Abstract

Background:

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is more prevalent among Iranian adolescences. This study aimed to find the relationship between obesity and MetS among different education grades of Iranian adolescence.

Materials and Methods:

Overall, 1039 junior high school and 953 high school students were selected using multistage random sampling. Fasting blood sugar, total cholesterol, triglyceride (TG), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) were measured. Trained individuals measured waist circumference and blood pressure. MetS was defined according to the De Ferranti definition.

Results:

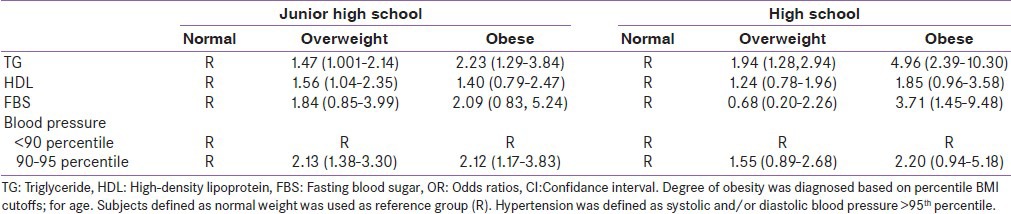

The prevalence of overweight and obesity was 12.6% and 6.2% in junior and 11.5% and 4.3% in high school students, respectively. Obese subjects in both grades have higher waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and triglyceride than comparable groups. Multiple logistic regression models showed that overweight and obesity were strongly associated with MetS components analyzed. Compared to normal-weight children, overweight and obese in junior high school students were 1.47 and 2.23 times more likely to be having high TG, respectively, whereas overweight and obese in high school-students were also more likely to have elevated TG [ORs 1.94 (1.28-2.94), 4.96 (2.39-10.3) respectively].

Conclusion:

Obese children have the highest prevalence of MetS. Prevalence of MetS-related components has reached high level among Iranian adolescences that were overweight or obese.

Keywords: Adolescence, metabolic syndrome, obesity

INTRODUCTION

Childhood obesity has become a public health concern in all over the world.[1] Obesity is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and CVD risks as well as morbidity and mortality among obese children.[2] Long-term studies showed that obesity led to clustering of cardiovascular risk factors or metabolic syndrome (MetS).[3] The MetS includes the clustering of abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and elevated blood pressure and is associated with other co-morbidities including the prothrombotic state, proinflammatory state, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and reproductive disorders.[4]

In addition, epidemiological studies among Iranian children demonstrated that obesity, as one of the main components of MetS, has increased dramatically in recent years.[5] Iran, as other developing countries, has undergone economic and lifestyle transitions during the past decades. Unhealthy diet, physically inactivity, and the influence of epigenetic factors contribute to increasing obesity among children and adolescence.[6] Results of Isfahan Healthy Heart Program (IHHP) showed that the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Iranian children increased over a 6-year period (2001-2007).[7,8] Beside the increasing rate of obesity among Iranian adolescence, the prevalence of MetS consequently increased among our target population. However, data about association of MetS and obesity in adolescents based on the grade are limited. So, the present study aimed to find the relationship between obesity and MetS among different grades of Iranian adolescence by using comprehensive data sources, a large sample covering a wide age range, and objective measures assessed by trained professionals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present sub-study is a part of Heart Health Promotion from Childhood (HHPC) Project, which was performed as one of interventional projects of a comprehensive community-based program IHHP with school-based approach to improve lifestyle behavior and cardio-metabolic risk factors among students in junior high school and high schools.[8] Briefly, HHPC public education was done through mass media, pamphlets, booklets, face-to-face meetings, proposing role models among students, arranging different competitions with the subject of healthy heart, serving healthy snacks, establishing healthy heart buffets, reinforcing healthy eating habits in schools, and gathering parents at least yearly to train healthy nutrition.[8]

Participants

In this sub-study, 1039 students in junior high schools and 953 students in high school from the final phase of IHHP were selected. Complete information regarding sampling process has been presented elsewhere.[8] The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Center (a WHO collaborating center), and signed written informed consent was obtained from all subjects’ parents.

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric parameters including weight, height, and waist circumference were measured using standard tools. Height and weight were measured with subjects wearing light clothing and without shoes. Height was recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm. Weight was also measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a balance-beam scale. The waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm at the midpoint between the bottom of the rib cage and the top of the iliac crest at the end of exhalation. The participants’ blood pressure was measured twice after a 5 min rest using the right hand, and the mean was recorded as their blood pressure.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Overweight and obesity were defined based on 85th ≤BMI <95th and ≥95th percentiles of BMI, respectively.[9]

Laboratory measurements

Blood lipids were measured enzymatically with the commercially available reagents (Triglycerides/GPO, cat. no. 816370, Boehringer Mannheim). HDL-cholesterol was measured in the clear supernatant after precipitating the other lipoproteins with heparin and MnCl (1.3 g/L and 0.046 mol/L, resp.) and removing excess Mn by precipitation with NaHCO. Fasting glucose was measured using the Glucose Standard Assay (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis).[10]

MetS definition

MetS in studied youths was defined using the de Ferranti definition[R}, as three or more of the following variables and cutoff points: (1) WC ≥ 75th percentile, (2) serum triglyceride > 100 mg, (3) HDL < 40 mg/dl, (4) blood pressure ≥ 90th percentile, and (5) FBS > 100 mg/dl.

Statistical analysis

Data entry was carried out using EPI 2000. Data were analyzed by SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA; Version 15). Quantitative variables are expressed as Mean ± SD, and qualitative variables as frequencies (percent). Qualitative variables were compared between Junior high school and high school using the Chi-square test and fisher exact test when more than 20% of cells with expected count of less than 5 were observed. Quantitative variables were compared by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal Wallis test when the assumptions such as normality and homogeneity of variance don’t hold. Multiple logistic regressions was performed between component of metabolic such as TG, HDL, FBS (normal/elevated) as dependent variable and BMI status as independent variables adjusted by sex and age based on grade. Multiple multinomial logistic regression was performed between blood pressure status (normal/pre Hypertension/hypertension) as dependent variable and BMI status as independent variables adjusted by sex and age based on grade. P values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

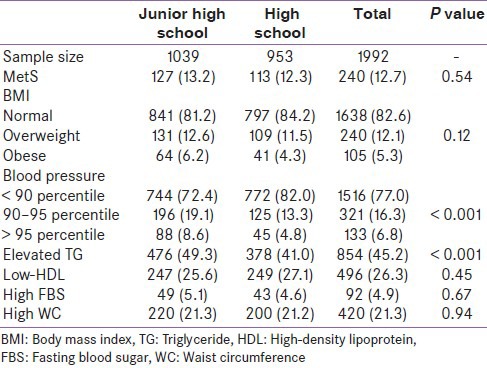

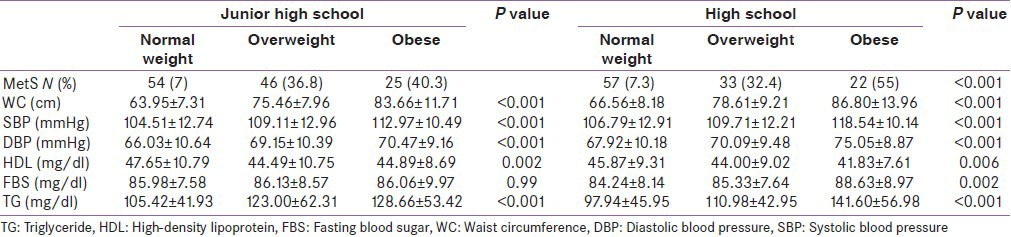

Distribution of different components of metabolic syndrome in both junior and high schools is displayed in Table 1. The prevalence of MetS was 13.2% in juniors and 12.3% in high school students. The prevalence of overweight and obesity was 12.6% and 6.2% in junior and 11.5% and 4.3% in high school students, respectively. Elevated blood pressure (more than 95 percentile) was more observed in junior high school students than in high school students. According to the De Ferranti definition, increased TG is more prevalent among junior high school students. Table 2 shows metabolic disorders between both grades students by weight status. Obese subjects in both grades have higher waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and triglyceride than comparable groups. However, contrarily, significant differences were observed between HDL in normal weigh adolescence in both grades compared to obese groups. Associations between MetS-related components and obesity in the sample of 1992 students showed in Table 3. Multiple Logistic regression models showed that overweight and obesity were strongly associated with MetS components analyzed. Compared to normal-weight children, overweight and obese in junior high school students were 1.47 and 2.23 times more likely to be having high TG, respectively, whereas overweight and obese in high school-students were also more likely to have elevated TG [ORs 1.94 (1.28-2.94), 4.96 (2.39-10.3), respectively.

Table 1.

Prevalence of obesity and metabolic disorders among Iranian children in junior high school and high school

Table 2.

Metabolic disorders among 1992 student in junior and high school by weight status

Table 3.

Logistic regression model; odds ratios and 95% CIs of MetS components according to the degree of obesity among junior and high school students

DISCUSSION

Several national studies have been done to find the impact of obesity on the prevalence of MetS, but to our knowledge, this is the first study, which demonstrates the relationship between degree of obesity with components of MetS in the junior and high school Iranian students. Our results demonstrated that 12.1% of these were overweight and 5.3% were obese in Iranian students without considering the grade. The prevalence of obesity, overweight, and MetS are not significantly different among junior and high school students. In addition, we showed high prevalence of MetS and it's components among overweight and obese Iranian adolescence. The prevalence of MetS varied considerably by grade: It was 7.3%, 36.8%, and 40.3% in the normal BMI, overweight, and obese junior high school group and 7.3, 32.4, and 55% in the high school student. Whereas, Mehrkesh et al. previously reported that the prevalence of components of MetS is relatively high among 450 Iranian high school students, even among those not overweight.[8,11]

The prevalence of MetS among obese children in our study population was much higher than that in Japanese (17.7%),[12] Chinese[13] and was approximately the same as reported in the US (27.8%).[14,15] A systematic review on prevalence of MetS in different countries showed that the highest prevalence of childhood overweight was found in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, whereas India and Sri Lanka had the lowest prevalence. The few studies conducted in developing countries showed a considerably high prevalence of the MetS among youth.[16]

Interestingly, our study found that there were significant differences in prevalence of MetS components between junior and high school students. The prevalence of elevated blood pressure in rural areas was higher than that in urban areas, while prevalence of elevated high blood pressure, high TG, high FBS, and lower HDL was more prevalent in junior high school students than that in high school students. These results suggested that differences in the prevalence of MetS and its components might be due to hormonal changes in pubescence, body composition, lifestyle, and nutritional habits between junior and high school students. It is suggested that Iranian junior high school students are more interested to having sedentary than elder students. Several studies in the developed countries have indicated that there is a positive association between obesity in children and adolescence and the amounts of time spent watching television. Increased television viewing time, playing video games, and using the Internet have been often cited as a contributing factor to the increased prevalence of sedentary behavior during leisure time.[17] A meta-analysis by Musaiger evaluated the rate and possible causes of obesity and overweight among children in Eastern Mediterranean Region. He reported that the rate of obesity in preschool children in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq, and Iran has significant relationship with the hours of TV watching per day.[18]

In addition, eating unhealthy snacks and foods such as potato chips, crisps and other savoury snacks. and so on during TV watching is another contributing factor for obesity. This may lead to overeating because the type and the amounts consumed food may be less well self-monitored.[19] Another study revealed that fast food consumption is associated with the higher prevalence of obesity in girl adolescents.[20]

In summary, obesity is associated with components of MetS in our youth population. Younger adolescences are at higher risk for components of MetS and further related disease. So, it is necessary to focus on changing their bad habits such as high-energy food and snacks consumption as well as encourage them to be more physically active to prevent co-morbid disease in adulthood.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This program was supported by a Grant (no. 31309304) from the Iranian Budget and Planning Organization, as well as the Deputy for Health of the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education and Iranian Heart Foundation. It was conducted by Isfahan Cardiovascular Institute with the collaboration of Isfahan Provincial Health Center, both affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.[21]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No

REFERENCES

- 1.Danese A, Tan M. Childhood maltreatment and obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:544–54. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer FX, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: An update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2006;113:898–918. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarrafzadegan N, Gharipour M, Sadeghi M, Nouri F, Asgary S, Zarfeshani S. Differences in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in boys and girls based on various definitions. ARYA Atheroscler. 2013;9:70–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornier MA, Dabelea D, Hernandez TL, Lindstrom RC, Steig AJ, Stob NR, et al. The metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:777–822. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barzin M, Hosseinpanah F, Saber H, Sarbakhsh P, Nakhoda K, Azizi F. Gender differences time trends for metabolic syndrome and its components among Tehranian children and adolescents. Cholesterol 2012. 2012:804643. doi: 10.1155/2012/804643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber DR, Leonard MB, Zemel BS. Body composition analysis in the pediatric population. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2012;10:130–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarrafzadegan N, Kelishadi R, Sadri G, Malekafzali H, Pourmoghaddas M, Heidari K, et al. Outcomes of a comprehensive healthy lifestyle program on cardiometabolic risk factors in a developing country: The Isfahan Healthy Heart Program. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16:4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelishadi R, Mohammadifard N, Sarrazadegan N, Nouri F, Pashmi R, Bahonar A, et al. The effects of a comprehensive community trial on cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescents: Isfahan Healthy Heart Program. ARYA Atheroscler. 2012;7:184–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Guo S, Wei R, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: Improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109:45–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarrafzadegan N, Rabiei K, Kabir A, Sadeghi M, Khosravi A, Asgari S, et al. Gender differences in risk factors and outcomes after cardiac rehabilitation. Acta Cardiol. 2008;63:763–70. doi: 10.2143/AC.63.6.2033395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehrkash M, Kelishadi R, Mohammadian S, Mousavinasab F, Qorbani M, Hashemi ME, et al. Obesity and metabolic syndrome among a representative sample of Iranian adolescents. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2012;43:756–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshinaga M, Tanaka S, Shimago A, Sameshima K, Nishi J, Nomura Y, et al. Metabolic syndrome in overweight and obese Japanese children. Obes Res. 2005;13:1135–40. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen F, Wang Y, Shan X, Cheng H, Hou D, Zhao X, et al. Association between childhood obesity and metabolic syndrome: Evidence from a large sample of Chinese children and adolescents. PloS One. 2012;7:e47380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook S, Weitzman M, Auinger P, Nguyen M, Dietz WH. Prevalence of a metabolic syndrome phenotype in adolescents: Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition ExaminationSurvey, 1988-1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:821–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruz ML, Weigensberg MJ, Huang TT, Ball G, Shaibi GQ, Goran MI. The metabolic syndrome in overweight Hispanic youth and the role of insulin sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:108–13. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelishadi R. Childhood overweight, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:62–76. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.French SA, Story M, Jeffery RW. Environmental influences on eating and physical activity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:309–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Musaiger AO. Overweight and obesity in eastern mediterranean region: Prevalence and possible causes. J Obes 2011. 2011:407237. doi: 10.1155/2011/407237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yahia N, Achkar A, Abdallah A, Rizk S. Eating habits and obesity among Lebanese university students. Nutr J. 2008;7:32. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rouhani MH, Mirseifinezhad M, Omrani N, Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L. Fast food consumption, quality of diet, and obesity among Isfahanian adolescent girls. J Obes 2012. 2012:597924. doi: 10.1155/2012/597924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musaiger AO. Overweight and obesity in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: Can we control it? East Mediterr Health J. 2004;10:789–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]