Abstract

An emerging literature suggests that temporary deficits in the ability to inhibit impulsive urges may be proximally associated with intimate partner aggression. The current study examined the experience of alcohol use and the depletion of self-control in the prediction of relationship functioning. Daily diary data collected from 118 heterosexual couples were analyzed using parallel multi-level Actor Partner Interdependence Models to assess the effects of heavy episodic drinking and depletion of self-control across partners on outcomes of participant-reported daily arguing with and anger toward an intimate partner. Heavy episodic drinking among actors predicted greater arguing but failed to interact with either actor or partner depletion. We also found that greater arguing was reported on days of high congruent actor and partner depletion. Both actor and partner depletion, as well as their interaction, predicted greater partner-specific anger. Greater partner-specific anger was generally reported on days of congruent actor and partner depletion, particularly on days of high partner depletion. The current results highlight the importance of independently assessing partner effects (i.e., depletion of self-control), which interact dynamically with disinhibiting actor effects, in the prediction of daily adverse relationship functioning. Results offer further support for the development of prospective individualized and couples-based interventions for partner conflict.

Keywords: conflict, anger, self-control, heavy episodic drinking, actor-partner interdependence

Within intimate partnerships, individuals are generally capable of amicably processing and interpreting social stimuli as well as engaging in accommodative behaviors by inhibiting the urge to reciprocate following the interpretation of behavior as adversarial (Finkel, 2008; Gottman, 1998). Nevertheless, conflict represents a normative component of intimate partnerships, with up to 85% of partners reporting verbal aggression within a current relationship (Finkel & Eckhardt, in press; Schluter, Paterson, & Feehan, 2007). Engaging in behaviors that instigate or exacerbate conflict with one’s partner may represent an interpersonal style for some, but situational and contextual factors may influence such behaviors for the majority of romantic partners (Finkel & Campbell, 2001). An emerging literature suggests that temporary deficits in the ability to inhibit impulsive urges may account for adversarial, non-accommodative behavior and affect that is contrary to one’s greater self-interests (DeWall, Finkel, & Denson, 2011). The current investigation explores daily fluctuations in self-control and heavy alcohol consumption as proximally disinhibiting factors that may be associated with arguing and partner-specific anger.

Depletion of Self-control

The Self-control Strength Model describes self-control as a limited resource essential in the process of selecting behavioral responses that conform to societal norms or individually imposed limits in the presence of more appealing or immediately gratifying options (Baumeister, Vohs, & Tice, 2007; Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). Self-control is, therefore, an essential component involved in the inhibition of impulses that, if enacted, would be likely to result in detrimental long-term consequences across any number of life domains. Baumeister (2003) evaluated three competing theories of self-control to conclude that the construct was, indeed, a limited and depletable resource rather than a static cognitive process or learned skill. Self-control strength is highly variable and dependent on the individual’s processing of current and recent stimuli (Baumeister, 2003).

Self-control depletion describes a state in which the likelihood of inhibiting impulsive or adversarial responding decreases as stressors, both extraordinary and mundane, or overexertion of willpower temporarily diminish an individual’s finite amount of self-control (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). Periods of depletion have been associated with temporary impairment of executive functioning, including a reduced capability to enact or maintain goal directed behaviors and deficits in inhibitory control. The experimental depletion of self-control has been associated with a wide range of negative outcomes, including consumption of high caloric foods (Vohs & Heatherton, 2000) as well as greater-than-intended alcohol and nicotine use (Christiansen, Cole, & Field, 2012; Muraven, Collins, & Nienhaus, 2002; Shmueli & Prochska, 2009). Further, self-control depletion seems to exert comparable effects on males and females. Stucke and Baumeister (2006), for example, found similar rates of aggressive behavior following self-control depletion across 55 males and 113 females involved in 3 separate experimental manipulations.

Depletion of self-control has also been applied to the study of close relationships. Finkel and Campbell (2001) found, across four studies, that partners with low, compared to high, dispositional self-control were less likely to engage in accommodative behaviors or inhibit negative urges. Retrospective reports and laboratory manipulation further revealed that participants who had undergone recent depletion tasks were less likely to engage in accommodative behaviors than participants who have not undergone such tasks. In a separate study, Finkel and colleagues (2009, Study 4) randomly assigned partners from heterosexual couples to a depletion (n=33) or a control (n=33) condition. They reported greater aggressive behavioral responding toward an intimate partner following provocation among participants exposed to the depletion task relative to control participants.

The role of self-control in anger experience, a natural precipitant to aggressive behavior often conceptualized as “provocation” in laboratory paradigms, is less clear. Muraven and Baumeister (2000) summarized a series of studies suggesting that affective experience failed to mediate the relationship between manipulations of self-control strength and aggression in brief, laboratory experiments. Berkowitz (2012), however, has argued in support of direct “ironic” effects, whereby depletion resulting from initially successful attempts to suppress negative affect may result in the prolonged experience of anger-related thought content (Burns et al., 2008; Wegner, Erber, & Zanakos, 1993 ). Additionally, efforts to restructure, cope with, or reconcile hostile and angry thoughts require effortful self-control (e.g., Berkowirtz, 2012; Digiuseppe & Tafrate, 2001) and may theoretically be impaired during periods of high self-control depletion.

Together, the self-report, observational, and experimental data offer compelling support for the direct effects of depletion on one’s own aversive relationship behaviors and feelings. Further research is needed to clarify the relationship between self-control depletion and anger experience as they occur under real-world conditions. Specifically, the effects of an interaction between depletion of self-control for both intimate partners on relationship functioning at the daily level have not been considered. There is, however, reason to believe that the dispositional self-control of both partners may influence relationship outcomes. In a recent study, Vohs and colleagues (2011) determined that summed husband and wife trait self-control scores were consistent predictors of positive relationship outcomes, including forgiveness, satisfaction, and less frequent conflict.

Heavy Episodic Drinking (HED)

In addition to the depletion of self-control, alcohol intoxication has received considerable attention as a proximal behavioral disinhibitor and has demonstrated robust effects on partner conflict above and beyond light or infrequent drinking (Leonard, 2005; Testa, Quigley, & Leonard, 2003). The relationship between HED, as opposed to any alcohol use, and partner conflict has been well-established. The Proximal Effects Model posits that the psychopharmacological effects of alcohol, at high doses, temporarily impair normal executive functioning and result in cognitive distortions, attention and social information processing problems, deficits in logical reasoning, and behavioral disinhibition that increase the likelihood of aggressive responding (Giancola, 2004). Jacob and Leonard (1988) observed increases in negativity from sober-to-alcohol sessions among couples engaged in a marital interaction paradigm. In a separate investigation, Leonard and Roberts (1998) reported that both husbands and wives interacted more negatively toward one another during a similar couples interaction after the husband had received sufficient alcohol to raise his blood alcohol level to .08. Negativity among control couples, who received no alcohol, failed to increase over time. Eckhardt (2007) manipulated alcohol consumption among a sample of 46 maritally violent men to conclude that alcohol administration resulted in increased self-reported anger experience following provocation and that anger expression, in the form of aggressive verbalizations following provocation by a simulated romantic partner, doubled among those who had consumed alcohol relative to sober and placebo controls. Most recently, Testa and Derrick (in press) found that within a sample of community couples, over 56 days of daily reports, alcohol consumption increased the odds of verbal and physical aggression occurring over the subsequent four hours.

The Current Investigation

The recent I3 Model, a meta-theoretical account of potential precipitants to partner conflict and aggression (Finkel, 2008), convincingly argues that relationship conflict results from a combination of instigating triggers (provocation), impelling forces, and disinhibiting factors present within specific situations. Evidence suggests that interactions between and within the three components affect conflict such that escalation is more likely to occur in the presence of multiple forces (for a review, see Finkel & Eckhardt, in press). Thus, it is possible that interactions among one’s heavy alcohol use (i.e., disinhibition), one’s own depletion (i.e., disinhibition), and the depletion of one’s partner (i.e., instigation) may be associated with arguing and partner-specific anger at the daily level.

The effects of depletion of both participants and partners as well as the effects of HED were examined as predictors of daily relationship functioning. It was predicted that 1) greater arguing and anger would be reported on days of a) the participant’s own reported depletion of self-control b) the intimate partner’s self-reported depletion of self-control, or c) episodes of HED among participants. Given the existing evidence that suggests potential cumulative effects of the I3 factors, 2) it was expected that partner depletion would moderate the association between actor depletion and negative relationship functioning such that the association would be stronger on days of high, rather than low, partner depletion. It was further predicted that 3) HED would moderate the association between actor depletion and daily relationship functioning such that the association between depletion and functioning would be stronger on days of HED relative to days of moderate or no drinking. Lacking sufficient empirical support for gender effects on the associations among relationship functioning, HED, and the depletion of self-control, exploratory analyses were pursued but no a priori hypotheses were advanced for gender differences among main effects or interactions.

Method

Participants

The data presented in this article are one component of a larger study on the association between alcohol use and partner aggression within dyads (Testa & Derrick, in press). This study was approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board. Participants discussed in this article include 118 heterosexual couples recruited through local advertisements and household mailers in the greater Buffalo area. Information included in the solicitations was identical across recruitment methods. Interested prospective participants contacted laboratory personnel using the telephone number or e-mail address provided on all solicitations. Subsequent telephone screenings began with verbal informed consent then assessed alcohol consumption and relationship aggression. Eligible participants consumed alcohol on a weekly basis and engaged in heavy episodic drinking (at least 4 drinks for females and 5 drinks for males) one or more times per month. All participants were initially screened for a separate laboratory study and, thus, were excluded if either partner reported severe partner violence or medical contraindications to alcohol consumption. The majority of couples (96) participated in the laboratory study on alcohol and conflict 6 months prior to matriculation into the current investigation.

Male (M=33.9, SD=6.78) and female (M=32.7, SD=6.92) partners ranged in age from 21 to 46 years. Two-hundred twenty-two participants in the sample self-identified as Caucasian (94.1%) with nine participants identifying as African American (3.8%) and 2 as Asian (0.9%). All participants were either married (75.9%) or cohabitating (24.2%) and most reported having children (63.1%), having attended post-secondary education (91.1%), and either full (68.6) or part (15.3%) time employment.

Procedure

Interested and eligible participants were mailed a packet containing multiple self-report questionnaires, including the 78-item Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996), the most commonly used and well-validated self report measure of past year relationship violence. Participants were instructed to complete the packet and return it via mail prior to a 45 minute orientation/training session. Couples reported for the orientation/training session together, completed written informed consent procedures, received training on estimating standard drink sizes, and were instructed on the use of the interactive voice response (IVR) touchtone system as the method of submitting daily responses. Participants were instructed to complete the 5 minute reports independently and at the same time each day. Participants were then asked to submit the first entry before the conclusion of the training session. While it was suggested that participants complete their entries early in the day, their actual responses were relatively evenly distributed between the hours of 6 AM and 11 PM. Couples received weekly calls to encourage continued compliance. Although participants were permitted to submit late entries, we used only same day reports of self-control and relationship experiences to prevent the possibility of next-day interference with retrospective reports of these subjective data. Thus, for the purposes of the current study, only the 10,448 (79.06%) complete reports submitted on time (i.e. within the 24 hour window) by both partners were retained for analyses. Participants received $1.00 for each entry and bonuses in the amount of $10.00 for each complete week and $30.00 for full compliance over the 8-week study.

Daily Measures

Each partner independently completed daily reports, which included items designed to assess daily affect, relationship conflict, and alcohol consumption. For the purposes of the current study, two items were rated on a 1 to 5 scale and used to assesses the affective component of self-control depletion: “stressed” and “overwhelmed” (α=87). They were averaged to create the measure of depletion used in the current study. Previous daily diary studies have used a similar, 4-item set (how stressed did you feel, how overwhelmed did you feel, how much did you regulate your mood, and how much did you control your thoughts [α=75]) to assess daily demands on self-regulation as a measure of self-control depletion (Muraven, Collins, Shiffman, & Paty, 2005). Such affective experiences have proven to be reliable indicators of depletion (for a review, see Hagger, Wood, Stiff, & Chatzisarantis, 2010).

Participants also responded to two items assessing daily relationship functioning: arguing with (“How much did you and your partner argue or disagree”) and anger toward (“how angry or irritated do you feel toward your partner”) a partner using the same 5-point scale. Finally, participants were asked if, how much, and at what hour they had consumed alcohol on the previous day. Using standards set by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1995), heavy episodic drinking (HED) was defined as 4 or more standard drinks for females and 5 or more standard drinks for males. The alcohol quantity variable was lagged and converted to a dichotomous variable to achieve complete same-day reports of HED, depletion, and relationship functioning.1 To ensure that HED occurred before reports of arguing and anger, consistent with our model, only alcohol consumption that occurred temporally prior to the time of the daily report was considered a viable drinking episode. HED episodes that occurred after assessment of depletion and relationship functioning were omitted from analyses (e.g., Moore et al., 2011; Parks et al., 2008). The majority (93%) of valid HED report days included entries made after 5:00pm, and 50% were submitted after 9:00pm.

Data Analysis

Parallel multilevel models predicting daily arguing and anger as continuous outcomes, were tested with the Mixed procedure in SPSS using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). APIM is well-suited to dyadic data because it accounts for the inherent non-independence of data within couples, assuming that an actor’s outcome may be influenced by both actor and partner variables. A two-level structure was used with daily reports and individuals crossed at the lowest level of analysis and nested under couples at Level 2, as suggested by Laurenceau and Bolger (2005). Initial analyses revealed that individuals within dyads were systematically identifiable by gender (see Kenny et al., 2006), so we included gender as a main effect and interaction in the resultant models to explore differences in the relationship between depletion and relationship functioning among male and female partners. Self-reported, same-day actor heavy episodic drinking (dichotomous), actor self-control depletion (continuous), and partner self-control depletion (continuous) were entered as within-subjects factors. Control variables were tested, and it was determined that actor and partner IPV perpetration history, as well as weekend (vs. weekday) reporting, were significantly associated with daily reports of relationship functioning.2 These control variables were included in all APIM analyses.3 Significant two and three-way interactions were interpreted using simple slope analyses.

A full model was first estimated and then trimmed for parsimony and stability based upon both theoretical rationale and the significance of specific interactions. The representative model depicting the analyses described above is presented as follows:

Actor Arguingijk = π0ij + π1ij (gender)ij + π2ij (Actor Depletion)ijk + π3ij (Partner Depletion)ijk + π4ij (Actor Heavy Episodic Drinking)ijk + π5ij (Gender × Actor Depletion)ijk + π6ij (Gender × Partner Depletion)ijk + π7ij (Gender × Actor Heavy Episodic Drinking) ijk + π8ij(Actor Depletion × Partner Depletion)ijk + π9ij (Actor Depletion × Heavy Episodic Drinking)ijk + π10ij (Gender × Actor Depletion × Partner Depletionijk) + eijk

Where Actor Arguingijk represents the reported arguing on day k for Actor i in couple j. π 0ij is the expected amount of arguing for person i in couple j at grand mean levels of continuous variables and on days of no binge drinking while π 1ij represents the partial regression coefficient for the gender of person i in couple j. The partial within-subject regression coefficient for the depletion of actor i in couple j on day k is described by π2ij; and so forth.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

On average, actors reported low levels of daily arguing (M=1.20, SD=0.58) and anger (M=1.36, SD=0.79) across the 8 week study period. There was modest but significant agreement between male and female partners on the severity of arguing (r=.31, p<.001) and anger (r=27, p <.001) experienced on any given day. Participant-reported self-control depletion was low across the study period (M=1.71, SD =0.96). Daily reports of actor and partner depletion were also significantly, though modestly, correlated. Males, on average, reported greater depletion of self-control, arguing, and partner-specific anger than females (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bivariate relationships and gender-specific descriptive data for primary daily variables

| Study Variables | Study Variables |

Means (SD) |

t | p | d | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Males | Females | ||||

| 1. Actor Depletion | -- | .11* | .25* | .38* | 1.77 (0.99) | 1.65 (0.93) | 6.29 | <.001 | 0.82 |

| 2. Partner Depletion | -- | .10* | .12* | 1.65 (0.93) | 1.77 (0.99) | −6.29 | <.001 | −0.82 | |

| 3. Arguing | -- | .52* | 1.21 (0.58) | 1.18 (0.57) | −2.48 | .01 | −0.32 | ||

| 4. Anger Experience | -- | 1.36 (0.78) | 1.36 (0.80) | −0.07 | .94 | 0.00 | |||

Note:

p<.001

Alcohol consumption was highly variable across the current sample. Two participants reported no episodes of drinking and 36 (15.25%) reported no episodes of HED. Participants reported consuming alcohol in 4,106 (39.30%) entries with an average consumption of 3.30 (SD=2.72) drinks per drinking day. Heavy drinking was reported on 1,057 (10.12%) days with 299 episodes occurring prior to the submission of daily logs. Analyses of HED effects are restricted to those days in which drinking occurred prior to the daily report.

APIM Analyses of Actor-Reported Ratings for Arguing

The results of the trimmed base model predicting arguing from gender, actor HED, actor depletion, partner depletion, all covariates, and significant interactions are presented in Table 2. Consistent with hypotheses, the main effect of actor daily HED emerged as a significant predictor of daily arguing, indicating that actors reported greater arguing on days of heavy drinking relative to days of no or moderate drinking. Also as expected, actor depletion was significantly associated with arguing. The main effects of gender and partner depletion failed to reach significance. However, we also detected 2-way interactions between gender and actor depletion, between gender and partner depletion, and between actor depletion and partner depletion. These main effects and interactions were all qualified by a significant gender X actor depletion X partner depletion three-way interaction, as described below. HED failed to moderate the relationship between actor depletion and arguing (b=.02, p=.47, 95% CI=−.02–.09) and the interaction was removed in the trimmed model.

Table 2.

Actor and Partner effects predicting daily arguing.

| Parameter | b | SE | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

|||||

| Intercept | 1.11 | .01 | 102.49 | <.001 | 1.09 | 1.13 |

| Actor Perpetration History | 0.06 | .01 | 4.30 | <.001 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Partner Perpetration History | 0.05 | .01 | 4.00 | <.001 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| Weekday | 0.08 | .01 | 6.18 | <.001 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| Gender | 0.01 | .01 | 1.42 | .16 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| A Depletion | 0.15 | .01 | 17.64 | <.001 | 0.13 | 0.16 |

| P Depletion | 0.01 | .01 | 1.33 | .18 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| A Heavy Episodic Drinking | 0.07 | .03 | 2.07 | .04 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| A Depletion x P Depletion | 0.03 | .01 | 4.70 | <.001 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Gender x | ||||||

| A Depletion | −0.03 | .01 | −2.37 | .02 | −0.05 | −0.00 |

| P Depletion | 0.05 | .01 | 4.26 | <.001 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| A depletion x P Depletion | 0.02 | .01 | 2.79 | .01 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

Note: A = Actor, P = Partner

Cross-partner interaction

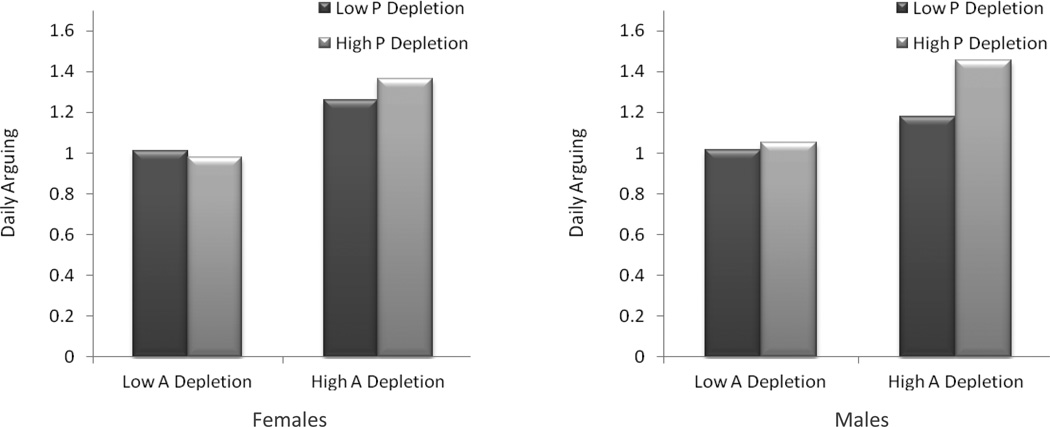

The 3-way gender X actor depletion X partner depletion interaction is displayed in Figure 1. Simple slope analyses revealed a significant interaction effect between actor depletion and partner depletion among both female (b=.03, p<.001, 95% CI = .02–.05) and male (b=.06, p<.001, 95% CI = .04-.07) participants. Among females, actor depletion was significantly and positively associated with arguing on high partner depletion days (b=.19, p<.01, 95% CI=.17–.21). This association was still significant, but weaker, on low partner depletion days (b=.12, p<.01, 95% CI=.10–.14). Similarly, among males the association between actor depletion and arguing was significant and positive on high partner depletion days (b=.20, p<.01, 95% CI=.17–.22). This effect was still significant, but weaker, on low partner depletion days (b=.08, p<.01, 95% CI=.06-.10). Among both female and male actors, partner depletion was positively associated with arguing on high actor depletion days (b=.05, p<.01, 95% CI=.03–.07; b=.14, p<.01, 95% CI=.11–.16, respectively). This association was not significant on low actor depletion days (b=−.01, p=.15, 95% CI=−.03–.07; b=.02, p=.09, 95% CI=.00–.04, respectively).

Figure 1.

Arguing as a function of gender, actor self-control, and partner self-control. A = Actor, P = Partner.

In a separate set of simple slope analyses examining gender differences based upon the configurations of actor and partner depletion, males and females reported comparable ratings of arguing (b=.01, p=.46, 95% CI=−.02–.04) on days of congruent, low actor and low partner depletion. Males reported greater arguing than females on days of high partner-only depletion (b=.01, p<.01, 95% CI=.03-.12). Males also reported greater arguing than females on days of both high actor and high partner depletion (b=.08, p<.01, 95% CI=.04-.13). Females reported greater arguing than males on days of high actor-only depletion (b=−.08, p<.01, 95% CI=−.13--.03).

Thus, actor depletion was consistently associated with arguing, and this effect was exacerbated on days of high partner depletion. However, high partner depletion was associated with greater arguing only when actors reported depletion. Finally, the effects of partner depletion on arguing were stronger among males than females.

APIM Analyses of Actor Reported Anger Experience

Similar analyses were conducted using anger instead of arguing as the outcome. The results of the trimmed model predicting partner-specific anger from gender, actor HED, actor depletion, partner depletion, all covariates, and significant interactions are presented in Table 3. As expected, both actor and partner depletion were significantly associated with daily anger experience, with days of high depletion associated with greater anger. Significant 2-way interactions were detected between gender and partner depletion as well as between actor depletion and partner depletion, as described below. The main and interactive effects of HED failed to reach significance, indicating that anger experience behaved independently of heavy alcohol use in the current sample.

Table 3.

Actor and Partner effects predicting daily partner-specific anger experience.

| Parameter | b | SE | t | p | 95% Confidence Interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

|||||

| Intercept | 1.25 | .01 | 88.75 | <.001 | 1.22 | 1.28 |

| Actor Perpetration History | 0.13 | .02 | 7.24 | <.001 | 0.10 | 0.17 |

| Partner Perpetration History | 0.07 | .02 | 3.82 | <.001 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| Weekday | 0.09 | .02 | 5.88 | <.001 | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| Gender | −0.02 | .01 | −1.81 | .07 | −0.05 | 0.00 |

| A Depletion | 0.31 | .01 | 27.41 | <.001 | 0.28 | 0.33 |

| P Depletion | 0.03 | .01 | 2.49 | .01 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| A Heavy Drinking | 0.06 | .04 | 1.51 | .13 | −0.02 | 0.15 |

| A Depletion x P Depletion | 0.02 | .01 | 3.30 | .001 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Gender x | ||||||

| A Depletion | −0.02 | .02 | −1.15 | .25 | −0.05 | 0.01 |

| P Depletion | 0.05 | .01 | 3.62 | <.001 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

Note: A = Actor, P = Partner

Gender Interaction

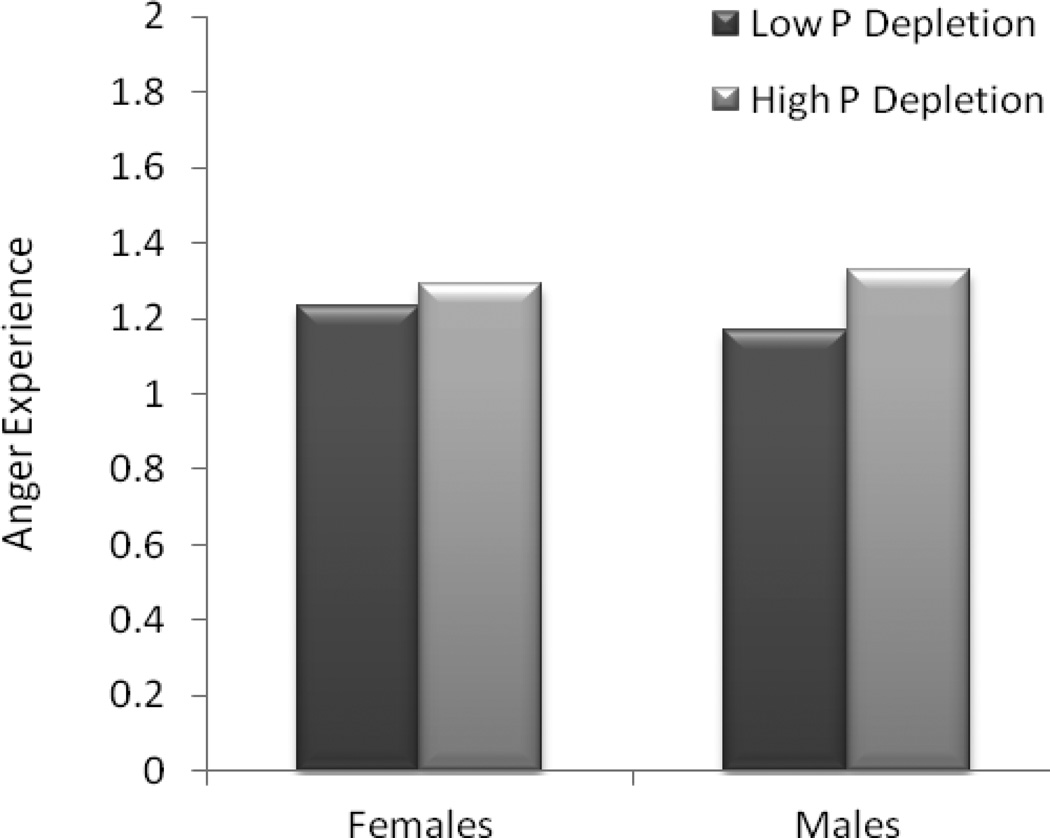

Interpretation of the gender X partner depletion interaction revealed that male anger was more sensitive to partner depletion than female anger. The daily association between partner depletion and actor anger was significant and positive for males (b=.08, p<.01, 95% CI=.06-.10). This association was also significant, but weaker, for females (b=.03, p=.01, 95% CI=.01-.05). Males reported less partner-specific anger than females on days of low partner depletion (b=−.06, p<.01, 95% CI=−.09--.03). Conversely, males reported greater partner-specific anger than females on days of high partner depletion (b=.04, p=.04, 95% CI=.00-.09).

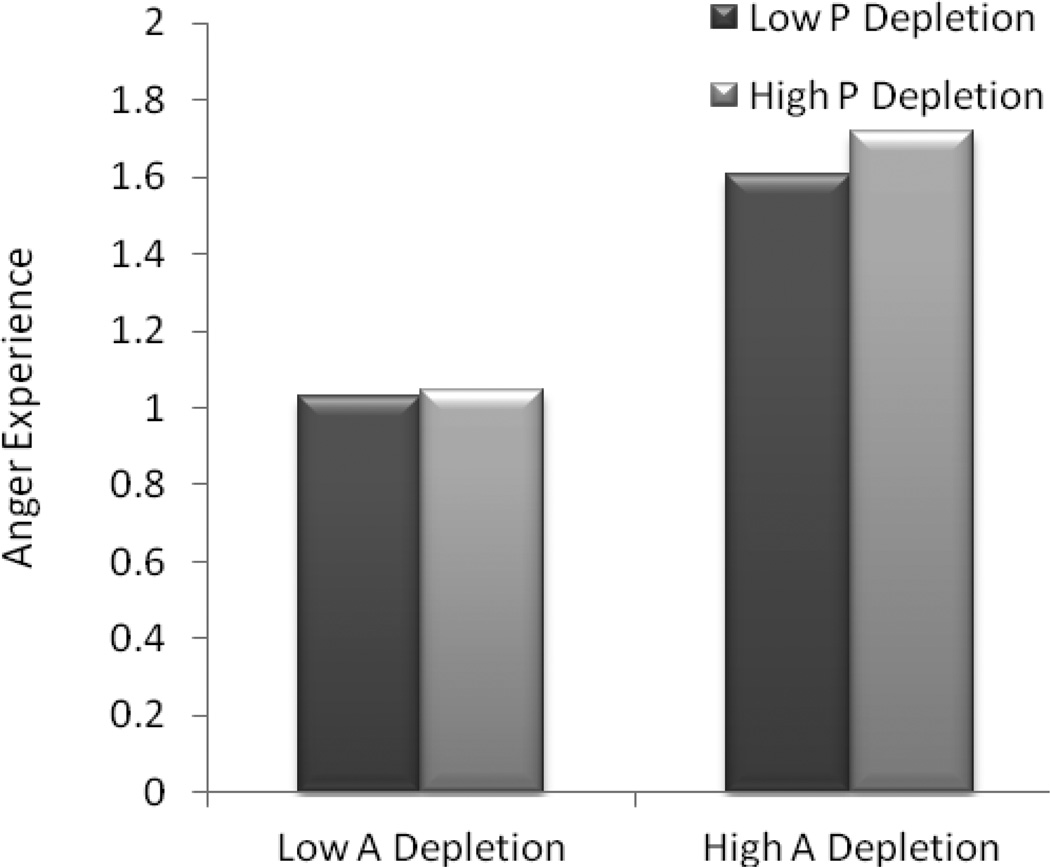

Cross-Partner Interaction

Examination of the actor depletion X partner depletion interaction resulted in findings that were consistent with reported arguing. Actor depletion was positively associated with actor-reported anger on high partner depletion days (b=.34, p<.01, 95% CI=.31-.36). This association was also significant, but weaker, on low partner depletion days (b=.29, p<.01, 95% CI=.26-.31). Similarly, partner depletion was associated with actor-reported anger on high actor depletion days (b=.06, p<.01, 95% CI=.03-.08). This association was not significant on low actor depletion days (b=.01, p=.48, 95% CI=−.01–.03).Together, these results indicate that male anger was more sensitive to partner depletion, whereas female anger behaved more independently of partner depletion. Across male and female participants, high actor depletion was consistently associated with greater partner-specific anger while partner depletion was only associated with anger on days of congruent, high actor depletion. The main and interactive effects of HED were not associated with anger for males or females.

Supplemental Analyses

Although not a primary aim of the current paper, we evaluated the main and interactive daily effects of anger on arguing. We found that higher levels of anger (b=0.32, p<.001, 95% CI=.31-.34) were associated with more arguing and that anger interacted with actor depletion (b=0.02, p<.001, 95% CI=.01-.03) such that the association between depletion and arguing was strongest on days of high, relative to low, anger. The interaction between anger and HED approached significance (b=0.06, p=.07, 95% CI=.01-.13) such that HED was associated with more arguing only on days of high anger.

Discussion

The present study is among the first to evaluate the interactive effects of daily instigatory and disinhibitory processes on negative relationship functioning across partners, within couples. Results offer support for the association between individual disinhibitory influences and negative relationship functioning at the daily level. Hypothesis 1a was supported in that participants reported more arguing and partner-specific anger on days of self-control depletion. Thus, preliminary analyses of the daily data provided by this study’s high-functioning, community sample were generally consistent with previous research on the effects of self-control depletion on relationship functioning during laboratory interactions (e.g., Finkel et al., 2009).

Expanding upon this literature and providing support for hypothesis 1b, a significant effect of partner self-control depletion was also found, indicating that participants reported more arguing and partner-specific anger on days during which partners reported high self-control depletion. These novel findings are consistent with the I3 model, under which partner depletion may be best conceptualized as an indirect proxy measure for instigation. That is, a depleted partner may display unstable or provocative behavior that may be more likely to trigger a normative urge to aggress. The use of independent depletion reports by both partners is a unique feature of the current study that allows for the examination of interdependent processes within couples. The detection of partner effects, outside of the actor’s direct perception, indicates that one partner may influence the other in possibly subtle and imperceptible ways. These findings are consistent with previous research that has detected unique actor and partner effects in the prediction of daily experiences within dyads (Gable, Reis, & Downey, 2003).

The consistency in associations between depletion and our conceptually distinct outcomes indicates that the depletion of self-control among actors and partners is associated with both anger experience and anger expression (i.e., arguing). The current results suggest that affective regulation, much like behavioral regulation, may indeed draw from and be subject to the depletion of limited self-control resources. Previous laboratory investigations, however, have found little support for a proximal association between the depletion of self-control and affective responding (see Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). The present findings may be best interpreted within the context of the previously described “ironic” effects (Berkowitz, 2012; Wegner et al., 1993), whereby the association between depletion and anger experience may be most easily observed over longer periods of time than those described under laboratory conditions. Further naturalistic research is required to determine the degree to which the depletion of self control may differentially influence the processes of affective and behavioral regulation.

Consistent with the I3 model of partner aggression (Finkel & Eckhardt, in press) and hypothesis 2, actor and partner depletion were shown to predict negative relationship functioning. A robust cross-partner interaction whereby partner depletion moderated actor depletion emerged across analyses. Specifically, this instigation X disinhibition interaction revealed that both male and female actors reported more arguing and anger with self-control depletion on days of high, relative to low, partner depletion. Similarly, partner depletion was only associated with arguing and anger on days of high actor depletion, suggesting that participants may have been able to avoid, accommodate, or otherwise cope with depleted partners while their own self-control resources remained intact.

There were gender differences in the association between depletion and both indicators of relationship functioning emerged. Females reported more arguing than males on days of actor-only depletion whereas males, in general, reported more arguing and anger than females on days of high partner depletion, regardless of their own level of depletion. These results suggest the possibility that low actor depletion may be a protective factor, reducing the perception of arguing despite partner depletion and possibly allowing for accommodative behaviors, among females but not males. Alternatively, it is possible that the behavior displayed by male and female partners following depletion may differ such that females demonstrate greater overt provocation than males and, thus, contribute to a greater likelihood of aggressive responding among actors. These gender-specific results were not expected and additional research, including replication, is needed to evaluate this interpretation of the observed gender differences.

HED, in addition to depletion and in support of hypothesis 1c, was also positively associated with daily arguing, consistent with prior daily diary studies showing that alcohol increases conflict and aggression (Testa & Derrick, in press). However, contrary to hypotheses, it failed to moderate the relationship between actor depletion and arguing. These data suggest that either self-control depletion or the behavioral disinhibition that accompanies heavy alcohol use is sufficient to increase arguing; the combination does not add uniquely to its prediction. Moreover, contrary to our hypothesis, HED was not associated with anger toward a partner. Alcohol’s effects on anger may occur only in the presence of provocation (e.g. Eckhardt, 2007), resulting instead in positive effects in other circumstances (e.g., Levitt & Cooper, 2010). The current investigation was intended to examine the possibility that the temporary state of self-control depletion may account for some of the individual variance in the relationship between episodes of intoxication and aversive interactions with a partner.

Limitations

The findings offer a unique perspective on the interaction of partners’ daily self-control strength in couple functioning, making use of reports of self-control strength from both male and female partners within couples. However, the study was not specifically designed to address these hypotheses. To properly test the predicted temporal relationship between episodes of HED and subsequent relationship functioning, we limited our analyses to within-day reports in which alcohol use occurred prior to the submission of the daily report or not at all. Thus, HED data tended to involve those reports submitted later in the day and it is conceivable that the observed associations between HED and relationship functioning may differ among participants who habitually submitted reports early in the day. Reports of relationship dysfunction were limited to two single item measures. While the anger item assessed each individual’s affective experience, the arguing item assessed the individual’s perception of an interactive experience and, thus, it should be noted when interpreting the current results that the severity rating for daily arguments may have been affected by the behavior of both actors and partners. Couple-level items may be most appropriate given the interactive processes involved in arguments but future designs may also evaluate the perception of one’s own conflictual or aggressive behaviors to determine if differences exist between perceived arguing and perceived culpability for arguing. The weak relationships between partner ratings of anger and arguing were not unexpected. The partner violence literature demonstrates generally poor agreement between partner reports (e.g., Armstrong, Wernke, Medina, &Schafer, 2002). Disagreement may result from differences in the perception of events, recall ability, or participant fatigue. Future research may increase partner reliability by establishing universal definitions of target behaviors, broadening the number of aggression items, or narrowing the assessment window. Methodological research may also offer further insight into temporal changes in partner agreement that may result from participant fatigue.

Further insight into the potential relationships among depletion, HED, and relationship functioning will require the implementation of methodological advances that allow for greater temporal specificity, such as ecological momentary assessment (EMA), with multiple reports throughout the day. In conjunction with experimental research, EMA may help clarify the directionality of the relationship between depletion and relationship functioning beyond the capabilities of the current investigation.

Clinical Implications and Conclusions

The current dyadic study is the first to emphasize the importance of both actor and partner factors in understanding the daily experiences of perceived relationship arguing and partner-specific anger. The current results collectively demonstrated that participants interacted with and felt more negatively toward intimate partners on days of heavy episodic drinking and high self-control depletion, particularly when actor depletion co-occurred with partner depletion. Male participants seemed to be particularly susceptible to the effects of partner depletion. The partner violence literature indicates that, compared to females, males are responsible for perpetrating a greater amount (roughly 62%) of physical IPV that results in injury, particularly among married samples (Archer, 2000; Archer, 2002). Although laboratory and longitudinal research has demonstrated that both verbal aggression and negative affect serve as antecedents to physical intimate partner violence (Eckhardt, 2007; Finkel & Eckhardt, in press; Schumacher & Leonard, 2005), further research is needed to expand the current findings into clinically relevant areas, such as intimate partner violence perpetration and intervention. The current results offer initial support for the inclusion of partner influences, in addition to conventional actor effects, in etiological and treatment models for relationship conflict and intimate partner violence. Indeed, partner violence treatment models that enlist the participation of both partners have demonstrated superior results over standard, offender-only treatments (for a review, see McCollum & Stith, 2008).

Figure 2.

Partner-specific anger experience as a function of gender and partner depletion of self-control. P = Partner

Figure 3.

Partner-specific anger experience as a function of actor and partner depletion of self-control. A=Actor, P=Partner.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants R01 AA016127 and T32-AA007583 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form.

As an example, a respondent reports on her current feelings of depletion on Sunday. On Monday, she reports whether she drank any alcohol on Sunday and if so, at what time. The time stamp for Sunday’s report can be used to determined whether Sunday’s drinking came before or after the report.

When included in the full models predicting daily arguing (b=0.03, p=.11, 95% CI=−.01–.06) and anger (b=.01, p=.55, 95% CI=−.03–.05), participation in the lab study failed to reach significance or change the direction of observed effects.

Removing all control variables from the models predicting anger and arguing resulted in attenuated effects but no notable changes to either significance or direction.

References

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in physically aggressive acts between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior: A Review Journal. 2002;7:313–351. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong T, Wernke JY, Medina KL, Schafer J. Do partners agree about the occurrence of intimate partner violence? A review of the current literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2002;3:181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF. Ego depletion and self-regulation failure: A resource model of self-control. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:281–284. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000060879.61384.A4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs K, Tice D. The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:351–355. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. A different view of anger: The Cognitive-Neoassociation conception of the relation of anger to aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 2012;38:322–333. doi: 10.1002/ab.21432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J, Quartana P, Bruehl S. Anger inhibition and pain: Conceptualizations, evidence and new directions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31:259–279. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen P, Cole J, Field M. Ego depletion increases ad-lib alcohol consumption: Investigating cognitive mediators and moderators. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmcology. 2012;20:118–128. doi: 10.1037/a0026623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall N, Finkel E, Denson T. Self-control inhibits aggression. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5:458–472. [Google Scholar]

- Digiuseppe R, Tafrate R. A comprehensive treatment model for anger disorders. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2001;38:262–271. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ. Intimate partner violence perpetration: Insights from the science of self-regulation. In: Forgas JP, Fitness J, editors. Social relationships: Cognitive, affective, and motivational processes. New York: Psychology Press; 2008. pp. 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel E, DeWall CN, Slotter E, Oaten M, Foshee V. Self-regulatory failure and intimate prtner vioelnce perpetration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:483–499. doi: 10.1037/a0015433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel E, Eckhardt CI. Intimate partner violence. In: Simpson JA, Campbell L, editors. The Oxford handbook of close relationships. New York: Oxford; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Gable S, Reis H, Downey G. He said, she said: A quasi-signal detection analysis of daily interactions between close relationship partners. Psychological Science. 2003;14:100–105. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.t01-1-01426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola P. Executive Functioning and alcohol-related aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:541–555. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagger M, Wood C, Stiff C, Chatzisarantis N. Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:495–525. doi: 10.1037/a0019486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE. Editorial: Alcohol and intimate partner violence: When can we say that heavy drinking is a contributing cause of violence? Addiction. 2005;100:422–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, Cooper ML. Daily alcohol use and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:1706–1722. doi: 10.1177/0146167210388420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollum E, Stith S. Couples treatment for interpersonal violence: A review of outcome research literature and current clinical practices. Violence & Victims. 2008;23:187–201. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Elkins SR, McNulty JK, Kivisto AJ, Handsel VA. Alcohol use and intimate partner violence perpetration among college students: Assessing the temporal association using electronic diary technology. Psychology of Violence. 2011;1:315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, Baumeister RF. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:247–259. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, Collins RL, Nienhaus K. Self-control and alcohol restraint: An initial application of the self-control strength model. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:113–120. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.16.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, Collins RL, Shiffman S, Paty J. Daily functions in self-control demands and alcohol intake. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:140–147. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The physicians’ guide to helping patients with alcohol problems. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, NIAAA; 1995. NIH publication no. 95-3769. [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Hsieh Y-P, Bradizza CM, Romosz AM. Factors influencing the temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and experiences with aggression among college women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:210–218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter P, Paterson J, Feehan M. Prevalence and concordance of interpersonal violence reports from intimate partners: Findings from the Pacific Islands Families Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2007;61:625–630. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.048538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher J, Leonard K. Husbands’ and wives’ marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggression as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:28–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Stucke T, Baumeister R. Ego depletion and aggressive behavior: Is the inhibition of aggression a limited resource? European Journal of Social Psychology. 2006;36:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Derrick JL. A daily process examination of the temporal association between alcohol and verbal and physical aggression in community couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0032988. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Does alcohol make a difference? Within participants comparison of incidents of partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:735–743. doi: 10.1177/0886260503253232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohs KD, Finkenauer C, Baumeister RF. The sum of friends’ and lovers’ self-control predicts relationship quality. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2011;2:138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner D, Erber R, Zanakos S. Ironic processes in the mental control of mood and mood-related thought. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:1093–1104. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.6.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]