Abstract

Although botulinum neurotoxin serotype A (BoNT/A) is known for its use in cosmetics, it causes a potentially fatal illness, botulism, and can be used as a bioterror weapon. Many compounds have been developed that inhibit the BoNTA zinc-metalloprotease light chain (LC), however, none of these inhibitors have advanced to clinical trials. In this study, a fragment-based approach was implemented to develop novel covalent inhibitors of BoNT/A LC. First, electrophilic fragments were screened against BoNT/A LC, and benzoquinone (BQ) derivatives were found to be active. In kinetic studies, BQ compounds acted as irreversible inhibitors that presumably covalently modify cysteine 165 of BoNT/A LC. Although most BQ derivatives were highly reactive toward glutathione in vitro, a few compounds such as natural product naphthazarin displayed low thiol reactivity and good BoNT/A inhibition. In order to increase the potency of the BQ fragment, computational docking studies were employed to elucidate a scaffold that could bind to sites adjacent to Cys165 while positioning a BQ fragment at Cys165 for covalent modification; 2-amino-N-arylacetamides met these criteria and when linked to BQ displayed at least a 20-fold increase in activity to low μM IC50 values. Unlike BQ alone, the linked-BQ compounds demonstrated only weak irreversible inhibition and therefore acted mainly as non-covalent inhibitors. Further kinetic studies revealed a mutual exclusivity of BQ covalent inactivation and competitive inhibitor binding to sites adjacent to Cys165, refuting the viability of the current strategy for developing more potent irreversible BoNT/A inhibitors. The highlights of this study include the discovery of BQ compounds as irreversible BoNT/A inhibitors and the rational design of low μM IC50 competitive inhibitors that depend on the BQ moiety for activity.

1. Introduction

Botulinum toxin is the most toxic known substance and has an estimated intravenous LD50 of 1-2 ng/kg in humans.[1] Eight different serotypes of botulinum toxin exist, each with their own potencies and modes of action, however, all serotypes are neurotoxic by means of blocking acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction causing muscle paralysis. The most potent botulinum neurotoxin serotype, serotype A (BoNT/A), is widely recognized as the commercial product BOTOX®, used cosmetically to reduce facial wrinkles. When administered in low doses, BoNT/A is a vital therapeutic used to treat a variety of conditions characterized by uncontrollable muscle spasms such as blepharospasm (spasmotic eye closure) and dysphonia (vocal fold spasms).[2, 3] On the other hand, BoNT/A is considered a significant bioterror threat due to its high potency and relative ease of mass production and weaponization.[1, 4] The toxin is naturally produced during sporulation by Clostridium botulinum, an anaerobic, Gram-positive bacterium. If grown in sufficient quantities C. botulinum can be disseminated into food supplies or adsorbed onto fine particles for aerosolization.[4] An actual BoNT/A bioterror attack on a human population would result in widespread acute flaccid paralysis and bulbar palsies (resulting in difficulty speaking, swallowing and chewing).[1] Although no bioterror attacks involving BoNT/A have been successfully executed, many countries such as Iran, Iraq, North Korea and Syria have developed and/or stockpiled weapons containing botulinum toxin.[1]

In contrast to bioterrorism, the most common human exposure to botulinum toxin takes the form of a foodborne illness known as botulism. Treatment for botulism consists of FDA-approved antibody-derived antitoxins, however, antitoxins must be administered immediately after exposure to the toxin to achieve efficacy.[5] Moreover, these antitoxins cannot neutralize toxins that have been endocytosed into neurons. The BoNT/A mechanism of action involves endocytosis of the 150 kDa holotoxin via the 100 kDa heavy chain into neurons.[6] Subsequently, the 50 kDa zinc-metalloprotease light chain (LC) of BoNT/A cleaves the 25 kDa SNAP-25, one of three SNARE complex proteins responsible for fusing acetylcholine-containing vesicles to synaptic plasma membranes.[7] For the past 10 years, a significant effort has been put forth to develop peptide and small molecule inhibitors of the BoNT/A LC.[8-11] With the exception of chicoric acid as an exosite inhibitor, most BoNT/A LC inhibitors bind to the active site and typically contain a zinc chelating moiety such as hydroxamic acids, however, two reports exist of covalent BoNT/A inhibitors. [12, 13] Unfortunately, no known compounds possess noteworthy in vivo efficacy in ameliorating BoNT/A-induced toxicity; therefore, discovery of novel BoNT/A LC inhibitors continues to be an important research endeavor.

The active site of BoNT/A contains a cysteine residue (165) that has recently been shown to be essential for catalytic activity. In mutagenesis studies, swapping Cys165 for a serine drastically reduced catalytic activity 50-fold. Furthermore, incubation of BoNT/A with a thiol reactive compound (3-aminopropyl)methanethiosulfonate (MTSPA) irreversibly inhibited catalytic activity (Ki=7.7μM).[14] In light of this data, we sought to uncover novel covalent inhibitors of BoNT/A which have the advantage of persistently inactivating the toxin long after initial exposure to the inhibitor. Irreversible inhibition is especially desirable for BoNT/A because the toxin has a very long half-life (~10 days) causing symptoms of intoxication for 4-6 months.[15] From screening electrophilic fragments, we have found that 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ) derivatives are potent irreversible inhibitors of BoNT/A. We attempted to enhance the activity of the BQs via fragment-based design to increase the effective molarity of the electrophilic warhead relative to Cys165.

BQs are highly relevant to biological systems and are well known for their therapeutic properties. Many BQs are produced naturally by certain plants for example thymoquinone (23) is found in black cumin (Nigella sativa) and juglone (7) and naphthazarin (13) are found in certain species of walnut trees of the genus Juglans.[16, 17] BQs, namely quinone anti-cancer drugs, can elicit cytotoxic effects via reduction by various enzymes forming reactive oxygen species and quinone methides, both of which can damage (or alkylate) biomolecules e.g. DNA.[18, 19] In contrast, many quinone-containing molecules such as endogenously-synthesized ubiquinone (coenzyme Q10) act as anti-oxidants.[20] Upon bioreduction, ubiquinone and related compounds protect against lipid peroxidation, DNA oxidation and protein degradation.[21] Despite potential toxicity associated with BQ compounds, medicinal chemistry campaigns to develop irreversible inhibitors of VEGFR-2 as anti-cancer drugs have employed BQ moieties to covalently modify specific cysteine residues.[22, 23] In our study, we used a similar strategy to target Cys165 in BoNT/A light chain.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Discovery of benzoquinones as irreversible BoNT/A inhibitors

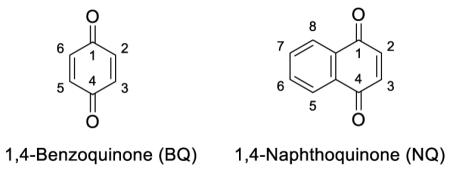

In an effort to discover new irreversible inhibitors of BoNT/A, we screened a series of small molecular weight electrophiles mostly containing an alpha, beta unsaturated carbonyl motif. We chose a commonly used assay for BoNT/A inhibitor screening which involves the SNAPtide™ FRET substrate.[24] The 13 amino acid SNAPtide substrate mimics the region of the native SNAP-25 substrate that binds to the BoNT/A active site. BoNT/A LC readily cleaves SNAPtide producing fluorescence by releasing the donor and acceptor chromophores at the SNAPtide termini. In our SNAPtide assay screen, the only electrophile that possessed any inhibitory activity was N-ethylmaleimide which weakly inactivated BoNT/A at [I]=100 mM. We reasoned that the inhibitory activity of N-ethylmaleimide may be attributed to its cyclic structure, prompting us to investigate other cyclic electrophiles. 1,4-Benzoquinones (BQs) and 1,4-naphthoquinones (NQs) were selected for screening due to their known cysteine reactivity. Results from the SNAPtide assay revealed that BQs and NQs can be potent inhibitors of BoNT/A (Table 1) and that their inhibitory activity was time dependent suggesting an irreversible mode of inhibition.

Table 1.

Activity of BQ and NQ derivatives as covalent inactivators of BoNT/A LC

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Compound # |

Name | kinact/KI (M−1 s−1) |

| 1 | 2,5-diCl-BQ | 84 |

| 2 | 2-Cl-BQ | 51 |

| 3 | BQ | 17 |

| 4 | 2-(4-I-Ph)-BQ | 10 |

| 5 | 2-Ph-BQ | 9.7 |

| 6 | 2-OMe-3-Tol-BQ | 9.5 |

| 7 | 5-OH-NQ | 5.3 |

| 8 | 5-OCyclopentoyl- NQ |

4.7 |

| 9 | 2-OMe-BQ | 4.1 |

| 10 | 5-OAc-NQ | 4.0 |

| 11 | 2-Estrone-BQ | 3.9 |

| 12 | 2-Me-BQ | 3.5 |

| 13 | 5,8-diOH-NQ | 2.2 |

| 14 | 5-OBn-NQ | 2.0 |

| 15 | NQ | 2.0 |

| 16 | 2-(2-COOH-Et)- BQ |

1.2 |

| 17 | 2-Me-NQ | 1.1 |

| 18 | 5-OMe-NQ | 0.99 |

| 19 | 6-OH-NQ | 0.94 |

| 20 | 2-Tol-NQ | 0.91 |

| 21 | 2,5-diOMe-3-Tol- BQ |

0.82 |

| 22 | 2-(COOH-Me)-BQ | 0.56 |

| 23 | 2-iPr-5-Me-BQ | 0.38 |

| 24 | 2,6-diOMe-BQ | NA |

| 25 | 2,6-diMe-BQ | NA |

| 26 | 2-OMe-5-Tol-BQ | NA |

Compounds were tested at 50 μM in the SNAPtide assay over a 1.5 h period. NA = not active

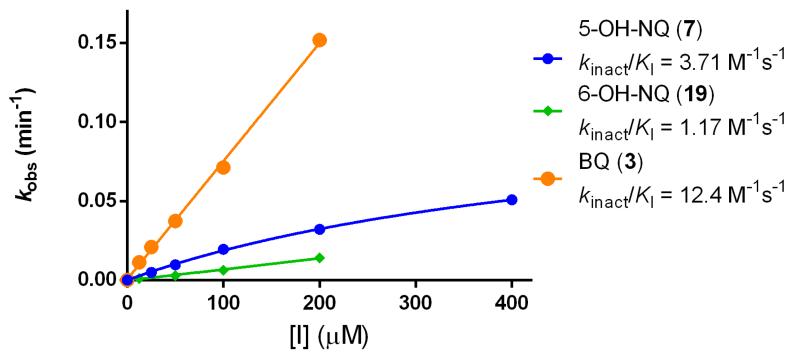

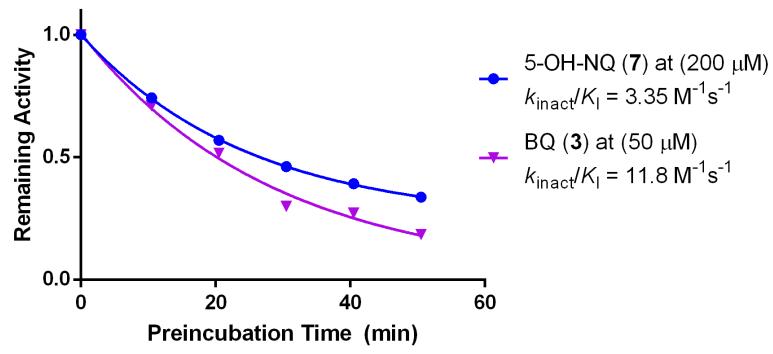

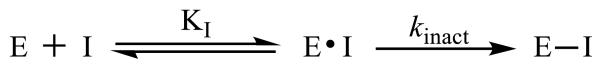

The potency of BQs and irreversible inhibitors in general depends on two factors: affinity for the target (KI) and rate of covalent bond formation with the target residue (kinact) (Figure 1). To account for the inhibitory mechanism of covalent inhibitors, we expressed the inhibitory potential of each compound in terms of kinact/KI (Table 1). Additionally, we elucidated the inhibitory mechanism of 5-OH-NQ (7) and BQ (3) by testing these compounds at a wide range of concentrations and preincubation times in the SNAPtide assay. Results from the multi-dose experiment indicate that concentration of these compounds is directly proportional to kobs of BoNT/A inhibition while saturating kinetics was not observed (although kobs for 5-OHNQ appears to tail off slightly at 200 μM) (Figure 2). Furthermore, when the compounds were preincubated with BoNT/A and diluted 50 fold into substrate, remaining BoNT/A activity decreased exponentially as a function of preincubation time with inhibitor (Figure 3). The resulting kinact/KI values in both assays were almost identical, thus confirming the irreversible inhibition mechanism of BQ and NQ.

Figure 1.

Mechanism of action of covalent inhibitors

Inhibitor (I) binds to the enzyme (E) with a certain affinity (KI) to form the enzyme-substrate complex (E·I). Then, the inhibitor irreversibly forms a covalent bond with the enzyme according to a certain rate constant (kinact) to form the inactivated enzyme-substrate complex (E-I).

Figure 2.

Dose-dependent inactivation of BoNT/A LC by BQ derivatives

Inhibitors were incubated with BoNT/A LC in the presence of SNAPtide substrate and fluorescence was measured over a 1.5 h period. Values for kobs were calculated for each inhibitor concentration.

Figure 3.

Time-dependent inactivation of BoNT/A LC by BQ compounds

Inhibitors were preincubated with BoNT/A LC for various time periods and diluted 50 fold into SNAPtide substrate. Remaining activity was determined for each time point as a ratio of initial velocities.

2.2. SAR

A series of known BQ analogues was synthesized and tested to thoroughly probe the structure-activity relationship of this chemotype. Manipulation of both the steric and electronic character of the BQ scaffold had a large impact on inhibitory activity. Generally, electronics had the greatest impact on inhibitory activity since electron withdrawing groups increased activity while electron donating groups decreased it. The most significant substituent effect was observed with the addition of a chlorine atom at the 2 and/or 5 position of the BQ ring. The dichlorinated BQ (1) when incubated with BoNT/A at 50 μM completely abrogated catalytic activity after 20 min, and therefore stands as one of the most potent covalent BoNT/A inhibitors ever reported. However, the major liability of this inhibitor is that the chlorination appears to almost exclusively influence electronics over sterics; the electronegative atom heightens the electrophilicity and thiol reactivity (Table 2) without increasing binding affinity. In terms of steric characteristics that influence BQ inhibitory activity, the 2,3-substitution appears to be most favorable compared to 2,5; 2,6; or 2,3,5/6. The best demonstration of this is comparing 2,3 (6) and 2,5-methoxytolylBQ (26) in which case the former is much more potent (Table 1). The favorability of the 2,3-substitution prompted us to test a series of juglones (5-hydroxynaphthoquinones) which were functionalized at the 5-OH, a strategy previously used to develop anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory compounds.[25] None of the tested derivatives displayed better activity relative to the parent compound (Table 1).

Table 2.

Thiol reactivity of select compounds

| Compound # |

%GSH remaining at 10 s |

%GSH remaining at 30 min |

kGSH (min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 89 | 49 (35) | 0.032 |

| 13 | 85 | 39 (26) | 0.025 |

| 18 | 80 | 27 (14) | 0.053 |

| 19 | 71 | 32 (22) | 0.036 |

| 14 | 57 | 39 | |

| 10 | 51 | 26 | |

| 15 | 47 | 20 | |

| 8 | 46 | 25 | |

| 24 | 45 | 0 | |

| 7 | 44 | 32 | |

| 12 | 35 | 5 | |

| 6 | 25 | 19 | |

| 3 | 24 | 6 | |

| 25 | 22 | 0 | |

| 5 | 21 | 8 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

1 hour GSH% values are indicated with (). 1 mM of each compound was incubated with 1 mM glutathione (GSH) and the amount of free GSH remaining was determined by DTNB. Only 4 compounds were unreactive enough to calculate a second order rate constant (kGSH) of Michael adduct formation.

2.3. Thiol Reactivity

We measured thiol reactivity independent of BoNT/A affinity by incubating our compounds with glutathione and measuring free thiol concentrations spectrophotometrically at various time points with Ellman’s reagent (5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid), DTNB). Thiol reactivity is important in the context of covalent inhibitors because electrophilic chemotypes can react readily with endogenous thiols e.g. glutathione, creating off-target effects while reducing drug efficacy.[26, 27] Overall, BQ thiol reactivity was very high compared to linear alpha-beta unsaturated carbonyl compounds e.g. acrylamides and only a few compounds were unreactive enough to calculate a second order rate constant (kGSH, Table 2). Even these compounds (13, 18, 19, 21) possessed kGSH values of 30 times greater than N,N-dimethylacrylamide (kGSH = 0.0011 min−1), a Michael acceptor moiety similar to that found in ibrutinib which is an FDA-approved drug for treatment of mantle cell lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.[28-30]

BQ compounds exhibiting the greatest inhibitory activity in the SNAPtide assay typically demonstrated high thiol reactivity. As expected, these compounds contained electron withdrawing groups (see compound 1) which raise LUMO energies of the BQs, causing BQs to more readily accept electrons from thiol HOMOs.[22] However, many compounds did not exhibit a positive correlation between LUMO energy and BoNT/A activity. For example N-ethylmaleimide showed one of the highest thiol reactivities but was one of the weakest inhibitors tested. On the other hand, natural product naphthazarin (13, 5,8-dihydroxynaphthoquinone) exhibited one of the lowest thiol reactivity profiles while retaining good inhibitory activity. Clearly, binding affinity in addition to thiol reactivity, plays an important role in governing BoNT/A inhibition of these irreversible inhibitors. Given our results, thiol reactivity and binding affinity could in theory be further tuned to yield even more potent covalent inhibitor fragments.

2.4. Strategies to improve benzoquinone potency by linking benzoquinone to other pharmacophores

We sought to explore the possibility of combining BQ with other pharmacophores to enhance inhibitor potency and selectivity. Since the BoNT/A active site zinc is directly adjacent to cysteine 165, we hypothesized that a dual zinc chelator/cysteine trap inhibitor could be highly potent. In theory, linking BQ to a fragment with high affinity for the adjacent active site could increase the effective molarity of BQ relative to Cys165, thus greatly increasing kinact. Moreover, the crystal structure of MTSPA covalently bound to BoNT/A reveals a potential interaction between the zinc and the MTSPA amine.[14] To evaluate our linked fragment inhibitors, we employed a more robust assay involving a 66-mer peptide substrate that contains the 66 amino acids most essential for BoNT/A LC binding of SNAP-25. By means of LCMS, the assay quantifies the amount of 9-mer cleaved by BoNT/A LC relative to an isotopically labelled 9-mer internal standard.[31] Also, BQ (3) inactivation in the 66-mer assay was comparable to the SNAPtide assay.

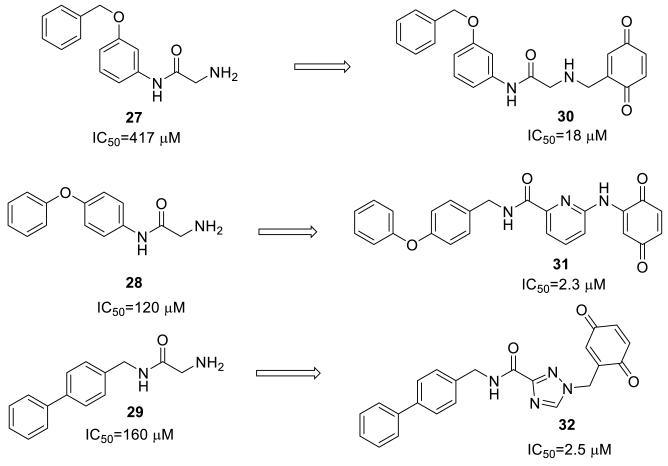

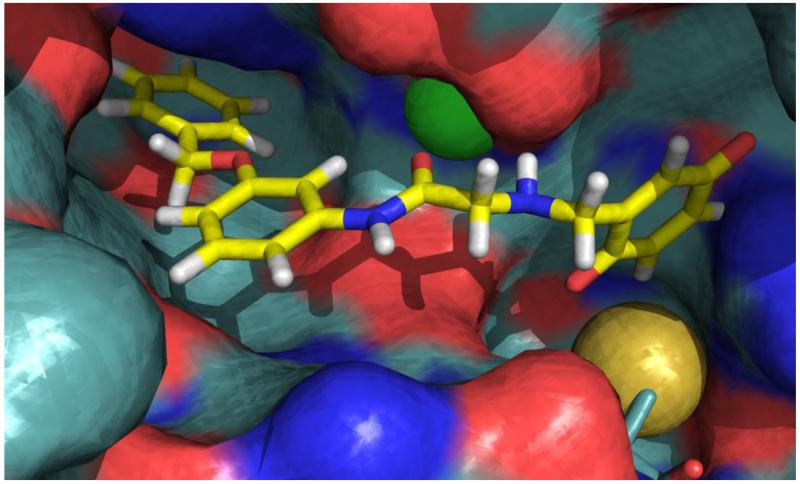

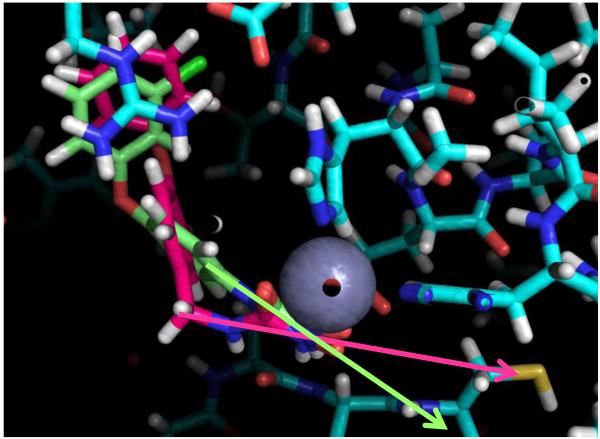

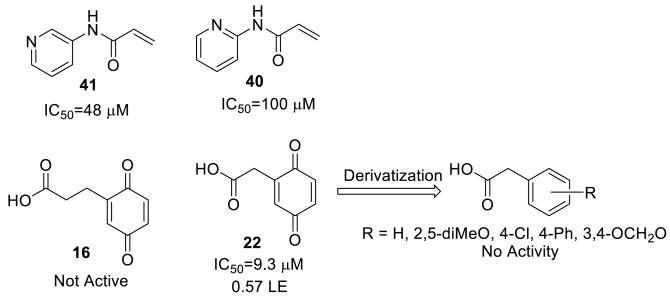

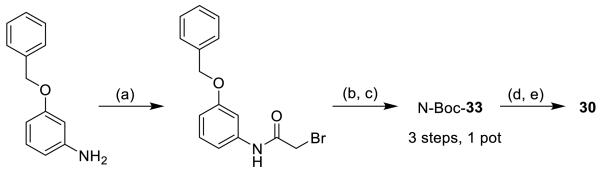

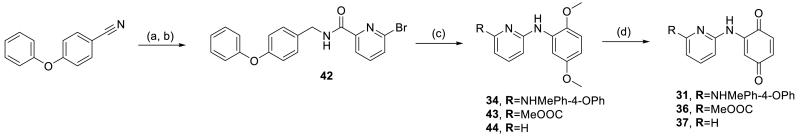

We pursued a rational, fragment-based design of a BQ-linked inhibitor to effectively position the electrophile close to Cys165. From the co-crystal structure of a previously reported peptide inhibitor of BoNT/A,[9] we gleaned that an amino acetamide moiety could chelate zinc, while accommodating both a fragment to bind into a nearby hydrophobic pocket (S1’ pocket) and fragment to covalently modify Cys165. Indeed, we found that a series of 2-amino-N-(aryl)acetamides could weakly inhibit BoNT/A with the most potent being aryl=4-phenoxyphenyl (27), IC50=120 μM (Figure 6). We performed docking studies using previous methodology [10, 47] to find the best amino acetamide that when linked to BQ, would properly position it near Cys165. Results from the docking studies indicated that the amino acetamide with aryl=3-benzyloxyphenyl (28) connected to BQ via a methylene linker, perfectly positioned all three pharmacophores (compound 30, Figure 4). The benzyloxyphenyl moiety is buried within the S1’ pocket (back left), the amino acetamide is interacting with zinc (green sphere) while the BQ is ideally positioned to covalently modify Cys165 (yellow sphere=S). In light of this discovery and with further docking studies, we designed two other analogues (31, 32). We found that phenoxyphenyl and biphenyl with a methylene linker to the aminoacetamide gave favorable fitness scores while providing a perfect angle to position a linked BQ fragment near Cys165 (Figure 5). Heterocycles (pyridine and triazole) were substituted in place of the secondary amine in order to constrain the rotatable bonds and to decrease the basicity of the amine (a potential liability in the presence of BQ).

Figure 6.

Activity and structures of aminoacetamide inhibitors and their BQ-linked analogues

As predicted by docking studies, linkage of BQ to aminoacetamide inhibitors greatly enhances inhibitory activity in the 66-mer assay. However, BQ covalent inactivation by these compounds did not significantly contribute to overall BoNT/A inhibition.

Figure 4.

Compound 30 docked into the active site of BoNT/A LC

Lowest energy conformations were generated using OMEGA and then docked into 4ELC and 2IMB BoNT/A LC crystal structures using FRED. Compound 30 gave one of the highest fitness scores while perfectly aligning all pharmacophores within the enzyme. The lipophilic benzyloxyphenyl tail is buried within the S1’ pocket (back left), the aminoacetamide is interacting with the zinc (green sphere) while the benzoquinone is perfectly positioned for covalent interaction with cys 165 (S=yellow sphere).

Figure 5.

Docking studies for optimizing lipophilic tail

Docking studies with various lipophilic tails indicate that phenoxyphenyl, benzyloxyphenyl and biphenyl groups gave high fitness scores while a methylene linker in between the tail and aminoacetamide provides an ideal angle to project a linked BQ toward Cys165. Blue=enzyme, green=compound without CH2 linker, pink=compound with CH2 linker.

In comparing the activities of the linked BQ inhibitors vs. the analogous amino acetamides, the addition of the BQ increased potency to low μM IC50 (26-fold in comparing 27 to 30, 21-fold in comparing 28 to 31 and 64-fold in comparing 29 to 32) (Figure 6). However, the BQ linked inhibitors showed only weak time-dependent inactivation of BoNT/A, suggesting that the compounds acted primarily as competitively inhibitors. In fact, when 31 was preincubated for 30 min at 50 μM with BoNT/A and diluted into substrate, enzyme activity was only slightly reduced (kinact/KI =1.7 M−1s−1). In comparing 31 to other BQs (Table 1) it lies within the weakest 25% of all BQs tested based on covalent inactivation, despite giving a low IC50 value in the competitive 66-mer assay.

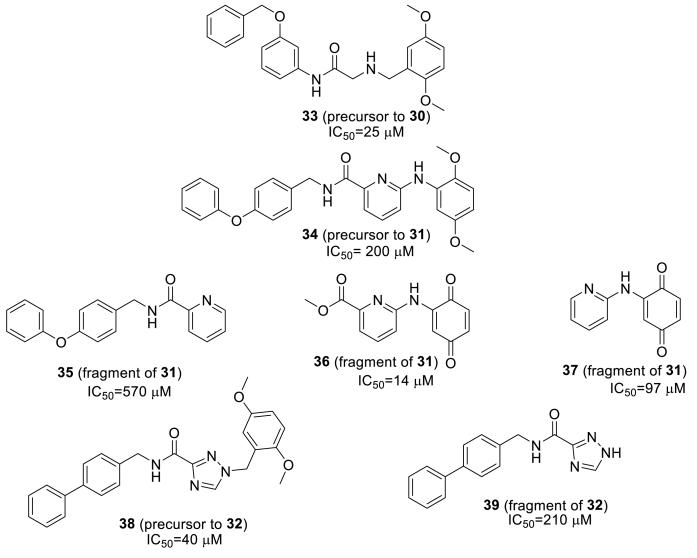

We further probed the SAR of the linked BQ inhibitors by testing various fragments and 2,5-dimethoxyphenyl precursors of inhibitors 30-32. Although the 2,5-dimethoxyphenyl moiety in place of BQ was well tolerated in 33 vs. 30, it led to a decrease in activity for 34 vs. 31 and 38 vs. 32 (Figure 7). Evaluation of fragments of 31 (35-37), elucidated that the carbonyl, pyridine and benzoquinone were the most important functional groups for the activity of 31. Furthermore, high IC50 values from fragments 35 and 39 suggest that the lipophilic aryl groups do not possess good group efficiency (GE). This result corroborates the low activity of aminoacetamides found in Figure 6. However, a 7-fold increase in activity was observed by adding the phenoxyphenyl fragment (compare 36 to 31). Overall SAR studies show that every fragment of linked inhibitors 30-32 contributes to activity, suggesting that the inhibitors are assuming the Figure 4 binding mode we had intended based on docking studies. Although significant covalent modification of Cys165 was not observed, this result can be explained by the fact that the docking software does not select for possible inhibitor-protein covalent interactions; the software identified a BQ binding site near Cys165 (Figure 4) in both Cys165 accessible (4ELC) and inaccessible (2IMB) crystal structures, however, that is no guarantee the BQ will covalently interact with Cys165.

Figure 7.

Activity and structures of various precursors and fragments of compounds 30-32

Results from testing compounds in the 66-mer assay reveal that the BQ moiety is the most important moiety for activity; removal of lipophilic tail is less critical. Replacement of BQ with precursor dimethoxyphenyl groups led to a decrease in activity.

In light of the failure of our linked benzoquinones to act as effective BoNT/A covalently inactivators, we simplified our strategy to include small molecular weight dual zinc chelator/cysteine trap compounds. We tested both pyridyl acrylamides and carboxyl benzoquinones (Figure 8), and given the ~7 Å distance between Zn and Cys165, these compounds would be the ideal length to access both. Pyridyl acrylamides 40 and 41 weakly inhibited BoNT/A. 2-(2-carboxyethyl)-1,4-BQ (22) was fairly active against BoNT/A and possessed good ligand efficiency (LE) while 2-(3-carboxypropyl)-1,4-BQ (16) was inactive. However, in the 66-mer preincubation assay, 22 inhibited BoNT/A no more than related compound 12 (2-Me-BQ) with a weak kinact/KI of 2.5 M−1 s−1 while 41 displayed no irreversible inhibition. Overall, our simplified dual-action inhibitors still suffered from the same problem as 31 where their covalent modification only slightly contributed to their inhibitory activity. Despite this, 22 is a high LE fragment that could easily be derivatized for development of a more potent competitive inhibitor. In fact, we tested phenylacetic acid derivatives as analogues of 22 and we found that they were completely inactive at 50 μM (Figure 8). The lack of activity in the phenylacetic acid compounds also suggests that the 1,4-benzoquinone moiety is critical for achieving potency.

Figure 8.

Activity and structures of dual zinc chelating/cysteine trap inhibitors

66-mer assay results indicate that 22 is a high LE inhibitor of BoNT/A LC, and that pyridyl acrylamides are weak inhibitors. However, BoNT/A inhibition by these compounds is not significantly impacted by covalent inactivation. Conversion of the benzoquinone to analogous phenylacetic acid compounds ablated BoNT/A LC inhibitory activity, further demonstrating the necessity of the BQ moiety for activity.

2.5. Kinetic Studies

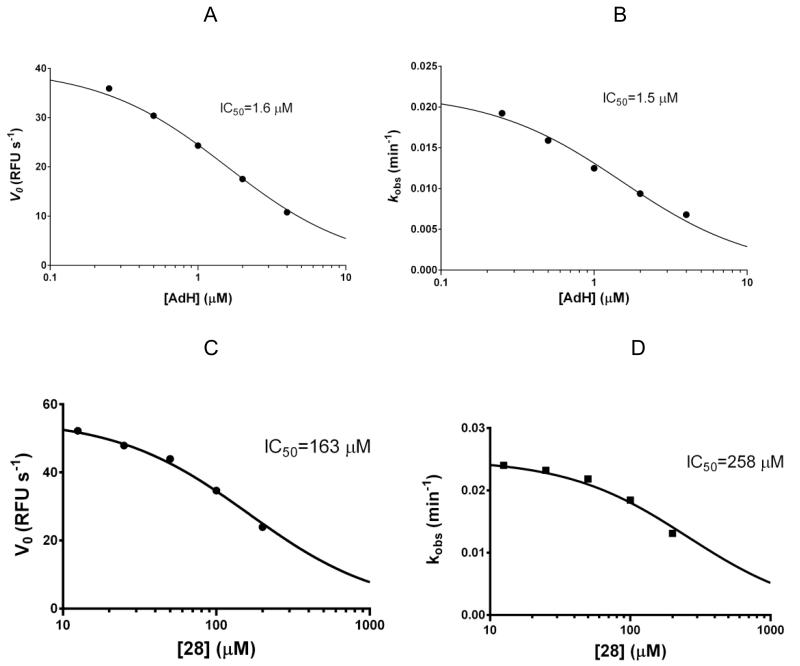

We investigated the discrepancy between inhibitory activity and covalent modification by observing BQ inactivation via the SNAPtide assay in the presence of other inhibitors. Competitive inhibitor adamantanemethylhydroxamate (AdH) has a Ki of 460 nM, and crystallographic data shows AdH interacts with the S1’ pocket while chelating the zinc of BoNT/A.[10] Since no overlap exists between the binding site of this compound and Cys165, we hypothesized that AdH and BQ could inhibit BoNT/A cooperatively or in a non-mutually exclusive manner. Kinetic assays reveal that AdH actually competes with BQ-mediated inactivation of BoNT/A (Figure 9A,B). Furthermore, 28 which presumably has the same binding mode as AdH, also competed with BQ-mediated BoNT/A inhibition (Figure 9C,D). A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that AdH binding induces an enzyme conformation in which Cys165 is locked in a solvent inaccessible position. Cys165 is also solvent inaccessible in the uninhibited BoNT/A conformation,[32] although a degree of enzyme flexibility must exist that allows electrophiles like BQ and MTSPA to access Cys165; BoNT/A is known to be a fairly flexible enzyme.[33] Lastly, we tested BQ in the presence of chicoric acid (CA), a known exosite inhibitor, and BQ inactivation was not affected by CA (data not shown). In contrast to AdH, CA induces a catalytically inactive conformation that must not render Cys165 inaccessible to BQ. Kinetics studies support our hypothesis that linked inhibitors 30-32 are acting as a competitive inhibitors via the binding mode predicted in Figure 4; binding of the lipophilic tail renders Cys165 inaccessible for covalent modification but does not disrupt the favorable non-covalent binding of BQ adjacent to the active site zinc. In light of these results, development of ‘enhancer’ compounds that could shift Cys165 to a solvent accessible position would be highly desirable in the context of BoNT/A irreversible inhibitors.

Figure 9.

Dose-dependent competition of zinc-chelating, active site inhibitors with BQ

(A) Impact of AdH on initial rates of BoNT/A LC (B) Impact of AdH on kobs of BQ inactivation (C) Impact of 28 on initial rates of BoNT/A LC (D) Impact of 28 on kobs of BQ inactivation. Active site inhibitors AdH and 28 compete with BQ covalent inactivation.

3. Conclusion

We have discovered that 1,4-benzoquinones and naphthoquinones are irreversible inhibitors of BoNT/A. Important factors that enhance BQ activity are substitution at the 2 and 3 positions (such as in NQ) and substituents that are electron withdrawing e.g. chloro. Respectively, these factors allow steric accessibility of cysteine to the electrophilic portion of BQ (in contrast to 2,6 and 2,5 substitution) and enhance the thiol reactivity by increasing LUMO energies. An increase in BoNT/A activity of BQs typically led to a concurrent increase in non-specific thiol reactivity although natural product NQ, naphthazarin, stood out as possessing low thiol reactivity while retaining good BoNT/A activity. The requirement for high thiol reactivity to achieve potency highlights the difficulty in developing drug-like irreversible inhibitors of BoNT/A with low thiol reactivities on the level of ibrutinib. The buried position of Cys165 is likely to blame for the need for ‘hot’ electrophiles in order to covalently modify Cys165. An alternative strategy for covalent inhibitor design would be screening for ‘enhancer’ compounds that would shift the enzyme to a Cys165-exposed conformation for modification by mildly-reactive electrophiles.

Despite the failure of our attempts to create more potent irreversible inhibitors via a fragment-based approach, the process has led to the discovery of low micromolar IC50 competitive inhibitors (30-32); docking and SAR studies suggest that linking 1,4-benzoquinone to zinc and S1’ site pharmacophores was successful for inhibitor design. Lastly, kinetic studies indicate that binding of zinc-chelating, active site inhibitors and BQ covalent inhibition are mutually exclusive, refuting the strategy of targeting the zinc and S1’ site for irreversible inhibitor development. However, the fact that our rationally-designed compounds achieved potency stands as a demonstration of how computational docking can identify active compounds without the need for the synthesis and screening of large small-molecule libraries.

4. Experimental

4.1. Synthesis

4.1.1. General Methods

NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer. All chemical shifts are reported in ppm using the CDCl3 solvent peak as a reference. All starting materials and reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. All reactions were run under N2 gas and with dry, distilled solvents unless otherwise noted. LCMS as well as TLC visualized by UV light and/or ninhydrin staining were routinely used to monitor reactions. Following aqueous workups, the organic layer was always dried using MgSO4 and then filtered. Compounds 1-3, 7, 9, 12, 13, 15, 17, 23-25 were obtained from commercial sources while compounds 4-6, 11, 20, 21, 26 were obtained from the Baran lab.[34] Compounds 10,[25] 14,[35] 16, 18,[36] 19,[37] 40/41,[38] were synthesized as reported previously.

4.1.2. General Procedure for Amide Couplings

To a 0.2 M solution of amine (0.1-10 mmol, 1 eq) and carboxylic acid (1 eq) in DCM was added Cl-HOBt (1.05 eq) and Et3N (1.3 eq) followed by EDC-HCl (1.2 eq). The mixture was stirred at r.t. for 12 h. The crude mixture was diluted with DCM and washed once with 1 M HCl, once with sat. NaHCO3 and once with brine. The DCM solution was evaporated to afford the product with >90% purity. The product was recrystallized from Et2O/hexane or purified by silica gel chromatography if necessary. Yields were typically >75%.

4.1.3. 5,8-Dioxo-5,8-dihydronaphthalen-1-yl cyclopentanecarboxylate (8)

Similar to previously reported procedure,[25] cyclopentoyl chloride (3 eq, 29 μL) was added to a solution of 7 (0.08 mmol, 14 mg) and DMAP (0.2 eq, 2 mg) in 200 μL pyridine/200 μL DCM. After stirring for 45 min, the reaction was diluted with 1N HCl and extracted with DCM. Purification by pTLC with 30% EtOAc in hexane afforded 8 as a yellow solid (12 mg, 55%).

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.04 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 6.84 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 3.22 – 3.09 (m, 1H), 2.19 – 2.05 (m, 4H), 1.90 – 1.76 (m, 2H), 1.76 – 1.63 (m, 2H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 184.44, 183.78, 174.96, 149.94, 140.11, 137.37, 134.83, 133.68, 130.00, 125.00, 123.74, 44.12, 30.00, 26.01.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 271.0965, obs. 271.0965.

4.1.4. 3-(3,6-Dioxocyclohexa-1,4-dien-1-yl)propanoic acid (16)

2,5-Dimethoxypropionic acid was oxidized via a previously reported procedure employing oxone and 4-iodophenoxyacetic acid to the benzoquinone 16 as an orange solid (12.9 mg, 55%) with pTLC (70% EtOAc in hexane). Characterization agreed with a previous report of 16.[39]

4.1.5 2-(3,6-Dioxocyclohexa-1,4-dien-1-yl)acetic acid (22)

2,5-Dimethoxyphenylacetic acid was oxidized via a previously reported procedure[40] employing oxone and 4-iodophenoxyacetic acid to the benzoquinone 22 as an orange solid (16.5 mg, 75%) without the need for a purification step.

1H NMR (600 MHz, MeOD) δ 6.83 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 6.80 – 6.78 (m, 1H), 6.76 – 6.75 (m, 1H), 3.47 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 2H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, MeOD) δ 188.90, 187.89, 173.10, 143.98, 137.68, 135.89, 35.55. ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 167.0339, obs. 167.0339.

4.1.6. 2-Amino-N-[3-(benzyloxy)phenyl]acetamide (27)

Compound 27 was prepared via the general amide coupling procedure with 3-benzyloxyaniline and Boc-Gly-OH to afford the Boc protected product as a white solid (3.2 g, 82%). Boc deprotection with 1:1 TFA/DCM over 30 min quantitatively produced 27 as a colorless oil.

1H NMR (600 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.43 – 7.40 (m, 2H), 7.38 – 7.34 (m, 3H), 7.31 – 7.28 (m, 1H), 7.22 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.11 – 7.08 (m, 1H), 6.79 – 6.75 (m, 1H), 5.07 (s, 2H), 3.83 (s, 2H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, MeOD) δ 165.43, 160.67, 140.27, 138.53, 130.77, 129.49, 128.89, 128.53, 113.36, 111.98, 107.89, 70.98, 42.14.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 257.1284, obs. 257.1284.

4.1.7. 2-Amino-N-(4-phenoxyphenyl)acetamide (28)

Compound 28 was prepared via the general amide coupling procedure with 4-phenoxyaniline and Boc-Gly-OH to afford the Boc protected product as a white solid (3.3 g, 89%) after recrystallization. Boc deprotection with 1:1 TFA/DCM over 30 min quantitatively produced 28 as a white solid.

1H NMR (600 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.58 – 7.55 (m, 2H), 7.35 – 7.30 (m, 2H), 7.08 (tt, J = 7.4, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 6.98 – 6.93 (m, 4H), 3.85 (s, 2H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, MeOD) δ 165.32, 158.89, 155.16, 134.66, 130.88, 124.28, 122.66, 120.36, 119.49, 42.04.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 243.1128, obs. 243.1128.

4.1.8. N-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-ylmethyl)-2-aminoacetamide (29)

Compound 29 was prepared via the general amide coupling procedure with 4-phenylbenzylamine and Boc-Gly-OH to afford the Boc protected product as a white solid (2.6 g, 83%) after recrystallization. Boc deprotection with 1:1 TFA/DCM over 30 min quantitatively produced 29 as a white solid.

1H NMR (600 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.59 – 7.56 (m, 3H), 7.44 – 7.37 (m, 5H), 7.34 – 7.30 (m, 1H), 4.47 (s, 2H), 3.73 (s, 2H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, MeOD) δ 165.76, 140.57, 140.31, 137.06, 128.49, 127.84, 127.00, 126.77, 126.48, 42.57, 40.13.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 241.1335, obs. 241.1335.

4.1.9. N-[3-(Benzyloxy)phenyl]-2-{[(3,6-dioxocyclohexa-1,4-dien-1-yl)methyl]amino}acetamide (30)

N-Boc-33 (14 mg, 0.027 mmol) was dissolved in 0.4 mL CHCl3, 0.8 mL MeCN and 0.2 mL H2O and cooled to 0 °C. CAN (2 eq, 27 mg) was gradually added, and the mixture was stirred for 2.5 h.[41] The mixture was diluted with water and extracted with DCM. The crude product was purified by pTLC with 40% EtOAc in hexane to afford the Boc protected product (4.7 mg, 36%). The Boc group was removed by stirring with 1:1 TFA/DCM over 30 min to quantitatively produce 30 as a yellow oil.

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.42 – 7.33 (m, 4H), 7.31 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 6.84 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 6.76 – 6.66 (m, 1H), 4.99 (s, 2H), 3.87 (s, 2H), 3.72 (s, 2H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 159.32, 153.94, 151.82, 136.91, 129.96, 128.69, 128.11, 127.68, 118.30, 117.56, 116.55, 112.83, 112.67, 111.90, 111.83, 106.76, 70.04, 56.10, 55.88.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 377.1496, obs. 377.1496.

4.1.10. 6-[(3,6-Dioxocyclohexa-1,4-dien-1-yl)amino]-N-(4-phenoxybenzyl)picolinamide (31)

Compound 34 (12 mg, 0.026 mmol) was dissolved in 30 μL MeOH, 30 μL MeCN and 400 μL H2O and cooled to 0 °C. PhI(OAc)2 (1.2 eq, 10.5 mg) was added gradually and the mixture was stirred for 1.5 h, allowing to warm to r.t. The reaction mixture was diluted with sat. NaHCO3 and extracted with EtOAc. Purification by pTLC with 70% EtOAc in hexane afforded 31 as a red solid (1.6 mg, 14%). (Adapted from a previously reported method) [42]

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.95 (dd, J = 7.6, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (brs, 1H), 7.39 – 7.36 (m, 2H), 7.33 – 7.30 (m, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (dd, J = 8.1, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (tt, J = 7.5, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.04 – 7.00 (m, 4H), 6.80 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (dd, J = 10.1, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 4.67 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 187.17, 183.31, 163.80, 157.37, 156.80, 151.19, 148.99, 139.81, 139.76, 139.09, 132.98, 132.94, 129.86, 129.42, 123.35, 119.47, 118.96, 117.67, 116.54, 107.97, 43.28.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 426.1448, obs. 426.1442.

4.1.11. N-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-ylmethyl)-1-[(3,6-dioxocyclohexa-1,4-dien-1-yl)methyl]-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide (32)

See preparation of 30 for details.

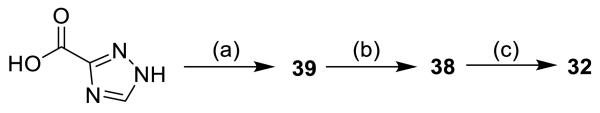

Compound 38 (7.2 mg, 0.017 mmol) was oxidized with 2 eq CAN over 8 h to produce 32 as a brown solid (0.6 mg, 9%).

Chemical instability precluded the acquisition of clean NMR spectra.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 399.1452, obs. 399.1455

4.1.12. N-[3-(Benzyloxy)phenyl]-2-[(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)amino]acetamide (33)

3-Benzyloxyaniline (80 mg, 0.40 mmol) was dissolved in DCM and cooled to 0 °C. Bromoacetyl bromide (2 eq, 70 μL) and Et3N (5 eq, 280 μL) were added slowly and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 6 h. 2,5-Dimethoxybenzylamine (2.5 eq, 151 μL) was added at 0 °C and the mixture was allowed to warm over 16 h of stirring. Boc2O (6 eq, 524 mg) was added along with 2 addition eq of Et3N and DMAP (0.2 eq, 10 mg) and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at r.t. The reaction mixture was diluted with sat. NaHCO3 and extracted with DCM. The crude product was purified by pTLC with 30% EtOAc in hexane to afford N-Boc-33 as a colorless oil (49 mg, 24%).

1H NMR w/ Boc (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.45 – 7.41 (m, 2H), 7.40 – 7.36 (m, 2H), 7.34 – 7.30 (m, 1H), 7.16 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.88 – 6.73 (m, 3H), 6.70 (dd, J = 8.2, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 5.04 (s, 2H), 4.55 (s, 2H), 3.98 (s, 2H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 3.74 (s, 3H), 1.45 (s, 9H).

13C NMR w/ Boc (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.41, 168.14, 159.25, 151.70, 136.91, 129.61, 128.55, 127.94, 127.49, 126.40, 111.99, 110.98, 106.13, 81.32, 69.94, 55.72, 52.90, 28.31, 20.49.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z) w/ Boc: [M+H]+ calc. 507.2490, obs. 507.2493

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z) no Boc: [M+H]+ calc. 407.1965, obs. 407.1966

4.1.13. 6-[(2,5-Dimethoxyphenyl)amino]-N-(4-phenoxybenzyl)picolinamide (34)

4-Phenoxybenzonitrile (200 mg, 1.00 mmol) was dissolved in 8 mL MeOH and 5% Pd/C (0.2 eq, 400 mg) was added. The reaction was stirred for 3 h under an H2 atmosphere and filtered through celite. Purification by pTLC with 10% MeOH, 2% Et3N in DCM afforded 4-phenoxybenzylamine as a white solid (179 mg, 88%). 42 (1.1 eq, 22 mg) was dissolved in toluene with 2,5-dimethoxyaniline (1 eq, 8 mg), BINAP (0.3 eq, 11 mg), Pd(OAc)2 (0.15 eq, 2 mg) and Cs2CO3 (2.5 eq, 46 mg) and the mixture was stirred for 15 h at 105 °C. The solvent was removed and the crude product was filtered through silica, eluting with EtOAc. Final purification by pTLC with 50% EtOAc in hexane afforded 34 as colorless oil (12.4 mg, 48%).

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.18 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (dd, J = 7.4, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.70 – 7.64 (m, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 7.38 – 7.29 (m, 4H), 7.13 – 7.07 (m, 1H), 7.03 – 6.95 (m, 6H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (dd, J = 8.8, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.64 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.67, 157.35, 156.70, 154.00, 153.88, 148.16, 143.13, 138.88, 133.33, 130.46, 129.88, 129.48, 123.38, 119.23, 118.95, 114.25, 113.48, 111.16, 105.76, 105.35, 56.37, 55.65, 43.03.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 456.1918, obs. 456.1919.

4.1.14. N-(4-phenoxybenzyl)picolinamide (35)

Compound 35 was prepared via the general amide coupling procedure in 1:1 DCM to DMF with 4-phenoxybenzylamine and picolinic acid to afford the product as a white solid (18 mg, 84%).

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.53 (ddd, J = 4.7, 1.7, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 8.37 (brs, 1H), 8.24 (dt, J = 7.8, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (td, J = 7.7, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (ddd, J = 7.6, 4.7, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.37 – 7.29 (m, 4H), 7.09 (tt, J = 7.5, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.03 – 6.95 (m, 4H), 4.65 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.35, 157.31, 156.75, 149.93, 148.22, 137.53, 133.21, 129.86, 129.48, 126.37, 123.40, 122.50, 119.21, 118.96, 43.06.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 305.1284, obs. 305.1287.

4.1.15. Methyl 6-[(3,6-dioxocyclohexa-1,4-dien-1-yl)amino]picolinate (36)

Compound 43 (Methyl 6-[(2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)amino]picolinate) was prepared via the same aryl amination reaction used to prepare 31. Methyl-6-bromopyridine-2-carboxylate was reacted with 2,5-dimethoxyaniline to afford 43 as a colorless oil (41 mg, 44%) which was subsequently used in the next reaction.

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.11 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 7.67 – 7.55 (m, 2H), 7.03 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.51 (dd, J = 8.8, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 3.97 (s, 3H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.84 (s, 3H).

Compound 43 was oxidized with PhI(OAc)2 to afford 36 as a red solid (2.0 mg, 22%). (See preparation of 31 for full conditions)

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.82 – 7.78 (m, 3H), 7.12 (dd, J = 7.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.79 – 6.74 (m, 2H), 4.02 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 187.89, 183.62, 165.51, 152.52, 146.70, 139.78, 139.14, 138.97, 132.87, 119.67, 116.95, 109.54, 53.16.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 259.0713, obs. 259.0714.

4.1.16. 2-(Pyridin-2-ylamino)cyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione (37)

See preparation of 31 for details.

Compound 44 was oxidized with PhI(OAc)2 to afford 37 as a red solid (3.2 mg, 26%).

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.41 – 8.35 (m, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (ddd, J = 8.3, 7.4, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (ddd, J = 7.3, 5.0, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 6.95 – 6.90 (m, 1H), 6.78 – 6.70 (m, 2H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 188.02, 183.84, 152.84, 148.45, 140.09, 139.19, 137.99, 132.82, 118.34, 113.59, 108.50.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 201.0659, obs. 201.0659.

4.1.17. N-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-ylmethyl)-1-(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide (38)

Compound 39 (11 mg, 0.040 mmol) was dissolved in 0.75 mL DMF and K2CO3 (2 eq, 11 mg) and 2,5-dimethoxybenzyl bromide (11 mg, 1.2 eq) were added (treatment of 2,5-dimethoxybenzyl alcohol with PBr3 afforded the corresponding benzyl bromide).[43] The reaction mixture was stirred at r.t. for 2.5 h and filtered. The crude product was purified by pTLC with 5% MeOH in DCM to afford 38 as a colorless oil (13.8 mg, 81%).

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.05 (s, 1H), 7.58 – 7.53 (m, 4H), 7.48 – 7.38 (m, 4H), 7.37 – 7.32 (m, 1H), 6.89 – 6.78 (m, 3H), 5.34 (s, 2H), 4.69 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 3.75 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 159.19, 156.88, 153.75, 151.50, 144.11, 140.85, 140.67, 137.03, 128.89, 128.54, 127.55, 127.43, 127.19, 122.96, 116.92, 115.26, 111.79, 55.89, 55.88, 49.77, 43.15.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 429.1921, obs.429.1923.

4.1.18. N-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-ylmethyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide (39)

Compound 39 was prepared via the general amide coupling procedure in DMF with 4-phenylbenzylamine and 1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxylic acid to afford the product which precipitated out of the reaction as a white solid (48 mg, 68%).

1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.85 (s, 1H), 8.46 – 8.43 (m, 2H), 8.43 – 8.40 (m, 2H), 8.28 – 8.24 (m, 2H), 8.21 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 8.17 – 8.14 (m, 1H), 5.28 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 140.01, 138.84, 138.69, 128.90, 127.91, 127.30, 126.57, 41.74.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 279.1240, obs. 279.1240.

4.1.19. 6-Bromo-N-(4-phenoxybenzyl)picolinamide (42)

Compound 42 was prepared via the general amide coupling procedure with 4-phenoxybenzylamine and 6-bromopicolinic acid to afford the product as a colorless oil (73 mg, 76%).

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.21 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (s, 1H), 7.74 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.37 – 7.32 (m, 4H), 7.12 (tt, J = 7.4, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.06 – 6.97 (m, 4H), 4.65 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.85, 157.20, 156.84, 151.01, 140.68, 139.81, 132.83, 130.91, 129.86, 129.51, 123.43, 121.56, 119.14, 118.99, 43.10.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 383.0390, obs. 383.0391.

4.1.20. N-(2,5-Dimethoxyphenyl)pyridin-2-amine (44)

Compound 44 was prepared via the same aryl amination reaction used to prepare 31. 2-Bromopyridine was reacted with 2,5-dimethoxyaniline to afford 44 as a colorless oil (20 mg, 40%).

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.27 – 8.23 (m, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H), 7.53 – 7.47 (m, 1H), 7.02 (s, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.76 – 6.72 (m, 1H), 6.45 (dd, J = 8.8, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.80 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.42, 154.10, 148.25, 142.87, 137.49, 131.38, 115.21, 110.92, 110.13, 105.15, 104.72, 56.40, 55.83.

ESI-TOF-MS (m/z): [M+H]+ calc. 231.1128, obs. 231.1130.

4.2. Enzyme Assays

4.2.1. SNAPtide Assay[44]

Recombinant 425aa BoNT/A LC was used throughout all assays and was prepared as previously described.[45] All SNAPtide assays were run in 40 mM HEPES + 0.1% Triton X-100 at pH 7.4. BoNT/A LC concentrations were 18.5 nM while SNAPtide (prod. no. 521, List Labs) concentrations were 5 μM. Fluorescence was recorded continuously for 1.5 h to calculate an accurate kobs using equation 1. In the preincubation experiments, inhibitors at the specified concentrations were incubated with 925 nM enzyme and diluted 50-fold into substrate and initial rates of SNAPtide cleavage were measured.

| (1) |

IC50 values for Figure 9 were calculated using equation 2.

| (2) |

4.2.2. Glutathione Reactivity Assay

1 mM glutathione and 1 mM BQ compound were incubated in PBS (Fisher Bioreagents) + 1 mM EDTA buffer at pH 7.4. At certain time points, the reaction solution was diluted 1:10 into a 4 mg/mL DTNB solution and the absorbance was measured at 412 nm. Appropriate blanks were used to account for potential absorbance by the BQ compounds. A standard curve was run alongside the assay using [GSH] = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25 mM. Equation 3 was used to calculate the second order rate constant (kGSH) of Michael adduct formation.

| (3) |

4.2.3. 66-mer Assay[31]

All 66-mer assays were run in 40 mM HEPES pH 7.4. BoNT/A LC concentrations were 0.8 nM, 66-mer substrate (prepared in-house via solid phase synthesis) concentrations were 5 μM. Inhibitors were tested at 50 μM and substrate cleavage was allowed to occur for 25 min at which point the reaction was quenched with 20% TFA solution. A 13C labelled 9-mer cleavage product was added as an internal standard (IS) and each sample was analyzed by LCMS to quantify the amount of cleavage product relative to the IS. Initial velocities were used to calculate IC50 values from equation 4 (a rearranged form of equation 2). In the preincubation experiments, inhibitors at 50 μM of inhibitor was incubated with 40 nM enzyme and diluted 50-fold into substrate and initial rates of 66-mer cleavage were measured. Redetermination of competitive inhibitor IC50 values with a different batch of 66-mer substrate yielded up to a 2-10 fold increase in relative IC50 values, however this result does not affect the SAR or conclusions herein.

| (4) |

4.2.4. Regression Analysis

All curve-fitting was performed in GraphPad PRISM version 6 using equations 1-4 and standard linear and exponential regressions.

4.2.5. Computational Studies

A previously used computational model and scoring function[10] derived from the Autocorrelator program[46] was used for docking studies. OMEGA v2.4.6 was used to generate lowest energy conformers of query molecules and FRED was used to dock these conformers into 2IMB and 4ELC co-crystal structure of BoNT/A LC.[47]

Figure 10.

Synthesis of 30

(a) bromoacetyl bromide, Et3N, DCM, 0 °C; (b) 2,5-dimethoxybenzylamine, 0 °C-r.t.; (c) Boc2O, Et3N, cat. DMAP, DCM, 24% (3 steps); (d) CAN, MeCN/H2O; (e) TFA, DCM, 36% (2 steps).

Figure 11.

Synthesis of 31 and related compounds

(a) H2, Pd/C, 88%; (b) 6-bromopicolinic acid, EDC, Cl-HOBt, Et3N, DCM 76%; (c) 2,5-dimethoxyaniline, BINAP, Pd(OAc)2, Cs2CO3, toluene, 40-50%; (d) PhI(AcO)2, MeOH/H2O, 14-26%.

Figure 12.

Synthesis of 32

(a) 4-phenylbenzylamine, EDC, Cl-HOBt, Et3N, DMF, 68%; (b) 2,5-dimethoxybenzyl bromide, K2CO3, DMF, 81%; (c) CAN, 9%.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the NIH for funding under grant 5R01AI080671-05 and 1F31DA037709-01, Dr. Peter Silhar for proposing juglone as an inhibitor, Professor Phil Baran and his research group for providing the noted BQ compounds, Dr. Matthew Lardy for his assistance with docking studies and Greg McElhaney and Jing Yu for synthesis of aminoacetamides.

References

- [1].Arnon SS, Schechter R, Inglesby TV, et al. Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: Medical and public health management. JAMA. 2001;285:1059–1070. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Schantz EJ, Johnson EA. Properties and Use of Botulinum Toxin and Other Microbial Neurotoxins in Medicine. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:80–99. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.80-99.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jankovic J. Botulinum toxin in clinical practice. J Neurol Neurosur Ps. 2004;75:951–957. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.034702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hanson D. [accessed March 2014];Botulinum Toxin: A Bioterrorism Weapon, 2004. http://www.emsworld.com/article/10324792/botulinum-toxin-a-bioterrorism-weapon.

- [5].Willis B, Eubanks LM, Dickerson TJ, Janda KD. The strange case of the botulinum neurotoxin: using chemistry and biology to modulate the most deadly poison. ACIE. 2008;47:8360–8379. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Simpson LI. The binary toxin produced by Clostridium botulinum enters cells by receptor-mediated endocytosis to exert its pharmacologic effects. JPET. 1989;251:1223–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Blasi J, Chapman ER, Link E, Binz T, Yamasaki S, De Camilli P, Sudhof TC, Niemann H, Jahn R. Botulinum neurotoxin A selectively cleaves the synaptic protein SNAP-25. Nature. 1993;365:160–163. doi: 10.1038/365160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Boldt GE, Kennedy JP, Janda KD. Identification of a potent botulinum neurotoxin a protease inhibitor using in situ lead identification chemistry. Org Lett. 2006;8:1729–1732. doi: 10.1021/ol0603211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kumaran D, Rawat R, Ludivico ML, Ahmed SA, Swaminathan S. Structure- and substrate-based inhibitor design for Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. JBC. 2008;283:18883–18891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801240200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Silhar P, Silvaggi NR, Pellett S, Capkova K, Johnson EA, Allen KN, Janda KD. Evaluation of adamantane hydroxamates as botulinum neurotoxin inhibitors: Synthesis, crystallography, modeling, kinetic and cellular based studies. BMC. 2013;21:1344–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Silhar P, Capkova K, Salzameda NT, Barbieri JT, Hixon MS, Janda KD. Botulinum Neurotoxin A Protease: Discovery of Natural Product Exosite Inhibitors. JACS. 2010;132:2868. doi: 10.1021/ja910761y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Li B, Cardinale SC, Butler MM, Pai R, Nuss JE, Peet NP, Bavari S, Bowlin TL. Time-dependent botulinum neurotoxin serotype A metalloprotease inhibitors. BMC. 2011;19:7338–7348. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Capkova K, Hixon MS, Pellett S, Barbieri JT, Johnson EA, Janda KD. Benzylidene cyclopentenediones: First irreversible inhibitors against botulinum neurotoxin A’s zinc endopeptidase. BMCL. 2010;20:206–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.10.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stura EA, Le Roux L, Guitot K, Garcia S, Bregant S, Beau F, Vera L, Collet G, Ptchelkine D, Bakirci H, Dive V. Structural Framework for Covalent Inhibition of Clostridium botulinum Neurotoxin A by Targeting Cys165. JBC. 2012;287:33607–33614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.396697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Foran PG, Mohammed N, Lisk GO, Nagwaney S, Lawrence GW, Johnson E, Smith L, Aoki KR, Dolly JO. Evaluation of the therapeutic usefulness of botulinum neurotoxin B, C1, E, and F compared with the long lasting type A - Basis for distinct durations of inhibition of exocytosis in central neurons. JBC. 2003;278:1363–1371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Papageorgiou VP, Assimopoulou AN, Couladouros EA, Hepworth D, Nicolaou KC. The chemistry and biology of alkannin, shikonin, and related naphthazarin natural products. ACIE. 1999;38:270–301. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990201)38:3<270::AID-ANIE270>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dandawate PR, Vyas AC, Padhye SB, Singh MW, Baruah JB. Perspectives on Medicinal Properties of Benzoquinone Compounds. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2010;10:436–454. doi: 10.2174/138955710791330909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kleyer DL, Koch TH. Mechanistic Investigation of Reduction of Daunomycin and 7-Deoxydaunomycinone with Bi(3,5,5-Trimethyl-2-Oxomorpholin-3-Yl) JACS. 1984;106:2380–2387. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ollinger K, Brunmark A. Effect of Hydroxy Substituent Position on 1,4-Naphthoquinone Toxicity to Rat Hepatocytes. JBC. 1991;266:21496–21503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Littarru GP, Tiano L. Bioenergetic and antioxidant properties of coenzyme Q(10): Recent developments. Mol Biotechnol. 2007;37:31–37. doi: 10.1007/s12033-007-0052-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stocker R, Bowry VW, Frei B. Ubiquinol-10 Protects Human Low-Density-Lipoprotein More Efficiently against Lipid-Peroxidation Than Does Alpha-Tocopherol. PNAS. 1991;88:1646–1650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wissner A, Floyd MB, Johnson BD, Fraser H, Ingalls C, Nittoli T, Dushin RG, Discafani C, Nilakantan R, Marini J, Ravi M, Cheung K, Tan X, Musto S, Annable T, Siegel MM, Loganzo F. 2-(Quinazolin-4-ylamino)-[1,4]benzoquinones as covalent-binding, irreversible inhibitors of the kinase domain of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7560–7581. doi: 10.1021/jm050559f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wissner A, Fraser HL, Ingalls CL, Dushin RG, Floyd MB, Cheung K, Nittoli T, Ravi MR, Tan XZ, Loganzo F. Dual irreversible kinase inhibitors: Quinazoline-based inhibitors incorporating two independent reactive centers with each targeting different cysteine residues in the kinase domains of EGFR and VEGFR-2. BMC. 2007;15:3635–3648. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boldt GE, Kennedy JP, Hixon MS, McAllister LA, Barbieri JT, Tzipori S, Janda KD. Synthesis, characterization and development of a high-throughput methodology for the discovery of botulinum neurotoxin a inhibitors. J Comb Chem. 2006;8:513–521. doi: 10.1021/cc060010h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Maruo S, Kuriyama I, Kuramochi K, Tsubaki K, Yoshida H, Mizushina Y. Inhibitory effect of novel 5-O-acyl juglones on mammalian DNA polymerase activity, cancer cell growth and inflammatory response. BMC. 2011;19:5803–5812. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wissner A, Overbeek E, Reich MF, Floyd MB, Johnson BD, Mamuya N, Rosfjord EC, Discafani C, Davis R, Shi X, Rabindran SK, Gruber BC, Ye F, Hallett WA, Nilakantan R, Shen R, Wang YF, Greenberger LM, Tsou HR. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 6,7-disubstituted 4-anilinoquinoline-3-carbonitriles. The design of an orally active, irreversible inhibitor of the tyrosine kinase activity of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) J Med Chem. 2003;46:49–63. doi: 10.1021/jm020241c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gan JP, Harper TW, Hsueh MM, Qu QL, Humphreys WG. Dansyl glutathione as a trapping agent for the quantitative estimation and identification of reactive metabolites. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:896–903. doi: 10.1021/tx0496791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Dasmahapatra G, Patel H, Dent P, Fisher RI, Friedberg J, Grant S. The Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor PCI-32765 synergistically increases proteasome inhibitor activity in diffuse large-B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) cells sensitive or resistant to bortezomib. British Journal of Haematology. 2013;161:43–56. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- [29].Honigberg LA, Smith AM, Sirisawad M, Verner E, Loury D, Chang B, Li S, Pan Z, Thamm DH, Miller RA, Buggy JJ. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 blocks B-cell activation and is efficacious in models of autoimmune disease and B-cell malignancy. PNAS. 2010;107:13075–13080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004594107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ponader S, Chen SS, Buggy JJ, Balakrishnan K, Gandhi V, Wierda WG, Keating MJ, O’Brien S, Chiorazzi N, Burger JA. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 thwarts chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell survival and tissue homing in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2012;119:1182–1189. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-386417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Capkova K, Hixon MS, McAllister LA, Janda KD. Toward the discovery of potent inhibitors of botulinum neurotoxin A: development of a robust LC MS based assay operational from low to subnanomolar enzyme concentrations. Chem Comm. 2008:3525–3527. doi: 10.1039/b808305c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Breidenbach MA, Brunger AT. Substrate recognition strategy for botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. Nature. 2004;432:925–929. doi: 10.1038/nature03123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Silhar P, Lardy MA, Hixon MS, Shoemaker CB, Barbieri JT, Struss AK, Lively JM, Javor S, Janda KD. C-Terminus of Botulinum A Protease Has Profound and Unanticipated Kinetic Consequences upon the Catalytic Cleft. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:283–287. doi: 10.1021/ml300428s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fujiwara Y, Domingo V, Seiple IB, Gianatassio R, Del Bel M, Baran PS. Practical C-H Functionalization of Quinones with Boronic Acids. JACS. 2011;133:3292–3295. doi: 10.1021/ja111152z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Brimble MA, Brenstrum TJ. Synthesis of a 2-deoxyglucosyl analogue of medermycin. J Chem Soc Perk T. 2001;1:1624–1634. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Contant P, Haess M, Riegl J, Scalone M, Visnick M. Synthesis of racemic frenolicin B and 5-epifrenolicin B via intramolecular palladium-catalyzed aryloxycarbonylation. Synthesis. 1999:821–828. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ameer F, Green IR, Krohn K, Sitoza M. Strategies towards the synthesis of 6-N,N-diethylcarbamyloxy-1,4-dimethoxy-7-naphthylboronic acid. Synthetic Commun. 2007;37:3041–3057. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Eriksson J, Aberg O, Langstrom B. Synthesis of [C-11]/[C-13]acrylamides by palladium-mediated carbonylation. Eur J Org Chem. 2007:455–461. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Eipert M, Maichle-Mossmer C, Maier ME. Acid-induced rearrangement reactions of reduced benzoquinone cyclopentadiene cycloadducts. J Org Chem. 2002;67:8692–8695. doi: 10.1021/jo026238i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yakura T, Omoto M, Yamauchi Y, Tian Y, Ozono A. Hypervalent iodine oxidation of phenol derivatives using a catalytic amount of 4-iodophenoxyacetic acid and Oxone (R) as a co-oxidant. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:5833–5840. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Jacob P, 3rd, Callery PS, Shulgin AT, Castagnoli N., Jr. A convenient synthesis of quinones from hydroquinone dimethyl ethers. Oxidative demethylation with ceric ammonium nitrate. J Org Chem. 1976;41:3627–3629. doi: 10.1021/jo00884a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nawrat CC, Lewis W, Moody CJ. Synthesis of Amino-1,4-benzoquinones and Their Use in Diels-Alder Approaches to the Aminonaphthoquinone Antibiotics. J Org Chem. 2011;76:7872–7881. doi: 10.1021/jo201320g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ma YJ, Zhang ZB, Ji XF, Han CY, He JM, Abliz Z, Chen WX, Huang FH. Preparation of Pillar[n]arenes by Cyclooligomerization of 2,5-Dialkoxybenzyl Alcohols or 2,5-Dialkoxybenzyl Bromides. Eur J Org Chem. 2011:5331–5335. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Boldt GE, Kennedy JP, Hixon MS, McAllister LA, Barbieri JT, Tzipori S, Janda KD. Synthesis, characterization and development of a high-throughput methodology for the discovery of botulinum neurotoxin A inhibitors. J Comb Chem. 2006;8:513–521. doi: 10.1021/cc060010h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Eubanks LM, Hixon MS, Jin W, Hong S, Clancy CM, Tepp WH, Baldwin MR, Malizio CJ, Goodnough MC, Barbieri JT, Johnson EA, Boger DL, Dickerson TJ, Janda KD. An in vitro and in vivo disconnect uncovered through high-throughput identification of botulinum neurotoxin A antagonists. PNAS. 2007;104:2602–2607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611213104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lardy MA, LeBrun L, Bullard D, Kissinger C, Gobbi A. Building a Three-Dimensional Model of CYP2C9 Inhibition Using the Autocorrelator: An Autonomous Model Generator. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 2012;52:1328–1336. doi: 10.1021/ci200558e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].OMEGA, ROCS, FRED, and SZYBKI are distributed by OpenEye Scientific Software. Santa Fe, NM: [accessed May 2012]. The OEChem Toolkit. http://www.eyesopen.com. [Google Scholar]