Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) is an important signaling molecule in the human body, playing a crucial role in cell and neuronal communication, regulation of blood pressure, and in immune activation. However, overproduction of NO by the neuronal isoform of nitric oxide synthase (nNOS)is one of the fundamental causes underlying neurodegenerative disorders and neuropathic pain. Therefore, developing small molecules for selective inhibition of nNOS over related isoforms(eNOS and iNOS) is therapeutically desirable. The aims of this review focus on the regulation and dysregulation of NO signaling, the role of NO in neurodegeneration and pain, the structure and mechanism of nNOS, and the use of this information to design selective inhibitors of this enzyme. Structure-based drug design, the bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of these inhibitors, and extensive target validation through animal studies are addressed.

Introduction

The term neurodegenerative disorder is used to catalog diseases that cause an irreversible and gradual breakdown of neuronal structure and function. Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s diseases (AD, PD, and HD, respectively) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease) are historically classified as the major neurodegenerative disorders, although progressive neuronal damage is also found in cerebral palsy, head trauma, stroke, and ischemic brain damage. Neurodegeneration involves a host of cellular and biochemical changes, including accumulation of intracellular and extracellular protein aggregates, loss of normal cell signaling, apoptosis, and necrosis of neurons. These changes lead to symptoms characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases such as memory loss, disorientation, and psychological, motor, and cognitive deficits. Because of both the increasing catastrophic human and economic costs of these disorders and the scarcity of effective therapeutics, the need for new and effective treatments for these disorders is of supreme urgency.

The Role of Nitric Oxide in Neuronal Function and Neurodegeneration

Neurodegeneration is attributed to a cascade of processes, and with the advancement of neuroscience, some of the key components of these pathways have been realized. One such pathway under investigation for pharmaceutical intervention regulates the level of nitric oxide (NO) in the brain. NO is a small, highly soluble, and diffusible free radical that acts as a second messenger throughout the human body. Via predominant signaling through the cyclic guanosine-3′,5′-monophosphate (cGMP) pathway,1 NO regulates a variety of processes ranging from the control of blood pressure and smooth muscle relaxation to immune activation and neuronal signaling. NO is endogenously generated from l-arginine by a class of heme-dependent enzymes called nitric oxide synthases (NOSs). There are three isoforms of NOS: constitutively expressed endothelial NOS (eNOS), which regulates vascular tone and blood flow; inducible NOS (iNOS), which is transiently expressed during immune activation, and neuronal NOS (nNOS), which is found throughout the nervous system and skeletal muscles.2 nNOS plays a significant role in neuronal signaling and is also constitutively expressed, with the dominant splice variant localized to postsynaptic terminals near N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors.3,4

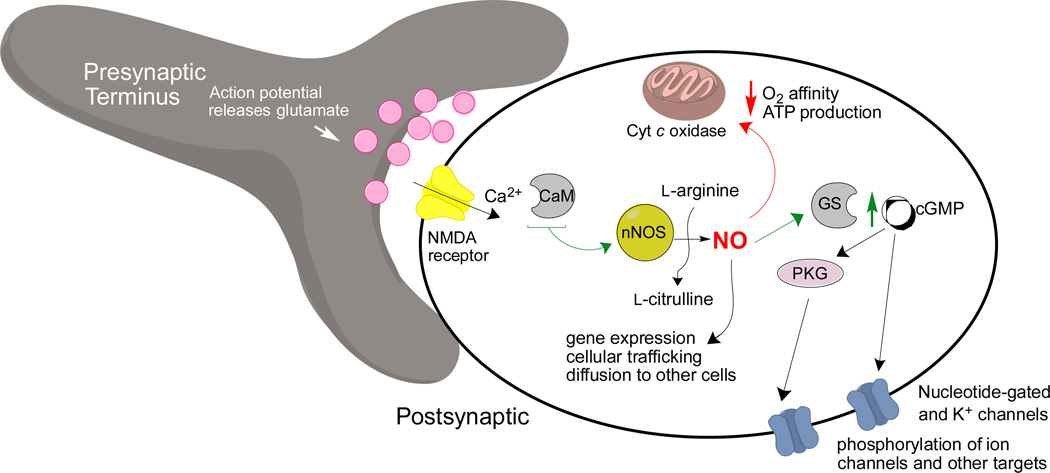

An enormous body of research has elucidated the function of NO and nNOS in the brain and central nervous system (CNS). In normal nanomolar concentrations, NO in the brain is actually neuroprotective, and its formation is induced by nNOS activation in a calcium/calmodulin (Ca2+/CaM)-dependent manner following stimulation of Ca2+-permeable NMDA receptors (Figure 1).4,5 This Ca2+ influx, also regulated by voltage-gated calcium channels, stimulates nNOS.6,7 After NO production, the resultant downstream NO, cGMP, and protein kinase G (PKG) signaling modulate neurotransmission and metabolic processes by a number of different pathways, including action at cytochrome coxidase8 and various ion channels.9,10 On a global physiological scale, NO-related processes are implicated in the circadian and respiratory rhythms,4 gut motility,11 some portions of central release of various reproductive hormones,12 long-term depression, long-term potentiation, and various types of learning and memory processes in the cerebellum, hippocampus, and neocortex.13,14,15

Figure 1.

Normal Ca2+-mediated nitrergic signaling pathways at a synapse. Abbreviations are as follows: GS: soluble guanylyl cyclase; PKG: protein kinase G; CaM: calmodulin; ATP: adenosine triphosphate.

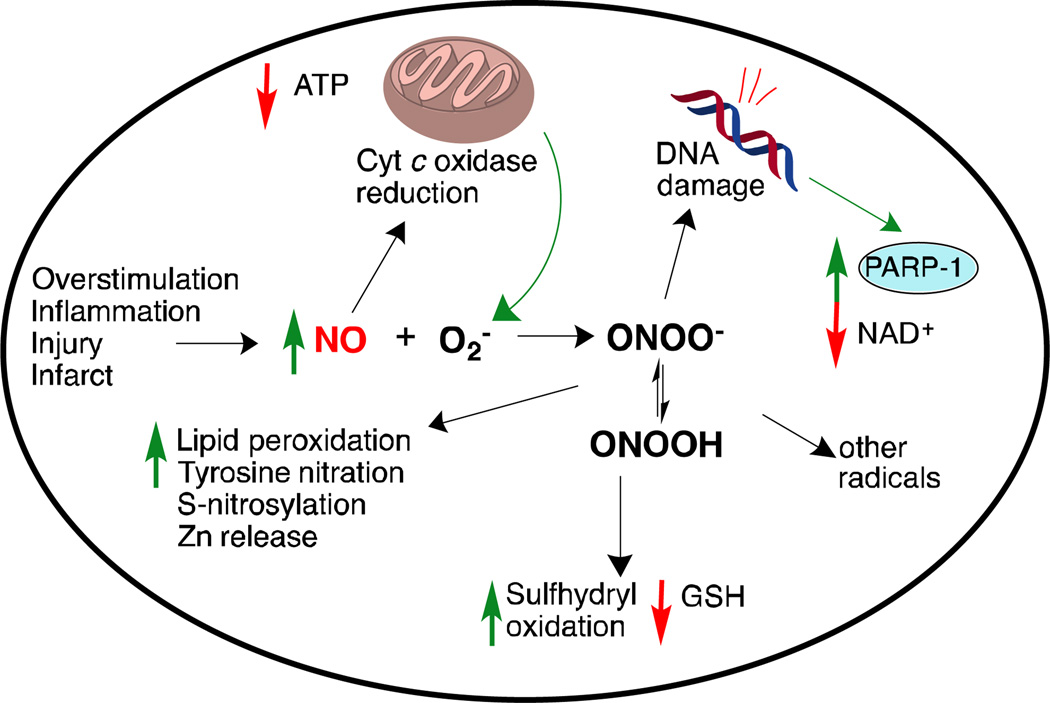

Following an event that causes neuronal damage (such as an infarct, inflammation, release of NO from surrounding cells or the immune or vascular system, or excessive NMDA receptor activation), concentrations of NO in the brain can surge several orders of magnitude,16 where it is neurotoxic(Figure 2).NO-mediated neurotoxicity proceeds via several mechanisms. Excess NO itself can impair cellular energy production via interaction with the iron-sulfur centers in the mitochondrial electron transport chain.17It can also produce reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Reaction of NO and superoxide ion (O2-,18,19which nNOS can also form under low arginine concentrations)generates peroxynitrite (ONOO-) and peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH). These dangerous free radicals can also decompose into other reactive species, such as hydroxyl radical and peroxides.20

Figure 2.

Dysfunctional NO signaling and damage mechanisms following inflammation, infarct, or NMDA-receptor overstimulation. Abbreviations are as follows: GSH: glutathione; PARP-1: poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1; NAD+:nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide.

Oxidative stress from free radicals includes DNA damage and lipid peroxidation, in addition to protein structural damage from tyrosine nitration,21 excess S-nitrosylation,22 and oxidation of cysteine residues to unwanted disulfides. These structural changes can lead to protein misfolding and aggregation. Furthermore, the oxidative stress can deplete glutathione stores23,24 (causing upregulation of glutathione as a protective response), release zinc from intracellular reserves25,26 (thus inducing pro-apoptotic cascades), and trigger excessive DNA-repair mechanisms (such as PARP-1),which result in low NAD+, increased energetic stress, and cell death.27 NO can also reduce cytochrome coxidase and interfere with complex III of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, leading to the release of even more superoxide from mitochondria.5

There is much evidence linking dysregulation in nitrergic signaling, nNOS overexpression, and oxidative stress to neurodegenerative disorders. In the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, where NO levels are high,28 there is elevated tyrosine nitration; it is believed that oxidative protein damage associates with β-amyloid plaque buildup. Excess NO may also trigger hyperphosphorylation and subsequent accumulation of tau protein.29,30In the Parkinson’s brain, tyrosine nitration contributes to the α-synuclein aggregates (Lewy bodies),31 as nitrated α-synuclein is highly insoluble and degradation resistant.32 Additionally, parkin (a ubiquitin ligase implicated in the survival of dopaminergic neurons) is S-nitrosylated and inactivated in mouse models of Parkinson’s.33 In both human ALS patients and animal models of ALS, nNOS is upregulated in motor neurons and localizes to regions of neurofilament accumulation, where it may nitrate these proteins,34while it is hypothesized that excess NO produced by nNOS may contribute to glutamate-induced excitotoxicity and cellular death in Huntington’s disease. 35

NO has also been indicated as a cause of HIV coat protein-mediated neuronal death in AIDS-related dementia,36 and nNOS is found heavily localized in the trigeminal nucleus and vasculature in humans and rats, an area that is heavily implicated in migraine pain, suggesting that NO plays a role in the pathology of pain as well.37Related to the latter findings, excess NO is also implicated in inflammation and degeneration of peripheral neurons,38 which can cause neuropathic pain. Symptoms of this disorder include hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to pain) and allodynia (pain due to non-painful stimuli) at the site of the insult.

Validation of nNOS as a Drug Target

Some of the research into the inhibition of nNOS as a therapeutic strategy was performed using animals deficient in nNOS. Moskowitz and co-workers39 used nNOS-knockout mice. When ischemia was induced via occlusion of the animals’ middle cerebral artery, the knockout mice developed significantly smaller infarcts and had fewer negative neurological symptoms compared to the wild-type mice. It was also shown that the mutated mice had a stronger resistance to tissue injury and cell death after transient global ischemia.40In another study, nNOS-knockout mice did not show neuropathic pain following spinal nerve injury.41 Administering an nNOS inhibitor to the wild-type animals following injury, however, also dramatically alleviated their neuropathic pain.

The use of nNOS inhibitors has likewise shown promise in models of Parkinson’s disease and ALS. When MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) is administered to baboons, it produces rapid and permanent dopamine loss and neurological and biochemical changes consistent with Parkinsonism; administration of an nNOS inhibitor blocked dopamine depletion, loss of neurons, and motor and cognitive deficits.42nNOS inhibition also prevented reduction in the dopamine levels in the striatum of mice administered MPTP.43 In a study by Ikeda and colleagues, the wobbler mouse model of ALS was employed. nNOS inhibition reduced muscle deformities and atrophy, improved muscle weight and paw grip strength, and prevented degeneration of spinal motor neurons.44These examples, taken together, highlight the notion that inhibition of nNOS is a promising strategy for preventing or slowing neurogeneration and neuropathic pain. The goal of this review is to focus on the structure and function of NOS enzymes, describe progress toward development of selective inhibitors, and discuss animal and human studies showing the effectiveness of these inhibitors as potential therapeutics.

Structure and Mechanism of the Nitric Oxide Synthases

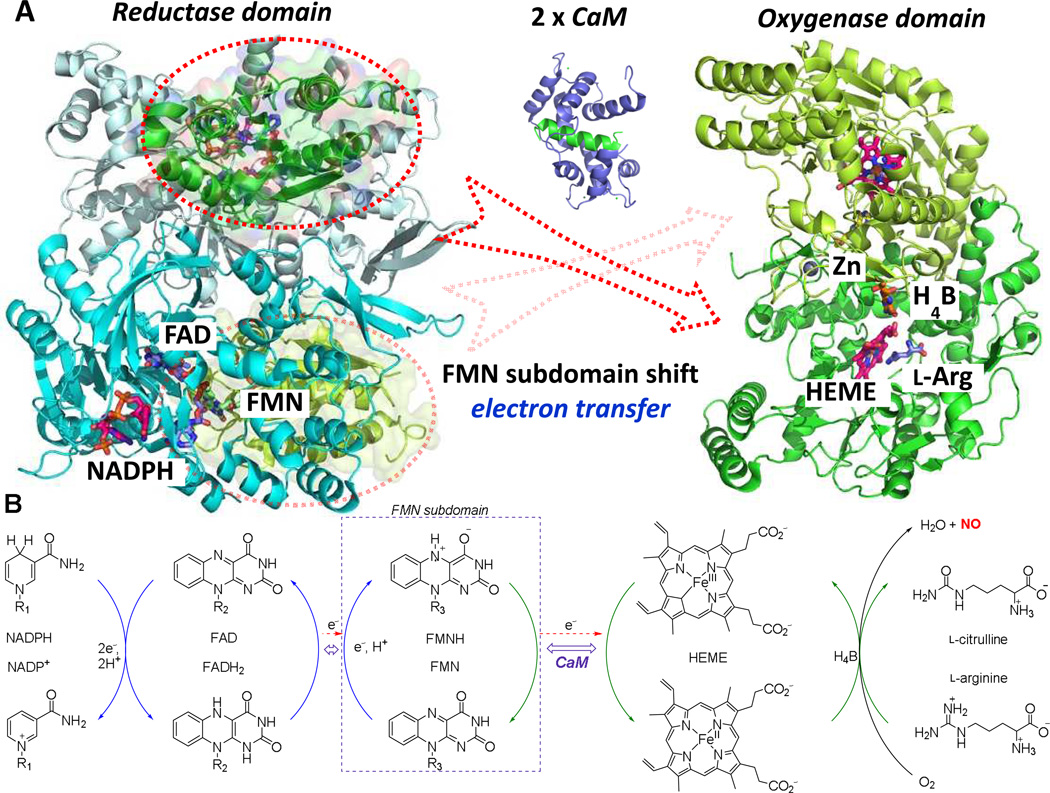

Mammalian NOSs exist as homodimeric enzymes; each monomer consists of a C-terminal reductase domain and an N-terminal oxygenase domain.45 These two domains are connected by a calmodulin (CaM) binding sequence. The general structures of the reductase and oxygenase domains are shown in Figure 3A. The oxygenase domain contains a non-catalytic zinc (Zn2+), heme, tetrahydrobiopterin (H4B), and the substrate(l-arginine) binding site, where catalysis occurs. Zn2+ binds to two pairs of cysteine residues to form a structurally stable zinc-tetrathiolate cluster,46which is the main driving force for dimerization, as each cysteine pair is from one monomer.47H4B binds to a propionate of the heme in the arginine binding site and also forms a part of the NOS dimerization interface.48The reductase domain, which contains NADPH, FAD (flavin adenine dinucleotide), and FMN (flavin mononucleotide) cofactors, is divided up into an NADPH-FAD binding subdomain,49and a FMN binding subdomain.50Because these two subdomains are connected by a flexible dodecapeptide,51,52they can perform a hinge movement when CaM, sensitized by calcium, binds to its binding site.53

Figure 3.

(A) nNOS dimeric oxygenase domain (1ZVL), dimeric reductase domain (1TLL), and calmodulin, with a helix of the calmodulin binding site depicted in green(2O60). The reductase domain produces electrons from NADPH and transfers them to the oxygenase domain using the FMN subdomain shuttle. Calmodulin is involved in control of the FMN subdomain shift. The FMN subdomain is circled and colored green to match with the distinct surfaces of the oxygenase domain. (B) Schematic electron transfer from NADPH to heme for NO production. The specific mechanism of catalysis is not shown here.

The redox potentials54,55 of NADPH (−320 mV), FAD (−280 mV), FMN (−274 mV), heme (−248 mV), and H4B (−180 mV) explain the thermodynamic process of electron flow. This stepwise electron transfer is maintained from the electron donor NADPH to the electron acceptor heme, via FAD, FMN, and H4B redox cofactors (Figure 3B).The two-electron oxidation of freshly bound NADPH initiates the two-electron reduction of FAD. Electron transfer from FAD to FMN is then conducted through the interface between the FAD and FMN subdomains. The mechanism of electron transfer from the FMN subdomain to heme was initially not clear because FMN is located deep inside the reductase domain, inaccessible to the heme domain.56It has been hypothesized that under normal conditions, a conformational change in the reductase domain (specifically the FMN subdomain) to allow interaction with the heme domain is possible.57Unlike in nNOS and eNOS, iNOS binds tightly with CaM; consequently, the crystal structure of an FMN subdomain in complex with calcium and CaM is available;58 this provided the basic information about the binding between the reductase domain and CaM. This partial crystal structure, in conjunction with docking studies among NOS domains, resulted in the hypothesis that the two FMN subdomains quickly shuttle between the reductase and oxygenase domains to transfer electrons.59 Recently, the Marletta group aimed to elucidate further the 3D-domain structure of NOS by probing interactions of isolated NOS domains using a hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) technique.60The HDX-MS technique can measure the exchange rate of backbone amide protons with a deuterated buffer to statistically report the solvent accessibility and local environment of residues. By measuring the H/D exchange rate, they reported the interfaces relevant to protein dynamics and the active interfaces of the secondary structure. Their studies of site-specific interface mutants confirmed that an interface between calmodulin and the heme is formed during catalysis and that this interface is necessary for efficient electron transfer from FMN to heme.

NO production in the oxygenase domain requires five single-electron oxidations of the substrate l-arginine utilizing the FMN and H4B redox cofactors, oxygen, and water. This process includes two distinct steps; formation of Nω-hydroxy-l-arginine (l-NHA) from arginine, and conversion of this intermediate to citrulline and NO. The first step is similar to that of a cytochromeP450 oxidation;61the FeII of heme activates molecular oxygen by a stepwise one-electron reduction to form FeIV=O. The activated oxygen of FeIV=O undergoes nucleophilic attack by the guanidinium nitrogen of l-arginine to form l-NHA. The mechanism of the second step is far from clear, but ferric superoxide (FeIII-OO-)may perform a nucleophilic attack on the carbon of the hydroxyguanidine of the l-NHA side chain, which results in the formation of NO and citrulline. More detailed mechanisms of NO production at the oxygenase domain have been well reviewed elsewhere.62,63,64 There are several hypotheses related to the role of H4B during oxygenation: it may promote NADPH oxidative coupling and inhibit superoxide and hydrogen peroxide formation,65or it may modify the heme environment to encourage oxidation.66More recent studies performed by Marletta and co-workers67 suggest a dual redox cycling role for the H4B during the second step of NO synthesis froml-NHA. They proposed the activation of oxygen to a heme-bound FeIII occurs with one electron that comes from NADPH and one from the H4B cofactor. This FeIII–OOH then undergoes nucleophilic attack onl-NHA, and rearrangement leads to a FeIII-bound nitroxyl anion, citrulline, and water. Further oxidation by H3B radical forms a FeIII-NO complex, from which NO is released.

Structural Differences Between NOS Isoforms

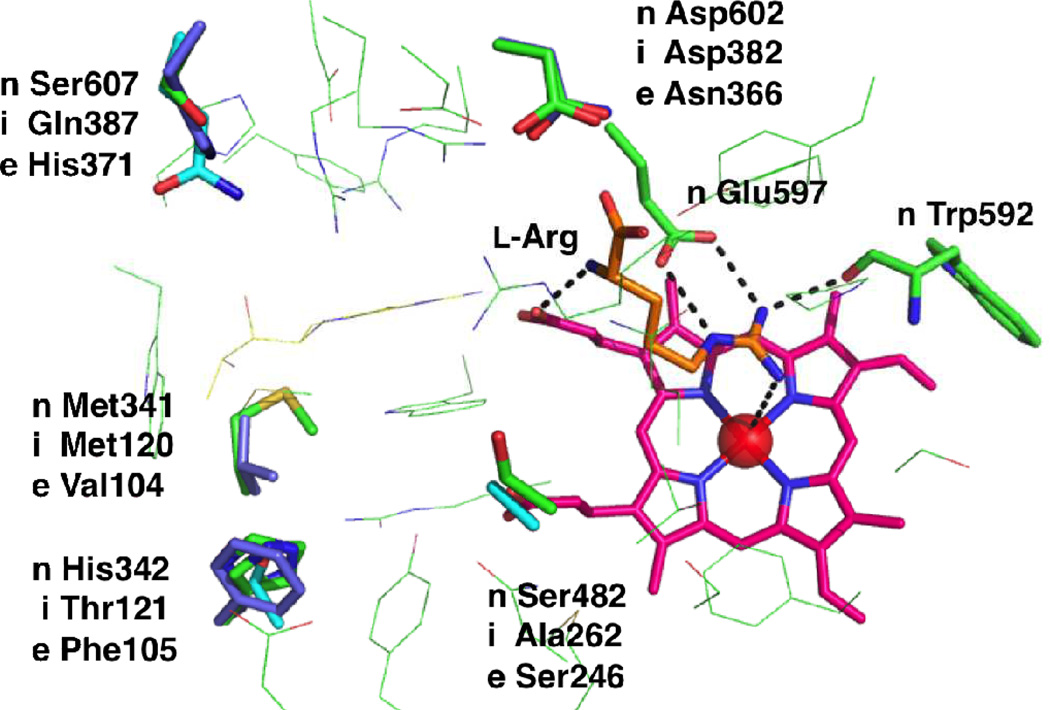

The binding mode of l-arginine in the three mammalian NOSs (nNOS, iNOS, and eNOS)is identical (Figure 4); l-arginine binds in a pocket above the heme, stabilized by a strong hydrogen-bonding network. Two nitrogens of the guanidine moiety of l-arginine bind tightly with the conserved carboxylate of Glu597 in human nNOS (Glu377 for iNOS; Glu361 for eNOS) via a bifurcated salt-bridge. The guanidine also forms a hydrogen bond to the amide carbonyl of Trp592 (Trp372 for iNOS; Trp356 for eNOS).The N-terminal nitrogen of arginine interacts with one heme propionate by a hydrogen bond. These interactions are identical in all NOS isozymes; consequently, designing potent and isoform-selective inhibitors is challenging and requires additional and alternative interactions than the fundamental coordination.

Figure 4.

Residue differences among three human NOS isoforms [n: nNOS (green; based on homology model), i: iNOS (cyan; PDB 4NOS), e: eNOS (purple; PDB 3NOS)]. Note that in rat nNOS, His342 is Leu337.

During the initial period of inhibitor development (late 1980s-early 1990s), identification of isoform-selective molecules was especially challenging because no crystal structures were available. It was not until the late 1990swhen X-ray crystal structures of iNOS68,69 and eNOS46 became available; in 2002 the crystal structure of nNOS70also became available. The crystal structures of a ligand bound to the isozymes allowed acute pairwise comparison of ligand-isoform complexes, as well as computer-based drug design.71,72 Alignment of the crystal structures of isozymes reveals several non-identical residues in the active site. As shown in Figure 4, the most distinguished residues among human NOSs are Ser607 and His342; Ser607 of human nNOS is different in iNOS (Gln387) and eNOS (His371). Similarly, His342 of human nNOS is different in iNOS (Thr121) and eNOS (Phe105); likewise, in rat nNOS (which has been used for extensive drug discovery efforts), Leu337 replaces His342. The electronic and steric effects of these residues in the binding sites are quite different; therefore they can be good targets for selective inhibition. It is also known that two additional residues are different between nNOS and eNOS. Neuronal Asp602 and Met341 are different from endothelial Asn366 and Val104, respectively. Additionally, the neuronal Ser482 site is different from inducible Ala262. Interestingly, the difference of Asp602/Asn366 in the nNOS/eNOS binding site makes the nNOS active site more electronegative compared to that of eNOS (see the competitive inhibitor section for more details of the role of these residues in the rat isozyme).In addition to the aforementioned residue differences, the residues lining the NOS binding pockets are not rigid entities; upon ligand binding, conformational changes in certain residues can provide extra isoform-specific binding pockets. This “induced fit” strategy has also been used to design selective NOS inhibitors. Further examples are detailed in the competitive inhibitor section (vide infra).

Inhibition of Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase

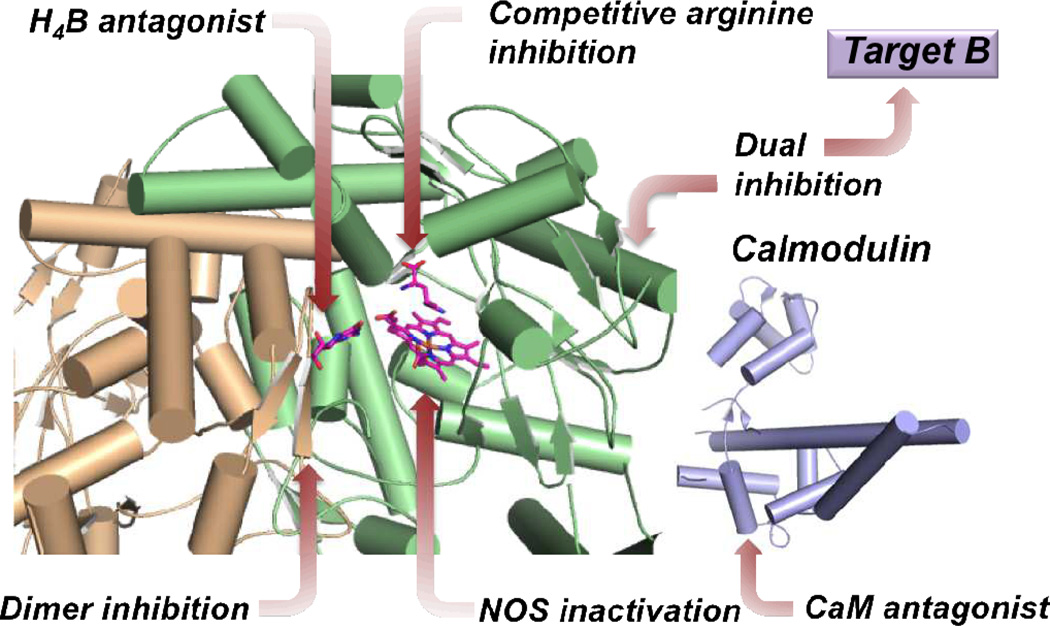

Many attempts have been made, since the discovery of the role of nNOS in neurodegeneration and pain, to inhibit or inactivate nNOS selectively over its other isoforms for therapeutic purposes, as inhibition of the wrong isoform could cause adverse side effects. Figure 5 summarizes different approaches to nNOS inhibition. These varied approaches range from simple inhibition via substrate or cofactor mimicry (competitive inhibition) and mechanism-based inactivation, to the inhibition of protein-protein interactions within nNOS itself (dimer inhibition) and between the enzyme and regulatory proteins (CaM antagonism). Additional attempts to inhibit nNOS in conjunction with other targets implicated in neurodegeneration and pain (dual inhibition)also are discussed.

Figure 5.

Representation of different sites and modes of inhibition of neuronal NOS.

Competitive Substrate Inhibitors

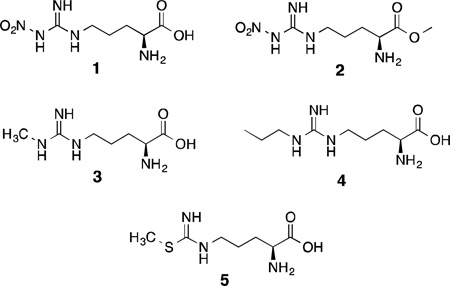

Arginine and Citrulline-Based Analogues

The majority of investigations into the inhibition of nNOS are related to design and evaluation of reversible inhibitors that mimic either l-arginine or l-citrulline. These inhibitors are designed to simply out-compete l-arginine (or intermediates) and bind in the enzyme’s active site, thus preventing arginine turnover. Early investigations (ca. 1990–1995) were focused on the development of inhibitors derived from arginine itself, and one of the first nNOS inhibitors discovered was NG-nitro-l-arginine [l-NA (1)].73 This compound is a potent bovine nNOS inhibitor(Ki = ~15 nM)74 that undergoes little metabolism and rapidly penetrates the mouse brain, where it was shown to attenuate a drug-induced increase in cerebellar cGMP via decrease of NO production.75 The methyl ester of 1, l-NAME (2), is more potent, possibly because of increased bioavailability.73 Nonetheless, these simple nitroarginines are nonselective NOS inhibitors, and while 1 has around 300-fold selectivity in favor of nNOS over iNOS,46nitroarginines cause severe hypertension when administered to animals as a result of potent inhibition of eNOS as well.76

Many modifications made to l-arginine at positions other than the guanidine moiety (e.g., introduction of aromatic groups, sulfonic acids, and heterocycles) resulted in compounds that are neither NOS inhibitors nor substrates,77 but many arginine derivatives alkylated on the guanidine group possess NOS inhibitory activity. Hibbs78 first described Nω-methyl-l-arginine (l-NMA, 3) as a NOS inhibitor. Although l-NMA was shown to accumulate in the brains of rats and cattle,79,80 and showed some ability to attenuate migraine headache in human clinical trials,81 this compound also has adverse cardiovascular effects in both animals and humans because of nonselective NOS inhibition.82,83 Similarly, higher alkylarginines (containing dimethyl, cyclopropyl, etc.) are also inhibitors of multiple NOS isoforms.73,84 On the contrary, Nω-propyl-l-arginine (4) shows a Ki of 57 nM, very high n/i and modest n/e selectivity (using bovine nNOS, bovine eNOS, and murine macrophage iNOS) when compared to other alkyl derivatives such as Nω-allyl, propargyl, and ethyl,85 and has some ability to irreversibly inhibit nNOS as well (see the section on nNOS inactivators).86

Narayanan and Griffith reported a series of arginine-like thiocitrulline, homothiocitrulline, and S-methylthiocitrulline derivatives as nNOS inhibitors, although these compounds do not distinguish between the neuronal and inducible isoforms.87 A similar trend was observed in a more recent study of racemic 3-substituted isothiocitrulline analogues based on l-S-methylisothiocitrulline [l-MIT (5),88,89 which is more potent than 3 and has high n/e selectivity but little n/i selectivity].These compounds, as a whole, also displayed little n/i selectivity, but some n/e selectivity was observed in some cases, depending on the identity and stereochemistry of the 3-substituent.88 In all, there are many drawbacks associated with the use of arginine-based inhibitors as drugs, most of which are the result of their nonspecific action against multiple NOS isoforms and their high basicity, polarity, and hydrogen-bonding potential, which hamper both gut absorption and brain penetration in the absence of an active transport system.90

Dipeptide- and Peptidomimetic-Based Inhibitors

A number of investigations have sought to improve upon the activity, tune the isoform selectivity, and induce druglike properties in arginine analogues by incorporating them into larger molecules. A series of dipeptides containing alkylated isothiocitrullines was designed by Nagano, Higuchi, and colleagues,89 in which large, hydrophobic dipeptides resulted in primarily iNOS-selective compounds with lower binding affinities, whereas smaller derivatives were more selective for nNOS, suggesting that the three NOS isoforms have different binding pocket sizes and that inhibitor size can be used to select for a given NOS isoform (a hypothesis that would later be proven correct by crystallography). These compounds also showed activity in cellular NOS assays, indicating the ability to cross cell membranes.89

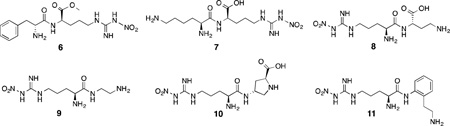

l-NA (1) and l-NAME (2)have also been incorporated into peptides. An initial report by Thiemermann and co-workers described the NOS inhibitory activity of nitroarginine-containing dipeptides, which raised mean arterial blood pressure when administered to anesthetized rats.91 Silverman et al. reported that d-Phe-d-Arg-NO2-OMe (6) inhibited nNOS with a Ki of 2 µM and displayed a remarkable ~1800-fold selectivity for nNOS over iNOS.92 It was then hypothesized that by changing the chemical properties of the other amino acid in the dipeptide that the isoform selectivity of these peptides could be further refined.

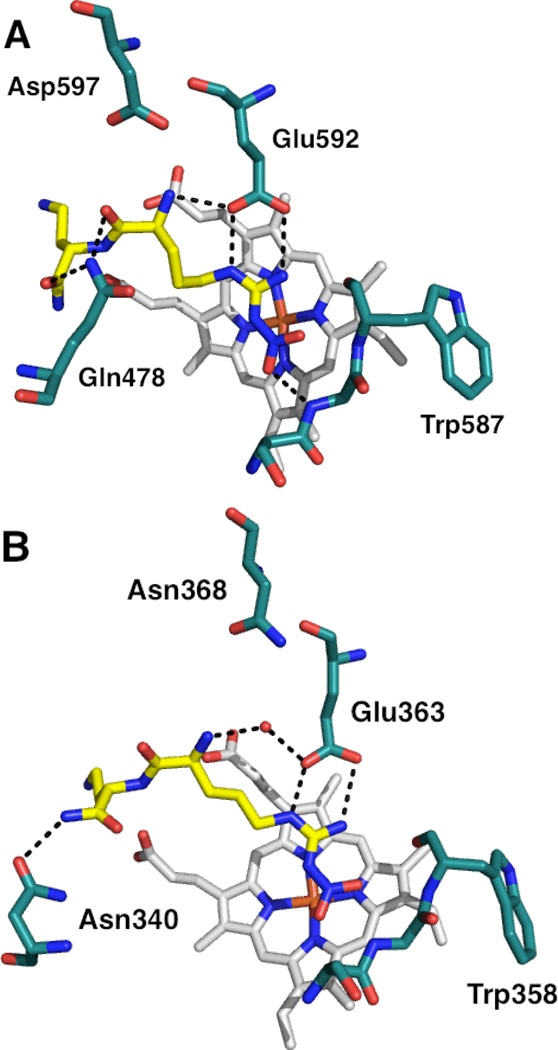

A screen of 152 dipeptide amides containing nitroarginine moieties was conducted, and it was revealed that peptides containing basic nitrogenous groups (such as lysine and histidine) were the most potent nNOS inhibitors, and when the lysine chains were truncated by one or several methylene units, even more potent and selective inhibitors resulted, down to a 0.13 µM Ki against nNOS(for 8) and up to 2765-fold nNOS/iNOS selectivity (for 7) and 1538-fold selectivity over eNOS (for 8).93The high activity of compounds with basic side chains suggested an important electrostatic interaction in the nNOS active site. Nonetheless, despite their activities, these nitroarginine-based dipeptide inhibitors also have many drawbacks. Concerns over the multiple charges of the molecules, the low likelihood of oral bioavailability, and the lability of the peptide bond promoted modifications such as amide-bond reduction,94conformational restriction,95,96 and introduction of lipophilic groups,97 which gave rise to a variety of increasingly potent and selective peptidic and peptidomimetic inhibitors, such as 9, 10, and 11. The high activity of these inhibitors was still a result, in part, of the presence of their basic side chains. Substitution of the terminal amines with hydroxyl groups increased then NOS Ki more than an order of magnitude, further reinforcing the importance of electrostatic interactions in the active site over hydrogen bonding.98,99 It was hypothesized that these basic groups interacted with some anionic residue in the nNOS active site that was absent in eNOS and thus stabilized the nNOS-inhibitor complex; this hypothesis was also supported by energy calculations.100 In 2003, X-ray crystallography of nitroarginine dipeptides and peptidomimetics in complex with rat nNOS revealed this anionic residue to be Asp597 (analogous to Asp602 in the human isozyme).100 As shown in Figure 6, the nitroarginine guanidino moiety interacts with active site Glu592 (as the guanidine group of arginine interacts with human nNOS’ Glu597); in nNOS, the electrostatic interaction of Asp597 with the inhibitor forces the bound inhibitors into a “curled” conformation (Figure 6A), where they can make maximal electrostatic contacts with the surrounding residues or directly with Asp597 (resulting in high selectivity for nNOS). This electrostatic stabilization is lost in bovine eNOS (Figure6B), where Asp597 in nNOS is Asn368 in eNOS, and the inhibitors adopt an “extended” conformation with less direct electrostatic contact. Site-directed mutagenesis studies of nNOS (where Asp597 was mutated to eNOS’ asparagine) exhibited similar changes in the binding mode, when the mutant complexes were examined by X-ray crystallography, and similar decreases in potency.100

Figure 6.

X-ray crystallographic binding modes of dipeptide amide 8 bound to rat nNOS (A; PDB 1P6H) and bovine eNOS (B; PDB 1P6L). Polar interactions are shown as dashed lines. Note the tighter electrostatic interaction between the α-amine of 8 and Glu592 (in A) from the negative charge of Asp597 (4.9 Å away).

An aromatic, reduced peptide-bond nitroarginine inhibitor, 11, was tested in a rabbit model for cerebral palsy, in which hypoxic brain damage was induced in the fetuses of pregnant rabbit dams.101,102 When administered intrauterine prior to the start of the hypoxic event, compound 11 protected fetal rabbit brains from neurodegeneration in a dose-dependent manner; likewise, the culture of fetal rabbit brain cells in the presence of 11 produced concentration-dependent protection from apoptosis and death.103

In Silico Design and Improved Pharmacophores; Rise of the Aminopyridine

The availability of all three NOS isoform crystal structures46,68,70 laid the groundwork for several computer-aided drug design investigations. A combined effort by The Scripps Research Institute and AstraZeneca generated and used a method known as anchored plasticity, which was built upon the crystallography and prior knowledge about the size differences between the NOS isoforms’ active sites.104

With the precedent that 2-aminopyridines105 and quinazolines106 inhibited NOS enzymes, this portion of the inhibitor was “anchored” into the conserved heme-binding pocket found in all three isoforms. Next, various rigid and bulky substituents were attached to reach subtly different isoform-specific pockets (specifically those obtained via conformational changes in flexible residues in iNOS, such as Gln257 and Arg260, upon inhibitor binding). By using this “induced-fit” method, the authors were able to design novel heterobicyclic amidine-based inhibitors that were selective for iNOS.

Several other computer-based approaches sought to elucidate the molecular determinants of isoform selectivity and the pharmacophoric elements required for potent nNOS-selective inhibition. The active sites of the NOS isoforms were mapped using molecular interaction fields (MIFs)72 which were obtained by the use of GRID107(which uses “probes” covering steric, hydrophobic, H-bond donor/acceptor, or electrostatic interactions), and the MIFs were compared between the three isoforms using consensus principal component analysis to identify differences between the three active sites. By this analysis, it appears that the predominant determinants of selectivity are hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions. Subsequent docking of dipeptide-based inhibitors illustrated that these selectivity “hot-spots” obtained by MIF analysis correlated well with the structure-activity relationship (SAR) of nitroarginine-containing dipeptides.72

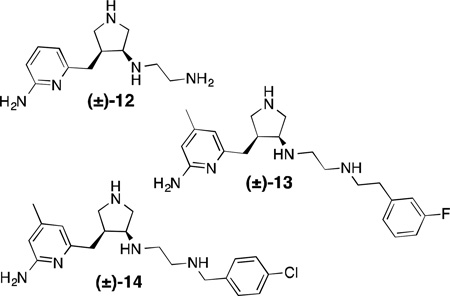

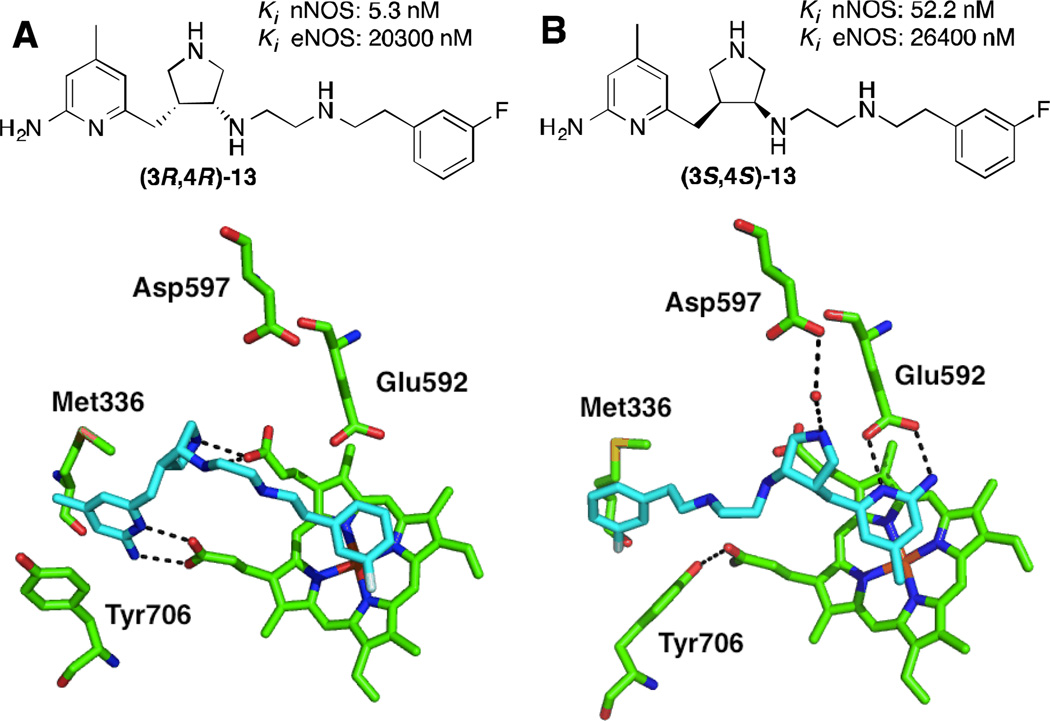

This type of analysis has also been used in de novo design of nNOS inhibitors; both GRID- and MCSS (a random functional group-based search method)-derived MIFs have been used to derive the minimal pharmacophoric elements required for selective nNOS inhibition. Onto these “pharmacophore maps” were linked a series of fragments (such as 2-aminopyridine and pyrrolidine) to satisfy these pharmacophoric requirements – this strategy has been collectively termed “fragment hopping”.71 Synthesis and evaluation of the pyrrolidinomethyl-2-aminopyridines designed by this method yielded a lead compound (12) with a Ki of 388 nM, >1000-fold selectivity over eNOS, and 150-fold selectivity over iNOS, thus validating this approach. Compound 12 was optimized via subsequent fragment hopping to result in more drug-like leads; lipophilic substituents were added to the aminopyridine, and arylalkyl groups were used to cap the secondary amine.108,109 Two remarkably potent and selective nNOS inhibitors, 13 and 14, were developed by this method. These compounds are interesting from several standpoints; first, different stereochemistry on the pyrrolidine ring of 13drastically alters the potency and selectivity, especially the nNOS/eNOS selectivity. X-ray crystallography indicates that the different isomers adopt two distinct binding modes in rat nNOS’ active site, shown here for the R,R and S,S-enantiomers of 13 (Figure 7).In the “normal” binding mode (Figure 7B), the aminopyridine binds to the active site glutamate, Glu592, while the aromatic tail fits into a peripheral hydrophobic pocket defined by Leu337, Met336, and Tyr706 (here described for the rat enzyme), a region later revealed to be crucial for high nNOS selectivity,110 although this pocket is somewhat smaller in human nNOS. In the “flipped” binding mode (Figure 7A), the aminopyridine sits in this hydrophobic pocket, and the salt bridge is instead formed with a heme propionate, while the non-coordinating aryl ring stacks parallel over the heme.111Also in the flipped mode, a tyrosine residue (Tyr706) swings forward to make a favorable pi-stacking interaction when the inhibitor is present, a contact which is not present in the normal binding mode or in eNOS. As in the anchored plasticity approach, this is another example of isoform-specific induced fit that gives rise to selectivity. Compounds13 and 14 were also tested in the rabbit hypoxia-ischemia fetal neurodegeneration model, where the compound was administered intravenously to the pregnant dam and hypoxia was induced in the fetuses, which were then allowed to come to term. Relative to a saline control, the kits in the treated groups had a remarkable decrease in symptoms of neurodegeneration, including postural and motor defects. No deaths were observed in the treated group for either compound (whereas nearly 50%mortalitywas observed in the control group) and no systemic toxicity was reported.112

Figure 7.

Structures and X-ray crystallographic binding modes of aminopyridine inhibitors bound to nNOS, showing flipped (A; PDB 3JWT) and normal (B; PDB 3JWS) binding modes; (A) depicts the R,R-enantiomer of 13, and (B) the S,S-enantiomer. Polar interactions are shown as dashed lines. Notice how Tyr706 moves forward to make a pi-stacking contact in A, but not in B.

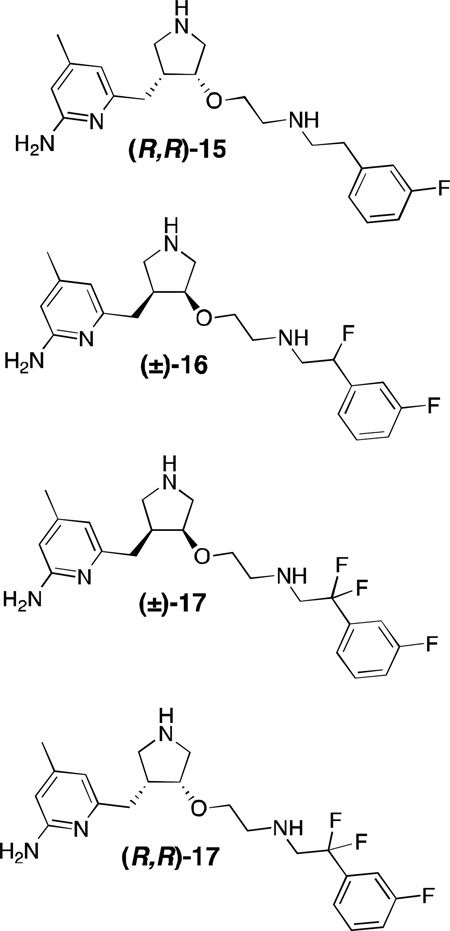

Despite their efficacy, compounds such as 12-14 suffer from many of the same drawbacks as the arginine analogues and dipeptides; they possess many ionizable groups (pKa >9) and hydrogen-bond donors, suffer from high tPSA [total polar surface area; 75–90 Å2; some reports suggest under 80 Å2 is considered optimal for blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeation; under 140 Å2 for oral bioavailability]113,114 and they have a large number of rotatable bonds, making oral bioavailability highly unlikely. Numerous studies were undertaken in attempt to improve the membrane permeation and bioavailability of pyrrolidinomethyl-2-aminopyridines, including alkyl chain fluorination,115,116 the introduction of internal hydrogen-bonding groups,117 lipophilic moieties and aromatic tails,118 alkylation and conformational restriction,119 the introduction of various prodrug moieties and the use of azides as amine surrogates,120 replacement of the aminopyridine with a less basic aminothiazole,121and the replacement of amino linkages with amides and ethers.108,122Most of these approaches were met with diminished activity and selectivity relative to the parent compounds, were synthetically challenging, or did not improve BBB permeation. When the exocyclic secondary amine was replaced with oxygen and the enantiomers separated, an extremely potent compound [(R,R)-15] resulted.108 This compound is among the most potent nNOS inhibitors reported to date, with a Ki of 7 nM (rat nNOS) and exceptional nNOS/eNOS and nNOS/iNOS selectivities of 2667 and 806, respectively, although it is still poorly brain-permeable and not orally bioavailable. Mono-fluorination of the alkyl chains (such as in 16) at positions adjacent to secondary amines decreased their pKa (as to make the inhibitors essentially monocationic at physiological pH), and improved cellular permeability (as evidenced by activity in a cell-based assay).115 Gem-difluorination (to lower the pKa of the vicinal amino group) yielded 17, which improved its half-life in rats; an assay of single enantiomer (R,R)-17 resulted in an estimated oral bioavailability of 22%, and fluorination as a whole only slightly diminished potency and selectivity relative to 15.116

Toward Simpler Aminopyridine Structures

In addition to the concerns about bioavailability, molecules such as 12–17 are challenging to prepare and involve lengthy, multi-step syntheses (>12 steps), difficult chiral resolutions, and diastereomer separations. Although improvements to these syntheses have been made,123 a simpler compound that retains potency and selectivity is more desirable from process chemistry and clinical standpoints. It was envisioned that by removing some of the heteroatoms connecting the aminopyridine and non-interacting aryl ring (to produce monocationic inhibitors) that pyrrolidinomethyl-2-aminopyridines might show some improvements in bioavailability, but these inhibitors had decreased potency and selectivity over the parent compounds and some adopted an unusual binding mode by X-ray crystallography.124

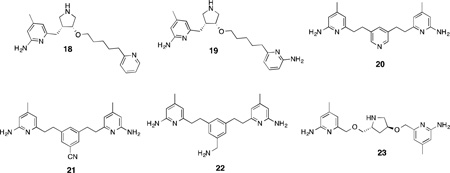

Molecular dynamics simulations indicated that even small isosteric replacements (such as -CH2 for -NH) could significantly affect ligand orientation. Heteroatoms in the linker chains greatly stabilize bound inhibitors and determine their binding mode, and it was hypothesized that introduction of heteroatoms in the non-coordinating aryl ring might have a similar effect. The introduction of a second pyridine or aminopyridine ring resulted in compounds 18 and 19;19, with an nNOS Ki of 30 nM, has 1117-fold selectivity for nNOS over eNOS, 619-fold selectivity over iNOS, and has improved membrane permeability.124 From this lead (19) even simpler symmetrical double-headed aminopyridines were designed;125 the chiral linker regions were replaced with synthetically viable and simple aryl or heteroaryl groups.

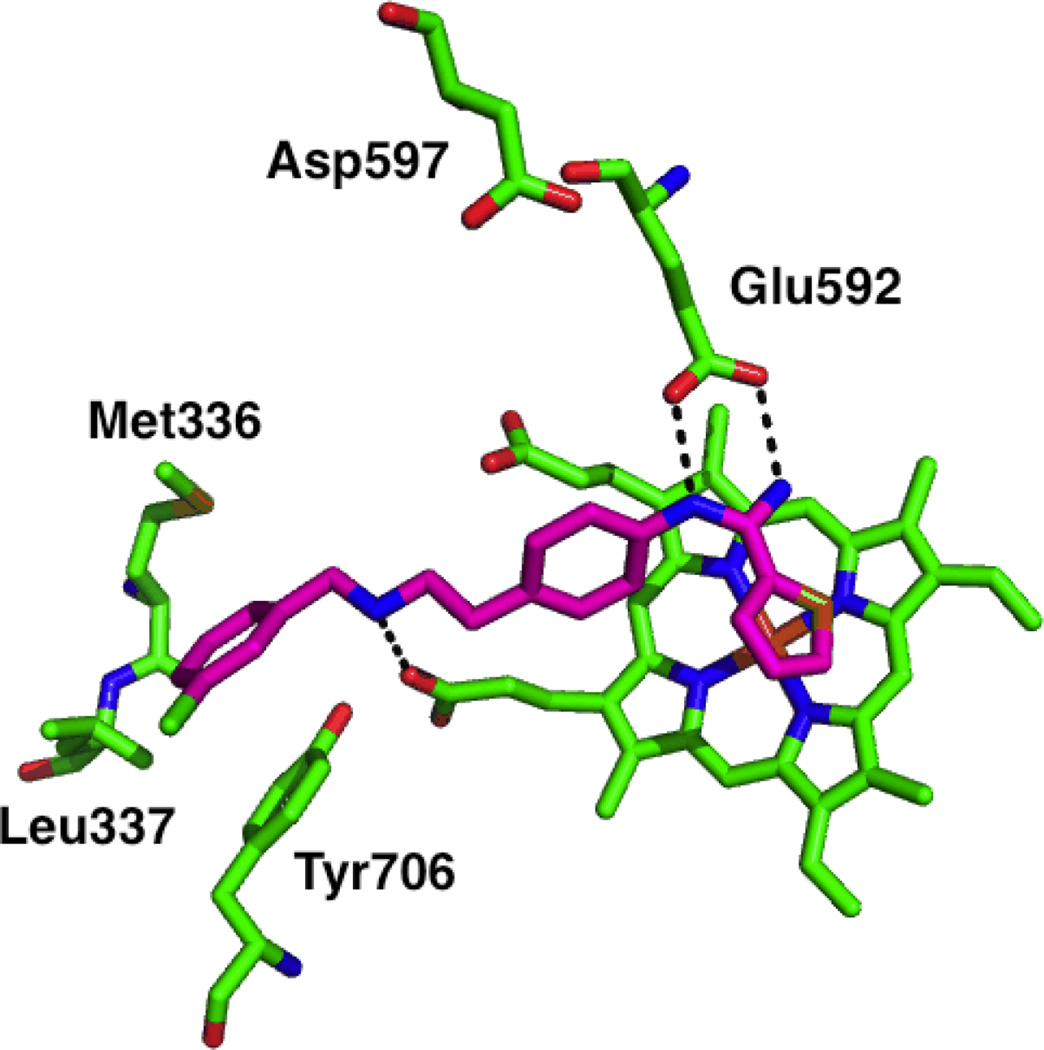

These “double-headed” compounds can effectively combine the “normal” and “flipped” binding modes previously observed for this class of compounds, where the aminopyridine groups can in some cases form strong ionic interactions with both theheme propionates and Glu592. Compound 20, for example, is a very potent nNOS inhibitor (Ki = 20 nM) but has lower isoform selectivity (107-fold over eNOS and 58-fold over iNOS) than 19. Interestingly, crystallography indicates that two molecules of inhibitor can bind to nNOS at once; one in the heme-binding site, and the other in the distal H4B-binding site, where it can displace H4B and coordinate to a newly-bound zinc atom126 in this pocket, thus making this compound effectively a novel type of dual arginine-H4B antagonist. The low isoform selectivity of 20 was improved via introduction of a cyano or aminomethyl group on the central aryl portion (21 and 22, respectively), both of which have interactions in their binding modes somehow mediated by Asp597 and subsequently higher nNOS/eNOS selectivity (472-fold for 21, and 221-fold for 22).127

Several other attempts were made to replace the chiral pyrrolidine fragment of leads such as 16 with simpler ether-linked aromatic groups, which, while considerably easier to synthesize, offered no advantages in terms of potency or selectivity.128 Double-headed aminopyridines containing chiral linkers (either acyclic129 or cyclic130), however, showed improved isoform selectivity relative to their achiral counterparts; compound 23, with a 9.7 nMKi against nNOS, showed the dual coordination of the heme propionate and Glu592 in nNOS crystal structures but not in eNOS, which is responsible for the 693-fold selectivity in favor of the former isoform.130

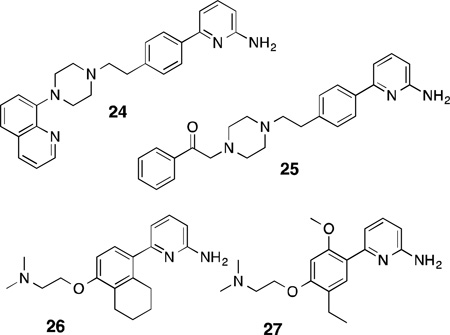

In addition to the efforts by the Silverman group, numerous simple aminopyridine-based inhibitors were also developed by Pfizer. From a library screening program, compound 24 was discovered,131 which is based on a 6-phenyl-2-aminopyridine core. Although it is a potent inhibitor of both rat and human nNOS (IC50 = 127 nM for rat, 140 nM for human), this compound is rather promiscuous and strongly binds several human dopamine and serotonin receptors, purportedly due to the arylpiperazine moiety. Structure-activity studies of 24 indicated that the introduction of an sp2-hybridized group distal to the piperazine ring decreased the off-target effects and increased nNOS/eNOS selectivity (in the case of 25). Although the isoform selectivity of this class of compounds was weak in general (around 6-fold in favor of nNOS over eNOS), subcutaneous administration of 25to rats resulted in only very weak cardiovascular side effects even at high doses. Introduction of electron-rich bicyclic groups on to the aryl portion linked to the aminopyridine and replacing the piperazine with a dimethylaminoethyl group132led to 26, which possessed better isoform selectivity (~49-fold over eNOS, 7-fold for iNOS) and showed inhibition of cGMP production in rat brains induced by the neurotoxin harmaline (median effective dose = 7 mg/kg when administered subcutaneously). Increasing the electron density of the central aryl portion by introduction of methoxyl groups133 further improved n/e selectivity (up to 220-fold for 27). Although several of these compounds were reported to have undergone in vivo pharmacokinetic profiling, further development of this particular aminopyridine class appears to have ceased ca. 2005. Higuchi and colleagues have incorporated 2-aminopyridines into amino acids as well.134 The resulting competitive inhibitors, however, were micromolar nNOS inhibitors that displayed weak selectivity for iNOS over nNOS; a similar trend (toward iNOS selectivity) was observed for aminopyridine-containing amino acids designed by AstraZeneca.135 As such, the majority of AstraZeneca’s more recent efforts were concentrated on the development of 2-aminopyridines substituted on the exocyclic nitrogen as selective iNOS inhibitors.136

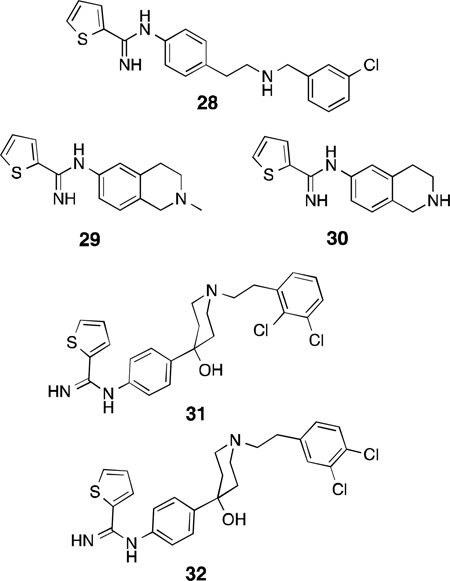

Other Competitive Arginine Mimetics: Aromatic and Cyclic Amidines

Continuing in the vein of amidine and guanidine-containing compounds and isosteres, AstraZeneca reported AR-R17477137 (28), a thiophene-2-carboximidamido compound, as an early lead for nNOS inhibitor development in 2000. This potent inhibitor (IC50 = 35 nM), while having only modest selectivity over iNOS and eNOS (143 and 100-fold, respectively), shows exceptionally long-lasting nNOS inhibition in rats (50% inhibition of cerebellar nNOS 24 h after a single dose as determined by ex vivo analysis). Compound 28 reduced infarct volume by 55% seven days after ischemia in a transient focal model of stroke in rats138 and significantly reduced neuronal death 72 h after introducing ischemia in dogs via hypothermic circulatory arrest.139 Another compound, AR-R18512 (29), showed a similar neuroprotective profile in rats; significant ischemia reduction was observed following administration of 3 mg/kg via intravenous infusion, while a third lead, AR-R17338 (30), demonstrated near 100% oral bioavailability in monkeys.137The crystal structure of the lead (28)140 indicates that the thiophene-amidine group, like the 2-aminopyridine moiety, behaves as an arginine isostere and binds to Glu592, while the secondary amine hydrogen-bonds with a heme propionate, and the chlorophenyl-containing tail projects toward the hydrophobic pocket of the substrate access channel (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

X-ray crystallographic binding mode of 28 in rat nNOS active site (PDB 1VAG). Polar interactions are shown as dashed lines.

Similar thiophenecarboximidamide inhibitors containing hydroxypiperidine moieties were designed by Sanofi-Aventis with hopes of developing different SARs between nNOS and eNOS. As observed in pyrrolidinomethyl-2-aminopyridines, the introduction of chloroaryl groups (indicated by docking studies to reach toward the nNOS-selective hydrophobic pocket, which Sanofi-Aventis describes as the “selectivity modulating region”) greatly enhanced potency and selectivity – 31 has an IC50 of 129 nM, while the most potent compound, 32, has an IC50 of 17 nM against nNOS and 1664-fold selectivity over eNOS. Unfortunately, 32 is metabolically labile, 32% of which is metabolized by human liver microsomes in 20 minutes.141

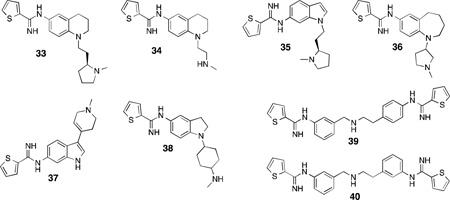

The majority of recent (2007–2012) developments of the thiophenecarboximidamide inhibitors were performed by NeurAxon, Inc. Like the core structure of 29 and 30, the majority of NeurAxon’s inhibitors share similar pharmacophores: a thiophene amidine group, a central rigid linker portion (dihydroquinolones,142 tetrahydroquinolines,142,143 aminobenzothiazoles,144 benz-azepines,145 and various disubstituted indoles146,147,148,149 and indolines150,151 have all been employed), and a short-tailed amine-containing group (such as dimethylaminoethyl or pyrrolidinoethyl). The extensive refinement of several leads produced readily synthesized, potent, and selective nNOS inhibitors having very promising activity in a variety of rodent pain models, as well as excellent bioavailability and safety profiles. For example, compound 33142 reduced pain in the Chung spinal ligation model of neuropathic pain, where ligation of the L5/L6 spinal nerves produces hyperalgesia and thermal and mechanical allodynia152 in rats, and thermal hyperalgesia was reversed entirely by administration of 33 (30 mg/kg).In a rat model of migraine (induced by dural stimulation),33 also alleviated the development of allodynia. Although this compound was efficacious, isoform selective, and also displayed little to no inhibition when assayed against a panel of cytochrome enzymes, it suffered from low oral bioavailability and modest hERG(human Ether-à-go-go Related Gene) channel inhibition, which halted its development. This compound was optimized to produce 34,143 which resulted in lower hERG inhibition and a 40% increase in oral bioavailability, while still displaying activity in the Chung pain model and having no inhibitory activity against five major human cytochromes. Several other compounds in this class displayed interesting physiological effects. Compound 35 was effective in rodent neuropathic pain models following oral administration,148 the benzazepine36 has very high n/i selectivity (>800-fold),145 and while 37 has low n/e selectivity, it showed no inhibition of acetylcholine-mediated relaxation in isolated human coronary arteries, lowering the probability of adverse cardiovascular events in vivo.147 Indoline38 is a very promising candidate, which showed 66% reversal of allodynia in the Chung model, along with no hERG-related complications or off-target effects when assayed against a panel of 80 clinically relevant CNS targets.151 Despite the in vivo successes of the NeurAxon thiophenecarboximidamides, there is no published information on the nature of their binding modes to nNOS. Another study from Northwestern153 attempted to apply the “double-headed” strategy previously utilized for aminopyridines to thiophenecarboxamides, leading to two highly potent and selective inhibitors, 39, and 40; both having >200-foldselectivity for nNOS over both other isoforms.

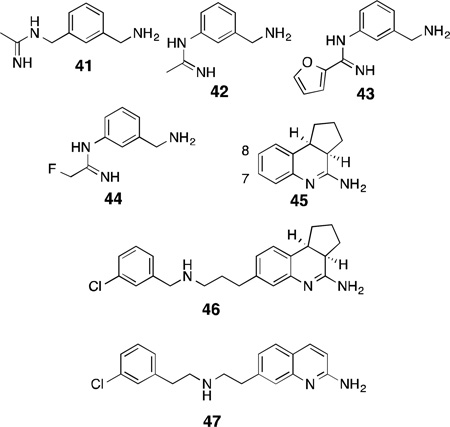

Although 2-aminopyridines and thiophenecarbox-imidamides are the two most thoroughly investigated classes of non-arginine competitive inhibitors, several other classes of amidines, both cyclic and acyclic, have found utility as NOS inhibitors. In an early study by GlaxoWellcome, the potent acetamidine-based iNOS inhibitor 1400W (41)154 was converted into the nNOS-selective compound, 42, by removal of a methylene group. Further structure-activity studies yielded 43 and 44.155 These compounds are very potent but only modestly selective over the other NOS isoforms (100-fold for nNOS over eNOS was the maximum achieved n/e selectivity for 44).Nonetheless, 44 displayed excellent brain penetration and inhibited nNOS in both rat brain slices and rat cerebellum in vivo. The compact “phenylamidine” SAR for nNOS inhibition also holds in the design of phenylisothioureas, which, as a class, have largely similar isoform selectivities as the substituted phenylamidines.156 In the work of Hamley and colleagues, thienopyridines (which essentially are conformationally restrained thiophenecarboximidamides) were indicated as very potent NOS inhibitors, yet show little ability to differentiate between nNOS and iNOS.157

Similarly, tricyclic amidine derivatives based on a dihydroaminoquinoline scaffold (45)158,159 were discovered in a high-throughput screen. Augmenting this simple, weakly selective tricyclic core with tails containing secondary amines and halophenyl groups (such as that found in 46)160 enhanced the potency and selectivity for nNOS (IC50 of 42 nM), an observation consistent with the SARs of both pyrrolidinomethyl-2-aminopyridines and Sanofi’sthiopheneamidines (31 and 32). Additionally, it was found that the halophenyl-containing tails could only be successfully incorporated at position 7 of the dihydroaminoquinoline; this SAR trend is also observed in similar 2-aminoquinoline-based inhibitors,161 where incorporation of bulky substituents at positions other than 7 results in a complete loss of nNOS inhibition, likely due to steric clashes with bulky residues in the heme-binding site. The aminoquinoline-based inhibitor 47, in addition to >100-fold selectivity over both isoforms, is highly membrane permeable in a Caco-2 assay, which is used to approximate both gut and brain membrane permeation.162,163

Competitive Inhibition Through Heme-Fe Coordination

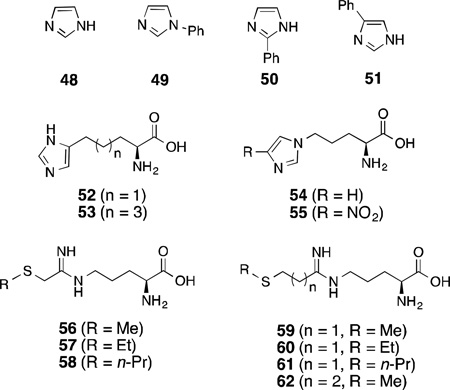

In addition to arginine isosteres, another approach to developing competitive substrate inhibitors of nNOS, albeit less explored, is to coordinate the heme iron (Fe) of the active site of NOS. Since, NOS belongs to the cytochrome P450 class of enzymes and, therefore, contains a heme Fe, ligands like imidazoles that are known to coordinate to the heme Fe might also out compete l-arginine to bind in the active site. Indeed, imidazole (48) is a weak inhibitor of bovine nNOS (IC50 = 200 µM).164 The potency of imidazole dramatically improves with a phenyl substituent at 1-position (49;IC50 = 25 µM) compared to much less potent 2- (50; IC50 = 100 µM) or 4-phenylimidazole (51; IC50 = 600 µM).165 This difference could result from either steric hindrance or more effective depletion of electron density from the imidazole ring by 4-phenyl substitution, which weakens Fe-N binding.

Numerous amino acid derivatives with an incorporated imidazole have been designed to competitively inhibit nNOS.166 The length of the linker between the imidazole and carboxylic acid was varied to optimize the potency and selectivity. Two of these compounds, 52 and 53, with three and five methylene units, respectively, between imidazole and the amino acid were found to be most effective and selective for nNOS over iNOS as well as eNOS. This SAR overlapped with another study, where compounds 54 (IC50 = 19 µM) and 55 (IC50 = 178 µM) were shown to be better inhibitors, with the same effective linker length between the imidazole and amino acid part.167 Replacement of the imidazole by a triazole or tetrazole ring showed weaker inhibition.

Potential heme-coordinating nNOS inhibitors were designed on the basis of computer modeling of the active site of nNOS, using amidine analogues with a heme-ligating side-chain.168 Of the 10 different amidines that were tested with different Fe-coordinating groups (thioethers, thiols, amines, imidazoles, thiazole, and thiophene), compound 56 revealed the maximum potency (Ki = 0.37 µM) and 185-fold selectivity over eNOS.

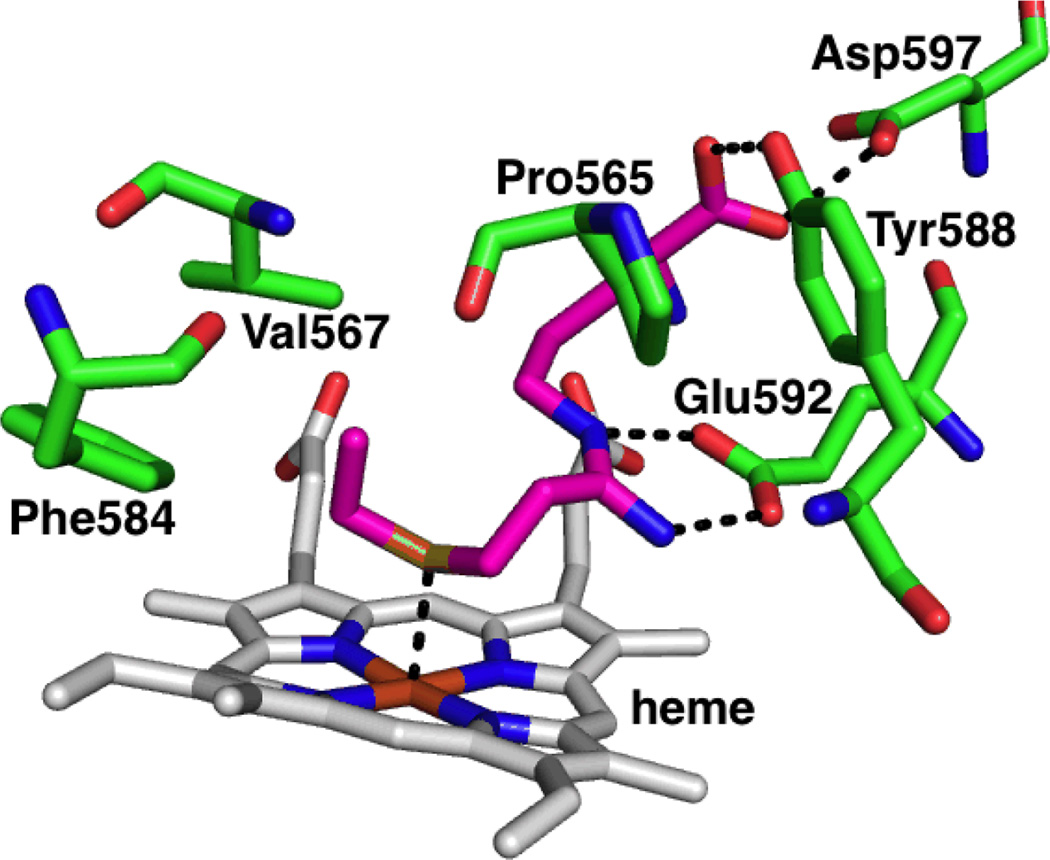

In 2009, the first crystal structures of nNOS inhibitors showing Fe-thioether coordination were reported.169Using a similar principle as above (attaching an Fe-coordinating group to the substrate) a series of type II (heme-coordinating) inhibitors were designed based onl-arginine to enable these compounds to anchor in the substrate site with anamidine head. The length of the alkyl group on the thioether as well as the number of methylene units between the amidine and S were varied to find the optimal linker to position the thioether over the heme. From this series, compound 60 showed nNOS inhibition (Ki = 33±2 µM) and its crystal structure (Figure 9) revealed type II inhibition with an Fe-S distance of 2.5 Å; the two methylene unit linker between the amidine and S was flexible enough to orient the S towards Fe with the ethyl group situated in a hydrophobic pocket lined by Pro565, Val567 and Phe584, which provides additional stability. Unexpectedly, the coordination to the heme Fe showed no effect on the potency of the molecule, as 62 had a similar potency to60, and 56 is more potent than 60, but all compounds except 60 were type I (non-heme-coordinating) inhibitors. Also, compounds 57, 58, and 61reverted to type II on heme reduction from ferric (Fe3+) to ferrous (Fe2+)indicating a higher affinity of thioethers for Fe2+ than Fe3+. The isoform selectivity of these compounds was not explored.

Figure 9.

X-ray crystallographic binding mode of compound 60 showing Fe-S coordination (PDB 3JT4). Polar interactions are shown by dashed lines.

H4B Antagonists

In addition to the crucial role of H4B as an electron donor and a redox partner in the oxidation of l-arginine, as discussed earlier, it also plays a significant role in stabilizing the active homodimers,48,170 allosterically enhancing the binding of the substrate l-arginine to the enzyme,171,172 and preventing product inhibition of the enzyme.173 Therefore, the H4B binding site has also been targeted for the development of NOS inhibitors.

Dual Substrate and H4B Antagonists

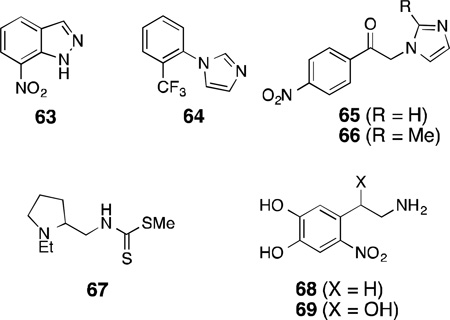

Of the early inhibitors of NOS, 7-nitroindazole [7-NI(63)] is one of the most-studied non-arginine based inhibitors because it shows high in vivo selectivity for the neuronal isoform (intraperitoneal or intravenous administration did not affect mean arterial blood pressure in mice and rats),174,175,176 although it shows little isoform selectivity in vitro [IC50 = 0.47 µM (rat nNOS); 91±16.6 µM (murine iNOS); 0.7±0.2µM (bovine eNOS)].174,177,178 In the early 1990s, investigation into the mechanism of enzyme inhibition by 63revealed that in the purified bovine nNOS assay with radiolabelled H4B, 63 antagonized H4B-binding with a Ki of 0.12 µM.178 Although it showed competitive inhibition for both l-arginine and H4B for nNOS, it was a competitive inhibitor only for H4B in iNOS and eNOS. Because of its selective mechanism of action, antinociceptive (inhibition of sensation of pain) properties, delay of spinal motor neuron degeneration in the wobbler mouse,44and efficacy in rats in reducing infarct volume by 25–27% following cerebral ischemia, several other substituted indazoles were tested; however they did not exhibit much improvement over 7-NI.175,177,179 Furthermore, substituted 7-NIs such as 3-bromo-7-nitroindazole and 2,7-dinitroindazole showed similar or improved potency as the parent compound 7-NI, indicating that 7-nitro substitution is crucial for the potency of these inhibitors.176

Another type of imidazole-based inhibitor, 1-(2-trifluoromethylphenyl)imidazole [TRIM (64)], that displayed antinociceptive effect in vivo and also selectivity against eNOS in vitro [IC50 = 28.2 µM (mouse nNOS); 27 µM (rat iNOS); 1057.5 µM (bovine eNOS)], shows competitive inhibition both for l-arginine and H4B binding.180 Although 64 was less potent in the in vitro assays, 63 and 64displayed similar pharmacokinetic profiles in vivo. Two other N-phenacyl imidazoles (65 and 66) showed H4B dependence in their inhibitory effect on nNOS but no competitive inhibition with l-arginine.181 In addition to nNOS inhibition with some selectivity over iNOS and eNOS, 65 and 66 were later shown to possess effective antioxidant activity and, therefore, were proposed as important therapeutic scaffolds for future development since they target both nNOS and quench ROS (similar dual inhibitors are discussed in detail in a later section).182

An N-(tertiary aminoalkyl)dithiocarbamic ester (67) was reported to be a substrate inhibitor of nNOS with some dependence on H4B [% inhibition (+H4B): 59; (-H4B): 21].183 It was speculated that the mode of interaction could be through Fe-S coordination from the thiocarbamate and some secondary interaction with the H4B, but it was inconclusive because of a lack of additional data.

6-Nitrodopamine (68) and 6-nitronorepinephrine (69), catecholamine metabolites produced under conditions of oxidative stress were also shown to be inhibitors of nNOS (Ki = 45 µM and 52 µM, respectively) with some selectivity over the other isoforms.184 These compounds displayed antagonizing properties toward H4B. Interestingly, it was shown that the H4B-antagonizing property of these compounds arose from the aminoethyl side-chain, as 4-nitrocatechol showed only competitive inhibition withl-arginine with no H4B antagonism at concentrations up to 10 µM of H4B.185 In addition, the crucial effect of the electronics that the nitro group imparted on the inhibitory effect of 7-NI was also observed with 6-nitro substitution in the case of 6-nitrodopamine.

Exclusive H4B Antagonists

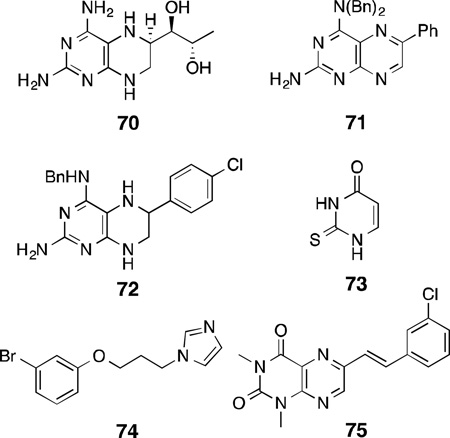

Pterin analogues have been designed since 1996 to exclusively target the H4B binding site as a method to develop NOS inhibitors. The 4-amino analog of H4B, 70, was an H4B antagonist with high potency for rat nNOS (IC50 = 1 µM, Ki = 13.2 nM; rat nNOS).186 Compound70 also acts as an inhibitor of a dihydropteridine reductase enzyme (IC50 = 20 µM). Further SAR studies on 70 revealed that chemical modifications of the 4-amino group by dialkylation along with arylation at the 6-position of the 2,4-diaminopteridine provides a selective inhibitor of nNOS(71, IC50 = 3µM; porcine nNOS).187 It was speculated that the increased hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions of the 4-, 5-, and 6-substituents of the pterin molecule with the H4B binding pocket residues give rise to potency and selectivity through selective insertion and binding. These aforementioned SARs were also mirrored in the potency and selectivity against human nNOS.188,189 With the use of a combination of ligand- and structure-based design, 72 was identified, which inhibited human nNOS(IC50 = 3.68 µM) and showed moderate isoform selectivity (n/i = 58.2, n/e = 8.62).188 Docking of 72 into a human nNOS homology model (on the basis of the crystal structure of rat nNOS oxygenase domain) supported the SAR results.

2-Thiouracil (73), a known antithyroid drug, was speculated to bind to the H4B-binding site of nNOS because of its structural resemblance to the pyrimidine core of H4B. Indeed, 73 showed selective inhibition of nNOS with a Ki of 20 µM.190 However, unlike H4B, 73is redox-stable and, therefore, cannot participate in the turnover of l-arginine to l-citrulline and NO, and does not stabilize dimerization of nNOS.

Other imidazole derivatives were shown to be selective nNOS inhibitors that compete for the H4B-binding site, but showed no heme-Fe coordination despite the presence of an imidazole ring. Compound 74 showed rat nNOS inhibition (Ki = 32 µM) with 20-fold selectivity over eNOS.191 It was observed that increasing the size of the linker between the imidazole and the phenyl ring increased potency for nNOS but compromised isoform selectivity.

Since monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) and NOS are both implicated in the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases, and a structural resemblance exists between reversible inhibitors of MAO-B and H4B, compounds such as75 were designed as dual inhibitors of MAO-B and nNOS.192 However, although these pteridine-2,4-dione analogues showed potency as reversible MAO-B inhibitors (75, IC50 = 0.314 µM), they were poor nNOS inhibitors (75,IC50 = 1057µM).

Calmodulin Antagonists

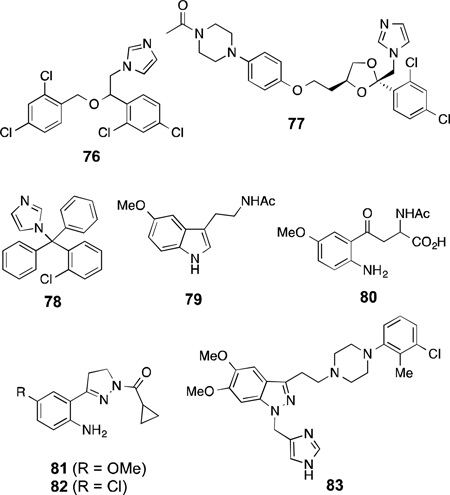

Like inhibitors that bind at the active site of NOS and additionally interact with H4B, imidazole-based inhibitors are known that bind competitively at heme and also interact with the calmodulin (CaM) binding site. Miconazole (76), ketoconazole (77), and clotrimazole(78) are imidazole-containing antifungal agents that showed competitive inhibition of l-citrulline formation in bovine nNOS with Ki values of 7, 44, and 19µM respectively, while they also showed calmodulin-dependent competitive inhibition of cytochromec reductase activity of nNOS.193 Although these compounds show selectivity over iNOS, there was no selectivity between nNOS and eNOS.194

Melatonin (79) and kynurenine derivatives are metabolites of tryptophan in the brain and possess neuroprotective properties.195,196 Melatonin exhibits Ca2+-dependent rat nNOS inhibition with an IC50 of 0.1 µM. Additionally, a significant inhibition of rat nNOS (>22%) was observed at 1 nM melatonin concentration, which is its physiological serum concentration at night.196 Melatonin and these synthetic kynurenine derivatives modulate the excitatory response of NMDA-receptors in rat striatal neurons, an effect that is related downstream to nNOS inhibition.197,198 SAR studies on a series of synthetic kynurenines revealed that an amino substitution on the benzene ring is crucial and provided maximal nNOS inhibitory activity in the series (80,IC50 = 40.9 µM).199,200 The inhibitory effects of melatonin and amino-kynurenines were shown in kinetic studies to be dependent on CaM concentration, which suggests that CaM may be involved in the intracellular neuroprotective effect.199

Another study revealed that pyrazole derivatives (81 and 82),201 designed as rigid kynurenine analogues, showed 62 and 70% nNOS inhibition respectively at 1 mM concentration. These compounds, like the amino-kynurenines, have a crucial intramolecular H-bond between the aniline group and the pyrazole N, and show greater potency than compounds that lack this interaction. The pyrazole derivatives and the synthetic amino-kynurenines, with their intramolecular H-bonding, mimic the active site conformation of melatonin (79) when it binds to nNOS and imparts its inhibitory effect.

DY-9706e (83) is a novel CaM antagonist that shows strong neuroprotective effects in transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats.202,203,204 Studies performed on83to understand its effect revealed that it inhibits both nNOS and, to some extent eNOS, but not iNOS, and the potency of inhibition of nNOS in vitro (Ki = 0.9 µM) is similar to that for other CaM-dependent enzymes like CaM kinase II and calcineurin (Ki = 1.2 and 2 µM, respectively) but stronger than for CaM kinase IV and myosin light chain kinase (Ki = 12 and 133 µM, respectively).205,206 Furthermore, 83inhibited Ca2+ ionophore (A23187)-induced NO production in mouse neuroblastoma cells at a concentration of 1 µM; however, it showed no inhibitory effect on Ca2+/CaM dependent kinase II activity in cultured hippocampal neurons at concentrations up to 5 µM. It was also shown that post-ischemic treatment with 83inhibits nNOS in gerbil hippocampus without any effect on CaM kinase II and calcineurin.207 Taken together, these data suggest that the neuroprotective effect of 83, presumably, results from its CaM-dependent NOS inhibition. In addition, 83 reduced brain edema formation through the inhibition of nNOS after transient focal ischemia in rats.208

Inactivators of nNOS

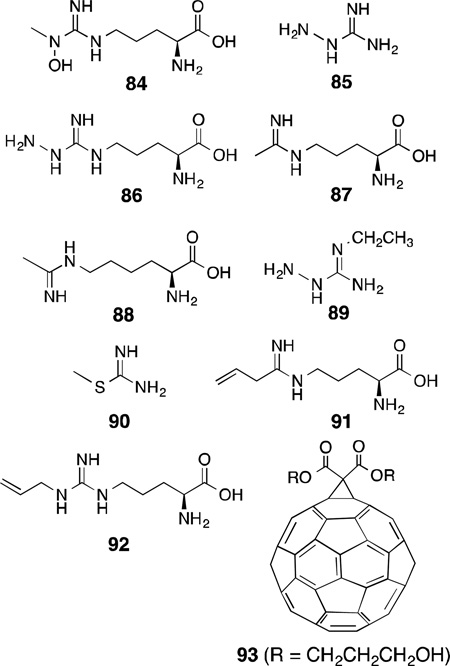

Because of the wide occurrence and essential role of heme in different enzymes, such as NOS, cytochrome P450, and heme oxygenase, an understanding of the mechanisms of heme-dependent reactions in enzymes has attracted much attention. Several inactivators of nNOS have been reported over the years, where inactivation of the enzyme generally takes place through covalent modifications of the heme by the compound. In 1993, Feldman and co-workers reported l-NMA (3), an established mechanism-based inactivator of iNOS, to also irreversibly inhibit nNOS in addition to being a reversible competitive inhibitor.209 Compound 3 was shown to undergo regiospecific hydroxylation, like that in the first-step of l-arginine oxidation, to form l-NG-hydroxy-NG-methylarginine [l-NOHNMA(84)], and authentic l-NOHNMA irreversibly inhibited both iNOS and nNOS, suggesting this oxidation of NMA (3) is related to the mechanism of NOS inactivation. Compound 3 has exhibited therapeutic effects related to NOS inhibition in animal models; however, its lack of isoform selectivity limits its utility.210,211

In 1995, aminoguanidine (85) was also shown to be an inactivator of all of the NOS isoforms.212 Inactivation of nNOS and eNOS required the concurrent presence of Ca2+, CaM, NADPH, H4B, and oxygen, and activity of NOS was not regained. This suggested that 85 was a mechanism-based inactivator of NOS. Later in 1999, Wolff and co-workers demonstrated that inactivation of nNOS by 85, l-NG-aminoarginine [l-NAA (86)], l-N5-(1-iminoethyl)ornithine [l-NIO (87)], and l-N6-(1-iminoethyl)lysine (88) occurred through degradation of the heme as evidenced by the time- and concentration-dependent loss of heme fluorescence.213 Only up to 60% heme loss was observed, and this was sufficient for complete inactivation. Along this line, it was found that inactivation by 86 results from covalent modification of the heme prosthetic group to products that contain an intact porphyrin ring either dissociable or irreversibly bound to a residue in the oxygenase domain of nNOS.214 Mass spectral analysis showed an m/z of 775.3,which is consistent with a heme-NAA adduct minus a hydrazine unit.214 Similar observations of covalent adducts were reported for inactivation by aminoguanidine and diaminoguanidine.215,216

Among a series of other substituted aminoguanidines and aminoisothioureas that showed time- and concentration-dependent inactivation of the NOS isoforms, 2-ethylaminoguanidine (89) was the most efficient inactivator and showed isoform selectivity towards iNOS (iNOS: KI= 0.12 mM, kinact = 0.48 min−1; nNOS: KI= 1mM, kinact = 0.46 min−1).217 In contrast, 1-amino-S-methylisothiourea (90) was a mechanism-based selective inactivator only for nNOS (iNOS: KI= 1.1 mM, kinact = 0.75 min−1; nNOS: KI= 0.3 mM, kinact = 0.73 min−1).

Like l-NIO (87), l-VNIO [N5-(1-imino-3-butenyl)-l-ornithine, 91), was shown to be a potent mechanism-based inactivator of nNOS (KI= 90 nM, kinact = 0.078 min−1). Interestingly, 91 is not an inactivator of iNOS, and for eNOS it requires 20-fold higher concentration to match 75% of the rate of inactivation of nNOS.93,218

Among other arginine-based inactivators of NOS, Nω-allyl-l-arginine (92) was both a competitive reversible inhibitor and a time-dependent inactivator of bovine nNOS (Ki = 200 nM, KI = 470 nM, kinact = 0.05 min−1, at 0 ºC).86 It was shown through multiple techniques that in the process of inactivation, the heme was modified to four different species, and only the allyl part of the inactivator was bound to heme. Nω-Propyl-l-arginine (4), in addition to being a competitive inhibitor, also was a time-dependent inactivator of nNOS, suggesting that the double bond of the allyl group in 92 is not crucial to the inactivation mechanism (Ki = 57 nM, KI= 19.8 nM, kinact = 0.0059 min−1, at 0 ºC).85

6-n-Propyl-2-thiouracil, an antithyroid agent, is also a mechanism-based inactivator of nNOS.219 Interestingly, a C60-fullerene adduct, a di(carboxypropan-3-ol)methano-[60]-fullerene [diol adduct (93)], showed time-, concentration-, and turnover-dependent inactivation of nNOS with a much higher selectivity for nNOS over eNOS or iNOS.220 The inactivation of nNOS was completely prevented by the presence of superoxide dismutase or catalase, and excess consumption of NADPH was observed in presence of l-arginine in this inactivation process. These observations indicate that the fullerene adducts cause nNOS to produce peroxides and superoxides in high concentrations that inactivate the enzyme.

Dimerization Inhibitors of nNOS/iNOS

Among the three isoforms of NOS, iNOS and nNOS are closely associated with inflammation and pain. Production of NO by iNOS also takes place under pathological conditions of neuropathic pain and inflammation as observed in neuropathic pain models in rats.221 It was observed that peripheral nerve injury associated with local inflammation caused by the expression of iNOS can lead to neuropathic pain. Additionally, the link between nNOS, neurodegeneration, and neuropathic pain indicates selective dual inhibitors of nNOS and iNOS over eNOS could be important therapeutic candidates.

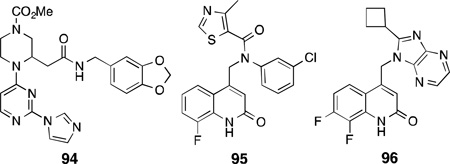

Apart from targeting the active site of NOS enzymes, inhibition of dimerization as a mechanism for NOS inhibition has also shown great promise since all NOS isoforms are active only in their homodimeric form. This has mainly been investigated for iNOS inhibitors.222,223 A potent imidazole-containing dimerization inhibitor of iNOS, BBS-1 (94), was identified from a combinatorial library screen and showed high potency for iNOS (IC50 = 28 µM), lower selectivity for nNOS than eNOS (i/n = 5, i/e = 1000), and was also shown to interfere with the dimerization of nNOS.224Compound94inhibited nNOS activity reversibly by inhibiting nNOS dimerization in DLD-1 cells (IC50 = 40 ± 10 µM) infected with a recombinant adenovirus containing the cDNA of human nNOS. Compound 94 was also effective as an iNOS inhibitor in vivo as intraperitoneal administration of 94to rats showed dose-dependent reduction of plasma nitrate concentration after induction of iNOS activity.225

In another class of dimerization inhibitors for iNOS, Smith and co-workers reported a series of quinolinone amides that were potent, with high selectivity over eNOS, and were also orally active in rodent pain models [e.g., 95, human iNOS, EC50 = 0.011 µM; i/n = 210; i/e = 2300].223 However, in vivo studies showed high clearance and short half-life in mice; therefore, further pharmacophore modifications were attempted. Toward this end, replacing the amide functionality from the previous compounds, and restraining the conformational flexibility by introducing abenzimidazole-quinolinone type motif, gave rise to a class of dual iNOS/nNOS dimerization inhibitors.226 A 4,7-imidazopyridine, KLYP961 (96), showed high potency for both iNOS and nNOS(EC50 = 0.091 µM, i/n = 3), good selectivity over eNOS (i/e = 180), and high liver microsomal stability. Compound 96 showed efficacy in a number of pain/inflammation models both in mice and nonhuman primates, showed high selectivity against off-target receptors and channels, and its desirable pharmacokinetic profile made it a good clinical candidate.227

Dual Inhibitors of nNOS and Other Targets

With advancement in the understanding of molecular mechanisms of action, there has been a focus toward the development of drugs that act specifically on multiple targets to improve the efficacy and safety of drugs through additive or synergistic effects.228For example, NO and ROS can act cooperatively and causelipid peroxidation.20 As a result, inhibition of neuronal NOS and inhibition of lipid peroxidation by the ROS has been shown to act synergistically to prevent neuronal damage.20, 229

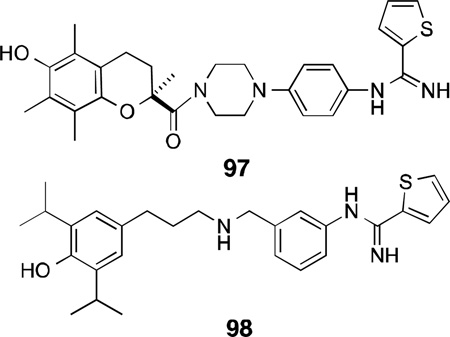

A class of dual nNOS inhibitors such as BN 80933 (97) with the thiophenecarboximidamide head (nNOSinhibitor pharmacophore) connected with a linker to an antioxidant moiety (Trolox derivative) reduced brain damage induced by focal ischemia in rats. Compound 97 displayed selective inhibition of nNOS (Ki = 0.92 µM) over eNOS (n/e = 120) and iNOS (n/i >326), and more potent antioxidant property (IC50 = 0.29 µM) than its parent compound Trolox (IC50 = 39.4 µM).229

Treatment with 97 (0.3–10 mg/kg) in a middle cerebral artery occlusion model showed 62% neuroprotection and enhanced behavioral recovery in rats. Further SAR studies on each of the NOS pharmacophoreand antioxidant subunits as well as the size of the linker led to a more potent nNOS inhibitor 98 (for nNOS, Ki = 0.12 µM, n/e = 67.6, n/i >150) with similar inhibitory potency for lipid peroxidation (IC50 = 0.4 µM).230

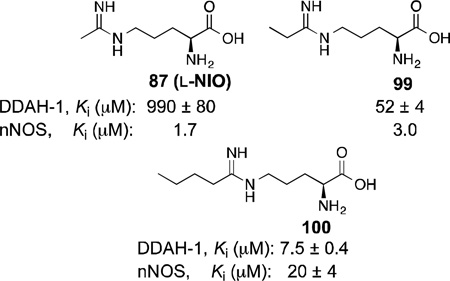

In 2009, Fast and co-workers reported dual-target inhibitors of nNOS and dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH-1).231 DDAH-1 acts as a regulatory enzyme to NOS by controlling the concentrations of Nω-methyl-l-arginine (3) and Nω, Nω-dimethyl-l-arginine, which are endogenous substrate inhibitors of NOS. Known nNOS inhibitor scaffolds were modified into DDAH-1 inhibitors, but these compounds lacked any selectivity for the other NOS isoforms. A series of alkyl amidines with varying alkyl length were tested and compounds with medium chain length (87, 99,and 100) were able to show activity against both nNOS and DDAH-1.

Opioid analgesics have been long-used for pain management, and nNOS inhibitors have shown promise for treating neuropathic pain. Furthermore, it has been reported that nNOS inhibitors are capable of altering morphine-induced hyperanalgesic effects when administered in rats.232Therefore, a dual-action inhibitor was designed by targeting two distinct classes of proteins, the G-protein coupled receptors (µ-opioid receptors in particular) and NOSs.

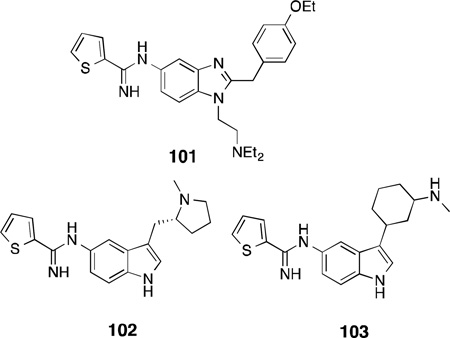

By combining the thiopheneamidine head with the pharmacophore of the potent benzimidazole opioid, etonitazene, a class of benzimidazole ligands was designed that shows potency for both nNOS and µ-opioid receptors, with selectivity for nNOS over eNOS and iNOS.233With the aid o fSAR studies, compound 101 was identified, which had good nNOS potency (IC50 = 0.44 µM), moderate selectivity over its isoforms (n/e = 10, n/i = 125), and high µ-opioid agonist activity (Ki = 5.4 µM).

It has been reported that increased levels of serotonin by selective serotonin [5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] reuptake inhibitors provides an inhibitory effect on nNOS activity.234,235As both pathways are implicated in migraine headaches, compounds with both selective nNOS inhibition and 5-HT1B/1Dreceptor agonist activity were designed. Compound 102 inhibits human nNOS with an IC50of 0.81µM, 41-fold selectivity over eNOS, and has agonist activity towards both 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors [5-HT1B (rat cerebral cortex, IC50 = 0.13 µM); 5-HT1D (bovine caudate, IC50 = 0.31 µM)].236 NXN-188, which is currently in Phase II clinical trials for the acute treatment of migraine headache, also exhibited dual inhibition as a competitive substrate inhibitor of nNOS and a 5-HT1B/1Dreceptor agonist.237,238,239However, the structure of NXN-188 has not been published.

In another dual approach, because low norepinephrine and high NO are both associated with neuropathic pain, Mladenova and co-workers proposed an nNOS-selective inhibitor with norepinephrine reuptake inhibitory activity.240 Using pharmacophores known to inhibit the norepinephrine transporter (NET) and nNOS, successive SAR studies identified lead compound cis-102, with inhibitory activity for nNOS (IC50 = 0.56 µM) and NET (IC50 = 1 µM), and moderate selectivity over eNOS and iNOS (n/e = 88, n/i = 12). Intraperitoneal administration of 103 in a rat spinal nerve ligation model caused reversal of thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia. Furthermore, 103did not affect vasoconstriction or acetylcholine-mediated vasodilation in human coronary arteries(indicating selectivity against eNOS),and showed no off-target activity against 80 receptors.

Is iNOS Implicated in Neurodegenerative Disorders?

Along with nNOS, iNOS has been associated with numerous inflammatory diseases such as multiple sclerosis, septic shock, rheumatoid- and osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma.241 Furthermore, iNOS has also been implicated, under certain conditions, in neurodegeneration and neuro inflammation.242 Evidence for the involvement of iNOS under conditions of ischemic brain damage has been reported in mouse models, where mice that are deficient in iNOS are less vulnerable to cerebral ischemia.243 Expression of iNOS in rats was increased during the 12 hours following ischemia, showing inhibition of iNOS could be beneficial. Also, aminoguanidines, which are inactivators of iNOS, were neuroprotective in rat models of middle cerebral artery occlusion.244

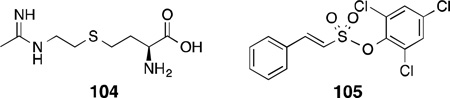

Similar to nNOS inhibitors that have been developed for the treatment of migraine headache, GW274150 (104) is a potent and selective iNOS inhibitor that is in Phase II clinical trials for the treatment of migraine headache and asthma. Compound 104 was obtained from SAR studies on hetero-substituted analogues and homologues of acetamidine derivatives of l-lysine(an established iNOS inhibitor).245 Compound 104 showed modest potency for iNOS (IC50 = 1.4 µM) with good selectivity over both eNOS and nNOS (i/e = 333, i/n = 104).

Because of the implication of iNOS in many pathological conditions, considerable effort has been given over the years to develop potent and selective iNOS inhibitors from arginine mimetics to more druglike compounds. However, it is beyond the scope of this review to discuss iNOS inhibitors in general.246 The following, however, describes where iNOS inhibitors have shown promise as neuroprotective agents.

Thiazolidinediones are synthetic agonists of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), which plays an important role in neuroprotection and neuroinflammation.247 Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are thiazolidinediones that are FDA-approved drugs for the treatment of Type II diabetes and also impart protection against neuronal damage, motor dysfunction, myelin loss, and neuropathic pain in a rat spinal cord injury model.247,248 Furthermore, PPARγ agonists also prevent neuronal death and inflammation as an after effect of focal cerebral ischemia in rodents.249 Overproduction of NO by iNOS is implicated in inflammation, while PPARγ agonists attenuate inflammatory effects. Therefore, a dual action inhibitor of iNOS and an agonist of PPARγ might be useful as a therapeutic agent. A series of 2-phenyl-ethenesulfonic acid phenyl esters such as 105 inhibited NO production in cells induced to express iNOS with an IC50 of 1.8 µM.250 In addition, 105 showed competitive binding and PPARγ transactivation activity in cells transfected with PPARγ ligand binding domain plasmid with an IC50 of 1.4 µM and 61% transactivation activity. Compound 105 was the most potent compound for both iNOS inhibition and PPARγ activation.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

With the availability of crystal structures of all three isoforms of NOS and numerous animal models of neurodegeneration and pain, some initial hurdles (potency, efficacy, selectivity, and bioavailability) in developing selective inhibitors of nNOS have been addressed. For example, in the pyrrolidine-based aminopyridine scaffolds, very potent and isoform-selective nNOS inhibitors with clear binding modes and mechanisms of action were obtained, although many of these compounds suffered from poor BBB permeation and pharmacokinetic properties. On the other hand, thiophenecarboximidamide-based inhibitors showed improved in vivo pharmacokinetic profiles and higher bioavailability with moderate to good isoform selectivity, although little is known about their binding mode within the enzyme. Nonetheless, all of these efforts taken together have recently resulted in more therapeutic candidates in animal studies or approaching clinical trials. nNOS inhibitors have shown efficacy and excellent safety profiles in human and animal studies for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders and neuropathic pain.