Abstract

AIM: To investigate the beneficial effect of the combination of butyrate, Lactobacillus casei, and L-carnitine in a rat colitis model.

METHODS: Rats were divided into seven groups. Four groups received oral butyrate, L-carnitine, Lactobacillus casei and the combination of three agents for 10 consecutive days. The remaining groups included negative and positive controls and a sham group. Macroscopic, histopathological examinations, and biomarkers such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interlukin-1β (IL-1β), myeloperoxidase (MPO), thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), and ferric reduced ability of plasma (FRAP) were determined in the colon.

RESULTS: The combination therapy exhibited a significant beneficial effect in alleviation of colitis compared to controls. Overall changes in reduction of TNF-α (114.66 ± 18.26 vs 171.78 ± 9.48 pg/mg protein, P < 0.05), IL-1β (24.9 ± 1.07 vs 33.06 ± 2.16 pg/mg protein, P < 0.05), TBARS (0.2 ± 0.03 vs 0.49 ± 0.04 μg/mg protein, P < 0.01), MPO (15.32 ± 0.4 vs 27.24 ± 3.84 U/mg protein, P < 0.05), and elevation of FRAP (23.46 ± 1.2 vs 15.02 ± 2.37 μmol/L, P < 0.05) support the preference of the combination therapy in comparison to controls. Although the monotherapies were also effective in improvement of colitis markers, the combination therapy was much better in improvement of colon oxidative stress markers including FRAP, TBARS, and MPO.

CONCLUSION: The present combination is a suitable mixture in control of experimental colitis and should be trialed in the clinical setting.

Keywords: Butyrate, L-carnitine, Colitis, Inflammatory bowel disease, Oxidative stress, Lactobacillus casei, Probiotic

Core tip: Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is among the common diseases in the world that have no absolute cure yet. Although corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and aminosalicylates are conventionally used in management of IBD, their side effects reduce patients’ compliance. In this paper, we have shown that the combination of butyrate, Lactobacillus casei, and, L-carnitine reduces the amount of oxidative stress within the colon and provides significant anti-inflammatory effects. Optimistically, the proposed combination is from components with no serious side effects and is more economical to manufacture.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease, has an increasing incidence and can be debilitating in the affected patients. Patients with IBD usually suffer from bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and also extra-gastrointestinal manifestations such as uveitis, arthritis, skin lesions, and hepatobiliary disease[1-3]. Although the definite etiology of IBD remains debatable, the role of immune dysfunction, particularly over-activity of inflammatory factors including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interlukin-1β (IL-1β), and oxidants such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) has been defined along with other factors such as environment, genetics, and intestinal microbes[4,5]. Current protocol of IBD treatment consists of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) derivatives, immuno-suppressive agents, corticosteroids, monoclonal antibodies, and some other complementary agents such as herbal medicines. However, increasing complications of conventional medications besides decreased patients compliance have led scientists to focus on the safety alongside efficacy[6-9].

Butyrate, a type of short chain fatty acid, is produced naturally by bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers as a fuel in the colon. Previous reports emphasized its protective ability against oxidative stress and depletion of inflammatory markers including TNF-α and IL-1β through interfering with Ikappa B kinase (IKK) and resulting in down-regulation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) which is responsible for generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines[10-13]. In addition, Lactobacillus casei (L. casei) as a probiotic, exhibits modulatory effects on immune response and oxidative stress via IKK or production of anti-oxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT). Several studies suggest that manipulation of normal flora content may have beneficial effects in IBD[14-16]. L-carnitine (β hydroxyl-γ trimethyl amino butyrate) plays a significant role in fatty acid β-oxidation, glucose metabolism and general energy control in all types of cells including colonocytes. Production of SOD and inhibition of glutathione (GSH) reduction confirm its anti-oxidant feature and also protective effects against inflammation[17-20]. In summary, recent data revealed that butyrate, L-carnitine, and L. casei have noticeable beneficial potential in experimental IBD models alone or in combination with other medicines[21-24]. Therefore, in the present study we evaluated the synergism effect of the combination of these three agents by assessment of inflammatory indicators and pathological markers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

2,4,6-Trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid (TNBS), butyrate and L-carnitine from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie (Gmbh Munich, Germany), trichloroacetic acid, thiobarbituric acid (TBA), 2,4,6-Tri(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ), N-butanol, hexadecyl tri-methyl ammonium bromide, ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA), malondialdehyde, hydrochloric acid (HCL), acetic acid, sodium acetate, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), O-dianisidine hydrochloride, ferric chloride (FeCl3-6H2O), Coomassie reagent, bovine serum albumin (BSA), sodium sulphate (Na2SO4), sulphuric acid (H2SO4), phosphoric acid (H3PO4), potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4), dipotassium hydrogen phosphate (K2HPO4), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), Na-K-tartarate and cupric sulphate (CuSO4-5H2O) from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), whey powder from Shirpooyan-E-Yazd Co. (Tehran, Iran), powder of L. casei DN:114001 from Zist-Takhmir Co. (Tehran, Iran) and rat-specific TNF-α and IL-1β Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA) kits from (BenderMed Systems GmbH, Austria) were used in this study.

Animals

In this study, male Wistar rats weighing 180-200 g were selected according to regulations of the ethical committee of TUMS approved with code number of 91-03-33-19079. Animals were housed separately in standard polypropylene cages with a wire mesh top, kept under standard conditions including temperature (23 ± 1 °C), relative humidity (55% ± 10%), and 12/12 h light/dark cycle, and fed a standard pellet diet and water ad libitum.

Experimental design

Animals were divided into seven groups, with seven rats in each group. Colitis was induced by injection of TNBS rectally in all groups except the sham group, which received normal saline. Groups receiving TNBS were divided into control (as an untreated group), positive control (received 1 mg/kg dexamethasone dissolved in water), and treatment groups containing butyrate (1 mL of 0.5% in which 0.5 g butyrate was dissolved in 100 mL PBS), L-carnitine (500 mg/kg in 1 mL), L. casei (1 mL of whey culture contains 108 Cfu L. casei), and combination (0.5 mL butyrate, 0.5 mL L-carnitine, and 1 mL L. casei).

Whey culture (10% w/v, 10 g whey powder in 100 mL distilled water) was prepared at 121 °C for 20 min. Then, L. casei was added to it and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h.

The day TNBS was administered was assigned as the first day and all treatments started from the same day. During a 10-d treatment course, the groups were treated by gavage.

Induction of colitis

Prior to induction of colitis, rats were fasted for 36 h. They were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium[25]. Then, 0.3 mL of a mixture, comprising 6 volumes of 5% TNBS plus 4 volumes of 99% ethanol, was instilled through the anus using a rubber cannula (8 cm long) into rats situated on their right side, and then the rats were held in a prone Trendelenburg position to stop the anal leakage of TNBS[26].

Sample preparation

On treatment day 11, animals were sacrificed and colonic tissues were immediately separated. Isolated segments were rinsed with normal saline and then placed in an ice bath throughout the procedure. Colonic tissue was divided into two pieces. The first piece was weighed and kept in 10 mL of formalin 10%, as a fixator for the purpose of histopathological evaluation. The second piece was weighed and homogenized in 10 volumes of ice cold potassium phosphate buffer (50 mmol, pH = 7.4) and then stored at -20 °C for 24 h. The sample was then sonicated and centrifuged for 30 min at 3500 g, and the supernatant was transferred to a microtube. Then, the sample was kept at -80 °C until biomarker analyses.

Macroscopic and microscopic assessments

The following macroscopic scoring system was used to evaluate the severity of colonic damage: 0 - normal appearance with no damage; 1 - localized hyperemia without ulcer; 2 - localized hyperemia with an ulcer; 3 - a linear ulcer with inflammation at one site; 4 - two or more ulcers with damage extending 1-2 cm along the length of the colon; and 5 to 8 - damage extending more than 2 cm along the length of the colon and the score was increased by 1 for each increased cm of involvement.

The microscopic scoring was done by an observer who was blinded to the treated groups. Microscopic scores were determined as follows: 0 - no damage; 1 - focal epithelial edema and necrosis; 2 - disperse swelling and necrosis of the villi; 3 - necrosis with neutrophil infiltration in the submucosa; and 4 - widespread necrosis with massive neutrophil infiltration and hemorrhage.

Myeloperoxidase activity assessment

2.9 mL of 50 mmol/L phosphate buffer containing 0.167 mg/mL O-dianisidine hydrochloride and 0.0005% H2O2 was blended with 0.1 mL of the supernatant. The absorbance was measured for 3 min at 460 nm spectrophotometrically (Shimadzu 160A UV-VIS spectrophotometer) and expressed as unit per mg protein of colon tissue. One unit is equal to the change in absorbance per min at room temperature in the final reaction[27].

Lipid peroxidation assessment

Lipid peroxides as the end products of poly unsaturated fatty acid peroxidation are aldehydes that react with TBA named TBA reactive substance (TBARS) and form a complex which is detected at 532 nm by a double beam spectrophotometer. Concentration of TBARS is recorded as μg/mg protein[28].

Ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) assessment

Ferric-tripyridyltriazine (Fe3+-TPTZ) complex is reduced to bluish ferrous-tripyridyltriazine (Fe2+-TPTZ) with absorption at 593 nm. Values are reported as mmol/L ferric ions reduced to ferrous per mg protein. Details have been described previously[29].

IL-1β and TNF-α assessment

Using ELISA, the quantities of IL-1β and TNF-α (pg/mg protein of tissue) were measured. Amounts of blue complex resulting from conjugation of chromogenic substance with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidise (Streptavidin-HPR) were calculated at both 450 nm (primary wave length) and 620 nm (reference wave length). Details have been described previously[30].

Total protein assessment

Total protein was measured by the Bradford method using BSA as the standard and data are expressed as mg/mL of homogenized tissue at 540 nm[31].

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post-hoc tests was used for multiple comparisons of outcomes, and data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. StatsDirect version 3.0.107 was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Macroscopic and microscopic evaluation of histological impairment

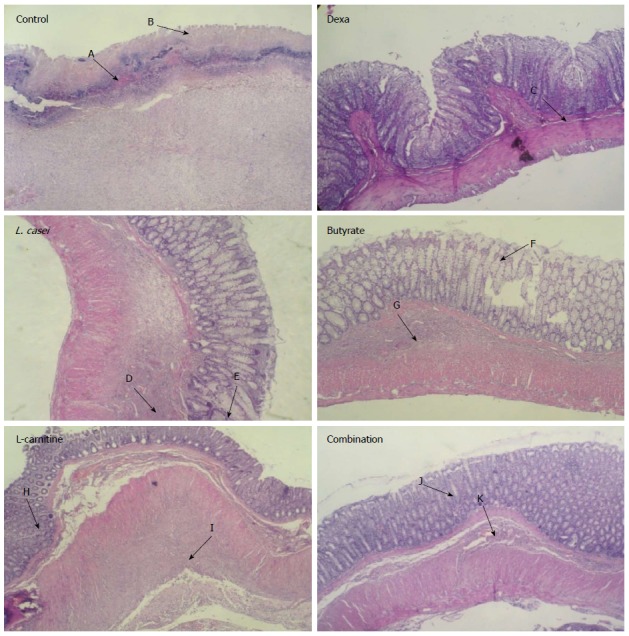

As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, histopathological examination of the control group which received TNBS showed severe ulcer, diffused necrosis, edema, crypt destruction, and mucosal/submucosal polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocyte infiltration, which were significantly different (P < 0.001) from the sham group that had normal histology and a regular mucosal layer with intact epithelial surface. In the L-carnitine group, crypt destruction and abscess, submucosal inflammation and low PMN infiltration were observed. In the butyrate group, mild infiltration, crypt destruction, edema, and disintegration of crypts were locally observed in some areas. Histopathological parameters in the L. casei group were most similar to those in the butyrate group. A significant reduction in microscopic scores was observed in each treatment group in terms of histological symptoms such as inflammation and/or diffuses necrosis hemorrhage and severe crypt destruction in comparison with the control group (P < 0.001). In the combination group, crypt abscess and mild inflammation of the submucosa with no PMN infiltration were observed. Although the histological scores decreased in the combination group (Table 1) and histopathological symptoms including PMN infiltration and crypt destruction were more vivid in comparison with monotherapy groups, there was no significant difference between the combination group and monotherapy groups.

Table 1.

Extent of colonic damage according to macroscopic and microscopic scores

| Groups | Macroscopic score (mean ± SEM); median (min-max) | Microscopic score (mean ± SEM); median (min-max) |

| Sham | (0.0 + 0.0) | (0.0 + 0.0) |

| 0 (0.0-0.0) | 0 (0.0-0.0) | |

| Control | (6.3 + 0.83)b | (3.6 + 0.24)b |

| 6 (4.0-8.0) | 4 (2.0-4.0) | |

| Dexamethasone | (1.0 + 0.34)d | (1.0 + 0.31)bd |

| 1 (0.0-2.0) | 2 (1.0-3.0) | |

| Combination | (1.00-0.51)d | (1.2-0.21)d |

| 1 (0.0-2.0) | 2 (1.0-3.0) | |

| Butyrate | (1.6 + 0.5)d | (1.4 + 0.24)d |

| 2 (2.0-4.0) | 2 (1.0-4.0) | |

| L-carnitine | (2.44 + 0.5)d | (1.66 + 0.26)bd |

| 2 (1.0-4.0) | 3 (2.0-4.0) | |

| L. casei | (2.64 + 0.6)d | (1.6 + 0.3)bd |

| 2 (2.0-5.0) | 3 (2.0-4.0) |

P < 0.001 vs sham group;

P < 0.001 vs control group.

Figure 1.

Histological images of colon tissues from control and experimental groups. Microscopic evaluation of Control group showed transmural inflammation and/or diffuse necrosis hemorrhage (A) and severe crypt destruction (B). In histological examination of Dexa group, minimal mucosal inflammation was observed (C). In L. casei and Butyrate groups, mild infiltration (D, G) and crypt destruction (E, F) were seen. In L-carnitine group, crypt formation (H), submucosa inflammation and low PMN infiltration (I) were observed. In Combination group, crypt abscess (J) and normal submucosa (K) were evident.

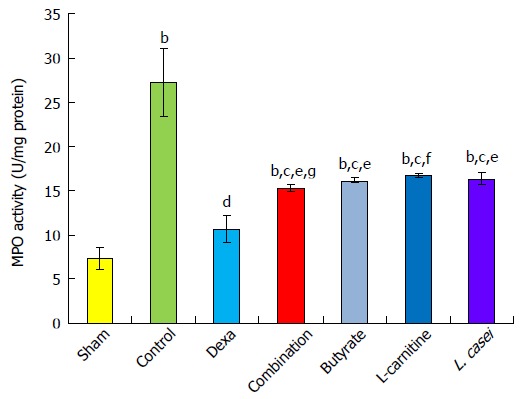

Myeloperoxidase activity

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was increased in inflamed tissues in the control group in comparison to the sham group (P < 0.01). The group of animals receiving monotherapies with butyrate, L-carnitine, and L. casei showed a reduction of MPO activity by 40.71%, 39.86%, and 38.95%, respectively, in comparison with controls (P < 0.05). Dexamethasone decreased MPO by 60.82% in comparison with control group (P < 0.01). Also, in the combination group, there was a significant reduction in MPO activity by 43.75% in comparison with the control group (P < 0.05). In the combination, butyrate, and L. casei groups, MPO increased by 17.07%, 20.11%, and 20.96%, respectively, in comparison with the dexamethasone group (P < 0.05). MPO increased by 21.87% in the L-carnitine group compared with the dexamethasone group (P < 0.01). The combination group showed a more reduction of MPO by 4.80% than the L-carnitine group (P < 0.05), while there was no significant difference between combination therapy and monotherapies with L. casei and butyrate (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Myeloperoxidase activity in the colon. Values are mean ± SEM. Significantly different from sham group at aP < 0.05; Significantly different from sham group at bP < 0.01; Significantly different from sham group at bP < 0.001; Significantly different from control group at cP < 0.05; Significantly different from control group at dP < 0.01; Significantly different from control group at dP < 0.001; Significantly different from Dexa group at eP < 0.05; Significantly different from Dexa group at fP < 0.01; Significantly different from Dexa group at fP < 0.001; Significantly different from L-Carnitine group at gP < 0.05; Significantly different from L-Carnitine group at hP < 0.01; Significantly different from L-Carnitine group at hP < 0.001.

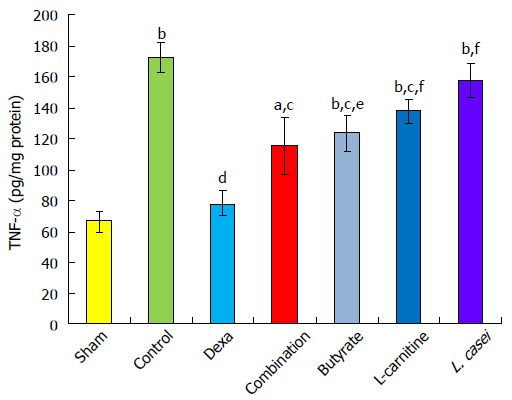

TNF-α level

There was an increase in TNF-α level in controls compared to the sham group (P < 0.001). In the dexamethasone group, TNF-α was reduced by 54.54% compared with the control group (P < 0.001). TNF-α level decreased in the combination, butyrate, and L-carnitine groups by 33.25%, 28.07%, and 19.90%, respectively, in comparison with the control group (P < 0.05). Dexamethason was more effective in reduction of TNF-α than monotherapies with butyrate by 26.46% (P < 0.05), L-carnitine by 34.63% and L. casei groups by 46.32% (P < 0.01). There was no notable difference when comparing combination therapy with single therapies (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

tumor necrosis factor-α level in the colon. Values are mean ± SEM. Significantly different from sham group at aP < 0.05; Significantly different from sham group at bP < 0.01; Significantly different from sham group at bP < 0.001; Significantly different from control group at cP < 0.05; Significantly different from control group at dP < 0.01; Significantly different from control group at dP < 0.001; Significantly different from Dexa group at eP < 0.05; Significantly different from Dexa group at fP < 0.01; Significantly different from Dexa group at fP < 0.001.

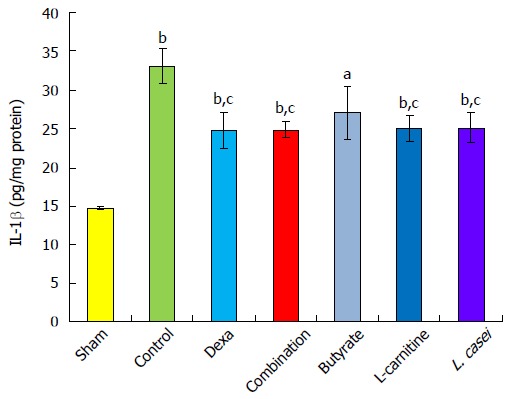

IL-1β level

The control group showed a notable elevation in IL-1β in comparison with the sham group (P < 0.001). In the dexamethasone, combination, L-carnitine, and L. casei groups, IL-1β diminished by 24.98%, 24.68%, 24.13%, and 24.22%, respectively, in comparison with the control group (P < 0.05). There was no significant change in the combination group when compared to monotherapies with butyrate, L-carnitine, and L. casei (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Interlukin-1β level in the colon. Values are mean ± SEM. Significantly different from sham group at aP < 0.05; Significantly different from sham group at bP < 0.01; Significantly different from sham group at bP < 0.001; Significantly different from control group at cP < 0.05; Significantly different from control group at dP < 0.01. Significantly different from control group at dP < 0.001; Significantly different from Dexa group at eP < 0.05; Significantly different from Dexa group at fP < 0.01; Significantly different from Dexa group at fP < 0.001.

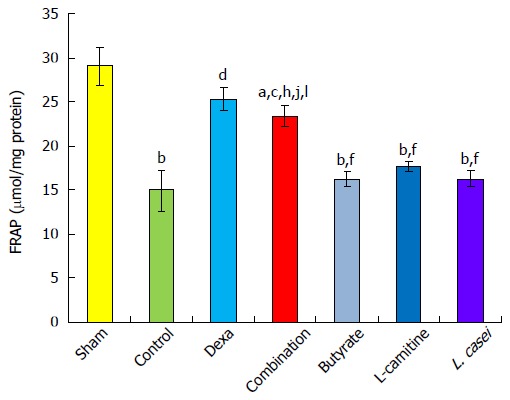

Anti-oxidant power measured by FRAP

Anti-oxidant power decreased in the control group as compared with the sham group (P < 0.01). FRAP value in the dexamethasone group increased by 68.04% (P < 0.001) and in the combination group by 56.19% when compared with controls (P < 0.05). Monotherapies with butyrate, L-carnitine, and L. casei decreased FRAP by 59.92%, 50.73%, and 59.45%, respectively, as compared to the dexamethasone group (P < 0.01). The improvements of FRAP by monotherapies with butyrate, L-carnitine, and L. casei were 8.12%, 17.31%, and 8.58%, respectively, which were all lower than that in the combination group (56.19%, P < 0.01) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Ferric reduced ability of plasma level in the colon. Values are mean ± SEM. Significantly different from sham group at aP < 0.05; Significantly different from sham group at bP < 0.01; Significantly different from sham group at bP < 0.001; Significantly different from control group at cP < 0.05; Significantly different from control group at dP < 0.01; Significantly different from control group at dP < 0.001; Significantly different from Dexa group at eP < 0.05; Significantly different from Dexa group at fP < 0.01; Significantly different from Dexa group at fP < 0.001; Significantly different from butyrate group at gP < 0.05; Significantly different from butyrate group at hP < 0.01; Significantly different from butyrate group at hP < 0.001; Significantly different from L-carnitine group at iP < 0.05; Significantly different from L-carnitine group at jP < 0.01; Significantly different from L-carnitine group at jP < 0.001; Significantly different from L. casei group at kP < 0.05; Significantly different from L. casei group at lP < 0.01; Significantly different from L. casei group at lP < 0.001.

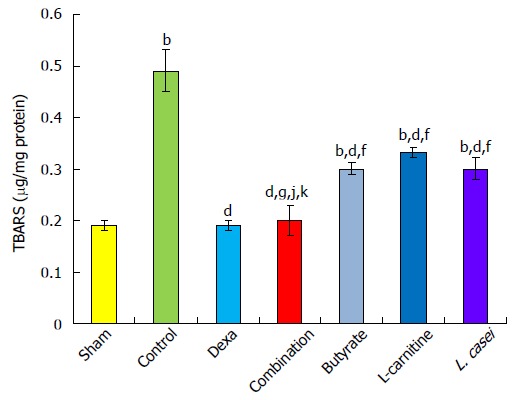

Oxidative stress measured by TBARS

Elevation of TBARS was evident in controls compared with the sham group (P < 0.001). Dexamethasone (P < 0.001), combination therapy and monotherapies with butyrate, L-carnitine, and L. casei (P < 0.01) restored TBARS by 61.22%, 59.18%, 38.77%, 32.65%, and 38.77%, respectively, in comparison with controls. Reduction of TBARS was significantly lower in the butyrate and L-carnitine groups by 22.44% and 28.57% (P < 0.001), respectively, and in the L. casei group by 22.44% (P < 0.01) in comparison with the dexamethasone group. The combination group showed a more decrease in TBARS than the butyrate and L. casei groups by 20.40% and 20.40%, respectively (P < 0.05). TBARS changed 32.65% in the L-carnitine group, which was significantly lower than that in the combination group (59.18%, P < 0.01) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances level in the colon. Values are mean ± SEM. Significantly different from sham group at aP < 0.05; Significantly different from sham group at bP < 0.01; Significantly different from sham group at bP < 0.001. Significantly different from control group at cP < 0.05; Significantly different from control group at dP < 0.01; Significantly different from control group at dP < 0.001; Significantly different from Dexa group at eP < 0.05; Significantly different from Dexa group at fP < 0.01; Significantly different from Dexa group at fP < 0.001; Significantly different from butyrate group at gP < 0.05; Significantly different from butyrate group at hP < 0.01; Significantly different from butyrate group at hP < 0.001; Significantly different from L-carnitine group at iP < 0.05; Significantly different from L-carnitine group at jP < 0.01; Significantly different from L-carnitine group at jP < 0.001; Significantly different from L. casei group at kP < 0.05; Significantly different from L. casei group at lP < 0.01; Significantly different from L. casei group at lP < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Regarding overall results, the present study demonstrated the priority of combination of butyrate, L. casei and L-carnitine in ameliorating the severity of colitis in comparison to monotherapies. Macroscopic features including appearance of isolated tissue and histopathological scores such as presence of edema, necrosis, neutrophil infiltration, and biomarkers including TNF-α, IL-1β, MPO, TBARS, and anti-oxidant power confirmed the beneficial effect of the combination treatment in comparison to controls. Specifically, the combination therapy was much better in reducing colon oxidative stress markers including FRAP, TBARS, and MPO.

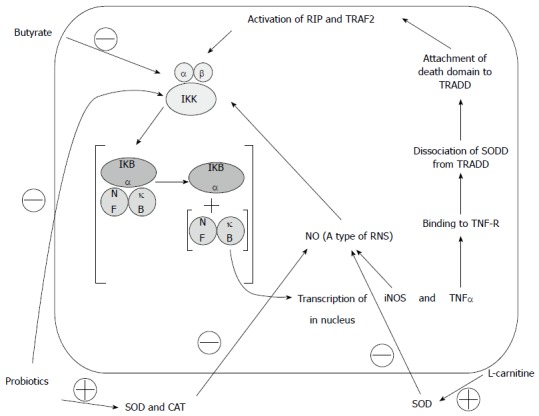

Although there are several reports on the positive effects of these three agents in inflammation or oxidative stress explained through various mechanisms[13,14,17], the current study based on an original hypothesis[11] is the first one that confirms synergism between butyrate, L. casei and L-carnitine in the immune-based model of colitis. TNBS-induced colitis is believed a preferential model since the colon’s barrier is broken by ethanol and then delayed-response hypersensitivity reaction by TNBS occurs like that of human IBD[20,32-34]. This similarity is confirmed by the same pattern of changes in examined cytokines between experimental studies and those reported in humans such as accumulation of MPO, TNF-α, IL-1β, ROS, and RNS[4,26,35-38]. Specifically, MPO, a hemo enzyme, is released dramatically from neutrophils in order to eradicate pathogens. It facilitates production of cytotoxic agents like hypochlorite acid (HOCl), the stimulator of NF-κB that is able to induce other inflammatory factors via H2O2[39,40]. Results indicate that MPO as a neutrophil infiltration indicator and TBARS as an indicator of lipid peroxidation are markedly up-regulated in colon tissues while these are restored by combination therapy. This is most likely due to their radical scavenging properties[3]. As shown schematically in Figure 7, butyrate is able to lessen oxidants through suppressing IKK, which is responsible for dissociation of NF-κB from IKB-α, and then free-NF-κB fortifies oxidants via overexpression of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene[4]. In addition, probiotics have the same effect either directly by production of SOD and CAT against oxidants or blocking IKK indirectly[15,16]. Likewise, L-carnitine modifies activity of oxidative stress by elevation of SOD and prevention of decrease in GSH content[17-20], and eventually, the combination treatment exerts well against oxidants with higher efficacy related to synergism of these three agents. In turn, observed changes in the FRAP test support that idea. Regarding the inflammation, TNF-α, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, is produced mainly by macrophages and activated T-lymphocytes. It is an active component in apoptosis, stimulation of IL-1β secretion, and inflammation, in which re-induction of IKK occurs. This process is mediated through the cascade consisting of binding to TNF receptor (TNF-R) accompanied with dissociation of silencer of death domains from TNF-R type1-associated death domain. Further attachment of TRADD to death domain leads to the activation of the ribosome inactivating protein and TNF-R associated factor 2 which trigger IKK[11,13,41]. In addition, IL-1β has a crucial role in inflammation, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, which is secreted from macrophages, neutrophils, endothelial, and epithelial cells[42]. Our results indicate that in contrast to the control group, abundant formation of IL-1β and TNF-α was restricted in the treatment groups. This is explained by the drop in inflammation either through blocking IKK to activate NF-κB or inability to overexpress inflammatory cytokines. However, obvious differences are evident between monotherapy groups and the combination group in amelioration of inflammation that originates from synergistic effects in the combination therapy.

Figure 7.

Effects of butyrate, L-carnitine, and probiotics on Ikappa B kinase. Adopted from authors’s previous Open Access publication (Moeinian et al. Synergistic effect of probiotics, butyrate and L-carnitine in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). J Med Hypotheses Idea 2013; 7: 50-53)[11]. SOD: Superoxide dismutase; CAT: Catalase; IKK: IκB kinase; iNOS: Inducible nitric oxide synthase; NO: Nitric oxide; NF-κB: Nuclear factor-kappa B; RIP: Ribosome inactivating protein; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; TNF-R: Tumor necrosis factor receptor; TRADD: Tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1-associated death domain protein; TRAF2: Tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor 2; SODD: Silencer of death domain.

In summary, a high level of anti-oxidative stress ability, anti-inflammation feature and positive interactions amplify the effects of the combination therapy by overexpression of sodium-coupled mono carboxylate transporter 1 gene, an essential gene for butyrate absorption. Besides, probiotics are able to promote the expression of organic cation transporter number 2, an organic cation transporter that mediates L-carnitine absorption, and thus to enhance β-oxidation of butyrate. This supports the belief that this mixture is more remedial with less complications[11,18,20,33,42-47]. No toxicity following administration of each of them individually or in combination observed in this study certifies the safety of this mixture. Literature shows no severe complications in ordinary patients who take ordinary doses of L. casei or L-carnitine[48-50]. However, more investigations are required to clarify the mixture’s safety in the clinical setting. According to the results, the combination of these three agents is more effective than each alone in attenuation of the inflammatory process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Malihe Moeinian from Dental School of Queen Mary, University of London for her help with editing the article.

COMMENTS

Background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is divided into two major and idiopathic conditions, ulcerative colitis and Crohn′s disease. Current choice in control of IBD is administration of aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants that are associated with side effects. Due to side effects of current conventional therapies, scientists have tried to discover more potent and safer alternatives. The authors intended to demonstrate that the combination of butyrate, L-carnitine, and L. casei may be an effective and safe mixture in amelioration of colitis.

Research frontiers

Several studies focused on the major role of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling which results in overproduction of inflammatory mediators and oxidants in the progress of inflammation. In this study, the authors evaluated the capacity of the combination therapy in healing the colitis and improvement of inflammatory cytokines.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The present study indicated that the combination therapy is able to heal colitis and down-regulate the production of inflammatory cytokines. Inhibition of the NF-κB pathway either by suppression of IKK or production of enzymes against free radicals is the main mechanism of action of this mixture.

Applications

Safety and effectiveness besides positive interactions of these three agents confirm that this combination can be more helpful in healing IBD and improving the patients’ quality of life.

Peer review

The main hypothesis of the paper for management of IBD is valuable.

Footnotes

Supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (partially)

P- Reviewer: Grover S, Marsh AMR S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Sartor RB. Mechanisms of disease: pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3:390–407. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oz HS, Ebersole JL. Application of prodrugs to inflammatory diseases of the gut. Molecules. 2008;13:452–474. doi: 10.3390/molecules13020452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mozaffari S, Nikfar S, Abdolghaffari AH, Abdollahi M. New biologic therapeutics for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14:583–600. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2014.885945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rezaie A, Parker RD, Abdollahi M. Oxidative stress and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease: an epiphenomenon or the cause? Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2015–2021. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mozaffari S, Abdollahi M. Melatonin, a promising supplement in inflammatory bowel disease: a comprehensive review of evidences. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:4372–4378. doi: 10.2174/138161211798999357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahimi R, Mozaffari S, Abdollahi M. On the use of herbal medicines in management of inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review of animal and human studies. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:471–480. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0368-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikfar S, Mirfazaelian H, Abdollahi M. Efficacy and tolerability of immunoregulators and antibiotics in fistulizing Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:3684–3698. doi: 10.2174/138161210794079236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahimi R, Shams-Ardekani MR, Abdollahi M. A review of the efficacy of traditional Iranian medicine for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4504–4514. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i36.4504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadjibabaie M, Rastkari N, Rezaie A, AbdollahiM The adverse drug reaction in the gastrointestinal tract: an overview. Int J Pharmacol. 2005;1:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lührs H, Gerke T, Müller JG, Melcher R, Schauber J, Boxberge F, Scheppach W, Menzel T. Butyrate inhibits NF-kappaB activation in lamina propria macrophages of patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:458–466. doi: 10.1080/003655202317316105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moeinian M, Ghasemi-Niri SF, Mozaffari S, Abdollahi M. Synergistic effect of probiotics, butyrate and L-Carnitine in treatment of IBD. J Med Hypotheses Idea. 2013;7:50–53. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tedelind S, Westberg F, Kjerrulf M, Vidal A. Anti-inflammatory properties of the short-chain fatty acids acetate and propionate: a study with relevance to inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2826–2832. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i20.2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segain JP, Raingeard de la Blétière D, Bourreille A, Leray V, Gervois N, Rosales C, Ferrier L, Bonnet C, Blottière HM, Galmiche JP. Butyrate inhibits inflammatory responses through NFkappaB inhibition: implications for Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2000;47:397–403. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hegazy SK, El-Bedewy MM. Effect of probiotics on pro-inflammatory cytokines and NF-kappaB activation in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4145–4151. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i33.4145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howarth GS. Inflammatory bowel disease, a dysregulated host-microbiota interaction: are probiotics a new therapeutic option? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1777–1779. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeBlanc JG, del Carmen S, Miyoshi A, Azevedo V, Sesma F, Langella P, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Watterlot L, Perdigon G, de Moreno de LeBlanc A. Use of superoxide dismutase and catalase producing lactic acid bacteria in TNBS induced Crohn’s disease in mice. J Biotechnol. 2011;151:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fortin G, Yurchenko K, Collette C, Rubio M, Villani AC, Bitton A, Sarfati M, Franchimont D. L-carnitine, a diet component and organic cation transporter OCTN ligand, displays immunosuppressive properties and abrogates intestinal inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;156:161–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koc A, Ozkan T, Karabay AZ, Sunguroglu A, Aktan F. Effect of L-carnitine on the synthesis of nitric oxide in RAW 264·7 murine macrophage cell line. Cell Biochem Funct. 2011;29:679–685. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cetinkaya A, Bulbuloglu E, Kantarceken B, Ciralik H, Kurutas EB, Buyukbese MA, Gumusalan Y. Effects of L-carnitine on oxidant/antioxidant status in acetic acid-induced colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:488–494. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurutas EB, Cetinkaya A, Bulbuloglu E, Kantarceken B. Effects of antioxidant therapy on leukocyte myeloperoxidase and Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase and plasma malondialdehyde levels in experimental colitis. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:390–394. doi: 10.1155/MI.2005.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Rahimi F, Derakhshani S, Abdollahi M. Efficacy of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1775–1780. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9335-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salari P, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis and systematic review on the effect of probiotics in acute diarrhea. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2012;11:3–14. doi: 10.2174/187152812798889394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rahimi F, Elahi B, Derakhshani S, Vafaie M, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis on the efficacy of probiotics for maintenance of remission and prevention of clinical and endoscopic relapse in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2524–2531. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis of the benefit of probiotics in maintaining remission of human ulcerative colitis: evidence for prevention of disease relapse and maintenance of remission. Arch Med Sci. 2008;4:185–190. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdollahi M, Dehpour AR, Baharnouri G. Alteration by rubidium of rat submandibular secretion of protein and N- acetyl-D-glucosaminidase. Toxic Subst Mech. 1998;17:121–131. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esmaily H, Hosseini-Tabatabaei A, Rahimian R, Khorasani R, Baeeri M, Barazesh-Morgani AR, Yasa N, Khademi Y, Abdollahi M. On the benefits of silymarin in murine colitis by improving balance of destructive cytokines and reduction of toxic stress in the bowel cells. CentEur J Biol. 2009;4:204–213. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghazanfari G, Minaie B, Yasa N, Nakhai LA, Mohammadirad A, Nikfar S, Dehghan G, Boushehri VS, Jamshidi H, Khorasani R, et al. Biochemical and histopathological evidences for beneficial effects of satureja khuzestanica jamzad essential oil on the mouse model of inflammatory bowel diseases. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2006;16:365–372. doi: 10.1080/15376520600620125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakhai LA, Mohammadirad A, Yasa N, Minaie B, Nikfar S, Ghazanfari G, Zamani MJ, Dehghan G, Jamshidi H, Boushehri VS, et al. Benefits of Zataria multiflora Boiss in Experimental Model of Mouse Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4:43–50. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasani P, Yasa N, Vosough-Ghanbari S, Mohammadirad A, Dehghan G, Abdollahi M. In vivo antioxidant potential of Teucrium polium, as compared to alpha-tocopherol. Acta Pharm. 2007;57:123–129. doi: 10.2478/v10007-007-0010-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ebrahimi F, Esmaily H, Baeeri M, Mohammadirad A, Fallah S, Abdollahi M. Molecular evidences on the benefit of N-acetylcysteine in experimental colitis. Cent Eur J Biol. 2008;3:135–132. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdolghaffari AH, Baghaei A, Moayer F, Esmaily H, Baeeri M, Monsef-Esfahani HR, Hajiaghaee R, Abdollahi M. On the benefit of Teucrium in murine colitis through improvement of toxic inflammatory mediators. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2010;29:287–295. doi: 10.1177/0960327110361754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esmaily H, Sanei Y, Abdollahi M. Autoantibodies and an immune-based rat model of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7569–7576. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin PW, Myers LE, Ray L, Song SC, Nasr TR, Berardinelli AJ, Kundu K, Murthy N, Hansen JM, Neish AS. Lactobacillus rhamnosus blocks inflammatory signaling in vivo via reactive oxygen species generation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1205–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torres MI, García-Martin M, Fernández MI, Nieto N, Gil A, Ríos A. Experimental colitis induced by trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid: an ultrastructural and histochemical study. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:2523–2529. doi: 10.1023/a:1026651408998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Meta-analysis technique confirms the effectiveness of anti-TNF-alpha in the management of active ulcerative colitis when administered in combination with corticosteroids. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:PI13–PI18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Esmaily H, Vaziri-Bami A, Miroliaee AE, Baeeri M, Abdollahi M. The correlation between NF-κB inhibition and disease activity by coadministration of silibinin and ursodeoxycholic acid in experimental colitis. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2011;25:723–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2010.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen C, de Hertogh G, Bullens DM, Van Assche G, Geboes K, Rutgeerts P, Ceuppens JL. Remission-inducing effect of anti-TNF monoclonal antibody in TNBS colitis: mechanisms beyond neutralization? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:308–316. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hosseini-Tabatabaei A, Abdollahi M. Potassium channel openers and improvement of toxic stress: do they have role in the management of inflammatory bowel disease? Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2008;7:129–135. doi: 10.2174/187152808785748164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grulke S, Franck T, Gangl M, Péters F, Salciccia A, Deby-Dupont G, Serteyn D. Myeloperoxidase assay in plasma and peritoneal fluid of horses with gastrointestinal disease. Can J Vet Res. 2008;72:37–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mustafa A, El-Medany A, Hagar HH, El-Medany G. Ginkgo biloba attenuates mucosal damage in a rat model of ulcerative colitis. Pharmacol Res. 2006;53:324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bradley JR. TNF-mediated inflammatory disease. J Pathol. 2008;214:149–160. doi: 10.1002/path.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li L, Fei Z, Ren J, Sun R, Liu Z, Sheng Z, Wang L, Sun X, Yu J, Wang Z, et al. Functional imaging of interleukin 1 beta expression in inflammatory process using bioluminescence imaging in transgenic mice. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gloire G, Legrand-Poels S, Piette J. NF-kappaB activation by reactive oxygen species: fifteen years later. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1493–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boirivant M, Strober W. The mechanism of action of probiotics. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:679–692. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282f0cffc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carroll IM, Andrus JM, Bruno-Bárcena JM, Klaenhammer TR, Hassan HM, Threadgill DS. Anti-inflammatory properties of Lactobacillus gasseri expressing manganese superoxide dismutase using the interleukin 10-deficient mouse model of colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G729–G738. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00132.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Russo I, Luciani A, De Cicco P, Troncone E, Ciacci C. Butyrate attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in intestinal cells and Crohn’s mucosa through modulation of antioxidant defense machinery. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 47.Srinivasan R, Meyer R, Padmanabhan R, Britto J. Clinical safety of Lactobacillus casei shirota as a probiotic in critically ill children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:171–173. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000189335.62397.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borthakur A, Anbazhagan AN, Kumar A, Raheja G, Singh V, Ramaswamy K, Dudeja PK. The probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum counteracts TNF-{alpha}-induced downregulation of SMCT1 expression and function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G928–G934. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00279.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gasbarrini G, Mingrone G, Giancaterini A, De Gaetano A, Scarfone A, Capristo E, Calvani M, Caso V, Greco AV. Effects of propionyl-L-carnitine topical irrigation in distal ulcerative colitis: a preliminary report. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1385–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Didari T, Solki S, Mozaffari S, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. A systematic review of the safety of probiotics. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:227–239. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2014.872627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]