Abstract

Motion mitigation strategies are needed to fully realize the theoretical advantages of scanned ion beam therapy for patients with moving tumors. The purpose of this study was to determine whether a new four-dimensional (4D) optimization approach for scanned-ion-beam tracking could reduce dose to avoidance volumes near a moving target while maintaining target dose coverage, compared to an existing 3D-optimized beam tracking approach. We tested these approaches computationally using a simple 4D geometrical phantom and a complex anatomic phantom, that is, a 4D computed tomogram of the thorax of a lung cancer patient. We also validated our findings using measurements of carbon-ion beams with a motorized film phantom. Relative to 3D-optimized beam tracking, 4D-optimized beam tracking reduced the maximum predicted dose to avoidance volumes by 53% in the simple phantom and by 13% in the thorax phantom. 4D-optimized beam tracking provided similar target dose homogeneity in the simple phantom (standard deviation of target dose was 0.4% versus 0.3%) and dramatically superior homogeneity in the thorax phantom (D5-D95 was 1.9% versus 38.7%). Measurements demonstrated that delivery of 4D-optimized beam tracking was technically feasible and confirmed a 42% decrease in maximum film exposure in the avoidance region compared with 3D-optimized beam tracking. In conclusion, we found that 4D-optimized beam tracking can reduce the maximum dose to avoidance volumes near a moving target while maintaining target dose coverage, compared with 3D-optimized beam tracking.

Keywords: 4D optimization, ion therapy, carbon, proton therapy, motion, lung, beam tracking

1. Introduction

Ion beam therapy can reduce dose to healthy tissues near a cancer target and thus decrease the potential for severe side effects of radiation therapy, while maintaining tumor control, compared with x-ray and electron therapies, due to the physical energy loss characteristics of ions such as protons or carbon ions stopping in matter. In some cases, the additional degrees of freedom realized when using actively scanned ion beams instead of passively scattered ion beams can further improve normal tissue sparing. Actively scanned ion beam therapy typically uses fields composed of thousands of ion pencil beams, that is, narrow (few mm width) ion beams that are each approximately monoenergetic and monodirectional, to cover the lateral and longitudinal extent of a target volume. This approach can provide a high conformality and uniformity of target dose but requires a highly precise delivery system and accurate knowledge of the patient anatomy at the time of irradiation. Furthermore, heavier ions, such as carbon-12, exhibit increased relative biological effectiveness (RBE) for tumor control and cell killing near the Bragg peak, which may be advantageous either for treating radioresistant tumors or for exploiting the comparably low RBE found in the ion beam entrance channel to spare normal tissues upstream of the tumor (Schardt et al., 2010; Elsässer et al., 2010). To date, only a few approaches have been developed that could utilize this theoretically promising therapy for patients with moving thoracic tumors, such as lung cancer patients.

In order to treat patients with moving thoracic tumors using scanned ion beams, motion mitigation strategies are needed to ensure uniform dose coverage of the moving target and to best minimize dose to normal tissues near the moving target (Bert and Durante, 2011). Beam tracking is one of the more technically challenging motion mitigation strategies to implement for scanned ion beams but potentially provides a highly conformal dose to targets undergoing periodic motion. In this approach, individual ion pencil beams are magnetically steered throughout the patient respiratory cycle such that each individual ion-beam Bragg-peak position remains in the same local subvolume of the target during the entire respiratory cycle (Grözinger et al., 2004). The beam tracking system implemented at the GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung GmbH (GSI) in Darmstadt, Germany uses magnetic deflection to track lateral target motion and a fast (i.e., within a few ms) energy-degrading wedge system to compensate for anatomical changes in radiological depth of the target (Saito et al., 2009). Prior to treatment delivery, beam tracking offsets are calculated using both a four-dimensional computed tomogram (4DCT) and deformable image registration vectors, which register anatomic motion through the discrete temporal states of respiration represented by the 4DCT (Bert and Rietzel, 2007). By applying these lateral and longitudinal tracking offsets, ion pencil beams can be delivered in any phase of respiration since the ion beams track the tumor for the entire respiratory cycle. In addition, dosimetric target margins for scanned ion beam tracking theoretically remain as sharp and conformal as those possible for stationary anatomy. The previously-proposed, 3D-optimized-beam-tracking approach of Bert and Rietzel (2007) achieved adequate target dose coverage for some patients but did not provide a general solution for patients with tumors that deform or rotate significantly during respiration. To elucidate, in their approach, particle numbers were optimized using a single 3D reference phase of the 4DCT, e.g., end-exhale. Consequently, 4D dose was deteriorated somewhat, even with perfect geometric tracking of target motion, since off-axis dose contributions from each ion beam can distort in the presence of complex tissue motion (van de Water et al., 2009). To address this problem, Lüchtenborg et al. (2011) proposed a real-time 4D dose compensation method for scanned ion beam tracking that improves target dose coverage by adapting particle numbers in real-time based on the motion status of the target during the delivery of each ion beam. Recently, Graeff et al. (in press) devised another new strategy for treating a moving target, which irradiated different sections of the target volume in predetermined motion phases and used 4D optimization to achieve uniform target dose coverage. Importantly, none of these proposed beam-tracking approaches have been applied to patient treatment, and, more generally, the ideal method to apply scanned ion beam therapy to patients with moving tumors, if one even exists, is not yet known. Based on the approach of Lüchtenborg et al. (2011), we were inspired to investigate 4D optimization as a strategy to further improve target dose coverage and potentially control dose to healthy tissue for scanned ion beam tracking, which their study did not address. Whereas many motion mitigation strategies attempt to eliminate or reduce the impact of time and motion as factors in therapy, we sought to exploit time and motion as potential advantages in therapy using 4D optimization.

Several studies have reported 4D-optimization strategies for photon therapy. Zhang et al. (2004) incorporated respiratory motion data into optimization of photon tomotherapy plans and demonstrated improved target dose conformity. Trofimov et al. (2005) developed four new approaches to optimize intensity-modulated photon fields for lung and liver patients with moving tumors. Nohadani et al. (2010) reported another 4D optimization approach for photon therapy that improved dose coverage compared to beam gating for lung cancer patients and reduced dose to healthy lung and was also more robust to irregular breathing than beam gating. Chin and Otto (2011) further demonstrated in phantom studies that 4D optimization can be applied to volumetric modulated arc therapy to spare avoidance volumes near a moving target. These studies suggest that the added degree of freedom, namely time, facilitates the optimization process and yields improved target dose coverage and to spare avoidance volumes near a moving target. However, to our knowledge, 4D optimization for ion beam therapy has only been recently reported (Graeff et al., in press), and the strategy that we propose here has not been previously reported in the literature.

The purpose of our study was to propose a new beam tracking approach using 4D optimization for scanned ion therapy of moving tumors. We tested the working hypothesis that 4D-optimized scanned ion beam tracking can reduce dose to avoidance volumes outside a moving target compared with 3D-optimized scanned carbon beam tracking while maintaining adequate target dose coverage. We also sought to demonstrate that delivery of 4D-optimized scanned ion beam tracking is technically feasible. To achieve these goals, we simulated our proposed approach using a research treatment planning system for both a simple 4D geometrical phantom and for a complex anatomic phantom using a thoracic 4DCT of a lung cancer patient. Furthermore, we irradiated moving films using 3D- and 4D-optimized scanned carbon-ion beam tracking to experimentally validate our simulation studies.

2. Methods

2.1. 4D Optimization

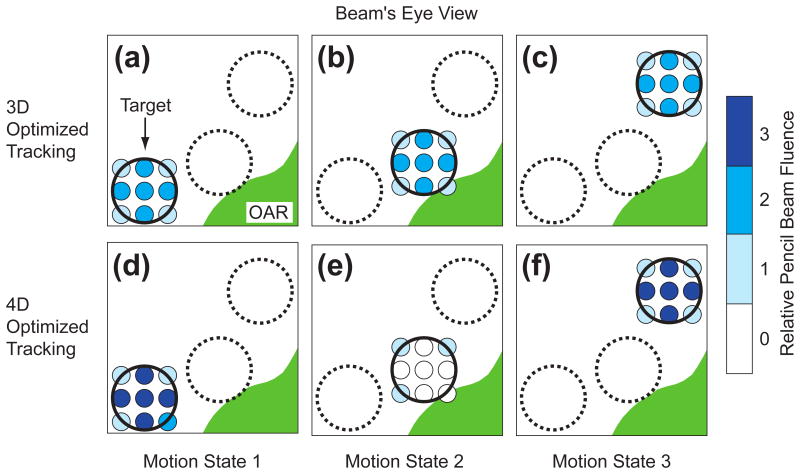

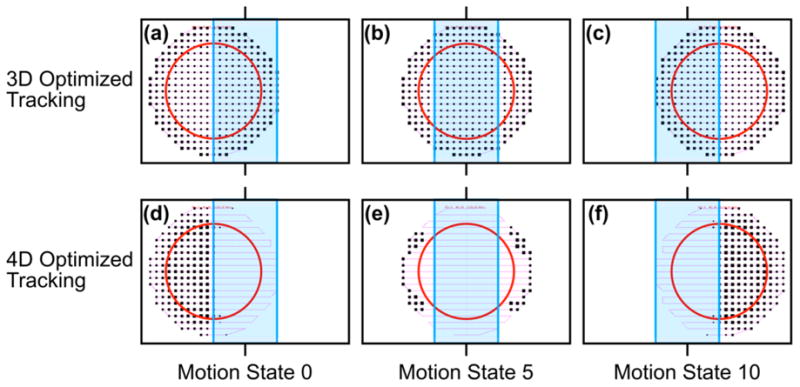

In this work, we propose a 4D-optimization approach for scanned ion beam tracking therapy. Our approach involves planning of a 4D field composed of ion pencil beams, each with a unique geometric position, energy, and particle number (i.e., number of particles incident on the patient in that pencil beam), determined for individual motion states. Figure 1 compares the proposed approach for 4D-optimized scanned ion beam tracking with a previously proposed approach using 3D-optimized scanned ion beam tracking. In essence, our approach seeks to reduce dose to avoidance volumes near the moving target while preserving adequate target coverage. This was accomplished by optimizing the particle numbers for each pencil beam for each motion state. We implemented our approach in the TRiP4D research treatment planning system (TPS) code for scanned ion therapy (Krämer et al., 2000; Richter et al., 2013) using the C programming language. The TPS already had the capability to calculate 4D dose distributions and plan beam-tracking offsets. The implementation of our proposed approach required modifications and extensions to the optimization routines to incorporate 4DCT data, deformable image registration vectors, and beam tracking offsets that were necessary to enable optimization of a 4D field. It should be noted that, for the purposes of this study, we optimized absorbed dose; further TPS development will be needed to allow 4D-optimization of RBE-weighted dose.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing comparing 4D- versus 3D-optimized scanned ion beam tracking in beam's eye view. A circular target (black) moves between three motion states. For 3D-optimized tracking (a, b, and c) pencil beams (smaller blue circles) track the target motion and deliver identical particle fluence for each motion state. For 4D-optimized tracking, fluence is reduced for Motion State 2 (e) when the target is closest to the organ at risk (green). To compensate, fluence must be increased for pencil beams in Motion States 1 and 3 when the target is furthest from the organ at risk (d and f). Relative fluence is indicated by the shade of blue for each pencil beam.

Our treatment planning workflow for 4D-optimized scanned ion beam tracking included the sequence of steps below. The sequence was used for planning treatments of the simple phantom and the thorax.

A 3D scanned ion field was planned to cover a 3D representation of the 4D target volume in a reference motion state, with Bragg peaks for each pencil beam evenly spaced throughout the target volume. This step required a 3D reference-state image extracted from a 4DCT that represented the patient anatomy in the reference state and target contours to determine the necessary energies and lateral coordinates of ion pencil beams.

Particle numbers were optimized for the 3D scanned ion field to provide uniform dose throughout the target for the reference motion state.

To plan beam tracking, 4DCTs and corresponding deformable image registration vectors were used to calculate lateral and longitudinal beam-tracking offsets for each pencil beam for each motion state, so that each pencil beam would track changes in target position and radiological depth during treatment. Thus, the treatment plan at this stage was composed of a 3D field and a 4D look-up table of tracking offsets (Bert and Rietzel, 2007).

As the starting condition for the 4D field, the 3D field, created in Steps 1 and 2, was copied for each of M motion states, corresponding to states of the 4DCT, to produce a 4D field. Tracking offsets for each pencil beam for each motion state were included in the 4D field description. Initially, particle numbers N for each pencil beam in all motion states of the 4D field were identical to those in the 3D field, though scaled uniformly by 1/M.

-

For 4D optimization of the particle numbers N in the 4D fields, a dose correlation matrix A was calculated that contained the dose contribution, per incident particle number (nijk), for each ion pencil beam (i) in each motion state (j) for each field (k) to each voxel (p) in the target and avoidance volumes. To calculate the dose correlation matrix elements (aijkp) of A, 4D pencil beam dose calculations were performed similarly to 3D pencil beam dose calculations except that (1) individual voxel coordinates, defined in a reference motion state, for the target and avoidance volumes were transformed for non-reference motion states using deformable image registration vectors, (2) individual ion pencil beams were offset by their tracking offsets that were determined in Step 3, and (3) the appropriate 3DCT state from the 4DCT was used in dose calculation. The resulting dose correlation matrix was used to calculate 4D dose (D) to the pth (moving) voxel by

(1) where Ljk is the number of pencil beams in an individual motion state j for a given field k. B is the number of fields used, for example, with different gantry angle or couch angle. In this study, we only used single fields (B = 1), but our TPS implementation enables multi-field intensity-modulated optimization.

-

An objective function χ2(N) was defined to express differences between the prescribed and actual dose to the target (T) and to penalize dose to avoidance volumes (V) above a given threshold dose for each avoidance volume (Horcicka et al., 2013).

(2) where DRx was the prescribed target dose and the terms wT and wV were adjustable parameters to weight the objective function to preferentially greater emphasize either prescribed target dose coverage or avoidance volume dose exceeding a maximum allowed value DMax, as desired. The Heaviside step function Θ served to exclude voxels receiving a dose below a user specified maximum dose limit DMax from adding penalty to the objective function. Specifying DMax for avoidance volumes near the target allowed fine control over tradeoffs between the competing objectives of uniform target dose coverage and minimal dose to avoidance volumes.

Conjugate gradient minimization (Fletcher and Reeves, 1964) was used to solve for particle numbers N in the 4D scanned ion field that minimized the objective function.

2.2. Water Phantom Study

To compare our 4D-optimized scanned ion beam-tracking approach against an existing 3D-optimized scanned ion beam-tracking approach, we designed a test case that utilized a simple water-box phantom containing a moving spherical target and a static rectangular solid avoidance volume. The simple phantom consisted of two rectangular-solid slabs of water. A stationary, proximal slab contained a rectangular solid avoidance volume, upstream of the target. A distal slab contained a 3-cm spherical target volume and oscillated along the x-axis, perpendicular to the beam direction, with sinusoidal motion with 2-cm peak-to-peak amplitude and a period of 4 s. We designed this phantom to allow two distant motion states in which beams could deliver dose to portions of the target and while missing the avoidance volume.

For treatment planning, voxelized 4DCT data and contours were generated to represent this phantom, and corresponding image registration vectors were created to describe the sinusoidal motion of the phantom for 11 discrete motion states. The motion states were equally spaced in distance between the minimal and maximal displacements of the spherical target volume. Using the TPS, a single scanned carbon ion field was designed to irradiate the spherical target uniformly with 1 Gy, with the beam first passing through the stationary slab containing the avoidance volume. The positions of the Bragg peaks of individual pencil beams were distributed throughout the target with 2 mm lateral spacing and 3 mm water-equivalent depth spacing. The beams were focused to approximately 6 mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) spot size each at the center of the target. A 3-mm ripple filter was used to broaden the width of the carbon Bragg peaks along the depth axis (Weber and Kraft, 1999).

The 3D-optimized beam tracking plan was prepared using only steps 1-3 in the sequence described in Section 2.1. These plans comprised a 3D field and a list of tracking offsets for each pencil beam for each motion state. We did not restrict dose to the avoidance volume in 3D optimization for this water phantom case, since that objective directly conflicted with the objective of uniform target dose for 3D optimization in the static reference motion state. For 3D optimization, our solution was considered to have converged and optimization was stopped once the relative change in our objective function after each successive iteration dropped below 10-3. The 4D-optimized scanned carbon tracking plan was prepared according to steps 1-7 in the sequence described in Section 2.1. For 4D optimization objectives, we included a uniform target dose of 1 Gy (wT = 1) and a maximum dose to the avoidance volume of 0.01 Gy (wV = 0.01). To prevent the occurrence of overly high doses in regions outside the target and avoidance volume, we also added a thin avoidance volume layer, 2-mm depth-thickness at 2-cm depth, throughout the entire proximal slab, with a maximum allowed dose of 1 Gy (wV = 1).

We investigated the rate of convergence of the 4D objective function as a function of the number of iterations. Based on our initial findings, we replaced the iteration stopping criteria discussed above with a fixed number (1000) of iterations. We will return to this topic in Section 3.1. 4D dose calculations were performed for both 3D- and 4D-optimized scanned carbon beam tracking for the moving phantom. A 3D dose calculation was also performed for a static reference case without motion.

In summary, our water phantom study compared calculated dose to the target and avoidance volumes for (1) static 3D irradiation with the target fixed in the reference motion state, (2) 3D-optimized scanned carbon beam tracking, and (3) 4D-optimized scanned carbon beam tracking. 4D dose distributions were transformed to the reference motion state for dosimetric analysis. Dose distributions were visualized using 2D dose color wash planes and quantitatively compared using statistics from analyses of dose-volume histograms.

2.3. Lung Cancer Patient Study

In order to demonstrate that our 4D-optimized beam tracking approach could optimize 4D scanned carbon fields for a complex thoracic anatomy and moving organs, we tested our approach using a 4DCT of a lung cancer patient. The 59-year-old woman in our study was diagnosed with stage IV, T2/N2/M1, non-small-cell lung cancer and a 4.5-cm primary tumor in the left lower lobe near the heart. Peak-to-peak tumor motion amplitude was approximately 2.5 cm. She previously received x-ray radiotherapy at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (UTMDACC) (Houston, TX). Prior to her treatment, 4DCT image data were acquired with a 16-slice CT scanner (Philips, Mx8000 IDT, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and binned into 10 phases of the respiratory cycle with equal duration (Keall et al., 2004). Data for this patient were collected under a retrospective research protocol approved by the UTMDACC Institutional Review Board. All protected health information was removed from our copy of the electronic medical record.

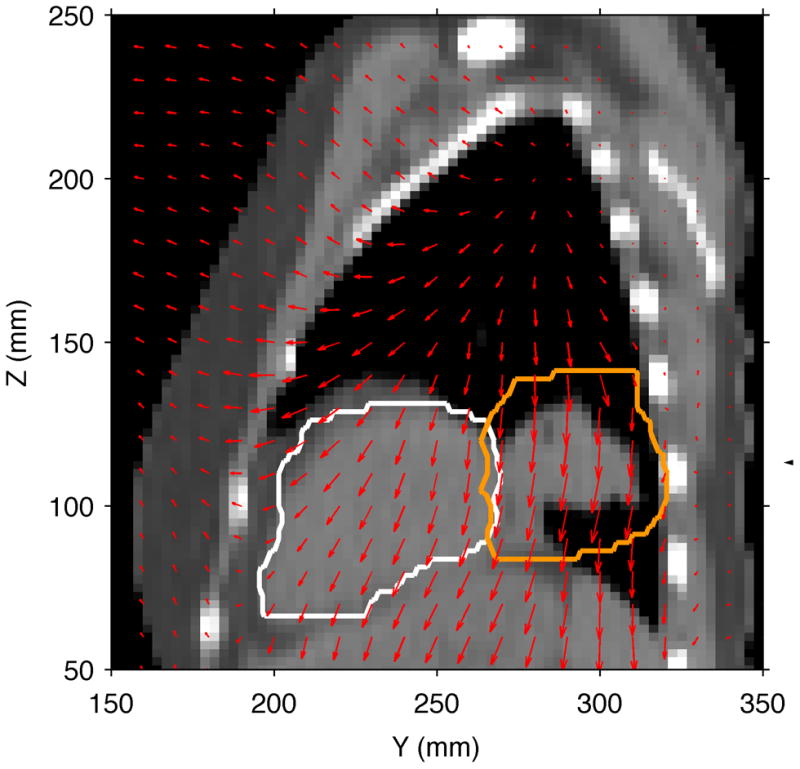

In order to plan beam tracking and to perform 4D dose calculations, deformable 4D image registration vectors were calculated from the 4DCT data using the Plastimatch software system using B-splines (Shackleford et al., 2010). Figure 2 shows the deformable image registration vectors overlaid on a CT slice for the reference phase at end-exhale, qualitatively illustrating the extent of organ motion.

Figure 2.

Sagittal CT slice for the lung cancer patient in the reference motion state at end-exhale. The CTV is indicated by the orange contour (right), and the heart contour is shown in white (left). The overlaid red vectors indicate the YZ components of the deformable image registration vectors and show the movement of tissue to a different motion state at full-inhale.

Using the TPS, we designed a single posterior-to-anterior scanned ion field to irradiate the clinical target volume (CTV). Although a lone field would most likely not be used clinically, we chose this to facilitate a severe test of the dosimetric performance of our algorithm at the distal target edge near the heart. For a reference motion state at end-exhale, positions of the carbon pencil beam Bragg peaks were planned to cover the CTV with a uniform 2-mm lateral spacing and a focal size of 6-mm FWHM. We used a 3-mm water-equivalent spacing between isoenergy slices and a corresponding 3 mm ripple filter. Particle numbers for each pencil beam were initially optimized in 3D to provide 100% of the prescribed dose to the CTV (wT = 1) and zero dose to the heart (wV = 10). 3D optimization was stopped once the relative change in the objective function dropped below 10-3 between each iteration. Where the CTV contours overlapped the heart volume, that volume was treated as CTV. After planning a 3D field to irradiate the target in the reference motion state, beam tracking offsets were computed for each pencil beam in each motion state using 4D deformable image registration vectors and 4DCT data, as described in steps 1-3 of the sequence in Section 2.1. For 4D-optimized beam tracking, we performed steps 1-7 in Section 2.1. For 4D optimization, we specified criteria of uniform CTV dose coverage (wT = 1) and a limit of zero dose to the heart (wV = 10). As in the water phantom study, we investigated convergence of the 4D objective function as a function of the number of iterations. Based on this, we used 1000 iterations with no stopping criteria.

We computed 4D dose distributions in the lung patient for static irradiation, 3D-optimized beam tracking, and 4D-optimized beam tracking. All 4D dose distributions were transformed to a 3D reference state at end-exhale for dosimetric analysis. Dose distributions were visualized using 2D dose color wash planes and dose volume histograms. Quantitative comparisons utilized dose-volume summary statistics. For the lung CTV, we chose the dose-volume metrics of V95 to quantify target dose coverage, V107 to quantify target overdosage, and D5-D95 to quantify target dose homogeneity. To define these metrics, V95 was the percentage of tumor volume receiving at least 95% of the prescribed dose, V107 was the percentage of tumor volume receiving at least 107% of the prescribed dose, and D5-D95 was the difference between D5, the minimum dose to the 5% of tumor volume receiving the highest dosage, and D95, the minimum dose to the 95% of tumor volume receiving the highest dosage. For the heart, we analyzed the mean and maximum dose values. To investigate the sensitivity of our approach to interfractional motion changes and differences in breathing pattern, we also simulated treatment for both 3D-optimized beam tracking and 4D-optimized beam tracking using an initial 4DCT (acquired at Week 0) for treatment planning and a later 4DCT (acquired at Week 1) for treatment delivery. We calculated the effects of these motion changes on dose-volume statistics for the lung CTV and the heart.

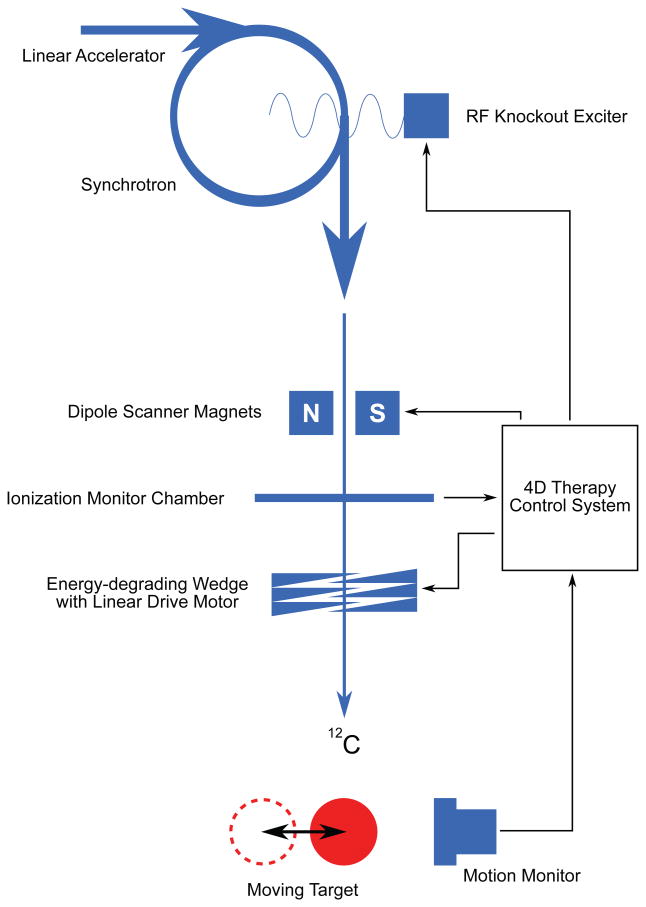

2.4. Validation Experiment

To demonstrate the feasibility of delivering 4D-optimized beam tracking therapy and to validate the findings of our simulation studies, we irradiated a 4D phantom with a scanned carbon beam and measured tracking performance using radiographic films. The 4D treatment delivery system for scanned ion beam tracking is depicted schematically in Figure 3. Similar to the water-box phantom described in Section 2.2, we designed a disk-shaped moving target with 3-cm diameter and sinusoidal motion with 2-cm amplitude and 4-s period perpendicular to the beam central axis. We planned a single isoenergy layer of carbon ion pencil beams with 2-mm lateral spacing to deliver uniform dose to the moving target and minimal dose to the static avoidance volume upstream of the target.

Figure 3.

Beam tracking system for scanned ion therapy implemented at GSI. The ion beam is produced by linear and synchrotron acceleration and extracted by a radiofrequency (RF) knockout exciter. Dipole scanner magnets steer the ion pencil beams laterally to achieve target coverage and to track target motion. A system of acrylic wedges mounted on linear drive motors modifies the range of individual pencil beams to track changes in radiological depth of the target (Saito et al., 2009). A motion monitoring system provides feedback to the 4D therapy control system, which transmits precomputed beam tracking offsets for each pencil beam and each motion state to the scanner magnets and wedge system, so that each pencil beam follows the target motion. The ionization monitor chamber detects the number of particles delivered for each pencil beam in a given motion state. Furthermore, the RF knockout exciter is used to gate the beam as needed for each motion state.

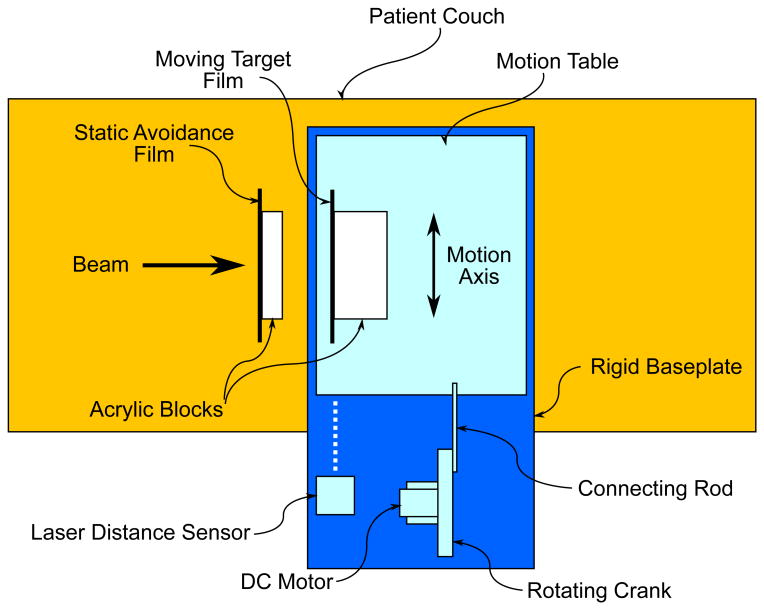

Experimentally, this case was represented by a radiographic film (Eastman Kodak, X-OMAT V, Rochester, USA) placed, in its jacket, on a motorized table at isocenter on the patient couch and another film placed upstream of the motorized table, which did not move. A laser distance indicator was used to detect target motion for our 4D treatment control system. Our 4D TCS includes a continuously running software loop that processes the digitized signal from the laser distance indicator and determines the motion state using an amplitude-based detection algorithm (Lüchtenborg et al., 2011). Our experimental setup is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Top view of our experimental setup for the 4D-optimized beam tracking experiment. Our phantom consisted of 2 acrylic blocks that held radiographic films. The first phantom piece was positioned stationary upstream of the target. The second moving target phantom piece was mounted on a motion table designed for sinusoidal 1D motion with 2-cm amplitude, driven by an electric DC motor. A laser distance sensor monitored the position of the motion table and transmitted a signal to the 4D treatment control system, which determined the motion state of the phantom for 4D treatment delivery.

We delivered our 4D scanned carbon fields to the films using a sequential gating technique. For example, all particles prescribed for motion state 1 were delivered before any particles were delivered for motion state 2. In the case that a motion state change occurred before irradiation was finished, the particle spill was gated by stopping the radiofrequency knockout exciter until the motion table returned to the unfinished motion state and the spill extraction was resumed. In this manner, we irradiated scanned carbon ion treatment plans using both 3D-optimized beam tracking and 4D-optimized beam tracking. Films were processed and digitally scanned using standard methods (Spielberger et al., 2003), and we analyzed the film exposure, quantified as optical density, in both the moving target region and the avoidance region of the films for both 3D- and 4D-optimized beam tracking.

3. Results

In general, we observed that 4D optimization performed as expected. The additional degrees of freedom in the 4D approach (i.e., the particle numbers for each pencil beam for each motion state) yielded dosimetric advantages, such as reduced dose to avoidance volumes and superior uniformity in the CTV.

3.1. Water Phantom Study

Carbon ion particle numbers N were determined for 3D- and 4D-optimized beam tracking. Fluence maps for a single energy-slice are shown in Figure 5. As expected, particle numbers were reduced by 4D optimization for certain motion states for pencil beams that passed through the proximal static avoidance volume to reach the distal moving target volume. To compensate this, particle numbers were increased using 4D optimization for those motion states that allowed pencil beams to irradiate the target without passing through the proximal avoidance volume.

Figure 5.

Beam's eye views of carbon ion scan patterns, i.e., fluence maps, for a single iso-energy layer (201.65 MeV/u) comparing 3D optimized beam tracking (a,b,c) and 4D optimized beam tracking (d,e,f). The ion scan path (thin pink line), stationary avoidance volume (blue rectangle) and moving target (red circle) are shown for exemplary motion states 0 (a, d), 5 (b, e), and 10 (c, f). Relative particle numbers for each pencil beam are indicated by the size of the black squares.

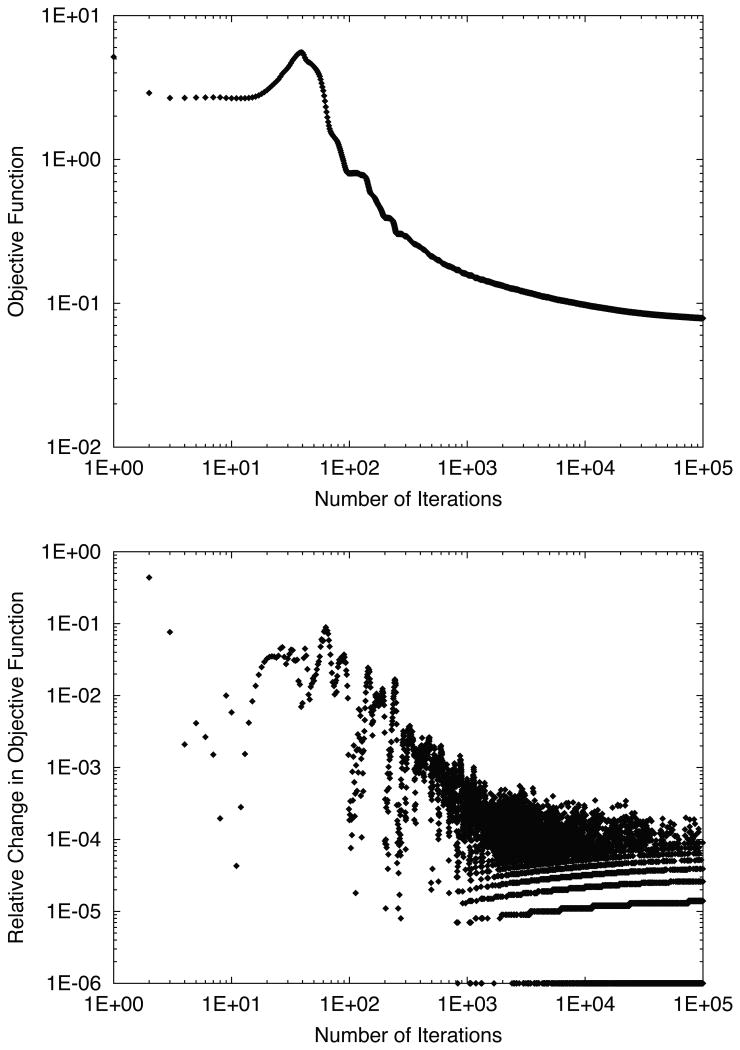

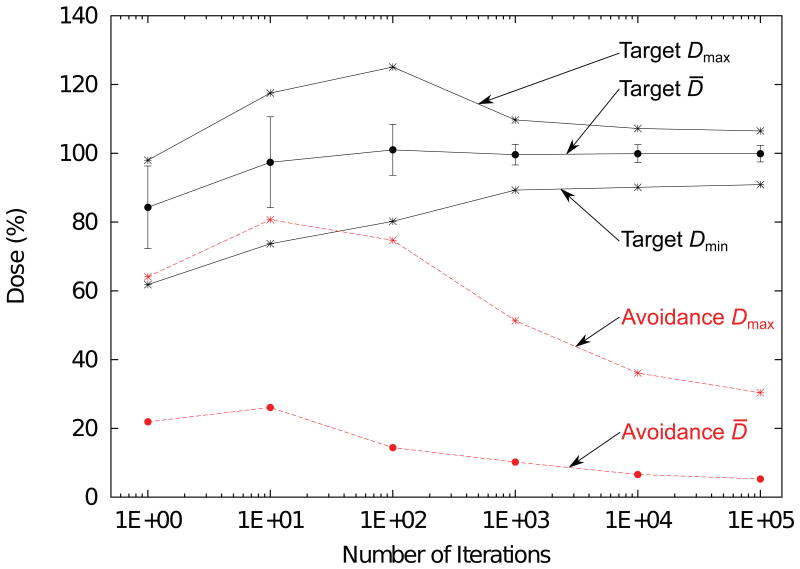

In 4D optimization, the evaluation of the objective function χ2(N) is shown as a function of iteration number in Figure 6. The erratic shape of the relative change in objective function in early iterations led us to abandon our typical criteria for terminating optimization, which was to stop when the relative change dropped below 10-3. Instead, we estimated from these plots that the relative change in the objective function became stable and remained below 10-3 near 1000 iterations. Thus we used 1000 iterations of 4D optimization without any abort criteria for the rest of our study, and we visually confirmed that the objective function did not worsen by neglecting the typical stopping criteria. To better visualize dosimetric improvements as a function of iteration number, 4D dose distributions are plotted for various iteration numbers in Figure 7. Due to our choice of optimization constraints, the target dose was drastically decreased in the first iteration to spare dose to the avoidance volume. However, after a large number of iterations the target dose coverage was restored, even though a reduction of dose to the avoidance volume was maintained.

Figure 6.

Objective function (top) and relative change in objective function (bottom) versus number of iterations for 4D-optimized beam tracking for the water phantom. An initial increase of the objective function was in early iterations, suggesting the presence of a local minimum, followed by a gradual minimization continuing up to 105 iterations.

Figure 7.

Target and avoidance volume dose statistics versus number of iterations for 4D-optimized beam tracking for the water phantom. Target mean (D̄), standard deviation (error bars), minimum (Dmin), and maximum dose (Dmax) are shown by the black markers connected by solid lines. Avoidance volume mean and maximum dose are shown by the red markers connected by dashed lines. During the first 10 iterations, dose is increased both to the target and the avoidance volume. After the target dose stabilizes near iteration 1000, a continued reduction in maximum dose to the avoidance volume is seen even up to 100,000 iterations.

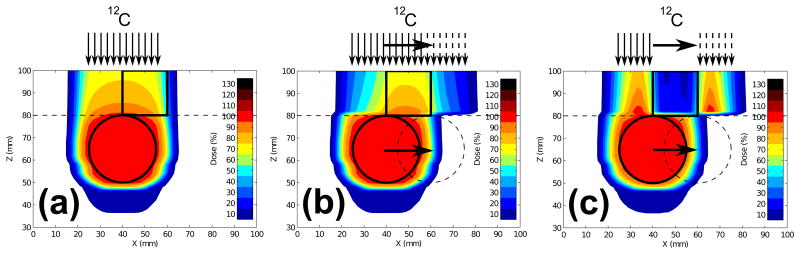

Figure 8 plots 2D dose color wash planes comparing 4D-optimized beam tracking against 3D-optimized beam tracking, along with a static irradiation. Dose to the avoidance volume for 4D-optimized beam tracking was greatly reduced, mean dose decreased by 70% and maximal dose decreased by 53%, compared to the corresponding values from the 3D-optimized plan. Dose statistics for the moving sphere and avoidance volume are presented in Table 1 for each treatment plan. For all treatment plans, dose coverage to the moving target was nearly identical. In the avoidance volume, dose distributions for 3D-optimized beam tracking and static irradiation were similar, though the dose distribution for 3D-optimized tracking appeared generally blurred in the lateral direction. This was expected because the carbon-ion beams were laterally tracking the moving target during irradiation.

Figure 8.

2D dose cuts for the moving sphere target in a water phantom with a static proximal avoidance volume. 4D dose distributions were calculated for (a) 3D-optimized carbon static plan for a non-moving target in the reference motion state, (b) 3D-optimized carbon beam tracking plan for a moving target, and (c) 4D-optimized carbon beam tracking plan for a moving target. Sphere target shown in the reference position (solid circle) and at maximal displacement (dashed circle). The proximal avoidance structure (solid square) and water above Z = 80 mm (dashed line) did not move. Illustrations of carbon pencil beam fluence for each case are shown above the phantoms to demonstrate: (a) pencil beams do not move, (b) pencil beams track the lateral motion of the sphere target, but fluence for each pencil beam is identical to the static 3D plan, and (c) pencil beams track the lateral motion of the target with pencil beam fluence optimized for each motion state to best spare the avoidance structure and maintain target coverage.

Table 1.

Dose and volume statistics comparing 3D optimized static delivery, 3D optimized beam tracking (3DOBT), and 4D optimized beam tracking (4DOBT) for both the water phantom and lung cancer patient studies. Data reported as percentages. Difference calculated as 100% × (4DOBT - 3DOBT) / 3DOBT.

| Study | Volume | Metric | Static | 3DOBT | 4DOBT | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phantom | Target | D̄ | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 0 |

| σD | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | +58 | ||

| Dmin | 98.3 | 98.3 | 97.3 | -1 | ||

| Dmax | 101.2 | 101.2 | 101.5 | 0 | ||

| V95 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0 | ||

| V107 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | ||

| D5 - D95 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | +1 | ||

| Avoidance | D̄ | 23.8 | 26.1 | 7.7 | -71 | |

| Dmax | 91.5 | 89.4 | 42.2 | -53 | ||

| Patient | CTV | D̄ | 99.9 | 95.4 | 100.0 | +5 |

| σD | 1.9 | 12.0 | 0.9 | -93 | ||

| Dmin | 34.2 | 37.9 | 54.7 | +44 | ||

| Dmax | 114.5 | 126.7 | 108.9 | -14 | ||

| V95 | 99.7 | 50.4 | 99.9 | +98 | ||

| V107 | 0.2 | 19.5 | 0.1 | -100 | ||

| D5 - D95 | 2.0 | 38.7 | 1.9 | -95 | ||

| Heart | D̄ | 7.0 | 6.9 | 7.1 | +3 | |

| Dmax | 104.7 | 119.4 | 103.8 | -13 |

3.2. Lung Cancer Patient Study

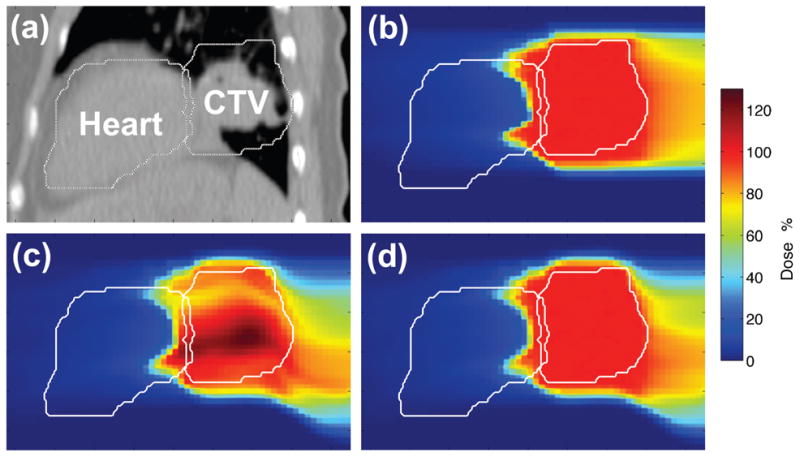

For the lung cancer patient simulation, we observed a decrease in the maximal dose to the avoidance volume (i.e., the heart) using 4D-optimized beam tracking instead of 3D-optimized beam tracking. Interestingly, 4D optimization provided highly uniform CTV coverage, similar to that for a static irradiation and superior to that for 3D-optimized beam tracking.

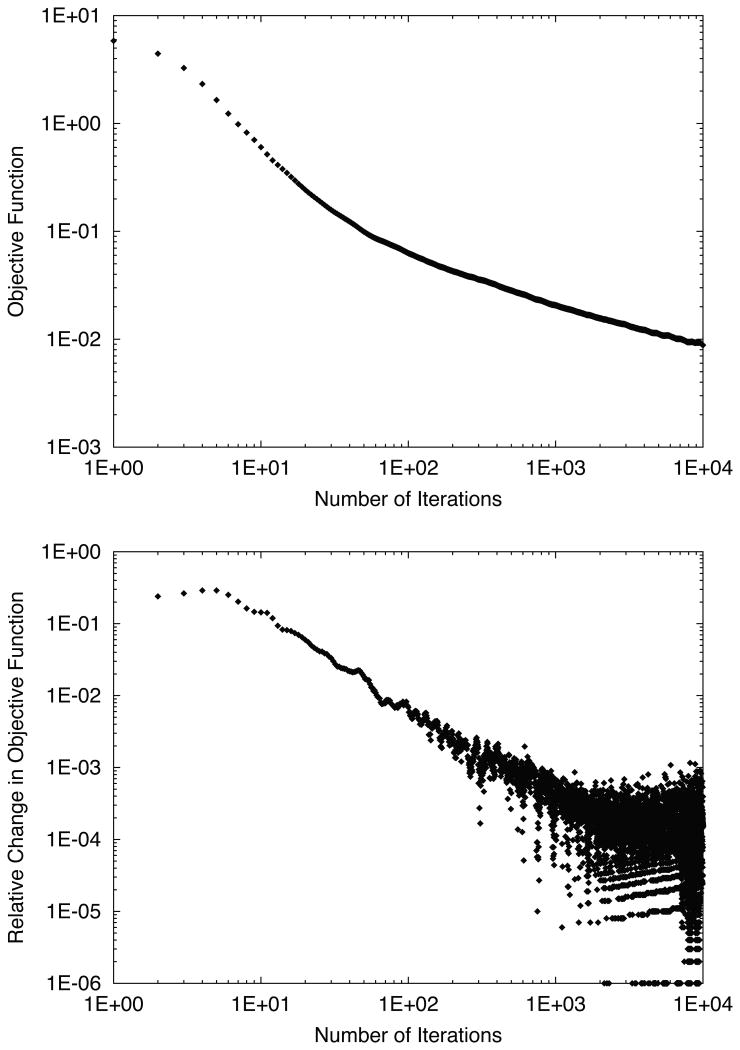

Figure 9 plots the evaluation of the objective function χ2(N) shown as a function of iteration number. Similar to the water phantom results (cf. Figure 6), we observed from these plots that the relative change in the objective function was somewhat erratic but seemed to fall consistently below 10-3 near 1000 iterations. Thus 1000 iterations were used for our study.

Figure 9.

Objective function (top) and relative change in objective function (bottom) versus number of iterations for 4D-optimized beam tracking for the lung patient.

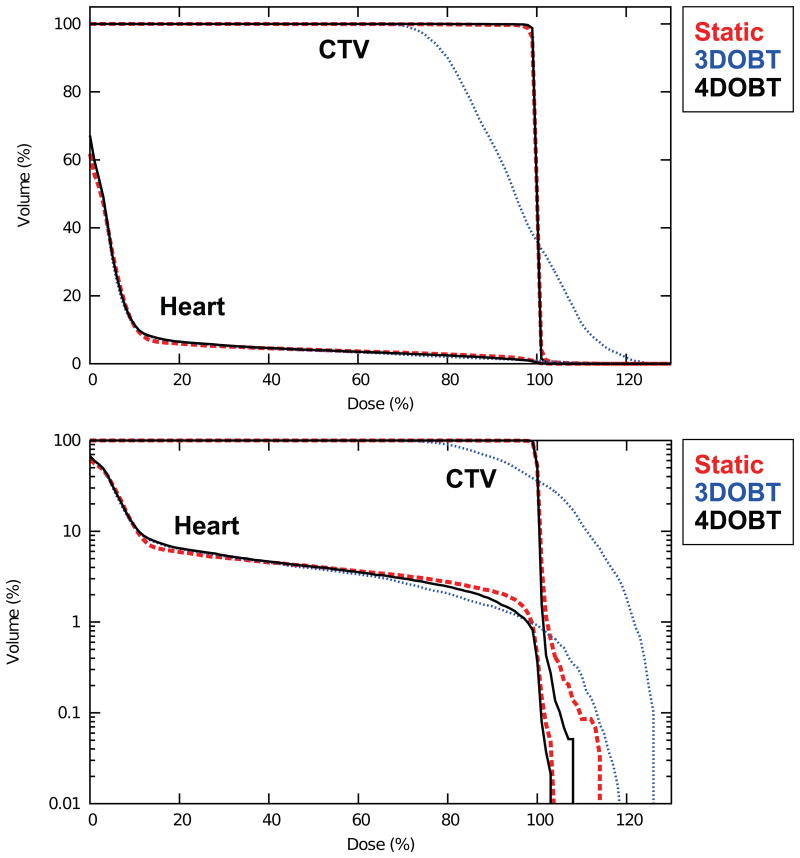

Figure 10 plots dose planes comparing 4D-optimized tracking against 3D-optimized tracking and static irradiation. The same data are shown in dose-volume histogram (DVH) form in Figure 11. For the static irradiation, the target dose distribution was approximately uniform throughout the CTV. 3D-optimized beam tracking provided a dose distribution that remained conformal to the geometric target boundary. However, degradation of dose uniformity was observed inside the target with regions of overdosage and underdosage. In particular, a region of overdosage extends distally beyond the CTV into the heart. This non-ideal dose coverage was likely caused by a partial failure of the 3D-optimized tracking to compensate for dosimetric effects of rotating or deforming tissues or for changes in the scattering properties of material upstream of the target.

Figure 10.

Sagittal cuts showing (a) CT image of lower thorax, (b) 3D dose for the 3D-optimized carbon static plan ignoring motion, (c) 4D dose for the 3D-optimized beam tracking plan, (d) 4D dose for the 4D-optimized carbon beam tracking plan. All 4D dose distributions were transformed to the reference motion state at end-exhale for analysis. Note the increased uniformity of CTV dose using 4D-optimized beam tracking (d) instead of 3D-optimized beam tracking (c).

Figure 11.

4D cumulative DVHs for the lung CTV and the heart shown in linear (top) and semilog (bottom) scales comparing (1) 3D-optimized static plan (dashed red line), (2) 3D-optimized beam tracking (dotted blue line), and (3) 4D-optimized beam tracking (solid black line). 4D-optimized beam tracking appears similar to the static plan with more uniform target dose coverage and slightly reduced maximal dose to the heart, compared with 3D-optimized beam tracking.

Our findings regarding sensitivity to interfractional motion changes for the lung patient are presented in Table 2. Target dose coverage (V95) decreased by 12% and 11% for 3D-optimized beam tracking and 4D-optimized beam tracking, respectively, due to changes in organ motion between Week 0 and Week 1. At Week 1, the target dose distribution was better for 4D-optimized beam tracking than for 3D-optimized tracking by all metrics, but differences in dose to the heart became less evident.

Table 2.

Effect of interfractional motion changes on dose-volume statistics for 3D-optimized beam tracking (3DOBT) and 4D-optimized beam tracking (4DOBT) for the lung cancer patient. The 4DCT acquired at Week 0 was used for treatment planning in all cases, but the 4DCT used for dose calculation was varied using either Week 0 or Week 1 as indicated. Data reported as percentages. Difference calculated as 100% × (Week 1 - Week 0) / Week 0.

| Plan | Volume | Metric | Week 0 | Week 1 | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3DOBT | Target | D̄ | 96.2 | 93.8 | -2 |

| σD | 10.3 | 11.3 | +10 | ||

| Dmin | 37.5 | 27.2 | -27 | ||

| Dmax | 123.7 | 119.6 | -3 | ||

| V95 | 51.3 | 45.2 | -12 | ||

| V107 | 17.7 | 13.3 | -25 | ||

| D5 - D95 | 33.3 | 34.1 | +2 | ||

| Avoidance | D̄ | 6.9 | 11.3 | +63 | |

| Dmax | 115.6 | 116.0 | 0 | ||

| 4DOBT | CTV | D̄ | 99.9 | 97.8 | -2 |

| σD | 0.9 | 6.2 | +595 | ||

| Dmin | 54.2 | 29.0 | -46 | ||

| Dmax | 109.7 | 108.4 | -1 | ||

| V95 | 99.9 | 88.9 | -11 | ||

| V107 | 0.1 | 0.1 | +67 | ||

| D5 - D95 | 1.8 | 13.4 | +627 | ||

| Heart | D̄ | 7.1 | 11.8 | +66 | |

| Dmax | 104.0 | 114.8 | +10 |

In summary, 4D-optimized beam tracking improved target dose uniformity, compared to 3D-optimized beam tracking (i.e., D5-D95 was reduced by 95%). In addition, by using 4D-optimized tracking we observed a 13% decrease in maximum dose to the heart, compared to 3D-optimized tracking (cf. Table 1). Analysis of the organ motion seen in the deformable image registration map (see Figure 2) suggests that similar motion between the lung CTV and the heart restricted our ability to reduce dose to the heart as greatly as that possible in our water phantom study.

3.3. Validation Experiment

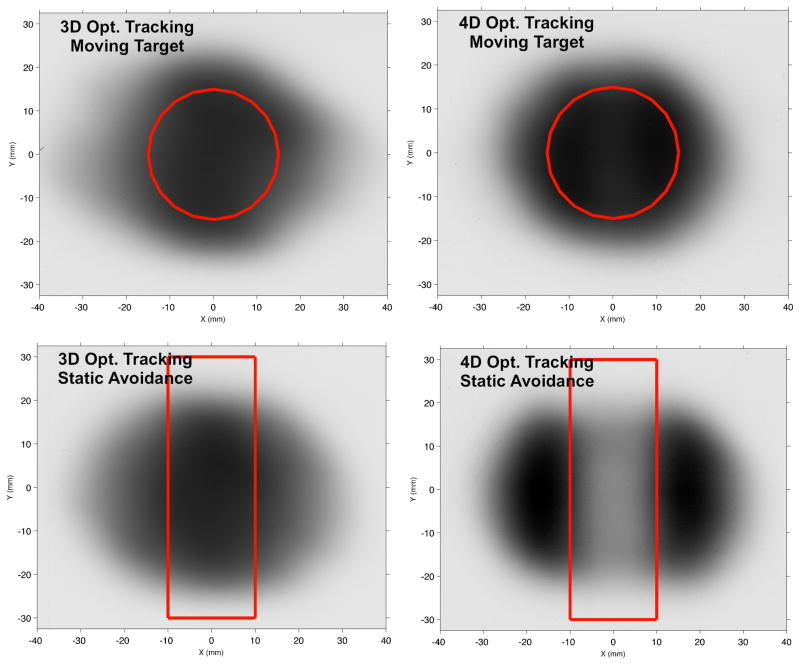

We experimentally confirmed the ability of 4D-optimized beam tracking to reduce dose to an avoidance volume near a moving target compared with 3D-optimized beam tracking for our moving target phantom using a scanned carbon ion beam. Figure 12 shows our film measurements from the 4D-optimized beam tracking validation experiment. We observed that 4D-optimized beam tracking provided a similar uniformity of film darkening to 3D-optimized beam tracking for the moving target, with mean optical densities of film in the target region of 1.00 ± 0.14 and 1.00 ± 0.10, respectively. However, 4D-optimized beam tracking provided much less dose to the avoidance region than 3D-optimized beam tracking, as seen in the lighter film exposure in that region, with mean optical densities in the avoidance region of 0.26 versus 0.71, respectively, and max optical densities in the avoidance region of 0.79 versus 1.37, respectively. Thus, using 4D-optimized beam tracking instead of 3D-optimized beam tracking reduced the mean film exposure in the avoidance region by 63% and reduced the max film exposure in the avoidance region by 42%. These measurements support our findings in-silico and provide evidence that our 4D-optimized beam tracking approach is technically feasible to deliver using a carbon ion synchrotron in a research laboratory.

Figure 12.

Experimental film results for scanned carbon ion delivery of 4D-optimized beam tracking (right) versus 3D-optimized beam tracking (left) using the GSI synchrotron facility. We found that 4D-optimized beam tracking drastically reduced dose to the static avoidance volume (red rectangle), as seen by less film darkening compared to 3D-optimized beam tracking, while both approaches produced similar uniform darkening of the moving circular target.

4. Discussion

In this work, we proposed a new 4D-optimized beam tracking approach for scanned ion-beam therapy and compared it against an existing 3D-optimized beam-tracking approach using simulation studies in 4D phantoms and a simple experiment with moving films. The major finding of this study is that 4D-optimized scanned ion beam tracking reduced the maximum dose to avoidance volumes near a moving target compared with 3D-optimized scanned ion beam tracking. In addition, 4D-optimized beam tracking substantially improved target dose homogeneity for a thoracic CTV, compared with 3D-optimized beam tracking.

In our water phantom study, we demonstrated that a drastic reduction in dose to an avoidance volume near a moving target is possible using 4D-optimized beam tracking instead of 3D-optimized beam tracking. The clinical significance of this finding is unclear at this time and will likely depend greatly on the exact motion characteristics of the target and avoidance tissues for individual patients. In our lung cancer patient study, we observed more modest sparing of an avoidance volume (the heart) using 4D optimization. The less dramatic sparing of the avoidance volume seen in the patient compared with the water phantom is likely a consequence of the similar motion between the target and the avoidance volume, i.e., the heart.

Thus, it appears that differential motion between target and avoidance volumes is a likely prerequisite to achieve clinically significant reductions in dose to avoidance volumes using 4D-optimized scanned ion beam tracking. Therefore, more patient studies are required to identify patient populations that would benefit most from this therapy. Of perhaps equal importance, we found that 4D-optimized beam tracking could drastically improve target dose coverage and dose uniformity for the lung cancer patient. This improved target coverage compared with 3D-optimized beam tracking appears to persist even when treatment planning and treatment delivery occur on different days, despite changes in breathing and organ motion. This finding potentially benefits a large class of patients with targets that undergo organ motion during treatment. Also, 3D-optimized beam tracking seems to pose a risk for degraded uniformity of tumor dose, compared to both 4D-optimized beam tracking and static dose simulations. This cautionary finding suggests that using beam tracking for deforming tissue without using 4D optimization or other correction methods may provide dosimetrically worse coverage than, for example, perfect beam gating.

For 3D-optimized beam tracking for the lung patient, this finding of non-uniform target dose for “perfect” tracking agrees with previous studies of Bert and Rietzel (2007) and van de Water et al. (2009), which reported that dose degradation can result from issues that are not considered in 3D-optimized beam tracking, namely rotations, deformations, and changes in scattering properties of tissue upstream to the target. For example, if the target rotates, the entrance channel dose for individual pencil beams can overlap in irregular patterns. If the target deforms, the geometric spacing between pencil beams may change, and due to the high dose gradients for each pencil beam, one may observe overdose when volume contraction occurs and underdose when volume dilation occurs. Further, if the target moves, even rigidly, beneath heterogeneous tissue upstream of the target, for example, a lung tumor moving beneath ribs, the multiple Coulomb scattering of individual pencil beams, and thus distribution of off-axis target dose contributions, will not be uniform for all motion states even if the range variations are compensated by beam tracking. Some of these issues were recently solved by Lüchtenborg et al. (2011). The advantage of their method compared to ours might be faster patient throughput, since their technique allows irradiation of the patient during any given motion state. In contrast, our approach solves a 4D field that potentially better spares avoidance volumes and might offer slightly more uniform target dose but must be delivered during specific motion states and could require long treatment times, similar to gating. However, a new 4D treatment control system developed by Graeff et al. (in press) should allow temporal interleaving of the irradiation of 4D-optimized fields and greatly reduce delivery time for 4D-optimized scanned ion beam tracking. Using such a system, we speculate that, at worst, our approach could be as slow as beam gating. However, by using temporal interleaving of the 4D-optimized irradiations, i.e., continuous switching and updating of the list of completed and remaining pencil beams required for each motion state, we could irradiate the patient quasi-continuously as the patient breathes freely and, thus, in many cases our method might be substantially faster than a beam gating approach.

In comparison to published literature on 4D-optimization for photon therapy, our approach was similar to that of Trofimov et al. (2005), using a deforming dose calculation grid and discrete motion states, though scanned ion beam therapy includes an additional degree of freedom compared to photon therapy, due to the multiple isoenergy layers. Our findings for the lung patient are consistent with their findings, which showed only slight reductions of dose to avoidance volumes for lung and liver patients using 4D-optimized photon beam tracking instead of photon beam gating. Similar to Chin and Otto (2011), we observed, in a phantom study, 4D optimization has a large ability to spare an avoidance volume near a moving target. In comparison with the approach of Graeff et al. (in press), our method was similar in how we calculated the 4D dose contribution to each voxel from each ion pencil beam for each motion state and included these in 4D optimization. However, our approach differs from theirs in the starting conditions and the boundary conditions of optimization. Namely, their method predetermined the motion state to irradiate given ion pencil beams with motives to minimize treatment time and to eliminate the need for range-tracking hardware. In contrast, our method allowed ion pencil beams to irradiate in any motion state that best met our objectives of uniform target dose coverage and minimal dose to avoidance volumes. Thus, we expect that our method may generally require longer irradiation times than theirs but achieve better sparing of designated avoidance volumes near a moving target.

Our study had several notable strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study of 4D optimization for scanned ion beam tracking therapy reported in the literature. We achieved improved target dose coverage and reduced dose to avoidance volumes by incorporating the entire 4DCT data set into 4D optimization of the scanned ion fields. Since we use the 4DCT and deformable image registration vectors in optimization, our approach provided a more uniform target dose than 3D-optimized beam tracking for a moving target in heterogeneous tissue. A further strength of this study was that we validated our work experimentally using a scanned carbon ion beam and a moving phantom.

This study had several limitations. One was that while we did consider patient motion in treatment planning, we did not consider uncertainties in patient motion during treatment plan optimization, and we assumed that the exact characteristics of patient anatomy and motion could be represented by a single planning 4DCT. Though our approach allowed variation in respiratory rate, we ultimately assumed that motion was perfectly periodic. Any substantial deviations from that assumption could result in treatment failure. However, this limitation was not important in the context of this study because we only sought to demonstrate feasibility that 4D optimization could potentially provide a benefit for scanned ion therapy for moving organs. A second limitation was that we only considered absorbed dose from scanned carbon ion therapy, that is, our modifications of the TRiP4D research code to allow simulation of 4D-optimized beam tracking did not allow optimization of RBE-weighted dose for our lung patient. Further work is needed to connect our approach with a method to optimize RBE-weighted dose, such as the Local Effect Model used at GSI (Scholz et al., 1997; Elsässer et al., 2010). However, the implementation of this in the TPS appears to be a technically straightforward task. Third, in this work, we encountered computer memory limitations during 4D optimization due to the large problem size when using our current 32-bit treatment planning system. Therefore, we downsampled the 4DCT images from original voxel sizes of (0.98 × 0.98 × 2.5) mm3 to voxel sizes of (2.93 × 2.93 × 2.5) mm3. This limitation is currently being addressed by extension of TRiP4D to utilize 64-bit computer architecture. A fourth limitation was that we only investigated one minimization algorithm, i.e., the conjugate gradient method, which may converge on local minima rather than a global minimum. The additional degrees of temporal freedom present in the objective function for 4D-optimized tracking could potentially increase or decrease the presence of local minima. Further studies are needed to investigate uniqueness of found minima and to investigate convergence criteria for this method that best ensure the optimal 4D dose distributions are found during minimization. Fifth, we only investigated one beam angle for each test case. However, our codes can be used to optimize multiple beams simultaneously to plan 4D-optimized intensity modulated particle therapy. Some of these limitations were intended by the design of our study and allowed us to see things that could have otherwise been confounded by increasing the complexity of our study. While we acknowledge these limitations of our work, they did not prevent us from achieving our goals, which were to demonstrate proof-of-concept for a new beam tracking approach using 4D optimization and to investigate possible dose reductions for avoidance volumes near moving targets.

4D optimization for scanned ion therapy has many possible avenues for future work. The incorporation of motion and setup uncertainties into treatment planning via robust 4D optimization may provide a more reliable and stable treatment than that proposed here. While several studies have demonstrated the ability of robust optimization to mitigate uncertainties in treatment planning and patient alignment for particle therapy (Pflugfelder et al., 2007; Lomax, 2008; Meyer et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2012), to our knowledge, no studies have yet incorporated respiratory motion information into robust optimization routines for particle therapy. Those 4D robust-optimization efforts will likely face high computational challenges since the optimization matrix typically grows by the product of the number of uncertainties simulated and the number of motion states modeled but may become feasible with continued advances in high-performance computing. For patients with slightly irregular motion trajectories, it should be theoretically possible to incorporate several 4DCT series into the optimization of a single beam-tracking plan that is more robust to each possible trajectory represented by the individual 4DCTs. For chaotic motion, such as seen in the abdomen near the bowel, the 4D optimization concept could potentially be modified to provide a robust 3D field solution that is optimized using multiple 3DCT image sets acquired, for example, on different days prior to treatment.

In summary, we proposed a 4D-optimized beam tracking approach for scanned ion therapy that provided reduced dose to avoidance volumes and improved target dose coverage for a thoracic CTV, compared with 3D-optimized beam tracking. Theoretically, these dosimetric advantages can be used either to provide reduced risk of treatment side effects when target doses are designed for a standard tumor control probability or can allow increased target doses and improved tumor control probability when risks of treatment side effects are allowed to approach those risk levels typical of standard care. Either avenue may be valuable to improving patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Horcicka and Daniel Richter for helpful scientific discussions regarding 4D treatment planning and optimization. We thank Nami Saito for her help with deformable image registration. Portions of this work were funded by the Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst, the Rosalie B. Hite Fellowship, the National Cancer Institute Award 1 R01 CA 131463-01A1, Northern Illinois University through a subcontract of the Department of Defense Award W81XH-08-1-0205, and the POFII Program of the Helmholtz Gemeinschaft.

References

- Bert C, Durante M. Motion in radiotherapy: particle therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56:R113–44. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/16/R01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bert C, Rietzel E. 4D treatment planning for scanned ion beams. Radiat Oncol. 2007;2 doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin E, Otto K. Investigation of a novel algorithm for true 4D-VMAT planning with comparison to tracked, gated and static delivery. Med Phys. 2011;38:2698–707. doi: 10.1118/1.3578608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsässer T, Weyrather WK, Friedrich T, Durante M, Iancu G, Kramer M, Kragl G, Brons S, Winter M, Weber KJ, Scholz M. Quantification of the relative biological effectiveness for ion beam radiotherapy: direct experimental comparison of proton and carbon ion beams and a novel approach for treatment planning. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2010;78:1177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher R, Reeves CM. Function Minimization by Conjugate Gradients. Comput J. 1964;7:149. [Google Scholar]

- Graeff C, Lüchtenborg R, Eley JG, Durante M, Bert C. A 4D-optimization concept for scanned ion beam therapy. Radiother Oncol. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.09.018. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grözinger SO, Li Q, Rietzel E, Haberer T, Kraft G. 3D online compensation of target motion with scanned particle beam. Radiother Oncol. 2004;73(Suppl 2):S77–9. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(04)80020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horcicka M, Meyer C, Buschbacher A, Durante M, Kramer M. Algorithms for the optimization of RBE-weighted dose in particle therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58:275–86. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/2/275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keall PJ, Starkschall G, Shukla H, Forster KM, Ortiz V, Stevens CW, Vedam SS, George R, Guerrero T, Mohan R. Acquiring 4D thoracic CT scans using a multislice helical method. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:2053–67. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/10/015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krämer M, Jakel O, Haberer T, Kraft G, Schardt D, Weber U. Treatment planning for heavy-ion radiotherapy: physical beam model and dose optimization. Phys Med Biol. 2000;45:3299–317. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/11/313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Zhang X, Li Y, Mohan R. Robust optimization of intensity modulated proton therapy. Med Phys. 2012;39:1079–91. doi: 10.1118/1.3679340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomax AJ. Intensity modulated proton therapy and its sensitivity to treatment uncertainties 2: the potential effects of inter-fraction and inter-field motions. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:1043–56. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/4/015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüchtenborg R, Saito N, Durante M, Bert C. Experimental verification of a real-time compensation functionality for dose changes due to target motion in scanned particle therapy. Med Phys. 2011;38:5448–58. doi: 10.1118/1.3633891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J, Bluett J, Amos R, Levy L, Choi S, Nguyen QN, Zhu XR, Gillin M, Lee A. Spot Scanning Proton Beam Therapy for Prostate Cancer: Treatment Planning Technique and Analysis of Consequences of Rotational and Translational Alignment Errors. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2010;78:428–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohadani O, Seco J, Bortfeld T. Motion management with phase-adapted 4D-optimization. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:5189–202. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/17/019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflugfelder D, Wilkens JJ, Szymanowski H, Oelfke U. Quantifying lateral tissue heterogeneities in hadron therapy. Med Phys. 2007;34:1506–13. doi: 10.1118/1.2710329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter D, Schwarzkopf A, Trautmann J, Kramer M, Durante M, Jäkel O, Bert C. Upgrade and benchmarking of a 4D treatment planning system for scanned ion beam therapy. Med Phys. 2013;40:051722. doi: 10.1118/1.4800802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito N, Bert C, Chaudhri N, Gemmel A, Schardt D, Durante M, Rietzel E. Speed and accuracy of a beam tracking system for treatment of moving targets with scanned ion beams. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:4849–62. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/16/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schardt D, Elsässer T, Schulz-Ertner D. Heavy-ion tumor therapy: Physical and radiobiological benefits. Rev Mod Phys. 2010;82:383–425. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz M, Kellerer AM, Kraft-Weyrather W, Kraft G. Computation of cell survival in heavy ion beams for therapy - The model and its approximation. Radiat Environ Bioph. 1997;36:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s004110050055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackleford JA, Kandasamy N, Sharp GC. On developing B-spline registration algorithms for multi-core processors. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:6329–51. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/21/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger B, Kramer M, Kraft G. Three-dimensional dose verification with x-ray films in conformal carbon ion therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2003;48:497–505. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/4/306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trofimov A, Rietzel E, Lu HM, Martin B, Jiang S, Chen GT, Bortfeld T. Temporo-spatial IMRT optimization: concepts, implementation and initial results. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:2779–98. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/12/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Water S, Kreuger R, Zenklusen S, Hug E, Lomax AJ. Tumour tracking with scanned proton beams: assessing the accuracy and practicalities. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:6549–63. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/21/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber U, Kraft G. Design and construction of a ripple filter for a smoothed depth dose distribution in conformal particle therapy. Phys Med Biol. 1999;44:2765–75. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/44/11/306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Jeraj R, Keller H, Lu W, Olivera GH, McNutt TR, Mackie TR, Paliwal B. Treatment plan optimization incorporating respiratory motion. Med Phys. 2004;31:1576–86. doi: 10.1118/1.1739672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]