Abstract

Sexually-dimorphic behavioral and biological aspects of human eating have been described. Using psychophysiological interactions (PPI) analysis, we investigated sex-based differences in functional connectivity with a key emotion-processing region (amygdala, AMG) and a key reward-processing area (ventral striatum, VS) in response to high vs. low energy-dense (ED) food images using blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in obese persons in fasted and fed states. When fed, in response to high vs. low-ED food cues, obese men (vs. women) had greater functional connectivity with AMG in right subgenual anterior cingulate, whereas obese women had greater functional connectivity with AMG in left angular gyrus and right primary motor areas. In addition, when fed, AMG functional connectivity with pre/post-central gyrus was more associated with BMI in women (vs. men). When fasted, obese men (vs. women) had greater functional connectivity with AMG in bilateral supplementary frontal and primary motor areas, left precuneus, and right cuneus, whereas obese women had greater functional connectivity with AMG in left inferior frontal gyrus, right thalamus, and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. When fed, greater functional connectivity with VS was observed in men in bilateral supplementary and primary motor areas, left postcentral gyrus, and left precuneus. These sex-based differences in functional connectivity in response to visual food cues may help partly explain differential eating behavior, pathology prevalence, and outcomes in men and women.

Keywords: Gender, Obese, fMRI, PPI, Neural Connectivity, Food Cues

1. Introduction

Sex-dependent differences have been reported in human eating behavior (Bates et al., 1999) such as; dietary disinhibition (Seim and Fiola, 1990), emotional eating (Van Strien, et al., 1986a), and binge eating (Folope et al., 2012). Moreover, higher prevalence of eating disorders (Brooks et al., 2011; Jacobi et al., 2004; Kjelsas et al., 2004; Woodside et. al., 2001) and obesity (Flegal et al., 1998; Wang and Beydoun, 2007; WHO, 2010) are observed in women compared with men. Although recent reports show that there is no difference in the overall incidence of obesity between men and women in the U.S. (Ogden et al., 2012; Flegal et. al., 2012), gender differences are apparent in the prevalence of severe obesity. More women are severely obese, with the prevalence of Class II obesity (Body mass index (BMI) ≥ 35 kg/m2)18.1% in women compared with 12.5% in men ,and Class III obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) 8.1% of women and 4.4% of men obese (Flegal et al., 2012). Furthermore, these gender differences are also predicted to continue to 2030 (Finkelstein et al 2012). Physiologically, females and males differ in levels of adiposity (Rosenbaum and Leibel, 1999; Woods et al., 2003), lipolytic capacity per cell (Löfgren et al., 2002), and body fat (Lemieux et al., 1993). Thus, although men and women are both prone to obesity, its manifestations and physiological consequences differ between men and women, resulting in different eating and behavioral profiles. These differences indicate that there are sex-dependent disparities in the biological underpinnings of energy intake and balance, which may explain differential prevalence of eating disorders and severity levels of obesity in men and women.

Eating behavior is governed by a complex interplay of peripheral and neural signals in mammals (Berthoud and Morrison, 2008). Sensory afferent inputs (e.g. tactile, visual) are integrated with metabolic signals in cortical and sub-cortical areas and regulate energy balance. Downstream effector motor responses are generated to trigger food foraging (Atalayer and Rowland, 2011) and eating behavior (Lenard and Berthoud, 2008). Dysregulation in any of these neural or peripheral systems in the body may result in alterations in eating behavior and metabolism, leading to changes in body weight and/or composition. Moreover, sexual dimorphism in these systems also may lead to differential eating behavior and energy balance outcomes (Goodpaster et al., 2005; Power and Schulkin, 2008). Neuroimaging studies have shown sex-dependent structural (Mueller et al., 2011) and functional (Del Parigi et al., 2005; Smeets et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2009; Cornier et al., 2010; Killgore et al., 2013) differences in the brain related to eating behavior and energy balance. Moreover, differences in neural responses to cue-activated response inhibition tasks (Hester et al., 2004a; Garavan et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006) between men and women have also been reported. Normal weight women compared with normal weight men showed greater responses to taste and olfactory stimulation in the insula (Uher et al., 2006), and greater responses to high vs. low energy food pictures (when fasted [≥ 3hours]), in fusiform gyrus (Frank et al., 2010). We recently reported that when fasted, obese women showed higher activation in response to high vs. low-ED visual food cues in the caudate (Geliebter et al., 2013), which is a brain area implicated in reward processing and craving (Pelchat et al., 2004). Other studies have reported a greater activation in response to food pictures with high hedonic value in fasting normal weight women (compared with men) in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Cornier et al., 2010), a region implicated in inhibitory control (Diamond, 1990). On the other hand, in another study, participants were instructed to perform cognitive inhibition (i.e., ignore, shift thoughts) during the exposure to visual and olfactory food cues and taste stimulation. Men showed greater activation in the striatum and greater deactivation in insula, amygdala, hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex comapred with women (Wang et al., 2009). Haase et al. (2011) also showed that, in response to tastants (i.e., salty, sour, bitter, sweet) in both fed to fasted conditions; women showed less deactivation in the insula, cerebellum, and middle frontal gyrus compared with men. The middle frontal gyrus has been implicated in decision-making (Rolls and Grabenhorst, 2008), dual-task performance (Collette, et al., 2005) and resolution of reward conflict (Rogers et al., 1999). Moreover, it has been shown that fMRI signals in response to high-calorie food items are BMI-dependent (Rothemund et al., 2007) and baseline fMRI signals before a diet correlate with the subsequent weight loss (Weygandt et al. 2013). Collectively, these studies suggest functional neural differences related to cue responsivity between men and women, which may contribute to the explanation for previously reported sex-based dimorphisms in eating behavior.

The main objective of this study was to investigate gender differences in functional connectivity during processing of high vs. low energy dense (ED) visual food cues in obese individuals. In order to test the link of hypothesized connectivity differences and body weight, secondarily we examined whether there was any interaction between BMI and gender in functional neural connectivity during the processing of high vs. low ED visual food cues. Psychophysiological interactions analysis (PPI) (Friston et al., 1997) was used to determine regions displaying simultaneous activation with selected seed regions. The outputs from these analyses provide support for neural interactivity, or “crosstalk,” between the seed and the identified regions. Moreover, it has been shown that one of the foremost contributing factors to overeating and obesity is eating without the presence of hunger and this can be triggered by emotions and the hedonic reward value of food (Rolls, 2007; Cota et al., 2006; Berridge, 2004; Morris and Dolan, 2001; Stellar, 1994). Previous research suggests that the amygdala and the ventral striatum play key roles in feeding and food reward (Everitt et al., 1989; O'Doherty et al., 2006; Passamonti et al., 2009; Fletcher et al., 2010). Thus, we chose the amygdala (AMG) –a key area implicated in emotion processing, and the ventral striatum (VS) –a key area implicated in reward processing, as ‘seed’ regions in our analysis. Sex-based differences were explored with group level analyses. We hypothesized that there would be gender differences in the functional connectivity between the seed regions and areas involved cognitive and/or emotion processing and motor planning. More specifically, in response to high vs. low-ED food cues, in both fasted and fed states, in obese women compared to men, AMG and VS would have greater functional connectivity with regions associated with cognitive control. Such findings would have implications for more effective prevention and intervention strategies for obesity and overeating that are specifically targeted for each gender.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Thirty-one otherwise healthy obese adults (male = 17, female = 14) with body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 (mean ± SD; male = 36.2 ± 5.5 kg/m2, and female = 36.9 ± 5.6) and ages between 25 and 45 (mean ± SD; male = 35 ± 9.0, and female = 35 ± 6.9) were recruited at a large university-affiliated hospital in New York City. Volunteers were eligible to participate if their weight was stable for at least 3 months (< ± 5% body weight change). All participants were right-handed (self-report) and non-smokers and not currently taking any medication or undergoing vigorous exercise for more than 5 hours per week. There was an initial consultation to assess candidates’ eligibility for inclusion in the study. A physical exam was conducted by a physician to determine presence of any chronic diseases (e.g. diabetes). A fasting blood sample was collected for hematological and clinical chemistry tests to assess current health status (e.g., drug use etc). Candidates with a medical history (self-report) of neurologic disorders (e.g. stroke) were not included. A clinical screening of all the MRI scans was conducted by a radiologist. If the scan revealed significant structural abnormalities, the scan would have been excluded from the subsequent analysis; however, this did not occur. Candidates were also assessed for psychiatric disorders (e.g. depression) by a clinical interview during the initial consultation. Females will also undergo a urine pregnancy test. All female participants were premenopausal, and not currently pregnant or lactating. The protocol was reviewed and approved by Columbia University Medical Center and St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Institutional Review Boards, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment into the study.

2.2. Experimental Paradigm

fMRI was used to measure blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal change in response to food-related visual cues of high and low-ED foods in both fasted and fed states. Participants attended an initial consultation to be assessed for study eligibility. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.05 kg, using a calibrated scale (Weight Tronix, New York, NY). Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm, using a stadiometer (SECA 217). Urine samples were collected at the physical exam to screen for pregnancy and drug use. The Eating Disorder Examination (Fairnurn and Cooper, 1993) was administered to determine binge eating status (DSM-IV TR) (APA, 2000), which was used as a covariate in the imaging analysis to control for potential effects of binge eating on neural activation (Schienle et al., 2009). Participants rated their preferred flavor: chocolate, vanilla, or strawberry for Boost (Mead Johnson), a nutritionally complete shake.

The key experimental procedures were scheduled on two non-consecutive days. Participants were instructed to consume a standard pre-fast meal of approximately 4180 kJ (1000 kcal) around 7–8 pm, followed by an overnight fast (apart from water) until they arrived at the laboratory at approximately 9 am the following morning. Participants were given information about standard dinners containing 4180 kJ. On arrival, participants were either provided with a 750 mL liquid meal (Boost, Mead Johnson) (3140 kJ, 24, 55 and 21% energy from protein, carbohydrate and fat respectively) (fed condition) or 750 mL water (fasted condition) in a randomized counterbalanced order 95 min prior to scans. They rated their hunger (0: not hungry at all; 100: very hungry) and fullness (0: not full at all; 100: very full) using Likert-type scales 10 min prior to scans. Participants were then positioned in the MRI scanner with a head restraint to minimize movement during the scan. A headset and goggles were worn, permitting communication with the participant and presentation of the stimuli.

During the scan, visual and auditory stimuli representing high-ED foods (e.g. chocolate cake, French fries, burger etc.), low-ED foods (e.g. green beans, apple, pear etc.), and non-foods (e.g. stapler, pens etc.) were presented. The high-ED foods contained at least 3.5 kcal/g and the low-ED foods less than 1 kcal/g. Visual cues were photos of foods transmitted through goggles and auditory cues were recorded 2-word names similar in content to the visual stimuli, transmitted through a headset. Stimuli of each condition type did not repeat, and were presented in two separate runs, resulting in a total of twelve runs (2 visual high-ED, 2 visual low-ED, 2 visual non-food, 2 auditory high-ED, 2 auditory low-ED and 2 auditory non-foods), each lasting 2 minutes, 12 seconds. Within each run, 10 different stimuli of the same type were presented consecutively, resulting in a total block duration of 40 s (4s for each picture presentation [visual cue], or 2-word name repeated twice, e.g. “chocolate brownie, chocolate brownie” [auditory cue]), with a 52-second pre-stimulus baseline (white crosshair centered in a black background) and a 40-second post-stimulus baseline. The six runs containing visual cues were followed by the six runs containing auditory cues, and stimulus types were presented in pseudorandom order within each set of six runs, with the constraint that a run of any stimulus type could not be followed by a run of the same stimulus type (e.g., for the set of visual runs: 1) high-ED, 2) low-ED, 3) non-food, 4) low-ED, 5) non-food, 6) high-ED). This randomization was conducted separately for each participant according to a Latin square design. An eye-tracking device was used to monitor participants’ wakefulness during the entire procedure. They were instructed to pay attention to each presented stimulus block. Following each run, to ensure alertness, participants were asked to verbally rate hunger on a Likert-type scale from 1 to 10, with 1 being “not hungry at all” and 10 being “very hungry;” and desire to eat on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 being “not at all” and 10 being “very much.” Total time in the scanner was approximately 60 min.

2.3. fMRI Acquisition and Image Analyses

A 1.5-Tesla twin-speed 65 cm bore diameter GE MRI scanner with quadrature RF head coil (MRI Devices Corporation, Gainesville, FL) was used to improve the signal to noise ratio. During each experimental run, 36 axial scans of the whole brain were acquired, each scan consisting of 25 contiguous slices (4 mm thick), with a 19 × 19 cm field of view, an acquisition matrix size of 128 × 128 voxels, and 1.5 mm × 1.5 mm in plane resolution. The first three scans of each run (12 sec) were discarded to attain magnetic equilibration. The axial slices were parallel to the AC/PC line. T2*-weighted images with a gradient echo pulse sequence (echo time = 60 ms, repetition time = 4 sec, flip angle = 60°) were acquired with matched anatomic high resolution T1 weighted scans.

Preprocessing for fMRI images and 1st and 2nd level analyses was conducted using SPM8 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London, UK). Prior to statistical analyses, the realigned T2* weighted volumes were slice-time corrected, spatially transformed to a standardized brain (Montreal Neurologic Institute), and smoothed with a 8-mm full-width half-maximum Gaussian kernel. Each of the 12 runs within each session were concatenated together to create a single run per session (396 total time points). For the 1st-level analysis, block regressors were included to account for the mean of each run within each session. motion (obtained from the realignment procedure), as well as global signal and spikes computed using the scn_session_spike_id.m script available in Diagnostics Tools for MATLAB (http://wagerlab.colorado.edu/tools) were added as additional covariates to account for transitory artifacts (i.e. k-space spikes) due to scanner hardware malfunction (i.e. electrical discharge, loose hardware or “dropped” images). Both scan sessions (fed and fasted conditions) were included in the 1st level model for each participant. 1st-level regressors were created by convolving the onset of each trial (visual high-ED, low-ED and NF) with the canonical HRF with duration of 40 seconds for both fed and fasted sessions.

Functional neural connectivity analyses were conducted using PPI to examine the effect of gender in response to high vs. low-ED visual food cues in fed and fasted conditions. Given our specific hypotheses, we examined functional connectivity of a priori selected seed regions (amygdala and ventral striatum). Analyses of auditory cues and non-food stimuli will not be presented. Main sex-based differences in BOLD activations in response to high-ED > low-ED food cues during fed and fasted states are reported elsewhere (Geliebter et al., 2013).

Masks for these regions were defined using the WFU Pickatlas (ventral striatum was defined using caudate at z < 0). The deconvolved time course (1st eigenvariate) from each mask was extracted, and activity throughout the whole-brain was then regressed on a voxel-wise basis against the product of this time course and the vector of the psychological variable of interest (1*high-ED + -1*low-ED stimuli) with the physiological and the psychological variables added as regressors of no interest. These produced the following beta maps for each seed region: 1) high-ED > low-ED fed and 2) high-ED > low-ED fasted. The beta maps for each seed region (AMG or VS), and condition (fed or fasted) were submitted to group random effects models using multiple regression with the following factors: age and binge-eating status (DSMIV-TR) (APA, 2000). An additional 2nd-level model analysis was conducted in order to identify any regions whose functional connectivity (with above seed regions) covaried with BMI in a sex-dependent manner. In this analysis, BMI was included as two separate, continuous regressors of interest: one regressor corresponded to males, and the other corresponded to females (see SPM design matrix, Supplementary Figure 3). Interaction effects were identified using a contrast of beta estimates for these regressors (i.e. BMI [males] > BMI [females]), which were then converted to t-values. For display purposes, statistical maps for the main effects of gender, (e.g. Fed: Females [F] > Males [M]) are displayed at a threshold of p < 0.005 uncorrected, and a cluster-size threshold of 50 contiguous voxels. In addition, contiguous clusters of size 147 or more were deemed significant at p < 0.05 corrected (denoted by asterisk in the tables). This number was determined by 2000 Monte Carlo simulations of whole-brain fMRI data with respective data parameters of the present study according to the approach in AFNI 3dClustSim (Cox, 1996).

2.4. Analysis of Subjective Appetite Ratings

Subjective appetite ratings were analyzed in SPSS (version 20). A between within repeated measures ANOVA was conducted using sex as between subjects factor and condition (fed or fasted) as within subjects factor. If significant main effects were observed the location of the difference was determined using t-test. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Hunger and Fullness Ratings

One-way ANOVA models (sex as factor) were used to compare men and women in their pre-scan hunger and fullness ratings during both fed and fasted conditions. Prior to the scan, fullness ratings in the fed condition and hunger ratings in the fasted condition did not differ between men and women. Moreover, all participants scored higher for fullness (mean = 56.4 vs. 29.8; p < 0.0001) in the fed versus the fasted condition, and this did not differ between men and women. In addition, all participants scored higher on hunger (mean = 57.8 vs. 29.8; p < 0.0001) in the fasted versus fed condition, and this did not differ between men and women.

3.2. Amygdala (AMG) as the “Seed” Region

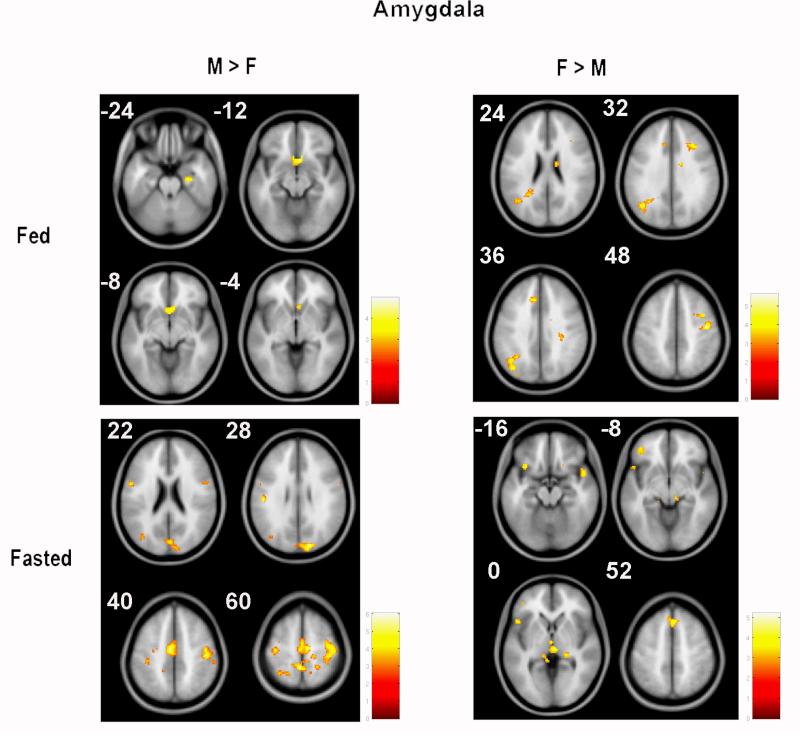

Using the AMG as seed region in the fed state there was greater functional connectivity in obese males compared with females (M > F) in the right subgenual anterior cingulate (sgACC). Furthermore, obese females compared with males (F > M) showed greater functional connectivity in the left angular gyrus and the right precentral gyrus (Figure 1, Table 1). Greater functional connectivity with AMG (high vs. low-ED food cues) in the fasted state for obese males compared to obese females (M > F) was observed in the right supplementary frontal motor area (SMA), bilateral precentral gyri, right cuneus, and left precuneus. Obese females compared to obese males (F > M) showed greater functional connectivity with AMG in left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), right thalamus, and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC) (Figure 1, Table 2).

Figure 1.

Sex-based differences in functional connectivity with amygdala (AMG) in response to visual high vs. low-ED food cues. Top left) When fed, obese males (vs. females) had greater functional connectivity with AMG in sub-genual anterior cingulate (z=-12, -8). Top right whereas females had greater connectivity with AMG in angular (z=36) and precentral gyrus (z=48). Lower left) When fasted obese males had greater functional connectivity with AMG in precuneus (z=22, 28), supplementary motor area and precentral gyrus (z=40, 60). Lower Right) whereas females had greater functional connectivity with AMG in thalamus and inferior frontal gyrus (z=0) and dorsomedial prefrontal gyrus (z=52) (M=males, F=females). Only supra-threshold clusters are mentioned in this caption; for sub-threshold cluster labels see Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Functional connectivity with amygdala in response to high vs. low-ED food cues in the fed state.

| Amygdala - Fed | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Hemisphere | k | MNI Coordinates | t-value | |||

| x | y | z | |||||

| M > F | Limbic/Parahippocampal | Right | 51 | 26 | −16 | 26 | 4.0709 |

| Subgenual Anterior | Right | 153 | 6 | 16 | −12 | 4.4816 | |

| Cingulate* Precuneus | Right | 72 | 26 | −52 | 70 | 4.3987 | |

| Superior Parietal Gyrus | Right | 63 | 16 | −68 | 64 | 4.9385 | |

| F > M | Superior Temporal Gyrus | Right | 56 | 36 | −38 | 8 | −4.9511 |

| Angular Gyrus* | Left | 552 | −38 | −72 | 38 | −4.8442 | |

| Middle Cingulate | Right | 86 | 14 | −10 | 26 | −4.1807 | |

| Middle Frontal Gyrus | Right | 100 | 34 | 24 | 30 | −4.6148 | |

| Superior Medial Frontal Gyrus | Left | 96 | −10 | 26 | 36 | −4.4574 | |

| Superior Temporal Gyrus | Right | 58 | 28 | −22 | 40 | −4.1021 | |

| Precentral Gyrus* | Right | 260 | 44 | −12 | 46 | 5.6593 | |

All results above thresholded at p < 0.005 uncorrected, k ≥ 50.

p < 0.05 corrected k ≥ 147 (see methods).

Table 2.

Functional connectivity with amygdala in response to high vs. low-ED food cues in the fasted state.

| Amygdala - Fasted | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Hemisphere | k | MNI Coordinates | t-value | |||

| x | y | z | |||||

| M > F | Parahippocampal gyrus | Left | 52 | −30 | −16 | −22 | 3.5637 |

| Cerebellum | Left | 105 | −8 | −60 | −14 | 4.1753 | |

| Precentral Gyrus* | Right | 59 | 54 | 4 | 20 | 3.6864 | |

| Left | 79 | −54 | 2 | 22 | 4.6243 | ||

| Right | 1089 | 46 | −20 | 52 | 6.0322 | ||

| Left | 191 | −34 | −22 | 62 | 4.7918 | ||

| Left | 79 | −30 | −12 | 52 | 4.476 | ||

| Cuneus* | Right | 424 | 18 | −86 | 28 | 5.4931 | |

| Supplementary Motor Area* | Right | 713 | 8 | −18 | 62 | 5.7651 | |

| Occipital Cortex | Left | 54 | −36 | −76 | 22 | 3.6159 | |

| Precuneus* | Left | 571 | −2 | −46 | 60 | 5.5583 | |

| Postcentral Gyrus | Left | 104 | −50 | −20 | 28 | 5.4904 | |

| Right | 51 | 20 | −32 | 64 | 3.9189 | ||

| Superior Parietal Gyrus | Left | 81 | −32 | −56 | 58 | 3.9338 | |

| F > M | Orbitorfrontal Cortex | Right | 89 | 26 | 16 | −26 | −4.6468 |

| Superior Temporal Pole | Right | 107 | 50 | 10 | −18 | −3.8534 | |

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus* | Left | 62 | −34 | 20 | −18 | −4.5482 | |

| Left | 157 | −46 | 20 | 8 | −5.195 | ||

| Orbitofrontal Cortex | Left | 101 | −40 | 44 | −8 | −3.6434 | |

| Thalamus* | Left | 79 | −16 | −32 | −4 | −3.4704 | |

| Right | 165 | 4 | −22 | 0 | −4.4058 | ||

| Right | 88 | 22 | −30 | 4 | −4.7169 | ||

| Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex* | Right | 201 | 4 | 26 | 50 | −4.4223 | |

All results above thresholded at p < 0.005 uncorrected, k ≥ 50.

p < 0.05 corrected k ≥ 147 (see methods).

3.3. Ventral Striatum (VS) as the “Seed” Region

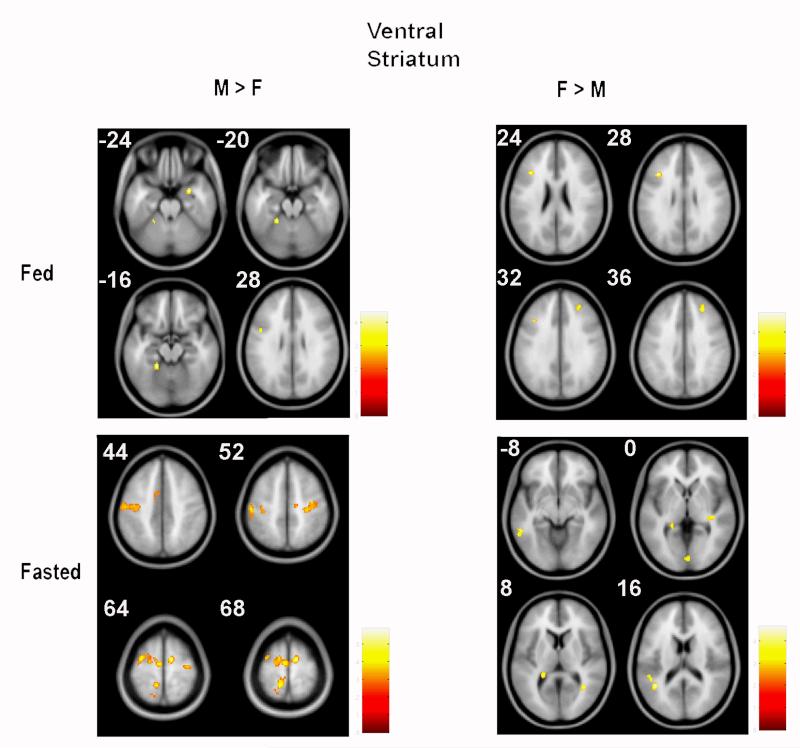

In the fed state, only sub-threshold clusters were observed for functional connectivity with VS for both obese male greater than female (M > F) (k = 101) and for obese female greater than male (F > M) (k ≥ 70) comparisons (Figure 2, Table 3). In the fasted state, greater VS functional connectivity (men vs. women) with bilateral SMA, right precentral gyrus, and left precuneus was observed. In obese female versus male (F > M) comparisons, only sub-threshold (k ≥ 70) clusters were observed for VS functional connectivity (Figure 2, Table 4).

Figure 2.

Sex-based differences in functional connectivity with ventral striatum (VS) in response to visual high vs. low-ED food cues. Top left and right: When fed, no supra-threshold clusters appeared in obese males greater than females nor for females greater than males (panels depict sub-threshold clusters; see Table 3 for labels.Bottom left: When fasted, obese males had greater neural connectivity with VS in precentral gyrus (z=44, 52), supplementary motor area (z=64, 68) and precuneus (z=68). Bottom right: When fasted, no supra-threshold clusters appeared in obese females greater than males (panels depict sub-threshold clusters; see Table 4 for labels). (M=males, F=females).

Table 3.

Functional connectivity with ventral striatum in response to high vs. low-ED food cues in the fed state.

| Ventral Striatum - Fed | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Hemisphere | k | MNI Coordinates | t-value | |||

| x | y | z | |||||

| M > F | Amygdala | Right | 54 | 28 | 0 | −26 | 4.427 |

| Cerebellum | Left | 59 | −20 | −42 | −16 | 4.1795 | |

| Cuneus | Right | 52 | 16 | −92 | 6 | 4.0347 | |

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus | Left | 101 | −46 | 4 | 24 | 4.1761 | |

| Postcentral Gyrus | Right | 57 | 54 | −30 | 56 | 3.8538 | |

| F > M | Frontal Inferior Tri | Left | 66 | −36 | 20 | 26 | −4.9206 |

| Middle Frontal Gyrus | Right | 76 | 28 | 40 | 34 | −4.1282 | |

| Superior Frontal Gyrus | Right | 74 | 22 | 22 | 56 | −4.1267 | |

All results above thresholded at p < 0.005 uncorrected, k ≥ 50 and p < 0.05 corrected k ≥ 147, thus only sub-threshold clusters were observed during fed state in VS.

Table 4.

Functional connectivity with ventral striatum in response to high vs. low-ED food cues in the fasted state.

| Ventral Striatum - Fasted | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Hemisphere | k | MINI Coordinates | t-value | |||

| x | y | z | |||||

| M > F | Supplementary Motor Area* | Left | 810 | −6 | −12 | −12 | 5.13 |

| Right | 196 | 12 | −6 | −6 | 5.835 | ||

| Middle Cingulate | Left | 51 | −8 | 4 | 42 | 3.3736 | |

| Precentral Gyrus* | Right | 317 | 30 | −26 | 56 | 4.4032 | |

| Precuneus* | Left | 187 | −12 | −48 | 68 | 4.8971 | |

| F > M | Middle Temporal Gyrus | Left | 79 | −56 | −48 | −10 | −4.199 |

| Occipital Cortex | Left | 62 | 2 | −88 | −2 | −3.8807 | |

| Hippocampus | Left | 75 | −22 | −38 | 8 | −3.8262 | |

| Insula | Right | 52 | 38 | −28 | 2 | −3.7875 | |

| Superior Temporal Gyrus | Right | 50 | 36 | −56 | 6 | −4.1194 | |

| Left | 87 | −40 | −54 | 18 | −4.6517 | ||

| Left | 51 | −48 | −42 | 14 | −4.181 | ||

All results above thresholded at p < 0.005 uncorrected, k ≥ 50.

p < 0.05 corrected k ≥ 147 (see methods).

3.4. Gender × BMI Interaction

In the fed state, there was a ‘gender × BMI’ interaction on functional connectivity with the AMG in inferior parietal lobule, middle temporal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus in obese men compared with women. A ‘Gender × BMI’ interaction in functional connectivity with AMG was also found in pre- and post-central gyrus, insula, lingual gyrus and occiptal lobe in obese women compared with men (see Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1).

In the fed state, functional connectivity of VS with supplemental motor area (SMA) was more associated with BMI in obese men (vs. women). Functional connectivity of VS with occipital lobe and middle temporal gyrus was more associated with BMI in obese women (vs. men) (see Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Table 2).

In the fasted state, there was no significant ‘gender × BMI’ interaction in functional connectivity using AMG or VS as the seed regions during visual high vs. low-ED food cues at the applied threshold.

4. Discussion

Neuroimaging studies comparing responses to food cues in obese participants have previously implicated brain areas involved in sensory and motor processing, emotion and memory, control and attention, and reward (Frank et al., 2010). However, sex-based differences in functional connectivity in response to such cues in obesity were not previously investigated. The main purpose of this study was to identify sex-dependent functional neural connectivity with key regions associated with emotion (AMG) and reward (VS) processing in response to high vs. low-ED food pictures in both fed and fasted states. We also identified regions which had functional connectivity with AMG and VS and an interaction with BMI in a sex-dependent manner. The differences between men and women in functional connections may reflect sexually dimorphic neural phenotypes related to degree of obesity.

4.1. Fed State

In the fed state, the AMG, a key region associated with processing of emotional and biologically salient stimuli, showed higher functional connectivity with regions involved in emotion regulation and negative affect (i.e., subgenual anterior cingulate) in obese men compared to women. It has been shown that anterior cingulate (ACC) processes cognitive and emotion-related information and interacts with other cortical and sub-cortical regions to regulate behavior (Bush et al., 2000). Specifically, subgenual ACC (sgACC) lies caudally to the genu region of the corpus callosum and is linked to parasympathetic autonomic drive as well as arousal and accompanying reward-based emotional/motivational processing within the orbitofrontal and medial temporal regions (Critchley, 2004). In animal studies, (sgACC) was shown to be part of a neural network that modulates autonomic/neuroendocrine and neurotransmitter responses during the processing of reward, fear, and stress (Rhodes and Killcross, 2004; Vidal-Gonzalez et al., 2006). Moreover, in humans, increased cerebral blood flow via positron emission tomography (PET) to the sgACC has been associated with sadness, and the reverse pattern was reported in recovery from depression (Mayberg et. al., 1999). Another study, using BOLD fMRI showed greater sgACC activation in adolescent patients with major depressive disorder compared to healthy adolescents (Yang et al., 2009). The same group also reported a correlation between activation in the sgACC and the severity of depressive symptoms (Matthews et al., 2009), suggesting that the sgACC plays a role in clinical depression. Several functional neuroimaging studies have suggested that the sgACC should be a specific target site for deep brain stimulation (DBS) as a treatment for depression (Johansen-Berg et al., 2008; Hamani et al., 2011). Collectively, these findings suggest that sgACC is involved in processing negative emotions.

Based on the above literature, we speculate our results may be associated with “emotional eating,” defined as the tendency to eat high-ED foods when exposed to negative emotions (Wallis and Hetherington, 2009). Emotional eaters are more likely to overeat in response to emotions rather than hunger signals or food cues from the environment (Allison and Heshka, 2006). This is termed external eating, defined as eating in response to food-related stimuli, regardless of the internal states of hunger and satiety (Van Strien et al., 1986b). Moreover, a longitudinal study (4 years) with 589 men and 619 women (Van Strien et al., 1986a) found a significant interaction between the self-reported tendency to overeat in response to negative emotions and the degree of negative stresses experienced in changes (6-month follow-up) in BMI in men but not in women. These differences may explain the increased propensity to overeat due to perceived reward value of external cues (Davis et al., 2008; Vervaet et al., 2004) and could be related to a link between obesity and depression which may be stronger in obese men than in women.

In obese women (compared to men) in the fed state, the AMG showed greater functional connectivity with angular gyrus and precentral gyrus. The angular gyrus is believed to have evolved to give upper Paleolithic males and females improved ability to engage in complex activities with temporal and sequential dimensions such as manipulation of external objects, toolmaking, and spatial skills (DeRenzi and Lucchetti, 1988; Heilman et al., 1982; Kimura, 1993). It is unique to humans (Geschwind, 1965) and, consistent with our results, is more developed in women than men, and thus, considered to be one of the markers of sexual dimorphism in the brain (Joseph, 2000). One study, using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), showed that motor areas (precentral gyrus) and the angular gyrus are involved in learning perceptual-motor responses via manual motor skills and sequential learning (Rosenthal et al., 2009). Moreover, using regional cerebral blood flow as a marker of neuronal activity via PET, Del Parigi et al. (2002) found greater angular gyrus activation in normal weight women than men during a fed state (liquid meal). We speculate that functional connectivity of perceptual (angular gyrus) and motor (precentral gyrus) regions with the AMG may reflect a higher tendency to integrate emotion processing with motor planning during high ED cues in women versus men in the fed state.

Analysis of gender × BMI interactions revealed that functional connectivity of AMG with inferior parietal lobe, middle temporal gyrus and inferior frontal gyrus during high vs. low-ED food cue processing was more associated with BMI in men. Conversely, functional connectivity of AMG with insula, lingual gyrus and pre- and post-central gyrus during high vs. low-ED food cue processing more was more associated with BMI in women. The insula is implicated in olfaction, interoception, gestation, affect, cognition and sensory motor integration and processing (Chang et al., 2013). Thus, our finding suggests that functional connectivity of this region with the amygdala is more associated with degree of obesity obesity in women. The pre and post-central gyrus was the most significant finding, with a cluster size (k) =1115 (Supplementary Table 1) and further supports the notion that an integration of emotion and motor and sensory processing during high-ED food cue processing is more associated with degree of obesity in women versus men.

Functional connectivity of VS with SMA during high vs. low-ED food cue processing was more associated with BMI in men, whereas functional connectivity of VS with middle temporal gyrus and occipital lobe was more associated with BMI in women (Supplementary Table 2). Thus, we speculate that functional connectivity of reward processing brain regions with motor planning during high-ED food cue processing is more associated with degree of obesity in women. On the other hand, functional connectivity of reward processing brain regions with sensory and sensory integration areas is more associated with degree of obesity in men.

4.2. Fasted State

In fasted obese men, the AMG showed greater functional connectivity with areas associated with motor movement organization and execution (i.e., supplementary motor area [SMA], precentral gyrus) (Roland et al., 1980) and visual recognition and attention (i.e., precuneus, cuneus). These same regions (i.e., SMA, precentral, precuneus, cuneus) were found to have greater functional connectivity with a key reward-related region, ventral striatum (VS), in obese men vs. women. Thus, when fasted, motor and visual processing regions in obese men had greater functional connectivity with emotion and reward-related regions in response to high vs. low-ED food cues

On the other hand, in fasted obese women, the AMG showed greater functional connectivity with areas typically associated with motor response inhibition and cognitive control (i.e., IFG) (Rodrigo et al., 2013), DMPFC, and the thalamus. The thalamus is a hub region integrating and relaying various ascending information (Jakab et al., 2012), and connects with the AMG via amygdalothalamic fibers that have been previously identified (Aggleton and Mishkin, 1984). The IFG has been associated with various aspects of motor-related cognitive control such as; action control and termination (Swann et al., 2012) and go/no-go tasks, in which one condition requires a motor response (e.g., manually pressing a button on a go trial) and another one inhibits a response (e.g., withholding a manual button press on a no-go trial) (Cai and Leung, 2011; Hester et al., 2004b). We also observed greater AMG-DMPFC functional connectivity in obese women versus men. The DMPFC has been implicated in conflict resolution (McLaughlin and See, 2003), response conflict monitoring (Matsuzaka et al., 2012) and reinstatement of reward seeking behavior (de Witt et al., 2006). Future studies that employ a stroop test involving food, or a related cognitive control task could be used to directly test whether these regions are involved in a sex-dependent manner in the cognitive control of food cue processing.

4.3. Conclusion

Overall, we showed that in response to high vs. low-ED food cues: In the fed state 1a) in obese men (vs. women), greater AMG functional connectivity AMG with sgACC, an area implicated in mood regulation, was observed and, 1b) obese women (vs. men) had greater AMG functional connectivity with angular, precentral and postcentral gyrus), and AMG functional connectivity with these latter motor and sensory regions was more associated with BMI in women. In the fasted state 2a) in obese men (vs. women), greater VS and AMG functional connectivity with SMA, precentral gyrus,and cuneus (i.e. regions typically associated with motor planning/execution and visual processing) was observed and 2b) obese women (vs. men) had greater AMG functional connectivity with IFG and dmPFC, regions typically associated with cognitive control.). At our applied threshold, no significant gender × BMI interaction effects were observed in the fasted state, suggesting that AMG and VS functional connectivity during satiety, but not hunger, are related to obesity in a sex-dependent manner.

We infer that in the fed state, in response to high vs. low-ED food cues, greater functional connectivity of emotion and reward-related regions with regions typically associated with sensory processing, cognitive control, motor planning and execution reflects greater neural compensation in light of less inhibitory control in women. This interpretation is consistent with previous research on obese women (Del Parigi et al., 2005), especially in those who chronically diet and become disinhibited over time (Van Strien et al., 1986b). During the fasted state, we observed almost the opposite pattern in men; higher functional connectivity of AMG and VS with motor planning and execution when processing high vs. low-ED food cues. Taken together, these findings may provide a better understanding of sex-dependent differences in the neural processing of visual high-ED food cues.

One limitation of the present study is that we did not control for menstrual cycle for female participants, which has been shown to affect appetite, mood, and performance in certain cognitive tasks (Kimura and Hampson, 1994). However, this effect was shown to be apparent only in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) (Reed et al., 2008). While experiencing some premenstrual symptoms is common in premenopausal women (Dickerson et al., 2003), only 8% of women are diagnostically considered to have PMDD (Bhatia and Bhatia, 2002 and Wittchen et al., 2002). Thus, we believe it would not have a confounding effect in our study. Secondly, although the foods chosen for presentation were common food items previously reported to be preferred by individuals (Wang et al., 2009), we did not control for differences in individual preference for the food items, which may have resulted in differential neural responses to particular food cues. We also did not directly control the energy and macronutrient content of the pre-fast meal intake of the participants, which may have affected their energy balance status: however, the self-ratings for hunger and fullness did not differ between men and women. Finally, we did not include a lean control group, which would have allowed for a direct comparison of sex-dependent functional connectivity differences between obese and lean persons.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Sex differences in neural responsivity to food cues are examined in obese people.

Neural connectivity for processing cues is assessed via fMRI using PPI analysis.

Amygdala (emotion) and ventral striatum (reward) were selected as seed regions.

In obese men, seeds interacted more with motor and emotion regions.

In obese women, seeds interacted more with cognitive processing regions

Acknowledgements

DA drafted the manuscript and analyzed descriptive, behavioral and 2nd level imaging data, SPP analyzed 1st and 2nd level imaging data and edited relevant portions of the manuscript, HM performed the experiments edited portions of the manuscript, CG provided editorial and intellectual contributions, LP performed the experiments, NA provided manuscript edits, AG was the PI and supervised the study. This study was supported by R03DK068603, R01DK074046, R01080153 (PI: Allan Geliebter). We would also like to thank Joy Hirsch for advice and contributions in designing the fMRI task design.

Abbreviations

- AMG

amygdala

- BOLD

blood oxygen level-dependent

- BMI

body mass index

- DMPFC

dorsomedial prefrontal cortex

- ED

energy-dense

- fMRI

functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- IFG

inferior frontal gyrus

- IPL

inferior parietal lobule

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PPI

psychophysiological interaction analysis

- sgACC

subgenual anterior cingulate cortex

- SMA

supplementary motor area

- VS

ventral striatum

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aggleton JP, Mishkin M. Projections of the Amygdala to the Thalamus in the Cynomolgus Monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 1984;222:56–68. doi: 10.1002/cne.902220106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison DB, Heshka S. Emotion and eating in obesity? A critical analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2006;13(3):289–295. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199304)13:3<289::aid-eat2260130307>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. [text rev.] Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Atalayer D, Rowland NE. Effort and Food Demand. In: T.L.W., editor. Progress in Economics Research. Vol. 21. Nova Science Publishers; Hauppauge, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bates CJ, Prentice A, Finch S. Gender differences in food and nutrient intakes and status indices from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey of people aged 294 65 years and over. Eur. J. of Clin. Nutr. 1999;53(9):694–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. Motivation concepts in behavioral neuroscience. Physiol. Behav. 2004;81:179–209. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR, Morrison C. The brain, appetite, and obesity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008;59:55–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia SC, Bhatia SK. Diagnosis and treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am. Fam. Phys. 2002;66:1239–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SJ, O'Daly OG, Uher R, Friederich H-C, Giampietro V, Brammer M, et al. Differential neural responses to food images in women with bulimia versus anorexia nervosa. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e22259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Luu P, Posner MI. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends in Cogn. Sci. 2000;4(6):215–22. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W, Leung H-C. Rule-Guided Executive Control of Response Inhibition: Functional Topography of the Inferior Frontal Cortex. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e20840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LJ, Yarkoni T, Khaw MW, Sanfey AG. Decoding the role of the insula in human cognition: functional parcellation and large-scale reverse inference. Cereb. Cortex. 2013;23(3):739–749. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collette F, Olvier L, Van der Linden M, Laureys S, Delfiore G, Luxen A, Salmon E. Involvement of both prefrontal and inferior parietal cortex in dual-task performance. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 2005;24(2):237–251. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornier MA, Salzberg AK, Endly DC, Bessesen DH, Tregellas JR. Sex-based differences in the behavioral and neuronal responses to food. Physiol. Behav. 2010;99:538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, Barrera JG, Seeley RJ. Leptin in energy balance and reward: two faces of the same coin? Neuron. 2006;51(6):678–680. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: Software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages computers and biomedical research. Comput. Biomed. Res. 1996;29:162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD. The human cortex responds to an interoceptive challenge. PNAS. 2004;101(17):6333–6334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401510101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Levitan RD, Carter J, Kaplan AS, Reid C, Curtis C, Patte K, et al. Personality and eating behaviors: a case-control study of binge eating disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2008;41:243–250. doi: 10.1002/eat.20499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamater AR. The role of the orbitofrontal cortex in sensory-specific encoding of associations in pavlovian and instrumental conditioning. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1121:152–173. doi: 10.1196/annals.1401.030. 20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Parigi A, Chen K, Gautier JF, Salbe AD, Pratley RE, Ravussin E, et al. Sex differences in the human brain's response to hunger and satiation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002;75:1017–22. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.6.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRenzi E, Lucchetti F. Ideational apraxia. Brain. 1988;111:1173–1185. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.5.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit S, Kosaki Y, Balleine BW, Dickinson A. Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex resolves response conflict in rats. J Neurosci. 26(19):5224–5229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5175-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A. Developmental time course in human infants and infant monkeys, and the neural bases of, inhibitory control in reaching. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1990;608:637–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb48913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson LM, Mazyck PJ, Hunter MH. Premenstrual syndrome. Am. Fam. Phys. 2003;67:1743–1752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Cador M, Robbins TW. Interactions between the amygdala and ventral striatum in stimulus-reward associations: Studies using a second-order schedule of sexual reinforcement. Neuroscience. 1989;30(1):63–75. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90353-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein EA, Khavjou OA, Thompson H, Trogdon JG, Pan L, Sherry B, Dietz W. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. Am. J. of Prev. Med. 2012;42(6):563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1960-1994. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1998;22:39–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PC, Napolitano A, Skeggs A, Miller SR, Delafont B, Cambridge VC, et al. Distinct modulatory effects of satiety and sibutramine on brain responses to food images in humans: a double dissociation across hypothalamus, amygdala, and ventral striatum. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:14346–14355. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3323-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folope V, Chapelle C, Grigioni S, Coëffier M, Déchelotte P. Impact of eating disorders and psychological distress on the quality of life of obese people. Nutrition. 2012;28:e7–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S, Laharnar N, Kullmann S, Veit R, Canova C, Hegner YL, et al. Processing of food pictures: influence of hunger, gender and calorie content. Brain. Res. 2010;1350:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Buechel C, Fink GR, Morris J, Rolls E, Dolan RJ. Psychophysiological and modulatory interactions in neuroimaging. Neuroimage. 1997;6:218–229. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavan H, Hester R, Murphy K, Fassbender C, Kelly C. Individual differences in the functional neuroanatomy of inhibitory control. Brain Res. 2006;1105:130–142. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geliebter A, Pantazatos SP, McOuatt H, Puma L, Gibson CD, Atalayer D. Sex-based fMRI differences in obese humans in response to high vs. low energy food cues. Behav. Brain. Resea. 2013;243:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geschwind N. Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man. Brain. 1965;88:585–644. doi: 10.1093/brain/88.3.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodpaster BH, Krishnaswami S, Harris TB, Katsiaras A, Kritchevsky SB, Simonsick EM, et al. Obesity, regional body fat distribution, and the metabolic syndrome in older men and women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005;165:777–783. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.7.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase L, Cerf-Ducastel B, Murphy C. Cortical activation in response to pure taste stimuli during the physiological states of hunger and satiety. Neuroimage. 2009;44(3):1008–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase L, Green M, Murphy C. Males and females show differential brain activation to taste when hungry and sated in gustatory and reward areas. Appetite. 2011;57(2):421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.06.009. 2011 October. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamani C, Mayberg H, Stone S, Laxton A, Haber S, Lozano AM. The subcallosal cingulate gyrus in the context of major depression. Biol. Psychiat. 2011;69(4):301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilman KM, Rothi LJ, Valenstein E. Two forms of ideomotor apraxia. Neurology. 1982;32:342–346. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester R, Fassbender C, Garavan H. Individual differences in error processing: a review and reanalysis of three event-related fMRI studies using the GO/NOGO task. Cereb. Cortex. 2004a;14:986–994. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RL, Murphy K, Foxe JJ, Foxe DM, Javitt DC, Garavan H. Predicting success: patterns of cortical activation and deactivation prior to response inhibition. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2004b;16:776–785. doi: 10.1162/089892904970726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi R, Lambon RMA, Saito S, Pobric G. Different roles of lateral anterior temporal lobe and inferior parietal lobule in coding function and manipulation tool knowledge: Evidence from an rTMS study. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(5):1128–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakab A, Blanc R, Berényi EL. Mapping changes of in vivo connectivity patterns in the human mediodorsal thalamus: correlations with higher cognitive and executive functions. Brain Imaging Behav. 2012;6(3):472–483. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen-Berg H, Gutman DA, Behrens TE, Matthews PM, Rushworth MF, Katz E, et al. Anatomical connectivity of the subgenual cingulate region targeted with deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Cereb. Cortex. 2008;18:1374–1383. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph R. The evolution of sex differences in language, sexuality, and visual-spatial skills. Arch. Sex Behav. 2000;29:35–66. doi: 10.1023/a:1001834404611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WDS, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Sex differences in cerebral responses to images of high vs low calorie food. Neuroreport. 2010;21:354–358. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32833774f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WDS, Weber M, Schwab ZJ, Kipman M, DelDonno SR, Webb CA, Rauch SL. Cortico-limbic responsiveness to high-calorie food images predicts weight status among women. Int. J. Obes. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.26. (Ahead of print) doi:10.1038/ijo.2013.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WDS, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Body mass predicts orbitofrontal activity during visual presentations of high-calorie foods. NeuroReport. 2005;16(8):859–863. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200505310-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach ML, O'Doherty J, Rolls ET, Andrews C. Sensory-specific satiety for the flavour of food is represented in the orbitofrontal cortex. NeuroImage. 2000;11(5):S767. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura D. Neuromotor Mechanisms in Human Communication. Oxford University Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura D, Hampson E. Cognitive Pattern in men and women is influenced by fluctuations in sex hormones. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1994;3(2):57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lenard NR, Berthoud HD. Central and peripheral regulation of food intake and physical activity: pathways and genes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:S11–22. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Huang C, Constable RT, Sinha R. Gender differences in the neural correlates of response inhibition during a stop signal task. NeuroImage. 2006;32:1918–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaka Y, Akiyama T, Tanji J, Mushiakea H. Neuronal activity in the primate dorsomedial prefrontal cortex contributes to strategic selection of response tactics. PNAS. 2012;12(109):4633–4638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119971109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews S, Simmons A, Strigo I, Gianaros P, Yang T, Paulus M. Inhibition-related activity in subgenual cingulate is associated with symptom severity in major depression. Psychiatry Res. 2009;172(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Liotti M, Brannan SK, McGinnis S, Mahurin RK, Jerabek PA, et al. Reciprocal limbic-cortical function and negative mood: converging PET findings in depression and normal sadness. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1999;156:675–682. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin J, See RE. Selective inactivation of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and the basolateral amygdala attenuates conditioned-cued reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168(1-2):57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Dolan RJ. Involvement of human amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex in hunger-enhanced memory for food stimuli. J Neurosci. 2001;21(14):5304–5310. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05304.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller K, Anwander A, Möller HE, Horstmann A, Lepsien J, Busse F, et al. Sex-dependent influences of obesity on cerebral white matter investigated by diffusion-tensor imaging. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Doherty JP, Buchanan TW, Seymour B, Dolan RJ. Predictive neural coding of reward preference involves dissociable responses in human ventral midbrain and ventral striatum. Neuron. 2006;49:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009-2010. NCHS Data. Brief. 2012;82:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostlund SB, Balleine BW. The contribution of orbitofrontal cortex to action selection. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1121:174–192. doi: 10.1196/annals.1401.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passamonti L, Rowe JB, Schwarzbauer C, Ewbank MP, von dem Hagen E, Calder AJ. Personality predicts the brain's response to viewing appetizing foods: The neural basis of a risk factor for overeating. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:43–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4966-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelchat ML, Johnson A, Chan R, Valdez J, Ragland JD. Images of desire: food-craving activation during fMRI. Neuroimage. 2004;23(4):1486–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power ML, Schulkin J. Sex differences in fat storage, fat metabolism, and the health risks from obesity: possible evolutionary origins. Br. J. Nutr. 2008;99:931–940. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507853347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SC, Levin FR, Evans SM. Changes in mood, cognitive performance and appetite in the late luteal and follicular phases of the menstrual cycle in women with and without PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder). Horm. Behav. 2008;54(1):185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SE, Killcross S. Lesions of rat infralimbic cortex enhance recovery and reinstatement of an appetitive Pavlovian response. Learn. Mem. 2004;11:611–616. doi: 10.1101/lm.79704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo AH, Di Domenico SI, Ayaz H, Gulrajani S, Lam J, Ruocco AC. Differentiating functions of the lateral and medial prefrontal cortex in motor response inhibition. NeuroImage. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.059. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rogers RD, Owen AM, Middleton HC, Williams EJ, Pickard JD, Sahakian BJ, et al. Choosing between Small, Likely Rewards and Large, Unlikely Rewards Activates Inferior and Orbital Prefrontal Cortex. J. Neurosci. 1999;19(20):9029–9038. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-09029.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland PE, Larsen B, Lassen NA, Skinhoj E. Supplementary motor area and other cortical areas in organization of voluntary movements in man. AJP - JN Physiol. 1980;43(1):118–136. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.43.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. Plenary Lecture: Sensory processing in the brain related to the control of food intake. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2007;66:96–112. doi: 10.1017/S0029665107005332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Grabenhorst F. The orbitofrontal cortex and beyond: From affect to decision-making. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;86(3):216–244. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal CR, Roche-Kelly EE, Husain M, Kennard C. The response-dependent contributions of human primary motor cortex and angular gyrus to manual and perceptual sequence learning. J Neurosci. 2009;29(48):15115–15125. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2603-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothemund Y, Preuschhof C, Bohner G, Bauknecht HC, Klingebiel R, Flor H, et al. Differential activation of the dorsal striatum by high-calorie visual food stimuli in obese individuals. Neuroimage. 2007;37(2):410–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A, Schäfer A, Hermann A, Vaitl D. Binge-eating disorder: reward sensitivity and brain activation to images of food. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;65:654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seim HC, Fiola JA. A comparison of attitudes and behaviors of men and women toward food and dieting. Fam. Pract. Res. J. 1990;10:57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma AM, Kushner RF. A proposed clinical staging system for obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2009;33:289–295. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets PA, de Graaf C, Stafleu A, van Osch MJ, Nievelstein RA, van der Grond J. Effect of satiety on brain activation during chocolate tasting in men and women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006;83:1297–1305. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellar E. The Physiology of Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1994;101(2):301–311. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckel LE, Cox JE, Cook EW, 3rd, Weller RE. Motivational state modulates the hedonic value of food images differently in men and women. Appetite. 2007;48:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuphorn V. Neuroeconomics: Cardinal utility in the orbitofrontal cortex? Curr. Biol. 2006;16(15):R591–R593. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann NC, Cai W, Conner CR, Pieters TA, Claffey MP, George JS, et al. Roles for the pre-supplementary motor area and the right inferior frontal gyrus in stopping action: Electrophysiological responses and functional and structural connectivity. NeuroImage. 2012;59(3):2860–2870. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien T, Rookus MA, Bergers GP, Frijters JER, Defares PB. Life events, emotional eating and change in body mass index. Int. J. Obes. 1986a;20:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien T, Frijters JE, Bergers GP, Defares PB. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986b;5:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Vervaet M, van Heeringen C, Audenaert K. Personality-related characteristics in restricting versus binging and purging eating disordered patients. Compr. Psychiatry. 2004;45:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Gonzalez I, Vidal-Gonzalez B, Rauch SL, Quirk GJ. Microstimulation reveals opposing influences of prelimbic and infralimbic cortex on the expression of conditioned fear. Learn. Mem. 2006;13:728–733. doi: 10.1101/lm.306106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uher R, Treasure J, Heining M, Brammer MJ, Campbell IC. Cerebral processing of food-related stimuli: effects of fasting and gender. Behav. Brain Res. 2006;169:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis DJ, Hetherington MM. Emotions and eating. Self-reported and experimentally induced changes in food intake under stress. Appetite. 2009;52:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States--gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol. Rev. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G-J, Volkow ND, Telang F, Jayne M, Ma Y, Pradhan K, et al. Evidence of gender differences in the ability to inhibit brain activation elicited by food stimulation. PNAS. 2009;106:1249–1254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807423106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weygandt M, Mai K, Dommes E, Leupelt V, Hackmack K, Kahnt T, et al. The role of neural impulse control mechanisms for dietary success in obesity. Neuroimage. 2013;83:669–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Becker E, Lieb R, Krause P. Prevalence, incidence and stability of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the community. Psychol. Med. 2002;32:119–132. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TT, Simmons AN, Matthews SC, et al. Depressed adolescents demonstrate greater subgenual anterior cingulate activity. Neuroreport. 2009;20(4):440–444. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283262e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Wang Y. Trends in the associations between obesity and socioeconomic status in U.S. adults: 1971-2000. Obesity Research. 2012;12:1622–1632. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.