Abstract

Objectives

A passport-sized booklet, designed by patients for patients to record details about their medicines, has been developed as part of a wider project focusing on improving prescribing in the elderly (‘ImPE’). We undertook an evaluation of ‘My Medication Passport’ to gain an understanding of its value to patients and how it may be used in communications about medicines.

Setting

The Passport was launched in secondary care with the initial users being older people discharged home after an admission to one of the four North West London participating Trusts. The uptake subsequently spread to other (community) locations and other age groups.

Participants

We recruited more than 200 patients from a cohort who had been given a passport as part of the improvement projects at one of four sites. Of them, 63% (133) completed the structured telephone questionnaire including 27% for whom English was not their first language. Approximately half of the respondents were male and 40% were over 70 years of age.

Results

More than half of the respondents had found their medication passport useful or helpful in some way; 42% through sharing details from it with others (most frequently family, carer or doctor) or using it as a platform for conversations with healthcare professionals. One-third of those questioned carried the passport with them at all times.

Conclusions

My Medication Passport has been positively evaluated; we have a better understanding of how it is used by patients, what they are recording and how it can be an aid to dialogue about medicines with family, carers and healthcare professionals. Further development and spread is underway including an App for smartphones that will be subject to wider evaluation to include feedback from clinicians.

Keywords: GENERAL MEDICINE (see Internal Medicine), THERAPEUTICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Patients’ own opinions were sought following their 4–6-week period of use of a personally issued My Medication Passport (MMP).

Patients valued MMP as an aid to communicating about medicines in their own way and writing in it what they choose.

As a self-completed list of medications and notes, it complements any other documentation about medicines produced by healthcare professionals, be they from general practitioner (GP) (eg, repeat slips) or hospitals (eg, discharge summaries or dose reminder charts).

We were able to recruit only patients who were well enough to be contacted by telephone during a specific period of time. This selection process may be biased in favour of patients who are better able to manage their medicines with or without an MMP.

We did not look at what was written in the MMPs to check for accuracy of content or legibility. This may be the focus of a further study.

Background

My Medication Passport (MMP) is a pocket-sized booklet designed for patients’ personal use to record details of their medication and related information and to thereby keep track of their past and current medicines use. It is hoped that the use of MMP might improve communications about medications across organisational boundaries and support patients in managing conversations about their medicines when they are talking to healthcare professionals (HCPs) and to carers, friends and family. It was developed originally as part of a collaborative project in North West London1 to improve prescribing and medicines management in the elderly (ImPE) and has spread to other age groups and geographical areas.

The MMP includes some general ‘dos and don'ts’ of medicines use and the following sections for completion by the patient:

Allergies

Medication aids (non-click lock lids/large label fonts/blister packs/liquids/tablet cutter/other)

Current medicines (including inhalers, eye/ear drops, patches, injections and alternative/herbal medicines)—date, name, dose, times and additional information

Changes to my medicines (date, reason for change, by whom)

Blank pages for notes (illnesses, vaccinations, screenings) and to record additional needs

It is recognised that communication about medicines needs to improve between medical professionals from different disciplines, and between professionals and patients/carers. There is evidence that gaps in communication and incomplete documentation, particularly concerning the elderly and medicines at discharge from hospital, contribute to readmissions.2 Closing this gap is likely to result in health benefits, including a reduction in adverse drug events.3

It is estimated that among patients with long-term conditions, as many as 30–50% do not take their medicines as intended4 and intervention to improve adherence may have a greater impact on the health of the population than improvements in specific medical treatments.5 Part of the solution is to encourage self-management of health problems with HCP providing, for example, compliance aids and portable records in support.6 7

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the use of MMP by a cohort of patients with the intention of gaining a better understanding of its value. In particular, we wanted to find out whether MMP helped to foster good communications between patients and HCPs; improved patients’ confidence about what medicines they take; and we also wanted to increase our understanding of whether changes to medicines are likely to be recorded in MMP and kept up to date.

Methods

Research setting and sample

The study involved four sites:

Hillingdon Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust;

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust;

Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust;

Marylebone Health Care Centre.

To elicit a map of MMP use, a short structured telephone survey was carried out. The purpose was to find out whether patients had used their passport and whether they had shared it with an HCP, family member or friend. In the context of the questionnaire, by ‘shared’ we explained that we mean: showed it to; talked about it with; used it to aid a conversation with (a friend, carer, family member, HCP).

To elicit a better understanding of how useful the passport had been and to gain insights into the strengths, weaknesses and any perceived obstacles to the use of MMP, each study site was asked to conduct 10 longer surveys. Information about the purpose of MMP and the aims of the evaluation was given to patients (see online supplementary appendix 1), along with consent forms that were completed prior to surveys being conducted.

Data collection procedures

Patients who were contacted to complete the short telephone survey were systematically sampled from a database of those who had given their consent until at least 30 short and 10 longer telephone surveys had been completed from each of the four settings. Patients were contacted up to three times each to elicit a survey. The intention was to reach the target number of patients and conduct surveys within a defined timescale of 4–6 weeks from first issue.

Data elements collected

The survey questionnaire forms were designed, generated, scanned and verified using TELE form. TELE form is a software package comprising four separate programs that combine to create forms that can be printed out with automatic individual serial identity numbering, scanned after data entry, all data identified and validated, then exported to one or more selected databases ready for reporting and/or statistical analysis. When a form is designed using TELEform, the questions are designated as ‘choice fields’, ‘constrained print fields’ or ‘image zones’. In the image zones, the software is able to identify manually written text. After the completed survey questionnaires were scanned, the verification of the data using the TELEform software provided double data entry. The data were exported simultaneously to populate databases generated in SPSSv20 and Excel.

Data quality and analysis

The content of the survey questionnaires was based on consultations previously carried out with a sample of stakeholders (including patients, carers and hospital staff).

The survey questionnaires were designed to answer the overarching evaluation questions about patients’ use of their personal MMP in communications and adherence. Each study site collected the same data and used the same methods, and data collected by staff in each study setting were forwarded to the Evaluation Lead and specialist survey designer for analysis.

Results

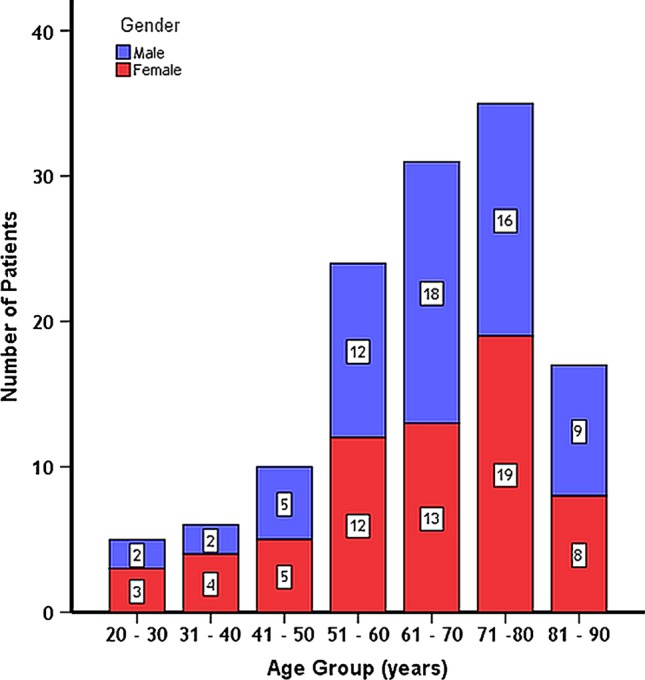

In total, 202 patients were recruited to the study and 133 completed one or both surveys (66% response rate). Ninety participants (majority male) completed only the short survey and 43 also completed the longer survey (13 men, 29 women and 1 participant for whom gender was not recorded). The majority of patients were in the 71–80-year-old age group. Demographic data are summarised in figure 1. The majority of patients answered ‘No’ to questions identifying any additional needs in relation to communication. However, 10% of patients were partially sighted or blind, 19.5% had some degree of difficulty in hearing and English was not their first language for 27% of respondents (see table 1).

Figure 1.

Age and gender of participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients participating in the survey (n=133)

| Yes |

No |

Not stated |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | |

| Hard of hearing or deaf | 26 | 19 | 94 | 71 | 13 | 10 |

| Partially sighted/blind | 13 | 10 | 104 | 78 | 16 | 12 |

| Require an interpreter | 2 | 1 | 113 | 85 | 18 | 13 |

| Any learning difficulty | 5 | 4 | 115 | 86 | 13 | 10 |

| Require an advocate | 5 | 4 | 114 | 86 | 14 | 10 |

| English is first language | 82 | 62 | 36 | 27 | 15 | 11 |

From the 36 patients for whom English was not their first language, three telephone surveys were carried out with an interpreter (in Cantonese, Punjabi and Bengali). In addition, the languages summarised in table 2 were mentioned as the ‘first’ language of patients who also spoke English fluently.

Table 2.

First language of fluent English speakers

| Language | N |

|---|---|

| Punjabi | 4 |

| Gujarati | 4 |

| Hindi/Urdu | 2 |

| Turkish | 1 |

| Arabic | 1 |

| French | 2 |

| Filipino | 2 |

| Swahili | 2 |

| Farsi | 1 |

| Gaelic | 1 |

| German | 1 |

| Italian | 1 |

| Spanish | 1 |

Of those respondents who indicated that they were hard of hearing, visually impaired, had a learning difficulty or required an advocate or interpreter, only 12% recorded this information about themselves in their MMP.

How MMPs are used

Fifty-two per cent of patients had used their passport in some way since receiving it and 58 of the 133 questioned (42%) had ‘shared’ it with someone; most frequently, this was a family member, as shown in table 3. Thirty-two patients had ‘shared’ their MMP with one or more HCPs; those most frequently cited were the general practitioner (GP) and hospital doctor.

Table 3.

‘Sharing’ of My Medication Passport (n=133)

| Number |

||

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| General practitioner | 24 | 47 |

| Hospital doctor | 24 | 46 |

| Other hospital staff | 13 | 53 |

| Pharmacist (community) | 8 | 60 |

| Community nurse | 7 | 59 |

| Pharmacist (hospital) | 3 | 63 |

| Voluntary sector organisation | 3 | 64 |

| Dentist | 2 | 65 |

| Optician | 2 | 64 |

| Care home | 0 | 65 |

| Mental Health Services | 0 | 66 |

| Family member | 57 | 18 |

| Friend | 17 | 48 |

| Other | 6 | 49 |

Some respondents commented that they thought the passport was for their use only and did not feel the need to take it with them to HCP visits/appointments. However, of the 32 patients who did, 22 (69%) reported that it improved their confidence in talking to the HCP about their medicines. A further two patients were ‘not sure’.

Thirty-three per cent carried their MMP at all times and 37% responded with ‘sometimes’. When asked ‘Will you take your passport with you when you see your HCP in the future?’, 81.4% said yes, they would.

Patients responding to the longer survey were asked about medication changes (within 6 weeks of owning an MMP). Sixty-seven per cent of respondents reported that they recorded details in their MMP. Their recorded reasons for the change, most commonly side effects, are given in table 4. None reported that an HCP wrote in their passport; they completed this themselves or a carer or family member helped.

Table 4.

Patients’ comments on why their medicines were changed (n=43)

| Reason given | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Side effects | 4 |

| Legs swollen | 3 |

| Help heart rate | 1 |

| Prior to operation | 1 |

| New style inhaler | 1 |

| Prostate enlarged | 1 |

| Sodium levels too high | 1 |

| Heart palpitations | 1 |

| Medication not working, started chemotherapy | 1 |

| Shared decision, but not happy with change | 1 |

| Not sure | 1 |

| Total comments | 16 |

Overall, the majority of patients indicated that they were pleased to have a passport in which they themselves or their carer documented changes (76%). However, 14% said they would like an HCP to do this.

Eighty-six per cent of respondents (37 of the 43 people who completed the long survey) reported ‘yes’, they would recommend MMP to ‘friends or family’, but one was ‘not sure’.

Further positive comments given by patients (or carers where indicated) were:

My GP thought that the passport is a really good idea and said that I should carry it with me and keep it up to date.

They said it was a good idea. First one they've seen. Yes. It helped communication with them.

Very easy. Was more accurate than GP record. Eased communication. Facilitated dialogue.

It was very useful. I see so many different doctors now. One document [for medicnes] and all of them can see the same information.

(Carer) Helpful – as it makes it easier for [patient] as she doesn't speak English. MMP makes it easier for family member too because they can just hand it over to the professional to see.

It was fine [sharing MMP]. She [HCP] didn't really look at it as she said she had a list. Dermatologist didn't really look. However, my carer found it useful and it helps the communication between them and me with HCPs.

Very helpful to be on top of new medicines, and view MMP prior to sharing with GP.

[Spouse] became ill recently. MMP useful to remind myself [carer]. Helpful to talk to GP.

Really useful to her [patient] and me as carer. Helps to have conversations about medicines and keep track of things. Will order another MMP for my mother in law. My sister and wife use this too (they are additional carers).

Negative comments included:

One respondent had concerns over ‘identity theft’ and one about ‘accuracy’. Another suggested that the MMP duplicates what the GP already does and a further two thought it was better to use the ‘pharmacy’ list. Other comments included:

No easy way of writing in the changes to give a clear view of the latest date/entry. I have 10 medicines. Maybe one changes for a week. Then changes back. It could get messy quite quickly.

My medicines change so often. I'd be updating the passport too often. I prefer to use the slips/information from the pharmacy. They have a good system. It works well. I can see that MMP will work well for someone who does not have a good system already.

Suggestions for improvements

Several suggestions for improvement to the MMP were elicited from respondents who had used or attempted to use their MMP. These are listed in table 5.

Table 5.

Suggestions for improvement of My Medication Passport

| Patient's comments | Number of respondents |

|---|---|

| None needed | 23 |

| Add list of medication side effects | 20 |

| Record allergies, infections, hospital visits, results, immunisations, travel vaccinations, past history, blood type, screening, contact in emergency | 8 |

| Bit smaller for men to put in pocket | 5 |

| More pages at back, either blank or labelled: A current med, B med changes | 4 |

| Need better cover, more like diary | 3 |

| Need bigger print, difficult to read | 2 |

| Would like own language version | 1 |

| Separate listings of short-term and long-term medications | 1 |

| Prefer type of credit card to be scanned by doctor or ambulance driver | 1 |

| No response/do not know | 24 |

Twenty respondents suggested the need for space to record medicines' side effects. (Note: This was provided as an example by the interviewer.)

Sometimes the Chemists have given me something that disagrees with me. I will use the passport to record that and tell the pharmacy.

Eight respondents suggested the addition of space to record a variety of specific things: health conditions, hospital visits/appointments, medical test results, screening, vaccinations, history of operations, etc.

Five patients suggested a smaller format (especially that men would like something to put in their pocket). Further comments included:

Far too big for pocket. Needs to be much smaller. Would like an e-system but does not have an android phone. Liked the idea of an App.

The book is written in English. If it was translated in Bengali then the patient could themselves understand and write something themselves. The book would be better if it was a smaller size.

Discussion

‘Passports’, as tools enabling patients to better manage their medicines, have been used in targeted patient groups with reported evidence of success, for example, in palliative care,8 diabetes,9 inflammatory bowel disease6 and glucocorticoid replacement therapy.7 Medication passports may be regarded as a support to self-management and a decision aid if used in communications with the doctor when considering a new therapy.10

Most respondents to our questionnaire reported positive results; they felt their MMP was useful, that it facilitated dialogue about medicines and that a patient held, patient-filled portable document was ‘a good idea’.

Less than 20% of patients had discussed their passport with their GP; we had anticipated that more patients would have done so within the 4–6-week time period between being given MMP and participating in the survey. The majority reported an intention to do so at future consultations. However, there appeared to be a strong feeling among respondents that this was not their perceived use for the passport; it was for their personal recording, and though it might be used to facilitate discussions about medicines with doctors, it was more important as an aide-memoire for the user.

For those respondents who had shared their passport with someone else, family members ranked highest. Several mentioned how useful it was to both patients and carers. The majority affirmed that MMP is useful in aiding communication between themselves and HCPs. Carers too liked MMP and found that it provided them with a point of reference when the need arose to talk to either the patient or the patient's HCP.

The majority of respondents saw MMP as helpful in managing their medicines despite some reservations from patients whose medicines were subject to frequent change. The recording of side effects seems to be important to users. This finding is perhaps expected as patients phoning our medicines information helpline ask most frequently about side effects of medicines than any other category of query,11 and patients’ experience surveys consistently suggest that not enough is given in plain language.12

Limitations

The use of MMP is not obligatory, or ‘prescribed’. Its users are usually introduced to it by a clinician, and they are chosen because they take multiple medicines. It is free of charge, but the choice of whether to use it or not is the recipient's. For these reasons, recruitment of patient participants in this evaluation should be understood to have been ‘self-selected’.

We were able to recruit only patients who were well enough to be contacted by telephone during a specific period of time and only 66% participated. It is recognised that those less able to be recruited to this study might be the more vulnerable patients with a greater need for assistance with managing their medicines. They remain the ones who are more difficult to assess and more in need of tools such as passports and compliance aids in general.

MMP is being used by different cohorts of patients across the sites included in the study. Many people who take multiple medicines are elderly and/or have comorbidities. It was recognised and acknowledged from the outset that the present study is ‘formative’ and that it may be necessary to carry out a further, larger and/or more in-depth study to gain a deeper understanding of potential changes that may be needed to evaluate MMP use by different types of patients.

Recommendations and conclusion

Although based on small numbers, it would appear that the availability of MMP in different languages or with bilingual text/headings would be an asset.

Space for recording of side effects in particular would be useful, as well as more specific space for changes to medication (or perhaps continuation sheets). This should be followed by a further evaluation of MMP in particular user groups: frail patients, those with certain long-term conditions, homeless patients or patients who move frequently (eg, students and some new immigrants).

Further analysis of the number of men and women who had used their MMP or shared it with an HCP is suggested to help us to understand the gender differences in response rate found in the evaluation.

This evaluation was not structured to find out what patients write in their MMP; it may be valuable to do this in a further study. Rather, we set out to gain an understanding of how what was written by the patient was used and this has, with limitations, been achieved.

NIHR CLAHRC for NW London has since rolled out the MMP across London and the wider community through other hospitals, community pharmacies and GP surgeries and successfully launched an ‘App’ version, now available to download onto smartphones and devices. We have communicated through several media with over 45 000 copies distributed and over 2400 ‘app’ downloads to date.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Sara Garfield, Shirley Kuo, Sabrina Amer, Saadi Jamil, Seetal Jheeta, Sylvia Chalkley, Stella Barnes, Iñaki Bovill, Louise Collins, Edward Dickinson, Beverly Hall, Fran Husson, Ann Jacklin, Nick Jones, Colin Mitchell, Sue Newton, Sam Oliver, Karen Phekoo, Ganesh Sathyamoorthy, John Soong, Margaret Turley and Tom Woodcock. Sara Garfield and Shirley Kuo conducted interviews, contributed to the development of the protocol and assisted in the writing of the evaluation report. Sabrina Amer, Saadi Jamil and Seetal Jheeta conducted patient interviews. Sylvia Chalkley of Chalkley Survey Design & Statistical Analysis Ltd. structured the Survey questionnaire. Other members of the ImPE Supergroup were key to the development, promotion and spread of the My Medication Passport and co-ordinating the evaluation: Stella Barnes, Iñaki Bovill, Louise Collins, Edward Dickinson, Beverly Hall, Fran Husson, Ann Jacklin, Nick Jones, Colin Mitchell, Sue Newton, Sam Oliver, Karen Phekoo, Ganesh Sathyamoorthy, John Soong, Margaret Turley and Tom Woodcock.

Footnotes

Contributors: SB led the evaluation, developed the protocol and supervised the data collation from all sources, the analysis and writing of the original report. KT led the original project that resulted in the patient development of the My Medication Passport and the App, its promotion and spread, and assisted with data evaluation and writing of the manuscript. VM participated in the collation and evaluation of the data, promotion of the My Medication Passport and prepared and edited the manuscript for submission. BDF contributed to the development of the protocol, supervised the data collection at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and assisted with the analysis and writing of the original evaluation report. DB as Director for NIHR CLAHRC for NW London directs the programme of work including development of the My Medication Passport, promotion and spread through partner organisations. He contributed to the evaluation and editing of the manuscript for publication.

Funding: The sponsor of the study was the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (NIHR CLAHRC) for North West London, which is hosted by Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, in partnership with Imperial College London. The Centre for Medication Safety and Service Quality is partly funded by the NIHR Imperial Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The following extra data are available: the data split between the short and longer surveys completed by patients; patients’ comments on why and when their medicines were changed and by whom (n=16). Modified questionnaires (not included in this evaluation) completed by five healthcare professionals about the My Medication Passport; the patient target sampling matrix; promotional material (posters and leaflets) for My Medication passport. Available from the corresponding author: Vanessa Marvin, Deputy Chief Pharmacist, Chelsea & Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, 369 Fulham Road, London SW10 9NH, email: vanessa.marvin@chelwest.nhs.uk.

References

- 1.Jamil S. My medication passport: a report of the initial evaluation and results from the North West London consultation. CLAHRC (Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care). London: Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, 9 November 2012. http://patientsafety.health.org.uk/resources/improving-prescribing-elderly-impe-project and. http://www.hsj.co.uk/resource-centre/best-practice/patient-involvement-resources/passport-to-improved-patient-experience/5047524.article#.UufCTNJFBpg [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witherington EMA, Pirzada OM, Avery AJ. Communication gaps and readmissions to hospital for patients aged 75years and older: observational study. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:71–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picton C, Wright H. Keeping patients safe when they transfer between care providers—Getting the medicines right. A Guide for all providers and commissioners of NHS Services. Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Medicines Adherence. January 2009. http://www.nice.org.uk, Clinical Guideline No. 76 [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. January 2003. http://www.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js4883e

- 6.Saibil F, Lai E, Hayward A, et al. Self management for people with inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol 2008;22:281–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Repping-Wuts HJ, Stikkelbroeck NM, Noordzij A, et al. A glucocorticoid education group meeting: an effective strategy for improving self management to prevent adrenal crisis. Eur J Endocrinol 2013;169:17–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Latimer EJ, Crabb MR, Roberts JG, et al. The patient care travelling record in palliative care: effectiveness and efficiency. J Pain Symptom Manage 1998;16:41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dijkstra RF, Braspenning JC, Huijsmans Z, et al. Introduction of diabetes passports involving both patients and professionals to improve hospital outpatient diabetes care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2005;68:126–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. An introduction to patient decision aids. BMJ 2013;346:f4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marvin V, Park C, Vaughan L, et al. Phone-calls to a hospital medicines information helpline: analysis of queries from members of the public and assessment of potential for harm from their medicines. Int J Pharm Pract 2011;19:115–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marvin V, Kuo S, Vaughan L, et al. How can we improve patients’ knowledge and understanding about side-effects of medicines? Storyboard presented at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement National Forum on Quality Improvement in Healthcare; Orlando, Florida, 9–12 December 2012 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.