging, and evaluating apparently limited metastatic disease before intervention [1,3].

The liver is the most common site of metastases in colorectal cancer with up to 25% of patients presenting with hepatic involvement at initial diagnosis. If liver metastases are left untreated median survival is around 6 months, but 5-year survival as high as 50% can be achieved by metastatectomy and peri-operative chemotherapy in patients with limited metastatic disease suitable for resection. However, high relapse rates and the fact that as many as half of the patients initially deemed resectable turn out non-resectable at laparotomy makes increasing accuracy of staging desirable to avoid potential morbidity of unnecessary surgery [1,3]. In recent years, systematic reviews and metaanalyses have shown FDG-PET/CT to be more sensitive than CT alone in detecting extra-hepatic disease, thus avoiding futile surgery, but in general the literature is limited and heterogeneous. Patel et al. assessed staging in general and found sensitivities and specificities regarding extra-hepatic metastases of 75-89% and 95%, respectively, while corresponding values for CT were 58-64% and 87-97%, respectively. For liver metastases, sensitivities and specificities were 91-100% and 75-100%, respectively versus 78-94% and 25-98%, respectively, for CT [4]. With regards to lymph node metastases, a recent metaanalysis found sensitivity and specificity of 43% and 88%, respectively, and the authors recommend PET/CT as supplement to other modalities with equivocal findings [5]. Finally, two metaanalyses have assessed liver metastases and found sensitivities of 81-86% (on a per-lesion basis) and 94% (on a per-patient basis), which was better than MR (80-88%) and CT (74-84%), with similar specificities around 94% [4,6].

However, in order for these results to be of value to the patients they need to translate into beneficial changes in management, e.g. avoidance of futile surgery. Thus, the aim of this retrospective survey was to determine the effect of FDG-PET/CT-scan in patients with newly diagnosed CRC, i.e. to establish whether the scan had any impact on the initially planned treatment strategy suggested by conventional staging methods.

Materials and methods

All patients with newly diagnosed CRC, in whom both FDG-PET/CT and conventional methods were performed for initial staging during the period from 2006 to 2012, were included retrospectively. The primary diagnoses of the patients were confirmed by histopathology, either by biopsy or examination of surgery specimen. The medical records of the enrolled patients were analyzed in order to extract the necessary information about gender and age, as well as the results from the FDG-PET/CT, CT, MR and/or ultrasound scans performed in the staging process. Furthermore, the intended treatment before FDG-PET/CT and the actual treatment strategy after the FDG-PET/CT were recorded and alterations were highlighted. Patients were followed-up to evaluate if results from imaging were reliable.

Overall, the patients were categorized into two major groups based on the results of this analysis, i.e. one (A) in which there was a change in treatment after FDG-PET/CT result became available, and another (B) in which there was no recordable change following PET/CT. The two groups were subsequently divided into subgroups according to Table 1.

Table 1.

Categorization of patient groups and subgroups according to changes in management

| A. Patients in whom the treatment strategy was changed as a consequence of the results of the PET/CT scan. | Subgroup 1 |

| Treatment was changed from palliative to intended curative strategy. | |

| Subgroup 2 | |

| Treatment was changed from intended curative to palliative strategy. | |

| Subgroup 3 | |

| Miscellaneous changes in treatment strategy. | |

|

| |

| B. Patients in whom the treatment strategy was not changed as a consequence of the results of the PET/CT scan. | Subgroup 1 |

| PET/CT confirmed previous findings by conventional methods. | |

| Subgroup 2 | |

| PET/CT showed either additional or less lesions, but did not impact on treatment strategy. | |

The FDG-PET/CT examinations were performed on a GE Discovery STE PET/CT. The CT part was performed as a diagnostic scan with intravenous and oral contrast. Data were reconstructed with a standard filter into transaxial slices with a field of view of 50 cm, matrix size of 512 × 512 (pixel size 0.98 mm) and a slice thickness of 3.75 mm. The CT scan was followed immediately by a PET scan performed using a standard whole-body acquisition protocol with 6 or 7 bed positions and an acquisition time of 2½ minutes per bed position. The scan field of view was 70 cm. Attenuation correction was performed from the CT-scan. The PET data were reconstructed into transaxial slices with a matrix size of 128 × 128 (pixel size 5.47 mm) and a slice thickness of 3.75 mm using iterative 3D OS-EM (2 iterations, 28 subsets), and displayed in coronal, transverse and sagittal planes. Corrections for attenuation, randoms, dead time and normalization were done inside the iterative loop. Analysis of the PET and fused PET/CT data was done using a GE Advantage Workstation v. 4.4. The fused PET/CT scan was described jointly by a nuclear medicine specialist and a radiologist. At the time of FDG administration all patients had fasted for at least 6 hours. PET/CT image acquisition commenced 60 ± 5 min. after the administration of a weight adjusted dose of 4 MBq/kg (110 µCi/kg) FDG (min. 200 MBq (5 mCi) and max. 400 MBq (10 mCi).

Results

A total of 67 patients were included, i.e., 29 males and 38 females, aged 24 to 84 years (mean 67), with a novel diagnosis of CRC, who underwent an additional FDG-PET/CT as part of their initial staging procedure during the period 2006-2012 (both years inclusive). Five patients had rectal and 62 had colon cancer. The patients all underwent a conventional CT and/or MR scan, except for one, who only was staged with ultrasound, before the additional FDG-PET/CT scan. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, the FDG-PET/CT scans were performed as per the treating physicians’ discretion and hence varied with regards to timing; the median and mean time period from diagnosis to FDG-PET/CT scans were 24 days and 31 days, respectively (range 2-97).

The patients in whom the treatment strategy was changed are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patients in whom treatment strategy was changed as a consequence of the results of the FDG-PET/CT

| Patient | Intended treatment strategy before FDG-PET/CT | Actual treatment after FDG-PET/CT | Imaging findings | Follow-up of the validation of FDG-PET/CT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in treatment strategy from intended curative to palliative strategy | ||||

| 01 | No treatment | Palliative chemotherapy | CT: Liver cyst | Subsequent CT-control and PET/CT showed progressive disease |

| PET/CT: Pleural metastases and peritoneal seeding | ||||

| 02 | Sigmoideum resection | Palliative chemotherapy | CT: No evidence of metastases. Referred to PET/CT because of lung infiltrates deemed benign by CT | CT confirmed the findings and showed progression in the lung/liver |

| PET/CT: liver/lung metastases | ||||

| 03 | Resection of rectal tumor and liver metastasis | Palliative chemotherapy | MR: One liver metastasis | CT confirmed the findings and showed progression in the liver |

| PET/CT: Multiple liver metastases | ||||

| Change in treatment from palliative to intended curative strategy | ||||

| 04 | Palliative chemotherapy | No treatment | CT: Multiple lung metastases | 9 month after the PET/CT a CT-control scan showed novel liver metastasis and a novel primary lung cancer. Biopsy confirmed small cell lung cancer |

| PET/CT: No metastases | ||||

| 05 | Palliative chemotherapy | No treatment | CT: Liver metastases | No recurrence at 1-year follow-up |

| PET/CT: No FDG-uptake (suggested liver hemangiomas) | ||||

| 06 | Palliative chemotherapy | Curative liver metastasis resection | CT: Liver and distant lymph nodes metastases | Examination of liver surgery specimen showed metastasis |

| PET/CT: A single liver metastasis | ||||

| Miscellaneous changes in treatment strategy | ||||

| 07 | Curative liver resection | No treatment | CT: Liver metastasis | Biopsy from liver cyst: no metastasis. CT-control showed no recurrence |

| PET: No liver foci | ||||

| 08 | A not clarified treatment strategy (a date for laparoscopic hemicolectomy was booked) | Lung metastatectomy | CT: Metastasis-like osteolytic bone lesion, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes and equivocal liver foci | EBUS showed no evidence of lymph node metastases |

| PET/CT: One lung metastasis and suspicious lymph nodes in mediastinum | Lung metastatectomypperformed and confirmed malignancy | |||

| 09 | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and resection of pulmonary metastasis in both lungs | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and resection of pulmonary metastasis in one lung | CT: Bilateral lung metastases | VATS segmentectomy: Adenocarcinoma |

| PET/CT: One lung metastasis | ||||

| 10 | Resection of liver metastasis | No treatment | CT: Liver metastasis | No recurrence at 1 year follow-up |

| PET/CT: No liver foci | ||||

| 11 | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and resection of liver metastases | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Resection of liver metastases and synchronous colon cancer | CT/MR: Liver metastases | Hepatectomy and colectomy. Biopsies showed moderate dysplasia in colon and adenocarcinoma in the liver |

| PET/CT: Synchronous colon cancer and liver metastases | ||||

| 12 | Resection of liver metastases | Resection of liver metastases. Transsphenoidal hypophysectomy | CT: Liver Metastases | Examination of liver surgery specimen showed metastases |

| PET: Liver metastases and pituitary adenoma | ||||

| 13 | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Resection of liver metastases | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Resection of liver and lung metastases | CT: Liver metastasis | Examination of liver surgery specimen showed metastasis. CT-control after neoadjuvant chemoterapy showed no sign of remaining metastasis in the lung |

| PET/CT: one lung metastasis and one liver metastasis | ||||

| 14 | Resection of liver and lung metastases | No treatment | CT: Liver/lung metastases | No recurrence at 1 year follow-up |

| PET: No metastases | ||||

| 15 | Resection of pulmonary metastasis | No treatment | CT: Equivocal lung foci | No recurrence at 1 year follow-up |

| PET/CT: No metastases | ||||

| 16 | Resection of retrocrural lymph nodes and colectomy | Colectomy | CT: Retrocrural lymph node metastases | No recurrence at 1 year follow-up |

| PET: Retrocrural lymph nodes without FDG-uptake | ||||

| 17 | Palliative chemotherapy | Palliative chemotherapy | CT: Liver metastases | Two fine-needle aspiration biopsies: no malignancy |

| PET: Liver metastases and primary lung cancer | CT showed disease progression | |||

| 18 | Hemicolectomy | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Hemicolectomy and curative resection of primary lung cancer | CT: Pulmonary infiltrates (Previously diagnosed as granulomas) | Refused treatment |

| PET: Pulmonary infiltrates with FDG-uptake -> primary lung cancer | ||||

| 19 | Palliative chemotherapy | Treatment for hematological cancer | CT: Suspicious lymph nodes in the retroperitoneum | Biopsy: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| PET: Multiple lymph nodes with FDG-uptake | ||||

| 20 | Resection of pulmonary metastases | No treatment | CT: Lung metastases | No recurrence at half year follow-up |

| PET: No metastases | ||||

EBUS: Endobronchial ultrasound; VATS: Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Patients with changed treatment strategy

In a total of 20 cases (30%; 95% Wilson-score confidence interval 20.2-41.7%) the proposed treatment strategy was changed as a consequence of the results of the FDG-PET/CT scan. In three patients (~5%), the proposed treatment was changed from a curative aim towards palliation: In one patient the CT scan showed no clear evidence of distant metastases, but the detection of lung metastases and peritoneal seeding by FDG-PET/CT changed the course from surgery to palliative chemotherapy (Figure 1). In two patients, the intended treatment was resection of a primary colon tumor alone, and resection of a rectum tumor together with limited liver metastases, respectively. These strategies were, however, abandoned and changed to palliative chemotherapy after FDG-PET/CT had detected liver and lung metastases in one patient (Figure 2), and multiple liver metastases in the other. In these patients, the additional findings by FDG-PET/CT were not confirmed by biopsy, but subsequent imaging (i.e. CT or follow FDG-PET/CT) confirmed the findings initially and in turn demonstrated progressive disease.

Figure 1.

Colon cancer. No metastases in preoperative imaging, but during surgery tumor tissue was removed from the peritoneum. FDG-PET/CT scan was performed with regards to residual disease. MIP PET image (A) and fused axial PET/CT images (B &; C) show multiple peritoneal metastases (red arrows) and pleural metastases (green arrows).

Figure 2.

Sigmoid cancer. Peroperatively suspicious lever lesions but CT equivocal with no obvious metastases. FDG-PET/CT was performed to clarify stage post-operatively. MIP PET image (A) and fused axial PET/CT images (B &; C) show multiple liver metastases (green arrows) and lung metastases (red arrows).

FDG-PET/CT also resulted in a change from palliative to curative treatment in 3 patients (~5%). One patient had multiple lung metastases on CT, but none at all on FDG-PET/CT. Because of symptoms of bowel obstruction a rectum resection was performed prior to the scans, and based on the CT scan the patient was candidate for postoperative, palliative chemotherapy. However, according to the FDG PET/CT scan, no subsequent treatment was necessary, and the FDG-PET/CT could classify the patient as cured. In another patient, liver metastases described on CT were not identified by FDG-PET/CT. The conclusion regarding the abnormal liver tissue was hemangiomas, and, thus, palliative chemotherapy was no longer indicated. The last patient was intended for curative liver metastatectomy, but the CT scan was suggestive of distant lymph node metastases, and palliative chemotherapy was planned instead. However, although FDG-PET/CT also found enlarged distant lymph nodes, they were without pathologic FDG-uptake, and the patient underwent curative resection of liver metastases after all.

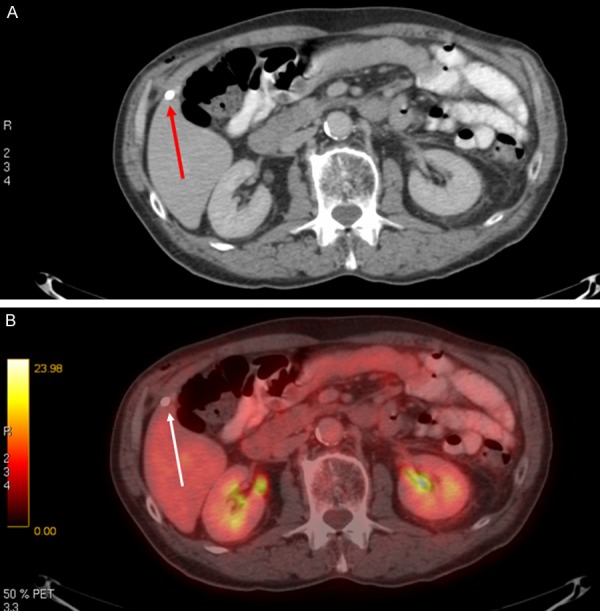

In the remaining 14 of the 20 cases, FDG-PET/CT changed the planned treatment modality with regard to the extent of curative intended therapy, but not from palliative to curative treatment or vice versa. Seven of the 14 patients received less treatment than initially planned: Six patients had limited metastatic disease according to CT, i.e. isolated liver metastasis (n=2), isolated lung metastasis (n=2), isolated lung and liver metastases (n=1), and limited distant lymph node metastases (n=1). Curative metastatectomy was proposed in all six, but FDG-PET/CT revealed no dissemination in any of these patients, and thus, the treatment strategy was changed to resection of the primary tumor alone (Figure 3). The seventh patient was operated upfront but a postoperative staging CT was suspicious for lung metastasis. However, the patient was deemed disease free by FDG-PET/CT, and the proposed neoadjuvant chemotherapy and metastatectomy was abolished.

Figure 3.

Sigmoid cancer. Suspicious liver lesion per-operatively and on pre-operative CT (red arrow). FDG-PET/CT was performed to clarify the finding. Axial CT image (A) shows the lesion in question (red arrow), and fused axial PET/CT image (B) shows no uptake (white arrow) consistent with non-malignant lesion.

In three of the 14 patients therapy was extended: In one patient, the CT scan indicated a liver metastasis, but FDG-PET/CT showed a lung metastasis too. Hence, the planned treatment (curative liver metastasectomy) was expanded to also include a lung metastatectomy. In another patient, preoperative CT showed an osteolytic lesion suspicious of bone metastasis, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, and an equivocal liver lesion. An FDG-PET/CT scan was recommended and showed a lung metastasis, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes of uncertain significance, but no bone or liver metastases. The primary tumor had been removed 17 days before the FDG-PET/CT scan because of stenosis, and a subsequent treatment strategy was not planned prior to the PET/CT scan. Afterwards a lung metastatectomy was planned. The third patient had a synchronous tubulo-villous adenoma with moderate dysplasia revealed by FDG-PET/CT, but not by CT. A colonoscopy was not sufficient because of an obstructing lesion in the colon, and the patient subsequently underwent extended colon surgery.

Finally, in the last four of the 14 patients, FDG-PET/CT detected important comorbidity not detected by CT; two synchronous lung cancers, one synchronous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and one pituitary adenoma. The treatment strategy was adjusted accordingly toward these diseases.

To evaluate and verify the results of the FDG-PET/CT scans a retrospective follow-up of one year was performed in all patients. Generally the FDG-PET/CT scan showed a high accuracy. In three cases it remained unclear whether the result from the FDG-PET/CT was correct. In one patient FDG-PET/CT raised suspicion of a primary lung cancer, but two fine-needle aspirations showed no malignant cells. The treatment strategy for this patient remained palliative chemotherapy due to liver metastases. The following CT showed disease progression. In another patient who was considered disease-free by FDG-PET/CT 9 months earlier, a control CT showed liver metastases and a new primary lung cancer. Regarding the third patient, the FDG-PET/CT showed a single lung metastasis and suspicious lymph nodes in the mediastinum, whereas a subsequently performed endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) showed no metastases to lymphatic nodes. Due to worsening of the general condition and high age of the patient (84 years), the EBUS was not followed by the initially planned treatment.

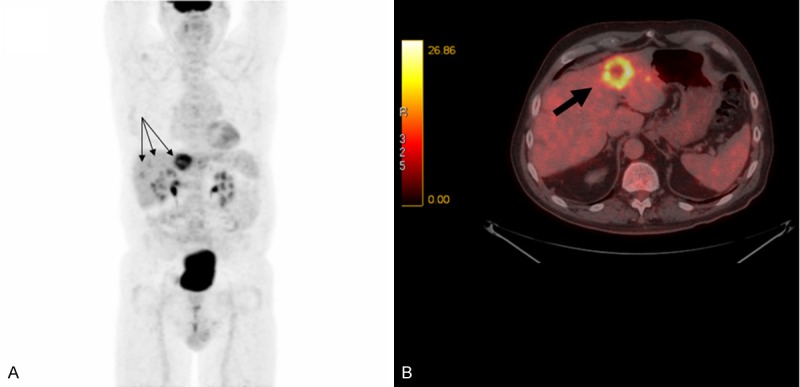

Patients with unchanged treatment strategy

In 47 of the cases (70%; 95% Wilson-score confidence interval 58.3-79.8%), the planned treatment strategy did not change after the FDG-PET/CT scan. In 40 of these cases, the results were in accordance with results of the conventional imaging,showing neither less nor additional lesions (Figure 4). In the remaining 7 cases, the PET/CT showed either additional or less lesions compared to conventional workup, but the results did not impact the planned treatment strategy. These cases are explored further in the following paragraphs.

Figure 4.

Colon cancer. Preoperative imaging (including FDG-PET/CT) raised suspicion of liver metastases. MIP PET image (A) and fused axial PET/CT image (B) show liver metastases (black arrows), which were confirmed by surgery. FDG-PET/CT findings were consistent with conventional imaging and did not cause any change in management.

In the first two of the seven patients, CT showed lung metastases, but PET/CT did not corroborate these findings. However, because of peritoneal seeding in one patient, and non-resectable liver metastases in the other (both findings appreciated on CT), these two patients was scheduled for palliative chemotherapy before the FDG-PET/CT scan and this strategy was not changed by the findings mentioned. The peritoneal seeding was confirmed by cytology from ascitic fluid. Similarly, the third of the seven patients was preoperatively staged with ultrasound only and there was evidence of multiple liver metastases. FDG-PET/CT subsequently detected lung metastases as well, but the finding had no impact on the planned palliative treatment.

In the fourth patient, CT identified a suspicious paratracheal lymph node in the mediastinum, but the finding was equivocal in determining whether it was metastatic or not. Subsequent FDG-PET/CT was not suggestive of malignancy in this lymph node, but found increased metabolism in four axillary lymph nodes, an atypical location for CRC metastases. A biopsy showed normal tissue. Due to an acute bowel obstruction, a sigmoideum resection was performed before the FDG-PET/CT. As the patient in question also had a kidney-graft, treatment with chemotherapy was not possible.

In the fifth patient, PET/CT revealed liver and iliac lymph node metastases, but because of synchronous multiple myeloma this did not impact the treatment strategy. Finally, the last two of the seven patients had CT confirmed liver metastases, and FDG-PET/CT showed involvement of further liver segments, but this did not change the plan (chemotherapy and a succeeding re-evaluation of the metastases).

Discussion

This study is one of the first to report the impact of FDG-PET/CT on intended treatment of newly diagnosed CRC compared to conventional staging methods. The use of FDG-PET/CT changed the planned treatment strategy in a total of 30% of the patients. A change from palliative to curative or vice versa was seen in almost 10% of the patients. These results are in accordance with the limited literature published (Table 3).

Table 3.

Overview of comparable studies

| Author | Year | n | Study design | Modality | Changes due to PET imaging |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park et al. [8] | 2006 | 100 | Prospective | FDG-PET/CT | Change in management in 24% |

| Davey et al. [9] | 2008 | 83 | Prospective | FDG-PET/CT | Change in management intent in 8% |

| Change in overall management in 12% | |||||

| Re-staging in 31% | |||||

| Cipe et al. [10] | 2013 | 64 | Prospective | FDG-PET/CT | Change in surgical management in 3.2% |

| Re-staging in 21% | |||||

| Llamas-Elvira et al. [11] | 2007 | 104 | Prospective | FDG-PET | Change in therapy in 50% of nonresectable patients |

| Re-staging in 13% | |||||

| Modified scope of surgery in 12% | |||||

| Heriot et al. [12] | 2004 | 46 | Prospective | FDG-PET | Change of management in 17% |

| Change in disease stage in 39% |

Change in intended treatment has been found to occur in up to 24% in a similar study by Park et al. [7]. This prospective study included patients with preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen >10 ng/mL as well as patients in whom CT had showed equivocal findings. However, these inclusion criteria resulted in a selection of patients with more severe disease.

In our study, the included patients were either diagnosed with suspected metastases or had inconclusive results regarding the existence of metastases by conventional staging methods. Like in the study by Park et al. this may have resulted in a selection bias, albeit towards a more intermediate - or difficult - population since both patients with obvious or severely disseminated disease or patients with little or no suspicion of disseminated disease probably were not included.

Another study from 2013 by Cipe et al. [8] reported a change in the surgical management in only 3.2% of the participants based on FDG-PET/CT findings and the authors concluded that FDG-PET/CT should not be routinely used for primary staging of CRC. However, they included CRC patients regardless of stage, and generally approximately 3/4 of newly diagnosed patients have only limited disease. The treatment strategy for patients with only limited disease is often intended curative surgery. The potentially large proportion of patients with limited disease in Cipe et al.’s study may have an impact on the number of patients benefitting from a FDG-PET/CT scan, since the treatment strategy may remain unchanged for many. Furthermore, only the change in surgical treatment was evaluated by Cipe et al., and in fact disease stage per se was changed in 21% based on FDG-PET/CT which may have resulted in changes in oncologic treatment due to up- or downstaging. However, this was considered outside the aim of their study. Thus, while our study reflects current use of FDG-PET/CT in Denmark, Cipe et al. investigated FDG-PET/CT in routine use in all CRC patients. As a consequence, their and our results are not directly comparable.

The impact of FDG-PET/CT on planned treatments suggested by conventional imaging techniques in patients with recently diagnosed rectal cancer, was evaluated by Davey et al. [9]. FDG-PET/CT resulted in a change in treatment of 14% of the patients. The study included 83 patients referred to a tertiary oncology center from January 2002 to November 2005. It is presumed that the study population included patients with all stages of CRC, although this was not clearly stated. Their results can be compared with the results of Cipe et al., but again, several differences in design separate them from us. First, they only used stand-alone PET. Second, Davey et al. only reported “high impact” changes, e.g. changes in surgical strategy, whereas “medium impact” changes, e.g. changes in radiation field or -dose, were not addressed.

Similarly, Llamas-Elvira et al. [10] found changes in the surgical treatment in 12% of colon cancer patients and 17% of rectal cancer patients following FDG-PET. Their data were collected in 2002 and 2003 and were thus based on stand-alone FDG-PET rather than FDG-PET/CT. Furthermore, the conventional staging consisted of a plain chest X-ray, an abdominal CT in colon cancer cases and abdominopelvic CT in rectal cancer cases. These initial staging methods are now obsolete as well, but the changes in treatment as a consequence of FDG-PET confirm the advantage of FDG-PET as a tracer of cancer in the staging process. They did, however, show FDG-PET to cause a change in the therapy approach in 50% of patients with non-resectable disease, revealing unknown disease in 19%, and changing the overall stage in 13%.

Another stand-alone FDG-PET study by Heriot et al. [11] compared FDG-PET to conventional imaging in the initial staging of primary advanced rectal cancer. The results showed a change in the original management in 17% of the patients. In 13%, there was a change from intended curative to palliative. Overall, the stage was changed in 39% following FDG-PET.

In the present study, the finding of a change in the planned treatment strategy in 30% of the patients establishes FDG-PET/CT as a beneficial clinical tool in the staging of CRC patients in whom the results of conventional staging methods are equivocal. Focus in this study was upon the way and to which extent the use of FDG-PET/CT scans affected the planned treatment strategy.

When dealing with medical imaging, patient exposure to ionizing radiation should always be considered. Adding an FDG-PET/CT scan to the diagnostic workup does add to the effective dose the patient receives. The effective dose from FDG-PET/CT comprise the dose from the injected radiotracer FDG, which is ~5 mSv, and the dose of the CT, which is ~1-2 mSv for a low dose CT without contrast and ~8 mSv for a diagnostic CT with contrast. Thus, total effective dose from an FDG-PET/CT scan is in the range of ~7-15 mSv [12]. This should be compared to the 2-3 mSv average annual background radiation in Denmark and to the effective dose of the conventional imaging strategy employed in CRC, i.e. diagnostic CT of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, which exposes the patient to 10-15 mSv each. Adding an FDG PET/CT to the diagnostic workup of CRC may thus give rise to additional radiation exposure, but one might also argue that the radiation burden would be less if FDG PET/CT were to substitute conventional imaging. That said, the consequences to the patients from these exposures are - according to the American Association of Physicists in Medicine - no longer considered an issue (http://www.aapm.org/org/policies/details.asp?id=318&;type=PP) and the potential, and to a large extend theoretical, risk should be seen in relation the severe risks of futile surgery or unwarranted chemotherapy that might be thwarted by the use of FDG-PET/CT.

Limitations

All data were collected from past medical records. In some cases, the information available was limited or ambiguous. Data regarding planned treatment strategy and conclusions of initial staging was collected from multidisciplinary cancer conferences (MCCs) before and after the FDG-PET/CT scan. In case of no MCCs, or when the necessary conclusions were impossible to draw based on MCCs, an assessment from a chief physician was used instead. By this approach an attempt was made to minimize the possible analytical bias in our study.

To make a well-founded comparison of the results from different studies it is important to know details about the study population. In the present study, the included patients were either suspected of metastases or had inconclusive results regarding the existence of metastases based on conventional staging methods.

In most of the included cases, the performed FDG-PET/CT was required by the referring physicians with regards to an assessment of possible dissemination of the CRC. However, in 12 cases FDG-PET/CT was part of a research project in which CRC patients with liver metastases were evaluated. The use of FDG-PET/CT in this particular project may not necessarily reflect either the national guidelines regarding the use of FDG-PET/CT nor clinical practice. As a result, the total number of patients referred for FDG-PET/CT cannot be categorized as a homogeneous group. This makes comparison with other studies problematic.

To evaluate the full effect of the FDG-PET/CT scan, the treatment should, if possible, not be initiated before the FDG-PET/CT scan. In 39 of the cases, a resection of the primary tumor was performed before FDG-PET/CT imaging. In a number of these patients, the reason for surgical management before the initial staging was acute bowel obstruction. Regarding the rest of the patients the explanation could be the fact that clinical management changes rapidly. Surgical removal of the primary colorectal tumor and postoperative staging was the preferred strategy only a couple of years ago and many of the patients were diagnosed at that time.

Regarding the three cases in which it remained unclear whether the result from the FDG-PET/CT was correct (patients no. 4, 8 and 17 in Table 2), possible explanations could be errors in the biopsy and for patient no. 4 a recurrence of the CRC in the liver and a new onset of lung cancer.

Conclusion

The use of FDG-PET/CT changed the planned treatment strategy in a total of 30% of the patients. This result confirms that FDG-PET/CT has an important role in the staging of the category of patients for whom the guidelines of the DCCG recommend an FDG-PET/CT scan. From the result of this study, is it not possible to conclude whether the routine use of FDG-PET/CT in the initial staging of CRC should be recommended. This was mainly due to the fact that the study population did not reflect all patients hospitalized with CRC.

References

- 1.Chouwhury FU, Shah N, Scarsbrook AF, Bradley KM. [18F] FDG PET/CT imaging of colorectal cancer: a pictorial review. Postgrad Med J. 2010;86:174–182. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2009.079087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Manual update. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2004. Improving outcomes in colorectal cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poeppel TD, Krause BJ, Heusner TA, Boy C, Bockisch A, Antoch G. PET/CT for the staging and follow-up of patients with malignancies. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70:382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Floriani I, Torri V, Rulli E, Garavaglia D, Compagnoni A, Salvolini L, Giovagnoni A. Performance of Imaging Modalities in Diagnosis of Liver Metastases From Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31:19–31. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel S, McCall M, Ohinmaa A, Bigam D, Dryden DM. Positron emission tomography/computed tomographic scans compared to computed tomographic scans for detecting colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2011;253:666–671. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31821110c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu YY, Chen JH, Ding HJ, Chien CR, Lin WY, Kao CH. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pretherapeutic lymph node staging of colorectal cancer by 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT. Nucl Med Commun. 2012;33:1127–1133. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328357b2d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niekel MC, Bipat S, Stoker J. Diagnostic imaging of colorectal liver metastases with CT, MR imaging, FDG PET, and/or FDG PET/CT: a meta-analysis of prospective studies including patients who have not previously undergone treatment. Radiology. 2010;257:674–684. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park J, Kim HC, Yu C, Ryu M, Chang H, Kim JH, Ryu J, Yeo J, Kim JC. Efficacy of PET/CT in the accurate evaluation of primary colorectal carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:941–947. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cipe G, Erguk N, Hasbahceci M, Firat D, Bozkurt S, Memmi N, Karateoe O, Muslumanoglu M. Routine use of positron-emission tomography/computed tomography for staging of primary colorectal cancer: Does it affect clinical management. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:49. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davey k, Heriot A, Mackay J, Drummond E, Hogg A, Ngan S, Milner A, Hicks R. The impact of 18-flourodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography on the staging and management of primary rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:997–1003. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Llamas-Elvira JM, Rodríguez-Fernández A, Gutiérrez-Sáinz J, Gomez M, Bellon-Guardia M, Ramos-Front C, Rebollo-Aguirre A, Cabello-Gareía D, Ferrón-Orihuela A. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET in the preoperative staging of colorectal cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:859–867. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heriot A, Hicks R, Drummond E, Keck J, Mackay J, Chen F, Kalff V. Does positron emission tomography change management in primary rectal cancer? A prospective assessment. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:451–458. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murano T, Minamimoto R, Senda M, Uno K, Jinnouchi S, Fukuda H, Iinuma T, Tsukamoto E, Terauchi T, Yoshida T, Oku S, Nishizawa S, Ito K, Oguchi K, Kawamoto M, Nakashima R, Iwata H, Inoue T. Radiation exposure and risk-benefit analysis in cancer screening using FDG-PET: results of a Japanese nationwide survey. Ann Nucl Med. 2011;25:657–666. doi: 10.1007/s12149-011-0511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]