Background: Lactoperoxidase plays a key role in host defense by oxidizing thiocyanate to the bactericidal agent hypothiocyanite.

Results: Urate is a good substrate for lactoperoxidase and competes with thiocyanate for oxidation in vitro.

Conclusion: Urate is a likely physiological substrate for lactoperoxidase.

Significance: Urate may influence the bactericidal activity of lactoperoxidase.

Keywords: Host Defense, Kinetics, Peroxidase, Pre-steady-state Kinetics, Uric Acid

Abstract

The physiological function of urate is poorly understood. It may act as a danger signal, an antioxidant, or a substrate for heme peroxidases. Whether it reacts sufficiently rapidly with lactoperoxidase (LPO) to act as a physiological substrate remains unknown. LPO is a mammalian peroxidase that plays a key role in the innate immune defense by oxidizing thiocyanate to the bactericidal and fungicidal agent hypothiocyanite. We now demonstrate that urate is a good substrate for bovine LPO. Urate was oxidized by LPO to produce the electrophilic intermediates dehydrourate and 5-hydroxyisourate, which decayed to allantoin. In the presence of superoxide, high yields of hydroperoxides were formed by LPO and urate. Using stopped-flow spectroscopy, we determined rate constants for the reaction of urate with compound I (k1 = 1.1 × 107 m−1 s−1) and compound II (k2 = 8.5 × 103 m−1 s−1). During urate oxidation, LPO was diverted from its peroxidase cycle because hydrogen peroxide reacted with compound II to give compound III. At physiologically relevant concentrations, urate competed effectively with thiocyanate, the main substrate of LPO for oxidation, and inhibited production of hypothiocyanite. Similarly, hypothiocyanite-dependent killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa was inhibited by urate. Allantoin was present in human saliva and associated with the concentration of LPO. When hydrogen peroxide was added to saliva, oxidation of urate was dependent on its concentration and peroxidase activity. Our findings establish urate as a likely physiological substrate for LPO that will influence host defense and give rise to reactive electrophilic metabolites.

Introduction

Uric acid is an enigma in human metabolism. It accumulates in its mono-anionic form urate to produce high concentrations in cells and extracellular fluids such as lymphatic, interstitial, synovial, cerebrospinal, and respiratory tract lining fluids (1), but its precise physiological function remains unknown, although it is suggested to be an antioxidant (2–5) and a danger signal for inflammatory tissue damage (6). In contrast to other mammals, in humans urate is considered the end product of purine metabolism because the urate-catabolizing enzyme uricase has been lost during primate evolution (7, 8). High concentrations of plasma uric acid are associated with adverse outcomes in numerous inflammatory diseases (9–14), yet the mechanisms linking it to a particular pathology for the most part remain obscure. The major exception is activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by uric acid crystals in gout (15–17).

Typical urate concentrations in human serum range from 50 to 900 μm (1). Concentrations of 200–300 μm are considered normal, whereas concentrations exceeding 420 μm are regarded hyperuricemic (18). Urate is also present in the airway lining fluids at substantial concentrations (40–370 μm) and is considered to be an abundant small-molecule antioxidant in the bronchoalveolar epithelial lining fluids (19). It can act as an antioxidant because its one-electron reduction potential ((E°′ (urate•/urate) = 0.56 V) is suitably poised for urate to intercept damaging radicals but not propagate chain reactions (20). This reduction potential also makes urate a likely substrate for heme peroxidases. Indeed, it was shown early that mammalian peroxidases oxidize urate to allantoin (21, 22). Recently, kinetic studies by us revealed urate to be a physiological substrate for the neutrophil enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO)3 (23). It has also been suggested to be a substrate for the peroxidase cycle of prostaglandin synthase (24). Whether urate is an important physiological substrate for lactoperoxidase (LPO) is unknown.

LPO is a heme-containing mammalian enzyme found in exocrine secretion liquids, including saliva, tears, milk, and the lining fluids of the airway. Its main physiological function is the oxidation of thiocyanate (SCN−) to the bactericidal hypothiocyanite (−OSCN), which makes LPO an important part of the innate host defense (25–27). High concentrations of LPO are present in human airway secretions, suggesting a function of LPO in the airway host defense against respiratory diseases (28). Apart from its main substrate thiocyanate, LPO oxidizes a variety of organic substrates, such as serotonin, tyrosine, tryptophan, melatonin, tryptamine and N-acetyltryptamine (29), thioanisole (30), the antibiotic benzylpenicillin (31), and adrenaline (22). Given the promiscuity of LPO, we considered that it may also readily oxidize urate.

In this study, we raised the question as to whether urate is a likely physiological substrate for LPO and in what way this might affect the efficiency of the bactericidal activity of the enzyme. Our findings give new insights into human host defense in extracellular fluids and how they may be influenced by hyperuricemia.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Lactoperoxidase from bovine milk (purity index A412/A280 = 0.88–0.95) was purchased from Sigma (L8257) as lyophilized powder. Its concentration was determined using ϵ412 = 112,000 m−1 cm−1 (32). Initial experiments with human and bovine LPO showed near identical activity (33), and subsequent studies have used bovine LPO for kinetic studies. Myeloperoxidase was obtained from Planta (Vienna, Austria) and had a purity index of 0.82. Its concentration was determined using ϵ430 89,000 m−1 cm−1 (34). Catalase (C3155), cytochrome c (C2506), 5,5-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB, D8130), superoxide dismutase (S7571), uric acid (U2625), 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB, 860336), and xanthine oxidase (X1875) were also purchased from Sigma. To prevent artifactual oxidation of the substrate, 10 mm urate was dissolved in 40 mm sodium hydroxide containing 100 μm diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid and immediately diluted to the working concentration in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, or pH 7.0 for the kinetic studies, and stored in the dark. The concentrations of xanthine oxidase and cytochrome c were determined using ϵ450 = 70,000 m−1 cm−1 (35) and ϵ410 = 106,100 m−1 cm−1 (36), respectively. Hydrogen peroxide (30%) was purchased from BioLab, and the diluted solutions were prepared daily. The hydrogen peroxide concentration was determined by using ϵ240 = 43.6 m−1 cm−1 (37). Thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid (TNB) was prepared from 5,5-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB, Ellman's reagent) as described in Ref. 38.

Reaction of LPO with Urate and Identification of the Reaction Products by Mass Spectrometry

To identify the oxidation products, urate (400 μm) was oxidized by LPO (200 nm) and hydrogen peroxide (100 μm) in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, at 20–22 °C. Reactions were stopped after 10 min by the addition of 20 μg/ml catalase. The samples were suspended in 20% ammonium acetate buffer, pH 6.8, and 80% acetonitrile and centrifuged for 1 min at 16,000 × g. Urate, allantoin, and other intermediates were detected by liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry (LC/MS) as published previously (23). The urate oxidation products were monitored as described before but with the minor alteration of the chromatography by shortening the re-equilibration to 7 min and changing the source temperature of the mass spectrometer to 500 °C (23, 39). The [M-H]− ions that were monitored had m/z values of 167 (urate), 165 (dehydrourate), 183 (5-hydroxyisourate), and 157 (allantoin).

Urate Oxidation by LPO in the Presence of Superoxide

To investigate the formation of urate hydroperoxides by xanthine oxidase and LPO, organic hydroperoxides were detected using a ferrous oxidation-xylenol orange (FOX) assay as described previously (23, 37, 40–42). Reactions were started by adding acetaldehyde (3 mm) to LPO (150 nm) and urate (200 μm) in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4.

Spectral Changes of LPO and Rate Constant for the Reaction of Compound I and II with Urate

The kinetic experiments were performed using equipment described previously (23) in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, at 25 °C. Urate photolysis (43) was minimized by using a filter with a cut-off at 320 nm. It was previously shown that equimolar concentrations of hydrogen peroxide were required to form the maximum amount of LPO compound I (29). This was confirmed by single mixing experiments, and the maximum amount of compound I and a minimal amount of compound II were present in the reaction mixture after 100 ms (data not shown). Consequently, a delay time of 100 ms was used for the double mixing experiments to study the reaction of compound I with urate. For the reaction of compound II with urate, either a delay time of 2 s was used so that the reaction mixture contained the maximum amount of compound II when the substrate was added, or compound II was produced by reaction with urate as described above.

The rate constants of the reactions of LPO compound I and II with urate were determined as described previously for urate oxidation by myeloperoxidase (23). Final concentrations were 1 μm ferric LPO, 1 μm hydrogen peroxide, and various concentrations of urate (0–25 μm). To monitor the reaction of LPO compound I with urate, spectral changes were followed between 1 ms and 1 s, and formation of compound II was monitored at 432 nm. To establish the rate constant of the reaction of LPO compound II with urate, spectral changes were monitored between 1 ms and 200 s, and the decay of compound II back to ferric LPO was observed at 432 nm. All data were fitted by single exponential functions to determine the pseudo-first-order rate constants kobs, carried out at least in duplicate for each substrate concentration. Second-order rate constants were calculated from the slope of the linear fit when the mean values for kobs were plotted against substrate concentration.

Steady State Kinetics of the Reaction of LPO with Urate and with Thiocyanate

The steady state kinetics of urate oxidation by LPO were studied spectrophotometrically at room temperature in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. The reaction mixtures contained 500 nm LPO and 30–400 μm urate. Reactions were initiated by the addition of 100 μm hydrogen peroxide, and the velocity of urate turnover was measured at 291 nm (ϵ291 = 12,300 m−1 cm−1) using an Agilent 8453 diode array spectrophotometer. Measurements were made every 20 s to avoid urate photolysis. Additionally, the steady state kinetics of the LPO/urate system were confirmed under the same reaction conditions at 25 °C by measuring the consumption of hydrogen peroxide using a hydrogen peroxide-sensitive electrode (ISO-HPO-2 hydrogen peroxide sensor, World Precision Instruments). To investigate whether LPO is inactivated by urate, activity assays using TMB were performed as described previously (44) before and 20 min after incubation of LPO (500 nm) with urate (100 μm) and hydrogen peroxide (100 μm).

For comparison with urate turnover, the steady state kinetics of thiocyanate oxidation by LPO were studied by measuring the consumption of hydrogen peroxide at 25 °C under the same buffer and pH conditions. In addition, the amount of hypothiocyanite formed was measured spectrophotometrically by assaying the oxidation of TNB (ϵ412 = 14,100 m−1 cm−1) (38). The reaction mixtures contained 50 nm LPO, 100 μm hydrogen peroxide, 20–1000 μm potassium thiocyanate, and 100 μm TNB in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.0.

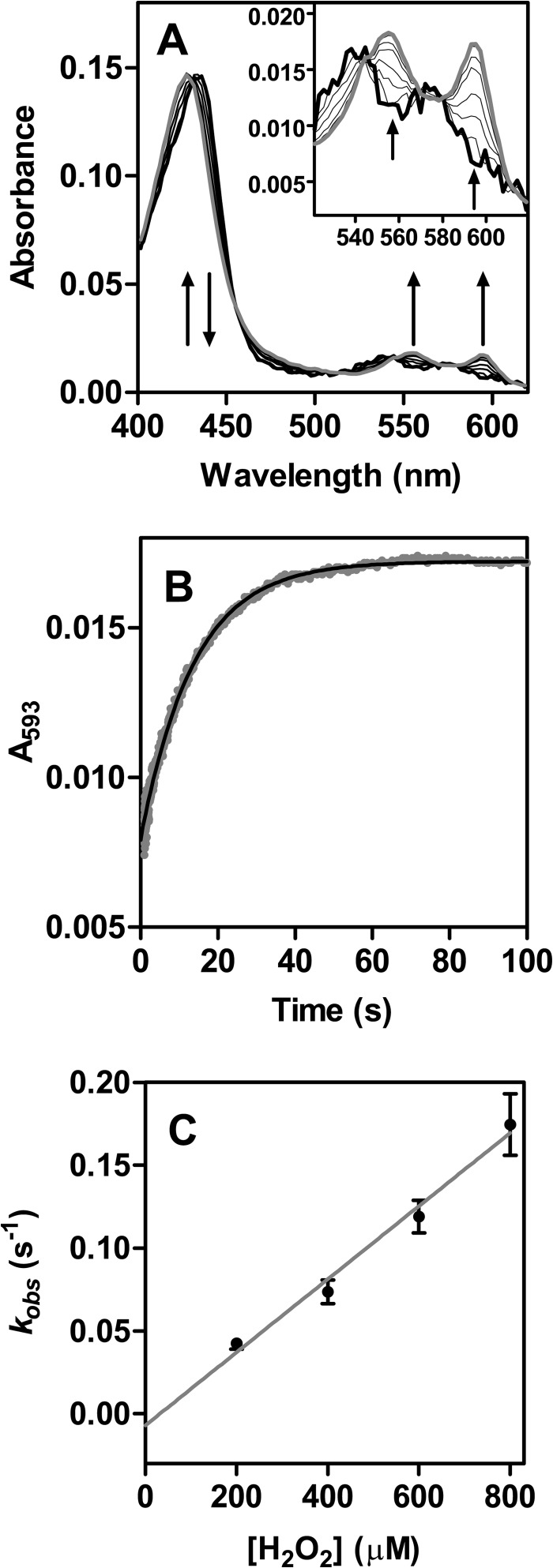

Formation of Compound III during Steady State Oxidation of Urate

To investigate the formation of LPO compound III during the steady state oxidation of urate, stopped-flow kinetic studies were performed in single mixing mode at 25 °C in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. After preincubation of LPO (2 μm final concentration) with urate (200 μm final concentration), the mixture was allowed to react with various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (200–800 μm), and formation of compound III observed at 593 nm. The data were fitted with single exponential functions to determine the pseudo-first-order rate constant kobs, which was repeated in triplicate for each hydrogen peroxide concentration. The slope of the mean values for kobs versus substrate concentration yielded the second-order rate constant for the reaction of compound II with hydrogen peroxide to form compound III.

Competition of Urate and Thiocyanate for LPO

To assess the competition between urate and thiocyanate for oxidation by LPO, the extent of urate oxidation was measured at a fixed concentration of urate and variable concentrations of thiocyanate. Allantoin was measured as a stable product of urate oxidation using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry assay (LC/MS/MS) (39). Reactions were started by adding hydrogen peroxide (20 μm) to urate (400 μm) and LPO (50 nm) in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, in the presence of various concentrations of thiocyanate (0–200 μm) at 37 °C. After 30 min, reactions were stopped by the addition of 20 μg/ml catalase. The samples were suspended in 20% ammonium acetate buffer, pH 6.8, and 80% acetonitrile and centrifuged for 1 min at 16,000 × g, and the accumulated allantoin was quantified by LC/MS. The final concentrations of the product allantoin, which depend upon the relative rates of the respective reactions, were calculated for a range of thiocyanate concentrations, and the IC50 was determined.

We also determined the competition between urate and thiocyanate by assessing the effect of urate on production of hypothiocyanite, which was quantified by measuring the conversion of GSH to GSSG. Reactions were started by adding 50 μm hydrogen peroxide to 200 μm GSH, 10 nm LPO, 100 μm thiocyanate, with or without the addition of 250 μm urate in 10 mm PBS (140 mm sodium chloride), pH 6.8. Reactions were stopped after 10 min by adding catalase (10 μg/ml). Conversion of GSH to GSSG was also measured after the addition of 2 μg/ml glucose oxidase to the above system to generate a continuous flux of hydrogen peroxide. In this case, reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. N-Ethylmaleimide (4 mm) was then added to alkylate unreacted GSH, and samples were incubated for 30 min in the dark and then stored at −20 °C until analyzed. Alkylated GSH and GSSG were analyzed by stable isotope dilution LC/MS/MS as described previously (45). Mass spectrometry analyses were performed using an Applied Biosystems 4000 QTRAP (Concord, Ontario, Canada) coupled to a Hypercarb column (150 × 2.1 mm, 3 μm, Thermo Scientific) operated at 60 °C.

Bacterial Killing Assay

We assessed the effect of urate on the bactericidal activity of LPO by measuring the hypothiocyanite-dependent killing of a clinical isolate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. For viability assays, single colonies of P. aeruginosa were cultured overnight in 3% tryptic soy broth (w/v; 37 °C; 200 rpm), harvested by centrifugation, washed, and suspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution (10 mm PBS, pH 7.4, containing 500 μm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, and 1 mg/ml glucose). Bacterial cell density was measured (A550), and cell number was calculated from a standard curve based on colony counts. Hypothiocyanite was generated by adding 50 μm hydrogen peroxide to 10 nm LPO, 100 μm SCN, with or without 250 μm urate in PBS at pH 6.8. After 10 min at 20–22 °C, the remaining hydrogen peroxide was removed by the addition of 10 μg/ml catalase. P. aeruginosa were added to these solutions at a concentration of 1 × 105/ml and incubated for 2 h with constant rotation (37 °C, 6 rpm). Samples were then diluted in PBS, pH 6.8, and plated on blood agar, and colonies were counted after overnight incubation at 37 °C. P. aeruginosa were also exposed to a continuous flux of hypothiocyanite for 1 h with constant rotation (37 °C, 6 rpm) using glucose oxidase (2 μg/ml) and 10 nm LPO in the above buffer. This system generated 1.5 μm/min hydrogen peroxide. After the addition of catalase (10 μg/ml), samples were diluted in PBS, pH 6.8, plated on blood agar, and counted after overnight incubation at 37 °C.

Analysis of Peroxidases and Urate Oxidation in Human Saliva

Ethical consent was obtained to collect saliva from healthy subjects including an individual with MPO deficiency. The content of MPO protein in isolated neutrophils from the MPO-deficient individual was 3.5% of that from a healthy donor as assessed by an MPO ELISA assay (46). This value is similar to that previously reported for this individual (47). Saliva was collected at least 2 h after donors had eaten and immediately after they had rinsed their mouths with water. The saliva was centrifuged for 25 min at 25,000 × g, and the supernatant was analyzed for its content of peroxidase activity, urate, and allantoin. Peroxidase activity in saliva was measured by monitoring the oxidation of TNB (ϵ412 = 14,100 m−1 cm−1) to DTNB in a 96-well plate (Falcon 353072) and a microplate spectrophotometer (SpectraMax 190, Molecular Devices) (38). Saliva was diluted ∼10-fold into 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 100 mm thiocyanate and 100 μm TNB, and reactions were started by adding 50 μm hydrogen peroxide. The rate of production of hypothiocyanite was compared with standard curves obtained for bovine LPO and human MPO. Additionally, MPO concentrations in the saliva samples were measured using an activity ELISA as published previously (48). The concentration of LPO activity was then calculated by subtracting MPO activity from total peroxidase activity and expressed as bovine LPO equivalents. The concentrations of urate and allantoin in saliva supernatants were measured by mass spectrometry as described above. In a parallel experiment, hydrogen peroxide (50 μm) was added to the saliva samples and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in the absence or presence of 1 mm sodium azide. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 10 μg/ml catalase, and the changes in allantoin concentrations were measured using liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between treatment groups were determined using ANOVA followed by Holm-S̊ídák post hoc analysis. Differences from the control were considered significant when p < 0.05. Associations were analyzed using Pearson's correlation coefficient and considered significant when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Reaction of LPO with Urate and Identification of the Reaction Products by Mass Spectrometry

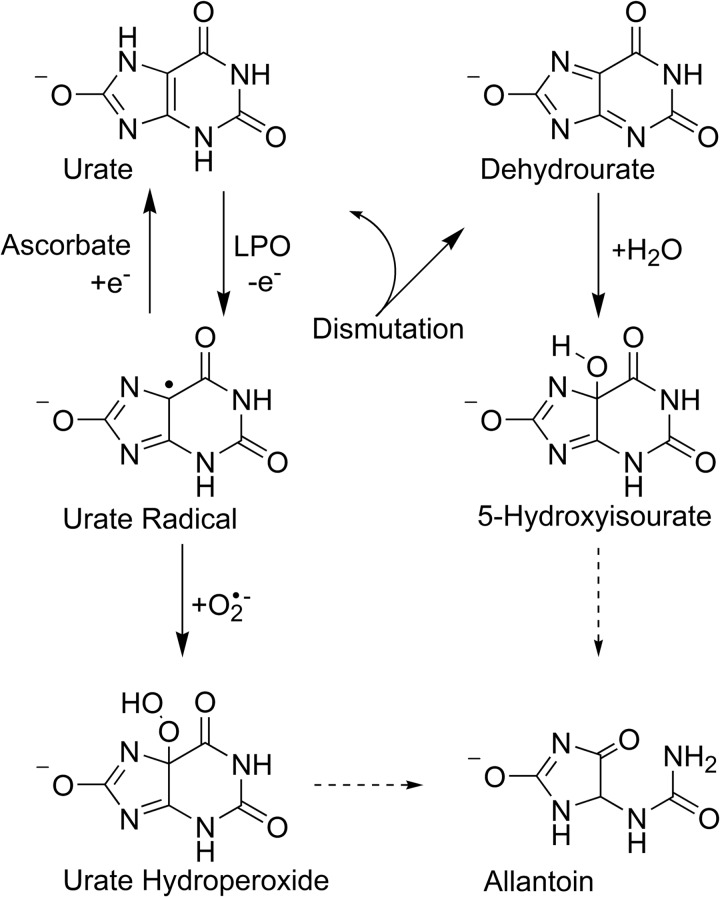

Oxidation of urate by LPO and hydrogen peroxide was demonstrated by showing a decrease in absorbance at 290 nm and a corresponding increase at 315 nm due to formation of products as reported previously for MPO (23). Urate is known to readily photolyze (49), so precautions were made to minimize this by utilizing reduced light intensity. Under these conditions, in the absence of either LPO or hydrogen peroxide, no spectral changes were detected. The maximum initial rate of oxidation of urate by LPO occurred between pH 6 and 7, whereas an increase to pH 8 decreased the rate of urate oxidation (data not shown). LC/MS analysis of the reaction mixture revealed allantoin (m/z = 157) as the major stable reaction product, whereas dehydrourate (m/z = 165) and 5-hydroxyisourate (m/z = 183) were identified as reaction intermediates (data not shown). In the absence of either hydrogen peroxide or LPO, only minor quantities of the reaction products were detected, which correspond to a minimal amount of substrate degradation by UV light as well as auto-oxidation. These results confirm that urate is a substrate for LPO and is oxidized to electrophilic species that break down to allantoin (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Potential reaction pathways for urate radicals that are formed when urate is oxidized by LPO. Dehydrourate, 5-hydroxyisourate, and allantoin were detected directly by mass spectrometry. The structure of urate hydroperoxide is a proposal only. Straight arrows represent direct reactions, and dashed arrows represent breakdown pathways.

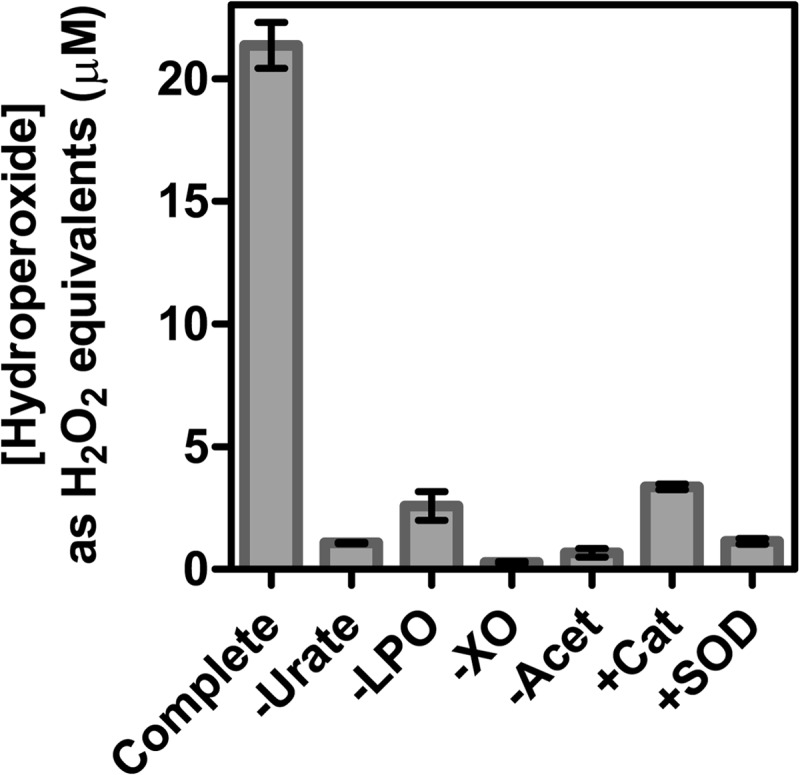

Urate Oxidation by LPO in the Presence of Superoxide

Previously, it was shown that when MPO oxidizes urate in the presence of superoxide, a hydroperoxide is formed by the addition of superoxide to the urate radical (23). To determine how effective LPO is at producing urate hydroperoxide, urate was oxidized by LPO in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide generated by xanthine oxidase and acetaldehyde. Hydroperoxides were quantified using the FOX assay, which is based on the oxidation of ferrous iron in the presence of xylenol orange (42). Considerable concentrations of hydroperoxides were formed by this system (Fig. 2), substantially more (∼3-fold) than previously observed with MPO under similar conditions (23). When one of urate, LPO, xanthine oxidase, or acetaldehyde was omitted, hydroperoxide formation was prevented. The addition of catalase decreased hydroperoxide production to almost control levels, indicating a requirement for hydrogen peroxide. The addition of superoxide dismutase decreased hydroperoxide production to control levels, demonstrating that hydroperoxide formation was reliant on superoxide. Hence, LPO uses hydrogen peroxide and superoxide to oxidize urate to a hydroperoxide.

FIGURE 2.

Formation of hydroperoxides during oxidation of urate by LPO in the presence of superoxide. For the complete system, urate (200 μm) was incubated with LPO (150 nm) and xanthine oxidase (XO, 200 nm) in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Reactions were started by the addition of acetaldehyde (Acet, 3 mm) to produce a superoxide flux of 6 μm/min and stopped after 30 min by adding catalase (100 μg/ml). Hydroperoxides were quantified by the FOX assay and were expressed as hydrogen peroxide equivalents. When added to the reaction system, catalase (Cat) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were present at 100 and 20 μg/ml, respectively. Data are means and ranges of at least duplicate experiments.

Spectral Changes of LPO and Rate Constant for the Reaction of Compound I and II with Urate

The rate constants for the reactions of urate with compound I and II were determined by stopped-flow kinetic studies. To determine the ideal delay times for the sequential mixing experiments, a single mixing experiment was performed where hydrogen peroxide was added to ferric LPO. Upon the addition of hydrogen peroxide to LPO, a decrease of absorbance was observed at 412 nm, which corresponds to the formation of compound I. The maximum concentration of compound I was found at 100 ms, which was therefore used as the delay time. After 100 ms, an absorbance shift from 412 nm to 432 nm was monitored and was completed in 2 s. These spectral changes indicate the conversion of compound I to II. In the absence of substrate, the absorbance of compound II at 432 nm remained stable for 10 s and decayed very slowly afterward.

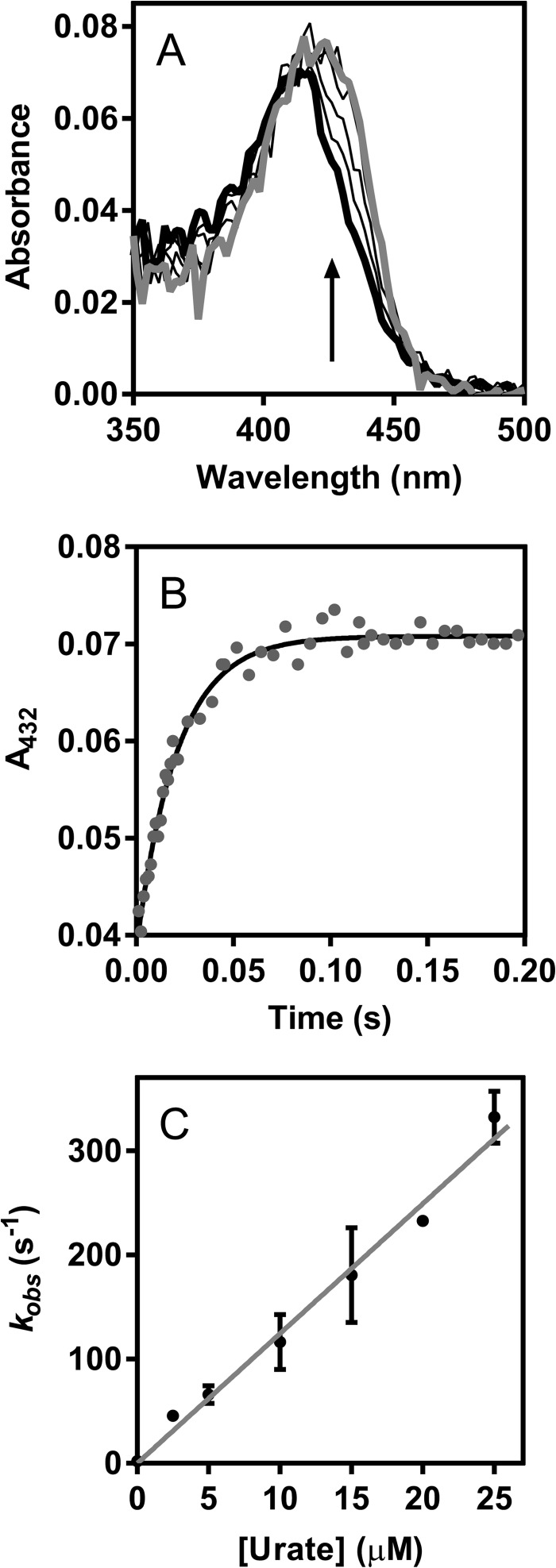

To determine the rate constant of the reaction of compound I with urate, ferric LPO was allowed to react with hydrogen peroxide for 100 ms followed by the addition of urate (0–25 μm) to reduce compound I. Spectral changes showed a rapid conversion of compound I (λmax = 412 nm) to compound II (λmax = 432 nm) over 50 ms (Fig. 3A). Kinetic traces were monitored at 432 nm to follow compound II formation for each substrate concentration and fitted with single exponential functions (Fig. 3B). The observed pseudo-first-order rate constants kobs of compound II formation were linearly dependent on substrate concentration (Fig. 3C). The line of best fit had a slope of (1.1 ± 0.1) × 107 m−1 s−1, which corresponds to the second-order rate constant of the reaction of LPO compound I with urate.

FIGURE 3.

Determination of the rate constant for the reaction of LPO compound I with urate. LPO (1 μm) was premixed with hydrogen peroxide (1 μm) to form compound I at 25 °C in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. After a delay time of 100 ms, urate was added (0–25 μm). All solutions were prepared freshly and kept in the dark to avoid photolysis. A, spectral changes after the addition of urate (2.5 μm) followed between 3 ms (thick black line) and 200 ms (gray line); only representative spectra are shown. B, formation of compound II in A was monitored at 432 nm (gray dots), and the data were fitted by single exponential functions (black line). C, the averaged observed rate constants kobs were plotted against the concentration of urate (black dots). Data are means and standard deviations of at least triplicate measurements. The slope of the linear fit corresponds to the second-order rate constant of the reaction of LPO compound I with urate.

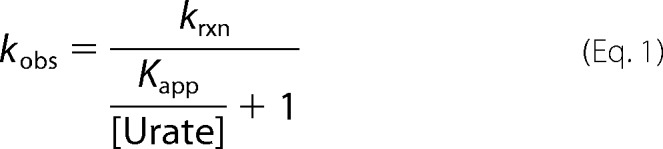

Previously, it was suggested that compound I of LPO can isomerize so that the porphyrin radical is transferred to an amino acid residue and that this species is spectrally identical to compound II (50). Therefore, a species with spectral characteristics of compound II was formed either through decay of compound I by increasing the delay time to 2 s or by reduction of compound I by urate as described above. The former method could give isomerized compound I or authentic compound II, whereas the second method would give authentic compound II only. In both cases, upon the addition of urate (0–200 μm) to compound II, spectral changes revealed its conversion (λmax = 432 nm) back to the ferric enzyme (λmax = 412 nm) over 60 s, as well as an isosbestic point at 423 nm (Fig. 4A). Kinetic traces were monitored at 432 nm to follow the reduction of compound II and were fitted with single exponential functions (Fig. 4B). The observed pseudo-first-order rate constants kobs were independent of the method in which compound II was formed and revealed a linear dependence on substrate concentration for up to 30 μm urate (Fig. 4C). The line of best fit had a slope of (8.5 ± 0.4) × 103 m−1 s−1, which represents the second-order rate constant of the reaction of LPO compound II with urate. The intercept of the fitted line with the y axis was 0.015 ± 0.006 s−1 and corresponds to the spontaneous decay of compound II. These results suggest that LPO has only one form of compound II as previously argued (51). Upon increasing urate concentrations to 200 μm, the plot of the observed pseudo-first-order rate constants kobs versus urate concentration for the reaction of compound II with urate plateaus (Fig. 4D), indicating a binding interaction between compound II and urate, which can be described as follows (52–54).

|

As a result, kobs versus urate concentration can be fitted to a rectangular hyperbola, according to the following equation.

|

where

|

The value for the apparent dissociation constant Kapp = (200 ± 30) μm was directly derived from the nonlinear fit shown in Fig. 4D. We would expect a similar plot of kobs versus urate concentration to level off at high urate concentrations for the reaction of compound I with urate. Unfortunately, we were not able to measure these rate constants because of the high reactivity of compound I toward urate, leading to rates that are beyond the detection limit of the instrument at high urate concentrations.

FIGURE 4.

Determination of the rate constant for the reaction of LPO compound II with urate. LPO (1 μm) was premixed with hydrogen peroxide (1 μm) to form compound I at 25 °C in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. After a delay time of 100 ms or 2 s, urate was added (0–200 μm). A, spectral changes after the addition of urate (10 μm) followed between 1 ms (thick black line) and 80 s (gray line); only representative spectra are shown (2-s delay time). B, reduction of compound II in A was monitored at 432 nm (gray dots), and the data were fitted to a single exponential function (black line). C, the averaged observed rate constants kobs were plotted against the concentration of urate (black dots). Data are means and ranges of at least duplicate measurements. The slope of the linear fit corresponds to the second-order rate constant of the reaction of LPO compound II with urate. D, the plot of averaged observed rate constants versus urate concentration levels off at high urate concentration. Data are means and ranges of duplicate experiments (black dots) and were fitted to a rectangular hyperbola (gray line) using Equation 1.

Steady State Kinetics of the Reaction of LPO with Urate and with Thiocyanate

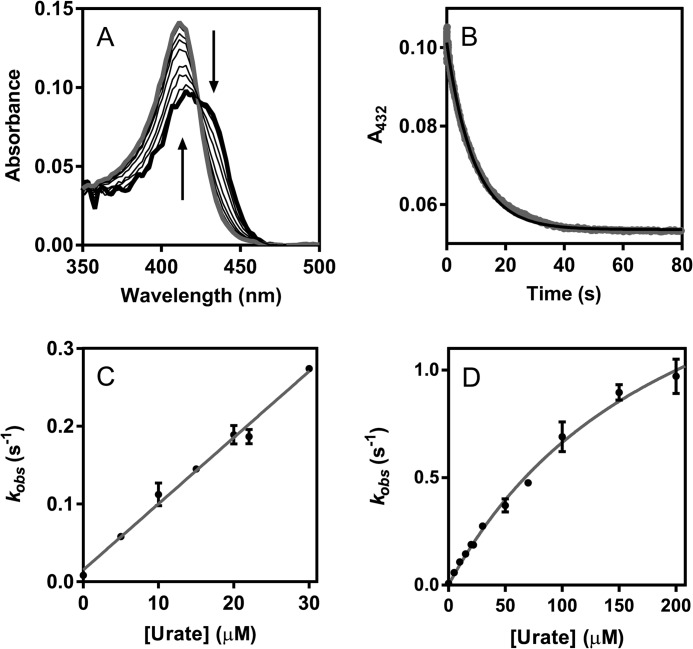

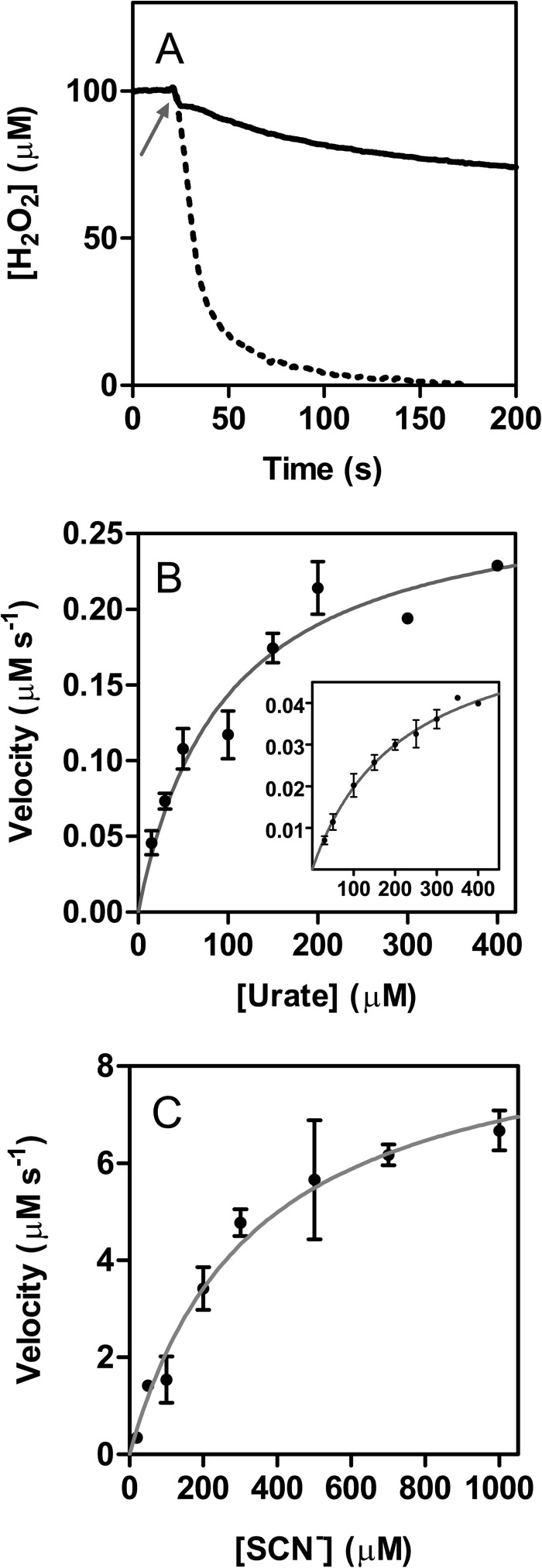

To understand how urate and thiocyanate may compete as substrates for LPO, the steady state kinetics of their oxidation by the enzyme were studied and compared. Hydrogen peroxide consumption was measured for both substrates using a hydrogen peroxide-sensitive electrode (Fig. 5A). Additionally, urate oxidation was followed directly at 291 nm, and the formation of hypothiocyanite was monitored by recording its oxidation of TNB. The Michaelis-Menten curves are shown in Fig. 5, B and C, and the kinetic parameters, which were independent of the methods used to measure them, are listed in Table 1. These parameters reveal that thiocyanate is preferred to urate as a substrate for LPO but suggest that, depending on relative concentrations, the two substrates should compete for oxidation by the enzyme. The kinetic traces of urate oxidation were characterized by an initial phase of fast urate depletion followed by a slower second phase. To investigate whether the slow phase was due to irreversible enzyme inhibition, activity assays using TMB were performed before and after reaction of LPO with urate. No change in peroxidase activity occurred after reaction with hydrogen peroxide and urate (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Steady state oxidation of urate and thiocyanate by LPO. A, loss of hydrogen peroxide during thiocyanate (dotted line) and urate (solid line) oxidation by LPO measured continuously using a hydrogen peroxide specific electrode. Reaction mixtures contained 100 μm hydrogen peroxide, 50 nm LPO, and 1 mm thiocyanate or 100 μm hydrogen peroxide, 500 nm LPO, and 300 μm urate, respectively, in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, at 25 °C. Arrow indicates when LPO was added. B, initial phase of urate degradation was monitored at 291 nm except at high urate concentrations (>200 μm), when it was followed by recording hydrogen peroxide depletion. Inset shows data obtained for the secondary phase. Reaction mixtures contained 500 nm LPO, 100 μm hydrogen peroxide, and 30–400 μm urate. The velocities were plotted against substrate concentration (black dots) and were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation (gray lines). C, oxidation of thiocyanate by LPO was monitored by measuring the loss of hydrogen peroxide. Reaction mixtures contained 50 nm LPO, 100 μm hydrogen peroxide, and 20–1000 μm thiocyanate. The velocities were verified by following the oxidation of TNB by hypothiocyanite at 412 nm. These experiments were performed under the same reaction conditions with 100 μm TNB added to the reaction mixture. Data are means and standard deviations of at least triplicate experiments.

TABLE 1.

Steady state kinetic parameters for the oxidation of urate and thiocyanate by LPO

Km and Vmax were determined by fitting the kinetic data in Fig. 5 according to Michaelis-Menten kinetics. The catalytic rate constant kcat was calculated by dividing Vmax by the concentration of LPO heme. The specificity constant kx− was calculated by dividing kcat by Km.

| LPO + urate (initial phase) | LPO + urate (secondary phase) | LPO + SCN− | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Km (μm) | 100 ± 20 | 220 ± 30 | 340 ± 60 |

| kcat (s−1) | 0.56 ± 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 180 ± 20 |

| kx− (m−1 s−1) | 5.6 × 103 | 580 | 5.5 × 105 |

Formation of Compound III during Steady State Oxidation of Urate

To understand why urate oxidation by LPO was characterized by an initial fast phase, we monitored the enzyme spectrally and observed that it was present as compound III during the steady state of urate turnover by LPO (Fig. 6A). When LPO and urate were allowed to react with various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide, spectral changes revealed a conversion of compound II (λSoret = 432 nm, λβ = 542 nm, λα = 574 nm) to compound III (λSoret = 428 nm, λβ = 555 nm, λα = 593 nm) over 60 s, as well as an isosbestic point at 431 nm (Fig. 6A). Kinetic traces were monitored at 593 nm and fitted with single exponential functions for each hydrogen peroxide concentration (Fig. 6B). The observed pseudo-first-order rate constants kobs of compound III formation were linearly dependent on the concentration of hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 6C), and the linear fit had a slope of (220 ± 15) M−1 s−1. This value corresponds to the second-order rate constant of the reaction of LPO compound II with hydrogen peroxide to form compound III (55). The intercept of the fitted line with the y axis was −0.007 ± 0.008 s−1. The fact that the fitted line intercepts the origin strongly suggests that compound III is formed only by the reaction of compound II with hydrogen peroxide.

FIGURE 6.

Determination of the rate constant for the reaction of LPO compound II with hydrogen peroxide to form compound III. LPO (2 μm) was preincubated with urate (400 μm) and then allowed to react with various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (200–800 μm) at 25 °C in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. A, representative spectral changes followed between 5 ms (thick black line) and 80 s (gray line) using 200 μm H2O2. Inset shows the α and β bands in greater detail. B, the formation of compound III was monitored at 593 nm (gray dots), and the data were fitted by single exponential functions (black line); representative data were obtained using 200 μm H2O2. C, the averaged observed rate constants kobs were plotted against the concentration of hydrogen peroxide (black dots). Data are means and standard deviations of triplicate measurements. The slope of the linear fit corresponds to the second-order rate constant of the reaction of LPO compound II with hydrogen peroxide to form compound III.

Urate and Thiocyanate as Competing Substrates for LPO

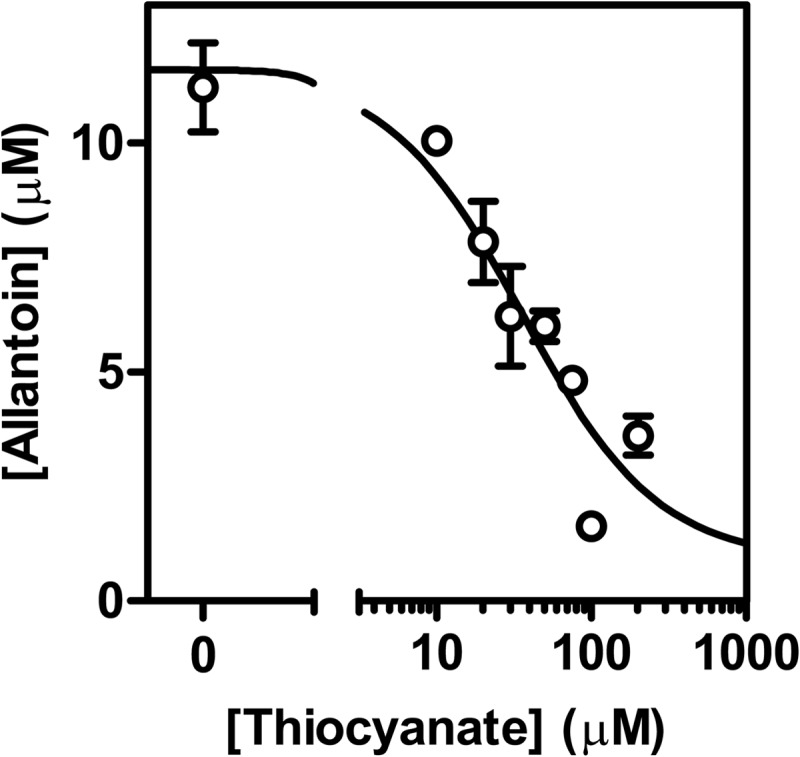

Next we investigated the direct competition between urate and thiocyanate for oxidation by LPO. First, we determined the effect of thiocyanate on urate oxidation by measuring its ability to inhibit the accumulation of allantoin. Reactions were allowed to proceed long enough so that all the hydrogen peroxide was used by LPO. In the absence of thiocyanate, about half the hydrogen peroxide was accounted for by the accumulation of allantoin. Thiocyanate inhibited the extent of allantoin formation in a concentration-dependent manner. It inhibited by 50% at a concentration of 36 μm (IC50) when 400 μm urate and 20 μm hydrogen peroxide were present in the reaction mixture (Fig. 7). The obtained IC50 was confirmed assuming only direct competition between thiocyanate and urate with compound I and using the respective rate constants (kSCN = 2.0 × 108 m−1 s−1; kurate = 1.1 × 107 m−1 s−1). These values yield a calculated IC50 of 24 μm.

FIGURE 7.

Thiocyanate and urate compete as substrates for LPO. LPO (50 nm) was incubated with urate (400 μm) and various concentrations of thiocyanate (0–200 μm) in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Reactions were started by the addition of hydrogen peroxide (20 μm) and stopped by the addition of 20 μg/ml catalase. Allantoin formation was measured by LC/MS. The concentration of thiocyanate, when allantoin formation is inhibited by 50% (IC50), was determined by fitting the data as described under “Experimental Procedures” (solid line). Data are means and ranges of duplicate experiments.

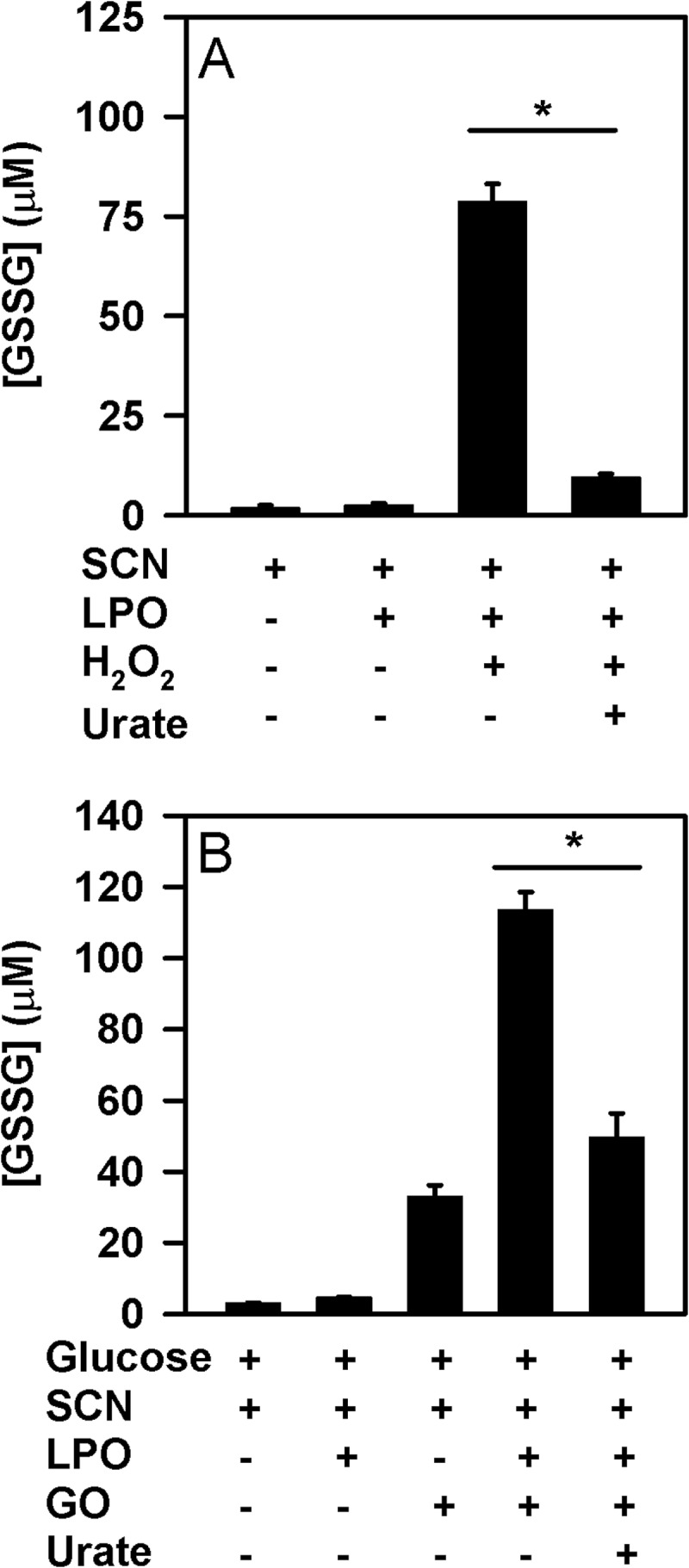

To confirm the influence of urate on the capability of LPO to oxidize thiocyanate, the production of hypothiocyanite by LPO was measured by detecting the oxidation of GSH to GSSG in the absence and presence of urate. Reactions were run for sufficient time so that the LPO/thiocyanate system could just consume all added hydrogen peroxide. In the absence of urate, LPO used hydrogen peroxide and thiocyanate to produce super-stoichiometric concentrations of GSSG (Fig. 8A). This result is in accord with the formation of a radical intermediate of thiocyanate by peroxidases under similar reaction conditions (56, 57). In the presence of urate, hypothiocyanite production was substantially decreased when a bolus of hydrogen peroxide was added (Fig. 8A), confirming that urate is capable of competing with thiocyanate for oxidation. When glucose oxidase was used to generate a flux of hydrogen peroxide and ensure a low steady state concentration of this substrate, urate also inhibited the production of hypothiocyanite (Fig. 8B). In both cases, urate inhibited considerably more than the 10% that would be expected if it was acting only by competing with thiocyanate for oxidation by compound I. Thus, urate inhibits production of hypothiocyanite via a pathway in addition to its reaction with compound I.

FIGURE 8.

Effect of urate on LPO-mediated production of hypothiocyanite. The formation of hypothiocyanite by LPO was measured as oxidation of GSH to GSSG. A, hypothiocyanite was generated by the addition of 50 μm H2O2 to 10 nm LPO and 100 μm thiocyanate in the presence or absence of 250 μm urate in 10 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.8. After a 10-min incubation at room temperature, 10 μg/ml catalase was added followed by N-ethylmaleimide. Data are means and standard deviations of five individual experiments. B, hypothiocyanite was produced over 1 h at 37 °C by incubation of 2 μg/ml glucose oxidase (GO) with 10 nm LPO, 100 μm thiocyanate, and 200 μm GSH in the presence or absence of 250 μm urate in 10 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.8. Reactions were stopped by adding catalase (20 μg/ml), and then unreacted GSH was alkylated with 4 mm N-ethylmaleimide. Data are means and standard deviations for a representative experiment of 3–4 separate experiments. Data were analyzed by ANOVA using Holm-S̊ídák post hoc analysis. *, p < 0.05 for comparisons versus the complete reaction system.

Inhibition of LPO-dependent Bacterial Killing by Urate

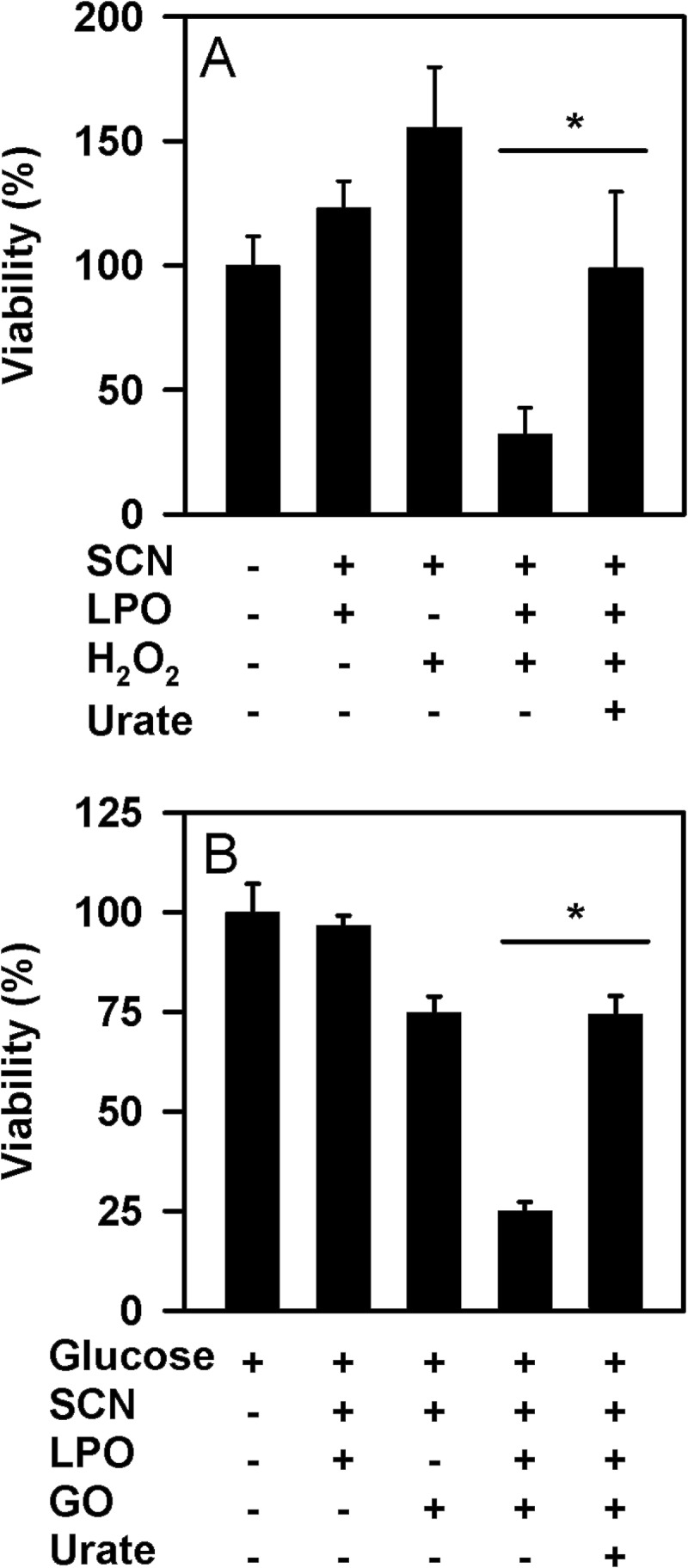

To investigate whether urate affects the ability of LPO to kill pathogenic bacteria, we determined the extent to which it prevented killing of P. aeruginosa by LPO, thiocyanate, and hydrogen peroxide. Under the conditions of our assay, LPO promoted substantial killing of P. aeruginosa in the presence of thiocyanate and hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 9A). A similar degree of killing was observed when hydrogen peroxide was supplied slowly by glucose oxidase (Fig. 9B). In both cases, killing was reliant on the presence of LPO, thiocyanate, and hydrogen peroxide. Urate, at normal physiological concentrations (1, 19), inhibited killing either in the presence of a bolus of hydrogen peroxide or when it was generated as a slow flux. These results suggest that at physiologically likely concentrations of both urate and thiocyanate, urate will interfere with the hypothiocyanite-dependent killing of bacteria by LPO.

FIGURE 9.

Effect of urate on killing of P. aeruginosa by LPO. A, hypothiocyanite was generated by the addition of 50 μm hydrogen peroxide to 10 nm LPO and 100 μm thiocyanate in the presence or absence of 250 μm urate in 10 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.8. After a 10-min incubation at room temperature, catalase (10 μg/ml) was added to remove residual hydrogen peroxide. Bacteria (1 × 105/ml) were then added and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with gentle rotation. B, P. aeruginosa were incubated for 1 h (37 °C, 6 rpm) with 2 μg/ml glucose oxidase, 10 nm LPO, and 100 μm thiocyanate in the presence or absence of 250 μm urate in 10 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.8, containing 1 mg/ml glucose. This system generated ∼1.5 μm hydrogen peroxide/min. Catalase (10 μg/ml) was added prior to dilution and plating. Data are means and standard errors of 3–4 separate experiments. Data were analyzed by ANOVA using Holm-S̊ídák post hoc analysis. *, p < 0.05 for comparisons versus the complete reaction system.

Peroxidase Levels and Urate Oxidation in Human Saliva

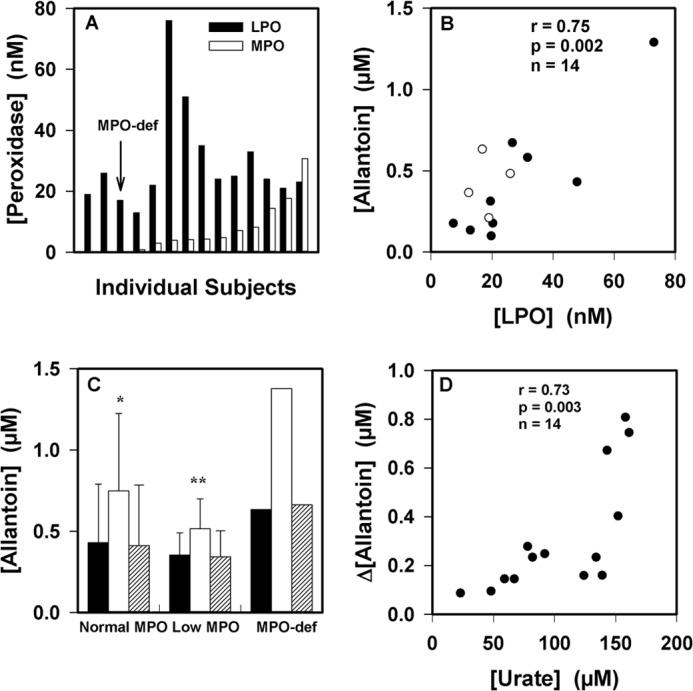

To establish the physiological importance of urate oxidation by LPO, we measured urate oxidation in human saliva. Previously, it was demonstrated that saliva supernatants contain predominantly LPO with variable concentrations of MPO. No other proteins with peroxidase activity were detected, including eosinophil peroxidase (58). All our subjects had detectable concentrations of LPO activity in saliva supernatants in agreement with previous studies (Fig. 10A) (58, 59). Four subjects, including one with MPO deficiency, had very low levels of detectable MPO activity. Allantoin was present in saliva supernatants and was associated with the activity of LPO (r = 0.77; p = 0.001) (Fig. 10B) but not MPO (not shown). When hydrogen peroxide was added to saliva supernatants, there was a significant increase in allantoin that did not occur in the presence of azide, a peroxidase poison (Fig. 10C). The concentration of allantoin increased in all samples, including those from individuals with low MPO and that from a person with MPO deficiency. The increase in allantoin concentration upon the addition of hydrogen peroxide to the saliva was dependent on its concentration of urate (r = 0.73; p = 0.003) (Fig. 10D) but not the concentrations of peroxidases (not shown). Collectively, these results suggest that the LPO present in saliva promotes the oxidation of urate.

FIGURE 10.

Urate oxidation by peroxidases in human saliva. A, LPO and MPO activities were measured in diluted saliva supernatants from 14 healthy donors. B, the allantoin concentration in saliva supernatants was related to the concentration of LPO. Clear circles are for the individuals with low or no MPO activity. The association between parameters was determined using Pearson's correlation. C, allantoin formation was measured in saliva supernatants after incubation for 30 min at 37 °C with no additions (black bars), with added hydrogen peroxide (50 μm, white bars), and with added hydrogen peroxide and azide (1 mm, respectively, striped bars). Reactions were stopped by the addition of catalase (10 μg/ml). Significant differences (p < 0.05) from the control with no added hydrogen peroxide were determined using repeated measures ANOVA. Data are means and ranges of at least duplicate experiments. MPO-def, MPO-deficient. D, initial urate concentrations in saliva supernatants were compared with the increase in allantoin concentration formed by the addition of hydrogen peroxide (50 μm) as in C. The association between parameters was determined using Pearson's correlation.

DISCUSSION

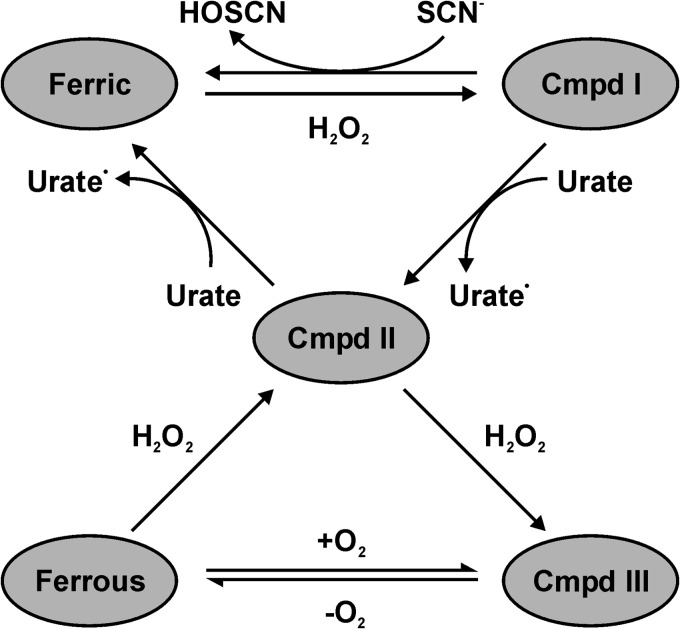

In this investigation, we have shown that urate is an excellent substrate for compound I of LPO as part of the classical peroxidase cycle and can therefore be expected to be a physiological substrate for the enzyme. Urate also reacts well with compound II, but this reaction is in competition with the conversion of compound II to compound III by hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 11). Based on our current findings and the demonstration that urate is a substrate for MPO, urate should now be recognized as a peroxidase substrate that will influence the activity of these enzymes and give rise to potentially toxic electrophiles. Urate should not be considered as simply the final inert product of purine metabolism. The precise effect urate has on production of hypothiocyanite and the bactericidal activity of LPO will depend on the relative concentrations of urate and thiocyanate as well as the local concentration of hydrogen peroxide.

FIGURE 11.

Suggested catalytic mechanism of LPO in an environment where similar concentrations of thiocyanate and urate are present. At low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide, urate will compete with thiocyanate for reaction with compound I (Cmpd I). Which substrate dominates will depend on their relative local concentrations. Urate will also ensure that LPO is not trapped at compound II (Cmpd II), thereby ensuring continual oxidant production by the enzyme. At high concentrations of hydrogen peroxide, LPO will be converted compound III (Cmpd III), whereas its conversion back to compound II relies on its slow release of oxygen (55). Under these conditions, the bactericidal activity of LPO will be inhibited.

As described previously for other peroxidases, the urate radicals produced by LPO will give rise to dehydrourate, 5-hydroxyisourate, and allantoin as outlined in Fig. 1 (23, 60). Dehydrourate and 5-hydroxyisourate are electrophilic species that are potentially toxic and are likely to affect host defense as well as the inflammatory response to bacteria. The absence of 5-hydroxyisourate hydrolase in knock-out mice predisposes them to liver cancer (61), which demonstrates that these electrophiles are indeed toxic. In the presence of superoxide, we have shown that LPO catalyzes the production of another electrophile, urate hydroperoxide. The suggested structure and formation of urate hydroperoxide via the addition of superoxide to the urate radical are shown in Fig. 1. We would expect urate hydroperoxides to make additional contributions to oxidative stress and propagate the toxicity of superoxide (62). However, in a physiological environment, antioxidants such as ascorbate may interfere by reducing urate radicals and limiting the formation of the electrophilic species of urate. The effects of ascorbate on the LPO/urate system will be the subject of future studies.

Stopped-flow kinetics showed that the rate constant for urate oxidation by compound I (1.1 × 107 m−1 s−1) is the largest for any organic substrate of LPO studied to date (29). It is 5-fold greater than that for serotonin (E°′ (serotonin•/serotonin) = 0.65 V), the next best organic substrate, and similar to that for nitrite (2 × 107 m−1 s−1) (63). The low reduction potential of urate (E°′ (urate•/urate) = 0.56 V) (20) should facilitate its oxidation by compound I. Additionally, its negative charge, like that of nitrite (E°′ (NO2·/NO2−) = 0.99 V), may also assist its binding in the active site and subsequent oxidation. Indeed, the rate constant for oxidation of urate by compound I of LPO is markedly greater than that for compound I of MPO (4.6 × 105 m−1 s−1) (23), although the redox potential of the compound I/compound II couple is higher for MPO than LPO (1.35 versus 1.14 V) (51). The stereochemical characteristics of the substrate binding site in LPO are responsible for the favorable orientation of thiocyanate, when compared with MPO, and may therefore also favor binding and subsequent oxidation of urate (64).

The rate constant for reduction of compound II by urate (8.5 × 103 m−1 s−1) was derived by fitting the linear portion of the plot of the observed rate constants versus urate concentration. Its magnitude is comparable with that for other organic substrates of LPO but substantially less than that for serotonin (3.0 × 105 m−1 s−1) (29), suggesting that negative charge and reduction potential have less influence on oxidation of substrates by this redox intermediate. Rather binding to the active site may be the crucial factor in substrate oxidation, which is supported by fact that the plot of the observed rate constants versus urate concentration plateaus for this reaction at high urate concentrations. The rate constant for oxidation by compound II is also comparable with that for MPO (1.7 × 104 m−1 s−1) (23). In this case, the compound II/ferric couples for MPO and LPO are similar (0.97 versus 1.04 V) (65). The similarity of the kinetic and thermodynamic parameters suggests that urate occupies a similar position in the compound II forms of these peroxidases. The apparent dissociation constant (200 μm) for urate binding to LPO compound II is comparable with the Michaelis-Menten constant (100 μm) we found during steady state turnover of urate, suggesting that the binding interaction of urate and compound II represents the rate-determining step in the reduction of compound II.

LPO has previously been described as capable of producing two forms of compound I and II (50, 66), where the electron hole is stored either as a radical cation on the porphyrin ring or as an amino acid-based radical, depending on the pH. However, we found that regardless of whether the compound II species was formed by slow decay of compound I or fast reduction by urate, it reacted at the same rate with urate to form ferric LPO. Consequently, we have no evidence for more than one species of compound II under our experimental conditions.

Steady state kinetic studies of LPO oxidation of thiocyanate provided constants that are comparable with those that have been determined previously for thiocyanate turnover by both myeloperoxidase and eosinophil peroxidase (56, 67). However, they reveal major discrepancies when compared with the values previously published for thiocyanate oxidation by LPO (68). These discrepancies are most likely due to differences in experimental conditions; the previous study was conducted at pH 5.5 and at hydrogen peroxide concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 1 mm. The experiments presented here were carried out at neutral pH and with comparably low hydrogen peroxide concentrations (100 μm). We believe that our experimental conditions represent more closely the physiological environment, and at the same time minimize undesired irreversible inhibition of the enzyme.

The steady state oxidation of urate by LPO was characterized by biphasic kinetics with an initial fast phase followed by a slower second phase. Activity assays showed that LPO was not irreversibly inhibited by urate or by its oxidation products. Spectroscopic studies suggest that the initial fast phase represents urate turnover during the classical peroxidase cycle, whereas the subsequent slower phase represents a second turnover cycle, where the enzyme rapidly converts to compound III and subsequently reverts to compound II at a slower rate (Fig. 11). An analogous mechanism has previously been demonstrated for oxidation of nitrite and 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) by LPO (63). Using stopped-flow spectroscopy, we were able to show that compound III is formed during the steady state of urate oxidation, and its formation was linearly dependent on hydrogen peroxide concentration. This plot intersected the origin, which excludes the possibility that compound III is formed either reversibly or via a second route, e.g. by the addition of superoxide to the native enzyme or by reduction of the ferric enzyme and subsequent to the addition of dioxygen. Consequently, urate and hydrogen peroxide compete for reaction with compound II under multiple turnover conditions with the eventual conversion of the enzyme to compound III.

The Michaelis-Menten parameters of urate turnover during the initial steady state phase (Table 1) reflect the capability of urate to compete effectively with thiocyanate for oxidation. However, on the longer time scale, it was apparent that inhibition of hypothiocyanite production cannot be simply explained by urate and thiocyanate acting as competitive substrates for compound I. Instead, reaction of hydrogen peroxide with compound II and diversion of the enzyme away from the halogenation cycle must be invoked to clarify the mechanism of inhibition. Thus, it appears that the slower second cycle is integral in describing modulation of LPO activity. This reaction has important consequences because we found that under physiologically plausible conditions, urate inhibited LPO-dependent killing of P. aeruginosa by preventing the enzyme from producing hypothiocyanite.

Our work on human saliva supports the proposal that urate is a physiological substrate for LPO. In agreement with previous studies, we found that LPO was the dominant peroxidase in saliva supernatants, and there were also variable concentrations of MPO present (25, 58). LPO, but not MPO content, was correlated with allantoin in saliva. Ex vivo experiments demonstrated that peroxidase activity was required for oxidation of urate in saliva supernatants and was dependent on the urate concentration. Given the fact that urate was oxidized in saliva with low MPO, including that from an individual with MPO deficiency, it is apparent that LPO contributes to the production of allantoin in saliva. The degree of urate oxidation was reliant on urate concentration, which is expected because saliva contains high concentrations of thiocyanate (0.5–2 mm) (25). Hence, the higher the concentration of urate, the more likely it would compete with thiocyanate for oxidation by compound I of LPO. It is conceivable that other proteins in saliva contain pseudo-peroxidase activity. However, previous work established that LPO and MPO were by far the dominant peroxidases in saliva supernatants (25, 58). Consequently, any pseudo-peroxidase activity would not compete with much higher concentrations of LPO, especially because urate is an excellent substrate for this enzyme.

Exactly how urate affects LPO activity in vivo will depend on the relative concentrations of urate and thiocyanate as well as the steady state concentration of hydrogen peroxide. From this work, it is apparent that the major determinant of LPO activity in vivo will be the local flux of hydrogen peroxide. Under conditions where hydrogen peroxide produced by NADPH oxidases or xanthine oxidoreductase does not accumulate, LPO is expected to oxidize thiocyanate via the halogenation cycle and to oxidize urate via the peroxidase cycle. However, under conditions where oxidase activity exceeds peroxidase activity and hydrogen peroxide accumulates, then LPO will be largely inhibited as urate reduces it to compound II and hydrogen peroxide diverts it to compound III. Consequently, information on the in vivo steady state concentrations of hydrogen peroxide is required before we can fully appreciate the biological action of LPO. However, it is clear from this work that urate and thiocyanate should be considered as competing physiological substrates for LPO. They are present in airway lining fluids at largely varying concentration ranges (urate: 40–370 μm, thiocyanate: 50–400 μm) (19, 69), so they will compete for oxidation by compound I. It is likely that under most circumstances thiocyanate is the preferred substrate for compound I and urate will act simply by preventing accumulation of compound II and maintaining production of hypothiocyanite. Under some situations, however, it is possible that urate could be the major substrate for compound I. For example, in hyperuricemic individuals who have a diet low in thiocyanate, urate may be the major substrate. This situation is a potential problem in patients with cystic fibrosis who are prone to hyperuricemia (70) and also have defective transport of thiocyanate into the epithelial lining fluid of their lungs (71). Consequently, LPO, which is present in the airways, would be less effective at producing hypothiocyanite and combatting the frequent infections these patients suffer, but likely to generate potentially harmful electrophiles.

In conclusion, our work has shown that urate reacts rapidly with compound I of LPO and is therefore a likely physiological substrate for LPO under conditions of relatively high urate concentration when compared with thiocyanate. This reaction may thus affect host defense by influencing the bactericidal activity of this enzyme. Further research should be focused on how hydrogen peroxide, thiocyanate, and urate interact in vivo to modulate the activity of LPO and whether the electrophilic species generated from urate oxidation are toxic to either invading bacteria or the host cells.

This work was supported by grants from the University of Otago and the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

- MPO

- myeloperoxidase

- LPO

- lactoperoxidase

- DTNB

- 5,5-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid

- TMB

- 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine

- TNB

- thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid

- FOX

- ferrous oxidation-xylenol orange

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Becker B. F. (1993) Towards the physiological function of uric acid. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 14, 615–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frei B., Stocker R., Ames B. N. (1988) Antioxidant defenses and lipid peroxidation in human blood plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 9748–9752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wayner D. D. M., Burton G. W., Ingold K. U., Barclay L. R. C., Locke S. J. (1987) The relative contributions of vitamin E, urate, ascorbate and proteins to the total peroxyl radical-trapping antioxidant activity of human blood plasma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 924, 408–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uotila J., Metsa-Ketela T., Tuimala R. (1992) Plasma peroxyl radical-trapping capacity in severe preeclampsia is strongly related to uric acid. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. B b11, 71–80 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peden D. B., Hohman R., Brown M. E., Mason R. T., Berkebile C., Fales H. M., Kaliner M. A. (1990) Uric acid is a major antioxidant in human nasal airway secretions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 7638–7642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shi Y. (2010) Caught red-handed: uric acid is an agent of inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 1809–1811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Álvarez-Lario B., Macarrón-Vicente J. (2010) Uric acid and evolution. Rheumatology 49, 2010–2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Merriman T. R., Dalbeth N. (2011) The genetic basis of hyperuricaemia and gout. Joint Bone Spine 78, 35–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cannon P. J., Stason W. B., Demartini F. E., Sommers S. C., Laragh J. H. (1966) Hyperuricemia in primary and renal hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 275, 457–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ford E. S., Li C., Cook S., Choi H. K. (2007) Serum concentrations of uric acid and the metabolic syndrome among us children and adolescents. Circulation 115, 2526–2532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goodarzynejad H., Anvari M. S., Boroumand M. A., Karimi A., Abbasi S. H., Davoodi G. (2010) Hyperuricemia and the presence and severity of coronary artery disease. Lab. Med. 41, 40–45 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lehto S., Niskanen L., Rönnemaa T., Laakso M. (1998) Serum uric acid is a strong predictor of stroke in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Stroke 29, 635–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feig D. I., Kang D.-H., Johnson R. J. (2008) Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 1811–1821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krishnan E. (2011) Uric acid in heart disease: A new c-reactive protein? Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 23, 174–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kang D.-H., Nakagawa T., Feng L., Watanabe S., Han L., Mazzali M., Truong L., Harris R., Johnson R. J. (2002) A role for uric acid in the progression of renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 2888–2897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kutzing M. K., Firestein B. L. (2008) Altered uric acid levels and disease states. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 324, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Choi H. K., Mount D. B., Reginato A. M. (2005) Pathogenesis of gout. Ann. Intern. Med. 143, 499–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson R. J., Rideout B. A. (2004) Uric acid and diet: insights into the epidemic of cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 1071–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van der Vliet A., O'Neill C. A., Cross C. E., Koostra J. M., Volz W. G., Halliwell B., Louie S. (1999) Determination of low-molecular-mass antioxidant concentrations in human respiratory tract lining fluids. Am. J. Physiol. 276, L289–L296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Buettner G. R. (1993) The pecking order of free radicals and antioxidants: Lipid peroxidation, α-tocopherol, and ascorbate. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 300, 535–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Canellakis E. S., Tuttle A. L., Cohen P. P. (1955) A comparative study of the end-products of uric acid oxidation by peroxidases. J. Biol. Chem. 213, 397–404 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Løvstad R. A. (2004) Effect of urate on the lactoperoxidase catalyzed oxidation of adrenaline. BioMetals 17, 631–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meotti F. C., Jameson G. N. L., Turner R., Harwood D. T., Stockwell S., Rees M. D., Thomas S. R., Kettle A. J. (2011) Urate as a physiological substrate for myeloperoxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 12901–12911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ogino N., Yamamoto S., Hayaishi O., Tokuyama T. (1979) Isolation of an activator for prostaglandin hydroperoxidase from bovine vesicular gland cytosol and its identification as uric acid. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 87, 184–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ihalin R., Loimaranta V., Tenovuo J. (2006) Origin, structure, and biological activities of peroxidases in human saliva. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 445, 261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Furtmüller P. G., Jantschko W., Regelsberger G., Jakopitsch C., Arnhold J., Obinger C. (2002) Reaction of lactoperoxidase compound i with halides and thiocyanate. Biochemistry 41, 11895–11900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nagy P., Alguindigue S. S., Ashby M. T. (2006) Lactoperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation of thiocyanate by hydrogen peroxide: A reinvestigation of hypothiocyanite by nuclear magnetic resonance and optical spectroscopy. Biochemistry 45, 12610–12616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wijkstrom-Frei C., El-Chemaly S., Ali-Rachedi R., Gerson C., Cobas M. A., Forteza R., Salathe M., Conner G. E. (2003) Lactoperoxidase and human airway host defense. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 29, 206–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jantschko W., Furtmüller P. G., Allegra M., Livrea M. A., Jakopitsch C., Regelsberger G., Obinger C. (2002) Redox intermediates of plant and mammalian peroxidases: a comparative transient-kinetic study of their reactivity toward indole derivatives. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 398, 12–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tuynman A., Vink M. K. S., Dekker H. L., Schoemaker H. E., Wever R. (1998) The sulphoxidation of thioanisole catalysed by lactoperoxidase and coprinus cinereus peroxidase: evidence for an oxygen-rebound mechanism. Eur. J. Biochem. 258, 906–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Metodiewa D., Dunford H. B. (1990) Evidence for one-electron oxidation of benzylpenicillin g by lactoperoxidase compounds i and ii. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 169, 1211–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Paul K. G., Ohlsson P. I. (1985) in The Lactoperoxidase System, Chemistry and Biological Significance (Pruitt K. M., Tenovuo J. O., ed) pp. 15–29, Marcel Dekker, New York [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pruitt K. M., Mansson-Rahemtulla B., Baldone D. C., Rahemtulla F. (1988) Steady-state kinetics of thiocyanate oxidation catalyzed by human salivary peroxidase. Biochemistry 27, 240–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Odajima T. (1970) Myeloperoxidase of the leukocyte of normal blood. I. Reaction of myeloperoxidase with hydrogen peroxide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 206, 71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCord J. M., Fridovich I. (1968) The reduction of cytochrome c by milk xanthine oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 5753–5760 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Margoliash E., Frohwirt N. (1959) Spectrum of horse-heart cytochrome c. Biochem. J. 71, 570–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Beers R. F., Jr., Sizer I. W. (1952) A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 195, 133–140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kettle A. J., Winterbourn C. C. (1994) Assays for the chlorination activity of myeloperoxidase. Methods Enzymol. 233, 502–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Turner R., Stamp L. K., Kettle A. J. (2012) Detection of allantoin in clinical samples using hydrophilic liquid chromatography with stable isotope dilution negative ion tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 891–892, 85–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fridovich I. (1985) in Handbook of Methods for Oxygen Radical Research (Greenwald R. A., ed) pp. 51–53, CRC Press Inc., Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 41. Massey V. (1959) The microestimation of succinate and the extinction coefficient of cytochrome c. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 34, 255–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wolff S. P. (1994) Ferrous ion oxidation in presence of ferric ion indicator xylenol orange for measurement of hydroperoxides. Methods Enzymol. 233, 182–189 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nirmala J., Sastry K. S. (1975) Photodecomposition of uric acid. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 12, 47–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marquez L. A., Dunford H. B. (1997) Mechanism of the oxidation of 3,5,3′,5′-tetramethylbenzidine by myeloperoxidase determined by transient- and steady-state kinetics. Biochemistry 36, 9349–9355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Harwood D. T., Kettle A. J., Brennan S., Winterbourn C. C. (2009) Simultaneous determination of reduced glutathione, glutathione disulphide and glutathione sulphonamide in cells and physiological fluids by isotope dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed Life Sci. 877, 3393–3399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chapman A. L. P., Mocatta T. J., Shiva S., Seidel A., Chen B., Khalilova I., Paumann-Page M. E., Jameson G. N. L., Winterbourn C. C., Kettle A. J. (2013) Ceruloplasmin is an endogenous inhibitor of myeloperoxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 6465–6477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kettle A. J., Winterbourn C. C. (1994) Superoxide-dependent hydroxylation by myeloperoxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 17146–17151 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stamp L. K., Khalilova I., Tarr J. M., Senthilmohan R., Turner R., Haigh R. C., Winyard P. G., Kettle A. J. (2012) Myeloperoxidase and oxidative stress in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 51, 1796–1803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Johnson L. A. (1957) A kinetic study of the ultraviolet decomposition of biochemical derivatives of nucleic acid. 1. Purines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79, 6187–6192 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lardinois O. M., Medzihradszky K. F., Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (1999) Spin trapping and protein cross-linking of the lactoperoxidase protein radical. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 35441–35448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Furtmüller P. G., Arnhold J., Jantschko W., Zederbauer M., Jakopitsch C., Obinger C. (2005) Standard reduction potentials of all couples of the peroxidase cycle of lactoperoxidase. J. Inorg. Biochem. 99, 1220–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Marquez L. A., Dunford H. B., Van Wart H. (1990) Kinetic studies on the reaction of compound ii of myeloperoxidase with ascorbic acid. Role of ascorbic acid in myeloperoxidase function. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 5666–5670 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Queiroz R. F., Vaz S. M., Augusto O. (2011) Inhibition of the chlorinating activity of myeloperoxidase by tempol: revisiting the kinetics and mechanisms. Biochem. J. 439, 423–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schmid R., Sapunov V. N. (1982) Non-formal kinetics, pp. 32–34, Verlag Chemie, Weinheim, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jantschko W., Furtmüller P. G., Zederbauer M., Neugschwandtner K., Jakopitsch C., Obinger C. (2005) Reaction of ferrous lactoperoxidase with hydrogen peroxide and dioxygen: An anaerobic stopped-flow study. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 434, 51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. van Dalen C. J., Kettle A. J. (2001) Substrates and products of eosinophil peroxidase. Biochem. J. 358, 233–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tahboub Y. R., Galijasevic S., Diamond M. P., Abu-Soud H. M. (2005) Thiocyanate modulates the catalytic activity of mammalian peroxidases. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26129–26136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thomas E. L., Jefferson M. M., Joyner R. E., Cook G. S., King C. C. (1994) Leukocyte myeloperoxidase and salivary lactoperoxidase: Identification and quantitation in human mixed saliva. J. Dent. Res. 73, 544–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vilja P., Lumikari M., Tenovuo J., Sievers G., Tuohimaa P. (1991) Sensitive immunometric assays for secretory peroxidase and myeloperoxidase in human saliva. J. Immunol. Methods 141, 277–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Volk K. J., Yost R. A., Brajter-Toth A. (1990) On-line mass spectrometric investigation of the peroxidase-catalysed oxidation of uric acid. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 8, 205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stevenson W. S., Hyland C. D., Zhang J.-G., Morgan P. O., Willson T. A., Gill A., Hilton A. A., Viney E. M., Bahlo M., Masters S. L., Hennebry S., Richardson S. J., Nicola N. A., Metcalf D., Hilton D. J., Roberts A. W., Alexander W. S. (2010) Deficiency of 5-hydroxyisourate hydrolase causes hepatomegaly and hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 16625–16630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Winterbourn C. C., Kettle A. J. (2003) Radical-radical reactions of superoxide: a potential route to toxicity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 305, 729–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Brück T. B., Fielding R. J., Symons M. C. R., Harvey P. J. (2001) Mechanism of nitrite-stimulated catalysis by lactoperoxidase lactoperoxidase catalysis and nitrite stimulation. Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 3214–3222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sharma S., Singh A. K., Kaushik S., Sinha M., Singh R. P., Sharma P., Sirohi H., Kaur P., Singh T. P. (2013) Lactoperoxidase: structural insights into the function, ligand binding and inhibition. Int. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 4, 108–128 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Furtmüller P. G., Zederbauer M., Jantschko W., Helm J., Bogner M., Jakopitsch C., Obinger C. (2006) Active site structure and catalytic mechanisms of human peroxidases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 445, 199–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Monzani E., Gatti A. L., Profumo A., Casella L., Gullotti M. (1997) Oxidation of phenolic compounds by lactoperoxidase. Evidence for the presence of a low-potential compound ii during catalytic turnover. Biochemistry 36, 1918–1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. van Dalen C. J., Whitehouse M. W., Winterbourn C. C., Kettle A. J. (1997) Thiocyanate and chloride as competing substrates for myeloperoxidase. Biochem. J. 327, 487–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ghibaudi E., Laurenti E., Pacchiardo C., Suriano G., Moguilevsky N., Pia Ferrari R. (2003) Organic and inorganic substrates as probes for comparing native bovine lactoperoxidase and recombinant human myeloperoxidase. J. Inorg. Biochem. 94, 146–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lorentzen D., Durairaj L., Pezzulo A. A., Nakano Y., Launspach J., Stoltz D. A., Zamba G., McCray P. B., Jr., Zabner J., Welsh M. J., Nauseef W. M., Bánfi B. (2011) Concentration of the antibacterial precursor thiocyanate in cystic fibrosis airway secretions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 50, 1144–1150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Horsley A., Helm J., Brennan A., Bright-Thomas R., Webb K., Jones A. (2011) Gout and hyperuricaemia in adults with cystic fibrosis. J. R. Soc. Med. 104, S36–S39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Conner G. E., Wijkstrom-Frei C., Randell S. H., Fernandez V. E., Salathe M. (2007) The lactoperoxidase system links anion transport to host defense in cystic fibrosis. FEBS Lett. 581, 271–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]