Abstract

This pilot project investigated agricultural-related safety and health issues among Hmong refugees working on family-operated farms. Novel approaches, namely participatory rural appraisal and photovoice, were used to conduct a qualitative occupational hazard assessment with a group of Hmong farmers in Washington State. These two methods were useful in gathering participants’ own perspectives about priority concerns. Several identified problems were related to musculoskeletal disorders, handling and operating heavy machinery, heat and cold stress, respiratory exposures, pest management, and socioeconomic and language concerns. Findings from this study provide insight into the work-related challenges that Hmong refugee farmers encounter and can serve as a basis for occupational health professionals to develop interventions to assist this underserved group.

Since 1975, more than 3 million refugees have been resettled in the United States (Office of Refugee Resettlement, n.d.). At least 55,000 refugees have been admitted to the United States annually for the past 5 years and nearly 75,000 refugees were admitted in 2009, the highest number in more than a decade (Martin & Yankay, 2013). From 1975 to 2006, more than 115,000 Hmong refugees have been resettled in the United States (Office of Refugee Resettlement, 2008). As Hmong refugees settled and raised families in the United States, the Hmong population in the United States increased to more than 260,000 according to the 2010 U.S. Census (Pfeifer, Sullivan, Yang, & Yang, 2012).

The Hmong are an ethnic group originally from the mountainous regions of southern China and Southeast Asia. They practiced subsistence agriculture for centuries in their homeland, where it was considered a highly respected profession (Miyares, 1997). Hmong refugees have carried on this tradition in the United States (Minato, 2004), often seeking small-scale, family-operated farming opportunities for income generation, household consumption, and social activity. For example, Hmong refugees reported that they farm and garden because of the economic benefit, for pleasure, to grow familiar foods and herbal medicines, to socialize with other Hmong, and to participate in a familiar occupation (Rasmussen, Schermann, Shutske, & Olson, 2003).

Hmong refugees have been supported in small-scale farming through governmental and non-government organization programs. For example, in Washington State city and county government agencies along with faith-based organizations collaborated in the mid-1980s to form and operate the Indo-Chinese Farm Project. This project trained newly arriving Hmong to adapt their farming and marketing methods to the Pacific Northwest region (Evans, 2004). Another program through a major public university currently assists Hmong farmers with crop management and marketing strategies. Nationally, the Office of Refugee Resettlement of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services together with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and other non-governmental groups provide opportunities for refugee families working in agriculture to partner with government and non-government organizations to promote sustainable income and community food security.

Although refugee farmers may be skilled in agriculture in their countries of origin, they face distinct challenges when farming in the United States; they must farm unfamiliar crops in new environments, experience difficulty in accessing land and water, and learn to use new supplies, equipment, and pest management techniques (Tubene, White, Rose, & Burnie, n.d.). Agricultural safety and health issues also emerge as refugees learn to grow crops using production systems that differ from those to which they are accustomed. They work with new crops, tools and machinery, irrigation methods, and pesticides. Also, because they typically operate small, independent family farms, they may lack the resources to effectively control agricultural-related hazards and exposures. These risks are particularly notable and reflect the high rates of work-related injuries, illnesses (Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, 2012), and fatalities for the agricultural industry. For example, in 2012, agriculture recorded the highest fatal injury rate of any industry (Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, 2013).

This pilot project focused on Hmong refugee farmers, an understudied, hard-to-reach population of agricultural workers. The goal was to identify agricultural safety and health issues among Hmong farmers in Washington State using novel, participatory approaches for work-related hazard assessment and identification. The assessment approaches employed for this project were participatory rural appraisal and photovoice (both described below).

Of note, this effort also responded to specific goals outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s (CDC-NIOSH) National Agricultural, Forestry, and Fishing Agenda (2008). This agenda lists two goals that are particularly relevant for Hmong refugee farmers: reducing deleterious health and safety outcomes for workers who are more susceptible to injury or illness due to circumstances that limit options for safeguarding their own safety and health, and improving data collection and existing databases to provide information on safety and health disparities among vulnerable workers by seeking new data collection mechanisms where gaps exist (CDC-NIOSH, 2008). And, in its review of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing Research at CDC-NIOSH, the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (2008) identified “changes in demographics of the work-force” (p. 184) as a high priority, new, and emerging research area. Accordingly, conducting an assessment of agricultural safety and health issues that Hmong refugee farmers experience aligns well with these priorities.

Applying Research to Practice.

Participatory approaches are a means to conduct a workplace safety and health assessment yielding insightful information that represents workers’ perspectives about their own working conditions, particularly when working with unfamiliar, under-represented groups. The increasing diversity of the U.S. workforce compels occupational health professionals to pay more attention to underserved, minority groups who may be at disparate risk for injury and illness, especially if they are employed in non-traditional, small enterprise workplaces. More research is needed that investigates occupational safety and health concerns among refugee workers, and should give consideration to how cultural factors contributed to or influenced work-related health and well-being. Interventions tailored to small-scale, family-operated enterprises are needed, including education, training, and practical, low cost hazard control measures.

METHODS

Data were collected from March 2012 to January 2013, which included a full growing season from March through December of 2012. Given the population of focus and associated challenges (i.e., cultural differences, limited English proficiency, and recent arrival to the United States), participatory assessment approaches were viewed as more effective than conventional research methods (e.g., survey). Participatory approaches encourage study participants to provide data they view as meaningful and have their perspective more prominently represented in study procedures.

Also, before recruiting participants and initiating data collection, a community advisory board of agricultural industry professionals, researchers, and advocates with prior experience working with Hmong refugee farmers was assembled. This community advisory board provided advice on culturally appropriate and acceptable ways to interact with the Hmong community in the context of research and also provided feedback on sharing findings with the community.

All procedures were approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division.

Study Participant Recruitment

Participants were recruited from a Hmong refugee farming network in the western Washington State region via direct contact by the project’s Hmong community liaison (e.g., at community meetings, farming workshops, or at local farmers’ markets) or by direct mail advertisement flyer. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were at least 21 years of age, of ethnic Hmong descent, had either emigrated to or were born in the United States, and spent at least 20 hours per week engaged in farming-related activities for an independently operated farm. Individuals were not permitted to participate if they had any non-correctable visual impairment given the photography component of this project. Eleven individuals (9 females and 2 males) participated. Average age was 44 years (range: 27 to 60 years), and average residency in the United States was 23 years (range: 15 to 32 years). All participants had farmed for at least 6 years, with an overall average of 11 years.

Data Collection

Participatory Rural Appraisal

Inspired by adult education models and community empowerment theories, participatory rural appraisal reflects community-based participatory research principles and assists study participants to collect, analyze, and evaluate information about themselves and their local conditions. Participatory rural appraisal’s roots are in the fields of activist participatory research, agro-ecosystem analysis, applied anthropology, and farming field research (Chambers, 1994) and it has been used in agricultural development projects worldwide since the early 1980s. As an assessment method, participatory rural appraisal includes participant-generated data, such as visual diagrams and maps, direct observations, documentation of local conditions, storytelling, and seasonal calendars. Additionally, participatory rural appraisal has been used to obtain community input for research study design and data analysis (Almedom, Blumenthal, & Manderson, 1997), the design of practical solutions to a problem based on local knowledge (Fetterman, Kaftarian, & Wandersman, 1995), ethnographic knowledge generation for culturally appropriate education programs (Mueller, Assanou, & Guimbo, 2010), tailored health services for specific populations (Mahmood et al., 2002), and service and intervention monitoring and evaluation (Estrella & Gaventa, 1998).

For this project, participatory rural appraisal was implemented in three stages. Two separate participatory rural appraisal workshops were conducted—one at the start of the growing season (March 2012) and another after the end of the growing season (January 2013). Each session lasted 4 hours and consent was obtained before the first session began. For participating in each of the workshops, participants were offered either $50 cash or a gift card for farming supplies. The project’s community liaison, who is of Hmong descent, was present at both workshops to assist with language translation. Between these two sessions, during the actual growing season, participants engaged in photovoice and walk-through observations of participants’ farms using industrial hygiene approaches (Neitzel, Krenz, & de Castro, in press).

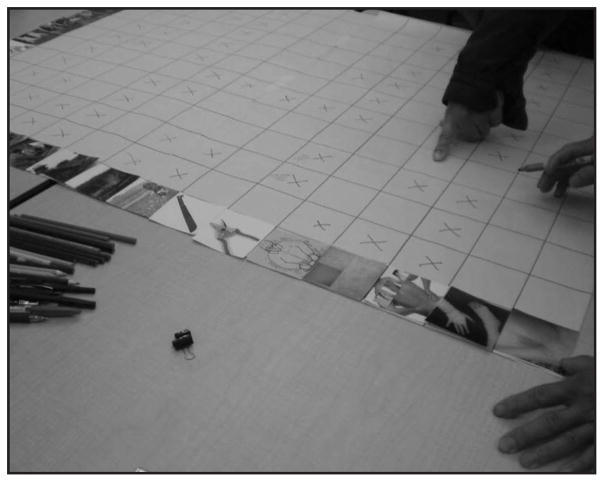

The start of the growing season workshop was designed to gain insight into types of farming activities and tasks, when tasks are performed throughout the calendar year, safety and health hazards and exposures, and work practices that mitigate the risk of injury or illness. For example, using pictorial cards in a matrix-style grid, participants matched commonly grown vegetable and flower crops to specific farming tasks (Figure 1). Another activity involved participants completing a matrix-style calendar to identify a schedule of farming activities for specific vegetable and flower crops. Specific hazards (e.g., pesticide use and heavy lifting) for each farming activity were also listed, if relevant. The session concluded with participant storytelling about work-related injury or illness experiences and ways farmers protect themselves. Participants were instructed on how to complete the photovoice component of the project.

Figure 1.

Matrix to identify farm work activities and associated safety and health concerns.

Photovoice

To capture illustrative examples of farm safety and health hazards, photovoice methodology was used. Photovoice allows community members themselves to (1) record and reflect on their community’s strengths and concerns, (2) promote critical dialogue and knowledge about community issues through group discussion of photographs, and (3) reach policy-and decision-makers to catalyze change (Wang, 1999; Wang & Burris, 1997; Wang & Redwood-Jones, 2001). Photovoice was originally developed in the late 1990s with village women in rural China as part of a women’s health promotion program (Wang & Burris, 1997). Since then, it has been increasingly applied to assess a variety of public health issues in domestic and international contexts (Catalani & Minkler, 2010; Cooper & Yarbrough, 2010; Dumbrill, 2009; Flum, Siqueira, DeCaro, & Redway, 2010; Hergenrather, Rhodes, Cowan, Bardhoshi, & Pula, 2009; Lopez, Eng, Randall-David, & Robinson, 2005; Rhodes et al., 2009; Schwartz, Sable, Dannerbeck, & Campbell, 2007; Wilkin & Liamputtong, 2010).

At the conclusion of the “start of the growing season” workshop, participants were given digital cameras (which they were allowed to keep as another incentive for participating) and were asked to photograph scenes throughout the growing season that depicted representations of farm work safety and health hazards. They were trained on photovoice methods, including the purpose of taking photographs, basic photography techniques, and camera operation and protection. Additionally, participants were instructed on ethical considerations (e.g., asking permission before photographing individuals and avoiding photographing faces, incriminating circumstances, minors, or identified addresses or automobile license plates) (Wang & Redwood-Jones, 2001). Participants were informed that collected photographs would be shared and discussed in a group setting during the end of the growing season workshop. A research team member scheduled visits with participants periodically throughout the growing season to retrieve digital photographs that had been taken.

A session at the end of the growing season included a group analysis of participant-taken photographs, a three-stage process that included (1) selecting (choosing photographs that best represented participants’ concerns and assets), (2) contextualizing (telling stories about what the photographs meant), and (3) codifying (identifying themes, issues, and theories) (Wang & Burris, 1997). Participants who took photographs selected those that they wanted to share and they were viewed by the group as a slide show. For each photograph, the participant-photographers explained the context of the photograph and why they chose to take that particular photograph. Descriptions of and reactions to photographs were documented. Also, a slideshow presentation of observations and data collected from farm walk-throughs was delivered and a group discussion to prioritize identified hazards followed.

RESULTS

Based on information culled from participatory rural appraisal workshop and photovoice discussions, several agricultural safety and health priorities were identified. Participants distinctly recognized some hazards as clear threats to health and well-being. Encouraging participants to relay detailed descriptions of farm work tasks and their photographs facilitated discourse and prompted realizations about additional safety and health concerns.

Musculoskeletal Disorders

Participants often talked about farm work tasks that put them at risk for musculoskeletal problems. They identified tasks that generally required difficult, awkward postures and positioning, such as bending for long periods, pulling crops out by hand, using tools such as knives to harvest vegetables and flowers, and washing crops. Weeding was noted as a frequent activity throughout much of the growing season that required stooping and bending. Participants noted that transporting crops to farmers’ markets required heavy lifting. For example, one participant mentioned that he typically transports 5-gallon buckets filled with water and cut flowers to farmers’ markets, with each bucket weighing approximately 30 pounds. Compounding this, participants remarked that, after being already fatigued from a long day of working in the fields, they have to prepare vegetables and flowers for loading during nighttime hours and rise very early the next morning to deliver and set up sales stands at farmers’ markets (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Preparing buckets of flowers night before taking to farmers’ market.

A common health complaint among both older and younger participants was acute and chronic back pain, which they readily associated with the physical demands of farm work, including tasks mentioned above and lifting and operating heavy machinery. One participant described farming as back-breaking work with no chance to rest. Also, participants mentioned that making flower bouquets to sell at farmers’ markets can lead to hand, wrist, and finger pain.

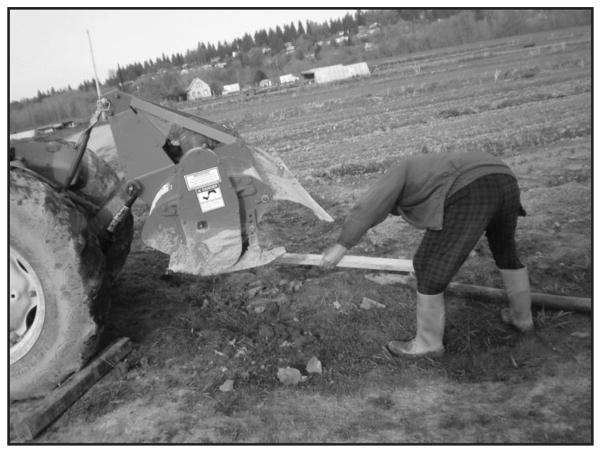

Heavy Machinery

Participants reported physical injuries from using heavy machinery. Many injuries occurred when loading and unloading rototillers from vehicles (e.g., fingers and hands wedged between van roofs and rototiller bar throttles). Operating rototillers also posed a risk for injury. One participant described an incident when a rototiller traveled over a bump in the field and jumped, knocking out a bystander’s teeth. One participant described frequently lifting plow attachments for a tractor as heavy, dangerous work. Another participant described frequently removing mud from a tractor tiller attachment as dangerous because the tractor sometimes rolled back or the attachment slipped and fell on the individual cleaning it (Figure 3). Also, operating heavy machinery (e.g., rototillers) increased noise exposure.

Figure 3.

Farmer removing mud from tractor tiller attachment.

Heat and Cold Stress

Throughout the growing season, participants experienced weather extremes, exposing them to both hot and cold temperatures. For example, preparation for the growing season typically begins in late February or early March, which are cold and rainy months in Washington State. During the growing season, particularly from June through early September, participants noted working all day in heat with sun exposure.

Respiratory Exposure

As a result of rototilling, participants complained of dust exposure that irritated eyes and affected breathing, leading to respiratory problems that impaired their ability to work. Some participants also noted allergic reactions to pollen and, in particular, bee stings, both of which made necessary work tasks difficult to complete.

Pest Management Activities

All participants stated that weed control is a constant difficult challenge. They noted that weed growth was persistent and invasive, threatening loss of vegetable and flower crops. One participant mentioned using a commercial-brand weed killer, but several stated they did not feel comfortable using chemicals (commercial or industrial) because they lacked education on the proper use of herbicides and pesticides. As such, as noted above, they spent much time and effort pulling weeds by hand. One participant shared a photograph of his crops infested with wireworms. Participants also discussed slugs as major pests that required slug bait (the active ingredient typically metaldehyde or iron phosphate, in pellet or meal form) for control. Birds were also noted as pests because they eat newly planted seeds.

Socioeconomic and Language Concerns

Interestingly, a common discourse about health and well-being centered around socioeconomic and language concerns. It was stated that most Hmong farmers cannot afford to purchase land for farming, so they must lease plots, often marginal to poor in quality and prone to flooding during high precipitation months in winter and spring. When cultivating the land in preparation for planting, participants complained about the mud. One participant described renting a tractor that was lodged in the mud for more than a week (Figure 4). This lost time resulted in additional expense and loss of income. Another talked about the challenge of accessing their farm land when roads flooded, again leading to loss of income. Participants expressed a desire to use cover crops (e.g., crimson clover and fava beans), which improve soil quality by preventing leaching of soil nutrients and growth of main crops. However, they noted that cover crop seeds were an added expense they could not afford.

Figure 4.

Tractor lodged in mud.

Although participants expressed pride in their work, they felt that the income generated from selling flowers and vegetables at farmers’ markets was inadequate. One participant described her flower display at a farmers’ market as being able to show off all the hard work (Figure 5). Another participant talked about selling floral bouquets, but commented that price points were too low relative to the work required.

Figure 5.

Flowers at farmers’ market.

One participant discussed a photograph documenting poor quality tulips to reflect the risk of purchasing poor quality bulbs. Participants regarded this crop loss as income loss. Another participant shared a similar photograph to describe the difficulties communicating with supply stores and companies because of language barriers. Several participants agreed and talked about being unsuccessful in asking for exchanges or refunds. Also, one participant noted challenges with conveying the type and timing of their bulb order, which resulted in an incorrect delivery and resulting income loss.

DISCUSSION

This article describes a pilot study to investigate an agricultural safety and health assessment of Hmong refugee farmers. Given the profile of this population, both as a group that is growing in number and as vulnerable workers, a need to prioritize concerns related to these farmers’ work was identified. The principal safety and health hazards identified through this project include musculoskeletal disorders, injuries from heavy machinery (e.g., rototillers and tractors), heat and cold stress, respiratory exposures, and activities associated with pest management. In reviewing the literature, no such effort to explicitly investigate agricultural safety and health problems among Hmong refugees has been reported. As such, no prior formal reports characterize occupational injury and illness risk with this population that could serve as a comparison.

A project conducted by Schermann et al. (2007) involved a farm work safety education project with Hmong refugees in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Based on the oral tradition of Hmong culture, folktales were developed to convey safety lessons related to farm work tasks. Three principal safety topics were included in these folktales: rototiller use, knife and hand tool use, and tasks related to selling at farmers’ markets. Additional safety and health issues integrated into the folktales included heat exposure, fatigue, lifting, repetitive motion, personal hygiene, and supervision of children. The issues identified in the current study align with those used in the folktale educational intervention. Drawing from this consistency, future research and interventions may consider emphasizing these same areas to address agricultural safety and health for Hmong refugee farmers.

Additional concerns raised by participants touched on socioeconomic and cultural concerns. This finding was unexpected, given the project’s focus on traditional agricultural safety and health. However, participants characterized these concerns within their overall day-to-day lives as farmers. For example, only being able to lease (and not own) land plots that are marginal in quality, unaffordable new or maintained equipment, and inadequate income selling at farmers’ markets all contribute to persistent lower socioeconomic status in the participants’ views. In turn, these circumstances perpetuate the challenge of improving their quality of life. Moreover, being newcomers to the United States, participants were sometimes unable to adequately communicate with English speakers, negatively impacting their farms and incomes. These situations call attention to their need for continued assistance from governmental agencies (local and federal) and community-based organizations to provide support services and programming for Hmong refugees.

An overarching goal of this project was to appraise the utility of participatory approaches to investigate safety and health issues with this worker population. As an assessment method, employing both the participatory rural appraisal format and photovoice activity were conducive to gaining participant perspective about what they viewed as safety and health priorities. These two participatory approaches transcended language and cultural differences between the participants and investigators. True to intent, participants drove the direction of the project’s data collection, and ultimate findings. For example, through the participatory rural appraisal workshops, the investigators provided a framework and farming schedule to identify safety and health hazards. However, participants directed what should be emphasized and modified in the list of priorities. Also, photovoice offered a channel through which participants could convey their own personal opinions, understandings, and explanations about farming. Other research teams planning to work with unfamiliar or understudied populations might consider the value of using participatory approaches to ensure that project findings more authentically reflect the study population’s views and experiences. Of note, as a complement to these participatory approaches, traditional worksite walk-through inspections were conducted on participants’ farms. Findings from these walkthroughs are reported elsewhere (Neitzel, Krenz, & de Castro, in press). Collectively, these various assessment methods offered a unique approach that triangulated data sources to gain a rich, multidimensional perspective of agricultural safety and health issues among Hmong refugee farmers, which may guide the development of possible intervention projects in the future.

LIMITATIONS

This study should be viewed in light of the following limitations. Communication with participants was constrained by language differences. Only one member of the research team (community liaison) spoke Hmong, so data collected through participatory rural appraisal workshops relied on his translation. It is possible that interpretations bi-directionally may not have fully captured stories, explanations, expressions, cultural idioms, and technical terminology. Significant effort was made to compensate for this, including repeating and reflecting participants’ statements and diligent note-taking during participatory rural appraisal workshops, as well as verifying study findings with the team’s Hmong-speaking community liaison.

Also, having only 11 individuals participate in the project limited the number of perspectives offered. Accordingly, study findings may not be representative or generalizable to the broader population of Hmong refugee farmers. Being a pilot study, a modest number of participants (10 females and 10 males) was targeted. Despite the recruitment efforts employed, only 9 females and 2 males participated. This result may have been due to low interest or unfamiliarity with participating in research-type projects. It is possible that alternative recruitment activities may have resulted in more farmers participating. However, consultation with the project’s advisory board and the team’s community liaison produced the recruitment activities chosen.

Participants expressed that taking photographs during the growing season competed with their need to tend to farming tasks. Some indicated that carrying a camera while they worked was difficult or that they did not want the camera to get dirty. As such, taking photographs may have had varying degrees of priority among participants. This situation limited the number of photographs from which to choose for the photovoice exercise. Despite this, participants did contribute interesting images that facilitated rich group discussions.

The principal members of the investigative team had not previously worked directly with Hmong refugees in a research context; they were relatively unfamiliar with Hmong culture, which may have hindered establishing rapport with study participants. Given the history of Hmong refugees (tied to war and political persecution) and the challenges associated with migrating to the United States, it is possible that study procedures and activities, as well as the investigative team’s Westernized style of interacting with participants, may not have been sensitive to Hmong values, practices, and world view. Accordingly, during the planning and design of the research project, the research team prioritized the consideration and accommodation of cultural differences, along with a mindfulness of historical events experienced by Hmong refugees.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Occupational health professionals can use participatory approaches as an alternative or adjunct to conventional workplace safety and health assessment methods. Participatory approaches can yield insightful information that better represents workers’ perspectives about their own working conditions. These approaches may be particularly useful when working with unfamiliar, underrepresented worker populations. As with this project, participatory assessment methods can overcome barriers (i.e., cultural and linguistic) between the investigative team and study participants.

Extending this point, occupational health professionals must acknowledge the increasing diversity of the U.S. population and hence workforce. Occupational health professionals must pay more attention to underserved, minority groups because their unique needs may be overlooked. Refugees like the Hmong may not be employed in traditional workplaces, but rather in small, family-operated enterprises. This likelihood may put them at disparate risk for occupational-related injury and illness given the absence of safety and health expertise accessible to them.

In this vein, limited occupational health research has been conducted with Hmong or other refugee groups, despite historic and continued entry into the United States. Occupational health professionals can lend their expertise and attend to the paucity of information known about refugee workers. Given the growing refugee population, a mounting need exists to investigate occupational safety and health issues with this not-so-hidden population and special consideration of how cultural factors contribute to or influence occupational health among refugees would be of significance.

Finally, this project points to the need for occupational health professionals to develop interventions to assist small-scale enterprises (independent, family-operated farms). In particular, education and training is sorely needed across the spectrum of safety and health problems. Additionally, even finding innovative ways to help small enterprises institute practical, lower cost hazard control measures and reduce occupational exposure risk would be beneficial.

CONCLUSION

The growing presence of Hmong refugees, as well as other ethnic groups, presents a unique opportunity to consider occupational safety and health needs among this group of underserved workers. With small-scale farming as a principal pursuit among Hmong refugees, the exposure to agricultural work hazards poses a significant threat to their health and well-being. This finding, in turn, contributes to disparate risk for work-related injury and illness. As a step toward addressing this problem, using novel participatory safety and health assessments can be fruitful, especially because worker perspectives are central and paramount. Accordingly, solutions that reflect and align with workers’ priorities can be developed.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Grant 2U54OH007544-11) and the National Institutes of Health–National Center for Research Resources (Grant 5KL2RR025015).

The authors thank Mr. Bee Cha, Ms. Helen Murphy, Ms. Stacey Holland, Mr. Robin Russell, and Ms. Marcy Harrington for their assistance and contributions.

Footnotes

The authors have disclosed no potential conflicts, financial or otherwise.

Contributor Information

Dr. A. B. de Castro, Associate Professor, University of Washington–Bothell, Nursing & Health Studies Program, and Director, Occupational & Environmental Health Nursing Program, University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, Washington.

Ms. Jennifer Krenz, Research Coordinator, University of Washington, Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center, Seattle, Washington.

Dr. Richard L. Neitzel, Assistant Professor, University of Michigan, Department of Environmental Health Sciences and Risk Science Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

References

- Almedom AM, Blumenthal U, Manderson L. Hygiene evaluation procedures: Approaches and methods for assessing water- and sanitation-related hygiene practices. Boston: International Nutrition Foundation for Developing Countries; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. Work-place injuries and illnesses–2011 (USDL-12-2121) 2012 Retrieved October 9, 2013, from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/osh.pdf.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. Census of fatal occupational injuries summary, 2012 (USDL-13-1699) 2013 Retrieved October 9, 2013, from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/cfoi.nr0.htm.

- Catalani C, Minkler M. Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior. 2010;37:424–451. doi: 10.1177/1090198109342084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. National Occupational Research Agenda: Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing Sector Council: National agriculture, forestry, and fishing agenda. Washington, DC: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R. The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal. World Development. 1994;22:953–969. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CM, Yarbrough SP. Tell me—show me: Using combined focus group and photovoice methods to gain understanding of health issues in rural Guatemala. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;20:644–653. doi: 10.1177/1049732310361894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumbrill GC. Your policies, our children: Messages from refugee parents to child welfare workers and policymakers. Child Welfare. 2009;88:145–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrella M, Gaventa J. Who counts reality? Participatory monitoring and evaluation: A literature review. Brighton, England: Institute of Development Studies; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Evans S. Washington’s Hmong farmers. Washington State Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs Newsletter. 2004;5:2. [Google Scholar]

- Fetterman DM, Kaftarian SJ, Wandersman A. Empowerment evaluation: Knowledge and tools for self-assessment and accountability. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Flum MR, Siqueira CE, DeCaro A, Redway S. Photovoice in the workplace: A participatory method to give voice to workers to identify health and safety hazards and promote work-place change–A study of university custodians. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2010;53:1150–1158. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergenrather KC, Rhodes SD, Cowan CA, Bardhoshi G, Pula S. Photovoice as community-based participatory research: A qualitative review. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2009;33:686–698. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.6.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez ED, Eng E, Randall-David E, Robinson N. Quality-of-life concerns of African American breast cancer survivors within rural North Carolina: Blending the techniques of photovoice and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:99–115. doi: 10.1177/1049732304270766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood MA, Khan KS, Kadir MM, Barney N, Ali S, Tunio R. Utility of participatory rural appraisal for health needs assessment and planning. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2002;52:296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DC, Yankay JE. Refugees and asylees: 2012. Annual Flow Report; April; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Minato R. Hmong Americans. Washington State Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs Newsletter. 2004;5:3. [Google Scholar]

- Miyares IM. Changing perceptions of space and place as measures of Hmong acculturation. The Professional Geographer. 1997;49:214–224. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller JG, Assanou I, Guimbo ID. Evaluating rapid participatory rural appraisal as an assessment of ethnoecological knowledge and local biodiversity patterns. Conservation Biology. 2010;24:140–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, Committee to Review the NIOSH Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing Research Program. Reviews of Research Programs of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies; 2008. Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing Research at NIOSH. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neitzel R, Krenz J, de Castro AB. Safety and health hazard observations in Hmong farming operations. Journal of Agromedicine. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2014.886319. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Refugee Resettlement, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. History. n.d Retrieved October 9, 2013, from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/orr/about/history.

- Office of Refugee Resettlement, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Report to Congress–FY 2007. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2013, from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/orr/annual_orr_report_to_congress_2007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer ME, Sullivan J, Yang K, Yang W. Hmong population and demographic trends in the 2010 census and 2010 American community survey. Hmong Studies Journal. 2012;13:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen RC, Schermann MA, Shutske JM, Olson DK. Use of the North American guidelines for children’s agricultural tasks with Hmong farm families. Journal of Agricultural Safety and Health. 2003;9:265–274. doi: 10.13031/2013.15456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Griffith DM, Yee LJ, Zometa CS, Montano J, Vissman AT. Sexual and alcohol risk behaviours of immigrant Latino men in the southeastern USA. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2009;11:17–34. doi: 10.1080/13691050802488405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermann MA, Bartz P, Shutske JM, Moua M, Vue PC, Lee TT. Orphan boy the farmer: Evaluating folktales to teach safety to Hmong farmers. Journal of Agromedicine. 2007;12:39–49. doi: 10.1080/10599240801985670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LR, Sable MR, Dannerbeck A, Campbell JD. Using Photovoice to improve family planning services for immigrant Hispanics. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2007;18:757–766. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubene SL, White OB, Rose M, Burnie G. An innovative approach for meeting the needs of underserved populations. n.d Retrieved October 9, 2013, from http://www.agnr.umd.edu/extension/agriculture/smallfarms/files/innovativeapproachgreensboro.pdf.

- Wang CC. Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. Journal of Women’s Health. 1999;8:185–192. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior. 1997;24:369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Redwood-Jones YA. Photovoice ethics: Perspectives from flint photovoice. Health Education & Behavior. 2001;28(5):560–572. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin A, Liamputtong P. The photovoice method: Researching the experiences of Aboriginal health workers through photographs. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2010;16:231–239. doi: 10.1071/PY09071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]