Abstract

Background & Aims

DCC and UNC5C, Netrin-1 dependence receptors, perform an important role in intestinal epithelial biology. Both receptors frequently are down-regulated in colorectal cancer (CRC). Although CRCs frequently lose DCC owing to deletions at 18q, the mechanism for the UNC5C loss is poorly understood. We hypothesized that UNC5C is silenced epigenetically in CRC, and that there are interactions between losses of UNC5C and DCC in colorectal tumorigenesis.

Methods

Gene expression and epigenetic analysis of UNC5C was examined in 8 CRC cell lines, 147 sporadic CRCs with corresponding normal mucosa, and 52 adenomatous polyps (APs). Allelic imbalances at DCC were determined in CRCs. The molecular analyses were compared with genetic and clinicopathologic features.

Results

All CRC cell lines showed UNC5C methylation and an associated loss of gene expression. Treatment with 5-Aza-2’-deoxycytidine resulted in restoration of gene transcription. UNC5C methylation was significantly higher in CRCs (76.2%) and APs (63.5%) than in corresponding normal mucosa (6%; P < .0001). Allelic imbalance at DCC was observed in 61% of CRCs. Overall, 89.3% of CRCs had alterations of one of the dependence receptors. UNC5C methylation occurred predominantly in the earlier lesions (APs and early CRCs), whereas DCC losses were more often in advanced CRCs.

Conclusions

The majority of CRCs harbor defects in Netrin-1 receptors, emphasizing the importance of this growth regulatory pathway in cancer. Furthermore, the timing of the molecular alterations in the Netrin-1 receptors is not random because UNC5C inactivation occurs early, whereas DCC losses occurs in later stages of multistep colorectal carcinogenesis.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) occurs as a consequence of the successive accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations in multiple genes that control epithelial cell growth and other cellular behaviors. Three mechanisms involved in increasing the diversity of gene expression in CRC include: microsatellite instability (MSI), chromosomal instability, and the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP).1–5 Chromosomal instability can be found in approximately half of all sporadic CRCs and is characterized by aneuploidy and large-scale chromosomal duplications, deletions, and rearrangements.1 The discovery of CIMP has been more recent, and represents excessive, aberrant methylation of CpG dinucleotides (or CpG islands) that preferentially occurs in the promoter regions of ~ 50% of tumor-suppressor genes.3,6,7 Methylation of these CpG islands and associated modifications in histone complexes can result in transcriptional silencing of genes in an epigenetic manner.3,8 MSI, which occurs in 12%–15% of sporadic CRCs, is most often a consequence of CIMP when the DNA mismatch repair gene hMLH1 becomes a target of epigenetic silencing.9 Even though some overlap exists between genetic and epigenetic instability pathways in the colon, recent work suggests that CIMP and chromosomal instability represent 2 inversely related mechanisms of genomic instability in CRC.2

A common feature of chromosomal instability in CRC is that these neoplasms frequently show loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at chromosomes 5q, 17p, and 18q, which has been linked to the loss of function of APC, p53, and the DCC/ SMAD genes, respectively.1,10 Finding frequent losses at 18q was instrumental in the initial discovery of DCC.11 The role of DCC as a tumor-suppressor gene was questioned because mutations in DCC rarely were detected, and mouse studies failed to provide a convincing phenotype in knockout models.12,13 The presence of the closely linked SMAD genes raised the possibility that the linkage between cancer and LOH at 18q was related more directly to losses of the SMAD genes than DCC.14 However, recent studies with new data argue in favor of a role for DCC in regulating growth and suppressing metastasis.15–17

The recent discovery that both DCC and UNC5H serve as dependence receptors for Netrin-1 (NTN1) have rein-vigorated support for a tumor-suppressor role of DCC in human cancer.15,16,18,19 NTN1 belongs to a family of laminin-related secreted proteins in the brain and other tissues.20 It has been suggested that NTN1 acts through DCC and UNC5H, which function as dependence receptors in colonic and other tissues.18 These receptors induce apoptosis when not engaged with their ligand netrin, but mediate signals for proliferation, differentiation, or migration when ligand-bound.15,21,22 In the gut, NTN1 plays a role in mucosal integrity, epithelial cell migration, and tissue renewal by inducing cell survival in proliferating crypt progenitors, where netrin levels are high. At the villus tips, where netrin levels are low, both DCC and UNC5H promote apoptosis and cell shedding because the death receptors are expressed constitutively throughout the crypt-villus axis.15,23,24

Interestingly, NTN1 is also a ligand for the UNC5H-receptor family.25,26 UNC5A, UNC5B, and UNC5C are type I transmembrane receptors involved in axonal guidance in the development of the nervous system. Although UNC5H receptors usually are expressed in adult human tissues, a recent report highlighted that these receptors frequently are down-regulated in several types of human cancers.27 The loss of UNC5C expression is particularly prominent in CRC.27 Unlike DCC deletions, the molecular mechanisms responsible for the loss of UNC5C expression are poorly understood. The only report addressing this issue provided some evidence that deletions at chromosome 4q in a subset of CRCs may explain the loss of UNC5C expression.27 In this report, based on limited in vitro data, the investigators suggested that epigenetic modifications of UNC5C may be responsible for down-regulation of its expression, but these data precluded determination of whether such events occurred in a tumor-specific manner in CRC.27

Given the apparent importance of the netrin pathway in the maintenance of gut epithelium, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms that mediate loss of expression of these genes, and the consequence of combined losses of these receptors in a series of premalignant and malignant colonic tissues, is warranted. This study investigated these issues by analyzing a panel of CRC cell lines, adenomatous polyps (APs), and CRCs. Herein we report that the majority of CRCs show the loss of both NTN1 receptors. We also provide data suggesting that the inactivation of these receptors is mediated through both genetic and epigenetic mechanisms, and that these processes are orchestrated in a sequential manner during the evolution of multistep colorectal carcino-genesis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Primary CRC Tissues

Eight human colon cancer cell lines representing all the major pathways of genomic instability in CRC included Caco2, HT29, SW837, SW480, HCT116, LoVo, RKO, SW48, and CCD18Co (a colon fibroblast cell line), and were purchased from American Type Culture Collections (Manassas, VA). All cell lines were cultured in appropriate medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 IU/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

We prospectively collected tissue specimens of primary CRCs and their matched corresponding normal mucosa (CNM) from 147 patients who had undergone surgery at the Okayama Saiseikai Hospital and Okayama University Hospital (Okayama, Japan). All CNM tissues were obtained from sites adjacent to, but at least 10 cm away from, the original tumor. In addition, we obtained 52 colorectal APs from a different cohort at Chikuba Hospital (Okayama, Japan). All patients provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the institutional review boards of all institutions involved.

5-Aza-2’-Deoxycytidine Treatment

SW480 and HCT116 cells were plated at 2 × 105 cells/100 mm culture dish. After 24 hours of exponential growth, SW480 cells were treated with 5 μmol/L 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5AzaD; Sigma-Aldrich Inc, St Louis, MO) and HCT116 cells were treated with 0.1 μmol/L 5AzaD for 72 hours, respectively. Control cell lines were treated with equal volumes of phosphate-buffered saline added to the culture medium. The culture medium containing 5AzaD was changed every 24 hours. At the end of the treatment periods, DNA and RNA were extracted 24 hours posttreatment and processed for analyses.

DNA and RNA Extraction

Genomic DNA from the cell lines was extracted using QIAamp DNA mini kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). All CRCs, CNM, and 6 of the 52 APs were fresh-frozen tissue specimens, from which DNA was extracted using standard procedures that included proteinase-K digestion and phenol-chloroform extraction. DNA from the remaining 46 polyps, which were formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens, was extracted using Takara DEXPAT kits (Takara Bio Inc, Otsu, Japan). Total RNA from cell lines was obtained using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies Inc, Carlsbad, CA).

Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

The first-strand complementary DNA synthesis was performed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies Inc, Carlsbad, CA) with a total of 1 μg RNA. Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed using UNC5C-specific primer pairs that have been described previously.28 β-actin amplification was used as an internal control (Table 1). The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel (ISC Bio Express, Kaysville, UT) and were imaged using a Gel Logic 200 Kodak Molecular Imaging System (Kodak, New Haven, CT).

Table 1.

Primer Sequences for RT-PCR, COBRA, and Bisulfite Sequencing Analysis

| Assay | Primer name | Primer sequence | Product size, bp |

|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR | RT-UNC5C-F | 5′-TGCAAATGCTCGTGCTACCT-3′ | 258 |

| RT-UNC5C-R | 5′-TGTGGTCCTTCTGATGAACCC-3′ | ||

| RT-β actin-F | 5′-TCACCATGGATGATGATATCGCC-3′ | 282 | |

| RT-β actin-R | 5′-CCACACGCAGCTCATTGTAGAAGG-3′ | ||

| COBRA | COBRA-F | 5′-GTATTGGGAAAGAGGGATTTTTAAA-3′ | 157 |

| COBRA-R | 5′-AACCCCACTAAACAAAAACTAAATC-3 | ||

| Bisulfite Sequence | Bis-F | 5′-GGTGTTTGTGTGTGTTTTTTATAGG-3′ | 336 |

| COBRA-R | 5′-AACCCCACTAAACAAAAACTAAATC-3′ |

Bisulfite Modification and Combined Bisulfite Restriction Assay

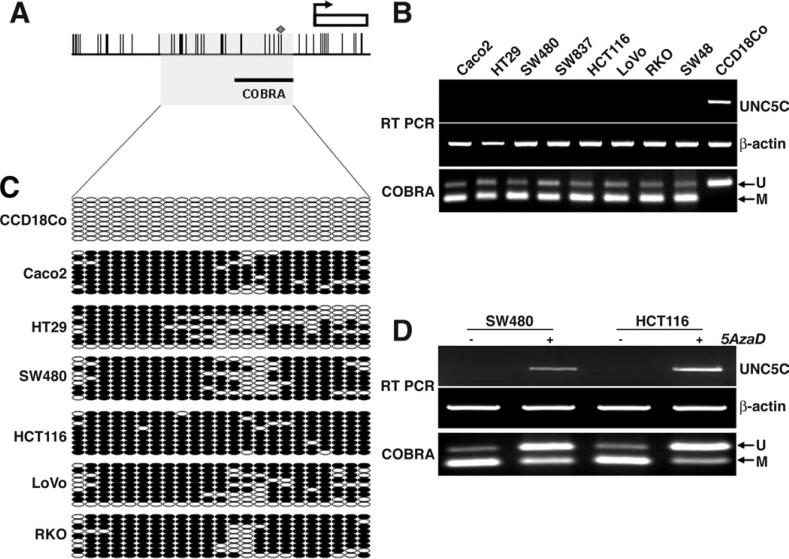

Bisulfite modification of genomic DNA from CRC cell lines and clinical specimens was performed as described by Herman et al.29 We first identified tentative CpG islands in the promoter region of the UNC5C gene by mapping analysis using a CpG island search program (http://www.uscnorris.com/cpgislands/cpg.cgi). There were 42 CpG sites within the UNC5C promoter region investigated in this study (Figure 1A). We subsequently analyzed the UNC5C methylation status using the combined bisulfite restriction assay (COBRA).30

Figure 1.

UNC5C promoter hypermethylation in colon cancer cell lines. (A) The 5’-promoter region of the UNC5C gene. All CpG dinucleotide sequences are represented by vertical bars across the horizontal line depicting the promoter sequence. The solid line at the bottom right represents the specific region assayed by COBRA to amplify nucleotides —216 to –60 of the promoter region (in which the start codon of UNC5C is defined as +1). The diamond on one of the vertical bars indicates the BstUI CpG restriction site. The gray rectangular square designates the region by bisulfite sequencing across nucleotide positions –395 to –60. (B) Correlation of UNC5C hypermethylation and loss of UNC5C mRNA expression in CRC cell lines. Eight CRC cell lines and CCD18Co cells were analyzed for mRNA expression by RT-PCR of the UNC5C and β-actin genes. The lowest panel illustrates the methylation profile obtained from COBRA. ←M, methylated DNA product resulting from BstUI-digestion. ←U, unmethylated band. (C) Bisulfite sequencing of CRC cell lines. PCR products were cloned into a TOPO cloning vector and sequenced. For each cell line, at least 9 clones were sequenced. Empty circles indicate unmethylated CpG sites, filled circles represent methylated CpG sites. (D) 5AzaD treatment restores UNC5C expression in CRC cell lines. SW480 and HCT116 were treated with 5AzaD at 5 μmol/L and 0.1 μmol/L concentrations, respectively, for 72 hours. –, Mock untreated; +, 5AzaD treated

PCR amplification was performed using the primer sets COBRA-F and COBRA-R (Table 1 and Figure 1A). Before initiating restriction endonuclease digestion, a small volume of PCR product was electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel to validate the specificity and efficiency of PCR. Thereafter, restriction enzyme digestion was performed by using BstUI (New England Bio Labs, Ipswich, MA). The percentages of fully methylated BstUI sites were calculated by determining the ratios between the BstUI-cleaved PCR product and the total amount of PCR product loaded.

Cloning and Sodium Bisulfite Sequencing

Bisulfite-modified DNA from cell lines and clinical specimens was amplified using primer sets Bis-F and COBRA-R (Table 1). Each of the PCR products subsequently was cloned using the TOPO-TA cloning system (Invitrogen Life Technologies Inc). Nine to 11 white colonies indicating positive clones with PCR products were sequenced using ABI PRISM Big Dye Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kits on an ABI PRISM 3100 Avant Genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

LOH Analysis

A set of 3 polymorphic microsatellite markers (D18S58, D18S64, and D18S69) was used to determine LOH at chromosome 18q. PCR amplifications were performed on genomic DNA templates from both tumor and CNM tissues using fluorescently labeled primers. The amplified PCR products were electrophoresed on an ABI PRISM 3100 Avant Genetic analyzer and analyzed by GeneMapper fragment analysis software (Applied Biosystems). When comparing the signal intensities of individual markers in tumor DNA with that of the corresponding normal DNA, a reduction of at least 40% in the signal intensity was considered indicative of LOH.

MSI, KRAS, and V600E BRAF Mutation Analyses

MSI, KRAS, and V600E BRAF mutation analyses data were available for all 147 patients from our previous study.31

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP software (version 4.05J; SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). First, UNC5C methylation levels were analyzed as a continuous variable, as were computed means, standard error of the means, and SDs. Next, the methylation status of the UNC5C promoter was analyzed as a categoric variable (positive, methylation level ≥5%; negative, methylation level <5%). Differences in frequencies were evaluated by the Fisher exact test, χ2 test, or a Wilcoxon/ Kruskal–Wallis test. The associations between UNC5C promoter methylation and clinicopathologic variables were analyzed using χ2 tests. All reported P values were 2-sided and a P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Hypermethylation of UNC5C Induces Transcriptional Silencing in CRC Cell Lines

By using RT-PCR, we examined UNC5C gene expression in the panel of 8 CRC cell lines and CCD18Co cells. All CRC cell lines (but not CCD18Co) lacked expression of UNC5C gene transcripts (Figure 1B). To determine the mechanism for loss of UNC5C expression, we measured the methylation status of the UNC5C promoter by COBRA, and observed that all CRC cell lines had hypermethylation of the UNC5C promoter. Contrari-wise, CCD18Co cells, which expressed UNC5C, did not show UNC5C promoter methylation (Figure 1B). To confirm COBRA results, we performed bisulfite sequencing in all cell lines. Most cancer cell lines were heavily methylated at individual CpG dinucleotides, whereas CCD18Co was unmethylated in each sequenced clone (Figure 1C).

We tested the hypothesis that epigenetic silencing caused the loss of UNC5C expression in cultured CRC cells by treating SW480 and HCT116 cells with the demethylating agent 5AzaD. As anticipated, 5AzaD treatment restored UNC5C messenger RNA (mRNA) expression, and this was associated with significant demethylation of the promoter region of UNC5C by COBRA (Figure 1D).

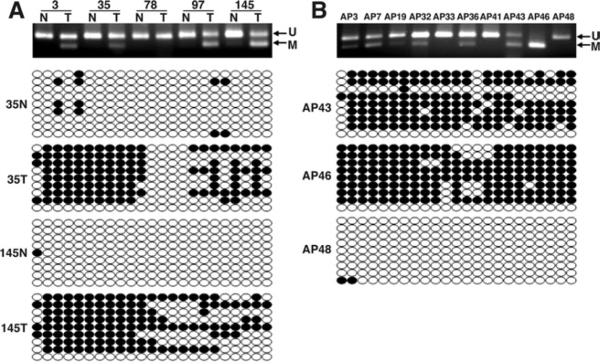

UNC5C Is Hypermethylated Frequently in Colorectal Tissues

We tested the hypothesis that UNC5C methylation is a common event in CRC by investigating its methylation status in a cohort of 147 CRCs and CNM tissue specimens, and a group of 52 APs. A panel of representative COBRA results is depicted in Figure 2. We analyzed these results by using mean UNC5C methylation levels as continuous variables. Using a cut-off value of greater than 1% methylation as a criterion for positive methylation, we observed that the UNC5C promoter was hyper-methylated in 77.6% (114 of 147) of CRCs, 63.5% (33 of 52) of APs, and 14.3% (21 of 147) of CNMs. The overall degree of UNC5C methylation was significantly higher in CRCs and APs compared with CNMs (34% ± 22% [SD] in CRCs, 56% ± 33% in APs, and 4.7% ± 2.1% in CNMs; P < .0001, Wilcoxon/Kruskal–Wallis test). By using these results, we optimized the cut-off value for UNC5C methylation at 5% (ie, ≥5% methylation < positive and <5% methylation = negative). Using this criterion, we observed significant aberrant hypermethylation of UNC5C in 76.2% of CRCs (112 of 147) and 63.5% of APs (33 of 52) compared with 6.1% of CNMs (9 of 147) (P < .0001, χ2 test). Of note, even among APs, UNC5C methylation was limited to the advanced adenomas (33 of 46), and was not present in any of the smaller nonadvanced polyps (0 of 6).

Figure 2.

UNC5C promoter hypermethylation in colorectal tissues. (A) COBRA and bisulfite sequencing analysis of UNC5C in CRCs. Representative results for COBRA and bisulfite sequencing analysis are shown in the upper and lower panels, respectively. ←M, methylated DNA products after BstUI digestion. →U, unmethylated alleles. (B) COBRA and bisulfite sequencing analysis for UNC5C in APs. Representative examples of data obtained from COBRA and bisulfite sequencing in polyps are shown.

Methylation data obtained by COBRA were confirmed with bisulfite sequencing analysis. Sequencing data revealed dense methylation of CpG islands in CRCs, but showed no evidence for this epigenetic change in the CNM (Figure 2A). Data from APs were confirmed similarly (Figure 2B). Collectively, these data indicate that UNC5C expression frequently is lost or down-regulated in colorectal neoplasms, and that this event is associated with the aberrant methylation of the promoter region of the UNC5C gene.

UNC5C Methylation Is Associated With Larger Polyp Size, Older Age, Histology, and Mutant BRAF

We next examined associations between UNC5C promoter methylation status as a categoric variable and the clinicopathologic and genetic features of patients with APs and CRCs (Tables 2 and 3). We found significantly more UNC5C methylation in larger vs smaller polyps (13.7 vs 11.4 mm, P = .02, Wilcoxon/Kruskal– Wallis test, Table 2), whereas there were no significant associations among any of the other variables.

Table 2.

Relationships Between UNC5C Methylation and Clinicopathologic Features in Patients With APs

|

UNC5C methylation status no. (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methylateda | Unmethylated | P value | ||

| Age, y | ≥65 (n = 19) | 13 (68) | 6 (32) | .57b |

| <65(n = 33) | 20 (61) | 13 (68) | ||

| Sex | Female (n = 10) | 7 (70) | 3 (30) | .63b |

| Male (n = 42) | 26 (62) | 16 (38) | ||

| Location | Proximal (n = 16) | 10 (63) | 6 (38) | .92b |

| Distal (n = 36) | 23 (64) | 13 (36) | ||

| Histology | TA (n = 40) | 24 (60) | 16 (40) | .34b |

| TA with villous (n = 12) | 9(75) | 3 (25) | ||

| Size | Mean diameter, mm (95% confidence interval) | 13.7 (12.0–15.2) | 11.4 (9.2–13.5) | .02c |

TA, tubular adenoma; TA with villous, TA with villous features.

Methylated cases were categorized as those with ≥5% promoter methylation.

P values were calculated using the χ2 test.

P value was calculated using the Wilcoxon/Kruskal–Wallis test.

Table 3.

Relationships Among UNC5C Methylation and Clinicopathologic Characteristics in Patients With CRC

|

UNC5C methylation status no. (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methylateda | Unmethylated | P value | ||

| Age, y | ≥65 (n = 79) | 67 (85) | 12 (15) | .008 |

| <65 (n = 68) | 45 (66) | 23 (34) | ||

| Sex | Female (n = 50) | 38 (76) | 12 (24) | .97 |

| Male (n = 97) | 74 (76) | 23 (24) | ||

| Location | Proximal (n = 41) | 30 (73) | 11 (27) | .59 |

| Distal (n = 106) | 82 (77) | 24 (23) | ||

| Tumor stage | A (n = 26) | 23 (81) | 5 (19) | |

| (Dukes') | B (n = 42) | 34 (81) | 8 (19) | .65 |

| C (n= 49) | 36 (73) | 13 (27) | ||

| D (n = 30) | 21 (70) | 9 (30) | ||

| Histology | Well (n = 26) | 25 (96) | 1 (4) | |

| Mucinous/poor (n = 11) | 10 (91) | 1 (9) | .002 | |

| Moderate (n = 110) | 77 (70) | 33 (30) | ||

| MSI status | High (n = 4) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Low (n = 43) | 36 (84) | 7 (16) | .08 | |

| Stable (n = 100) | 72 (72) | 28 (28) | ||

| Ras pathway | BRAF mut (n = 4) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| K-RAS mut (n = 45) | 40 (89) | 5 (11) | .006 | |

| Wild type (n = 98) | 68 (69) | 30 (31) | ||

NOTE. P values were calculated by χ2 test.

Mut, mutation.

Methylated cases were categorized as those with ≥5% promoter methylation.

While performing similar analyses in CRCs (Table 3), we found that UNC5C methylation was significantly more frequent in elderly (≥65 y) compared with younger (<65 y) patients (P = .008, χ2 test). However, no significant differences were found when patient sex, tumor location, or tumor stage were compared in methylated vs unmethylated CRCs. In addition, we found that UNC5C methylation was significantly greater in well-differentiated or poorly differentiated mucinous CRCs compared with moderately differentiated CRCs (P = .002, χ2 test). UNC5C methylation also correlated with MSI, although these results were not statistically significant because of the smaller number of MSI-high CRCs investigated in this study. V600E BRAF mutation was associated with significantly greater UNC5C methylation compared with the subset of CRCs that were wild type (P = .006, χ2 test; Table 3).

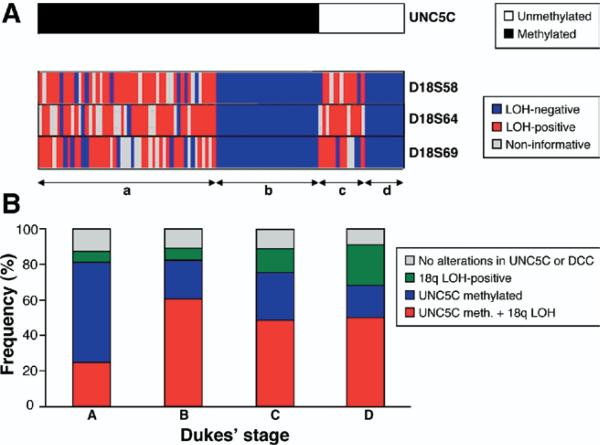

Deletions at the 18q/DCC Locus Are Frequent in CRCs

Because the primary mechanism that accounts for loss of DCC in CRC is deletions in chromosome 18q,11,32,33 we determined the frequency of allelic losses in a panel of LOH markers that mapped closely to DCC. Of the 147 specimens investigated, 70.1% (103 of 147) of cases yielded informative analyses at these 3 loci. Among the informative cases, 18q losses were frequent, and 61.2% (63 of 103) of the CRCs showed allelic imbalance in at least one of the markers (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

LOH at DCC, and its relationship with UNC5C methylation and tumor stage. (A) Methylation profile of UNC5C and LOH of 18q loci. Among the 147 CRCs analyzed for LOH, 103 cases were informative. The upper horizontal bar depicts the methylation status of UNC5C in 103 cancers; the black portion on the left indicates methylated cases, and the white portion on the right indicates unmethylated CRCs. The three lower bars represent LOH results. Red indicates CRCs with LOH at that marker, blue indicates no LOH, and gray represents noninformative cases. a, CRCs that had simultaneous UNC5C methylation and DCC deletion (50 of 103; 48.5%); b, CRCs that showed only UNC5C methylation (29 of 103; 28.2%); c, cases with exclusive 18q LOH (13 of 103; 12.6%); and d, cancers that had neither alteration (11 of 103; 10.7%). (B) Correlation of UNC5C methylation, DCC deletions, and their relationship with tumor stage. The Y-axis represents the prevalence of UNC5C methylation and/or 18q LOH, and the X-axis groups tumors based on Dukes’ stage.

We tested the hypothesis that DCC losses and UNC5C methylation occur concurrently, vs independently of one another. We discovered that 48.5% (50 of 103) of CRC cases had undergone simultaneous methylation of UNC5C and LOH of DCC (Figure 3A). Independent UNC5C promoter methylation or 18q loss alone also was present in 28.2% (29 of 103) and 12.6% (13 of 103) of CRCs, respectively. Considered together, alterations in UNC5C and DCC individually or concurrently were present in 89.3% (92 of 103) of CRCs, and only 10.7% (11 of 103) of tumors lacked evidence for either of these defects.

UNC5C Methylation Occurs Early, Whereas DCC Loss Occurs in Advanced-Stage CRCs

Because UNC5C and DCC both serve as dependence receptors for NTN1, we asked whether defects in these receptors accumulate in a systematic manner, or stochastically, during the development of progressive colorectal neoplasia. Therefore, we looked for associations between UNC5C and/or DCC defects and Dukes’ tumor stage in the 103 CRCs that were informative for both UNC5C methylation and DCC LOH. As shown in Figure 3B, concurrent alterations in the UNC5C and DCC genes were observed more commonly in advanced-stage CRCs (60%, 48%, and 50% for stages B, C, and D, respectively) than in earlier-stage cancers (25% for stage A), although this association did not achieve statistical significance, perhaps because of the small sample size of each stage.

Segregating tumors based on individual defects in either UNC5C or DCC and their relationship with tumor stage, we found that methylation-induced silencing of UNC5C by itself was significantly more frequent in Dukes’ stage A neoplasms, and became progressively less in later-stage CRCs (stage A, 56%; stage B, 21%; stage C, 27%; and stage D, 18%; P = .046, χ2 test). Supporting the finding that UNC5C methylation may be an earlier event in the development of colorectal neoplasia, we observed a similar trend for a higher frequency of UNC5C methylation in APs (63.5%). Contrariwise, the frequency of DCC loss was correlated inversely with early tumor stage. We observed that allelic imbalances at 18q loci showed a gradual increase with advancing Dukes’ stage, although these data did not reach significance (stage A, 6.2%; stage B, 7.1%; stage C, 13.5%; and stage D, 22.7%; P = .39, Fisher exact test).

Discussion

This study investigated the molecular events responsible for abrogation of the netrin pathway in CRC, and the role played by the 2 dependence receptors, UNC5C and DCC. We analyzed a large series of colorectal tissues that included 52 APs, 147 CRCs with adjacent normal mucosa, and a panel of 8 CRC cell lines. We found that both UNC5C and DCC are inactivated in nearly 90% of CRCs, and that these alterations occur through genetic and epigenetic processes. UNC5C inactivation in CRC is primarily a consequence of hypermethylation of its promoter, whereas the loss of DCC is caused principally by deletions at chromosome 18q. We also provide evidence that the timing of molecular alterations in UNC5C and DCC is not random because UNC5C inactivation occurs in earlier neoplastic lesions, whereas LOH of DCC loci accrue progressively through multistep colorectal carcinogenesis.

The recent discovery of a dependence receptor concept suggests that receptors can be functionally important even when not bound by their ligands, which has helped to clarify some of the contentious issues in colorectal tumorigenesis.18 DCC and UNC5C both serve as dependence receptors for NTN1; these receptors transmit cell death signals in the absence of ligand,27,34,35 and the binding of NTN1 to these 2 receptors inhibits apoptosis.15,18 Multiple studies have highlighted the functional role for UNC5H members in human carcinogenesis,36–38 and a recent study elegantly showed a tumor-suppressor role for UNC5C in the colon, wherein ectopic expression of UNC5C in cell lines lacking endogenous UNC5C resulted in the suppression of anchorage-independent growth and an inhibition of Ras-dependent cell invasion.27 The mechanistic details underlying the loss of dependence receptors in human cancers still are unclear, but when these receptors are down-regulated or deleted, this impairs adequate levels of programmed cell death, and provides the malignant cells with selective growth advantage. We sought a better understanding of the molecular events that lead to the inactivation of these dependence receptors.

A prior study reported that 77% of CRCs had experienced loss of UNC5C expression.27 It was suggested that loss of UNC5C was caused by allelic losses of chromo-some 4q, and mutations rarely were observed.27 Allelic losses at 4q have been reported previously in several human cancers, but the frequencies have ranged from 23%–39%.27,39,40 Even if it were assumed that every 4q loss caused loss of UNC5C expression in CRC, this mechanism alone would not account for the UNC5C under-expression in CRC. We performed LOH analyses using the markers suggested in the previous study, but could not confirm those findings, in part because the markers were not informative (data not shown).

We then hypothesized that loss of UNC5C expression in CRC may be mediated through aberrant methylation of its promoter. We first identified the critical CpG island in the UNC5C promoter that associates with loss of gene expression in CRC cell lines. We found that most colon cancer cell lines lacked UNC5C expression, and were methylated in this region. To further confirm that methylation was the cause of UNC5C silencing, we showed restoration of UNC5C expression in the cell lines using the demethylating agent 5AzaD.

We then determined that epigenetic silencing of UNC5C commonly is present in CRC and AP tissues. We found evidence for frequent de novo methylation of UNC5C in both advanced APs and CRCs, which rarely was observed in normal colonic epithelium. The presence of UNC5C methylation in advanced APs is relevant because the risk for advanced adenomas to progress to cancer is much higher than for smaller, early polyps.41,42 We could not perform UNC5C immunochemistry on the clinical materials because an adequate antibody was unavailable. However, we believe this experiment may not be critical because methylation of the promoter region investigated showed a perfect association with loss of expression in the cancer cell lines. Because UNC5C methylation was very frequent in CRC, and associated with MSI as well as mutant BRAF, these data suggest that UNC5C methylation may be a CIMP-sensitive and tumor-specific marker, but may not be CIMP-specific because it would far exceed the reported CIMP frequencies in these cancers.2,43 Although future studies will be required to interrogate this issue in more detail, our data clearly show that UNC5C methylation occurs frequently, and occurs in a tumor-specific manner.

The second netrin receptor, DCC, originally was discovered as a putative tumor-suppressor gene in CRC.11 DCC resides on chromosome 18q, which is the most commonly deleted chromosomal region in colorectal neoplasia.10,11,32,33 Methylation-induced silencing of DCC has been suggested, but the evidence had been inconclusive.44,45 A tumor-suppressor role for DCC has been questioned in studies that failed to show a clear malignant phenotype in DCC knockout mice models.13 However, more recent studies have challenged this and favored a role for DCC in suppressing tumor growth and metastasis.15–17 The recent proposition that DCC serves as a dependence receptor for NTN1 has rejuvenated the notion that DCC functions as a proapoptotic growth suppressor when not bound by its ligand.23,34,35 In the gastrointestinal tract, NTN1 performs an important role in the maintenance and renewal of intestinal epithelium by regulating cell survival or cell death through its interaction with UNC5C and DCC.15,23,24 Any abrogation of the netrin pathway, including dysregulation in NTN1 or its 2 receptors, may inhibit apoptosis, which would be permissive of neoplasia.

Because both DCC and UNC5C share the same netrin ligand and are colocalized in the gut,15,19,25,27 we reasoned that the solitary inactivation of either DCC or UNC5C alone might not be sufficient to promote tumor development in the colon. In this study, we found that a large majority of CRCs showed simultaneous alterations in both DCC and UNC5C, supporting our contention that inactivation of both receptors may be required in the evolution of CRC. Although a lack of sufficient material prevented us from performing LOH analyses for DCC (18q) in the APs, previous studies have indicated that DCC losses probably are quite uncommon in early pre-malignant lesions, and accumulate only at the later stages of CRC development.32,46,47

Our finding that dysregulation of UNC5C predominantly occurs in the early phase of colorectal neoplasia whereas DCC loss occurs later suggests that inactivation of these receptors is not a random process, but occurs in a statistically predictable, sequential manner. These data are consistent with the observation that epigenetic alterations frequently are present in adenoma progression,48 perhaps because methylation-induced silencing results in gene silencing, which has a more predictable outcome than point mutations or chromosomal rearrangements.

In conclusion, we provide the evidence that most CRCs have alterations in both UNC5C and DCC netrin receptors. While UNC5C expression is regulated primarily via epigenetic regulation, DCC defects are mediated through allelic deletions. In addition, the timing of these molecular alterations in the dysregulation of the NTN1 pathway is not random, with UNC5C inactivation occurring earlier, and DCC losses following in the later stages of colorectal carcinogenesis. We propose that the Netrin-1 pathway plays an important role in the adenoma-to-carcinoma sequence in the colon.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants R01 CA72851 and R01 CA98572 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (C.R.B.), and funds from the Baylor Research Institute.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- AP

adenomatous polyps

- CIMP

CpG island methylator phenotype

- CNM

corresponding normal mucosa

- COBRA

combined bisulfite restriction assay

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- LOH

loss of heterozygosity

- MSI

microsatellite instability

- NTN1

Netrin-1

- RT-PCR

reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

References

- 1.Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instability in colorectal cancers. Nature. 1997;386:623–627. doi: 10.1038/386623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goel A, Nagasaka T, Arnold CN, et al. The CpG island methylator phenotype and chromosomal instability are inversely correlated in sporadic colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:127–138. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herman JG, Umar A, Polyak K, et al. Incidence and functional consequences of hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation in colorectal carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6870–6875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rashid A, Issa JP. CpG island methylation in gastroenterologic neoplasia: a maturing field. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1578–1588. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Issa JP, Shen L, Toyota M. CIMP, at last. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1121–1124. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merlo A, Herman JG, Mao L, et al. 5’ CpG island methylation is associated with transcriptional silencing of the tumour suppressor p16/CDKN2/MTS1 in human cancers. Nat Med. 1995;1:686–692. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goel A, Li MS, Nagasaka T, et al. Association of JC virus T-antigen expression with the methylator phenotype in sporadic colorectal cancers. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1950–1961. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:988–993. doi: 10.1038/nrc1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kane MF, Loda M, Gaida GM, et al. Methylation of the hMLH1 promoter correlates with lack of expression of hMLH1 in sporadic colon tumors and mismatch repair-defective human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:808–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goel A, Arnold CN, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Characterization of sporadic colon cancer by patterns of genomic instability. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1608–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fearon ER, Cho KR, Nigro JM, et al. Identification of a chromo-some 18q gene that is altered in colorectal cancers. Science. 1990;247:49–56. doi: 10.1126/science.2294591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peltomaki P, Sistonen P, Mecklin JP, et al. Evidence supporting exclusion of the DCC gene and a portion of chromosome 18q as the locus for susceptibility to hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma in five kindreds. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4135–4140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fazeli A, Dickinson SL, Hermiston ML, et al. Phenotype of mice lacking functional Deleted in colorectal cancer (Dcc) gene. Nature. 1997;386:796–804. doi: 10.1038/386796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carethers JM, Hawn MT, Greenson JK, et al. Prognostic significance of allelic lost at chromosome 18q21 for stage II colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1188–1195. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70424-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazelin L, Bernet A, Bonod-Bidaud C, et al. Netrin-1 controls colorectal tumorigenesis by regulating apoptosis. Nature. 2004;431:80–84. doi: 10.1038/nature02788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodrigues S, WO De, Bruyneel E, et al. Opposing roles of netrin-1 and the dependence receptor DCC in cancer cell invasion, tumor growth and metastasis. Oncogene. 2007;26:5615–5625. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huerta S, Srivatsan ES, Venkatasan N, et al. Human colon cancer cells deficient in DCC produce abnormal transcripts in progression of carcinogenesis. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1884–1891. doi: 10.1023/a:1010626929411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arakawa H. Netrin-1 and its receptors in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:978–987. doi: 10.1038/nrc1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keino-Masu K, Masu M, Hinck L, et al. Deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC) encodes a netrin receptor. Cell. 1996;87:175–185. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serafini T, Colamarino SA, Leonardo ED, et al. Netrin-1 is required for commissural axon guidance in the developing vertebrate nervous system. Cell. 1996;87:1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabizadeh S, Oh J, Zhong LT, et al. Induction of apoptosis by the low-affinity NGF receptor. Science. 1993;261:345–348. doi: 10.1126/science.8332899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bredesen DE, Mehlen P, Rabizadeh S. Receptors that mediate cellular dependence. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:1031–1043. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehlen P, Fearon ER. Role of the dependence receptor DCC in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3420–3428. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehlen P, Llambi F. Role of netrin-1 and netrin-1 dependence receptors in colorectal cancers. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonardo ED, Hinck L, Masu M, et al. Vertebrate homologues of C. elegans UNC-5 are candidate netrin receptors. Nature. 1997;386:833–838. doi: 10.1038/386833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ackerman SL, Kozak LP, Przyborski SA, et al. The mouse rostral cerebellar malformation gene encodes an UNC-5-like protein. Nature. 1997;386:838–842. doi: 10.1038/386838a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiebault K, Mazelin L, Pays L, et al. The netrin-1 receptors UNC5H are putative tumor suppressors controlling cell death commitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4173–4178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0738063100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baptista MJ, O'Farrell C, Daya S, et al. Co-ordinate transcriptional regulation of dopamine synthesis genes by alpha-synuclein in human neuroblastoma cell lines. J Neurochem. 2003;85:957–968. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herman JG, Graff JR, Myohanen S, et al. Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9821–9826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiong Z, Laird PW. COBRA: a sensitive and quantitative DNA methylation assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2532–2534. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagasaka T, Sasamoto H, Notohara K, et al. Colorectal cancer with mutation in BRAF, KRAS, and wild-type with respect to both oncogenes showing different patterns of DNA methylation. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4584–4594. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yashiro M, Carethers JM, Laghi L, et al. Genetic pathways in the evolution of morphologically distinct colorectal neoplasms. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2676–2683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shibata D, Reale MA, Lavin P, et al. The DCC protein and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1727–1732. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612053352303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehlen P, Rabizadeh S, Snipas SJ, et al. The DCC gene product induces apoptosis by a mechanism requiring receptor proteolysis. Nature. 1998;395:801–804. doi: 10.1038/27441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Llambi F, Causeret F, Bloch-Gallego E, et al. Netrin-1 acts as a survival factor via its receptors UNC5H and DCC. EMBO J. 2001;20:2715–2722. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Llambi F, Lourenco FC, Gozuacik D, et al. The dependence receptor UNC5H2 mediates apoptosis through DAP-kinase. EMBO J. 2005;24:1192–1201. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams ME, Strickland P, Watanabe K, et al. UNC5H1 induces apoptosis via its juxtamembrane region through an interaction with NRAGE. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17483–17490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanikawa C, Matsuda K, Fukuda S, et al. p53RDL1 regulates p53-dependent apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:216–223. doi: 10.1038/ncb943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laiho P, Hienonen T, Karhu A, et al. Genome-wide allelotyping of 104 Finnish colorectal cancers reveals an excess of allelic imbalance in chromosome 20q in familial cases. Oncogene. 2003;22:2206–2214. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orita H, Sakamoto N, Ajioka Y, et al. Allelic loss analysis of early-stage flat-type colorectal tumors. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:43–49. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stryker SJ, Wolff BG, Culp CE, et al. Natural history of untreated colonic polyps. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:1009–1013. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90563-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eide TJ. Risk of colorectal cancer in adenoma-bearing individuals within a defined population. Int J Cancer. 1986;38:173–176. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910380205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samowitz WS, Albertsen H, Herrick J, et al. Evaluation of a large, population-based sample supports a CpG island methylator phenotype in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:837–845. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roth S, Laiho P, Salovaara R, et al. No SMAD4 hypermethylation in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:1015–1019. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ando T, Sugai T, Habano W, et al. Analysis of SMAD4/DPC4 gene alterations in multiploid colorectal carcinomas. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:708–715. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1614-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yashiro M, Laghi L, Saito K, et al. Serrated adenomas have a pattern of genetic alterations that distinguishes them from other colorectal polyps. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2253–2256. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boland CR, Sato J, Appelman HD, et al. Microallelotyping defines the sequence and tempo of allelic losses at tumour suppressor gene loci during colorectal cancer progression. Nat Med. 1995;1:902–909. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim YH, Petko Z, Dzieciatkowski S, et al. CpG island methylation of genes accumulates during the adenoma progression step of the multistep pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:781–789. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]