Abstract

Primary histiocytic sarcoma (HS) of the central nervous system (CNS) is a rare haematopoietic neoplasm. The inconsistent terminology and diagnostic criteria currently used for CNS HS have complicated the appreciation of the clinical aspects of the disease. The main differential diagnoses are non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, reactive histiocytic proliferation, dendritic cell neoplasm, undifferentiated carcinoma, inflammatory pseudotumour, Rosai-Dorfman disease and abscess. The true diagnosis of CNS HS requires an extensive immunophenotypic workup using specific histiocytic markers, such as CD163, with the exclusion of markers of other cell lineages. This clinicopathological case report describes an improved approach towards the differential diagnosis of CNS HS.

Background

True histiocytic sarcoma (HS), a malignant proliferation of cells showing signs of histiocytic differentiation, predominantly affects the middle-aged, often occurring in the skin, the lymph nodes and the intestinal tract.1 HS is commonly associated with haematological malignancies, but primary peripheral or central nervous system (CNS) involvement is rare, representing less than 1% of all lymphohaematopoietic neoplasms.2 However, the precise incidence of CNS HS remains undetermined not only because of the rarity of the neoplasm but also because of the disparity of the clinical and histopathological reports published.1 The recent development of specific molecular and biological markers, such as CD163, now allows the differential diagnosis between CNS HS and B-cell or T-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Following the definition of CNS HS by the WHO1 2 and the International Lymphoma Study Group,3 10 documented cases affecting the CNS HS have been reported.4–13 Since some patients with CNS HS may enjoy long-term disease-free survival after multidisciplinary treatment, the accurate diagnosis of the neoplasm is clearly of importance. We describe a primary CNS HS first manifesting in the form of multiple cranial nerve palsies.

Case presentation

A 63-year-old woman presented to our neurological department after suffering for 2 months from stabbing paraesthesia described as painful pins and needles together with a burning sensation in her left cheek. This constant, rather than episodic, paraesthesia started in the left maxillary nerve (V2) and worsened progressively to involve all three branches of the trigeminal nerve. She had no fever or weight loss. The patient had no notable medical history except for having undergone surgery with Harrington instrumentation for scoliosis as an adolescent. On neurological examination, the pinprick sensation was found to be decreased in the V1–V3 dermatomes of the left side of her face and dysaesthesia was noted in the right trigeminal area. A slight weakness of the left masseter was also detected.

Investigations

Brain MRI showed nodular gadolinium-enhanced lesions of both the trigeminal nerves and a slightly enhanced left pontic lesion on T1-weighted sequences (figure 1A), without oedema, but which was isointense on T2-weighted and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences, and hence difficult to appreciate. No perfusion image was performed. Spinal MRI was normal at the cervical level but uninterpretable below this level because of artefacts due to the insertion of the Harrington rod. The lumbar puncture (LP) revealed normal opening pressure, glucose and protein levels and 21/mm3 normal lymphocytes. Staining and cultures for bacteria and fungi, and PCR analyses for the Epstein-Barr virus, the varicella zoster virus, herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2, human herpes virus 6 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis were negative. The results of haematological and biochemical screening with antinuclear antibodies, Sjögren's syndrome-associated antibodies A and B, ACE, extractable nuclear antigen, thyroid function tests, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assays-Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (TPHA-VDRL) test, anti-HU, anti-Ri and anti-YO antibodies, Lyme, hepatitis B and C viruses and HIV serologies were all normal or negative. The salivary gland biopsy was normal. The bone marrow biopsy and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (PET)/whole-body CT showed no evidence of disease outside the CNS.

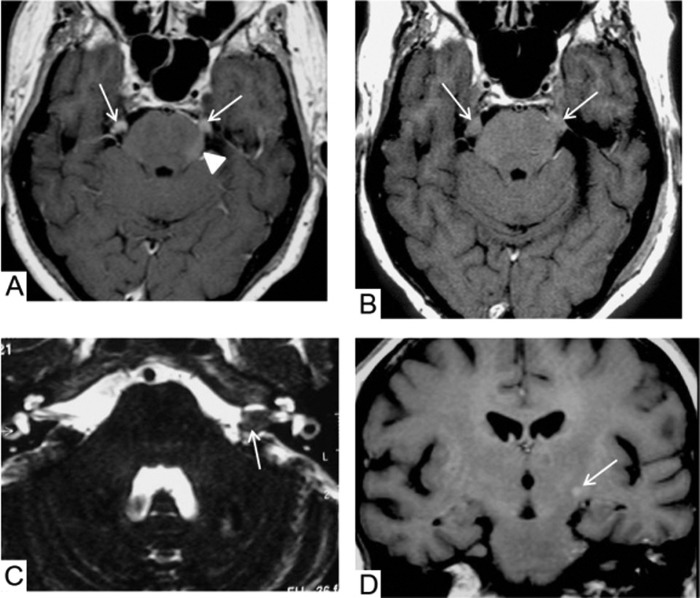

Figure 1.

Brain MRI. (A) On T1-weighted sequences, the first brain MRI shows nodular gadolinium-enhanced lesions of both trigeminal nerves (arrows) and a slightly enhanced left pontic lesion (arrow head) without oedema. (B) The second brain MRI, 3 months later, shows increased lesions on both the trigeminal nerves on T1-weighted images (arrows); (C) The T2-weighted images show masses on the left cochleovestibular and facial nerves (arrow); (D) The T1-weighted images show a small gadolinium-enhanced lesion in the left internal capsule (arrow).

Taking into account: (1) the subacute cranial neuropathy, (2) the absence of any signs of tumoral origin as all investigations including PET scan, whole-body CT scan and bone marrow examinations were normal and (3) the aspect of inflammatory granuloma revealed by the nodular enhancement of the trigeminal nerves that seemed to be swollen, an inflammatory condition was suspected and the patient treated with glucocorticoid therapy, that is, intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g daily for 5 days), with a tapering administration of prednisone per os (1 mg/kg for 2 months). Over a 3-month period, the neurological status of the patient worsened with bilateral facial anaesthesia, left peripheral facial palsy, left hypoacousia and paresis of both ocular motor nerves.

The second brain MRI, performed 3 months after the onset of symptoms, revealed increased lesions on both the trigeminal nerves (figure 1B), masses on the left cochleovestibular and facial nerves, well depicted on T2-weighted images (figure 1C), and a small gadolinium-enhanced lesion in the left internal capsule on T1-weighted sequences (figure 1D). The second LP gave no further diagnostic information showing 38/mm3 normal lymphocytes, 75 mg/dL protein and normal glucose levels.

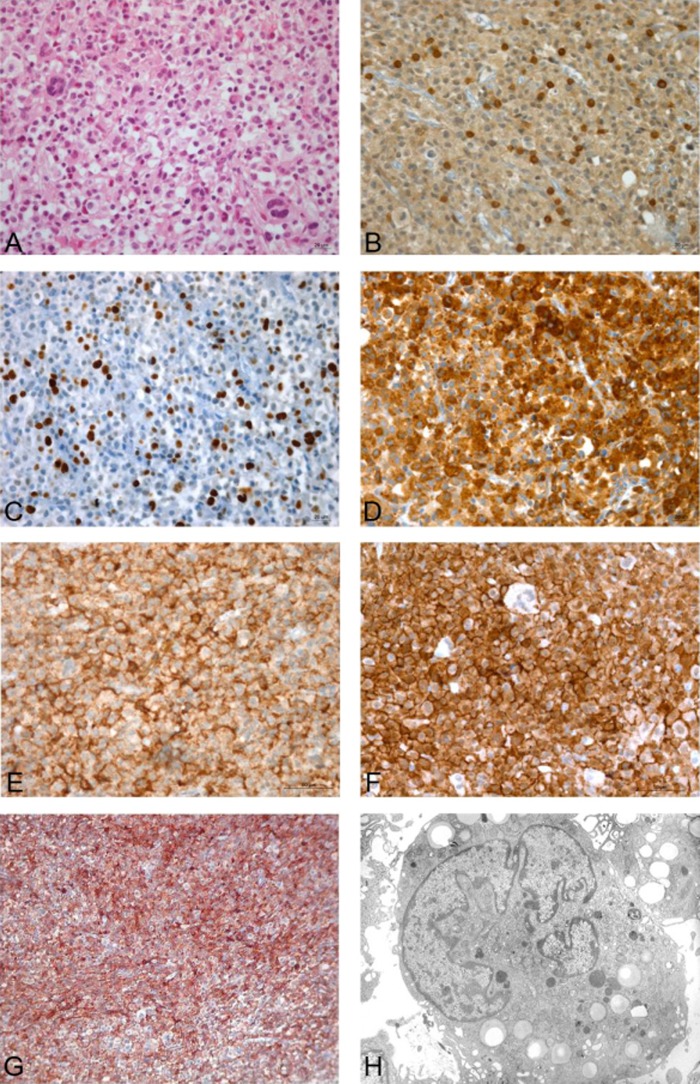

Exploratory surgery was decided on and the tumour of the left trigeminal nerve was partially dissected under microscopic guidance. The biopsy revealed the dissociation of the trigeminal nerve by a dense cellular lesion consisting of large cells distributed along the remnants of demyelinated or damaged nerve fibres (figure 2A–F). The tumour was composed of large polymorph, non-cohesive cells. The cytoplasm of the cells was pale or eosinophilic, and inconstantly vacuolated. The nuclei were lobulated, hyperchromatic and generally located eccentrically, with small nucleoli. Atypic mitoses were visible, as well as many scattered giant cells. There was a limited infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages but no plasmocytes or polynuclear cells were seen. There were no signs of necrosis. An extensive panel of immunohistochemical markers was tested. Tumour cells were strongly positive for CD68, lysozyme, CD163, iBa1, Mic99, vimentin, Ki1(24%) and HLA-DR (figure 2G), but negative for CD3, CD20, CD45, Bcl2, Alk, TiA1, CD1a, CD21, CD34, CD30, CD117, CK, EMA (epithelial membrane antigen), LMP1 and EBER (Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA). Electron microscopy showed that the tumour cells were merely apposed with no interdigitating processes or cell junctions. The cytoplasm was abundant, containing many lipid vacuoles, lysosomes, mitochondria and an extensive endoplasmic reticulum but no Birbeck granules (figure 2H). The nuclei were eccentric, deeply indented or multisegmented, with round or indented nucleoli.

Figure 2.

Original magnification ×40; immunostains visualised using 3,3′ diaminobenzidine as a chromogen. (A) Infiltrating tumour cells (H&E); (B) a few T cells (CD3); (C) high proliferation index of tumour cells (Ki1); strong immunoreactivity of tumour cells (D) for CD68; (E) for CD163; and (F) for iBa1; (G) HLA-DR activation; (H) electron micrograph: tumour cell showing an eccentric multisegmented nucleus and several cytoplasmic lipid droplets. Magnification ×2.750. Uranyl acetate-lead citrate stain.

Treatment

The patient was initiated on chemotherapy which included ifosfamide, vincristine, cytosine arabinoside and methotrexate. She received five chemotherapy cycles along with two cycles of intrathecal methotrexate and cytosine arabinoside.

Outcome and follow-up

After a slight transient neurological improvement, she developed aphasia, had swallowing difficulties and suffered complete paralysis of her right upper limb. The patient expired 20 days after the last chemotherapy cycle owing to septic shock. Consent for autopsy was denied.

Discussion

Isolated cranial nerve palsies affect a wide variety of cranial nerve combinations in diverse locations and are due to various causes.14 The sixth, seventh, third and fifth cranial nerves are the ones more commonly affected in order of frequency. Tumours, vascular diseases, traumatisms, infections and autoimmune processes are the more frequent causes.14 Symptomatic trigeminal nerve neuropathy, as in our patient, requires checking for haematological malignancies, particularly in the presence of the numb chin syndrome or nasopharyngeal carcinoma, the latter being common in regions of Southeast Asia and the Mediterranean Basin.15 Primary CNS HS is a very severe rare disease that should be suspected when facing rapidly evolving neurological manifestations. The clinical signs and symptoms, which are usually non-specific, depend on the localisation of the tumour and include weakness, dizziness, vomiting and loss of consciousness.6 Only a single report of CNS HS presenting as cranial nerve palsies has been published in the literature so far.4 This is the second case to date. However, the actual occurrence of CNS HS may be underestimated because pathological confirmation is not usually attempted. The results of MRI are not specific of HS, showing unifocal or multifocal lesions that might mimic inflammatory or lymphomatous processes. The diagnostic pitfalls associated with CNS HS include lymphomas, infections, idiopathic inflammatory disorders and paraneoplastic syndromes. Biopsies are mandatory for definitive diagnosis and should not be delayed. Microscope-guided neurosurgery, which allows the safe dissection of cranial nerves, should be performed if no other lesion is accessible for biopsy or resection. Rigorous immunohistochemical investigation with specific histiocytic markers is required to determine the presence of true histiocytic lymphoma.1 3 10 One peculiar pathological feature of primary CNS HS, not often seen in true HS at other sites, is an intense inflammatory infiltrate, sometimes forming an abscess that may be diagnostically challenging.8 16 The other histopathological differential diagnoses that should be considered include large-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, notably anaplastic large-cell lymphoma and diffuse large-cell lymphoma, especially as these diseases often manifest as cranial nerve palsies, with the V nerve being frequently involved. Granulocytic sarcoma, malignant melanoma, reactive histiocytic proliferations, dendritic cell neoplasm, undifferentiated carcinoma, inflammatory pseudotumour or the Rosai-Dorfman disease may also mimic HS.1 The first step must be the immunohistochemical staining of tumour cells with activated monocyte/macrophage markers, especially CD163. Subsequently, staining of other markers will rule out more frequent diseases of epithelial and lymphoid lineage. At present, CD163, a haemoglobin scavenger receptor exclusively expressed by cells of the monocytic/histiocytic lineage, confirms the histiocytic origin of a tumour and is more specific than other monocytic and histiocytic markers such as CD68.17 However, it is a good practice to add CD68 to CD163. CD163 has consistently shown intense immunoreactivity in HS.1 8 In our case, the negative staining of TiA1 ruled out a granulocytic sarcoma; the absence of CD3, CD20, CD21, CD30, Alk, LMP1, EBER and the TCRγ rearrangement excluded large B-cell and T-cell lymphomas, anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma and follicular dendritic cell sarcoma; and the absence of CD117 and CD34 ruled out a myeloid sarcoma. The negative staining for pancytokeratin and EMA ruled out carcinoma and meningioma; the negative S100 protein staining did not support a diagnosis of melanoma or the Rosai-Dorfman disease; and the positive CD68 and CD163 staining patterns confirmed the histiocytic origin of the HS.1 3

There are no standard treatment guidelines for CNS HS owing to the lack of clinical trials and the small number of cases reported. Primitive CNS HS is typically a very aggressive tumour, resulting in significant patient morbidity and leading to a grim prognosis with a median survival rate of less than 6 months. The disease has been observed to follow an indolent course in only five cases so far,8 10 12 13 with response to subtotal4 or total8 12 local resection and adjuvant radiation.4 12 This treatment was followed by a relapse to the mediastinum 42 months later for one patient,4 whereas the others remained disease-free for 10–42 months.12 13

Thus, despite the small number of patients with CNS HS described so far, and in the absence of positive results with chemotherapy, maximal feasible resection followed by high-dose radiotherapy may be recommended for the treatment of this aggressive tumour.

Learning points.

Primary central nervous system histiocytic sarcoma (CNS HS) is a haematopoietic neoplasm that should be suspected when facing rapidly evolving neurological manifestations, notably those affecting the cranial nerves.

The principal differential diagnoses are pseudoinflammatory tumours or abcess and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, as they often manifest as a cranial nerve involvement.

Diagnosis relies only on biopsy and strict criteria with extensive immunohistochemical workup including specific markers like CD163, with the exclusion of markers of other cell lineages.

Earlier recognition is important as to deal with it appropriately and more accumulation of clinical and pathological experience with true CNS HS will help to guide prognosis and treatment for future patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Kanaya Malkani for a critical reading and comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: JM carried out the pathological examinations and the comprehensive immunophenotypic testing.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Takahashi E, Nakamura S. Histiocytic sarcoma: an updated literature review based on the 2008 WHO classification. J Clin Exp Hematop 2013;53:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, et al. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood 2001;117:5019–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pileri SA, Grogan TM, Harris NL, et al. Tumours of histiocytes and accessory dendritic cells: an immunohistochemical approach to classification from the International Lymphoma Study Group based on 61 cases. Histopathology 2002;41:1–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao M, Eshoa C, Schultz C, et al. Primary central nervous system histiocytic sarcoma with relapse to mediastinum: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2007;131:301–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toshkezi G, Edalat F, O'Hara C, et al. Primary intramedullary histiocytic sarcoma. World Neurosurg 2010;74:523–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, Li T, Chen H, et al. A case of primary central nervous system histiocytic sarcoma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2012;114:1074–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill-Samra S, Ng T, Dexter M, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma of the brain. J Clin Neurosci 2012;19:1456–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell SL, Hanzely Z, Alakandy LM, et al. Primary meningeal histiocytic sarcoma: a report of two unusual cases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2012;38:111–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devic P, Androdias-Condemine G, Streichenberger N. Histiocytic sarcoma of the central nervous system: a challenging diagnosis. QJM 2012;105:77–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalasani S, Hennick MR, Hocking WG, et al. Unusual presentation of a rare cancer: histiocytic sarcoma in the brain 16 years after treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Med Res 2013;11:31–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laviv Y, Zagzag D, Fichman-Horn S, et al. Primary central nervous system histiocytic sarcoma. Brain Tumor Pathol 2013;30:192–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu W, Tanrivermis Sayit A, Vinters HV, et al. Primary central nervous system histiocytic sarcoma presenting as a postradiation sarcoma: case report and literature review. Human Pathol 2013;44:1177–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pérez-Ruiz E, Delgado M, Sanz A, et al. Primary leptomeningeal histiocytic sarcoma in a patient with a good outcome: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 2013;7:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keane JR. Multiple cranial nerve palsies. Analysis of 979 cases. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1714–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonella MC, Fishbein NJ, So YT. Disorders of the trigeminal system. Semin Neurol 2009;29:36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheuk W, Walford N, Lou J, et al. Primary histiocytic lymphoma of the central nervous system: a neoplasm frequently overshadowed by a prominent inflammatory component. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1372–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen TT, Schwartz EJ, West RB, et al. Expression of CD163 (hemoglobin scavenger receptor) in normal tissues, lymphomas, carcinomas, and sarcomas is largely restricted to the monocyte/macrophage lineage. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:617–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]