Abstract

This research examined developmental trajectories for social and physical aggression for a sample followed from age 9–18, and investigated possible family predictors of following different trajectory groups. Participants were 158 girls and 138 boys, their teachers, and their parents (21% African American, 5.3% Asian, 51.6% Caucasian, and 21% Hispanic). Teachers rated children’s social and physical aggression yearly in grades 3–12. Participants’ parent (83% mothers) reported on family income, conflict strategies, and maternal authoritarian and permissive parenting styles. The results suggested that both social and physical aggression decline slightly from middle childhood through late adolescence. Using a dual trajectory model, group based mixture modeling revealed three trajectory groups for both social and physical aggression: low-, medium-, and high-desisting for social aggression, and stably-low, stably-medium, and high-desisting for physical aggression. Membership in higher trajectory groups was predicted by being from a single-parent family, and having a parent high on permissiveness. Being male was related to both elevated physical aggression trajectories and the medium-desisting social aggression trajectory. Negative interparental conflict strategies did not predict social or physical aggression trajectories when permissive parenting was included in the model. Permissive parenting in middle childhood predicted following higher social aggression trajectories across many years, which suggests that parents setting fewer limits on children’s behaviors may have lasting consequences for their peer relations. Future research should examine transactional relations between parenting styles and practices and aggression to understand the mechanisms that may contribute to changes in involvement in social and physical aggression across childhood and adolescence.

Children and adolescents who behave aggressively are at greater risk for psychological maladjustment, conduct problems, and incarceration (Dodge, Coie & Lynam, 2006; Huesmann, Dubow & Boxer, 2009). Children’s earliest aggression is generally physical, and begins in the second year of life (Tremblay, 2000; Tremblay et al., 1999). By the time children enter preschool, they have already begun to engage in socially aggressive behaviors (McNeilly-Choque, Hart, Robinson, Nelson & Olsen, 1996). Although most children engage in at least some aggressive behaviors during childhood (Tremblay et al., 2004), youth vary in the frequency and intensity of their social and physical aggression across development (Bergman & Andershed, 2009; Brame, Nagin & Tremblay, 2001; Broidy et al., 2003; Karriker-Jaffe, Foshee, Ennett & Suchindran, 2008). This research examines whether youth follow different developmental trajectories for social and physical aggression, and investigates possible predictors of membership in trajectory groups.

Whereas physical aggression includes behaviors intended to cause physical injury, such as hitting, slapping, and biting, social aggression refers to behaviors designed to cause harm to an individual’s social status or friendships (Dodge et al., 2006; Underwood, 2003). Social aggression includes behaviors such as social exclusion, manipulating friendships, and malicious gossip (Underwood, 2003). Several similar forms of aggression have been proposed, including indirect (Björkqvist, Lagerspetz & Kaukianen, 1992) and relational aggression (Crick, Casas & Mosher, 1997; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). Social aggression is distinct from these alternative forms of aggressive behavior because it includes both verbal and nonverbal forms of exclusion (unlike relational aggression) as well as acknowledges that socially aggressive behavior can manifest itself in both direct and indirect forms (unlike indirect aggression). This study examines social aggression because it includes a wider range of behaviors that children may engage in to harm their peers’ friendships and social standing than indirect or relational aggression (Archer & Coyne, 2005; Vitaro & Brendgen, 2012), which may be important as children grow older and become increasingly sophisticated.

The fact that socially and physically aggressive behaviors both occur by the time children enter preschool (McNeilly-Choque et al., 1996; Tremblay et al., 1999) suggests that family characteristics and features of parenting may be important predictors of children’s aggressive behavior. This research investigates whether children follow different developmental trajectories for social and physical aggression from middle childhood through late adolescence and whether authoritarian or permissive parenting styles and negative interparental conflict strategies increases the risk of youth following elevated aggression trajectories.

The Developmental Course of Social Aggression

Some have speculated that social aggression may become increasingly frequent as children enter late childhood and early adolescence (Archer & Coyne, 2005; Underwood, 2003), perhaps because children engage in more covert forms of aggression to avoid punishment (Dishion & Patterson, 2006). Also, as peer relationships become increasingly important, children and adolescents may focus on an individual’s relationships and social status as an effective target for causing the most harm (Buhrmester, 1996; Zimmer-Gembeck, Geiger & Crick, 2005). However, the majority of previous studies that have investigated trajectories of social aggression have been limited to early through late childhood. One longitudinal study examining indirect aggression from ages 4 – 8 found that although the majority of participants (67.9%) followed a stably low trajectory, 32.1% of children followed a steadily increasing trajectory (Coté, Vaillancourt, Barker, Nagin & Tremblay, 2007). More recently, a longitudinal study assessed children between 4 and 11 years old identified four indirect aggression trajectories. Participants on the non-aggressive and low aggression trajectories remained stable; the moderate- and high-trajectories of indirect aggression both followed developmental courses that increased until approximately age 7 and then remained generally stable through the final assessment wave when participants were 11 years old (although boys on the high trajectory remained slightly more stable across time than girls; Pagani, Japel, Vaillancourt & Tremblay, 2010). Both of these studies used parent-reports of aggression.

The few studies that have examined the developmental course of social aggression during middle-childhood through adolescence have found somewhat conflicting results. An examination of data from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD) found that from ages 8 – 11, relational aggression as rated by teachers and parents remained stable for girls but declined slightly for boys (Spieker at al., 2012). In a study of earlier waves of the same sample presented in this study, Underwood, Beron and Rosen, (2009) examined teacher-reports of social aggression and identified two trajectories: one stably low and the other decreasing steadily from age 9 through 13. In a study of self-reports of aggression from ages 10 – 15 the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth in Canada (NLSCYC), three developmental trajectories for indirect aggression emerged: low-declining, moderate-declining, and high (Cleverly, Szatmari, Vaillancourt, Boyle, & Lipman, 2012). In a study with rural middle and high-school students, self-report data indicated that both boys and girls followed a curvilinear trajectory that showed increases in socially aggressive behavior from ages 11 – 14 years old followed by a rapid decline through age 18 (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2008).

Developmental Course of Physical Aggression

During late childhood through early adolescence, most children engage in physical aggression infrequently, or do not engage in physical aggression at all (Broidy et al., 2003; Dodge et al., 2006; Huesmann et al., 2009). Despite this, some children continue to engage in moderate or high levels of aggression through late childhood and into adolescence (Brame et al., 2001; Dodge et al., 2006; Huesmann et al., 2009). Even for those children who do continue to engage in physical aggression during middle and late adolescence, the majority follow desisting trajectories (Brame et al., 2001; Nagin & Tremblay, 1999; Underwood et al., 2009). Boys are more likely to engage in physical aggression in childhood and adolescence (Archer, 2004; Card, Stucky, Sawalani & Little, 2008; Dodge et al., 2006) and are at greater risk of following elevated physical aggression trajectories than girls (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2008; Underwood et al., 2009).

Gender Differences in Aggression

Males engage in higher levels of physical aggression than females (Archer, 2004; Card et al., 2008; Dodge et al., 2006). However, gender differences in social aggression are far less clear. Although some have proposed that girls engage in social, indirect, and relational forms more than boys (Crick, et al., 1997; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995), recent evidence suggests gender differences may be small. A meta-analysis of 148 studies examining direct and indirect aggression found that although girls did engage in slightly higher rates of indirect aggression than boys, the magnitude of the difference was so small that it was considered trivial (Card et al., 2008). Another meta-analytic review of sex differences in aggression showed that greater use of indirect forms of aggression by females was small, inconsistent across studies, and related to the rater reporting on aggression (e.g. peer nominations versus teacher reports; Archer, 2004). A cross-national study of 1400 children in nine different countries also found no consistent gender differences for relational aggression (Lansford et al., 2012). Most of the previous longitudinal studies of social aggression have not found gender differences in social aggression. The one exception is the examination of the NICHD SECCYD data; girls were higher on relational aggression at all time points from grades 3 – 6, according to the highest item rating by the teacher or the mother (Spieker at al., 2012). In a longitudinal study examining trajectories of social and physical aggression, gender was not a significant predictor of membership in either the low-stable or desisting social aggression trajectories across 3rd through 7th grade (Underwood et al., 2009). In the National Longitudinal Study of Children and youth sample followed from ages 10 – 15, there were no gender differences in indirect aggression at any time point, though there were more girls than boys in the moderate indirect-aggression/low physical aggression group (Cleverly et al., 2012). Another longitudinal examination of the development of social aggression from ages 11 through 18 found that boys and girls followed identical trajectories of social aggression (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2008).

Family Predictors of Social and Physical Aggression

Demographic variables

African American children and children in divorced and low-income families are at greater risk of engaging in aggressive behavior during childhood and adolescence (Nagin & Tremblay, 2001; Putallaz et al., 2007; Tremblay et al., 2004; Vaillancourt, Miller, Fagbemi, Coté & Tremblay, 2007). African American children and children of other ethnic minorities are at greater risk of involvement in relational aggression (Putallaz et al., 2007) and physical aggression, particularly as they enter middle adolescence, however these findings may be confounded with socioeconomic status (see Dodge et al., 2006). Low family income predicts children’s involvement in physical aggression (see Dodge et al., 2006). However, several studies have found that income is not a significant predictor of social or indirect aggression (Spieker et al., 2012; Underwood et al., 2009; Vaillancourt et al., 2007).

Children with separated or divorced parents engage in elevated levels of physical (Tremblay et al., 2004) and social aggression (Kerig, Brown & Pantenaude, 2001). Parental divorce may be associated with more frequent interparental conflict, which may in turn model negative conflict strategies or harm the parent-child relationship. Children in single-parent homes characterized by high conflict and triangulation engage in higher levels of socially aggressive behavior (Kerig et al., 2001).

Parenting styles

Parenting styles relate to children’s involvement in both social and physical aggression (Coté et al., 2007; Kawataba, Alink, Tseng, van Ijzendoorn & Crick, 2011; Olsen, Lopez-Duran, Lunkenheimer, Chang & Sameroff, 2011; Sandstrom, 2007; Underwood et al., 2009). Authoritarian parenting, characterized by harsh and intrusive behaviors in conjunction with a lack of warmth and positivity, may put children at greater risk for involvement in aggressive behavior by modeling coercive and power-asserting techniques to children who may in turn view these behaviors as effective with peers (Ladd & Pettit, 2002). In a recent meta-analysis, negative and harsh maternal parenting behavior was correlated with relational aggression for both boys and girls, though effect sizes were uniformly small (Kawataba et al., 2011). Authoritarian parenting is also a predictor of overt and physical aggression, as are specific practices associated with this style (Kawabata et al., 2011). In the SECCYD study following children from ages 8 – 11, mother-child conflict in early childhood predicted higher relational aggression in grade 3 for both genders, and for girls only, observed maternal harsh control was a positive predictor of relational aggression, and observed maternal sensitivity was a negative predictor (Spieker et al., 2012).

The permissive parenting style, characterized by warmth with low or inconsistent demands placed on the child, is also associated with behavior problems and aggression. Permissive parenting predicted relational aggression in girls in a study with 4th grade children (Sandstrom, 2007). Furthermore, Kawataba et al’s. (2011) meta-analysis found that lax, uninvolved maternal parenting was correlated with relational aggression and this relation was not moderated by gender. Permissive parenting also predicts overt forms of aggression (Sandstrom, 2007). Permissive parenting may be negatively reinforced by aggressive behavior, as parents give up their attempts to control their children’s behavior to avoid aversive interactions with that child. This may in turn reinforce aggressive behavior as an effective form of peer interaction (Loeber & Dishion, 1984; Patterson, DeBaryshe & Ramsey, 1990). In an investigation of earlier waves of the same sample presented in this study in grades 3rd through 7th, maternal permissiveness predicted membership in the moderate-increasing joint trajectory group for social and physical aggression (Underwood et al., 2009).

Interparental conflict strategies

Another important predictor of children’s aggression is how parents behave in conflicts with their spouse. Children and adolescents who are exposed to frequent interparental conflict (IPC) are at greater risk of delinquency and aggression (Cummings, Goeke-Morey & Papp, 2004; Li, Putallaz & Su, 2011; Marcus, Lindahl & Malik, 2001; Underwood, Beron, Gentsch, Galperin & Risser, 2008). Social learning theory suggests that children are likely to imitate the conflict strategies they observe (Bandura, 1986; Grych & Fincham, 1990). One study found that children’s perceptions of the frequency and intensity of their parents’ conflicts were associated with higher levels of aggression with peers at school; this relation was mediated by the children’s cognitions about how appropriate aggressive responses were (Marcus et al., 2001). Given that negative conflict strategies may involve physical aggression or resemble socially aggressive behaviors (e.g. stonewalling, triangulation), it is not surprising that observing these behaviors in the home may predict engaging in aggressive behaviors towards peers (Kerig et al., 2001; Underwood et al., 2008).

The Current Research

This study extends earlier work on the predictors and development of social and physical aggression by examining aggression trajectories over 10 years, from middle childhood through late adolescence. Previous studies have examined the development of social/indirect/relational aggression longitudinally during childhood (Coté, et al., 2007; Pagani et al., 2010; Spieker et al., 2012; Vaillancourt et al., 2007). Only one previous study investigated the development of aggression from middle childhood through late adolescence (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2008): it examined individual aggression trajectories for boys and girls separately, and did not examine any predictors of membership in different trajectory groups. Although evidence suggests that demographic variables (Putallaz et al., 2007), parenting styles (Olsen et al., 2011) and interparental conflict (Kerig et al., 2001) all relate to aggression, no previous research has examined how these variables predict following divergent aggression trajectories from childhood through late adolescence.

Investigating aggressive behavior across this span of time is important in understanding the etiology of aggression and its relation to subsequent adjustment in adulthood. The trajectories of involvement in antisocial and aggressive behavior that youth follow (particularly during the transition across childhood through adolescence), may be a more important predictor of adjustment than engaging in these behaviors at any single time point (Moffitt, 1993). Examining how these established predictors of aggressive behavior relate to aggression trajectories during middle childhood through late adolescence will expand our understanding of how aggression develops during the decade prior to adulthood, a period of time in which youth’s divergent involvement in antisocial and aggressive behavior may be particularly important to future adjustment (Laub & Sampson, 2003; Moffitt, 1993). This research builds on a previous examination of this sample’s aggression trajectories during childhood through early adolescence (grades 3 through 7; Underwood et al., 2009), by investigating participants’ social and physical aggression in grades 3 through 12, and possible predictors of following identified trajectories.

Previous research on developmental trajectories of aggression has relied on self- (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2008) or parent-reports (Coté et al., 2007; Pagani et al., 2010; Vaillancourt et al., 2007). The use of teacher reports of aggression may have several advantages over self- and parent-reports. Children and adolescents may be unwilling to respond honestly about their own aggressive behavior for fear of punishment from authority figures. Furthermore, evidence suggests that distinct raters of children’s adjustment have unique knowledge of children’s involvement in these behaviors based on the situational context in which they interact with the youth (Achenbach, McConaughyy & Howell, 1987; Offord, Boyle & Racine, 1989; Youngstrom, Loeber & Stouthammer-Loeber, 2000). Given that teachers have greater opportunity to view children interacting with their peers, they may have a better opportunity to observe the primary context in which aggression is likely to happen than parents. Finally, given that participants were rated by a different teacher every year, any stability across time likely reflects actual stability in the children’s behaviors rather than stable characteristics of the raters themselves. Relying on teacher reports of aggression and parents’ reports of parenting styles and interparental conflict also allows us to avoid the problem of shared method variance, which has plagued most previous work on parenting predictors of relational aggression (Kawabata at al., 2011).

The first goal of this study was to examine whether children follow different developmental trajectories for social and physical aggression from ages 9 through 18. Because previous research suggests distinct correlates and outcomes related to social and physical aggression, we examined trajectories for social and physical aggression separately. However, to examine the extent to which youth following similar trajectories for each subtype, we also examined overlap in trajectory group memberships for social and physical aggression. Based on previous research, we predicted that at least two social aggression trajectories would emerge. We anticipated one trajectory of children who engage in little or no social aggression throughout the time period assessed, as well as one trajectory that exhibits initially high levels of social aggression, and then declines. Given that some studies examining indirect aggression during childhood have identified more than two trajectory groups (Pagani et al., 2010), it is possible that a moderate-desisting trajectory of social aggression would emerge.

Guided by previous evidence, we predicted three or four distinct physical aggression trajectories (Nagin & Tremblay, 1999; Underwood et al., 2009). We expected to identify one trajectory group of children who engage in little or no physical aggression throughout the entire assessment period and one trajectory group who exhibits stably-high levels of physical aggression through middle adolescence, and then declines. In addition, we predicted either one (a moderate desisting) or two (moderate-low desisting and moderate-high desisting) additional trajectory groups. Because this study followed participants through the end of high school when even those children on the highest physical aggression trajectories show decreases (Brame et al., 2001; Dodge et al., 2006; Underwood et al., 2009) we anticipated that by middle adolescence, all physical aggression trajectories would be declining.

The second goal of this study was to examine possible demographic and family variables that may predict membership in different trajectory groups for social and physical aggression. We predicted that males would be at greater risk of following elevated physical aggression trajectories (Card et al., 2008; Dodge, et al., 2006; Karriker-Jaffee et al., 2008), however we did not expect gender to be a significant predictor of membership in social aggression trajectory groups (Card et al., 2008; Karriker-Jaffee, 2008; Underwood et al., 2009). We predicted that non-White children would be more likely to be on elevated social and physical aggression trajectories (Dodge et al., 2006; Putallaz, et al., 2007) as would children with divorced parents (Kerig et al., 2001; Tremblay et al., 2004). We predicted that lower family incomes would predict elevated physical aggression trajectories (Tremblay et al., 2004), but would be unrelated to the development of social aggression (Spieker et al., 2012; Underwood et al., 2009; Vaillancourt et al., 2007). We anticipated that the overly harsh parenting behaviors associated with the authoritarian parent style as well as the excessively lax and lenient behaviors of the permissive parenting style would predict following higher trajectories for both social and physical aggression (Kawataba; 2011; Olsen et al., 2011; Sandstrom, 2007). Finally, we predicted that high levels of negative interparental conflict would also be associated with elevated social and physical aggression trajectories (Li et al., 2011; Underwood et al., 2008).

Method

Participants

Participants were 158 girls and 138 boys, their teachers, and their parents. Target children were initially recruited when they were approximately 9 years old and at the end of their 3rd grade year and were assessed yearly through age 18 at the end of 12th grade. Participants were recruited from a large, diverse public school district in the southern United States. The ethnically diverse sample was 21% African American, 5.3% Asian, 51.6% Caucasian, 21% Hispanic, 1.1% were of another race, mixed race, or did not disclose their ethnicity. Parents reported annual family income on a five-point scale: annual income of less than $25,000; $26,000 – $50,000; $51,000 – $75,000; $76,000 – $100,000; and an annual income greater than $100,000. Parents reported income during annual visits using the same scale. Participants who were in the lowest two income categories for at least 75% of the years they reported income were coded as low income1. Most participant children had married parents during the initial year of demographic data collection (65.8%), 3.6% had parents who were remarried, 12.1% had divorced parents, 6.4% had parents who were separated, 1% had widowed parents, 9.3% had parents who were never married, and 1.8% of parents chose not to report marital status information.

Children’s teachers in grades 3 through 12 were invited to participate in the study by providing ratings of participants’ social behaviors at school. Elementary school teachers, who taught the children in their classrooms all day, provided ratings in grades 3 – 6. Given that beginning in 7th grade participants’ language arts teachers taught the students for two class periods per day during the school week, these teachers provided ratings in grade 7 and grade 8. When the participants entered high school, participants nominated a “favorite” teacher or a “teacher who knew them best” to provide ratings. If participants indicated they did not have a “favorite” teacher, the language arts teacher provided ratings. Proportions of teachers who reported aggressive behavior varied across each school year (3rd grade - 66%; 4th grade – 73%; 5th grade – 76%; 6th grade – 74%; 7th grade – 65%; 8th grade – 78%; 9th grade – 52%; 10th grade – 61%; 11th grade - 51%; 12th grade – 49%).

The parent most knowledgeable about the child’s social activities also participated in the longitudinal study. The parent most knowledgeable for 83% of the sample was the mother and for 17% of the sample was the father. Other studies investigating childhood aggression used reports of the “person most knowledgeable about the child” (PMK, Coté el., 2007, p.4, 89.9% of PMK’s were mothers). We deliberately chose to include only one parent, the parent with whom the child might feel most comfortable discussing their social experiences during the observational portion of the study, which was an important component of the ongoing longitudinal investigation.

Procedures

Consent for the children’s participation was initially sought by distributing parental permission letters to the parents and the initial consent rate for the 10-year longitudinal study was 55%, which is commensurate with and even higher than many one-time, school-based studies (Sifers, Puddy, Warren, & Roberts, 2002). Participants’ teachers were contacted yearly in early spring by email or telephone and asked to complete a teacher rating measure assessing the target child’s peer relations and psychosocial adjustment. Teachers were initially offered $25 compensation per student packet completed. Teacher compensation was increased to $50 per student packet beginning in the 8th grade. Teacher packets were delivered and collected in person. This study includes teacher ratings from the Children’s Social Behavior Scale-Teacher form (CSBS-T, Crick 1996). During the summer between grades 3 and 4, a research assistant contacted parents to schedule an initial family visit which took place in the participants’ homes or the laboratory according the parents’ preferences. This study includes parent report data from the Family Life Inventory (a brief measure assessing demographic variables), the Couple Conflicts and Problem-Solving Scales (CPS-V; Kerig, 1996), and the Parenting Styles and Dimensions questionnaire (PSD; Robinson & Mandleco, 1995).

Measures

The couple conflicts and problem solving scales (CPS-V)

The CPS-V assesses dimensions of marital conflict that likely affect child development (Kerig, 1996). The current study focused on mother’s negative conflict strategies: verbal aggression, physical aggression, stonewalling, and triangulation. Parent’s responded to the CPS if they were married, they were divorced but often interacted with their former spouse in the presence of their children, they were remarried, or living with a significant other with whom they had disagreements in front of the child. Respondents reported on both their own conflict resolution strategies and that of their partner or spouse (responses to the prompt “What strategies have {you/your partner} used during disagreements with each other in the last year” ranged from Never (0) to Often (3)). The analyses presented below include maternal conflict resolution strategies. Thus, ratings of maternal conflict resolution strategies were self-report for most families given that the majority of participating parents were mothers. When the participating parent was the father, they rated the conflict resolution strategies of their partner (i.e., the father’s report of maternal conflict resolution strategies). We included data from families in which the father was the participating parent, so as to include as much information related to maternal conflict resolution strategies as possible. Of the families participating in the study, 206 mothers and 46 fathers completed the CPS.

The CPS has demonstrated reliability and validity. In the current study, the CPS’s verbal aggression, physical aggression, stonewalling, and triangulation subscales, all showed high reliability for mothers and fathers with alphas ranging from .72 to .96. In previous research, CPS scores were correlated with scores on the Conflicts Tactics Scales (Kerig, 1996), with children’s ratings of related dimensions on the Children’s Perceptions of Interparental Conflict measure, and related to children’s psychological adjustment. Previous research showed that for divorced parents, triangulation mediates the relation between post-divorce conflict and daughters’ relational aggression (Kerig et al., 2001). Mothers’ ratings of partners’ conflict strategies have been shown to be correlated with self-reports (Kerig, 1996; Marcus et al., 2001). To examine if fathers were accurate reporters of maternal conflict resolution strategies, correlation analyses were conducted for the small subgroup in this study for which both parents completed this measure (n = 31), fathers’ reports of mothers’ strategies and mothers’ self-reports were positively correlated (for stonewalling, r(29) = .64, p < .001 and for triangulation, r(29) = .72, p <. 001; see Underwood et al., 2008).

Parenting styles and dimensions (PSD)

The participating parent completed the Parenting Styles and Dimensions questionnaire (PSD; Robinson & Mandleco, 1995), a 50-item questionnaire designed to measure authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting (Baumrind, 1971). Parents rated both themselves and their spouses on a scale from Never (1) to Always (5) on how often they engage in particular parenting behaviors. Factor analyses demonstrated that items clustered onto three factors corresponding to Baumrind’s parenting styles (Robinson & Mandleco, 1995). Sample items from the PSD include “I guide our child more through punishment than by reasoning” (authoritarian) and “I let our child do anything he/she wants to do” (permissive parenting). In a study with low-income African American parents of preschool children, construct validity of the subscales relating to authoritative and authoritarian parenting was demonstrated by factor analyses (Coolahan, McWayne, Fantuzzo, & Grim, 2002). Concurrent validity of the two subscales was demonstrated by convergent and divergent associations with observations of parent-child relationships. Some dimensions of these subscales have been shown to relate to relational and physical aggression for preschool and school aged children (Hart, Nelson, Robinson, Olsen & McNeilly-Choque, 1998; Sandstrom, 2007).

For most families, mothers were the respondents on this measure; thus, ratings of parenting styles were self-report ratings. However, we included father’s ratings of mother’s authoritarian and permissive parenting for the few families in which the father was the respondent so as to include as much maternal parenting information as possible. Spousal agreement in ratings for authoritarian parenting styles is typically high with an r = .84 between parents’ reports of mothers’ authoritarian parenting and r = .75 between parents’ reports of fathers’ authoritarian parenting. Spousal agreement in ratings for permissive parenting is high with an r = .64 between parents’ reports of mothers’ permissiveness and r = .53 between parents’ reports of fathers’ permissiveness (Winsler, Madigan, & Aquilino, 2005). Given the significant correlations found in previous research between mothers’ self-reports and fathers’ reports of mothers’ parenting, we opted to include father’s ratings of the mother to allow for the largest sample possible.

Children’s social behavior scale-teacher form (CSBS-T)

Teachers rated participants’ social and physical aggression by completing a modified version of the CSBS-T (Crick, 1996), which is designed to assess relational aggression, physical aggression, and prosocial behavior. The CSBS-T was modified by adding social aggression items for gossip and nonverbal social exclusion to the relational aggression subscale. Four items assessed social aggression: “ignores people or stops talking to them when he/she is mad at them,” “gossips or spreads rumors about people to make other students not like them,” “gives others dirty looks, rolls his/her eyes, or uses other gestures to hurt others’ feelings, embarrass them, or make them feel left out,” and “tries to turn others against someone for revenge or exclusion.” Four items assessed physical aggression: ‘hits or pushes others,” “gets into physical fights with peers,” “threatens others,” and “tries to dominate or bully other students.” Teachers responded on a Likert scale ranging from 1 – “This is never true of this student” to 5 – “This is almost always true of this student”. The CSBS-T has been shown to have strong psychometric properties with a wide range of ages (Crick, 1996; Crick et al., 1997; Underwood, et al., 2009), and both the social and physical aggression subscales had strong inter-item reliability at every year of assessment (alphas ranging from .75 to .95).

Results

The analytic approach replicated and extended the earlier modeling of trajectories in Underwood, et al. (2009). First, we examined descriptive statistics and correlations for social and physical aggression. Second, we tested unconditional baseline growth models separately for social and physical aggression. These models provided an average social aggression trajectory and an average physical aggression trajectory around which individuals varied. Third, we constructed mixture (group-based) models that classified students separately into social and physical aggression trajectory classes (Nagin, 1999). We determined the polynomial degree and number of classes for each aggression variable using a combination of the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and likelihood ratio tests (LRT) (BIC; Nagin, 2005; LRT; Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Fourth, we estimated dual trajectory models where the social and physical trajectories were formed jointly rather than individually (Nagin, 2005). Last, we examined whether family factors predicted group membership in social and physical trajectory categories.

Growth and prediction models were estimated using a combination of Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) and Stata (StataCorp, 2011). In these analyses we considered the metric of the aggression variables; both physical and social aggression were assessed by teacher ratings that peaked at the lowest value (one) and were then skewed out to the maximum value (five). Following the recommendation of Nagin (2005), we analyzed the natural logarithm of the variables to account for the skewed nature of the data and used a censored normal (tobit) likelihood model to account for the concentration at the minimum value. In order to account for missing data in the construction of the trajectories, we used a maximum likelihood approach that allowed all observations to contribute to the estimated results (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). The only constraint was that participants were required to have a minimum of two out of the nine possible teacher reports of aggression.

To assess the fit of the trajectory models we used methods developed for mixture models. We assessed the reliability of the results of the models by computing the average posterior probability of assignment (AvePP) and the odds of correct classification (OCC; Nagin, 2005). These are both based on participants being assigned a probability of being in a class, j, through the estimation process, within the aggression type being estimated. The AvePP is a measure of the reliability of the model determined by averaging the actual (posterior) probability of being assigned to the class to which the student is eventually assigned. The OCC for class j is computed by:

In this formula, the numerator is the odds of correct assignment based on the average posterior probability and the denominator uses the estimated population proportion of class j, π̂j, and provides an estimate of what the odds are of a participant being classified in class j if they were randomly assigned. Thus, a higher OCC suggests better classification by the model compared to just randomly assigning students to a class. The guidelines developed by Nagin (1999, 2005) state that an AvePP of assignment of 0.70 or greater for each class is acceptable as well as having an OCC greater than five for each group.

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 1. The overall pattern of correlations showed significant, positive relations between different teachers’ ratings of participants’ social and physical aggression, even across many years. There were positive relations between both authoritarian and permissive parenting with both forms of aggression at many of the time points.

Table 1.

Correlations Between Measures of Social and Physical Aggression, Mothers’ Conflict Strategies, and Mothers’ Parenting by Gender

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social Aggression GR 3 | - | .75*** | .53*** | .41*** | .51*** | .40*** | .50*** | .37** | .23t | .07 | .16 | .05 | .33* | .38* | .37* | .35* | .38* | .40* | .35 | .05 | .32* | −.03 | .04 | 2.24 | 1.01 |

| 2. Physical Aggression GR 3 | .74*** | - | .55*** | .59*** | .28* | .25* | .44*** | .48*** | .09 | .05 | .15 | .27* | .49** | .70*** | .13 | .15 | −.05 | .04 | .11 | −.10 | .20 | .06 | −.14 | 1.40 | 0.68 |

| 3. Social Aggression GR 4 | .33* | .27* | - | .69*** | .38*** | .36*** | .43*** | .34** | .22t | −.02 | .27* | .19t | .15 | .26t | .35* | .28* | .35* | .41** | .18 | .00 | .04 | .21t | −.01 | 2.20 | 1.05 |

| 4. Physical Aggression GR 4 | .47*** | .57*** | .69*** | - | .28* | .56*** | .37** | .41*** | .11 | −.04 | .31* | .30* | .31* | .41** | .38** | .24t | .28t | .48** | .15 | −.02 | .01 | .21* | −.08 | 1.38 | 0.75 |

| 5. Social Aggression GR 5 | .28* | .24t | .34** | .31* | - | .54*** | .53*** | .34** | .41*** | .21t | .24* | .14 | .30* | .33* | .32* | .31* | .40** | .54*** | .33* | .04 | .13 | .10 | .17t | 1.87 | 0.80 |

| 6. Physical Aggression GR 5 | .57*** | .65*** | .30* | .44*** | .70*** | - | .45*** | .59*** | .34** | .30* | .31** | .30* | .33* | .48*** | .30* | .36** | .29* | .68*** | .07 | −.02 | .07 | .15 | .10 | 1.24 | 0.66 |

| 7. Social Aggression GR 6 | .12 | .14 | .29* | .40*** | .55*** | .61*** | - | .67*** | .42*** | .23* | .31** | .34** | .58***.58*** | .20 | .16 | .21 | .25t | .29* | −.04 | .04 | .08 | −.05 | 1.92 | 0.88 | |

| 8. Physical Aggression GR 6 | .39** | .49*** | .34** | .64*** | .52*** | .77*** | .75*** | - | .45*** | .53*** | .41*** | .55*** | .42*** | .70*** | .01 | .04 | .01 | .24t | .29* | .10 | −.02 | .03 | −.05 | 1.27 | 0.63 |

| 9. Social Aggression GR 7 | .06 | .33* | .22t | .36** | .23* | .42*** | .27* | .38*** | - | .63*** | .42*** | .32** | .40** | .36** | .25* | .24t | .29* | .29* | .43** | .18 | .20t | .18t | .17 | 1.84 | 0.73 |

| 10. Physical Aggression GR 7 | .30* | .41** | .32* | .46*** | .24* | .50*** | .26* | .50*** | .68*** | - | .32** | .51*** | .15 | .32* | .10 | −.05 | .01 | .15 | .49*** | .72*** | .14 | .12 | −.02 | 1.23 | 0.61 |

| 11. Social Aggression GR 8 | .26t | .32* | .26* | .35** | .18 | .40*** | .24* | .35** | .20t | .28* | - | .72*** | .32* | .40** | .27* | .21t | .31* | .35* | .05 | .02 | .20* | .20t | .24* | 1.83 | 0.80 |

| 12. Physical Aggression GR 8 | .30* | .32* | .26* | .34** | .20t | .51*** | .32** | .47*** | .24* | .49*** | .68*** | - | .36** | .60*** | .20t | .07 | .09 | .23t | −.02 | −.04 | .07 | .23* | −.01 | 1.32 | 0.68 |

| 13. Social Aggression GR 9 | .45** | .48** | .23t | .40** | .50*** | .65*** | .36** | .55*** | .03 | .13 | .44*** | .34** | - | .71*** | .20 | .20 | .18 | .28* | .21 | −.15 | .05 | −.01 | −.11 | 1.62 | 0.74 |

| 14. Physical Aggression GR 9 | .40* | .58*** | .29* | .42** | .39** | .57*** | .43*** | .56*** | .16 | .27* | .30* | .28* | .74*** | - | .08 | .24t | .03 | .14 | .27t | −.06 | .01 | .14 | −.08 | 1.18 | 0.41 |

| 15. Social Aggression GR 10 | .13 | .16 | .11 | .03 | .16 | .26* | .25* | .21t | .10 | .18 | .25* | .32** | .28* | .34** | - | .68*** | .52*** | .50*** | .16 | .10 | −.16 | −.15 | .09 | 1.64 | 0.89 |

| 16. Physical Aggression GR 10 | .17 | .32* | .03 | .14 | .20 | .39** | .19 | .27* | .15 | .22t | .15 | .17 | .34** | .48*** | .68*** | - | .59*** | .65*** | .05 | −.03 | −.10 | −.12 | .09 | 1.14 | 0.43 |

| 17. Social Aggression GR 11 | .32* | .38* | .08 | .33* | .25t | .48*** | .38** | .44*** | .36* | .29* | .32* | .28* | .56*** | .58*** | .37** | .56*** | - | .79*** | .21 | .04 | −.07 | −.24t | .24t | 1.74 | 0.84 |

| 18. Physical Aggression GR 11 | .39* | .42* | .18 | .39** | .12 | .47*** | .36** | .45*** | .39** | .51*** | .44*** | .48*** | .46** | .64*** | .38** | .57*** | .78*** | - | .07 | −.09 | −.14 | −.23t | .12 | 1.29 | 0.66 |

| 19. Social Aggression GR 12 | .04 | .00 | −.03 | .10 | .09 | .12 | .36* | .27* | .24t | .19 | .34* | .37** | .12 | .16 | .29* | .30* | .51*** | .43** | - | .55*** | .16 | .13 | −.03 | 1.48 | 0.56 |

| 20. Physical Aggression GR 12 | .25 | .36* | −.02 | .23 | .08 | .29* | .28** | .43** | .30* | .43** | .19 | .26t | .20 | .40** | .23t | .44*** | .63*** | .63*** | .63*** | - | .19 | .27t | −.03 | 1.13 | 0.40 |

| 21. Conflict Strategies | .10 | .03 | −.07 | −.05 | .13 | .13 | −.05 | .11 | .19 | .27* | .09 | .30* | .09 | .08 | .07 | .21t | −.06 | .04 | .04 | .07 | - | .45*** | .31*** | 0.90 | 0.37 |

| 22. Permissive Parenting | .16 | .20t | .12 | .15 | .29* | .33** | .21* | .27* | .14 | .21t | .24* | .20t | .40** | .30* | .11 | .22t | −.04 | −.07 | .16 | .05 | .45*** | - | .29*** | 1.83 | 0.37 |

| 23. Authoritarian Parenting | .11 | .23t | .08 | .16 | .09 | .26* | .19t | .32** | .32** | .44*** | .06 | .31** | .20t | .13 | .02 | .07 | .17 | .23t | .15 | .20 | .31*** | .29*** | - | 2.00 | 0.39 |

| Mean | 1.85 | 1.63 | 2.04 | 1.78 | 1.88 | 1.72 | 1.88 | 1.55 | 1.79 | 1.54 | 1.78 | 1.48 | 1.76 | 1.47 | 1.61 | 1.29 | 1.62 | 1.30 | 1.40 | 1.14 | 0.96 | 1.87 | 1.96 | ||

| SD | 0.77 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 1.09 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.43 |

Note. Results for girls are above the diagonal. Results for boys are below the diagonal. Values in bold indicate significant gender differences. N =192

p< .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .10.

Growth models

We began by constructing multilevel (hierarchical) linear models for social and physical aggression across grades three through twelve. Although we built both linear and quadratic versions of these models, in anticipation of the mixture models below we illustrate the linear versions of each. Let yit be either the social or physical aggression variable for the ith child in the tth grade and G be the grade level (3 – 12). Then the initial growth model, shown as a mixed linear model, was

| (1) |

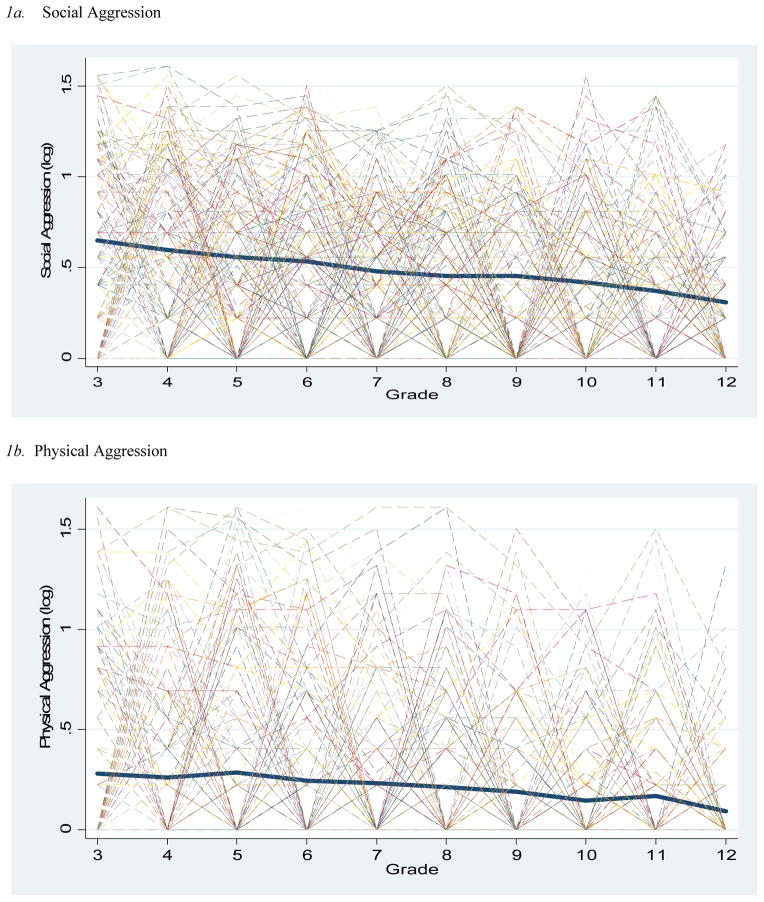

where the βs are the parameters for the intercept and growth variables, the rs are the random errors on these parameters, and ε is the (residual) error term for the equation. We plot both the actual observations for each student and the estimated regression line from the multilevel model in Figures 1a (social aggression) and 1b (physical aggression). The average behavior captured by the model, though significant (β00, β10 < .05), does not capture the heterogeneity of the individual behavior very well.

Figure 1.

Observed Aggression Trajectories and Estimated Regression Lines.

Mixture models

An alternative way to capture the heterogeneity is through a group-based analysis. Following Nagin (1999) we estimated unconditional linear and quadratic trajectories for classes of one through four separately for each aggression variable for grades three through twelve. Thus we allowed the data, through the estimation process, to group students into different trajectories. We compared the mixture models with different numbers of classes and polynomial degrees primarily using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) that sought the lowest BIC (Nagin, 2005). This led to both social and physical aggression best being represented by linear, three-class models, as shown in Table 2. As a check, we constructed a likelihood ratio test of four classes versus three with results that supported the three-class conclusion (p > .10; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). As discussed above, to assess the fit of these three-class models we calculated the AvePP and OCC for each model. In each case the guidelines of AvePP greater than 0.70 and OCC greater than five was met.

Table 2.

Bayesian Information Criteria by Number of Classes and Polynomial Degree

| Number of Classes | Polynomial Degree | BIC |

|---|---|---|

|

Social Aggression

|

||

| 1 | Linear | 3053 |

| Quadratic | 3058 | |

| 2 | Linear | 2868 |

| Quadratic | 2879 | |

| 3 | Linear | 2844 |

| Quadratic | 2860 | |

| 4 | Linear | 2852 |

| Quadratic | 2874 | |

|

Physical Aggression

|

||

| 1 | Linear | 2963 |

| Quadratic | 2967 | |

| 2 | Linear | 2719 |

| Quadratic | 2727 | |

| 3 | Linear | 2677 |

| Quadratic | 2686 | |

| 4 | Linear | 2680 |

| Quadratic | 2698 | |

Based on the individual trajectory analysis we estimated dual trajectory models that allowed for the contemporaneous development of the social and physical trajectories. These parallel process models, where the two processes are the social and physical developmental trajectories, allowed for the groups within each process to be probabilistically connected. Figures 2a and 2b illustrate the estimated trajectories from the dual trajectory model against the observed trajectories for social and physical aggression, respectively.

Figure 2.

Estimated Trajectories

The relation between the two processes in the dual trajectory model was derived from the joint probability of being in any of the three social groups along with any of the three physical groups, and this was an important output of the dual model. From these joint probabilities we calculated the conditional probabilities of being in any one specific trajectory within a process conditional on being in a specified trajectory of the other process. These probabilities are shown in Table 3. The results showed a strong connection between the social and physical trajectories. Being in the low or medium social trajectory was linked almost completely with being in the low or medium physical trajectory, respectively. There was a little more heterogeneity in the high social trajectory class where membership related with both the medium and high physical trajectories, but even here it was a very close connection between the high trajectories of each. The strong connection between the various classes was demonstrated by the very similar population projections of class membership (social low trajectory class, 37%; medium, 45.8%; high, 17.2%; physical low trajectory class, 35.6%; medium, 45.8%; high, 18.6%).

Table 3.

Joint and Conditional Probabilities of Social and Physical Aggression

| Physical Aggression | Social Aggression

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | |

| Probabilities of Joint Trajectory Group Membership | |||

|

| |||

| Low | .356 | .000 | .000 |

| Medium | .014 | .432 | .013 |

| High | .000 | .026 | .160 |

|

| |||

| Probability of Social Aggression Conditional on Physical Aggression | |||

|

| |||

| Low | 1.000 | .000 | .000 |

| Medium | .030 | .943 | .027 |

| High | .000 | .141 | .859 |

|

| |||

| Probability of Physical Aggression Conditional on Social Aggression | |||

|

| |||

| Low | .963 | .000 | .000 |

| Medium | .037 | .943 | .073 |

| High | .000 | .057 | .927 |

Predictors of trajectories

The estimated dual trajectory mixture model allowed each student to be assigned to one of the three classes in each aggression class. We next examined whether family variables predicted the trajectories participants followed. A series of multinomial logits were estimated that added blocks of variables sequentially. The first block included being female and White. The second block included having married parents and being low income category. The third block included interparental conflict strategies, maternal authoritarian parenting, and maternal permissive parenting, each measured at grade three or grade four if grade three was not available. The results are reported in Tables 4 (social aggression) and 5 (physical aggression).

Table 4.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis for Predicting Social Aggression Trajectory Classes as Measured by Teacher Ratings

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | Female | 0.435** | 0.433** | 0.440** | 0.491* | 0.471* |

| White | 0.435** | 0.752 | 0.640 | 0.547 | ||

| Low Income | 2.506* | 2.820* | 2.803 | |||

| Married | 0.302** | 0.332* | 0.324* | |||

| Conflict Strategies | 2.758* | 1.711 | ||||

| Maternal Permissive Parenting | 1.394 | |||||

| Maternal Authoritarian Parenting | 1.834 | |||||

|

|

||||||

| High | Female | 0.588 | 0.584 | 0.424* | 0.415 | 0.432 |

| White | 0.308** | 0.484 | 0.514 | 0.438 | ||

| Low Income | 2.369 | 2.561 | 2.059 | |||

| Married | 0.137** | 0.135** | 0.137** | |||

| Conflict Strategies | 4.260* | 1.062 | ||||

| Maternal Permissive Parenting | 4.538* | |||||

| Maternal Authoritarian Parenting | 2.332 | |||||

|

|

||||||

| N | 297 | 297 | 247 | 200 | 195 | |

p<0.05;

p<0.01

Relative risk ratios (odds ratios) shown compared to low trajectory

The estimates in Tables 4 and 5 are the exponentiated coefficients from the multinomial logits and represent the relative-risk ratios of being in the medium or high trajectory compared to the baseline low trajectory and can be interpreted in the same way as odds ratios2. A ratio equal to one means the independent variable has no predictive relation to the dependent variable. A ratio above one indicates that the independent variable positively predicts the likelihood of the event whereas a ratio below one indicates that the independent variable negatively predicts the likelihood of the event. So, for example, in Table 5 for physical aggression, the relative-risk ratio of being female in the first column is estimated to be 0.419. Using the roughly comparable idea of an odds ratio, this means that the odds of being in the highest physical trajectory class relative to the lowest are decreased by a factor of about .42 for females (compared to males), or, equivalently, the odds are decreased by 58 percent for females.

Table 5.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis for Predicting Physical Aggression Trajectory Classes as Measured by Teacher Ratings

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | Female | 0.419** | 0.414** | 0.422** | 0.451* | 0.439* |

| White | 0.471** | 0.853 | 0.696 | 0.604 | ||

| Low Income | 2.508* | 2.770* | 2.766 | |||

| Married | 0.322** | 0.352 | 0.353 | |||

| Conflict Strategies | 2.718 | 1.709 | ||||

| Maternal Permissive Parenting | 1.512 | |||||

| Maternal Authoritarian Parenting | 1.494 | |||||

|

|

||||||

| High | Female | 0.380** | 0.373** | 0.254** | 0.260** | 0.259** |

| White | 0.290** | 0.469 | 0.618 | 0.547 | ||

| Low Income | 2.234 | 2.756 | 2.408 | |||

| Married | 0.138** | 0.142** | 0.144** | |||

| Conflict Strategies | 6.286** | 2.022 | ||||

| Maternal Permissive Parenting | 3.092 | |||||

| Maternal Authoritarian Parenting | 2.217 | |||||

|

|

||||||

| N | 297 | 297 | 247 | 200 | 195 | |

p<0.05;

p<0.01

Relative risk ratios (odds ratios) shown compared to low trajectory

The results of the multinomial logits for social aggression in Table 4 showed that being female lowered the relative risk of being in the medium trajectory class, relative to the low class, in all specifications. In only one specification, where the gender, income, and married variables were included, did female reduce the odds of being in the high class. The effect of being White reduced the relative risk of being in the medium or high trajectory classes when only the female binary was included, but faded in significance as additional regressors were included. In contrast, having married parents reduced the odds of being in either the high or medium social aggression trajectories relative to the lowest trajectory in every specification. Being in the lowest two income categories for at least 75 percent of the time in the sample led to an increase in the likelihood of being in the medium trajectory relative to the lowest except when permissiveness and authoritarian parenting were included, at which point it became non-significant. Increases in negative parental conflict strategies increased the odds of being in both the medium and high trajectory classes until mother’s authoritarian and permissive parenting variables were added in, at which point they became non-significant. In the full model (column 5) mothers’ permissiveness had a significant effect leading to higher odds of being in the high trajectory class

The results of the physical multinomial logits for physical aggression in Table 5 showed that being female in all cases significantly reduced the odds of being in the high or medium trajectory relative to the lowest trajectory. The effect of being White reduced the likelihood of being in the medium or high trajectory classes when only the female binary was included, but was non-significant as additional regressors were included. The effect of being in the lowest income categories led to an increase in the odds of being in the medium trajectory except when permissiveness and authoritarianess were included, at which point it became non-significant. Having married parents reduced the odds of being in the high trajectory compared to the low throughout. Married parents were found to reduce the likelihood of being in the medium trajectory only when the model excluded conflict strategies, permissiveness, and authoritarian parenting; otherwise it was non-significant. The conflict strategies variable increased the relative risk of being in the high compared to the low categories until permissiveness and authoritarian parenting were added, at which point it became non-significant. Permissiveness and authoritarian parenting were never significant in the physical trajectory estimations.

Discussion

These results supported the hypothesis that youth follow distinct developmental trajectories of social and physical aggression during middle childhood through late adolescence. For both social and physical aggression, three trajectories were identified. Social aggression followed low-, medium-, and high-desisting trajectories, whereas physical aggression followed a stably non-involved, stably-low, and high-desisting trajectory. Following a medium or high trajectory for social aggression was strongly related to following the corresponding physical aggression trajectory (and vice versa). Membership in both the medium social and physical aggression trajectory groups was predicted by being male. Coming from a single-parent home predicted membership in the medium social aggression trajectory. Following high trajectories of both social and physical aggression was predicted by coming from a single-parent household, however being male was predictive of membership on the high physical aggression trajectory, whereas permissive parenting was a predictor of following the high social aggression trajectory.

Three linear social aggression trajectories were identified. Most participants followed either a middle-desisting or low-desisting trajectory; though a sizable number (17.2%) followed a high-desisting trajectory. Previous examinations of the developmental course of indirect/social aggression have often found two (e.g. Coté et al., 2007) or four separate pathways (e.g. Pagani et al., 2010). Indeed a previous study of this same sample followed from 3rd through 7th grade only identified two social aggression trajectories (Underwood et al., 2009). In this previous examination of this sample, the lowest trajectory followed a generally stable path, however with the additional five years, this trajectory displays a slight linear decline. The elevated trajectory presented here also appears to extend the trajectory identified previously (Underwood et al., 2009), exhibiting a linear decline across all observed grades. In contrast to the previous findings with this sample, an additional medium-desisting social aggression trajectory emerged in these analyses. With an additional five years of assessment, perhaps more nuanced distinctions in adolescents’ involvement with socially aggressive behavior could be identified, allowing this third trajectory to emerge. It is also worth noting that all three social aggression trajectories were characterized by linear declines from age nine (the first year of assessment) through 18 years of age. Although some evidence relying on self-reports has suggested that social aggression peaks during early or middle adolescence (Karriker-Jaffe, et al., 2008), these findings suggest that the highest levels of involvement may occur during middle childhood. It is possible that the steady declines in aggression may reflect teachers’ awareness of aggressive behavior as youth become more sophisticated in their aggressive behaviors, or see teachers less often throughout the day (in contrast to the curvilinear development identified when aggression was self-reported; Karriker-Jaffe, et al., 2008). Across the three aggression trajectories, the notable difference was one of initial level, not of decline in involvement. Given that all three trajectories show similar linear decreases in social aggression, this suggests the possibility that early intervention perhaps might expedite the eventual desistance among the most socially aggressive youth.

Three developmental trajectories of physical aggression were also identified. The majority of children followed either a stably low physical aggression trajectory or did not engage in any physical aggression throughout 3rd through 12th grades. A subset of youth (18.6%) followed a higher but declining trajectory for physical aggression over ten years. These three trajectories are similar to those identified in previous longitudinal studies examining the transition from childhood through adolescence (e.g. Nagin & Tremblay, 1999), suggesting that although the majority of children engage in little or no physical aggression by the time the enter elementary school, a minority of physically aggressive youth continue to show aggressive behavior during elementary school years, but show steady declines through adolescence and into adulthood (Tremblay et al., 1999).

Following the low, middle, or high trajectory for one form of aggression was highly associated with following the corresponding trajectory of the other form of aggression. This is consistent with findings from variable based studies that show a .7 correlation between indirect and direct aggression in a large meta-analysis (Card et al., 2008). Although our results and the correlational findings suggest that these two distinct types of aggressive behavior tend to occur together, the overlap is not perfect and only about half of the variance in one form of aggression is explained by the other. The differences between social and physical aggression trajectories provide evidence that examining these two types of aggression separately is warranted. For example, although youth following the lowest social aggression trajectory have a .96 probability of also following the lowest physical aggression trajectory, this manifests as essentially no involvement in physical aggression, while still engaging in low levels of social aggression throughout childhood and adolescence. Thus although the three social and three physical aggression trajectories show a great deal of overlap, they result in different levels of involvement in each type of behavior. Therefore, examining these two forms of aggression as one homogeneous phenomenon may fail to adequately capture the unique developmental course of involvement in these behaviors.

Furthermore, a large body of research suggests that distinct types of aggression may uniquely relate to psychological maladjustment (Mathieson & Crick, 2010; Ojanen, Findley & Fuller, 2012; Preddy & Fite, 2012). Therefore, examining the predictors that are unique to the developmental course of social or physical aggression may guide our understanding of social, psychological, and relational adjustment outcomes that may be unique to one form of aggressive behavior. In addition, this separate examination of the predictors of social and physical aggression may prove relevant to the development of intervention programs that are more finely tuned towards specific aggression typologies, as called for by practitioners and school administrators (Leff, 2007). Accordingly, examining the development of social and physical aggression separately may provide a more complete understanding of how aggression unfolds across developmental time, despite the substantial correlation between the two constructs.

In future research, it will be important to examine how social and physical aggression unfold together in real time. Clearly some youth engage only in social aggression, perhaps because disciplinary sanctions and other negative consequences are far less likely. For those youth who do engage in both forms of aggression, how does this process begin? Is it that social aggression precedes physical aggression, and those who are less well-regulated extend their aggression to the physical domain when provoked? Could it be that physically aggressive children are socially rejected, then lash back by maligning and excluding others? Understanding how social and physical aggression unfold separately and together in real as well as developmental time could guide the development of more effective intervention programs.

Several demographic and family variables were significant predictors of following elevated social and physical aggression trajectories. Although males were at greater risk for following medium social and physical aggression trajectories as well as the highest physical aggression trajectory, gender was not related to children’s involvement in the highest social aggression trajectory. Non-white children were not at greater risk of following elevated aggression trajectories when all variables were included in the model, providing some support that ethnic differences in aggressive behavior are largely confounded with other demographic variables (see Dodge et al., 2006).

Coming from families reporting stably low income predicted following both of the medium-aggression trajectories; however it became non-significant when the parenting strategies were included in the model. In contrast, membership on the high-desisting social and physical aggression trajectories was predicted by coming from a single-parent household. This distinction is difficult to disentangle. Taken together, these findings suggest that family disorganization and dysfunction associated with both low-income and single-parent status predicts greater involvement in aggressive behavior during childhood and adolescence (Dishion & Patterson, 2006; Tremblay et al., 2004). However, income become a non-significant predictor of the medium trajectories when parenting variables were included in the model and coming from a single-parent household only predicted following the highest aggression trajectories, suggesting that parenting features may be more relevant to involvement in aggression than income. Perhaps the challenges associated with being a single parent may reduce parents’ abilities to monitor their children’s behavior, which may in turn predict greater involvement with aggressive behavior (Dodge, Greenberg, Malone & Conduct Problems Prevention Group, 2008).

Although engaging in negative interparental conflict strategies predicted membership in both social aggression trajectories and the high physical aggression trajectory, it became non-significant when parenting variables were included in the model. This provides some evidence for the notion that interparental conflict may affect children’s development by interfering with the parent-child relationship (Li et al., 2011). The permissive parenting style was the only parenting variable that predicted aggression in the final model, and it only predicted membership in the high-desisting social aggression trajectory. Children with permissive parents may not receive much guidance or correction when they engage in socially aggressive behavior, and this early lack of intervention may predict following a higher but still desisting trajectory for aggression through the end of high school. It is also possible that, amidst the warm context that characterizes permissiveness, children who are prone to aggressive behavior may learn to express their aggression in less overtly hostile ways. It is also important to note that parental permissiveness was not related to the middle-desisting social aggression or any of the physical aggression trajectories.

It is remarkable that parents’ reports of high levels of warmth with low levels of limits or supervision predicted following a higher trajectory for social aggression across such long period of time. Although permissive parenting during middle childhood may be a causal factor in children’s subsequent social aggression, the possibility remains that children’s aggressive and defiant behaviors prior to the 3rd grade may be eliciting permissive parenting strategies, which may in turn predict elevated aggressive behavior. Furthermore, the model did not examine of the stability of permissive parenting strategies across the duration of this study, so it is not clear that early permissive parenting strategies are a unique predictor of aggressive behavior across the duration of childhood and adolescence.

Authoritarian parenting styles did not predict following any elevated social or physical aggression trajectories. Although a substantial body of research suggests that overly harsh and controlling parenting behaviors predict greater involvement in both social (Kawataba et al., 2011) and physical aggression (Olsen et al., 2011), these results did not provide support for this relation. It is possible that parents may change their reliance on authoritarian parenting strategies during middle childhood through late adolescence. If this were the case, this variability in utilizing these harsh parenting strategies may be the reason authoritarian parenting as rated in the 3rd grade did not predict involvement in social or physical aggression through 12th grade. This however is an empirical question and warrants further investigation.

The results of this study must be interpreted in light of methodological limitations. Although data imputation techniques permitted inclusion of participants without aggression ratings at every time point, the sample did decrease in size as additional predictor variables were included. As a result, the final models with all parenting variables included had reduced from an initial sample size of 297 down to 195 participants. This reduction in sample may have limited the ability to detect weaker effects of predictor variables. In particular, this decrease in sample size may have interfered with the predictive power of family income because lower income families may have had less stable residences and thus less likely to remain in the longitudinal study for such a long period of time. It is also worth noting that marital status and parenting variables were assessed when participants were in the 3rd or 4th grade. It is quite possible that marital status, as well as parent behaviors such as conflict strategies and parenting styles may change a great deal over these years. Nonetheless, the fact that marital status and permissive parenting strategies assessed at this early time point were significantly related to the developmental course of aggressive behavior during the ensuing ten years suggests that these variables may indeed be important predictors. Another limitation is that the overall declines seen in aggression across development may have been due to children becoming more adept at engaging in these behaviors surreptitiously, in ways that escape the notice of teachers. Although the inclusion of peer-reports of aggression may have been better able to capture these behaviors as they become increasingly sophisticated, school district restrictions did not permit collecting this data. Likewise, although evidence suggests features of the home environment predict involvement in aggression (Kawataba et al., 2011), this study did not include any features of peer relationships as predictors, which likely also contribute to involvement in aggressive behavior. Last, our study did not include other dimensions of parenting that may be relevant for social aggression. As one example, parental psychological control has been found to relate to children’s relational aggression across 23 studies, though these relationships were small (on average, accounting for only 3% of the variance, Kuppens, Laurent, Heyvaert, & Onghena, 2012).

Despite these limitations, this study extends our understanding of the developmental course of aggression in several ways. First, this is the longest continuous investigation of a single cohort of children’s involvement in both social and physical aggression. Following children across a span of ten years enhances our understanding of how aggressive behavior unfolds from middle childhood through late adolescence, a period that is particularly influential on their adult adjustment (Laub & Sampson, 2003; Moffitt, 1993). This is the first longitudinal study of social aggression to capture both the transition from elementary school into middle school and from middle school into high school; thus the stability observed is all the more remarkable. Another important strength of this paper is the use of teacher reports of aggressive behavior. Whereas previous examinations of the development of aggressive behavior have often relied on parent (Coté et al., 2007; Pagani et al., 2010) or self-reports (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2008), teacher reports of aggressive behavior provide an independent rater at each assessment. Furthermore, because teachers have the opportunity to observe children in peer environments, they may be able to provide a more complete assessment of children’s involvement in both social and physical aggression (Youngstrom, et al., 2000). Another strength of this study is that different raters provided information on parenting and children’s aggression, thus relations between parenting variables and aggression found here are not the result of shared method variance, which could be the case in most studies to date that have relied on parents as reporters of parenting and children’s aggression (Kawabata et al., 2011).

An important direction for future research is to examine the ongoing transactional processes between parents and children over time that likely shape the development of social and physical aggression. Although interparental conflict strategies and parenting behaviors may predict children’s aggression, elevated levels of youth aggression may also elicit interparental conflict and parenting behaviors. Examining these bidirectional relations over time may provide a better understanding of the mechanisms that underlie the relation between children’s aggression and parent behaviors.

Future research should also examine the consequences of following different social and physical aggression trajectories for psychological adjustment. Having engaged in high levels of social or physical aggression for the previous ten years, perhaps even at stably declining levels, may be an important predictor of criminal behavior, personality disorders, and problems with romantic and peer relationships. It is also interesting that those participants on the high-desisting trajectory for social aggression showed a much slower decline in aggression than those on the high-desisting physical aggression trajectory. Given the increasing social and legal-consequences of engaging in physically aggressive behavior as youth enter adulthood, it is not surprising that those engaging in the highest levels of physical aggression showed more rapid declines than those engaging in the highest levels of social aggression. Because adults may continue to engage in socially aggressive behaviors with legal impunity, an important future direction is to identify whether those following elevated social aggression trajectories continue to decline, or if their involvement levels off in adulthood. Continuing to engage in social aggression in adulthood could impair friendships and romantic relationships, disrupt relationships with colleagues in the workplace, and possibly contribute to the intergenerational transmission of social aggression.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the children and families who participated in this research, an outstanding local school system that wishes to be unnamed, a talented team of undergraduate research assistants, and NIH grants R01 MH63076, K02 MH073616, R56 MH63076, and R01 HD060995.

Footnotes

Low income was also calculated as those individuals in the lowest two brackets for at least 65% and 85% of their annual responses; subsequent analyses revealed similar patterns of results.

Analyses were conducted using the medium and high groups as the comparison; the results showed the same general pattern.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:213–232. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic review. Review of General Psychology. 2004;8:291–322. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J, Coyne SM. An Integrated Review of Indirect, Relational, and Social Aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2005;9:212–230. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0903_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology. 1971;4:1–103. doi: 10.1037/h0030372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman LR, Andershed A. Predictors and outcomes of persistent or age-limited registered criminal behavior: A 30-year longitudinal study of a Swedish urban population. Aggressive Behavior. 2009;35:164–178. doi: 10.1002/ab.20298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkqvist K, Lagerspetz K, Kaukianen A. Do girls manipulate and do boys fight? Developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 1992;18:117–127. doi: 10.1002/1098-2337(1992)18:2%3C117::AID-AB2480180205%3E3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brame B, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE. Developmental Trajectories of Physical Aggression from School Entry to Late Adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2001;42:503–512. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broidy LM, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE, Bates JE, Brame B, Dodge KA, Fergusson D, Vitaro F. Developmental Trajectories of Childhood Disruptive Behaviors and Adolescent Delinquency: A Six-Site, Cross-National Study. Developmental Psychology. 2003;29:222–245. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D. Intimacy of Friendship, Interpersonal Competence, and Adjustment during Preadolescence and Adolescence. Child Development. 1996;61:1101–1111. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.ep9102040966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card NA, Stucky BD, Sawalani GM, Little TD. Direct and Indirect Aggression During Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-Analytic Review of Gender Differences, Intercorrelations, and Relations to Maladjustment. Child Development. 2008;79:1185–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleverly K, Szatmari P, Vaillancourt T, Boyle M, Lipman E. Developmental trajectories of physical and indirect aggression from late childhood to adolescence: Sex differences and outcomes in emerging adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:1037–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coolahan K, McWayne C, Fantuzzo J, Grim K. Validation of a multidimensional assessment of parenting styles for low-income African American families with preschool children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2002;17(3):356–373. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(02)00169-2,. [DOI] [Google Scholar]