Abstract

Several rapid physiological effects of thyroid hormone on mammalian cells in vitro have been shown to be mediated by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), but the molecular mechanism of PI3K regulation by nuclear zinc finger receptor proteins for thyroid hormone and its relevance to brain development in vivo have not been elucidated. Here we show that, in the absence of hormone, the thyroid hormone receptor TRβ forms a cytoplasmic complex with the p85 subunit of PI3K and the Src family tyrosine kinase, Lyn, which depends on two canonical phosphotyrosine motifs in the second zinc finger of TRβ that are not conserved in TRα. When hormone is added, TRβ dissociates and moves to the nucleus, and phosphatidylinositol (3, 4, 5)-trisphosphate production goes up rapidly. Mutating either tyrosine to a phenylalanine prevents rapid signaling through PI3K but does not prevent the hormone-dependent transcription of genes with a thyroid hormone response element. When the rapid signaling mechanism was blocked chronically throughout development in mice by a targeted point mutation in both alleles of Thrb, circulating hormone levels, TRβ expression, and direct gene regulation by TRβ in the pituitary and liver were all unaffected. However, the mutation significantly impaired maturation and plasticity of the Schaffer collateral synapses on CA1 pyramidal neurons in the postnatal hippocampus. Thus, phosphotyrosine-dependent association of TRβ with PI3K provides a potential mechanism for integrating regulation of development and metabolism by thyroid hormone and receptor tyrosine kinases.

One of the major biological discoveries of the past 50 years is that many hormones regulate gene expression through receptor proteins that bind to DNA (1). More recently it has become clear that in many cases the same hormones produce rapid effects on cell physiology through the same receptors signaling in the cytoplasm (2–4). However, testing the relative importance of the genomic and nongenomic mechanisms in vivo has been prevented by the absence of specific molecular mechanisms for the nongenomic effects that could be blocked by mutation of the receptor without disrupting its direct effects on gene expression.

The thyroid hormone, 3,5,3′ triiodothyronine (T3), is an essential regulator of human growth, brain maturation, and adult cognition and metabolism (5). Like steroid hormones, many of the physiological effects of T3 are mediated through regulation of gene expression by zinc finger nuclear receptor proteins that are encoded by the Thra and Thrb genes (6, 7). However, many in vitro effects of T3 are too rapid to be explained by transcriptional regulation (8, 9). Beginning with our electrophysiological studies of Kv11.1 potassium channel regulation by thyroid hormone in a rat pituitary cell line (10), the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) has been implicated in several of these rapid effects (11, 12).

PI3K is a lipid kinase that phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol (4, 5)-bisphosphate to produce phosphatidylinositol (3, 4, 5)-trisphosphate (PIP3). PIP3 initiates a signaling cascade of protein phosphorylation and small G protein activation by attracting various effectors to the membrane (13). Like thyroid hormone, PI3K activity is also essential for growth and metabolism (14) and brain development (15). Thus, environmental disruption of thyroid hormone signaling through PI3K might produce many of the physiological changes associated with hypothyroidism (16).

In most tissues PI3K is regulated primarily by receptor tyrosine kinases (13, 14), and an integrin receptor that mediates some of the PI3K-dependent effects of T4, the widely circulated precursor of T3, has been identified (17). However, both TRα (18, 19) and TRβ (20–23) have also been reported to associate with PI3K and stimulate its activity in many cell types. In particular, we have demonstrated that TRβ is required to reconstitute T3 and PI3K-dependent regulation of Kv11.1 channels in cell-free membrane patches from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (24). Nevertheless, neither the molecular mechanism by which the nuclear receptors stimulate PI3K activity nor the physiological relevance of thyroid hormone signaling through PI3K in vivo has been elucidated.

Here we use a fluorescent PIP3 indicator (25) to make direct measurements of PIP3 production in response to thyroid hormone on the same time scale as the electrophysiological measurements in the CHO cells expressing recombinant human thyroid hormone receptors. This system has allowed us to identify a specific molecular mechanism for rapid PI3K activation by TRβ, which involves a cytoplasmic complex of TRβ, the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K, and the Src family kinase, Lyn. Complex formation involves two canonical, but previously unidentified, phosphotyrosine motifs in the second, DNA-binding zinc-finger domain of TRβ that are not conserved in most other nuclear receptors or even in most nonmammalian orthologs of TRβ. Thus, this complex provides a unique mechanism for integrating growth signals through thyroid hormone and receptor tyrosine kinases, and we test its significance for mouse brain development by making a mouse line with one of the tyrosines in TRβ mutated to phenylalanine.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Anti-FLAG (M2), horseradish peroxidase-conjugated-FLAG, and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated FLAG antibodies and wortmannin were purchased from Sigma. Antibodies that recognize Lyn, p85, and phosphotyrosine were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. SU6656, an antagonist of Src family kinases, and 1–850, an antagonist of thyroid hormone receptors, were purchased from Calbiochem.

Cell culture

All cell lines were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. GH4C1 cells were maintained in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% calf serum (Hyclone), 0.15% sodium bicarbonate, and penicillin/streptomycin. CHO and CV-1 cells were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and penicillin/streptomycin. Thyroidectomized bovine serum was purchased from Rockland Immunochemicals.

PIP3 indicator assay

Cells were infected with a sinLacZc3855t sindbis viral replicon encoding a fluorescent indicator of PIP3 (25) and imaged the following day at room temperature on a Zeiss confocal microscope. Images in response to cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) excitation at 458 nm were taken every 2 minutes for 30 minutes after adding the indicated solutions. Zeiss Image Analysis software was used to record the change in emission ratio of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP; 530–600 nm) to CFP (475–525 nm) across the entire cell. Selectively photobleaching YFP with 514 nm illumination eliminated the Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET) signal while increasing CFP emission, confirming the validity of our illumination and filter settings.

Confocal imaging of TRβ distribution

CHO cells expressing FLAG-tagged TRβ1 were serum starved overnight in DMEM. The following day, cells were incubated in DMEM plus 50 mM sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4) for 2 hours and then stimulated for 30 minutes with serum from thyroidectomized cows plus or minus 100 nM T3. After the stimulation, cells were washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) twice and fixed in methanol-acetone (1:1) for 1 minute. Cells were washed with TBS four times and incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody for 2 hours at room temperature. Cells were washed three times with TBS to remove excess antibody and imaged on a Zeiss LM-510 confocal microscope. To minimize observer bias in interpreting the images, the observers did not know the treatment of the cells they were scoring.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed in 1 mL of cold PLC lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 10% glycerol; 1% Triton X-100; 1 mM EGTA; 1.5 mM MgCl2; and 100 mM NaF) supplemented with complete EDTA protease inhibitor (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail set II (Calbiochem). Insoluble debris was pelleted, and the remaining soluble protein lysates were resolved on SDS-PAGE and probed for protein levels or used for immunoprecipitation. EZview anti-FLAG beads (Sigma) were used to immunoprecipitate FLAG tagged proteins before resolving by Western blots. All antibodies were used as described by the manufacturer. Tandem mass spectrometry of the immunoprecipitates was performed essentially as described previously (26).

TRβ mutant mice

Animals with a point mutation in the coding region of the Thrb gene, which encodes the thyroid hormone receptors, TRβ1 and TRβ2, were made by recombination of a mutated DNA segment in C57BL/6 embryonic stem (ES) cells, which were selected by G418 resistance. In Southern blots the neo probe showed a unique 14.2-kb KpnI fragment to verify that only one integration had occurred at the homologous locus in the mouse genome. Subsequently chimeric mice were generated from recombined, neo-deleted ES cell clones by injection into C57B6/Tyr blastocysts. The amino acid tyrosine at position 147 of TRβ1 in the sequence KYEGK (GenBank entry locus: NM_001113417) was mutated to a phenylalanine (KFEGK) by changing exon 3 codon TAT to TTT in the targeting vector for the ES cells. Chimeric mice were bred to C57BL/6 wild-type animals to generate heterozygous mutant animals, from which homozygous mutants were obtained by further breeding. Offspring were screened by PCR and Southern blot for the presence of the mutated allele. In the Southern blot, using a probe the 5′ of the targeting region, a wild-type 18.6-kb BamHI fragment was reduced to 11.7 kb in the mutant. With a probe 3′ of the targeting region, a 12.2-kb KpnI fragment is shifted to 14.2 kb in the mutant allele. Sperm from the homozygous mice have been cryopreserved at Jackson Labs (mThrb Jax stock number 911448).

Subsequent screening of heterozygous and homozygous experimental animals was done by PCR using the following primer pair, mouse Thrb forward: 5′-ACACACAGGCTCCACATGCTGAGAG-3′ and mouse Thrb reverse: 5′-ACTGGGTTTATAGGCTGTCAGGCTTGG-3′, which yield a 350-bp wild-type fragment and a 490-bp mutant fragment. Animals (C57BL/6-Thrb<tm1Ehs> or TRβ147F), were kept on a C57BL/6 backcross and used for experiments at different ages. Because the Thrb transcript is alternately spliced 5′ to the mutation, the mutant phenylalanine has a different number in the two resulting proteins: F147 in TRβ1 and F161 in TRβ2. All procedures in this study were approved by the National Institute of Environmental Health and Sciences Animal Care and Use Committee.

Gene expression analysis [quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)]

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit with deoxyribonuclease treatment (QIAGEN) from the cortices of 12- to 17-day-old mice or the pituitary glands and livers from 4-month-old mice. Purity and concentration were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific). cDNA was produced from 1 μg of total RNA by reverse transcription with polydeoxythymidine primers using the reverse transcription system kit (Promega) and the manufacturer's recommended program parameters. Gene expression was measured by qPCR. The primers used for the amplification were as follows: Thrb forward, 5′-AGGAACCTTTACACCTGCTCCACT-3′, Thrb reverse, 5′-CATGTGCACAGCCTTCTTGTCCAT-3′; Tshb forward, 5′-TGCCCGCACCATGTTACTCCTTAT-3′, Tshb reverse, 5′-TGCAGTAGTTGGTTCTGACAGCCT-3′; Spot14 forward, 5′-TGAGAACGACGCTGCTGAAAC-3′, Spot14 reverse, 5′-AGGTGGGTAAGGATGTGATGGAG-3′; and Dio1 forward, 5′-CCACCTTCTTCAGCATCC-3′, Dio1 reverse, 5′-AGTCATCTACGAGTCTCTTG-3′.

The amplification was performed using the manufacturer's protocol in the Fast SYBR Green master mix kit (Applied Biosystems). All experiments were performed in duplicate for each sample tissue analyzed. Relative expression data were normalized to the expression of Gapdh in pituitary and brain or Rplp0 (36B4) in liver using the following primers: Gapdh forward, 5′-TGTGATGGGTGTGAACCACGAGAA-3′, Gapdh reverse, 5′-CATGAGCCCTTCCACAATGCCAAA-3′; and 36B4 forward, 5′-TGTTTGACAACGGCAGCATTT-3′, 36B4 reverse, 5′-CCGAGGCAACAGTTGGGTA-3′.

Transcriptional assay

Tandem arrays of the palindromic pTK-Pal-Luc reporter construct (Dr S. Y. Cheng, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) and the DR4 T4T-Luc reporter (Dr W. Dillmann, University of California, San Diego) were used to measure the transcriptional activity of thyroid hormone receptors with the dual luciferase assay kit (Promega). DNA transfection of CV-1 cells was performed with Lipofectamine (Life Technologies) or TurboFect reagent (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer's recommendations. One hundred nanograms of Firefly luciferase and 50 ng of Renilla luciferase plasmids were cotransfected along with 1 μg of receptor (TRα, TRβ, Y147F, or Y171F) or empty vector. Sixteen hours after the transfection, the media were replaced with thyroid hormone-free media. Twenty-four hours after the transfection, the cells were treated with 100 nM T3 for 18 hours. The cells were then lysed and the luciferase activity assays were read in an Infinite F200 automatic luminometer (Tecan). The Renilla luciferase activity, which is driven by a thyroid hormone-independent cytomegalovirus promoter, was used to correct for transfection efficiency, sample loss, and other factors that could affect the results.

Measuring serum levels of T3 and T4

Four-month-old mice, either wild-type (n = 6) or homozygous mutants (n = 6), were used to collect blood by orbital bleeds for analysis of thyroid hormone levels in serum by mass spectrometry as described previously (27).

Electrophysiology

The electrophysiological experiments were performed on hippocampal slices of C57BL/6NCrl mice (12–18 d old) of both sexes. Briefly, the mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane, and the brains were removed quickly and submerged in ice-cold, sucrose-substituted, artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) solution containing (in millimoles): 240 sucrose, 2.0 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose, which was bubbled continuously with 95% O2-5% CO2 to obtain a pH of 7.4. Coronal slices (250 μm) were obtained on a vibrating microtome (LEICA VT 1200S) and then submerged in standard oxygenated ACSF solution at room temperature for longer than 1 hour before recording. The standard ACSF contained (in millimoles): 124 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, and 26 NaHCO3 and 17 days glucose (pH 7.4).

Slices were placed in a recording chamber on an upright microscope and continuously perfused with the oxygenated standard ACSF solution at a flow rate of 2–3 mL/min. Patch-clamp pipettes (3–6 MΩ) were prepared from borosilicate glass capillaries (WPI) and filled with a potassium gluconate internal solution containing the following (in millimoles): 120 K-gluconate, 10 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 0.2 EGTA, 40 HEPES, 2 Na2-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP. The pH was adjusted to 7.3 with KOH, and osmolarity was maintained at 280 mOsm. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from visually identified CA1 pyramidal cells in the hippocampus. All cells were held at a potential of −70 mV, and the series resistance was monitored continuously. Schaffer collateral axons from CA3 neurons were stimulated once every 15 seconds (0.07 Hz) with cluster-type stimulating electrodes (FHC Inc), which were positioned in the Stratum radiatum, approximately 150 μm from the patched neuron, to produce excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) on the CA1 neurons.

Data were acquired with pClamp 10.2 software (Molecular Devices), filtered at 2 kHz, and digitized at 5–10 kHz using the Digidata 1321A digitizer. Values are represented as mean ± SEM, and n values represent the number of recordings from individual slice preparations. Only a single recording was taken from each slice preparation.

Data analysis

We compared the results of measurements in wild-type and mutant mice using the unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test (GraphPad Prism) to estimate the probability that the two data sets arose by chance from the same distribution. Differences were considered significant when P < .05.

Results

TRβ-dependent activation of PI3K

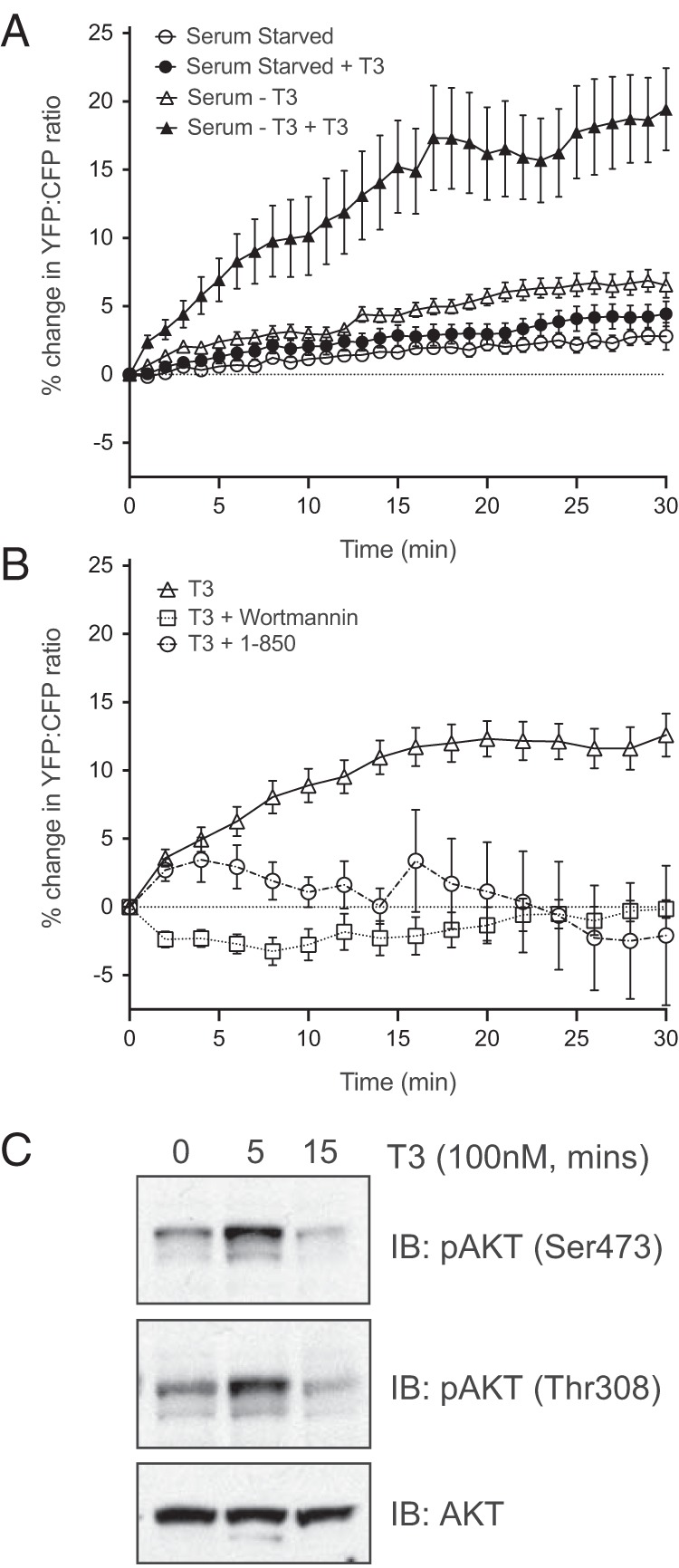

To measure PIP3 production directly in live cells on the same time scale that thyroid hormone increases Kv11.1 channel activity (24), we used a fluorescent indicator of PIP3 (25), which is based on CFP and YFP separated by the pleckstrin homology domain of the Akt protein kinase, a downstream effecter of PIP3 (13). PIP3 binding to the pleckstrin homology domain increases FRET from CFP to YFP.

To test this indicator on signaling by native thyroid hormone receptors, we used rat pituitary GH4C1 cells, which was the first in vitro cell system that was shown to respond to thyroid hormone (28). When GH4C1 cells that had been infected with a virus encoding the indicator were maintained in serum from thyroidectomized animals, treatment with 100 nM T3 rapidly increased the FRET response by more than 15% (Figure 1A). The increase in FRET response was already significant 1 minute after adding T3 and reached a plateau in less than 15 minutes. In contrast, when cells were maintained in serum-free medium, separate addition of T3 alone or of thyroid hormone-depleted serum produced much smaller responses (Figure 1A). Although we used a supramaximal concentration of hormone to stimulate the cells, the increase in the FRET signal was blocked completely by 3 μM 1–850 (Figure 1B), an antagonist of thyroid hormone binding to zinc finger thyroid hormone receptors (29), and by 50 nM wortmannin (Figure 1B), a competitive antagonist of the active site of PI3K (30). This confirmed that the increase in FRET elicited by 100 nM T3 involved T3 binding to a canonical receptor protein and activation of PI3K. Furthermore, the increase in PIP3 that we infer from the change in FRET signal was sufficient to initiate signaling in less than 5 minutes. PIP3 signaling activates the Akt protein kinase by stimulating its phosphorylation on Thr 308 and Ser 473 (13), which we detected with phosphospecific antibodies. Five minutes after the addition of thyroid hormone, the proportion of Akt that was phosphorylated on both residues increased (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Thyroid hormone (T3) stimulates PIP3 production in rat pituitary GH4C1 cells. A, Cells that had been serum starved overnight were treated with serum-free medium minus or plus 100 nM T3 or with serum from thyroidectomized animals without or with 100 nM T3 (n = 8). Only the latter treatment produces a significant increase in PIP3 levels, which was measured as the percentage change in the ratio of YFP to CFP emission (FRET) from the indicator after the CFP excitation. B, The increase in FRET was prevented by preincubating cells for 10 minutes in either 3 μM 1–850 to block hormone binding to the receptor (n = 4) or 50 nM wortmannin to block PI3K (n = 4). C, The increase in PIP3 produced by 100 nM T3 was sufficient to increase Akt phosphorylation on Ser 473 and on Thr 308 within 5 minutes. A representative blot is shown from one of four separate experiments. IB, immunoblotting.

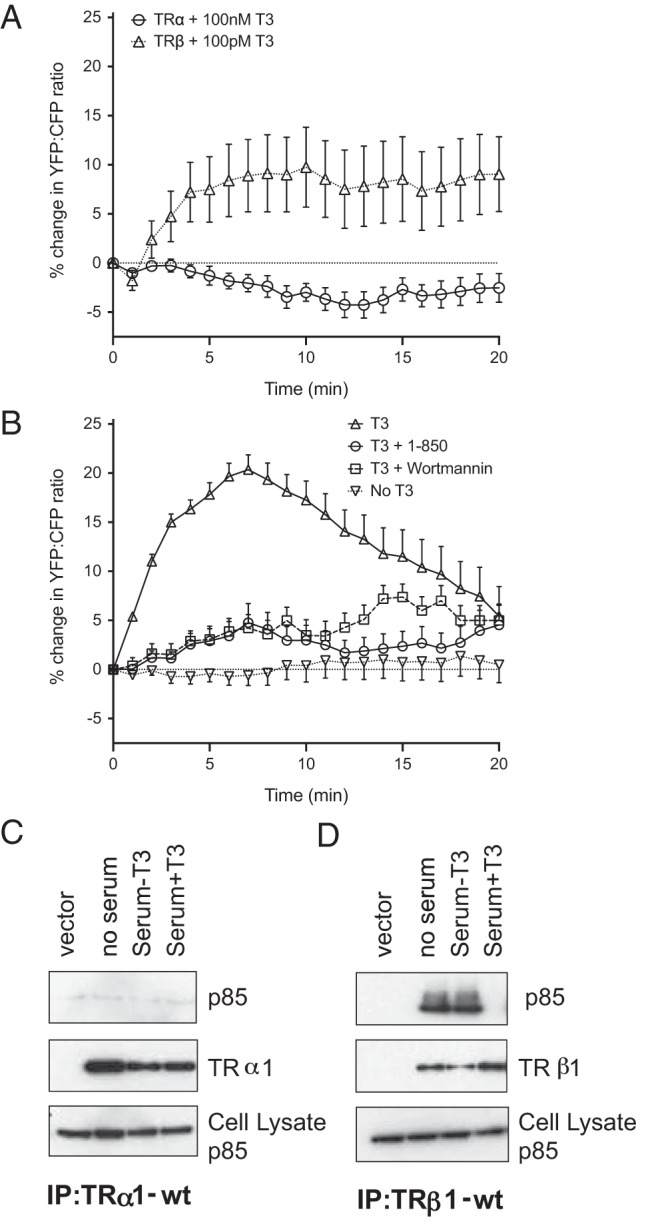

Although previous studies have also reported the stimulation of PI3K signaling by TRα (18, 19), we were able to reconstitute rapid PI3K-dependent regulation of Kv11.1 channels in CHO cells only with TRβ (24). Because the GH4C1 cells express both TRα and TRβ, we repeated the FRET measurements on CHO cells (Figure 2), which do not express detectable levels of either receptor unless they are transfected with plasmids encoding recombinant proteins. In CHO cells expressing recombinant human TRβ1, concentrations of T3 as low as 0.1 nM reproducibly elicited rapid global FRET increases (Figure 2A). The FRET response to 100 nM T3 in CHO cells was larger, but it was also inhibited almost completely by 1–850 and by wortmannin (Figure 2B). In contrast, in CHO cells expressing TRα instead of TRβ1, even supramaximal concentrations of T3 up to 100 nM did not elicit increases in FRET on this time scale (Figure 2A). This result is consistent with our binding studies on the same time scale, which show that, in the absence of hormone, immunoprecipitation of TRβ1, but not TRα, pulls down native p85 from CHO cell lysates (Figure 2, C and D). When hormone is added, the complex dissociates within 5 minutes (Figure 2D), as reported previously (21, 24).

Figure 2.

Thyroid hormone stimulates PIP3 production in CHO cells expressing human TRβ1. A, CHO cells expressing TRβ1 show reproducible increases in FRET in response to 0.1 nM T3 (n = 4), but cells expressing TRα did not respond significantly to 100 nM T3 over 20 minutes (n = 4). B, The increase in FRET produced by 100 nM T3 on cells expressing TRβ1 was prevented by preincubating cells for 10 minutes in either 3 μM 1–850 or 50 nM wortmannin (n = 4). C, Immunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged TRα from CHO cell lysates did not bring down any p85. D, In contrast, immunoprecipitation of the FLAG-tagged TRβ1 pulled down native p85 in the lysate. Subsequent addition of the hormone (far right lane) eliminates the association of p85 with TRβ1. Samples in panels C and D were run on the same gel for ease of comparison. A representative blot is shown from one of three separate experiments. IP, immunoprecipitation; wt, wild type.

The cellular distribution of TRβ depends on serum and thyroid hormone

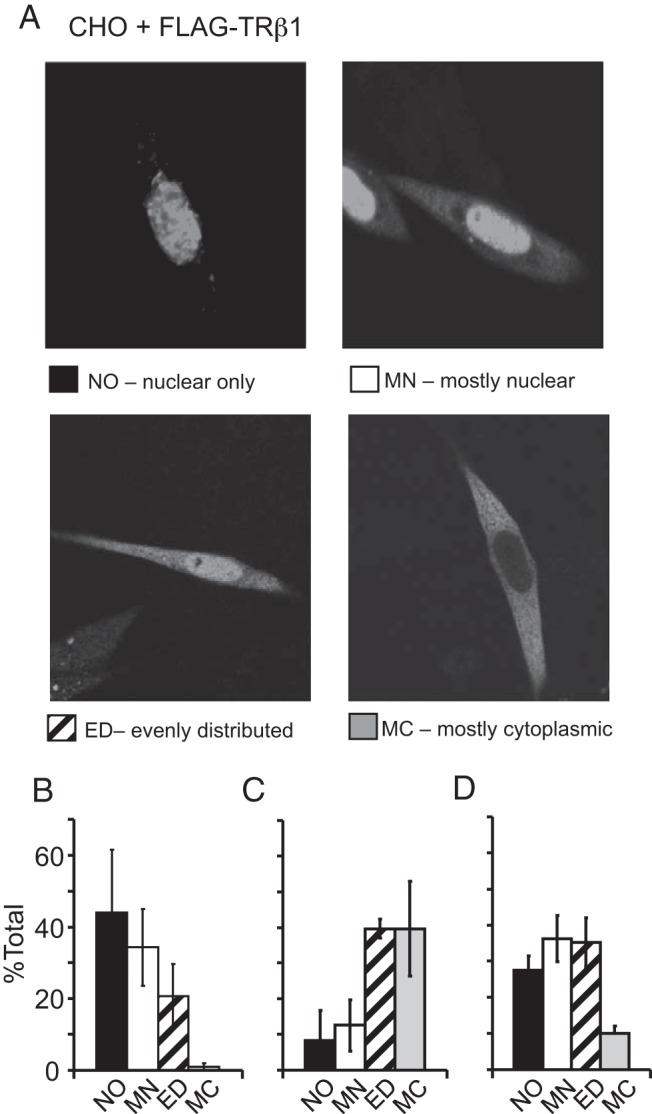

To have a physiological impact on global PI3K activity, a significant fraction of TRβ would have to be present in the cytoplasm. Although an early biochemical study reported as much as half of thyroid hormone binding proteins in the cytoplasmic fraction of cell homogenates (31), subsequent studies of nuclear receptor proteins in situ with green fluorescent protein attached have found them predominantly in the nucleus (32, 33), even though they move rapidly back and forth between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. To alleviate concerns that green fluorescent protein might interfere with PI3K association, we FLAG-tagged TRβ1 and used immunocytochemistry and confocal fluorescence microscopy to visualize its location in fixed cells (Figure 3). When the expression level of the FLAG-tagged receptor was limited to prevent the saturation of the cells, each cell could be assigned to one of four possible distributions that are illustrated in Figure 3A: nuclear only, mostly nuclear, evenly distributed, and mostly cytoplasmic. Every dish of cells had examples of each of these four patterns of receptor distribution, but the relative frequency varied over a wide range, depending on the culture conditions.

Figure 3.

The cellular distribution of TRβ1 under different culture conditions. A, Representative images of fixed CHO cells show the range of distribution patterns of FLAG-tagged TRβ1 proteins, which were stained using a FITC-conjugated antibody against FLAG. B–D, Proportion of cells with FLAG-TRβ1 distribution corresponding to the four distribution patterns in panel A. Each treatment was repeated four times, and each time two to four cells in 16 different areas of each plate (30–60 cells/plate) were counted in each condition. B, In serum-starved cells, TRβ1 is predominantly in the nucleus. C, In cells treated with thyroidectomized serum for 30 minutes, TRβ1 is predominantly in the cytoplasm. D, In cells treated with thyroidectomized serum plus 100 nM T3 for 30 minutes, TRβ1 is predominantly in the nucleus.

When the CHO cells were maintained overnight in serum-free medium before fixation, FLAG-tagged TRβ1 was located predominantly in the nucleus (Figure 3B) as expected for a nuclear receptor. However, when the cells were treated with T3-depleted serum from thyroidectomized animals for 30 minutes, there was a dramatic shift of receptor distribution to the cytoplasm (Figure 3C). In fact, in most cells in T3-free serum, there was more receptor in the cytoplasm than in the nucleus. Thus, under the same condition that is most conducive to thyroid hormone signaling through PI3K (Figure 1B), more than 50% of the receptors are localized in the cytoplasm in the absence of hormone. Nevertheless, the subsequent addition of thyroid hormone rapidly returned most of the FLAG-tagged receptors to the nucleus (Figure 3D). Therefore, we investigated how T3-depleted serum might promote both TRβ retention in the cytoplasm and PI3K stimulation by thyroid hormone.

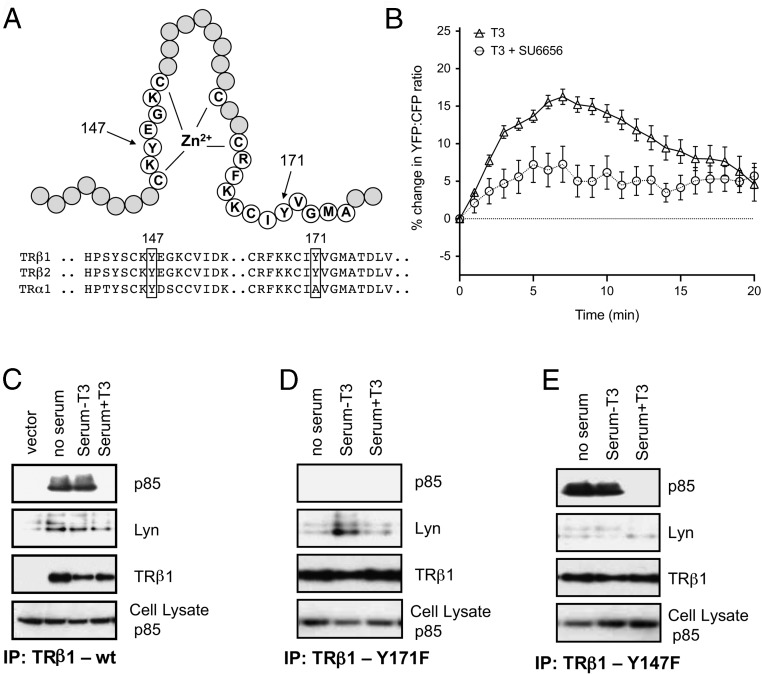

Tyrosine-dependent association of TRβ1 with p85 and Lyn

We noted previously (24) that TRβ, but not TRα, has a canonical SH2 recognition sequence, YVGM, at the end of the second zinc finger loop (Figure 4A), which could be phosphorylated by tyrosine kinases that are activated by the growth factors in serum. Src kinase activity has been shown to be required for T3 signaling through PI3K in alveolar epithelial cells (12), and TRβ has been reported to be phosphorylated on tyrosine (34), but the specific residues were not determined. The p85 subunit of PI3K contains two well-characterized SH2 domains, one of which selectively recognizes phosphorylated tyrosine in the sequence YVGM (13). In support of our hypothesis, we observed that pharmacological inhibition of Src family kinases with 200 nM SU6656 in our CHO cells reduced PIP3 production by thyroid hormone (Figure 4B). More importantly, when we mutated Y171 to phenylalanine, TRβ1 association with p85 was eliminated (Figure 4, C and D).

Figure 4.

Tyrosine-dependent binding of TRβ1 to p85. A, Schematic representation of the second TRβ1 zinc finger and the locations of Y147 and Y171. B, Time course of PIP3 production in response to 100 nM T3 in CHO cells expressing TRβ1 and in cells that were preincubated with 200 nM SU6656, a Src kinase inhibitor (n = 4). C–E, Mutant and wt TRβ1 proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates with anti-FLAG antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. Levels of coimmunoprecipitated p85 or Lyn were visualized in samples. Samples in panels C–E were run on the same gel for ease of comparison. A representative blot is shown. IP, immunoprecipitation; wt, wild type.

We attempted to confirm the phosphorylation of Y171 with mass spectrometry. We observed 107 spectra corresponding to 16 unique peptides from TRβ1 with a spectrum mill distinct summed MS/MS search score of 237.9 and 32% sequence coverage, but peptides containing Y147 or Y171 were never observed. However, we repeatedly identified the Src family kinase, Lyn, in the immunoprecipitates of TRβ1 from CHO cells by mass spectrometry. The spectrum mill distinct summed MS/MS search score of 27.6, corresponding to four spectra and three unique peptides and 5% sequence coverage, is modest, but we confirmed Lyn's presence by immunoblot (Figure 4). The Lyn tyrosine kinase is a well-known activator of the PI3K pathway (35, 36). Integrin receptors stimulate Src kinases through a KYEGK motif (37), and TRβ1 contains a KYEGK motif at Y147 nearby YVGM (Figure 4A). We also observed a TRβ1 association with Lyn in the Western blots of the immunoprecipitates of TRβ1 from CHO cells (Figure 4C). When we mutated Y147 to phenylalanine, association of TRβ1 with Lyn, but not with p85, was eliminated (Figure 4, D and E). Thus, in CHO cells the TRβ receptor for thyroid hormone binds both the p85 subunit of the PI3K and the Lyn protein kinase through distinct, canonical phosphotyrosine motifs.

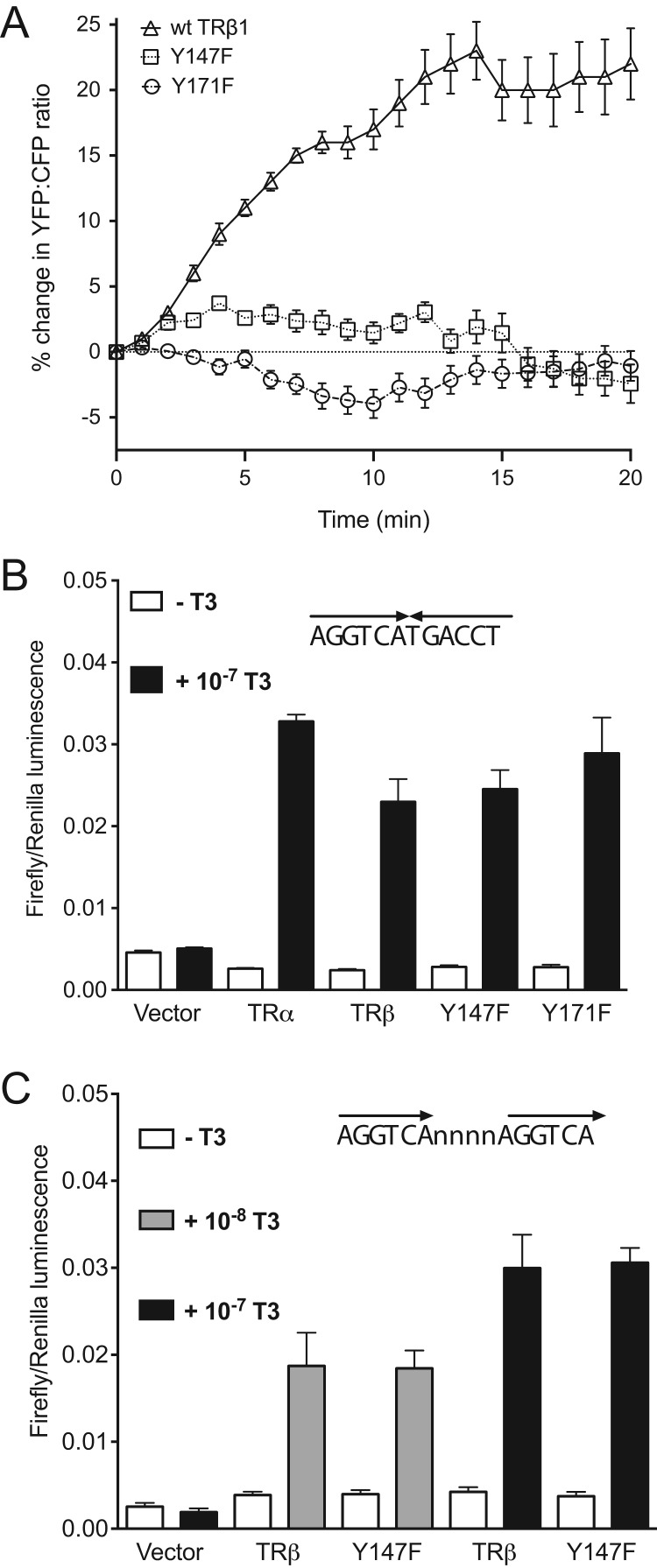

We tested the physiological relevance of these motifs in two ways. First, we asked whether the mutant TRβ1 receptors, Y147F and Y171F, could reconstitute the hormonal stimulation of PI3K and transcriptional activation in the mammalian cell lines in vitro (Figure 5). As expected, neither mutant supported increases in PIP3 in response to thyroid hormone in CHO cells (Figure 5A). In contrast, both mutants were just as effective as wild-type receptors in stimulating thyroid hormone-dependent luciferase gene expression in CV-1 cells (Figure 5, B and C). We tested two different thyroid hormone response elements (TREs), both of which contained two half-sites of six nucleotides (5): a TRE with contiguous palindromic half-sites (Figure 5B) and a TRE with direct repeats separated by a four nucleotide spacer (Figure 5C). In both cases the TREs were stimulated just as effectively by the mutant receptors. Thus, despite being located in the DNA-binding domain of the second zinc finger of TRβ, the Y147F and Y171F mutations did not interfere with direct DNA binding, which is consistent with their spatial location in published structures of the TRβ heterodimer (38).

Figure 5.

Both Y147 and Y171 are required for TRβ regulation of PI3K but not for binding to thyroid hormone response elements. A, Time course of PIP3 production in response to 100 nM T3 in CHO cells expressing TRβ1 or Y147F or Y171F mutants. B and C, Thyroid hormone-dependent transcription of luciferase reporter constructs containing a minimal promoter downstream of tandem TREs coexpressed in CV-1 cells with wild-type TRα, TRβ1, or the mutants in response to 10 or 100 nM T3 for 18 hours. The values were normalized to the T3-independent expression of Renilla luciferase and plotted as bar graphs showing the average and SEM of six measurements from three separate experiments run in duplicate with independent transfections. In all cases thyroid hormone produced a significant increase in transcription, but wild-type and mutant receptors were equally effective. B, The TRE was two contiguous palindromic half-sites, AGGTCATGACCT. The differences between wild type and mutant were not significant (TRβ1 vs Y147F, P = .69; TRβ1 vs Y171F, P = .25). C, The TRE was two direct repeats separated by a four-nucleotide spacer (DR4), AGGTCAnnnnAGGTCA. The differences between wild type and mutant were not significant at either concentration of T3 (10 nM T3, TRβ1 vs Y147F, P = .95; 100 nM T3, TRβ1 vs Y147F, P = .89).

TRβ signaling through PI3K in vivo

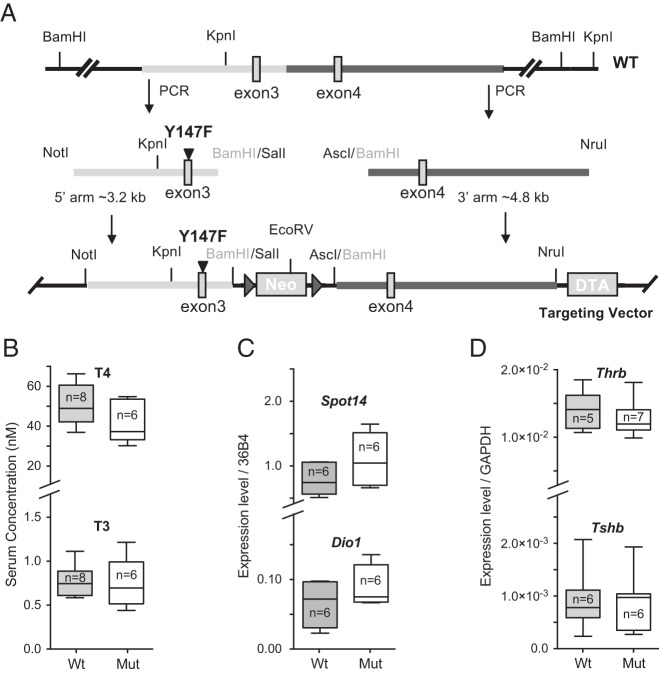

The ability to abrogate TRβ signaling through PI3K independently of TRβ's direct effects on gene transcription allowed us to test the physiological relevance of thyroid hormone signaling through PI3K for brain development in vivo. We reasoned that blocking the binding of TRβ to p85 by mutating Y171 might eliminate any dominant-negative effect of the mutant, in much the same way that receptor knockdown proved much less deleterious to the organism than hormone withdrawal (5, 6), presumably because many of the effects of the receptor on gene expression are mediated by binding of the unliganded receptor. Therefore, we created a novel mouse line (TRβ147F; see Materials and Methods) with a targeted mutation knocked into the Thrb gene (Figure 6A) to substitute phenylalanine for tyrosine at residue 147 of TRβ1, which prevents Lyn binding to the mutant receptor (Figure 4E). In this mouse line, the KYEGK recognition domain for the Src family kinase is also mutated to KFEGK in TRβ2, but due to alternate splicing of the TRβ2 transcript 5′ to the mutation, the same phenylalanine is residue 161 in TRβ2.

Figure 6.

Mutant and wild-type animals show no differences in thyroid hormone homeostasis or gene regulation. A, Schematic of part of the Thrb locus with relevant restriction sites. Two homology arms were generated by PCR and the A-to-T mutation in exon 3 was introduced. The 5′ arm and 3′ arm were cloned upstream and downstream of a floxed neo gene, respectively. The final ES cell targeting vector was linearized with NotI before electroporation and contained a diphtheria toxin gene (DTA) for negative selection of random recombination. B–D, Data were presented in box (25%–75%) and whisker (5%–95%) plots showing the median value as a horizontal line. The n values are given in the Figure. B, Total T4 and T3 levels in serum from wild-type and mutant mice as determined by mass spectrometry are not significantly different (P = .13 for T4, and P = .87 for T3. C, Expression levels of Spot14 and Dio1 in liver from wild-type and mutant as measured by qPCR using Rplp0 (36B4) as a standard are not significantly different (P = .13 for Spot14, and P = .21 for Dio1). D, Expression levels of Thrb in the cortex and Tshb in the pituitary from wild-type and mutant mice as measured by qPCR using GAPDH as a standard are not significantly different (P = .19 for Thrb, and P = .88 for Tshb). mut, mutant; wt, wild type.

The homozygous TRβ147F animals are viable in the controlled vivarium environment and breed normally with no overt phenotypes. We confirmed that the mutation did not alter total circulating levels of T4 or T3 by mass spectrometry of serum samples from 4-month-old mice (Figure 6B). Concentrations of T4 and T3 were in the range of previously reported measurements (27), and, more importantly, there were no significant differences between the two groups (T4: WT vs Mut, P = .13; T3: WT vs Mut, P = .87).

In an effort to determine whether the Y147F mutation interfered with the regulation of genes that are known to be controlled by TRβ binding in vivo, we measured the mRNA levels of Spot14 and Dio1 in the liver (39) and Tshb in the pituitary (40). However, we found no significant differences in any of these genes between wild-type and mutant animals (Figure 6, C and D), indicating that thyroid hormone homeostasis and nuclear signaling by TRβ were not affected by the mutation. mRNA levels for Thrb in the cortex of postnatal days 12–17 mice also showed no significant difference between wild-type and mutant animals (Figure 6D).

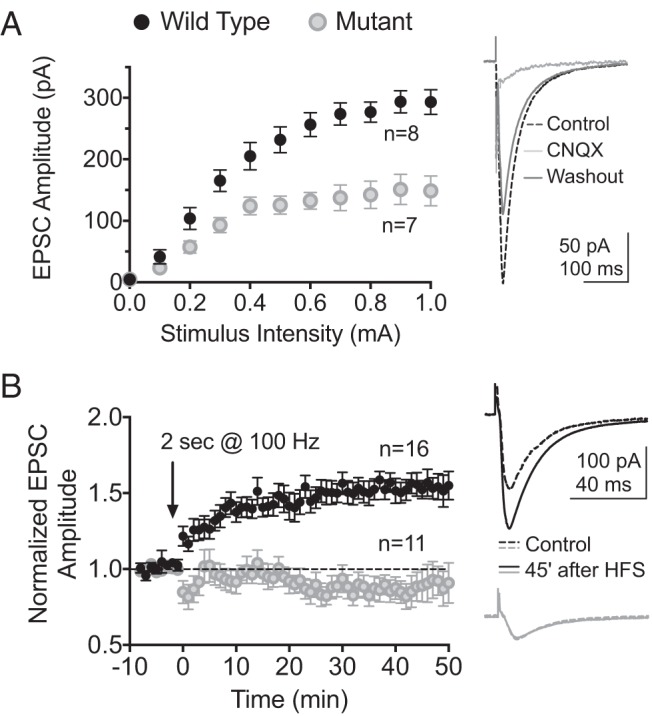

In contrast, we observed dramatic impairments in synaptic strength and plasticity in acutely isolated slices of hippocampi from postnatal day 12–18 TRβ147F mice (Figure 7). The CA1 area of the hippocampus is one of the most extensively studied brain areas for understanding the mechanisms of synaptic plasticity (41), and thyroid hormone has been shown to stimulate PI3K activity in the hippocampus (42). In whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from CA1 pyramidal neurons, EPSCs in response to Schaffer collateral stimulation were uniformly smaller by 50% at all stimulus strengths in slices from the mutant mice relative to those from controls (Figure 7A). The identity of these currents as glutamatergic synaptic responses was confirmed by reducing their amplitude greater than 90% with a bath application of 10 μM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), which is a competitive antagonist of 2-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA)/kainate receptor channels (43). Briefly, high-frequency stimulation of the Schaffer collaterals has been shown to produce long-term synaptic potentiation (LTP) at these synapses (44). We replicated this phenomenon in acute slices from wild-type animals: submaximal baseline EPSCs that averaged 151 ± 11 pA (n = 16) increased more than 50% after two 1-second periods of 100 Hz separated by 20 seconds, and this effect persisted for more than 40 minutes (Figure 7B). In contrast, high-frequency stimulation under identical conditions did not potentiate the submaximal basal EPSCs in hippocampal slices from TRβ147F mice, which averaged 97 ± 13 pA (n = 11) before stimulation (Figure 7B). Thus, when TRβ signaling through PI3K was blocked throughout development, the maturation and plasticity of the Schaffer collateral synapses from CA3 to CA1 pyramidal neurons in the postnatal mouse hippocampus was impaired dramatically without any changes in circulating levels of T4 or T3.

Figure 7.

Y147F mice have decreased synaptic strength and do not show LTP in response to high-frequency stimulation. A, Input-output curve shows a decrease in the synaptic strength in the mutant animal vs wild type. Insert shows the measured response is blocked almost completely by 10 μM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), an antagonist of 2-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazol propionic acid glutamate receptors. B, Mutant animals also fail to produce LTP in response to high frequency stimulation (two 1 sec periods of 100 Hz stimuli separated by 20 sec). Insert shows representative traces of the recordings at two time points.

Discussion

Our data are consistent with a mechanism in which TRβ acts as a cytoplasmic, phosphotyrosine-dependent scaffold for the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K and the Src kinase Lyn. Binding of the thyroid hormone results in the dissociation of the complex, which allows PI3K activity to increase and TRβ to move to the nucleus, in which it regulates transcription. However, PI3K-initiated signaling cascades also regulate gene expression (13, 14), so future studies of gene expression by the thyroid hormone will need to investigate which genes are regulated directly by TRβ binding in the nucleus and which genes are regulated indirectly by TRβ signaling in the cytoplasm through PI3K (45).

In this study, we used a fluorescent reporter of PIP3 production to demonstrate directly that the thyroid hormone stimulates the activity of the PI3K in live cells on the same time scale as the hormone's rapid physiological effect on Kv11.1 potassium channel activity, which also depends on PI3K and TRβ (24). In previous studies of PI3K stimulation by the thyroid hormone, PIP3 accumulation was measured indirectly, either by the appearance of downstream phosphoproteins or by the accumulation of PIP3 in homogenates over several hours. In our experiments, we focused on time points less than 15 minutes and used serum from thyroidectomized animals to separate the effects of thyroid hormone from other growth factors, which regulate the activity of PI3K through tyrosine kinases. Under these conditions, most TRβ proteins reside in the cytoplasm (Figure 3), and the thyroid hormone decreased the association between TRβ and p85 on the same time scale and under the same conditions that it stimulated PIP3 production.

We also show that the association between TRβ and the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K, which we reported previously (24), depends on the canonical SH2 binding motif in TRβ, IYVGM, which is not present in TRα. Consistent with this structural difference, we did not observe any association between TRα and p85 or any stimulation of PI3K activity by TRα on the time scale of our experiments. However, longer exposure to hormone or differences in cell types might explain the activation of PI3K by TRα and T4 through less direct mechanisms in other studies.

We also identified a Src-family protein tyrosine kinase, Lyn, as part of the TRβ-PI3K complex in CHO cells, and showed that mutating the canonical Lyn binding motif in TRβ, KYEGK, blocked thyroid hormone signaling through PI3K, even though it did not prevent association between TRβ and p85. In neurons, Src family kinase members other than Lyn might also complex with TRβ. Although Y147 is located in the D box that contributes to response element recognition (46), and although a previous study reported effects of serine phosphorylation at a nearby site, S142, on transcription in vitro (47), mutating Y147 to phenylalanine had no significant effect on direct regulation of transcription by TRβ binding to its response elements (Figure 5) or on our in vivo assays (Figure 6) of genes from the liver and pituitary that are known to be regulated directly by TRβ. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that this very conservative mutation of one amino acid from tyrosine to phenylalanine in the second zinc finger of TRβ might produce more subtle changes in DNA binding specificity, dimerization, or interaction with transcriptional cofactors.

Interestingly, the tyrosine motifs in TRβ, which we have shown here to be essential for signaling through PI3K, are conserved in all mammalian species for which genome data are available, including opossum (XP_001369854) and platypus (XP 001506732), but only in two nonmammalian species, gecko (AB204862) and axolotl (AY174872). The tyrosines are not conserved in orthologous TRβ receptors in the chicken, alligator, mudpuppy, clawed toad, eel, zebrafish, ascidian or sea urchin. Thus, neither frogs nor zebrafish would be appropriate models to study the relevance of thyroid hormone signaling for mammalian neural development because they are predicted not to signal through PI3K. For mammals, however, our model provides a simple, unique mechanism for integrating regulation of growth and metabolism at the cellular level by thyroid hormone signaling through zinc finger transcription factors and growth factor signaling through receptor tyrosine kinases. Only when both growth factors and thyroid hormone are present at the same time, will maximal stimulation of PI3K be produced. The specificity that we have observed between TRβ and signaling through PI3K is also consistent with reports that selective TRβ agonists are highly effective stimulators of metabolism (48), which is also regulated by PI3K (13).

Finally, we tested the physiological relevance of chronically blocking TRβ signaling through PI3K during mammalian brain development by making a mouse line with a mutation at the Lyn binding site in TRβ, Y147F in the sequence KYEGK. Although baseline measures of thyroid hormone homeostasis and gene expression were normal in the mutant mice, the maturation and plasticity of Schaffer collateral synapses on CA1 pyramidal neurons were impaired significantly (Figure 7). These effects on hippocampal slices are as large as those reported in rats that were made hypothyroid chemically by completely blocking thyroxine synthesis with propylthiouracil (49). Thus, thyroid hormone signaling through PI3K appears to be an essential mechanism underlying normal synaptic maturation and plasticity in the postnatal mouse hippocampus. However, as noted above, we cannot formally exclude some more subtle effect of the mutation on the regulation of a currently unknown gene that plays as central a role in synaptic development as PI3K. On the other hand, our results do categorically rule out a role for other thyroid hormone receptors in this particular aspect of synaptic maturation in the mouse hippocampus, such as TRα or integrins that have also been reported to signal through PI3K. In either case, given the importance of thyroid hormone signaling for human brain development and adult metabolism, future studies will need to investigate whether PI3K stimulation by thyroid hormone is also susceptible to disruption by environmental toxicants, as we have postulated (16).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Sheue-Yann Cheng (National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health) for providing the plasmid constructs PCLC61-TRα and pTK-Pal-Luc reporter, Brian Scott (Dillman laboratory at University of California, San Diego) for providing the T4T-Luc reporter, and Dr Jin Zhang (Department of Pharmacology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland) for providing the PIP3 reporter construct. We thank James A Clark (Comparative Medicine Branch at National Institute of Environmental Health and Sciences) for performing the orbital bleeds, and S. Dudek (Laboratory of Neurobiology at NIEHS) for advice on slice recordings. We also acknowledge the Protein Microcharacterization facility, Fluorescent Microscopy and Imaging Center, Protein Expression, Microarray, Viral Vectors, and Sequencing core facilities of National Institute of Environmental Health and Sciences for their technical contribution.

Author contributions include the following: S.G., N.P.M., and D.L.A. conceived the project and made initial hypotheses. N.P.M. and E.L.S. made immunoblots and FRET measurements. E.M.F.d.V. and B.G. carried out the transcriptional analysis. B.G. and E.L.S. genotyped the mice. F.M. and C.E. carried out the electrophysiology. J.G.W. and H.M.S. carried out the mass spectrometry. N.M., E.M.F.d.V., B.G., and D.L.A. wrote the paper.

This work was supported by Award Z01-ES102285 from the Intramural Program at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (to D.L.A.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

For News & Views see page 3206

- ACSF

- artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- CFP

- cyan fluorescent protein

- CHO

- Chinese hamster ovary

- EPSC

- excitatory postsynaptic current

- ES

- embryonic stem

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- FRET

- Forster resonance energy transfer

- LTP

- long-term synaptic potentiation

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PIP3

- phosphatidylinositol (3, 4, 5)-trisphosphate

- qPCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

- TBS

- Tris-buffered saline

- T3

- 3,5,3′ triiodothyronine

- TRE

- thyroid hormone response element

- YFP

- yellow fluorescent protein.

References

- 1. Tata JR. One hundred years of hormones. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:490–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kousteni S, Bellido T, Plotkin LI, et al. Nongenotropic, sex-nonspecific signaling through the estrogen or androgen receptors: dissociation from transcriptional activity. Cell. 2001;104:719–730 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Losel RM, Falkenstein E, Feuring M, et al. Nongenomic steroid action: controversies, questions, and answers. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:965–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hammes SR, Levin ER. Recent advances in extranuclear steroid receptor actions. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4489–4495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yen PM. Physiological and molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1097–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Shea PJ, Williams GR. Insight into the physiological actions of thyroid hormone receptors from genetically modified mice. J Endocrinol. 2002;175:553–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tata JR. The road to nuclear receptors of thyroid hormone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:3860–3866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bassett JHD, Harvey CB, Williams GR. Mechanisms of thyroid hormone receptor specific nuclear and extranuclear actions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;213:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davis PJ, Leonard JL, Davis FB. Mechanisms of nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Storey NM, O'Bryan JP, Armstrong DL. Rac and Rho mediate opposing hormonal regulation of the ether-a-go-go-related potassium channel. Curr Biol. 2002;12:27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Incerpi S, De Vito P, Luly P, Spagnuolo S, Leoni S. Short-term effects of thyroid hormones and 3,5-diiodothyronine on membrane transport systems in chick embryo hepatocytes Endocrinology. 2002;143:1660–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lei J, Mariash CN, Ingbar DH. 3,3′,5-Triiodo-L-thyronine up-regulation of Na,K-ATPase activity and cell surface expression in alveolar epithelial cells is Src kinase- and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47589–47600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vanhaesebroeck B, Stephens L, Hawkins P. PI3K signaling: the path to discovery and understanding. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:606–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Waite K, Eickholt BJ. The neurodevelopmental implications of PI3K signaling. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;346:245–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Armstrong DL. Implications of thyroid hormone signaling through the phosphoinositide-3-kinase for xenobiotic disruption of human health. In: Gore A, ed. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals: From Basic Research to Clinical Practice. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2007:193–202 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cheng SY, Leonard JL, Davis PJ. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions. Endocr Rev. 2010;31:139–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Simoncini T, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Brazil DP, Ley K, Chin WW, Liao JK. Interaction of oestrogen receptor with the regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Nature. 2000;407:538–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hiroi Y, Kim HH, Ying H, et al. Rapid non-genomic actions of thyroid hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14104–14109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Saelim N, John LM, Wu J, et al. Non-transcriptional modulation of intracellular Ca2+ signaling by ligand stimulated thyroid hormone receptor. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:915–924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cao X, Kambe F, Moeller LC, Refetoff S, Seo H. Thyroid hormone induces rapid activation of Akt/protein kinase B-mammalian target of rapamycin-p70S6K cascade through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in human fibroblasts. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:102–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moeller LC, Dumitrescu AM, Refetoff S. Cytosolic action of thyroid hormone leads to induction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a and glycolytic genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2955–2963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Verga-Falzacappa C, Petrucci E, Patriarc V, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor TRβ1 mediates Akt activation by T3 in pancreatic β cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007;38:221–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Storey NM, Gentile S, Ullah H, et al. Rapid signaling at the plasma membrane by a nuclear receptor for thyroid hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5197–5201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ananthanarayanan B, Ni Q, Zhang J. Signal propagation from membrane messengers to nuclear effectors revealed by reporters of phosphoinositide dynamics and Akt activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15081–15086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Choi JH, Williams J, Cho J, Falck JR, Shears SB. Purification, sequencing, and molecular identification of a mammalian PP-InsP5 kinase that is activated when cells are exposed to hyperosmotic stress. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30763–30775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang D, Stapleton HM. Analysis of thyroid hormones in serum by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;397:1831–1839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Samuels HH, Tsai JS, Cintron R. Thyroid hormone action: a cell-culture system responsive to physiological concentrations of thyroid hormones. Science. 1973;181:1253–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schapira M, Raaka BM, Das S, et al. Discovery of diverse thyroid hormone receptor antagonists by high-throughput docking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7354–7359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Walker EH, Pacold ME, Perisic O, et al. Structural determinants of phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition by wortmannin, LY294002, quercetin, myricetin, and staurosporine. Mol Cell. 2000;6:909–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oppenheimer JH. Thyroid hormone action at the cellular level. Science. 1979;203:971–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhu XG, Hanover JA, Hager GL, Cheng SY. Hormone-induced translocation of thyroid hormone receptors in living cells visualized using a receptor green fluorescent protein chimera. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27058–27063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baumann CT, Maruvada P, Hager GL, Yen PM. Nuclear cytoplasmic shuttling by thyroid hormone receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11237–11245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lin KH, Ashizawa K, Cheng SY. Phosphorylation stimulates the transcriptional activity of the human b1 thyroid hormone nuclear receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7737–7741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pleiman CM, Hertz WM, Cambier JC. Activation of phosphatidylinositol-3′ kinase by Src-family kinase SH3 binding to the p85 subunit. Science. 1994;263:1609–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ptasznik A, Prossnitz ER, Yoshikawa D, Smrcka A, Traynor-Kaplan AE, Bokoch GM. A tyrosine kinase signaling pathway accounts for the majority of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate formation in chemoattractant-stimulated human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25204–25207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Romzek NC, Harris ES, Dell CL, et al. Use of a β1 integrin-deficient human T cell to identify β1 integrin cytoplasmic domain sequences critical for integrin function. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2715–2727 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rastinejad F, Perlmann T, Evans RM, Sigler PB. Structural determinants of nuclear receptor assembly on DNA direct repeats. Nature. 1995;375:203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Machado DS, Sabet A, Santiago LA, et al. A thyroid hormone receptor mutation that dissociates thyroid hormone regulation of gene expression in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9441–9446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abel ED, Moura EG, Ahima RS, et al. Dominant inhibition of thyroid hormone action selectively in the pituitary of thyroid hormone receptor-β null mice abolishes the regulation of thyrotropin by thyroid hormone. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1767–1776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Malenka MC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004;44:5–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sui L, Wang J, Li BM. Administration of triodo-L-thyronine into dorsal hippocampus alters phosphorylation of Akt, mammalian target of rapamycin, p70S6 kinase and 4E-BP1 in rats. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:1065–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Honoré T, Davies SN, Drejer J, et al. Quinoxalinediones: potent competitive non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonists. Science. 1988;241:701–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schwartzkroin PA, Wester K. Long-lasting facilitation of a synaptic potential following tetanization in the in vitro hippocampal slice. Brain Res. 1975;89:107–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Moeller LC, Broecker-Preuss M. Transcriptional regulation by nonclassical action of thyroid hormone. Thyroid Res. 2011;4:56–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Umesono K, Evans RM. Determinants of target gene specificity for steroid/thyroid hormone receptors. Cell. 1989;57:1139–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lin HY, Zhang S, West BL, et al. Identification of the putative MAP kinase binding site in the thyroid hormone receptor-β1 DNA-binding domain. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7571–7579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baxter JD, Webb P, Grover G, Scanlan TS. Selective activation of thyroid hormone signaling pathways by GC-1: a new approach to controlling cholesterol and body weight. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15:154–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gilbert ME. Alterations in synaptic transmission and plasticity in area CA1 of adult hippocampus following developmental hypothyroidism. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;148:11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]