Abstract

Although oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) as measured by the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) is thought to be multidimensional, the nature of these dimensions is not known. The aim of this report was to explore the dimensionality of the OHIP using the Dimensions of OHRQoL (DOQ) Project, an international study of general population subjects and prosthodontics patients. Using the project's Learning Sample (N=5,173), we conducted an exploratory factor analysis on the 46 OHIP items not specifically referring to dentures for 5,146 subjects with sufficiently complete data. The first eigenvalue (27.0) of the polychoric correlation matrix was more than ten times larger than the second eigenvalue (2.6), suggesting the presence of a dominant, higher-order general factor. Follow-up analyses with Horn's parallel analysis revealed a viable second-order, four-factor solution. An oblique rotation of this solution revealed four highly correlated factors that we named Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact. These four dimensions and the strong general factor are two viable hypotheses for the factor structure of the OHIP.

Keywords: Oral health-related quality of life, Oral Health Impact Profile, dimensions, factor structure, exploratory factor analysis

Introduction

The Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) (1) is currently the most widely used oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) questionnaire. When interpreting OHIP scores, researchers and clinicians implicitly assume that scores adequately reflect the latent construct OHRQoL, that is, that the OHIP is a valid measure of OHRQoL. One aspect of this validity is structural validity, which posits that the number and type of scores provided by the OHIP correspond to the theoretical structure of OHRQoL. Structural validity must be evaluated empirically, usually in an iterative process involving revisions to both theory and the questionnaire. Although the OHIP was originally composed of seven distinct subscales (1), this structure of OHRQoL has been consistently rejected in subsequent investigations.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is a statistical technique often used to generate hypotheses about the latent structure of a data set. Previous EFAs have yielded conflicting results for the OHIP. When the 49-item version was investigated, four factors were identified in the German general population (2) and in Australian older adults (3). When a 30-item OHIP was studied, six factors were identified in Italian patients with temporomandibular disorders (4). With a 19-item instrument (5), four factors were reported in Brazilian edentulous patients (6) and with 18 items four factors were identified in Japanese workers (7). With the 14-item instrument (3), four factors were found in Chinese community subjects (8); three factors were found in Turkish patients with Behcet's disease and recurrent aphthous stomatitis (9) and in Chinese partially dentate patients with implant-supported prostheses (10). Finally, a one-factor solution was identified in Brazilian post-partum women and older adults (11).

The variability of previous findings is likely the result of several influences. First, there are vast differences in the studied populations; patients and general population subjects and individuals from different countries may not perceive the structure of OHRQoL in the same way. Secondly, OHIP forms of varying lengths were used in each study and various data analytic approaches were applied. Thirdly, we would expect sampling error in previous results, especially in studies with small sample sizes. Finally, factor analysis – like any other statistical technique – relies on the analyst to interpret results. This subjectivity can influence how many factors are extracted from the data and how these factors are named and interpreted.

To conclusively determine the structure of the OHIP, a large sample of important target populations should be studied, for example, dental patients and general population subjects. Because the OHIP is used globally, study data should come from different countries. Finally, because an instrument with more items is better able to identify dimensions, the long OHIP-49 is more appropriate for a factor analytic study than the abbreviated versions. The Dimensions of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (DOQ) Project was designed to have such a large set of international OHIP-49 data (12).

The aim of this report was to investigate OHIP's factor structure with EFA in the DOQ Project.

Materials and methods

Study design, subjects and OHIP data

The study was a secondary data analysis. Data came from the Dimensions of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (DOQ) Project (12). The project contains 49-item OHIP (1) data from general population subjects and prosthodontics patients of six countries with validated OHIP instruments (13-18). As part of the DOQ Project, we assigned OHIP responses to one of three data sets (12). The present study used the Learning Sample, containing 5,173 subjects (3,177 general population subjects and 1,996 prosthodontics patients.) We studied the 46 OHIP items that did not refer to dentures specifically. Some subjects had a large number of missing responses such that an accurate characterization of an individual's OHRQoL status was compromised. Therefore, as in previous studies (19), OHIPs with five or more missing responses were omitted from the analysis. In the 5,146 remaining subjects, missing responses were imputed with the person's median response.

Each OHIP item describes a situation that impacts OHRQoL and asks subjects to rate how often they experienced that impact within a certain recall period, most often the last month (response categories ‘never’, ‘hardly ever’, ‘occasionally’, ‘fairly often’, and ‘very often’). More details about OHIP and the levels of impaired OHRQoL in prosthodontics patients and general population subjects are provided in the overview about the DOQ Project (12).

Data analysis

We investigated the dimensionality of the OHIP through an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of inter-item polychoric correlations. We determined dimensionality by considering the ratio of the first-to-second eigenvalue (20), Cattell's scree plot (21), and Horn's parallel analysis (22). It has been suggested that a ratio of first-to-second eigenvalues greater than four is evidence of unidimensionality (23). Cattell's method plots the eigenvalues in decreasing order and retains as many factors as there are eigenvalues above the elbow of the plot. Horn's parallel analysis modifies Cattell's scree plot by comparing the observed eigenvalues to eigenvalues from random data, retaining as many factors as the number of observed eigenvalues that exceed the simulated eigenvalues.

We extracted factors using the iterated principal factors technique and rotated the solution using oblimin (an oblique rotation technique) (24), leading to correlated factors. Factor solutions were interpreted with salient factor pattern loadings greater than 0.45. Finally, using items assigned uniquely to factors, we present Cronbach's alpha for each factor of our final solution.

In secondary analyses, we investigated whether methodological choices in the factor analysis change results. First, we applied the principal components method instead of the iterated principal factors method. Second, we applied promax (25), another oblique rotation, instead of oblimin rotation.

Results

OHIP's general factor

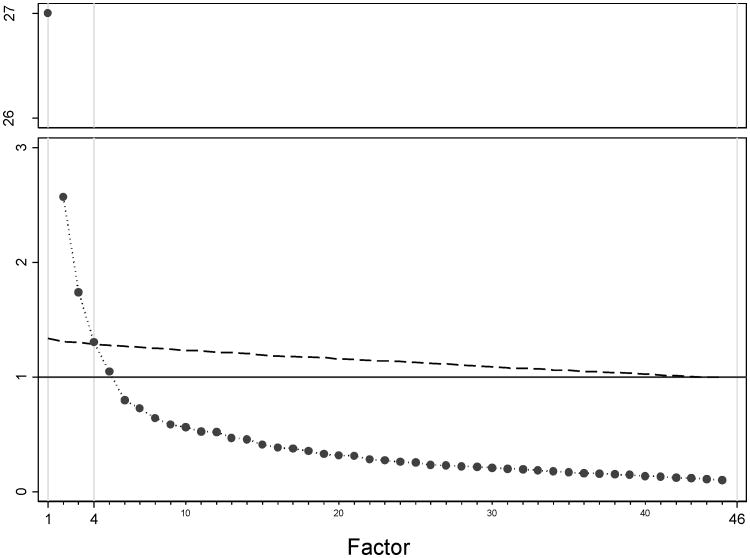

The eigenvalues of the polychoric correlation matrix for the complete data suggested a dominant general factor. The first eigenvalue was 27.0 and the second eigenvalue was 2.6, yielding a first-to-second eigenvalue ratio of 10.5 (Figure 1). The third eigenvalue was 1.7 and the fourth was 1.3. When one factor was extracted, all OHIP items had large loadings with the smallest loading equal to 0.49 (Table 1).

Figure 1. Parallel analysis: Plot of actual (•) versus randomly (---) generated eigenvalues (y-axis range between 3 and 26 not shown).

Table 1. One-factor solution for 46 OHIP items not referring to dentures specifically for all subjects combined, and separately for general population subjects and patients, and subjects in six participating countries.

| OHIP item | All | General Population | Patients | Croatia | Germany | Hungary | Japan | Slovenia | Sweden | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=5146 | N=3152 | N=1994 | N=190 | N=2312 | N=830 | N=622 | N=415 | N=777 | ||

| Loadings* | ||||||||||

| 1. | Difficulty chewing | .76 | .74 | .68 | .51 | .76 | .77 | .76 | .75 | .75 |

| 2. | Trouble pronouncing words | .76 | .75 | .69 | .63 | .76 | .69 | .74 | .81 | .77 |

| 3. | Noticed tooth which doesn't look right | .59 | .56 | .54 | .06 | .60 | .62 | .57 | .55 | .76 |

| 4. | Appearance affected | .71 | .68 | .66 | .40 | .76 | .60 | .71 | .72 | .76 |

| 5. | Breath stale | .59 | .60 | .53 | .47 | .60 | .58 | .57 | .61 | .54 |

| 6. | Taste worse | .74 | .76 | .67 | .62 | .73 | .64 | .73 | .76 | .73 |

| 7. | Food catching | .55 | .49 | .50 | .47 | .54 | .55 | .55 | .52 | .52 |

| 8. | Digestion worse | .75 | .76 | .72 | .58 | .71 | .76 | .79 | .80 | .72 |

| 10. | Painful aching | .71 | .71 | .63 | .56 | .74 | .69 | .69 | .68 | .72 |

| 11. | Sore jaw | .66 | .70 | .54 | .68 | .71 | .69 | .55 | .60 | .70 |

| 12. | Headaches | .61 | .62 | .61 | .65 | .72 | .60 | .69 | .69 | .51 |

| 13. | Sensitive teeth | .49 | .50 | .48 | .06 | .58 | .47 | .49 | .46 | .52 |

| 14. | Toothache | .62 | .64 | .57 | .12 | .63 | .69 | .65 | .62 | .70 |

| 15. | Painful gums | .65 | .63 | .58 | .41 | .66 | .57 | .66 | .60 | .72 |

| 16. | Uncomfortable to eat | .80 | .79 | .75 | .57 | .81 | .83 | .83 | .83 | .80 |

| 17. | Sore spots | .65 | .66 | .58 | .50 | .67 | .66 | .67 | .63 | .72 |

| 19. | Worried | .74 | .68 | .73 | .69 | .78 | .68 | .75 | .77 | .78 |

| 20. | Self-conscious | .78 | .78 | .73 | .52 | .81 | .85 | .77 | .61 | .87 |

| 21. | Miserable | .84 | .86 | .79 | .71 | .84 | .84 | .80 | .81 | .91 |

| 22. | Uncomfortable about appearance | .82 | .82 | .76 | .69 | .80 | .89 | .72 | .78 | .87 |

| 23. | Tense | .83 | .84 | .80 | .72 | .83 | .88 | .85 | .86 | .83 |

| 24. | Speech unclear | .80 | .80 | .73 | .65 | .81 | .73 | .80 | .82 | .80 |

| 25. | Others misunderstood | .77 | .77 | .71 | .60 | .80 | .64 | .77 | .74 | .74 |

| 26. | Less flavor in food | .78 | .77 | .74 | .79 | .77 | .65 | .78 | .78 | .78 |

| 27. | Unable to brush teeth | .75 | .76 | .66 | .64 | .77 | .63 | .68 | .73 | .79 |

| 28. | Avoid eating | .78 | .79 | .71 | .55 | .80 | .74 | .73 | .82 | .83 |

| 29. | Diet unsatisfactory | .84 | .84 | .80 | .74 | .86 | .82 | .80 | .87 | .81 |

| 31. | Avoid smiling | .80 | .80 | .76 | .68 | .81 | .80 | .80 | .86 | .81 |

| 32. | Interrupt meals | .82 | .84 | .75 | .65 | .82 | .79 | .83 | .86 | .91 |

| 33. | Sleep interrupted | .77 | .79 | .72 | .59 | .78 | .64 | .81 | .75 | .82 |

| 34. | Upset | .81 | .84 | .76 | .78 | .80 | .88 | .81 | .86 | .86 |

| 35. | Difficult to relax | .80 | .81 | .77 | .90 | .73 | .88 | .86 | .89 | .85 |

| 36. | Depressed | .87 | .88 | .83 | .77 | .87 | .82 | .85 | .89 | .89 |

| 37. | Concentration affected | .86 | .85 | .84 | .91 | .84 | .79 | .87 | .87 | .88 |

| 38. | Been embarrassed | .84 | .85 | .81 | .83 | .84 | .86 | .81 | .82 | .86 |

| 39. | Avoid going out | .84 | .85 | .82 | .76 | .84 | .75 | .87 | .85 | .92 |

| 40. | Less tolerant of others | .81 | .81 | .79 | .81 | .81 | .74 | .86 | .82 | .80 |

| 41. | Trouble getting on with others | .77 | .77 | .76 | .79 | .74 | .78 | .85 | .89 | .79 |

| 42. | Irritable with others | .78 | .79 | .77 | .86 | .80 | .75 | .83 | .86 | .74 |

| 43. | Difficulty doing jobs | .84 | .86 | .82 | .88 | .84 | .74 | .86 | .88 | .88 |

| 44. | Health worsened | .79 | .81 | .75 | .73 | .76 | .77 | .84 | .83 | .89 |

| 45. | Financial loss | .67 | .72 | .56 | .49 | .64 | .60 | .82 | .59 | .79 |

| 46. | Unable to enjoy people's company | .86 | .87 | .83 | .80 | .87 | .86 | .87 | .90 | .85 |

| 47. | Life unsatisfying | .81 | .83 | .76 | .88 | .78 | .86 | .86 | .90 | .86 |

| 48. | Unable to function | .81 | .83 | .77 | .84 | .76 | .76 | .88 | .89 | .84 |

| 49. | Unable to work | .82 | .83 | .79 | .79 | .85 | .77 | .86 | .84 | .80 |

Loadings ≤.45 are in bold and italicized

Results of the one-factor EFA did not change substantially when performed separately for patients and general population subjects or for each of the six countries. However, we found greater variation in the loadings across countries. In Croatia, the country with the smallest number of subjects, five loadings did not reach the threshold of salient loadings and among them three were small.

Overall, the overwhelming majority of salient loadings led us to accept that a general factor underlies OHIP responses.

Extraction of multiple factors

Cattell's scree plot presented a steep drop from factor one to factor two, supporting a strong general factor. However, Horn's parallel analysis suggested a four-factor solution (Figure 1). Based on the results of the parallel analysis, we retained the four-factor solution. After rotation by oblimin, the first factor contained 18 items that seemed to represent Psychosocial Impact and the factor was named accordingly (Table 2). A second factor contained 10 items that reflected concerns about Oral Function. The third factor contained only six items, and problems with aesthetics characterized four of the items. The remaining two items (worried, self-conscious) describe a lower degree of psychological impact, but conceivably also correspond to concerns over appearance. We named this factor Orofacial Appearance. Finally, a fourth factor contained seven items related to pain in the orofacial system, leading to the name Orofacial Pain. The four factors correlated between 0.45 and 0.70 with each other and their Cronbach alpha values ranged from 0.85 to 0.95 (Table 3). Five of the OHIP-46 items did not have salient loadings on any of the four factors.

Table 2. One- and four-factor solutions for 46 OHIP items not referring to dentures specifically (factors in >1-factor solutions are extracted with iterated principal factor method and oblimin-rotated).

| OHIP item | One factor | Four factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial Impact | Oral Function | Orofacial Appearance | Orofacial Pain | |||

| 1. | Difficulty chewing | .76 | -.03 | .57 | .18 | .27 |

| 2. | Trouble pronouncing words | .76 | .05 | .77 | .11 | .00 |

| 6. | Taste worse | .74 | .22 | .57 | -.06 | .15 |

| 16. | Uncomfortable to eat | .80 | .07 | .48 | .19 | .27 |

| 24. | Speech unclear | .80 | .10 | .70 | .17 | .00 |

| 25. | Others misunderstood | .77 | .25 | .57 | .07 | .01 |

| 26. | Less flavor in food | .78 | .37 | .55 | -.09 | .06 |

| 28. | Avoid eating | .78 | .04 | .59 | .18 | .17 |

| 29. | Diet unsatisfactory | .84 | .26 | .47 | .10 | .19 |

| 32. | Interrupt meals | .82 | .29 | .47 | .08 | .14 |

|

| ||||||

| 3. | Noticed tooth which doesn't look right | .59 | -.11 | .02 | .62 | .30 |

| 4. | Appearance affected | .71 | .06 | .28 | .61 | -.05 |

| 19. | Worried | .74 | .10 | .01 | .58 | .29 |

| 20. | Self-conscious | .78 | .15 | .16 | .58 | .11 |

| 22. | Uncomfortable about appearance | .82 | .18 | .14 | .68 | .05 |

| 31. | Avoid smiling | .80 | .27 | .24 | .52 | -.05 |

|

| ||||||

| 10. | Painful aching | .71 | .08 | .15 | .02 | .71 |

| 11. | Sore jaw | .66 | .15 | .11 | -.06 | .68 |

| 13. | Sensitive teeth | .49 | .10 | -.19 | .20 | .58 |

| 14. | Toothache | .62 | .10 | -.14 | .24 | .67 |

| 15. | Painful gums | .65 | -.05 | .25 | .01 | .68 |

| 17. | Sore spots | .65 | .01 | .18 | .02 | .69 |

| 12. | Headaches | .61 | .47 | -.14 | -.04 | .46 |

|

| ||||||

| 23. | Tense | .83 | .57 | .00 | .25 | .15 |

| 33. | Sleep interrupted | .77 | .69 | -.02 | -.02 | .22 |

| 34. | Upset | .81 | .55 | -.01 | .28 | .15 |

| 35. | Difficult to relax | .80 | .79 | -.01 | .09 | .01 |

| 36. | Depressed | .87 | .76 | .01 | .19 | .01 |

| 37. | Concentration affected | .86 | .83 | .00 | .01 | .10 |

| 38. | Been embarrassed | .84 | .47 | .13 | .43 | -.04 |

| 39. | Avoid going out | .84 | .70 | .15 | .16 | -.09 |

| 40. | Less tolerant of others | .81 | .89 | -.04 | .00 | .01 |

| 41. | Trouble getting on with others | .77 | .83 | .06 | .02 | -.09 |

| 42. | Irritable with others | .78 | .95 | -.11 | -.02 | .01 |

| 43. | Difficulty doing jobs | .84 | .86 | .07 | -.06 | .04 |

| 44. | Health worsened | .79 | .70 | .13 | -.04 | .09 |

| 45. | Financial loss | .67 | .56 | .13 | .03 | .02 |

| 46. | Unable to enjoy people's company | .86 | .70 | .14 | .19 | -.08 |

| 47. | Life unsatisfying | .81 | .76 | .09 | .07 | -.04 |

| 48. | Unable to function | .81 | .80 | .14 | -.06 | -.01 |

| 49. | Unable to work | .82 | .87 | .06 | -.10 | .06 |

|

| ||||||

| 5. | Breath stale | .59 | .15 | .16 | .16 | .27 |

| 7. | Food catching | .55 | -.08 | .27 | .21 | .35 |

| 8. | Digestion worse | .75 | .40 | .37 | -.05 | .15 |

| 21. | Miserable | .84 | .29 | .13 | .42 | .21 |

| 27. | Unable to brush teeth | .75 | .17 | .31 | .21 | .25 |

loadings >.45 are shaded

Table 3. Factor intercorrelations and Cronbach alphas in the four-factor solution.

| Psychosocial Impact (alpha: .95) | Oral Function (alpha: .92) | Orofacial Appearance (alpha: .88) | Orofacial Pain (alpha: .85) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial Impact | 1 | |||

| Oral Function | .70 | 1 | ||

| Orofacial Appearance | .58 | .55 | 1 | |

| Orofacial Pain | .54 | .45 | .49 | 1 |

Secondary analyses

The principal components method did not substantially change the pattern of loadings of the four-factor EFA. When promax was used for rotation, the overall factor pattern remained stable and interpretation of findings did not change. Overall, OHIP factorial structure seemed to be robust against methodological influence.

Discussion

This secondary analysis of international data of prosthodontic patients and general population subjects from six countries found that the Oral Health Impact Profile could be characterized by either four correlated dimensions or a strong general factor. The four correlated latent factors Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact appeared as dimensions that can be interpreted in light of substantive knowledge.

The original publication of the OHIP categorized items into seven domains named Functional Limitations, Physical Pain, Psychological Discomfort, Physical Disability, Psychological Disability, Social Disability, and Handicap (1). These domains were derived based on a conceptual model of oral health (26) and items were assigned to domains based on expert opinion. When experts were asked in a later study to assign items to domains/dimensions, items could be reproducibly assigned to dimensions but a smaller number of dimensions was sufficient to group all items (27). This finding supported the multidimensional model of OHRQoL, but also provided evidence that a model with fewer than seven dimensions may be sufficient to account for the OHIP's latent structure.

In general, (perceived) oral health is thought to be multidimensional (28), and previous factor analytic studies, with one exception (11) agreed that OHIP has several latent factors. Most previous studies presented between three (10) and six factors (4), with four dimensions often identified – the number we found. Studies using the OHIP-49 found four factors in German general population subjects (2) and older adults in Australia (3). While the factors were not named in the Australian study, our findings in Germany were very similar to the present international study, except that Orofacial Appearance was a weaker factor. Although factor analytic studies using abbreviated OHIP versions vary in the number and interpretation of OHRQoL factors, they share many similarities with our findings for the long OHIP:

We identified an Oral Function dimension. This factor encompasses many of the same items as OHIP's original Functional Limitation (1) domain. This factor was also found in Chinese partially edentulous patients seeking dental implant therapy (10), Chinese community subjects (8), and in Japanese workers (7). Another study of Brazilian edentulous patients called a factor covering similar content Masticatory Discomfort and Disability (6).

We identified an Orofacial Pain dimension. We named this dimension Orofacial Pain because it contained several different aspects of pain in the orofacial system. The original OHIP categorized many of our Orofacial Pain items as Physical Pain (1), a factor also found in Japanese workers (7). In Brazilian edentulous subjects, the content of this factor was also identified but grouped with psychological concerns and named Oral Pain and Discomfort (6). In Chinese partially edentulous patients seeking dental implant therapy and in Chinese community subjects it was called (Physical) Pain and Discomfort (8, 10).

We identified an Orofacial Appearance dimension. None of the previous EFA studies identified this factor as a separate dimension. In Japanese workers, a factor named Psychological Discomfort was identified for which five out of six items matched our Orofacial Appearance factor (7). Although three appearance items had the strongest loadings for this factor, the authors decided to call this factor Psychological Discomfort. This difference in interpretation might indicate that previous studies stayed within the domain framework provided in the original OHIP, which does not contain appearance as a separate concept. Some investigators did not consider OHIP as well suited to measure esthetical concerns (29), leading investigators already familiar with the OHIP to develop a stand-alone instrument to measure orofacial appearance (30). However, other investigators have recognized an aesthetic component in OHIP items as evidenced by the development of an abbreviated “OHIP-aesthetic” (31).

We identified a Psychosocial Impact dimension. All previous EFA studies identified psychological and social latent factors. The original OHIP separated this impact into five dimensions (Psychological Discomfort; Physical, Psychological, Social Disability; Handicap). Some previous studies differentiated Psychological Symptoms from Psychosocial Symptoms (9), Psychological Discomfort and Disability from Social Disability (6), Disability from Handicap (8), and Psychological Discomfort from Disability & Handicap (7). Others found Psychological and Social Impact (10) to be a single dimension, as we concluded.

OHIP has also been used together with other OHRQoL questionnaires. Using both the OHIP-14 (3) and Oral Impact of Daily Performances (32), Functional Limitations, Pain-Discomfort, and Psychosocial Impacts were identified (33). When the OHIP-14 was used with the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (34), six factors were found but not named (35). Another study used OHIP-14 with the European Quality of Life indicator or EuroQol (EQ-5D+) and found four factors which were not named (36).

Finally, although dimensions were found in the previously mentioned studies and domain scores have been used in many OHIP applications, researchers often interpreted total OHIP scores. To provide a framework for interpreting total scores, rules have been developed such as the population normative values (37) and the Minimal Important Difference to identify clinically relevant change (38). The use of total scores indicated that researchers considered OHRQoL summarized by one score as meaningful. Such an interpretation is consistent with our result that the OHIP has a strong higher-order factor.

Strengths and limitations

In our approach, we assumed that the structure of the OHIP was sufficiently similar across countries and populations to allow data to be combined for analyses. However, differences are likely present. For example, in Croatia we detected three factor loadings on the general factor substantially smaller than 0.45 – findings that are noteworthy compared to the consistently high loadings in the other countries. Even though Croatia contributed the smallest number of subjects and sampling variability affected our results, further analyses are necessary to assess measurement invariance across populations. In general, assessing differences in item characteristics across populations (cultures) is an important step in the psychometric evaluation of self-report instruments. Despite the presence of variation across cultures and populations, our findings present an overall consistent and clinically meaningful pattern.

Five items (10%) did not meet our saliency criterion for any of our four factors. Some of these items had lower loadings for all dimensions, and they may represent more general consequences (food catching, unable to brush teeth) or symptoms (breath stale) of oral conditions. Two of the five items (digestion worse and miserable) had loadings of 0.40 and 0.42, respectively, almost meeting our saliency criterion. How these five items relate to the four dimensions is not clear at this moment. Only the set of 46 items not specifically denture-related was considered because these items could be answered by all subjects. Responses concerning dentures and natural teeth were often not straightforward. For example, subjects with dentures might have responded to questions about natural teeth by referencing their tooth replacements. Alternatively, subjects without dentures may have answered questions about dentures by referring to experiences with their fixed prosthodontics. Finally, exploratory factor analysis provided many options when performing the analysis. The factor extraction method, the method to determine the number of factors that should be retained for further analysis, and the factor rotation method are major methodological parameters. By varying all these methods, we presented some evidence that our findings are robust against arbitrary methodological influences.

Conclusion

In this exploratory study, we provided (i) substantial evidence for a strong general factor underlying OHIP items, (ii) evidence for a more differentiated four-dimensional structure of OHRQoL, and (iii) evidence that the structure of the OHIP is similar across cultures and populations. The four identified factors were named Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact. The existence of a dimension characterizing the various physical functions of the orofacial system seems highly plausible because every organ system has some function. Many individuals suffer from dental, oral, and orofacial pains. The prevalence of these conditions and their substantial impact on the individual support the existence of a separate pain factor for the orofacial system. It is also plausible that the appearance of the orofacial area – dental and craniofacial aesthetics - is a relevant part of perceived oral health and therefore essential for a complete understanding of OHRQoL. Finally, dental and oral conditions cause a substantial amount of distress, which we believe is captured in our dimension Psychosocial Impact.

In the subsequent article in this issue (39), the findings that OHIP scores have four dimensions with a general strong factor will be tested using confirmatory factor analysis.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DE022331.

Footnotes

None of the authors reported any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Health. 1994;11:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.John MT, Hujoel P, Miglioretti DL, Leresche L, Koepsell TD, Micheelis W. Dimensions of oral-health-related quality of life. J Dent Res. 2004;83:956–960. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slade GD. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:284–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segu M, Collesano V, Lobbia S, Rezzani C. Cross-cultural validation of a short form of the Oral Health Impact Profile for temporomandibular disorders. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:125–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen F, Locker D. A modified short version of the oral health impact profile for assessing health-related quality of life in edentulous adults. Int J Prosthodont. 2002;15:446–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souza RF, Leles CR, Guyatt GH, Pontes CB, Della Vecchia MP, Neves FD. Exploratory factor analysis of the Brazilian OHIP for edentulous subjects. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37:202–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.02043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ide R, Mizoue T, Yamamoto R, Tsuneoka M. Development of a shortened Japanese version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) for young and middle-aged adults. Community Dent Health. 2008;25:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xin WN, Ling JQ. Validation of a Chinese version of the oral health impact profile-14. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2006;41:242–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mumcu G, Hayran O, Ozalp DO, Inanc N, Yavuz S, Ergun T, et al. The assessment of oral health-related quality of life by factor analysis in patients with Behcet's disease and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:147–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu JY, Pow EH, Chen ZF, Zheng J, Zhang XC, Chen J. The Mandarin Chinese shortened version of Oral Health Impact Profile for partially edentate patients with implant-supported prostheses. J Oral Rehabil. 2012;39:591–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2012.02292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.dos Santos CM, de Oliveira BH, Nadanovsky P, Hilgert JB, Celeste RK, Hugo FN. The Oral Health Impact Profile-14: a unidimensional scale? Cad Saude Publica. 2013;29:749–757. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2013000800012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.John MT, Reißmann DR, Feuerstahler L, Waller N, Baba K, Larsson P, et al. Dimensions of Oral Health–Related Quality of Life Project - Overview and studied population. J Prosthodont Res. 2014;1:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpor.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szentpetery A, Szabo G, Marada G, Szanto I, John MT. The Hungarian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petricevic N, Celebic A, Papic M, Rener-Sitar K. The Croatian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile Questionnaire. Coll Antropol. 2009;33:841–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.John MT, Patrick DL, Slade GD. The German version of the Oral Health Impact Profile--translation and psychometric properties. Eur J Oral Sci. 2002;110:425–433. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2002.21363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rener-Sitar K, Celebic A, Petricevic N, Papic M, Sapundzhiev D, Kansky A, et al. The Slovenian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile Questionnaire (OHIP-SVN): translation and psychometric properties. Coll Antropol. 2009;33:1177–1183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsson P, List T, Lundstrom I, Marcusson A, Ohrbach R. Reliability and validity of a Swedish version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-S) Acta Odontol Scand. 2004;62:147–152. doi: 10.1080/00016350410001496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamazaki M, Inukai M, Baba K, John MT. Japanese version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-J) J Oral Rehabil. 2007;34:159–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2006.01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.John MT, LeResche L, Koepsell TD, Hujoel PP, Miglioretti DL, Micheelis W. Oral health-related quality of life in Germany. Eur J Oral Sci. 2003;111:483–491. doi: 10.1111/j.0909-8836.2003.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hattie J. Methodology review: Assessing unidimensionality of tests and items. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1985;9:139–164. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cattell RB. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1966;1:245–276. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horn JL. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1965;30:179–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02289447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007;45:S22–31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jennrich RI, Sampson PF. Rotation for simple loadings. Psychometrika. 1966;31:313–323. doi: 10.1007/BF02289465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendrickson AE, White PO. A method for the rotation of higher-order factors. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1966;19:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1966.tb00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Locker D. Measuring oral health: A conceptual framework. Community Dent Health. 1988;5:3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.John MT. Exploring dimensions of oral health-related quality of life using experts' opinions. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:697–704. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert GH, Duncan RP, Heft MW, Dolan TA, Vogel WB. Multidimensionality of oral health in dentate adults. Med Care. 1998;36:988–1001. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehl C, Kern M, Freitag-Wolf S, Wolfart M, Brunzel S, Wolfart S. Does the Oral Health Impact Profile questionnaire measure dental appearance? Int J Prosthodont. 2009;22:87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsson P, John MT, Nilner K, Bondemark L, List T. Development of an Orofacial Esthetic Scale in prosthodontic patients. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:249–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong AH, Cheung CS, McGrath C. Developing a short form of Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) for dental aesthetics: OHIP-aesthetic. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:64–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adulyanon S, Sheiham A. A new socio-dental indicator of oral impacts on daily performances. J Dent Res. 1996;75:231. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montero J, Bravo M, Vicente MP, Galindo MP, Lopez JF, Albaladejo A. Dimensional structure of the oral health-related quality of life in healthy Spanish workers. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atchison KA, Dolan TA. Development of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index. J Dent Educ. 1990;54:680–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hassel AJ, Steuker B, Rolko C, Keller L, Rammelsberg P, Nitschke I. Oral health-related quality of life of elderly Germans--comparison of GOHAI and OHIP-14. Community Dent Health. 2010;27:242–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brennan DS, Spencer AJ. Dimensions of oral health related quality of life measured by EQ-5D+ and OHIP-14. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:35. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szabo G, John MT, Szanto I, Marada G, Kende D, Szentpetery A. Impaired oral health-related quality of life in Hungary. Acta Odontol Scand. 2011;69:108–117. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2010.538717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.John MT, Reissmann DR, Szentpétery A, Steele JG. An approach to define clinical significance in prosthodontic patients. J Prosthodont. 2009;18:455–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2009.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.John MT, Feuerstahler L, Waller N, Baba K, Larsson P, Celebic A, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Oral Health Impact Profile. J Oral Rehabil. doi: 10.1111/joor.12191. submittted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]