Abstract

Background

Intragenic deletions of the dystrophin-encoding and muscular dystrophy-associated DMD gene have been recently described in gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) and leiomyosarcoma (LMS). We evaluated the copy numbers and gene expression levels of DMD in our series of GIST patients who were already studied with wide genome assays, to investigate more fully a correlation between dystrophin status and disease annotations.

Findings

Our study highlighted a recurrent intragenic deletion on chromosome X, involving the DMD gene that codes for human dystrophin in GIST patients. Of 29 KIT/PDGFRA mutant GIST samples, 9 (31%) showed deletions of the DMD gene, which were focal and intragenic in 8 cases, and involved loss of an entire chromosome in one case (GIST_188). DMD loss was seen in only 5 patients with metastasis, whereas 18 out of 20 patients with localized disease had wild-type DMD (P = 0.0004, Fisher exact test). None of the 6 KIT/PDGFRA WT GIST showed DMD alterations.

Conclusions

Our study confirms the presence of DMD deletions only in KIT/PDGFRA mutant GIST and this event is almost associated with metastatic disease. These findings are, of course, quite preliminary but support development of potential therapeutic strategies that target and restore DMD function in the treatment of metastatic GIST.

Keywords: Dystrophin, DMD, Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, KIT/PDGFRA wild type

Findings

Intragenic deletions of the dystrophin-encoding and muscular dystrophy-associated DMD gene have been recently described in many common human mesenchymal tumors, including gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) and leiomyosarcoma (LMS) which show myogenic differentiation [1]. In particular, DMD deletions were found in 19 of 29 GIST tumors, 3 of 4 RMS tumors and 3 of 7 LMS tumors. Moreover, DMD deletions and their protein expression were not found in non-myogenic cancers, or in benign counterparts of GIST, RMS and LMS. In GIST, dystrophin is downregulated in metastatic GIST and primary high-risk GIST, but not in low-risk GIST, which implies this downregulation is a late event in progression of this disease. Finally, dystrophin inhibits myogenic sarcoma cell migration, invasion, anchorage independence and invadopodia formation; and when deregulated, dystrophin restoration inhibits invasiveness and migration in sarcoma cell lines. These data validate dystrophin as a tumor suppressor and likely anti-metastatic factor. In light of these findings, we evaluated DMD copy number and gene expression levels in our series of GIST patients who had already been studied with wide genome assays, to investigate more fully the correlation between dystrophin status and disease annotations.

Patient selection and tumor sample collection

Dystrophin status was evaluated using already-available data from wide genome assays done on tumor specimens collected during surgery and immediately frozen. We included samples from 29 patients with mutant KIT/PDGFRA GIST and 6 with wild-type (WT) KIT/PDGFRA GIST. Among the KIT/PDGFRA WT GIST group, 4 cases were SDH deficient and 2 cases were quadruple KIT/PDGFRA/SDH/BRAF-KRAS-NF1 WT. Out of all 35 patients, 19 had already been reported [2]. Table 1 shows patients’ clinical and molecular data. The genomic analysis study was approved by local Ethical Committee.

Table 1.

Clinical and molecular data of the patients included in the study

| ID | Sex | Age | DMD | Start | End | Site | Disease status | KIT/PDGFRA Mutational status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

GIST_18 |

M |

NA |

loss |

ex2 |

ex7 |

NA |

NA |

KIT exon 11 V559G |

|

GIST_20 |

M |

38 |

loss |

ex2 |

Small intestine |

Metastatic |

KIT exon 11 del MYEQW552–557 Z; |

|

|

ex8 |

ex17 |

KIT exon 18 A829P |

||||||

|

GIST_22 |

F |

76 |

loss |

ex1 |

ex44 |

Stomach |

NA |

PDGFRA exon 18 D842V |

|

GIST_25 |

M |

84 |

loss |

ex1 |

ex17 |

NA |

NA |

KIT exon 11 del WKV557–559 F |

|

GIST_26 |

M |

49 |

loss |

ex1 |

ex11 |

Stomach |

Metastatic |

PDGFRA exon 12 V561D |

|

GIST_27 |

M |

52 |

loss |

ex1 |

NA |

NA |

KIT exon 11 del KV558-559 N |

|

|

GIST_131 |

M |

58 |

loss |

ex3 |

ex7 |

Small intestine |

Metastatic |

KIT exon 11 del V569_Y578 |

|

GIST_174 |

M |

59 |

loss |

ex1 |

ex7 |

Stomach |

Metastatic |

KIT exon 11 L576P |

|

GIST_188 |

F |

57 |

loss |

All chromosome |

Small intestine |

Metastatic |

KIT exon 11 N564_L576del; KIT exon 17 p.N822K |

|

| GIST_02 |

F |

85 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 11 V560D |

| GIST_04 |

M |

79 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 9 ins AY502–503 |

| GIST_05 |

M |

68 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

PDGFRA exon 12 ins/del SPDGHE566–571RIQ |

| GIST_08 |

M |

62 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 11 V559D |

| GIST_09 |

M |

54 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 11 ins TQLPYDHKWEFP574–585 at P585 |

| GIST_11 |

M |

65 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 11 del WK557–558 |

| GIST_12 |

F |

66 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

PDGFRA exon 14 K646E |

| GIST_13 |

M |

46 |

wt |

- |

- |

Small intestine |

Localized |

KIT exon 11 V559D |

| GIST_14 |

M |

56 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Metastatic |

KIT exon 11 hom. del WK557–558 |

| GIST_15 |

F |

64 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

PDGFRA exon 18 del DIMH842-845 |

| GIST_16 |

F |

62 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 11 L576P |

| GIST_121 |

M |

72 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 11 V559D |

| GIST_124 |

M |

72 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 11 ins 1765–1766 |

| GIST_125 |

F |

49 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 11 W557R |

| GIST_129 |

M |

60 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 11 del/ins Y553–V559L |

| GIST_130 |

F |

79 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 9 ins A502_Y503 |

| GIST_134 |

F |

65 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 11 homoz. V559D |

| GIST_135 |

F |

60 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

KIT exon 11 del W557_E561 |

| GIST_136 |

M |

76 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Localized |

PDGFRA exon 18 D842V |

| GIST_150 |

F |

56 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Metastatic |

KIT exon 11 P551_E554del |

| GIST_07 |

F |

27 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Metastatic |

KIT/PDGFRA wild-type (SDH deficient) |

| GIST_10 |

M |

29 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Metastatic |

KIT/PDGFRA wild-type (SDH deficient) |

| GIST_21 |

F |

25 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

NA |

KIT/PDGFRA wild-type (SDH deficient) |

| GIST_24 |

F |

18 |

wt |

- |

- |

Stomach |

Metastatic |

KIT/PDGFRA wild-type (SDH deficient) |

| GIST_127 |

F |

63 |

wt |

- |

- |

Ileum |

Localized |

Quadruple wild-type (KIT/PDGFRA/SDH/BRAF-KRAS-NF1 wild-type). |

| GIST_133 | M | 57 | wt | - | - | Duodenum | Localized | Quadruple wild-type (KIT/PDGFRA/SDH/BRAF-KRAS-NF1 wild-type). |

Patients with DMD loss are shown in bold.

Copy number analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted with QiaAmp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Milan, Italy), labelled and hybridized to SNP array Genome Wide SNP 6.0 (Affymetrix) following manufacturer’s instructions. Quality control was performed by Contrast QC and MAPD calculation. Copy number analysis was performed by Genotyping Console and visualized with Chromosome Analysis Suite Software (Affymetrix). Hidden Markov Model algorithm was used to detect amplified and deleted segments.

RNA sequencing

Whole-transcriptome sequencing was performed on RNA isolated from fresh-frozen tumor tissue with the RNeasy spin-column method (Qiagen). Whole-transcriptome RNA libraries were prepared in accordance with Illumina’s TruSeq RNA Sample Prep v2 protocol (Illumina, San Diego, California). Paired-end libraries were sequenced at 2 × 75bp read length using Illumina Sequencing by synthesis (SBS) technology. Averages of 85 million reads per sample were analyzed. Mapping on the human reference genome was done with TopHat/BowTie software, while expression level of the DMD gene was expressed as number of mapped reads.

Results and discussion

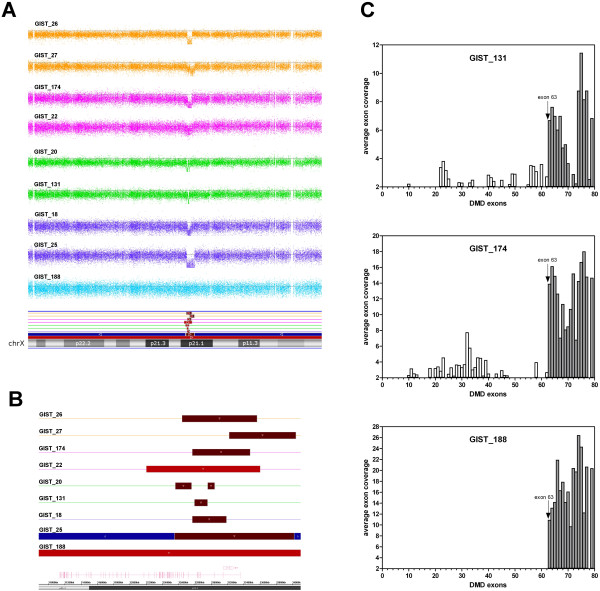

The genome-wide analysis of our series highlighted a recurrent intragenic deletion on chromosome X for the DMD gene, which codes for human dystrophin. Nine of the 29 KIT/PDGFRA mutant GIST (31%) showed DMD gene deletions (Figure 1A), which were focal and intragenic in 8 cases, and involved loss of a whole chromosome in one case (GIST_188; Figure 1B). None of the 6 KIT/PDGFRA WT GIST samples had DMD alterations.

Figure 1.

DMD deletions and gene expression in KIT/PDGFRA mutant IST samples. (A) Signal Log2 Ratio of copy number data from SNP 6.0 arrays on the X chromosome, showing focal losses and deletion of 1 entire chromosome arm. (B) Graphical representation of sizes of the genomic losses of DMD gene, located on the reverse X chromosome strand. (C) DMD expression showed as average number of mapped reads from RNA sequencing of the samples that carry DMD deletions. All cases retain the expression of the short isoform starting from exon 63.

As DMD is an X-linked gene, deletions were nullizygous in males and heterozygous in females. All focal events involved the 5′ portion of the gene, with the region between exon 2 and exon 7 as the most recurrently involved, and an average deletion size of 770 Mb.

RNA-sequencing performed on 3 out of 9 cases with deletions showed that the genomic losses abrogated expression of the largest DMD transcript, while preserving expression of the short isoform, with a transcription start site at exon 63 (Figure 1C).

Patients with KIT/PDGFRA mutant GIST tended to have higher frequency of DMD deletions in more advanced cases, as DMD loss was seen only in the 5 patients with metastasis, whereas 18 out of the 20 patients with localized disease wild-type DMD (Table 1; P = 0.0004, Fisher exact test).

Our study confirms the presence of DMD deletions in KIT/PDGFRA mutant GIST. In particular we also observed that this molecular event is associated with more advanced clinical disease such as metastatic tumors. Although these findings are quite preliminary they suggest potential therapeutic strategies that target and restore DMD function in treating metastatic GIST. Larger studies are necessary to correlate DMD status and specific mutations of KIT/PDGFRA receptors to explore novel therapies for GIST that present primary resistance or that initially responds to imatinib but later progresses [3]. As is well known, molecular mechanisms of secondary resistance are various and heterogeneous, the most common being the acquisition of secondary KIT/PDGFRA mutations or selection of sub-clones with resistant mutations [4]. In our series, of 7 patients who presented primary mutations in KIT exon 11, 2 also had secondary mutations, in KIT exon 17 or KIT exon 18. The 2 patients with mutations in PDGFRA had them in exon 18 D842V or exon 12. The small series does not permit any conclusive considerations on the correlation of DMD involvement with KIT/PDGFRA kinase genotype. But as the clinical use of sunitinib and regorafenib after imatinib failure does not completely cover the molecular landscape of the progressing GIST, a novel approach that targets dystrophin deregulation may have relevance in GIST treatment. Moreover, compared with KIT/PDGFRA mutant GIST, in our series all patients with KIT/PDGFRA WT GIST—including 4 who were SDH deficient and 2 who had quadruple KIT/PDGFRA/SDH/BRAF-KRAS-NF1 WT did not present dystrophin deregulation, even those with metastasis, which confirms once again that KIT/PDGFRA WT GIST should be considered a distinct disease in molecular background and clinical presentation [5].

Conclusion

In conclusion, deregulation of dystrophin seems to be associated with GIST progression and more data should be accumulated in order to define it as a therapeutic target.

Abbreviations

DMD: Dystrophin-encoding and muscular dystrophy-associated; GIST: Gastrointestinal stromal tumors; LMS: Leiomyosarcoma; RMS: Rhabdomyosarcoma.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PAM conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and drafted the manuscript. AA and UM carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the sequence alignment and drafted the manuscript. FF and IV participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. SM, NM, LC and EG participated in the analysis and interpretation of data. SD carried out the molecular genetic studies. BG, PAD and BG revised the study critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Maria A Pantaleo, Email: maria.pantaleo@unibo.it.

Annalisa Astolfi, Email: annalisa.astolfi@unibo.it.

Milena Urbini, Email: milena.urbini@yahoo.com.

Fabio Fuligni, Email: Fabio.fuligni2@unibo.it.

Maristella Saponara, Email: maristellasaponara@yahoo.it.

Margherita Nannini, Email: margherita.nannini@gmail.com.

Cristian Lolli, Email: cristian_lolli@libero.it.

Valentina Indio, Email: valentina.indio2@unibo.it.

Donatella Santini, Email: donatella.santini@aosp.bo.it.

Giorgio Ercolani, Email: giorgio.ercolani@aosp.bo.it.

Giovanni Brandi, Email: giovanni.brandi@unibo.it.

Antonio D Pinna, Email: antonio.pinna@aosp.bo.it.

Guido Biasco, Email: guido.biasco@unibo.it.

Acknowledgement

The present study was supported by AIRC, My First Grant 2013.

References

- Wang Y, Marino-Enriquez A, Bennett RR, Zhu M, Shen Y, Eilers G, Lee JC, Henze J, Fletcher BS, Gu Z, Fox EA, Antonescu CR, Fletcher CD, Guo X, Raut CP, Demetri GD, van de Rijn M, Ordog T, Kunkel LM, Fletcher JA. Dystrophin is a tumor suppressor in human cancers with myogenic programs. Nat Genet. 2014;46:601–606. doi: 10.1038/ng.2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astolfi A, Nannini M, Pantaleo MA, Di Battista M, Heinrich MC, Santini D, Catena F, Corless CL, Maleddu A, Saponara M, Lolli C, Di Scioscio V, Formica S, Biasco G. A molecular portrait of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an integrative analysis of gene expression profiling and high-resolution genomic copy number. Lab Invest. 2010;90:1285–1294. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Blanke CD, Demetri GD, Joensuu H, Roberts PJ, Eisenberg BL, von Mehren M, Fletcher CD, Sandau K, McDougall K, Ou WB, Chen CJ, Fletcher JA. Molecular correlates of imatinib resistance in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4764–4774. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liegl B, Kepten I, Le C, Demetri GD, Heinrich MC, Fletcher CDM, Corless CL, Fletcher JA. Heterogeneity of kinase inhibitor resistance mechanisms in GIST. J Pathol. 2008;216:64–74. doi: 10.1002/path.2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nannini M, Biasco G, Astolfi A, Pantaleo MA. An overview on molecular biology of KIT/PDGFRA wild type (WTWT) gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST) J Med Genet. 2013;50:653–661. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]