Abstract

The precise mechanism whereby epidermal growth factor (EGF) activates the serine-threonine kinase Akt and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 (mTORC1) remains elusive. Here, we report that the α subunits of the heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide–binding proteins (G proteins) Gαi1 and Gαi3 are critical for this activation process. Both Gαi1 and Gαi3 formed complexes with growth factor receptor binding 2 (Grb2)–associated binding protein 1 (Gab1) and the EGF receptor (EGFR) and were required for the phosphorylation of Gab1 and its subsequent interaction with the p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in response to EGF. Loss of Gαi1 and Gαi3 severely impaired the activation of Akt and of p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1, downstream targets of mTORC1, in response to EGF, heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor, and transforming growth factor α, but not insulin, insulin-like growth factor, or platelet-derived growth factor. In addition, ablation of Gαi1 and Gαi3 largely inhibited EGF-induced cell growth, migration, and survival, and the accumulation of cyclin D1. Overall, this study suggests that Gαi1 and Gαi3 lie downstream of EGFR, but upstream of Gab1-mediated activation of Akt and mTORC1, thus revealing a role for Gαi proteins in mediating EGFR signaling.

INTRODUCTION

The signaling pathway connecting the serine-threonine kinase Akt to the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 (mTORC1) plays a critical role in various normal and abnormal processes including growth, migration, metabolism, survival, and malignant transformation of the cell. These processes are mediated by growth factors such as epidermal growth factor (EGF), heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF), and transforming growth factor–α (TGF-α), as well as insulin, insulin-like growth factor (IGF), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) (1, 2). Activation of Akt by these growth factors requires the phosphorylation of Akt on both Thr308 (308T) and Ser473 (473S). Akt308T is phosphorylated by phosphatidylinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) on activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), whereas Akt473S is phosphorylated by mTORC2 (3).

Once Akt is activated, it phosphorylates tumor sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2), relieving its suppression of the guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) Rheb, which leads to the activation of mTORC1. Activated mTORC1 phosphorylates its targets, including the Cap-dependent protein translation inhibitor, elongation initiation factor 4 (eIF4)–binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), and the ribosome protein 6 kinase (p70S6K, S6K), which in turn phosphorylates S6, which leads to the initiation of the translation of messenger RNAs into proteins. Activated Akt also phosphorylates glycogen synthase kinase 3α (GSK-3α) and GSK-3β and the forkhead transcription factors 1 and 3 (FoxO1 and FoxO3), which lead to cell survival (4–6).

It is well established that insulin-and IGF-mediated activation of the Akt-mTORC1 pathway occurs indirectly through insulin receptor substrates, which bind to the p85 (regulatory) subunit of PI3K, leading to the activation of PI3K (7), whereas the PDGF receptor (PDGFR) binds directly to p85 (8, 9). EGF receptor (EGFR) signaling is mediated primarily by growth factor receptor binding 2 (Grb2)–associated binding protein 1 (Gab1), an adaptor protein that interacts with p85 and plays an essential role in activation of the PI3K-Akt-mTORC1 pathway (8–10). However, the precise mechanism by which the EGFR triggers activation of this pathway is unclear.

The heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide–binding proteins (G proteins) of the Gαi family, which were originally identified by their ability to inhibit adenylyl cyclase, are members of one of four families of G proteins (11). The Gαi proteins, which include Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3, among others, are highly similar, with more than 94% sequence identity between Gαi1 and Gαi3. Hormones and neurotransmitters use Gαi proteins to trigger physiological responses. Gαi proteins, originally thought to reside solely at the plasma membrane, have also been identified in intracellular compartments recently (12). Loss of Gαi2 leads to the development of inflammatory bowel disease, whereas deletion of both Gαi2 and Gαi3 in mice leads to death in utero (13). Gαi3 is required for the antiautophagic action of insulin in mouse liver. Gαi proteins are thought to play a role in EGF signaling based on its sensitivity to pertussis toxin (PTX), which inhibits the generation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) in rat hepatocytes (14–18). However, PTX does not appear to prevent EGF-induced activation of Akt (18–21), which has led to the conclusion that Gαi proteins are not involved in the activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway. Recently, the EGFR has emerged as a transducer in G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling, a process termed transactivation, in which the EGFR mediates GPCR-induced activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway (1). Here, we reinvestigated the requirement for Gαi proteins in the direct activation of the Akt-mTORC1 pathway by EGF.

RESULTS

Critical roles for Gαi proteins in the activation of Akt and mTORC1 by EGF and EGF family members

To explore roles for Gαi proteins in the mechanism of EGF-mediated stimulation of the Akt-mTORC1 pathway, we initially used mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from wild-type (WT) mice or from mouse embryos deficient in Gαi1, Gαi2, or Gαi3, as well as those from embryos doubly deficient in Gαi1 and Gαi3. Kinetic and dose-response experiments showed that MEFs lacking Gαi1 and Gαi3 [termed double-knockout (DKO) cells] were severely impaired in EGF-induced phosphorylation of Akt308T, Akt473S, GSK-3α(21S), and GSK-3β(9S), as well as the mTORC1 downstream targets 4E-BP1(65S), S6K(389T), and S6(235–236S) (Fig. 1, A and B). In contrast, loss of either Gαi1 or Gαi3 led to a small but considerable decrease in the phosphorylation of Akt473S, 4E-BP1(65S), and S6(235–236S) (Fig. 1C), whereas Gαi2-deficient MEFs did not show a clear defect in phosphorylation of Akt473S, 4E-BP1(65S), and S6K(389T) in response to EGF (Fig. 1D). This latter observation may be due to compensation by spontaneous overexpression of Gαi3 (13).

Fig. 1.

Gαi1 and Gαi3 are required for the activation of Akt and mTORC1 by EGF. WT and Gαi1, Gαi3 DKO MEFs were treated with different doses of EGF for 15 min (A) or with EGF (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times (B). Gαi1, Gαi3, pEGFR(1173Y), pAkt(473S), pAkt(308T), pGSK-3β(9S), pFoxo3(32T), pp70S6K(389T), pS6 (235/236S), p4E-BP1(65S), Akt1–2, S6, and EGFR were detected by Western blotting analysis. (C) WT, Gαi1-deficient, Gαi3-deficient, or DKO MEFs were treated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Gαi3, pAkt(473S), pS6(235/236S), p4E-BP1(65S), and Akt1–2 were detected by Western blotting analysis. (D) WT and Gαi2-deficient MEFs were treated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Gαi2, pAkt(473S), pS6K(389T), p4E-BP1(65S), and AKT1–2 were detected by Western blotting analysis. The experiments were repeated at least three times and similar results were obtained in each case.

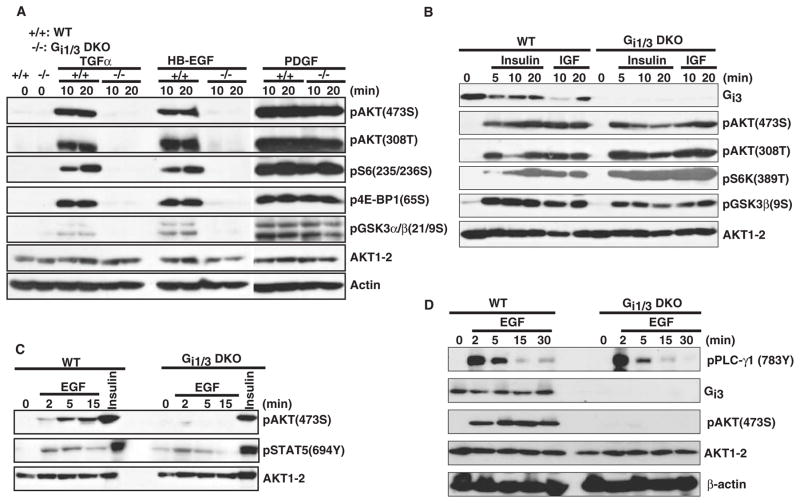

Next, we explored whether other growth factors known to activate Akt and mTORC1 also required Gαi proteins. Similarly to EGF, the EGF family members HB-EGF and TGF-α failed to induce phosphorylation of Akt308T, Akt473S, 4E-BP1(65S), GSK-3α (21S), GSK-3β(9S), and S6(235/236S) in DKO MEFs (Fig. 2A). In contrast, deficiency in both Gαi1 and Gαi3 had no effect on the phosphorylation of Akt308T, Akt473S, GSK-3β(9S), and S6K(389T) in response to insulin, IGF, and PDGF under our current experimental conditions (Fig. 2, A and B).

Fig. 2.

Loss of Gαi1 and Gαi3 severely impairs activation of Akt and mTORC1 by HB-EGF and TGF-α, but not by insulin, IGF, or PDGF. WT and DKO MEFs were treated with TGF-α (100 ng/ml), HB-EGF (100 ng/ml), PDGF-BB (25 ng/ml) (A), or with insulin (1 μg/ml) or IGF-1 (10 ng/ml) (B) for the indicated times. Gαi3, pAkt(308T), pAkt(473S), pGSK-3β(9/21S), pS6K(389T), pS6(235/236S), p4E-BP1(65S), Akt1–2, and β-actin were detected by Western blotting analysis. (C) EGF-or insulin-induced pSTAT5(694Y) and Akt(473S) in WT and DKO MEFs were detected by Western blotting analysis. (D) EGF-induced phosphorylation of PLC-γ(783Y) and Akt(473S) were determined by Western blotting. The experiments were repeated at least three times and similar results were obtained in each case.

To assess whether the defect in the activation of the Akt-mTORC1 pathway by EGF in DKO MEFs occurred at the level of the receptor, we examined autophosphorylation of EGFR and the activity of EGFR by measuring phosphorylation of its physiological substrates phospholipase C–γ1 (PLC-γ1) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5). Although the abundance of EGFR in DKO cells was lower than that in WT cells, both cell types responded equally to EGF as determined by measurement of phosphorylation of EGFR(1173Y) (Fig. 1B), indicating that Gαi proteins acted downstream of EGFR. Further, deficiency in both Gαi1 and Gαi3 had no apparent effect on the phosphorylation of STAT5(694Y) (Fig. 2C) or PLC-γ1(783Y) (Fig. 2D) in response to EGF. Taken together, these results show that Gαi1 and Gαi3 acted downstream of the EGFR and were required for the activation of Akt and mTORC1 by EGF and related family members.

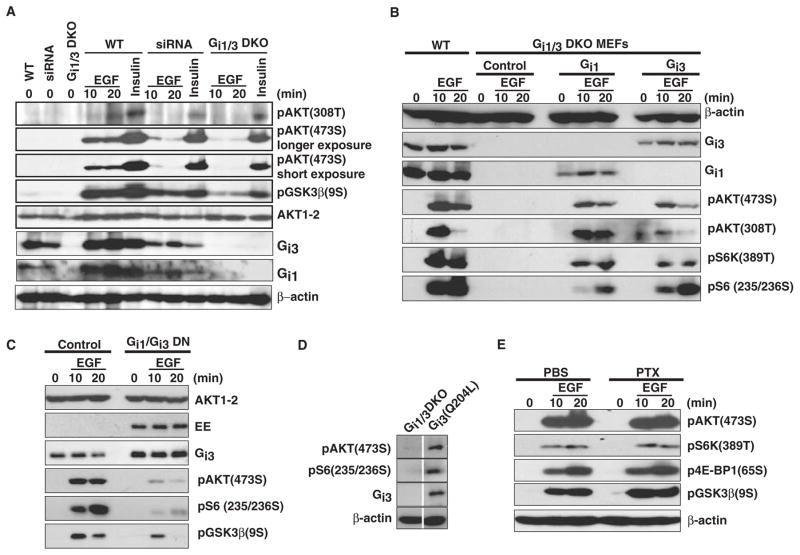

To rule out the possibility that the DKO MEFs behaved differently from WT MEFs, we verified these observations with RNA interference (RNAi) and dominant interference strategies. Combined knockdown of Gαi1 and Gαi3 impaired phosphorylation of Akt308T, Akt473S, and GSK-3β(9S) in response to EGF, but did not affect insulin signaling (Fig. 3A). Moreover, reconstitution of either Gαi1 or Gαi3 in DKO MEFs restored phosphorylation of Akt308T, Akt473S, S6K(389T), and S6(235/236S) in response to EGF (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Gαi1 and Gαi3 proteins are critical for the phosphorylation of Akt473S and 4E-BP1(65S) in response to EGF. (A) Knockdown of Gαi1 and Gαi3 decreases the activation of Akt by EGF, but not insulin. WT MEFs transfected with siRNA oligos specific for Gαi1 and Gαi3 and DKO MEFs were treated with EGF (100 ng/ml) or insulin (1 μg/ml) for the indicated times. pAkt(308T), pAkt(473S), pGSK-3β(S9), Akt1–2, β-actin, Gαi1, and Gαi3 were detected by Western blotting. (B) Exogenous Gαi1 and Gαi3 rescue the activation of Akt and 4E-BP1 in DKO MEFs in response to EGF. DKO MEFs were transfected with vectors encoding WT Gαi1 or Gαi3 (4 μg). Cells were treated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times. pAkt(308T), pAkt(473S), S6K(389T), S6(235/236S), β-actin, Gαi1, and Gαi3 were detected by Western blotting analysis. (C) Cotransfection of DN mutants of Gαi1 and Gαi3 inhibits the activation of Akt by EGF. WT MEFs were cotransfected with DN, EE-tagged Gαi1 and Gαi3 expression vectors (2 μg each) or were untransfected as controls followed by treatment with EGF (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times. pAkt(473S), pGSK-3β(9S), pS6K(389T), Akt1–2, EE tag, and Gαi3 were detected by Western blotting. (D) Constitutively active (CA) Gαi3(Q204L) induces the phosphorylation of Akt(473S) and S6(235/236S). DKO cells were transfected with a vector expressing Gαi3(Q204L). pAkt(473S), pS6(235/236S), Gαi3, and β-actin were determined by Western blotting analysis. (E) WT MEFs were pretreated overnight with pertussis toxin (PTX, 100 ng/ml) followed by treatment with EGF. pAkt(473S), pGSK-3β(9S), p4E-BP1(65S), pS6K(389T), and β-actin were detected by Western blotting. All transfection experiments were repeated at least twice and similar results were obtained in each case.

We next used a dominant interference strategy in which we substituted a conserved Gly (G) residue with Thr (T) in the G3 box of Gαi1 and Gαi3. Gαi proteins with these mutations compete with WT Gαi1 and Gαi3 proteins for binding to other proteins or reduce the response caused by WT Gαi1 and Gαi3 (22, 23). Overexpression of Gαi1(G202T) or Gαi3(G202T) substantially decreased phosphorylation of Akt473S, GSK-3β(9S), and S6(235/236S) in response to EGF compared to that in control cells (Fig. 3C). Alternatively, we also expressed constitutively active Gαi proteins that incorporated a Q204L mutation that impairs the GTPase activities of the mutant proteins. As expected, overexpression of Gαi3(Q204L) led to increased phosphorylation of Akt473S and S6(235/236S) in the absence of EGF compared to that in untransfected DKO cells (Fig. 3D). Consistent with previous studies, PTX had little effect on the phosphorylation of Akt473S, GSK-3β(9S), 4E-BP1(65S), and S6K(389T) in response to EGF (Fig. 3E), confirming that although adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP)-ribosylation of Gαi proteins interferes with GPCR-dependent signaling, it has no clear effect on EGFR signaling. Together, our observations show that Gαi1 and Gαi3 play a key role in EGF-mediated activation of the Akt-mTORC1 pathway.

Gαi proteins form a complex with EGFR and Gab1 and are required for EGF-dependent phosphorylation of Gab1 and its interaction with p85

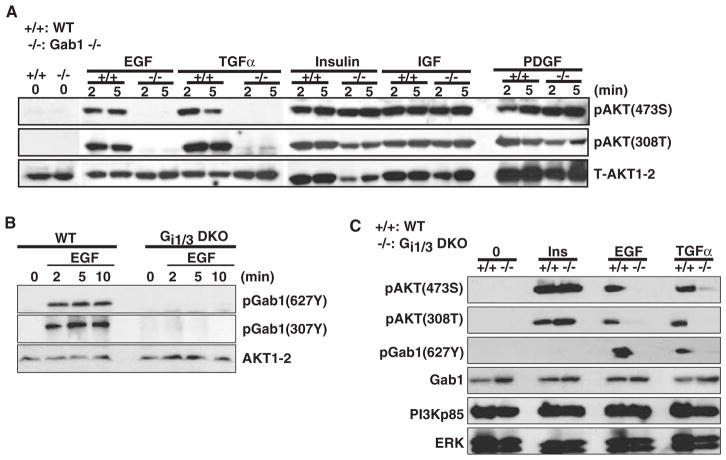

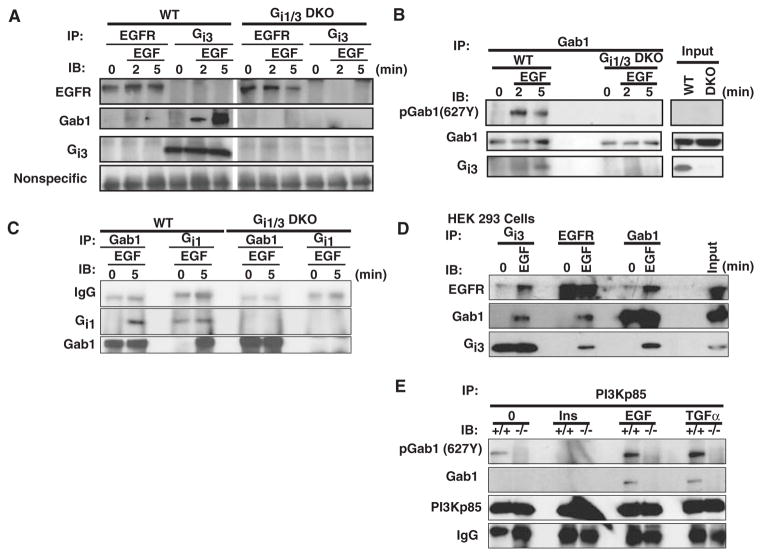

Gab1 is a docking protein that can be recruited to the receptor complex and then phosphorylated in response to EGFR activation. Phosphorylated Gab1 recruits downstream effectors such as p85, which leads to the activation of PI3K (24–27). As shown, loss of Gab1 severely impaired the phosphorylation of Akt308T and Akt473S in response to EGF and TGF-α, but not insulin, IGF, and PDGF (Fig. 4A) (24, 27). EGF-induced phosphorylation of Gab1(627Y) and Gab1(327Y), as well as TGFα-induced phosphorylation of Gab1(627Y), was largely impaired in DKO cells (Fig. 4, B and C), indicating that Gab1 acted downstream of Gαi proteins in the EGF pathway. Further, EGF induced the association of Gab1 with Gαi1 and Gαi3 (Fig. 5, A to D). Gab1 interacted with EGFR in WT but not DKO MEFs (Fig. 5A), suggesting that Gαi proteins are important for the association between Gab1 and EGFR. Although EGF triggered the formation of a complex between EGFR, Gab1, and Gαi3 in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells (Fig. 5D), such a complex was not readily detected in EGF-treated MEFs (Fig. 5A), which suggested that the interaction between Gαi proteins and EGFR might be either too transient or too weak to be detected in MEFs by conventional immunoprecipitation methods or that additional signaling protein(s) are present upstream of Gαi but downstream of EGFR in the EGF pathway. In addition, EGF induced the association of Gab1 with p85 in WT, but not in DKO MEFs (Fig. 5E), indicating that Gαi proteins were required for the interaction of Gab1 with p85, which resulted in the activation of PI3K. Overall, our findings suggest that an interaction between Gαi proteins and Gab1 is required to mediate Gab1 and PI3K activity in response to EGF.

Fig. 4.

EGF-induced phosphorylation of Gab1 depends on Gαi1 and Gαi3. (A) Gab1 is required for the activation of Akt by EGF and TGF-α, but not by insulin, IGF, and PDGF. pAkt(308T) and pAkt(473S) were detected in WT and Gab1-deficient MEFs treated with EGF (100 ng/ml), TGF-α (100 ng/ml), PDGF-BB (25 ng/ml), insulin (1 μg/ml), or IGF-1 (10 ng/ml). (B) Gαi1 and Gαi3 are required for the phosphorylation of Gab1 in response to EGF. pGab1(307Y) and pGab1(627Y) in WT and DKO MEFs treated with EGF (100 ng/ml) were detected by Western blotting analysis. (C) Loss of Gαi1 and Gαi3 largely impairs phosphorylation of Akt and Gab1 in response to EGF and TGF-α, but not insulin. WT and DKO MEFs were treated with EGF (100 ng/ml), insulin (1 μg/ml), or TGF-α (100 ng/ml) for 5 min. pAkt(308T), pAkt(473S), pGab1(627Y), Gab1, PI3Kp85, and ERK1–2 were detected by Western blotting analysis.

Fig. 5.

EGF induces the association of Gab1 with Gαi1 and Gαi3, and the EGF-induced interaction of Gab1 with PI3K p85 depends on Gαi1 and Gαi3. (A) EGF induces the association of Gαi3 with Gab1. WT and DKO MEFs were treated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times and were then lysed. The precleared cell lysates (0.6 mg) were incubated with anti-EGFR or anti-Gαi3 antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with protein A/G beads for another 2 hours at 4°C. Beads were washed, boiled, resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, and proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane followed by Western blotting analysis with anti-EGFR, anti-Gαi3, and anti-Gab1, respectively. (B and C) EGF induces the association of Gab1 with Gαi1 and Gαi3. WT and DKO MEFs were treated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times. The precleared 600-μg aliquots of cell lysates were incubated with anti-Gab1 (B), or with anti-Gab1 and anti-Gαi1 (C), respectively, followed by Western blotting analysis with anti-Gab1, anti-pGab1(627Y), anti-Gαi1, and anti-Gαi3, respectively. (D) HEK 293 cells were treated with EGF for 5 min and then lysed. The precleared, 700-μg cell lysates were incubated with anti-EGFR, anti-Gab1, or anti-Gαi3 and 20 μl of protein A/G beads at 4°C overnight. Beads were washed four times with lysis buffer, boiled, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto a PVDF membrane, followed by Western blotting analysis to detect EGFR, Gαi3, and Gab1. (E) The same cell lysates used for Fig. 4C were precleared and incubated overnight with anti-p85 and 20 μl of protein A/G beads at 4°C. Beads were washed four times with lysis buffer, boiled, loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a PVDF membrane followed by Western blotting analysis to detect Gab1, pGab1(627Y), and PI3K p85. All experiments were repeated at least two or three times and similar results were obtained in each case.

Gαi proteins are important for EGF-dependent cell growth, migration, proliferation, survival, and the accumulation of cyclin D

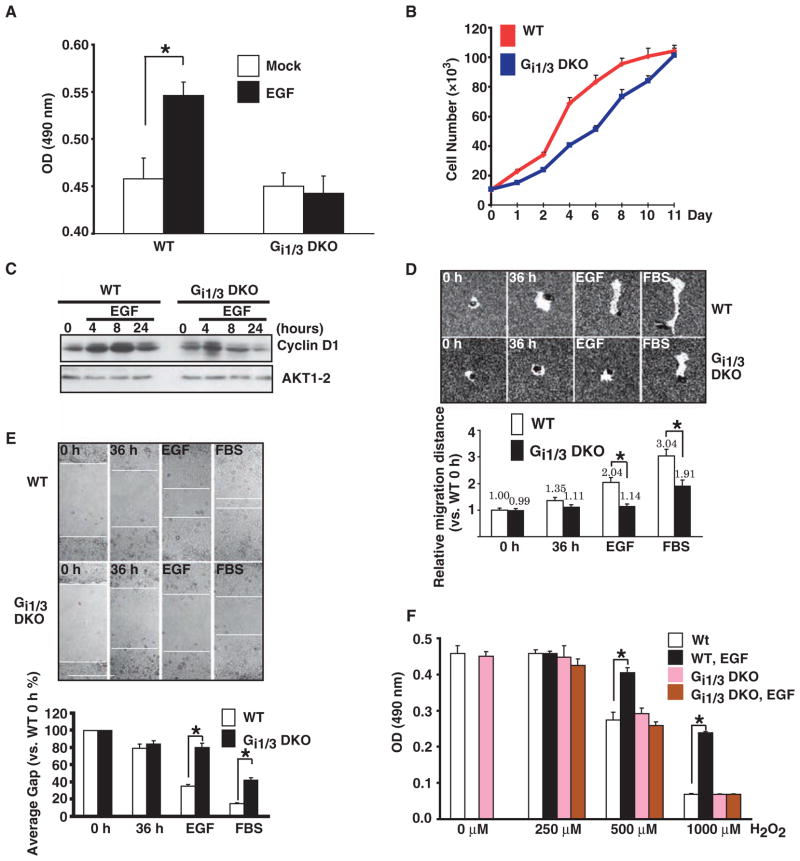

Lastly, we explored the biological role of Gαi proteins in the EGF pathway at the cellular level. We found that EGF-induced cell proliferation was greatly diminished in DKO cells compared to that in WT cells (Fig. 6A), and in medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), DKO cells grew more slowly than did WT cells (Fig. 6B). Therefore, we determined whether Gαi proteins were required for EGF-induced accumulation of cyclin D1, a protein that is expressed in the G1 phase of cell cycle, functions as a regulatory subunit for its enzymes CDK4/6, and is important for cell cycle progression, cell proliferation, and cell growth (28–30). Loss of Gαi1 and Gαi3 impaired the production of cyclin D1 by EGF (Fig. 6C). Activation of the EGFR promotes cell migration leading to tumor invasion (31). We found that EGF-induced cell migration was negligible in DKO cells and that FBS-induced cell migration in the deficient cells was also reduced (Fig. 6, D and E). Finally, we examined whether Gαi proteins were involved in the cell survival pathway, because previous studies have shown that EGF protects cells from apoptosis induced by H2O2 (32). We observed that whereas EGF protected WT cells from death induced by H2O2, it failed to do so in DKO cells (Fig. 6F). Taken together, our results show that Gαi proteins are critical for EGF-induced cell growth, accumulation of cyclin D1, cell migration, and cell survival.

Fig. 6.

Roles for Gαi1 and Gαi3 proteins in EGF-mediated cell proliferation, growth, migration, survival, and the production of cyclin D1. (A) Gαi1 and Gαi3 are important for EGF-induced cell proliferation. WT and DKO MEFs were treated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours. Cell proliferation was determined by the MTT assay. (B) Gαi1 and Gαi3 are involved in FBS-induced cell growth. FBS-induced cell growth in both WT and DKO cells was determined by counting cell numbers under a microscope. (C) WT and DKO MEFs were treated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for 4, 8, or 24 hours. The abundance of cyclin D1 was determined by Western blotting analysis with an antibody to cyclin D1. (D and E) Gαi1 and Gαi3 are required for EGF-induced cell migration. WT and DKO MEFs were incubated with serum-free medium in the presence or absence of EGF (100 ng/ml) or 10% FBS for 36 hours. In vitro cell migration was determined by the phagokinetic track motility assay (D) or the scratch assay (E). The image represents a minimum of 10 random fields for each group. Magnification: 200× for phagokinetic track motility assay and 100× for scratch assay. (F) Gαi proteins are required for EGF-induced cell survival. WT and DKO MEFs were treated with different doses of H2O2 in the presence or absence of EGF (100 ng/ml). After 24 hours, cell viability was measured by the MTT assay. Mitomycin C (10 μg/ml) was always present in the media to prevent cell proliferation from occurring. The data represent the mean ± SE of at least triplicate experiments. *P < 0.05 versus WT groups.

DISCUSSION

EGFR is the prototype of a family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) that activate the PI3K-Akt-mTORC1 pathway and participate in the control of differentiation, proliferation, growth, migration, and cell survival, as well as in disease states such as tumor development. A favored model of activation of the PI3K-Akt-mTORC1 pathway involves EGF-stimulated recruitment of Grb2 and Gab1 (both of which are required for multiple processes in embryonic development and malignant transformation) from the cytosol to the activated EGFR where Gab1 is phosphorylated and then interacts with the p85 subunit of PI3K, which leads to the activation of PI3K (33–35). In this model, Grb2 acts downstream of EGFR, but upstream of Gab1, and is required for the association between Gab1 and EGFR. Although aspects of this model are evolving, it was recently shown that Gab1-deficient cells show a severe defect in the activation of Akt (24, 36), whereas Grb2-deficient MEFs do not exhibit such a defect at a high dose of EGF (37), indicating that Grb2 is not critical for EGF-mediated activation of Akt. This finding is further supported by an in vivo analysis that showed that Gab1ΔPI3K/ΔPI3K knockin mice (in which the p85-binding sites of Gab1 were mutated), but not Gab1ΔGrb2/ΔGrb2 knockin mice (in which the Grb2-binding sites of Gab1 were mutated), mimicked a phenotype that has been identified in mice with impaired EGFR signaling (38).

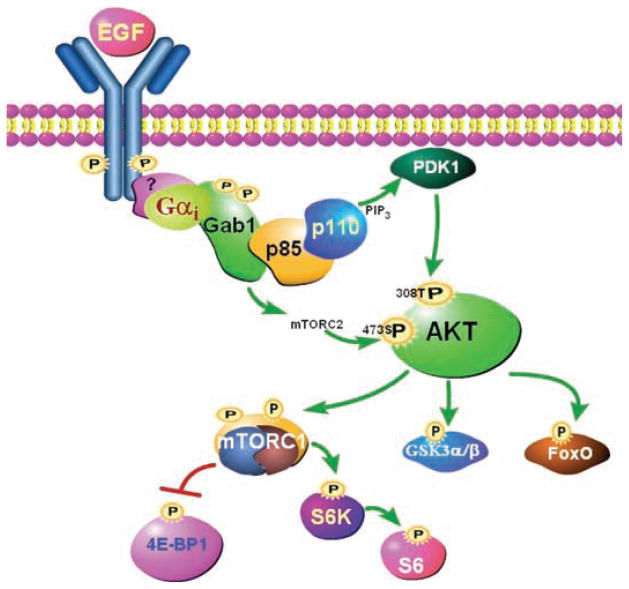

The present study provides a hitherto unresolved mechanism for the role of Gαi proteins in EGFR signaling. Specifically, it shows that upon stimulation with EGF or a related growth factor, Gαi proteins acted downstream of EGFR, but upstream of Gab1, to transduce EGFR signaling to Gab1 (Fig. 7). This resulted in the phosphorylation of Gab1 and its subsequent interaction with p85, which led to the activation of PI3K and downstream signaling through the Akt-mTORC1 pathway.

Fig. 7.

Model of Gαi-mediated activation of the PI3K-Akt-mTORC1 pathway in response to EGF. EGF induces formation of a complex between EGFR, Gαi, and Gab1. Recruitment of Gαi to the receptor may occur directly or through an as yet unidentified protein. Subsequently, Gαi interacts with Gab1, which promotes its phosphorylation by the EGFR or a non-RTK. Activated Gab1 interacts with the regulatory subunit of PI3K (p85), which leads to the activation of the catalytic subunits of PI3K (p110). Active PI3K phosphorylates PIP2 (phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate) to generate PIP3 (phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate), which in turn interacts with the pleckstrin homology domain of Akt and PDK1, and PDK1 phosphorylates Akt on Thr308. Activated Gab1 uses an unidentified mechanism to trigger the activation of mTORC2, which leads to the phosphorylation of Akt on Ser473. When Akt is activated, it phosphorylates FOXO, GSK-3α, and GSK-3β and triggers the activation of mTORC1, which results in phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and S6K, which in turn phosphorylates S6.

Requirement of Gαi proteins for EGF-mediated activation of Akt and mTORC1

The Gαi proteins were originally categorized by their ability to inhibit adenylyl cyclase. Epinephrine, acetylcholine, dopamine, and serotonin use Gαi proteins to stimulate physiological responses. Upon their ligation with GPCRs, Gαi proteins are activated and then release Gβγ subunits, which directly couple to PI3K, leading to the activation of PI3K and its downstream cascades. Signals transduced from Gαi proteins are inhibited by PTX, which ADP-ribosylates Gαi proteins at their C terminus to prevent their interaction with GPCRs. Thus, PTX has been widely used to determine whether Gαi proteins are involved in multiple cellular processes, including activation of the PI3K-Akt-mTORC1 pathway in response to hormones, neurotransmitters, and growth factors.

We have shown that Gαi proteins are required for the activation of Akt and mTORC1 by EGF and its related growth factors. These findings are unexpected because, based on observations that PTX fails to block the activation of Akt by EGF, it had been concluded that Gαi proteins were not involved in the activation of Akt (18–21). However, a flurry of recent studies suggest that although PTX induces ADP-ribosylation of Gαi proteins and uncouples them from GPCRs, it does not impede the activation of Gαi proteins by various accessory proteins, nor does it prevent the interaction of Gαi proteins with their initiator or effector proteins (39). It is most likely that the EGFR activates Gαi proteins by a mechanism different from that of GPCRs, resulting in a failure of PTX to prevent activation of Akt upon stimulation with EGF.

We have provided genetic evidence that loss of Gαi1 and Gαi3 proteins largely impairs the activation of Akt and mTORC1 in response to EGF. This finding was further confirmed by RNAi and dominant interference strategies. Furthermore, introduction of Gαi1 or Gαi3 into DKO MEFs restored the ability of EGF to activate Akt and mTORC1. In addition, we showed that the GTPase activity of Gαi proteins may play a role in EGF signaling, because expressing a constitutively active mutant of Gαi3 (which had reduced GTPase activity compared to that of WT Gαi3) triggered the activation of Akt and mTORC1 in DKO MEFs in the absence of EGF.

Unexpectedly, loss of Gαi2 did not result in a clear defect in EGF-mediated activation of Akt and mTORC1; however, we found that the abundance of Gαi1 and Gαi3 in Gαi2-deficient MEFs was higher than that in WT cells (fig. S1), indicating that any defect in the activation of Akt and mTORC1 as a result of the loss of Gαi2 was likely compensated for by the increased abundance of Gαi1 and Gαi3.

Gab1 is an intracellular target for Gαi proteins in EGFR signaling

In the traditional model, Gαi proteins only serve as signal transducers for GPCRs at the plasma membrane (12). However, it has long been appreciated that Gαi proteins also reside intracellularly (12, 40), indicating that Gαi proteins may have cytoplasmic functions. Indeed, in mammals, the Src family tyrosine kinase members c-Src and Hek, which form a major group of cellular signal transducers of GPCR, RTK, and non-RTK proteins, have been identified as targets of Gαi proteins (41). Gαi proteins not only associate with c-Src in vivo, they also bind to and directly trigger the activation of c-Src in vitro. In yeast, the involvement of intracellular Gα proteins in the activation of PI3K has been shown in response to pheromone (42), which activates a GPCR to cause Gpa1 (Gα in yeast) to translocate from the plasma membrane to the endosome, where it directly binds to its intracellular targets Vps34 and Vps15, which encode catalytic and regulatory subunits of PI3K, respectively.

Here, we have identified Gab1 as an intracellular target of Gαi proteins. Gαi proteins interacted with Gab1 in response to EGF and were required for the phosphorylation of Gab1 and its subsequent interaction with the p85 subunit of PI3K. Loss of Gαi proteins had no effect on the activation of EGFR, indicating that Gαi proteins act downstream of EGFR. Because studies have indicated that Grb2 is not critical for the activation of Akt by EGF, our results suggest that Gαi proteins act as linkers to bridge the gap between Gab1 and the EGFR in PI3K-Akt-mTORC1 signaling.

Differential regulation of EGFR signaling by Gαi proteins

In addition to the PI3K-Akt-mTORC1 pathway, EGFR also activates PLC-γ and STAT5 pathways. EGFR phosphorylates PLC-γ, and EGF-activated PLC-γ catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphoinositides and the production of IP3. However, although PTX inhibits the production of IP3 in rat hepatocytes and inner medullary collecting tubule cells in response to EGF (16, 43), it fails to inhibit the production of IP3 in Swiss 3T3 cells, WB cells (rat liver epithelial cells), and A431 cells (43), which suggests that inhibition of the production of IP3 by PTX occurs in a cell-specific manner. Furthermore, PTX has no effect on the phosphorylation of PLC-γ in Swiss 3T3 cells in response to EGF (43). Consistent with this observation, we found that DKO MEFs did not exhibit a defect in EGF-mediated phosphorylation of PLC-γ in response to EGF. EGFR phosphorylates STAT5 and triggers STAT5-dependent transcription and other cellular responses upon stimulation with EGF. Similar to our findings with PLC-γ, loss of Gαi1 and Gαi3 had no effect on EGF-mediated phosphorylation of STAT5. Taken together, our findings suggest that Gαi proteins differentially regulate EGFR signaling.

Biological roles of Gαi proteins in EGFR signaling

We have identified important biological roles for Gαi proteins as regulators of EGF-induced cell proliferation, growth, migration, and survival. We have shown that loss of Gαi1 and Gαi3 proteins impaired cell proliferation and survival in response to EGF. We demonstrated that deficiency in Gαi1 and Gαi3 decreased the abundance of cyclin D, a protein important for cell proliferation, and severely impaired the phosphorylation of Akt and the mTORC1 targets GSK-3, FoxO, 4E-BP1, and S6, factors critical for cell survival, in response to EGF.

We also observed that loss of Gαi1 and Gαi3 largely impaired EGF-induced cell migration and decreased cell migration in response to FBS. Because Akt is important for cell migration, this observation may be explained by a failure of EGF to trigger the activation of Akt in DKO MEFs (44–47). It has been reported that EGF-induced, but not FBS-induced, migration is substantially impaired in Gα13-deficient MEFs (48). Gα13 directly interacts with the small GTPase Rac to regulate lamellipodia and ruffle formation (45). Active Rac triggers p21-activated kinase (PAK), which stimulates dorsal ruffles and inhibits stress fibers. More importantly, Akt can activate PAK, which in turn activates Rac (45). Therefore, it is possible that Gαi proteins can regulate the activation of both Rac and PAK in response to EGF. It will be of interest to investigate whether Gαi proteins cross talk with Gα13 and co-regulate cell migration mediated by activation of EGFR.

In summary, the results presented here provide genetic evidence that Gαi proteins are critical for the activation of the PI3K-Akt-mTORC1 pathway by EGF. Given that EGF and EGFR are expressed in most human carcinomas and that activation of Akt and mTOR is critical for tumor progression in such processes as proliferation, survival, and metastasis, our findings suggest that Gαi proteins may serve as a potentially new target for anticancer therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies

Antibodies against EGFR (sc-03), pEGFR1173Y (sc-12351), Gαi1 (sc-391), Gαi3 (sc-262), Gab1 (sc-9049), cyclin D1 (sc-20044), and AKT1–2 (sc-8312), goat antibody against rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (sc-2030), and goat antibody against mouse IgG-HRP (sc-2031) were purchased from Santa Cruz Bio-technology (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) against β-actin was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). mAb against EE was purchased from Covance (Emeryville, CA). All other antibodies against phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, and phosphotyrosine were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

Cell lines and cell culture

WT, Gαi1-deficient, Gαi2-deficient, Gαi3-deficient, and Gαi1, Gαi3 doubly deficient (DKO) MEFs were derived from WT, Gαi1-deficient, Gαi2-deficient, Gαi3-deficient, and Gαi1, Gαi3 doubly deficient mouse E14.5 (embryonic day 14.5) embryos. The MEFs (5 × 105 to 10 × 105) were then immortalized by transfection with the total SV40 genome (plasmid pSV40WT) and subcultured several times with DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS (49). WT and Gab1-deficient MEFs were used as previously described (50). HEK 293 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. Cells were maintained in DMEM high-glucose medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Atlanta Biological Inc, Atlanta, GA), 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 1× nonessential amino acids, and penicillin and streptomycin (each 100 IU/ml; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in a CO2 incubator at 37°C.

Western blotting analysis

Aliquots of 30 μg of protein from each sample (treated as indicated in the legends) were separated by 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). After blocking with 10% instant nonfat dry milk for 1 hour, membranes were incubated with specific antibodies overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with secondary antibodies (HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG at the appropriate dilutions) for 45 min to 1 hour at room temperature. Antibody binding was detected with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Immunoprecipitation

Cells treated with the appropriate stimuli were lysed with lysis buffer, 200 mM NaCl (pH 7.4), 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 0.3 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Aliquots of 600 μg of proteins from each sample were precleared by incubation with 20 μl of protein A/G Sepharose (beads) (Amersham, IL) for 1 hour at 4°C. Precleared samples were incubated with specific antibodies in lysis buffer overnight at 4°C. To this was added 20 μl of protein A/G beads and the samples were incubated for 2 hours at 4°C. The beads were washed five times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and once with lysis buffer, boiled, separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto a PVDF membrane followed by Western blotting analysis as described above.

Plasmids and transfections

Expression vectors encoding WT Gαi1, WT Gαi3, EE-tagged Gαi1, EE-tagged Gαi3, dominant-negative mutants of Gαi1(G202T) and Gαi3(G202T), and constitutively active Gαi3(Q204L) were obtained from the Missouri S&T cDNA Resource Center (www.cdna.org). EE-tagged Gαi1(G202T) and EE-tagged Gαi3(G202T) were generated with a mutagenesis kit (Invitrogen) and confirmed by sequencing. MEFs were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. After 24 hours, cells were starved for 6 hours followed by a 30-min incubation with prewarmed PBS before the indicated treatments.

RNAi and transfection

Gαi1-and Gαi3-specific RNAi duplexes were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. MEFs were cultured in 10% FBS in the absence of antibiotics for 4 days. Cells (5 × 105 to 10 × 105) were seeded into a six-well plate 1 day before transfection and cultured to 60 to 70% confluence the following day. Lipofectamin LTX (6.25 μl) and PLUS Reagent (2.5 μl, Invitrogen) were diluted in 90 μl of small interfering RNA (siRNA) Dilution Buffer for 5 min at room temperature. Twenty microliters of Gαi1-specific (sc-41751) and Gαi3-specific (sc-29325) RNAi duplexes (10 μM, diluted in siRNA Dilution Buffer from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were mixed with Lipofectamin LTX and then with PLUS reagent and incubated for 30 min at room temperature to enable complex formation. The complex was added to the well containing 2 ml of medium with a final siRNA concentration of 100 nM. After 24 hours, the abundances of Gαi1 and Gαi3 proteins were monitored, and transfected cells were starved and treated with EGF (100 ng/ml) and insulin (1 μg/ml) for the indicated times.

In vitro wound healing (“scratch”) assay

These assays were carried out as previously described (31). Twelve-well plates were precoated with polylysine (30 μg/ml) followed by blocking with bovine serum albumin. A sufficient number of serum-starved MEFs were plated so that they became confluent in the wells 1 to 2 hours after attachment. The same area of each well was then displaced by scratching a line through the layer with a needle to generate a gap between the cells. Floating cells were removed by washing with PBS. Cells were incubated with serum-free medium in the presence or absence of the indicated reagents for an additional 36 hours. Mitomycin C (10 μg/ml) was always included in the media to prevent cells from proliferating. Ten representative images of the scratched areas under each condition were photographed with an Olympus IX71 microscope equipped with a Q Imaging Retiga 1300 system. To estimate the relative migration of the cells, the unclosed, cell-free areas from 10 prints under each condition were detected. The migration rate of cells was calculated by measuring the distance or gap between the cells. The mean (average) gap from 10 individual wound areas was used to quantify the data. The gap at 0 hours for WT cells was considered to be 100%.

Phagokinetic track motility assay

This assay was performed as previously described (31). Briefly, 12-well plates were coated with fibronectin (20 μg/ml; Sigma) and 2.4 ml of microsphere suspension (86 μl of stock microbead solution in 30 ml of PBS; Sigma) was added to each well. The plates were then centrifuged at 1200 rpm (Allegra 6KR, Beckman Coulter, CA) at 4°C for 20 min and carefully transferred to a CO2 incubator at 37°C for at least 1 hour. About 1.8 ml of supernatant was removed from each well and, finally, 1500 freshly trypsinized cells in 2 ml of DMEM medium were seeded in each well. Cells were cultured for 36 hours in the presence or absence of the appropriate reagents and then photographed with an Olympus IX71 microscope equipped with a Q Imaging Retiga 1300 system. At least 50 cells in 10 random views from each condition were quantified for the distances that they had migrated.

Cell viability assay (MTT dye assay)

This assay was performed as described previously (51). Cell viability was measured by the 3-[4,5-dimethylthylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma) method. Briefly, cells were collected and seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well. After starvation for 24 hours, cells were exposed to the indicated reagents followed by incubation with 20 μl of MTT (5 mg/ml) for an additional 4 hours. The medium was aspirated from each well and 150 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma) was added to dissolve formazan crystals, and the absorbance of each well was obtained with the MRX Revelation plate reader at a test wavelength of 490 nm with a reference wavelength of 630 nm. For cell proliferation assays, mitomycin C (10 μg/ml) was not added to the medium; for cell rescue assays, however, mitomycin C (10 μg/ml) was included in the media to prevent cells from proliferating.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. The increased abundance of Gαi1 and Gαi3 proteins in Gαi2-deficient MEFs.

Footnotes

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Rozengurt E. Mitogenic signaling pathways induced by G protein-coupled receptors. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:589–602. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steelman LS, Abrams SL, Whelan J, Bertrand FE, Ludwig DE, Bäsecke J, Libra M, Stivala F, Milella M, Tafuri A, Lunghi P, Bonati A, Martelli AM, McCubrey JA. Contributions of the Raf/MEK/ERK, PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR and Jak/STAT pathways to leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:686–707. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabatini DM. mTOR and cancer: Insights into a complex relationship. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:729–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greer EL, Brunet A. FOXO transcription factors in ageing and cancer. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2008;192:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam EW, Francis RE, Petkovic M. FOXO transcription factors: Key regulators of cell fate. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:722–726. doi: 10.1042/BST0340722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang J, Slingerland JM. Multiple roles of the PI3K/PKB (Akt) pathway in cell cycle progression. Cell Cycle. 2003;2:339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers MG, Jr, Backer JM, Sun XJ, Shoelson S, Hu P, Schlessinger J, Yoakim M, Schaffhausen B, White MF. IRS-1 activates phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase by associating with src homology 2 domains of p85. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10350–10354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skolnik EY, Margolis B, Mohammadi M, Lowenstein E, Fischer R, Drepps A, Ullrich A, Schlessinger J. Cloning of PI3 kinase-associated p85 utilizing a novel method for expression/cloning of target proteins for receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 1991;65:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90410-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu P, Margolis B, Skolnik EY, Lammers R, Ullrich A, Schlessinger J. Interaction of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-associated p85 with epidermal growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:981–990. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holgado-Madruga M, Emlet DR, Moscatello DK, Godwin AK, Wong AJ. A Grb2-associated docking protein in EGF-and insulin-receptor signalling. Nature. 1996;379:560–564. doi: 10.1038/379560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downes GB, Gautam N. The G protein subunit gene families. Genomics. 1999;62:544–552. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marrari Y, Crouthamel M, Irannejad R, Wedegaertner PB. Assembly and trafficking of heterotrimeric G proteins. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7665–7677. doi: 10.1021/bi700338m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gohla A, Klement K, Piekorz RP, Pexa K, vom Dahl S, Spicher K, Dreval V, Häussinger D, Birnbaumer L, Nürnberg B. An obligatory requirement for the heterotrimeric G protein Gi3 in the antiautophagic action of insulin in the liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3003–3008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611434104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamiya Y, Kawaguchi M, Ito J, Fujii T, Sakuma N, Fujinami T. Effect of cholera toxin and pertussis toxin on the growth of A431 cells: Kinetics of cyclic AMP and inositol trisphosphate in toxin-treated cells. Horm Metab Res. 1995;27:137–140. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang LJ, Baffy G, Rhee SG, Manning D, Hansen CA, Williamson JR. Pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi protein involvement in epidermal growth factor-induced activation of phospholipase C-γ in rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:22451–22458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teitelbaum I, Strasheim A, Berl T. Epidermal growth factor-stimulated phosphoinositide hydrolysis in cultured rat inner medullary collecting tubule cells. Regulation by G protein, calcium, and protein kinase C. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1044–1050. doi: 10.1172/JCI114534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang MN, Garrison JC. The epidermal growth factor receptor is coupled to a pertussis toxin-sensitive guanine nucleotide regulatory protein in rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:13342–13349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dajani OF, Meisdalen K, Guren TK, Aasrum M, Tveteraas IH, Lilleby P, Thoresen GH, Sandnes D, Christoffersen T. Prostaglandin E2 upregulates EGF-stimulated signaling in mitogenic pathways involving Akt and ERK in hepatocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2008;214:371–380. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu EH, Wong YH. Pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi/o proteins are involved in nerve growth factor-induced pro-survival Akt signaling cascade in PC12 cells. Cell Signal. 2005;17:881–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chien MW, Chien CS, Hsiao LD, Lin CH, Yang CM. OxLDL induces mitogen-activated protein kinase activation mediated via PI3-kinase/Akt in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1667–1675. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300006-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kue PF, Daaka Y. Essential role for G proteins in prostate cancer cell growth and signaling. J Urol. 2000;164:2162–2167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hubbard KB, Hepler JR. Cell signalling diversity of the Gqα family of heterotrimeric G proteins. Cell Signal. 2006;18:135–150. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barren B, Artemyev NO. Mechanisms of dominant negative G-protein α subunits. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:3505–3514. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bard-Chapeau EA, Hevener AL, Long S, Zhang EE, Olefsky JM, Feng GS. Deletion of Gab1 in the liver leads to enhanced glucose tolerance and improved hepatic insulin action. Nat Med. 2005;11:567–571. doi: 10.1038/nm1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakaoka Y, Nishida K, Narimatsu M, Kamiya A, Minami T, Sawa H, Okawa K, Fujio Y, Koyama T, Maeda M, Sone M, Yamasaki S, Arai Y, Koh GY, Kodama T, Hirota H, Otsu K, Hirano T, Mochizuki N. Gab family proteins are essential for postnatal maintenance of cardiac function via neuregulin-1/ErbB signaling. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1771–1781. doi: 10.1172/JCI30651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yart A, Laffargue M, Mayeux P, Chretien S, Peres C, Tonks N, Roche S, Payrastre B, Chap H, Raynal P. A critical role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase upstream of Gab1 and SHP2 in the activation of ras and mitogen-activated protein kinases by epidermal growth factor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8856–8864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006966200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattoon DR, Lamothe B, Lax I, Schlessinger J. The docking protein Gab1 is the primary mediator of EGF-stimulated activation of the PI-3K/Akt cell survival pathway. BMC Biol. 2004;2:24. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perry JE, Grossmann ME, Tindall DJ. Epidermal growth factor induces cyclin D1 in a human prostate cancer cell line. Prostate. 1998;35:117–124. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980501)35:2<117::aid-pros5>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poch B, Gansauge F, Schwarz A, Seufferlein T, Schnelldorfer T, Ramadani M, Beger HG, Gansauge S. Epidermal growth factor induces cyclin D1 in human pancreatic carcinoma: Evidence for a cyclin D1-dependent cell cycle progression. Pancreas. 2001;23:280–287. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shibuya H, Yoneyama M, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K, Taniguchi T. IL-2 and EGF receptors stimulate the hematopoietic cell cycle via different signaling pathways: Demonstration of a novel role for c-myc. Cell. 1992;70:57–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90533-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao C, Sun Y, Healey S, Bi Z, Hu G, Wan S, Kouttab N, Chu W, Wan Y. EGFR-mediated expression of aquaporin-3 is involved in human skin fibroblast migration. Biochem J. 2006;400:225–234. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yasuda Y, Yoshinaga N, Murayama T, Nomura Y. Inhibition of hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis but not arachidonic acid release in GH3 cell by EGF. Brain Res. 1999;850:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higashiyama S, Iwabuki H, Morimoto C, Hieda M, Inoue H, Matsushita N. Membrane-anchored growth factors, the epidermal growth factor family: Beyond receptor ligands. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:214–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ono M, Kuwano M. Molecular mechanisms of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) activation and response to gefitinib and other EGFR-targeting drugs. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:7242–7251. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishida K, Hirano T. The role of Gab family scaffolding adapter proteins in the signal transduction of cytokine and growth factor receptors. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:1029–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bard-Chapeau EA, Yuan J, Droin N, Long S, Zhang EE, Nguyen TV, Feng GS. Concerted functions of Gab1 and Shp2 in liver regeneration and hepatoprotection. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4664–4674. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02253-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cully M, Elia A, Ong SH, Stambolic V, Pawson T, Tsao MS, Mak TW. grb2 heterozygosity rescues embryonic lethality but not tumorigenesis in pten+/− mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15358–15363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406613101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaeper U, Vogel R, Chmielowiec J, Huelsken J, Rosario M, Birchmeier W. Distinct requirements for Gab1 in Met and EGF receptor signaling in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15376–15381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702555104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sato M, Blumer JB, Simon V, Lanier SM. Accessory proteins for G proteins: Partners in signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:151–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koelle MR. Heterotrimeric G protein signaling: Getting inside the cell. Cell. 2006;126:25–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma YC, Huang J, Ali S, Lowry W, Huang XY. Src tyrosine kinase is a novel direct effector of G proteins. Cell. 2000;102:635–646. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slessareva JE, Routt SM, Temple B, Bankaitis VA, Dohlman HG. Activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase Vps34 by a G protein α subunit at the endosome. Cell. 2006;126:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hepler JR, Jeffs RA, Huckle WR, Outlaw HE, Rhee SG, Earp HS, Harden TK. Evidence that the epidermal growth factor receptor and non-tyrosine kinase hormone receptors stimulate phosphoinositide hydrolysis by independent pathways. Biochem J. 1990;270:337–344. doi: 10.1042/bj2700337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ju X, Katiyar S, Wang C, Liu M, Jiao X, Li S, Zhou J, Turner J, Lisanti MP, Russell RG, Mueller SC, Ojeifo J, Chen WS, Hay N, Pestell RG. Akt1 governs breast cancer progression in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7438–7443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605874104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou GL, Tucker DF, Bae SS, Bhatheja K, Birnbaum MJ, Field J. Opposing roles for Akt1 and Akt2 in Rac/Pak signaling and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36443–36453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carmona G, Gottig S, Orlandi A, Scheele J, Bauerle T, Jugold M, Kiessling F, Henschler R, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S, Chavakis E. Role of the small GTPase Rap1 for integrin activity regulation in endothelial cells and angiogenesis. Blood. 2009;113:488–497. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang ZZ, Tschopp O, Hemmings-Mieszczak M, Feng J, Brodbeck D, Perentes E, Hemmings BA. Protein kinase Bα/Akt1 regulates placental development and fetal growth. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32124–32131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shan D, Chen L, Wang D, Tan YC, Gu JL, Huang XY. The G protein Gα13 is required for growth factor-induced cell migration. Dev Cell. 2006;10:707–718. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu JY, Abate M, Rice PW, Cole CN. The ability of simian virus 40 large T antigen to immortalize primary mouse embryo fibroblasts cosegregates with its ability to bind to p53. J Virol. 1991;65:6872–6880. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6872-6880.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun Y, Yuan J, Liu H, Shi Z, Baker K, Vuori K, Wu J, Feng GS. Role of Gab1 in UV-induced c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation and cell apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1531–1539. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1531-1539.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cao C, Lu S, Kivlin R, Wallin B, Card E, Bagdasarian A, Tamakloe T, Chu WM, Guan KL, Wan Y. AMP-activated protein kinase contributes to UV-and H2O2-induced apoptosis in human skin keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28897–28908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804144200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 52.We thank J. Wands for discussion. This work was supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Defense (PR054819) and NIH (AI054128) to W.M.C., NIH (DK069771) to M.J., NIH (P20 RR016457) to Y.W., and in part from the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH, to L.B. C.C. is partially supported by the Pathobiology Graduate Program at Brown University. W.M.C. is a scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. The increased abundance of Gαi1 and Gαi3 proteins in Gαi2-deficient MEFs.