Abstract

Background and Objective

Preoccupation (attentional bias) related to drug-related stimuli has been consistently observed for drug-dependent persons with several studies reporting an association of the magnitude of measured attentional bias with treatment outcomes. The major goal of the present study was to determine if pre-treatment attentional bias to personal drug use reminders in an addiction Stroop task predicts relapse in treatment-seeking, cocaine-dependent subjects.

Methods

We sought to maximize the potential of attentional bias as a marker of risk for relapse by incorporating individualized rather than generalized drug use cues to reflect the personal conditioned associations that form the incentive motivation properties of drug cues in a sample of cocaine-dependent subjects (N = 35).

Results

Although a significant group Stroop interference effect was present for drug versus neutral stimuli (i.e., attentional bias), the level of attentional bias for cocaine-use words was not predictive of eventual relapse in this sample (d = 0.56). A similar lack of prediction power was observed for a non-drug counting word Stroop task as a significant interference effect was detected but did not predict relapse outcomes (d = 0.40).

Conclusions and Scientific Significance

The results of the present study do not provide clear support for the predictive value of individual variation in drug-related attentional bias to forecast probability of relapse in cocaine-dependent men.

Keywords: attentional bias, treatment, cocaine dependence, Stroop task, relapse

INTRODUCTION

Drug addiction is characterized by pathological learned associations and strongly consolidated memories of drug use. Learned associations of drug use with the exteroceptive (e.g., people, places) and interoceptive (e.g., mood states) contexts of often ritualized drug abuse render these contexts as having conditioned incentive salience 1,2. Due to their acquired properties as incentive motivational stimuli, attentional responses to such conditioned drug use cues represent powerful precipitants of drug seeking and use behaviors in drug-addicted individuals 3. Typically assessed by their cognitive interference effect on ongoing task performance, an attentional bias for drug use cues has been observed for alcohol 4,5, nicotine 6,7, marijuana 8, heroin 9, and cocaine 10–13 stimuli. These collective findings indicate that an attentional bias for conditioned drug cues represents a general feature of drug addiction. The level of attentional bias for drug cues, and their associated neural responses 14,15, represent candidate neurocognitive markers of drug dependence.

The significance of attentional bias to the addiction process is further heightened by the observations that the level of attentional bias for drug stimuli predicts motivation for drug use, relapse and treatment outcome in drug-abusing populations for heroin 16,17, alcohol 18,19, and nicotine 7,15 stimuli. Additionally, adolescents at-risk for alcohol use disorders exhibit a significant attentional bias for alcohol-related stimuli 20. For cocaine abusers, the level of attentional bias was significantly correlated with the magnitude of self-rated drug craving 10 and drug-seeking behavior 4, and predicted the frequency of cocaine use lapses and treatment duration 11. These findings suggest that measures of attentional bias for drug cues have further significance as a cognitive marker of risk of relapse. We sought in this study to further assess the relationship between level of attentional bias for cocaine use cues and treatment outcome in a sample of treatment-seeking, cocaine-dependent men.

Attentional bias for drug-related stimuli has been estimated using visual probe tasks, which directly assess the effects of drug cues on attentional orientation 8, and, more frequently, Stroop tasks 21, which assess cognitive interference when the processing of a task-irrelevant stimulus feature interferes with the simultaneous processing of a task-relevant stimulus attribute 22. The majority of the Stroop tasks that incorporate drug use cues (addiction Stroop tasks) share several features – the use of generalized drug use stimuli to facilitate stimulus control and the grouping of stimulus types (i.e., drug, neutral) in blocks to minimize carryover effects 21. The cocaine Stroop task (cocStroop) used in the present study deviated from this pattern by the use of personalized, rather than generalized, drug stimuli to respect the fact that the associative learning underlying drug cue conditioning is highly individually variable, and thus to potentially enhance the incentive salience of the drug cues. Furthermore, a random, rather than blocked design of stimulus presentation was used to specifically assess the carryover effect between drug and neutral stimuli as a further measure of the property of problems of attentional disengagement attributed to the attentional bias effect in persons with drug use disorders 23, and to avoid habituation effects. Finally, the level of cognitive interference for non-drug stimuli in a classical color Stroop task discriminated cocaine-dependent individuals who completed versus did not complete a treatment trial, suggesting that level of global cognitive control ability predicted treatment retention24. We therefore compared the ability of the level of cognitive interference for drug stimuli (cocStroop) versus non-drug stimuli (cStroop) for a counting word Stroop task to predict treatment outcome in the same sample of cocaine-dependent subjects. This study tested the hypotheses that personalized drug stimuli are associated with significant attentional bias in cocaine-dependent individuals, and that the relationship between the level of attentional bias and relapse and treatment retention is stronger for drug stimuli versus non-drug stimuli in the cocStroop task.

METHODS

Study participants

Thirty-five male adult cocaine-dependent individuals participated in this study (Table 1). All study subjects provided written informed consent to participate in a research protocol approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and the Atlanta Veteran’s Administration Medical Center (VAMC) Research and Development Committee. Eligible subjects were cocaine-dependent men between 18 and 65 years of age and met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders---Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for diagnosis of cocaine dependence. Potential subjects were excluded for any current Axis I diagnosis other than cocaine or alcohol dependence or nicotine use, current or prior neurological disease, history of a major medical illness, or current use of psychotropic medications.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants (All subjects were male.)

| Variable | Nonrelapsers | Relapsers | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 20 | 15 | |

| Age (years) | 43.7 ± 4.9 | 43.0 ± 6.8 | ns |

| Education (years) | 13.3 ± 1.4 | 13.4 ± 1.3 | ns |

| Cocaine use | |||

| Use past 7 days | 1.0 ± 1.5 | 1.2 ± 1.6 | ns |

| Use past 30 days | 14.5 ± 8.3 | 13.9 ± 8.7 | ns |

| Addiction severity index (ASI) | |||

| Alcohol | 0.13 ± 0.20 | 0.32 ± 0.29 | 0.049* |

| Drug | 0.22 ± 0.07 | 0.26 ± 0.08 | ns |

| Psychiatric | 0.13 ± 0.20 | 0.28 ± 0.20 | 0.024 |

| Days in treatment | 122.7 ± 95.7 | 52.7 ± 70.0 | 0.012* |

| CAARS—inattentive symptoms | 43.0 ± 12.9 | 51.6 ± 12.5 | 0.031 |

Treatment program

The study was conducted in the Substance Abuse Treatment Program (SATP) at the Atlanta, GA VAMC. The outpatient treatment program consisted primarily of 3- or 5- day weekly sessions of twelve-step recovery in a group setting. Following the initial four weeks of treatment, subjects could opt to continue voluntary treatment in the Aftercare portion in which subjects could receive weekly group therapy sessions; 16 of 20 non-relapsers and 6 of 15 relapsers opted for Aftercare. Drug abstinence was assessed by urinalysis for cocaine and its metabolites, and other drugs of abuse, at random time points twice weekly over the first 4 weeks of active treatment, and weekly in the Aftercare component. Relapse was defined as a documented use of cocaine as determined by urinalysis and/or self-report or other-report as entered in the electronic medical records (EMR) entries for each subject. Subjects were actively followed for a period of 90 days from study enrollment to include active treatment and long-term follow-up.

Assessment instruments

All study-eligible subjects were evaluated using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV Axis-I Disorders (SCID) 25 to assess the presence of current psychiatric disorders, the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) 26 to assess the severity of addiction-related functional impairment, and the Connors Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS) 27 to assess the severity of ADHD traits. Demographic information (e.g. age, education) was collected from study participants using a study-specific data collection instrument. All assessments were completed at the initial screening visit.

Stroop tasks

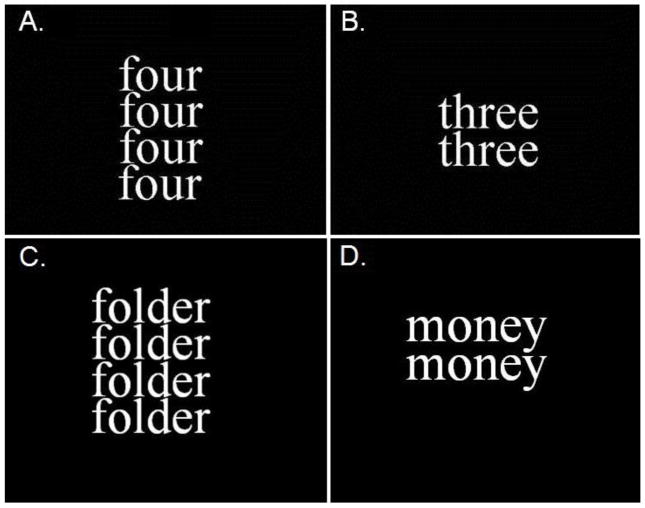

In this study, we utilized a word counting Stroop task that incorporated words representing personal drug use reminders (cocStroop task). All subjects at study entry identified eight cocaine cue words that were associated with their personal drug craving and use. The cocStroop task comprised eight personal cocaine-related (CS+) words (e.g., money, stem) and drug use-neutral (CS−) words (e.g., shelf, table). The counting Stroop (cStroop) was comprised of congruent stimuli in which the number and name of the words are the same and incongruent stimuli in which they differ 28. The cStroop served as a measure of global cognitive control ability relative to that specifically engaged by cocaine stimuli in the cocStroop task. For each of the tasks, a trial involved the presentation of 1–4 identical words in a vertical array (Figure 1) with instructions to indicate by button press, on a 4-button response pad, the numbers of words represented. Subjects were instructed to respond as quickly as possible. Each Stroop task involved 89 word counting trials in which 33 of the words were cocaine-related (cocStroop) or incongruent (cStroop) word stimuli presented for 750 msec with an interstimulus interval of 3 sec, during which time the participants had to register a response by button press. Task training prior to data acquisition involved repeated trials of the cStroop task. The cStroop task was completed first followed by the cocStroop task. Word stimulus trials for both Stroop tasks were presented in a random order with a run consisting of 178 words (Total run time = 11 min). Behavioral measures of reaction time (RT) and response accuracy were collected for each task trial at the initial screening or study baseline.

Fig 1.

Stimulus trials for congruent (A.) and incongruent (B.) stimuli for the cStroop task and neutral (C.) and cocaine use (D.) words for the cocStroop task

Personalized vs. generalized drug use words

In this study, the addiction counting Stroop task (cocStroop) utilized personal drug use-related words instead of a generalized word list. Previous studies that have utilized modified Stroop tasks have relied on general drug use-related words e.g. 11,12,29,30; however, this study used personalized drug use reminders as they are more representative of the individualized context-specific nature of learned drug associations. Eight drug use-related words were generated from each participant by using a cocaine cue word generator in which subjects disclosed their personal triggers associated with patterns of drug seeking and use behaviors.

Statistical Analyses

Stroop Tasks Processing

The mean reaction time (msec) was calculated for correct responses for each stimulus trial. Incorrect responses for stimulus trials were removed.

Continuous data were analyzed using analysis of variances (ANOVAs). Kruskal-Wallis tests were used when the respective data set violated assumptions of distribution normality or homogeneity of variance. Paired t-tests were also performed to assess differences in mean reaction times between neutral and drug-use related words in the cocStroop task and between congruent and incongruent stimuli in the cStroop task among all subjects. Carry-over effects (i.e. the effect of one trial “carries over” to the next trial) were calculated and analyzed by paired t-test for the following successive trial pairs: cocaine_neutral > neutral_neutral, and incongruent_congruent > congruent_congruent. Percent accuracy was also determined for responses for both Stroop tasks. Logistic regression was used to determine if the magnitude of the Stroop interference effect predicted relapse in cocaine-dependent subjects. Analyses employed the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) Version 9.2.

RESULTS

Subject demographic and clinical variables

Subjects reported using crack cocaine an average of 1.09 (± 1.46) and 14.2 (± 8.08) days in the past 7 and 30 days, respectively. All subjects were male with 98% of the subjects self-reporting African-American as their racial background. Subjects were classified as nonrelapsers if they did not relapse to cocaine use in the 0–90 day treatment and follow-up periods. Within this subset of 35 treatment-seeking, cocaine-dependent subjects, 20 were classified as non-relapsers and 15 as relapsers. Relapsers and nonrelapsers did not differ in any of the baseline measured variables including age, education and cocaine use patterns. However, the two groups did exhibit significant differences on the CAARS subscale for DSM-IV inattentive symptoms (p = 0.031), and for the ASI psychiatric (p = 0.024) and alcohol (p = 0.049) subscales (Table 1); with relapsers exhibiting greater subscale scores for each measure. Non-relapsers also had significantly greater treatment retention (days in treatment) as compared to relapsers (p = 0.012) (Table 1).

Logistic Regression

A logistic regression analysis was used to predict the odds of relapse over the 90 day study period in this sample of cocaine-dependent subjects. Two Stroop task models (interference effect: cStroop and cocStroop) were compared to assess their relative ability to predict relapse in this sample. The results indicate that interference effects for the cocStroop (cocaine-neutral) and cStroop (incongruent-congruent) were not statistically significant predictors of relapse (cocStroop model: p = 0.115, OR = 1.01, confidence intervals (CI) = 0.99, 1.02 and cStroop model: p = 0.250, OR = 1.01, CI = 0.99, 1.02). A direct comparison of fit indices for the cocStroop and cStroop regressions (χ2, p = 0.18) indicated their comparable power to predict outcomes. Because there was a significant difference between relapsers and non-relapsers on the CAARS subscale for DSM-IV inattentive symptoms and for the ASI psychiatric and alcohol subscales, these variables were subsequently analyzed to determine their association with relapse prediction. The CAARS DSM-IV Inattentive (p = 0.078, OR = 1.06, CI = 0.99, 1.12) and ASI-psychiatric subscales (p = 0.064, OR = 34.48, CI = 0.813, >999.99) did not discriminate the relapse groups; however, the ASI alcohol subscale (p = 0.038, odds ratio (OR) = 23.059, CI = 1.19, 445.82) was predictive of relapse in this sample of cocaine-dependent subjects. The results also indicate that total number of days in treatment is a statistically significant predictor of relapsing (p = 0.035, OR = 0.998, CI = 0.976, 0.999). Multiple logistic regression models that incorporated additional explanatory baseline variables (i.e., ASI subscales, CAARS, alcohol dependence, nicotine dependence, drug use last 7 or 30 days) also did not yield significant predictive outcomes.

Task performance

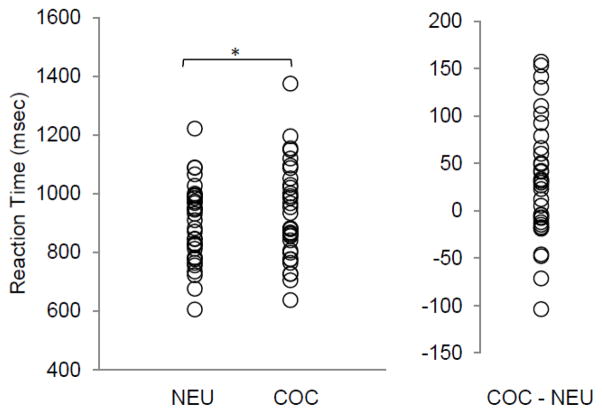

Attentional Bias for Conditioned Drug Cues

Of the drug use-related words provided by the 35 study participants, only 33 (18%) were shared by two or more participants while 155 were unique to individuals. The most frequently provided words (i.e. money, sex, and smoke) accounted for 14%, 6% and 6% of the words, respectively. Analyses of the personalized drug use-related words determined that the order of presentation of drug use-related words and the reaction times for individual drug use-reminder words (e.g. money versus sex) were not significant within subjects. As a group, cocaine-dependent men exhibited a significant increase (p<0.005) in reaction time for personal drug use-related words (928.6 ± 160.0 msec) versus neutral words (897.2 ± 132.5 msec) for the cocStroop task (Figure 2). The mean attentional bias effect for the group was 31.4 ± 62.2 msec, with evidence of wide interindividual variability reflected in a range of 153 to −103 msec. Relapsers and non-relapsers did not exhibit a significant difference (p = 0.054, one-tailed; d = 0.56) in reaction time to cocaine use-related words versus neutral words; however, the group comparison approached statistical significance. The group of individuals who relapsed did have higher mean attentional bias effects for drug cues (51.0 ± 67.2 msec) relative to the group of non-relapsers (16.7 ± 55.5 msec). Response accuracy across all subjects was 94.9% (± 6.8) with no significant difference between groups. An analysis of carryover effects related to the processing of cocaine use word stimuli indicated that reaction times for the processing of neutral words preceded by cocaine use-related words (p < 0.019) were significantly longer than for neutral words preceded by neutral words. A subsequent t-test of the relapse groups, controlling for the carryover effect of drug use stimuli, did not demonstrate a significant difference (p = 0.076, one-tailed; d = 0.49) in attentional bias effect for relapsers (55.1 ± 75.9 msec) versus non-relapsers (23.2 ± 53.3 msec).

Fig 2.

Reaction times for drug use-related and neutral words related to a modified addiction Stroop (cocStroop) task for a sample of cocaine-dependent men. The group mean reaction time (± SD) for neutral word stimuli and cocaine use-related word stimuli was 897.2 (± 132.5) and 928.6 (± 160.0) msec, respectively (*p < 0.005). The group mean for the cocStroop interference effect (cocaine - neutral) was 31.4 (± 62.2) msec.

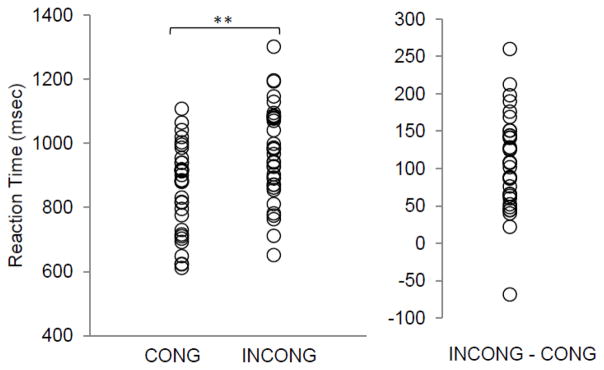

Counting Stroop

For the cStroop task, subjects had significantly longer reaction times (p<0.0001) on incongruent stimuli (967.9 ± 147.4) versus congruent stimuli (859.0 ± 133.7) (Figure 3). There was no significant difference in response times for incongruent versus congruent stimuli between the groups of relapsers (123.2 ± 61.2) and non-relapsers (98.1 ± 64.5) (p = 0.126; d = 0.40). Response accuracy across all subjects was 95.2% (± 6.83) with no significant difference between groups. For the cStroop task, the carryover analysis revealed that reaction times were not significantly greater for congruent stimuli preceded by incongruent stimuli versus congruent stimuli preceded by congruent stimuli (p = 0.208).

Fig 3.

Reaction times for congruent and incongruent stimuli related to a word counting Stroop (cStroop) task for a sample of cocaine- dependent men. The group mean reaction time (± SD) for congruent and incongruent word stimuli was 859.0 (± 133.7) and 967.9 (± 147.4) msec, respectively (**p < 0.0001). The group mean for the cStroop interference effect (congruent - incongruent) was 108.87 ± 63.43 msec)

DISCUSSION

This study sought to assess whether the level of pre-treatment attentional bias predicts relapse in a treatment-seeking, cocaine-dependent, adult male population. A prior study reported that level of pre-treatment attentional bias predicted a binary measure of relapse in opiate-dependent subjects 16; however, abstinence was based solely on self-report and was not confirmed by urinalyses. Other studies have noted that the level of attentional bias for drug-use related stimuli is associated with the magnitude of cocaine and heroin craving 10,31, and proportion of cocaine positive urines 11. These treatment outcome studies suggest that attentional bias for drug-related cues could precipitate drug taking or relapse following treatment. This relationship is consistent with a recent Ecological Momentary Assessment study that demonstrated that elevated attentional bias predicted drug use temptation episodes for heroin-dependent adults 17. As previously demonstrated for addiction Stroop tasks incorporating generalized drug-related stimuli 10–13,31, the present results indicate that cocaine-dependent subjects exhibit a robust attentional bias effect for personalized drug-use related stimuli. However, though subjects exhibited a significant attentional bias for personal drug-use reminders, this variable did not significantly predict relapse group membership in this sample.

In a drug-unrelated color Stroop task, the level of performance interference by incongruent stimuli predicted treatment completion in a sample of cocaine-dependent individuals24. A similar observation was also seen in which neural responses to a cognitive control demand posed by the same Stroop task predicted clinically relevant outcomes such as treatment retention32. Both studies suggest that variation in general cognitive control ability, rather than acquired incentive motivational or other properties of drug-related stimuli that underlie their attentional bias effect, is predictive of clinical treatment outcomes for drug-dependent individuals. This contention is not supported by the findings of the present study as both eventual relapsers and non-relapsers exhibited a comparable cognitive interference effect related to incongruent stimuli in the cStroop task. This outcome does support the contention that risk for relapse is not attributable to global deficits in cognitive control associated with cocaine dependence33,34. Furthermore, logistic regression analysis did not support the value of attentional bias as a cognitive marker of risk for relapse in a sample of cocaine-dependent men. Cocaine use words also exhibited a significant carryover effect on subsequent neutral stimulus trials for the cocStroop task, a finding consistent with the contention that the attentional bias effect is attributable to difficulty in disengaging attention from drug use reminders23. It is also plausible that the motivational salience of the preceding cocaine-use word could hinder task performance on a following neutral word stimulus.

There are plausible reasons as to why attentional bias may be a valid cognitive marker of drug dependence, but have more limited value as a marker of treatment outcome. Multiple and varying factors contribute to temporally extended incidences of relapse in treatment-seeking drug-dependent populations, and thus to the ability of a baseline measure to predict relapse. The varying experiences of psychological or social stressors (e.g. negative affect state, interpersonal problems, craving) as well as environmental factors (e.g. presence and/or availability of drug, competing cognitive demands) undoubtedly contribute to individually varying rates of relapse over time. Variation in individual traits (e.g., compulsivity, genotype) also contributes to variation in relapse rates. Paralleling research outcomes indicate that these variables (i.e., compulsivity, incentives for drug abstinence, drug expectancy, drug cue complexity, cognitive load, and drug use status) also modulate attentional bias and drug cue reactivity 14,30,35–38, Measures of cognitive bias for drug cues have poor internal consistency and thus may not represent reliable markers of relapse risk, particularly for non-blocked stimuli as was used in the present study 39. Therefore, the multidetermined nature of attentional bias in drug use disorders 40 supports individual and temporal variation in the ability to predict future drug use and treatment outcomes. Perhaps the level of attentional bias has a time-limited value as a cognitive marker of risk for relapse. This contention is supported by a recent short-term (1 week) ecological momentary analysis study of heroin-dependent individuals in which drug attentional bias effects were related to relapse during temptation-related but not random assessments41. Finally, not all studies support an ability of attentional bias to predict treatment outcome 42.

In this treatment study, personalized drug use-related words were used in a modified addiction Stroop task. However, the majority of drug addiction studies utilize one of several available lists of drug use-related words for addiction Stroop tasks. Although generalized word lists have task advantages such as the ability to lexically standardize drug and neutral words to presumably isolate the attentional response to the addiction relatedness of the drug use-related word stimuli 21, this study opted for personalized drug-use words to similarly enhance their addiction relatedness for each subject based on their individually differing learned associations with drug use. Indeed, in this study, 82% of the drug-use related words were unique to subjects.

The study design does have clear limitations that temper the number of meaningful conclusions to be drawn. As personalized and generalized drug use words were not directly compared it remains unknown as to whether drug cues reflecting personal learned associations with drug use represent comparable or superior measures of attentional bias effect. Such a methods development study would be worthwhile to future efforts to develop attentional bias as a possible cognitive marker of drug dependence or treatment outcome. It is also worth noting that the main outcome variable of the study was drug use abstinence or not among the study population; however, relapse can be quantified and defined numerous ways (e.g., proportion of negative urines, etc.) which may affect the observed attentional bias-treatment outcome relationship. The drug use and neutral word stimuli were clearly not matched for the possible confounds of familiarity or frequency of use in the English language, though this is rarely attained or relevant in case-control studies of attentional bias related to addiction and word familiarity is independent from attentional bias in addiction Stroop tasks 43. The drug use and neutral words were also not matched for lexical properties. Blocked stimulus designs are generally thought to be preferable to the non-blocked design used here to control for deficits in attentional engagement to drug cues associated with drug dependence. Indeed, significant carryover effects for drug stimuli on task reaction times were observed. The present study also lacked a control group of healthy comparison subjects of possible value to characterizing the impact of cocaine dependence of cStroop task performance. Perhaps most importantly, our findings are also limited by the relatively small sample size which might have reduced the power to detect the predictive relationship between attentional bias and subsequent relapse.

CONCLUSION

Attentional bias for drug-related stimuli constitutes a clinically relevant candidate neurocognitive marker of drug dependence 14. The use of personalized versus generalized drug use-related words in a counting word Stroop task was associated with a significant interference effect relative to drug-neutral words (i.e., attentional bias). The results of the present study do not support the predictive value of individual variation in attentional bias to forecast probability of relapse in treatment-engaged, cocaine-dependent men.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by NIH grants R21DA025243 (Emory University, Atlanta, GA; Clinton Kilts) and F31DA025491 (Emory University, Atlanta, GA; Ashley Kennedy) from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Center for Research Resources grants UL RR025008 and TL1 RR025010 from the Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute (ACTSI) (Emory University, Atlanta, GA).

The authors also gratefully acknowledge the invaluable assistance and input to the project by the SATP clinical group leaders.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews. 1993;18(3):247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moeller SJ, Maloney T, Parvaz MA, et al. Enhanced Choice for Viewing Cocaine Pictures in Cocaine Addiction. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(8):1403–1413. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox WM, Brown MA, Rowlands LJ. THE EFFECTS OF ALCOHOL CUE EXPOSURE ON NON-DEPENDENT DRINKERS’ ATTENTIONAL BIAS FOR ALCOHOL-RELATED STIMULI. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2003 Jan 1;38(1):45–49. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lusher J, Chandler C, Ball D. Alcohol dependence and the alcohol Stroop paradigm: evidence and issues. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75(3):225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wertz JM, Sayette MA. Effects of smoking opportunity on attentional bias in smoker. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15(3):268–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waters AJ, Shiffman S, Sayette MA, Paty JA, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH. Attentional bias predicts outcome in smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 2003;22(4):378–387. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field M, Eastwood B, Bradley BP, Mogg K. Selective processing of cannabis cues in regular cannabis users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;85(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franken IHA, Kroon LY, Wiers RW, Jansen A. Selective cognitive processing of drug cues in heroin dependence. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2000 Jul 1;14(4):395–400. doi: 10.1177/026988110001400408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Copersino ML, Serper MR, Vadhan N, et al. Cocaine craving and attentional bias in cocaine-dependent schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Research. 2004;128(3):209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter KM, Schreiber E, Church S, McDowell D. Drug Stroop performance: Relationships with primary substance of use and treatment outcome in a drug-dependent outpatient sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(1):174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hester R, Dixon V, Garavan H. A consistent attentional bias for drug-related material in active cocaine users across word and picture versions of the emotional Stroop task. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006 Feb 28;81(3):251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vadhan NP, Carpenter KM, Copersino ML, Hart CL, Foltin RW, Nunes EV. Attentional Bias Towards Cocaine-Related Stimuli: Relationship to Treatment-Seeking for Cocaine Dependence. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33(5):727–736. doi: 10.1080/00952990701523722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ersche KD, Bullmore ET, Craig KJ, et al. Influence of Compulsivity of Drug Abuse on Dopaminergic Modulation of Attentional Bias in Stimulant Dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Jun 1;67(6):632–644. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janes AC, Pizzagalli DA, Richardt S, et al. Neural Substrates of Attentional Bias for Smoking-Related Cues: An fMRI Study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(12):2339–2345. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marissen MAE, Franken IHA, Waters AJ, Blanken P, Brink Wvd, Hendriks VM. Attentional bias predicts heroin relapse following treatment. Addiction. 2006;101(9):1306–1312. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waters A, Marhe R, Franken IA. Attentional bias to drug cues is elevated before and during temptations to use heroin and cocaine. Psychopharmacology. 2012 Feb 01;219(3):909–921. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2424-z. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox WM, Hogan LM, Kristian MR, Race JH. Alcohol attentional bias as a predictor of alcohol abusers’ treatment outcome. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68(3):237–243. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garland E, Franken IA, Howard M. Cue-elicited heart rate variability and attentional bias predict alcohol relapse following treatment. Psychopharmacology. 2012 Jul 01;222(1):17–26. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2618-4. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zetteler JI, Stollery BT, Weinstein AM, Lingford-Hughes AR. Attentional bias for alcohol-related information in adolescents with alcohol-dependent parents. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2006 Jul-Aug;41(4):426–430. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox WM, Fadardi JS, Pothos EM. The addiction-stroop test: Theoretical considerations and procedural recommendations. Psychol Bull. 2006 May;132(3):443–476. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1935;18(6):643–662. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waters AJ, Sayette MA, Franken IHA, Schwartz JE. Generalizability of carry-over effects in the emotional Stroop task. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43(6):715–732. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Streeter CC, Terhune DB, Whitfield TH, et al. Performance on the Stroop predicts treatment compliance in cocaine-dependent individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008 Mar;33(4):827–836. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.First MB. The DSM series and experience with DSM-IV. Psychopathology. 2002 Mar-Jun;35(2–3):67–71. doi: 10.1159/000065121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conners CK, Erhardt D, Epstein JN, Parker JDA, Sitarenios G, Sparrow E. Self-ratings of ADHD symptoms in adults I: Factor structure and normative data. Journal of Attention Disorders. 1999 Oct 1;3(3):141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bush G, Whalen PJ, Shin LM, Rauch SL. The counting Stroop: a cognitive interference task. Nat Protocols. 2006;1(1):230–233. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein RZ, Tomasi D, Rajaram S, et al. Role of the anterior cingulate and medial orbitofrontal cortex in processing drug cues in cocaine addiction. Neuroscience. 2007;144(4):1153–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montgomery C, Field M, Atkinson A, Cole J, Goudie A, Sumnall H. Effects of alcohol preload on attentional bias towards cocaine-related cues. Psychopharmacology. 2010;210(3):365–375. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1830-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franken IHA, Kroon LY, Hendriks VM. Influence of individual differences in craving and obsessive cocaine thoughts on attentional processes in cocaine abuse patients. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(1):99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brewer JA, Worhunsky PD, Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Potenza MN. Pretreatment Brain Activation During Stroop Task Is Associated with Outcomes in Cocaine-Dependent Patients. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64(11):998–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Sclafani V, Tolou-Shams M, Price LJ, Fein G. Neuropsychological performance of individuals dependent on crack–cocaine, or crack–cocaine and alcohol, at 6 weeks and 6 months of abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;66(2):161–171. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00197-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hester R, Garavan H. Executive Dysfunction in Cocaine Addiction: Evidence for Discordant Frontal, Cingulate, and Cerebellar Activity. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004 Dec 8;24(49):11017–11022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3321-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carpenter KM, Martinez D, Vadhan NP, Barnes-Holmes D, Nunes EV. Measures of Attentional Bias and Relational Responding Are Associated with Behavioral Treatment Outcome for Cocaine Dependence. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2012;38(2):146–154. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.643986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson SJ, Sayette MA, Fiez JA. Quitting-unmotivated and quitting-motivated cigarette smokers exhibit different patterns of cue-elicited brain activation when anticipating an opportunity to smoke. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(1):198–211. doi: 10.1037/a0025112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller MA, Fillmore MT. The effect of image complexity on attentional bias towards alcohol-related images in adult drinkers. Addiction. 2010;105(5):883–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hester R, Garavan H. Neural mechanisms underlying drug-related cue distraction in active cocaine users. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2009;93(3):270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ataya AF, Adams S, Mullings E, Cooper RM, Attwood AS, Munafò MR. Internal reliability of measures of substance-related cognitive bias. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;121(1–2):148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Field M, Cox WM. Attentional bias in addictive behaviors: A review of its development, causes, and consequences. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97(1–2):1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marhe R, Waters AJ, van de Wetering BJM, Franken IHA. Implicit and explicit drug-related cognitions during detoxification treatment are associated with drug relapse: An ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(1):1–12. doi: 10.1037/a0030754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spiegelhalder K, Jähne A, Kyle SD, et al. Is Smoking-related Attentional Bias a Useful Marker for Treatment Effects? Behavioral Medicine. 2011;37(1):26–34. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2010.543195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Field M. Cannabis ‘dependence’ and attentional bias for cannabis-related words. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2005;16(5–6):473–476. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200509000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]