Abstract

Mannosidases catalyze the hydrolysis of a diverse range of polysaccharides and glycoconjugates, and the various sequence-based mannosidase families have evolved ingenious strategies to overcome the stereoelectronic challenges of mannoside chemistry. Using a combination of computational chemistry, inhibitor design and synthesis, and X-ray crystallography of inhibitor/enzyme complexes, it is demonstrated that mannoimidazole-type inhibitors are energetically poised to report faithfully on mannosidase transition-state conformation, and provide direct evidence for the conformational itinerary used by diverse mannosidases, including β-mannanases from families GH26 and GH113. Isofagomine-type inhibitors are poor mimics of transition-state conformation, owing to the high energy barriers that must be crossed to attain mechanistically relevant conformations, however, these sugar-shaped heterocycles allow the acquisition of ternary complexes that span the active site, thus providing valuable insight into active-site residues involved in substrate recognition.

Keywords: computational chemistry, conformation analysis, enzymes, inhibitors, transition states

Mannosidases are glycoside hydrolases (GHs) which catalyze the cleavage of glycosidic linkages in mannose-containing glycoconjugates and polysaccharides. α-Mannosidases are important in N-glycan biosynthesis and protein quality control and their inhibition may allow intervention in diseases which utilize N-linked glycans for protein folding.1 β-Mannosidases are important in the degradation of plant-derived mannans (β-mannan, glucomannan, galactomannan) and are of industrial significance in the detergent, food, biofuels, and oil and gas industries.2 Biochemical studies of mannosidases from different sequence-based families have highlighted that a variety of conformational itineraries,3 and a range of mechanistic strategies are employed for glycosidic bond cleavage.4 The study of the diverse pathways employed by mannosidases can inform synthetic efforts designed to overcome the often recalcitrant chemistry of mannose.5

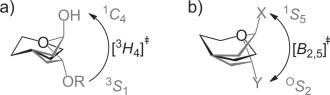

A rationalization of the rate enhancement achieved by an enzyme pivots upon an understanding of its transition state. This understanding in turn can instruct the development of transition-state analogue inhibitors, which have exciting potential as drug candidates.6 Mannosidase inhibitors are designed to mimic the charge, planarity, and conformation of the oxocarbenium ion-like “exploded” transition state(s) of mannosidase-catalyzed hydrolysis. Upon protonation, isofagomine-type inhibitors, exemplified by isofagomine (IFG) 1 (Figure 1), resemble a glycosyl cation with charge localized at C1, but are poor mimics of transition-state conformation. Alternatively, mannoimidazole (MIm)-type inhibitors, for example, 2, are qualitatively good models of a mannopyranosyl oxocarbenium ion-like transition state, with sp2 hybridization of equivalent atoms and the potential for anti protonation7 of the imidazole functionality. Structural studies aimed at identifying the conformation of the transition state and flanking ground states on the reaction coordinate, utilizing 2, and related inhibitors as transition-state and ground-state mimics, identified a 1S5↔B2,5≠↔OS2 conformational itinerary for mannosidases of families GH2,8 38,9 and 92,10 and a 3S1→3H4≠→1C4 itinerary for the α-mannosidases of GH47.11 However, it is now apparent that complexes with 2 can report on both the transition-state conformation and conformational itinerary.11 Quantitative kinetic and thermodynamic analyses using Bartlett plots and isothermal titration calorimetry suggest 2 is a true transition-state mimic.8, 11 However, these energetic analyses do not report which features of the ligand imbue transition-state mimicry.

Figure 1.

Structures of isofagomine (1), mannoimidazole (2), ManIFG (3), and ManMIm (4).

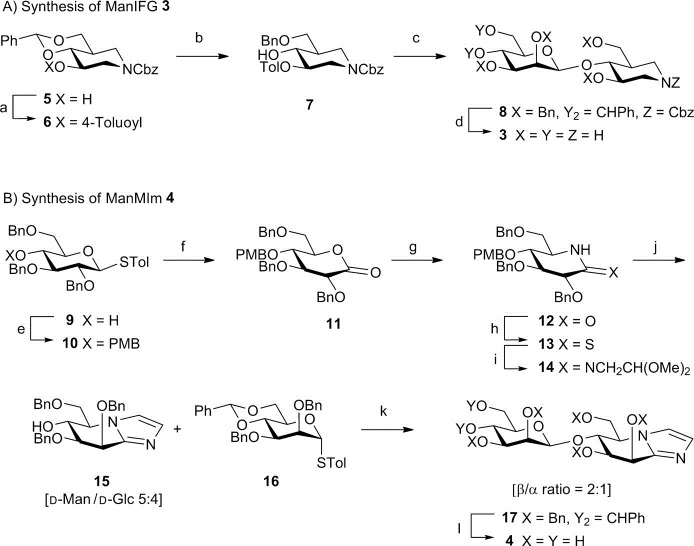

Herein we present syntheses of new β-mannanase-targeted inhibitors, ManIFG (3) and ManMIm (4; Figure 1). Together with 1,4-β-mannobiose, 3 afforded a unique ternary complex with the β-mannanase of family GH113, thus defining the active-site cleft. Compound 4 was used to obtain new transition-state mimicking complexes with β-mannanases of families GH26 and GH113, thus allowing the assignment of conformational itineraries for these enzymes. The conformations of the inhibitors in these novel structures and previously reported mannosidase complexes of these classes of inhibitors were correlated with quantum mechanical (QM) calculations of the free-energy landscape (FEL) for 1 and 2 “off-enzyme”, to identify which conformations better resemble the mannosidase transition state.

A 1S5→B2,5≠→OS2 glycosylation conformational itinerary has been proposed for GH26 mannanases on the basis of the transition-state flanking Michaelis complex in a 1S5 conformation,12 and the glycosyl–enzyme intermediate in an OS2 conformation,13 combined with the principle of least nuclear motion. Only the uncomplexed form of a sole GH113 β-mannanase has been solved and no proposals have been advanced for transition-state conformation for this family.14 To gain direct evidence for transition-state conformation for these two families, the isofagomine and mannoimidazole inhibitor “warheads” were used to develop new inhibitors targeted at the representative β-mannanases from families GH26 and GH113, β-1,4-mannobiohydrolase from Cellvibrio japonicus CjMan26C, and endo-β-1,4-mannanase from Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius AaManA, respectively. The synthesis of 3 and 4 is outlined in Scheme 1 (see the Supporting Information).

Scheme 1.

a) 4-Toluoyl chloride, DMAP, pyridine, CH2Cl2, 88 %; b) TFA, Et3SiH, CH2Cl2, 93 %; c) 16, Tf2O, 2,4,6-tri-tert-butylpyrimidine, 60 %; d) 1. NaOMe, 2. H2, Pd(OH)2, AcOH/H2O/THF, 80 %; e) PMBCl, NaH, DMF,78 %, f) 1. H2O, NIS, acetone, 0 °C, 78 %, 2. DMSO, Ac2O; g) 1. NH3, Et2O, reflux; 2. DMSO, Ac2O, 3. HCO2H, NaBH3(CN), MeCN, 74 % over 4 steps; h) Lawesson’s reagent, pyridine, toluene, 99 %; i) H2NCH2CH(OMe)2; j) TsOH, toluene, H2O, 50 °C, 65 % over 2 steps; k) TfOH, NIS, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 39 %; l) H2 (6 bar), Pd(OH)2, AcOH/EtOAc/MeOH/H2O, 58 %. DMAP=4-(N,N-dimethylamino)pyridine, DMF=N,N-dimethylformamide, DMSO=dimethylsulfoxide, NIS=N-iodosuccinimide, PMB=para-methoxybenzyl, TFA=trifluoroacetic acid, Tf=trifluoromethanesulfonyl, THF=tetrahydrofuran, Ts=4-toluenesulfonyl.

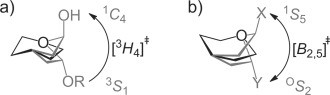

Compounds 3 and 4 are potent inhibitors of CjMan26C with KI values of (263±15) and (194±8) nm, respectively, thus partly reflecting an unusually high-affinity −2 subsite.15 Soaking 3 and 4 into crystals of CjMan26C yielded complexes that diffracted to a resolution of 1.2 and 1.1 Å, respectively, with inhibitors occupying the −2 and −1 subsites (Figure 2 a; see Figures S1a, S2; Table S1 in the Supporting Information). The MIm moiety in the −1 subsite of the CjMan26C/4 complex adopts a B2,5 conformation, which is consistent with the proposed 1S5→B2,5≠→OS2 glycosylation conformational itinerary for GH26.

Figure 2.

a) Binary complex of ManMIm (4) bound to CjMan26C. b) Binary complex of 4 bound to AaManA. c) Ternary complex showing ligand binding within the active site of GH113 β-mannanase AaManA. ManIFG (3) occupies the −2 and −1 subsites, whilst β-1,4-mannobiose is observed within +1 and +2 subsites. Depicted electron density maps are REFMAC maximum-likelihood/σA-weighted 2Fo−Fc syntheses contoured at 0.41, 0.38, and 0.41 electrons per Å3, respectively.

Compounds 3 and 4 are weaker inhibitors of AaManA with KI values of (0.26±0.04) and 1.3 mm, respectively, which are consistent with this enzyme exhibiting a preference for binding elongated substrates in the − and + subsites distal to −2 and −1. Soaking 4 into crystals of AaManA yielded a complex that diffracted to a resolution of 1.5 Å with the ligand occupying the −2 and −1 subsites. The MIm moiety in the −1 subsite adopts a B2,5 conformation (Figure 2 b; see Figure S2 and Table S1). By invoking the principle of least nuclear motion, this complex is diagnostic of a 1S5→B2,5≠→OS2 conformational itinerary for family GH113. Soaking 3, either alone, or with 1,4-β-mannobiose, into crystals of AaManA yielded binary and ternary complexes which diffracted to a resolution of 1.6 Å (Figure 2 c; see Figures S1b and S2, and Table S1). The ternary complex with 3 bound in the −2 and −1 subsites, and 1,4-β-mannobiose bound in the +1 and +2 subsites, provides the first complete mapping of substrate-binding amino acid residues across the −2 to +2 subsites for a GH113 enzyme (Figure 2 c; see Figure S2 and Table S1).

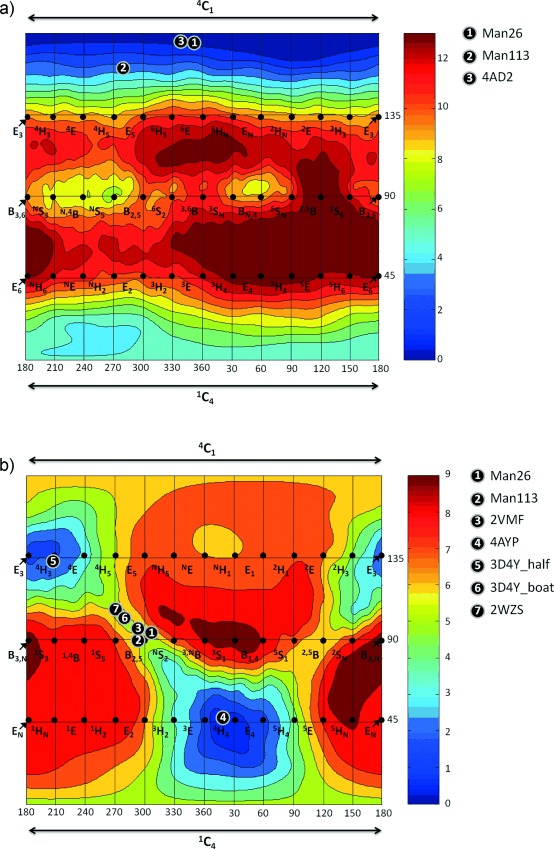

To understand the intrinsic conformational preferences of 116 and 2, we employed QM calculations to construct a conformational FEL. The FEL of 1 reveals that the 4C1 conformation is preferred, with the mechanistically relevant 1C4 and B2,5 conformations located 5 and 8 kcal mol−1 higher in energy, respectively, and with a greater than 10 kcal mol−1 barrier for their interconversion (Figure 3 a). These data suggest that IFG is a poor transition-state mimic and consistent with this the 4C1 conformation is the only conformation observed for isofagomine-type inhibitors when bound to mannosidases (Figure 3 a). Other conformations have been observed for isofagomine-type inhibitors bound to glucosidases/cellulases (see Figure S3). In striking contrast, the FEL of 2 is consistent with good transition-state shape mimicry, with all mechanistically relevant half-chair (4H3 and 3H4), envelope (3E, E3, 4E, and E4), and boat (2, 5B or B2,5) conformations energetically accessible (Figure 3 b). A global minimum was found near the 4H3 conformation with a second local minimum approximately 1 kcal mol−1 higher in energy near the 3H4 conformation, both of which have been observed on-enzyme. The other conformation of 2, which has been observed on-enzyme, the B2,5, was near a saddle point between these local minima and was 5 kcal mol−1 higher in energy than the 3H4 conformation. The FEL for 2 reveals that the conformations relevant to the reaction coordinate are all energetically accessible, and moreover, that a B2,5 conformation is less stable than the E and H conformations. This in turn suggests that the observation of a B2,5 conformation for 2 on-enzyme is of special mechanistic significance, with the enzyme inducing the inhibitor to adopt a conformation to match the transition state.

Figure 3.

Conformational free-energy landscapes (FELs, Mercator projection) of isolated isofagomine (1; a) and protonated mannoimidazole (2; b), contoured at 1 kcal mol−1. FELs have been annotated with the conformations of isofagomine-type (for a) and mannoimidazole-type (for b) inhibitors which have been observed on-enzyme. a) 1: 3 bound to GH26 CjMan26C (this work); 2: 3 bound to GH113 AaManA (this work); 3: α-Glc-1,3-isofagomine bound to BxGH99 (PDB code 4AD2).17 b) 1: 4 bound to GH26 CjMan26C (this work); 2: 4 bound to GH113 AaManA (this work); 3: 1 bound to GH2 BtMan2A (PDB code 2VMF);18 4: 1 bound to GH47 CkMan47 (PDB code 4AYP);11 5: 1 bound to GH38 DmGManII (PDB code 3D4Y) in half-chair conformer;19 6: 1 bound to GH38 DmGManII (PDB code 3D4Y) in boat conformer (this work); 7: 1 bound to GH92 BtMan3990 (PDB code 2WZS).20

Collectively, the conformations of mannoimidazole-type inhibitors bound to mannosidases of diverse families highlights that mannosidases readily modulate the ligand conformational landscape. This conclusion is consistent with FEL analysis of α-D-mannopyranose bound to a GH47 α-mannosidase, and established that the enzyme reshapes the conformational landscape, thus defining the energetically accessible space.11 For enzymes from GH2,21 GH26,13 and GH47,11 conformations of ground states adjacent to the transition state (Michaelis, glycosyl-enzyme or product complexes) provide strong evidence that mannoimidazole-type inhibitors authentically report transition-state conformation on-enzyme. However, the 4H3 conformation reported for the complex of 2 and Drosophila melanogaster Golgi GH38 α-mannosidase II (DmGManII) is inconsistent with this interpretation.19 On the basis of a glycosyl–enzyme intermediate in a 1S5 conformation,9 and theory,22 a B2,5 transition-state conformation is predicted. Inspection of the density map reveals significant residual electron density in the complex,23 and re-refinement of these data with 2 in two conformations shows that 30–40 % of the ligand binds as a second transition-state mimicking conformer in an approximate B2,5 conformation (see Figure S4).

We next analyzed the atomic charges and ring planarity of the four mechanistically relevant conformations (4H3, 3H4, B2,5, 2,5B) of 2. We combined the values of the charge development at the C1 atom (qC1), the C5-O5-C1-C2 dihedral angle, and the free energy for a large set of representative structures into a unique index (named “TS index”, TSi, see the Supporting Information), in the spirit of the previously reported preactivation index for isolated aldohexoses.11, 24 Table S2 and Figures S5 and S6 show that there is no single conformation with the optimum values for every parameter (score=100). The TSi values (see Figure S7) reveal that even though the H conformations are favored over B conformations when solely considering their energy (Figure 2 b), they possess different TSi values. Most importantly, the two transition-state mimicking conformations that have been observed on-enzyme, 3H4 and B2,5, have the highest TSi values. Therefore, as observed for glycans bound to GHs,3, 25 the inhibitor conformation on-enzyme is not only dictated by the relative energy of the molecule itself but also by structural and electronic properties.

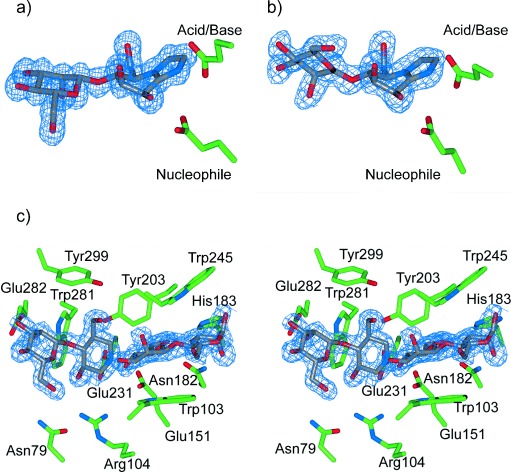

In conclusion, the calculated FEL of 2 shows a preference for 3H4 and 4H3 half-chair conformations, and that a B2,5 conformation represents a higher energy, but easily accessible saddle point between these two minima and thus that mannoimidazole-type inhibitors, in contrast to the isofagomine-type, are energetically poised to faithfully report transition-state conformation. X-ray structures of 4 with two β-mannanases from GH26 and GH113 provide the first direct evidence for a B2,5 conformation of the transition state of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction of these families. Previous work with GH47 α-mannosidases found that 2 bound in a 3H4 conformation, implicating a 3S1→3H4≠→1C4 itinerary for this family (Figure 4 a). The B2,5 conformation has now been observed for mannoimidazole-type inhibitors in complex with α- and β-mannosidases from five GH families: GH2, 26, 38, 92, and 113 (Figure 4 b). A 1S5↔B2,5≠↔OS2 conformational itinerary is common to all of these families, a result that unifies mannosidases which operate through both retaining and inverting, and metal-dependent and metal-independent mechanisms.

Figure 4.

Conformational itineraries employed by mannosidases. a) 3S1→3H4≠→1C4 itinerary of GH47 inverting α-mannosidase. b) 1S5↔B2,5≠↔OS2 itinerary employed by retaining GH2 and GH38 β-mannosidases, inverting GH92 α-mannosidases and retaining GH26 and GH113 β-mannanases (X, Y = leaving group, enzyme carboxylate or OH).

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201308334.

References

- [1].Lederkremer GZ. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009;19:515. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Moreira LRS, Filho EXF. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;79:165. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Davies GJ, Planas A, Rovira C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45:308. doi: 10.1021/ar2001765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fushinobu S, Alves VD, Coutinho PM. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013;23:652. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Crich D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010;43:1144. doi: 10.1021/ar100035r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Schramm VL. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:71. doi: 10.1021/cb300631k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Heightman TD, Vasella AT. Angew. Chem. 111:794. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990315)38:6<750::AID-ANIE750>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38 [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tailford LE, Offen WA, Smith N, Dumon C, Morland C, Gratien J, Heck MP, Stick RV, Bleriot Y, Vasella A, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:306. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Numao S, Kuntz DA, Withers SG, Rose DR. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:48074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309249200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhu Y, Suits MDL, Thompson AJ, Chavan S, Dinev Z, Dumon C, Smith N, Moreman K, Xiang Y, Siriwardena A, Williams SJ, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:125. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Thompson AJ, Dabin J, Iglesias-Fernandez J, Ardevol A, Dinev Z, Williams SJ, Bande O, Siriwardena A, Moreland C, Hu TC, Smith DK, Gilbert HJ, Rovira C, Davies GJ. Angew. Chem. 124:11159. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51 [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cartmell A, Topakas E, Ducros VMA, Suits MDL, Davies GJ, Gilbert HJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:34403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804053200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ducros VMA, Zechel DL, Murshudov GN, Gilbert HJ, Szabo L, Stoll S, Withers SG, Davies GJ. Angew. Chem. 114:2948. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020802)41:15<2824::AID-ANIE2824>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41 [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhang Y, Ju J, Peng H, Gao F, Zhou C, Zeng Y, Xue Y, Li Y, Henrissat B, Gao GF, Ma Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:31551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tailford LE, Ducros VM, Flint JE, Roberts SM, Morland C, Zechel DL, Smith N, Bjornvad ME, Borchert TV, Wilson KS, Davies GJ, Gilbert HJ. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7009. doi: 10.1021/bi900515d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].The FEL of protonated isofagomine is dominated by an intramolecular hydrogen bond which is not relevant to the enzyme-bound species and so the neutral species was studied

- [17].Thompson AJ, Williams RJ, Hakki Z, Alonzi DS, Wennekes T, Gloster TM, Songsrirote K, Thomas-Oates JE, Wrodnigg TM, Spreitz J, Stutz AE, Butters TD, Williams SJ, Davies GJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111482109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].See Ref. [8]

- [19].Kuntz DA, Tarling CA, Withers SG, Rose DR. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10058. doi: 10.1021/bi8010785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].See Ref. [10]

- [21].Offen WA, Zechel DL, Withers SG, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ. Chem. Commun. 2009:2484. doi: 10.1039/b902240f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Petersen L, Ardevol A, Rovira C, Reilly PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8291. doi: 10.1021/ja909249u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].See Ref. [19]

- [24].Biarnés X, Ardèvol A, Planas A, Rovira C, Laio A, Parrinello M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10686. doi: 10.1021/ja068411o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ardèvol A, Biarnés X, Planas A, Rovira C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:16058. doi: 10.1021/ja105520h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.