Abstract

The current study was designed to explore the role of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (Stat1) during tumor promotion using the mouse skin multistage carcinogenesis model. Topical treatment with both 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) and 3-methyl-1,8-dihydroxy-9-anthrone (chrysarobin or CHRY) led to rapid phosphorylation of Stat1 on both tyrosine (Y701) and serine (S727) residues in epidermis. CHRY treatment also led to upregulation of unphosphorylated Stat1 (uStat1) at later time points. CHRY treatment also led to upregulation of interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) mRNA and protein, which was dependent on Stat1. Further analyses demonstrated that topical treatment with CHRY but not TPA upregulated interferon-gamma (IFNγ) mRNA in the epidermis and that the induction of both IRF-1 and uStat1 was dependent on IFNγ signaling. Stat1 deficient (Stat1-/-) mice were highly resistant to skin tumor promotion by CHRY. In contrast, the tumor response (in terms of both papillomas and squamous cell carcinomas) was similar in Stat1-/- mice and wild-type littermates with TPA as the promoter. Maximal induction of both cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase in epidermis following treatment with CHRY was also dependent on the presence of functional Stat1. These studies define a novel mechanism associated with skin tumor promotion by the anthrone class of tumor promoters involving upregulation of IFNγ signaling in the epidermis and downstream signaling through activated (phosphorylated) Stat1, IRF-1 and uStat1.

Keywords: Stat1, IRF-1, IFNγ, tumor promotion, inflammation, epithelial tumorigenesis

Introduction

Signal transducers and activators of transcription (Stats) are a family of latent cytoplasmic transcription factors that transduce extracellular signals from the cell membrane to the nucleus [1]. Stats are comprised of seven family members consisting of Stat1, Stat2, Stat3, Stat4, Stat5A/B and Stat6 that are involved in many normal physiological processes including differentiation, cell growth, proliferation and apoptosis [2-5]. Stats are activated by a variety of factors such as cytokines, growth factors, hormones and oncogenic signals. Stats can be activated by receptor tyrosine kinases such as the epidermal growth factor receptor which possess intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity [2]. Stats can also be activated by receptors that lack intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity such as cytokine receptors [e.g. interferon gamma receptor (IFNγR), interleukin-6 receptor (IL-6R)] [3]. These receptors activate Stat proteins by means of a class of receptor-associated kinases called Janus kinases (JAKs) [6-8]. Stats are constitutively activated in various mouse models of tumorigenesis, human cancer cell lines, solid neoplasms, and human blood malignancies [4,9-14]. Stat family members 1, 3, and 5 have been found most frequently to be constitutively activated in human tumors [4,15].

A critical role for Stat3 in epithelial multistage carcinogenesis in mouse skin has been established [10,16,17]. In this regard, Stat3 was shown to be important during the initiation phase of epithelial carcinogenesis by regulating keratinocyte survival, including survival of bulge-region keratinocyte stem cells [18,19] and for clonal expansion of initiated cells during tumor promotion [10,18,19]. Stat3 also appears to play an important role in the progression of skin tumors in this model system [10,20]. The role of other Stat family members, such as Stat1, in epithelial multistage carcinogenesis remains to be elucidated. Stat1, which is activated via IFN signaling [21-23], has been associated with anti-tumorigenic actions by modulating key components of immune tumor surveillance [24-26], inducing pro-apoptotic regulators such as Fas/FasL and caspases, and regulating negative cell cycle regulatory proteins such as p21 and p27 [27]. In contrast, other studies have suggested a pro-tumorigenic action of Stat1. In this regard, activation of Stat1 and/or overexpression of IFN-related genes in breast cancer have been associated with poor prognosis and resistance to radiation and adjuvant cancer therapy [28,29]. In addition, a role for activated Stat1 in promotion of leukemia development has also been reported [30]. A pro-tumorigenic role of IFNγ-Stat1 signaling has been suggested in melanoma [31,32]. Collectively, the available data suggest that Stat1 may exhibit both tumor suppressive effects as well as pro-tumorigenic effects depending on the tissue and/or cellular context.

The current study was undertaken to examine the role of Stat1 in skin tumor promotion using the mouse skin model of multistage carcinogenesis [33]. During the course of these studies, it was discovered that skin tumor promotion by the anthrone tumor promoter, chrysarobin (CHRY), is mediated by a novel signaling pathway involving Stat1 activation (phosphorylation) and upregulation of interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) via upregulation of IFNγand IFNγ receptor (IFNγR) signaling in the epidermis. This pathway is not activated by the phorbol ester tumor promoter 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA). Thus, under certain conditions Stat1 may have a pro-tumorigenic role during the promotion stage of epithelial carcinogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA), bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), proteinase inhibitor cocktails, phosphatase inhibitor cocktails, anti-actin and anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). TPA was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). CHRY was prepared from chrysophanic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) according to a published method [34]. All procedures with CHRY were performed under low intensity yellow lights. Antibodies against phosphorylated Stat1 (Y701 or S727) and total Stat1 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-IRF-1 and IFNγRβ antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and anti-Cox-2 antibody was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Chemiluminescence detection kits were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA). The recombinant IFNγrIFNγ was purchased from BD Bioscience (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Animals

Female FVB/N mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute and used when 7-9 weeks of age. All mice were group-housed and all experiments were conducted in accordance with NIH and institutional guidelines. Stat1-/- mice were a generous gift from Dr. David Levy from the Kaplan Cancer Center, New York School of Medicine. Stat1-/- mice were originally generated on a mixed C57Bl/6 genetic background [35] and were backcrossed for at least five generations onto the FVB/N background before use. Heterozygous knockout (KO) mice were then mated to generate Stat1-/- and Stat1+/+ littermate control mice. Genotypes were determined by PCR analysis of DNA isolated from tail snips using the following primers: (ST11) 5′-GATATAATTCACAAAATCAGAGAG-3′, (ST12) 5′- CTGATCCAGGCAGGCGTTG-3′, (ST13) 5′- TAATGTTTCATAGTTGGATATCAT-3′ in a multiplex reaction utilizing 0.2 mM dNTPs and AmpliTaq DNA polymerase with Buffer I (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) with an annealing temperature of 55°C and 33 amplification cycles to detect both wild-type and mutant products (450 and 150 bp, respectively). IFNγR1 KO mice and C57BL/6 wild-type control mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA).

Preparation of Epidermal Protein Lysates and Western Blot Analyses

Groups of 3-4 mice were shaved on the dorsal skin and treated a total of four times with acetone vehicle (0.2 mL), 6.8 nmol of TPA (2x/week for 2 weeks) or 220 nmol CHRY (1x/week for 4 weeks) and then sacrificed at the indicated times. Preparation of epidermal protein lysates and Western blot analyses were performed as previously described [36,37].

Histological Analyses

To evaluate epidermal hyperplasia and LI, the dorsal skin of mice (3-4 mice per group) was shaved, and then topically treated with either 0.2 ml of acetone (vehicle), 6.8 nmol of TPA (2x/week for 2 weeks) or 220 nmol CHRY (1x for 4 weeks). Mice were sacrificed 48 hours after the last treatment. Thirty min prior to sacrifice, mice received an i.p. injection of BrdU (100 μg/g body weight) in phosphate-buffered saline. Dorsal skin samples were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or anti-BrdU antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). Epidermal thickness and labeling index (LI) were determined as described previously [36,38].

Two-Stage Skin Carcinogenesis

Groups of mice for each genotype were used for the two-stage skin carcinogenesis studies as follows: Wild-type, TPA (n=29); Stat1-/-, TPA (n=24); wild-type, CHRY (n=24) and Stat1-/-, CHRY (n=19). For initiation, the dorsal skin of mice was shaved and 48 hours later, all mice received a topical application of 25 nmol of DMBA in 0.2 ml acetone to the shaved dorsal skin. Two weeks after initiation, mice were treated topically with either 6.8 nmol TPA (twice-weekly) or 220 nmol CHRY (once-weekly) in 0.2 mL acetone. The incidence and multiplicity of papillomas was recorded weekly until the average number of papillomas reached a plateau. Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) were recorded beginning at the time the first SCC was noted. All SCCs were histologically verified at the end of the experiment as described [33,39,40].

Adult Primary Keratinocyte Culture

Preparation and culture of adult mouse primary keratinocytes from Stat1-/- and Stat1+/+ mice was performed as previously described [37,41]. Primary keratinoctyes were serum starved for 24 hours prior to treatment with rIFNγ (100 ng/ml).

Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Fractionation

Primary keratinocytes from Stat1+/+ mice were serum starved for 24 hours, stimulated with rIFNγ (100 ng/ml) and subjected to cellular fractionation using an NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Total RNA Isolation and Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Epidermal scrapings from the dorsal skin of sacrificed mice were submerged in RNAlater and stored at 4°C for a minimum of 48 hours. Total RNA was isolated using the QIAGEN RNeasy RNA Isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were treated with RNAse-free DNAse (Life Technologies) and first strand synthesis using random hexamer primers (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) was used for cDNA preparation. RT-qPCR using SYBR Green dye PCR product incorporation and the primers listed in Supplemental Table 1 was performed on an Applied Biosystems Viia7 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX, USA).

Statistical Analyses

For comparisons of quantitative Western blot data, epidermal thickness, epidermal LI and tumor multiplicity, the Mann-Whitney U-test was used (p<0.05). For comparison of tumor incidence the Chi square (χ2) test was used (p<0.05).

Results

Examination of Stat1 Activation in Mouse Epidermis following Treatment with Tumor Promoters

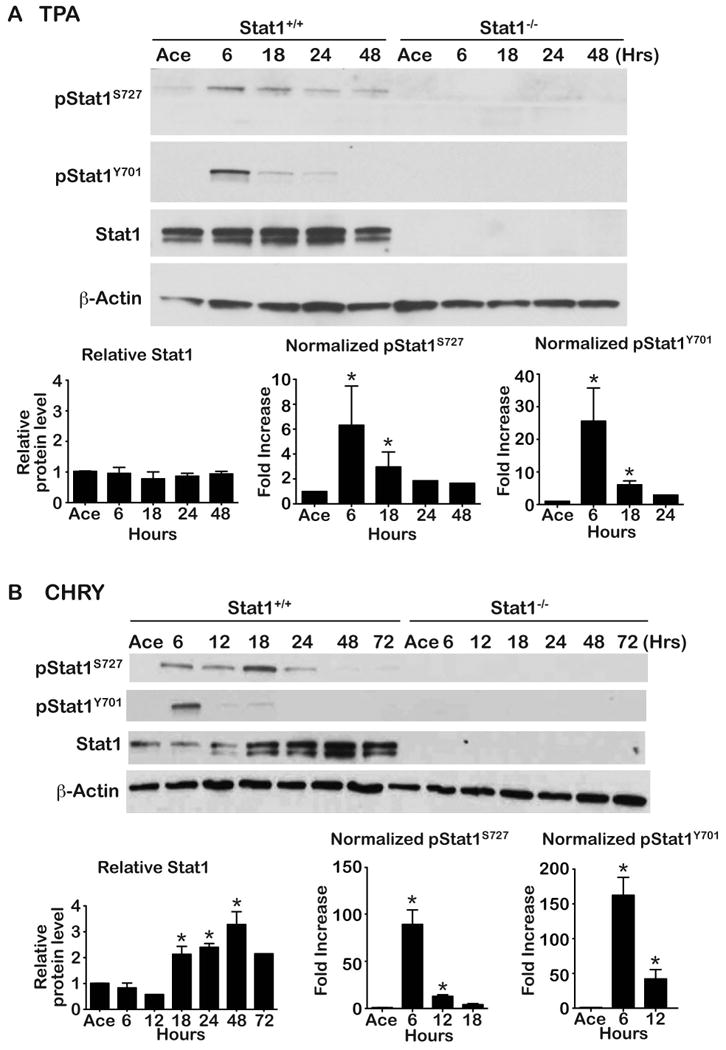

We previously reported that treatment of mouse epidermis with TPA led to activation (i.e., tyrosine phosphorylation) of Stat1 [42]. To further evaluate Stat1 activity in response to treatment with diverse classes of tumor promoters, total Stat1 and Stat1 phosphorylation status was assessed following treatment with both TPA and CHRY. For these experiments, the dorsal skins of FVB/N mice were treated topically with either 0.2 mL acetone (vehicle), TPA (6.8 nmol) given 2x/week for 2 weeks, or CHRY (220 nmol) given 1x/week for 4 weeks. Mice were then sacrificed at various time points following the last treatment. As shown in Figure 1, topical application of mouse epidermis with both TPA and CHRY induced phosphorylation of Stat1 on both tyrosine (Y701) and serine (S727) residues (pStat1Y701 and pStat1S727, respectively) at the earliest time point examined (6 hours) as well as later time points. During the course of these experiments, we observed that Stat1 protein levels were consistently increased at later time points following treatment with CHRY but not TPA (compare Figures 1A and 1B) with a peak occurring approximately 48 hours after the last CHRY treatment. This increase in Stat1 protein level occurred at a time when little or no phosphorylation could be detected at either site. Thus, CHRY treatment led to the induction of unphosphorylated Stat1 (uStat1). No activation of Stat1 was observed in epidermis of Stat1-/- mice as expected.

Figure 1. Analysis of Stat1 phosphorylation and protein level following tumor promoter treatment.

Stat1+/+ or Stat1-/- mice received either (A) TPA (6.8 nmol 2x/week for 2 weeks) or (B) 220 nmol CHRY (1x/week for 4 weeks) in 0.2 mL acetone (Ace). Epidermal lysates were prepared at the indicated time points for protein analysis by Western blot using antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. Protein level was quantitated by densitometry. β-Actin was used to normalize protein loading. Western blots in panels A and B are from a single representative experiment using pooled protein samples from groups of 3-5 mice. All quantitative values (given as mean ± SEM) are relative to the acetone control group (given a value of 1). For some time points where error bars are not shown, the value represents an average of only two independent experiments whereas all time points with error bars represent an average from at least three independent experiments. * Indicates value was significantly different from the acetone control group (Mann-Whitney U-test, p<0.05).

Further analyses revealed that the increase in uStat1 protein was due to an increase in Stat1 mRNA as shown in Supplemental Figure 1. Stat1 mRNA levels increased as early as 6 hours (the earliest time point examined) after treatment with CHRY with a peak at 12 hours.

Examination of IRF-1 Expression following Treatment with Tumor Promoters

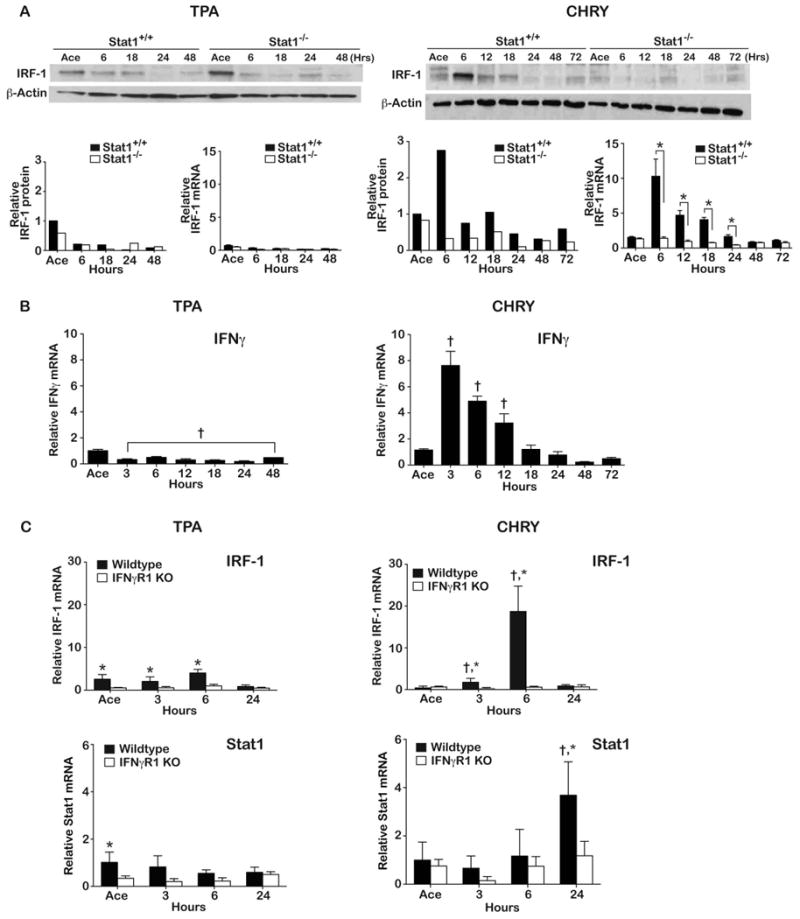

In light of the data in Figure 1 showing induction of uStat1 following treatment of mouse epidermis with CHRY we examined the status of IRF-1. IRF-1 is an IFNγ/pStat1 responsive transcription factor that is known to regulate expression of a variety of genes, including uStat1 [43]. As shown in Figure 2A, treatment with CHRY but not TPA led to an increase in IRF-1 expression (both mRNA and protein). In addition, examination of Stat1-/- mice showed that they were resistant to the induction of IRF-1 mRNA and protein following treatment with CHRY compared to wild-type FVB/N controls. Notably, treatment with TPA had no effect on the levels of IRF-1 mRNA and protein regardless of the genotype of the mice.

Figure 2. Examination of the IFNγ/pStat1/IRF-1 signaling axis in response to tumor promoter treatment.

Stat1+/+ or Stat1-/- mice received either TPA (6.8 nmol 2x/week for 2 weeks) or 220 nmol CHRY (1x/week for 4 weeks) in 0.2 mL acetone (Ace). (A) Mice were sacrificed at the indicated time points and epidermal lysates prepared for IRF-1 protein (Western blot) and mRNA expression (qPCR) analyses. Total protein levels were quantitated by densitometry. β-Actin was used to normalize protein loading. Western blot data are from a single experiment (pooled protein samples) that has been repeated with similar results. The mRNA data is presented as mean ± SD and was obtained from individual mice (n=3-5/group). *Indicates values between Stat1+/+ and Stat1-/- groups were significantly different (Mann-Whitney U-test, p<0.05). (B) IFNγ mRNA levels following topical application of TPA and CHRY to FVB/N wild-type mice. Values shown represent the mean ± SEM. † Indicates value was significantly different than that of the acetone control group. (C) Epidermal IRF-1 and Stat1 mRNA levels following topical application of TPA and CHRY to IFNγR1 KO and wild-type mice. Values shown are the mean ± SD. †Indicates values significantly different from the acetone control group (p<0.05); *indicates values between KO and wild-type mice were significantly different (Mann-Whitney U-test, p<0.05).

Role of IFNγ in the Upregulation of IRF-1 and uStat1 by CHRY

The data shown in Figures 1 and 2A suggested that CHRY treatment led to tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat1 via a different signaling pathway compared to TPA, possibly involving IFNγ signaling. To further explore this hypothesis, we examined the expression of IFNγ following topical treatment with both tumor promoters. For these experiments, FVB/N mice were again treated using a multiple treatment protocol. Epidermal lysates were prepared and RNA isolated for qPCR as described in the Materials and Methods. As shown in Figure 2B, treatment with TPA did not induce epidermal IFNγ mRNA and, in fact, led to a statistically significant decrease at all time points examined. In contrast, treatment with CHRY led to a significant increase in epidermal IFNγ mRNA at 3, 6 and 12 hours after treatment with a peak at ∼3 hours after the last treatment (∼8-fold increase compared to the control mice treated with acetone).

As shown in Figure 2C, topical treatment with TPA did not induce IRF-1 mRNA in either wild-type or IFNγR1 KO mice whereas treatment with CHRY induced a significant increase in epidermal IRF-1 mRNA in wild-type mice but not in epidermis of IFNγR1 KO mice. Thus, CHRY treatment leads to activation of IFNγ signaling in the epidermis whereas this does not occur following treatment with TPA. We also examined the level of Stat1 mRNA following treatment with either promoter and found an induction of Stat1 mRNA in wild-type epidermis by 24 hours after CHRY treatment (Figure 2C). However, no statistically significant increase in Stat1 mRNA was observed in the IFNγR1 KO mice at any of the time points examined after treatment with CHRY.

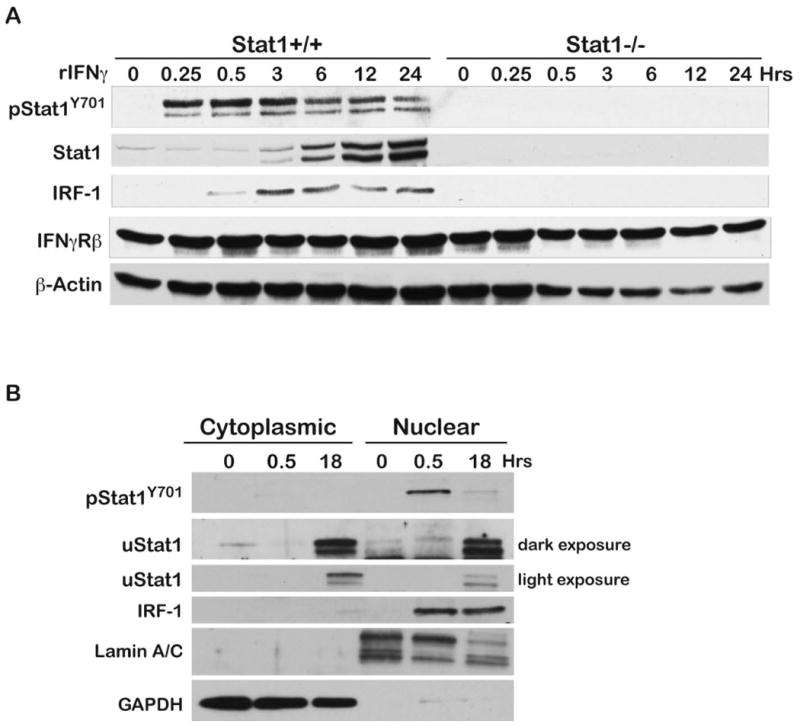

IFNγ Induces IRF-1 and uStat1 in Mouse Primary Keratinoctyes

To demonstrate that mouse keratinocytes have an intact IFNγR signaling pathway, primary mouse keratinocytes were treated with rIFNγ. Treatment of wild-type keratinocytes with rIFNγ (Figure 3A) led to a rapid increase in pStat1Y701 as early as 15 min following stimulation. rIFNγ stimulation also caused an increase in IRF-1 protein that was first evident at 30 min and persisted until the end of the experiment (24 hours). Total Stat1 (uStat1) also increased beginning as early as 3 hours and persisted throughout the duration of the experiment. In contrast, no upregulation of either IRF-1 or uStat1 protein was observed in primary keratinocytes from Stat1-/- mice treated with rIFNγ as expected. As shown in Figure 3B, rIFNγ stimulation of wild-type keratinocytes led to an increase in nuclear pStat1Y701 at 30 min, which subsided but was still evident at the 18-hour time point. Interestingly, uStat1 remained localized to the nucleus 18 hours after stimulation. In addition, nuclear IRF-1 protein levels increased 30 min following treatment and remained localized in the nucleus at 18 hours.

Figure 3. rIFNγ induces IRF-1 and uStat1 in primary keratinocytes.

Primary keratinocytes were isolated from adult Stat1+/+ and Stat1-/- mice as described in the Materials and Methods section. (A) Serum starved primary keratinocytes were stimulated with rIFNγ (100 ng/ml) and protein lysates were prepared for Western Blot analysis at the indicated time points. (B) Stat1+/+ primary keratinocytes were treated with rIFNγ as above and cellular fractionation was conducted as described in the Materials and Methods section. Western blot analyses were performed on protein lysates prepared from cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Lamin A/C and GAPDH were used as nuclear and cytoplasmic loading controls, respectively.

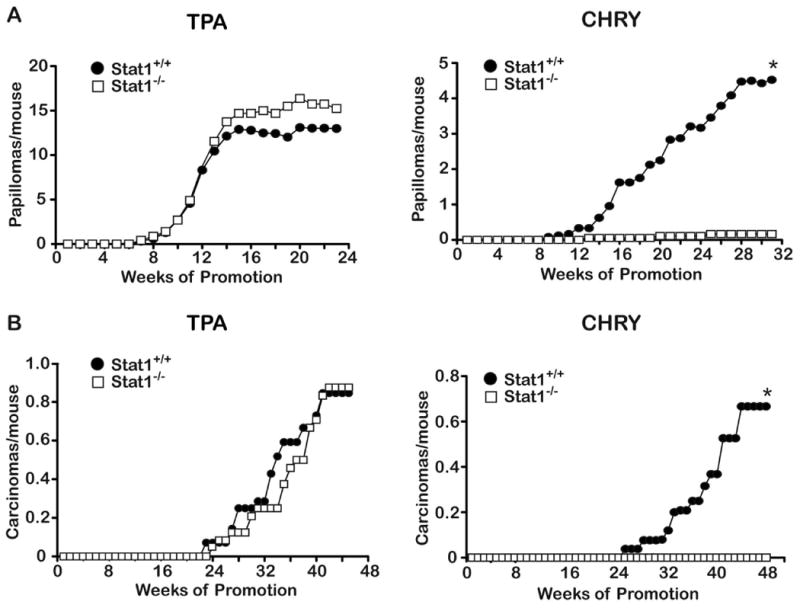

Effect of Stat1 Deficiency on Tumor Promotion and Epithelial Carcinogenesis

To further determine the role of Stat1 signaling in tumor promotion and epithelial carcinogenesis, we compared wild-type mice with Stat1-/- mice for their susceptibility to two-stage skin carcinogenesis using either TPA or CHRY as promoters. Groups of wild-type and Stat1-/- mice were initiated with 25 nmol of DMBA and two weeks later promoted either twice-weekly with topical applications of 6.8 nmol TPA or once-weekly with topical applications of 220 nmol CHRY. As shown in Figure 4, Stat1 deficiency had no significant effect on two-stage skin carcinogenesis when TPA was used as the promoting agent. In this regard, there was no significant difference in the average number of papillomas or SCCs per mouse (panels A and B, respectively) or tumor incidence (data not shown) in Stat1-/- mice compared to wild-type controls (p>0.05; Mann-Whitney U-test).

Figure 4. Impact of Stat1 deficiency on skin tumor promotion.

Groups of mice of each genotype (Stat1+/+or Stat1-/-) were initiated with 25 nmol DMBA; two weeks after initiation, mice were treated topically 2x/week with 6.8 nmol TPA or 1x/ week with 220 nmol CHRY until the tumor response reached a plateau. Significant differences in tumor multiplicity between groups were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U-test. *Indicates value is significantly different than acetone control (p<0.05).

In contrast to the results obtained with TPA as the promoter, Stat1-/- mice were highly resistant to two-stage skin carcinogenesis when CHRY was used as the tumor promoter. In this regard, Stat1-/- mice developed far fewer papillomas compared to wild-type controls (Figure 4). By week 31, Stat1-/- mice had only developed an average of 0.16 papillomas/mouse compared to 4.52 papillomas/mouse in the control group. This difference was highly statistically significant (p<0.0001, Mann Whitney U-test). At the time of study termination, the papillomas that had developed in Stat1-/- mice had not converted to SCCs, while the control mice had 0.66 SCCs per mouse (see again Figure 4).

We also compared the epidermal proliferative response following treatment with both tumor promoters in wild-type and Stat1-/- mice. The proliferative response was assessed through measuring epidermal thickness and LI 48 hours after the last treatment with either TPA or CHRY as previously described [36,38]. As shown in Supplemental Figure 2, there were no significant differences in the proliferative response following treatment with TPA between wild-type and Stat1-/- mice. In contrast, Stat1-/- mice had a reduced proliferative response as seen in the reduced LI following treatment with CHRY at all three doses used (100, 220 and 440 nmol) and a reduction in epidermal thickness at the highest dose tested (see Supplemental Figure 3).

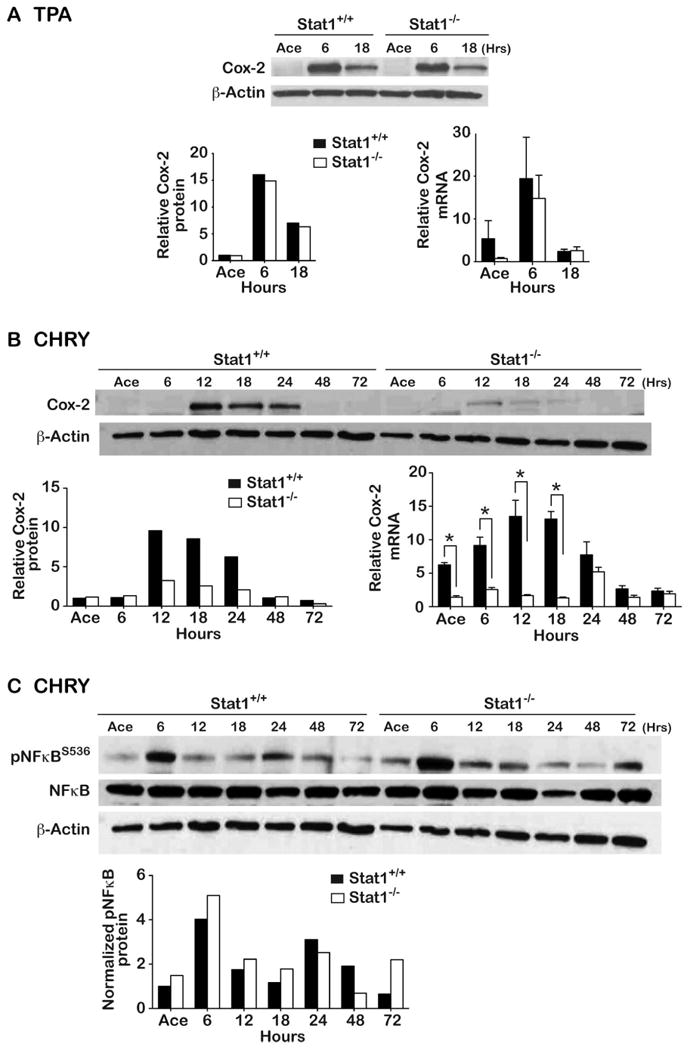

Effect of Stat1 Deficiency on Cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox-2) Expression and NFκB Activation following Topical Treatment with TPA and CHRY

To further explore potential mechanisms whereby IFNγ/pStat1/IRF-1 signaling mediates skin tumor promotion by CHRY but not TPA, we examined the status of Cox-2 expression (both mRNA and protein) following topical treatment with TPA and CHRY in both wild-type and Stat1-/- mice. As shown in Figure 5a, topical treatment with TPA led to an increase in Cox-2 expression (both mRNA and protein) as early as 6 hours after the last treatment that was similar in both wild-type and Stat1-/- mice. In contrast, Stat1-/- mice exhibited an approximate 3-fold reduction in Cox-2 protein levels and an even greater reduction in Cox-2 mRNA at the 12-hour time point compared to wild-type controls treated with CHRY (Figure 5B). The observed difference of Cox-2 levels in Stat1-/- mice persisted until levels reached baseline values at 48 hours following treatment with CHRY. Experiments evaluating Cox-2 expression levels with both tumor promoters were repeated with very similar results (see Supplemental Figure 4A). As expected, Stat1-/- mice treated with CHRY exhibited a decrease in epidermal prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) levels compared to wild-type mice, whereas no differences in epidermal PGE2 levels were observed between the two genotypes treated with TPA (see Supplemental Figure 4B).

Figure 5. Impact of Stat1 deficiency on Cox-2 induction following treatment with TPA and CHRY.

Stat1+/+ or Stat1-/- mice received topical applications of either acetone (Ace) or 6.8 nmol TPA given 2x/week for 2 weeks, or 220 nmol CHRY given 1x/week for 4 weeks and were sacrificed at the indicated time points. Epidermal lysates were prepared for both Western blot and qPCR analysis. (A) Cox-2 expression following TPA treatment. (B) Cox-2 expression following CHRY treatment. (C) NFκB status following treatment with CHRY. Western blot data are from a single experiment (pooled protein samples) that has been repeated with very similar results. The mRNA data is presented as the average ± SD from individual mice (n=5/group). *Indicates values between Stat1+/+ and Stat1-/- groups were significantly different by Mann-Whitney U-test (p<0.05).

As shown in panel C of Figure 5, the reduced expression of Cox-2 in epidermis of Stat1-/- mice observed following treatment with CHRY occurred in the presence of apparently normal NFκB signaling as seen by similar levels of pNFκBS536 in both genotypes. We also evaluated the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNos). As shown in Supplemental Figure 5A, topical treatment with TPA led to an increase in iNos mRNA levels at 6 hours, which quickly returned to basal levels at 12 hours following treatment. No differences were seen in this response to TPA in Stat1-/- mice compared to wild-type mice. In contrast, treatment with CHRY led to a significant increase in iNos mRNA levels in wild-type but not Stat1-/- mice (Supplemental Figure 5B).

Discussion

This paper represents the first report that topical treatment with CHRY leads to upregulation of IFNγ and IFNγR signaling in mouse epidermis. There are many different types of mouse skin tumor promoters and the similarities and differences between the different types and classes have been reviewed extensively [44-46]. A major difference between the anthrone type tumor promoters and the phorbol ester tumor promoters such as TPA is that the latter directly activate PKC isozymes. In contrast, anthrone tumor promoters such as CHRY do not directly activate PKC and undergo autoxidation to generate both reactive oxygen species (ROS) as well as carbon centered radicals as part of their mechanism of action [44,47]. Collectively, the current data demonstrate a novel mechanism of skin tumor promotion involving IFNγ/pStat1/IRF-1 signaling and upregulation of uStat1 in keratinocytes for anthrone skin tumor promoters of which CHRY is the most potent and prototypical member [48,49]. Notably, this pathway does not appear to play a major role in skin tumor promotion by TPA.

The possible role of IFNγ in skin tumor promotion by TPA has previously been explored with conflicting results. In earlier studies, Reiners and colleagues [50] reported that IFNγ acted as a co-promoter when injected i.p. together with topical application of TPA. IFNγ given alone (via i.p. injection) did not promote skin tumors in mice initiated with DMBA in these earlier studies. More recently, the role of IFNγ signaling in tumor promotion by TPA has been explored more directly using genetically engineered mouse models. In this regard, Xiao et al. reported that IFNγ mRNA levels were elevated in RNA samples isolated from whole skin following treatment with DMBA and either a single or multiple treatments with TPA [51]. In addition, these authors reported that Stat1 was activated in protein lysates isolated from whole skin 24 hours following the last TPA treatment. In this same study, administration of an anti-IFNγ antibody or using IFNγ receptor deficient mice reduced the number of papillomas but had no effect on the incidence of SCCs in a two-stage carcinogenesis protocol. In contrast to these data, Wang et al. [52] reported that IFNγ-/- mice had a nearly identical tumor response (both the percentage of mice with papillomas and papillomas per mouse) when compared with wild-type mice undergoing a two-stage (DMBA-TPA) protocol. Our current data support the conclusion that IFNγ signaling via Stat1 and IRF-1 is not involved in skin tumor promotion by TPA. However, the current data may explain the co-promoting effects of IFNγ as well as previous data showing that low doses of CHRY could also act as a co-promoter when given together with TPA [48]. Further work in this latter area would seem warranted.

As noted in the Introduction, several reports have indicated a possible pro-tumorigenic role for Stat1 [30,32,53] although other studies have supported a tumor suppressor role for this signaling molecule. In a previous study, Schreiber et al. reported that IFNγR-/- and Stat1-/- mice were highly susceptible to tumor formation compared to 129/Sv control mice following a single subcutaneous injection of the carcinogen 3-methylcholanthrene (MCA) [54]. In this study the authors also reported that Stat1-/-/p53-/- double KO mice developed tumors more rapidly and with greater frequency than p53-/- mice, when challenged with MCA. Other studies have also shown that IFNγ plays an important role in immune surveillance for chemically induced tumors, including skin tumors [55-57]. In contrast, Hanada et al. [58] reported that mice deficient in suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS1), a negative regulator of STAT signaling, developed spontaneous colorectal carcinomas dependent on IFNγ. In this study, IFNγ-/-/SOCS1-/- mice failed to develop tumors regardless of the upregulation of Stat3 responsive genes such as Bcl-XL and c-myc when compared to the SOCS1-/- deficient mice. These and additional data suggested a critical role for the IFNγ/Stat1 signaling in the development of colorectal tumors in this mouse model. The current data clearly demonstrate an important role for Stat1 activation via IFNγ signaling in epidermis in mediating skin tumor promotion by CHRY. Perhaps Stat1 activation via IFNγ signaling has opposing roles during epithelial carcinogenesis in mouse skin: a pro-tumorigenic role during the early tumor promotion stage and an immune surveillance function once tumors have developed. Further ongoing studies using conditional Stat1 KO mice will help to address these ideas in more detail. In addition, identification of the cells in the epidermis that produce IFNγ in response to CHRY treatment is currently being pursued.

The mechanism(s) for how Stat1 mediates skin tumor promotion by CHRY remain to be fully determined. As shown in Supplemental Figure 3, Stat1-/- mice treated with CHRY had a reduced proliferative response as measured by BrdU incorporation and epidermal thickness. However, the decrease in epidermal proliferation seen in Stat1-/- mice in response to treatment with CHRY did not appear sufficient to explain the dramatic inhibition of skin tumor promotion by CHRY seen in these mice (Figure 4). Stat1 has been shown to regulate the production of pro-inflammatory molecules such as iNos and Cox-2 [59,60]. Furthermore, IFNγ is also known to upregulate a variety of inflammatory mediators including tumor necrosis factor alpha [61], interleukin-12 [62], gp91phox [63] and iNos [64,65]. IRF-1 is a Stat1 responsive transcription factor that acts as a secondary response to activate other downstream targets (i.e., iNos and Cox-2) [60,66-68]. As shown in Figure 2, treatment with CHRY led to upregulation of IRF-1 that was blocked in both Stat1-/- and IFNγR1-/- mice (Figures 2A and 2C, respectively). Both TPA and CHRY treatment led to upregulation of epidermal Cox-2 expression (both mRNA and protein; Figure 5). Furthermore, the upregulation of Cox-2 (and PGE2) by CHRY but not TPA was dependent on activation of Stat1. Similar results were obtained for the upregulation of iNos by both compounds (Supplemental Figure 5). The reduction in Cox-2 and iNos expression in Stat1-/- mice compared to wild-type mice following treatment with CHRY occurred in the presence of apparently normal activation of NFκB (Figure 5C) further demonstrating the importance of Stat1 signaling in mediating skin tumor promotion by CHRY. The induction of Cox-2 and the increased production of prostaglandins such as PGE2 represent important events in the process of skin tumor promotion [69-71]. Therefore, pStat1/IRF-1 regulation of the induction of Cox-2 and iNos by CHRY may explain, at least in part, some of the mechanism associated with skin tumor promotion by this compound.

Another interesting observation in the current study was the induction of uStat1 by CHRY but not TPA (Figure 1). These results are consistent with recent studies showing that Stats 1 and 3 can function to regulate gene expression in the absence of tyrosine phosphorylation including regulating their own expression [72,73]. As a result, activation of Stat1 or Stat3 can lead to the induction and accumulation of uStats 1 and 3, which may persist for days after pStat levels have subsided [73]. In addition, induction of the Stat1 target gene, IRF-1, aids in the continued accumulation of uStat1 in response to IFNγ. It is well documented that uStats 1 and 3 can act as transcription factors and regulate a subset of genes that are different from those regulated by pStats [72,74,75]. Together these data suggest that uStat1 may be transcriptionally active and play a significant role in skin tumor promotion by CHRY. Transcriptional profiling has shown that the majority of uStat1 target genes are antiviral immune response genes, however uStat1 also induces a subset of genes implicated in radio- and chemo-resistance in cancer cells [76]. Disruption of IRF-8 in soft tissue sarcoma cells leads to the accumulation of uStat1 and promotes sarcoma cell metastasis by regulating transcription of apoptosis regulators Fas and Bad [77]. Future studies are aimed at defining the role of uStat1 in skin tumor promotion by CHRY.

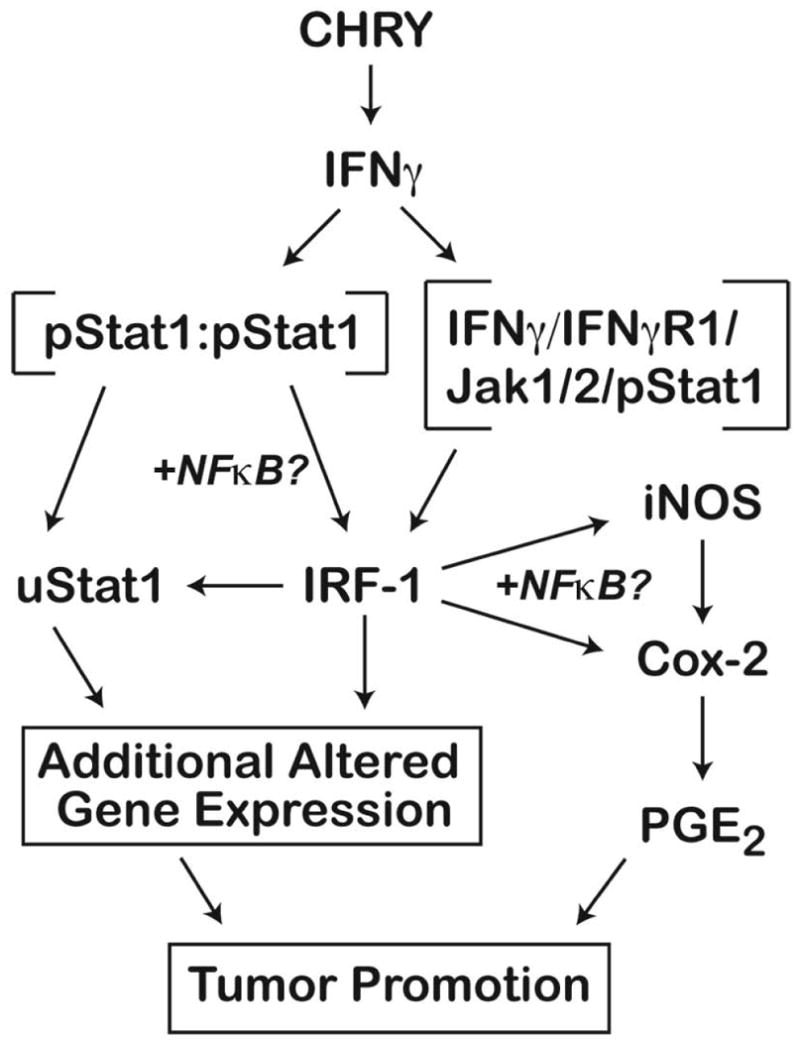

In conclusion, the current data identify a novel mechanism for skin tumor promotion involving activation of IFNγ signaling via pStat1 and IRF-1 that is required for the skin tumor promoting activity of CHRY, a member of the anthrone class of skin tumor promoters [44,49,78]. This mechanism does not appear to play a major role in skin tumor promotion by the phorbol ester, TPA. The mechanism(s) may involve the canonical pathway involving formation of pStat1 homodimers, which leads to direct transcriptional regulation of IRF-1 and uStat1. Alternatively, or in addition, this could involve a recently identified non-canonical pathway involving the translocation of a complex containing IFNγR1-JAKS1/2-pStat1 to the nucleus where it binds to the IRF-1 promoter and induces transcription of IRF-1 [79,80]. Upregulated IRF-1 then leads to increased transcription of a number of genes, including uStat1, iNos and Cox-2 as well as others that ultimately contribute to the skin tumor promoting action of CHRY. Furthermore, both pStat1 and IRF-1 have been shown to interact with NFκB [81,82], which may also play a role in altered expression of some genes. Figure 6 proposes a working model for the role of IFNγ/pStat1/IRF-1 signaling and uStat1 in skin tumor promotion by CHRY encompassing the various aspects discussed above. Further understanding of the downstream effectors of this novel skin tumor promotion pathway will aid in our understanding of the process of tumor promotion in general and in the identification of novel targets for cancer prevention. Because the generation of ROS plays a significant role in ultraviolet radiation-mediated skin carcinogenesis [83-85] current studies are now focused on determining the possible involvement of this novel pathway in the promotion stage associated with UV-mediated non-melanoma skin carcinogenesis.

Figure 6. Working model for the role of IFNγ/pStat1/IRF-1 signaling and uStat1 in skin tumor promotion by CHRY.

Treatment of mouse skin with CHRY leads to the upregulation of IFNγ in the epidermis. The actual cellular source of the IFNγ produced in the epidermis after treatment with CHRY is not known at the present time. Increased levels of IFNγ lead to activation of its receptor on keratinocytes and subsequent downstream signaling events. Because both TPA and CHRY cause an initial activation (i.e., phosphorylation) of Stat1, the subsequent induction of IRF-1 and uStat1 must occur through a process unique to this pathway. Several mechanisms could explain this difference and may involve both the canonical (pStat1 homodimers) as well as a novel non-canonical pathway involving the translocation of a complex containing IFNγR1/Jak2/pStat1 to the nucleus where it binds to the IRF-1 promoter and induces transcription of IRF-1. Upregulated IRF-1 then leads to increased transcription of a number of genes, including uStat1, iNos and Cox-2 as well as others that ultimately contribute to the skin tumor promoting action of CHRY. Both pStat1 and IRF-1 have been shown to interact with NFκB, which may also play a role in altered expression of some genes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grant CA076520 (J. DiGiovanni) and the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Support grant CA016672.

Abbreviations

- IFNγ

interferon gamma

- Stat1

signal transducer and activator of transcription-1

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

- CHRY

(chrysarobin), 3-methyl-1,8-dihydroxy-9-anthrone

- uStat1

unphosphorylated Stat1

- IRF-1

interferon regulatory factor 1

- DMBA

7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene

- BrdU

bromodeoxyuridine

- rIFNγ

recombinant IFNγ

- KO

knockout

- LI

labeling index

- SCC(s)

squamous cell carcinomas

- Cox-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- iNos

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- MCA

3-methylcholanthrene

- SOCS1

suppressor of cytokine signaling-1

References

- 1.Darnell JE., Jr STATs and gene regulation. Science. 1997;277(5332):1630–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catlett-Falcone R, Dalton WS, Jove R. STAT proteins as novel targets for cancer therapy. Signal transducer an activator of transcription Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11(6):490–496. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199911000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calo V, Migliavacca M, Bazan V, et al. STAT proteins: from normal control of cellular events to tumorigenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2003;197(2):157–168. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bromberg J. Stat proteins and oncogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(9):1139–1142. doi: 10.1172/JCI15617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akira S. Functional roles of STAT family proteins: lessons from knockout mice. Stem Cells. 1999;17(3):138–146. doi: 10.1002/stem.170138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schindler C, Levy DE, Decker T. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282(28):20059–20063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiu H, Nicholson SE. Biology and significance of the JAK/STAT signalling pathways. Growth Factors. 2012;30(2):88–106. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2012.660936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellegrini S, Dusanter-Fourt I. The structure, regulation and function of the Janus kinases (JAKs) and the signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1997;248(3):615–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston PA, Grandis JR. STAT3 signaling: anticancer strategies and challenges. Molecular interventions. 2011;11(1):18–26. doi: 10.1124/mi.11.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macias E, Rao D, Digiovanni J. Role of stat3 in skin carcinogenesis: insights gained from relevant mouse models. Journal of skin cancer. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/684050. 684050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greten FR, Weber CK, Greten TF, et al. Stat3 and NF-kappaB activation prevents apoptosis in pancreatic carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(6):2052–2063. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blando JM, Carbajal S, Abel E, et al. Cooperation between Stat3 and Akt signaling leads to prostate tumor development in transgenic mice. Neoplasia. 2011;13(3):254–265. doi: 10.1593/neo.101388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benavides F, Blando J, Perez CJ, et al. Transgenic overexpression of PKCepsilon in the mouse prostate induces preneoplastic lesions. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(2):268–277. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.2.14469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saini MK, Vaish V, Sanyal SN. Role of cytokines and Jak3/Stat3 signaling in the 1,2-dimethylhydrazine dihydrochloride-induced rat model of colon carcinogenesis: early target in the anticancer strategy. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2013;22(3):215–228. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3283584932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Shea JJ, Holland SM, Staudt LM. JAKs and STATs in immunity, immunodeficiency, and cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368(2):161–170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1202117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim DJ, Chan KS, Sano S, Digiovanni J. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) in epithelial carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46(8):725–731. doi: 10.1002/mc.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sano S, Chan KS, DiGiovanni J. Impact of Stat3 activation upon skin biology: a dichotomy of its role between homeostasis and diseases. Journal of dermatological science. 2008;50(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan KS, Sano S, Kiguchi K, et al. Disruption of Stat3 reveals a critical role in both the initiation and the promotion stages of epithelial carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(5):720–728. doi: 10.1172/JCI21032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim DJ, Kataoka K, Rao D, Kiguchi K, Cotsarelis G, Digiovanni J. Targeted disruption of stat3 reveals a major role for follicular stem cells in skin tumor initiation. Cancer Res. 2009;69(19):7587–7594. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan KS, Sano S, Kataoka K, et al. Forced expression of a constitutively active form of Stat3 in mouse epidermis enhances malignant progression of skin tumors induced by two-stage carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2008;27(8):1087–1094. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA. Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75(2):163–189. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gough DJ, Levy DE, Johnstone RW, Clarke CJ. IFNgamma signaling-does it mean JAK-STAT? Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2008;19(5-6):383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(5):375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamiya S, Owaki T, Morishima N, Fukai F, Mizuguchi J, Yoshimoto T. An indispensable role for STAT1 in IL-27-induced T-bet expression but not proliferation of naive CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173(6):3871–3877. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee CK, Gimeno R, Levy DE. Differential regulation of constitutive major histocompatibility complex class I expression in T and B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1999;190(10):1451–1464. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.10.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meraz MA, White JM, Sheehan KC, et al. Targeted disruption of the Stat1 gene in mice reveals unexpected physiologic specificity in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Cell. 1996;84(3):431–442. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim HS, Lee MS. STAT1 as a key modulator of cell death. Cellular signalling. 2007;19(3):454–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magkou C, Giannopoulou I, Theohari I, et al. Prognostic significance of phosphorylated STAT-1 expression in premenopausal and postmenopausal patients with invasive breast cancer. Histopathology. 2012;60(7):1125–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weichselbaum RR, Ishwaran H, Yoon T, et al. An interferon-related gene signature for DNA damage resistance is a predictive marker for chemotherapy and radiation for breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(47):18490–18495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809242105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovacic B, Stoiber D, Moriggl R, et al. STAT1 acts as a tumor promoter for leukemia development. Cancer cell. 2006;10(1):77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zaidi MR, Merlino G. The two faces of interferon-gamma in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(19):6118–6124. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schultz J, Koczan D, Schmitz U, et al. Tumor-promoting role of signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)1 in late-stage melanoma growth. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2010;27(3):133–140. doi: 10.1007/s10585-010-9310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abel EL, Angel JM, Kiguchi K, DiGiovanni J. Multi-stage chemical carcinogenesis in mouse skin: fundamentals and applications. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(9):1350–1362. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auterhoff H, Scherff FC. Dianthrones of pharmacologically important hydroxyanthraquinones. Arch Pharm. 1960;293/65:918–925. doi: 10.1002/ardp.19602931007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durbin JE, Hackenmiller R, Simon MC, Levy DE. Targeted disruption of the mouse Stat1 gene results in compromised innate immunity to viral disease. Cell. 1996;84(3):443–450. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Checkley LA, Rho O, Moore T, Hursting S, DiGiovanni J. Rapamycin is a potent inhibitor of skin tumor promotion by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4(7):1011–1020. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim DJ, Tremblay ML, Digiovanni J. Protein tyrosine phosphatases, TC-PTP, SHP1, and SHP2, cooperate in rapid dephosphorylation of Stat3 in keratinocytes following UVB irradiation. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore T, Beltran L, Carbajal S, Hursting SD, Digiovanni J. Energy balance modulates mouse skin tumor promotion through altered IGF-1R and EGFR crosstalk. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5(10):1236–1246. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aldaz CM, Conti CJ, Chen A, Bianchi A, Walker SB, DiGiovanni J. Promoter independence as a feature of most skin papillomas in SENCAR mice. Cancer Res. 1991;51(3):1045–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim DJ, Angel JM, Sano S, DiGiovanni J. Constitutive activation and targeted disruption of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) in mouse epidermis reveal its critical role in UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2009;28(7):950–960. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu J, Rho O, Wilker E, Beltran L, Digiovanni J. Activation of epidermal akt by diverse mouse skin tumor promoters. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5(12):1342–1352. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan KS, Carbajal S, Kiguchi K, Clifford J, Sano S, DiGiovanni J. Epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated activation of Stat3 during multistage skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64(7):2382–2389. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen H, Lin R, Hiscott J. Activation of multiple growth regulatory genes following inducible expression of IRF-1 or IRF/RelA fusion proteins. Oncogene. 1997;15(12):1425–1435. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiGiovanni J. Multistage carcinogenesis in mouse skin. Pharmacol Ther. 1992;54(1):63–128. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90051-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fischer S. Chemical carcinogens and anticarcinogens. In: Bowden GT, Fischer SM, editors. Comprehensive Toxicology. Vol. 12. New York: Elsevier Science; 1997. pp. 349–381. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rundhaug JE, Fischer SM. Molecular Mechanisms of Mouse Skin Tumor Promotion. Cancers (Basel) 2010;2(2):436–482. doi: 10.3390/cancers2020436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DiGiovanni J, Kruszewski FH, Coombs MM, Bhatt TS, Pezeshk A. Structure-activity relationships for epidermal ornithine decarboxylase induction and skin tumor promotion by anthrones. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9(8):1437–1443. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.8.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DiGiovanni J, Boutwell RK. Tumor promoting activity of 1,8-dihydroxy-3-methyl-9-anthrone (Chrysarobin) in female SENCAR mice. Carcinogenesis. 1983;4:281–284. doi: 10.1093/carcin/4.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kruszewski FH, Conti CJ, DiGiovanni J. Characterization of skin tumor promotion and progression by chrysarobin in SENCAR mice. Cancer Res. 1987;47(14):3783–3790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reiners JJ, Jr, Rupp T, Colby A, Cantu AR, Pavone A. Tumor copromoting activity of gamma-interferon in the murine skin multistage carcinogenesis model. Cancer Res. 1989;49(5):1202–1206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiao M, Wang C, Zhang J, Li Z, Zhao X, Qin Z. IFNgamma promotes papilloma development by up-regulating Th17-associated inflammation. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):2010–2017. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang L, Yi T, Zhang W, Pardoll DM, Yu H. IL-17 enhances tumor development in carcinogen-induced skin cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70(24):10112–10120. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Timofeeva OA, Plisov S, Evseev AA, et al. Serine-phosphorylated STAT1 is a prosurvival factor in Wilms' tumor pathogenesis. Oncogene. 2006;25(58):7555–7564. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaplan DH, Shankaran V, Dighe AS, et al. Demonstration of an interferon gamma-dependent tumor surveillance system in immunocompetent mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(13):7556–7561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shankaran V, Ikeda H, Bruce AT, et al. IFNgamma and lymphocytes prevent primary tumour development and shape tumour immunogenicity. Nature. 2001;410(6832):1107–1111. doi: 10.1038/35074122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mumm JB, Emmerich J, Zhang X, et al. IL-10 elicits IFNgamma-dependent tumor immune surveillance. Cancer cell. 2011;20(6):781–796. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wakita D, Chamoto K, Ohkuri T, et al. IFN-gamma-dependent type 1 immunity is crucial for immunosurveillance against squamous cell carcinoma in a novel mouse carcinogenesis model. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(8):1408–1415. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanada T, Kobayashi T, Chinen T, et al. IFNgamma-dependent, spontaneous development of colorectal carcinomas in SOCS1-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2006;203(6):1391–1397. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ganster RW, Taylor BS, Shao L, Geller DA. Complex regulation of human inducible nitric oxide synthase gene transcription by Stat 1 and NF-kappa B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(15):8638–8643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151239498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blanco JC, Contursi C, Salkowski CA, DeWitt DL, Ozato K, Vogel SN. Interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-1 and IRF-2 regulate interferon gamma-dependent cyclooxygenase 2 expression. J Exp Med. 2000;191(12):2131–2144. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.12.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berner MD, Sura ME, Alves BN, Hunter KW., Jr IFN-gamma primes macrophages for enhanced TNF-alpha expression in response to stimulatory and non-stimulatory amounts of microparticulate beta-glucan. Immunol Lett. 2005;98(1):115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoshida A, Koide Y, Uchijima M, Yoshida TO. IFN-gamma induces IL-12 mRNA expression by a murine macrophage cell line, J774. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;198(3):857–861. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Almeida AC, Rehder J, Severino SD, Martins-Filho J, Newburger PE, Condino-Neto A. The effect of IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha on the NADPH oxidase system of human colostrum macrophages, blood monocytes, and THP-1 cells. Journal of interferon & cytokine research : the official journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research. 2005;25(9):540–546. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coccia EM, Stellacci E, Marziali G, Weiss G, Battistini A. IFN-gamma and IL-4 differently regulate inducible NO synthase gene expression through IRF-1 modulation. International immunology. 2000;12(7):977–985. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.7.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chan ED, Riches DW. IFN-gamma + LPS induction of iNOS is modulated by ERK, JNK/SAPK, and p38(mapk) in a mouse macrophage cell line. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280(3):C441–450. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.3.C441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin E, Nathan C, Xie QW. Role of interferon regulatory factor 1 in induction of nitric oxide synthase. J Exp Med. 1994;180(3):977–984. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leppanen T, Korhonen R, Laavola M, Nieminen R, Tuominen RK, Moilanen E. Down-regulation of protein kinase Cdelta inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase expression through IRF1. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e52741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fritsche G, Dlaska M, Barton H, Theurl I, Garimorth K, Weiss G. Nramp1 functionality increases inducible nitric oxide synthase transcription via stimulation of IFN regulatory factor 1 expression. J Immunol. 2003;171(4):1994–1998. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamamoto S, Jiang H, Otsuka C, Kato R. Involvement of prostaglandin E2 in ornithine decarboxylase induction by a tumor-promoting agent, 7-bromomethylbenz[a]anthracene, in mouse epidermis. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13(5):905–906. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.5.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fischer SM, Pavone A, Mikulec C, Langenbach R, Rundhaug JE. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression is critical for chronic UV-induced murine skin carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46(5):363–371. doi: 10.1002/mc.20284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ansari KM, Rundhaug JE, Fischer SM. Multiple signaling pathways are responsible for prostaglandin E2-induced murine keratinocyte proliferation. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6(6):1003–1016. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang J, Stark GR. Roles of unphosphorylated STATs in signaling. Cell research. 2008;18(4):443–451. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cheon H, Yang J, Stark GR. The functions of signal transducers and activators of transcriptions 1 and 3 as cytokine-inducible proteins. Journal of interferon & cytokine research : the official journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research. 2011;31(1):33–40. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chatterjee-Kishore M, Wright KL, Ting JP, Stark GR. How Stat1 mediates constitutive gene expression: a complex of unphosphorylated Stat1 and IRF1 supports transcription of the LMP2 gene. EMBO J. 2000;19(15):4111–4122. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang J, Liao X, Agarwal MK, Barnes L, Auron PE, Stark GR. Unphosphorylated STAT3 accumulates in response to IL-6 and activates transcription by binding to NFkappaB. Genes Dev. 2007;21(11):1396–1408. doi: 10.1101/gad.1553707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cheon H, Stark GR. Unphosphorylated STAT1 prolongs the expression of interferon-induced immune regulatory genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(23):9373–9378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903487106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zimmerman MA, Rahman NT, Yang D, et al. Unphosphorylated STAT1 promotes sarcoma development through repressing expression of Fas and bad and conferring apoptotic resistance. Cancer Res. 2012;72(18):4724–4732. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.DiGiovanni J, Boutwell RK. Tumor promoting activity of 1,8-dihydroxy-3-methyl-9-anthrone (chrysarobin) in female SENCAR mice. Carcinogenesis. 1983;4(3):281–284. doi: 10.1093/carcin/4.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ahmed CM, Johnson HM. IFN-gamma and its receptor subunit IFNGR1 are recruited to the IFN-gamma-activated sequence element at the promoter site of IFN-gamma-activated genes: evidence of transactivational activity in IFNGR1. J Immunol. 2006;177(1):315–321. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Johnson HM, Noon-Song EN, Kemppainen K, Ahmed CM. Steroid-like signalling by interferons: making sense of specific gene activation by cytokines. Biochem J. 2012;443(2):329–338. doi: 10.1042/BJ20112187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sgarbanti M, Remoli AL, Marsili G, et al. IRF-1 is required for full NF-kappaB transcriptional activity at the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat enhancer. Journal of virology. 2008;82(7):3632–3641. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00599-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ohmori Y, Schreiber RD, Hamilton TA. Synergy between interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in transcriptional activation is mediated by cooperation between signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 and nuclear factor kappaB. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(23):14899–14907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nishigori C. Cellular aspects of photocarcinogenesis. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2006;5(2):208–214. doi: 10.1039/b507471a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nishigori C, Hattori Y, Toyokuni S. Role of reactive oxygen species in skin carcinogenesis. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2004;6(3):561–570. doi: 10.1089/152308604773934314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen AC, Halliday GM, Damian DL. Non-melanoma skin cancer: carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Pathology. 2013;45(3):331–341. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e32835f515c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.