Abstract

Expression of germ cell nuclear factor (GCNF; Nr6a1), an orphan member of the nuclear receptor gene family of transcription factors, during gastrulation and neurulation is critical for normal embryogenesis in mice. Gcnf represses the expression of the POU-domain transcription factor Oct4 (Pou5f1) during mouse post-implantation development. Although Gcnf expression is not critical for the embryonic segregation of the germ cell lineage, we found that sexually dimorphic expression of Gcnf in germ cells correlates with the expression of pluripotency-associated genes, such as Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog, as well as the early meiotic marker gene Stra8. To elucidate the role of Gcnf during mouse germ cell differentiation, we generated an ex vivo Gcnf-knockdown model in combination with a regulated CreLox mutation of Gcnf. Lack of Gcnf impairs normal spermatogenesis and oogenesis in vivo, as well as the derivation of germ cells from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in vitro. Inactivation of the Gcnf gene in vivo leads to loss of repression of Oct4 expression in both male and female gonads.

Introduction

Germ Cell Nuclear Factor (GCNF), also known as nuclear receptor subfamily 6, group A, member 1 (Nr6a1), is an orphan member of the nuclear receptor (NR) gene family of ligand-activated transcription factors [1]. Gcnf exhibits distinctive DNA-binding properties. Recombinant Gcnf binds as a homodimer to a response element, a direct repeat with zero base-pair spacing, i.e., a DR0, to repress the expression of genes both in vivo and in vitro [1]–[5]. In vivo, Gcnf appears to be part of a large complex termed transiently retinoid induced factor (TRIF) that binds to DR0 DNA elements in P19 embryonal carcinoma cells (ECCs) or embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [2], [6], [7]. In the mouse, Gcnf is expressed in the developing nervous system, placenta [8], [9], embryonic gonads, and adult ovaries and testes [1], [10], [11]. It is also expressed in round spermatids in mouse and in spermatocytes undergoing meiotic prophase in human [1], [10]–[12]. Gcnf has been found to regulate the transcription of the protamine genes Prm 1 and Prm 2 in mouse testis, antagonizing the effects of CREM tau by binding to DR0 elements in the promoters of these two genes, consistent with a role in regulating adult male fertility [4], [13], [14]. Gcnf is also expressed in the oocytes of vertebrates such as zebra fish, Xenopus, and mouse [1], [10], [15], [16]. Mutation of Gcnf specifically in oocytes using Cre/lox technology and ZP3Cre reduces female fertility [17]. Expression of Gcnf in gastrula- to neurula-stage embryos is critical for normal embryogenesis, as loss of this gene leads to embryonic lethality on embryonic day (E) 10.5 due to multiple defects, including placental and cardiovascular defects, posterior truncation, and disruption of normal somatogenesis and formation of the neural tube [8], [18], [19]. Gcnf acts as a repressor of the POU-domain transcription factor Oct4, a protein essential for the maintenance of the mammalian germline, and other pluripotency-associated genes during mouse post-implantation development. Gcnf-mutant embryos exhibit failure to repress Oct4 expression after gastrulation [2], [6]. Gcnf is essential in the repression and silencing of Oct4 expression during the differentiation of ESCs [6], [7], [20]. Gcnf-dependent repression of Oct4 expression is mediated by Gcnf binding to an evolutionarily conserved DR0 element, located in the Oct4 proximal promoter [2]. As Oct4 is required for the survival of primordial germ cells (PGCs) [21], the question arises as to whether Gcnf plays a role in the segregation or maintenance of the PGC lineage. To address this question, we developed new mouse models and in vitro cell models to study the role of Gcnf in PGCs.

We therefore conducted mechanistic studies to determine the requirement of Gcnf for germ cell development during mammalian development, particularly during meiosis, which represents a critical checkpoint in the formation of normal gametes. Progression of in vitro–derived germ cells through meiosis is still a rare phenomenon and poses a huge challenge for reproductive medicine. Studies on gene regulation in germ cells should enhance our understanding of the mechanisms underlying meiotic processes in vivo, subsequently enabling us to enhance the progression of germ cells through meiosis in vitro. As Gcnf plays an essential role in gene regulation during early mammalian development, this study focused on elucidating the function of Gcnf during the development of murine germ cells.

Results

Gcnf is not required for the segregation of germ cell lineage

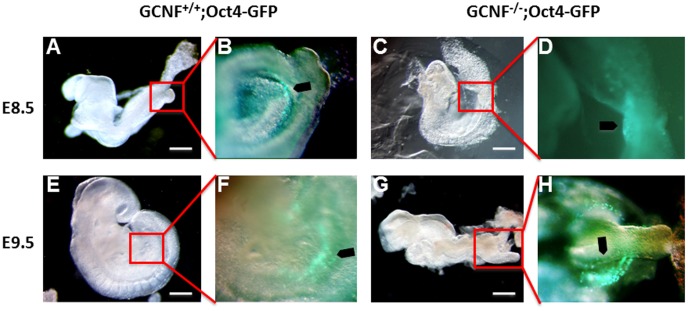

Two outstanding questions in the analysis of the Gcnf-mutant embryo phenotype are whether segregation of the germline has been compromised and whether Gcnf is required for further PGC development. To directly address these questions, we crossed the Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) reporter mice—a transgenic line generated with a construct lacking the proximal enhancer (PE) element of the Oct4 promoter, which typically drives Oct4 expression in the epiblast, here driving the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP)—with our Gcnf-knockout (KO) mice. After gastrulation, widespread expression of Oct4 is repressed and only maintained in PGCs, which reside in the posterior of the embryo and allantois [22], [23]. Therefore, in this study the Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) reporter is specifically expressed in PGCs. We sacrificed pregnant female mice from a heterozygous cross at embryonic day (E) 8.5 and E9.5 (Figure 1). At E8.5, the embryos have not yet turned, and PGCs are clearly visible in the posterior of the embryo, as they begin their anterior migration (Figures 1A and 1B). In Gcnf-mutant embryos, morphological deformation is already evident, and PGCs can be observed in the posterior of the embryo; as there is an approximately equal number of PGCs in wild-type (wt) and mutant embryos (Figure 1C and 1D), Gcnf is not required for segregation of the germ cell lineage. At E9.5, the wt embryo has completed turning, and PGCs can be observed migrating anteriorly along the hindgut toward the developing midgut (Figures 1E and 1F). In contrast, Gcnf-mutant embryos fail to turn, and an ectopic tailbud forms due to posterior truncation. PGCs are still clearly visible in the posterior of mutant embryos, and rather than migrating along the hindgut, some are carried into the ectopic tailbud, indicating that Gcnf is not required for the maintenance of PGCs at this stage of embryonic development.

Figure 1. Detection of PGCs expressing green fluorescence from Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) in wt and Gcnf −/− embryos.

(A–B) wt E8.5 embryos. (C–D) Gcnf −/− E8.5 embryos. (E–F) wt E9.5 embryos. (G–H) Gcnf −/− E9.5 embryos. Arrowheads indicate migratory PGCs. Note that the scale bars are 50 uM. Figures A, C, E and G are 25× and figures B, D, F, and H are 40×.

Sexually dimorphic Gcnf expression in germ cells of the developing gonads

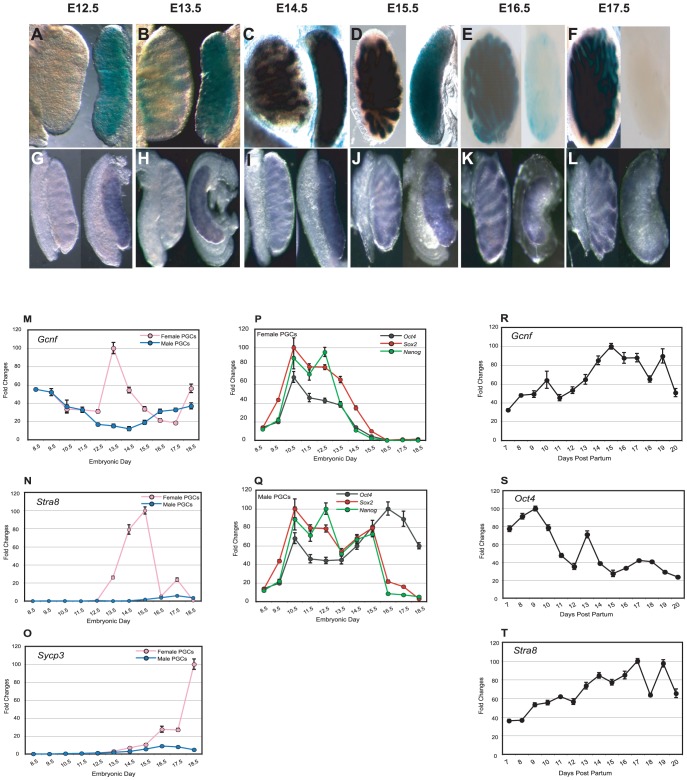

Although Gcnf is not required for germ lineage segregation or maintenance of PGCs during their migratory phase, it may play a role in later stages of germ cell development after formation of the gonads, when Oct4 is normally repressed and meiosis has been initiated. We generated a sensitive Gcnf reporter mouse, a Gcnf LacZ gene trap (GT) model [17]. We analyzed LacZ activity in the dissected gonads of male and female embryos from E12.5 to E17.5. In female gonads, Gcnf expression was detected on E12.5, maintained through E15.5, decreased by E16.5, and completely turned off by E17.5. In contrast, in male gonads, LacZ reporter activity was not detected until E13.5. β-Galactosidase activity continued to increase through E15.5 and was maintained through E17.5 (Figures 2A–2F). To ensure that the sexually dimorphic expression of Gcnf detected in the Gcnf LacZ Knockin (GT) mouse model reflected the expression of the normal gene, we analyzed Gcnf expression in wt mice by whole-mount in situ hybridization (WMISH). A very similar pattern of expression was observed. At E12.5 and E13.5, Gcnf was expressed in female, but not in male, gonads. By E14.5, Gcnf expression was detected in both gonads, but by E17.5, Gcnf expression was turned off in female gonads but maintained in male gonads (Figures 2G–2L).

Figure 2. Analysis of Gcnf, pluripotency-associated genes, and meiosis-related gene expression profiles in PGCs in male and female embryonic gonads and in spermatogonial cells.

(A–F) Analysis of β-galactosidase activity in male (left-hand side of each panel) and female (right-hand side of each panel) gonads in Gcnf LacZ KI embryos on E12.5 to E17.5. (G–L) WMISH analysis of Gcnf expression in the gonads of wt male (left-hand side of each panel) and female mice (right-hand side of each panel) on E12.5 to E17.5. (M–Q) Time-course analysis of gene expression profiles of PGCs from male and female genital ridges and embryonic gonads. Real-time q-RT-PCR analysis of (M) Gcnf. (P–Q) Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2. (N) Stra8, and (O) Sycp3 in PGCs isolated by FACS sorting Oct4-GFP–positive cells from the genital ridges (E8.5 to E11.5) and from male and female fetal gonads on E12.5 to E18.5. (R–T) Time-course analysis of gene expression profiles of spermatogonial cells in newborn testes. Real-time q-RT-PCR analysis of (R) Gcnf. (S) Oct4, and (T) Stra8 in spermatogonial cells isolated by FACS sorting Oct4-GFP–positive cells from the testes at 7 dpp to 20 dpp, i.e., during meiosis in male mice.

To confirm that the Gcnf expression pattern observed in the male and female gonads is consistent with Gcnf expression in germ cells, we analyzed Gcnf expression in purified germ cells. Germ cells from gonads of Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) mice at different stages of development were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell storing (FACS) for GFP-positive cells. Expression of Gcnf, as well as meiosis-related and pluripotency-associated genes in female and male PGCs during fetal development was assessed by real-time quantitative RT-PCR (q-RT-PCR). In female PGCs, expression of pluripotency-associated genes, such as Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog, was steadily downregulated, whereas Gcnf expression was upregulated starting on E12.5, one day before the onset of meiosis (Figures 2M and 2P). In contrast, in male PGCs, which undergo mitotic arrest on E13.5, the mRNA levels of Oct4 remained steadily high until birth (Figure 2Q), whereas expression of Gcnf and the meiosis-related genes Stra8 and Sycp3 remained low in all embryonic stages (Figures 2M, 2N, and 2O). To confirm the correlation of Gcnf and a regulatory role in meiosis, we determined the expression of Gcnf, Oct4, and the meiosis-related gene Stra8 in spermatogonial cells isolated from testes of 7 days post partum (dpp) to 20 dpp. We observed a steady upregulation of expression of Gcnf and Stra8 starting on 7 dpp, but a consistent downregulation of Oct4 expression starting on 10 dpp, which is the onset of meiosis in the male mouse (Figures 2R–2T).

Taken together, these results show that Gcnf expression is upregulated, in contrast to Oct4 expression, which is downregulated, in both female and male germ cells upon entry into meiosis. The temporal expression of Gcnf in male and female PGCs in vivo suggests a potential role for Gcnf in the downregulation of Oct4 expression at the onset of meiosis and an involvement in either initiation of meiosis or activation of meiosis-related genes in both male and female germ cells.

Knockdown of Gcnf in vivo impairs spermatogenesis

Next, we investigated the role played by Gcnf in meiosis. As adult unipotent germline stem cells (GSCs) derived from mouse testes can be expanded indefinitely in culture and can restore spermatogenesis after injection into the seminiferous tubules [24], [25], they are considered to be equivalent to spermatogonial stem cells in vivo. First, we found that Gcnf is expressed in GSCs (Figure S1). Then, we generated a Gcnf-knockdown model to monitor the effect of Gcnf knockdown during spermatogenesis. To this end, we infected GSCs with a lentiviral construct constitutively expressing the fluorescent marker Td-tomato and a shRNA targeting Gcnf (shGcnf) or LacZ (shLacZ) as a negative control. Two to 3 days after infection, more than 80% of the infected GSCs exhibited a positive tomato signal (Figures S2A, S2B, S4A, and S4B). Also we checked the efficiency of shGcnf and observed the downregulation of gene after 48 and 72 hours, which show 75% downregulation of Gcnf after 72 hours (Figure S4C). To determine the functionality of lentiviral-infected cells, GSCs containing shGcnf or shLacZ were transplanted into the seminiferous tubules of germ cell–depleted, busulfan-treated C57BL/6 mice. Only one testis per mouse was transplanted, with the non-transplanted testis serving as a control for endogenous spermatogenesis. Three months later, we observed colonization of the transplanted GSCs in both groups (Figures S2C–S2H).

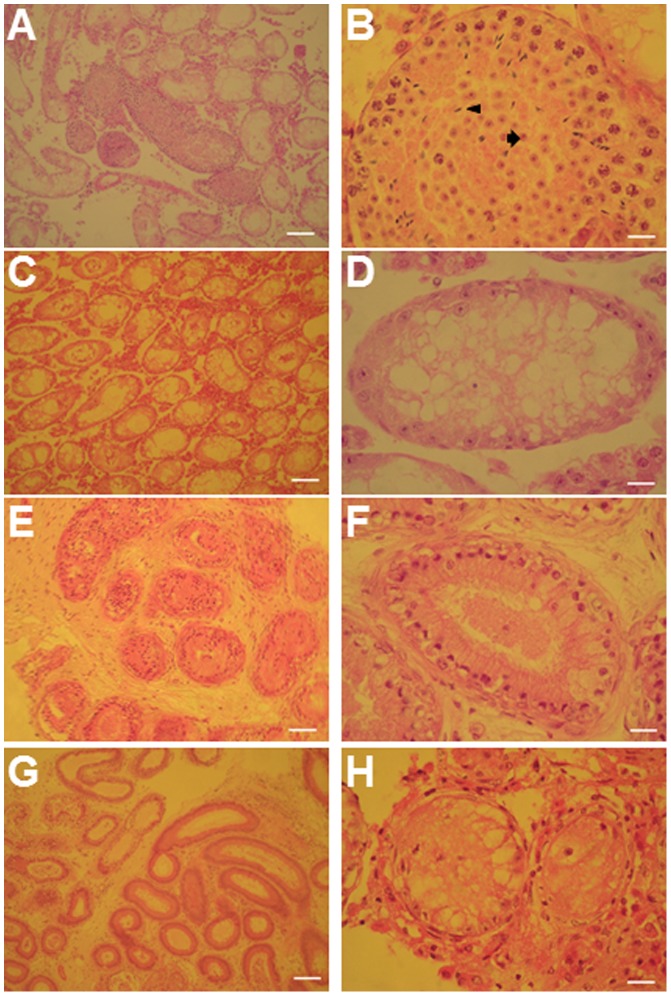

Furthermore, histological analysis of testicular sections of more than 10 transplanted testes from each group revealed that the transplanted shLacZ GSCs (control) had colonized the seminiferous tubules and restored spermatogenesis (Figures 3A and 3B). These tubules contained developing male germ cells of all stages, spermatids, and spermatozoa. In contrast, transplanted shGcnf GSCs had only colonized the tubules, but had failed to restore spermatogenesis (Figures 3E and 3F). Both groups of transplanted GSCs did not form teratomas in the host mice. In addition, histological sections of the non-transplanted testes from the same mice showed no restoration of spermatogenesis 3 months after transplantation, demonstrating that endogenous recovery of spermatogenesis had not occurred in germ cell–depleted mice (Figures 3C, 3D, 3G, and 3H). These results clearly demonstrate that knockdown of Gcnf blocks, or represses, further differentiation of GSCs into functional sperm within the seminiferous tubules of busulfan-treated mice.

Figure 3. Histological sections of transplanted and non-transplanted GSCs into the testis.

(A–B) GSCs without Gcnf siRNA (controls, only with tomato lentivirus). Note the presence of pachytene cells, round spermatids, and fully-grown sperm inside the testicular tubules of the right testis. (C–D) Non-transplanted testicular tubules of the left testis from the same mice, showing no recovery of germ cells in germ cell–depleted testes 3 months after treatment with busulfan. (E–F) GSCs with Gcnf siRNA. Note that GSCs colonized the testicular tubules of the right testis, but failed to differentiate into sperm. (G–H) Non-transplanted testicular tubules of the left testis from the same mice, showing no recovery of germ cells in germ cell–depleted testes 3 months after treatment with busulfan. Note that the scale bars in the left panel are 20 uM and in the right panel are 10 uM.

Impairment of the differentiation of Gcnf-deficient ESCs into PGCs in vitro

To assess the role played by GCNF in the formation of germ cells, we assessed the ability of Gcnf-deficient ESCs to generate PGCs in vitro. Wt and mutant Gcnf ESC lines were derived from Gcnf +/+; Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) and Gcnf −/−; Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) embryos from the same mouse model used in the studies in Figure 1. We analyzed the global gene expression patterns of PGCs derived in vitro on days 12 and 15 of differentiation of Gcnf-deficient ESCs (mutant) compared with those of in vitro–derived PGCs on days 12 and 15 of differentiation of Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESCs (wt). We had previously assessed the dynamics of gene expression and the formation of in vitro–derived PGCs from ESCs in a time-course analysis in vitro, and determined that cells on days 12 and 15 of differentiation exhibited the most PGC-like structural characteristics.

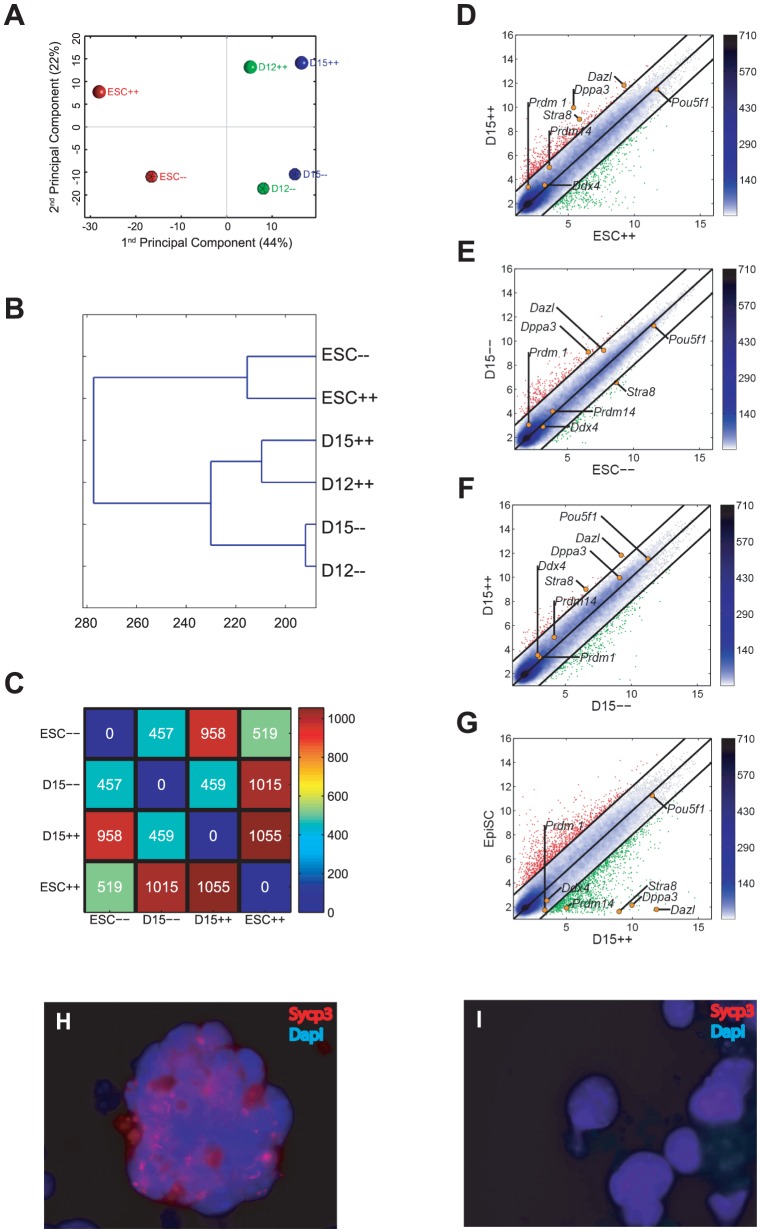

Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESC-derived PGCs exhibited a different global gene expression pattern compared with Gcnf-deficient ESC-derived PGCs on days 12 and 15 of differentiation in vitro. The second PCA component revealed a developmental difference between wt and Gcnf-deficient PGCs in vitro (Figure 4A). Hierarchical cluster analysis of the global gene expression pattern revealed that wt in vitro–derived PGCs clustered separately from Gcnf-deficient in vitro–derived PGCs (Figure 4B). A scatter plot of the global gene expression of ESCs and day-15 in vitro–derived PGCs (corresponding of final stage of in vitro–derived PGCs) showed a more dramatic increase in differentially expressed genes between ESCs and wt in vitro–derived PGCs than between ESCs and Gcnf-deficient in vitro–derived PGCs (Figures 4D and 4E). Specifically, ESCs differed from wt day-15 PGCs by 1,055 genes and from Gcnf-deficient day-15 PGCs by 457 genes (Figure 4C). In addition, a scatter plot of the global gene expression of wt and Gcnf-deficient PGCs derived on day 15 of in vitro differentiation showed that many genes were differentially expressed, particularly PGC-specific and meiosis-related genes (Figure 4F). Finally, comparison of the global gene expression pattern of wt day-15 in vitro–derived PGCs with epiblast stem cells (EpiSCs) showed a dramatic number of differentially expressed genes, thus demonstrating proper germ cell differentiation in vitro (Figure 4G). These results suggest that in the absence of Gcnf, the derivation of in vitro PGCs is impaired.

Figure 4. Global gene expression of Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESC-derived PGCs and Gcnf-deficient ESC-derived PGCs compared with wt ESCs.

(A) Bi-dimensional PCA. The first principal component (PC1) captures 44% of the gene expression variability and the second principal component (PC2) captures 22%. (B) Hierarchical clustering. D denotes days, ++ denotes the wt, and − denotes the mutant groups. (C) Map of distances between samples (using as a metric the number of differentially expressed genes with fold change in log2 scale higher than two). The color bar to the right gives the color codification of the distances—the closer the two samples, the darker the blue color; the further the two samples, the darker the red color. (D–G) Pair-wise scatter plots of global gene expression in ESCs vs. in vitro–derived PGCs. Black lines indicate the boundaries of the two-fold changes in gene expression levels between the paired cell types. Color bar to the right indicates the scattering density—the higher the scattering density, the darker the blue color. Positions of some known PGC markers are shown as orange dots. Gene expression levels are log2 scaled. Genes upregulated in ordinate samples compared with abscissa samples are shown in red circles; genes downregulated are shown in green. (H–I) The localization of Sycp3 was performed in (H) Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESC-derived PGCs and (I) Gcnf-deficient ESC-derived PGCs of day-15 in vitro–differentiation cultures.

To confirm these findings, we determined the expression of day-15 in vitro–derived PGCs by real-time q-RT-PCR. Expression of all known germ cell and meiotic markers was found to be upregulated to moderate levels in Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESC-derived PGCs compared with Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESCs, whereas the expression of these genes was upregulated to a lesser extent in Gcnf-deficient ESC-derived PGCs compared with Gcnf-deficient ESCs (Figures S3A and S3B). We identified 11 genes that were expressed in PGCs but not in pluripotent stem cells [26]. The majority of these genes were found to be expressed in wt day-15 in vitro–derived PGCs but not in day-15 Gcnf-deficient ESC-derived PGCs (Figures S3C and S3D). We examined the localization of synaptonemal complex protein 3 (Sycp3) in both groups of in vitro–derived PGCs on day 15 of differentiation, and showed the positive immunostaining for this protein in Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESC-derived PGCs but not in Gcnf-deficient ESC-derived PGCs (Figures 4H and 4I).

To exclude the possibility that day-15 PGCs are functionally pluripotent, we subcutaneously injected both wt and mutant day-15 in vitro–derived PGCs into severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) recipients. One month after the injection, we did not observe any teratomas in vivo, further confirming that these cells were not pluripotent ESCs. Taken together, our observations suggest that Gcnf is essential for the differentiation of PGCs and initiation of meiosis in vitro.

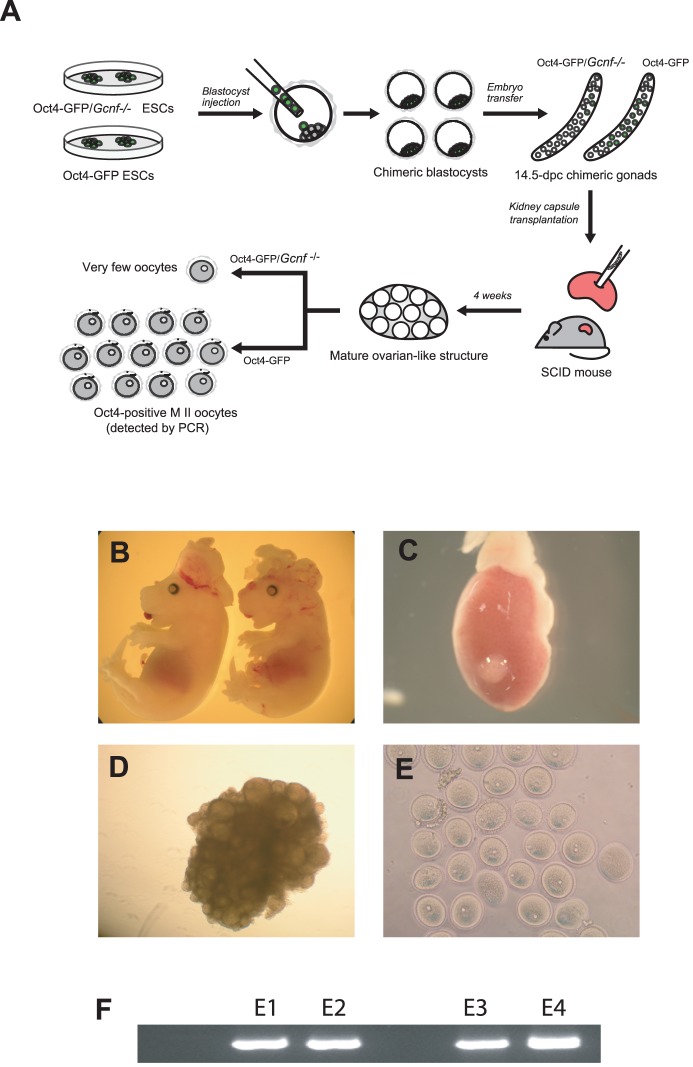

Gcnf is required for development of female fetal PGCs into oocytes

To examine whether Gcnf-deficient ESCs have the developmental potential to differentiate into oocytes in vivo, we used a blastocyst injection strategy with XX Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESCs and XX Gcnf −/−; Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESCs (Figure 5A) to generate chimeras. We then transferred the injected blastocysts into pseudopregnant recipients and subsequently observed germline contribution in the gonads of an E14.5 embryo by means of Oct4-GFP expression. The germline contribution of Gcnf −/−; Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESCs was estimated to be 15% compared with 45% for control ESCs (wt Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESCs), a difference of more than 60%. As more than 30% of chimeric embryos generated from Gcnf-deficient ESCs have brain and neural tube deficiency owing to the involvement of Gcnf in neurogenesis [9], [19] (Figure 5B), we rescued female chimeric gonads by transplanting them under the kidney capsule of SCID mice and examined them after 4 weeks to determine whether wt and Gcnf −/− chimeric gonads had the same potential to develop from early meiotic germ cells into mature oocytes. We observed that both groups of PGCs could develop ectopically into an ovarian-like structure (54% for control ESCs compared with 51% for Gcnf −/− ESCs) under the kidney capsule (Figures 5C and 5D), but we were only able to isolate fully developed MII oocytes from the ovarian-like structures of chimeric gonads generated by blastocyst injection with Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESCs (35–40 MII oocytes from each ovarian-like structure) (Figure 5E). We did not observe fully developed oocytes from the ovarian-like structures of Gcnf −/− chimeric gonads, but only a few degenerated oocytes (5–10 degenerated oocytes from each ovarian-like structure), confirming that Gcnf-deficient ESCs have no developmental potential and differentiate into oocytes in vivo. Although, for unknown reasons, we could not monitor GFP signal in fully developed oocytes under the fluorescence microscope, we were able to detect GFP expression by nested PCR in cumulus cell–free oocytes derived from control ESCs (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

(A) Schematic overview of blastocyst injection, germline contribution, and kidney capsule transplantation of Oct4-GFP ESCs and Gcnf −/−; Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESCs. (B) E14.5-chimeric Gcnf −/− embryos; note that the neural tubes and brain are affected. (C–D) E14.5-chimeric female gonads developed an ovarian-like structure under the kidney capsule of SCID recipients 4 weeks after transplantation. (E) MII oocytes isolated from only the wt ovarian-like structure and (F) expression of GFP performed by nested PCR from an isolated MII oocyte (E1 to E4 depicts the experimental replicate numbers).

Gcnf is required for the repression of Oct4 expression in embryonic gonads

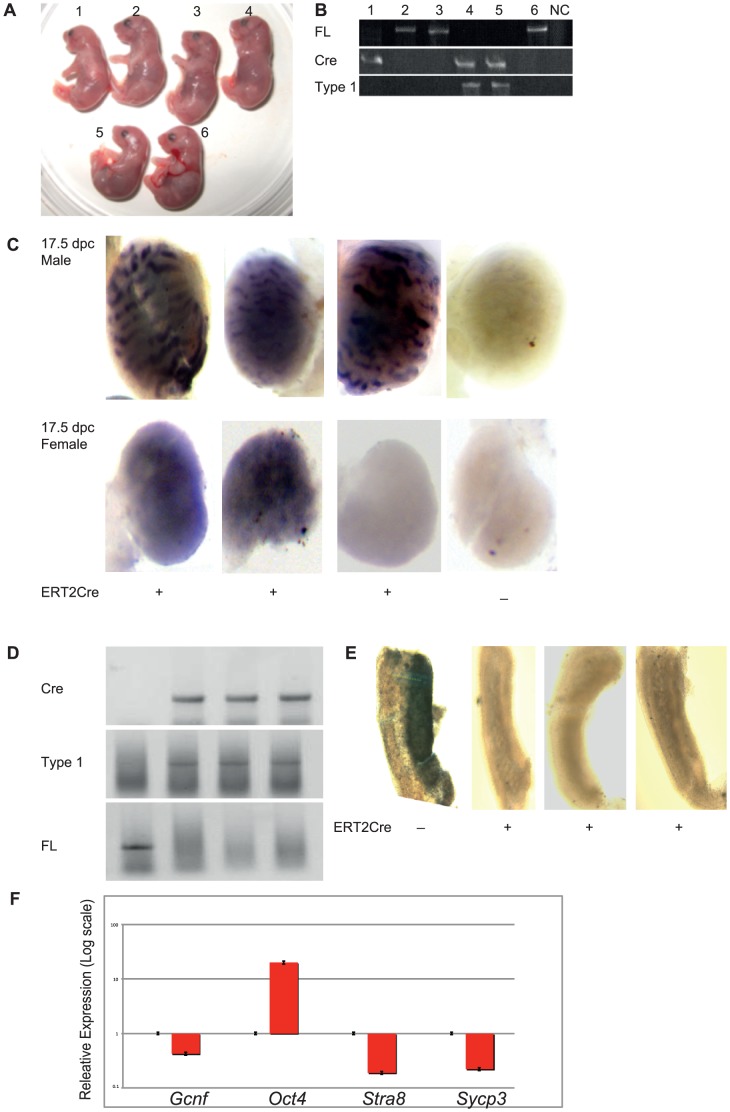

During embryonic development, Oct4 expression is regulated in a sexually dimorphic manner. In female gonads, the expression of Oct4 is silenced upon entry of cells into meiosis. However, in male gonads, Oct4 expression is also repressed later on E17.5. The inverse correlation between Gcnf and Oct4 expression in developing gonads suggests that the retinoid-induced repression of Oct4 during the differentiation of ESCs may reflect a role for Gcnf in the repression of Oct4 expression during gonadal development [6]. To test this hypothesis in vivo, we generated a regulated KO of Gcnf by combining Gcnf fl/fl mouse model with an ERT2Cre mouse model [27] in which this regulator had been knocked into the ROSA locus. We treated pregnant female mice with 4-OH tamoxifen on E11.5 (a time point late enough not to affect the early developmental requirement for GCNF) and then harvested embryos on E17.5 to analyze Oct4 expression. The experiment was designed such that each embryo would be homozygous for the floxed allele and be either Cre positive or negative. The Cre-negative embryo would serve as control for tamoxifen treatment, which can slow embryonic development. An E17.5 litter was weighed, the gonads were dissected, and DNA was isolated from the remainder of the embryos for genotyping. The genotyping identified the embryos as Cre positive or negative and revealed the status of the floxed Gcnf allele (Figures 6A and 6B). In the Cre-negative embryos, the Gcnf floxed allele was intact, while in Cre-positive littermates, the floxed allele was completely recombined to yield what we term a Type I deletion, a deletion in the DNA binding domain–encoding exon [3] (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Analysis of the role of Gcnf and Oct4 in gonadal development in Cre/Lox mutation of the Gcnf gene.

(A–B) The genotyping determined whether the embryos were Cre positive or negative, and the status of the floxed Gcnf allele. (C) WMISH analysis of Oct4 expression on E17.5 in male and female gonads of control Gcnf wt (Cre−) treated with 4-OH tamoxifen and 4-OH tamoxifen–induced ERT2Cre-inactivated Gcnf−/− (Cre+) embryos. (D) The status of the floxed Gcnf allele. (E) WMISH analysis of Stra8 expression on E15.5 in female gonads of control Gcnf wt (Cre−) treated with 4-OH tamoxifen and 4-OH tamoxifen–induced ERT2Cre-inactivated Gcnf−/− (Cre+) embryos. (F) Real-time q-RT-PCR analysis showed that two days of treatment with doxycycline resulted in the upregulation of Oct4 expression and the downregulation of Stra8 and Sycp3 expression in 14.5-dpc female gonads of Tet-Oct4 pregnant mice (14.5-dpc female PGCs were considered as 1 for normalization).

WMISH analysis of Oct4 expression in the male gonads on E17.5 showed that Cre-negative embryos exhibited low Oct4 expression, while Cre-positive embryos showed loss of repression of Oct4 expression (10 of 10 embryos). In female embryos, two events were observed. In some embryos, there was repression of Oct4 expression on E17.5, while in others, there was clear loss of repression of Oct4 expression on E17.5 (Figures 6C). The difference between the two types of female responses is most likely due to the timing of Cre recombination of the floxed Gcnf alleles. In female gonads with abrogated Oct4 repression, the Gcnf allele is inactivated at an early enough time point to prevent significant Gcnf expression. In female gonads with silenced Oct4 expression, the Gcnf gene is not completely inactivated, resulting in induction of Gcnf expression and production of enough Gcnf protein to silence Oct4 expression. However, Gcnf is clearly required to repress Oct4 expression during the critical stages of gonadal development.

To confirm the correlation of Gcnf and Oct4 expression in gonadal development and particularly the requirement for Oct4 levels in the initiation of meiosis, we first performed conditional ectopic overexpression of Oct4 levels in 14.5-dpc female gonads. To assess the short-term effect of Oct4 ectopic expression in vivo, we crossed a Tet-Oct4 mouse [28] with an Oct4-GFP mouse. We fed pregnant female mice drinking water that contained doxycycline on E12.5 (a time point when meiosis-related genes just start to be overexpressed in developing female gonads) and then harvested the embryos on E14.5 to analyze Oct4, Stra8, and Sycp3 expression.

Interestingly, ectopic activation of Oct4 in developing female gonads results in the inhibition of expression of meiosis markers such as Stra8 and Sycp3 (Figure 6F) and the interruption of meiotic initiation as typically seen in female gonads at this time of PGC development (Figures 2N and 2O). Taken together, these results showed that downregulation of Oct4 expression is clearly required to activate Stra8 and Sycp3 expression during the onset of meiosis in developing female gonads, and confirmed that meiosis markers are not upregulated in developing male germ cells before birth, as Oct4 levels are not reduced in male gonads.

Gcnf is required for enhancing Stra8 expression in embryonic gonads

Stra8 expression is regulated in a sexually dimorphic manner during embryonic development. In female gonads, the expression of Stra8 is activated upon entry of cells into meiosis on E12.5, increases gradually till E15.5, and is dramatically downregulated on E16.5 at prophase I arrest in female gonads (Figure 2N). However, in male gonads, Stra8 expression is nearly completely repressed during embryonic development. In male gonads, Stra8 expression is activated in the testis during neonatal development, increases steadily starting on 7 dpp, and continues till 19 dpp, coincident with the onset of meiosis in male spermatogonial cells (Figure 2T). The direct correlation between Gcnf and Stra8 expression in developing gonads (Figure 2M, 2N and 2T) suggests that the retinoid-induced activation of Stra8 expression during the differentiation of ESCs may reflect a role for Gcnf in the activation of Stra8 expression during gonadal development [7], [29]. To test this hypothesis in vivo, we used the same KO model for Gcnf by crossing the Gcnf fl/fl mouse with an ERT2Cre mouse. We treated pregnant female mice with 4-OH tamoxifen on E11.5 (a time point late enough not to affect the early developmental requirement for Gcnf) and then harvested embryos on E15.5 to analyze Stra8 expression.

WMISH analysis of Stra8 expression in the female gonads on E15.5 showed that Cre-negative embryos exhibited high Stra8 expression, while Cre-positive embryos showed loss of activation of Stra8 expression (4 of 4 embryos) (Figure 6D–6E). This means that in female gonads with loss of Gcnf expression, the Stra8 gene is not completely activated, resulting in inhibition of meiotic initiation. These results showed that Gcnf is clearly required to activate Stra8 expression during onset of meiosis in the development of both male and female gonads.

Discussion

Previous studies [1], [10], [11], [30]–[32] have shown that the Gcnf gene is active in adult testes and ovaries and is required for reproduction in female mice [17]. In adult testis, Gcnf acts as a transcriptional regulator of the postmeiotic genes Protamine 1 and 2 (Prm 1, Prm 2), functionally inhibiting CREMtau [4], [13], [14], [33], whereas in the adult ovary, Gcnf regulates the expression of bone morphogenetic protein 15 (Bmp15) and growth differentiation factor 9 (Gdf9) [17]. The Cre/Lox mutation of floxed Gcnf by ZP3Cre leads to subfertility in female mice [17]. Our current study demonstrates that Gcnf is involved in male and female gametogenesis during mouse development. We show that loss of Gcnf results in failure to produce spermatogonia and oocytes in developing testes and ovaries, respectively. Our study also shows that Gcnf is required to repress Oct4 expression during gonadal development.

Segregation of germ cells in the mouse occurs on E7.25 of embryonic development, when PGCs arise as a small cluster of alkaline phosphate–positive cells in the extraembryonic mesoderm [34]–[38]. At this developmental time point, Gcnf is functionally active and is required to repress pluripotency genes such as Oct4—as the pluripotent late epiblast is patterned during gastrulation—and Gcnf −/− embryos begin displaying phenotypic alterations compared with wt embryos. Thus, to determine whether Gcnf is required in the formation of the PGC lineage, we crossed the PGC reporter Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) with Gcnf −/− mice. We clearly observe GFP-positive PGCs in the posterior of Gcnf −/− embryos. Thus, Gcnf is not required for the segregation of the germ cell lineage. The normal anterior migration of PGCs from the allantois to the midgut, however, is disrupted in the Gcnf−/− embryos, and some PGCs even migrate into the ectopic tail bud [8]. Although we cannot rule out that Gcnf plays a direct role in the migration and homing of PGCs, the defect is more likely a secondary effect of the developmental defects of KO embryos.

To determine whether Gcnf plays a role in later stages of PGC development, we analyzed Gcnf expression at various stages of germ cell development. Gcnf LacZ Knockin (KI) mice displayed sexually dimorphic expression of β-galactosidase activity, suggesting that Gcnf plays a role in gonadal development. To confirm that this reporter accurately reflected Gcnf expression, we performed WMISH hybridization, which confirmed the sexually dimorphic expression observed. We then isolated germ cells from transgenic mice harboring the Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) reporter to confirm that the expression of Gcnf was indeed confined to the germ cell compartment. In addition, we analyzed the expression of meiosis-related genes as well as pluripotency-associated genes, as Oct4 is the main pluripotency-related gene required for the maintenance and survival of PGCs [21].

In female embryonic gonads, upregulation of Gcnf expression begins at around E12.5, concordant with the upregulation of the premeiosis-related gene Stra8. In contrast, downregulation of pluripotency-associated genes, such as Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog, is observed at the onset of meiosis. Gene expression analysis in spermatogonial cells of newborn testis and embryonic female gonads confirmed a correlation between Gcnf, Oct4, and Stra8 expression at the onset of meiosis in both sexes. In contrast, we did not observe coincident upregulation of Gcnf with Stra8 and Sycp3 expression, and downregulation of Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog expression in male embryonic gonads at mitotic arrest on E13.5. As Gcnf represses the expression of Oct4 [2], these results suggest a possible association between Gcnf, Oct4, and Stra8 in regulating the initiation of meiosis in germ cells. To confirm this hypothesis and the requirement for Oct4 downregulation in the activation of Stra8 and Sycp3 expression during onset of meiosis in the development of female gonads, we demonstrated that upregulation of Oct4 levels alone inhibited the expression of meiosis markers such as Stra8 and Sycp3 and consequently interrupted meiotic initiation. This suggests that the concomitant activation of Gcnf expression and Oct4 repression is required for the activation of meiosis-related genes.

We previously reported that adult unipotent germline stem cells derived from mouse testes could colonize the seminiferous tubules of busulfan-treated mice and restore spermatogenesis [24]. Here, we observed that knockdown of Gcnf by using small hairpin RNA (shRNA) in GSCs inhibits the differentiation of GSCs into functional sperm and blocks the restoration of spermatogenesis after transplantation of these cells into the seminiferous tubules of busulfan-treated mice. This observation is consistent with those of previous reports [1], [10], [11], [30]–[32], confirming a functional role for Gcnf in spermatogenesis in the mouse.

To support a potential role for Gcnf during germ cell development and onset of meiosis, we assessed the ability of Gcnf-deficient ESCs to differentiate into PGCs in vitro. By using global gene expression analysis, real-time q-RT-PCR of known and newly identified PGCs markers, and localization of meiosis-related proteins, we showed that in contrast to wt ESCs, Gcnf −/− ESCs fail to differentiate into PGCs and initiate meiosis in vitro. Previous studies have shown that Gcnf is expressed in developing oocytes during folliculogenesis in the mouse [1], [10], [11]. Gcnf may be involved in female fertility by regulating the expression of Bmp15 and Gdf9 [17]. In this study, we demonstrated that Gcnf is required for the development of female fetal PGCs into oocytes. Although both wt and Gcnf-deficient ESCs were able to contribute to the germline, following the transplantation of a chimeric fetal ovary under the kidney capsule of SCID mice, Gcnf −/− PGCs could not generate mature oocytes inside the grafted ovary. Our finding suggests that Gcnf is essential for further development and maturation of PGCs into oocytes.

Here we report that Gcnf is required for spermatogenesis and oogenesis in the mouse and that loss of Gcnf disrupts the formation of functional gametes. Taken together, our findings using (1) gene expression in PGC development, (2) disruption of spermatogenesis after downregulation of Gcnf, (3) impairment of in vitro differentiation of PGCs by using Gcnf −/− ESCs, and (4) the inability of ectopic development of a chimeric fetal ovary under the kidney capsule of host mice all provide a robust model for a regulatory role for Gcnf in germ cell development. Support for the role of Gcnf in the maintenance of germ cells has been provided by ex vivo experiments using an in vivo–regulated Cre/Lox KO of Gcnf during gestation. The Gcnf gene was successfully deleted in the gonads and the embryo as a whole, and defects in Oct4 expression were observed. These defects are due to inactivation of the Gcnf gene in PGCs, as opposed to a secondary effect on development, as the whole embryos were normal overall. These results contrast those of a similar KO strategy by the Page group, who reported no functional requirement for Gcnf or its ligand-binding domain in germ cell development [39]. The two Gcnf floxed models differ in the regions deleted; in addition, another significant difference between the two studies is the use of tamoxifen to activate ERT2Cre, which first has to be metabolized into the active form 4-hydroxy tamoxifen before it can activate ERT2Cre, which would cause a functional delay to generate defects in Oct4 expression. We used 4-hydoxy tamoxifen to activate ERT2Cre, which would allow for earlier deletion of Gcnf expression and thus readily generate a phenotype.

Clearly, like in ESCs, Gcnf plays an essential role in the repression of Oct4 expression in female gonads as they exit mitosis and enter meiotic prophase I. Postnatally, Gcnf likely plays a role in maintaining germ cells in both male and female newborns, as shown in the various experiments detailed here. This functional window must lie between the ERT2Cre KO of Gcnf during embryonic development, as the gonads still contain germ cells and the late-stage ZP3Cre KO of Gcnf in adult female mice, which showed fertility defects but no loss of germ cells. Other mouse models are needed to delineate this important function of Gcnf in early postnatal life.

Several research groups have shown that the Stra8 gene (stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8) is a premeiotic marker that is expressed in premeiotic germ cells of the testes and ovaries and is regulated by retinoic acid [40], [41]. Loss of Stra8 gene function in germ cells leads to inhibition of onset of meiosis and results in the failure of germ cells to undergo meiosis in the ovaries or testes of Stra8 −/− mice [42]–[44].

We hypothesize that Gcnf plays either a direct or indirect role in germ cell development, and suggest a possible function for Gcnf in the activation or initiation of meiosis by enhancing Stra8 expression and inhibiting the expression of pluripotency-associated genes. This knowledge should enhance our understanding of the key mechanisms underlying germ cell development and onset of meiosis as well as prove beneficial for the derivation of viable and fertile sperm and oocytes from pluripotent stem cells in vitro.

Methods

Animal ethics

This study was performed in accordance with the recommendations of the Federation of Laboratory Animal Science Associations (FELASA). The corresponding ethics protocol for mice works was approved by the Landesamt für Natur, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz (LANUV) of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany, and the corresponding ethics protocol for testicular transplantation was approved by Center for Stem Cell Research, Institute of Biomedical Sciences and Technology, Konkuk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Analysis of the Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) in Gcnf KO embryos

Transgenic mice harboring the Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) reporter were crossed with Gcnf +/− mice to generate Gcnf +/−; Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) mice, which were subsequently crossed with Gcnf +/− mice to generate embryonic litters with +/+, +/−, and −/−. Timed pregnant female mice were euthanized and embryos were harvested on E8.5 and E9.5. The fluorescent Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) reporter was visualized in PGCs using a Zeiss Stemi SV11.

Reporter LacZ staining

LacZ staining of embryonic gonads, which were isolated from matings between Gcnf LacZ KI heterozygous mice on E12.5–E17.5 with X-Gal staining, was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The yolk sacs of the embryos were lysed for genotyping.

WMISH

Gcnf fl/fl mice were crossed with ROSA ERT2Cre mice to generate Gcnf fl/+ ERT2Cre mice, which were then crossed with Gcnf fl/fl mice; female mice were checked daily for plugs and treated with 1 mg 4-OH tamoxifen (Sigma, H7904) once on E11.5. The gonads were isolated from embryos on E17.5 and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The yolk sacs of embryos were lysed for genotyping. WMISHs were carried out as described previously [2]. Genotyping Primers:

Gcnf LacZ KI:

Primer1: 5′TCGAGCGATGTTTCGCTT3′;

Primer2: 5′ATATGGGATCGGCCATTGA3′;

Primer3: 5′CAGTGCTGACTTATCCATG3′;

Primer4: 5′TTCCTGTTCATGCCCATCT3′.

Gcnf fl:

PCR-A: 5′CGAACTCAGAAATCCACC3′;

PCR-C: 5′AATCACAAACACCACAACTC3′.

Gcnf Type I:

Type I-F: 5′CCAATTCCCCCAAAGTGTC3′

Type I-R: 5′CAGGTCGAGGGACCTATAAC3′.

ERT2Cre:

Cre-F: 5′CGGTCGATGCAACGAGTGAT3′;

Cre-R: 5′CCACCGTCAGTACGTGAGAT3′.

Isolation of PGCs from mouse fetus and flow cytometric analysis

Germ cells of E8.5 to E18.5 embryos were isolated from OG2 (Oct4ΔPE-GFP)/CD1 mice by disaggregating the genital ridges of E8.5 to E11.5 embryos and the fetal gonads of E12.5 to E18.5 embryos. Disaggregation was performed by enzymatic digestion with collagenase type 1A (Sigma) and trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) at a ratio of 1∶2 with shaking at 700 rpm for 8 min at 37°C. Single-cell suspension was achieved more efficiently by triturating the cell aggregates. Enzymatic digestion was stopped by adding a two-fold excess of DMEM/F12+10% FBS. Cell suspensions were washed once in DMEM/F12+10% FBS and FACS sorted for GFP. GFP-positive PGCs were directly sorted into lysis buffer RLT (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). Single-cell suspensions of GFP-positive PGCs were analyzed using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was done using FlowJo software (Treestar).

RNA isolation

RNA from FACS-sorted, GFP-positive PGCs was isolated using the RNeasy micro and mini kits (QIAGEN) with on-column DNase digestion as per the manufacturer's instructions. The quality of RNA was determined using a Nanodrop (ND-1000) spectrophotometer and an Agilent RNA 2100 Bioanalyzer.

RT-PCR and real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA (250 ng) was reverse transcribed into cDNA by using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). q-RT-PCR was performed on 7900ht and ht fast devices (Applied Biosystems) with milliQ H2O and TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Raw data was obtained by SDS 2.3 (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was normalized to the mouse housekeeping gene Hprt. Relative quantitation of gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method. Three technical replicates were used for each real-time q-RT-PCR reaction; a reverse transcriptase blank and a no-template blank served as negative controls. Primer sequences for real-time q-RT-PCR are listed as supplementary material (Tables S1 and S2).

Vector construction and transduction with lentiviral vectors

pLVTHM-Td tomato was constructed by replacing the GFP in pLVTHM with the Td-tomato coding sequence. DNA constructs designed to produce shRNA hairpins targeting Gcnf (5′- GGATGAATTGGCAGAGCTTGATTCAAGAGATCAAGCTCTGCCAATTCATCC –3′) or LacZ (5′-GTGGATCAGTCGCTGATTAAATTCAAGAGATTTAATCAGCGACTGATCCAC –3′) were cloned in front of the H1 promoter into the pLVTHM-Td tomato vector to produce pLVTHM-shGcnf and pLVTHM-shLacZ, respectively. The 293T cell line was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS. The recombinant lentiviruses were produced by transient transfection of 293T cells with 12 µg of pLVTHM-shGcnf or pLVTHM-shLacZ, 8.5 µg of psPax2, and 3 µg of pMD2.G using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The supernatant was collected at 24 and 48 hr of transfection and concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 26,000 rpm for 2 hr at 4°C using an SW41 rotor (Beckman Coulter). After ultracentrifugation, the supernatant was decanted, and the viral pellet was resuspended in 200 µl of DMEM. The suspension was stored at −80°C until use. pLVTHM and packaging plasmids were provided by D. Trono (Geneva, Switzerland). GSCs were plated on 24-well plates (5×104 cells/well), and 20 µl of the concentrated virus were added to the medium. Cells were washed after 16 hr of incubation.

Testicular transplantation

The transplantation experiments were performed as previously described [45]. Four-week-old germ-cell–depleted (40 mg/kg busulfan-treated) male mice were used as recipient mice. Approximately 3×105 cells were injected with a micropipette (80-µm diameter tips) into the seminiferous tubules of the testes of recipient mice through the efferent duct. Three months after the transplantation, the mice were sacrificed, and the seminiferous tubules were dissociated by collagenase treatment and examined under a fluorescence microscope to detect transplanted GSCs by their RFP expression. To assess further colonization as well as restoration of spermatogenesis, the testes were fixed in Bouin's solution and embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

ESCs

Male and female Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESCs and female Gcnf −/− ESCs [8] were grown on gamma-irradiated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in KNOCKOUT DMEM medium containing 4.5 g/l glucose and supplemented with 15% KNOCKOUT SR (Invitrogen), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 µM nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 1 µM 2-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen), and 50 µg/ml each penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen) in the presence of 1,000 U/ml murine leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (ESGRO; Chemicon).

In vitro differentiation of PGCs from ESCs

Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESCs and Gcnf −/− ESCs were grown in 0.1% gelatin-coated tissue culture plates in ESC medium supplemented with 15% FBS (Invitrogen) but without LIF and in the absence of MEFs at a density of approximately 8–9×104 cells/cm2. Non-adherent cells were removed after 3 days and the medium was replaced. GFP expression was monitored every 3 days in cells undergoing further differentiation until day 15. Approximately 25% of all cells exhibited GFP expression on day 15. The medium in the master culture plates was replaced every 2 days [46].

Isolation of in vitro–derived PGCs from differentiation culture plates

Every 3 days, cells were dissociated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA, neutralized with KNOCKOUT DMEM containing 15% FBS, washed twice with PBS, and then resuspended in KNOCKOUT DMEM containing 15% FBS. Approximately 2×106 cells/ml in DMEM/FBS were used for FACS sorting. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACSAria cell sorter. Putative PGCs derived from ESCs were sorted based on Oct4-GFP expression and then subjected to germ cell characterization, e.g., gene expression, ability for tumor formation, and localization of meiosis-related proteins.

Teratoma formation

Day-12 and day-15 in vitro–derived PGCs were suspended in DMEM containing 15% FBS. A 200-µl aliquot (1×106 cells) of the cell suspension was injected subcutaneously into the dorsal flanks of SCID mice. Following injection of the in vitro–derived PGCs, wt and mutant ESCs were also subcutaneously injected into the SCID mice as controls. Four weeks after the injection, tumors were dissected from the mice. Samples were fixed in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections were stained with H&E.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for Sycp3 was performed using the spreading technique, as previously described by others [47]. Slides were incubated with primary anti-Sycp3 (1∶500; Abcam) for 2 hr at room temperature. After washing in blocking solution, slides were incubated with secondary fluorescent antibody (1∶1,000; Alexa 568; Molecular Probes) for 1 hr at room temperature and then mounted in DAPI-containing mounting medium (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories Inc.).

Chimera formation

Six- to eight-week-old female mice (B6C3F1) were induced to superovulate (via intraperitoneal injection of 7.5 I.U. PMSG and 48 hr later of 7.5 I.U. hCG) and mated with CD1 male mice. Blastocysts were collected on day 3.5 after a vaginal plug check and flushed in HCZB medium containing 0.1% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP). Blastocysts were washed extensively with HCZB medium and cultured in Alpha MEM medium containing 0.2% BSA at 37°C, 5% CO2 in air until injection with ESCs.

Forty to sixty ESC colonies were selected and picked under a stereomicroscope based on the colony shape and morphology, washed with PBS, and then transferred into a drop of 0.05% trypsin-EDTA to obtain a single-cell suspension. Single cells were then transferred into the micromanipulation chamber in a drop of HCZB medium containing 0.1% PVP and 0.2% BSA. Groups of 12–15 cells were injected into a single blastocyst. Injected embryos were then transferred into a drop of Alpha MEM-BSA and cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 in air. After 4 hr of culture, chimeric blastocysts were transferred into the uterine horns of 2.5-dpc pseudopregnant CD1 recipient female mice.

Transplantation of chimeric ovaries under the kidney capsule

Fourteen days after transfer of the chimeric blastocysts into the uterine horns, the fetal ovaries of 14.5-dpc embryos were obtained from pregnant pseudopregnant CD1 recipient female mice and screened for germline contribution under fluorescent microscope. One to two chimeric fetal ovaries without attached mesonephroses were transplanted under the kidney capsule of ovariectomized female SCID recipient mice. Four weeks after transplantation, chimeric ovarian grafts were removed from the recipient mice and analyzed for both ovarian maturation and number and quality of existing oocytes.

Nested PCR to detect GFP signal in oocytes

The presence of the GFP signal was determined using nested PCR, as previously described by others [48]. Briefly, for primary reactions, we used 4 µl of DNA template from a pool of isolated oocytes in a total volume of 15 µl. Cycling conditions consisted of an initial 3-min denaturation at 95°C, followed by 25 cycles, each consisting of a 30-sec denaturation at 94°C, a 45-sec annealing at 55°C, and a 1-min extension at 72°C. These 25 cycles were followed by a 7-min extension at 72°C. For the nested amplifications, we used 1.0 µl of the primary PCR product as the template in a total reaction volume of 12 µl. Nested cycling conditions were as described for the primary amplification, except that 35 cycles were used. Reaction products were subsequently analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Negative controls of oocytes from non-transgenic mice as well as a reverse transcriptase blank and a no-template blank were included in each experiment.

Global gene expression analysis

For RNA isolation, PGCs were sorted by FACS, collected by centrifugation, lysed in RLT buffer (QIAGEN), and processed using the RNeasy micro and mini kits with on-column DNase digestion as per the manufacturer's instructions. Integrity of RNA samples was quality checked using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent). When possible, 300 ng of total RNA per sample were used as starting material for linear amplification (Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit, Ambion), which involved synthesis of T7-linked double-stranded cDNA and 14 hr of in vitro transcription incorporating biotin-labeled nucleotides. Purified and labeled cRNA was then quality checked on a 2100 Bioanalyser and hybridized as biological or technical duplicates for 18 hr onto MouseRef-8 v2 gene expression BeadChips (Illumina), following the manufacturer's instructions. After being washed, the chips were stained with streptavidin-Cy3 (GE Healthcare) and scanned using an iScan reader and accompanying software.

Microarray data processing

Bead intensities were mapped to gene information using BeadStudio 3.2 (Illumina). Background correction was performed using the Affymetrix Robust Multi-array Analysis (RMA) background correction model [49]. Variance stabilization was performed using log2 scaling, and gene expression normalization was calculated with the quantile method implemented in the lumi package of R-Bioconductor. Data post-processing and graphics were performed with in-house developed functions in Matlab. Hierarchical clustering of genes and samples was performed with a correlation metric and the Unweighted Pair-Group Method using Average (UPGMA) linkage method.

All the raw and processed microarray data discussed in this publication have been deposited into NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus [50] and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE57506. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi$acc=GSE57506).

Supporting Information

Global gene expression shows the Gcnf expression in different lines of mouse GSCs, compared with ESCs and germline-derived pluripotent stem cells (gPSCs).

(EPS)

Light microscopy of transplanted and non-transplanted GSCs into the testis. (A–B) Tomato lentivirus–infected GSCs before transplantation into the seminiferous tubules of germ cell–depleted busulfan-treated mice. (C–D) GSCs without Gcnf siRNA (controls, only with tomato lentivirus); note the red GSCs have colonized the tubules. (E–F) GSCs with Gcnf siRNA; note the red GSCs have colonized the tubules. (G–H) Non-transplanted testicular tubules, showing no recovery of germ cells in germ cell–depleted testes 3 months after treatment with busulfan. Note that the scale bars are 20 uM.

(TIF)

Expression of known germ cell markers and the newly identified genes in day-15 in vitro –derived PGCs. Real-time q-RT-PCR of pluripotency and known germ cell markers in (A) Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESC-derived PGCs and (B) Gcnf-deficient ESC-derived PGCs compared with ESCs. D denotes days. Real-time q-RT-PCR of the newly identified genes in (C) Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESC-derived PGCs and (D) Gcnf-deficient ESC-derived PGCs compared with ESCs.

(EPS)

Efficiency of shRNA transfection in GSCs. (A–B) FACS sorting plots, showing that more than 80% of the infected GSCs exhibited a positive tomato signal. (C) Depict the efficiency of shGcnf and showed the downregulation of gene in cells after 48 and 72 hours (75% downregulation of Gcnf after 72 hours).

(TIF)

Assay codes for TaqMan real-time q-RT-PCR.

(TIF)

List of primers used for SYBR Green real-time q-RT-PCR.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank David Obridge, Martina Sinn, and Claudia Ortmeier for technical assistance. We also thank Jeanine Müller-Keuker for help with the figures and Martin Stehling for assistance with FACS sorting.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Max Planck Society and the DFG grant for research unit germ cell potential, FOR 1041 (HSR) and National Institutes of Health grant NIH P01 GM081627 (AJC). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Chen F, Cooney AJ, Wang Y, Law SW, O'Malley BW (1994) Cloning of a novel orphan receptor (GCNF) expressed during germ cell development. Mol Endocrinol 8: 1434–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fuhrmann G, Chung AC, Jackson KJ, Hummelke G, Baniahmad A, et al. (2001) Mouse germline restriction of Oct4 expression by germ cell nuclear factor. Dev Cell 1: 377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lan ZJ, Chung AC, Xu X, DeMayo FJ, Cooney AJ (2002) The embryonic function of germ cell nuclear factor is dependent on the DNA binding domain. J Biol Chem 277: 50660–50667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yan ZH, Medvedev A, Hirose T, Gotoh H, Jetten AM (1997) Characterization of the response element and DNA binding properties of the nuclear orphan receptor germ cell nuclear factor/retinoid receptor-related testis-associated receptor. J Biol Chem 272: 10565–10572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schmitz TP, Susens U, Borgmeyer U (1999) DNA binding, protein interaction and differential expression of the human germ cell nuclear factor. Biochim Biophys Acta 1446: 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gu P, LeMenuet D, Chung AC, Mancini M, Wheeler DA, et al. (2005) Orphan nuclear receptor GCNF is required for the repression of pluripotency genes during retinoic acid-induced embryonic stem cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 25: 8507–8519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 7. Gu P, Xu X, Le Menuet D, Chung AC, Cooney AJ (2011) Differential recruitment of methyl CpG-binding domain factors and DNA methyltransferases by the orphan receptor germ cell nuclear factor initiates the repression and silencing of Oct4. Stem Cells 29: 1041–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chung AC, Katz D, Pereira FA, Jackson KJ, DeMayo FJ, et al. (2001) Loss of orphan receptor germ cell nuclear factor function results in ectopic development of the tail bud and a novel posterior truncation. Mol Cell Biol 21: 663–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Susens U, Aguiluz JB, Evans RM, Borgmeyer U (1997) The germ cell nuclear factor mGCNF is expressed in the developing nervous system. Dev Neurosci 19: 410–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katz D, Niederberger C, Slaughter GR, Cooney AJ (1997) Characterization of germ cell-specific expression of the orphan nuclear receptor, germ cell nuclear factor. Endocrinology 138: 4364–4372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lan ZJ, Gu P, Xu X, Cooney AJ (2003) Expression of the orphan nuclear receptor, germ cell nuclear factor, in mouse gonads and preimplantation embryos. Biol Reprod 68: 282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agoulnik IY, Cho Y, Niederberger C, Kieback DG, Cooney AJ (1998) Cloning, expression analysis and chromosomal localization of the human nuclear receptor gene GCNF. FEBS Lett 424: 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hummelke GC, Cooney AJ (2001) Germ cell nuclear factor is a transcriptional repressor essential for embryonic development. Front Biosci 6: D1186–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hummelke GC, Meistrich ML, Cooney AJ (1998) Mouse protamine genes are candidate targets for the novel orphan nuclear receptor, germ cell nuclear factor. Mol Reprod Dev 50: 396–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Braat AK, Zandbergen MA, De Vries E, Van Der Burg B, Bogerd J, et al. (1999) Cloning and expression of the zebrafish germ cell nuclear factor. Mol Reprod Dev 53: 369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Joos TO, David R, Dreyer C (1996) xGCNF, a nuclear orphan receptor is expressed during neurulation in Xenopus laevis. Mech Dev 60: 45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lan ZJ, Gu P, Xu X, Jackson KJ, DeMayo FJ, et al. (2003) GCNF-dependent repression of BMP-15 and GDF-9 mediates gamete regulation of female fertility. EMBO J 22: 4070–4081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chung AC, Cooney AJ (2001) Germ cell nuclear factor. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 33: 1141–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chung AC, Xu X, Niederreither KA, Cooney AJ (2006) Loss of orphan nuclear receptor GCNF function disrupts forebrain development and the establishment of the isthmic organizer. Dev Biol 293: 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Akamatsu W, DeVeale B, Okano H, Cooney AJ, van der Kooy D (2009) Suppression of Oct4 by germ cell nuclear factor restricts pluripotency and promotes neural stem cell development in the early neural lineage. J Neurosci 29: 2113–2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kehler J, Tolkunova E, Koschorz B, Pesce M, Gentile L, et al. (2004) Oct4 is required for primordial germ cell survival. EMBO Rep 5: 1078–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yeom YI, Fuhrmann G, Ovitt CE, Brehm A, Ohbo K, et al. (1996) Germline regulatory element of Oct-4 specific for the totipotent cycle of embryonal cells. Development 122: 881–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yoshimizu T, Sugiyama N, De Felice M, Yeom YI, Ohbo K, et al. (1999) Germline-specific expression of the Oct-4/green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgene in mice. Dev Growth Differ 41: 675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ko K, Tapia N, Wu G, Kim JB, Bravo MJ, et al. (2009) Induction of pluripotency in adult unipotent germline stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 5: 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ogawa T, Dobrinski I, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL (2000) Transplantation of male germ line stem cells restores fertility in infertile mice. Nat Med 6: 29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sabour D, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Hubner K, Ko K, Greber B, et al. (2011) Identification of genes specific to mouse primordial germ cells through dynamic global gene expression. Hum Mol Genet 20: 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, Tuveson DA, Grimm J, et al. (2007) Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature 445: 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hochedlinger K, Yamada Y, Beard C, Jaenisch R (2005) Ectopic expression of Oct-4 blocks progenitor-cell differentiation and causes dysplasia in epithelial tissues. Cell 121: 465–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barreto G, Borgmeyer U, Dreyer C (2003) The germ cell nuclear factor is required for retinoic acid signaling during Xenopus development. Mech Dev 120: 415–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hirose T, O'Brien DA, Jetten AM (1995) RTR: a new member of the nuclear receptor superfamily that is highly expressed in murine testis. Gene 152: 247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang G, Zhang YL, Buchold GM, Jetten AM, O'Brien DA (2003) Analysis of germ cell nuclear factor transcripts and protein expression during spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod 68: 1620–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang YL, Akmal KM, Tsuruta JK, Shang Q, Hirose T, et al. (1998) Expression of germ cell nuclear factor (GCNF/RTR) during spermatogenesis. Mol Reprod Dev 50: 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hummelke GC, Cooney AJ (2004) Reciprocal regulation of the mouse protamine genes by the orphan nuclear receptor germ cell nuclear factor and CREMtau. Mol Reprod Dev 68: 394–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Anderson R, Copeland TK, Scholer H, Heasman J, Wylie C (2000) The onset of germ cell migration in the mouse embryo. Mech Dev 91: 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ginsburg M, Snow MH, McLaren A (1990) Primordial germ cells in the mouse embryo during gastrulation. Development 110: 521–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lawson KA, Hage WJ (1994) Clonal analysis of the origin of primordial germ cells in the mouse. Ciba Found Symp 182: 68–84 discussion 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Molyneaux KA, Stallock J, Schaible K, Wylie C (2001) Time-lapse analysis of living mouse germ cell migration. Dev Biol 240: 488–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saitou M, Barton SC, Surani MA (2002) A molecular programme for the specification of germ cell fate in mice. Nature 418: 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Okumura LM, Lesch BJ, Page DC (2013) The ligand binding domain of GCNF is not required for repression of pluripotency genes in mouse fetal ovarian germ cells. PLoS One 8: e66062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Koubova J, Menke DB, Zhou Q, Capel B, Griswold MD, et al. (2006) Retinoic acid regulates sex-specific timing of meiotic initiation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 2474–2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Oulad-Abdelghani M, Bouillet P, Decimo D, Gansmuller A, Heyberger S, et al. (1996) Characterization of a premeiotic germ cell-specific cytoplasmic protein encoded by Stra8, a novel retinoic acid-responsive gene. J Cell Biol 135: 469–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Anderson EL, Baltus AE, Roepers-Gajadien HL, Hassold TJ, de Rooij DG, et al. (2008) Stra8 and its inducer, retinoic acid, regulate meiotic initiation in both spermatogenesis and oogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 14976–14980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Baltus AE, Menke DB, Hu YC, Goodheart ML, Carpenter AE, et al. (2006) In germ cells of mouse embryonic ovaries, the decision to enter meiosis precedes premeiotic DNA replication. Nat Genet 38: 1430–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mark M, Jacobs H, Oulad-Abdelghani M, Dennefeld C, Feret B, et al. (2008) STRA8-deficient spermatocytes initiate, but fail to complete, meiosis and undergo premature chromosome condensation. J Cell Sci 121: 3233–3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ogawa T, Arechaga JM, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL (1997) Transplantation of testis germinal cells into mouse seminiferous tubules. Int J Dev Biol 41: 111–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hubner K, Fuhrmann G, Christenson LK, Kehler J, Reinbold R, et al. (2003) Derivation of oocytes from mouse embryonic stem cells. Science 300: 1251–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Peters AH, Plug AW, van Vugt MJ, de Boer P (1997) A drying-down technique for the spreading of mammalian meiocytes from the male and female germline. Chromosome Res 5: 66–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu G, Hao L, Han Z, Gao S, Latham KE, et al. (2005) Maternal transmission ratio distortion at the mouse Om locus results from meiotic drive at the second meiotic division. Genetics 170: 327–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, et al. (2003) Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Research 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE (2002) Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Research 30: 207–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Global gene expression shows the Gcnf expression in different lines of mouse GSCs, compared with ESCs and germline-derived pluripotent stem cells (gPSCs).

(EPS)

Light microscopy of transplanted and non-transplanted GSCs into the testis. (A–B) Tomato lentivirus–infected GSCs before transplantation into the seminiferous tubules of germ cell–depleted busulfan-treated mice. (C–D) GSCs without Gcnf siRNA (controls, only with tomato lentivirus); note the red GSCs have colonized the tubules. (E–F) GSCs with Gcnf siRNA; note the red GSCs have colonized the tubules. (G–H) Non-transplanted testicular tubules, showing no recovery of germ cells in germ cell–depleted testes 3 months after treatment with busulfan. Note that the scale bars are 20 uM.

(TIF)

Expression of known germ cell markers and the newly identified genes in day-15 in vitro –derived PGCs. Real-time q-RT-PCR of pluripotency and known germ cell markers in (A) Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESC-derived PGCs and (B) Gcnf-deficient ESC-derived PGCs compared with ESCs. D denotes days. Real-time q-RT-PCR of the newly identified genes in (C) Oct4-GFP(ΔPE) ESC-derived PGCs and (D) Gcnf-deficient ESC-derived PGCs compared with ESCs.

(EPS)

Efficiency of shRNA transfection in GSCs. (A–B) FACS sorting plots, showing that more than 80% of the infected GSCs exhibited a positive tomato signal. (C) Depict the efficiency of shGcnf and showed the downregulation of gene in cells after 48 and 72 hours (75% downregulation of Gcnf after 72 hours).

(TIF)

Assay codes for TaqMan real-time q-RT-PCR.

(TIF)

List of primers used for SYBR Green real-time q-RT-PCR.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.