Summary

Background

The activation of platelet CLEC‐2 by podoplanin on lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) has a critical role in prevention of mixing of lymphatic and blood vasculatures during embryonic development. Paradoxically, LECs release cAMP and cGMP‐elevating agents, prostacyclin (PGI2) and nitric oxide (NO), respectively, which are powerful inhibitors of platelet activation. This raises the question of how podoplanin is able to activate CLEC‐2 in the presence of the inhibitory cyclic nucleotides.

Objectives

We investigated the influence of cyclic nucleotides on CLEC‐2 signaling in platelets.

Methods

We used rhodocytin, CLEC‐2 monoclonal antibody, LECs and recombinant podoplanin as CLEC‐2 agonists on mouse platelets. The effects of the cyclic nucleotide‐elevating agents PGI2, forskolin and the NO‐donor GSNO were assessed with light transmission aggregometry, flow cytometry, protein phosphorylation and fluorescent imaging of platelets on LECs.

Results

We show that platelet aggregation induced by CLEC‐2 agonists is resistant to GSNO but inhibited by PGI2. The effect of PGI2 is mediated through decreased phosphorylation of CLEC‐2, Syk and PLCγ2. In contrast, adhesion and spreading of platelets on recombinant podoplanin, CLEC‐2 antibody and LECs is not affected by PGI2 and GSNO. Consistent with this, CLEC‐2 activation of Rac, which is required for platelet spreading, is not altered in the presence of PGI2.

Conclusions

The present results demonstrate that platelet adhesion and activation on CLEC‐2 ligands or LECs is maintained in the presence of PGI2 and NO.

Keywords: blood platelets, C‐type lectin, cyclic nucleotides, lymphangiogenesis, platelet activation

The C‐type lectin receptor CLEC‐2 has a single YxxL (hemITAM) in its cytoplasmic tail, which is phosphorylated upon ligand engagement by the interplay of Src and Syk tyrosine kinases 1. In turn, Syk is recruited via its tandem SH2 domains to two phosphorylated CLEC‐2 tails, leading to initiation of a downstream signaling cascade involving LAT, SLP‐76, PI3 kinase and PLCγ2, which culminates in platelet activation 2.

The only established physiological ligand for CLEC‐2 is podoplanin, a sialomucin‐like glycoprotein expressed in a variety of cells, including lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs). Several groups have shown that deletion of the gene encoding CLEC‐2, Clec1b, results in perinatal lethality in association with defects in lymphatic development 3 and a failure to inflate the lungs at birth 5. PF4‐Cre Clec1bfl/fl transgenic mice, which are deficient of CLEC‐2 in the platelet/megakaryocyte lineage, also have blood‐filled lymphatics 5. The same phenotype is seen following deletion of the CLEC‐2 signaling proteins, Syk, SLP‐76 and PLCγ2 4, or its ligand, podoplanin 4. These observations indicate that the activation of CLEC‐2 on platelets by podoplanin is necessary for prevention of blood‐lymphatic mixing during embryonic development 5. Blood‐filled lymphatics are found in the intestines of radiation chimeric mice reconstituted with Clec1b−/− fetal liver cells, indicating that CLEC‐2 is also necessary to repair the integrity of the intestinal lymphatic system. The interaction between platelet CLEC‐2 and podoplanin expressed on reticular fibroblastic cells is important in high endothelial venules, where it maintains integrity during immune responses 8.

The cyclic nucleotide‐elevating agents, NO and PGI2, are released by endothelial cells in the vasculature 9. LECs generate prostanoids, including PGI2 10, as well as NO 12, and these have been shown to modulate the contractile activity of the collecting lymphatics 13. The observation that podoplanin and CLEC‐2 are critical for prevention of blood‐lymphatic mixing during development raises the question of how podoplanin is able to activate CLEC‐2 in the presence of PGI2 and NO, and therefore elevated cAMP and cGMP, given the powerful inhibitory action of the two cyclic nucleotides 9.

Herein, we show that platelet aggregation induced by rhodocytin, CLEC‐2 antibody or podoplanin is inhibited by PGI2 but not by NO‐donors, and that platelet spreading on CLEC‐2 agonists is relatively insensitive to cyclic nucleotide‐elevating agents. These observations have important implications for understanding the molecular basis of platelet regulation in the development of the lymphatic system in mice.

Experimental procedures

Materials

Rhodocytin was purified as previously described 16. The extracellular domain (ECD) of mouse podoplanin was amplified from cDNA generated from C57BL/6 kidney with the primers mPodoHindFor (GATCAAGCTTATGTGGACCGTGCCAGTGTTG) and mPodoFcRev (GATCGGATCCACTTACCTGTCAGGGTGACTACTGGCAAGCC). After digestion with HindIII and BamHI the PCR product was cloned into a human IgG‐Fc containing vector. Recombinant protein was expressed and purified as previously described 17. Thrombin, PGI2, forskolin, GSNO and formaldehyde were purchased from Sigma (Poole, UK). Chrono lume and ATP were obtained from Chrono Log Corporation (Manchester, UK). PRT060318 was from previously described sources 1. Fibrinogen was from Enzyme Research (Swansea, UK), and Hydromount from National Diagnostic (Atlanta, GA, USA). Alexa‐Fluor‐488‐labeled fibrinogen was from Molecular Probes (Paisley, UK). Primary human LECs of dermal origin (HLECs) were purchased from Promocell GmbH (Heidelberg, Germany), and μ‐slides and Ibidi mounting medium were from Ibidi GmbH (Martinsried, Germany). ECL reagents were from GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, UK). Lotrafiban was from GlaxoSmithKline (Philadelphia, PA, USA). Leakage resistant Fura‐2 AM was from Teflabs (Austin, Texas, USA). The Rac1 activity kit was from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). The antibodies used in this study are listed in Table S1.

Mouse platelet preparation

Wild‐type (C57Bl/6 background) mice were anesthetized and terminally CO2 asphyxiated prior to laparotomy. Blood was drawn into 10% ACD (85 mm sodium citrate, 111 mm glucose, 78 mm citric acid). Washed platelets were prepared and resuspended in Tyrode's buffer as previously described 18. Washed platelets were incubated at room temperature (RT) for at least 30 min prior to experimentation to allow the effects of PGI2 to decay.

HLECs culture

HLECs were cultured in adherence on 1% gelatin in endothelial cell growth medium according to the manufacturer's instructions. Prior to aggregation experiments, cells were non‐enzymatically detached, suspended in Tyrode's buffer and immediately used. For adhesion experiments cells were cultured in Ibidi μ‐slides to confluence for 24 h prior to use. Cells were used between passages 4 and 7.

Platelet aggregation and dense granule secretion

Aggregation was performed in a dual channel Born lumi‐aggregometer (Chronolog, Labmedics, Manchester, UK) at 37 °C with stirring at 1200 rpm. When stated, washed platelets (2 × 108 per mL) were incubated with apyrase 2 U mL−1 and indomethacin 10 μm for 15 min prior to agonist addition. PGI2 or GSNO was pre‐incubated with platelets for 3 min at 37 °C. ATP secretion was measured by luminometry at the same time using Chronolume 1 : 30 and calibrating with a known amount of ATP standard.

Platelet spreading

Glass coverslips were coated overnight at 4 °C with 10 μg mL−1 mouse podoplanin, CLEC‐2 mAb or 100 μg mL−1 fibrinogen and blocked with 5 mg mL−1 denatured BSA for 1 h at RT. Washed platelets (2 × 107 per mL) treated as indicated were allowed to spread on the coverslips for 45 min at 37 °C. Coverslips were washed, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and mounted in Hydromount. Imaging was performed using differential interference contrast (DIC) optics with a Zeiss 63× oil immersion 1.40 NA plan‐apochromat lens on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope (Cambridge, UK). Images were captured by a Hamamatsu Orca 285 cooled digital camera (Welwyn Garden City, UK). The surface area of spread platelets was quantified by manual outlining and adhesion was quantified by counting platelets/field in five fields per experiment. The number of pixels within each outline was determined using Image J software. For adhesion on HLECs, platelets (5 × 108 per mL), treated as stated, were allowed to spread in HLEC‐coated Ibidi μ‐slides for 1 h at 37 °C prior to fixation and immunostaining with PE‐conjugated anti‐human podoplanin antibody (NZ‐1.3), rat anti‐mouse CD41 antibody (MWReg30) and goat anti‐rat IgG‐Alexa 647, mouse anti‐CD62P antibody (Psel.KO.2.7) and goat anti‐mouse IgG‐Alexa 488. Slides were mounted in Ibidi mounting medium and imaged with a 63× oil immersion 1.40 NA objective in a Leica SP2 confocal microscope (Wetzlar, Germany). Image analysis was performed using Image J software after applying automatic thresholds to segment raw greyscale images into binary data.

Ca2+ imaging

Platelets (2 × 108 per mL) were labeled with 2 μm leakage resistant Fura‐2 AM for 1 h, spun and suspended at 2 × 107 per mL. Aliquots treated as stated were added to a monolayer of HLECs in MatTek glass bottom dishes and imaged with 100× magnification (Olympus IX71 microscope [Southend on Sea, UK] coupled with a Photometrics Evolve 512 EMCCD Camera [Tucson, AZ, USA]) for 20 min every 2.5 s. Excitation wavelengths were alternated between 340 and 380 nm and emission was captured at 510 nm. Emission ratios for 340/380 excitations were processed using Metafluor software (Universal Imaging Corp., Downingtown, PA, USA). Calibration of the fluorescent dye maximum and minimum for the optical set‐up was done in situ and [Ca2+]i was calculated according to Grynkiewicz 19.

Immunoprecipitation

Stimulations for the preparation of lysates were performed as reported 1. Washed platelets (4 × 108 per mL) were incubated with 10 μm lotrafiban for 15 min to prevent aggregation. When stated, apyrase 2 U mL−1, indomethacin 10 μm, PGI2 1–2 μm or GSNO 100 μm were incubated as described above. Stimulations were stopped after 3 min by adding 2× lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Immunoprecipitations were performed as reported. Modifications from standard protocols were made for mouse CLEC‐2 immunoprecipitations as previously described 1.

SDS‐PAGE and western blotting

SDS‐PAGE (10%) and western blot were performed as described 1. When necessary, antibodies were removed by incubation with stripping buffer (TBS‐T containing 2% SDS) supplemented with 1% β‐mercaptoethanol for 20 min at 80 °C followed by incubation with stripping buffer only. Densitometry of the bands was performed using Adobe Photoshop.

Data analysis

Data are shown from a single representative experiment or as arithmetic mean ± SEM from the stated number of experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out using one‐way or two‐way anova followed by the stated post‐test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Role of secondary mediators in CLEC‐2‐dependent mouse platelet activation

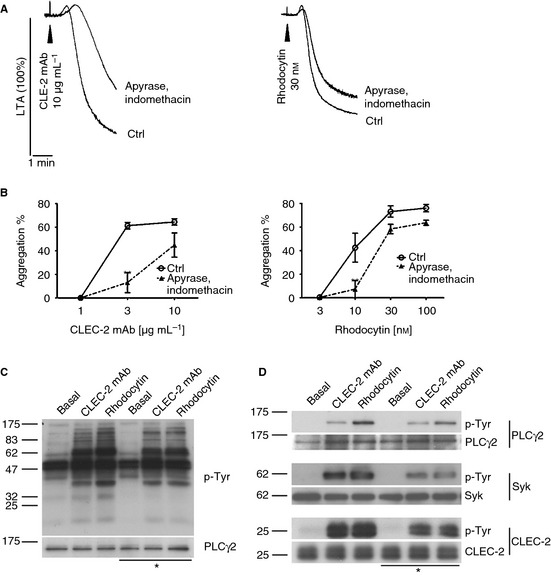

We have shown that CLEC‐2‐dependent activation of human platelets is regulated by release of the secondary mediators ADP and TXA2 20. To investigate the role of the two feedback agonists in mouse platelets, we used apyrase (2 U mL−1) and indomethacin (10 μm) to remove ADP and prevent TXA2 synthesis, respectively. On their own, apyrase and indomethacin had no significant effect on aggregation induced by rhodocytin, and caused a minor delay in response to 3 μg mL−1 CLEC‐2 mAb (Figure S1). These inhibitors, however, acted synergistically, causing a delay in aggregation in response to high concentrations of the CLEC‐2 mAb and rhodocytin, and a significant reduction at low and intermediate concentrations (Fig. 1A,B).

Figure 1.

CLEC‐2‐dependent activation of mouse platelets is partially mediated by ADP and TxA2‐. Washed platelets (2 × 108 per mL) were stimulated with 10 μg mL−1 CLEC‐2 mAb or 30 nm rhodocytin in the presence or absence of 2 U mL−1 apyrase and 10 μm indomethacin. Representative light transmission aggregometry (LTA) traces are shown (A). Aggregation after 5 min was plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 4–6). Statistical differences were evaluated by two‐way anova and Bonferroni post‐test (**P < 0.01) (B). Washed platelets (4 × 108 per mL) incubated with 10 μm lotrafiban were stimulated with 10 μg mL−1 CLEC‐2 mAb and 30 nm rhodocytin for 3 min in the presence (*) and absence of 2 U mL−1 apyrase and 10 μm indomethacin. Whole cell lysate was analyzed by SDS‐PAGE (C) and immunoprecipitation of PLCγ2, Syk and CLEC‐2 (D). Blots were probed with anti phospho‐tyrosine (p‐Tyr) antibody and reprobed for equal loading control (n ≥ 3) (C&D).

The role of secondary mediators in protein tyrosine phosphorylation was investigated. Lotrafiban was used to block aggregation and outside‐in signaling from integrin αIIbβ3. Global tyrosine phosphorylation of platelet proteins and phosphorylation of CLEC‐2, Syk and PLCγ2 were studied in response to 10 μg mL−1 CLEC‐2 mAb or 30 nM rhodocytin (Fig. 1C,D). For both agonists, phosphorylation was partially reduced in the presence of apyrase and indomethacin, as was particularly evident in the immunoprecipitation studies.

These results demonstrate that activation of mouse platelets by CLEC‐2 is potentiated by the secondary agonists, ADP and TxA2, although to a lesser extent than for human platelets 20.

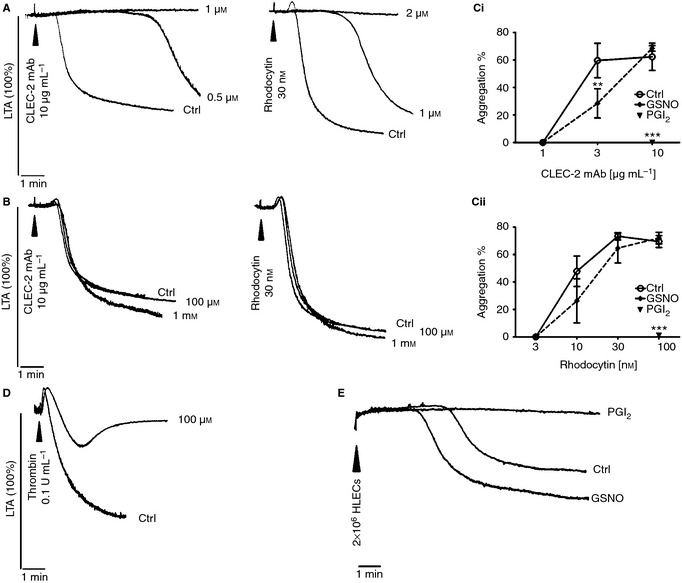

Effects of cyclic nucleotides on CLEC‐2‐dependent platelet aggregation

We used PGI2 and the NO‐donor GSNO to elevate intracellular cAMP and cGMP, respectively. Dose response curves for PGI2 and GSNO against concentrations of agonists that induce maximal aggregation (10 μg mL−1 CLEC‐2 mAb, 30 nM rhodocytin) are shown (Fig. 2A,B). CLEC‐2 mAb and rhodocytin‐induced platelet aggregation were completely abolished by 2 μm PGI2. In contrast, GSNO, at concentrations up to 1 mm, had no significant effect on aggregation in response to either agonist. ATP secretion from dense granules following 10 μg mL−1 CLEC‐2 mAb activation was completely abolished by 1 μm PGI2 and unchanged with 1 mm GSNO (3.5 ± 1.0 vs. 3.6 ± 0.1 nmol). Partial inhibition of aggregation was achieved against a threshold concentration of 3 μg mL−1 CLEC‐2 mAb (28.4 ± 10.6 vs. 59.6 ± 5.1%; P < 0.05) but not against rhodocytin (Fig. 2Ci–ii). A similar set of results was observed with a second NO‐donor (sodium nitroprusside, SNP, Figure S2A). In contrast, GSNO 100 μm causes a marked inhibition of thrombin‐induced aggregation (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

CLEC‐2‐dependent platelet aggregation is sensitive to cAMP‐mediated inhibition. Washed platelets (2 × 108 per mL) were stimulated with CLEC‐2 mAb or rhodocytin in the presence of increasing concentrations of (A) PGI2 or (B) GSNO. Representative aggregation traces are shown. Aggregation at 5 min in the presence or absence of either PGI2 (1 μm for CLEC‐2 mAb, 2 μm for rhodocytin) or GSNO (1 mm) was plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 3–5). Statistical differences were evaluated by two‐way anova and Bonferroni post‐test (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) (C). Washed platelets were stimulated with 0.1 U mL−1 thrombin in the presence of 100 μm GSNO; representative traces are shown (D). Washed platelets were stimulated with HLECs (2 × 106) in the presence or absence of 2 μm PGI2 or 1 mm GSNO (E) (n = 3).

As recombinant podoplanin and podoplanin‐expressing cells are able to induce platelet aggregation 21, HLECs (2 × 106) were used as a physiological CLEC‐2 agonist as they express podoplanin. HLECs induced platelet aggregation after a lag phase of several minutes, which was abolished by PGI2 (2 μm) but not affected by GSNO (1 mm) (Fig. 2E).

These results demonstrate that elevation of cAMP but not cGMP inhibits platelet aggregation to CLEC‐2 agonists.

A similar result was observed in human platelets activated by rhodocytin (Figure S3A), although a lower concentration of PGI2 was sufficient to inhibit aggregation as compared with mice. In contrast, neither GSNO nor SNP inhibited aggregation at concentrations of up to 300 μm (not shown).

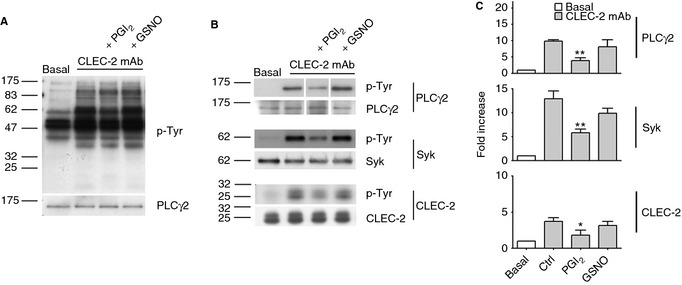

Effects of cyclic nucleotides on CLEC‐2‐dependent tyrosine phosphorylation

CLEC‐2 mAb stimulates marked tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins in the presence of inhibitors of secondary mediators, which was reduced in the presence of 1 μm PGI2 but unaltered in the presence of 100 μm GSNO (Fig. 3A) or SNP (Figure S2B). PGI2 inhibited phosphorylation of Syk and PLCγ2 by over 50% and of CLEC‐2 to a lesser degree (Fig. 3B,C). Similar results were observed for rhodocytin (Figure S4A,B). Interestingly, CLEC‐2 mAb and rhodocytin stimulated a similar level of phosphorylation of Syk and CLEC‐2, while rhodocytin induced stronger PLCγ2 phosphorylation, possibly as a result of sustained receptor clustering 23.

Figure 3.

CLEC‐2‐dependent tyrosine phosphorylation is partially reduced by cyclic nucleotide‐elevation. Washed platelets (4 × 108 per mL) incubated with PGI2 (1 μm) or GSNO (100 μm) in the presence of apyrase (2 U mL−1), indomethacin (10 μm) and lotrafiban (10 μm) were stimulated with 10 μg mL−1 CLEC‐2 mAb for 3 min and lysed. Aliquots were analyzed by SDS‐PAGE (A) and immunoprecipitation of PLCγ2, Syk and CLEC‐2 (B) (n = 3–4). Blots were probed with anti phospho‐tyrosine mAb (A & B) and reprobed for equal loading. Densitometry of PLCγ2, Syk and CLEC‐2 bands was expressed as fold increase over basal and plotted as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were evaluated by one‐way anova test and Bonferroni post‐test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01) (C).

In human platelets CLEC‐2‐dependent tyrosine phosphorylation strongly depends on secondary mediators 20. The residual signal in the presence of apyrase and indomethacin is very weak (Figure S3B) but was inhibited by PGI2 and not by cGMP‐elevating agents, in line with the observations in mouse platelets.

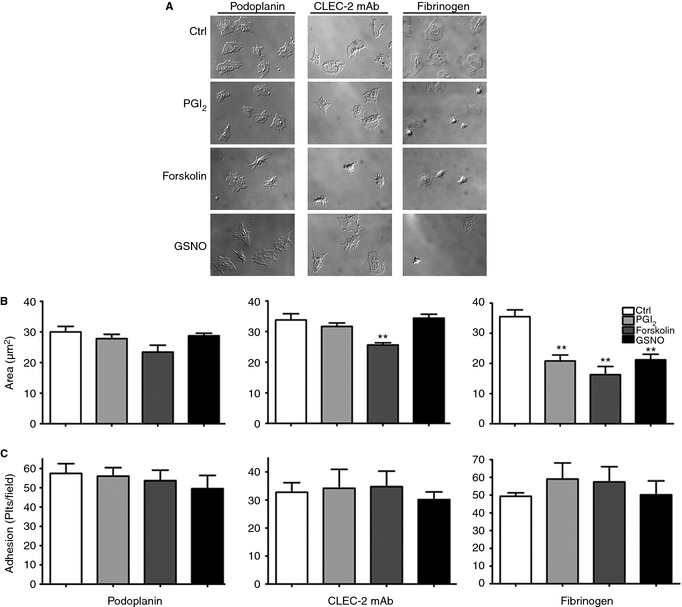

Effect of cyclic nucleotides on CLEC‐2‐dependent spreading

The effect of cyclic nucleotides on adhesion and spreading of platelets to mouse podoplanin and CLEC‐2 mAb was investigated. A concentration of PGI2 (1 μm) that completely inhibited aggregation and secretion had no effect on spreading of platelets on either ligand (Fig. 4A,B). A similar result was seen with a 10‐fold higher concentration of PGI2 (not shown). Similarly, GSNO (1 mm) had no effect. Weak inhibition of spreading was observed on CLEC‐2 mAb with 10 μm forskolin (Fig. 4A,B), which induces a sustained increase in cAMP. In contrast, spreading of thrombin‐activated platelets on fibrinogen was markedly inhibited by PGI2, GSNO and forskolin (Fig. 4A,B). Platelet adhesion was unaltered under any of the above conditions (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

cAMP‐elevation marginally affects CLEC‐2‐dependent spreading. 2 × 107 per mL washed platelets were treated with PGI2 (1 μm), forskolin (10 μm) or GSNO (1 mm) before spreading on coverslips coated with 10 μg mL−1 recombinant podoplanin or CLEC‐2 mAb. Control experiments with thrombin‐activated platelets (0.1 U mL−1) on 100 μg mL−1 fibrinogen were performed. Coverslips were imaged using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy (A). Platelet areas are expressed as mean of mean area/experiment ± SEM. One hundred platelets/experiment were analyzed. Statistical differences were evaluated by anova and Dunnet's post‐test (**P < 0.01) (B). Results are expressed as mean of mean number of platelets/experiment ± SEM (n = 3–6) (C).

Spreading of platelets on HLECs was less marked than on immobilized ligands, because of the mobility of podoplanin. Figure 5(A) shows exposure of P‐selectin in CD41‐stained platelets adhering to HLECs expressing podoplanin, thus confirming that platelet activation had occurred. Spreading (Fig. 5A,B), P‐selectin exposure (Fig. 5C) and adhesion (not shown) on HLECs were unaltered or minimally reduced in the presence of PGI2 (1 μm), forskolin (10 μm) or GSNO (1 mm), while mouse platelets expressing a functionally inactive Syk did not express P‐selectin on HLECs (not shown). These results demonstrate that cAMP or cGMP elevation minimally inhibits or does not inhibit platelet activation by membrane‐bound podoplanin. Consistent with this, neither cAMP nor cGMP inhibited the elevation of Ca2+ in platelets on HLECs (Fig. 5D), whereas the Syk inhibitor PRT060318 (5 μm) significantly reduced [Ca2+]i.

Figure 5.

Cyclic nucleotides do not affect platelet spreading, P‐selectin exposure and Ca2+ elevation on HLECs. Washed platelets (5 × 108 per mL) were treated with 1 μm PGI2, 10 μm forskolin, 1 mm GSNO or vehicle and allowed to spread on a HLEC monolayer for 1 h at 37 °C. Slides were stained for podoplanin, CD41 and P‐selectin and imaged using confocal microscopy (scale bar = 20 μm) (A). Area of attached platelets (B) and P‐selectin/CD41 intensity (C) were evaluated (n = 3). 2 × 107per mL Fura‐2‐loaded platelets were treated as above or with 5 μm PRT060318 (PRT) and allowed to attach on a HLEC monolayer. Attachment of platelets was recorded for 20 min. Average [Ca2+]i concentrations were calculated and reported as mean ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical differences were evaluated with anova and Dunnet's post‐test (*P < 0.05) (D).

We have performed a series of experiments to establish the effectiveness of cyclic nucleotide‐elevating agents at the different time‐points used in this study (Figure S5). The activation of integrin αIIbβ3 measured by flow cytometry was inhibited by PGI2 (or forskolin, not shown) at 3 min and was retained by 45 min. In contrast, GSNO partially inhibited at 3 min but this effect was lost at 45 min, consistent with the aggregation results (Figure S5A,B).

The small G protein Rac has a critical role in platelet spreading on multiple surfaces 24. Consistent with this, the Rac inhibitor EHT1864 blocked spreading on podoplanin (Figure S5C). Rac activation induced by CLEC‐2 mAb in suspension was maintained in the presence of PGI2 at 45 min, consistent with the absence of an effect on spreading at this time (Figure S5D). To confirm the effectiveness of PGI2 and GSNO in activating PKA and PKG, respectively, in CLEC‐2‐stimulated platelets, we studied phosphorylation of the common PKA and PKG substrate VASPSer239 and PKA substrate VASPSer157 15 (Figure S5E). PGI2‐dependent VASP phosphorylation in Ser239 and 157 was lost after 3 min, consistent with the short life of the compound, even though inhibition of fibrinogen binding and fibrinogen spreading was maintained. Forskolin and GSNO‐dependent VASPSer239 phosphorylation were maintained up to 60 min.

Discussion

Cyclic nucleotide‐elevating agents are released by intact endothelial cells from both vascular and lymphatic lineages and are powerful inhibitors of platelet activation. This therefore raises the question of how podoplanin on LECs is able to mediate platelet activation and thereby prevent blood‐lymphatic mixing during development. The present study addresses this through demonstration that platelet activation by CLEC‐2 ligands, including podoplanin, is only sensitive to elevation of cAMP in suspension, but not on an immobilized monolayer or on podoplanin‐expressing cells. Furthermore, CLEC‐2‐dependent activation is resistant to elevation of cGMP both in suspension and on a cell surface. These observations are therefore consistent with the critical role of podoplanin‐mediated platelet activation in prevention of blood‐lymphatic mixing during development.

Our results allow us to draw a number of conclusions relative to the behaviour of cyclic nucleotides in mouse platelets and their effect on CLEC‐2 activation. PGI2 prevents platelet aggregation in response to CLEC‐2 ligands and this is partly mediated through impaired signaling by the C‐type lectin receptor as revealed by measurement of tyrosine phosphorylation. In comparison, GSNO has a much weaker effect on platelet aggregation induced by CLEC‐2, which is overcome by high concentrations of agonists. The weak effect of GSNO is likely to be due to a lower level of activation of PKG relative to PKA, as illustrated by the relatively weak phosphorylation of VASPSer239. PGI2 and GSNO have no effect on platelet adhesion and spreading on immobilized CLEC‐2 ligands or LECs, thereby demonstrating that the initial events that underlie adhesion and spreading are refractory to cyclic nucleotides. Furthermore, P‐selectin exposure and Ca2+ elevation are also not inhibited whereas only a very high concentration of forskolin has a partial effect on spreading on CLEC‐2 mAb and P‐selectin exposure on platelets adhering on LECs.

Lymphatic development is normal in mice deficient in αIIbβ3 26, suggesting that it is independent of platelet aggregation. Thus, the inhibitory effect of PGI2 against CLEC‐2‐mediated aggregation would not interfere with the role of CLEC‐2 in lymphatic development. The molecular mechanism underlying the role of podoplanin and CLEC‐2 in lymphatic development remains unclear. Previously, we have demonstrated that direct contact with platelets impairs LEC migration and cell‐cell interactions through a pathway that is dependent on CLEC‐2 and Syk 5. The present results suggest that platelet adhesion to LECs and subsequent activation would not be altered by elevation of cGMP and only minimally impaired by elevation of cAMP. The present observations may have important implications with respect to the interaction of CLEC‐2 and podoplanin on other cells. It has been proposed that the interaction of platelet CLEC‐2 with podoplanin on circulating tumor cells plays a role in hematogenous metastatic dissemination 27. In this case, platelets would be exposed to cyclic nucleotide‐elevating agents produced by the intact vascular endothelium, but these would have only a minimal effect on responses mediated by CLEC‐2 signaling. This is consistent with the report that formation of human platelet aggregates on tumor cells under flow conditions is delayed but not abolished in the presence of PGI2 28.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that CLEC‐2‐dependent platelet activation is insensitive to cGMP‐elevation and only partially sensitive to cAMP‐elevation, but only in suspension studies. The relative refractoriness of CLEC‐2‐dependent signaling to cyclic nucleotides when activated on a surface explains the ability of podoplanin‐expressing LECs to maintain platelet activation, which is essential to prevent blood‐lymphatic mixing during development.

Addendum

A. Borgognone designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. L. Navarro‐Nunez and J. N. Correia designed and performed experiments and analyzed data. S. Thomas designed and performed experiments. A. Pollitt and J. Eble provided reagents and revised the manuscript. F. M. Pulcinelli and M. Madhani designed experiments and revised the manuscript. S. P. Watson designed experiments, wrote the manuscript and supervised the work.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interests

The authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Antibodies used and sources.

Fig. S1. Marginal effect of apyrase or indomethacin on CLEC‐2‐dependent platelet aggregation.

Fig. S2. Lack of effect of SNP on CLEC‐2‐dependent platelet aggregation and tyrosine phosphorylation.

Fig. S3. Effect of cyclic nucleotide‐elevation on CLEC‐2‐dependent platelet aggregation and tyrosine phosphorylation in human platelets.

Fig. S4. Rhodocytin‐dependent tyrosine phosphorylation is partially reduced by cyclic nucleotide‐elevation.

Fig. S5. cAMP and cGMP have differential effects on different platelet pathways.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Birmingham Protein Expression Facility, which provided a protein expression service for podoplanin. This work was funded by the British Heart Foundation (PG/11/119 and PG/12/22/29485) and Wellcome Trust (088410/Z/09/Z). AB was supported by ‘Sapienza’ University of Rome, LNN by the Spanish Ministry of Education (EX2009‐0242), JAE by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG‐grant: SFB/TR23 project A8). SPW is a BHF Chair.

Borgognone A, Navarro‐Núñez L, Correia JN, Pollitt AY, Thomas SG, Eble JA, Pulcinelli FM, Madhani M, Watson SP. CLEC‐2‐dependent activation of mouse platelets is weakly inhibited by cAMP but not by cGMP. J Thromb Haemost 2014; 12: 550–9

References

- 1.Severin S, Pollitt AY, Navarro‐Nunez L, Nash CA, Mourao‐Sa D, Eble JA, Senis YA, Watson SP. Syk‐dependent phosphorylation of CLEC‐2: a novel mechanism of hem‐immunoreceptor tyrosine‐based activation motif signaling. J Biol Chem 2011; 286: 4107–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson SP, Herbert JM, Pollitt AY. GPVI and CLEC‐2 in hemostasis and vascular integrity. J Thromb Haemost 2010; 8: 1456–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki‐Inoue K, Inoue O, Ding G, Nishimura S, Hokamura K, Eto K, Kashiwagi H, Tomiyama Y, Yatomi Y, Umemura K, Shin Y, Hirashima M, Ozaki Y. Essential in vivo roles of the C‐type lectin receptor CLEC‐2: embryonic/neonatal lethality of CLEC‐2‐deficient mice by blood/lymphatic misconnections and impaired thrombus formation of CLEC‐2‐deficient platelets. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 24494–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertozzi CC, Schmaier AA, Mericko P, Hess PR, Zou Z, Chen M, Chen CY, Xu B, Lu MM, Zhou D, Sebzda E, Santore MT, Merianos DJ, Stadtfeld M, Flake AW, Graf T, Skoda R, Maltzman JS, Koretzky GA, Kahn ML. Platelets regulate lymphatic vascular development through CLEC‐2‐SLP‐76 signaling. Blood 2010; 116: 661–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finney BA, Schweighoffer E, Navarro‐Nunez L, Benezech C, Barone F, Hughes CE, Langan SA, Lowe KL, Pollitt AY, Mourao‐Sa D, Sheardown S, Nash GB, Smithers N, Reis e Sousa C, Tybulewicz VL, Watson SP. CLEC‐2 and Syk in the megakaryocytic/platelet lineage are essential for development. Blood 2012; 119: 1747–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osada M, Inoue O, Ding G, Shirai T, Ichise H, Hirayama K, Takano K, Yatomi Y, Hirashima M, Fujii H, Suzuki‐Inoue K, Ozaki Y. Platelet activation receptor CLEC‐2 regulates blood/lymphatic vessel separation by inhibiting proliferation, migration, and tube formation of lymphatic endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 22241–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ichise H, Ichise T, Ohtani O, Yoshida N. Phospholipase Cgamma2 is necessary for separation of blood and lymphatic vasculature in mice. Development 2009; 136: 191–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herzog BH, Fu J, Wilson SJ, Hess PR, Sen A, McDaniel JM, Pan Y, Sheng M, Yago T, Silasi‐Mansat R, McGee S, May F, Nieswandt B, Morris AJ, Lupu F, Coughlin SR, McEver RP, Chen H, Kahn ML, Xia L. Podoplanin maintains high endothelial venule integrity by interacting with platelet CLEC‐2. Nature 2013; 502: 105–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwarz UR, Walter U, Eigenthaler M. Taming platelets with cyclic nucleotides. Biochem Pharmacol 2001; 62: 1153–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mannheimer E, Sinzinger H, Oppolzer R, Silberbauer K. Prostacyclin synthesis in human lymphatics. Lymphology 1980; 13: 44–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oguogho A, Aghajanian AA, Sinzinger H. Prostaglandin synthesis in human lymphatics from precursor fatty acids. Lymphology 2000; 33: 62–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leak LV, Cadet JL, Griffin CP, Richardson K. Nitric oxide production by lymphatic endothelial cells in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1995; 217: 96–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizuno R, Koller A, Kaley G. Regulation of the vasomotor activity of lymph microvessels by nitric oxide and prostaglandins. Am J Physiol 1998; 274: R790–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rehal S, Blanckaert P, Roizes S, von der Weid PY. Characterization of biosynthesis and modes of action of prostaglandin E2 and prostacyclin in guinea pig mesenteric lymphatic vessels. Br J Pharmacol 2009; 158: 1961–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smolenski A. Novel roles of cAMP/cGMP‐dependent signaling in platelets. J Thromb Haemost 2012; 10: 167–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eble JA, Beermann B, Hinz HJ, Schmidt‐Hederich A. alpha 2 beta 1 integrin is not recognized by rhodocytin but is the specific, high affinity target of rhodocetin, an RGD‐independent disintegrin and potent inhibitor of cell adhesion to collagen. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 12274–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schacht V, Dadras SS, Johnson LA, Jackson DG, Hong YK, Detmar M. Up‐regulation of the lymphatic marker podoplanin, a mucin‐type transmembrane glycoprotein, in human squamous cell carcinomas and germ cell tumors. Am J Pathol 2005; 166: 913–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes CE, Pollitt AY, Mori J, Eble JA, Tomlinson MG, Hartwig JH, O'Callaghan CA, Futterer K, Watson SP. CLEC‐2 activates Syk through dimerization. Blood 2010; 115: 2947–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 1985; 260: 3440–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollitt AY, Grygielska B, Leblond B, Desire L, Eble JA, Watson SP. Phosphorylation of CLEC‐2 is dependent on lipid rafts, actin polymerization, secondary mediators, and Rac. Blood 2010; 115: 2938–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato Y, Fujita N, Kunita A, Sato S, Kaneko M, Osawa M, Tsuruo T. Molecular identification of Aggrus/T1alpha as a platelet aggregation‐inducing factor expressed in colorectal tumors. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 51599–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki‐Inoue K, Kato Y, Inoue O, Kaneko MK, Mishima K, Yatomi Y, Yamazaki Y, Narimatsu H, Ozaki Y. Involvement of the snake toxin receptor CLEC‐2, in podoplanin‐mediated platelet activation, by cancer cells. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 25993–6001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukherjee S, Zhu J, Zikherman J, Parameswaran R, Kadlecek TA, Wang Q, Au‐Yeung B, Ploegh H, Kuriyan J, Das J, Weiss A. Monovalent and multivalent ligation of the B cell receptor exhibit differential dependence upon Syk and Src family kinases. Sci Signal 2013; 6: ra1. 10.1126/scisignal.2003220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarty OJ, Larson MK, Auger JM, Kalia N, Atkinson BT, Pearce AC, Ruf S, Henderson RB, Tybulewicz VL, Machesky LM, Watson SP. Rac1 is essential for platelet lamellipodia formation and aggregate stability under flow. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 39474–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gegenbauer K, Elia G, Blanco‐Fernandez A, Smolenski A. Regulator of G‐protein signaling 18 integrates activating and inhibitory signaling in platelets. Blood 2012; 119: 3799–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emambokus NR, Frampton J. The glycoprotein IIb molecule is expressed on early murine hematopoietic progenitors and regulates their numbers in sites of hematopoiesis. Immunity 2003; 19: 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowe KL, Navarro‐Nunez L, Watson SP. Platelet CLEC‐2 and podoplanin in cancer metastasis. Thromb Res 2012; 129(Suppl 1): S30–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bazou D, Santos‐Martinez MJ, Medina C, Radomski MW. Elucidation of flow‐mediated tumour cell‐induced platelet aggregation using an ultrasound standing wave trap. Br J Pharmacol 2011; 162: 1577–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Antibodies used and sources.

Fig. S1. Marginal effect of apyrase or indomethacin on CLEC‐2‐dependent platelet aggregation.

Fig. S2. Lack of effect of SNP on CLEC‐2‐dependent platelet aggregation and tyrosine phosphorylation.

Fig. S3. Effect of cyclic nucleotide‐elevation on CLEC‐2‐dependent platelet aggregation and tyrosine phosphorylation in human platelets.

Fig. S4. Rhodocytin‐dependent tyrosine phosphorylation is partially reduced by cyclic nucleotide‐elevation.

Fig. S5. cAMP and cGMP have differential effects on different platelet pathways.